Abstract

SIRT1, a type III protein deacetylase, is considered as a novel anti-aging protein involved in regulation of cellular senescence/aging and inflammation. SIRT1 level and activity are decreased during lung inflammaging caused by oxidative stress. The mechanism of SIRT1-mediated protection against inflammaging is associated with the regulation of inflammation, premature senescence, telomere attrition, senescence associated secretory phenotype, and DNA damage response. A variety of dietary polyphenols and pharmacological activators are shown to regulate SIRT1 so as to intervene the progression of type 2 diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with inflammaging. However, recent studies have shown the non-specific regulation of SIRT1 by the aforementioned pharmacological activators and polyphenols. In this perspective, we have briefly discussed the role of SIRT1 in regulation of cellular senescence and its associated secretory phenotype, DNA damage response, particularly in lung inflammaging and during the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. We have also discussed the potential directions for future translational therapeutic avenues for SIRT1 in modulating lung inflammaging associated with senescence in chronic lung diseases associated with increased oxidative stress.

Keywords: SIRT1, inflammation, cellular senescence, telomere attrition, senescence associated secretory phenotype, DNA damage and repair

Introduction

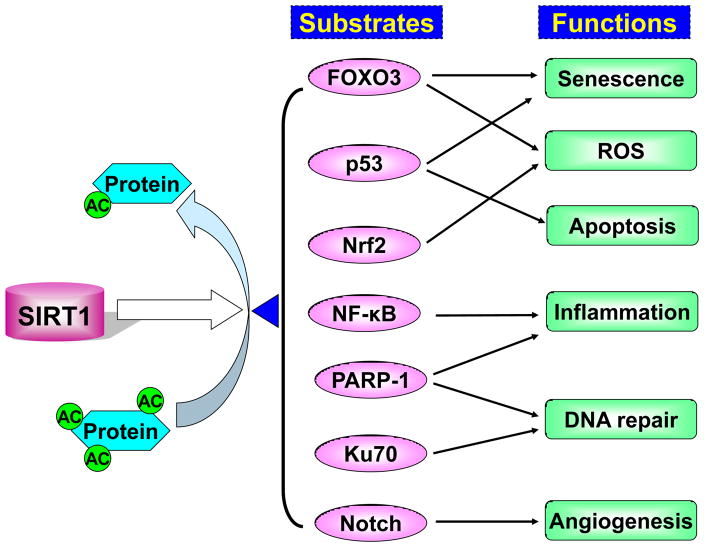

Sirtuin1 (SIRT1), a type III histone deacetylase, requires NAD+ as a cofactor to remove the acetyl moieties from the ε-acetamido groups of lysine residues of histones and other signaling proteins, thus facilitating chromatin condensation and silencing of gene transcription. SIRT1 regulates a variety of signaling pathways involved in metabolism, inflammation, cellular senescence, proliferation, apoptosis, and DNA damage response (DDR), due to its ability to deacetylate forkhead box class O (FOXO)3, NF-κB, p53, Werner syndrome protein, Klotho, β-catenin/Wnt, Notch, PARP-1, and histones [1–3] (Figure 1). This suggests the involvement of SIRT1 in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Indeed, five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of SIRT1 are identified in a population-based study, indicating its variability in the human population [4, 5]. However, it remains unknown whether SNPs or allelic variants of SIRT1 is a susceptibility factor for the development of these diseases associated with inflammaging that characterized by aging accompanying with a low-grade chronic inflammation. In this review, we have discussed the role of SIRT1 in inflammaging in translational research and its pharmacological activators in intervening chronic diseases with lung inflammation and senescence.

Figure 1. SIRT1 regulates protein acetylation and deacetylation in inflammaging.

SIRT1 removes the acetyl moieties from the ε-acetamido groups of lysine residues of proteins that include FOXO3, p53, Nrf2, NF-κB, PARP-1, Ku70 and Notch. The acetylation and deacetylation of these proteins alter their transcriptional and enzymatic activities, as well as protein levels, thereby regulating cellular senescence, apoptosis, inflammation, ROS production, DNA damage and repair, and angiogenesis. All these cellular processes are involved in the inflammaging that occurs in aging-associated diseases such as COPD, diabetes, and cancer.

SIRT1 and premature senescence

SIRT1 is considered a novel anti-aging protein involved in regulation of cell senescence and premature aging. The levels of SIRT1 are decreased in senescent mouse embryonic fibroblasts as well as in lung epithelial cells, human endothelial cells and macrophages exposed to oxidants [6–11]. We and others have shown that SIRT1 also exhibits an age-dependent reduction in rodents [12–14]. Mice deficient in SIRT1 are smaller and age faster than their wild-type littermates [15]. SIRT1 protects against endothelial dysfunction by preventing stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS), thereby modulating endothelial dysfunction in the progression of cardiovascular diseases [16–20]. Genetic overexpression of SIRT1 protects against SIPS in the lungs, which is an important contributing factor for the development of COPD [12]. The mechanism for SIRT1-mediated protection against cellular senescence is due to the regulation of a redox-sensitive transcription factor FOXO3, since SIRT1 activation by a pharmacological activator SRT1720 has no effect on increased lung cellular senescence and emphysema in FOXO3 knockout mice [12]. It is interesting to note that SIRT1 also represses FOXO transcriptional activity, suggesting their cell- and/or FOXO isoform-specific roles in regulating senescence and angiogenesis as well as cell cycle arrest under certain conditions of stress [21, 22]. The levels of p21 and p16 are significantly increased in mice deficient in SIRT1 or FOXO3 in response to cigarette smoke [12]. Moreover, deletion of pro-senescent gene p21 protected against cigarette smoke-induced cellular senescence in lung cells and subsequent pulmonary emphysema in mice [12, 23]. These findings are in agreement with the association among increased acetylation and degradation of FOXO3, increased p21 expression, as well as SIRT1 reduction in lungs of COPD patients [12, 24–26]. Indeed, a link between cellular senescence and premature lung aging has been proposed in the pathogenesis of COPD [27–33]. Cigarette smoke induces senescence in lung epithelial cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells in vitro [34–40]. The involvement of cellular senescence in the pathogenesis of emphysema has been shown in various studies using genetically altered mouse strains [12, 41–43]. Therefore, the study of SIRT1/FOXO3/p21 signaling will provide more insights in tipping the imbalance of cellular senescence towards proliferation in lung cells during inflammaging caused by cigarette smoke and oxidants. Furthermore, it remains to be known whether the clearance of p21 or p16 positive senesced cells using a newly developed p16-INK technique protects against oxidative stress-induced lung inflammaging and subsequent emphysema [44]. It is also unknown which cells preferentially first undergo cellular senescence which thereby can trigger a cascade of senescence phenotype of neighboring cells in the lungs.

Apart from FOXO3, several other protein substrates for SIRT1, which are involved in cell stress response signaling and cellular senescence, have been identified. This includes Ku70/Ku80, Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, and Werner syndrome protein [45–49] (Figure 1). A recent study has identified XRCC5/Ku80 as a potential COPD-susceptibility gene through the multi-study fine-mapping strategy [50]. Indeed, the Ku80 knockout mice develop early aging [51]. Hence, further studies on these molecules in a condition of oxidative stress/cigarette smoke will enhance the understanding of lung inflammaging and cellular senescence in the pathogenesis of COPD.

