Abstract

Bacteria frequently manifest distinct phenotypes as a function of cell density in a phenomenon known as quorum sensing (QS). This intercellular signalling process is mediated by “chemical languages comprised of low-molecular weight signals, known as” autoinducers, and their cognate receptor proteins. As many of the phenotypes regulated by QS can have a significant impact on the success of pathogenic or mutualistic prokaryotic–eukaryotic interactions, there is considerable interest in methods to probe and modulate QS pathways with temporal and spatial control. Such methods would be valuable for both basic research in bacterial ecology and in practical medicinal, agricultural, and industrial applications. Toward this goal, considerable recent research has been focused on the development of chemical approaches to study bacterial QS pathways. In this Perspective, we provide an overview of the use of chemical probes and techniques in QS research. Specifically, we focus on: (1) combinatorial approaches for the discovery of small molecule QS modulators, (2) affinity chromatography for the isolation of QS receptors, (3) reactive and fluorescent probes for QS receptors, (4) antibodies as quorum “quenchers,” (5) abiotic polymeric “sinks” and “pools” for QS signals, and (6) the electrochemical sensing of QS signals. The application of such chemical methods can offer unique advantages for both elucidating and manipulating QS pathways in culture and under native conditions.

A. Introduction

Many bacteria can modify their behaviour as a function of cell density using the cell–cell signalling pathway termed quorum sensing (QS).1–3 QS challenges the traditional notion of bacteria as autonomous agents by permitting them to function as multicellular groups and thrive in specific environmental niches. This phenomenon does not appear to be species specific, as QS between different species of bacteria has been observed and some eukaryotic hosts are even believed to “eavesdrop” on the signals that regulate QS.4,5 QS-regulated phenotypes in bacteria are diverse and include virulence factor production, biofilm formation, root nodulation, sporulation, bioluminescence, and motility. As many of these phenotypes can have significant impacts on human health, agricultural yields, industrial manufacturing, and ecology, there is intense and growing interest in developing methods to regulate QS pathways.2,3,6,7

QS is mediated by diffusible low-molecular weight signals, generically classified as autoinducers (AIs), and their cognate receptor proteins (Fig. 1). These AIs either passively diffuse out of the cell (and into others) or are actively transported. As the AI concentration in a given environment can be correlated with the number of bacteria present, the AI level thus serves as an effective indicator of cell density. Binding of the AIs to their target (intracellular or membrane-bound) receptors activates the transcription of genes required for QS phenotypes, along with those associated with AI biosynthesis. Only as the population reaches a sufficient density (or “quorum”) in a given environment will adequate gene transcription occur for the QS phenotype to manifest. Increased production of the AI signal once a quorum is reached enhances the sensitivity of the signalling process (i.e., autoinduction) and facilitates population-wide synchronization of the QS-regulated phenotype.

Fig. 1.

General schematic of the QS process in bacteria. Pentagons represent autoinducer (AI) signals. A. LuxR/LuxI-type QS in Gram-negative bacteria. B. QS system in certain Gram-positive bacteria.

The Gram-negative Proteobacteria utilize N-acylated L-homoserine lactones (AHLs) as their primary AIs for QS (Fig. 2A). AHL-based QS circuits have been studied extensively over the past 25 years and will be a primary focus of this perspective.1 In general, AHLs share a conserved L-HL head group, while receptor selectivity is dictated by modifications to the AHL acyl tail structure, including the number of carbons, the oxidation state at the 3-position, or the presence of a cis-alkene. AHLs are produced by LuxI-type synthases and perceived by cytoplasmic receptors termed LuxR-type proteins (Fig. 1A).8 AHL binding to their cognate LuxR-type receptor initiates homodimerization of these complexes, which is typically followed by their association to QS-specific promoter sites and the subsequent transcription of QS-related genes. In contrast, certain Gram-positive bacteria use peptide-based QS signalling molecules, which are detected by membrane-bound receptors (Fig. 1B).9 The autoinducing peptides (AIPs) used by Staphylococcus aureus (Fig. 2C) represent some of the most studied QS signals of this class.

Fig. 2.

Examples of AIs used by bacteria for QS. A. N-acylated L-homoserine lactones (AHLs) found in Gram-negative bacteria. B. Autoinducer-2 (AI-2) found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. C. Group I autoinducing peptide (AIP-I) used by Staphylococcus aureus. D. The Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal (PQS) used by Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Genetic approaches have provided extensive insight into the molecular machinery regulating QS circuits, as well as the significance of specific QS phenotypes under native conditions.2,10–13 However, these small molecule “languages” have also inspired numerous chemical approaches aimed at elucidating mechanistic aspects of QS and modulating QS phenotypes. The relative structural simplicity of these signals, especially the AHLs, has inspired several research groups to design and synthesize analogues of these signals for use as non-native QS agonists and antagonists. These focused synthetic approaches have yielded sets of compounds that have been screened for QS modulatory activity. Beyond their potential value as chemical probes, one commonly proposed application for such ligands is for the attenuation of virulence factor production and biofilm formation. Indeed, small molecule QS inhibitors represent an exciting alternative to conventional antimicrobial approaches that ultimately promote resistance.6,14,15 Several outstanding reviews of the development of non-native AHL analogues are now available.1,16–18

In addition to these targeted analogue studies, a variety of other chemical strategies have been applied to QS research over the past decade. Reports of these chemical methods, however, remain largely scattered throughout the literature. Our goal herein is to summarize these chemical-based strategies and place them in context of their potential utility to the larger QS field. Specifically we focus on: (1) combinatorial approaches for the discovery of small molecule QS modulators, (2) affinity chromatography for the isolation of QS receptors, (3) reactive and fluorescent probes for QS receptors, (4) antibodies as quorum “quenchers”, (5) abiotic polymeric “sinks” and “pools” for QS signals, and (6) the electrochemical sensing of QS signals. We highlight throughout how this diversity of chemical techniques can complement biological approaches and ultimately lead to an improved understanding of bacterial QS.

