Abstract

The solute carrier 6 (SLC6) family of the human genome comprises transporters for neurotransmitters, amino acids, osmolytes and energy metabolites. Members of this family play critical roles in neurotransmission, cellular and whole body homeostasis. Malfunction or altered expression of these transporters is associated with a variety of diseases. Pharmacological inhibition of the neurotransmitter transporters in this family is an important strategy in the management of neurological and psychiatric disorders. This review provides an overview of the biochemical and pharmacological properties of the SLC6 family transporters.

LINKED ARTICLES

BJP published a themed section on Transporters in 2011. To view articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.2011.164.issue-7/issuetoc

Keywords: monoamine transporters, antidepressants, transport mechanism, transporter pharmacology

Introduction and overview

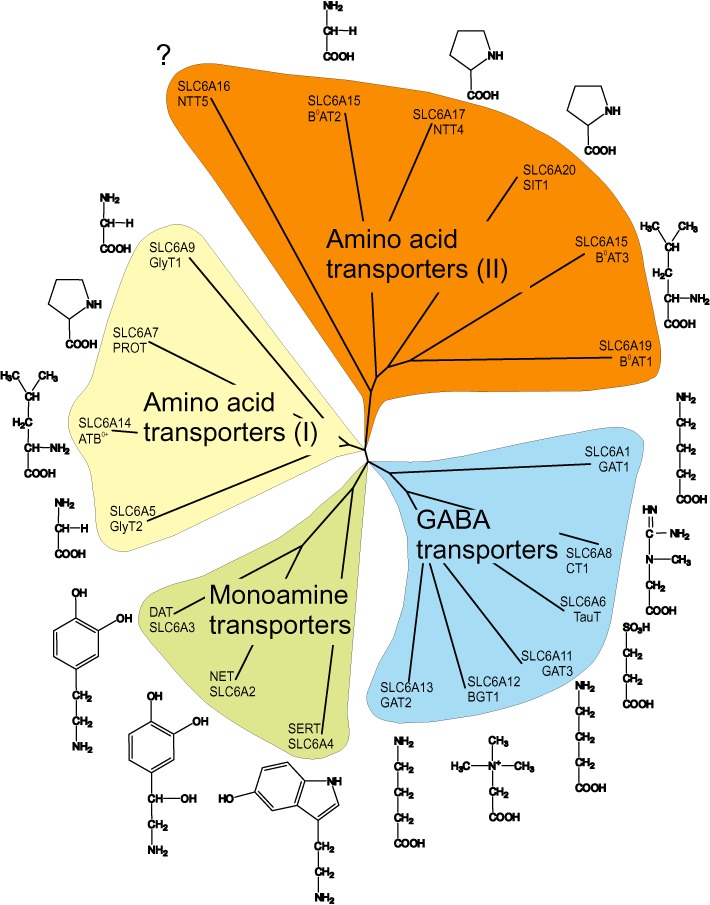

The solute carrier family 6 (SLC6) has 20 members in the human genome (Chen et al., 2004; Broer, 2006). It comprises transporters for neurotransmitters, proteinogenic amino acids, betaine, taurine and creatine. The neurotransmitter transporters were the first identified members, and hence, it is also known as the family of neurotransmitter sodium symporters (NSS) or the Na+/Cl--dependent transporter family (Nelson, 1998; Beuming et al., 2006). Sequence similarity allows subdividing the SLC6 family into four branches, namely the GABA transporter branch, the monoamine transporter branch and the amino acid transporter branches (I) and (II) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequence similarity of SLC6 transporters. Peptide sequences of all human SLC6 members were aligned using T-coffee (Notredame et al., 2000), and similarities were visualized using Treeview (Page, 1996). The main substrate for each transporter is shown next to the name. Subfamilies are indicated.

The GABA transporter branch contains transporters for GABA, betaine, taurine and creatine. GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. Inhibition of GABA transporters will result in reduced clearance after synaptic release and therefore enhances the action of inhibitory synapses. Consequently, GABA transporter drugs are used to treat not only seizures but also pain and anxiety (Clausen et al., 2006). Taurine and betaine are both osmolytes (Lang, 2007), and creatine is a storage compound for high-energy phosphate bonds to replenish ATP, particularly in muscle and brain (Wallimann et al., 2011).

The monoamine transporter branch contains the neurotransmitter transporters for dopamine, 5-HT and noradrenaline. These neurotransmitters play a modulatory role in the CNS, affecting the activity of many pathways. They are particularly involved in the modulation of mood, aggression, anxiety, depression, addiction, appetite, attention etc. (Hahn and Blakely, 2007; Ramamoorthy et al., 2011). In general, inhibition of monoamine transporters will result in reduced clearance of monoamine transmitters after synaptic release, resulting in a more intense and prolonged signal. Certain drugs, in addition, elicit non-synaptic release of monoamine neurotransmitters through the transporter.

The amino acid transporter branch (I) (Figure 1) comprises transporters for glycine, proline and the general amino acid transporter ATB°,+ which is broadly specific for neutral (0) and cationic (+) amino acids. Glycine is not only the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the spinal cord but also modulates glutamatergic neurotransmission in the cortex by binding to the NMDA receptor. The glycine transporter GlyT1 is widely expressed in the brain, and it is thought to modulate glycine concentrations in the cortex, whereas GlyT2 is mainly found in the spinal cord. Glycine transporters are targeted for treatment of neuropathic pain and schizophrenia (Aragon and Lopez-Corcuera, 2005; Javitt, 2009). The proline transporter PROT1 is almost exclusively expressed in the brain, where its physiological role remains unclear. The general amino acid transporter ATB0,+ is found in lung and other epithelia and is thought to be involved in the clearance of amino acids from secreted fluids (Mager and Sloan, 2003).

The amino acid transporter branch (II) contains amino acid transporters involved in epithelial and brain amino acid transport (Broer, 2008). Most members of this branch accept a variety of neutral amino acids and therefore are involved in amino acid homeostasis. The epithelial transporters mediate the absorption of amino acids in the intestine and the re-absorption of amino acids from the primary urine in the kidney. The physiological role of the neural members of this branch is ill-understood. Most likely, they provide metabolic precursors for tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates to allow production of neurotransmitters.

Nomenclature

In addition to the SLC nomenclature, members of the SLC6 family are referred to by transporter names indicating substrate preference. Some transporters have been named independently by different groups or were renamed after their function was discovered. Table 1 provides a list, ordered by SLC number, which gives the most commonly used name and alternative names. Some transporters have splice variants resulting in a different peptide sequence, and these are listed as well. In this review, transporter nomenclature follows Alexander et al., (2011).

Table 1.

Overview and nomenclature of the SLC6 family

| SLC number | Common name | Alias | Protein variation | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC6A1 | GAT1 | GATA | Guastella et al. (1990) | ||

| SLC6A2 | NET | NAT1, NET1 | C-t var1 | Pacholczyk et al. (1991) | |

| C-t var2 | |||||

| SLC6A3 | DAT | Giros et al. (1991); Kilty et al. (1991) | |||

| SLC6A4 | SERT | 5-HTT | Blakely et al. (1991); Hoffman et al. (1991) | ||

| SLC6A5 | GlyT2 | GlyT2a | Smith et al. (1992a) | ||

| GlyT2b | |||||

| SLC6A6 | TauT | Liu et al. (1992a); Smith et al. (1992b); Uchida et al. (1992) | |||

| SLC6A6P | Pseudogene | ||||

| SLC6A7 | PROT | Fremeau et al. (1992) | |||

| SLC6A8 | CT1 | CRTR | Mayser et al. (1992); Guimbal and Kilimann (1993) | ||

| SLC6A9 | GlyT1 | GlyT1a | Guastella et al. (1992); Liu et al. (1992b) | ||

| GlyT1b | |||||

| GlyT1c | |||||

| GlyT1d | |||||

| GlyT1e | |||||

| SLC6A10 | CT2 | Pseudogene | |||

| SLC6A11 | GAT3 | GATB | Borden et al. (1992); Clark et al. (1992) | ||

| GAT4 (mouse) | |||||

| SLC6A12 | BGT1 | GAT2 (mouse) | Lopez-Corcuera et al. (1992); Yamauchi et al. (1992) | ||

| SLC6A13 | GAT2 | GAT3 (mouse) | Borden et al. (1992) | ||

| SLC6A14 | ATB0,+ | β-alanine carrier | Sloan and Mager (1999) | ||

| SLC6A15 | B0AT2 | v7-3, NTT73, SBAT1 | Uhl et al. (1992) | ||

| SLC6A16 | NTT5 | Farmer et al. (2000) | |||

| SLC6A17 | NTT4 | RXT1 | Uhl et al. (1992); Liu et al. (1993b) | ||

| SLC6A18 | B0AT3 | XT2, XTRP2 | 6 splice variants in mouse | Wasserman et al. (1994); Nash et al. (1998) | |

| SLC6A19 | B0AT1 | XT2s1 | Broer et al. (2004) | ||

| SLC6A20 | SIT1 | IMINO, XT3, XTRP3 | SLC6A20a | Smith et al. (1995); Nash et al. (1998) | |

| SLC6A20b | |||||

| In rodents | |||||

| SLC6A21P | Pseudogene |

Substrates and mechanism

The four branches of the SLC6 family have different substrate preferences (Figure 1 and Table 2). The monoamine transporter branch comprises transporters for the biogenic amines 5-HT (SERT), noradrenaline (NET) and dopamine (DAT). However, the substrate specificity is overlapping. DAT, for instance, can also transport noradrenaline and NET has a high affinity for dopamine (Gether et al., 2006). Furthermore, a recent study has provided evidence that SERT is capable of transporting dopamine, however, with lower substrate affinity, higher maximum velocity and the requirement for higher Na+ and Cl- to sustain transport (Larsen et al., 2011). Similarly, there is substantial substrate promiscuity in the GABA transporter branch. For example, β-alanine is not only a substrate for the taurine transporter but also for GABA transporters GAT-2 and GAT-3 and the amino acid transporter ATB0,+. Glycine is a substrate of the specific glycine transporters GlyT1 and GlyT2 and of the general amino acid transporters B0AT1, B0AT3 and ATB0,+. Betaine is transported by BGT-1 and also by SIT1. The overlapping substrate specificities within the SLC6 family can be rationalized: All substrates of the GABA transporter branch have a carboxyl group and an amino group in the β- or γ- position (Figure 1). In the case of creatine, the amino group is part of the guanidino group, and in the case of betaine, the amino-group is methylated. The exception is taurine, which has a sulphonate group in the β-position. Monoamine transporters accept decarboxylated derivatives of aromatic amino acids, while all other members transport amino acids. In some cases, site-directed mutagenesis of the substrate binding site has been used to alter the substrate specificity of SLC6 transporters (Dodd and Christie, 2007; Vandenberg et al., 2007).