SIRT1 in telomere attrition

SIRT1 has been shown to prevent telomere shortening, which is a susceptible factor for developing emphysema [52–54]. Indeed, the telomere length is shortened in blood cells, alveolar macrophages, pulmonary vascular endothelial cells, and lung epithelial cells of patients with COPD [38, 55–60]. Furthermore, telomere exhaustion/attrition leads to cellular senescence in vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, which plays an important role in pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis and pulmonary hypertension [61–64]. The mechanism underlying the protection of SIRT1 against telomere attrition and replicative senescence is due to the regulation in the gene transcription of telomerase reverse transcriptase, which is used as a template for elongating telomeres [65]. Telomere length can also be maintained through alternative mechanisms in the absence of telomerase activity. Hence, another possibility is that SIRT1 modulates histone acetylation/deacetylation (e.g., H3K9 and H3K56), as well as the recruitment of PARP-1 and Ku70/Ku80 at telomere chromatin, thereby maintaining the telomeric integrity [53, 66–68] (Figure 1). However, it remains to be seen whether SIRT1 protects against oxidant/cigarette smoke-induced telomere attrition and shortening during lung inflammaging.

SIRT1 and senescence associated secretory phenotype/inflammation

The senescent cells are prone to secrete pro-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-6, IL-8 and MMPs, which are dependent on NF-κB activation. This phenomenon refers to senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [69, 70]. Indeed, increased RelA/p65 phosphorylation was increased in p16-positive senescent cells in lungs of COPD patients as compared to smokers [37]. SIRT1 interacts with RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB, and deacetylates its lys310 residue, a site that is critical for NF-κB transcriptional activity [71, 72] (Figure 1). We have shown that cigarette smoke-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokine release is reduced by SIRT1 via deacetylating RelA/p65 in monocytes and mouse lung, as well as in smokers and patients with COPD [9, 10, 24]. Both sirtinol (an inhibitor of SIRT1) and SIRT1 knockdown augmented, whereas SRT1720 (a potent SIRT1 activator) inhibited cigarette smoke-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokine release [9, 24, 25]. SIRT1 genetic overexpression or activation by a pharmacological activator SRT1720 attenuated cigarette smoke-induced NF-κB activation and lung inflammation [12]. However, the treatment of NF-κB inhibitor had no effect on lung cellular senescence or airspace enlargement in mouse with emphysema [12]. This suggests that SIRT1 protects against emphysema via reducing lung cellular senescence, independently of NF-κB-dependent inflammation. Further study is required to investigate whether other signals, such as CXCR2-mediated inflammatory pathway reinforce cellular senescence during lung premature aging [73]. It would be interesting to determine whether SIRT1 activation reverses cellular senescence during lung inflammaging.

SIRT1 and DDR

Cigarette smoke causes DNA damage and impairs double-strand break (DSB) repair, which is aggravated in patients with COPD/emphysema [74–79]. Recent studies have shown that persistent DNA damage causes SIPS and SASP [70, 80]. Thus, cigarette smoke-mediated DNA damage may be one of the important mechanisms in initiating and maintaining SIPS and SASP. In response to DNA damage, SIRT1 can relocalize to the damaged sites and promote DNA repair via deacetylating DNA repair proteins, such as Ku70, NBS, Werner helicase, and nibrin [47, 68, 81–83] (Figure 1). Indeed, the increased acetylation of Ku70 caused by oxidative and genotoxic stress reduces its DNA-binding affinity during DNA repair. Further study is required to determine whether Ku70 and other DNA repair proteins undergo acetylation/deacetylation under oxidative stress imposed by cigarette smoke, and if SIRT1 has any effect on their posttranslational modification status and ability to bind the damaged DNA with its repair proteins.

SIRT1 interacts with PARP-1 and reduces its acetylation that is required for full NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activity [84]. PARP-1 is an important signal that activates DNA repair programs, and PARP-1/NF-κB signaling cascade is activated during cellular senescence [85, 86]. Therefore, it is possible that SIRT1 regulates SIPS and SASP via PARP-1-dependent mechanisms on DDR and telomere function in response to cigarette smoke/oxidants. This contention requires further studies to translate the findings of SIRT1 regulation in replicative senescence in pathogenesis of COPD which is associated with lung inflammaging.

SIRT1 and histone modifications in inflammaging

Histone modifications play an important role in regulating DNA damage/repair, pro-inflammatory gene transcription, genomic instability, and premature aging [87–91]. Histone methylation at H3K79 and H4K20 recruits 53BP1 and Crb2 to DNA damage foci after DSB induction [92–95]. Moreover, H3K36 dimethylation has been shown to increase the rate of the association of Ku70 and NBS1 with DSB sites [96, 97]. Furthermore, H3K79 dimethylation is required for ionizing radiation-induced 53BP1 foci formation when H4K20 dimethylation is low [95, 98], suggesting the cross-talk of histone acetylation and methylation regulate DDR. Opening, repairing, and closing of chromatin occur in order to repair the damaged DNA [99]. Hence, these histone acetylation and methylation after DNA damage will alter chromatin status between euchromatin and heterochromatin so as to recruit DNA repair factors and cofactors (e.g., HP1) to damaged sites. SIRT1 also deacetylates histone H3K56, thereby regulating DNA damage and genomic instability [90, 91]. This may be due to SIRT1-mediated transcriptional repression, which prevents transcription from interfering with the repair process. Histone methylation (e.g., H3K9me3) can also be regulated by SIRT1 via deacetylating Suv39h1, or enabling histone H3 toward Suv39h1 [100]. However, studies are required to determine which histone residue(s) are modified and how these modifications affect genomic stability, DNA damage repair, and subsequent cellular senescence. SIRT1 is regulated by several miRNAs, such as miR-34 and miR-22, which are involved in cellular senescence via histone modifications [101–103]. It also remains to be seen if cigarette smoke-induced SIRT1 reduction alters histone acetylation and methylation, as well as their cross-talks with histone modifications and DNA methylation, thereby regulating DDR and cellular senescence. Furthermore, pharmacological activation of SIRT1 may ameliorate histone modifications and intervene formation of senescence associated with heterochromatin foci (SAHF) in inflammaging.

SIRT1 and oxidative stress in inflammaging

Apart from the posttranslational modifications by oxidative stress [10], SIRT1 itself protects against oxidative stress by up-regulating FOXO3-dependent antioxidant genes (i.e., catalase and MnSOD) [104–108]. A recent study has shown that SIRT1 can deacetylate Nrf2, a master regulator of the cellular redox state, thereby decreasing Nrf2 transcriptional activity and nucleo-cytoplasmic localization in human cancer line [109] (Figure 1). However, it remains elusive whether SIRT1 (direct replenishment of NAD+ or via activation of AMPK) protects against oxidative stress via regulating Nrf2 acetylation and deacetylation in primary cells during aging [109, 110]. Oxidative stress and inflammation are key events in premature aging, and both play an important role in the development of COPD/emphysema [111–113]. Hence, it is likely that SIRT1 activation ameliorates lung inflammaging via down-regulating oxidative stress-mediated cellular senescence.

