Abstract

Peroxidizing herbicides inhibit protoporphyrinogen oxidase (Protox), the last enzyme of the common branch of the chlorophyll- and heme-synthesis pathways. There are two isoenzymes of Protox, one of which is located in the plastid and the other in the mitochondria. Sequence analysis of the cloned Protox cDNAs showed that the deduced amino acid sequences of plastidial and mitochondrial Protox in wild-type cells and in herbicide-resistant YZI-1S cells are the same. The level of plastidial Protox mRNA was the same in both wild-type and YZI-1S cells, whereas the level of mitochondrial Protox mRNA YZI-1S cells was up to 10 times the level of wild-type cells. Wild-type cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy to emit strong autofluorescence from chlorophyll. Only a weak fluorescence signal was observed from chlorophyll in YZI-1S cells grown in the Protox inhibitor N-(4-chloro-2-fluoro-5-propagyloxy)-phenyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydrophthalimide. Staining with DiOC6 showed no visible difference in the number or strength of fluorescence between wild-type and YZI-1S mitochondria. Electron micrography of YZI-1S cells showed that, in contrast to wild-type cells, the chloroplasts of YZI-1S cells grown in the presence of N-(4-chloro-2-fluoro-5-propagyloxy)-phenyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydrophthalimide exhibited no grana stacking. These results suggest that the herbicide resistance of YZI-1S cells is due to the overproduction of mitochondrial Protox.

Chlorophyll and heme have in common a cyclic tetrapyrrole structure called a porphyrin. The last common step to chlorophyll and heme in the porphyrin-synthesis pathway is the oxidization of Protogen to Proto IX (Beale and Weinstein, 1990). The existence of an enzyme catalyzing this oxidative step has long been controversial, since Protogen is rapidly oxidized to Proto IX in the presence of air via a light-sensitive, autocatalytic reaction (Klemm and Barton, 1987). Biochemical and genetic evidence now indicate that Protogen oxidation is an enzymatic process carried out by Protox (EC 1.3.3.4) (Beale and Weinstein, 1990). Protox has been observed in both plastids and mitochondria (Jacobs et al., 1991; Matringe et al., 1992b; Lermontova et al., 1997). The plastidial isoenzyme is located in the plastid envelope and thylakoid membranes, and the mitochondrial isoenzyme is found in the inner membrane. From these observations the two isoenzymes are predicted to have different functions that are dependent on their subcompartmental localization (Matringe et al., 1992b; Smith et al., 1993; Lermontova et al., 1997).

It is also known that Protox is the target enzyme of phthalimide compounds such as S23142 and diphenylether compounds such as AF (Sato et al., 1987b; Scalla et al., 1990; Varsano et al., 1990; Camadro et al., 1991; Duke et al., 1991; Matringe et al., 1992a, 1992b). Despite the inhibition of Protox by these compounds in intact plants, the product of the enzyme, Proto IX, accumulates (Sato et al., 1987b; Sandmann and Böger, 1988; Becerril and Duke, 1989; Sherman et al., 1991). The uniqueness and complexity of the mechanism of Protox inhibitors is illustrated in the accumulation of Proto IX. Protogen produced by Protox inhibition leaks out of the plastid and is rapidly oxidized to Proto IX by herbicide-resistant peroxidases that are nonspecific and bound to the plasma membrane (Jacobs and Jacobs, 1993; Lee et al., 1993). The Proto IX produced in the cytoplasm cannot be consumed by the porphyrin-synthetic pathway because Mg-chelatase or Fe-chelatase, which use Proto IX as a substrate, are only located in chloroplasts or mitochondria. Highly reactive singlet oxygen generated by light activation of Proto IX, a photodynamic tetrapyrrole, causes rapid peroxidation of the membrane, resulting in serious cell damage (Becerril and Duke, 1989; Jacobs et al., 1991). Accordingly, phthalimide- and diphenylether-type herbicides are known as Protox-inhibiting herbicides.

We have previously succeeded in the selection of S23142-resistant tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) photomixotrophic cells, YZI-1S, by the stepwise selection of the herbicide (Ichinose et al., 1995). The chlorophyll content (per fresh weight) of YZI-1S cells grown in the presence of S23142 is less than that of wild-type cells grown in its absence, but the growth rates are the same. In bright-light conditions, wild-type cells were bleached about 50% by 2 nm S23142 and YZI-1S cells by a concentration of 250 nm. YZI-1S cells are also resistant to other Protox-inhibiting herbicides (acifluorfenethyl, AF, bifenox, oxadiazon, chlomethoxynil, nitrofen, and chloronitrofen), but are sensitive to atrazine and DCMU, which inhibit photosynthetic electron transport. In addition, YZI-1S cells do not accumulate Proto IX with treatment of S23142 at concentrations up to 100 nm, where wild-type cells accumulate a large amount of Proto IX. The addition of excess δ-aminolevulinic acid, a tetrapyrrole precursor, induces the accumulation of Proto IX and causes bleaching of plants (Rebeiz et al., 1984). YZI-1S and wild-type cells were dose-dependently bleached by δ-aminolevulinic acid in the same manner. The results suggest that the resistance mechanism is not due to a change in Proto IX metabolism. From these data, two different mechanisms of resistance to the Protox-inhibiting herbicides could be expected: overproduction of the target enzyme, Protox, and a change of Protox sensitivity to the herbicides by some mutation of the Protox-encoding gene.