B. Combinatorial approaches for the discovery of QS modulators

Traditional synthetic approaches have yielded small collections of synthetic AI analogues, and several potent QS modulators have emerged from these studies. As the synthesis of each compound typically requires their individual isolation, purification, and reaction optimization, the application of these synthetic routes to the study of larger sets of analogues can rapidly become cumbersome. Therefore, technology that can facilitate the synthesis of potential QS modulators, while simultaneously expanding the size and diversity of these libraries, would accelerate research efforts. In this section, we discuss combinatorial synthesis approaches for the discovery of small molecule QS modulators, with a particular focus on methods involving solid-phase synthesis.19 Solid-phase synthesis is now a standard methodology for the generation of small molecule libraries due to the ease of compound purification, as well as its compatibility with automation.20

Synthesis of AHL analogues on polystyrene resins

Our laboratory was amongst the first to apply solid-phase synthesis techniques to the construction of AHL analogue libraries. We developed a robust synthesis strategy utilizing polystyrene beads that incorporated several microwave-assisted reactions and a CNBr cyclative–cleavage step for the rapid synthesis of both native and non-native AHLs in high purities and good yields (shown in Fig. 3).21,22 The key diversification step in this route was the acylation reaction following the Fmoc deprotection of resin-bound L-methionine. Given the large number of commercially available carboxylic acids, the approach facilitates the construction of a wide assortment of AHLs with structurally diverse acyl chains. We have utilized this solid-phase synthetic strategy to generate over 200 non-native AHLs, and have identified numerous LuxR-type protein agonists and antagonists in ~10 different bacterial species through the systematic screening of these analogues.22–25 Among the most potent of these compounds are the phenylacetyl homoserine lactones (PHLs), several of which are strong agonists and antagonists of QS in the marine mutualist Vibrio fischeri, as well as the plant pathogens Pectobacterium carotovora and Pseudomonas syringae.26 Notably, these compounds have been shown to attenuate QS phenotypes both in culture and in eukaryotic host infections.27 The rich quantity of structure–activity relationship data that has emerged from these studies is now guiding the synthesis of next-generation compounds with improved activity towards specific LuxR-type receptors.25

Fig. 3.

Top: Polystyrene-based solid-phase synthesis of AHLs, as described by Geske et al.21,22 DIC = N,N′-diisopropylcarbodiimide; HOBt = 1-hydroxybenzotriazole; Fmoc = 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl group; Met = methionine; CNBr = cyanogen bromide; TFA = trifluoroacetic acid; μW = microwave irradiation; rt = room temperature. Bottom: Generic structures of QS modulators generated utilizing this synthetic methodology. From left to right: phenylacetyl homoserine lactone, phenoxyacetyl homoserine lactone, and phenylpropionyl homoserine lactone.

Synthesis of AHL analogues using small molecule macro-arrays

Another solid-phase synthesis technique that has been applied to the discovery of QS modulators is the small molecule macroarray.28–30 Such macroarrays permit the spatially-addressed synthesis of small molecules on planar polymeric supports (e.g., cellulose filter paper) to generate focused libraries of varying sizes (~100–1000). Reagents are delivered directly onto spots on the support, and multi-step reactions can be performed by washing the support between each step. With its low cost, ease of construction, mechanical stability, and compatibility with both conventional and microwave heating, the microarray platform has proven to be a viable technique for the synthesis of a range of small molecule libraries.31–33 This approach is also advantageous because hydrophilic planar supports are amenable to many on-support biological assays, further accelerating the discovery of bioactive agents.

Prior to our work in this area, macroarray (or “SPOT”) synthesis was largely limited to the construction and testing of peptide libraries.34–36 However, over the last decade, our laboratory has worked to develop this synthesis and screening platform for a variety of new chemical and biological applications.21,31,33,37–40 We have shown that many chemical reactions beyond carbodiimide couplings are compatible with the cellulose support, including aldol, “click”, Suzuki, and Heck reactions.33,37–42 By applying the macroarray technique to the construction of AHL libraries, we sought to further explore the scope and limitations of this approach. We also envisioned that the planar support format would permit us to readily screen the resulting AHL libraries in bacteriological assays for QS activity.

We developed an acid-mediated cyclative–cleavage strategy43,44 to synthesize a library of non-native AHLs on a macro-array (cellulose) platform (Fig. 4A).45 Two libraries of non-native AHLs were generated rapidly in high purities, and then subjected to direct, on-support biological testing. These studies demonstrated that the macroarray platform was fully compatible with AHL synthesis. Furthermore, the biological screens revealed several new QS antagonists in both V. fischeri and Chromobacterium violaceum. Notably, the C. violaceum assay was performed in an agar overlay format on the intact support following spatially-addressed cleavage, thereby bypassing the need for the individual isolation of compounds prior to screening. As QS in C. violaceum regulates production of the brilliant purple dye, violacein, inhibitors could be easily identified by visual inspection of the agar overlay for colourless circles. Overall, this study serves to highlight the potential utility of the small molecule macroarray platform for bacteriological research.

Fig. 4.

Combinatorial approaches to the synthesis QS modulators. A. Macroarray synthesis of AHLs by Praneenararat et al.45 B. Macroarray synthesis of diketopiperazines (DKPs) by Campbell et al.46 C. 3D microarrays devised by Spring and co-workers.50–52 Top: individual amino-containing compounds can be printed on an N-hydroxysuccinimide activated slide. This array could be probed with fluorescently-labelled CarR (a LuxR-type protein in P. carotovora) for binding assays. Bottom: catch-and-release 3D microarrays allow the synthesis of amides that were non-covalently deposited onto the support. Reagents and abbreviations: CDI = 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole; NMI = N-methylimidazole; Trt = trityl group; DBU = 1,8-diazabicyclo-[5.4.0]undec-7-ene; Boc = tert-butyloxycarbonyl group; Cy3 = a cyanine fluorescent dye.

Synthesis of diketopiperazines (DKPs) using small molecule macroarrays

We have also utilized a macroarray synthesis approach for the construction of a library of diketopiperazines (DKPs).46 DKPs have been reported to exhibit activity in a range of QS reporter strains, yet questions remain regarding their role as native QS signal molecules.47,48 We developed a straightforward approach for the synthesis of DKPs based on an Ugi 4-component coupling and a cyclative–cleavage strategy, which generated the final ~400-member library in excellent purities and yields (Fig. 4B). Analysis of the DKP library revealed a small set of strong QS antagonists in V. fischeri. Ongoing studies are focused on clarifying the mechanism(s) by which these DKPs inhibit QS, as well as the relevance of the native DKP “signals” identified in bacteria. This study further showcases the value of the macroarray as a chemical tool for QS research.

