Abstract

Context:

Inflammation and excess abdominal adiposity (AA) are often present in normal-weight women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Objective:

We determined the effects of hyperglycemia on nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) activation in mononuclear cells (MNC) of normal-weight women with PCOS with and without excess AA.

Design:

This was a prospective controlled study.

Setting:

The study was conducted at an academic medical center.

Patients:

Fifteen normal-weight, reproductive-age women with PCOS (seven normal AA, eight excess AA) and 16 body composition-matched controls (eight normal AA, eight excess AA) participated in the study.

Main Outcome Measures:

Body composition was measured by dual-energy absorptiometry. Insulin sensitivity was derived from an oral glucose tolerance test (ISOGTT). Activated NFκB and the protein content of p65 and inhibitory-κB were quantified from MNC, and TNFα and C-reactive protein (CRP) were measured in plasma obtained from blood drawn while fasting and 2 h after glucose ingestion.

Results:

Compared with controls, both PCOS groups exhibited lower ISOGTT, increases in activated NFκB and p65 protein, and decreases in inhibitory-κB protein. Compared with women with PCOS with excess AA, those with normal AA exhibited higher testosterone levels and lower TNFα and CRP levels. For the combined groups, the percent change in NFκB activation was negatively correlated with ISOGTT and positively correlated with androgens. TNFα and CRP were positively correlated with abdominal fat.

Conclusion:

In normal-weight women with PCOS, the inflammatory response to glucose ingestion is independent of excess AA. Circulating MNC and excess AA are separate and unique sources of inflammation in this population.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a prooxidant, proinflammatory state as evidenced by elevated circulating levels of protein carbonyls and TNFα (1–4). Insulin resistance is also a common finding in PCOS and has been attributed to defective insulin signaling characterized by serine phosphorylation-induced suppression of insulin-stimulated insulin receptor substrate-1 activation (5, 6). Similar metabolic aberrations have been described in obesity-related diabetic syndromes and are considered to be causally related to adipose tissue hypoxia (7).

Expansion of adipose tissue in the obese leads to hypoxia-related cell death, prompting peripheral blood mononuclear cells (MNC) to migrate into the adipose stromal-vascular compartment (8, 9). MNC-derived macrophages engage in phagocytic activity that generates reactive oxygen species, which are a stimulus for oxidative stress (11). This phenomenon activates nuclear factor-κB (NFκB), a transcription factor heterodimer typically consisting of the DNA-binding subunits, p50 and p65 (12). NFκB is present in the cytoplasm complexed to its inhibitory protein known as inhibitory-κB (IκB). After activation, IκB dissociates from NFκB and undergoes ubiquitination and degradation. NFκB is freed to undergo nuclear translocation and subsequent DNA binding to promote transcription of TNFα (13). Positive feedback by TNFα produced in adipose tissue perpetuates the preceding molecular events. TNFα is also a known mediator of insulin resistance by stimulating serine phosphorylation to reduce insulin-stimulated insulin receptor substrate-1 activation (13, 14).

In our previous studies, we reported that circulating MNC are preactivated in the fasting state in normal-weight women with PCOS and that physiological hyperglycemia in these individuals activates NFκB and alters TNFα release from MNC (15–17). However, the increased prevalence of excess abdominal adiposity (AA) in almost one third of normal-weight women with PCOS was not considered in our previous investigations (18). Thus, the question remains whether inflamed excess AA in this population is the main stimulus for hyperglycemia-induced inflammation.

We designed a study to evaluate the effect of glucose ingestion on MNC-derived NFκB activation in normal-weight women with PCOS who had either normal or excess AA. We also evaluated this effect on the protein content of NFκB p65 and IκB. We hypothesized that in response to glucose ingestion, activated NFκB and p65 protein content are increased and IκB protein content is decreased in normal-weight women with PCOS, regardless of AA status compared with age- and body composition-matched controls and that there is an association between these markers of inflammation and AA, insulin sensitivity, and circulating androgens.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Fifteen normal-weight women with PCOS (seven normal AA and eight excess AA) 21–32 yr of age and 16 body composition-matched control subjects (eight normal AA and eight excess AA) 20–40 yr of age volunteered for study participation. Normal weight was defined as a body mass index (BMI) between 18 and 25 kg/m2. Excess AA was defined as the percent ratio of truncal fat to total body fat (% TF/TBF) measured by dual-energy absorptiometry (DEXA) that was greater than 42%, which was 2 sd above the mean of controls with normal AA. This definition was adopted from Carmina et al. (18), who studied a relatively lean Mediterranean population. However, the cutoff value is based on DEXA findings in an American normal-weight control population from our own report of greater truncal fat in normal-weight women with PCOS (17). The women with PCOS were diagnosed on the basis of oligoamenorrhea and hyperandrogenemia after excluding nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing's syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, and thyroid disease. Polycystic ovaries were present on ultrasound in all subjects with PCOS. All control subjects were ovulatory as evidenced by regular menses lasting 25–35 d and a luteal phase serum progesterone level greater than 5 ng/ml. All control subjects exhibited normal circulating androgen levels and the absence of androgen excess skin manifestations and polycystic ovaries on ultrasound.

