Abstract

Experimental oral challenge studies with three different genotypes of Escherichia coli O157:H7 were conducted in cattle to determine the genotype-specific variability in shedding frequencies and concentrations and the frequency and extent of contamination of the environment. The results indicated that the E. coli O157:H7 genotype and ecological origin maybe important factors for the occurrence and concentration in the cattle host. Four groups of six young Holstein steers each were orally challenged with 106 CFU of one of three E. coli O157:H7 strains: FRIK 47 (groups 1 and 2), FRIK 1641 (group 3), and FRIK 2533 (group 4). Recto-anal mucosal swabs (RAMS) and environmental samples were taken on alternate days over 30 days. The numbers of E. coli O157:H7 cells and generic E. coli cells per sample were determined. Also, the presence and absence of 28 gene targets were determined for 2,411 isolates using high-throughput real-time PCR. Over the study period, strains FRIK 47, FRIK 1641, and FRIK 2533 were detected in 52%, 42%, and 2% of RAMS, respectively. Environmental detection of the challenge strains was found mainly in samples of the hides and pen floors, with strains FRIK 47, FRIK 1641, and FRIK 2533 detected in 22%, 27%, and 0% of environmental samples, respectively. Based on the panel of 28 gene targets, genotypes of enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) and generic E. coli from the experimental samples were clustered into three subgroups. In conclusion, the results suggested that the type and intensity of measures to control this pathogen at the preharvest level may need to be strain specific.

INTRODUCTION

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) is a class of zoonotic pathogens that can cause human infections and symptoms ranging from asymptomatic carriage to nonbloody diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), and death (9, 37, 50). The majority of the cases of infection are caused by serotype O157:H7, which was initially recognized as a human pathogen in 1982 in the United States (45). Cattle are a major reservoir for human infection (5, 52), and outbreaks of disease are commonly linked either directly or indirectly with multiple vehicles (9). Sources of infection include direct contact with animals, meat (1), raw milk (51), cheese, unpasteurized apple cider and juice (4), produce, and contaminated water sources (9, 24, 37, 52).

The association of E. coli O157:H7 with cattle and bovine products has led researchers to explore ways to circumvent this zoonosis through targeted slaughter practices and carcass decontamination (3, 10, 11, 29). Many factors influence the transmission, prevalence, and levels of shedding of EHEC in cattle, such as age (14, 21, 39), stress (13), season (25), diet (16), presence of high-level shedders in the herd (41), intermittent and continuous fecal shedding patterns (46–48), housing environment (47), and herd management practices (26). The evaluation of preharvest control measures to reduce this pathogen has been shown to be potentially effective at decreasing the risk of human infections (28). However, to design more effective control measures, a greater understanding of the strain-specific E. coli O157:H7 excretion patterns during colonization in cattle, as well as the dynamics of contamination of their immediate environment and the subsequent dynamics of transmission and general E. coli population characteristics, is needed.

Previous research has focused on serotype O157:H7 and has provided valuable information, but there is an incomplete understanding of the population dynamics and ecology of individual strains of E. coli O157:H7 in cattle and on farms. The focus of this study was to monitor three E. coli O157:H7 strains with different genotypes and ecological origins using a bovine inoculation challenge model that mimics a level of environmental E. coli O157:H7 exposure (14, 33, 41, 48, 53) with the objective of determining the genotype-specific day-to-day variability in animals' shedding frequencies and concentrations and the frequency and the extent of contamination of the animals' immediate environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

Four concurrent Escherichia coli O157:H7 oral challenge experiments were conducted using 24 Holstein steers purchased from a commercial livestock dealer in Wisconsin. Steers were 4 to 5 months of age and between 127 and 191 kg. Upon arrival at the Livestock Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin—Madison, steers were vaccinated according to label directions with Bovi-Shield Gold (Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) and Vision 7 (Intervet, Inc., Summit, NJ) and received a dose of ceftiofur (3.0 mg ceftiofur equivalents [CE]/lb Excede; Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY) to prevent shipping fever. Steers were randomly ear tagged (numbers 1 through 24) and had initial body temperatures and weights recorded. The steers were divided into four groups of six and housed in four different pens, in two rooms designated A and B. Steers 1 through 12 were housed in room A, with steers 1 through 6 (group 1) in pen 1 and steers 7 through 12 (group 2) in pen 2. Steers 13 through 24 were housed in room B, with steers 13 through 18 (group 3) housed in pen 3 and steers 19 through 24 (group 4) housed in pen 4. Both rooms were temperature controlled at 20°C, with a positive-pressure ventilation system, equipped with headlocks, slatted floors, and waste flushing systems. Access to the rooms was restricted to animal caretakers and investigators. Each pen was cleaned twice daily using water flushed over the pen floors. In each room, pens were separated by a corridor which prevented contact between groups. A cleaning protocol of the corridors between pens was followed once per day using hot water and disinfectants. In addition, footbaths, changing gloves, single-use coveralls, face masks, and head covers were used to prevent carryover of strains between the groups of cattle.

