Abstract

The lack of phaseolin and phytohaemagglutinin in common bean (dry bean, Phaseolus vulgaris) is associated with an increase in total cysteine and methionine concentrations by 70% and 10%, respectively, mainly at the expense of an abundant non-protein amino acid, S-methyl-cysteine. Transcripts were profiled between two genetically related lines differing for this trait at four stages of seed development using a high density microarray designed for common bean. Transcripts of multiple sulphur-rich proteins were elevated, several previously identified by proteomics, including legumin, basic 7S globulin, albumin-2, defensin, albumin-1, the Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor, the double-headed trypsin inhibitor, and the Kunitz trypsin inhibitor. A co-ordinated regulation of transcripts coding for sulphate transporters, sulphate assimilatory enzymes, serine acetyltransferases, cystathionine β-lyase, homocysteine S-methyltransferase and methionine gamma-lyase was associated with changes in cysteine and methionine concentrations. Differential gene expression of sulphur-rich proteins preceded that of sulphur metabolic enzymes, suggesting a regulation by demand from the protein sink. Up-regulation of SERAT1;1 and -1;2 expression revealed an activation of cytosolic O-acetylserine biosynthesis. Down-regulation of SERAT2;1 suggested that cysteine and S-methyl-cysteine biosynthesis may be spatially separated in different subcellular compartments. Analysis of free amino acid profiles indicated that enhanced cysteine biosynthesis was correlated with a depletion of O-acetylserine. These results contribute to our understanding of the regulation of sulphur metabolism in developing seed in response to a change in the composition of endogenous proteins.

Key words: Common bean, cysteine, methionine, seed proteins, sulphur metabolism, transcript profiling

Introduction

Protein quality in legume crops is limited by the sub-optimal levels of the essential sulphur amino acids, Met and Cys. Among legumes grown for consumption of the whole grain as food, common bean (dry bean, Phaseolus vulgaris) is the most important worldwide (Broughton et al., 2003). A unique feature of Phaseolus and several Vigna species is the accumulation of a non-protein amino acid, S-methyl-Cys, to a high concentration in seed, of up to 0.3% per dry weight, mainly as a γ-Glu dipeptide (Giada et al., 1998). S-Methyl-Cys cannot substitute for Met or Cys in the diet (Padovese et al., 2001). Major seed proteins in common bean, the 7S globulin phaseolin and lectin phytohaemagglutinin, are poor in Met and Cys. In a set of genetically related lines, the absence of phaseolin and major lectins resulted in a shift of sulphur from S-methyl-Cys to the sulphur amino acid pool in protein (Taylor et al., 2008). The concentration of sulphur amino acids in seed was elevated by 70% for Cys and 10% for Met, to levels of 27mg g–1 protein, compared with FAO requirement scoring patterns of 22–28mg g–1 protein, depending on age group (WHO, 2007). Proteomic analysis identified several sulphur-rich proteins whose levels are elevated in the absence of phaseolin and major lectins, including the 11S globulin legumin, albumin-2, defensin, albumin-1, and the Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor (Marsolais et al., 2010). Under these conditions, legumin becomes the dominant storage protein, accounting for at least 17% of total protein. Integration of proteomic and functional genomic data enabled the identification and isolation of cDNAs encoding these proteins (Yin et al., 2011). These characteristics are reminiscent of the opaque-2 mutant, which was used to develop Quality Protein Maize (Huang et al., 2009).

To date, most approaches to improve protein quality in grain legumes have involved the transgenic expression of sulphur-rich proteins, sometime in combination with metabolic engineering of sulphur amino acid pathways. Expression of the foreign protein is often limited by the supply of sulphur and can result in decreased expression of endogenous sulphur-rich proteins (Streit et al., 2001; Tabe and Droux, 2002). In soybean, transgenic expression of Brazil nut 2S albumin increased Met concentration by 26% (Townsend and Thomas, 1994), while expression of 15kDa δ-zein increased Met and Cys concentrations by 20% and 35%, respectively (Dinkins et al., 2001). With 11kDa δ-zein, the Met concentration was increased in the alcohol-soluble protein fraction, but not overall in the seed (Kim and Krishnan, 2004). In common bean, the expression of Brazil nut 2S albumin increased the Met concentration by 20% (Aragao et al., 1999). In lupin and chickpea, expression of sunflower seed albumin stimulated sulphur assimilation. Sulphur was shifted from the sulphate to the protein Met pool, elevated by 90%, while the concentration of Cys was reduced by 10% (Molvig et al., 1997; Tabe and Droux, 2001; Chiaiese et al., 2004). In Vicia narbonensis, which accumulates little sulphate in mature seed, co-expression of Brazil nut 2S albumin with a feedback-insensitive, bacterial Asp kinase increased Met and Cys concentrations by 100% and 20%, respectively (Demidov et al., 2003). The increased levels of Met and Cys were accompanied by decreases in the concentration of γ-Glu-S-ethenyl-Cys (2-fold) and free thiols, particularly γ-Glu-Cys and glutathione. About two-thirds of the increase in Met and Cys concentration was attributed to an enhanced supply of sulphur to the seed. However, the potential allergenicity of Brazil nut 2S and sunflower seed albumins limits their practical usefulness for crop improvement (Nordlee et al., 1996; Kelly and Hefle, 2000).

Although the seed is a major target for the biotechnological improvement of total Met and Cys levels, there is a relative lack of information on the regulation of sulphur amino acid metabolism in this tissue. Some specific features are related to sulphur nutrition and assimilation. In soybean, sulphate in pods is transformed into homoglutathione, which is mobilized into developing seed (Anderson and Fitzgerald, 2001). While homoglutathione contributes Cys, S-methyl-Met is anticipated to be a major form of Met transported to the seed (Bourgis et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2010). Assimilation of transported S-methyl-Met requires homocysteine as an acceptor of the S-methyl group. Under sulphur-sufficient conditions, soybean seeds do accumulate detectable levels of sulphate throughout development (Naeve and Shibles, 2005). Recent functional genomic studies have highlighted the occurrence of complete pathways of sulphate assimilation and de novo Cys and Met biosynthesis in developing seed, both in soybean and common bean (Yi et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2011). Considering the roles of homoglutathione and S-methyl-Met as organic sulphur transport forms, the contribution of sulphate assimilation and de novo Cys and Met biosynthesis remains to be fully elucidated.

Recently, seed-specific transgenic expression of a chloroplastic, feedback-insensitive Ser acetyltransferase (SERAT) in lupin increased the concentration of O-acetylserine and free Cys (Tabe et al., 2010). Despite this, the total concentration of Cys and Met remained unaltered, even after co-segregation of the sunflower seed albumin transgene. This was interpreted as further evidence that sulphate assimilation and Cys biosynthesis are regulated independently from Met biosynthesis, which is part of the Asp-derived amino acid pathway (Galili et al., 2005). Constitutive over-expression of a cytosolic form of O-acetylserine sulphhydrylase (OASS) in transgenic soybean led to sustained enzymatic activity at the late stages of seed development and resulted in a 70% increase in total Cys concentration in mature seed (Kim et al., 2012). This was associated with enhanced levels of the endogenous Cys-rich protein, the Bowman–Birk protease inhibitor.

Genetically related lines of common bean which integrate a deficiency in phaseolin and phytohaemagglutinin constitute a unique system to investigate the regulation of sulphur amino acid metabolism in seed, since perturbations are the result of changes in the levels of endogenous proteins, arising from natural genetic variation. Osborn et al. (2003) described their generation. SARC1 contains arcelin-1 introduced from a wild accession into the navy bean cultivar Sanilac. SMARC1N-PN1 lacks phaseolin and major lectins through the introgression of recessive null alleles from a Phaseolus coccineus accession and ‘Great Northern 1140’, respectively. SARC1 and SMARC1N-PN1 share a similar level of the parental, Sanilac background (ca. 85%). In the present study, global analysis of transcripts and free amino acids was performed between the two genotypes at four stages spanning the developmental period of γ-Glu-S-methyl-Cys accumulation in seed (Yin et al., 2011).

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Plants of common bean (dry bean, Phaseolus vulgaris) lines SARC1 and SMARC1N-PN1 (Osborn et al., 2003) were grown in the field in London, Ontario, Canada, in 2009. Developing seeds were harvested at four developmental stages, designated after Walbot et al. (1972): stage IV, cotyledon (average seed weight of 25mg); stage V, cotyledon (50mg); stage VI, maturation (150mg); and stage VIII, maturation (380mg). They were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C.