Diabetes, inflammatory illnesses, and smoking were excluded in all subjects, and none were taking medications that would affect carbohydrate metabolism or immune function for at least 6 wk before study participation. None of the subjects were involved in any regular exercise program for at least 6 months before the time of testing. All subjects provided written informed consent in accordance with the institutional review board guidelines for the protection of human subjects.

Study design

All study subjects underwent an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between d 5 and 8 after the onset of menstruation and an overnight fast of approximately 12 h. The women were provided with a healthy diet consisting of 50% carbohydrate, 35% fat, and 15% protein for 3 consecutive days before the test. All subjects also underwent body composition assessment on the same day the OGTT was performed.

Oral glucose tolerance test

A 75-g glucose beverage was administered to all subjects. Blood samples were drawn while fasting and at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min after ingestion of the glucose beverage to measure glucose and insulin. Plasma glucose concentrations were assayed immediately, and insulin measurements were performed later from plasma stored at −80 C. Additional plasma was isolated from the fasting and 120-min (2 h) blood samples and stored at −80 C until assayed for C-reactive protein (CRP) and TNFα. Glucose tolerance was assessed by the World Health Organization criteria (19). Insulin sensitivity was derived from an OGTT (ISOGTT) using the following formula: 10,000 divided by the square root of (fasting glucose × fasting insulin) × (mean glucose × mean insulin) (20).

Body composition assessment

Height without shoes was measured to the nearest 1.0 cm. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg. Waist circumference was measured at the level of the umbilicus and used to estimate abdominal adiposity (21). In addition, all subjects underwent DEXA to determine truncal fat and total body fat using the QDR 4500 Elite model scanner (Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA) as previously described (17).

Molecular assays

MNC were isolated from blood samples obtained during the OGTT at 0 and 120 min (2 h). Nuclear-bound NFκB was quantified by EMSA as previously described (22). The protein content of p65, IκB, and actin was quantified by Western blotting as previously described using a 1:1000 dilution of a monoclonal antibody against p65 (Transduction Laboratories Inc., San Diego, CA), IκB (Transduction Laboratories), or actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) (23). Densitometry after the EMSA or Western blotting was performed on scanned films using Carestream Molecular Imaging software version 5.0.2.30 (Rochester, NY), and all values for p65 and IκB were corrected for loading using those obtained for actin.

Plasma and serum measurements

Plasma glucose, insulin, TNFα, and CRP along with serum testosterone, androstenedione, and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) were measured as previously described (5, 16). All samples from each subject were measured in duplicate in the same assay at the end of the study. The interassay and intraassay coefficients of variation for all assays were no greater than 7.4 and 12%, respectively.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using the StatView software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Sample size was calculated based on an expected difference of at least 30% between groups in activated NFκB with a sd of 22% and desired power of 80% using our previous study as a reference (16). Descriptive data and change from baseline in inflammation markers were compared using an ANOVA for multiple group comparisons followed by a post hoc analysis using Tukey's honestly significant difference test to identify the source of significance. Paired Student's t-tests were performed for within-group comparisons (pre- vs. post-glucose ingestion). Data are presented as mean ± se. Treatment effects on inflammation markers were determined by calculating percent change for each participant in view of interindividual variability. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to estimate the correlation between parameters. Results were considered significant at a two-tailed α-level of 0.05.

Results

Age, body composition, and serum hormone levels

All groups were similar in age, height, body weight, BMI, waist circumference, and total body fat (Table 1). Truncal fat was significantly (P < 0.03) greater in individuals with excess AA compared with those with normal AA, regardless of PCOS status. By design, there was significantly (P < 0.03) greater % TF/TBF in individuals with excess AA (controls: 44.0–50.6; PCOS: 44.7–57.4) compared with those with normal AA (controls: 36.3–41.7; PCOS: 31.9–41.6) whether or not they had PCOS. Serum levels of LH, testosterone, androstenedione, and DHEA-S were significantly (P < 0.03) higher in women with PCOS compared with control subjects, regardless of body composition status. Testosterone levels were significantly (P < 0.008) higher in normal-weight women with PCOS with normal AA compared with those with excess AA.

Table 1.

Age, body composition, endocrine and metabolic parameters of subjects

| Controls |

PCOS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal AA | Excess AA | Normal AA | Excess AA | |

| Age (yr) | 29 ± 2 | 29 ± 2 | 24 ± 2 | 29 ± 1 |

| Height (cm) | 165.1 ± 1.6 | 163.6 ± 2.1 | 165.6 ± 2.4 | 160.7 ± 3.8 |

| Body weight (kg) | 59.6 ± 3.1 | 59.8 ± 2.3 | 60.9 ± 2.5 | 62.8 ± 2.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.8 ± 0.9 | 22.3 ± 0.6 | 22.2 ± 0.9 | 24.3 ± 0.4 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 71.7 ± 3.5 | 78.3 ± 4.3 | 72.9 ± 2.0 | 80.6 ± 2.4 |

| Total body fat (kg) | 17.1 ± 1.5 | 20.3 ± 1.4 | 16.7 ± 1.5 | 20.5 ± 1.1 |

| Truncal fat (kg) | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 9.2 ± 0.6a,b | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 10.4 ± 0.7c,d |

| % TF/TBF | 38.9 ± 0.8 | 45.7 ± 0.8a,b | 38.0 ± 1.4 | 50.5 ± 1.8c,d,e |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 3.8 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 1.0b | 14.2 ± 1.7f | 13.0 ± 1.3d,e |

