Abstract

Urban land-cover change threatens biodiversity and affects ecosystem productivity through loss of habitat, biomass, and carbon storage. However, despite projections that world urban populations will increase to nearly 5 billion by 2030, little is known about future locations, magnitudes, and rates of urban expansion. Here we develop spatially explicit probabilistic forecasts of global urban land-cover change and explore the direct impacts on biodiversity hotspots and tropical carbon biomass. If current trends in population density continue and all areas with high probabilities of urban expansion undergo change, then by 2030, urban land cover will increase by 1.2 million km2, nearly tripling the global urban land area circa 2000. This increase would result in considerable loss of habitats in key biodiversity hotspots, with the highest rates of forecasted urban growth to take place in regions that were relatively undisturbed by urban development in 2000: the Eastern Afromontane, the Guinean Forests of West Africa, and the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka hotspots. Within the pan-tropics, loss in vegetation biomass from areas with high probability of urban expansion is estimated to be 1.38 PgC (0.05 PgC yr−1), equal to ∼5% of emissions from tropical deforestation and land-use change. Although urbanization is often considered a local issue, the aggregate global impacts of projected urban expansion will require significant policy changes to affect future growth trajectories to minimize global biodiversity and vegetation carbon losses.

Keywords: sustainability, land change science

For centuries, cities were compact with high population densities, and the physical extent of cities grew slowly (1). This trend has been reversed over the last 30 y. Today, urban areas around the world are expanding on average twice as fast than their populations (2, 3). Although urban land cover is a relatively small fraction of the total Earth surface, urban areas drive global environmental change (4). Urban expansion and associated land-cover change drives habitat loss (5, 6), threatens biodiversity (7), and results in the loss of terrestrial carbon stored in vegetation biomass (8). Land-cover change could lead to the loss of up to 40% of the species in some of the most biologically diverse areas around the world (9), and as of 2000, 88% of the global primary vegetation land cover had been destroyed in “biodiversity hotspots” (10). The results of many local-scale studies highlight the need to understand the aggregate impact of urban expansion and land-cover change on biodiversity at the global scale.

The most recent United Nations projections show an increase in urban population of 1.35 billion by 2030 (11). How will the expected increase in urban populations to nearly 5 billion by 2030, combined with positive outlooks for future global economic growth, manifest in urban land-cover change and in turn affect biodiversity and carbon pools? Here we present spatially explicit probabilistic forecasts of global urban expansion and explore the direct impacts on biodiversity and terrestrial carbon storage. We use global land cover circa 2000 (12) and projections of urban population (13, 14) and gross domestic product (GDP) growth (15) in a probabilistic model of urban land change to develop 1,000 projections of urban expansion through to 2030. We then use independent sources on biodiversity hotspots, threatened species, and carbon pools to examine the likely consequences of forecasted urban growth on the direct loss of habitat and biomass carbon.

Global Urban Expansion to 2030

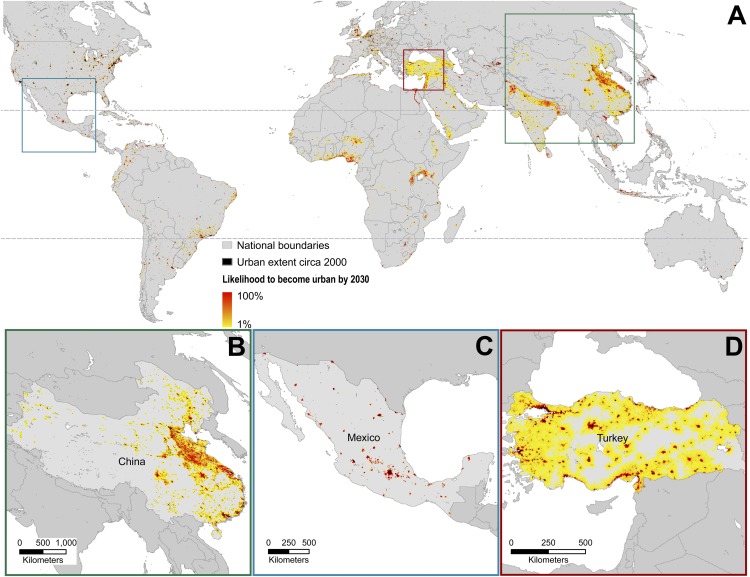

Although urban population growth is a global phenomenon, our results show that the bulk of urban expansion and associated land-cover change will be concentrated in a few regions (Fig. 1A). Globally, more than 5.87 million km2 of land have a positive probability (>0%) of being converted to urban areas by 2030, and 20% of this (1.2 million km2) have high probabilities (>75%) of urban expansion (Table 1). If all areas with high probability (>75%) undergo urban land conversion, there will be a 185% increase in the global urban extent from circa 2000.

Fig. 1.

Global forecasts of probabilities of urban expansion, 2030. There is significant variation in the amount and likelihood of urban expansion (A). Much of the forecasted urban expansion is likely to occur in eastern China (B). Some regions have high probability of urban expansion is specific locations (C) and others have large areas of low probability urban growth (D). Dashed lines denote northern and southern boundaries of the tropics.

Table 1.

