Abstract

Metabolic actions of insulin to promote glucose disposal are augmented by nitric oxide (NO)-dependent increases in microvascular blood flow to skeletal muscle. The balance between NO-dependent vasodilator actions and endothelin-1-dependent vasoconstrictor actions of insulin is regulated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent (PI3K) - and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent signaling in vascular endothelium, respectively. Angiotensin II acting on AT2 receptor increases capillary blood flow to increase insulin-mediated glucose disposal. In contrast, AT1 receptor activation leads to reduced NO bioavailability, impaired insulin signaling, vasoconstriction, and insulin resistance. Insulin-resistant states are characterized by dysregulated local renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Under insulin-resistant conditions, pathway-specific impairment in PI3K-dependent signaling may cause imbalance between production of NO and secretion of endothelin-1, leading to decreased blood flow, which worsens insulin resistance. Similarly, excess AT1 receptor activity in the microvasculature may selectively impair vasodilation while simultaneously potentiating the vasoconstrictor actions of insulin. Therapeutic interventions that target pathway-selective impairment in insulin signaling and the imbalance in AT1 and AT2 receptor signaling in microvascular endothelium may simultaneously ameliorate endothelial dysfunction and insulin resistance. In the present review, we discuss molecular mechanisms in the endothelium underlying microvascular and metabolic actions of insulin and Angiotensin II, the mechanistic basis for microvascular endothelial dysfunction and insulin resistance in RAAS dysregulated clinical states, and the rationale for therapeutic strategies that restore the balance in vasodilator and constrictor actions of insulin and Angiotensin II in the microvasculature.

Keywords: Nitric Oxide, Insulin Resistance, Endothelial Dysfunction, Angiotensin II

1. Introduction

Insulin resistance is frequently present in obesity, hypertension, coronary artery disease, dyslipidemias, and metabolic syndrome (DeFronzo and Ferrannini, 1991, Petersen, Dufour, Savage et al., 2007). Insulin regulates glucose homeostasis by promoting glucose disposal in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (Petersen et al., 2007). In addition to its direct actions on the skeletal muscle, insulin regulates nutrient delivery to target tissues by actions on microvasculature (Baron and Clark, 1997, Clark, 2008, Clark, Colquhoun, Rattigan et al., 1995, Clark, Wallis, Barrett et al., 2003, Barrett, Wang, Upchurch et al., 2011). These vasodilator actions of insulin are nitric oxide (NO)-dependent and lead to increased skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion that further enhances glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (Muniyappa, Montagnani, Koh et al., 2007, Vicent, Ilany, Kondo et al., 2003, Vincent, Clerk, Lindner et al., 2004, Zhang, Vincent, Richards et al., 2004). These actions of insulin on skeletal muscle microvasculature appear to be a rate limiting step for insulin-mediated glucose disposal. At the cellular level, balance between phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- (PI3K)-dependent insulin-signaling pathways that regulate endothelial NO production and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent insulin-signaling pathways regulating the secretion of the vasoconstrictor endothelin-1 (ET-1) determines the microvascular response to insulin. Insulin resistance is typically defined as decreased sensitivity or responsiveness to metabolic actions of insulin such as insulin-mediated glucose disposal. However, diminished sensitivity to the vascular actions of insulin also plays an important role in the pathophysiology of insulin-resistant states (Natali, Taddei, Quinones Galvan et al., 1997, Baron, Laakso, Brechtel et al., 1991). Endothelial insulin resistance is typically accompanied by reduced PI3K-NO pathway and an intact or heightened MAPK-ET1 pathway (Muniyappa et al., 2007).

The Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) plays a major role in microvascular function and remodeling. Ang II regulates endothelial NO production, arterial tone, skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion, and glucose metabolism in a receptor (AR)-specific manner (AT1R vs. AT2R) (Chai, Wang, Dong et al., 2011, Chai, Wang, Liu et al., 2010). In contrast to AT1R, stimulation of AT2R increases NO production, reduces vascular tone, and augments skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion (Chai et al., 2011, Chai et al., 2010). Activation of RAAS in insulin-sensitive tissues is known to induce insulin resistance (Cooper, Whaley-Connell, Habibi et al., 2007, Lastra-Lastra, Sowers, Restrepo-Erazo et al., 2009). In particular, chronic activation of RAAS impairs insulin signaling, increases oxidative stress, and reduces NO bioavailability (Cooper et al., 2007). However, insulin resistance also increases local RAAS activity triggering a vicious cycle that leads to endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and dysmetabolic states associated with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Thus, the relative contributions of AT1R and AT2R activation and cross-talk between the signaling pathways of insulin and Ang II appear to modulate endothelial function. Herein, we discuss the cellular mechanisms and signaling pathways underlying the microvascular actions of insulin and Ang II, the metabolic consequences of an imbalance in these pathways, and potential therapeutic interventions that may improve microvascular function in insulin-resistant conditions.

2. Role of Skeletal Muscle Microvasculature in Metabolism

Arterioles, capillaries and venules that are less than 150 μm in diameter are generally termed “microvascular” (Segal, 2005). Microvascular perfusion, especially in insulin sensitive tissues such as skeletal muscle and adipose tissue plays an important role in providing adequate delivery of nutrients, capillary surface area for nutrient exchange, and increased vascular permeability for nutrient transfer from plasma to tissue interstitium (Baron and Clark, 1997, Clark, 2008, Clark et al., 1995, Clark et al., 2003). The rate of substrate extraction and hence it’s arterio-venous difference (A−V) is governed by the classic equation: [(V)−(A)]=[(I)−(A)]×[1−e−PS/Q], where “V” is the venous, “A” the arterial, and “I” is the interstitial substrate concentration, “P” is surface permeability, “S” is exchange surface area, and “Q” is the plasma flow rate (Renkin and Rosell, 1962). Thus it is evident that a change in surface area and/or permeability significantly influences tissue nutrient extraction (Baron, Tarshoby, Hook et al., 2000). Skeletal muscle capillaries are arranged in groups termed ‘microvascular units’; recruitment and perfusion of these units are determined by the tone of capillary sphincter of terminal arteriole. Relaxation of the capillary sphincter dilates terminal arteriole and recruits capillaries to further increase nutrient exchange surface area and substrate extraction by the skeletal muscle (Segal, 2005). Dilation and constriction of terminal arterioles is modulated by endothelium-derived vasoactive substances that include vasodilators (e.g., nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandins (PGI2), endothelium-derived hyperpolarization factor (EDHF), epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs)) and vasoconstrictors (e.g., endothelin-1 (ET-1), prostanoids, isoprostanes). Thus, the balance in actions of vasodilators and vasoconstrictors determine microvascular blood volume and perfusion.

3. Endothelium Derived Vasodilatory and Vasoconstrictor Factors

3.1 Nitric Oxide

In the vasculature, NO, a short-lived signal molecule is released in a transient fashion on demand by enzymatic activation of a constitutively present NO synthase (NOS) in the endothelium (eNOS) (Michel and Feron, 1997). Significant amounts of NO can also be produced in a sustained fashion in endothelium and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in response to various agents and cytokines, through the expression of the inducible NOS (iNOS) (Michel and Feron, 1997). NO released from either source decreases vascular tone, inhibits VSMC proliferation, induces apoptosis, attenuates platelet aggregation, and reduces cell adhesion to vascular walls. Vasodilatory actions of NO are primarily mediated via reductions in VSMC intracellular calcium (Ca2+) concentrations secondary to NO-mediated guanylate cyclase activation and cGMP formation (Michel and Feron, 1997, Michel and Vanhoutte, 2010). eNOS is a homodimer that converts L-arginine and O2 to L-citrulline and NO. eNOS resides in the caveolae and bound to the caveolar protein, caveolin-1 that inhibits its activity (Dessy, Feron and Balligand, 2010, Duran, Breslin and Sanchez, 2010). Elevations in cytoplasmic Ca2+ promote binding of calmodulin to eNOS that subsequently displaces caveolin and activates eNOS (Dessy et al., 2010, Duran et al., 2010). In addition to undergoing regulatory posttranslational modifications, phosphorylation of various amino acid residues regulates eNOS activity (Michel and Vanhoutte, 2010). Phosphorylation of Ser1177 reduces Ca2+ sensitivity of eNOS such that NO production is triggered at ambient intracellular Ca2+ levels. However, phosphorylation at Thr495 prevents calmodulin binding to eNOS to reduce NO production (Michel and Vanhoutte, 2010, Fleming, 2010). Similarly, tyrosine phosphorylation at Tyr657 results in decreased eNOS activity (Michel and Vanhoutte, 2010, Fleming, 2010). In addition to changes in phosphorylation status of the enzyme, alterations in intracellular levels of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), an essential co-factor or the substrate L-arginine can also modulate enzyme activity (Crabtree and Channon, 2011, Gielis, Lin, Wingler et al., 2011).