Table 2.

Endogenous substrates and transport mechanism

| Transporter | Endogenous substrate | KM-values | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC6A1/GAT1 | GABA | 11 µM | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Loo et al. (2000) |

| SLC6A2/NET | noradrenaline | 0.4 µM | 1S:1Na(S):1Cl(S) | Pacholczyk et al. (1991); Gu et al. (1996) |

| dopamine | 0.7 µM | |||

| SLC6A3/DAT | dopamine | 2.5 µM | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Gu et al. (1994); Sonders et al. (1997) |

| noradrenaline | 20 µM | |||

| SLC6A4/SERT | 5-HT | 0.45 µM | 1S:1Na(S):1Cl(S):1 K(A) | Ramamoorthy et al. (1993); Rudnick (1998) |

| SLC6A5/GlyT2 | glycine | 27 µM | 1S:3Na(S):1Cl(S) | Roux and Supplisson (2000); Rees et al. (2006) |

| SLC6A6/TauT | taurine | 5 µM | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Ramamoorthy et al. (1994) |

| β-alanine | 56 µM | |||

| SLC6A7/PROT | proline | 6–10 µM (rat) | Not tested | Fremeau et al. (1992) |

| SLC6A8/CT1 | creatine | 77 µM | Not tested | Nash et al. (1994) |

| SLC6A9/GlyT1 | glycine | 72 µM | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Kim et al. (1994); Roux and Supplisson (2000) |

| SLC6A10 | pseudogene | |||

| SLC6A11/GAT3 | GABA | 7 µM | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Borden et al. (1994); Karakossian et al. (2005) |

| SLC6A12/BGT1 | GABA | 36 µM | 1S:3Na(S):1Cl(S) | Borden et al. (1995); Rasola et al. (1995); Matskevitch et al. (1999) |

| betaine | 934 µM | |||

| SLC6A13/GAT2 | GABA | 3.7 µM | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Sacher et al. (2002); Christiansen et al. (2007) |

| SLC6A14/ATB0,+ | Neutral and cationic amino acids | Non-polar 6–100 µM | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Sloan and Mager (1999) |

| Polar 100–600 µM | ||||

| Cationic 76–100 µM | ||||

| SLC6A15/B0AT2 | BCAA, Met, Pro | 40–200 µM | 1S:1Na(S) | Takanaga et al. (2005a); Broer et al. (2006) |

| SLC6A16/NTT5 | Unknown | |||

| SLC6A17/NTT4 | BCAA, Met, Pro, Ala, Gln | 360–5000 µM (rat) | 1S:1Na(S) | Parra et al. (2008); Zaia and Reimer (2009) |

| SLC6A18/B0AT3 | Gly, Ala | 900–2300 µM (mouse) | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Singer et al. (2009); Vanslambrouck et al. (2010) |

| SLC6A19/B0AT1 | Neutral amino acids | 1–12 mM (mouse) | 1S:1Na(S) | Broer et al. (2004) |

| SLC6A20/IMINO | Pro, OH-Pro, betaine | 130 µM–200 µM (rat/mouse) | 1S:2Na(S):1Cl(S) | Kowalczuk et al. (2005); Takanaga et al. (2005b) |

BCAA, branched chain amino acid; Mechanism: (S) symport (A) antiport; KM values are given for human isoforms unless indicated otherwise.

About half of the transporters in the SLC6 family co-transport their substrate(s) together with two Na+ ions and one Cl- ion (Table 2). The number of co-transported Na+ ions can, however, vary from 1 (NET, SERT, B0AT1, B0AT2, NTT4) to 3 (GlyT2, BGT1). Furthermore, chloride is not universally used as a co-transported ion (B0AT1, B0AT2, NTT4). SERT is unique in its use of K+ as the anti-ported ion, resulting in an overall electroneutral transport mechanism (Rudnick, 1998). Two examples illustrate the fine-tuning of transport mechanisms to physiological demands: GlyT1 uses the co-transport of two Na+ ions, while GlyT2 uses three Na+-ions (both together with Cl-) to accumulate glycine (Supplisson and Roux, 2002). As a result, the accumulative power of GlyT1 is less than that of GlyT2. GlyT1 is expressed in astrocytes in the cortex and is thought to allow a significant extracellular glycine concentration, enough to co-activate neighbouring NMDA receptors through the glycine site. Small concentration changes of the co-transported ions or of the membrane potential could thus result in glycine release or removal, thereby modulating glutamatergic neurotransmission. GlyT2, by contrast, is expressed in glycinergic neurons, allowing optimal removal of the neurotransmitter from the synaptic cleft, leaving only traces of extracellular glycine. The second example is the occurrence of channel-like properties in monoamine transporters. Due to the high affinity of these transporters for their substrates, turnover is generally slow. Channel-like properties may allow an increased transport rate when neurotransmitter concentrations are elevated (Galli et al., 1996; DeFelice and Goswami, 2007). The removal of neurotransmitter is ensured by metabolic inactivation or sequestration into synaptic vesicles. Inadvertently, the channel-like mechanism is triggered by amphetamine binding in the case of the DAT (Sitte et al., 1998; Kahlig et al., 2005), which then results in release of the neurotransmitter, explaining the pharmacological effects of amphetamine (Robertson et al., 2009; Leviel, 2011). A similar mechanism underlies 5-HT release by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or ‘Ecstasy’) (Rudnick and Wall, 1992). Ion channel-like features triggered by substrates and drugs are particularly obvious in SERT, as its transport mechanism is electroneutral and any currents observed are caused by uncoupled movements of ions (Mager et al., 1994).

Pharmacology of SLC6 transporters

The pharmacology of the SLC6 family has been developed to different extents (Table 3) (Gether et al., 2006; Iversen, 2006; Kristensen et al., 2011). Due to their role as drug targets, a wide variety of inhibitors and synthetic substrates are available for monoamine transporters, whereas GABA and glycine transporter pharmacology is less well developed. All other transporters in the family remain largely unexplored (Table 4).

Table 3.

Inhibitors of SLC6 transporters

| Transporter | Inhibitor | Ki | Application | Selectivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC6A1/GAT1 | Tiagabine | 110 nM (h) | Seizures, neuropathic pain | GAT1>>>GAT2, GAT3, BGT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) |

| NNC-711 | 1.4 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT1>>>GAT2, GAT3, BGT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| SKF89976A | 130 nM (h) | Research tool | GAT1>>>GAT2, GAT3, BGT1 | Dhar et al. (1994) | |

| CI-966 | 260 nM (h) | Research tool | GAT1>>>GAT2, GAT3, BGT1 | Dhar et al. (1994) | |

| Nipecotic acid | 19 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT1>GAT3>GAT2>BGT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| Guvacine | 15 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT1>GAT3>GAT2,BGT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| (R)-EF1502 | 8.9 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT1>GAT2,BGT1>GAT3 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| THPO | 1300 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT1=GAT2=GAT3=BGT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| SLC6A2/NET | Amphetamine | 70 nM (h) | Drug | NET>DAT>>SERT | Han and Gu (2006) |

| Nisoxetine | 5.3 nM (h) | Ligand for quantification | NET>>SERT=DAT | Eshleman et al. (1999) | |

| Talopram | 8.9 nM (h) | Research tool | NET>>SERT>>DAT | Andersen et al. (2011) | |

| Talsupram | 2.5 nM (h) | Research tool | NET>>SERT>DAT | McConathy et al. (2004) | |

| Reboxetine | 3 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | NET>>SERT>>DAT | Andersen et al. (2009) | |

| Atomoxetine | 5 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | NET>>SERT>DAT | Andersen et al. (2009) | |

| χ-MrIA | 1260 nM (h) | Research tool | NET>>>SERT=DAT | Sharpe et al. (2001) | |

| Nomifesine | 16 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | NET>DAT>>SERT | Tatsumi et al. (1997) | |

| Mazindole | 3.3 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | NET>DAT>SERT | Eshleman et al. (1999) | |

| MDMA | 1190 nM (h) | Drug of abuse | NET=SERT>DAT | Han and Gu (2006) | |

| Desipramine | 0.8 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | NET>SERT>>DAT | Tatsumi et al. (1997) | |

| Methylphenidate (Ritalin) | 34 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | NET>DAT>>SERT | Markowitz et al. (2006) | |

| SLC6A3/DAT | Benztropine | 42 nM (h) | Research tool | DAT>NET>>>SERT | Eshleman et al. (1999) |

| JHW 007 | 24.6 nM (r) | Research tool | DAT>>SERT=NET | Agoston et al. (1997) | |