Forecasts of urban expansion by probability quartile range, 2030

| Regions defined in the model* | New urban land area with probability greater than zero (km2) by probability quartile range (regional percentage) |

2000 urban extent (km2) (regional percentage) | |||

| >0–25 | >25–50 | >50–75 | >75–100 | ||

| Central America | 22,600 (0.8) | 6,100 (0.2) | 6,125 (0.2) | 41,025 (1.5) | 13,500 (0.5) |

| China | 1,349,650 (14.6) | 38,600 (0.4) | 27,175 (0.3) | 219,700 (2.4) | 80,525 (0.9) |

| Eastern Asia | 10,825 (1.7) | 5,675 (0.9) | 5,800 (0.9) | 29,800 (4.7) | 28,075 (4.5) |

| Eastern Europe | 12,850 (0.1) | 3,750 (0.0) | 32,400 (0.2) | 3,975 (0.0) | 70,275 (0.3) |

| India | 546,000 (16.7) | 18,600 (0.6) | 8,600 (0.3) | 107,275 (3.3) | 30,400 (0.9) |

| Mid-Asia | 5,950 (0.2) | 2,025 (0.1) | 2,175 (0.1) | 24,225 (0.9) | 16,500 (0.6) |

| Mid-Latitudinal Africa | 531,125 (2.8) | 33,025 (0.2) | 23,875 (0.1) | 180,125 (1.0) | 19,675 (0.1) |

| Northern Africa | 30,000 (0.4) | 6,450 (0.1) | 5,350 (0.1) | 46,875 (0.6) | 13,350 (0.2) |

| Northern America | 175,775 (0.9) | 21,075 (0.1) | 5,875 (0.0) | 118,175 (0.6) | 130,500 (0.7) |

| Oceania | 5,300 (0.1) | 1,675 (0.0) | 4,725 (0.1) | 9,700 (0.1) | 10,450 (0.1) |

| South America | 264,175 (1.5) | 33,600 (0.2) | 16,150 (0.1) | 134,050 (0.8) | 80,025 (0.5) |

| Southern Africa | 10,950 (0.4) | 2,575 (0.1) | 2,400 (0.1) | 17,475 (0.7) | 8,425 (0.3) |

| Southern Asia | 70,900 (2.1) | 10,725 (0.3) | 17,175 (0.5) | 72,400 (2.1) | 16,250 (0.5) |

| Southeastern Asia | 58,400 (1.3) | 7,775 (0.2) | 8,275 (0.2) | 69,450 (1.5) | 27,275 (0.6) |

| Western Asia | 966,875 (21.4) | 45,575 (1.0) | 38,200 (0.8) | 62,625 (1.4) | 26,800 (0.6) |

| Western Europe | 141,400 (3.8) | 13,075 (0.3) | 4,525 (0.1) | 73,600 (2.0) | 80,800 (2.2) |

| World | 4,202,775 (3.2) | 250,300 (0.2) | 208,825 (0.2) | 1,210,475 (0.9) | 652,825 (0.5) |

*We define 16 regions for the model broadly based on the United Nations world regions. We deviate from the United Nations regions when one country is economically dissimilar (as measured by per capita GDP) to other countries in its assigned region and economically more similar to a neighboring region. The composition of each region defined in the model is described in Table S1.

Nearly half of the increase in high-probability urban expansion globally is forecasted to occur in Asia, with China and India absorbing 55% of the regional total. In China, urban expansion is forecasted to create a 1,800-km coastal urban corridor from Hangzhou to Shenyang (Fig. 1B). In India, urban expansion is forecasted to be clustered around seven state capital cities, with large areas of low-probability growth forecasted in the Himalayan region, where many small villages and towns currently exist. The rate of increase in urban land cover is predicted to be highest in Africa, at 590% over the 2000 levels (Table 1). Here, expansion will be concentrated in five regions: the Nile River in Egypt, the coast of West Africa on the Gulf of Guinea, the northern shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya and Uganda and extending into Rwanda and Burundi, the Kano region in northern Nigeria, and greater Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. In North America, where the percentage of total population living in urban areas is already high (78%), the forecasts show a near doubling of urban land cover by 2030. The forecasts also indicate that 48 of the 221 countries in the study will experience negligible amounts of urban expansion.

In many countries, there is an inverse relationship between the probability that specific geographic locations will experience urban expansion and magnitude of predicted urban expansion (Table 1 and Fig. S1). For example, total forecasted area of urban expansion in Mexico is small, but the probability that specific locations in Mexico will undergo urban expansion is high (Fig. 1C). In contrast, Turkey has low probabilities of urban expansion in many parts of the country, and the predicted magnitude of total urban expansion is also relatively low (Fig. 1D). In the remaining presentation of the results, unless otherwise noted, our discussion will be limited to only the areas with high probability of urban expansion.

Direct Impacts of Urban Expansion on Habitat and Biodiversity

We use an independent dataset of 34 established biodiversity hotspots (10, 16) and examine the spatial overlap between their locations and our forecasts of urban expansion.