Recently, two different cDNAs of tobacco have been identified by complementation of the heme auxotrophic Escherichia coli hemG mutant lacking Protox activity (Lermontova et al., 1997). One cDNA encodes a protein of 548 amino acid residues, including a putative transit sequence of 50 amino acid residues (PPX-I). The other cDNA encodes a protein of 504 amino acid residues (PPX-II). The deduced amino acid sequences of PPX-I and PPX-II contain only 27.3% conserved residues. The translation product of the first cDNA could be translocated to plastids and a mature protein of approximately 53 kD was detected. The translation product of the second cDNA was targeted to mitochondria without any reduction in size. The data indicate that PPX-I is a plastidial Protox and PPX-II is a mitochondrial Protox (Lermontova et al., 1997).

In this paper we describe the sequences and expression levels of plastidial and mitochondrial Protox in wild-type and YZI-1S cells as well as morphological characteristics of these cells. We also discuss the mechanism of resistance to Protox-inhibiting herbicides in YZI-1S cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

For all experiments photomixotrophic cells of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv Samsun NN) (Sato et al., 1987a) were maintained in a modified Linsmaier-Skoog basal medium (Linsmaier and Skoog, 1965) with twice the original concentration of vitamins, 10−5 m 1-NAA, 10−6 m kinetin (6-furfurylaminopurine), and 3% Suc as previously described (Sato et al., 1987a). The photomixotrophically cultured cells were grown on a reciprocal shaker (model, NR-10, Taitec, Tokyo, Japan) at 120 rpm at 26°C ± 2°C in fluorescent light (approximately 30 W m−2) (Sato et al., 1987a). YZI-1S cells (Ichinose et al., 1995) were cultured as above except that 100 nm S23142 was added to the culture medium.

Preparation and Sequence Analysis of Protox cDNA

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy plant kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) from both wild-type and YZI-1S cells. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using a kit (Ready-To-Go, Pharmacia-Biotech). Two sets of oligonucleotide primers were synthesized for PCR isolation of the plastidial Protox gene. The primers of the first set are from −28 to −8 and from 726 to 703, and the primers of second set are from 614 to 633 and from 1646 to 1620 of the published plastidial Protox gene of tobacco (Lermontova et al., 1997). The sequences of the first primer set are 5′-TGAAGCGCGGTCTACAAGTCA-3′ (CP1-F) and 5′-TGCTGCTTTCATACTCAGTTTTGA-3′ (CP1-R), and the sequences of the second primer set are 5′-TTGAGCAGTTCGTGCGTCGT-3′ (CP2-F) and 5′-TCATTTGTATGCATACCGAGACAGAAAT-3′ (CP2-R). A DNA fragment encoding the mitochondrial Protox was also amplified by PCR using two sets of primers. The primers of the first set correspond to the sequence from −21 to −1 and from 1148 to 1129, and the primers of the second set are from 1048 to 1070 and from 1515 to 1489 of the published mitochondrial Protox gene of tobacco (Lermontova et al., 1997). The sequences of the first primer set are 5′-GGAGATTATCGAAACCAGGAT-3′ (MP1-F) and 5′-GGTGCCCGATCTGGAAACAT-3′ (MP1-R), and the sequences of the second set are 5′-TTGAGGGCTTTGGGGTTCTTGT-3′ (MP2-F) and 5′-TCAGCAATGTCTTTTGGAGTCAGTT-3′ (MP2-R).

After incubating the cDNA at 94°C for 5 min, each Protox gene was amplified with 35 cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 55°C, and a 1-min extension at 72°C. The PCR reactions were terminated with a 10-min incubation at 72°C and stored at 4°C. PCR fragments were cloned using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and five clones from each PCR reaction were sequenced with a DNA sequencer (model 377, Perkin-Elmer-Applied Biosystems). The PCR and cloning procedures were independently repeated twice and the DNA sequences of Protox were carefully confirmed.

RNA Isolation and Gel-Blot Analysis

Cultured cells were ground in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was extracted with aurintricarbosylic acid (Gonzalez et al., 1980). RNA (8 μg) was electrophoresed on a formaldehyde-denaturing 1% agarose gel in 1× Mops buffer (20 mm Mops-KOH, pH 7.0, 5 mm sodium acetate, and 1 mm EDTA) and blotted onto a membrane (Hybond N, Amersham) according to standard protocols. Full-length cDNA fragments of plastidial and mitochondrial Protox gene were labeled with [32P]dCTP and used as hybridization probes.