| GBR12935 | 22.4 nM (h) | Ligand for quantification | DAT>NET>SERT | Eshleman et al. (1999) | |

| RTI-55 (β-CIT) | 1.3 nM (rt) | Ligand for quantification | DAT=SERT>NET | Carroll et al. (1995) | |

| Cocaine | 278 nM (h) | Drug of abuse | DAT=SERT=NET | Eshleman et al. (1999) | |

| CFT | 27.2 nM (h) | Research tool | DAT=NET>SERT | Eshleman et al. (1999) | |

| Bupropion | 520 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | DAT>>SERT>NET | Tatsumi et al. (1997) | |

| Modafinil | 4800 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | DAT>NET>SERT | Zolkowska et al. (2009) | |

| SLC6A4/SERT | Fluvoxamine | 2 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | SERT>>DAT>NET | Tatsumi et al. (1997) |

| Escitalopram | 2.5 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | SERT>>>NET>>DAT | Owens et al. (2001) | |

| DASB | 1.1 nM (h) | PET ligand | SERT>>>NET=DAT | Wilson et al. (2000) | |

| Sertraline | 0.13 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | SERT>>NET>DAT | Tatsumi et al. (1997) | |

| Paroxetine | 0.13 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | SERT>>>NET>DAT | Tatsumi et al. (1997) | |

| Fluoxetine | 0.8 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | SERT>>NET>DAT | Tatsumi et al. (1997) | |

| Desvenlafaxine | 40 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | SERT>NET>>DAT | Deecher et al. (2006) | |

| Imipramine | 1.4 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | SERT>>NET>>DAT | Tatsumi et al. (1997) | |

| Duloxetine | 0.8 nM (h) | Therapeutic drug | SERT>NET>>DAT | Bymaster et al. (2001) | |

| SLC6A5/GlyT2 | ORG 25543 | 16 nM (h) | Research tool | GlyT2>GlyT1 | Caulfield et al. (2001) |

| 5,5-Diaryl-2-amino-4-pentenoate | 300 nM (h) | Research tool | GlyT2>GlyT1 | Isaac et al. (2001) | |

| N-Arachidonylglycine | 3 µM (h) | Research tool | GlyT2>GlyT1 | Wiles et al. (2006) | |

| SLC6A6/TauT | Diaminopropionic acid | 100 µM (m) | Research tool | Liu et al. (1992a) | |

| Hypotaurine | 10 µM (m) | Research tool | Liu et al. (1992a) | ||

| β-guanidino-ethanesulfonic acid | 50 µM (m) | Research tool | Liu et al. (1992a) | ||

| β-alanine | 100 µM (r) | Research tool | TauT=GAT3 | Smith et al. (1992b) | |

| SLC6A7/PROT | Leu-Enkephalin | 2.1 µM (r) | Research tool | Fremeau et al. (1996) | |

| GGFL | 0.3 µM (r) | Research tool | Fremeau et al. (1996) | ||

| Benztropin | 0.75 µM (h) | Research tool | Yu et al. (2009) | ||

| LP-403182 | 0.11 µM (h) | Research tool | Yu et al. (2009) | ||

| SLC6A8/CT1 | Guanidinopropionate | n.d. | Research tool | Guimbal and Kilimann (1994) | |

| Guanidinobutyrate | n.d. | Research tool | Guimbal and Kilimann (1994) | ||

| SLC6A9/GlyT1 | Sarcosine | 55 µM (r) | Research tool | GlyT1>>GlyT2 | Mallorga et al. (2003) |

| NFPS (ALX 5407) | 3 nM (r) | Research tool | GlyT1>>>GlyT2 | Mallorga et al. (2003) | |

| ORG 24598 | 32 nM (r) | Research tool | GlyT1>>>GlyT2 | Mallorga et al. (2003) | |

| LY2365109 | 16 nM (h) | Research tool | GlyT1>>>GlyT2 | Perry et al. (2008) | |

| CP-802,079 | 16 nM (h) | Research tool | GlyT1>>>GlyT2 | Martina et al. (2004) | |

| Lu AA20465 | 150 nM (h) | Research tool | GlyT1>>>GlyT2 | Smith et al. (2004) | |

| SSR130800 | 1.9 nM (h) | Research tool | GlyT1>>>GlyT2 | Boulay et al. (2008) | |

| SLC6A10 | n.a. | ||||

| SLC6A11/GAT3 | β-alanine | 36 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT3=GAT2>BGT1>GAT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) |

| (S)-SNAP-5114 | 50 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT3=GAT2>BGT1>GAT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| THPO | 2200 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT1=GAT2= GAT3=BGT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| SLC6A12/BGT1 | Betaine | 590 µM (h) | Research tool | BGT1>GAT2>GAT1,GAT3 | Kvist et al. (2009) |

| NNC 05–2090 | 1.4 µM (m) | Research tool | BGT1>GAT1,GAT3,GAT2 | Thomsen et al. (1997) | |

| THPO | 2100 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT1=GAT2=GAT3=BGT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| SLC6A13/GAT2 | β-alanine | 42 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT2=GAT3>BGT1>GAT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) |

| (S)-SNAP-5114 | 130 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT2=GAT3>BGT1>GAT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| THPO | 1500 µM (h) | Research tool | GAT1=GAT2=GAT3=BGT1 | Kvist et al. (2009) | |

| SLC6A14/ATB0,+ | 1-Methyltryptophan | 250 µM (m) | Research tool | Hatanaka et al. (2001) | |

| NG-monomethyl-L-arginine (L-NMMA) | 0.77 mM (m) | Research tool | Hatanaka et al. (2001) | ||

| NG-nitro-L-arginine (L-NNA) | 0.56 mM (m) | Research tool | Hatanaka et al. (2001) | ||

| SLC6A15/B0AT2 | Pipecolic acid | 0.9 mM (m) | Research tool | Broer et al. (2006) | |

| SLC6A16/NTT5 | unknown | ||||

| SLC6A17/NTT4 | unknown | ||||

| SLC6A18/B0AT3 | unknown | ||||

| SLC6A19/B0AT1 | unknown | ||||

| SLC6A20/IMINO | Sarcosine | 3.2 mM (m) | Research tool | Inhibits GlyT1 | Kowalczuk et al. (2005) |

| Pipecolic acid | 0.09 mM (m) | Research tool | IMINO>B0AT2 | Kowalczuk et al. (2005) | |

| MeAIB | 0.78 mM (m) | Research tool | Kowalczuk et al. (2005) | ||

| Betaine | 0.2 mM (m) | Research tool | Inhibits BGT1 | Kowalczuk et al. (2005) |

Selectivity: >less than 10-fold, >>10- to 100-fold, >>>100- to 1000-fold.

Reported are Ki values for heterologously expressed transporters unless indicated otherwise. The species is indicated (h, human; r, rat; m, mouse).

Rt, rat tissue, n.a., not applicable, n.d., not determined.

Table 4.

SLC6 transporters as drug targets

| Transporter | Drug/Drug class | Indication | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAT1 | Tiagabine | Epilepsy, neuropathic pain | |

| NET | NRI | ADHD, depression | |

| NDRI | ADHD, depression, obesity | ||

| SNRI | Depression, neuropathic pain | ||

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Depression, neuropathic pain | ||

| DAT | NDRI | ADHD, depression, obesity | |

| SERT | SSRI | Depression, anxiety, OCD | |

| SNRI | Depression, neuropathic pain | ||

| TauT | Taurine | No specific condition | Dietary Supplement |

| CT1 | Creatine | Athletic sport | Dietary Supplement |

| Creatine deficiency syndromes |

NRI, noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; NDRI noradrenaline/dopamine reuptake inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin/noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

The first generation of monoamine transporter drugs were identified in the 1950s and included the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), such as imipramine and desimipramine, that exert their action on SERT and/or NET (Moltzen and Bang-Andersen, 2006). Because of side effects caused by additional affinity for several different receptors and for cardiac sodium channels (Gillman, 2007), these antidepressants have been largely superseded by compounds devoid of ectopic binding. These include compounds targeting solely SERT ('selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitors', SSRIs) such as escitalopram, fluoxetine and paroxetine (Wong and Bymaster, 1995), compounds targeting solely NET ('selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors', NRIs), such as reboxetine (Andersen et al., 2009) and compounds targeting both NET and SERT ('dual uptake inhibitors' or ‘5-HT/ noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors’, SNRIs) including venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine and duloxetine (Wong and Bymaster, 2002). Notably, these newer classes of uptake inhibitors have not only shown efficacy in treatment of major depression but also demonstrated their usefulness in anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and eating disorders. Interestingly, sibutramine, which has been used as an appetite suppressant, might act as ‘a triple uptake inhibitor’ because it is rapidly metabolized to its desmethyl and didesmethyl congeners that display high affinity for all three monoamine transporters (Glick et al., 2000). More recently, specific triple uptake inhibitors are being developed (Bettati et al., 2010).