3.2 Prostanoids/Eicosanoids

Prostanoids are the cyclooxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid and include prostaglandins (PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2), and thromboxane (TxA2) (Bos, Richel, Ritsema et al., 2004). Agonist stimulation of endothelial cells results in increases in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration that subsequently activates phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Tang, Leung, Huang et al., 2007). PLA2 acts on cell membrane phospholipids to release arachidonic acid that is metabolized by cyclooxygenases (COX): COX-1 is expressed constitutively in human endothelial cells and endothelial COX-2 is induced following exposure to inflammatory stimuli and agents (Garavito and DeWitt, 1999, Vane, Bakhle and Botting, 1998). However, COX-1 is the principal COX that produces endoperoxides (PGH2) in healthy and abnormal endothelium. Specific synthases convert PGH2 to prostanoids, PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2, or TxA2 (Davidge, 2001). Endothelial prostanoids diffuse into VSMCs to interact with specific G-protein-coupled membrane receptors. PGI2 and TxA2 bind to VSMC prostacyclin receptor (IP) and thromboxane prostanoid receptor (TP), respectively. IP receptor activation in VSMC leads to intracellular increases in cAMP that leads to vasorelaxation (Bos et al., 2004). In contrast, TP receptor activation in VSMC leads to increases in intracellular Ca2+ and vasoconstriction (Bos et al., 2004). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are also known to activate COX (Harlan and Callahan, 1984). Arachidonic acid is also metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) epoxygenase to produce epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) (Pfister, Gauthier and Campbell, 2010). Acting as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors (EDHFs), EETs act locally to decrease vascular tone. In VSMC, EETs activates large conductance, calcium-sensitive potassium (BKCa) channels, leading to vasorelaxation (Pfister et al., 2010). Furthermore, EETs activate cation channels of the transient receptor potential gene family (TRPV4) to augment Ca2+ signaling in the endothelium that leads to NO formation (Baylie and Brayden, 2011). Thus, the relative amounts and activities of PGI2, TxA2, and EETs play an important role in the regulation of microvascular tone (Feletou, Huang and Vanhoutte, 2010).

3.3 Endothelin-1

ET-1 by its actions on VSMC tone, oxidative stress, proliferation, and apoptosis plays an important role in vascular function (Marasciulo, Montagnani and Potenza, 2006, Khimji and Rockey, 2010). ET-1 secretion in the endothelium is regulated by two distinct pathways: a constitutive pathway, determined by gene transcription and a regulated pathway involving stimulated release from preformed ET-1 precursors in intracellular storage granules (Marasciulo et al., 2006, Khimji and Rockey, 2010, Goel, Su, Flavahan et al., 2010). ET-1 is synthesized predominantly in vascular endothelial cells, where the endothelin gene product, preproET-1 (ppET-1) is sequentially converted to big-ET-1 (bET-1) and active ET-1 by proteases (Marasciulo et al., 2006, Khimji and Rockey, 2010). Ang II and insulin increase (Hsu, Chen, Chang et al., 2004, Hu, Levin, Pedram et al., 1993, Kobayashi, Nogami, Taguchi et al., 2008, Oliver, de la Rubia, Feener et al., 1991), while NO and PGI2 inhibit ppET-1 expression in the endothelium (Bourque, Davidge and Adams, 2011, Prins, Hu, Nazario et al., 1994). Locally released ET-1, acting in a paracrine fashion binds to ETA receptors on VSMC causing sustained vasoconstriction (Verhaar, Strachan, Newby et al., 1998).

4. Effects of Insulin on Endothelium Derived Vasodilatory and Vasoconstrictor Factors

4.1 Insulin-Stimulated Signaling Pathways Mediating NO Production in Endothelium

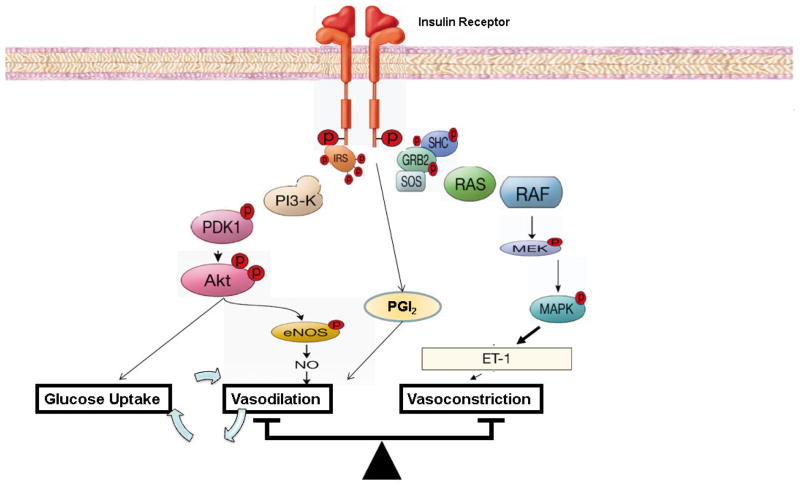

Insulin signaling pathways in endothelium regulating production of NO have been well characterized, primarily in endothelial cells in culture (Fig. 1). This pathway begins proximally with insulin binding to its receptor and culminates in the phosphorylation and activation of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS). Physiological concentrations of insulin (100 – 500 pM) can selectively activate ~ 40,000 insulin receptors (IR) on human endothelial cell surface per cell to increase NO production (Zeng and Quon, 1996). However, this response is absent in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) transfected with mutant kinase-deficient insulin receptors (Zeng, Nystrom, Ravichandran et al., 2000). Thus, increase in insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity is essential and results in phosphorylation of IRS-1 which then binds and activates PI3K (Zeng et al., 2000). Lipid products of PI3K (PI-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3)) stimulate phosphorylation and activation of PDK-1 that in turn phosphorylates and activates Akt (Montagnani, Ravichandran, Chen et al., 2002). Akt directly phosphorylates eNOS at Ser1177 resulting in increased eNOS activity and subsequent NO production (Montagnani et al., 2002). The calcium chelator BAPTA does not inhibit the ability of insulin to stimulate phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177, suggesting that insulin-induced eNOS activation is calcium-independent (Montagnani et al., 2002). Akt-mediated phosphorylation of eNOS alone is not sufficient for NO production. eNOS activity is critically controlled by calmodulin (CaM) and by binding of the molecular chaperone heat-shock protein 90 (HSP90). Insulin stimulates calmodulin and HSP90 binding to eNOS which facilitates insulin-stimulated phosphorylation and activation of eNOS at Ser1177 by Akt (Takahashi and Mendelsohn, 2003). The Ras/MAP-kinase branch of insulin-signaling pathways does not contribute significantly to activation of eNOS in response to insulin. However, inhibition of MAPK-dependent insulin signaling pathway may enhance the PI3K-dependent vascular actions of insulin on eNOS (Montagnani, Golovchenko, Kim et al., 2002). This suggests that the MAPK pathway negatively regulates the PI3K pathway.

Figure 1. Insulin signal transduction pathways regulating nitric oxide and endothelin-1 production in endothelium.

PI 3-kinase branch of insulin signaling regulates NO production and vasodilation in vascular endothelium. MAP-kinase branch of insulin signaling controls secretion of endothelin-1 (ET-1) in vascular endothelium. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; MEK, MAPK kinase; PDK, phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase.

4.2 Insulin-Stimulated Signaling Pathways Mediating ET-1 Production in Endothelium

The MAPK-dependent signaling pathways regulates insulin’s effects related to mitogenesis, growth, and differentiation. However, this pathway plays a key role in the upregulating endothelial gene expression and secretion of ET-1, a potent vasoconstrictor (Fig. 1). This signaling branch involves tyrosine-phosphorylated IRS-1 or Shc binding to the SH2 domain of Grb-2 which results in activation of the pre-associated guanosine triphosphate (GTP) exchange factor Sos. This activates the small GTP binding protein Ras, which then initiates a kinase phosphorylation cascade involving Raf, MAP-kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK), and MAP-kinase (MAPK) (Nystrom and Quon, 1999, Taniguchi, Emanuelli and Kahn, 2006). Although the precise transcription factors mediating insulin-stimulated expression of ET-1 are not known, an insulin-responsive element in the ET-1 gene has been identified (Oliver et al., 1991). Nevertheless, insulin exposure stimulates ET-1 secretion from the endothelium that peaks ~ 15–20 min that subsequently leads to sustained vasoconstriction (Hu et al., 1993).