Steers were offered a ration composed of alfalfa pellets, shelled corn, chopped hay, and a standard concentrate supplement and delivered once a day, according to the National Research Council (NRC) specifications for an average daily gain of 0.7 kg/day (38). Each group was offered feed in bins and provided ad libitum water using water flow cups, both accessible through headlocks. Prior to the experimental infection, the health status was recorded daily by monitoring body temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate. Body weight was measured weekly. After experimental infection, body temperature was recorded three times per week. All procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin—Madison, School of Veterinary Medicine, IACUC (protocol A01388-0-03-09).

Study timeline and challenge model.

At the start of study in June 2010, steers were monitored during a prechallenge period of 20 days for the absence of wild-type E. coli O157. Recto-anal mucosal swabs (RAMS) and environmental samples were obtained on alternate days and enumerated for the isolation of E. coli O157:H7 and generic E. coli (12, 44). Following this period, four concurrent single-strain oral challenge experiments were initiated using three E. coli O157:H7 strains. Within each group, all steers were inoculated orally with 106 CFU of one of the three selected strains. Water access was restricted for 12 h prior to inoculation to ensure that cattle drank the inoculum. Each steer was individually offered 1 ml of the inoculum diluted in approximately 10 ml of clean tap water in a clean and empty water cup. Investigators observed each steer while the entire inoculum was consumed and then offered additional clean water in the same water cup to ensure consumption of any remaining inoculum.

E. coli O157:H7 challenge strains.

Three strains of E. coli O157:H7 were selected for the experimental inoculation challenges based on their differences in genotypes, origins, and their potential for colonization (45, 47). These strains had distinct genotypes as determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (47, 48) and a genetic marker profile analysis using real-time PCR (22). Strain FRIK 47 was of human origin and had observed pathogenicity in human (45). FRIK 47 was obtained from the Food Research Institute-Kaspar (FRIK) culture collection and is identical to strain 933W (ATCC 43895) (42). In disease cases in humans, FRIK 47 had been shown to be able to colonize the gastrointestinal tract (GI) and was assumed to be capable of colonization of the bovine GI tract as well (27). Strain FRIK 1641 was previously isolated from a raccoon (47) and selected as a representative environmental (nonbovine-adapted) strain. Since it had no links to any human disease cases and had not been isolated from cattle, FRIK 1641 was expected to be less efficient in terms of colonization in cattle than FRIK 47. Strain FRIK 2533 was previously isolated from a Wisconsin dairy farm (C. W. Kaspar, unpublished data). It was chosen for its lack of the pO157 plasmid which encodes the hemolysin gene, considered to be a key virulence factor (9). Therefore, FRIK 2533 was expected to be less efficient than both FRIK 47 and FRIK 1641 at colonizing the bovine GI tract. A genetic profile was created for each strain based on a panel of 28 genetic markers that highlighted select virulence markers, O-antigens, and prophage regions as reported by Gonzales et al. (22). These genetic profiles were used for PCR confirmation of the presence of the inoculation strains from the samples. All steers in groups 1 and 2 were inoculated with FRIK 47, group 3 was inoculated with FRIK 1641, and group 4 was inoculated with FRIK 2533.

To maintain consistency of the inoculum for each strain, three test runs for each strain with preset overnight incubation periods of −80°C freezer stock cultures in LB broth (LB Broth, Miller; BD, Sparks, MD), followed by a 3-h incubation of 1 ml of the overnight culture in 9 ml of LB culture broth, were conducted to produce the inoculum for each strain of E. coli O157:H7. Each time, the CFU counts were confirmed by plate counts and spectrophotometry.

Sampling.

Recto-anal mucoscal swabs and environmental samples were obtained on alternate days during the 20-day prechallenge period and the 30-day challenge experiments. RAMS were obtained aseptically using sterile cotton-tipped applicators (6 in. in length). The applicator was inserted one to two inches into the rectum and rubbed three to four times along the mucosal surface using a rapid motion (44). RAMS were placed into a sterile tube containing 5 ml of modified E. coli broth (mEC; Remel, Lenexa, KS) and novobiocin (0.02 mg/ml; mECnov; Remel, Lenexa, KS). The samples were stored in the mECnov broth at room temperature for an average of 1 h prior to processing.