Fluorescence Microscopy

YZI-1S cells were cultured in the medium containing 100 nm S23142, and wild-type cells were cultured in the same medium without the herbicide. After 2 weeks of culture, wild-type and YZI-1S cells were harvested by filtration and resuspended in a small amount of Linsmaier-Skoog basal medium. Staining with DiOC6 was done in vivo by adding DiOC6 to a final concentration of 2.5 μg mL−1 to the culture medium (Stickens and Verbelen, 1996). Imaging was done using a fluorescence microscope (Leica) with Micro Mover-W (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) fitted with a triple-band filter (no. 81 in the series, Pinkel no. 1 filter set, Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT). Autofluorescence of chloroplasts was observed at an excitation wavelength of 495 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm, and the fluorescence of mitochondria stained with DiOC6 was observed at an excitation wavelength of 570 nm and an emission wavelength of 600 nm. Two images were acquired separately in the IP Lab-PVCAM system through a cooled CCD (charge-coupled device) camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ), and pseudocolored based on the original emission fluorescence. The composite images were printed out with Pictrography (Fuji, Tokyo, Japan).

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Wild-type and YZI-1S cells were cultured in Linsmaier-Skoog basal medium with and without 100 nm S23142, respectively, for 1 week. To observe the recovery of chloroplast structure, YZI-1S cells were also cultured without S23142 for 3 months. Cultured cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.05 m sodium cacodylate, pH 7.0, for 2 h at 4°C, and then washed with 0.05 sodium cacodylate, pH 7.0. The cells were postfixed with 1% OsO4 for 2 h on ice. After washing with water, the cells were dehydrated in a graded acetone series. The dehydrated cells were embedded in Spurr's resin (TAAB Laboratories, Aldermaston, UK) and sectioned. Ultrathin sections were then stained with lead (Reynolds, 1963) and observed under a transmission electron microscope (model H-7100, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 75 kV.

RESULTS

Nucleotide Sequence Determination of Plastidial and Mitochondrial Protox cDNAs

To identify cDNAs encoding plastidial Protox in photomixotrophic cells (wild type) and YZI-1S cells, two sets of oligonucleotide primers (CP1-F and CP1-R and CP2-F and CP2-R) were synthesized based on published sequences for Protox-encoding genes cloned from tobacco (Lermontova et al., 1997). PCR amplification of cDNA from both wild-type and YZI-1S cells produced products of 752 bp (CP1-F and CP1-R) and of 1032 bp (CP2-F and CP2-R). Sequence analysis indicated that the plastidial Protox enzymes of wild-type and YZI-1S cells are composed of 548 amino acids. A comparison of the DNA sequences of plastidial Protox between wild-type and YZI-1S cells indicated that there is no difference between the sequences. For identification of mitochondrial Protox-encoded genes, PCR amplification was also performed using two sets of oligonucleotide primers (MP1-F and MP1-R and MP2-F and MP2-R). Products of 1169 bp (MP1-F and MP1-R) and 467 bp (MP2-F and MP2-R) were obtained from wild-type and YZI-1S cells, respectively. Sequence analysis of wild-type and YZI-1S-amplified cDNA clones indicated that the full-length mitochondrial Protox enzyme is composed of 504 amino acids, and the deduced amino acid sequences of mitochondrial Protox proteins were identical in both cell lines. These results indicate that there is no mutation in either the plastidial or the mitochondrial Protox-encoding gene of YZI-1S cells.

Quantitation of Plastidial and Mitochondrial Protox mRNA

It had been shown previously that Protox activity per total protein of YZI-1S cells was twice that of the wild-type cells (Ichinose et al., 1995). To determine whether increased Protox activity was due to the overproduction of either or both isoforms, we performed northern hybridization analysis using the cloned plastid and mitochondrial Protox cDNA probes, respectively.

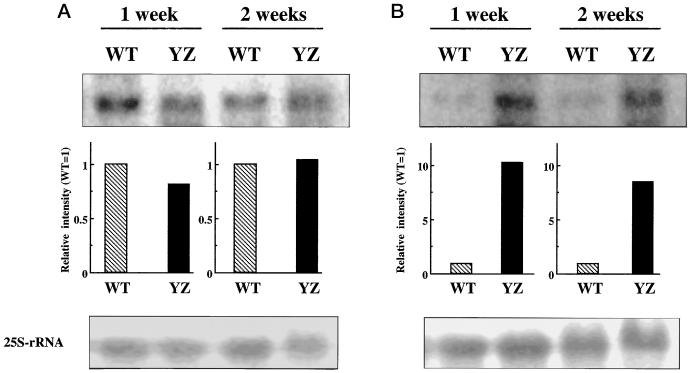

The results of northern analysis using plastidial Protox cDNA as a hybridization probe showed a single band of 1.8 kb, corresponding to the length of the plastidial Protox cDNA. The expression levels of the plastidial Protox mRNA were the same in wild-type and YZI-1S cells after 1 and 2 weeks in culture (Fig. 1A). The amount of mitochondrial Protox mRNA was also examined using the mitochondrial Protox cDNA probe (Fig. 1B). A single band corresponding to the mitochondrial Protox mRNA (1.8 kb) was detected. After 1 week of culture, mitochondrial Protox mRNA of YZI-1S cells was 10 times the level of the wild-type cells. After 2 weeks of culture, the level of mitochondrial Protox mRNA in YZI-1S cells was about 8 times that of the wild-type cells.