RNA extraction

Replicate samples consisted of 10–30 seeds pooled randomly from different plants. Four independent extractions were performed for each genotype and developmental stage, for a total of 32 samples. Seeds were ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted from 0.5–1g of tissue using a modified lithium chloride precipitation method as described by Bruneau et al. (2006). RNA was quantified by spectrophotometry with a NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, Delaware, United States) and its quality evaluated from A 260/280 ratio and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Assembly of expressed sequence tags and design of CustomArray 90K array

Common bean expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from BAT93 seed (Yin et al., 2011) were pooled with other common bean ESTs from GenBank dbEST (as of 1 August 2009) to generate a starting dataset of 111 255 sequences. This dataset was processed using SEQCLEAN in order (i) to remove sequences shorter than 100bp; (ii) to remove low-complexity and low-quality sequences; (iii) to trim poly A/T and undetermined bases (N); (iv) to use the National Center for Biotechnology Information UniVec collection for end-trimming of vector sequences and removal if necessary; and (v) to remove sequences matching the Escherichia coli genome, and ribosomal RNA small and large subunits at the level of 96% identity. The SEQCLEAN procedure resulted in the removal of 3427 sequences and the trimming of an additional 29 445 sequences leaving 107 828 sequences available for assembly. The SEQCLEAN program is part of the PASA pipeline (Haas et al., 2003). The cleaned EST dataset was then clustered and assembled using TGICL (Pertea et al., 2003) using default parameters except for specifying 96% identity for CAP3 contig assembly. A few sequences coding for arcelin or leucoagglutining phytohaemagglutinin were added from GenBank. However, among differentially expressed lectins that were previously identified by proteomics (Marsolais et al., 2010), mannose lectin FRIL was omitted. The assembly contained 18 742 contigs or singletons. The assembly was annotated by BlastX to the UniProt database, Viridiplantae taxonomy, by identifying the best hit with an informative annotation having an e-value smaller than or equal to 1×10–5. This assembly was used to design probes on a CustomArray 90K array (Mukilteo, Washington, United States). A total of 18 415 unigenes were represented on the array. Most of these were represented by five 35–40-mer probes (16 510), with the remainder represented by four (480), three (470), two (522), or one probe (431). For contigs or singletons with two probes, these probes were placed in duplicate on the array. For those with one probe, five replicates were placed on the array. A total of 1597 were duplicate probes corresponding to two or more contigs or singletons. Two ubiquitin contigs were present to use as control, with 30 replicates of their five individual probes (CL1Contig148 and CL1Contig270). Arrays were manufactured using a CustomArray B3 Synthesizer at the Plant Biotechnology Institute in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

Microarray hybridization and data acquisition

Amplified RNA (aRNA) was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA treated with amplification-grade DNase I (Life Technologies, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) using RNA ampULSe: Amplification and Labeling Kit (Kreatech Diagnostics, Durham, North Carolina, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Four µg of purified aRNA was labelled with Cy5 and hybridized to the arrays according to CustomArray protocols. The images were scanned with a GenePix 4000B scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, California, United States) at values of 5 µm resolution, a focal depth of 150 µm, 100% laser power, and photomultiplier gain of 400. Data were extracted using GenePix Pro 6.1.0.4. One slide from stages VI and VIII were discarded due to uneven hybridization, leaving three biological replicates for stages VI and VIII, as compared with four at stages IV and V, for a total of 28 samples. Scanned data were adjusted with local background median values and filtered to remove poor or ‘absent’ probes with median signals smaller than the negative control median values plus twice the standard deviation (Polesani et al., 2010). Probes passing this filtering for at least 6 of the 28 samples were included in the normalization and further analysis.

Microarray data analysis

Probe intensities were adjusted with local background subtraction, log2 transformed, and then quantile normalization was applied at the probe level with GeneSpring GX v. 11.5 (Agilent Technologies, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The final expression value of a given transcript on each array was determined by averaging probe intensities after Tukey’s median polish, which was performed with the R statistical software, and applying baseline transformation. The list of genes, differentially expressed between SARC1 and SMARC1N-PN1 at each developmental stage, was obtained using the cutoffs of 1.4-fold and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with corrected P values smaller than 0.05, which was computed via asymptotic distribution and Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate multiple testing correction. Analysis of metabolic pathway genes was aided by consulting the Plant Metabolic Network (PMN) database (Zhang et al., 2010).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

Four µg of DNase I-treated RNA was reverse transcribed with 50 µM of Oligo(dT)20 primers using ThermoScriptTM reverse transcriptase following the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). Quantitative PCR was performed using a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Reactions contained primers at a concentration of 0.5 µM (see Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online). They were carried out in Hard-Shell 96-well PCR plates (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in a final volume of 10 µl. The reaction contained 5 µl of 2× SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and 2 µl of a 32-fold dilution of the cDNA. The PCR program consisted of an initial step of 3min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 59 °C. Data were analysed using CFX Manager 2.0. Data were expressed as the cycle number necessary to reach a threshold fluorescence value (C q). The reported values are the means of three biological replicates consisting of independent RNA extracts, with each biological replicate the average of three technical replicates. Data were normalized to the mean C q of the ubiquitin reference gene (CL1Contig148), for which the variation between genotypes and developmental stages was smaller than or equal to 0.6. The specificity of primer pairs was confirmed by melt curve analysis in comparison with controls without template and by agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products. PCR efficiency of ubiquitin was calculated from a standard curve of C q versus the logarithm of starting template quantity. Efficiency was 92%, with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.99.

Extraction and quantification of free amino acids

Amino acids were extracted in triplicate and quantified by HPLC after derivatization with phenylisothiocyanate as previously described (Yin et al., 2011). Cysteine was determined separately as cysteic acid, after performic acid oxidation.

Accession number

Expression data were deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus of the National Center for Biotechnology Information with accession number [GEO: GSE34233].

Results

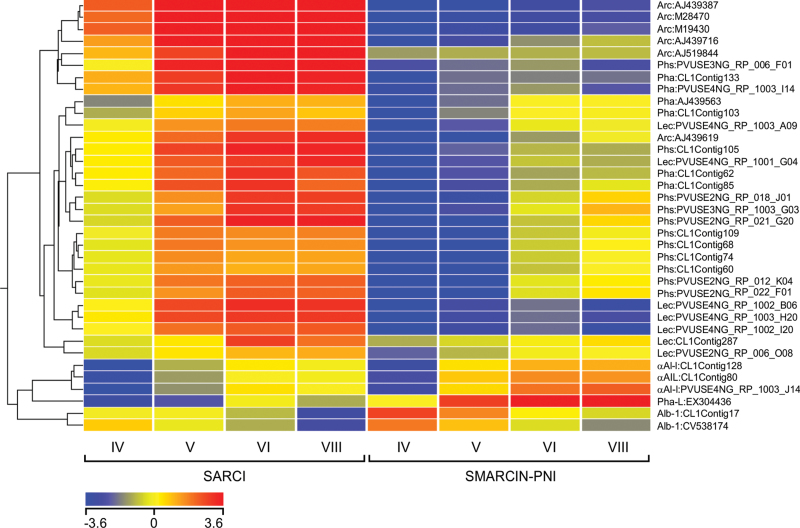

The four developmental stages selected for microarray analysis span the entire period of γ-Glu-S-methyl-Cys accumulation in seed (Yin et al., 2011). During seed development, phaseolin and phytohaemagglutinin transcripts are most abundant between stages IV to VI, while phaseolin as a protein accumulates between stages V to VII (Bobb et al., 1995). Seed desiccation takes place during stage VIII. Hierarchical clustering of expression values for major seed protein transcripts that were differentially expressed between SARC1 and SMARC1N-PN1 throughout all four developmental stages were consistent with previous proteomic findings (Fig. 1) (Marsolais et al., 2010). Lower expression values were systematically observed for phaseolin, arcelin, lectin, and most phytohaemagglutinin contigs in SMARC1N-PN1. Low values measured for arcelin may be due to cross-hybridization with related, residual lectin sequences (Marsolais et al., 2010). Similarly, a residual phaseolin isoform was previously shown to be expressed at low levels in SMARC1N-PN1. α-Amylase inhibitor-1, α-amylase inhibitor like protein, leucoagglutinating phytohaemagglutinin (PHA-L), and albumin-1 contigs had higher expression values, consistent with the fact that the corresponding proteins were previously shown to compensate, in part, for the absence of phaseolin and major lectins in SMARC1N-PN1.

Fig. 1.

Cluster analysis of seed storage protein genes differentially expressed between SMARC1N-PN1 and SARC1 at all four developmental stages, using a threshold value of 1.4-fold and a corrected P value smaller than 0.05. Expression values measured by microarray analysis were used for hierarchical clustering. Values are the means of four biological replicates at stages IV and V, and three biological replicates at stages VI and VIII. Abbreviations are as follows: Arc, arcelin; Phs, phaseolin; Pha, phytohaemagglutinin; Lec, lectin; AI, amylase inhibitor; AIL, amylase inhibitor-like; Pha-L, leucoagglutinating phytohaemagglutinin, Alb, albumin.

