India’s proposed US$5.4-billion “free medicine for all” policy promises to be a game-changer for the lives of millions of poor and vulnerable people, many of whom cannot afford their medications or are not being reached by public health facilities.

Modelled on programs that currently exist (to varying degrees of sophistication) in the states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Bihar and Rajasthan, the nationwide program is expected to be rolled out in October and to substantially bolster access to medications.

And as with a recent decision by the government of India to issue its first patent compulsory licensing order (www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.109-4246), it is expected to have major ramifications for the pharmaceutical market.

The free medicines will be generics. Doctors working in health facilities will be required to prescribe generic drugs listed on state-determined “essential drug lists” and face penalties if they fail or decline to do so, though the nature of those penalties have not yet been specified.

It is also expected to have a substantial impact on clinical practice and treatment protocols. As part of the initiative, the government has sent a national list of essential medicines, containing 348 medications, to each of India’s 28 states (http://pharmaceuticals.gov.in/NLEM.pdf), and asked them to appoint scientific committees to craft state lists (bearing in mind such factors as the local incidence of specific diseases), as well as standardized protocols for treatment. All generic drugs to be utilized within the plan will be purchased by a central, autonomous, national procurement agency, so as to achieve savings through bulk purchasing.

The government’s planning commission projected in its Report of the Working Group on Drugs & Food Regulation for the 12th Five Year Plan that the initiative would expand public health care coverage to 52% of each state’s population (on average) from a current level of about 22%, once the program is fully implemented within the nation’s 23 000 primary health centres, 5000 community health centres and 640 district hospitals (http://planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/committee/wrkgrp12/health/WG_4drugs.pdf).

The cost? A brisk US$5.1 billion for “running costs,” and an additional US$232 million for capital costs. The national government will be expected to absorb 85% of the costs and the state governments 15%.

The government’s planning commission projects that its free medicine initiative will expand public health care coverage to 52% of each state’s population (on average) from a current level of about 22%.

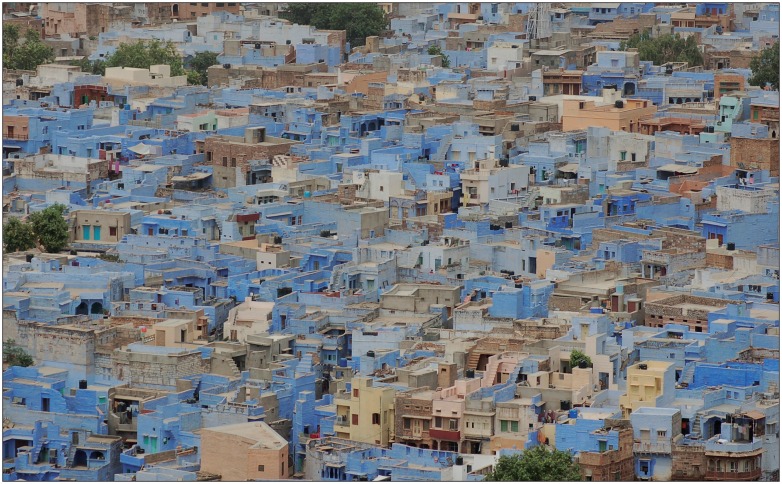

Image courtesy of © 2012 Thinkstock

But some experts fear the financial projections may be overly optimistic and point to the experience of Tamil Nadu, where the state government spent roughly US$37 million on its program in 2011 and found its health facilities overwhelmed by demand, swamped by wait times and often facing drug shortages once it lifted income eligibility caps and opened its facilities to all comers last year.

“We need to look at the sustainability of this program,” says Dr. Gitanjali Batmanabane, a professor of pharmacology at the Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research in Pondicherry, located on the shores of the Bay of Bengal. “Once medicines are given free, even those who can very well afford [them] will come to take them. As the numbers grow, maintaining supplies and distribution becomes difficult. Unless there is a very well-selected list of essential medicines, this will not be possible. The drug supply chain management in the states simply will not be able to cope with this.”

Still, Batmanabane and others expect that there will be huge health benefits for the disadvantaged, many of whom simply cannot afford the high cost of drugs, which the government’s planning commission projected to be between 50%–80% of the overall treatment costs of any patient.

“The free-medicines-for-all scheme is very welcome, especially in the states where access to essential medicines is dismal,” says Batmanabane. “Hence people will start coming to the health facilities and using them — this is seen in Rajasthan, where I saw for myself what a world of difference a committed government is doing.”

“If free medicines are available, it would be hugely beneficial to the common man, who cannot afford expensive medicines, mostly,” argues Pradip Kar, a social worker in Mathabhanga, a rural area of the state of West Bengal.

But others say there is no guarantee that the program will reach the targeted population.

“Procurement and heavy spending [on] essential drugs do not necessarily guarantee benefits translated to the masses,” says Dr. Raman Kumar, president of the Academy of Family Physicians of India. “Our public health policies should not be driven by pressure to spend [often there are annual budgetary targets for purchase of drugs]. In a system which lacks administrative and clinical accountability, such programs are less likely to reach [the] right beneficiary.”

Kumar adds the program’s success will rest on accountability mechanisms. “Essential preconditions for the success of the program are ensuring administrative efficiency and distribution based on local clinical requirements [evidence- and clinical guidelines-based] of the targeted population. Efficient gate-keeping on clinical spending through deployment [of a] skilled work-force and [an] effective barrier to [a] corrupt procurement process, regular financial and clinical audits [and] integration with the comprehensive clinical services are also needed.”