Figure 1.

Northern analysis of wild-type (WT) and YZI-1S (YZ) cells probed with plastidial (A) and mitochondrial (B) Protox cDNA. Equivalent amounts of total RNA (8 μg per lane) were fractionated in a 1% agarose-formaldehyde gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and probed with a 32P-labeled probe from each Protox cDNA-coding region. The relative intensity of the bands is indicated in the lower bar graph. The loading of equivalent amounts of RNA was confirmed by hybridization with a 32P-labeled 25S-rRNA clone.

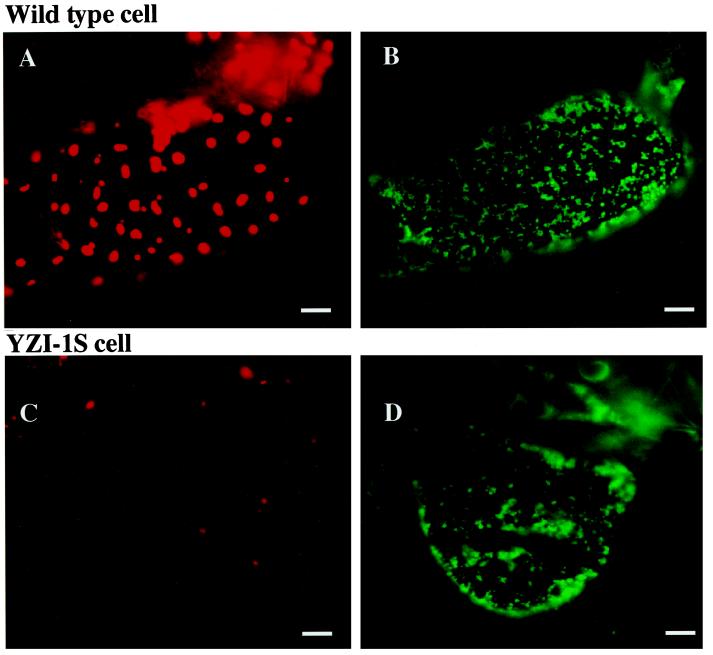

Observation of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria with Fluorescence Microscopy

Wild-type cells cultured in the absence of S23142 and YZI-1S cells cultured in the presence of S23142 were observed by fluorescence microscopy without staining. In wild-type cells chloroplasts were strongly autofluorescent due to chlorophyll (Fig. 2A). In contrast, only a weak signal was observed in YZI-1S cells, suggesting that the chlorophyll content of the YZI-1S cell chloroplasts was lower than in the wild-type cells (Fig. 2C). The chlorophyll contents in YZI-1S cells grown in the presence of S23142 was 0.04 mg chlorophyll g−1 cell fresh weight, less than that of wild-type cells grown in the absence of S23142 (0.15 mg chlorophyll g−1 cell fresh weight). To study the number and distribution of mitochondria in both cell lines, cells were also observed with fluorescence microscopy after staining with DiOC6. In both cell lines the most obvious structures made visible by DiOC6 were nearly spherical mitochondria with a diameter of 1 μm or less. No visible difference could be determined in the number or strength of fluorescence between wild-type and YZI-1S mitochondria (Fig. 2, B and D).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence micrographs of wild-type cells grown in the absence of S23142 and YZI-1S cells grown in the presence of S23142. A, Chloroplasts in fresh wild-type cells; B, mitochondria in fresh wild-type cells stained with DiOC6; C, chloroplasts in fresh YZI-1S cells; and D, mitochondria in fresh YZI-1S cells stained with DiOC6. Bars = 10 μm.

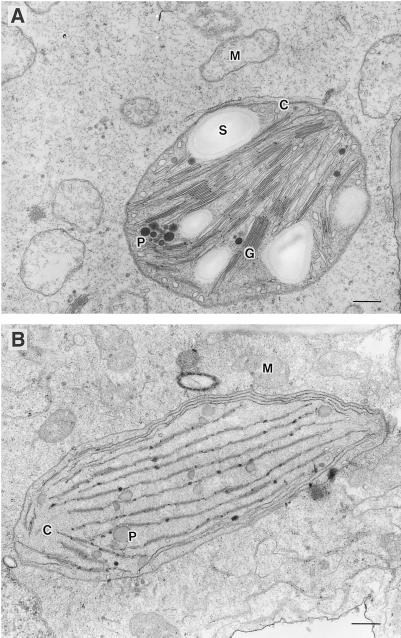

Observation of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria with Transmission Electron Microscopy