The monoamine transporters are also target for illicit and widely abused drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines. Cocaine is a rapidly acting non-selective high-affinity inhibitor of all three monoamine transporters (Eshleman et al., 1999). Nonetheless, studies on DAT knock-out mice and knock-in mice expressing a cocaine-insensitive DAT strongly suggest that the stimulatory properties of cocaine are the result of its interaction with DAT (Giros et al., 1996; Chen et al., 2006). Several analogues of cocaine have been developed over the years with both higher affinity and improved selectivity for the different monoamine transporters (Table 3). These compounds have served and still serve as important tool compounds; however, some are also considered candidates for treating cocaine addiction (Newman and Kulkarni, 2002; Dutta et al., 2003; Loland et al., 2008). For example, the benztropine analogue JHW007 does not possess the same strong stimulatory properties as cocaine and was found to antagonize the effect of cocaine on behaviour in rats (Desai et al., 2005). Possibly, this is the result of a much slower onset and longer duration of action than that of cocaine, an effect that may be caused by JHW 007's ability to stabilize a different more closed conformation of the transporter, compared with cocaine (Loland et al., 2008). The compound modafinil, which is used to treat narcolepsy, is also a DAT inhibitor with weaker action than cocaine and little potential for abuse (Zolkowska et al., 2009). Accordingly, modafinil might also be a promising therapeutic agent for cocaine addiction (Dackis et al., 2005; Hart et al., 2008; Minzenberg and Carter, 2008).

Some drugs targeting the monoamine transporters are not simple inhibitors but are transporter substrates (Sitte et al., 1998; Gether et al., 2006). They include amphetamine, metamphetamine and MDMA, compounds that are capable of promoting reverse transport of the endogenous substrate and thus monoamine release via the monoamine transporters to the extracellular environment (Fuller et al., 1988; Sulzer et al., 2005). Amphetamine and metamphetamine act primarily on DAT and NET, whereas SERT and NET are targets for MDMA (Green et al., 2003; Sulzer et al., 2005). Amphetamine-induced reverse transport is a complex process that is not only the simple result of facilitated exchange (Pifl et al., 1999; Scholze et al., 2002; Leviel, 2011) but is also likely to involve a channel-like mode of the transporter (Kahlig et al., 2005). The underlying mechanism appears to require binding of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIα (CaMKIIα) to the distal C-terminus of DAT (Fog et al., 2006). This binding facilitates phosphorylation of N-terminal serine residues that in turn changes the transporter from an ‘unwilling’ to a ‘willing’ state for reverse transport (Khoshbouei et al., 2004; Fog et al., 2006). Binding of syntaxin1a to DAT might also be critical for the process (Binda et al., 2008). Methylphenidate is a derivative of amphetamine that is widely used in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This compound differs from amphetamine in not having dopamine-releasing properties (Sulzer et al., 2005). It acts, compared with cocaine, as a relatively weak DAT and NET inhibitor, and as a consequence, this compound can also have a potential in treating cocaine abuse (Goldstein et al., 2010). Buproprion is another amphetamine derivative acting primarily as an inhibitor at NET and DAT (Dwoskin et al., 2006). It is registered as an atypical antidepressant and as smoking cessation agent. Moreover, buproprion has a modest weight-reducing effect that appears to be enhanced when administered in combination with an opioid receptor antagonist (Dwoskin et al., 2006).

The GAT-1-specific inhibitor tiagabine is used to treat seizures and neuropathic pain and is the only GABA transporter inhibitor currently registered as a therapeutic agent (Clausen et al., 2006). Tiagabine is also one of the only GABA inhibitors showing selectivity among the GABA transporters, although several inhibitors have been developed. In general, GABA transporter inhibitors display rather low affinity and selectivity for the transporters; and, thus, there is a strong need for improved inhibitors of this subgroup of SLC6 transporters (Table 3). Such new compounds might not only serve as investigatory tool but also as new therapeutic agents; for example, there is evidence that BGT-1 is an alternative target to GAT-1 for treatment of epilepsy (Madsen et al., 2009).

In recent years, an increasing number of inhibitors of the two glycine transporters GlyT1 and GlyT2 have been identified (Table 3). Development of these inhibitors has been motivated by data indicating that blocking synaptic glycine uptake is beneficial in psychotic disease and neuropathic pain (Lechner, 2006; Dohi et al., 2009). The inhibitor N-methyl glycine (sarcosine) was the basis for several potent inhibitors, for instance (R)-NPTS and ORG 24598 (Mallorga et al., 2003). Non-sarcosine GlyT1 inhibitors include LY2365109 (Perry et al., 2008), CP-802 079 (Martina et al., 2004), Lu AA20465 (Smith et al., 2004) and SSR130800 (Boulay et al., 2008). Overall, fewer inhibitors are known for GlyT2. The competitive and selective inhibitor ORG 25543 was discovered first (Caulfield et al., 2001) and followed by other classes of compounds (Isaac et al., 2001).

The efficacy of inhibitors is also affected by functional redundancy among neurotransmitter transporters. As a result, use of a specific inhibitor of one transporter may have a result different from that using a broadly specific inhibitor. GAT1 is the most abundant GABA transporter in the cortex. GAT-1-deficient mice show typical signs of increased inhibitory neuronal activity, such as reduced locomotor and general activity, abnormal gait and constant tremor, but have a normal life span and reproduce normally (Chiu et al., 2005). This suggests that other GABA transporters can replace GAT-1 activity or that other components of GABA signalling adapt to reduced neurotransmitter clearance (Bragina et al., 2008). Similarly, there is overlap between the function of noradrenaline and dopamine transporters. For example, there is evidence that NET is responsible for clearance of extracellular dopamine in the prefrontal cortex (see Carboni and Silvagni, 2004). By contrast, there appears to be little overlap between the function of glycine transporters GlyT1 and GlyT2, due to differential localization (Eulenburg et al., 2005). The amino acid transporters NTT4 and B°AT2 seem to have a very similar distribution in the brain, providing redundancy for the uptake of essential amino acids into neurons (Masson et al., 1996).

Pathology and clinical significance

Members of the SLC6 family are believed to play a role in a variety of disease states. In a number of cases, mutations in a transporter are associated with an inherited Mendelian disorder. In some cases, mutations contribute to more complex multifactorial diseases and in others disorders of unknown aetiology can be treated by inhibitors of SLC6 transporters. Table 5 provides an overview of disease states associated with the SLC6 family.

Table 5.

Disease states associated with SLC6 family transporters

| Transporter | Disease state | Inheritance | Variation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NET | ADHD | Complex | Promoter variants | Kim et al. (2006) |

| Depression | Complex | Hahn and Blakely (2007) | ||

| Orthostatic intolerance | Complex | A457P | Shannon et al. (2000) | |

| Blood pressure | Complex | Halushka et al. (1999) | ||

| SERT | Autism/OCD | Complex | VNTR, SNPs | Cook et al. (1997); Sutcliffe et al. (2005) |

| OCD | Complex | I425V | ||

| Anxiety/Depression | Complex | VNTR | Ozaki et al. (2003) | |

| VNTR | Lesch et al. (1996) | |||

| L255M | ||||

| DAT | ADHD | Complex | 3′ VNTR | Hahn and Blakely (2007) |

| Bipolar | Complex | Several SNPs | Grunhage et al. (2000) | |

| Tourette syndrome | Complex | 3′ VNTR | Tarnok et al. (2007) | |

| GlyT2 | Hyperekplexia | Mendelian | Various mutants | Rees et al. (2006) |

| Creatine | X-linked mental retardation | Mendelian | Various mutants | Salomons et al. (2001) |

| B0AT1 | Hartnup disorder | Mendelian | Various mutations | Kleta et al. (2004); Seow et al. (2004) |

| B0AT2 | Major depression | Complex | Downstream of the gene | Kohli et al. (2011) |

| IMINO | Iminoglycinuria | Mendelian | T199M | Broer et al. (2008) |

VNTR, Variable number of tandem repeats; a short nucleotide sequence organized into clusters of tandem repeats.

Creatine deficiency syndrome is a rare disorder caused by mutations in the creatine transporter CT1 (Salomons et al., 2001). It causes creatine deficiency in the brain resulting in mental retardation. Creatine is an important storage compound for high-energy phosphate bonds, which replenish ATP during times of high energy consumption (Wallimann et al., 2011). Mutations in the glycine transporter GlyT1 cause hyperekplexia, an exaggerated startle syndrome, resulting from increased inhibition in motor circuits (Harvey et al., 2008). Mutations in B0AT1 are associated with Hartnup disorder, an amino acid malabsorption syndrome, which can cause skin rash and ataxia in young individuals (Seow et al., 2004). Mutations in IMINO are associated with iminoglycinuria, a benign disorder affecting reabsorption of glycine and proline in the kidney (Broer et al., 2008).

The noradrenergic system plays an important role in depression, attention, vigilance, learning, memory and has been proposed to contribute to ADHD (Hahn and Blakely, 2007). It is also involved in blood pressure regulation through its role in the peripheral nervous system. DNA and protein variants of NET are associated with disorders of the noradrenergic system. An inactivating mutation in NET is associated with orthostatic intolerance (Shannon et al., 2000; Hahn et al., 2003), and another variant was identified by analysing candidate genes for blood-pressure homeostasis (Halushka et al., 1999). Interestingly, this variant has also been associated with major depression (Haenisch et al., 2009). However, NET is only one component in the noradrenergic systems, and other variations in receptors, synthesizing and degrading enzymes, and also in environmental factors, all can contribute to the phenotype of these disorders.

The dopaminergic system is an important mediator of motor function, cognition, mood, reward and addiction. The dopaminergic system is associated with a variety of disorders, such as ADHD, bipolar disorder, autism, schizophrenia, drug abuse, Parkinson's disease and Tourette's syndrome (Hahn and Blakely, 2007). Of interest, DAT knock-out mice display a behavioural phenotype that in part resembles symptoms seen in ADHD patients (Gainetdinov and Caron, 2000) and in agreement a single point mutation (Ala559Val) has been identified in patients with ADHD (Mazei-Robison et al., 2005). Furthermore, two inactivating mutations in DAT have been linked to the rare autosomal-recessive disease, infantile parkinsonism-dystonia (Kurian et al., 2009).