SIRT1 and lung stem/progenitor cells

The level of SIRT1 is higher in embryonic stem cells than that in differentiated tissues [114]. SIRT1 is required for the long-term growth of human mesenchymal stem cells, whereas its cleavage causes SIPS in endothelial progenitor cells [115, 116]. SIRT1 deficiency in the embryonic cells leads to embryonic and developmental abnormalities including defects in the formation of the primitive vascular network, which may be due to the regulation of developmental genes, such as NANOG and Notch [46, 117–119]. SIRT1 is known to regulate endothelial function via eNOS acetylation/deacetylation [8]. Increased loss of endothelial cells occurs in progression of COPD/emphysema [120]. It has been shown that endothelial progenitor cells (EPC), which promote revascularization (angiogenesis), are senesced in response to high levels of glucose which is seen in patients with diabetes, due to SIRT1 reduction [21, 115, 121]. Hence, it will be interesting to see if SIRT1 regulates lung tissue regeneration via angiogenesis by increasing the function of EPCs or induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells-derived EPCs. COPD represents a disease with premature aging and cellular senescence in Clara cells and type II epithelial cells, which are the progenitor cells of airway and alveolar epithelium. We found that SIRT1 deletion in Clara cells renders mice susceptible to the development of pulmonary emphysema associated with increased lung cellular senescence [12]. A recent study has shown that human lung contains stem cells [122]. Therefore, the regulation of SIRT1 in lung stem/progenitor cells or iPS-EPCs would be a promising therapeutic avenue in the treatment of COPD and its comorbid cardiovascular diseases.

There are cancer stem cells (CSCs) in lungs of patients with lung tumor, which has the ability to form colonies and develop region-specific lung cancers [123]. Furthermore, EPCs control the angiogenic switch in mouse lung metastasis, suggesting selective inhibition of EPCs may be beneficial for cancer patients with lung metastases [124]. However, it remains to be known whether SIRT1 regulates these CSCs and EPCs in lung tumorigenesis and metastases, despite the SIRT1 function is abnormal in lung cancer [125].

SIRT1 activation by dietary polyphenols and pharmacological activators

Resveratrol

Resveratrol, a phytoalexin found in the skin and seeds of grapes, has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Since 2003, resveratrol was identified as a potent SIRT1 activator and mimicked the effect of calorie restriction in regulating longevity in yeast, worms, flies, and short-lived fishes, as well as in mice [126–134] (Table 1). However, the beneficial effects of activation of SIRT1 in higher mammals are lacking. In obese humans, one month of resveratrol supplementation also induces metabolic changes, mimicking the effect of calorie restriction [135]. This is in part due to the effect of resveratrol on cellular senescence and inflammation via activating SIRT1 [136–138]. A recent study has shown that SIRT1 may not increase the longevity in C. elegans and drosophila [139], which cast doubts on whether resveratrol is an actual activator of SIRT1. Indeed, resveratrol increases SIRT1 deacetylase activity only when the deacetylated protein substrates have a fluorophore attached, whereas substrates lacking the fluorophore did not show increased deacetylation by resveratrol [140]. These findings suggest that resveratrol is not a direct activator of SIRT1 [140–142]. This is confirmed by the studies that resveratrol indirectly regulates SIRT1 via activating nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) and cAMP-Epac1-AMP-activated kinase (AMPK), leading to an increase in intracellular level of NAD+ [143–149]. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase (PDE)4 (elevation of intracellular cAMP) reproduces all of the metabolic benefits of resveratrol, which is due to an increase in intracellular levels of cAMP leading to AMPK and subsequent SIRT1 activation [149]. Furthermore, AMPK activation induces the disassociation of SIRT1 from its endogenous inhibitor deleted in breast cancer-1 (DBC1), thereby activating SIRT1 [150–152]. It remains to see whether resveratrol has any effect on the association of SIRT1 with DBC1. Furthermore, treatment with resveratrol has no effect or reduced SIRT1 levels during oxidative stress [153, 154], suggesting the controversial ‘beneficial’ role of resveratrol in inflammaging. Nevertheless, resveratrol does delay or attenuate the progression of age-associated disease model in rodents [155]. Further studies are required to investigate if resveratrol inhibits inflammation and cellular senescence via the involvement of SIRT1 in specific lung cells including stem cells.

Table 1.

Putative SIRT1 activators in inflammaging

| Putative activator | Potency to activate SIRT1 | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols | |||

| Resveratrol | Increases SIRT1 activity up to 8-fold (EC1.5 = 46.2 μM) | Delays the progression of aging-associated diseases Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects |

[155, 158] |

| Quercetin | Increases SIRT1 activity up to 2-fold | Prevents the progression of emphysema | [156, 158] |

| EGCG | Increases SIRT1 activity up to 1.6-fold | Reduces lung inflammation | [158, 186] |

| Pharmacological activators | |||

| SRT1720 | EC1.5=0.16 μM in increasing SIRT1 activity | Protects against lung inflammaging Extends lifespan of adult mice |

[12, 171] |

| SRT2172 | EC50=0.136 μM in increasing SIRT1 activity | Inhibits MMP-9 production | [25] |

| Metformin | Increases SIRT1 activity up to 1.2-fold | Suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis | [173] |

Quercetin and other polyphenols

Quercetin, 3,3′,4′,5,7-pentahydroxylflavone, is a plant-derived flavonol found in apples, tea, capers, and onion. It has been shown that quercetin protects against emphysema, which is associated with the increased expression of SIRT1 [156] (Table 1). This is in agreement with the previous reports that quercetin and catechins activate mammalian SIRT1 or yeast Sir2 [126, 157, 158]. Other polyphenolic compounds, such as butein, quercetin, piceatannol, and myrcetin, can also activate SIRT1 [159]. These compounds have a modest ability to activate SIRT1 ranging from 3.19–8.53 fold as compared to resveratrol. Nevertheless, these polyphenols may be beneficial in regulation of lung inflammaging through SIRT1 [160]. Interestingly, some polyphenols, such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and quercetin, did not exhibit any ability to activate SIRT1 (perhaps do not lower the Km for NAD+) in a variety of cellular systems [158, 161, 162]. On the contrary, these polyphenols inhibit SIRT1 activity [158]. This is due to their instability leading to formation of oxidized form of polyphenols to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the medium in particular their reactions with aldehydes/quinones (via resveratrol, EGCG) or due to SIRT1-inhibitory metabolites (i.e. via quercetin and its metabolites) [158].

Sulforaphane

We and others have shown that SIRT1 undergoes posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation, carbonylation, nitrosylation and S-glutathionylation by oxidative/carbonyl stress [8, 10, 163–165]. Increasing cellular NAD+ levels by PARP-1 inhibition or NAD+ precursors was unable to restore the loss of SIRT1 activity caused by cigarette smoke, due to oxidative/carbonyl posttranslational modifications of SIRT1 [163]. Sulforaphane, an activator Nrf2, may indirectly restore SIRT1 activity by reversing oxidative/carbonyl modifications of SIRT1 via activation of phase II detoxifying/antioxidant enzymes (aldehyde/carbonyl reductases, thioredoxin reductases) in primary cells, although sulforaphane decreases the total activity of HDAC in vivo [166]. Therefore, the studies are required to attest this functional activity of SIRT1 by dietary natural products including Nrf2 activators.