Environmental samples were collected from hides, feed troughs, drinking water, water cup runoff, and housing pens. Sterile cellulose sponges (2 by 3.5 by 1 in.) were used to obtain hide samples and feed trough samples. Sponges were moistened with mECnov broth prior to sampling. Each feed trough sample was a composite sample of the feed bins obtained by wiping a moistened sponge in and around the bins prior to feeding when bins were empty. After sampling, the sponge was placed in a sterile Whirl-Pak (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI) that contained 10 ml of mECnov broth and homogenized by hand. Each hide sample was a composite of six steers, obtained by wiping each steer with the same sponge along their lower abdomens and flanks twice. After sampling, the hide sponge sample was placed in a sterile Whirl-Pak that contained 10 ml of mECnov broth and homogenized by hand.

Samples from housing pens and water cup runoff were obtained using a rope (49). Sterile nylon ropes approximately 3 feet long with 8-mm thickness (∼52 g; Koch Industries, Minneapolis, MN) were attached to a gate along the back wall (herein referred to as gate ropes) and to a pole near the drinking water cups (herein referred to as water ropes). Each rope was positioned in such a way that it touched the floor of the pen and was accessible to the steers. Rope samples were collected 24 h after placement and stored at room temperature until processing, approximately 1 h after collection. Water samples were obtained by direct sampling of 10 ml of water from water cups using sterile collection tubes (15 ml Falcon centrifuge tubes; BD, Sparks, MD) and stored at room temperature prior to processing.

Isolation and selection of challenge strains.

All sample processing procedures were conducted in the same manner for both the 20-day prechallenge period and the 30-day challenge experiments. Each RAMS sample combined with 5 ml of mECnov broth (RAMS broth sample) was vortexed for 5 s prior to plating. For the enumeration of E. coli O157, RAMS broth samples were directly plated on sorbitol-MacConkey agar supplemented with 0.05 mg/liter cefixime and 2.5 mg/liter potassium tellurite (CT-SMAC; BD, Sparks, MD). From the original RAMS broth sample, two 500-μl volumes were spread on two separate 40-ml CT-SMAC agar plates (15x150 mm). Also, 100- and 50-μl volumes of the original RAMS broth sample were spread on two separate 15-ml CT-SMAC agar plates (15 by 100 mm). Samples were then enumerated for generic E. coli by using a dilution series of the original RAMS broth sample in 0.1% peptone water and plating on eosin methylene blue (EMB) agar (Levine EMB agar; BD, Sparks, MD). From the 10−2 dilution, 100 μl was spread on a 15-ml EMB agar plate (15 by 100 mm). After the last step, 100- and 50-μl volumes of the 10−3 dilution were spread on two separate 15-ml EMB agar plates. All plates were incubated at 37°C for approximately 20 to 24 h. After overnight incubation, colonies on CT-SMAC agar with a morphology that was round and flesh-toned in appearance (sorbitol-negative) were suspected to be E. coli O157 and were counted. On the EMB agar, colonies that were dark purple and dark purple with a metallic green sheen were suspected to be E. coli and were counted. From the colony counts CFU concentrations were calculated to determine the number or CFU per ml in RAMS broth samples. The minimum detection limit of E. coli O157:H7 for the direct plating procedure was approximately 2 CFU/ml or 10 CFU/swab.

For each sponge sample, the mECnov broth was squeezed from the sponge and placed into a sterile specimen tube (15 ml Falcon centrifuge tubes; BD, Sparks, MD). To each gram of rope, 1 ml of mECnov broth was added. The samples were hand mixed for 15 to 20 s, and the mECnov broth sample was transferred to a sterile specimen tube. Drinking water samples were vortexed for 5 s prior to processing. For the enumeration of E. coli O157:H7, samples were spread on CT-SMAC agar following the same plating scheme as stated above for RAMS. Samples were then enumerated for generic E. coli by direct plating of 100 μl and 50 μl of the original sample onto two separate 15-ml EMB agar plates. All plates were incubated at 37°C for approximately 20 to 24 h. After overnight incubation, colony counts and CFU calculations were performed as stated above.