Differential expression of transcripts coding for sulphur-rich proteins

The microarray data were examined for differential expression of transcripts coding for sulphur-rich proteins (Table 1). To identify corresponding genes, contig sequences were searched by BlastX against the proteome predicted from the early release genome of the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris v1.0, DOE-JGI and USDA-NIFA, http://www.phytozome.net/commonbean_er). Sulphur-rich proteins previously identified by proteomics as elevated in SMARC1N-PN1 also had increased transcript levels. They include legumin, albumin-2, defensin D1, albumin-1A and -B, and the Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor. The corresponding contigs were identified by comparison with tryptic peptide sequences determined either de novo with PEAKS or through MASCOT searches (Marsolais et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2011). Transcripts of additional types of sulphur-rich proteins were identified as differentially expressed, including the basic 7S globulin, double-headed trypsin, and Kunitz trypsin protease inhibitors. Soybean basic 7S globulin, known as γ-conglutin in lupin, is a minor Cys-rich globulin with structural similarity to xyloglucan-specific endo-β-1,4-glucanase inhibitor-like protein (Scarafoni et al., 2010; Yoshizawa et al., 2011), which has insulin-binding properties and glucose-lowering nutritional effects (Hanada and Hirano, 2004; Magni et al., 2004; Lovati et al., 2012). The predicted amino acid sequence of the basic 7S globulin-2 from common bean has 3% of its residues as Cys and 1.9% as Met; 13.3% as Cys and 2.5% as Met for the double headed trypsin inhibitor; and 2.3% as Cys and 0.9% as Met for the Kunitz trypsin protease inhibitor. For some types of sulphur-rich protein already known from proteomics, novel contig sequences were identified as differentially expressed. There were five albumin-2 contigs matching three different genes located at a single locus on chromosome 7 within an interval of approximately 20kb. A γ-thionin contig is 58% identical in amino acid sequences with defensin D1, and their fold change values had a similar developmental profile. The corresponding genes were present on different chromosomes, 5 and 9. A total of 21 albumin-1 contigs were differentially expressed matching eight genes present at a unique locus spanning an interval of approximately 110kb on chromosome 11. Among these, transcripts were most elevated for albumin-1A (10-fold), albumin-1E (7-fold), and albumin-1F contigs (11-fold). The three differentially expressed genes coding for the Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor 2 and the double-headed trypsin inhibitor/trypsin chymotrypsin inhibitor are also co-localized on chromosome 4 within an interval of approximately 20kb. Differential expression was observed at distinct developmental stages. Albumin-2, albumin-1E, the Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor 2, and the double-headed trypsin inhibitor contigs had increased transcript levels starting from stage IV. This was followed by legumin and basic 7S globulin-2 at stage V. Defensin D1 was differentially expressed at stage VI, and albumin-1A and -B at stage VIII. Transcripts of the Kunitz trypsin protease inhibitor were elevated at stages VI and VIII. For some abundant transcripts, differential expression could not be evaluated when signal intensities were saturated, at values near 15.5 (see Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online). This was the case for defensin D1 at stage VIII, and for the Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor 2 and the double headed trypsin inhibitor starting at stages VI and VIII. In parallel with transcripts of Cys-rich proteins, those of three different chaperones involved in the formation of disulphide bridges were also elevated (Table 2).

Table 1.

Fold change of transcripts coding for sulphur-rich proteins in SMARC1N-PN1 as compared with SARC1. A negative value refers to a reduced expression in SMARC1N-PN1 by the corresponding fold change. Values statistically significant at P ≤0.05 are highlighted in bold. Contigs with evidence for differential expression at the protein level are highlighted with an asterisk (Marsolais et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2011). Protein accession was identified by BlastX of early release of the Phaseolus vulgaris genome (Phaseolus vulgaris v1.0, DOE-JGI and USDA-NIFA, http://www.phytozome.net/commonbean_er).

| Annotation | Contig/singleton | Protein | Identity (%) | Developmental stage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | V | VI | VIII | ||||

| Legumin | CL647Contig1* | Phvul.007G192800.1 | 98 | 1.46 | 2.33 | 1.35 | 1.70 |

| Basic 7S globulin-2 | CL10519Contig1 | Phvul.006G093600.1 | 100 | 1.17 | 2.20 | 1.80 | 2.25 |

| CL671Contig1 | Phvul.006G093600.1 | 100 | 1.11 | 2.49 | 2.15 | 2.02 | |

| Albumin-2 | CL46Contig1* | Phvul.007G275800.1 | 100 | 2.60 | 2.46 | 1.23 | 1.28 |

| CL46Contig3 | Phvul.007G276200.1 | 100 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.00 | 2.44 | |

| CL46Contig7 | Phvul.007G276200.1 | 88 | 1.08 | 1.22 | −1.09 | 2.27 | |

| CV533282 | Phvul.007G276200.1 | 91 | −1.14 | −1.11 | –1.66 | 2.89 | |

| FG231390 | Phvul.007G276100.1/-.2 | 91 | 1.22 | 1.37 | 1.12 | 2.68 | |

| Defensin D1 | CL586Contig1* | Phvul.005G071300.1 | 99 | 1.17 | 1.43 | 3.86 | 1.03 |

| γ-Thionin | CL1108Contig1 | Phvul.009G158000.1 | 100 | 1.38 | 2.03 | 3.15 | 1.68 |

| Albumin-1A | CL1Contig108* | Phvul.011G205400.1/-300.1 | 97 | 1.44 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 9.77 |

| Albumin-1A | PVUSE3NG_T3_011_O21 | Phvul.011G205400.1/-300.1 | 96 | 1.07 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 4.00 |

| Albumin-1A | CL1Contig69 | Phvul.011G205400.1/-300.1 | 90 | 1.19 | 1.32 | 1.25 | 5.58 |

| Albumin-1B | CL1Contig83* | Phvul.011G205400.1/-300.1 | 98 | 1.33 | 1.09 | 1.13 | 4.77 |

| Albumin-1B | CL1Contig10* | Phvul.011G205400.1/-300.1 | 94 | 1.39 | −1.01 | 1.00 | 4.66 |

| Albumin-1B | CL1Contig64 | Phvul.011G205400.1/-300.1 | 92 | 1.70 | 1.30 | 1.64 | 6.85 |

| Albumin-1C | CL1Contig43 | Phvul.011G204600.1 | 93 | 1.84 | 1.89 | 1.38 | 2.04 |

| Albumin-1C | CV539755 | Phvul.011G204600.1 | 91 | 2.48 | 1.35 | 1.35 | 1.35 |

| Albumin-1C | CV538174 | Phvul.011G204600.1 | 88 | 2.27 | 2.15 | 1.58 | 2.30 |

| Albumin-1C | CV540424 | Phvul.011G204700.1 | 88 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 1.50 | 1.42 |

| Albumin-1D | CL1Contig82 | Phvul.011G205500.1 | 99 | 1.87 | 1.20 | 1.38 | 8.38 |

| Albumin-1D | CL1Contig87 | Phvul.011G205500.1 | 99 | 1.46 | 1.12 | 1.00 | 5.55 |

| Albumin-1D | PVUSE4NG_RP_1004_F21 | Phvul.011G205500.1 | 95 | 1.28 | 1.03 | −1.01 | 3.10 |

| Albumin-1D | PVUSE2NG_RP_027_K19 | Phvul.011G205500.1 | 93 | 1.34 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 6.29 |

| Albumin-1E | CL1Contig17 | Phvul.011G204700.1 | 99 | 7.17 | 3.39 | 2.37 | 5.62 |

| Albumin-1E | CL1Contig141 | Phvul.011G205200.1 | 100 | 1.37 | 2.33 | 1.14 | 1.37 |

| Albumin-1F | CL1Contig110 | Phvul.011G205600.1 | 100 | 1.67 | 1.07 | 1.70 | 10.21 |

| Albumin-1F | PVUSE2NG_RP_018_O15 | Phvul.011G205500.1 | 95 | 1.30 | 1.64 | 2.54 | 10.88 |

| Albumin-1F | PVUSE3NG_RP_014_O07 | Phvul.011G205400.1/-300.1 | 94 | 1.21 | 1.02 | 1.25 | 4.64 |

| Albumin-1G | PVUSE4NG_RP_1003_G20 | Phvul.011G205500.1 | 100 | 1.72 | 1.18 | 1.37 | 5.64 |

| Albumin-1G | CL1Contig42 | Phvul.011G204400.1 | 98 | 2.18 | 1.61 | −1.20 | 1.98 |

| Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor 2 | CL1Contig140* | Phvul.004G133900.1 | 100 | 3.80 | 3.58 | −1.03 | 1.30 |

| Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor 2 | PVUSE4NG_RP_1003_O21 | Phvul.004G133900.1 | 100 | 4.28 | 3.58 | 1.04 | 1.30 |

| Double-headed trypsin inhibitor | CL10Contig1 | Phvul.004G134100.1 | 95 | 3.19 | 1.71 | −1.03 | 1.09 |

| Trypsin/chymotrypsin inhibitor | CL10Contig2 | Phvul.004G134000.1 | 95 | 3.21 | 1.78 | 1.03 | 1.04 |

| Trypsin/chymotrypsin inhibitor | PVUSE3NG_RP_1003_M20 | Phvul.004G134000.1 | 89 | 3.19 | 2.36 | 1.01 | 1.53 |

| Kunitz trypsin protease nhibitor | CL3713Contig1 | Phvul.004G129900.1 | 88 | −1.25 | −1.19 | 2.06 | 3.00 |

| Trypsin inhibitor | PVUSE2NG_RP_008_J18 | Phvul.004G129900.1 | 81 | −1.31 | −1.23 | 3.05 | 3.48 |

Table 2.