| Testosterone (ng/dl) | 48.8 ± 2.9 | 39.9 ± 4.7b | 87.7 ± 7.4f | 60.8 ± 5.7c,e |

| Androstendione (ng/ml) | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.8b | 3.7 ± 0.2f | 3.2 ± 0.4d,e |

| DHEA-S (μg/dl) | 165 ± 33 | 172 ± 27b | 322 ± 53f | 346 ± 38d,e |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 84 ± 1 | 89 ± 2 | 83 ± 4 | 88 ± 2 |

| 2-h glucose (mg/dl) | 111 ± 5.0 | 118 ± 4 | 97 ± 8 | 111 ± 6 |

| Fasting insulin (μIU/ml) | 6.5 ± 1.0 | 4.7 ± 0.8b | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 11.7 ± 1.7d,e |

| ISOGTT | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 9.0 ± 1.0b | 5.1 ± 0.4f | 4.5 ± 0.6d,e |

Values are expressed as means ± se. Conversion factors to SI units: testosterone × 3.467 (nanomoles per liter), androstenedione × 3.492 (nanomoles per liter), DHEA-S × 0.002714 (micromoles per liter), glucose × 0.0551 (millimoles per liter), and insulin × 7.175 (picomoles per liter).

Excess AA controls vs. normal AA controls (P < 0.03).

Excess AA controls vs. normal AA PCOS (P < 0.02).

Excess AA PCOS vs. normal AA PCOS (P < 0.002).

Excess AA PCOS vs. normal AA controls (P < 0.004).

Excess AA PCOS vs. excess AA controls (P < 0.02).

Normal AA PCOS vs. normal AA controls (P < 0.02).

Glycemic status and insulin sensitivity

Glucose levels while fasting and 2 h postglucose ingestion were similar in women with PCOS compared with controls, regardless of body composition status (Table 1). The glucose response during the OGTT was normal in all subjects with fasting glucose levels less than 100 mg/dl and 2 h glucose levels ranging between 78 and 135 mg/dl. Fasting insulin levels were significantly (P < 0.05) higher in both groups of women with PCOS compared with controls with excess AA and in women with PCOS with excess AA compared with controls with normal AA. ISOGTT was significantly (P < 0.05) lower in both groups of women with PCOS compared with control subjects, regardless of body composition status.