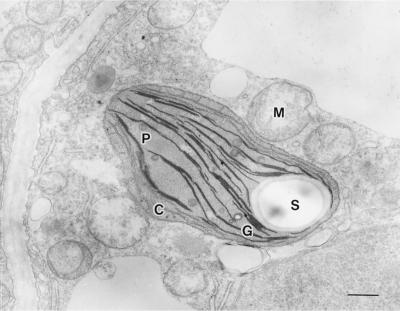

Electron micrographs of wild-type photomixotrophic tobacco cells grown in the absence of S23142 showed that the mature chloroplasts contain granathylakoids containing many discs, fret membranes that interconnect the grana (stromathylakoids), plastoglobuli, and starch grains (Fig. 3A). Mitochondria in these cells are bounded by two envelope membranes, and the inner membrane is folded into cristae, which project into the matrix. Herbicide-resistant YZI-1S cells grown in the presence of S23142 contained chloroplasts that, unlike wild-type cells, had no grana stacking and only very small grana interconnected by stromathylakoids (Fig. 3B). Electron microscopy also showed the absence of starch grains in YZI-1S cells. Conversely, when YZI-1S cells were cultured in the absence of S23142 for 3 months, chlorophyll content in the YZI-1S cells increased to 0.12 mg chlorophyll g−1 fresh weight, the level of wild-type cells. These data suggest that YZI-1S cells are not deficient mutants of the chlorophyll-biosynthesis pathway, rather, that the decrease in chlorophyll content in YZI-1S cells is caused by Protox inhibition of S23142. In addition, electron micrographs of YZI-1S cells grown in the absence of S23142 for 3 months showed that grana stacking was partially recovered and chloroplasts contained starch grains (Fig. 4). These observations indicate that the change in chloroplast structure and the decrease in chlorophyll content in YZI-1S cells do not result in a genetic mutation.

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of wild-type (A) and YZI-1S (B) cells. M, Mitochondrion; C, chloroplast; S, starch grain; P, plastoglobuli; G, grana. Bars = 0.5 μm.

Figure 4.

Transmission electron micrograph of YZI-1S cells grown in the absence of S23142 for 3 months. M, Mitochondrion; C, chloroplast; S, starch grain; P, plastoglobuli; G, grana. Bar = 0.5 μm.

DISCUSSION

Sequences of Plastidial and Mitochondrial Protox-Encoding Genes

Herbicide resistance has been attributed in many cases to structural alterations in the target protein. Atrazine resistance in potato cells resulted from an alteration in the chloroplast D1 protein that prevents atrazine binding (Smeda et al., 1993). Similarly, resistance to sulfonylurea herbicides in Brassica napus has been shown to result from a single amino acid change in acetohydroxy acid synthase, which results in a loss of sensitivity to the herbicide (Hattori et al., 1995). However, the herbicide resistance in YZI-1S cells is apparently not due to structural alterations in two isoenzymes of Protox, because there was no difference in the deduced amino acid sequences of the wild-type and YZI-1S cells. The nucleotide sequence of the published plastidial Protox gene of tobacco (Lermontova et al., 1997) contains an adenine at position 1144 rather than the thymidine seen in our cell lines. This exchange resulted in a Thr-382-to-Ser substitution in the derived amino acid sequence.

Overproduction of Mitochondrial Protox in the Resistant Cell Line

In our experiment the mitochondrial Protox mRNA levels of YZI-1S cells increased to about 10 times the level of wild-type cells. In contrast, the level of plastidial Protox mRNA was the same in wild-type and YZI-1S cells after 1 and 2 weeks of culture. We previously reported that YZI-1S cells had almost twice the Protox activity (57 nmol mg−1 h−1 on a total-protein basis) of wild-type cells (29 nmol mg−1 h−1) (Ichinose et al., 1995). It is likely that the increased mitochondrial Protox activity was due to increased gene expression or gene duplication, as reflected by the increased mRNA levels in YZI-1S cells.

It is well known that herbicide resistance in plant cells can be due to the overproduction of the target enzyme. Glyphosate inhibits the conversion of shikimate 3-phosphate to EPSP, which is catalyzed by EPSP synthase (Reinbothe et al., 1991). The mRNA levels of EPSP synthase in two lines of resistant carrot cells, CAR and CI, subjected to stepwise selection were 59 and 32 times the level of their respective wild-type cells (Shyr et al., 1992). Moreover, the resistant suspension-cultured cells of Corydalis sempervirens (Holländer-Czytko et al., 1992) and petunia (Shah et al., 1986) contained several-times higher levels of EPSP synthase mRNA than wild-type cells. These studies clearly demonstrated that the increase in EPSP synthase mRNA resulted in resistance to glyphosate. The increase of the mitochondrial Protox mRNA level in YZI-1S cells may result in resistance to Protox-inhibiting herbicides. However, it remains to be determined whether the accumulation of mitochondrial Protox mRNA is due to an increase in transcript stability, to gene amplification, or to an enhanced rate of transcription.