Fold change of transcripts coding for enzymes involved in the formation of protein disulphide bridges in SMARC1N-PN1 compared with SARC1. A negative value refers to a reduced expression in SMARC1N-PN1 by the corresponding fold change. Values significant at P ≤0.05 are highlighted in bold. Protein accession was identified by BlastX of the early release of the Phaseolus vulgaris genome.

| Annotation | Contig/singleton | Protein | Developmental stage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | V | VI | VIII | |||

| γ-Interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase | CL1852Contig1 | Phvul.006G072600.1 | 1.06 | 1.25 | 2.12 | 2.20 |

| CL1852Contig2 | Phvul.006G072600.1 | 1.15 | 1.31 | 2.08 | 1.90 | |

| Protein disulphide isomerise | CL1Contig224 | Phvul.009G126800.1 | −1.23 | 1.16 | 1.53 | 2.03 |

| FE685484 | Phvul.009G126800.1 | −1.34 | −1.16 | 1.35 | 2.02 | |

| Protein disulphide oxidoreductase | CL4975Contig1 | Phvul.008G027600.1 | 1.59 | 1.41 | 1.42 | 1.64 |

| CL4975Contig2 | Phvul.008G027600.1 | 1.68 | 1.51 | 1.50 | 1.84 | |

Co-ordinate regulation of sulphur metabolic transcripts

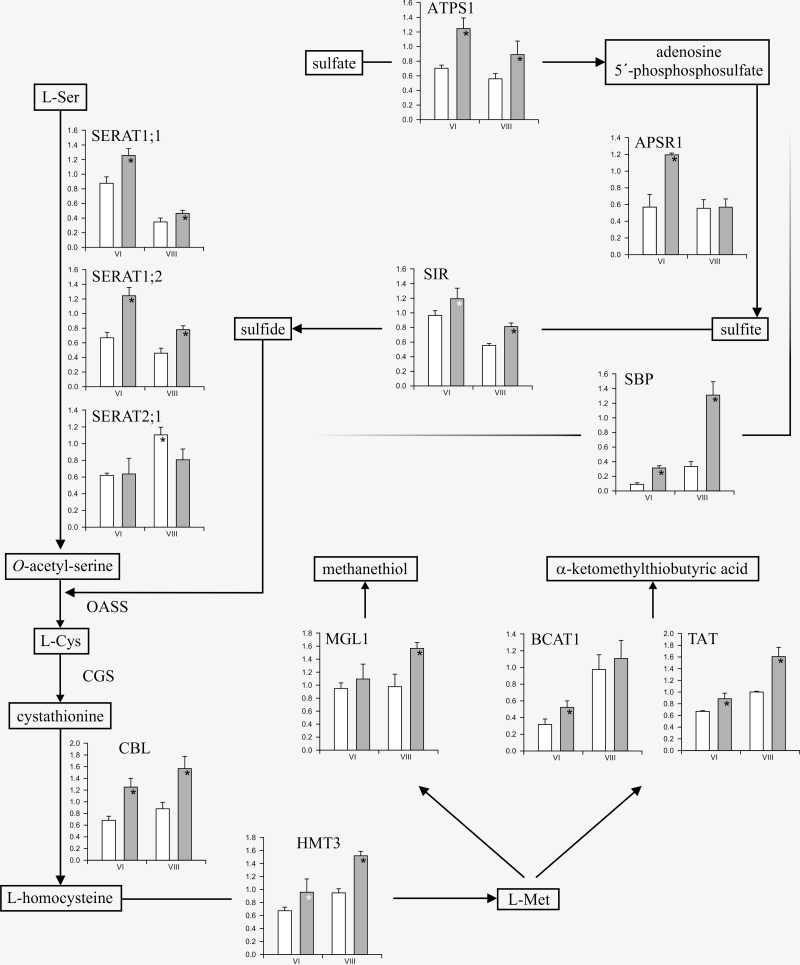

To obtain a better understanding of the mechanism(s) controlling the concentration of sulphur amino acids, the microarray data were examined for the differential expression of sulphur metabolic genes between the two genotypes (Table 3). Transcripts coding for enzymes associated with several processes of sulphur metabolism were significantly increased in SMARC1N-PN1 compared with SARC1, exclusively at the last two developmental stages, VI and VIII. The contigs were associated with specific genes in the P. vulgaris genome identified using a BlastX search, and a nomenclature developed on the basis of phylogenetic clustering with Arabidopsis and soybean homologues (Yi et al., 2010; Hell and Wirtz, 2011; Takahashi et al., 2011). Differential expression of transcripts for sulphur metabolic enzymes was systematically validated by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and the results of these experiments are presented in Fig. 2. Transcript levels of two sulphate transporters, Sultr1;2 and Sultr3;3, were elevated in SMARC1N-PN1 at stage VI, which coincides with the active phase of storage protein accumulation (Table 3). Expression of genes coding for enzymes involved in the three steps of sulphate assimilation was increased in SMARC1N-PN1 (Fig. 2). Transcripts of sulphate adenylyltransferase, ATPS1, which catalyses the formation of an activated form of sulphate, adenosine 5’-phosphosulphate, were elevated at stages VI and VIII by up to 1.8-fold. Transcripts of adenylylsulphate reductase, APSR1, which forms sulphite, were elevated at stage VI, by 2-fold. Sulphite reductase, SIR, was not represented on the array. However, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis indicated that its transcript was also elevated at stage VIII, by 1.5-fold. Transcript levels of selenium binding protein, SBP, a marker of sulphate assimilation (Hugouvieux et al., 2009), were also increased by 3.5- and 4.9-fold at stages VI and VIII, respectively. Among Cys biosynthetic enzymes, transcripts for SERATs, SERAT1;1 and -1;2, which synthesize O-acetylserine, were elevated at both developmental stages in SMARC1N-PN1, particularly SERAT1;2, by 1.9-fold at stage VI (Fig. 2). SERAT1;1 and -1;2 were represented by a single contig on the microarray (Table 3) and their amino acid sequences are 99.3% identical. According to phylogeny and analysis with WoLFPSORT (Horton et al., 2007), they are predicted to be localized in the cytosol. Transcripts of SERAT2;1, were decreased in SMARC1N-PN1 by approximately 1.5-fold at the last developmental stage (Fig. 2). Arabidopsis has two SERAT2 genes whose products are localized in plastids or mitochondria (Noji et al., 1998). A fusion between soybean SERAT2;1 and a fluorescent protein was detected in the cytosol and plastids (Liu et al., 2006). WoLFPSORT results for common bean SERAT2;1 were ambiguous but indicated a putative plastidic localization.

Table 3.

Fold change of transcripts for sulphur metabolic genes in SMARC1N-PN1 compared with SARC1 A negative value refers to a reduced expression in SMARC1N-PN1 by the corresponding fold change. Values significant at P ≤0.05 are highlighted in bold. Protein accession was identified by BlastX of the early release of the Phaseolus vulgaris genome.

| Enzyme | Gene | Contig/singleton | Protein | Developmental stage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | V | VI | VIII | ||||

| Sulphate transporter | Sultr1;2 | CL5762Contig1 | Phvul.009G028500.1 | 1.11 | 1.04 | 1.50 | 1.07 |

| Sultr3;3 | CL8298Contig1 | Phvul.004G161600.1 | −1.17 | 1.12 | 1.46 | 1.31 | |

| Sulphate adenylyltransferase | ATPS1 | EX304361 | Phvul.007G062900.1 | −1.42 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.45 |

| Adenylyl sulphate reductase | APSR1 | CL1146Contig1 | Phvul.006G149200.1 | −1.26 | −1.15 | 1.66 | −1.14 |

| CL1146Contig2 | Phvul.006G149200.1 | −1.38 | 1.10 | 1.90 | −1.09 | ||

| EG948451 | Phvul.006G149200.1 | −1.33 | −1.20 | 1.50 | −1.14 | ||

| Sulphite oxidase | SO | CL6806Contig1 | Phvul.004G054200.1 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 1.62 | 1.54 |

| Serine acetyltransferase | SERAT1;1/-1;2 | PVUSE3NG_RP_008_F02 | Phvul.001G170600.1/-010G110600.1 | 1.06 | 1.41 | 1.58 | 1.08 |

| SERAT2;1 | CL1591Contig1 | Phvul.006G055200.1 | 1.04 | −1.20 | −1.04 | −1.52 | |

| Cystathionine β-lyase | CBL | CL6595Contig1 | Phvul.001G125400.1 | 1.05 | 1.12 | 1.71 | 1.65 |

| Homocysteine S-methyltransferase | HMT3 | CL2920Contig1 | Phvul.007G060300.1 | −1.22 | −1.10 | 1.41 | 1.19 |

| FE897548 | Phvul.007G060300.1 | −1.29 | −1.09 | 1.57 | 1.76 | ||

| Methionine γ-lyase | MGL1 | CL2938Contig1 | Phvul.001G082000.1 | 1.03 | −1.31 | 1.12 | 1.53 |

| CL2938Contig2 | Phvul.001G082000.1 | −1.02 | −1.02 | 1.06 | 1.47 | ||

| MGL2 | CL5700Contig1 | Phvul.004G090200.1 | 1.02 | 1.08 | 1.17 | 1.49 | |

| Branched chain amino acid | BCAT1 | CL2797Contig1 | Phvul.009G075100.1 | 1.24 | −1.03 | 1.75 | 1.26 |

| Aminotransferase | |||||||

| Tyrosine aminotransferase | TAT | CL481Contig1 | Phvul.011G157500.1/-.2 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 1.47 | 1.46 |

| Selenium binding protein | SBP | CL360Contig1 | Phvul.001G265900.1 | −1.07 | −1.16 | 2.82 | 3.79 |

| CL360Contig2 | Phvul.001G265900.1 | −1.22 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 2.01 | ||

| FE898012 | Phvul.001G265900.1 | −1.02 | −1.18 | 2.23 | 3.18 | ||

| PVUSE4NG_RP_013_M18 | Phvul.001G265900.1 | 1.00 | −1.18 | 2.34 | 3.31 | ||

Fig. 2.