Colonies on CT-SMAC agar suspected to be E. coli O157 were presumptively identified using RIM E. coli O157:H7 latex test kit (Remel, Lenexa, KS). For each sample, up to five randomly selected suspect colonies confirmed by latex agglutination were subcultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (LB Broth, Miller; BD, Sparks, MD) for 3 h and frozen in 15% glycerol-LB medium at −80°C for later PCR confirmation and select genetic marker screening. Also, for each sample up to five randomly selected colonies suspected to be E. coli on the EMB agar plates were subcultured in LB broth and stored at −80°C for later PCR confirmation and select genetic marker screening.

DNA extraction and PCR screening.

Frozen sample isolates, from both the prechallenge and the challenge experiments, were streaked for colony isolation onto LB agar (Bacto agar; BD, Sparks, MD) and incubated at 37°C for 18 to 20 h. One colony per sample isolate was selected for DNA extractions using a modified boiled-colony (BC) method (20), and DNA extractions were performed on a minimum of five isolates per sample (when possible). Each colony was boiled at 100°C in 50 μl of molecular-grade nuclease-free water (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for 20 min. The samples were vortexed for 5 to 10 s before and after boiling. The samples were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a separate tube and used as template DNA as described by Gonzales et al. (22).

PCR confirmation and screening were done using a panel of 28 genetic markers that included virulence factors, O-antigen genes, and selected prophage regions on the OpenArray System from Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA) (22). The choice of the 28 genetic markers for the panel included a primer pair to detect the 16S RNA DNA for E. coli in addition to the most relevant virulence markers for human-pathogenic EHEC, such as Shiga toxin genes (stx1 and stx2), the adhesin called intimin (eae) and the enterohemolysin gene (hly), three variants of the translocated intimin receptor (tir) that is part of the type III secretion system of E. coli, and the flagella marker for H7 (fliC). The panel had markers for seven serotypes of E. coli among which O157, two targets within rpoS, and the remaining markers are prophage markers aimed at subtyping the E. coli. The panel is described in detail in Gonzales et al. (20).

The OpenArray System is a real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) platform, where each PCR is conducted in a 33-nl volume on an open-array plate the size of a microscope slide. The open-array features 3,072 nano through-holes, arranged into 48 subarrays per plate. The result is more than 3,000 independent real-time PCRs performed on each plate and up to three plates per run in less than 4 h using SYBR green I or TaqMan chemistries (36).

OpenArray PCR.

For real-time PCRs performed in the OpenArray System, PCR master mixes contained 1.0× LightCycler DNA Master SYBR green I (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN), 1.0× SYBR green I (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.5% glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.2% Pluronic F-68 (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1.0 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 8.0% Hi-Di Formamide (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA), prepared in a 186.4-μl total volume, sufficient for one OpenArray plate. Genomic DNA samples were loaded into the OpenArray plate using the OpenArray NT Autoloader according to the manufacturer's protocol. The real-time qPCR array thermal cycler protocol follows a standard three-step protocol with an annealing temperature of 55°C, followed by a product melt curve analysis consisting of an increase from 70°C to 94°C with image collection every 0.25°C.

Post-PCR analysis.

Post-PCR analyses evaluated melting temperatures (Tm) and threshold cycle values (CT), in addition to verifying the sigmoid shape of the amplification graphs using the OpenArray software. Samples were considered positive if the Tm analysis showed the correct product with consistency between replicates and if the product had a CT value of <25 with an acceptable CT confidence value as calculated using a proprietary algorithm (22, 36). The CT values were generated based on a threshold value that applied to all samples. Although the algorithm for the threshold value is not revealed by the company that makes the OpenArray platform, it is applied to all samples, and mistakes would have been introduced in the same way for all samples. Presence and absence data for the 28 genetic markers in all sample isolates were collected, and genotype numbers were assigned to each unique profile of target genes.

Statistical analysis.

Presence and level of E. coli O157:H7 in examined samples over the duration of the study period were described and summarized. Logistic regression was used to analyze the dichotomous outcome of the presence or absence of the challenge strains in the collected RAMS samples between the study groups using FRIK 47 as a baseline. Logistic regression was also used in the same manner to analyze the dichotomous outcome of the presence or absence of FRIK 1641 and the variant lacking the Shiga toxin gene (stx2; FRIK 1641 Δstx2) in the collected RAMS in group 3. In the models the test outcome (presence or absence) was the dependent variable, and the challenge strain was the independent variable. The proportions of RAMS culture positive for the challenge strain over the entire period was calculated for each group by dividing the number of positive RAMS by the total number of RAMS collected from all steers in each group. K-means partitioning was used to cluster the genotypes found during the experiments into subgroups according to their relatedness in the genetic markers detected according to Borcard et al. (7). All calculations were conducted in R, version 2.13.1 (43).