Protox-inhibiting herbicides such as S23142 and AFE inhibit Protox activity in both chloroplasts and mitochondria in vitro (Matringe et al., 1989a, 1989b); however, a considerable body of evidence indicates that plastidial Protox is the primary herbicide target (Camadro et al., 1991; Retzlaff and Böger, 1996). We observed overproduction of Protox mRNA not in chloroplasts but in mitochondria of YZI-1S cells. In addition, YZI-1S cells did not accumulate Proto IX even at a concentration of 100 nm S23142 (Ichinose et al., 1995). These results suggest that Proto IX does not accumulate in YZI-1S cells because of overproduction of mitochondrial Protox, which leads to resistance to Protox-inhibiting herbicides in photomixotrophic cultures.

Structural Changes of Mitochondria and Chloroplasts

The amount of chlorophyll in YZI-1S cells grown in a medium containing S23142 clearly decreased (Fig. 2), suggesting that plastid Protox in YZI-1S cells is sensitive to S23142 and, because of an alteration in the structure of the plastid Protox enzyme, the mechanism of resistance to S23142 in YZI-1S cells is not. The decrease in chlorophyll content and the lack of photosynthesis function in YZI-1S cells do not cause resistance to the herbicide, because tentoxin-treated yellow cucumber cotyledons, which contain very little chlorophyll, are highly sensitive to AF and accumulate high concentrations of Proto IX (Lehnen et al., 1990). YZI-1S cells grown in the presence of S23142 had no visible change in mitochondria stained with DiOC6. There was no apparent difference in the ultrastructure of mitochondria between the two cell types (Fig. 2). These observations suggest that the structure and function of mitochondria in YZI-1S cells is unaffected by S23142.

The lack of grana stacking in YZI-1S cells is a characteristic of etioplasts (Gunning and Steer, 1996). When dark-grown plants are illuminated, etioplasts develop into chloroplasts through a process that includes chlorophyll synthesis, grana thylakoid development, and the expression of genes required for photosynthesis and other important chloroplast functions. Many nuclear genes encode plastid proteins and are regulated by exposure to light (Kusnetsov et al., 1996). Transcriptional coordination between chloroplasts and the nucleus requires an exchange of signals (the plastidic signal) (Taylor, 1989). Recently, Kropat et al. (1997) reported that Mg-Proto IX, a chlorophyll precursor, can replace light in the induction of a nuclear gene encoding a plastid-localized heat-shock protein (HSP70B), and that Mg-Proto IX acts as a signal between chloroplasts and the nucleus.

The decrease in the chlorophyll content of YZI-1S cells suggests that Protox in YZI-1S cells was inhibited by S23142, and the chlorophyll pathway intermediates following Proto IX are at very low concentrations in YZI-1S cells. The low levels of chlorophyll precursors, including Mg-Proto IX, may be insufficient to stimulate expression of light-dependent genes in the nucleus. As a result, proteins that are required for the normal development of chloroplasts would not be supplied even under irradiation, resulting in etiolation of YZI-1S cells. This idea is also supported by the observation using transmission electron microscopy that grana stacking is partially recovered in YZI-1S cells grown in the absence of S23142. The inhibition of plastidial Protox by the herbicides, and the resulting loss of development of chloroplasts in YZI-1S cells, may be an important tool in characterizing nuclear and plastidial interorganellar gene-regulation signals.

Proposed Mechanism of Resistance in YZI-1S Cells

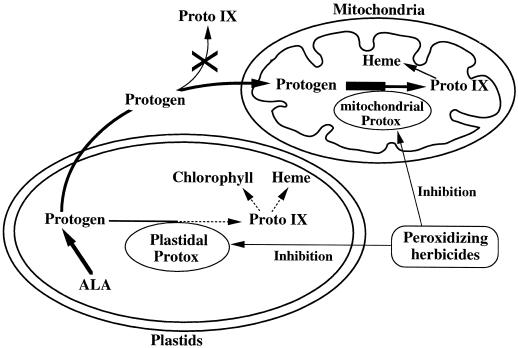

The chloroplast contains all of the enzymes necessary for synthesis of chlorophyll and heme from glutamate, the earliest precursor of porphyrin. However, plant mitochondria contain enzymes for only the last two steps in heme synthesis, Protox (Jacobs et al., 1982) and ferrochelatase (Jones, 1968; Porra and Lascellses, 1968; Little and Jones, 1976), and depend on plastids for the precursors of heme biosynthesis. Protogen is exported from plastids to mitochondria and there becomes the substrate for mitochondrial Protox. When wild-type cells are treated with S23142, plastidial Protox is inhibited and Protogen becomes excessive. In wild-type cells, Protogen cannot be metabolized either in plastids or mitochondria, since Protox is generally inhibited by the herbicide. Protogen is rapidly oxidized to Proto IX by herbicide-insensitive peroxidase, causing damage by the highly reactive singlet oxygen generated by light activation of Proto IX (Retzlaff and Böger, 1996). When YZI-1S cells are treated with S23142, plastidial Protox is also inhibited and Protogen becomes excessive. However, in YZI-1S cells the excessive Protogen is metabolized in mitochondria even in the presence of the herbicide because of high levels of mitochondrial Protox. As a result, Proto IX is not accumulated and toxic singlet oxygen is not formed in YZI-1S cells (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Hypothetical mechanism of Protox-inhibiting herbicide resistance in YZI-1S cells. Protogen caused by plastidial Protox inhibition of Protox-inhibiting herbicide leaks out of chloroplasts. In YZI-1S cells excessive Protogen is metabolized in mitochondria even in the presence of herbicide because of high levels of mitochondrial Protox. Proto IX is not formed, so no toxic singlet oxygen is formed.