Differential expression of genes in sulphur amino acid pathways in developing seeds of SARC1 and SMARC1N-PN1. Relative transcript expression was determined by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Data were normalized to the mean C q of the reference gene, ubiquitin. Values are the means of three biological replicates ± standard deviation, with each biological replicate the average of three technical replicates. White bars in the histograms correspond to values from SARC1 and grey bars to values from SMARC1N-PN1. ANOVA P values ≤0.05 are marked with a black asterisk. A white asterisk indicates a P value of 0.06 for SIR and 0.08 for HMT. Abbreviations are as follows: ATPS, sulphate adenylyltransferase; APSR, adenylyl sulphate reductase; SIR, sulphite reductase; SERAT, Ser acetyltransferase; OASS, O-acetylserine sulphhydrylase; CGS, cystathionine γ-synthase; CBL, cystathionine β-lyase; HMT, homocysteine S-methyltransferase; MGL, Met γ-lyase; BCAT, branched chain amino acid aminotransferase; TAT, Tyr aminotransferase; SBP, selenium binding protein.

Transcripts of cystathionine β-lyase, CBL, catalysing the second step in Met biosynthesis which produces homocysteine were elevated in SMARC1N-PN1 at both stages VI and VIII, by approximately 1.8-fold. Transcripts of homocysteine S-methyltransferase, HMT3, which catalyses the transfer of the methyl group from S-methyl-Met or S-adenosylmethionine to homocysteine, producing Met, were also elevated by 1.6-fold at stage VIII. Transcripts for enzymes that are potentially involved in Met catabolism, including Met γ-lyase, MGL1, branched chain amino acid aminotransferase, BCAT1, and Tyr aminotransferase, TAT, were also increased.

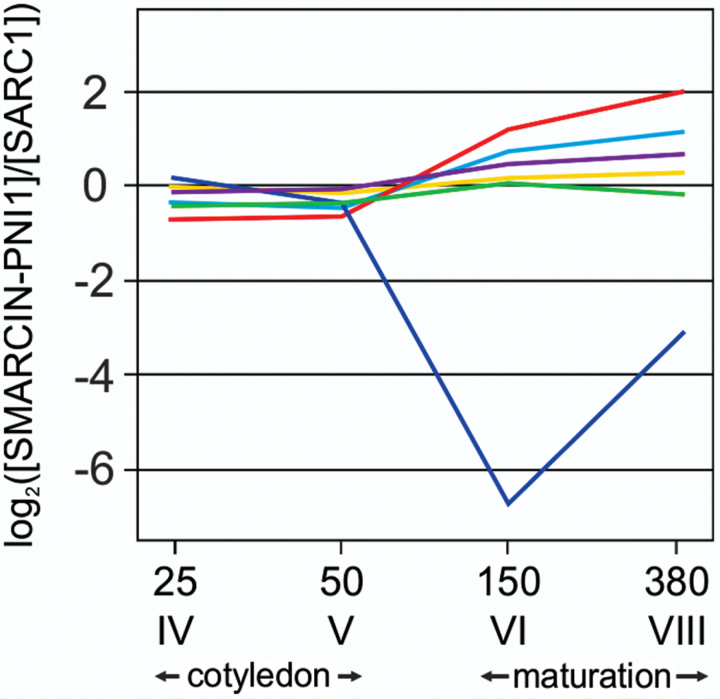

Activation of Cys and Met biosynthesis is correlated with a depletion of O-acetylserine

To understand better the relationship between transcripts of meta bolic genes and biochemical intermediates during seed development, free amino acids were profiled between SMARC1N-PN1 and SARC1. Free amino acid concentration was determined at the four developmental stages and expressed in nmol mg–1 seed weight (see Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). The ratio of amino acid concentration in SMARC1N-PN1 relative to SARC1 was expressed in a log2 scale. Data were classified by k-means analysis into six clusters (Fig. 3). One grouped the nitrogen-rich amino acids, Asn, Arg, His, citrulline, and Gln, whose concentration was lower in SMARC1N-PN1 at the first two developmental stages and higher at the last two. In mature seed of SMARC1N-PN1, the levels of these amino acids, except Gln, as well as the total Arg concentration, are elevated as a compensatory mechanism for the lack of major seed proteins (Taylor et al., 2008). The cluster grouping Ser, Ala, Val, Orn, and Lys showed a similar pattern as the previous one, except that the ratio of concentrations between genotypes was less elevated at the last developmental stage. Among these amino acids, the concentration of Ala and Lys is also elevated in mature seed of SMARC1N-PN1 (Taylor et al., 2008). The largest cluster grouped amino acids whose levels were similar between genotypes at the first developmental stages and slightly elevated in SMARC1N-PN1 at stage VIII. Within this cluster, levels of Asp, Gly, and γ-Glu-Leu are also elevated in mature seed of SMARC1N-PN1. Cys was part of this group, and its levels were consistently higher in SMARC1N-PN1 as compared with SARC1 throughout development (see Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online). Concentrations were fairly similar between genotypes for the cluster grouping Thr, α-amino-N-butyric acid, Tyr, and Phe. These amino acids are found at a similar level in mature seed of the two genotypes. O-Acetylserine was clustered separately from all other free amino acids. Its levels were strongly reduced in SMARC1N-PN1 at the last two developmental stages, indicating that enhanced accumulation of Cys in the protein pool was correlated with a depletion of its immediate precursor. The last cluster grouped free amino acids present at equal or lower levels throughout development. As expected, these included S-methyl-Cys and γ-Glu-S-methyl-Cys. Also in this group, Met levels were lower in SMARC1N-PN1 at the first two developmental stages and became equal between genotypes as they reached very low levels at the last two developmental stages.

Fig. 3.

Cluster analysis of free amino acid profiles during seed development. The ratio of free amino acid concentration in SMARC1N-PN1 versus SARC1 was classified using k-means analysis into six groups. The average of each cluster has been plotted. The cluster in red includes Asn, Gln, His, citrulline, and Arg; in pale blue Ser, Ala, Val, Orn, and Lys; in violet Asp, Glu, Gly, γ-amino-butyric acid, Pro, γ-Glu-Leu, Cy, and Leu; in yellow, Thr, α-amino-N-butyric acid, Tyr, and Phe; in green, γ-Glu-S-methyl-Cys, S-methyl-Cys, Me, and Ile; and in blue, O-acetylserine. Data on the y axis is the ratio of free amino acid concentration expressed in log2 scale (see Supplementary Fig. S2 at JXB online).

Discussion

In this study, global gene expression profiles were compared during seed development between two common bean genotypes, SARC1 and SMARC1N-PN1 differing in seed protein composition. The concentration of sulphur amino acids in mature seed is a major trait differentiating these two genotypes. The main objective was to investigate whether genes associated with sulphur metabolism are regulated transcriptionally, in order to identify genes and enzymes which may contribute to differences in Cys, Met, and S-methyl-Cys concentration. A secondary objective was to further identify the sulphur-rich proteins which accumulate additional Cys and Met in SMARC1N-PN1. The development of a common bean-specific high density array can be considered an improvement over a previous study relying on cross-species hybridization to a soybean array (Yang et al., 2010).

Transcripts of a fairly large number of contigs coding for sulphur-rich proteins had elevated levels in SMARC1N-PN1 and thus contributed to the increased concentration of Cys and Met. No fewer than eight protein types were involved, including the 11S globulin legumin, basic 7S globulin, albumin-2, defensin, albumin-1, the Bowman–Birk type proteinase inhibitor, the double-headed trypsin inhibitor, and the Kunitz trypsin inhibitor. Within each protein type, one or more genes were differentially expressed. For several of the sulphur-rich proteins, differential transcript expression was observed at the early stages, IV or V, and preceded that of sulphur metabolic enzymes, which happened exclusively at stages VI and VIII. This suggests that sulphur metabolism was regulated by demand from the protein sink.

The transcript profiling results highlight a remarkable co-ordination in the expression of sulphur metabolic genes, which includes those participating in sulphate transport and assimilation, de novo Cys biosynthesis, Met biosynthesis, and Met catabolism. The increased levels of Sultr1;2 and -3;3 transcripts in SMARC1N-PN1 are consistent with Arabidopsis studies implicating the high affinity sulphate transporter Sultr1;3 in phloem transport of sulphate (Yoshimoto et al., 2003), and low affinity group 3 sulphate transporters in the transport of sulphate from the seed coat to the embryo (Zuber et al., 2010). Sulphate uptake and assimilation share approximately equal control over cellular sulphur flux, according to the results of metabolic flux analysis (Vauclare et al., 2002). Transcripts for all three enzymes of sulphate assimilation were elevated in SMARC1N-PN1, but the most robust increases were observed for APSR1 and ATPS1 at stage VI. APSR is considered the major regulatory step in sulphate assimilation (Vauclare et al., 2002). However, in Arabidopsis, transcripts of ATPS can also be increased in response to sulphur deficiency (Logan et al., 1996). Moreover, recent results with T-DNA insertion mutants indicate that down-regulating expression of SIR can severely restrict sulphur flux (Khan et al., 2010). The large increase in transcript levels of SBP, whose expression is highly correlated with sulphate assimilatory genes in Arabidopsis (Hugouvieux et al., 2009), supports the conclusion that sulphate assimilation was activated in SMARC1N-PN1.