Synthesis of AHL analogues using small molecule micro-arrays

In addition to macroarrays, microarray techniques have also been adapted as tools for the combinatorial synthesis of QS modulators.49 While the underlying basis of these techniques is analogous to that for macroarray synthesis, the scale of the chemistry is significantly smaller and often requires automation. Spring and co-workers recently developed a novel “3D” polyethylene glycol (PEG) microarray using acrylic ester silane slides (Fig. 4C, top) for the discovery of small molecule QS modulators.50–52 Utilizing this 3D hydrophilic support, the authors sought to increase the small-molecule loading capacity per spot, while simultaneously reducing the potential for non-specific interactions in on-support binding studies. N-Hydroxy-succinimide ester slides were functionalized with AHLs (synthesized separately) via reaction with amino groups installed at their acyl chain termini. Spring’s team then demonstrated that AHLs covalently tethered to the 3D microarray could bind a LuxR-type protein (CarR from E. carotovora) labelled with the fluorescent dye Cy3.51 Subsequent cell-based assays utilizing free AHLs confirmed that the hits identified in the microarray-binding assay were valid QS modulators. The small scale of this microarray approach should provide distinct advantages for the synthesis and screening of sizable compound libraries.

Spring and co-workers subsequently refined their microarray synthesis technique by demonstrating that AHL synthesis could be performed directly on their 3D slides (Fig. 4C, bottom).52 This strategy offers the aforementioned advantages of the authors’ microarray approach, while simultaneously providing a platform amenable to both the synthesis and biological testing, similar to the small molecule macroarray strategy described above. Two native AHLs were synthesized on this microarray platform, but biological studies are yet to be reported.

Synthesis of AIP analogues on polystyrene resins

Solid-phase combinatorial strategies have also been applied to the synthesis of non-native analogues of the AIPs used by S. aureus for QS (Fig. 2C).53 These signals bind to their cognate receptor, the membrane-bound histidine kinase AgrC, which phosphorylates the response regulator AgrA and initiates expression of the QS regulator. S. aureus strains can be divided into four separate “groups” (I–IV), each of which uses a distinct AIP and cognate AgrC receptor. Interestingly, while these AIPs induce QS in their own group, they simultaneously inhibit QS in the other three groups. It has been suggested that this QS cross-talk regulates the composition of the bacterial community in a given S. aureus infection.

Motivated to identify the structural features of individual AIPs that were necessary to inhibit both non-cognate and cognate AgrC receptors, Muir and co-workers developed an efficient synthesis for AIPs on polystyrene beads.53 They designed their own linker system that was subsequently attached to the Rink linker, facilitating the synthesis of a set of non-native AIP analogues. These analogues were then tested for their QS modulatory activities in S. aureus reporter strains for each group. The resulting data revealed several important SARs for the AIPs, as well as valuable insights into the relevant structural features that regulate intergroup interactions for these signals.

In synergistic work, our lab developed a synthetic approach to macrocyclic peptide–peptoid hybrids (or “peptomers”) designed to mimic AIPs in S. aureus. We found that these peptomers could be generated via efficient microwave-assisted coupling reactions on Wang-linker derivatized polystyrene beads, and released from the resin in a macrocyclization-cleavage step.54 A small focused library of AIP mimetics was synthesized. Subsequent biological assays indicated that one of the peptomers could stimulate biofilm formation in S. aureus to a higher level than untreated controls, suggesting that it could modulate AgrC activity. This study revealed that peptoid-based AIP analogues could be useful as QS probes in S. aureus.

Synthesis of Pseudomonas Quinolone Signal (PQS) analogues

In addition to solid phase synthetic approaches, combinatorial libraries of QS modulators have also been generated using other techniques. In a notable example, the Spring group successfully coupled microwave and flow methods to systematically synthesize non-native analogues of PQS, a signalling molecule that P. aeruginosa uses in concert with AHLs for QS (Fig. 2D).55 Combining these two synthetic approaches, the authors generated a 17-member library of PQS analogues in short reaction times and good isolated yields, with minimal purification steps. These compounds could serve as valuable probes to study this less characterized QS signalling pathway in P. aeruginosa.56

C. AI affinity resins and reactive signal analogues

Beyond the development of synthetic AI analogues as QS modulators, chemical approaches have also been developed for identifying, isolating, and probing ligand-receptor interactions in QS circuits. In this section, we discuss a variety of chromatographic and chemical labelling approaches to study QS receptors.

Affinity chromatography approaches

Determining the target of a bioactive small molecule can be exceedingly difficult, especially if the target is produced at low levels, or if the molecule has low affinity for the target.57–59 As a result, methods that facilitate target identification are of significant value, and affinity “pull-down” assays represent one popular chemical approach.60 Affinity chromatography is based on the binding interaction between a molecule (such as a small molecule or a larger biomacromolecule) that is immobilized to a support (e.g., agarose resin) and its binding counterpart that is contained in the mobile phase (eluent). Association of these two molecules allows the counterpart to be isolated from the eluent, released from the support under alternate conditions, and subjected to a variety of methods to determine its identity (e.g., gel electrophoresis, immunological staining, mass spectrometry (MS), etc.).

Several research groups have developed affinity-based methods to facilitate the identification of new AI receptors, both in bacteria and eukaryotes. Spandl et al. have described the synthesis of biotin-tagged N-3-oxo-hexanoyl L-homoserine lactone (OHHL) for the purposes of identifying AHL-binding receptors (Fig. 5A).61 The biotin tag allows for this ligand to be readily immobilized to an avidin-functionalized support. While biological assays utilizing this support have yet to be pursued, the authors did outline a plausible future strategy utilizing 2D-difference gel electrophoresis to elucidate molecular targets for OHHL.

Fig. 5.

Various AHL-based chemical tools. A. Biotin-tagged AHL described by Spandl et al.61 B. Piperazine-modified AHLs synthesized by Seabra et al.63 C. Alkynyl and azido AHLs synthesized by Garner et al.64 D. Amino AHL for affinity pull-down assays by Praneenararat et al.67 E. Diazirine and alkynyl-tagged AHL reported Dubinsky et al.71 F. Isothiocyanate AHL reported by Amara et al.72 G. BODIPY-tagged AHL reported by Rayo et al.73.

Similarly, Seabra et al. have developed affinity resins for the identification of putative eukaryotic receptors for AHLs. This study was specifically motivated by the immunological responses stimulated by the exposure of mammalian cells to N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl L-homoserine lactone (OdDHL, from P. aeruginosa).62 The authors synthesized two piperazine-modified OdDHL derivatives and attached them to agarose resin (Fig. 5B).63 Two proteins were isolated from lysates of mammalian cells using these OdDHL-modified resins; however, neither was of any immunological relevance. Despite this outcome, such resins could ultimately prove useful for the detection of novel AHL binding proteins in other contexts.