5-HT plays a role in mood, aggression, response to alcohol, appetite, sleep, cognition and sexual and motor activity. It is likely to contribute to a range of mental illnesses such as depression, suicide, anxiety, autism, OCD, eating disorders, schizophrenia and alcohol abuse (Hahn and Blakely, 2007). Indeed, many polymorphisms have been identified in SERT, including, for example, both rare protein variants in patients with various neuropsychiatric disorders and an intensively studied promoter variant (Hahn and Blakely, 2007). The general significance of the promoter variant (5HTTLPR) has been debated (Munafo et al., 2009; Risch et al., 2009). Nonetheless, several studies have linked the short ‘s’ allele to anxiety-related personality traits, increased risk for neuropsychiatric disorders, impulsive behaviour and impaired response to antidepressant treatment (Hahn and Blakely, 2007; Serretti et al., 2007; Homberg and Lesch, 2011). It has been proposed that these phenotypic traits in people carrying the ‘s’ allele are caused by hypervigilance and thereby supersensitivity to environmental cues. This supersensitivity might cause enhanced emotional responses that could contribute to development of pathological conditions (Homberg and Lesch, 2011).

Recently, a genome-wide association study has suggested B°AT2 as a candidate gene involved in major depression (Kohli et al., 2011). It should be noted that SNPs associated with major depression are significantly downstream of the gene, and a more causal relation needs to be established.

The role of taurine transport in human physiology is still ill understood. Taurine transporter deficient mice show a variety of pathological features, such as subtle derangements of renal osmoregulation, changes in neuroreceptor expression and loss of long-term potentiation in the striatum (Warskulat et al., 2007). They develop clinically relevant age-dependent disorders, for example, visual, auditory and olfactory dysfunctions, non-specific hepatitis and liver fibrosis (Warskulat et al., 2004). It is thought that taurine is an important osmolyte for cells, but the relative vulnerability of cells to lack of taurine has yet to be assessed. No human disorder has been identified involving the taurine transporter.

Distribution

Members of the SLC6 family are found in a wide variety of tissues (Table 6). The neurotransmitter transporters are mainly found in the CNS. However, many neurotransmitters are also used as signalling molecules by peripheral neurons and chromaffin cells. The amino acid transporters are not only found in epithelial cells, mostly in the intestine and kidney, but also in brain, lung and testis. Taurine and creatine transporters are expressed widely. Apart from NTT4 (Parra et al., 2008) and PROT (Velaz-Faircloth et al., 1995), two amino acid transporters found in vesicular compartments in the brain, all other SLC6 family transporters are located primarily in the plasma membrane. Neurotransmitter transporters in the brain are either localized in the presynaptic membrane to recapture released neurotransmitters or are localized in astrocytes, which remove neurotransmitters and modulate neurotransmission by a variety of mechanisms. Monoamine transporters, for example, are found in the plasma membrane of the presynaptic neurons using the corresponding neurotransmitter. By contrast, the GlyT1 is expressed in astrocytes and its distribution correlates with that of the NMDA receptor (Smith et al., 1992a). As a result it is thought to modulate glutamatergic neurotransmission. During development, it is in addition important for removal of the inhibitory neurotransmitter glycine (Eulenburg et al., 2010). The glycine transporter GlyT2 is found mainly in neurons of the spinal cord, where it recaptures glycine released from inhibitory neurons (Liu et al., 1993a). The GABA transporter GAT-1 is found in inhibitory neurons throughout the cortex. GAT-2 is found in the leptomeninges surrounding the brain, while GAT-3 has been reported in astrocytes and neurons. The GABA-betaine transporter BGT-1 is also found in neurons but not in the presynaptic membrane. Amino acid transporters of the SLC6 family, such as B0AT1, B0AT3 and IMINO, are found in the apical membrane of epithelial cells in the kidney and intestine, where they remove amino acids from the lumen (Romeo et al., 2006; Vanslambrouck et al., 2010). In addition, there are two neutral amino acid transporters (NTT4 and B0AT2), which are found in neurons throughout the brain (Masson et al., 1996).

Table 6.

Tissue and cellular distribution of SLC6 family transporters

| Transporter | Endogenous substrate | Main organ | Other tissues | Subcellular |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLC6A1/GAT1 | GABA | brain | Bladder, liver, parathyroid | PM, presynaptic |

| SLC6A2/NET | noradrenaline | brain | Intestine, kidney, placenta, testis | PM, presynaptic |

| adrenal gland | ||||

| SLC6A3/DAT | dopamine | brain | thymus | PM, presynaptic |

| SLC6A4/SERT | 5-HT | brain | Bone, intestine, thymus | PM |

| SLC6A5/GlyT2 | glycine | spinal cord | Brain, eye | PM, presynaptic |

| SLC6A6/TauT | taurine | ubiquitous | PM | |

| SLC6A7/PROT | proline | brain | Vesicular | |

| SLC6A8/CT1 | creatine | ubiquitous | PM | |

| SLC6A9/GlyT1 | glycine | widely | PM | |

| SLC6A10 | pseudogene | n.a. | ||

| SLC6A11/GAT3 | GABA | brain | Eye, spinal cord | PM |

| SLC6A12/BGT1 | betaine, GABA | kidney | Brain, liver | PM |

| SLC6A13/GAT2 | GABA | kidney, liver | Brain, eye | PM |

| SLC6A14/ATB0,+ | Neutral and cationic amino acids | lung | Pituitary, colon, mammary gland | PM |

| SLC6A15/B0AT2 | BCAA, Met, Pro | brain | Eye, muscle, placenta | PM |

| SLC6A16/NTT5 | Unknown | testis | Blood, bone | unknown |

| SLC6A17/NTT4 | BCAA, Met, Pro, Ala, Gln | brain | Eye, pituitary, pancreas | Vesicular |

| SLC6A18/B0AT3 | Gly, Ala | kidney | PM | |

| SLC6A19/B0AT1 | Neutral amino acids | kidney, intestine | skin | PM |

| SLC6A20/SIT1 | Pro, OH-Pro, betaine | intestine | Brain, eye | PM |

BCAA, branched chain amino acid; PM, plasma membrane.

Regulation

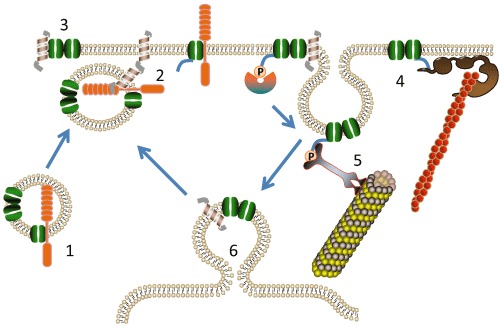

Many members of the SLC6 family are highly regulated, involving multiple protein–protein interactions. These can be direct interactions between the transporter and another protein or involve a post-translational modification such as phosphorylation (see, e.g., Ramamoorthy et al., 2011) or ubiquitination (Miranda and Sorkin, 2007) of a transporter, mostly at the N- or C-terminus, followed by recognition of the modified sequence by other proteins (Figure 2). In most cases, this results in changes of transporter localization, with changes of catalytic activity being less common (Apparsundaram et al., 2001; Zhu et al., 2005). Changes of transporter localization can occur in different ways: first, attachment of a protein can result in movement of the transporter from intracellular membranes to the cell surface; second, attachment of a protein can result in withdrawal of the transporter from the cell surface; third, attachment of a protein can result in stabilization and retention of the protein at the cell surface. Monoamine transporters in addition are regulated by substrate binding, which can affect phosphorylation and trafficking. A variety of SLC6 transporters undergo continuous constitutive internalization into endosomal compartments conceivably followed by recycling back to the plasma membrane (Torres et al., 2003; Melikian, 2004; Eriksen et al., 2010; Ramamoorthy et al., 2011). This process can be affected by activation of kinases, binding of substrate and interaction with other proteins (Figure 2). The number of studies demonstrating protein–protein interactions and protein phosphorylation are too numerous to be listed exhaustively. Instead, the reader is referred to recent reviews in this area (Melikian, 2004; Sitte et al., 2004; Torres, 2006; Eriksen et al., 2010; Ramamoorthy et al., 2011). A few examples serve to illustrate these different mechanisms; (i) Movement to the cell surface by protein–protein interactions. Two different mechanisms are observed, either transporters dimerize before exit from the endoplasmic reticulum can occur (Schmid et al., 2001; Farhan et al., 2006; Horschitz et al., 2008), or they need to associate with an accessory protein, such as collectrin or ACE2 (B°AT1 and B°AT3) (Danilczyk et al., 2006; Kowalczuk et al., 2008; Vanslambrouck et al., 2010). These mechanisms are not exclusive, because SERT, for instance, requires both dimerization and binding to the cargo protein SEC24C to reach the surface (Sucic et al., 2011). (ii) Withdrawal from the cell surface. Many neurotransmitter transporters are withdrawn from the surface into endosomal compartments after treatment of cells with agents that activate PKC (Ramamoorthy et al., 2011). In most cases, this is accompanied by increases in transporter phosphorylation on the amino-terminus or the carboxyl-terminus. However, mutagenesis of canonical phosphorylation sites in DAT did not affect down-regulation (Foster et al., 2002). It rather appears that PKC-mediated down-regulation requires sequestration of the transporters in specific membrane domains, such as lipid rafts (Jayanthi et al., 2004; Cremona et al., 2011). For DAT, PKC-mediated down-regulation might also depend on N-terminal ubiquitination (Miranda and Sorkin, 2007) and/or binding of the Ras-like GTPase, Rin, to an endocytic motif in the C-terminus (Navaroli et al., 2011). Whether similar mechanisms account for other SLC6 transporters and whether other kinds of adaptor proteins are required remains unclear. (iii) Stabilization of transporters in the membrane/synapse: Many SLC6 transporters contain a C-terminal PDZ (PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1 homology) binding sequence, enabling binding to ‘scaffolding’ proteins containing PDZ domains. As an example, the PDZ domain protein syntenin-1 binds the C-terminus of GlyT2, and mutation of the PDZ binding motif reduces synaptic localization of this transporter, suggesting that syntenin-1/ or another PDZ domain protein is involved in stabilizing the transporter at synaptic sites (Armsen et al., 2007). Of interest, DAT and NET both bind to PICK1 (protein interacting with C-kinase-1), and this interaction was suggested to play a role in synaptic targeting of DAT (Torres et al., 2001). However, later results have questioned this function, and the functional significance of the DAT/PICK1 interaction remains unsettled (Bjerggaard et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