RESULTS

During the 20-day prechallenge time period, 10 RAMS were collected from each steer, and 50 environmental samples were taken from each pen on alternate days. All RAMS and environmental samples were negative for wild-type E. coli O157:H7, as confirmed by bacteriological cultures and PCR during the prechallenge time period. The steers remained healthy throughout the trial. No elevated body temperatures were observed. The days and steer identification numbers when the challenge strains were detected are shown in Table 1, and the concentrations shed of each challenge strain are shown in Table 2. As highlighted in Table 1, steers exhibited periods of continuous shedding, periods of intermittent shedding, and periods of no shedding. Assuming no change in shedding status between two sample collections, in this study, continuous shedding intervals are defined by two or more consecutive positive RAMS. Intermittent shedding is defined by the interruption of consecutive shedding periods by one or more sampling periods of no detection of the E. coli O157:H7 challenge strains where the beginning of a new shedding period may indicate either recolonization or another episode of shedding.

Table 1.

Results of sample testing for E. coli O157:H7 by day over the trial period

| Group no. | Inoculuma | Steer no. | Room | RAMS sample results by day of detectionb |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 30 | ||||

| 1 | FRIK 47 | 1 | A | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 2 | A | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 3 | A | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | ||

| 4 | A | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | ||

| 5 | A | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | ||

| 6 | A | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 2 | FRIK 47 | 7 | A | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | +c | − |

| 8 | A | + | + | + | +d | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | ||

| 9 | A | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | ||

| 10 | A | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 11 | A | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 12 | A | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||

| 3 | FRIK 1641 | 13 | B | +e | +e | +e | +e | +e | +e | +e | +e | − | + | +e | − | − | − | − |

| 14 | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +e | + | + | +e | +f | ||

| 15 | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +e | +e | +f | +e | + | + | +e | +f | ||

| 16 | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 17 | B | +f | +f | +e | +e | +e | − | − | − | − | +f | − | − | + | − | − | ||

| 18 | B | − | − | − | − | − | +e | − | +e | +e | +e | +e | + | +e | +e | +e | ||

| 4 | FRIK 2533 | 19 | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +f | +e | +e |

| 20 | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +e | ||

| 21 | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +e | +f | +e | +e | ||

| 22 | B | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| 23 | B | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +e | +e | ||

| 24 | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +e | +e | ||

On day 1 of the experiment, animals were inoculated with 106 CFU/ml of one of the three E. coli O157:H7 challenge strains.

Presence (+) or absence (−) of the challenge strain is indicated.

Shedding a mix of FRIK 47 and FRIK 1641 Δstx2.

Shedding a mix of FRIK 47 and noninoculation O157:H7.

Shedding FRIK 1641 Δstx2.

Shedding a mix of FRIK 1641 and FRIK 1641 Δstx2.

Table 2.

The number of E. coli O157:H7-positive samples and concentration ranges by steer after oral challenge

| Group no. | Steer no. | E. coli O157:H7 challenge strain | Detection of E. coli O157:H7a |

Range of CFU/ml of generic E. coli | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of positive samplesb | Day p.i. of first positive sample | Range of CFU/ml | No. of days p.i. to maximum CFU count | ||||

| 1 | 1 | FRIK 47 | 1 | 2 | 1.1 × 101 | 2 | 1.0 × 103–5.8 × 104 |

| 2 | FRIK 47 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 3.0 × 103–4.4 × 104 | |

| 3 | FRIK 47 | 9 | 2 | 1.0 × 101–1.1 × 104 | 8 | 3.0 × 103–7.2 × 104 | |

| 4 | FRIK 47 | 13 | 2 | 0.5 × 101–1.6 × 104 | 10 | 4.0 × 103–1.4 × 105 | |

| 5 | FRIK 47 | 8 | 2 | 0.1 × 101–1.1 × 105 | 16 | 3.0 × 103–3.0 × 105 | |

| 6 | FRIK 47 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 1.0 × 103–9.0 × 104 | |