Garner et al. have reported a concise study of AHL derivatives that has implications for subsequent target identification studies using affinity resins (Fig. 5C).64 This group synthesized a series of azido and alkynyl OdDHL analogues for eventual tethering to solid supports via “click” reactions. Initial biological testing of these precursors in a P. aeruginosa reporter strain revealed that, unexpectedly, they had drastically different activity profiles, even though such modifications to the acyl group are generally considered fairly minor.65,66 These results underscore the necessity of evaluating the activities of modified AHL derivatives prior to resin attachment.

Recently, our laboratory has developed an AHL-derivatized affinity resin for the isolation and identification of AHL-binding partners. We began by functionalizing an OdDHL derivative with a primary amine at its acyl chain terminus and then coupling it to N-hydroxysuccinimide agarose resin (Fig. 5D).67 We found that this modified resin selectively bound to QscR, a LuxR-type receptor target of OdDHL, from a crude lysate of a P. aeruginosa QscR overexpression strain. Isolation of QscR from wild-type P. aeruginosa has proven more challenging and may be due to the low native expression levels of QscR.68–70 Non-specific protein binding to such lipophilic resins is also problematic. Nevertheless, this work represents the first use of an AHL-derived affinity resin for the isolation and identification of LuxR-type receptors. Ongoing work in our group is focused on utilizing this approach to prepare other AHL-resins for application in both bacterial and eukaryotic systems.

Photoaffinity and other chemical labelling strategies

Photo-affinity labelling is another effective method to study the interactions of small molecule ligands with putative targets.74 Several photoactivatable groups can be used in probe design, and diazirines represent a prominent class.75 Meijler and co-workers provided the first evidence that such reactive probes could be used to covalently modify and study LuxR-type proteins. The authors reported the synthesis of a bifunctional OdDHL analogue that contained both an alkyne and a diazirine (Fig. 5E),71 and showed that this analogue retained comparable biological activity in LasR as OdDHL. P. aeruginosa cultures were treated with the alkyne-diazirine analogue followed by exposure of the crude lysates to UV light. Subsequent analysis of the lysates by MS revealed that this modified OdDHL was covalently bound to LasR in the native OdDHL binding site.

In related work, Meijler and co-workers have also developed irreversible inhibitors of the LasR receptor.72,73 They reasoned that the strategic addition of an electrophilic group to OdDHL would permit selective reaction to a cysteine residue in the LasR OdDHL binding site.72 The Meijler team tested this hypothesis by appending electrophilic groups onto the acyl chain termini of a series of OdDHL analogues. They determined that isothiocyanate analogues of OdDHL (Fig. 5F) reacted selectively with the desired cysteine residue in LasR (determined by MS/MS), and that these compounds showed promising QS inhibitory activities in cell-based assays. This study was the first to describe covalent inhibitors of LuxR-type receptors and highlights the potential utility of such molecules for both the selective labelling and modulation of these receptors.

Building on this work, the Meijler group used one of their isothiocyanate OdDHL analogues to develop a method for the fluorescent imaging of LasR in P. aeruginosa cells (Fig. 5G).73 The authors treated cells with the isothiocyanate OdDHL derivative, and then added a fluorescent BODIPY derivative. This amino-functionalized dye was capable of reaction with the 3-keto group of the OdDHL derivative, forming a stable oxime adduct. Thus, the dye could be used to study the localization of LasR in living cells. The authors observed that LasR mostly localized to the poles of the cell, and hypothesized that LuxR-type proteins may be segregated from their related LuxI-type synthases (known to be closer to the centre of the cell) in order to more accurately gauge the presence of other cells in a given environment and facilitate the QS process. While additional studies are needed to support this exciting hypothesis, these results underscore the potential value of such chemical probes to further elucidate the mechanisms of QS using imaging techniques.

D. Quorum “quenching” antibodies

As outlined above, the use of AI mimics to “intercept” the association of native AI signals with their cognate receptor is one strategy for inhibiting QS. Alternate strategies to accomplish this same outcome are certainly available, however. The use of antibodies to “quench” QS by binding or inactivating native QS signals is one such strategy that has gained considerable attention.81 In this approach, AIs (or derivatives thereof) are used to elicit immune responses in a host animal to stimulate the production of monoclonal antibodies. These antibodies are highly selective for the AI molecules, and can be applied to biological systems to sequester or degrade AIs, thereby effectively quenching the QS process. Antibody-based approaches have considerable potential for both fundamental studies as well as for future vaccine development. A summary of recent examples is provided below.

Designing antibodies to sequester AIs

Raising antibodies to function as quorum quenchers requires a molecular template (or “hapten”) for immunization. In general, small molecules, like AHLs, cannot play this role by themselves but rather need to be coupled to carrier proteins to elicit antibody production.82 Furthermore, the hydrolytic instability of the AHL lactone ring makes them poor haptens, as they degrade during the time required for antibodies to be generated.83 Janda and co-workers circumvented this problem by substituting the oxygen in the AHL ring with a nitrogen, to form the more stable lactam.76 They designed three lactam analogues of OdDHL, linked them to carrier proteins, used these conjugates to elicit immune responses in mice, and isolated an antibody (RS2-1G9) raised from the RS2 hapten (shown in Fig. 6A). RS2-1G9 was both highly specific for OdDHL (Kd = 150 nM) and capable of inhibiting QS phenotypes in P. aeruginosa (e.g., pyocyanin production).76,84,85

Fig. 6.

Haptens used to prepare quorum quenching antibodies. A. RS2 hapten reported by Kaufmann et al.76 with a modified atom (in red) from the original lactone ring. B. AIP-IV analog with an ester group (in red) instead of the natural thioester group reported by Park et al.77 C. Squaric monoester monoamide hapten reported by De Lamo Marin et al.78 originally utilized to generate catalytic antibodies that hydrolyze paraoxon.79 D. A sulfone transition state mimic for AHL hydrolysis as reported by Kapadnis et al.80

The Janda group has also applied this strategy to the AIPs from S. aureus by raising antibodies against a close analogue of AIP-IV (Fig. 6B).77 The major concern in hapten design in this case was the hydrolytic instability of the native thioester in the AIP macrocycle. Replacement with an ester bond proved successful, however, yielding a macrocyclic lactone analogue. The most promising antibody, AP4-24H11, was an extremely potent inhibitor of QS in S. aureus cultures. Moreover, the antibody suppressed pathogenicity in mouse S. aureus infection assays. These results certainly support the further investigation of antibodies for the prevention or treatment of S. aureus infections.