Regulation of SLC6 transporters. Major mechanisms regulating transporter activity and localization are illustrated. In (1), in order to be trafficked to the cell surface, transporters (shown in green) often need to dimerize or associate with a trafficking subunit (orange). At (2), fusion of vesicles with the plasma membranes occurs through interaction of t-SNARE and v-SNARE proteins, shown as helices. Once in the cell membrane (3), a variety of neurotransmitter transporters interact with the t-SNARE protein syntaxin1A (helix) or with the trafficking subunit (orange). To stabilise localisation in the cell membrane (4), transporters can interact with scaffolding proteins, such as PDZ domain-binding proteins (shown as brown globular structures). These can anchor transporters to the cytoskeleton, shown as orange filaments. Internalization of transporters frequently starts with phosphorylation of the N-terminus or C-terminus of transporters and this phosphorylated form is recognized by adapter proteins (5), causing internalization and subsequent removal of the transporter to endosomal compartments (6). Internalization often occurs in specialized lipid domains, such as lipid rafts.

A notable but still poorly understood protein–protein interaction is the interaction of syntaxin1A with members of the SLC6 family. Syntaxin1A has been shown to interact with GAT1 (Beckman et al., 1998), DAT (Lee et al., 2004; Binda et al., 2008), NET (Sung et al., 2003), SERT (Quick, 2003), GlyT1 and GlyT2 (Quick, 2006). Syntaxin 1A is a t-SNARE protein, which resides in the plasma membrane and catalyses the fusion of synaptic and other vesicles with the plasma membrane. Syntaxin1A appears to interact directly with the N-terminus of several neurotransmitter transporters exerting a variety of effects. First, it seems to be important for movement of transporters from vesicular compartments to the plasma membrane (Geerlings et al., 2001) as shown by decreased trafficking of NET to the surface after partial proteolysis of syntaxin1A with botulinum toxin C1 (Sung et al., 2003). Second, as suggested for SERT, interaction of the transporter with syntaxin1A can reduce transport activity by interfering with an interaction between the N-terminus and intracellular loop 4 (Quick, 2003). Syntaxin1A also abolishes the transport-associated ion conductance in SERT (Quick, 2003). Finally, syntaxin1A binding can promote reverse transport of substrate such as, for example, amphetamine-induced efflux of dopamine in DAT (Binda et al., 2008). Taken together, while there is no question that syntaxin 1A affects neurotransmitter transporter activity in a variety of ways, the physiological rationalization of these processes is far from complete. Interestingly, collectrin, which traffics B0AT1 and B0AT3 to the membrane, is thought to interact with Snapin, another t-SNARE protein (Fukui et al., 2005).

Biochemistry

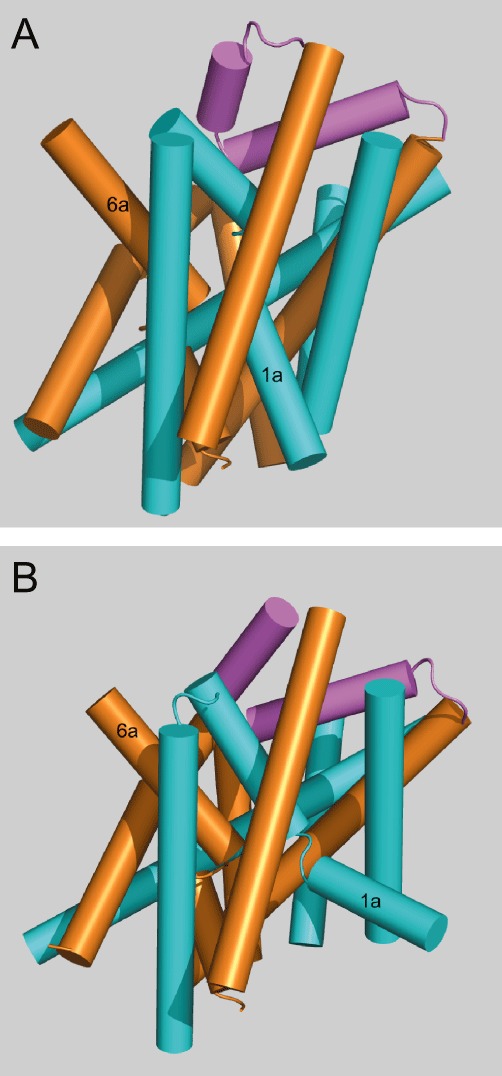

The structure of SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters has been probed intensively, using site-directed mutagenesis, alanine scanning, cysteine accessibility and other approaches (Kanner, 2006; Kristensen et al., 2011). The advent of the high-resolution structure of the bacterial homologue, the leucine transporter LeuT, however, has provided a quantum leap to our understanding of the SLC6 structure (Yamashita et al., 2005). Overall SLC6 transporters have 12 transmembrane helices, 10 of which constitute the core of the transporter. The additional two helices might be involved in transporter dimerization (Just et al., 2004). The first 10 helices are arranged in a pseudo-twofold symmetric pattern, named the 5 + 5 inverted repeat fold (Figure 3). The first five helices can be converted into the second five helices by a simple symmetry operation. Interestingly, the ‘5 + 5 inverted repeat’ of LeuT has been identified also in structures of other prokaryotic transporters, which belong to families that lack significant sequence identity to LeuT or other SLC6 transporters and, accordingly, were not expected to be structurally related (see Abramson and Wright, 2009; Forrest and Rudnick, 2009). Hence, the 5 + 5 inverted repeat fold observed in LeuT appears to characterize several families of secondary active transporters that are likely to operate via a conserved molecular mechanism (see Abramson and Wright, 2009; Forrest and Rudnick, 2009; Krishnamurthy et al., 2009; Forrest et al., 2011). Of particular interest are helices 1 and 6, which are unwound in the center allowing backbone contacts with Na+ ions and substrate (Table 7). Helix 1 and 6 are therefore subdivided into helix 1a/1b and helix 2a/2b. Using site-directed mutagenesis, Krishnamurthy and Gouaux (2012) were able to crystallise LeuT in a substrate-free outward-open and inward-open conformation, providing insight into the transport mechanism. It appears that helices 1,2,5,6 and 7 make significant moves during the transport cycle; while the remaining helices form a scaffold. In particular, helix 1a bends around the center opening up the cytosolic access. In the inward-open conformation, access from the outside is blocked by helices 1b and 6a and extracellular loop 4 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Structure of SLC6 family transporters. The structure of the prokaryotic leucine transporter LeuT is used as a template to generate homology structures of SLC6 transporters. In (A) the structure of LeuT is shown in the open-outside conformation (Protein database 3TT1) and in (B) as the open-inside conformation (Protein database 3TT3). Its structure is characterized by an inverted repeat of a group of five helices. Helices 1–5 are shown in blue and helices 6–10 in orange. Extracellular loop 4 is shown in magenta. Helices 11 and 12 are omitted for clarity. Note the significant movement of helix 1b to allow substrate access on the inside. Extracellular loop 4 blocks access from the outside in the open-inside conformation.

Table 7.

Residues involved in substrate binding in the SLC6 family

| Transporter | α-NH2 | α-NH2 | α-NH2 | α-NH2 | α-COOH | α-COOH | α-COOH | Side chain | Side chain | Side chain | Side chain | Side chain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LeuT | A22 | F253 | T254 | S256 | L25 | G26 | Y108 | V104 | F253 | F259 | S355 | I359 |

| (O) | (O) | (O) | (Oγ) | (N) | (N) | (OH) | ||||||

| GAT1 | [A] | [F] | [S] | [G] | L | G | Y | L | F | L | S | T |

| GAT2 | [I] | [F] | [S] | [A] | L | G | Y | L | F | L | S | C |

| GAT3 | [I] | [F] | [S] | [A] | L | G | Y | L | F | L | S | C |

| BGT1 | I | F | S | A | L | G | Y | L | F | Q | S | C |

| TauT | [F] | [F] | [S] | [A] | L | G | Y | L | F | L | S | E |

| CT1 | [A] | [F] | [S] | [A] | L | G | Y | C | F | L | S | G |

| NET | A | F | S | G | [L] | [A] | [Y] | V | F | F | S | G |

| DAT | A | C | S | G | [L] | [A] | [Y] | V | C | F | S | G |

| SERT | A | F | S | G | [L] | [G] | [Y] | I | F | F | S | G |

| GlyT1 | A | F | S | A | L | G | Y | I | F | W | T | L |

| GlyT2 | A | F | S | S | L | G | Y | I | F | W | T | T |

| B0AT3 | A | F | S | S | L | G | Y | I | F | F | T | T |

| PROT | C | F | S | G | L | G | Y | V | F | F | S | F |

| IMINO | A | F | S | G | L | G | Y | L | F | F | S | N |

| NTT4 | S | F | A | G | L | G | Y | V | F | F | S | T |

| NTT5 | S | L | N | G | P | S | F | L | L | L | S | I |

| ATB0,+ | A | F | S | S | L | G | Y | V | F | W | S | S |

| B0AT1 | S | F | S | S | L | G | Y | V | F | F | S | N |

| B0AT2 | C | F | A | G | L | G | Y | V | F | F | S | T |

Alignment of corresponding residues in the peptide sequences of SLC6 family transporters with critical residues in the high-resolution structure of LeuT (Yamashita et al., 2005). The first line indicates the interaction with the substrate molecule (α-NH2, α-amino group; α-COOH, α-carboxy group; side chain, side chain of substrate). GABA, taurine and creatine do not have α-amino groups; while monoamines do not have α-carboxy group. The corresponding residues are listed in brackets. Atoms involved in binding are given in parentheses.