Less than 1% of all hotspot areas were urbanized circa 2000. By 2030, new urban expansion will take up an additional 1.8% of all hotspot areas (Table 2). Five biodiversity hotspots are forecasted to have the largest percentages of their areas to become urban: the Guinean forests of West Africa (7%), Japan (6%), the Caribbean Islands (4%), the Philippines (4%), and the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka (4%). The hotspots with the largest percentages of their areas that will be threatened by low probabilities of expansion are in the Caucasus (24%), the Irano-Anatolian (20%), the Guinean forests of West Africa (16%), and the Mediterranean Basin (14%). In contrast, the East Melanesian Islands in Oceania, the Mountains of Southwest China, and the Succulent Karoo in Southern Africa are forecasted to be largely unaffected directly by urban expansion. The Mediterranean Basin and the Atlantic Forest hotspots had the most urban area circa 2000 and are expected to experience about a 160% increase in their urban extent from 2000 to 2030. However, the highest rates of growth in urban area are forecasted to take place in regions that were relatively undisturbed by urban development circa 2000: the Eastern Afromontane, the Guinean Forests of West Africa, and the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka hotspots. Urban areas in these three hotspots are forecasted to increase by ∼1,900%, 920%, and 900% over their 2000 levels, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Biodiversity hotspots threatened by forecasted urban expansion, 2030

| Biodiversity hotspot (10, 16) | Hotspot area not threatened by urban expansion (km2) (percentage of hotspot) | Urban expansion in hotspot (km2) by probability quartile range (percentage of hotspot)* |

Urban extent in hotspots ca. 2000 (km2) (percentage of hotspot) | |||

| >0–25 | >25–50 | >50–75 | >75–100 | |||

| Atlantic Forest | 1,060,700 (85.0) | 103,775 (8.3) | 11,350 (0.9) | 5,850 (0.5) | 40,975 (3.3) | 25,100 (2.0) |

| California Floristic Province | 261,625 (88.2) | 8,700 (2.9) | 1,500 (0.5) | 350 (0.1) | 9,675 (3.3) | 14,750 (5.0) |

| Cape Floristic Region | 80,400 (97.4) | 175 (0.2) | 25 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1,100 (1.3) | 875 (1.1) |

| Caribbean Islands | 201,525 (88.1) | 9,700 (4.2) | 2,900 (1.3) | 1,825 (0.8) | 8,825 (3.9) | 3,900 (1.7) |

| Caucasus | 374,825 (70.4) | 126,700 (23.8) | 8,800 (1.7) | 6,400 (1.2) | 6,325 (1.2) | 9,425 (1.8) |

| Cerrado | 2,011,875 (97.4) | 30,025 (1.5) | 2,975 (0.1) | 1,250 (0.1) | 10,750 (0.5) | 8,400 (0.4) |

| Chilean Winter Rainfall and Valdivian Forests | 381,200 (95.3) | 8,200 (2.0) | 1,075 (0.3) | 575 (0.1) | 5,200 (1.3) | 3,850 (1.0) |

| Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa | 287,575 (94.6) | 9,775 (3.2) | 275 (0.1) | 300 (0.1) | 5,350 (1.8) | 800 (0.3) |

| East Melanesian Islands | 102,650 (99.8) | 100 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 125 (0.1) |

| Eastern Afromontane | 902,950 (86.2) | 99,775 (9.5) | 8,400 (0.8) | 6,500 (0.6) | 28,400 (2.7) | 1,500 (0.1) |

| Guinean Forests of West Africa | 482,775 (75.1) | 101,950 (15.9) | 5,800 (0.9) | 3,775 (0.6) | 43,675 (6.8) | 4,725 (0.7) |

| Himalaya | 729,425 (95.6) | 21,375 (2.8) | 1,225 (0.2) | 1,425 (0.2) | 8,600 (1.1) | 1,225 (0.2) |

| Horn of Africa | 1,597,450 (95.7) | 57,275 (3.4) | 2,650 (0.2) | 4,650 (0.3) | 5,300 (0.3) | 1,575 (0.1) |

| Indo-Burma | 2,164,150 (91.1) | 130,650 (5.5) | 4,775 (0.2) | 5,400 (0.2) | 50,950 (2.1) | 19,650 (0.8) |

| Irano-Anatolian | 705,050 (77.7) | 178,300 (19.7) | 2,850 (0.3) | 3,025 (0.3) | 12,075 (1.3) | 6,075 (0.7) |

| Japan | 318,150 (85.5) | 6,000 (1.6) | 4,250 (1.1) | 3,700 (1.0) | 20,850 (5.6) | 19,250 (5.2) |

| Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands | 590,525 (98.5) | 6,050 (1.0) | 350 (0.1) | 75 (0.0) | 2,100 (0.4) | 275 (0.0) |

| Madrean Pine-Oak Woodlands | 510,275 (98.1) | 1,725 (0.3) | 400 (0.1) | 550 (0.1) | 5,850 (1.1) | 1,100 (0.2) |

| Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany | 260,125 (93.7) | 6,300 (2.3) | 1,375 (0.5) | 1,475 (0.5) | 7,225 (2.6) | 1,075 (0.4) |

| Mediterranean Basin | 1,687,550 (79.6) | 302,825 (14.3) | 23,750 (1.1) | 16,650 (0.8) | 54,675 (2.6) | 33,450 (1.6) |