Pharmacological compounds

Several SIRT1 activators, which are analogs of resveratrol, have been developed for the treatment of aging-associated diseases including type 2 diabetes [167–169]. These activators include SRT1720, SRT1460, SRT2183, SRT2104, SRT2172, and SRT2379 (Table 1). The most potent of the compounds is SRT1720 (EC1.5 = 0.16 μM and maximum activation of SIRT1 of 781%), which is 800–1000 fold more effective than resveratrol in activating SIRT1 [168]. SRT2172 is more effective in inhibiting MMP-9 production in monocytes as compared to resveratrol [25]. This may be via activation of TIMPs (TIMP-1) via its acetylation/deacetylation. The efficiency of these SIRT1 activators is strongly dependent on structural features of the peptide and probably on allosteric regulation [141, 170]. SRT1720 improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in animal models of type 2 diabetes [168]. We found that SRT1720 treatment reduces cigarette smoke-induced lung cellular senescence due to SIRT1 activation. Consequently, the lung inflammatory response and airspace enlargement were significantly improved by SRT1720 administration [12]. In addition, SRT1720 improves survival and healthspan of obese mice [171], suggesting the feasibility of designing novel molecules that are safe and effective in promoting longevity and preventing multiple age-related diseases in mammals. As above described, SRT1720, SRT2183, and SRT1460 are non-specific for SIRT1 activation [141]. Therefore, the development of a specific selective pharmacological SIRT1 activator is crucial in understanding the role of SIRT1 in cellular functions and potential clinical application of SIRT1 activators in diseases associated with lung inflammaging.

Other SIRT1 modulators

SIRT1 requires NAD+ as a cofactor in deacetylating substrates. Theophylline prevents NAD+ depletion [172]. PARP-1 activation drains cellular NAD+, which compromises SIRT1 activity. Hence, theophylline or PARP-1 inhibitor would maintain intracellular NAD+ pool, thereby activating SIRT1. A recent study has shown that there is no alteration of SIRT1 activity after PARP-1 inhibitor treatment in the condition of oxidative stress, which is due to SIRT1 carbonylation and oxidation [11, 163]. Hence, the reversal of SIRT1 posttranslational modifications, such as carbonylation and oxidation, would be important before the pharmacological activation of SIRT in regulating lung inflammaging.

Metformin is a widely used drug especially for adult onset type 2 diabetes. A recent study has demonstrated that the beneficial effect of metformin is associated with the activation and induction of SIRT1 [173] (Table 1). Further studies revealed that metformin targets AMPK, an upstream kinase for activating SIRT1 [173–177]. The effectiveness and mechanism of metformin in lung inflammaging/senescence is remains elusive, although several clinical trials are ongoing to study the effect of metformin in treatment of COPD and its exacerbations.

Translational impact

SIRT1 exhibits an age-dependent reduction. It is also reduced in aging-associated diseases, such as COPD and diabetes. A variety of pharmacological and dietary compounds, such as resveratrol and SRT1720, are shown to target SIRT1 in order to delay inflammaging or attenuate the progression of aging-associated diseases. However, recent studies have revealed that most of the above dietary compounds are non-specific activators of SIRT1. Hence, the development of specific and selective SIRT1 activator is urgently required to delay or ameliorate the progression of lung inflammaging.