4.3 Insulin-Stimulation of PGI2 and EDHF

Insulin acutely stimulates production of PGI2 from vascular endothelium (Sobrevia, Nadal, Yudilevich et al., 1996). NO can directly suppress activity of COX-1 and decrease both basal and stimulated release of PGI2 (Osanai, Fujita, Fujiwara et al., 2000). Inhibition of insulin-stimulated NO production using N (G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) does not prevent a PGI2 production in endothelial cells. This suggests that insulin has direct actions to stimulate PGI2 production in an NO-independent fashion (Sobrevia et al., 1996). However, insulin-signaling pathways regulating PGI2 production are yet to be elucidated. In addition to PGI2, insulin augments EDHF-evoked hyperpolarization in arterioles (Imaeda, Okayama, Okouchi et al., 2004). Interestingly, PLA2, insulin receptor, and caveolin-1 are co-localized in the caveolae and this spatial arrangement is essential for phospholipase A2-dependent EDHF formation (Graziani, Bricko, Carmignani et al., 2004, Wang, Wang and Barrett, 2011). Thus, the balance in NO, PGI2, EDHF, and ET-1 actions determines insulin’s actions on vascular tone.

5. Effects of Angiotensin II on Endothelium Derived Vasodilatory and Vasoconstrictor Factors

The vascular effects of Ang II are mediated by the activation of two heptahelical G-protein coupled membrane receptors: Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R) and type 2 (AT2R) receptor. The vasoconstrictive, hypertensive, and proliferative actions of Ang II are mediated by AT1R while AT2R activation has been suggested to counteract these effects (Mehta and Griendling, 2007, Watanabe, Barker and Berk, 2005, Lemarie and Schiffrin, 2010). Both AT1R and AT2R are expressed in endothelial cells; AT2R expression decreases following birth but is upregulated in the vasculature in pathological states. Thus, relative proportions of AT1R and AT2R in the endothelium may determine the ultimate vascular effects of Ang II (Watanabe et al., 2005, Lemarie and Schiffrin, 2010). Both AT receptors activate a wide variety of downstream signaling molecules that have been extensively characterized in VSMCs (Mehta and Griendling, 2007). However, signaling pathways mediating AT1R actions in endothelial cells are increasingly the focus of recent studies. This review will be confined to studies in the endothelium.

5.1 Signaling Pathways Mediating AT1R Activation in Endothelium

AT1R interacts with multiple heterotrimeric G proteins, including Gq/11, G12, G13, and Gi to produce signaling molecules such as inositol triphosphate, diacylglycerol, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and NO (Mehta and Griendling, 2007, Garrido and Griendling, 2009). It activates receptor tyrosine kinases (PDGF, EGFR, insulin receptor), non-receptor tyrosine kinases [Janus kinases, focal adhesion kinase, Ca2+-dependent proline-rich tyrosine kinase (Pyk2), c-Src family kinases], and serine–threonine kinases (MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; ERK, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; PKC, protein kinase C; and JNK, c-Jun N terminal kinase) (Mehta and Griendling, 2007, Touyz and Schiffrin, 2000). Many of these signaling molecules mediate AT1R-induced impairment in the release and action of endothelium-derived relaxing factors and potentiation of vasoconstrictors.

5.2 AT1 Receptor, eNOS, and NO Bioavailability

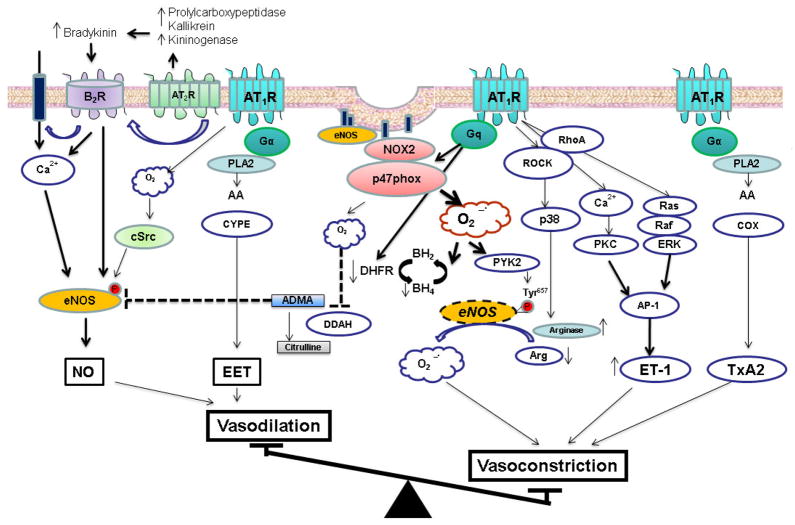

Short-term stimulation of AT1R activates eNOS while chronic stimulation suppresses eNOS activity and reduces NO bioavailability (Cai, Li, Dikalov et al., 2002, Imanishi, Kobayashi, Kuroi et al., 2006) (Fig. 2). The magnitude of NADPH oxidase mediated ROS production has been proposed to explicate these apparently discrepant actions. The mechanism(s) of NADPH oxidase activation by Ang II are complex and unclear. A functional NADPH oxidase is a multimeric enzyme that consists of NOX2, p22phox, and cytosolic subunits (p47phox, p67phox, and small G-protein, Rac) (Garrido and Griendling, 2009). Upon AT1R activation in the endothelium, caveolin-1 recruits cytosolic p47phox to caveolae to produce a functional enzyme (Lobysheva, Rath, Sekkali et al., 2011). The formation of ROS and H2O2 following NADPH activation is associated with recruitment of active c-Src and Abl to the caveolae where eNOS resides (Cai et al., 2002, Lobysheva et al., 2011). c-Src in a PI3K-dependent fashion acutely stimulates eNOS to produce NO (Fulton, Church, Ruan et al., 2005). In addition to mediating the acute NO stimulatory effects of Ang II, Src tyrosine kinase- also facilitates chronic Ang II–induced eNOS protein expression (Li, Lerea, Li et al., 2004). In addition to c-Src, Ang II activates sphingosine kinase to increase spingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) which then activates eNOS through the S1P receptor (Mulders, Hendriks-Balk, Mathy et al., 2006). Sphingosine kinase activates eNOS through the release of intracellular Ca2+ and phosphorylation of Akt and eNOS via the PI3K pathway (Mulders et al., 2006). Ang II has also been shown to induce NO production through Gq-dependent eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 (Suzuki, Eguchi, Ohtsu et al., 2006). However, these transient NO stimulatory effects of Ang II are overwhelmed by the oxidative stress that ensues with chronic Ang II stimulation of AT1R and accompanying NADPH oxidase activation.

Figure 2. Summary of endothelial signaling pathways involved in Angiotensin II modulation of vascular tone.

Angiotensin II activates AT1R and AT2R in the endothelium. Activation of the AT2R increases intracellular acidosis and plasma kallikrein levels which induces the release of bradykinin and binding to the bradykinin receptor (B2R). Bradykinin activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) to produce NO. AT1R activates NADPH oxidase, a major source for ROS production. ROS in small amounts activates cSrc that subsequently activates eNOS. Chronic AT1R activation leads to excessive ROS production that activates PYK2 to inactivate eNOS, reduces BH4 and L-arginine levels, increases cellular ADMA concentrations, and causes eNOS “uncoupling”. AT1R stimulates PKC and Ras/Raf/ERK pathway to increase ET-1 expression. Ang II-induced activation of PLA2 increases synthesis of vasodilator and vasoconstrictor prostanoids. AT1R, angiotensin II type receptor type 1; AT2R, angiotensin II type receptor type 2; EET, epoxyeicosatrienoic acid; AA, arachidonic acid; PLA2, phosholipase A2; PKC, protein kinase C; ROCK, RhoA kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PYK2; proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2; p38, p38 mitogen activated protein kinase; COX, cyclooxygenase; AP-1, activator protein-1; TxA2, thromboxane A2; NO, nitric oxide; ET-1, endothelin-1; BH4, tetrahydrobiopterin; BH2, dihydrobiopterin; ADMA, asymmetric dimethylarginine; DDAH, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; and CYPE, cytochrome P450 epoxygenase.

Chronic Ang II stimulation results in oxidative stress due to sustained and excess ROS production and reduction of anti-oxidative enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) which catalyzes the dismutation of O2− into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). This increased oxidative stress may reduce NO bioavailability by multiple mechanisms (Fig. 2). First, oxidative stress and Ang II stimulates PYK2 that subsequently inactivates NOS by phosphorylating Tyr657 in the reductase domain of the enzyme (Loot, Schreiber, Fisslthaler et al., 2009). Second, Ang II-induced oxidative stress reduces intracellular levels of essential eNOS cofactor, BH4 secondary to ROS mediated oxidation of BH4 and reduced levels of guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase I (GTPCH), the rate-limiting enzyme for BH4 synthesis and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), the enzyme mediating BH4 regeneration (Crabtree and Channon, 2011, Chalupsky and Cai, 2005). This leads to eNOS “uncoupling” where in the native eNOS dimer is uncoupled to monomers that produce significant amounts of ROS instead of NO (Gielis et al., 2011). This sets up a self-perpetuating vicious cycle leading to further reduction in NO activity and accentuated oxidative stress. Third, excess ROS reacts with NO to produce peroxynitrite that can oxidize various key intracellular proteins including eNOS to cause endothelial dysfunction (Pueyo, Arnal, Rami et al., 1998, Wattanapitayakul, Weinstein, Holycross et al., 2000). Fourth, chronic Ang II increases microvascular levels of asymmetrical dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of eNOS (Wang, Luo, Wang et al., 2010). In the endothelium, ADMA-degrading enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) is redox-sensitive (Lin, Ito, Asagami et al., 2002). Chronic Ang II-induced oxidative stress reduces microvascular DDAH expression leading to elevated ADMA levels and reduced NO bioavailability (Wang et al., 2010). Finally, Ang II increases endothelial arginase activity/expression through Gα12/13 coupled to AT1R and subsequent activation of RhoA/ROCK/p38 MAPK pathway (Shatanawi, Romero, Iddings et al., 2011). Due to colocalization of eNOS and arginase in the caveolae, increased arginase activity reduces ambient L-arginine concentrations, a key eNOS substrate. The combination of reduced substrate availability and elevations in ADMA may substantially reduce eNOS activity and NO bioavailability.