Designing catalytic antibodies to inhibit QS

Another approach to antibody-based quorum quenching is to develop catalytic antibodies capable of degrading AIs and rendering them inactive.86 This approach is inspired by naturally occurring AHL-degrading enzymes such as lactonases (catalyzing the ring-opening of the AHL lactone) and amidases (catalyzing the cleavage of the AHL amide bond).87 De Lamo Marin et al. first evaluated this approach by screening catalytic antibodies for lactonase activity.78 Specifically, they examined an existing library of antibodies known to catalyze the hydrolysis of the insecticide paraoxon. The authors reasoned that while the squaric monoester monoamide hapten to which these antibodies were raised did not directly resemble an AHL (Fig. 6C), it could yield antibodies also capable of AHL ring hydrolysis. Indeed, the authors successfully identified an antibody (XYD-11G2) in their library capable of hydrolyzing OdDHL and suppressing QS in P. aeruginosa cultures.

Spring and co-workers have also made contributions in the quorum quenching area. They hypothesized that haptens designed to mimic the transition state of the lactone hydrolysis reaction would yield antibodies with improved catalytic activity.80 Using the pseudo-tetrahedral transition state of lactone hydrolysis as a guide, they designed and synthesized three sulfones as stable surrogates of this transition state. In a preliminary study, one of these sulfones (Fig. 6D) was able to inhibit the activity of AiiA, a known AHL lactonase, in a competitive manner. While antibodies raised against these sulfones have yet to be reported, it will be exciting to learn whether these haptens will result in antibodies with improved AHL lactonase activity.

E. Abiotic polymers for QS modulation

Sequestration of the AI signal to effectively quench QS is not limited to antibodies. Non-native polymeric materials can also serve as “sinks” for QS signals and achieve similar outcomes. Similarly, synthetic materials capable of serving as “pools” for the release of QS modulators in a time dependent manner could be useful in a variety of practical applications and as probes of QS processes. In this section, we discuss several examples of such materials-based approaches for the modulation of QS.

Polymer “sinks” for AHLs

Piletska et al. used computational modelling and prior affinity studies to select a set of monomers with functional groups capable of favourable binding interactions with OHHL, an AHL signal used by V. fischeri.88 The authors reasoned that polymers containing these monomers could potentially sequester OHHL and thus suppress QS. Indeed, polymers based on itaconic acid (IA, Fig. 7A) were found to have a relatively high OHHL-binding capacity. For example, 5% w/w IA polymers were found to have an OHHL binding capacity of ~45 mg g−1 of polymer and were able to significantly inhibit QS in V. fischeri while not affecting bacterial growth.

Fig. 7.

Abiotic polymers used to study QS. A. Poly-itaconic acid used to sequester OHHL88 or OdDHL.89 B. 2-Hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin used to trap AHLs by interacting with the acyl tail.91,92 C. Poly(N-dopamine methacrylamide-co-N-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]methacrylamide) designed to capture the boron-containing AI-2 signal and promote cell adhesion.94 D. PLG used for the controlled release of AHLs.95

Piletska et al. have since refined their polymer production process by utilizing molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs).89 MIPs are similar to antibodies on some levels as the polymers are synthesized around a template molecule, resulting in the formation of high specificity binding pockets.90 MIPs can thus sequester signals that are similar to their templating molecule, serving as a “sink”. In an elegant proof of principle study, the authors generated IA-based MIPs using OdDHL as a template, and then demonstrated that the resulting polymer could inhibit QS-mediated biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa.

In related work, Kato et al. have reported that the supramolecule 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HP-β-CD, Fig. 7B) can also serve as an AHL “sink”.91,92 Previous studies had established that AHLs are able to interact with the inner cavity of α- and β-cyclodextrins via hydrophobic interactions, suggesting that HP-β-CD might also bind AHLs.93 As anticipated, HP-β-CD was found to reduce the expression of QS regulated genes in strains of Serratia marcescens91 and P. aeruginosa.92 The authors then cross-linked HP-β-CD to sheets of 2-hydroxypro-pylcellulose to generate an AHL-sequestering material that could be deployed in a range of practical applications. These HP-β-CD-linked sheets were subsequently found to reduce the expression of QS-associated genes when added to bacterial cultures.

Bifunctional polymers for synergistic QS attenuation – Xue et al. hypothesized that the incorporation of two chemical moieties capable of modulating both bacterial QS and adhesion into a single polymer would yield a bifunctional material with heightened QS inhibitory activity. Towards this goal, the authors synthesized a polymer containing monomer units that had a high binding affinity for the boron atom found in the QS signal AI-2 (Fig. 2B), along with monomers known to promote bacterial cell adhesion.94 In theory, such a polymer would attenuate QS by isolating bacteria within a matrix via adhesion (thereby reducing overall cell density in the culture) and then by sequestering AI-2 as it exited the cell. One example of such a polymer is based on 3-(dimethylamino)propylamine, which is known to generally promote bacterial cell adhesion, and N-dopamine, which contains two phenolic alcohols that have a strong affinity for boron, (Fig. 7C). The authors confirmed that this polymer could efficiently sequester bacterial cells and attenuate the QS-regulated bioluminescence of Vibrio harveyi. While this study was preliminary, their bifunctional approach to QS inactivation could provide a novel antimicrobial strategy for future applications.

Polymer “pools” for the controlled release of AIs

In contrast to the “sink” approach outlined above, the “pool” strategy is based on the development of materials that control the release of QS modulators into the environment. Such “pool”-type materials could have numerous applications for the time dependent release and spatial localization of QS modulators (e.g., coatings for surgical implants, biofilm control, etc.), yet have not been studied extensively to date.

Our lab recently demonstrated the use of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLG, Fig. 7D) as a matrix to control the delivery of AHLs.95 A key issue limiting the utility of AHL-based QS modulators over time is their hydrolytic instability. However, PLG polymer films provide an acidic microenvironment, and are well known to stabilize base-sensitive compounds that are impregnated into the film. We therefore reasoned that PLG films containing AHLs could serve to prolong the effective lifetime of AHLs in culture. In this preliminary study, we confirmed that a model AHL can be released from PLG over time, and that both the AHL concentration and time of release could be readily controlled (from minutes to days). Next, we utilized a V. fischeri QS reporter assay to determine that the released compound retained its biological activity. Notably, the AHL exhibited significantly lower EC50 values when slowly released from the PLG film relative to when added to solution in a bolus, supporting our hypothesis that the PLG scaffold inhibits lactone hydrolysis. These results provide a new materials-based approach for QS modulation that could be useful in a range of contexts.

F. Electrochemical techniques to study QS

In this last section, we turn our focus to recent electrochemical methods that have been developed to monitor QS phenotypes. These techniques are dependent on the presence of redox-active molecules and can offer a variety of advantages over the analytical methods described in the previous sections (MS, UV, etc.). Such advantages include minimal sample preparation, low cost, and superior selectivity toward structurally similar compounds or even the same elements with different oxidation states,96 the last of which is usually impractical for methods like UV spectroscopy.