Conclusions and future directions

SIRT1 regulates cellular senescence/premature aging, inflammation, stress resistance, and apoptosis/autophagy via deacetylating transcription factors (e.g., FOXO3), signaling molecules (e.g., PARP-1), and histones. However, a recent study revealed that there is no effect of SIRT1 on longevity in C elegans and drosophila [139], which cast a doubt on beneficial role of SIRT1 activation in human aging and aging-associated diseases. It has been shown that SIRT6 also regulates cellular senescence, aging, inflammation, and DDR [178–183]. However, it remains to be seen whether there is an overlapping function between SIRT1 and SIRT6 in regulating lung inflammaging. It would also be interesting to determine if SIRT1 and other histone deacetylases have differential roles in regulating premature and replicative senescence during the progression of COPD. The involvement of specific cell types in cellular senescence and their regulation by SIRT1 in the lung is not known. The development of SIRT1 or SIRT6 activity by dietary polyphenols, specific activators (e.g., SRT1720), or AMP-activated protein kinase activators (e.g., AICAR) is a promising therapeutic strategy against senescence/aging-associated diseases associated with lung inflammaging (e.g., COPD, cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases) [25, 184, 185]. It is also important to study how these dietary polyphenols and putative pharmacological activators activate SIRT1, and to develop the direct and specific SIRT1 activators. In addition, most of the polyphenols are poorly absorbed and rapidly metabolized as well as oxidized, which affect their regulation in SIRT1 function. Hence, further study is required to study the biochemical mode of action of dietary polyphenols on SIRT1 activation and in modulation of senescence in inflammaging.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NIH 1R01HL085613, 1R01HL097751, 1R01HL092842, and NIEHS Environmental Health Science Center grant P30-ES01247.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Finkel T, Deng CX, Mostoslavsky R. Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature. 2009;460:587–91. doi: 10.1038/nature08197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavu S, Boss O, Elliott PJ, Lambert PD. Sirtuins--novel therapeutic targets to treat age-associated diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:841–53. doi: 10.1038/nrd2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michan S, Sinclair D. Sirtuins in mammals: insights into their biological function. Biochem J. 2007;404:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flachsbart F, Croucher PJ, Nikolaus S, Hampe J, Cordes C, Schreiber S, et al. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) sequence variation is not associated with exceptional human longevity. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zillikens MC, van Meurs JB, Sijbrands EJ, Rivadeneira F, Dehghan A, van Leeuwen JP, et al. SIRT1 genetic variation and mortality in type 2 diabetes: interaction with smoking and dietary niacin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:836–41. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orimo M, Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Tateno K, Okada S, Moriya J, et al. Protective role of SIRT1 in diabetic vascular dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:889–94. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.185694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki T, Maier B, Bartke A, Scrable H. Progressive loss of SIRT1 with cell cycle withdrawal. Aging Cell. 2006;5:413–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arunachalam G, Yao H, Sundar IK, Caito S, Rahman I. SIRT1 regulates oxidant- and cigarette smoke-induced eNOS acetylation in endothelial cells: Role of resveratrol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang SR, Wright J, Bauter M, Seweryniak K, Kode A, Rahman I. Sirtuin regulates cigarette smoke-induced proinflammatory mediator release via RelA/p65 NF-kappaB in macrophages in vitro and in rat lungs in vivo: implications for chronic inflammation and aging. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L567–76. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00308.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caito S, Rajendrasozhan S, Cook S, Chung S, Yao H, Friedman AE, et al. SIRT1 is a redox-sensitive deacetylase that is post-translationally modified by oxidants and carbonyl stress. FASEB J. 2010;24:3145–59. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-151308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang JW, Chung S, Sundar IK, Yao H, Arunachalam G, McBurney MW, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced autophagy is regulated by SIRT1-PARP-1-dependent mechanism: implication in pathogenesis of COPD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;500:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao H, Chung S, Hwang JW, Rajendrasozhan S, Sundar IK, Dean DA, et al. SIRT1 protects against emphysema via FOXO3-mediated reduction of premature senescence in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2032–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI60132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braidy N, Guillemin GJ, Mansour H, Chan-Ling T, Poljak A, Grant R. Age related changes in NAD+ metabolism oxidative stress and Sirt1 activity in wistar rats. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 14.Quintas A, de Solis AJ, Diez-Guerra FJ, Carrascosa JM, Bogonez E. Age-associated decrease of SIRT1 expression in rat hippocampus: prevention by late onset caloric restriction. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47:198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McBurney MW, Yang X, Jardine K, Hixon M, Boekelheide K, Webb JR, et al. The mammalian SIR2alpha protein has a role in embryogenesis and gametogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:38–54. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.38-54.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ota H, Akishita M, Eto M, Iijima K, Kaneki M, Ouchi Y. Sirt1 modulates premature senescence-like phenotype in human endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:571–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman I, Kinnula VL, Gorbunova V, Yao H. SIRT1 as a therapeutic target in inflammaging of the pulmonary disease. Prev Med. 2012;54 (Suppl):S20–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadtochiy SM, Yao H, McBurney MW, Gu W, Guarente L, Rahman I, et al. SIRT1-mediated acute cardioprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1506–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00587.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Zhang HN, Chen HZ, Gao P, Zhu LH, Li HL, et al. SIRT1 acts as a modulator of neointima formation following vascular injury in mice. Circ Res. 2011;108:1180–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein S, Matter CM. Protective roles of SIRT1 in atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:640–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.4.14863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potente M, Ghaeni L, Baldessari D, Mostoslavsky R, Rossig L, Dequiedt F, et al. SIRT1 controls endothelial angiogenic functions during vascular growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2644–58. doi: 10.1101/gad.435107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motta MC, Divecha N, Lemieux M, Kamel C, Chen D, Gu W, et al. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116:551–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao H, Yang SR, Edirisinghe I, Rajendrasozhan S, Caito S, Adenuga D, et al. Disruption of p21 attenuates lung inflammation induced by cigarette smoke, LPS, and fMLP in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:7–18. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0342OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajendrasozhan S, Yang SR, Kinnula VL, Rahman I. SIRT1, an antiinflammatory and antiaging protein, is decreased in lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:861–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1269OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamaru Y, Vuppusetty C, Wada H, Milne JC, Ito M, Rossios C, et al. A protein deacetylase SIRT1 is a negative regulator of metalloproteinase-9. FASEB J. 2009;23:2810–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-125468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang JW, Rajendrasozhan S, Yao H, Chung S, Sundar IK, Huyck HL, et al. FOXO3 deficiency leads to increased susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced inflammation, airspace enlargement, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol. 2011;187:987–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Senescence hypothesis for the pathogenetic mechanism of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:596–601. doi: 10.1513/pats.200904-017RM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernhard D, Moser C, Backovic A, Wick G. Cigarette smoke--an aging accelerator? Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fukuchi Y. The aging lung and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: similarity and difference. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:570–2. doi: 10.1513/pats.200909-099RM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karrasch S, Holz O, Jorres RA. Aging and induced senescence as factors in the pathogenesis of lung emphysema. Respir Med. 2008;102:1215–30. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee J, Sandford A, Man P, Sin DD. Is the aging process accelerated in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:90–7. doi: 10.1097/mcp.0b013e328341cead. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacNee W. Accelerated lung aging: a novel pathogenic mechanism of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:819–23. doi: 10.1042/BST0370819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuder RM, Kern JA, Miller YE. Senescence in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9:62–3. doi: 10.1513/pats.201201-012MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller KC, Welker L, Paasch K, Feindt B, Erpenbeck VJ, Hohlfeld JM, et al. Lung fibroblasts from patients with emphysema show markers of senescence in vitro. Respir Res. 2006;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nyunoya T, Monick MM, Klingelhutz A, Yarovinsky TO, Cagley JR, Hunninghake GW. Cigarette smoke induces cellular senescence. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:681–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0169OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nyunoya T, Monick MM, Klingelhutz AL, Glaser H, Cagley JR, Brown CO, et al. Cigarette smoke induces cellular senescence via Werner’s syndrome protein down-regulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:279–87. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-320OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Alveolar cell senescence exacerbates pulmonary inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2010;80:59–70. doi: 10.1159/000268287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Alveolar cell senescence in patients with pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:886–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1374OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuji T, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Cigarette smoke induces senescence in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:643–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0290OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minamino T, Miyauchi H, Yoshida T, Ishida Y, Yoshida H, Komuro I. Endothelial cell senescence in human atherosclerosis: role of telomere in endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2002;105:1541–4. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013836.85741.