The growth of photomixotrophic tobacco cells depends on both photosynthesis and catabolism of sugars in the culture medium. YZI-1S cells have been able to acquire herbicide resistance by the overexpression of mitochondrial Protox because the loss of photosynthesis is not fatal to photomixotrophic cells. For the practical breeding of plants resistant to Protox-inhibiting herbicides, it would be necessary to overproduce both mitochondrial and plastidial Protox to allow photosynthesis to occur. It would also be interesting to discover whether stepwise selection for S23142 resistance affects only mitochondrial Protox levels, or if plastidial Protox transcription levels are affected as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our thanks to Sumitomo Chemical Co. Ltd. for providing us with S23142. The authors are grateful to Miss Tokiko Miura and Mr. Katsunori Ichinose for excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations:

- AF

acifluorfen (5-[2-chloro-4-{trifuluoromethyl} phenoxy]-2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- DiOC6

3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide

- EPSP

5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate

- Proto IX

protoporphyrin IX

- Protogen

protoporphyrinogen IX

- Protox

protoporphyrinogen oxidase

- S23142

N-(4-chloro-2-fluoro-5-propagyloxy)-phenyl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydrophthalimide

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (no. 09760304).

LITERATURE CITED

- Beale SI, Weinstein JD. Tetrapyrrole metabolism in photosynthetic organisms. In: Dailey HA, editor. Biosynthesis of Hemes and Chlorophylls. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1990. pp. 287–391. [Google Scholar]

- Becerril JM, Duke SO. Protoporphyrin IX content correlates with activity of photobleaching herbicides. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:1175–1181. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.3.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camadro J, Matringe M, Scalla R, Labbe P. Kinetic studies on protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition by diphenyl ether herbicides. Biochem J. 1991;277:17–21. doi: 10.1042/bj2770017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke SO, Becerril JM, Sherman TD, Lehnen LP, Matsumoto H. Protoporphyrinogen oxidase-inhibiting herbicides. Weed Sci. 1991;39:465–473. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.1.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez RG, Haxo RS, Schleich T. Mechanism of action of polymeric aurintricarboxylic acid, a potent inhibitor of protein-nucleic acid interaction. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4299–4303. doi: 10.1021/bi00559a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning BES, Steer MW (1996) The greening process: from etioplast to chloroplast. In BES Gunning, MW Steer, eds, Plant Cells Biology. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, MA, pp 20–29

- Hattori J, Brown D, Mourad G, Labbe H, Ouellet T, Sunohara G, Rutledge R, King J, Miki B. An acetohydroxy acid synthase mutant reveals a single site involved in multiple herbicide resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;246:419–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00290445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holländer-Czytko H, Sommer I, Amrhein N. Glyphosate tolerance of cultured Corydalis sempervirens cells is acquired by an increased rate of transcription of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase as well as by a reduced turnover of the enzyme. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:1029–1036. doi: 10.1007/BF00028890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose K, Che FS, Kimura Y, Matsunobu A, Sato F, Yoshida S. Selection and characterization of protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibiting herbicide (S23142) resistant photomixotrophic cultured cells of Nicotiana tabacum. J Plant Physiol. 1995;146:693–698. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JM, Jacobs NJ. Porphyrin accumulation and export by isolated barley (Hordeum vulgare) plastid. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:1181–1187. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.4.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JM, Jacobs NJ, DeMaggio AE. Protoporphyrinogen oxidation in chloroplasts and plant mitochondria, step in heme and chlorophyll synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;218:233–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JM, Jacobs NJ, Sherman TD, Duke SO. Effect of diphenyl ether herbicides on oxidation of protoporphyrinogen to protoporphyrin in organella and plasma membrane enriched fractions of barley. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:197–203. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones OTG. Ferrochelatase of spinach chloroplasts. Biochem J. 1968;107:113–119. doi: 10.1042/bj1070113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm DJ, Barton LL. Purification and properties of Protoporphyrinogen oxidase from an anaerobic bacterium, Desulfovibrio gigas. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5209–5215. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5209-5215.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropat J, Oster U, Rüdiger W, Beck CF. Chlorophyll precursors are signals of chloroplast origin involved in light induction of nuclear heat-shock genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14168–14172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusnetsov V, Bolle C, Lübberstedt T, Sopory S, Herrmann RG, Oelmüller R. Evidence that the plastid signal and light operate via the same cis-acting elements in the promoters of nuclear genes for plastid proteins. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:631–639. doi: 10.1007/BF02173968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Duke MV, Duke SO. Cellular localization of protoporphyrinogen-oxidizing activities of etiolated barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) leaves. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:881–889. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnen LP, Sherman TD, Becerril JM, Duke SO. Tissue and cellular localization of acifluorfen-induced porphyrins in cucumber cotyledons. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1990;37:239–248. [Google Scholar]