| 2 | 7 | FRIK 47 | 9 | 2 | 0.1 × 101–1.1 × 105 | 8 | 4.0 × 103–4.1 × 105 |

| 8 | FRIK 47 | 10 | 2 | 0.2 × 101–3.2 × 104 | 12 | 2.0 × 103–3.9 × 105 | |

| 9 | FRIK 47 | 11 | 2 | 0.2 × 101–1.0 × 104 | 8 | 1.0 × 103–3.0 × 106 | |

| 10 | FRIK 47 | 13 | 4 | 0.1 × 101–2.7 × 104 | 18 | 1.0 × 103–1.3 × 106 | |

| 11 | FRIK 47 | 9 | 2 | 11–5.4 × 104 | 22 | 1.0 × 103–1.6 × 105 | |

| 12 | FRIK 47 | 8 | 12 | 0.5 × 101–1.7 × 104 | 28 | 1.0 × 103–7.1 × 104 | |

| 3 | 13 | FRIK 1641 | 10 | 2 | 2.4 × 101–1.1 × 105 | 10 | 2.0 × 103–1.2 × 105 |

| 14 | FRIK 1641 | 5 | 22 | 5.4 × 101–1.1 × 105 | 26 | 1.0 × 103–9.6 × 105 | |

| 15 | FRIK 1641 | 7 | 16 | 0.2 × 101–6.7 × 104 | 20 | 7.5 × 103–4.9 × 105 | |

| 16 | FRIK 1641 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 2.0 × 103–1.9 × 105 | |

| 17 | FRIK 1641 | 7 | 2 | 0.2 × 101–4.5 × 103 | 6 | 3.0 × 103–1.2 × 105 | |

| 18 | FRIK 1641 | 9 | 12 | 0.2 × 101–1.4 × 104 | 18 | 1.0 × 103–6.9 × 105 | |

| 4 | 19 | FRIK 2533 | 3 | 26 | 0.8 × 101–1.6 × 103 | 30 | 1.7 × 104–1.2 × 105 |

| 20 | FRIK 2533 | 1 | 30 | 4.7 × 102 | 30 | 1.0 × 103–7.0 × 104 | |

| 21 | FRIK 2533 | 4 | 24 | 5.6 × 102–1.1 × 105 | 28 | 1.0 × 103–2.5 × 106 | |

| 22 | FRIK 2533 | 1 | 2 | 1.8 × 101 | 2 | 1.0 × 103–1.3 × 106 | |

| 23 | FRIK 2533 | 3 | 2 | 0.1 × 101–0.4 × 101 | 2 | 5.5 × 103–2.0 × 105 | |

| 24 | FRIK 2533 | 2 | 24 | 0.6 × 101–9.0 × 102 | 30 | 1.7 × 104–9.7 × 105 | |

Each steer was orally challenged with 106 CFU of one of three E. coli O157:H7 strains, followed by collection of RAMS on alternate days over 30 days. NA, not available; p.i., postinoculation.

Over the 30-day trial period, 15 RAMS were collected from each steer.

It was found that steers inoculated with FRIK 1641 shed the strain and also a variant that lacked the Shiga toxin gene (stx2; FRIK 1641 Δstx2). The −80°C freezer stock of the FRIK 1641 isolate used to generate the inoculum for that strain was confirmed to be stx2 positive by PCR before inoculation. Three serial passages of FRIK 1641 from the −80°C freezer stock used to produce the inoculum through LB agar plates and 24 h of incubation at 37°C did not result in the observation of the Δstx2 variant of FRIK 1641 as confirmed by PCR (data not shown). It was concluded later that the Δstx2 variant of FRIK 1641 was first detected during the period of the 30-day sampling postinoculation. The loss of stx genes and other genomic modifications have been reported previously during sequential analysis of human and cattle isolates (35).

FRIK 47 detection in groups 1 and 2.

Over the 30-day study period, 180 RAMS were collected from steers challenged with FRIK 47. Of these, 94 (52%) RAMS were positive for FRIK 47, with detection per steer ranging from 1 positive RAMS to 13 positive RAMS over the sampling period (Table 1). The proportion of FRIK 47 detected in the RAMS was significantly greater than the proportions of FRIK 1641, FRIK 1641 Δstx2, or FRIK 2533 detected in the RAMS from group 3 and group 4 (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 3.

Counts of the number of each E. coli O157:H7 strain detected out of the total number of RAMS taken per challenge group

| E. coli O157:H7 strain | No. of positive RAMS | Total no. of RAMS |

|---|---|---|

| FRIK 47 | 94 | 180 |

| FRIK 1641 | 13 | 90 |

| FRIK 1641 Δstx2 | 32 | 90 |

| FRIK 2533 | 2 | 90 |

Table 4.