All SLC6 family members have a high-affinity substrate binding site in the centre of the membrane, called the S1 site. In the initial LeuT structure, which was captured in an occluded outside-facing conformation (Yamashita et al., 2005), access to the S1 site from the extracellular side is prevented by a network of interactions extracellular to S1 that is generated by side chains from TM1, TM3, TM6 and TM10. This includes a highly conserved Arg in TM1 (Arg30 in LeuT) that interacts via a pair of water molecules with an Asp in TM10 (Asp404 in LeuT) (Yamashita et al., 2005). Access to S1 from the intracellular medium is obstructed by a large layer of protein intracellular to S1 that contains a network of interactions formed primarily by residues at the cytoplasmic ends of TM1, TM6 and TM8 (Yamashita et al., 2005). A highly conserved key residue is Tyr268 (LeuT numbering) that by forming a cation–π interaction with Arg5 in the N-terminus just below TM1 stabilizes a salt bridge between the arginine and Asp369 at the bottom of TM8 (Yamashita et al., 2005). Together, these external and internal networks are believed to form dynamic gates that sequentially allow access to the substrate binding site from the extracellular and intracellular environments, respectively, during the transport cycle.

It is assumed that substrate binding together with Na+ leads to conformational changes that close the external gate and occlude the substrate. In the case of LeuT, two Na+ ions bind together with the substrate in the active site. Recent site-directed spin labelling and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) analysis on purified LeuT demonstrated the Na+-dependent formation of a dynamic outward-facing intermediate that exposes the primary substrate binding site and the conformational changes that occlude this binding site upon subsequent binding of leucine (Claxton et al., 2010). The free energy of the new closed conformation is such that a larger conformational change can now occur fairly easily (by thermal movement), leading to the open-inside structure with access to the cytosol. In the last step, the gate on the inside opens allowing the substrate to be released. Notable is the bending of helix 1a, which provides access from the cytosol in the open-inside structure. This latter event might be triggered by binding of a second substrate to the outer vestibule in LeuT; hence, steered molecular dynamics have suggested the existence of a second substrate binding site (S2) in the vestibule extracellular to the primary binding site (S1) (Shi et al., 2008). The existence of this S2 site has been further supported by single molecule FRET studies of conformational changes in the LeuT (Zhao et al., 2011). However, the existence and role of this binding site is controversial, and other sets of data have supported the presence of only one substrate binding site in the LeuT structure (Piscitelli et al., 2010). The structural basis of transport-associated conductances also remains unclear but appears to be in equilibrium with the inward facing conformation in the case of the SERT (Schicker et al., 2012). It is tempting to speculate that movements of extracellular loop 4 could allow formation of a continuous, water-accessible, pathway through the transporter.

In the context of the transport mechanism of the SLC6 family, chloride co-transport is another important feature. A plausible chloride binding site has been identified in chloride-dependent members of the SLC6 family (Forrest et al., 2007; Zomot et al., 2007). In Cl--independent members of the family, such as LeuT and Tyt1 (another prokaryotic transporter), the site is occupied by a negatively charged glutamate residue. In Tyt1, substrate transport measured after reconstitution into liposomes was stimulated by an inversely oriented pH gradient, and correspondingly, mutation of Ser331 in the Cl- binding site of GAT1 to glutamate conveyed pH dependency to this transporter. The data suggest that in Cl- independent members of the family, a proton may bind and unbind during the transport cycle and thus be counter-transported by a Na+/substrate–coupled H+ anti-port mechanism, possibly to facilitate the return step of the ‘empty’ transporter. This ensures a charge balance among the SLC6 transporters with similar mechanistic features but different molecular solutions (Zhao et al., 2010).

The availability of the LeuT structures also provides relevant clues for the pharmacology of the SLC6 transporters. In LeuT, the substrate binding pocket is lined by residues from helices 1, 3, 6 and 8 (Table 7). The pocket has two regions: first, unwound segments of helices 1 and 6 form backbone contacts with the α-amino and α-carboxyl group of the substrate; second a hydrophobic pocket is formed by aliphatic side chains from TM1, TM3 and TM6 (Tyr108, Phe253, Ser356, Phe259, Ser355 and Ile359) (Yamashita et al., 2005). Functional studies and homology modelling suggests that the equivalent residues in the mammalian SLC6 family form the binding sites for its substrates (Beuming et al., 2006; Rudnick, 2006; Henry et al., 2007). An overview of the equivalent residues is shown in Table 7. Interestingly, LeuT has been crystallized also together with TCAs as well as with two SSRIs, fluoxetine and sertraline, for which LeuT displays low affinity. The structures showed a binding site for TCAs and SSRIs in the LeuT, located in the extracellular vestibule (S2) (Singh et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2007; 2009). On the basis of these observations and mutagenesis of the corresponding site in SERT, it was proposed that the high-affinity binding site of TCAs and SSRIs is also located at the putative S2 site in SERT (Zhou et al., 2007; 2009). However, other studies have suggested that both SSRIs (S-CIT, fluoxetine and sertraline) and TCAs (CMI, imipramine, and amitriptyline) are classical competitive inhibitors and that their primary, high-affinity, binding site is located in the substrate binding pocket (S1) (Barker et al., 1998; Henry et al., 2006; Andersen et al., 2009; Sarker et al., 2010; Sinning et al., 2010). Similarly, there is strong evidence that DAT inhibitors such as cocaine and benztropines have their high-affinity binding site in the central substrate binding cavity (Beuming et al., 2008; Bisgaard et al., 2011).

Conclusion

Transporters of the SLC6 family are involved in a wide variety of pathological conditions. The structure of the bacterial transporter LeuT allows the generation of homology models, which will help in the design of new inhibitors, targeting specific SLC6 transporters. The pharmacology of the monoamine transporters is highly developed, but the biomedical relevance of other transporters in this family is less well explored.