The fact that SERAT1;1 and -1;2 transcripts were increased in SMARC1N-PN1 and not those of OASS genes supports the view that SERAT activity, and therefore the supply of O-acetylserine, limits the rate of Cys biosynthesis, because OASS activity is actually present in large excess (Heeg et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis leaves, most O-acetylserine is synthesized by the mitochondrial SERAT2;2 isoform, whereas in siliques, cytosolic isoforms including SERAT1;1 were proposed to be responsible for O-acetylserine formation (Haas et al., 2008; Watanabe et al., 2008). Increased expression of SERAT1 genes in SMARC1N-PN1 suggests that the large increase in total Cys concentration in seed was achieved by an activation of cytosolic O-acetylserine biosynthesis. This subcellular compartmentation may explain why transgenic over-expression of cytosolic OASS increased total Cys concentration in soybean seed, whereas over-expression of plastidic SERAT had no effect on sulphur amino acid concentration in chickpea seed (Kim et al., 2012; Tabe et al., 2010). Common bean has a single SERAT2 isoform whose putative localization may be plastidic according to WoLFPSORT analysis. The reduced transcript levels of SERAT2;1 in SMARC1N-PN1 raises the intriguing possibility that this gene may regulate S-methyl-Cys biosynthesis. This hypothesis implies that S-methyl-Cys is formed by the condensation of O-acetylserine and methanethiol. This reaction is presumed to take place in Arabidopsis cells grown with excess Met, following its cleavage by Met γ-lyase (Rébeillé et al., 2006). If Cys and S-methyl-Cys biosynthesis share similar enzymes and a common precursor, O-acetylserine, their spatial separation within different subcellular compartments would provide a mechanism explaining their opposite regulation.

The fact that transcript levels of the Met biosynthetic enzyme, cystathionine γ-synthase (CGS) remained unchanged while CBL and HMT3 transcript levels were increased in SMARC1N-PN1 is surprising because CGS regulates flux in the Met pathway while downstream steps are not expected to exert control. Indeed, over-expression of CBL in transgenic potato did not result in an increased concentration of Met (Maimann et al., 2001). CGS shares a common substrate with Thr synthase, O-phosphohomoserine, and is thus located at a branch point with Thr biosynthesis in the Asp-derived amino acid pathway (Bartlem et al., 2000; Zeh et al., 2001). S-Adenosylmethionine acts as an allosteric activator of Thr synthase, effectively imposing a feedback on CGS (Curien et al., 1998). According to kinetic modelling, flux through the Met branch is very sensitive to the concentration of S-adenosylmethionine, more so than through the Thr branch (Curien et al., 2003, 2009). Modelling also predicts that flux through the Met branch is sensitive to the amount of CGS. The enzyme is fairly insensitive to changes in Cys concentration, due to its ping-pong mechanism whereby O-phosphohomoserine is bound as the first substrate. Post-transcriptional regulation of CGS by S-adenosylmethionine exerts a second type of slower control (Onoue et al., 2011). In accordance with the above kinetic model, transgenic expression of CGS in Arabidopsis led to an increased Met concentration, and even more so for a feedback-insensitive form (Hacham et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2002). However, over-expression of potato CGS did not lead to an increased Met concentration, and its transcript was insensitive to feedback from exogenous Met (Kreft et al., 2003). In the present study, since CGS transcript levels remained unchanged, one can predict that the concentration of S-adenosylmethionine may be decreased to allow enhanced flux through the Met pathway. The elevated levels of MGL1 transcripts suggest an increased demand for Met, which may be associated with a reduction in S-adenosylmethionine concentration. The increased levels of CBL and HMT3 transcripts observed in SMARC1N-PN1 possibly reflect the need to accommodate increased flux through the Met pathway.

In SMARC1N-PN1, the increase in total Met concentration, of 10%, is relatively small compared with that for total Cys, of 70% (Taylor et al., 2008). Nevertheless, a co-ordinate increase in transcript levels of the Met biosynthetic genes, CBL and HMT3 was observed. HMT is likely to be involved in the assimilation of S-methyl-Met transported to the seed (Bourgis et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2008). However, the fact that MGL1 transcripts were elevated raises the intriguing possibility that some of the sulphur taken up as S-methyl-Met is channelled into Cys biosynthesis. In Arabidopsis plants, radiolabelled sulphur from [35S]Met was incorporated into the Cys protein pool, and this was reduced but not abolished in an mgl knock-out mutant (Goyer et al., 2007). Arabidopsis MGL has been linked to Ile biosynthesis (Joshi and Jander, 2009). However, Ile demand is unlikely to regulate the MGL1 transcript in SMARC1N-PN1, since this genotype has lower levels of total Ile compared with SARC1 (Taylor et al., 2008). Increased levels of transcripts for two aminotransferases implicated in Met catabolism in other species also supports a possible Met to Cys pathway. In Arabidopsis, BCAT3 and -4 participate in the formation of α-ketomethylthiobutyric acid from Met as part of glucosinolate biosynthesis (Schuster et al., 2006; Knill et al., 2008). In bacteria and fungi, TAT is involved in the regeneration of Met from α-ketomethylthiobutyric acid in the Met salvage pathway (Pirkov et al., 2008) [Plant Metabolic Network (PMN), http://pmn.plantcyc.org/PLANT/NEW-IMAGE?type=NIL&object=PWY-4361-ARA&redirect=T">www.plantcyc.org">http://pmn.plantcyc.org/PLANT/NEW-IMAGE?type=NIL&object=PWY-4361-ARA&redirect=T on www.plantcyc.org 16 February 2012], while in lactic acid bacteria, it is the main enzyme responsible for the biosynthesis of α-ketomethylthiobutyric acid required for aroma formation (Rijnen et al., 2003; Sekowska et al., 2004).

In vegetative tissue, transcriptional regulation of sulphur uptake and assimilation by demand is a well-established concept, with feedback inhibition by glutathione, and stimulation by O-acetylserine (Lappartient et al., 1999; Neuenschwander et al., 1991). Exogenous application of O-acetylserine mimics the effects of sulphur deficiency, and transcript levels of sulphate transporters and sulphate assimilatory genes are increased in mutants accumulating O-acetylserine (Hirai et al., 2003; Ohkama-Ohtsu et al., 2004). O-Acetylserine acts as a signalling molecule leading to changes in gene expression, independent of fluctuations in other sulphur-related metabolites (Hubberten et al., 2012). In transgenic seeds expressing sunflower seed albumin, down-regulation of endogenous sulphur-rich proteins was associated with reduced levels of glutathione in rice (Hagan et al., 2003), and increased levels of O-acetylserine in chickpea (Chiaiese et al., 2004), both features associated with sulphur deficiency. In the present study, the high demand for Cys biosynthesis was correlated with reduced levels of O-acetylserine. Co-ordinate regulation of transcripts for most enzymatic steps emphasizes shared control over the metabolic flux of sulphur into Cys and Met, rather than the influence of a few key enzymatic steps (Stitt et al., 2010).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data can be found at JXB online.

Supplementary Table S1. Primers used for RT-quantitative PCR validation of differentially expressed genes.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Transcript profiles of genes coding for sulphur-rich proteins during seed development.

Supplementary Fig. S2. Free amino acid profiles in developing seeds of SARC1 and SMARC1N-PN1.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Genomics R&D Initiative of the Government of Canada, and the Ontario Research Fund, Research Excellence Program of the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation. DL was the recipient of a Visiting Fellowship in Canadian Government Laboratories of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. We thank Alex Molnar at the Southern Crop Protection and Food Research Centre for preparation of figures. We are grateful to staff at the Plant Biotechnology Institute, Don Schwab of the DNA Technologies Laboratory for array design and synthesis, and Yongguo Cao and Daoquan Xiang for technical assistance with array hybridization and imaging. We acknowledge the help of Rey Interior at the Advanced Protein Technology Centre, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, with amino acid analysis.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Alb

albumin

- AI

amylase inhibitor

- AIL

amylase inhibitor-like; ANOVA, analysis of variance

- Arc

arcelin

- aRNA

amplified RNA

- ATPS

sulphate adenylyltransferase

- APSR

adenylyl sulphate reductase

- BCAT

branched chain amino acid aminotransferase

- CBL

cystathionine β-lyase

- CGS

cystathionine γ-synthase

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- HMT

homocysteine S-methyltransferase

- Lec

lectin

- MGL

Met γ-lyase

- OASS

O-acetylserine sulphhydrylase

- Pha

phytohaemagglutinin

- Pha-L

leucoagglutinating phytohaemagglutinin

- Phs

phaseolin

- SBP

selenium binding protein

- SERAT

Ser acetyltransferase

- SIR

sulphite reductase

- Sultr

sulphate transporter

- TAT

Tyr aminotransferase.