| Mesoamerica | 1,078,325 (96.9) | 8,200 (0.7) | 2,050 (0.2) | 2,575 (0.2) | 17,175 (1.5) | 4,425 (0.4) |

| Mountains of Central Asia | 816,700 (94.0) | 18,200 (2.1) | 1,275 (0.1) | 1,725 (0.2) | 17,925 (2.1) | 12,750 (1.5) |

| Mountains of Southwest China | 280,650 (97.7) | 6,375 (2.2) | 25 (0.0) | 75 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 275 (0.1) |

| New Caledonia | 18,975 (98.8) | 75 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (0.3) | 50 (0.3) | 50 (0.3) |

| New Zealand | 259,250 (98.1) | 1,625 (0.6) | 500 (0.2) | 950 (0.4) | 750 (0.3) | 1,075 (0.4) |

| Philippines | 276,625 (92.7) | 6,275 (2.1) | 975 (0.3) | 650 (0.2) | 10,825 (3.6) | 2,900 (1.0) |

| Polynesia-Micronesia | 37,300 (96.6) | 175 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 725 (1.9) | 400 (1.0) |

| Southwest Australia | 357,500 (99.3) | 250 (0.1) | 150 (0.0) | 550 (0.2) | 550 (0.2) | 1,100 (0.3) |

| Succulent Karoo | 105,050 (99.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (0.0) | 50 (0.0) |

| Sundaland | 1,447,600 (96.4) | 11,700 (0.8) | 2,750 (0.2) | 2,825 (0.2) | 23,475 (1.6) | 12,825 (0.9) |

| Tropical Andes | 1,515,250 (95.4) | 35,825 (2.3) | 5,025 (0.3) | 2,000 (0.1) | 23,250 (1.5) | 7,450 (0.5) |

| Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena | 247,850 (90.8) | 15,450 (5.7) | 2,050 (0.8) | 900 (0.3) | 5,375 (2.0) | 1,375 (0.5) |

| Wallacea | 340,050 (99.2) | 450 (0.1) | 150 (0.0) | 375 (0.1) | 650 (0.2) | 1,275 (0.4) |

| Western Ghats and Sri Lanka | 174,700 (89.1) | 11,250 (5.7) | 1,075 (0.5) | 750 (0.4) | 7,500 (3.8) | 825 (0.4) |

| All hotspots | 21,666,625 (91.0) | 1,325,225 (5.6) | 100,750 (0.4) | 77,200 (0.3) | 436,175 (1.8) | 203,900 (0.9) |

*Percentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

We also examine the spatial overlap between the urban expansion forecasts with Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE) sites across the world (17, 18). More than a quarter of species in amphibian, mammalian, and reptilian classes each will be affected in varying degrees from urban expansion in AZE sites (Table 3). Habitats are expected to be encroached upon or destroyed by urban expansion for 139 amphibian species, 41 mammalians species, and 25 bird species that are on either the Critically Endangered or Endangered Lists of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Africa and Europe are expected to have the highest percentages of AZE species to be affected by urban expansion, 30% and 33%, respectively (Table 3). However, the Americas will have the largest number of species affected by urban expansion, 134, representing one-quarter of all AZE species in the region.

Table 3.

Critically endangered and endangered species in AZE sites to be affected by urban expansion across classes and regions

| No. of species in AZE sites to be urban by 2030* |

|||||

| Class or region | IUCN red list category | Total no. of species across all AZE sites | In part | Mostly | Completely |

| Class | |||||

| Amphibia | EN+CR | 507 | 139 (27) | 26 (5) | 15 (3) |

| EN | 208 | 54 (26) | 8 (4) | 5 (2) | |

| CR | 299 | 85 (28) | 18 (6) | 10 (3) | |

| Aves | EN+CR | 199 | 25 (13) | 5 (3) | 2 (1) |

| EN | 94 | 11 (12) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| CR | 105 | 14 (13) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Coniferopsida | EN+CR | 26 | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| EN | 13 | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| CR | 13 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Mammalia | EN+CR | 165 | 41 (25) | 9 (5) | 3 (2) |

| EN | 68 | 22 (32) | 4 (6) | 1 (1) | |

| CR | 97 | 19 (20) | 5 (5) | 2 (2) | |

| Reptilia | EN+CR | 17 | 6 (35) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) |

| EN | 4 | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | |

| CR | 13 | 5 (38) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | EN+CR | 914 | 214 (23) | 41 (4) | 20 (2) |

| EN | 387 | 91 (24) | 16 (4) | 6 (2) | |

| CR | 527 | 123 (23) | 25 (5) | 14 (3) | |

| Region | |||||

| Africa | EN+CR | 140 | 42 (30) | 7 (5) | 1 (1) |

| EN | 83 | 29 (35) | 5 (6) | 1 (1) | |

| CR | 57 | 13 (23) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Asia | EN+CR | 140 | 34 (24) | 6 (4) | 2 (1) |

| EN | 67 | 18 (27) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| CR | 73 | 16 (22) | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| Americas | EN+CR | 545 | 134 (25) | 25 (5) | 15 (3) |

| EN | 201 | 42 (21) | 7 (3) | 3 (1) | |

| CR | 344 | 92 (27) | 18 (5) | 12 (3) | |

| Europe | EN+CR | 9 | 3 (33) | 3 (33) | 2 (22) |

| EN | 4 | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | |

| CR | 5 | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | |

| Pacific | EN+CR | 80 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| EN | 32 | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| CR | 48 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Total | EN+CR | 914 | 214 (23) | 41 (4) | 20 (2) |

| EN | 387 | 63 (16) | 16 (4) | 6 (2) | |

| CR | 527 | 123 (23) | 25 (5) | 14 (3) | |

CR, critically endangered; EN, endangered.