5.3 AT1 Receptor and Endothelium Derived Vasoconstrictors

Ang II stimulates endothelial ET-1 production through AT1R-mediated mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ and activation of PKC. PKC-dependent activation of the transcription factor, AP-1 that mediates preproendothelin-1 mRNA transcription (Imai, Hirata, Emori et al., 1992, Chua, Chua, Diglio et al., 1993, Stow, Jacobs, Wingo et al., 2011). Similarly, Ang II induced ROS also activates the Ras/Raf/ERK/AP-1 pathway to upregulate endothelial ET-1 gene expression (Hsu et al., 2004) (Fig. 2). Due to the tonic inhibition of ET-1 by NO, Ang II-induced reduced NO bioavailability NO augments basal and agonist-stimulated ET-1 production in endothelial cells (Bourque et al., 2011). Furthermore, ET-1 enhances endothelial angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) activity leading to enhanced generation of Ang II (Kawaguchi, Sawa and Yasuda, 1991). Moreover, ET-1 mimics many of the actions of Ang II to reduce NO bioavailability and cause endothelial dysfunction (Bourque et al., 2011). Thus, upregulation of local Ang II and ET-1 generates a self-perpetuating cycle that results in significant microvascular dysfunction.

COX-derived prostanoids and eicosanoids play an important role in regulation of vascular tone. Ang II increases COX expression in human endothelial cells in culture (Li Volti, Seta, Schwartzman et al., 2003). Chronic Ang II infusion in mice also increases endothelial COX-1 expression and activity in a ROS-dependent manner (Virdis, Colucci, Fornai et al., 2007). Increased COX-1 activity produces a contracting prostanoid, to activate VSMC TP receptors. These findings are consistent with other studies that show COX-derived vasoconstrictors mediate Ang II –induced endothelial dysfunction in an AT1R-dependent manner (Kane, Etienne-Selloum, Madeira et al., 2010, Capone, Faraco, Anrather et al., 2010, Matsumoto, Ishida, Nakayama et al., 2010, Alvarez, Perez-Giron, Hernanz et al., 2007). Ang II increases production of the prostanoid vasodilator, PGI2 (Nie, Wu, Zhang et al., 2006). However, during states of oxidative stress, peroxynitrite formed due to uncoupled eNOS inactivates PGI2 synthase (PGIS) by nitration (Nie et al., 2006). The resulting imbalance shifts Ang II-stimulated PGI2-dependent relaxation into a persistent vasoconstriction. Similarly, endothelium-derived EETs are vasodilators. Microvascular constrictor responses to Ang II are augmented by CYP epoxygenase inhibition suggesting that the metabolites of the epoxygenase pathway play an important role in modulating microvascular tone (Imig and Deichmann, 1997). Chronic treatment of endothelial cells with Ang II upregulates soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH), an enzyme that degrades EETs in the vascular wall (Ai, Fu, Guo et al., 2007). This transcriptional upregulation of endothelial sEH is mediated by AT1R activation of the transcription factor AP-1 (Ai et al., 2007). Increased sEH enhances the hydrolysis of the vasodilatory EETs in favor of enhanced vasoconstriction in metabolic states characterized by increased vascular Ang II activity. Thus, Ang II activation of AT1R leads to oxidative stress, reduced NO bioavailability, and enhanced secretion and action of ET-1 and endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor prostanoids.

5.4 AT2 Receptor, eNOS, and NO Bioavailability

AT2R activation leads to vasodilation and counteracts the vasoconstrictive effects of AT1R stimulation (Lemarie and Schiffrin, 2010, Batenburg, Garrelds, Bernasconi et al., 2004, Siragy, Inagami, Ichiki et al., 1999, Bosnyak, Welungoda, Hallberg et al., 2010) (Fig. 2). In the presence of AT1R blocker, Ang II augments vasodilation that is sensitive to inhibition of AT2R, bradykinin B2 receptor (B2R), and eNOS (Batenburg et al., 2004, Carey, 2005, Cosentino, Savoia, De Paolis et al., 2005, Gohlke, Pees and Unger, 1998, Katada and Majima, 2002, Seyedi, Xu, Nasjletti et al., 1995, Tsutsumi, Matsubara, Masaki et al., 1999). AT2R activation increases intracellular acidosis, stimulates kininogenases, and elevates bradykinin formation in the endothelium (Tsutsumi et al., 1999). Bradykinin then binds to B2R to activate eNOS and NO formation. Prolylcarboxypeptidase is a plasma prekallikrein activator in endothelial cells that increases plasma kallikrein (Shariat-Madar, Mahdi and Schmaier, 2002). Plasma kallikrein cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen to liberate kinins such as bradykinin (Zhu, Carretero, Liao et al., 2010). Activation or overexpression of AT2R in the endothelium increases prolylcarboxypeptidase activity that leads to bradykinin formation (Zhu et al., 2010). Vasodilatory actions of Ang II are thus more pronounced in conditions characterized by increased AT2R expression. In addition to antagonizing AT1R-mediated vasoconstrictor actions through enhanced NO release, AT2R form homo-or hetero-dimers with AT1R. Dimerization of AT2R with AT1R or B2R, enhances vasodilation (Abadir, Periasamy, Carey et al., 2006, AbdAlla, Lother, Abdel-tawab et al., 2001). Thus, the relative activity and endothelial expression of AT1R and AT2R shape the magnitude of vasodilator response to Ang II.

6. Effects of Insulin and Angiotensin II on Skeletal Muscle Microvasculature and Glucose Disposal

6.1 Insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle capillary recruitment and glucose disposal

As discussed previously, PI3K-dependent insulin signaling pathways in vascular endothelium, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue regulate vasodilator and metabolic actions of insulin. However, MAPK-dependent insulin signaling pathways tend to promote pro-hypertensive and pro-atherogenic actions of insulin in various tissues. In humans, intravenous insulin infusion stimulates capillary recruitment, vasodilation, and increased blood flow in an NO-dependent fashion (Vincent et al., 2004). In the initial few minutes of insulin exposure, dilation of terminal arterioles increases the number of perfused capillaries (capillary recruitment). This is followed by relaxation of larger resistance vessels that increases overall limb blood flow (maximum flow reached after 2 h) (Baron and Clark, 1997). Increasing arterial plasma insulin levels to ~ 300 pM in human forearm results in a 25% increase in capillary blood volume in the deep flexor muscles (Coggins, Lindner, Rattigan et al., 2001). Similarly, in a more physiologic setting, microvascular volume in human forearm increases by ~ 45% an hour after a mixed meal (Vincent, Clerk, Lindner et al., 2006). Thus, after a mixed meal, an oral glucose load, or infusion of insulin, recruitment of capillaries expands the capillary surface area and increases muscle blood flow which together substantially increase glucose and insulin delivery. Inhibitors of NOS that block insulin-mediated capillary recruitment cause a concomitant 40% reduction in glucose disposal (Vicent et al., 2003, Vincent et al., 2004). Thus, PI3K-dependent vascular actions of insulin directly promote glucose uptake in skeletal muscle.

6.2 Angiotensin II, skeletal muscle capillary recruitment, and glucose disposal

The effects of Ang II on human microcirculation has not been studied. Local infusions of Ang II increase oxygen uptake and glucose metabolism in rat skeletal muscle (Chai et al., 2010, Zhang, Newman, Richards et al., 2005, Rattigan, Dora, Tong et al., 1996, Newman, Rattigan and Clark, 2002). This effect of Ang II is attributed to increases in “nutritive” flow secondary to redistribution of microvascular flow supplying skeletal muscle cells (Rattigan et al., 1996, Newman et al., 2002). Using contrast-enhanced ultrasound technique, Chai et al. have examined the roles of AT1 and AT2 receptors on microvascular blood flow in rat skeletal muscle (Chai et al., 2010). Ang II infusions at non-pressor or pressor doses increases hind limb microvascular blood flow. AT1R blockade with losartan during systemic Ang II infusion increases hind limb microvascular blood flow and glucose extraction in a NO-dependent fashion suggesting a role for unopposed AT2R activation in mediating this effect. Indeed, co-infusion of AT2R antagonist, PD123319 significantly inhibited Ang II-induced microvascular dilation and hind limb glucose uptake. These findings suggest that acute effects of Ang II on glucose disposal are mediated by endothelial activation of AT2R and in the normal state, it appears that AT2R, and not AT1 exerts a dominant effect on rat skeletal muscle microvasculature (Chai et al., 2010).