Pyocyanin as an electrochemical probe

The first application of electrochemical techniques to the study of QS was reported by Bukelman et al., who evaluated the QS-regulated production of pyocyanin in P. aeruginosa.97 As pyocyanin can undergo a reversible two-electron redox reaction, it is suitable for electrochemical studies (Fig. 8A). The authors first verified a suitable electrode potential for the pyocyanin redox reaction by cyclic voltammetry, and then used differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) to quantify pyocyanin content. To verify that changes in pyocyanin concentrations as measured by DPV were QS regulated, they compared DPV readings between wild-type P. aeruginosa and a P. aeruginosa OdDHL-synthase mutant (ΔlasI). The results confirmed that pyocyanin was only synthesized in appreciable quantities by the mutant in the presence of its native AHL ligand, OdDHL. Utilizing this technique, the authors went on to evaluate the activity of two known QS antagonists and determined that their IC50 values in the electrochemical assays were generally consistent with those ascertained by standard cell-based techniques.

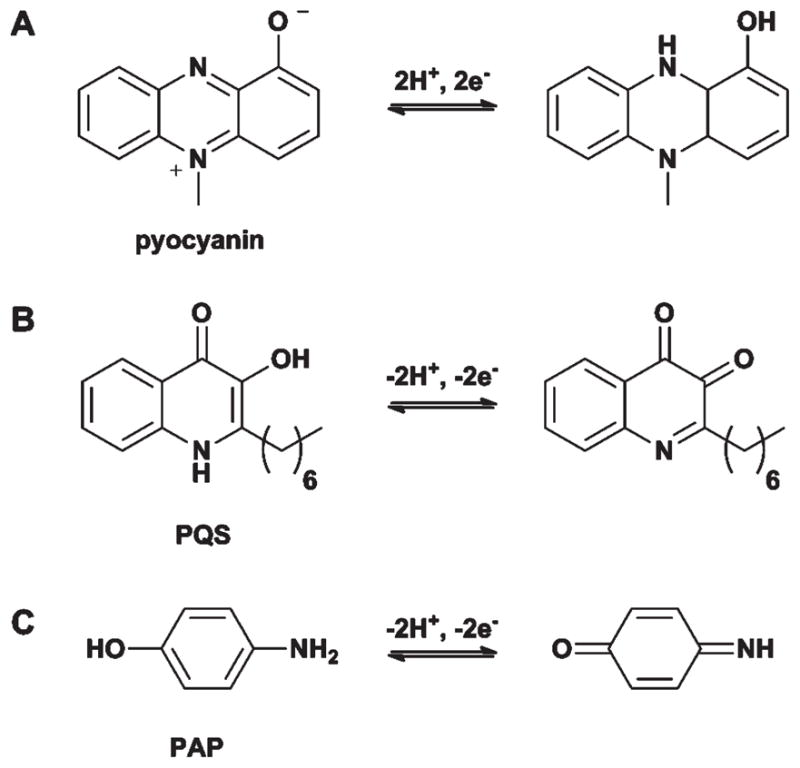

Fig. 8.

Redox-active molecules used for the electrochemical analysis of QS. A. Pyocyanin used by Bukelman et al.97 and Sharp et al.98 B. PQS used by Zhou et al.99 C. p-Aminophenol (PAP) used by Baldrich et al.100

In a more recent study, Sharp et al. also utilized pyocyanin to develop an electrochemical sensor for P. aeruginosa.98 While the underlying chemical principles were the same as those in the study above, these authors focused on the development of a pyocyanin detector for medically relevant applications. Towards this goal, they developed a reusable carbon fibre electrode capable of monitoring pyocyanin concentrations. Pyocyanin measurements obtained through this technique were in good agreement with other methods. This versatile probe could be used in a variety of settings to provide rapid and sensitive evaluation of P. aeruginosa QS.

PQS as an electrochemical probe

Another QS molecule that has been the subject of electrochemical analysis is PQS (Fig. 2D and 8B). Monitoring the quantity of PQS in P. aeruginosa cultures is complicated by the presence of 2-heptyl-4-quinolone (HHQ), a precursor in the biosynthesis of PQS. However, using a boron-doped diamond electrode, Zhou et al. identified conditions (by varying pH and electrode potential) where HHQ and PQS gave drastically different electrochemical responses.99 Consequently, they could apply these conditions to selectively detect and quantify PQS from P. aeruginosa cultures (with a detection limit of 1 nM). Given the structural similarity of the two molecules, it would be difficult to monitor their concentrations separately using other methods.

In contrast to these two direct, small molecule monitoring approaches, Baldrich et al. developed an indirect electrochemical approach to study QS. This method involves the detection of a redox-active by-product generated by the enzyme β-galactosidase (β-gal), a common reporter used in QS cell-based assays.100 Specifically, the authors utilized 4-aminophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside (PAPG, Fig. 8C) as a substrate for β-gal, which is cleaved to yield the redox active p-aminophenol (PAP). The authors first identified conditions that permitted the electrochemical discrimination between the redox responses of the substrate (PAPG) and the product (PAP). Thereafter, they utilized an Agrobacterium tumefaciens reporter strain that produces β-gal in response to AHLs to show increased and decreased current at the PAP and PAPG electrodes, respectively, upon AHL exposure. Using this strategy, the authors reported the ability to detect OdDHL in a variety of cultures (including artificial saliva) and at low concentrations (pico- to nanomolar ranges). While no direct comparison to other AHL quantification methods was made in this study, the authors commented that the OdDHL values they obtained were comparable to previously published work.101

G. Summary and outlook

Chemical methods have the potential to significantly enable QS research, and can complement ongoing microbiological, genetic, and systems biology efforts in this area. The relative simplicity of many QS pathways, particularly LuxR-type systems, makes them ideal targets for the development of chemical approaches to regulate and understand interorganismal interactions. We contend that the extent to which chemical approaches can be utilized to clarify and modulate QS pathways is limited, in part, only by the imagination of researchers. Herein, we have reviewed a number of recent applications of chemical techniques to the study of QS, including those based on organic, combinatorial, polymer, and electroanalytical chemistry. We have no doubt that these methods will be increasingly exploited in QS research, and we envisage that as their accessibility increases, such approaches will become routine in the laboratory. Looking forward, we are excited to both learn from and be directly involved in the development of these molecular-level approaches to expand and translate the languages of bacterial QS.