Markers of inflammation in MNC and plasma

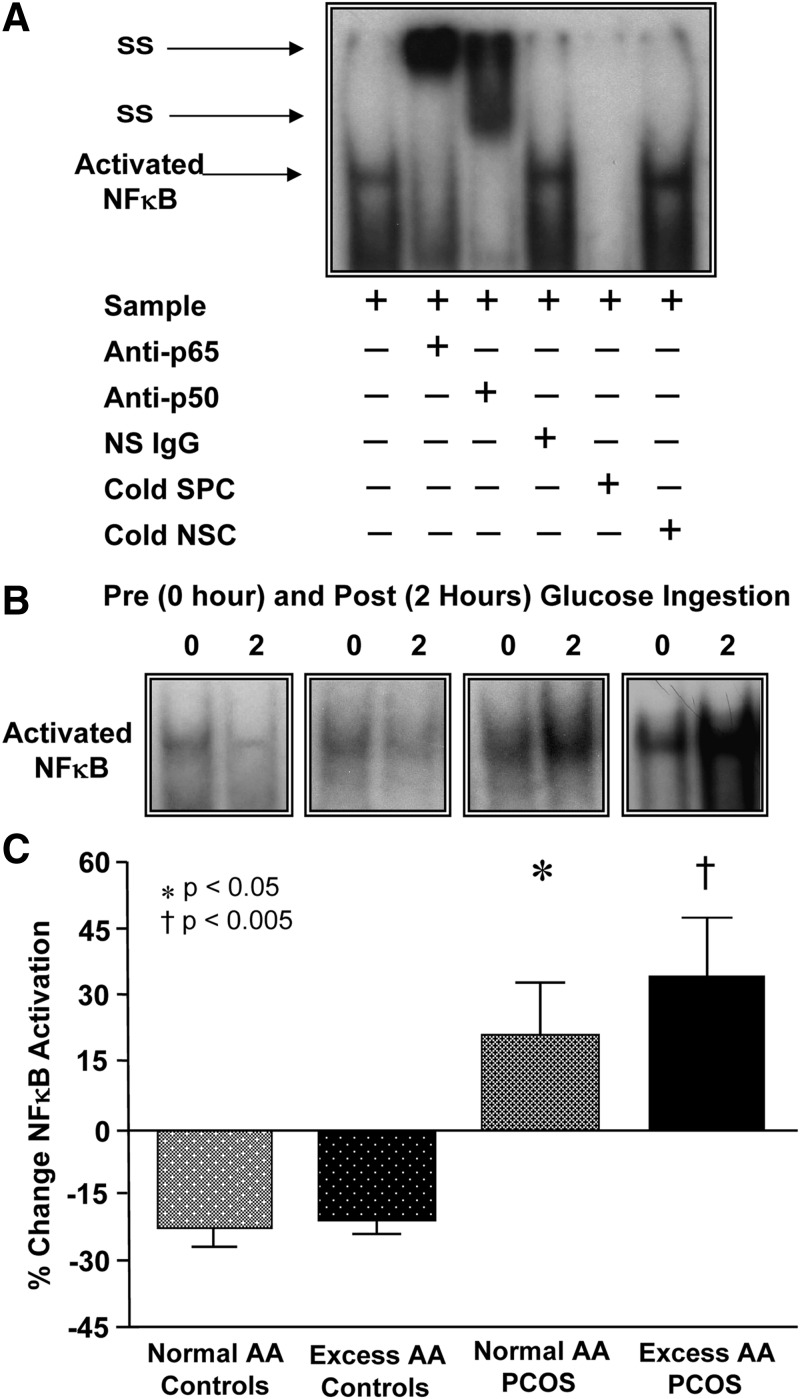

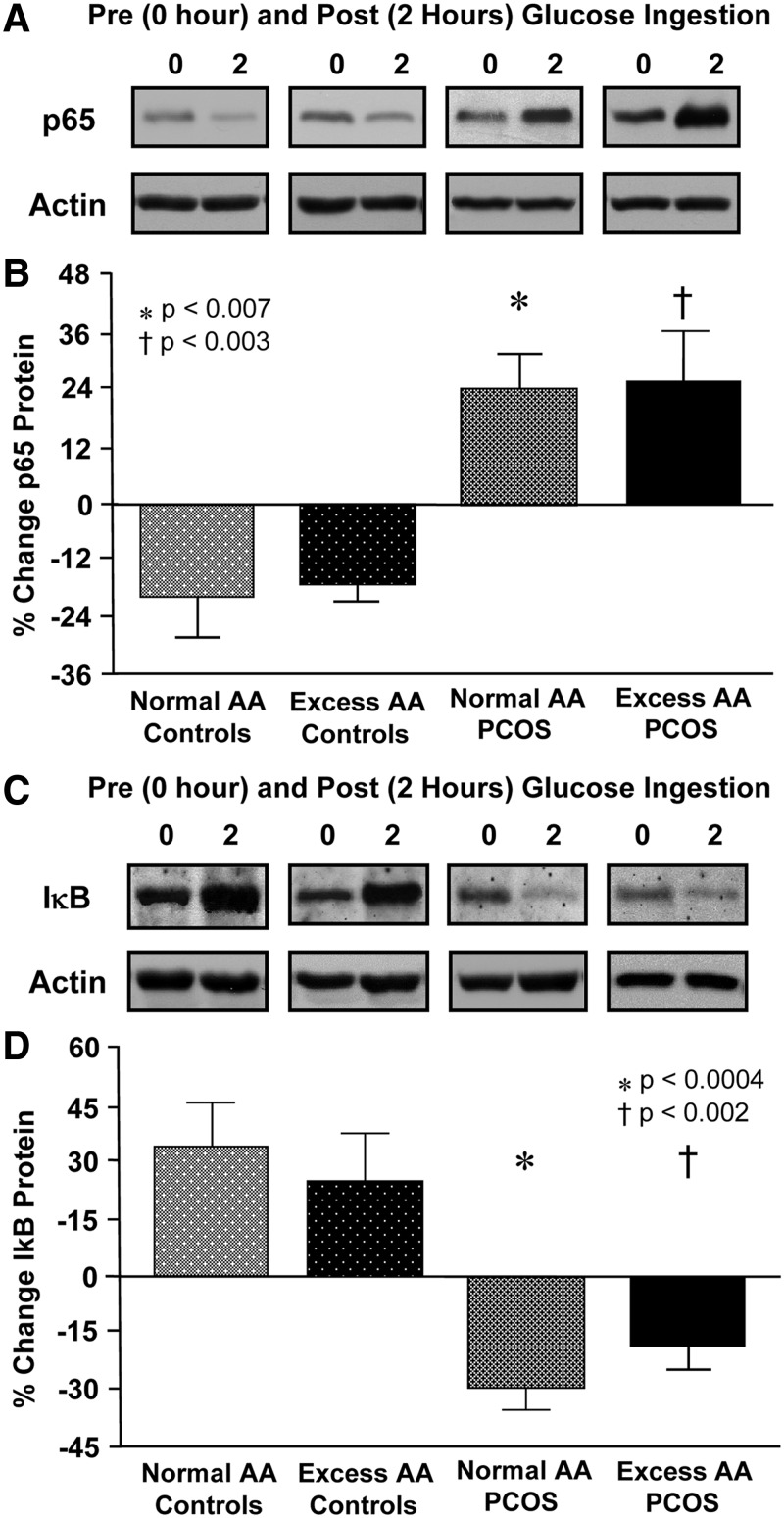

Supershift and cold competition experiments verified the specificity of the EMSA bands representing NFκB nuclear activation (Fig. 1A). In response to glucose ingestion, the percent change in activated NFκB and p65 protein content from MNC decreased in both control groups but increased in women with PCOS with both normal AA and excess AA and was significantly (P < 0.05) different compared with control subjects, regardless of body composition status (Fig. 1, B and C, and Fig. 2, A and B).

Fig. 1.