The role of AT2R in human skeletal muscle microcirculation remains to be clarified. Local infusion of telmisartan (AT1R blocker) or PD 123319 (AT2R blocker) results in mild increases in forearm blood flow in humans. Moreover, infusion of either telmisartan or PD 123319 attenuates Ang II-induced vasoconstrictor response (Schinzari, Tesauro, Rovella et al., 2011), suggesting that AT2R mediates vasoconstriction. Similarly, blockade of AT2R in internal mammary arteries from patients with coronary artery disease reduces the vasoconstrictor effect of Ang II (van de Wal, van der Harst, Wagenaar et al., 2007). These results together suggest that AT2R like AT1R mediates basal and Ang II evoked vasoconstrictive tone in humans. Interestingly, in the same study, CGP 42112A, an AT2R-agonist results in a NO-dependent vasodilation (Schinzari et al., 2011). These divergent vascular responses are thought to be due to cell-specific AT2R activation in smooth muscle and endothelial cells that mediates vasoconstriction and vasodilation, respectively. Consequently, increases in interstitial Ang II may augment vascular tone through AT1R and AT2R, while circulating Ang II may decrease vascular tone through AT2R activation (Schinzari et al., 2011). However, this assumption needs further evaluation in human microvasculature.

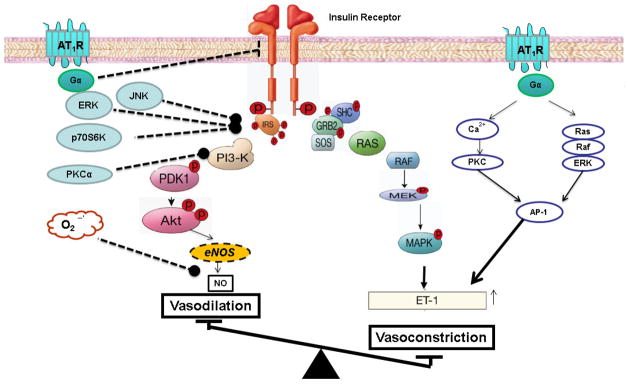

7. Angiotensin II and Pathway-Selective Insulin Resistance in the Endothelium

A key feature of insulin resistance is that it is characterized by specific impairment in PI3K-dependent signaling pathways, whereas other insulin-signaling branches including Ras/MAPK-dependent pathways are unaffected (Jiang, Lin, Clemont et al., 1999, Cusi, Maezono, Osman et al., 2000) (Fig. 3). In the endothelium, hyperinsulinemia will overdrive unaffected MAPK-dependent pathways leading to an imbalance between PI3K- and MAPK-dependent functions of insulin. Chronic Ang II exposure and action has been proposed to play a causal role in vascular insulin resistance (Cooper et al., 2007, Kobayashi et al., 2008, Zhou, Schulman and Raij, 2009, Manrique, Lastra, Gardner et al., 2009). Chronic activation of AT1R leads to endothelial dysfunction by increasing oxidative stress, reduced NO bioavailability, impaired generation of endothelium-derived vasodilators, and increased release and action of vasoconstrictors. Each of these actions of Ang II can independently impair the vasodilatory actions of insulin in the microvasculature. In addition to these deleterious actions, Ang II directly impairs insulin signaling pathways in the endothelium (Kim, Jang, Martinez-Lemus et al., 2012, Maeno, Li, Park et al., 2012, Andreozzi, Laratta, Sciacqua et al., 2004, Oh, Ha, Lee et al., 2011, Presta, Tassone, Andreozzi et al., 2011).

Figure 3. Signaling pathways mediating angiotensin II-induced pathway selective insulin resistance in PI3K signaling.

Stimulation of AT1R activates PKC, ERK, JNK, and p70S6K to inhibit IRS/PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Increased oxidative stress “uncouples” eNOS and reduces NO bioavailability. Chronic activation of AT1R decreases NO production, increases endothelial ET-1 expression, and creates an imbalance between vasodilator and vasoconstrictor actions of insulin. AT1R, angiotensin II type receptor type 1; PKC, protein kinase C; IRS, insulin receptor substrate; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; JNK, C-Jun N-terminal kinase; p70S6K, p70 ribosomal S6 kinase; AP-1, activator protein-1; NO, nitric oxide; and ET-1, endothelin-1.

The insulin signaling pathways contains three critical nodes that play an important role in crosstalk with other signaling pathways (Fig. 3). These nodes include, the insulin receptor and its substrates (IRS 1–4), PI3K with its several regulatory and catalytic subunits, and the three AKT isoforms (Taniguchi et al., 2006). Ang II impairs the activity and interaction of these critical nodes in the endothelium. Treatment of bovine aortic endothelial cells with Ang II decreases the number of insulin receptors (IR) in the membrane (Oh et al., 2011). Although, the intracellular mechanisms mediating the reduction in IR are yet to be elucidated, this effect was reversed by ATR blocker. One of the molecular mechanisms for impaired insulin action is increased phosphorylation of IRS-1 at inhibitory serine (Ser) residues (Taniguchi et al., 2006). Phosphorylation of Ser residues appears to interfere with the functional domains of IRS-1. In human umbilical venous endothelial cells (HUVECs), Ang II increases phosphorylation at Ser312 and Ser616 of IRS-1 by JNK and ERK1/2, respectively. This increase in inhibitory Ser phosphorylation was associated with impaired interaction with the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K and consequently reduced activation of Akt and eNOS (Andreozzi et al., 2004). This inhibitory action of Ang II was mediated by the activation of AT1R, while inhibition of AT2R did not modulate insulin activated IRS/PI3k/Akt/eNOS pathway (Andreozzi et al., 2004, Presta et al., 2011). Similarly, Ang II activates mTOR/p70S6K, leading to phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Ser636/639 and inhibition of insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of eNOS (Kim et al., 2012). It appears that AT1R activation stimulates the mTOR/p70S6K pathway through transactivation of EGFR. Interestingly, NADPH oxidase inhibitors, abrogate Ang II stimulation of mTOR/p70S6K pathway, suggesting a key role for ROS in impaired insulin action in the endothelium. However, in contrast to Ang II-mediated activation of JNK and ERK, which occurred rapidly (<30 min) (Andreozzi et al., 2004, Presta et al., 2011), activation of mTOR/p70S6K pathway required a longer exposure of Ang II (~ 4 hr) (Kim et al., 2012). Moreover, the longer exposure to Ang II was not only associated with increased Ser phosphorylation of IRS-1 but also increased degradation of IRS-1 (presumably ubiquitin-dependent). These findings suggest that Ang II modulates insulin signaling in the endothelium in a time-dependent fashion. Recent study suggests that Ang II also modulates PI3K, another key node for insulin signaling (Maeno et al., 2012). The p85 subunit, a regulatory subunit of PI3K, is critical for interaction with IRS-1(Taniguchi et al., 2006). In endothelial cells, Ang II causes insulin resistance by activating PKC that subsequently phosphorylates Thr86 in p85α of PI3K. This inhibitory phosphorylation leads to reduced insulin activation of Akt/eNOS in endothelial cells. Thus, Ang II directly inhibits key signaling molecules in the insulin signaling pathway to selectively impair PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway resulting in impaired vasodilation and enhanced vasoconstriction that may also lead to impaired insulin-mediated glucose disposal.

8. Effects of Angiotensin II on Insulin-Stimulated Skeletal Muscle Microvasculature and Glucose Disposal

Insulin increases skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion to augment glucose disposal. Chronic activation of RAAS has been proposed to play a role in insulin resistance (Cooper et al., 2007, Lastra-Lastra et al., 2009, Manrique et al., 2009). AT1R blockade with losartan during concomitant insulin infusion in rats increases insulin-mediated skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion but with no significant effect on glucose disposal (Chai et al., 2011). In contrast, AT2R blockade with PD123319, abrogates insulin-induced increases in capillary recruitment and attenuates glucose disposal (Chai et al., 2011). It appears that PD123319 decreases skeletal muscle uptake by decreasing interstitial insulin levels. These results suggest an important role for AT2R in the microvascular actions of insulin. However, the roles of RAS activation and AT receptors in insulin-mediated skeletal muscle capillary recruitment in normal and insulin-resistant states are unknown at this time.