Acknowledgments

The NIH (AI063326), ONR (N000140710255), Johnson & Johnson, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund are each acknowledged for their generous support of QS research in our laboratory. We apologize to those authors that we could not cite in this Perspective due to space limitations.

References

- 1.Galloway WRJD, Hodgkinson JT, Bowden SD, Welch M, Spring DR. Chem Rev. 2011;111:28–67. doi: 10.1021/cr100109t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng WL, Bassler BL. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:197–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uroz S, Dessaux Y, Oger P. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:205–216. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer WD, Mathesius U. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:429–433. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teplitski M, Mathesius U, Rumbaugh KP. Chem Rev. 2011;111:100–116. doi: 10.1021/cr100045m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Njoroge J, Sperandio V. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:201–210. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierson LS, Maier RM, Pepper IL. Environmental Microbiology. 2. Elsevier Inc; 2009. pp. 335–346. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuqua C, Greenberg EP. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:685–695. doi: 10.1038/nrm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thoendel M, Horswill AR. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2010;71:91–112. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(10)71004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta P, Goyal S, Long T, Bassler BL, Wingreen NS. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:325. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churchill ME, Chen L. Chem Rev. 2011;111:68–85. doi: 10.1021/cr1000817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yarwood JM, Bartels DJ, Volper EM, Greenberg EP. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1838–1850. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.6.1838-1850.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaper JB, Sperandio V. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3197–3209. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3197-3209.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasko DA, Moreira CG, Li de R, Reading NC, Ritchie JM, Waldor MK, Williams N, Taussig R, Wei S, Roth M, Hughes DT, Huntley JF, Fina MW, Falck JR, Sperandio V. Science. 2008;321:1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1160354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasko DA, Sperandio V. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2010;9:117–128. doi: 10.1038/nrd3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geske GD, O’Neill JC, Blackwell HE. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1432–1447. doi: 10.1039/b703021p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattmann ME, Blackwell HE. J Org Chem. 2010;75:6737–6746. doi: 10.1021/jo101237e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens AM, Queneau Y, Soulere L, von Bodman S, Doutheau A. Chem Rev. 2011;111:4–27. doi: 10.1021/cr100064s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terrett NK, Gardner M, Gordon DW, Kobylecki RJ, Steele J. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:8135–8173. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyle NA, Janda KD. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2002;6:339–346. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geske GD, Wezeman RJ, Siegel AP, Blackwell HE. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12762–12763. doi: 10.1021/ja0530321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geske GD, O’Neill JC, Miller DM, Mattmann ME, Blackwell HE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13613–13625. doi: 10.1021/ja074135h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geske GD, Mattmann ME, Blackwell HE. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5978–5981. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geske GD, O’Neill JC, Miller DM, Wezeman RJ, Mattmann ME, Lin Q, Blackwell HE. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:389–400. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mattmann ME, Shipway PM, Heth NJ, Blackwell HE. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:942–949. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer AG, Streng E, Jewell KA, Blackwell HE. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:138–147. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer AG, Streng E, Blackwell HE. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:1348–1356. doi: 10.1021/cb200298g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frank R. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:9217–9232. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pirrung MC. Chem Rev. 1997;97:473–488. doi: 10.1021/cr960013o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackwell HE. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bowman MD, Jeske RC, Blackwell HE. Org Lett. 2004;6:2019–2022. doi: 10.1021/ol049313f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lange T, Lindell S. Comb Chem High Throughput Screening. 2005;8:595–606. doi: 10.2174/138620705774575445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowman MD, Jacobson MM, Pujanauski BG, Blackwell HE. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:4715–4727. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eichler J. Comb Chem High Throughput Screening. 2005;8:135–143. doi: 10.2174/1386207053258497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schutkowski M, Reineke U, Reimer U. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:513–521. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reimer U, Reineke U, Schutkowski M. Mini-Rev Org Chem. 2011;8:137–146. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin Q, O’Neill JC, Blackwell HE. Org Lett. 2005;7:4455–4458. doi: 10.1021/ol051684o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowman MD, Jacobson MM, Blackwell HE. Org Lett. 2006;8:1645–1648. doi: 10.1021/ol0602708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin Q, Blackwell HE. Chem Commun. 2006:2884–2886. doi: 10.1039/b604329a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowman MD, O’Neill JC, Stringer JR, Blackwell HE. Chem Biol. 2007;14:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frei R, Blackwell HE. Chem–Eur J. 2010;16:2692–2695. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stringer JR, Bowman MD, Weisblum B, Blackwell HE. ACS Comb Sci. 2011;13:175–180. doi: 10.1021/co100053p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guillier F, Orain D, Bradley M. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2091–2158. doi: 10.1021/cr000014n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blaney P, Grigg R, Sridharan V. Chem Rev. 2002;102:2607–2624. doi: 10.1021/cr0103827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Praneenararat T, Geske GD, Blackwell HE. Org Lett. 2009;11:4600–4603. doi: 10.1021/ol901871y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Campbell J, Blackwell HE. J Comb Chem. 2009;11:1094–1099. doi: 10.1021/cc900115x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holden MTG, Chhabra SR, de Nys R, Stead P, Bainton NJ, Hill PJ, Manefield M, Kumar N, Labatte M, England D, Rice S, Givskov M, Salmond GPC, Stewart GSAB, Bycroft BW, Kjelleberg SA, Williams P. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1254–1266. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Degrassi G, Aguilar C, Bosco M, Zahariev S, Pongor S, Venturi V. Curr Microbiol. 2002;45:250–254. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3704-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walsh DP, Chang YT. Comb Chem High Throughput Screening. 2004;7:557–564. doi: 10.2174/1386207043328427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marsden DM, Nicholson RL, Ladlow M, Spring DR. Chem Commun. 2009:7107–7109. doi: 10.1039/b913665g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marsden DM, Nicholson RL, Skindersoe ME, Galloway WRJD, Sore HF, Givskov M, Salmond GPC, Ladlow M, Welch M, Spring DR. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:5313–5323. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00300j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boehner CM, Marsden DM, Sore HF, Norton D, Spring DR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:5930–5932. [Google Scholar]