References

- Anderson JW, Fitzgerald MA. 2001. Physiological and metabolic origin of sulphur for the synthesis of seed storage proteins Journal of Plant Physiology 158 447–456 [Google Scholar]

- Aragao FJL, Barros LMG, de Sousa MV, de Sa MFG, Almeida ERP, Gander ES, Rech EL. 1999. Expression of a methionine-rich storage albumin from the Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa HBK, Lecythidaceae) in transgenic bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L., Fabaceae) Genetics and Molecular Biology 22 445–449 [Google Scholar]

- Bartlem D, Lambein I, Okamoto T, Itaya A, Uda Y, Kijima F, Tamaki Y, Nambara E, Naito S. 2000. Mutation in the threonine synthase gene results in an over-accumulation of soluble methionine in Arabidopsis Plant Physiology 123 101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb AJ, Eiben HG, Bustos MM. 1995. PvAlf, an embryo-specific acidic transcriptional activator enhances gene expression from phaseolin and phytohemagglutinin promoters The Plant Journal 8 331–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgis F, Roje S,, Nuccio ML, et al. 1999. S-Methylmethionine plays a major role in phloem sulfur transport and is synthesized by a novel type of methyltransferase The Plant Cell 11 1485–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton WJ, Hernandez G, Blair M, Beebe S, Gepts P, Vanderleyden J. 2003. Beans (Phaseolus spp.): model food legumes Plant and Soil 252 55–128 [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau L, Chapman R, Marsolais F. 2006. Co-occurrence of both L-asparaginase subtypes in Arabidopsis: At3g16150 encodes a K+-dependent L-asparaginase Planta 224 668–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaiese P, Ohkama , Ohtsu N, Molvig L, Godfree R, Dove H, Hocart C, Fujiwara T, Higgins TJ, Tabe LM. 2004. Sulphur and nitrogen nutrition influence the response of chickpea seeds to an added, transgenic sink for organic sulphur Journal of Experimental Botany 55 1889–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curien G, Bastien O, Robert , Genthon M, Cornish , Bowden A, Cardenas ML, Dumas R. Understanding the regulation of aspartate metabolism using a model based on measured kinetic parameters. Molecular Systems Biology. 2009;5:271. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curien G, Job D, Douce R, Dumas R. 1998. Allosteric activation of Arabidopsis threonine synthase by S-adenosylmethionine Biochemistry 37 13212–13221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curien G, Ravanel S, Dumas R. 2003. A kinetic model of the branch-point between the methionine and threonine biosynthesis pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana European Journal of Biochemistry 270 4615–4627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidov D, Horstmann C, Meixner M, Pickardt T, Saalbach I, Galili G, Muentz K. 2003. Additive effects of the feed-back insensitive bacterial aspartate kinase and the Brazil nut 2S albumin on the methionine content of transgenic narbon bean (Vicia narbonensis L.) Molecular Breeding 11 187–201 [Google Scholar]

- Dinkins RD, Reddy MSS, Meurer CA, Yan B, Trick H, Thibaud , Nissen F, Finer JJ, Parrott WA, Collins GB. 2001. Increased sulfur amino acids in soybean plants overexpressing the maize 15kDa zein protein. In vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology-Plant 37 742–747 [Google Scholar]

- Galili G, Amir R,, Hoefgen R, Hesse H. 2005. Improving the levels of essential amino acids and sulfur metabolites in plants Biological Chemistry 386 817–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giada MDR, Teresa M, Miranda M, Marquez UML. 1998. Sulphur gamma-glutamyl peptides in mature seeds of common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Food Chemistry 61 177–184 [Google Scholar]

- Goyer A, Collakova E, Shachar , Hill Y, Hanson AD. 2007. Functional characterization of a methionine gamma-lyase in Arabidopsis and its implication in an alternative to the reverse trans-sulfuration pathway Plant and Cell Physiology 48 232–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Delcher AL, Mount SM, et al. 2003. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies Nucleic Acids Research 31 5654–5666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas FH, Heeg C, Queiroz R, Bauer A, Wirtz M, Hell R. 2008. Mitochondrial serine acetyltransferase functions as a pacemaker of cysteine synthesis in plant cells Plant Physiology 148 1055–1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacham Y, Matityahu I, Schuster G, Amir R. 2008. Overexpression of mutated forms of aspartate kinase and cystathionine gamma-synthase in tobacco leaves resulted in the high accumulation of methionine and threonine The Plant Journal 54 260–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan ND, Upadhyaya N, Tabe LM, Higgins TJV. 2003. The redistribution of protein sulfur in transgenic rice expressing a gene for a foreign, sulfur-rich protein The Plant Journal 34 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada K, Hirano H. 2004. Interaction of a 43-kDa receptor-like protein with a 4-kDa hormone-like peptide in soybean Biochemistry 43 12105–12112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeg C, Kruse C, Jost R,, Gutensohn M, Ruppert T,, Wirtz M, Hell R. 2008. Analysis of the Arabidopsis O-acetylserine(thiol)lyase gene family demonstrates compartment-specific differences in the regulation of cysteine synthesis The Plant Cell 20 168–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hell R,, Wirtz M. 2011. Molecular biology, biochemistry and cellular physiology of cysteine metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana The Arabidopsis Book 9, e0154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai MY, Fujiwara T,, Awazuhara M, Kimura T, Noji M, Saito K. 2003. Global expression profiling of sulfur-starved Arabidopsis by DNA macroarray reveals the role of O-acetyl-L-serine as a general regulator of gene expression in response to sulfur nutrition The Plant Journal 33 651–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N,, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, Nakai K. 2007. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor Nucleic Acids Research 35 W585–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Frizzi A, Malvar TM. 2009. Engineering high lysine corn. In: Krishnan H, ed. Modification of seed composition to promote health and nutrition Madison: American Society of Agronomy, Crop Science Society of America, Soil Science Society of America; 233–248 [Google Scholar]

- Hubberten HM, Klie S,, Caldana C, Degenkolbe T, Willmitzer L,, Hoefgen R. 2012. Additional role of O-acetylserine as a sulfur status-independent regulator during plant growth The Plant Journal 70 666–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugouvieux V, Dutilleul C, Jourdain A, Reynaud F, Lopez V, Bourguignon J. 2009. Arabidopsis putative selenium-binding protein1 expression is tightly linked to cellular sulfur demand and can reduce sensitivity to stresses requiring glutathione for tolerance Plant Physiology 151 768–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi V, Jander G. 2009. Arabidopsis methionine γ-lyase is regulated according to isoleucine biosynthesis needs but plays a subordinate role to threonine deaminase Plant Physiology 151 367–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JD,, Hefle SL. 2000. 2S methionine-rich protein (SSA) from sunflower seed is an IgE-binding protein Allergy 55 556–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MS, Haas FH, Samami AA, et al. 2010. Sulfite reductase defines a newly discovered bottleneck for assimilatory sulfate reduction and is essential for growth and development in Arabidopsis thaliana The Plant Cell 22 1216–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lee M, Chalam R, Martin MN, Leustek T, Boerjan W. 2002. Constitutive overexpression of cystathionine gamma-synthase in Arabidopsis leads to accumulation of soluble methionine and S-methylmethionine Plant Physiology 128 95–107 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WS, Chronis D, Juergens M, Schroeder AC, Hyun SW, Jez JM, Krishnan HB. 2012. Transgenic soybean plants overexpressing O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase accumulate enhanced levels of cysteine and Bowman–Birk protease inhibitor in seeds Planta 235 13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WS, Krishnan HB. 2004. Expression of an 11kDa methionine-rich delta-zein in transgenic soybean results in the formation of two types of novel protein bodies in transitional cells situated between the vascular tissue and storage parenchyma cells Plant Biotechnology Journal 2 199–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knill T, Schuster J, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, Binder S. 2008. Arabidopsis branched-chain aminotransferase 3 functions in both amino acid and glucosinolate biosynthesis Plant Physiology 146 1028–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft O, Hoefgen R, Hesse H. 2003. Functional analysis of cystathionine gamma-synthase in genetically engineered potato plants Plant Physiology 131 1843–1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappartient AG, Vidmar JJ, Leustek T, Glass AD, Touraine B. 1999. Inter-organ signaling in plants: regulation of ATP sulfurylase and sulfate transporter genes expression in roots mediated by phloem-translocated compound The Plant Journal 18 89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Huang TF, Toro , Ramos T, Fraga M, Last RL, Jander G. 2008. Reduced activity of Arabidopsis thaliana HMT2, a methionine biosynthetic enzyme, increases seed methionine content The Plant Journal 54 310–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Yoo B-C, Lee J-Y,, Pan W, Harmon AC. 2006. Calcium-regulated phosphorylation of soybean serine acetyltransferase in response to oxidative stress Journal of Biological Chemistry 281 27405–27415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan HM, Cathala N, Grignon C, Davidian JC. 1996. Cloning of a cDNA encoded by a member of the Arabidopsis thaliana ATP sulfurylase multigene family. Expression studies in yeast and in relation to plant sulfur nutrition Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 12227–12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovati MR, Manzoni C, Castiglioni S, Parolari A, Magni C, Duranti M. 2012. Lupin seed γ-conglutin lowers blood glucose in hyperglycaemic rats and increases glucose consumption of HepG2 cells British Journal of Nutrition 107 67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magni C, Sessa F, Accardo E, Vanoni M, Morazzoni P, Scarafoni A, Duranti M. 2004. Conglutin γ, a lupin seed protein, binds insulin in vitro and reduces plasma glucose levels of hyperglycemic rats Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 15 646–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimann S, Hoefgen R, Hesse H. 2001. Enhanced cystathionine beta-lyase activity in transgenic potato plants does not force metabolite flow towards methionine Planta 214 163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsolais F, Pajak A, Yin F, et al. 2010. Proteomic analysis of common bean seed with storage protein deficiency reveals up-regulation of sulfur-rich proteins and starch and raffinose metabolic enzymes, and down-regulation of the secretory pathway Journal of Proteomics 73 1587–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molvig L, Tabe LM, Eggum BO, Moore AE, Craig S, Spencer D, Higgins TJ. 1997. Enhanced methionine levels and increased nutritive value of seeds of transgenic lupins (Lupinus angustifolius L.) expressing a sunflower seed albumin gene Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 94 8393–8398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeve SL, Shibles RM. 2005. Distribution and mobilization of sulfur during soybean reproduction Crop Science 45 2540–2551 [Google Scholar]