A, EMSA showing NFκB in nuclear extracts from MNC. A supershift of the NFκB band occurred during incubation with specific antibodies against NFκB subunits but not during incubation with nonspecific (NS) IgG. Neutralization of the NFκB band occurred during incubation with a specific cold competitor (SPC) of the oligonucleotide consensus sequence but not during incubation with a nonspecific cold competitor (NSC). B, Representative EMSA bands from the four study groups showing the quantity of NFκB in nuclear extracts from MNC in samples collected before and after the glucose ingestion. The samples used to quantify NFκB from both study groups were run on the same gel. C, Densitometric quantitative analysis comparing the change from baseline (percent) in MNC-derived activated NFκB between fasting and 2 h after the glucose ingestion samples. There was no significant difference in the response between the PCOS groups or the control groups. *, Response in women with PCOS with normal AA was significantly greater compared with that of either control group (P < 0.05); †, response in women with PCOS with excess AA was significantly greater compared with that of either control group (P < 0.005).

Fig. 2.

Representative Western blots from the four study groups showing the change in quantity of p65 and actin (A), and IκB (C) and actin in MNC homogenates in samples collected before and after glucose ingestion. The samples used to quantify proteins from both study groups were run on the same gel. Densitometric quantitative analysis comparing the change from baseline (percent) in MNC-derived p65 (B) and IκB protein content (D) between fasting and 2 h after glucose ingestion samples. There was no significant difference in the response between the PCOS groups or the control groups. *, In women with PCOS with normal AA, the p65 response was significantly greater and the IκB response was significantly reduced compared with that of either control group (p65: P < 0.007; IκB: P < 0.0004); †, In women with PCOS with excess AA, the p65 response was significantly greater and the IκB response was significantly reduced compared with that of either control group (p65: P < 0.003; IκB: P < 0.002).

The percent change in IκB increased in both control groups but decreased in women with PCOS with both normal AA and excess AA and was significantly (P < 0.002) different compared with control subjects, regardless of body composition status (Fig. 2, C and D). The percent change in NFκB activation and the protein content of p65 and IκB were similar in the PCOS groups and the control groups. However, there was a trend toward a greater percent change in NFκB activation and a lesser decline in the percent change in IκB protein content in the normal-weight women with PCOS with excess AA compared with those with excess AA.

Fasting plasma concentrations of TNFα and CRP were significantly (P < 0.05) higher in women with PCOS with excess AA compared with women with PCOS with normal AA or control subjects, regardless of body composition status (Fig. 3, A and B). Fasting plasma CRP concentrations were also significantly (P < 0.05) higher in controls with excess AA compared with those with normal AA. Plasma TNFα and CRP concentrations after glucose ingestion remained unaltered compared with baseline fasting values in all four groups (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Plasma levels of TNFα (A) and CRP (B) measured in fasting blood samples. Plasma TNFα and CRP levels were significantly higher in women with PCOS with excess AA compared with controls with normal AA (*, TNFα: P < 0.005; CRP: P < 0.0002), controls with excess AA (†, TNFα: P < 0.05; CRP: P < 0.02) and women with PCOS with normal AA (‡, TNFα: P < 0.002; CRP: P < 0.0006). Plasma CRP levels were significantly higher in controls with excess AA compared with controls with normal AA (triple dagger, P < 0.05).

Correlations

Waist circumference was positively correlated with the % TF/TBF (r = 0.69, P < 0.004) and the percent change in activated NFκB (r = 0.38, P < 0.02) and fasting TNFα levels (r = 0.67, P < 0.02). The % TF/TBF was positively correlated with fasting levels of TNFα and CRP (Table 2). ISOGTT was negatively correlated with the percent change in activated NFκB and p65 protein content and positively correlated with the percent change in IκB protein content. There were no correlations between any of the body composition markers including % TF/TBF and ISOGTT (data not shown).

Table 2.

Spearman rank correlations between inflammation markers and abdominal fat, insulin sensitivity, LH, androgens, and each other for the combined groups

| Activated NFκB (% change) | p65 (% change) | IκB (% change) | TNFα (pg/ml) | CRP (mg/liter) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % TF/TBF | |||||

| r | 0.250 | −0.011 | −0.071 | 0.536 | 0.587 |

| P | 0.170 | 0.958 | 0.696 | 0.009a | 0.002a |

| ISOGTT | |||||

| r | −0.500 | −0.543 | 0.507 | −0.193 | −0.252 |

| P | 0.006a | 0.008a | 0.006a | 0.344 | 0.175 |

| LH (IU/ml) | |||||

| r | 0.617 | 0.518 | −0.606 | −0.350 | 0.227 |

| P | 0.006a | 0.048a | 0.007a | 0.175 | 0.322 |

| Testosterone (ng/dl) | |||||

| r | 0.516 | 0.509 | −0.600 | −0.348 | 0.149 |

| P | 0.005a | 0.013a | 0.001a | 0.184 | 0.427 |

| Androstenedione (ng/ml) | |||||

| r | 0.586 | 0.634 | −0.685 | −0.305 | 0.145 |

| P | 0.002a | 0.002a | 0.0002a | 0.143 | 0.444 |

| DHEA-S (μg/dl) | |||||

| r | 0.500 | 0.635 | −0.431 | 0.070 | 0.325 |

| P | 0.006a | 0.002a | 0.018a | 0.732 | 0.080 |

P < 0.05.