Comparison of the proportions of positive RAMS for each challenge strain per number of total RAMS collected using logistic regression

| Baseline and comparison strain | Value of logistic regression statistic for proportion of positive RAMSa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE (β) | z value | P value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Relative to FRIK 47 | |||||

| Intercept | 0.0890 | 0.1492 | 0.5960 | 0.5511 | 1.0930 (0.8159–1.4660) |

| FRIK 1641 | −1.8678 | 0.3349 | −5.5770 | 2.45 × 10−8 | 0.1545 (0.0771–0.2893) |

| FRIK 1641 Δstx2 | −0.6837 | 0.2660 | −2.5700 | 0.0102 | 0.5048 (0.2974–0.8457) |

| FRIK 2533 | −3.8731 | 0.7305 | −5.3020 | 1.15 × 10−7 | 0.0208 (0.0033–0.0686) |

| Relative to FRIK 1641 | |||||

| Intercept | −1.7789 | 0.2999 | −5.9320 | 2.98 × 10−9 | 0.1688 (0.0896–0.2930) |

| FRIK 1641 Δstx2 | 1.1841 | 0.3720 | 3.1830 | 0.0015 | 3.2679 (1.6069–6.9703) |

SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In both groups, the E. coli O157:H7 CFU concentrations detected were in the range of a minimal detection of ≤101 CFU/ml to 105 CFU/ml (Table 2). FRIK 47 concentrations followed a wave-like pattern where concentrations were initially low, rose to peak concentrations (average of 5.6 days; standard deviation [SD], 1.34) then declined to ≤101 CFU/ml (average 6.8 days; SD, 1.58). This shedding pattern was observed in 7 of the 12 steers. Generic E. coli concentrations remained at or above 104 CFU/ml on most sampling days, with 106 CFU/ml being the peak concentration detected (Table 2). Based on the visual examination of the data, there did not seem to be any correlation between the shedding concentrations of FRIK 47 and the generic E. coli.

On the first day postinoculation shedding was detected in 8 out of 12 (67%) steers. Detection of FRIK 47 shedding in steer 1 was confirmed only on day 2 (1.1 × 101 CFU/ml), and steer 2 and steer 6 did not shed a detectable level of the challenge strain during the sampling period. Steer 3 and steer 5 were found to have intermittent shedding patterns, with 60% and 53% of RAMS collected being positive for FRIK 47, respectively, and nonshedding periods averaged 6.5 days (SD, 1.92). Steer 4 shed almost continuously during the entire sampling period, with 86.7% of RAMS positive for FRIK 47.

In group 2, all six animals had detectable colonization of the challenge strain, FRIK 47, and had continuous shedding periods lasting, on average, 11.8 days (SD, 5.9) with a minimum of two consecutive positive sampling days and a maximum of 10 consecutive sampling days. Intermittent shedding patterns were found in steer 7, steer 8, steer 11, and steer 12 with 60%, 73%, 60%, and 53.3% of RAMS positive for FRIK 47, respectively, and nonshedding periods averaged 10 days (SD, 1.6). Steer 9 and steer 10 shed almost continuously during the entire sample period, with 86.7% of RAMS positive for the challenge strain. The difference in shedding frequencies between groups 1 and 2 challenged with the same strain may be a consequence of the random presence of two steers in group 1 that did not shed at all during the entire study period.

In two steers, 7 and 8, there was PCR detection of two different E. coli O157:H7 strains on 1 out of 15 sampling days. In steer 7 on day 28 four out the five suspect O157:H7 isolates screened were FRIK 1641 Δstx2 (Table 5, genotype 3). In steer 8 on day 8 one out the five suspect O157:H7 isolates screened was a nonchallenge E. coli O157:H7 strain that was similar to FRIK 47 with the only difference in three prophage markers (9330C, 07-N, and 09-C) (Table 5, genotype 5).

Table 5.

Presence and absence data for the 28 genetic markers run on the OpenArray System from including genotype numbers for each distinct profile

| Strain type | Genotypeb | Genetic profile by gene groupa |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virulence/regulatoryc |