- 53.George EA, Novick RP, Muir TW. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4914–4924. doi: 10.1021/ja711126e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fowler SA, Stacy DM, Blackwell HE. Org Lett. 2008;10:2329–2332. doi: 10.1021/ol800908h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hodgkinson JT, Galloway WRJD, Saraf S, Baxendale IR, Ley SV, Ladlow M, Welch M, Spring DR. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:57–61. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hodgkinson J, Bowden SD, Galloway WRJD, Spring DR, Welch M. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:3833–3837. doi: 10.1128/JB.00081-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burdine L, Kodadek T. Chem Biol. 2004;11:593–597. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harding MW, Galat A, Uehling DE, Schreiber SL. Nature. 1989;341:758–760. doi: 10.1038/341758a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taunton J, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leslie BJ, Hergenrother PJ. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1347–1360. doi: 10.1039/b702942j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spandl RJ, Nicholson RL, Marsden DM, Hodgkinson JT, Su X, Thomas GL, Salmond GPC, Welch M, Spring DR. Synlett. 2008:2126–2122. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Telford G, Wheeler D, Williams P, Tomkins PT, Appleby P, Sewell H, Stewart GSAB, Bycroft BW, Pritchard DI. Infect Immun. 1998;66:36–42. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.36-42.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seabra R, Brown A, Hooi DSW, Kerkhoff C, Chhabra SR, Harty C, Williams P, Pritchard DI. Calcium Binding Proteins. 2008;3:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garner AL, Yu J, Struss AK, Lowery CA, Zhu J, Kim SK, Park J, Mayorov AV, Kaufmann GF, Kravchenko VV, Janda KD. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:2702–2705. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.11.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bottomley MJ, Muraglia E, Bazzo R, Carfi A. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13592–13600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zou YZ, Nair SK. Chem Biol. 2009;16:961–970. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Praneenararat T, Beary TMJ, Breitbach AS, Blackwell HE. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5054–5057. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chugani SA, Whiteley M, Lee KM, D’Argenio D, Manoil C, Greenberg EP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2752–2757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051624298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee JH, Lequette Y, Greenberg EP. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:602–609. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oinuma KI, Greenberg EP. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:421–428. doi: 10.1128/JB.01041-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dubinsky L, Jarosz LM, Amara N, Krief P, Kravchenko VV, Krom BP, Meijler MM. Chem Commun. 2009:7378–7380. doi: 10.1039/b917507e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amara N, Mashiach R, Amar D, Krief P, Spieser SpAH, Bottomley MJ, Aharoni A, Meijler MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:10610–10619. doi: 10.1021/ja903292v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rayo J, Amara N, Krief P, Meijler MM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7469–7475. doi: 10.1021/ja200455d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen YX, Triola G, Waldmann H. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:762–773. doi: 10.1021/ar200046h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith DP, Anderson J, Plante J, Ashcroft AE, Radford SE, Wilson AJ, Parker MJ. Chem Commun. 2008:5728–5730. doi: 10.1039/b813504e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaufmann GF, Sartorio R, Lee SH, Mee JM, Altobell LJ, Kujawa DP, Jeffries E, Clapham B, Meijler MM, Janda KD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2802–2803. doi: 10.1021/ja0578698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Park J, Jagasia R, Kaufmann GF, Mathison JC, Ruiz DI, Moss JA, Meijler MM, Ulevitch RJ, Janda KD. Chem Biol. 2007;14:1119–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.De Lamo Marin S, Xu Y, Meijler MM, Janda KD. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:1549–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.12.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu Y, Yamamoto N, Ruiz DI, Kubitz DS, Janda KD. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:4304–4307. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kapadnis PB, Hall E, Ramstedt M, Galloway WRJD, Welch M, Spring DR. Chem Commun. 2009:538–540. doi: 10.1039/b819819e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Amara N, Krom BP, Kaufmann GF, Meijler MM. Chem Rev. 2010;111:195–208. doi: 10.1021/cr100101c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Landsteiner K, van der Scheer J. J Exp Med. 1936;63:325–339. doi: 10.1084/jem.63.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kaufmann GF, Sartorio R, Lee SH, Rogers CJ, Meijler MM, Moss JA, Clapham B, Brogan AP, Dickerson TJ, Janda KD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:309–314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408639102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaufmann GF, Park J, Mee JM, Ulevitch RJ, Janda KD. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:2710–2714. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Debler EW, Kaufmann GF, Kirchdoerfer RN, Mee JM, Janda KD, Wilson IA. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:1392–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu Y, Yamamoto N, Janda KD. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:5247–5268. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang LH, Dong YH. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1563–1571. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Piletska EV, Stavroulakis G, Karim K, Whitcombe MJ, Chianella I, Sharma A, Eboigbodin KE, Robinson GK, Piletsky SA. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:975–980. doi: 10.1021/bm901451j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Piletska EV, Stavroulakis G, Larcombe LD, Whitcombe MJ, Sharma A, Primrose S, Robinson GK, Piletsky SA. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:1067–1071. doi: 10.1021/bm101410q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vasapollo G, Del Sole R, Mergola L, Lazzoi MR, Scardino A, Scorrano S, Mele G. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:5908–5945. doi: 10.3390/ijms12095908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kato N, Morohoshi T, Nozawa T, Matsumoto H, Ikeda T. J Inclusion Phenom Macrocyclic Chem. 2006;56:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kato N, Tanaka T, Nakagawa S, Morohoshi T, Hiratani K, Ikeda T. J Inclusion Phenom Macrocyclic Chem. 2007;57:419–423. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ikeda T, Morohoshi T, Kato N, Inoyama M, Nakazawa S, Hiratani K, Ishida T, Kato J, Ohtake H. 10th Asia Pacific Confederation of Chemical Engineering; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xue X, Pasparakis G, Halliday N, Winzer K, Howdle SM, Cramphorn CJ, Cameron NR, Gardner PM, Davis BG, Fernandez-Trillo F, Alexander C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:9852–9856. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Breitbach AS, Broderick AH, Jewell CM, Gunasekaran S, Lin Q, Lynn DM, Blackwell HE. Chem Commun. 2011;47:370–372. doi: 10.1039/c0cc02316g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Skoog DA, Leary JJ. Principles of Instrumental Analysis. 4. Saunders College Publishing; Fort Worth: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bukelman O, Amara N, Mashiach R, Krief P, Meijler MM, Alfonta L. Chem Commun. 2009:2836–2838. doi: 10.1039/b901125k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sharp D, Gladstone P, Smith RB, Forsythe S, Davis J. Bioelectrochemistry. 2010;77:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhou L, Glennon JD, Luong JHT, Reen FJ, O’Gara F, McSweeney C, McGlacken GP. Chem Commun. 2011;47:10347–10349. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13997e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baldrich E, Muñoz FX, García-Aljaro C. Anal Chem. 2011;83:2097–2103. doi: 10.1021/ac1028243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Charlton TS, de Nys R, Netting A, Kumar N, Hentzer M, Givskov M, Kjelleberg S. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2:530–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]