The percent change in activated NFκB was positively correlated with the percent change in the protein content of p65 (r = 0.48, P < 0.02) and IκB (r = 0.44, P < 0.02) and with fasting CRP levels (r = 0.38, P < 0.05). Serum levels of LH, testosterone, androstenedione, and DHEA-S were positively correlated with the percent change in activated NFκB and p65 protein content and negatively correlated with the percent change in IκB protein content (Table 2).

In women with PCOS, % TF/TBF was negatively correlated with testosterone (r = −0.68, P < 0.02) and positively correlated with fasting levels of CRP (r = 0.63, P < 0.02) and TNFα (r = 0.86, P < 0.005). Waist circumference was also positively correlated with fasting TNFα levels (r = 0.67, P < 0.04). There were no correlations between any other measures when women with PCOS or control subjects were evaluated separately (data not shown).

Discussion

Our data clearly show for the first time that in PCOS, the inflammatory response to physiological hyperglycemia emitted from circulating MNC occurs even when excess AA is lacking. Increases in activated NFκB, the cardinal signal of inflammation, and p65 protein content as well as decreases in IκB protein content during glucose challenge is evident in normal-weight women with PCOS with normal AA compared with normal weight controls with normal AA. Activated NFκB and p65 protein content are negatively associated with insulin sensitivity and positively associated with LH and androgen levels, lending support to the concept that glucose-stimulated inflammation from MNC may be involved in promoting insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in PCOS. Furthermore, the positive association between circulating and molecular markers of inflammation and measures of abdominal fat suggests that in PCOS, excess AA is a contributor to the inflammatory load.

Suppression of MNC-derived inflammation may be the normal in vivo response to glucose ingestion in normal-weight young women independent of AA status. NFκB activation and p65 protein content are suppressed and IκB protein content is increased in controls with both normal and excess AA. These data corroborate our previous findings in normal reproductive-age women, that MNC are at rest in the fasting state and markers of oxidative stress and inflammation including TNFα release from MNC are suppressed during physiological hyperglycemia (1, 16, 24). This is key because MNC-derived macrophages that infiltrate excess adipose tissue and muscle exert a paracrine effect on insulin action (8, 25). Moreover, TNFα release from MNC-derived macrophages following NFκB activation may inhibit insulin signaling to impair glucose uptake (26). In corroboration, ablation of MNC-derived macrophages in muscle of insulin resistant animals improves insulin sensitivity (27). Thus, postprandial suppression of NFκB activation to limit TNFα release may be a safeguard to maximize insulin signaling for glucose disposal in normal weight reproductive-age women.

In contrast, MNC of normal-weight women with PCOS are in a proinflammatory state as evidence by increased sensitivity to physiological hyperglycemia regardless of AA status. NFκB activation and p65 protein content increase and IκB protein content decreases after glucose ingestion in normal-weight women with PCOS with both normal AA and excess AA compared with either control group. These findings are in keeping with our previous reports of MNC preactivation in the fasting state and glucose-stimulated NFκB activation from MNC in women with PCOS (15, 16). Most notably, they highlight the discrete role of circulating MNC in the development of chronic low-grade inflammation in the disorder that may be the underpinning of altered TNFα release in response to glucose ingestion in normal-weight women with PCOS (17). A similar inflammatory response can occur after lipid and protein ingestion (28). Thus, dietary intake alone in the absence of excess adiposity may stimulate an acute inflammatory response in PCOS capable of mediating insulin resistance. A decrease in inflammation after a 2-d fast in normal subjects along with the negative association of NFκB activation and p65 protein content and the positive association of IκB protein content with insulin sensitivity in the current study lends support for this idea (29).

In PCOS, glucose-stimulated inflammation may directly promote hyperandrogenism. Circulating LH, testosterone, androstenedione, and DHEA-S are all positively associated with glucose-stimulated NFκB activation and p65 protein content and negatively associated with IκB protein content. This corroborates similar results from our past reports (15, 16, 24). Although the relationship with LH raises the possibility that inflammation has a central effect on androgen production, impact at the local level is well characterized. The ovary contains MNC-derived macrophages (30). The gene expression of the androgen-producing steroidogenic enzyme, CYP17, increases in cultured theca cells in the presence of prooxidants and decreases in the presence of antioxidants such as resveratrol and statins (31, 32). Theca cells from rat and human polycystic ovaries undergo proliferation in vitro, and this effect is inhibited by statins (33, 34). In addition, chronic androgen suppression does not alter CRP in normal-weight women with PCOS (35). Thus, ovarian androgen production in women with PCOS may be the culmination of a local inflammatory response manifested by hyperglycemia-induced NFκB activation in migrant MNC within the polycystic ovary.