ACE inhibitors and ARB increase insulin mediated glucose disposal in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance, obesity, hypertension or type 2 diabetes mellitus (van der Zijl, Moors, Goossens et al., 2011, Andraws and Brown, 2007, Bosch, Yusuf, Gerstein et al., 2006, Elliott and Meyer, 2007, Paolisso, Balbi, Gambardella et al., 1995, Tocci, Paneni, Palano et al., 2011, Zandbergen, Lamberts, Janssen et al., 2006). In contrast to these observations, acute increases in circulating Ang II levels in healthy individuals augments insulin-mediated glucose disposal (Buchanan, Thawani, Kades et al., 1993, Fliser, Arnold, Kohl et al., 1993, Jamerson, Nesbitt, Amerena et al., 1996, Townsend and DiPette, 1993, Widgren, Urbanavicius, Wikstrand et al., 1993). Thus it appears that the seemingly paradoxical effects of Ang II may be dependent on the duration (acute vs. chronic) and the source of Ang II (interstitial vs. systemic). Whether ACE inhibitors/ARBs affect insulin-induced capillary recruitment in human skeletal muscle is not known. However, chronic administration of quinapril partially reversed impairment in insulin-evoked capillary recruitment and glucose disposal in insulin-resistant Zucker obese rats (Clerk, Vincent, Barrett et al., 2007). Enhanced vasoconstriction is determined by interstitial rather than circulating Ang II (Widdop, Jones, Hannan et al., 2003, Saris, van Dijk, Kroon et al., 2000). Indeed, increasing skeletal muscle Ang II levels (by microdialysis technique) decreases microvascular blood flow in a dose-dependent manner in humans (Goossens, Blaak, Saris et al., 2004). Local RAS activity is increased in insulin resistant states such as obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Luther and Brown, 2011). Consequently, ACE inhibitors or AT1R blockers may augment insulin action by decreasing vasoconstrictor tone, reducing oxidative stress, and attenuating insulin resistance. However, in conditions accompanying systemic increases in Ang II such as during chronic treatment with AT1R blockers (Levy, 2004) or acute peripheral infusions of Ang II, AT2R-mediated vasodilation, as observed in rodents, may play a predominant role in insulin-mediated capillary recruitment and glucose disposal. Clearly these hypotheses need further evaluation in human skeletal muscle microvasculature both in insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant states.

9. Conclusions

Vasodilator actions of insulin are mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase dependent insulin signaling pathways in endothelium, which stimulate production of nitric oxide. Insulin-stimulated nitric oxide mediates capillary recruitment, vasodilation, increased blood flow, and subsequent augmentation of glucose disposal in skeletal muscle. Pathway-specific impairment of PI3K-dependent insulin signaling pathway leads to metabolic dysfunction and microvascular dysfunction. Similarly, Ang II acts on AT2 receptor to cause vasodilation and augment insulin-mediated glucose disposal. In contrast, AT1 receptor activation leads to vasoconstriction, reduced nitric oxide bioavailability, impaired insulin signaling, and insulin resistance. Therapeutic interventions that target the pathway-selective impairment in insulin signaling and the imbalance in AT1 and AT2 receptor signaling in microvascular endothelium may simultaneously ameliorate endothelial dysfunction and insulin resistance.

Highlights.

Vasodilatory actions of insulin in the microvasculature augments glucose disposal.

Angiotensin II regulates microvascular perfusion and insulin-mediated glucose disposal.

Chronic activation of angiotensin type 1 receptor impairs vasodilatory actions of insulin.