*Percentages of corresponding total number of species in all AZE sites are in parentheses.

Direct Impacts of Urban Expansion on Carbon Pools

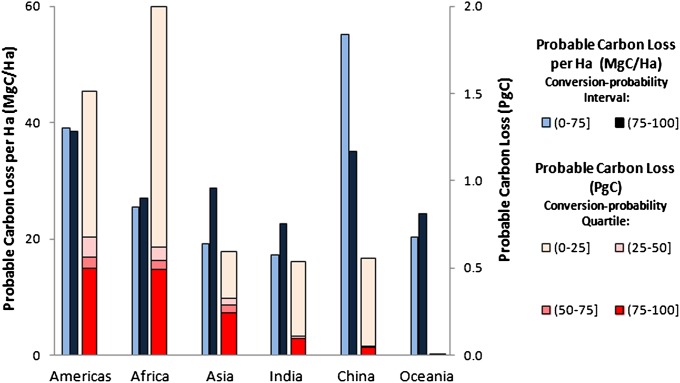

Deforestation and forest degradation are currently estimated to contribute 6–17% of total anthropogenic CO2 emissions (19), with the vast majority originating in the tropics. Until recently, urbanization was viewed as a negligible driver of deforestation (20, 21). However, annual deforestation rates have been decreasing since the mid-1990s, but urban extent has been increasing globally over the last three decades (3). Based on independent space-borne Geosciences Laser Altimeter System light detection and ranging measurements (22), we estimate the immediate aboveground biomass carbon losses associated with land clearing from projected high-probability (>75%) new urban areas in the pan-tropics to be 1.38 PgC between 2000 and 2030 (0.05 PgC yr−1) (Fig. 2), representing ∼5% of the tropical deforestation and land use change emissions (22). Although carbon losses associated with new urban areas can occur in the more degraded portions of forests due to their proximity to existing settlements, the carbon losses reported here capture these carbon density differences through variation in measured vegetation structure and disturbance status (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Average (MgC/ha) and total carbon (PgC) loss by region within the pan-tropics based on the probability of conversion in 2030.

Both the carbon density and probability of conversion vary regionally within the tropics, with the greatest probable losses most likely in the Americas and Africa, 0.50 and 0.49 PgC, respectively (Fig. 2). However, the highest carbon densities are in the tropical Americas and China. The total regional carbon losses reflect both the carbon density and the amount of land likely to be converted to urban within each region. Therefore, although carbon density is lower in Africa than in China, the forecasts show more urban expansion in pan-tropical Africa, resulting in a greater total regional carbon loss. Indeed, the majority of China—and the forecasted urban expansion—is not in the pan-tropics but rather the northern temperate zone.

Aboveground carbon losses from urban expansion in the tropics are likely to represent a large fraction of the immediate urbanization carbon losses because of the high tropical forest carbon densities and high urban growth rates in this region. Nonetheless, the 1.38 PgC carbon loss reported here is likely a lower-bound estimate of urban growth-related carbon losses because 63% of the projected new urban land is outside the pan-tropics and will contribute to additional carbon and biomass losses. Furthermore, although there is a paucity of data, the soil carbon losses associated with expanding impervious surface cover have the potential to reduce soil carbon pools by 66% (23). As with most land-cover changes, new urban areas can contain remnant patches of vegetation and the amount of vegetation can increase with time since clearing and development (24). However, the vegetation within urban areas is typically more fragmented (25) and can contain an altered species assemblage depending on growing conditions and social preferences (26).

Discussion

Since the first release in 1969 of the report Growth of the World’s Urban and Rural Population, 1920–2000, the United Nations has become the primary source of global urbanization projections. Although the United Nations World Urbanization Prospects provide country-level information on the percentage of populations in urban areas, they do not give intracountry variations of urban population distribution, the location of urban areas, or changes in urban land cover. Our study complements the information provided by the United Nations by providing spatially explicit probabilistic forecasts of urban expansion. Numerous models of urban expansion exist, but most focus on individual cities, city-regions, or in a few cases, countries (27, 28). To understand how urbanization will affect Earth system functioning and the global environment, we need to begin developing spatially explicit global forecasts of urban expansion that go beyond the demographic dimension.