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee J, Reddy R, Barsky L, Scholes J, Chen H, Shi W, et al. Lung alveolar integrity is compromised by telomere shortening in telomerase-null mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L57–70. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90411.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato T, Seyama K, Sato Y, Mori H, Souma S, Akiyoshi T, et al. Senescence marker protein-30 protects mice lungs from oxidative stress, aging, and smoking. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:530–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1816OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suga T, Kurabayashi M, Sando Y, Ohyama Y, Maeno T, Maeno Y, et al. Disruption of the klotho gene causes pulmonary emphysema in mice. Defect in maintenance of pulmonary integrity during postnatal life. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:26–33. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.1.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, et al. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature. 2011;479:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holloway KR, Calhoun TN, Saxena M, Metoyer CF, Kandler EF, Rivera CA, et al. SIRT1 regulates Dishevelled proteins and promotes transient and constitutive Wnt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9216–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911325107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guarani V, Deflorian G, Franco CA, Kruger M, Phng LK, Bentley K, et al. Acetylation-dependent regulation of endothelial Notch signalling by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Nature. 2011;473:234–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uhl M, Csernok A, Aydin S, Kreienberg R, Wiesmuller L, Gatz SA. Role of SIRT1 in homologous recombination. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:383–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li K, Casta A, Wang R, Lozada E, Fan W, Kane S, et al. Regulation of WRN protein cellular localization and enzymatic activities by SIRT1-mediated deacetylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7590–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaitiekunaite R, Butkiewicz D, Krzesniak M, Przybylek M, Gryc A, Snietura M, et al. Expression and localization of Werner syndrome protein is modulated by SIRT1 and PML. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:650–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hersh CP, Pillai SG, Zhu G, Lomas DA, Bakke P, Gulsvik A, et al. Multistudy fine mapping of chromosome 2q identifies XRCC5 as a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease susceptibility gene. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:605–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200910-1586OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vogel H, Lim DS, Karsenty G, Finegold M, Hasty P. Deletion of Ku86 causes early onset of senescence in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10770–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palacios JA, Herranz D, De Bonis ML, Velasco S, Serrano M, Blasco MA. SIRT1 contributes to telomere maintenance and augments global homologous recombination. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:1299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201005160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim S, Bi X, Czarny-Ratajczak M, Dai J, Welsh DA, Myers L, et al. Telomere maintenance genes SIRT1 and XRCC6 impact age-related decline in telomere length but only SIRT1 is associated with human longevity. Biogerontology. 2012;13:119–31. doi: 10.1007/s10522-011-9360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alder JK, Guo N, Kembou F, Parry EM, Anderson CJ, Gorgy AI, et al. Telomere length is a determinant of emphysema susceptibility. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:904–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0520OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee J, Sandford AJ, Connett JE, Yan J, Mui T, Li Y, et al. The Relationship between Telomere Length and Mortality in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) PLoS One. 2012;7:e35567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amsellem V, Gary-Bobo G, Marcos E, Maitre B, Chaar V, Validire P, et al. Telomere dysfunction causes sustained inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1358–66. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0802OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savale L, Chaouat A, Bastuji-Garin S, Marcos E, Boyer L, Maitre B, et al. Shortened telomeres in circulating leukocytes of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:566–71. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1398OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Houben JM, Mercken EM, Ketelslegers HB, Bast A, Wouters EF, Hageman GJ, et al. Telomere shortening in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2009;103:230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morla M, Busquets X, Pons J, Sauleda J, MacNee W, Agusti AG. Telomere shortening in smokers with and without COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:525–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00087005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tomita K, Caramori G, Ito K, Lim S, Sano H, Tohda Y, et al. Telomere shortening in alveolar macrophages of smokers and COPD patients. Open Path. 2010;4:23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fuster JJ, Andres V. Telomere biology and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2006;99:1167–80. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000251281.00845.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kovacic JC, Moreno P, Hachinski V, Nabel EG, Fuster V. Cellular senescence, vascular disease, and aging: part 1 of a 2-part review. Circulation. 2011;123:1650–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.007021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jane-Wit D, Chun HJ. Mechanisms of dysfunction in senescent pulmonary endothelium. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:236–41. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fyhrquist F, Saijonmaa O. Telomere length and cardiovascular aging. Ann Med. 2012;44 (Suppl 1):S138–42. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2012.660497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yamashita S, Ogawa K, Ikei T, Udono M, Fujiki T, Katakura Y. SIRT1 prevents replicative senescence of normal human umbilical cord fibroblast through potentiating the transcription of human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417:630–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salvati E, Scarsella M, Porru M, Rizzo A, Iachettini S, Tentori L, et al. PARP1 is activated at telomeres upon G4 stabilization: possible target for telomere-based therapy. Oncogene. 2010;29:6280–93. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Michishita E, McCord RA, Boxer LD, Barber MF, Hong T, Gozani O, et al. Cell cycle-dependent deacetylation of telomeric histone H3 lysine K56 by human SIRT6. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2664–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jeong J, Juhn K, Lee H, Kim SH, Min BH, Lee KM, et al. SIRT1 promotes DNA repair activity and deacetylation of Ku70. Exp Mol Med. 2007;39:8–13. doi: 10.1038/emm.2007.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133:1019–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Munoz DP, Raza SR, et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:973–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen LF, Mu Y, Greene WC. Acetylation of RelA at discrete sites regulates distinct nuclear functions of NF-kappaB. EMBO J. 2002;21:6539–48. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR, Frye RA, et al. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004;23:2369–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Acosta JC, O’Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133:1006–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aoshiba K, Zhou F, Tsuji T, Nagai A. Dna damage as a molecular link in the pathogensis of copd in smokers. Eur Respir J. 2012 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Caramori G, Adcock IM, Casolari P, Ito K, Jazrawi E, Tsaprouni L, et al. Unbalanced oxidant-induced DNA damage and repair in COPD: a link towards lung cancer. Thorax. 2011;66:521–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.156448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ceylan E, Kocyigit A, Gencer M, Aksoy N, Selek S. Increased DNA damage in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who had once smoked or been exposed to biomass. Respir Med. 2006;100:1270–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deslee G, Adair-Kirk TL, Betsuyaku T, Woods JC, Moore CH, Gierada DS, et al. Cigarette smoke induces nucleic-acid oxidation in lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;43:576–84. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0221OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Deslee G, Woods JC, Moore C, Conradi SH, Gierada DS, Atkinson JJ, et al. Oxidative damage to nucleic acids in severe emphysema. Chest. 2009;135:965–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pastukh VM, Zhang L, Ruchko MV, Gorodnya O, Bardwell GC, Tuder RM, et al. Oxidative DNA damage in lung tissue from patients with COPD is clustered in functionally significant sequences. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:209–17. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S15922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rodier F, Munoz DP, Teachenor R, Chu V, Le O, Bhaumik D, et al. DNA-SCARS: distinct nuclear structures that sustain damage-induced senescence growth arrest and inflammatory cytokine secretion. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:68–81. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yuan Z, Seto E. A functional link between SIRT1 deacetylase and NBS1 in DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2869–71. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.23.5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gorospe M, de Cabo R. AsSIRTing the DNA damage response. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yuan Z, Zhang X, Sengupta N, Lane WS, Seto E. SIRT1 regulates the function of the Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein. Mol Cell. 2007;27:149–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rajamohan SB, Pillai VB, Gupta M, Sundaresan NR, Birukov KG, Samant S, et al. SIRT1 promotes cell survival under stress by deacetylation-dependent deactivation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4116–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00121-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Woodhouse BC, Dianov GL. Poly ADP-ribose polymerase-1: an international molecule of mystery. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:1077–86. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ohanna M, Giuliano S, Bonet C, Imbert V, Hofman V, Zangari J, et al. Senescent cells develop a PARP-1 and nuclear factor-{kappa}B-associated secretome (PNAS) Genes Dev. 2011;25:1245–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.625811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Krishnan V, Chow MZ, Wang Z, Zhang L, Liu B, Liu X, et al. Histone H4 lysine 16 hypoacetylation is associated with defective DNA repair and premature senescence in Zmpste24-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102789108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ogiwara H, Ui A, Otsuka A, Satoh H, Yokomi I, Nakajima S, et al. Histone acetylation by CBP and p300 at double-strand break sites facilitates SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling and the recruitment of non-homologous end joining factors. Oncogene. 2011;30:2135–46. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sarg B, Koutzamani E, Helliger W, Rundquist I, Lindner HH. Postsynthetic trimethylation of histone H4 at lysine 20 in mammalian tissues is associated with aging. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39195–201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205166200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vempati RK, Jayani RS, Notani D, Sengupta A, Galande S, Haldar D. p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 functions in DNA damage response in mammals. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28553–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.149393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yuan J, Pu M, Zhang Z, Lou Z. Histone H3-K56 acetylation is important for genomic stability in mammals. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1747–53. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Botuyan MV, Lee J, Ward IM, Kim JE, Thompson JR, Chen J, et al. Structural basis for the methylation state-specific recognition of histone H4-K20 by 53BP1 and Crb2 in DNA repair. Cell. 2006;127:1361–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huyen Y, Zgheib O, Ditullio RA, Jr, Gorgoulis VG, Zacharatos P, Petty TJ, et al. Methylated lysine 79 of histone H3 targets 53BP1 to DNA double-strand breaks. Nature. 2004;432:406–11. doi: 10.1038/nature03114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sanders SL, Portoso M, Mata J, Bahler J, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Methylation of histone H4 lysine 20 controls recruitment of Crb2 to sites of DNA damage. Cell. 2004;119:603–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wakeman TP, Wang Q, Feng J, Wang XF. Bat3 facilitates H3K79 dimethylation by DOT1L and promotes DNA damage-induced 53BP1 foci at G1/G2 cell-cycle phases. EMBO J. 2012 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fnu S, Williamson EA, De Haro LP, Brenneman M, Wray J, Shaheen M, et al. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 36 enhances DNA repair by nonhomologous end-joining. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:540–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013571108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wagner EJ, Carpenter PB. Understanding the language of Lys36 methylation at histone H3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:115–26. doi: 10.1038/nrm3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Latham JA, Dent SY. Cross-regulation of histone modifications. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1017–24. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Palomera-Sanchez Z, Zurita M. Open, repair and close again: chromatin dynamics and the response to UV-induced DNA damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10:119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vaquero A, Scher M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Serrano L, Reinberg D. SIRT1 regulates the histone methyl-transferase SUV39H1 during heterochromatin formation. Nature. 2007;450:440–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yamakuchi M. MicroRNA Regulation of SIRT1. Front Physiol. 2012;3:68. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee J, Kemper JK. Controlling SIRT1 expression by microRNAs in health and metabolic disease. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:527–34. doi: 10.18632/aging.100184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ito T, Yagi S, Yamakuchi M. MicroRNA-34a regulation of endothelial senescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;398:735–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Alcendor RR, Gao S, Zhai P, Zablocki D, Holle E, Yu X, et al. Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2007;100:1512–21. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000267723.65696.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tanno M, Kuno A, Yano T, Miura T, Hisahara S, Ishikawa S, et al. Induction of manganese superoxide dismutase by nuclear translocation and activation of SIRT1 promotes cell survival in chronic heart failure. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8375–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kops GJ, Dansen TB, Polderman PE, Saarloos I, Wirtz KW, Coffer PJ, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress. Nature. 2002;419:316–21. doi: 10.1038/nature01036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.He W, Wang Y, Zhang MZ, You L, Davis LS, Fan H, et al. Sirt1 activation protects the mouse renal medulla from oxidative injury. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1056–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI41563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vinciguerra M, Santini MP, Martinez C, Pazienza V, Claycomb WC, Giuliani A, et al. mIGF-1/JNK1/SirT1 signaling confers protection against oxidative stress in the heart. Aging Cell. 2012;11:139–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kawai Y, Garduno L, Theodore M, Yang J, Arinze IJ. Acetylation-deacetylation of the transcription factor Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) regulates its transcriptional activity and nucleocytoplasmic localization. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7629–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.208173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sun Z, Chin YE, Zhang DD. Acetylation of Nrf2 by p300/CBP augments promoter-specific DNA binding of Nrf2 during the antioxidant response. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2658–72. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01639-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, Zhen L, Srisuma SS, Kensler TW, et al. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1248–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI21146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yoshida T, Mett I, Bhunia AK, Bowman J, Perez M, Zhang L, et al. Rtp801, a suppressor of mTOR signaling, is an essential mediator of cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary injury and emphysema. Nat Med. 2010;16:767–73. doi: 10.1038/nm.2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Carmeli E, Imam B, Bachar A, Merrick J. Inflammation and oxidative stress as biomarkers of premature aging in persons with intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Saunders LR, Sharma AD, Tawney J, Nakagawa M, Okita K, Yamanaka S, et al. miRNAs regulate SIRT1 expression during mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation and in adult mouse tissues. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:415–31. doi: 10.18632/aging.100176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chen J, Xavier S, Moskowitz-Kassai E, Chen R, Lu CY, Sanduski K, et al. Cathepsin cleavage of sirtuin 1 in endothelial progenitor cells mediates stress-induced premature senescence. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:973–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Yuan HF, Zhai C, Yan XL, Zhao DD, Wang JX, Zeng Q, et al. SIRT1 is required for long-term growth of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Mol Med (Berl) 2012;90:389–400. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ou X, Chae HD, Wang RH, Shelley WC, Cooper S, Taylor T, et al. SIRT1 deficiency compromises mouse embryonic stem cell hematopoietic differentiation, and embryonic and adult hematopoiesis in the mouse. Blood. 2011;117:440–50. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-273011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mantel C, Broxmeyer HE. Sirtuin 1, stem cells, aging, and stem cell aging. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:326–31. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283043819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Han MK, Song EK, Guo Y, Ou X, Mantel C, Broxmeyer HE. SIRT1 regulates apoptosis and Nanog expression in mouse embryonic stem cells by controlling p53 subcellular localization. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kasahara Y, Tuder RM, Cool CD, Lynch DA, Flores SC, Voelkel NF. Endothelial cell death and decreased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:737–44. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2002117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Balestrieri ML, Rienzo M, Felice F, Rossiello R, Grimaldi V, Milone L, et al. High glucose downregulates endothelial progenitor cell number via SIRT1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:936–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kajstura J, Rota M, Hall SR, Hosoda T, D’Amario D, Sanada F, et al. Evidence for human lung stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1795–806. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 123.Wu X, Chen H, Wang X. Can lung cancer stem cells be targeted for therapies? Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:580–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gao D, Nolan DJ, Mellick AS, Bambino K, McDonnell K, Mittal V. Endothelial progenitor cells control the angiogenic switch in mouse lung metastasis. Science. 2008;319:195–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1150224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tseng RC, Lee CC, Hsu HS, Tzao C, Wang YC. Distinct HIC1-SIRT1-p53 loop deregulation in lung squamous carcinoma and adenocarcinoma patients. Neoplasia. 2009;11:763–70. doi: 10.1593/neo.09470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–42. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell. 2006;127:1109–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, et al. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430:686–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Agarwal B, Baur JA. Resveratrol and life extension. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1215:138–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bass TM, Weinkove D, Houthoofd K, Gems D, Partridge L. Effects of resveratrol on lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:546–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Valenzano DR, Terzibasi E, Genade T, Cattaneo A, Domenici L, Cellerino A. Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and retards the onset of age-related markers in a short-lived vertebrate. Curr Biol. 2006;16:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Pearson KJ, Baur JA, Lewis KN, Peshkin L, Price NL, Labinskyy N, et al. Resveratrol delays age-related deterioration and mimics transcriptional aspects of dietary restriction without extending life span. Cell Metab. 2008;8:157–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sun C, Zhang F, Ge X, Yan T, Chen X, Shi X, et al. SIRT1 improves insulin sensitivity under insulin-resistant conditions by repressing PTP1B. Cell Metab. 2007;6:307–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Timmers S, Konings E, Bilet L, Houtkooper RH, van de Weijer T, Goossens GH, et al. Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 2011;14:612–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Tang Y, Xu J, Qu W, Peng X, Xin P, Yang X, et al. Resveratrol reduces vascular cell senescence through attenuation of oxidative stress by SIRT1/NADPH oxidase-dependent mechanisms. J Nutr Biochem. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Price NL, Gomes AP, Ling AJ, Duarte FV, Martin-Montalvo A, North BJ, et al. SIRT1 Is Required for AMPK Activation and the Beneficial Effects of Resveratrol on Mitochondrial Function. Cell Metab. 2012;15:675–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhang S, Cai G, Fu B, Liu W, Zhuo L, Sun L, et al. SIRT1 is required for the effects of rapamycin on high glucose-inducing mesangial cells senescence. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Burnett C, Valentini S, Cabreiro F, Goss M, Somogyvari M, Piper MD, et al. Absence of effects of Sir2 overexpression on lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila. Nature. 