- Lermontova I, Kruse E, Mock HP, Grimm B. Cloning and characterization of a plastidal and a mitochondrial isoform of tobacco protoporphyrinogen IX oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8895–8900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsmaier EM, Skoog F. Organic growth factor requirements of tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1965;18:100–127. [Google Scholar]

- Little HN, Jones OTG. The subcellular localization and properties of the ferrochelatase of etiolated barley. Biochem J. 1976;156:309–314. doi: 10.1042/bj1560309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matringe M, Camadro JM, Block MA, Joyard J, Scalla R, Labbe P, Douce R. Localization within chloroplasts of protoporphyrinogen oxidase, the target enzyme for diphenylether-like herbicides. J Biol Chem. 1992b;267:4646–4651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matringe M, Camadro JM, Labbe P, Scalla R. Protoporphyrinogen oxidase as a molecular target for diphenyl ether herbicides. Biochem J. 1989a;260:231–235. doi: 10.1042/bj2600231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matringe M, Camadro JM, Labbe P, Scalla R, (1989b) Protoporphyrinogen oxidase inhibition by three peroxidizing herbicides: oxadiazon, LS82–556 and M & B 39279. FEBS Lett 245: 35–38 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matringe M, Mornet R, Scalla R. Characterization of [3H]acifluorfen binding to purified pea etioplasts, and evidence that protoporphyrinogen oxidase specifically binds acifluorfen. Eur J Biochem. 1992a;209:861–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra RJ, Lascellses J. Studies on ferrochelatase: the enzymic formation of heme in protoplastids, chloroplasts, and plant mitochondria. Biochem J. 1968;108:343–348. doi: 10.1042/bj1080343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiz CA, Montazer-Zouhoor A, Hopen HJ, Wu SM. Photodynamic herbicides: concept and phenomenology. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1984;6:390–402. [Google Scholar]

- Reinbothe S, Nelles A, Parthier B. N-(phosphonomethyl) glycine (glyphosate) tolerance in Euglena gracilis acquired by either overproduced or resistant 5-enol pyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase. Eur J Biochem. 1991;198:365–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retzlaff K, Böger P. An endoplasmic reticulum plant enzyme has protoporphyrinogen IX oxidase activity. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1996;54:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds ES. The use of lead citrate at high pH as an electron-opaque stain in electron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1963;38:1–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann G, Böger P. Accumulation of protoporphyrin IX in the presence of peroxidizing herbicides. Z Naturforsch. 1988;43c:699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Sato F, Takeda S, Yamada Y. A comparison of effects of several herbicides on photoautotrophic, photomixotrophic and heterotrophic cultured tobacco cells and seedlings. Plant Cell Rep. 1987a;6:401–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00272768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato R, Nagano E, Oshio H, Kamoshita K. Diphenylether-like physiological and biochemical action of S23142, a novel N-phenyl imide herbicide. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1987b;28:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Scalla R, Matringe M, Camadro JM, Labbe P. Recent advances in the mode of action of diphenyl ether and related herbicides. Z Naturforsch. 1990;45c:503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Shah DM, Horsch RB, Klee HJ, Kishore GM, Winter JA, Turner NE, Hironaka CM, Sanders PR, Gasser CS, Aykent SA and others. Engineering herbicide tolerance in transgenic plants. Science. 1986;233:478–481. doi: 10.1126/science.233.4762.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman TD, Duke MV, Clark RD, Sanders EF, Matsumoto H, Duke SO. Pyrazole phenyl ether herbicides inhibit protoporphyrinogen oxidase. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1991;40:236–245. [Google Scholar]

- Shyr YYJ, Hepburn AG, Widholm JM. Glyphosate selected amplification of the 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase gene in cultured carrot cells. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;232:377–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00266240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeda RJ, Hasegawa PM, Goldsbrough PB, Singh NK, Weller SC. A serin-to-threonine substitution in the triazine herbicide-binding protein in potato cells results in atrazine resistance without impairing productivity. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:911–917. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.3.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AG, Marsh O, Elder GH. Investigation of the subcellular location of the tetrapyrrole-biosynthesis enzyme coproporphyrinogen oxidase in higher plants. Biochem J. 1993;292:503–508. doi: 10.1042/bj2920503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stickens D, Verbelen JP. Spatial structure of mitochondria and ER denotes changes in cell physiology of cultured tobacco protoplasts. Plant J. 1996;9:85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WC. Regulatory interactions between nuclear and plastid genomes. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1989;40:211–233. [Google Scholar]

- Varsano R, Matringe M, Magnin N, Mornet R, Scalla R. Competitive interaction of three peroxidizing herbicides with the binding of [3H]acifluorfen to corn etioplast membranes. FEBS Lett. 1990;272:106–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80459-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]