Apart from diet-induced inflammation arising from circulating MNC, excess AA can be an additional source of inflammation in normal-weight women with PCOS. There is a trend toward greater NFκB activation and fasting TNFα and CRP levels are significantly higher in normal-weight women with PCOS with excess AA compared with those with normal AA. The modest sample size may account for the inability to detect a significant difference in NFκB activation between these two groups. In addition, measures of abdominal fat are positively associated with hyperglycemia-induced NFκB activation and fasting TNFα and CRP levels. It is now clear that the migration of MNC into excess adipose tissue in response to hypoxia-related cell death incites oxidative stress (8, 9). The subsequent production of TNFα in adipose tissue primarily originates from MNC-derived macrophages but also serves as a paracrine stimulator of adipocyte TNFα production (36). This notwithstanding, the observed TNFα and CRP elevations are rather modest compared with what is seen in obesity (1, 4, 16, 17). Fasting TNFα and CRP elevations in normal-weight women with PCOS with excess AA most likely reflect the chronic presence of adiposity. For TNFα in particular, the lack of an acute change in circulating levels after glucose ingestion is consistent with less of an endocrine-like effect in contrast to its typical paracrine action in tissue. Furthermore, the similar fasting TNFα and CRP levels in women with PCOS with normal AA and normal-weight controls with normal AA suggests that these circulating inflammation markers are normal in PCOS in the absence of excess AA. Further investigation in a larger cohort is merited for confirmation. Thus, the mild TNFα and CRP elevations evident in normal-weight women with PCOS are a manifestation of the inflammatory load contributed by excess AA.

In PCOS, the impact of adiposity in the development of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism depends on the amount of fat accumulated in a given individual. In fact, molecular inflammation marker expression in adipose tissue is in proportion to the degree of adiposity in PCOS but is not uniquely greater when compared with individuals without PCOS (37). Excess AA is a promoter of insulin resistance in obesity and is negatively associated with measures of insulin sensitivity in studies that include obese individuals whether or not they have PCOS (1, 15–17, 22, 24). However, AA is not related to insulin sensitivity in our normal-weight study cohort. This suggests that in PCOS, the amount of inflamed excess adipose tissue present in the abdomen in the absence of increased body weight may not contribute substantially to the observed insulin resistance. Excess AA also directly correlates with circulating androgens in studies that include obese women with PCOS (38). This is consistent with the common concept that in PCOS insulin resistance promotes hyperandrogenism (39). In contrast, circulating testosterone is negatively associated with AA in our normal-weight PCOS study population and is elevated to a greater extent in normal-weight women with PCOS with normal AA compared with those with excess AA. As a known suppressor of lipolysis, testosterone at these higher levels may limit the development of AA in normal-weight women with PCOS (40). Thus, inflamed excess AA may not play a significant role in the promotion of insulin resistance in normal-weight women with PCOS, and the evolution of excess AA in PCOS before weight gain may be dictated by the initial extent of hyperandrogenism.

In conclusion, normal-weight women with PCOS exhibit increased NFκB activation and p65 protein content and decreased IκB protein content in response to glucose ingestion that is independent of excess AA. This proinflammatory phenomenon showcases the role of circulating MNC in the development of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in PCOS. The relationship between abdominal adiposity and markers of inflammation illustrates the relative contribution of excess AA to inflammation in normal-weight women with PCOS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant HD-048535 from the National Institutes of Health (to F.G.).

This paper was presented at the 94th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, San Antonio, Texas, June 23–26, 2012.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AA

- Abdominal adiposity

- BMI

- body mass index

- CRP

- C-reactive protein

- DEXA

- dual-energy absorptiometry

- DHEA-S

- dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate

- IκB

- inhibitory-κB

- ISOGTT

- insulin sensitivity was derived from an OGTT

- MNC

- mononuclear cell

- NFκB

- nuclear factor-κB

- OGTT

- oral glucose tolerance test

- PCOS

- polycystic ovary

- % TF/TBF

- percent ratio of truncal fat to total body fat.

References

- 1. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. 2006. Reactive oxygen species-induced oxidative stress in the development of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:336–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelly CC, Lyall H, Petrie JR, Gould GW, Connell JM, Sattar N. 2001. Low grade chronic inflammation in women in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:2453–2455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fenkci V, Fenkci S, Yilmazer M, Serteser M. 2003. Decreased total antioxidant status and increased oxidative stress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome may contribute to the risk of cardiovascular disease. Fertil Steril 80:123–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gonzalez F, Thusu K, Abdel-Rahman E, Prabhala A, Tomani M, Dandona P. 1999. Elevated serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α in normal-weight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Metabolism 48:437–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dunaif A, Segal KR, Futterweit W, Dobrjansky A. 1989. Profound peripheral insulin resistance, independent of obesity, in polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes 38:1165–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corbould A, Kim YB, Youngren JF, Pender C, Kahn BB, Lee A, Dunaif A. 2005. Insulin resistance in the skeletal muscle of women with PCOS involves intrinsic and acquired defects in insulin signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288:E1047–E1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yin J, Gao Z, He Q, Zhou D, Guo Z, Ye J. 2009. Role of hypoxia in obesity-induced disorders of glucose and lipid metabolism in adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296:E333–E342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr 2003. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112:1796–1808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, Wang S, Fortier M, Greenberg AS, Obin MS. 2005. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res 46:2347–2355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Groemping Y, Rittinger K. 2005. Activation and assembly of the NADPH oxidase: a structural perspective. Biochem J 386:401–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chanock SJ, el Benna J, Smith RM, Babior BM. 1994. The respiratory burst oxidase. J Biol Chem 269:24519–24522 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baldwin AS., Jr 2001. The transcription factor NFκB and human disease. J Clin Invest 107:3–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barnes PJ, Karin M. 1997. Nuclear factor-κB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med 336:1066–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rui L, Aguirre V, Kim JK, Shulman GI, Lee A, Corbould A, Dunaif A, White MF. 2001. Insulin/IGF-1 and TNF-α stimulate phosphorylation of IRS-1 at inhibitory Ser307 via distinct pathways. J Clin Invest 107:181–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. 2007. Insulin sensitivity and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome are related to activated nuclear factor κB from mononuclear cells in the fasting state. Program of the 89th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, p 142 (Abstract OR50-3) [Google Scholar]