- Neuenschwander U, Suter M, Brunold C. 1991. Regulation of sulfate assimilation by light and O-acetyl-L-serine in Lemna minor L Plant Physiology 97 253–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noji M, Inoue K, Kimura N, Gouda A, Saito K. 1998. Isoform-dependent differences in feedback regulation and subcellular localization of serine acetyltransferase involved in cysteine biosynthesis from Arabidopsis thaliana Journal of Biological Chemistry 273 32739–32745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlee JA, Taylor SL, Townsend JA, Thomas LA, Bush RK. 1996. Identification of a Brazil-nut allergen in transgenic soybeansNew England Journal of Medicine 334 688–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkama , Ohtsu N, Kasajima I, Fujiwara T, Naito S. 2004. Isolation and characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant that overaccumulates O-acetyl-L-Ser Plant Physiology 136 3209–3222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoue N, Yamashita Y, Nagao N, Goto DB, Onouchi H, Naito S. 2011. S-Adenosyl-L-methionine induces compaction of nascent peptide chain inside the ribosomal exit tunnel upon translation arrest in the Arabidopsis CGS1 gene Journal of Biological Chemistry 286 14903–14912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn TC, Hartweck LM, Harmsen RH, Vogelzang RD, Kmiecik KA, Bliss FA. 2003. Registration of Phaseolus vulgaris genetic stocks with altered seed protein compositions Crop Science 43 1570–1571 [Google Scholar]

- Padovese R, Kina SM, Barros RMC, Borelli P, Marquez UML. 2001. Biological importance of gamma-glutamyl-S-methylcysteine of kidney bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Food Chemistry 73 291–297 [Google Scholar]

- Pertea G, Huang X, Liang F, et al. 2003. TIGR Gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets Bioinformatics 19 651–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkov I, Norbeck J, Gustafsson L, Albers E. 2008. A complete inventory of all enzymes in the eukaryotic methionine salvage pathway FEBS Journal 275 4111–4120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polesani M, Bortesi L, Ferrarini A, Zamboni A, Fasoli M, Zadra C, Lovato A, Pezzotti M, Delledonne M, Polverari A. General and species-specific transcriptional responses to downy mildew infection in a susceptible (Vitis vinifera) and a resistant (V. riparia) grapevine species. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rébeillé F, Jabrin S, Bligny R, Loizeau K, Gambonnet B, Van Wilder V, Douce R, Ravanel S. 2006. Methionine catabolism in Arabidopsis cells is initiated by a gamma-cleavage process and leads to S-methylcysteine and isoleucine syntheses Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 103 15687–15692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijnen L, Yvon M, Kranenburg Rv, Courtin P, Verheul A, Chambellon E, Smit G. 2003. Lactococcal aminotransferases AraT and BcaT are key enzymes for the formation of aroma compounds from amino acids in cheese International Dairy Journal 13 805–812 [Google Scholar]

- Scarafoni A, Ronchi A, Duranti M. 2010. γ-Conglutin, the Lupinus albus XEGIP-like protein, whose expression is elicited by chitosan, lacks of the typical inhibitory activity against GH12 endo-glucanases Phytochemistry 71 142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster J, Knill T, Reichelt M, Gershenzon J, Binder S. 2006. BRANCHED-CHAIN AMINOTRANSFERASE4 is part of the chain elongation pathway in the biosynthesis of methionine-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis The Plant Cell 18 2664–2679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekowska A, Denervaud V, Ashida H, Michoud K, Haas D, Yokota A, Danchin A. Bacterial variations on the methionine salvage pathway. BMC Microbiology. 2004;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M, Sulpice R, Keurentjes J. 2010. Metabolic networks: how to identify key components in the regulation of metabolism and growth Plant Physiology 152 428–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit LG, Beach LR, Register JC, Jung R, Fehr WR. 2001. Association of the Brazil nut protein gene and Kunitz trypsin inhibitor alleles with soybean protease inhibitor activity and agronomic traits Crop Science 41 1757–1760 [Google Scholar]

- Tabe L, Wirtz M, Molvig L, Droux M, Hell R. 2010. Overexpression of serine acetlytransferase produced large increases in O-acetylserine and free cysteine in developing seeds of a grain legume Journal of Experimental Botany 61 721–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabe LM, Droux M. 2001. Sulfur assimilation in developing lupin cotyledons could contribute significantly to the accumulation of organic sulfur reserves in the seed Plant Physiology 126 176–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabe LM, Droux M. 2002. Limits to sulfur accumulation in transgenic lupin seeds expressing a foreign sulfur-rich protein Plant Physiology 128 1137–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kopriva S, Giordano M, Saito K, Hell R. 2011. Sulfur assimilation in photosynthetic organisms: molecular functions and regulations of transporters and assimilatory enzymes Annual Review of Plant Biology 62 157–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Q, Zhang L, Grant J, Cooper P, Tegeder M. 2010. Increased phloem transport of S-methylmethionine positively affects sulfur and nitrogen metabolism and seed development in pea plants Plant Physiology 154 1886–1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M, Chapman R, Beyaert R, Hernández , Sebastià C, Marsolais F. 2008. Seed storage protein deficiency improves sulfur amino acid content in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): redirection of sulfur from gamma-glutamyl-S-methyl-cysteine Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 56 5647–5654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend JA, Thomas LA. 1994. Factors which influence the Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of soybean Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. Supplement 18A 78 [Google Scholar]

- Vauclare P, Kopriva S, Fell D, Suter M, Sticher L, von Ballmoos P, Krahenbuhl U, den Camp RO, Brunold C. 2002. Flux control of sulphate assimilation in Arabidopsis thaliana: adenosine 5’-phosphosulphate reductase is more susceptible than ATP sulphurylase to negative control by thiols The Plant Journal 31 729–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walbot V, Clutter M, Sussex IM. 1972. Reproductive development and embryogeny in Phaseolus Phytomorphology 22 59–68 [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Mochida K, Kato T, Tabata S, Yoshimoto N, Noji M, Saito K. 2008. Comparative genomics and reverse genetics analysis reveal indispensable functions of the serine acetyltransferase gene family in Arabidopsis The Plant Cell 20 2484–2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO 2007. Protein and amino acid requirements in human nutrition Report of a joint FAO/WHO/UNU expert consultation. Geneva: WHO; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SS, Valdes-Lopez O, Xu WW, Bucciarelli B, Gronwald JW, Hernandez G, Vance CP. Transcript profiling of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) using the GeneChip soybean genome array: optimizing analysis by masking biased probes. BMC Plant Biology. 2010;10:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi H, Ravilious GE, Galant A, Krishnan HB, Jez JM. 2010. From sulfur to homoglutathione: thiol metabolism in soybean Amino Acids 39 963–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F, Pajak A, Chapman R, Sharpe A, Huang S, Marsolais F. Analysis of common bean expressed sequence tags identifies sulfur metabolic pathways active in seed and sulfur-rich proteins highly expressed in the absence of phaseolin and major lectins. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:268. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto N, Inoue E, Saito K, Yamaya T, Takahashi H. 2003. Phloem-localizing sulfate transporter, Sultr1;3, mediates re-distribution of sulfur from source to sink organs in Arabidopsis Plant Physiology 131 1511–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa T, Shimizu T, Yamabe M, Taichi M, Nishiuchi Y, Shichijo N, Unzai S, Hirano H, Sato M, Hashimoto H. 2011. Crystal structure of basic 7S globulin, a xyloglucan-specific endo-β-1,4-glucanase inhibitor protein-like protein from soybean lacking inhibitory activity against endo-β-glucanase FEBS Journal 278 1944–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeh M, Casazza AP, Kreft O, Roessner U, Bieberich K, Willmitzer L, Hoefgen R, Hesse H. 2001. Antisense inhibition of threonine synthase leads to high methionine content in transgenic potato plants Plant Physiology 127 792–802 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Dreher K, Karthikeyan A, et al. 2010. Creation of a genome-wide metabolic pathway database for Populus trichocarpa using a new approach for reconstruction and curation of metabolic pathways for plants Plant Physiology 153 1479–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber H, Davidian JC, Aubert G, et al. 2010. The seed composition of arabidopsis mutants for the group 3 sulfate transporters indicates a role in sulfate translocation within developing seeds Plant Physiology 154 913–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.