Glossary

- ADHD

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- MDMA

3,4-methylenedioxymetamphetamine

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NSS

neurotransmitter sodium symporters

- OCD

obsessive-compulsive disorder

- PDZ

PSD-95/Discs-large/ZO-1

- SSRI

selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitors

- SNRI

5-HT/noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors

- TCA

tricyclic antidepressants

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- Abramson J, Wright EM. Structure and function of Na(+)-symporters with inverted repeats. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agoston GE, Wu JH, Izenwasser S, George C, Katz J, Kline RH, et al. Novel N-substituted 3 alpha-[bis(4′-fluorophenyl)methoxy]tropane analogues: selective ligands for the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 1997;40:4329–4339. doi: 10.1021/jm970525a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J, Kristensen AS, Bang-Andersen B, Stromgaard K. Recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of antidepressant drugs with serotonin and norepinephrine transporters. Chem Commun (Camb) 2009:3677–3692. doi: 10.1039/b903035m. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J, Stuhr-Hansen N, Zachariassen L, Toubro S, Hansen SM, Eildal JN, et al. Molecular determinants for selective recognition of antidepressants in the human serotonin and norepinephrine transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12137–12142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103060108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apparsundaram S, Sung U, Price RD, Blakely RD. Trafficking-dependent and -independent pathways of neurotransmitter transporter regulation differentially involving p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase revealed in studies of insulin modulation of norepinephrine transport in SK-N-SH cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:666–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragon C, Lopez-Corcuera B. Glycine transporters: crucial roles of pharmacological interest revealed by gene deletion. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsen W, Himmel B, Betz H, Eulenburg V. The C-terminal PDZ-ligand motif of the neuronal glycine transporter GlyT2 is required for efficient synaptic localization. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;36:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker EL, Perlman MA, Adkins EM, Houlihan WJ, Pristupa ZB, Niznik HB, et al. High affinity recognition of serotonin transporter antagonists defined by species-scanning mutagenesis. An aromatic residue in transmembrane domain I dictates species-selective recognition of citalopram and mazindol. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19459–19468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman ML, Bernstein EM, Quick MW. Protein kinase C regulates the interaction between a GABA transporter and syntaxin 1A. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6103–6112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06103.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettati M, Cavanni P, Di Fabio R, Oliosi B, Perini O, Scheid G, et al. Oxa-azaspiro derivatives: a novel class of triple re-uptake inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2010;5:361–366. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuming T, Shi L, Javitch JA, Weinstein H. A comprehensive structure-based alignment of prokaryotic and eukaryotic neurotransmitter/Na+ symporters (NSS) aids in the use of the LeuT structure to probe NSS structure and function. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1630–1642. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuming T, Kniazeff J, Bergmann ML, Shi L, Gracia L, Raniszewska K, et al. The binding sites for cocaine and dopamine in the dopamine transporter overlap. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:780–789. doi: 10.1038/nn.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda F, Dipace C, Bowton E, Robertson SD, Lute BJ, Fog JU, et al. Syntaxin 1A interaction with the dopamine transporter promotes amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1101–1108. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgaard H, Larsen MA, Mazier S, Beuming T, Newman AH, Weinstein H, et al. The binding sites for benztropines and dopamine in the dopamine transporter overlap. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerggaard C, Fog JU, Hastrup H, Madsen K, Loland CJ, Javitch JA, et al. Surface targeting of the dopamine transporter involves discrete epitopes in the distal C terminus but does not require canonical PDZ domain interactions. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7024–7036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1863-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakely RD, Berson HE, Fremeau RT, Jr, Caron MG, Peek MM, Prince HK, et al. Cloning and expression of a functional serotonin transporter from rat brain. Nature. 1991;354:66–70. doi: 10.1038/354066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden LA, Smith KE, Hartig PR, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL. Molecular heterogeneity of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transport system. Cloning of two novel high affinity GABA transporters from rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21098–21104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden LA, Dhar TG, Smith KE, Branchek TA, Gluchowski C, Weinshank RL. Cloning of the human homologue of the GABA transporter GAT-3 and identification of a novel inhibitor with selectivity for this site. Receptors Channels. 1994;2:207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden LA, Smith KE, Gustafson EL, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL. Cloning and expression of a betaine/GABA transporter from human brain. J Neurochem. 1995;64:977–984. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64030977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Pichat P, Dargazanli G, Estenne-Bouhtou G, Terranova JP, Rogacki N, et al. Characterization of SSR103800, a selective inhibitor of the glycine transporter-1 in models predictive of therapeutic activity in schizophrenia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;91:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragina L, Marchionni I, Omrani A, Cozzi A, Pellegrini-Giampietro DE, Cherubini E, et al. GAT-1 regulates both tonic and phasic GABA(A) receptor-mediated inhibition in the cerebral cortex. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1781–1793. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broer A, Klingel K, Kowalczuk S, Rasko JE, Cavanaugh J, Broer S. Molecular cloning of mouse amino acid transport system B0, a neutral amino acid transporter related to Hartnup disorder. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24467–24476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broer A, Tietze N, Kowalczuk S, Chubb S, Munzinger M, Bak LK, et al. The orphan transporter v7-3 (slc6a15) is a Na+-dependent neutral amino acid transporter (B0AT2) Biochem J. 2006;393:421–430. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broer S. The SLC6 orphans are forming a family of amino acid transporters. Neurochem Int. 2006;48:559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broer S. Apical transporters for neutral amino acids: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:95–103. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00045.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broer S, Bailey CG, Kowalczuk S, Ng C, Vanslambrouck JM, Rodgers H, et al. Iminoglycinuria and hyperglycinuria are discrete human phenotypes resulting from complex mutations in proline and glycine transporters. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3881–3892. doi: 10.1172/JCI36625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, Dreshfield-Ahmad LJ, Threlkeld PG, Shaw JL, Thompson L, Nelson DL, et al. Comparative affinity of duloxetine and venlafaxine for serotonin and norepinephrine transporters in vitro and in vivo, human serotonin receptor subtypes, and other neuronal receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:871–880. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E, Silvagni A. Dopamine reuptake by norepinephrine neurons: exception or rule? Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2004;16:121–128. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v16.i12.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI, Kotian P, Dehghani A, Gray JL, Kuzemko MA, Parham KA, et al. Cocaine and 3 beta-(4′-substituted phenyl)tropane-2 beta-carboxylic acid ester and amide analogues. New high-affinity and selective compounds for the dopamine transporter. J Med Chem. 1995;38:379–388. doi: 10.1021/jm00002a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield WL, Collie IT, Dickins RS, Epemolu O, McGuire R, Hill DR, et al. The first potent and selective inhibitors of the glycine transporter type 2. J Med Chem. 2001;44:2679–2682. doi: 10.1021/jm0011272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NH, Reith ME, Quick MW. Synaptic uptake and beyond: the sodium- and chloride-dependent neurotransmitter transporter family SLC6. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:519–531. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Tilley MR, Wei H, Zhou F, Zhou FM, Ching S, et al. Abolished cocaine reward in mice with a cocaine-insensitive dopamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9333–9338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600905103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu CS, Brickley S, Jensen K, Southwell A, McKinney S, Cull-Candy S, et al. GABA transporter deficiency causes tremor, ataxia, nervousness, and increased GABA-induced tonic conductance in cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3234–3245. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3364-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen B, Meinild AK, Jensen AA, Brauner-Osborne H. Cloning and characterization of a functional human gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporter, human GAT-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19331–19341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark JA, Deutch AY, Gallipoli PZ, Amara SG. Functional expression and CNS distribution of a beta-alanine-sensitive neuronal GABA transporter. Neuron. 1992;9:337–348. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90172-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen RP, Madsen K, Larsson OM, Frolund B, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Schousboe A. Structure-activity relationship and pharmacology of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transport inhibitors. Adv Pharmacol. 2006;54:265–284. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(06)54011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton DP, Quick M, Shi L, de Carvalho FD, Weinstein H, Javitch JA, et al. Ion/substrate-dependent conformational dynamics of a bacterial homolog of neurotransmitter : sodium symporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:822–829. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EH, Jr, Courchesne R, Lord C, Cox NJ, Yan S, Lincoln A, et al. Evidence of linkage between the serotonin transporter and autistic disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 1997;2:247–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremona ML, Matthies HJ, Pau K, Bowton E, Speed N, Lute BJ, et al. Flotillin-1 is essential for PKC-triggered endocytosis and membrane microdomain localization of DAT. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:469–477. doi: 10.1038/nn.2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, O'Brien CP. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:205–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilczyk U, Sarao R, Remy C, Benabbas C, Stange G, Richter A, et al. Essential role for collectrin in renal amino acid transport. Nature. 2006;444:1088–1091. doi: 10.1038/nature05475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deecher DC, Beyer CE, Johnston G, Bray J, Shah S, Abou-Gharbia M, et al. Desvenlafaxine succinate: a new serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:657–665. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelice LJ, Goswami T. Transporters as channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:87–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.164816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RI, Kopajtic TA, Koffarnus M, Newman AH, Katz JL. Identification of a dopamine transporter ligand that blocks the stimulant effects of cocaine. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1889–1893. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4778-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar TG, Borden LA, Tyagarajan S, Smith KE, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL, et al. Design, synthesis and evaluation of substituted triarylnipecotic acid derivatives as GABA uptake inhibitors: identification of a ligand with moderate affinity and selectivity for the cloned human GABA transporter GAT-3. J Med Chem. 1994;37:2334–2342. doi: 10.1021/jm00041a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd JR, Christie DL. Selective amino acid substitutions convert the creatine transporter to a gamma-aminobutyric acid transporter. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15528–15533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohi T, Morita K, Kitayama T, Motoyama N, Morioka N. Glycine transporter inhibitors as a novel drug discovery strategy for neuropathic pain. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;123:54–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta AK, Zhang S, Kolhatkar R, Reith ME. Dopamine transporter as target for drug development of cocaine dependence medications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwoskin LP, Rauhut AS, King-Pospisil KA, Bardo MT. Review of the pharmacology and clinical profile of bupropion, an antidepressant and tobacco use cessation agent. CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12:178–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen J, Jorgensen TN, Gether U. Regulation of dopamine transporter function by protein-protein interactions: new discoveries and methodological challenges. J Neurochem. 2010;113:27–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshleman AJ, Carmolli M, Cumbay M, Martens CR, Neve KA, Janowsky A. Characteristics of drug interactions with recombinant biogenic amine transporters expressed in the same cell type. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:877–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulenburg V, Armsen W, Betz H, Gomeza J. Glycine transporters: essential regulators of neurotransmission. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulenburg V, Retiounskaia M, Papadopoulos T, Gomeza J, Betz H. Glial glycine transporter 1 function is essential for early postnatal survival but dispensable in adult mice. Glia. 2010;58:1066–1073. doi: 10.1002/glia.20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhan H, Freissmuth M, Sitte HH. Oligomerization of neurotransmitter transporters: a ticket from the endoplasmic reticulum to the plasma membrane. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;175:233–249. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29784-7_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer MK, Robbins MJ, Medhurst AD, Campbell DA, Ellington K, Duckworth M, et al. Cloning and characterization of human NTT5 and v7-3: two orphan transporters of the Na+/Cl− -dependent neurotransmitter transporter gene family. Genomics. 2000;70:241–252. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fog JU, Khoshbouei H, Holy M, Owens WA, Vaegter CB, Sen N, et al. Calmodulin kinase II interacts with the dopamine transporter C terminus to regulate amphetamine-induced reverse transport. Neuron. 2006;51:417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LR, Rudnick G. The rocking bundle: a mechanism for ion-coupled solute flux by symmetrical transporters. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:377–386. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00030.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LR, Tavoulari S, Zhang YW, Rudnick G, Honig B. Identification of a chloride ion binding site in Na+/Cl -dependent transporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12761–12766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest LR, Kramer R, Ziegler C. The structural basis of secondary active transport mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:167–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JD, Pananusorn B, Vaughan RA. Dopamine transporters are phosphorylated on N-terminal serines in rat striatum. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25178–25186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Caron MG, Blakely RD. Molecular cloning and expression of a high affinity L-proline transporter expressed in putative glutamatergic pathways of rat brain. Neuron. 1992;8:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90206-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Velaz-Faircloth M, Miller JW, Henzi VA, Cohen SM, Nadler JV, et al. A novel nonopioid action of enkephalins: competitive inhibition of the mammalian brain high affinity L-proline transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:1033–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K, Yang Q, Cao Y, Takahashi N, Hatakeyama H, Wang H, et al. The HNF-1 target collectrin controls insulin exocytosis by SNARE complex formation. Cell Metab. 2005;2:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]