2011;477:482–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Borra MT, Smith BC, Denu JM. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17187–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Pacholec M, Bleasdale JE, Chrunyk B, Cunningham D, Flynn D, Garofalo RS, et al. SRT1720, SRT2183, SRT1460, and resveratrol are not direct activators of SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8340–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Beher D, Wu J, Cumine S, Kim KW, Lu SC, Atangan L, et al. Resveratrol is not a direct activator of SIRT1 enzyme activity. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74:619–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Suchankova G, Nelson LE, Gerhart-Hines Z, Kelly M, Gauthier MS, Saha AK, et al. Concurrent regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase and SIRT1 in mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;378:836–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.11.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mukherjee S, Lekli I, Gurusamy N, Bertelli AA, Das DK. Expression of the longevity proteins by both red and white wines and their cardioprotective components, resveratrol, tyrosol, and hydroxytyrosol. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:573–8. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hou X, Xu S, Maitland-Toolan KA, Sato K, Jiang B, Ido Y, et al. SIRT1 regulates hepatocyte lipid metabolism through activating AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20015–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802187200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Um JH, Park SJ, Kang H, Yang S, Foretz M, McBurney MW, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase-deficient mice are resistant to the metabolic effects of resveratrol. Diabetes. 2010;59:554–63. doi: 10.2337/db09-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Fulco M, Cen Y, Zhao P, Hoffman EP, McBurney MW, Sauve AA, et al. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Dev Cell. 2008;14:661–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, Noriega L, Milne JC, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–60. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Park SJ, Ahmad F, Philp A, Baar K, Williams T, Luo H, et al. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. Cell. 2012;148:421–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Escande C, Chini CC, Nin V, Dykhouse KM, Novak CM, Levine J, et al. Deleted in breast cancer-1 regulates SIRT1 activity and contributes to high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:545–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI39319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kang H, Suh JY, Jung YS, Jung JW, Kim MK, Chung JH. Peptide switch is essential for Sirt1 deacetylase activity. Mol Cell. 2011;44:203–13. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Nin V, Escande C, Chini CC, Giri S, Camacho-Pereira J, Matalonga J, et al. Role of deleted in breast cancer 1 (DBC1) in SIRT1 activation induced by protein kinase A and AMP activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.365874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Pizarro JG, Verdaguer E, Ancrenaz V, Junyent F, Sureda F, Pallas M, et al. Resveratrol inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells: role of sirtuin 1. Neurochem Res. 2011;36:187–94. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0296-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Chang J, Rimando A, Pallas M, Camins A, Porquet D, Reeves J, et al. Low-dose pterostilbene, but not resveratrol, is a potent neuromodulator in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Canto C, Auwerx J. Targeting sirtuin 1 to improve metabolism: all you need is NAD(+)? Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:166–87. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Ganesan S, Faris AN, Comstock AT, Chattoraj SS, Chattoraj A, Burgess JR, et al. Quercetin prevents progression of disease in elastase/LPS-exposed mice by negatively regulating MMP expression. Respir Res. 2010;11:131. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Davis JM, Murphy EA, Carmichael MD, Davis B. Quercetin increases brain and muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and exercise tolerance. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1071–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90925.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.de Boer VC, de Goffau MC, Arts IC, Hollman PC, Keijer J. SIRT1 stimulation by polyphenols is affected by their stability and metabolism. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127:618–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Chung S, Yao H, Caito S, Hwang JW, Arunachalam G, Rahman I. Regulation of SIRT1 in cellular functions: role of polyphenols. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;501:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Celik H, Arinc E. Evaluation of the protective effects of quercetin, rutin, naringenin, resveratrol and trolox against idarubicin-induced DNA damage. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2010;13:231–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Choi KC, Jung MG, Lee YH, Yoon JC, Kwon SH, Kang HB, et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a histone acetyltransferase inhibitor, inhibits EBV-induced B lymphocyte transformation via suppression of RelA acetylation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:583–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Feng Y, Wu J, Chen L, Luo C, Shen X, Chen K, et al. A fluorometric assay of SIRT1 deacetylation activity through quantification of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. Anal Biochem. 2009;395:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Caito S, Hwang JW, Chung S, Yao H, Sundar IK, Rahman I. PARP-1 inhibition does not restore oxidant-mediated reduction in SIRT1 activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;392:264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Zee RS, Yoo CB, Pimentel DR, Perlman DH, Burgoyne JR, Hou X, et al. Redox regulation of sirtuin-1 by S-glutathiolation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:1023–32. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Flick F, Luscher B. Regulation of sirtuin function by posttranslational modifications. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:1. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Myzak MC, Dashwood WM, Orner GA, Ho E, Dashwood RH. Sulforaphane inhibits histone deacetylase in vivo and suppresses tumorigenesis in Apc-minus mice. FASEB J. 2006;20:506–8. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4785fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Bemis JE, Vu CB, Xie R, Nunes JJ, Ng PY, Disch JS, et al. Discovery of oxazolo[4,5-b]pyridines and related heterocyclic analogs as novel SIRT1 activators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:2350–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Milne JC, Lambert PD, Schenk S, Carney DP, Smith JJ, Gagne DJ, et al. Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;450:712–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Vu CB, Bemis JE, Disch JS, Ng PY, Nunes JJ, Milne JC, et al. Discovery of imidazo[1,2-b]thiazole derivatives as novel SIRT1 activators. J Med Chem. 2009;52:1275–83. doi: 10.1021/jm8012954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Dai H, Kustigian L, Carney D, Case A, Considine T, Hubbard BP, et al. SIRT1 activation by small molecules: kinetic and biophysical evidence for direct interaction of enzyme and activator. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32695–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Minor RK, Baur JA, Gomes AP, Ward TM, Csiszar A, Mercken EM, et al. SRT1720 improves survival and healthspan of obese mice. Sci Rep. 2011;1:70. doi: 10.1038/srep00070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Moonen HJ, Geraets L, Vaarhorst A, Bast A, Wouters EF, Hageman GJ. Theophylline prevents NAD+ depletion via PARP-1 inhibition in human pulmonary epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:1805–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Caton PW, Nayuni NK, Kieswich J, Khan NQ, Yaqoob MM, Corder R. Metformin suppresses hepatic gluconeogenesis through induction of SIRT1 and GCN5. J Endocrinol. 2010;205:97–106. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Bogachus LD, Turcotte LP. Genetic downregulation of AMPK-alpha isoforms uncovers the mechanism by which metformin decreases FA uptake and oxidation in skeletal muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C1549–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00279.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Zheng Z, Chen H, Li J, Li T, Zheng B, Zheng Y, et al. Sirtuin 1-mediated cellular metabolic memory of high glucose via the LKB1/AMPK/ROS pathway and therapeutic effects of metformin. Diabetes. 2012;61:217–28. doi: 10.2337/db11-0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Caton PW, Kieswich J, Yaqoob MM, Holness MJ, Sugden MC. Metformin opposes impaired AMPK and SIRT1 function and deleterious changes in core clock protein expression in white adipose tissue of genetically-obese db/db mice. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:1097–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Nelson LE, Valentine RJ, Cacicedo JM, Gauthier MS, Ido Y, Ruderman NB. A novel inverse relationship between metformin-triggered AMPK-SIRT1 signaling and p53 protein abundance in high glucose exposed HepG2 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00296.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Mostoslavsky R, Chua KF, Lombard DB, Pang WW, Fischer MR, Gellon L, et al. Genomic instability and aging-like phenotype in the absence of mammalian SIRT6. Cell. 2006;124:315–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Yang B, Zwaans BM, Eckersdorff M, Lombard DB. The sirtuin SIRT6 deacetylates H3 K56Ac in vivo to promote genomic stability. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2662–3. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Kawahara TL, Michishita E, Adler AS, Damian M, Berber E, Lin M, et al. SIRT6 links histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylation to NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression and organismal life span. Cell. 2009;136:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Michishita E, McCord RA, Berber E, Kioi M, Padilla-Nash H, Damian M, et al. SIRT6 is a histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylase that modulates telomeric chromatin. Nature. 2008;452:492–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Lombard DB, Schwer B, Alt FW, Mostoslavsky R. SIRT6 in DNA repair, metabolism and ageing. J Intern Med. 2008;263:128–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183.Mao Z, Hine C, Tian X, Van Meter M, Au M, Vaidya A, et al. SIRT6 promotes DNA repair under stress by activating PARP1. Science. 2011;332:1443–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1202723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184.Tang GJ, Wang HY, Wang JY, Lee CC, Tseng HW, Wu YL, et al. Novel role of AMP-activated protein kinase signaling in cigarette smoke induction of IL-8 in human lung epithelial cells and lung inflammation in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:1492–502. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 185.Wang Y, Liang Y, Vanhoutte PM. SIRT1 and AMPK in regulating mammalian senescence: a critical review and a working model. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:986–94. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186.Liang OD, Kleibrink BE, Schuette-Nuetgen K, Khatwa UU, Mfarrej B, Subramaniam M. Green tea epigallo-catechin-galleate ameliorates the development of obliterative airway disease. Exp Lung Res. 2011;37:435–44. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2011.584359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]