- 16. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. 2006. Increased activation of nuclear factor κB triggers inflammation and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:1508–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. González F, Minium J, Rote NS, Kirwan JP. 2005. Hyperglycemia alters tumor necrosis factor-α release from mononuclear cells in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:5336–5342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carmina E, Bucchieri S, Esposito A, Del Puente A, Mansueto P, Orio F, Di Fede G, Rini G. 2007. Abdominal fat quantity and distribution in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and extent of its relation to insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2500–2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Modan M, Harris MI, Halkin H. 1989. Evaluation of WHO and NDDG criteria for impaired glucose tolerance. Results from two national samples. Diabetes 38:1630–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. 1999. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing. Diabetes Care 22:1462–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kohrt WM, Kirwan JP, Staten MA, Bourey FE, King DS, Holloszy JO. 1993. Insulin resistance of aging is related to abdominal obesity. Diabetes 42:273–281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, O'Leary VB, Kirwan JP. 2007. Obese reproductive age women exhibit a proatherogenic inflammatory response during hyperglycemia. Obesity 15:2436–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aljada A, Ghanim H, Dandona P. 2002. Translocation of p47phox and activation of NADPH oxidase in mononuclear cells. Methods Mol Biol 196:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. González F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. 2006. In vitro evidence that hyperglycemia stimulates tumor necrosis factor-α release in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol 188:521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Varma V, Yao-Borengasser A, Rasouli N, Nolen GT, Phanavanh B, Starks T, Gurley C, Simpson P, McGehee RE, Jr, Kern PA, Peterson CA. 2009. Muscle inflammatory response and insulin resistance: synergistic interaction between macrophages and fatty acids leads to impaired insulin action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296:E1300–E1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hotamisligil GS, Murray DL, Choy LN, Spiegelman BM. 1994. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibits signaling from the insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:4854–4858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patsouris D, Li PP, Thapar D, Chapman J, Olefsky JM, Neels JG. 2008. Ablation of CD11c-positive cells normalize insulin sensitivity in obese insulin resistant animals. Cell Metab 8:301–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohanty P, Ghanim H, Hamouda W, Aljada A, Garg R, Dandona P. 2002. Both lipid and protein intakes stimulate increased generation of reactive oxygen species by polymorphonuclear leukocytes and mononuclear cells. Am J Clin Nutr 75:767–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dandona P, Mohanty P, Hamouda W, Ghanim H, Aljada A, Garg R, Kumar V. 2001. Inhibitory effect of a two day fast on reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by leucocytes and plasma ortho-tyrosine and meta-tyrosine concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 862:899–2902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Best CL, Pudney J, Welch WR, Burger N, Hill JA. 1996. Localization and characterization of white blood cell populations within the human ovary throughout the menstrual cycle and menopause. Hum Reprod 11:790–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Piotrowski PC, Rzepczynska IJ, Kwintkiewicz J, Duleba AJ. 2005. Oxidative stress induces expression of CYP11A, CYP17, STAR and 3βHSD in rat theca-interstitial cells. J Soc Gynecol Invest 12 (Suppl 2):319A (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wong DH, Villanueva JA, Cress AB, Sokalska A, Ortega I, Duleba AJ. 2011. Resveratrol inhibits the mevalonate pathway and potentiates the antiproliferative effects of simvastatin in rat theca-interstitial cells. Fertil Steril 96:1252–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spaczynski RZ, Arici A, Duleba AJ. 1999. Tumor necrosis factor α stimulates proliferation of rat ovarian theca-interstitial cells. Biol Reprod 61:993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sokalska A, Piotrowski PC, Rzepczynska IJ, Cress A, Duleba AJ. 2010. Statins inhibit growth of human theca-interstitial cells in PCOS and non-PCOS tissues independently of cholesterol availability. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5390–5394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. González F, Sia CL, Stanczyk FZ, Blair HE, Krupa ME. 1 July 2012. Hyperandrogenism exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrine 10.1007/s12020-012-9728-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fain JN, Bahouth SW, Madan AK. 2004. TNFα release by nonfat cells of adipose tissue. Int J Obes 28:616–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lindholm A, Blomquist C, Bixo M, Dahlbom I, Hansson T, Sundström Poromaa I, Burén J. 2011. No difference in markers of adipose tissue inflammation between overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome and weight-matched controls. Hum Reprod 26:1478–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tosi F, Negri C, Perrone F, Dorizzi R, Castello R, Bonora E, Moghetti P. 2012. Hyperinsulinemia amplifies GnRH agonist stimulated ovarian steroid secretion in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:1712–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Holte J, Bergh T, Gennarelli G, Wide L. 1994. The independent effects of polycystic ovary syndrome and obesity on serum concentrations of gonadotrophins and sex steroids in premenopausal women. Clin Endocrinol 41:473–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xu X, De Pergola G, Björntorp P. 1990. The effects of androgens on the regulation of lipolysis in adipose precursor cells. Endocrinology 126:1229–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]