Our analysis generates probability estimates of whether a 25 km2 area will become urban, based on a combination of population and GDP projections, and existing population densities and urban extents (see SI Materials and Methods). Our high-probability forecast of 1.2 million km2 of new urban land by 2030 is equivalent to an area about the size of South Africa. Put another way, using only the high-probability forecast, 65% of all urban land area on the planet in 2030 will become urban during the first three decades of the 21st century. This forecast suggests a brief window of opportunity for policy decisions to shape the long-term effects of urbanization. The forecasted growth in urban extent will be concomitant with an enormous infrastructure boom in road construction, water and sanitation, energy and transport, and buildings that will transform land cover and cities globally. Recent estimates suggest that between $25 and $30 trillion US dollars will be spent on infrastructure worldwide by 2030, with $100 billion a year in China alone (29). Given the long life and near irreversibility of infrastructure investments, it will be critical for current urbanization-related policies to consider their lasting impacts. There also may be potential cobenefits between urban sustainability policies and conservation policies. High-density urban communities have lower per capita energy use and greenhouse emissions than low-density suburban development (30, 31). Compact development could serve a secondary goal of saving land for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services. However, realization of these synergies requires more holistic policies that integrate traditional urban sectors—transport, energy, sanitation, buildings—with land use and conservation.

The wide range in forecasts of urban expansion reflects the uncertainties in the underlying drivers, such as population growth. History has proven some past projections of population growth to be grossly inaccurate (32) and there still remain large uncertainties around population-growth estimates (33). Additionally, for many developing and emerging economies, population and economic growth may explain only a small fraction of the urban land expansion. For example, GDP is a strong driver of urban land expansion in China but only moderately affects urban expansion in India and Africa, where urban population growth is a larger factor (3). Moreover, our model does not include the informal economy, which is estimated to contribute as much as 44% of the Gross National Product in Africa (34).

The results show that within individual countries, there is both high spatial variability and high spatial concentration of the likelihood of urban expansion. For example, the United Nations identifies 58 high-fertility countries, 39 of which are in Africa, where the bulk of population growth will occur in the near future (35). Our analysis provides more geographic detail and shows that within the 39 African countries, urban expansion is highly likely to be concentrated in only a few regions (Fig. S2). Contrary to expectations, countries with similar rates of population or economic growth do not result in the same probabilities of urban expansion. The results show two major potential types of future urban expansion: high probability of urban growth in specific locations and low probability of urban growth over large areas. For example, there is high probability that the northern shores of Lake Victoria, from Kampala, Uganda to Kisumu, Kenya, will become a continuous built-up area.

The 2012 United Nations urban population projections indicate that Nigeria’s cities are expected grow by 200 million people over the next 40 y (11). Our spatially explicit projections, developed before the release of the most recent United Nations report, show that Nigeria will experience high probabilities of urban expansion in specific locations, mainly in the Kano region and around Port Harcourt along the southern coast, a region vulnerable to climate change impacts and where a majority of the population lives in informal settlements (36). In these and other regions with high likelihoods of urban expansion, there is a need to develop preemptive land use and conservation strategies to mitigate the negative consequences of urbanization. Furthermore, although the results show that there is high probability that the land will become urban, the form and structure of the built environment remains to be determined. In countries like Yemen, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq with low probabilities of urban expansion across large areas, there is a high degree of uncertainty about where and how urban expansion will take place. Under such conditions, land-use planning, the location of foreign investments, the establishment of free trade or export processing zones, and investments in infrastructure could shape the location and form of future urban growth.

If all areas with high probability (>75%) become urban, the urban land cover in the biodiversity hotspots around the world will increase by more than 200% between 2000 and 2030, with substantial variations in the rate and amount of increase across individual hotspots (Table 2). There is also significant heterogeneity in the quality of habitat within each hotspot, and therefore not every location within a hotspot will be equally important for conservation (10). However, even relatively small decreases in habitat can cause extinction rates to rise disproportionately in already diminished and severely fragmented habitats, such as the Mediterranean and the Atlantic Forest hotspots. All five biodiversity hotspots with the largest percentages of their land areas forecasted to become urban predominantly occupy coastal regions or are islands (Table 2). In addition, although projected urban expansion in the Caribbean Islands and the Philippines is relatively small in total area, they are home to 1.9% and 2.3% of the world’s endemic plants and 1.9% and 2.9% of endemic invertebrates, respectively (10). Large numbers of AZE species will face increasing pressure from urban expansion in the next two decades. Although urbanization rates will be highest in China and India, it is in Central and South America where the largest number of AZE species will be affected (Table 3). Our results suggest the need for conservation policies that consider urban growth at both regional and global scales. The threat to biodiversity hotspots comes from direct land-cover change and subsequent loss of habitat, and from increased colonization by introduced species as urban areas expand. Establishing biodiversity corridors in these regions with higher probability of urban expansion will require coordinated efforts among multiple cities and municipalities. Such corridors may take on additional significance considering the migration of species in response to shifts in their ranges with climate change (37).

Most efforts that study terrestrial carbon dynamics have avoided areas heavily influenced by urbanization (24). However, the process of urban expansion also results in carbon emissions because of the land clearing, reductions in local primary productivity (8) and, depending on the climate and density of the new development, has the potential to either increase or decrease per capita greenhouse gas emissions. The aboveground carbon and habitat losses highlight that urban expansion is an important driver of land-cover change and forest degradation. The biomass carbon losses reported here represent short-term emissions associated clearing for urban development and land-cover change. As with most land-cover change, vegetation can regrow over time, but the annualized emissions associated with deforestation and forest degradation do not capture those long-term changes.