Targeting the imbalance in angiotensin II signaling may ameliorate endothelial dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, NIDDK, NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:173–94. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Savage DB, Bilz S, Solomon G, Yonemitsu S, Cline GW, Befroy D, Zemany L, Kahn BB, Papademetris X, Rothman DL, Shulman GI. The role of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12587–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705408104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron AD, Clark MG. Role of blood flow in the regulation of muscle glucose uptake. Annu Rev Nutr. 1997;17:487–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.17.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark MG. Impaired microvascular perfusion: a consequence of vascular dysfunction and a potential cause of insulin resistance in muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E732–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90477.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark MG, Colquhoun EQ, Rattigan S, Dora KA, Eldershaw TP, Hall JL, Ye J. Vascular and endocrine control of muscle metabolism. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:E797–812. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.5.E797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark MG, Wallis MG, Barrett EJ, Vincent MA, Richards SM, Clerk LH, Rattigan S. Blood flow and muscle metabolism: a focus on insulin action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E241–58. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00408.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrett EJ, Wang H, Upchurch CT, Liu Z. Insulin regulates its own delivery to skeletal muscle by feed-forward actions on the vasculature. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E252–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00186.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muniyappa R, Montagnani M, Koh KK, Quon MJ. Cardiovascular actions of insulin. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:463–91. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vicent D, Ilany J, Kondo T, Naruse K, Fisher SJ, Kisanuki YY, Bursell S, Yanagisawa M, King GL, Kahn CR. The role of endothelial insulin signaling in the regulation of vascular tone and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1373–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI15211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vincent MA, Clerk LH, Lindner JR, Klibanov AL, Clark MG, Rattigan S, Barrett EJ. Microvascular recruitment is an early insulin effect that regulates skeletal muscle glucose uptake in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53:1418–23. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.6.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Vincent MA, Richards SM, Clerk LH, Rattigan S, Clark MG, Barrett EJ. Insulin sensitivity of muscle capillary recruitment in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53:447–53. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natali A, Taddei S, Quinones Galvan A, Camastra S, Baldi S, Frascerra S, Virdis A, Sudano I, Salvetti A, Ferrannini E. Insulin sensitivity, vascular reactivity, and clamp-induced vasodilatation in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1997;96:849–55. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baron AD, Laakso M, Brechtel G, Edelman SV. Mechanism of insulin resistance in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a major role for reduced skeletal muscle blood flow. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73:637–43. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-3-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chai W, Wang W, Dong Z, Cao W, Liu Z. Angiotensin II receptors modulate muscle microvascular and metabolic responses to insulin in vivo. Diabetes. 2011;60:2939–46. doi: 10.2337/db10-1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chai W, Wang W, Liu J, Barrett EJ, Carey RM, Cao W, Liu Z. Angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptors regulate basal skeletal muscle microvascular volume and glucose use. Hypertension. 2010;55:523–30. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper SA, Whaley-Connell A, Habibi J, Wei Y, Lastra G, Manrique C, Stas S, Sowers JR. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and oxidative stress in cardiovascular insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2009–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00522.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lastra-Lastra G, Sowers JR, Restrepo-Erazo K, Manrique-Acevedo C, Lastra-Gonzalez G. Role of aldosterone and angiotensin II in insulin resistance: an update. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;71:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segal SS. Regulation of blood flow in the microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2005;12:33–45. doi: 10.1080/10739680590895028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renkin EM, Rosell S. Effects of different types of vasodilator mechanisms on vascular tonus and on transcapillary exchange of diffusible material in skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1962;54:241–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1962.tb02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron AD, Tarshoby M, Hook G, Lazaridis EN, Cronin J, Johnson A, Steinberg HO. Interaction between insulin sensitivity and muscle perfusion on glucose uptake in human skeletal muscle: evidence for capillary recruitment. Diabetes. 2000;49:768–74. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michel T, Feron O. Nitric oxide synthases: which, where, how, and why? J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2146–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI119750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michel T, Vanhoutte PM. Cellular signaling and NO production. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:807–16. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0765-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dessy C, Feron O, Balligand JL. The regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by caveolin: a paradigm validated in vivo and shared by the ‘endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor’. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:817–27. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0815-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duran WN, Breslin JW, Sanchez FA. The NO cascade, eNOS location, and microvascular permeability. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:254–61. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleming I. Molecular mechanisms underlying the activation of eNOS. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:793–806. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0767-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crabtree MJ, Channon KM. Synthesis and recycling of tetrahydrobiopterin in endothelial function and vascular disease. Nitric Oxide. 2011;25:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gielis JF, Lin JY, Wingler K, Van Schil PE, Schmidt HH, Moens AL. Pathogenetic role of eNOS uncoupling in cardiopulmonary disorders. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:765–76. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bos CL, Richel DJ, Ritsema T, Peppelenbosch MP, Versteeg HH. Prostanoids and prostanoid receptors in signal transduction. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1187–205. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang EH, Leung FP, Huang Y, Feletou M, So KF, Man RY, Vanhoutte PM. Calcium and reactive oxygen species increase in endothelial cells in response to releasers of endothelium-derived contracting factor. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:15–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garavito RM, DeWitt DL. The cyclooxygenase isoforms: structural insights into the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1441:278–87. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vane JR, Bakhle YS, Botting RM. Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1998;38:97–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidge ST. Prostaglandin H synthase and vascular function. Circ Res. 2001;89:650–60. doi: 10.1161/hh2001.098351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harlan JM, Callahan KS. Role of hydrogen peroxide in the neutrophil-mediated release of prostacyclin from cultured endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:442–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI111440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfister SL, Gauthier KM, Campbell WB. Vascular pharmacology of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Adv Pharmacol. 2010;60:27–59. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385061-4.00002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baylie RL, Brayden JE. TRPV channels and vascular function. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2011;203:99–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feletou M, Huang Y, Vanhoutte PM. Vasoconstrictor prostanoids. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:941–50. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0812-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marasciulo FL, Montagnani M, Potenza MA. Endothelin-1: the yin and yang on vascular function. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:1655–65. doi: 10.2174/092986706777441968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khimji AK, Rockey DC. Endothelin--biology and disease. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1615–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goel A, Su B, Flavahan S, Lowenstein CJ, Berkowitz DE, Flavahan NA. Increased endothelial exocytosis and generation of endothelin-1 contributes to constriction of aged arteries. Circ Res. 2010;107:242–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu YH, Chen JJ, Chang NC, Chen CH, Liu JC, Chen TH, Jeng CJ, Chao HH, Cheng TH. Role of reactive oxygen species-sensitive extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in angiotensin II-induced endothelin-1 gene expression in vascular endothelial cells. J Vasc Res. 2004;41:64–74. doi: 10.1159/000076247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hu RM, Levin ER, Pedram A, Frank HJ. Insulin stimulates production and secretion of endothelin from bovine endothelial cells. Diabetes. 1993;42:351–8. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kobayashi T, Nogami T, Taguchi K, Matsumoto T, Kamata K. Diabetic state, high plasma insulin and angiotensin II combine to augment endothelin-1-induced vasoconstriction via ETA receptors and ERK. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:974–83. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliver FJ, de la Rubia G, Feener EP, Lee ME, Loeken MR, Shiba T, Quertermous T, King GL. Stimulation of endothelin-1 gene expression by insulin in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bourque SL, Davidge ST, Adams MA. The interaction between endothelin-1 and nitric oxide in the vasculature: new perspectives. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R1288–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00397.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prins BA, Hu RM, Nazario B, Pedram A, Frank HJ, Weber MA, Levin ER. Prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin inhibit the production and secretion of endothelin from cultured endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11938–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verhaar MC, Strachan FE, Newby DE, Cruden NL, Koomans HA, Rabelink TJ, Webb DJ. Endothelin-A receptor antagonist-mediated vasodilatation is attenuated by inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis and by endothelin-B receptor blockade. Circulation. 1998;97:752–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zeng G, Quon MJ. Insulin-stimulated production of nitric oxide is inhibited by wortmannin. Direct measurement in vascular endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:894–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI118871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng G, Nystrom FH, Ravichandran LV, Cong LN, Kirby M, Mostowski H, Quon MJ. Roles for insulin receptor, PI3-kinase, and Akt in insulin-signaling pathways related to production of nitric oxide in human vascular endothelial cells. Circulation. 2000;101:1539–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.13.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montagnani M, Ravichandran LV, Chen H, Esposito DL, Quon MJ. Insulin receptor substrate-1 and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 are required for insulin-stimulated production of nitric oxide in endothelial cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:1931–42. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi S, Mendelsohn ME. Synergistic activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) by HSP90 and Akt: calcium-independent eNOS activation involves formation of an HSP90-Akt-CaM-bound eNOS complex. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30821–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montagnani M, Golovchenko I, Kim I, Koh GY, Goalstone ML, Mundhekar AN, Johansen M, Kucik DF, Quon MJ, Draznin B. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase enhances mitogenic actions of insulin in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1794–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nystrom FH, Quon MJ. Insulin signalling: metabolic pathways and mechanisms for specificity. Cell Signal. 1999;11:563–74. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:85–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sobrevia L, Nadal A, Yudilevich DL, Mann GE. Activation of L-arginine transport (system y+) and nitric oxide synthase by elevated glucose and insulin in human endothelial cells. J Physiol. 1996;490(Pt 3):775–81. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osanai T, Fujita N, Fujiwara N, Nakano T, Takahashi K, Guan W, Okumura K. Cross talk of shear-induced production of prostacyclin and nitric oxide in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H233–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Imaeda K, Okayama N, Okouchi M, Omi H, Kato T, Akao M, Imai S, Uranishi H, Takeuchi Y, Ohara H, Fukutomi T, Joh T, Itoh M. Effects of insulin on the acetylcholine-induced hyperpolarization in the guinea pig mesenteric arterioles. J Diabetes Complications. 2004;18:356–62. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(03)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Graziani A, Bricko V, Carmignani M, Graier WF, Groschner K. Cholesterol- and caveolin-rich membrane domains are essential for phospholipase A2-dependent EDHF formation. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:234–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang H, Wang AX, Barrett EJ. Caveolin-1 is required for vascular endothelial insulin uptake. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E134–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00498.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watanabe T, Barker TA, Berk BC. Angiotensin II and the endothelium: diverse signals and effects. Hypertension. 2005;45:163–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153321.13792.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lemarie CA, Schiffrin EL. The angiotensin II type 2 receptor in cardiovascular disease. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2010;11:19–31. doi: 10.1177/1470320309347785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garrido AM, Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases and angiotensin II receptor signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;302:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Signal transduction mechanisms mediating the physiological and pathophysiological actions of angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:639–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cai H, Li Z, Dikalov S, Holland SM, Hwang J, Jo H, Dudley SC, Jr, Harrison DG. NAD(P)H oxidase-derived hydrogen peroxide mediates endothelial nitric oxide production in response to angiotensin II. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48311–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imanishi T, Kobayashi K, Kuroi A, Mochizuki S, Goto M, Yoshida K, Akasaka T. Effects of angiotensin II on NO bioavailability evaluated using a catheter-type NO sensor. Hypertension. 