The analysis in this article only examines the direct spatial “imprint” of urban expansion on biodiversity hotspots, AZE species, and carbon biomass, and not the indirect land-change processes that both drive and respond to urbanization. Urban expansion can also affect land uses in distal places, which in turn can alter carbon stocks, especially in the tropics (20, 38). This “indirect” urbanization affect is difficult to fully quantify. In some cases, it will amplify and in other cases attenuate carbon losses. We know that cities have always relied on their hinterlands and other distal places for resources from food and fuel to waste assimilation. For example, a typical household in Sydney or Melbourne is responsible for greenhouse gas emissions, water withdrawals, and land use distributed across all of Australia (39). The magnitude of the virtual carbon, water, and land embodied in urban areas means that the bulk of environmental impacts from future urban expansion is also likely to occur outside of the areas forecasted to become urban.

Although a full assessment of the indirect environmental impacts of urban expansion is beyond the scope of this analysis, two urbanization factors are known to have significant indirect environmental effects. First, the spatial pattern of urban development, such as compactness, employment and residential densities, and mix of land uses affects energy use and carbon dioxide emissions (40). Second, urban consumption patterns are often different from rural counterparts. For example, the composition of urban diets is considerably higher in meat and dairy intake than rural counterparts (41). In turn, a diet higher in meat also increases the demand for fodder. Thus, the indirect effects of urbanization, including increased affluence and changes in consumption patterns, are highly uncertain and potentially very large. Both direct and indirect components need to be considered to fully account for the environmental impacts of urban expansion.

Conclusions

Urbanization is often considered a local issue. However, our analysis shows that the direct impacts of future urban expansion on global biodiversity hotspots and carbon pools are significant. At the same time, the full environmental impacts will not be confined to urban boundaries and will largely be felt elsewhere. Although populations are increasingly living in urban areas, the results show that there is large spatial variation in the magnitude and location of urban expansion between and within countries.

That the first 30 y of the 21st century is highly likely to experience more urban land expansion than all of history suggests a considerable—and limited—window of opportunity to shape future urbanization. For guidance on how policies could help, we should look to Aldo Leopold and the prescient words of Sir Alex Gordon, past president of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Gordon’s ideas of “long life,” “loose fit,” and “low energy” (42) suggest that future urbanization should avoid infrastructure “lock-in,” be adaptable to unforeseen demands, and have low embodied and operating energy needs. Applying Leopold’s “land ethic” (43) to the concept of urban sustainability requires that the connections between urban processes and land-use change are made explicit and that future considerations about sustainable cities incorporate direct and indirect changes in the land brought about by urbanization.

Materials and Methods

Forecasting Urban Expansion Globally.

We use five sources of data to forecast urban expansion: global urban extent circa 2000 from National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (12), urban population projections to 2030 from the United Nations, population projection uncertainty ranges from the US National Research Council (14), population density estimates from the Global Rural-Urban Mapping Project, and country-level GDP projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Reports on Emissions Scenarios (15). We develop models for 16 geographic regions, broadly based on United Nations defined world regions (Table S1). The forecasts are developed in two phases. In the first phase, for each region we generate 1,000 estimates of aggregate amount of urban expansion by randomly drawing 1,000 values each from the corresponding probability density functions (PDFs) of projected GDP and urban population. We use the uncertainty ranges in population and GDP projections to estimate the corresponding PDFs. In the second phase, we use the aggregate amounts and simulate their spatial distribution using a spatially explicit grid-based land-change model (44), which uses slope, distance to roads, population density, and land cover as the primary drivers of land change. Our analysis assumes no new road development. Significant changes in road development would change the spatial patterns but not the amount of new urban expansion. See SI Materials and Methods and Figs. S3–S5 for more details.

Urbanization Impacts on Biodiversity Hotspots, Endangered and Critically Endangered Species, and Carbon Pools.

For the hotspot analysis, we use established global biodiversity hotspots databases (10, 16). For the impacts on species evaluated to be Endangered or Critically Endangered under IUCN-World Conservation Union criteria, we use the AZE dataset (17). For the carbon-loss analysis, we use the Woods Hole Research Center, pan-tropical aboveground carbon density map (22). Biomass is assumed to be 50% carbon (45). Carbon loss because of urban expansion is estimated by overlaying the measured carbon density map with the probabilistic urban expansion map and calculating the aboveground carbon present in each conversion probability quartile.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gil Pontius for providing the source code for the land change model, GEOMOD, Alessandro Baccini for use of the pan-tropic biomass data, and the Texas A&M Supercomputing Facility for providing computational resources.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1211658109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Seto KC, Sanchez-Rodriguez R, Fragkias M. The new geography of contemporary urbanization and the environment. Annu Rev Environ Resour. 2010;35:167–194. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angel S, Parent J, Civco DL, Blei A, Potere D. The dimensions of global urban expansion: Estimates and projections for all countries, 2000–2050. Prog Plann. 2011;75:53–107. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seto KC, Fragkias M, Güneralp B, Reilly MK. A meta-analysis of global urban land expansion. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimm NB, et al. Global change and the ecology of cities. Science. 2008;319:756–760. doi: 10.1126/science.1150195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKinney ML. Effects of urbanization on species richness: A review of plants and animals. Urban Ecosyst. 2008;11:161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald RI, Kareiva P, Forman RTT. The implications of current and future urbanization for global protected areas and biodiversity conservation. Biol Conserv. 2008;141:1695–1703. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKinney ML. Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation. Bioscience. 2002;52:883–890. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imhoff ML, et al. Global patterns in human consumption of net primary production. Nature. 2004;429:870–873. doi: 10.1038/nature02619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pimm SL, Raven P. Biodiversity. Extinction by numbers. Nature. 2000;403:843–845. doi: 10.1038/35002708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GAB, Kent J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 2000;403:853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations 2012. World Urbanization Prospects, the 2011 Revision (United Nations, New York) Available at: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/index.htm (Accessed June 3, 2012)