2006;48:1058–65. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000248920.16956.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lobysheva I, Rath G, Sekkali B, Bouzin C, Feron O, Gallez B, Dessy C, Balligand JL. Moderate caveolin-1 downregulation prevents NADPH oxidase-dependent endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling by angiotensin II in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2098–105. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.230623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fulton D, Church JE, Ruan L, Li C, Sood SG, Kemp BE, Jennings IG, Venema RC. Src kinase activates endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by phosphorylating Tyr-83. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35943–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li X, Lerea KM, Li J, Olson SC. Src kinase mediates angiotensin II-dependent increase in pulmonary endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:365–72. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0098OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mulders AC, Hendriks-Balk MC, Mathy MJ, Michel MC, Alewijnse AE, Peters SL. Sphingosine kinase-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by angiotensin II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2043–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000237569.95046.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suzuki H, Eguchi K, Ohtsu H, Higuchi S, Dhobale S, Frank GD, Motley ED, Eguchi S. Activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5914–20. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Loot AE, Schreiber JG, Fisslthaler B, Fleming I. Angiotensin II impairs endothelial function via tyrosine phosphorylation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2889–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chalupsky K, Cai H. Endothelial dihydrofolate reductase: critical for nitric oxide bioavailability and role in angiotensin II uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9056–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409594102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pueyo ME, Arnal JF, Rami J, Michel JB. Angiotensin II stimulates the production of NO and peroxynitrite in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C214–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.1.C214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wattanapitayakul SK, Weinstein DM, Holycross BJ, Bauer JA. Endothelial dysfunction and peroxynitrite formation are early events in angiotensin-induced cardiovascular disorders. Faseb J. 2000;14:271–8. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang D, Luo Z, Wang X, Jose PA, Falck JR, Welch WJ, Aslam S, Teerlink T, Wilcox CS. Impaired endothelial function and microvascular asymmetrical dimethylarginine in angiotensin II-infused rats: effects of tempol. Hypertension. 2010;56:950–5. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.157115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin KY, Ito A, Asagami T, Tsao PS, Adimoolam S, Kimoto M, Tsuji H, Reaven GM, Cooke JP. Impaired nitric oxide synthase pathway in diabetes mellitus: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation. 2002;106:987–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027109.14149.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shatanawi A, Romero MJ, Iddings JA, Chandra S, Umapathy NS, Verin AD, Caldwell RB, Caldwell RW. Angiotensin II-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction through RhoA/Rho kinase/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/arginase pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C1181–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00328.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Imai T, Hirata Y, Emori T, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T, Marumo F. Induction of endothelin-1 gene by angiotensin and vasopressin in endothelial cells. Hypertension. 1992;19:753–7. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chua BH, Chua CC, Diglio CA, Siu BB. Regulation of endothelin-1 mRNA by angiotensin II in rat heart endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1178:201–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90010-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stow LR, Jacobs ME, Wingo CS, Cain BD. Endothelin-1 gene regulation. Faseb J. 2011;25:16–28. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-161612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawaguchi H, Sawa H, Yasuda H. Effect of endothelin on angiotensin converting enzyme activity in cultured pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J Hypertens. 1991;9:171–4. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199102000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li Volti G, Seta F, Schwartzman ML, Nasjletti A, Abraham NG. Heme oxygenase attenuates angiotensin II-mediated increase in cyclooxygenase-2 activity in human femoral endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2003;41:715–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000049163.23426.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Virdis A, Colucci R, Fornai M, Duranti E, Giannarelli C, Bernardini N, Segnani C, Ippolito C, Antonioli L, Blandizzi C, Taddei S, Salvetti A, Del Tacca M. Cyclooxygenase-1 is involved in endothelial dysfunction of mesenteric small arteries from angiotensin II-infused mice. Hypertension. 2007;49:679–86. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000253085.56217.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kane MO, Etienne-Selloum N, Madeira SV, Sarr M, Walter A, Dal-Ros S, Schott C, Chataigneau T, Schini-Kerth VB. Endothelium-derived contracting factors mediate the Ang II-induced endothelial dysfunction in the rat aorta: preventive effect of red wine polyphenols. Pflugers Arch. 2010;459:671–9. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0759-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Capone C, Faraco G, Anrather J, Zhou P, Iadecola C. Cyclooxygenase 1-derived prostaglandin E2 and EP1 receptors are required for the cerebrovascular dysfunction induced by angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2010;55:911–7. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Matsumoto T, Ishida K, Nakayama N, Taguchi K, Kobayashi T, Kamata K. Mechanisms underlying the losartan treatment-induced improvement in the endothelial dysfunction seen in mesenteric arteries from type 2 diabetic rats. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62:271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alvarez Y, Perez-Giron JV, Hernanz R, Briones AM, Garcia-Redondo A, Beltran A, Alonso MJ, Salaices M. Losartan reduces the increased participation of cyclooxygenase-2-derived products in vascular responses of hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:381–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.115287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nie H, Wu JL, Zhang M, Xu J, Zou MH. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent tyrosine nitration of prostacyclin synthase in diabetes in vivo. Diabetes. 2006;55:3133–41. doi: 10.2337/db06-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Imig JD, Deichmann PC. Afferent arteriolar responses to ANG II involve activation of PLA2 and modulation by lipoxygenase and P-450 pathways. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F274–82. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.2.F274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ai D, Fu Y, Guo D, Tanaka H, Wang N, Tang C, Hammock BD, Shyy JY, Zhu Y. Angiotensin II up-regulates soluble epoxide hydrolase in vascular endothelium in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9018–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703229104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Batenburg WW, Garrelds IM, Bernasconi CC, Juillerat-Jeanneret L, van Kats JP, Saxena PR, Danser AH. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor-mediated vasodilation in human coronary microarteries. Circulation. 2004;109:2296–301. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000128696.12245.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Siragy HM, Inagami T, Ichiki T, Carey RM. Sustained hypersensitivity to angiotensin II and its mechanism in mice lacking the subtype-2 (AT2) angiotensin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6506–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bosnyak S, Welungoda IK, Hallberg A, Alterman M, Widdop RE, Jones ES. Stimulation of angiotensin AT2 receptors by the non-peptide agonist, Compound 21, evokes vasodepressor effects in conscious spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:709–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00575.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carey RM. Cardiovascular and renal regulation by the angiotensin type 2 receptor: the AT2 receptor comes of age. Hypertension. 2005;45:840–4. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000159192.93968.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cosentino F, Savoia C, De Paolis P, Francia P, Russo A, Maffei A, Venturelli V, Schiavoni M, Lembo G, Volpe M. Angiotensin II type 2 receptors contribute to vascular responses in spontaneously hypertensive rats treated with angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonists. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:493–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gohlke P, Pees C, Unger T. AT2 receptor stimulation increases aortic cyclic GMP in SHRSP by a kinin-dependent mechanism. Hypertension. 1998;31:349–55. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Katada J, Majima M. AT(2) receptor-dependent vasodilation is mediated by activation of vascular kinin generation under flow conditions. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:484–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seyedi N, Xu X, Nasjletti A, Hintze TH. Coronary kinin generation mediates nitric oxide release after angiotensin receptor stimulation. Hypertension. 1995;26:164–70. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tsutsumi Y, Matsubara H, Masaki H, Kurihara H, Murasawa S, Takai S, Miyazaki M, Nozawa Y, Ozono R, Nakagawa K, Miwa T, Kawada N, Mori Y, Shibasaki Y, Tanaka Y, Fujiyama S, Koyama Y, Fujiyama A, Takahashi H, Iwasaka T. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor overexpression activates the vascular kinin system and causes vasodilation. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:925–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI7886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shariat-Madar Z, Mahdi F, Schmaier AH. Identification and characterization of prolylcarboxypeptidase as an endothelial cell prekallikrein activator. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17962–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhu L, Carretero OA, Liao TD, Harding P, Li H, Sumners C, Yang XP. Role of prolylcarboxypeptidase in angiotensin II type 2 receptor-mediated bradykinin release in mouse coronary artery endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2010;56:384–90. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.155051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Abadir PM, Periasamy A, Carey RM, Siragy HM. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor-bradykinin B2 receptor functional heterodimerization. Hypertension. 2006;48:316–22. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000228997.88162.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.AbdAlla S, Lother H, Abdel-tawab AM, Quitterer U. The angiotensin II AT2 receptor is an AT1 receptor antagonist. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39721–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Coggins M, Lindner J, Rattigan S, Jahn L, Fasy E, Kaul S, Barrett E. Physiologic hyperinsulinemia enhances human skeletal muscle perfusion by capillary recruitment. Diabetes. 2001;50:2682–90. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vincent MA, Clerk LH, Lindner JR, Price WJ, Jahn LA, Leong-Poi H, Barrett EJ. Mixed meal and light exercise each recruit muscle capillaries in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E1191–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00497.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang L, Newman JM, Richards SM, Rattigan S, Clark MG. Microvascular flow routes in muscle controlled by vasoconstrictors. Microvasc Res. 2005;70:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rattigan S, Dora KA, Tong AC, Clark MG. Perfused skeletal muscle contraction and metabolism improved by angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E96–103. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.1.E96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Newman JM, Rattigan S, Clark MG. Nutritive blood flow improves interstitial glucose and lactate exchange in perfused rat hindlimb. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H186–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01024.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schinzari F, Tesauro M, Rovella V, Adamo A, Mores N, Cardillo C. Coexistence of functional angiotensin II type 2 receptors mediating both vasoconstriction and vasodilation in humans. J Hypertens. 2011;29:1743–8. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328349ae0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.van de Wal RM, van der Harst P, Wagenaar LJ, Wassmann S, Morshuis WJ, Nickenig G, Buikema H, Plokker HW, van Veldhuisen DJ, van Gilst WH, Voors AA. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor vasoactivity in internal mammary arteries of patients with coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:372–9. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31811ea222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jiang ZY, Lin YW, Clemont A, Feener EP, Hein KD, Igarashi M, Yamauchi T, White MF, King GL. Characterization of selective resistance to insulin signaling in the vasculature of obese Zucker (fa/fa) rats. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:447–57. doi: 10.1172/JCI5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cusi K, Maezono K, Osman A, Pendergrass M, Patti ME, Pratipanawatr T, DeFronzo RA, Kahn CR, Mandarino LJ. Insulin resistance differentially affects the PI 3-kinase- and MAP kinase-mediated signaling in human muscle. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:311–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI7535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zhou MS, Schulman IH, Raij L. Role of angiotensin II and oxidative stress in vascular insulin resistance linked to hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H833–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01096.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Manrique C, Lastra G, Gardner M, Sowers JR. The renin angiotensin aldosterone system in hypertension: roles of insulin resistance and oxidative stress. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:569–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kim JA, Jang HJ, Martinez-Lemus LA, Sowers JR. Activation of mTOR/p70S6 kinase by ANG II inhibits insulin-stimulated endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vasodilation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E201–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00497.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Maeno Y, Li Q, Park K, Rask-Madsen C, Gao B, Matsumoto M, Liu Y, Wu IH, White MF, Feener EP, King GL. Inhibition of Insulin Signaling in Endothelial Cells by Protein Kinase C-induced Phosphorylation of p85 Subunit of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4518–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.286591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Andreozzi F, Laratta E, Sciacqua A, Perticone F, Sesti G. Angiotensin II impairs the insulin signaling pathway promoting production of nitric oxide by inducing phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 on Ser312 and Ser616 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:1211–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126501.34994.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oh SJ, Ha WC, Lee JI, Sohn TS, Kim JH, Lee JM, Chang SA, Hong OK, Son HS. Angiotensin II Inhibits Insulin Binding to Endothelial Cells. Diabetes Metab J. 2011;35:243–7. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2011.35.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]