- 12.Schneider A, Friedl M, Potere D. A new map of global urban extent from MODIS satellite data. Environ Res Lett. 2009;4:044003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations . World Urbanization Prospects: The 2009 Revision. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs/Population Division; 2010. Available at: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/index.htm. Accessed April 11, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Research Council (U.S.) Beyond Six Billion: Forecasting the World’s Population. Washington, DC: National Research Council; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakicenovic N, et al. Special Report on Emissions Scenarios: A Special Report of Working Group III of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittermeier RA, et al. Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Ecoregions. Mexico City, Mexico: CEMEX; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alliance for Zero Extinction 2010. AZE Update. Available at: www.zeroextinction.org (Accessed June 1, 2012)

- 18.Ricketts TH, et al. Pinpointing and preventing imminent extinctions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18497–18501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509060102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Werf GR, et al. CO2 emissions from forest loss. Nat Geosci. 2009;2:737–738. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeFries RS, Rudel T, Uriarte M, Hansen M. Deforestation driven by urban population growth and agricultural trade in the twenty-first century. Nat Geosci. 2010;3:178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutyra LR, Yoon B, Hepinstall-Cymerman J, Alberti M. Carbon consequences of land cover change and expansion of urban lands: A case study in the Seattle metropolitan region. Landsc Urban Plan. 2011;103:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baccini A, et al. Estimated carbon dioxide emissions from tropical deforestation improved by carbon-density maps. Nature Climate Change. 2012;2:182–185. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raciti SM, Hutyra LR, Finzi AC. Depleted soil carbon and nitrogen pools beneath impervious surfaces. Environ Pollut. 2012;164:248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutyra LR, Yoon B, Alberti M. Terrestrial carbon stocks across a gradient of urbanization: a study of the Seattle, WA region. Glob Change Biol. 2011;17:783–797. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberti M. The effects of urban patterns on ecosystem function. Int Reg Sci Rev. 2005;28:168–192. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hope D, et al. Socioeconomics drive urban plant diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8788–8792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537557100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eigenbrod F, et al. The impact of projected increases in urbanization on ecosystem services. Proc Biol Sci. 2011;278:3201–3208. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nowak DJ, Walton JT. Projected urban growth (2000–2050) and its estimated impact on the US forest resource. J For. 2005;103:383–389. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tal B. 2009. Capitalizing on the Upcoming Infrastructure Stimulus. Available at: http://research.cibcwm.com/economic_public/download/occrept66.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2012.

- 30.Norman J, Maclean HL, Asce M, Kennedy CA. Comparing high and low residential density: Life-cycle analysis of energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. J Urban Plann Dev. 2006;132:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall JD. Energy-efficient urban form. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:3133–3137. doi: 10.1021/es087047l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alho JM. Scenarios, uncertainty and conditional forecasts of the world population. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 1997;160:71–85. doi: 10.1111/1467-985x.00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen B. Urban growth in developing countries: A review of current trends and a caution regarding existing forecasts. World Dev. 2004;32:23–51. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gërxhani K. The informal sector in developed and less developed countries: A literature survey. Public Choice. 2004;120:267–300. [Google Scholar]

- 35.United Nations . World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision. Vol I and II. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obinna VC, Owei OB, Mark EO. Informal settlements of Port Harcourt and potentials for planned city expansion. Environmental Research Journal. 2010;4:222–228. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loarie SR, et al. The velocity of climate change. Nature. 2009;462:1052–1055. doi: 10.1038/nature08649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seto KC, et al. Urban land teleconnections and sustainability. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:7687–7692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117622109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lenzen M, Peters GM. How city dwellers affect their resource hinterland. J Ind Ecol. 2010;14:73–90. [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Research Council . Driving and the Built Environment: The Effects of Compact Development on Motorized Travel, Energy Use, and CO2 Emissions–Special Report 298. Washington, DC: National Academies; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popkin BM. Global nutrition dynamics: The world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:289–298. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon A. Architects and the energy crisis. Building. 1973;225:107–111. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leopold A. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pontius RG, Cornell JD, Hall CAS. Modeling the spatial pattern of land-use change with GEOMOD2: Application and validation for Costa Rica. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2001;85:191–203. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown S. Estimating Biomass and Biomass Change of Tropical Forests: A primer. New York: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.