Serotype-specific (serotype) |

Prophage marker |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16S rRNA | stx1 | stx2 | eae | hly933 | tir (1) | tir (2) | tir (3) | rpoS (a) | rpoS (b) | fliCd | rfbE (O157) | wzx (O121) | wbdI (O111) | wzx (O26) | wzx (O145) | wzx (O45) | wzx (O103) | Z2322 | 9330C | 02-N | 07-N | 09-C | 011-C | R1-N | R4-N | ||

| EHEC serotype strains | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| O157:H7 | 1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| O157:H7 | 2 | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| O157:H7 | 3 | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| O157:H7 | 4 | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − |

| O157:H7 | 5 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| O121 | 6 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| O145 | 7 | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| O103 | 8 | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − |

| Generic E. coli | 9 | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| 10 | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 11 | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | |

| 12 | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | |

| 13 | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 14 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| 15 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | |

| 16 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 17 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | |

| 18 | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 19 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 20 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | |

| 21 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| 22 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | |

| 23 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | |

| 24 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 25 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 26 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 27 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 28 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 29 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 30 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | |

| 31 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 32 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

| 33 | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | |

Genetic profiles are representative of presence (+) and absence (−) data collected from genetic screening of isolates cultured from RAMS and environmental samples. The OpenArray system is from Applied Biosystems Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA).

Genotypes 1, 2, and 4 represent the challenge strains FRIK 47, FRIK 1641, and FRIK 2533.

Three variants (1 to 3) of the tir gene and two targets (a and b) within rpoS were included.

fliC was included as a flagellar marker for H7.

FRIK 1641 detection in group 3.

Over the sampling period it was found that steers were shedding a combination of the challenge strain, FRIK 1641, a variant of the challenge strain without the Shiga toxin gene (FRIK 1641 Δstx2) or both subtypes (Table 1). Of the 90 RAMS collected 39 (42%) were positive for either the challenge strain (18.4%), the variant FRIK 1641 Δstx2 (68.4%), or a mixture of both (13.2%). The proportion of FRIK 1641 Δstx2 detected in the RAMS was significantly greater than the proportion of FRIK 1641 detected (Table 4). On day 2, only two out of the six steers (33%) were positive for either the challenge strain or the variant or both. These two steers accounted for 92.3% of RAMS samples that were positive from day 2 until day 14. Delayed onset of shedding postinoculation (>10 days) was seen in steers 14, 15, and 18. Steer 16 was never found to shed the challenge strain or the variant. Given successful colonization of FRIK 1641 or FRIK 1641 Δstx2, wave-like patterns in shedding concentrations similar to shedding of FRIK 47 were seen in three out of the six steers, with concentrations varying from ≤101 CFU/ml to 106 CFU/ml (Table 2). Similar to findings with FRIK 47, there did not seem to be any correlation between the shedding concentration of FRIK 1641 or its variant and the generic E. coli, based on visual examination of the data. The CFU concentrations for all steers in group 3 are representative of FRIK 1641 or the variant of the inoculation strain without the Shiga toxin gene (FRIK 1641 Δstx2) or both subtypes.

FRIK 2533 detection in group 4.

Shedding frequency of FRIK 2533 in the steers in group 4 was considerably different than the shedding frequencies of FRIK 47 and FRIK 1641 (Table 1). Detection of FRIK 2533 in RAMS samples from all six steers was close to zero with two exceptions: on day 2 RAMS were positive for the challenge strain FRIK 2533 in two out of the six steers (steer 22 and steer 23) with relatively low CFU concentrations of 1.8 × 101 and 0.4 × 101 CFU/ml. Throughout the study period generic E. coli concentrations in this group were similar to those observed in the other experimental groups (Table 2), and based on visual examination of the data, there did not appear to be any correlation between the E. coli O157:H7 and the generic E. coli shed. Samples for all steers remained negative after day 2 for E. coli O157:H7 until day 24, when several steers began shedding the challenge strain FRIK 1641 or its variant (FRIK 1641 Δstx2) until the end of the sampling period (Table 1).

Environmental sampling during challenge experiments.

In addition to the collection of the RAMS samples from the steers, environmental samples were taken on the same sample days from hides, feed troughs, drinking water, water cup runoff (water ropes), and housing pens (gate ropes). In total in each pen, 15 samples of each type were collected, with the exception of the rope samples (Table 6). On six separate sampling days in pens 1 and 2, the rope samples were unable to be retrieved after placement due to what is assumed to be steer consumption.

Table 6.

Results of sample testing for E. coli O157:H7 by day over the trial period

| Group no. | Sample typea | Room |

E. coli O157:H7 detection by sampling dateb |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 30 | |||

| 1 | Hide | A | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Water | A | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Feed trough | A | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Gate ropes | A | + | − | − | + | NA | − | + | + | + | +c | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Water ropes | A | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | NA | |

| 2 | Hide | A | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| Water | A | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Feed trough | A | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Gate ropes | A | − | − | NA | + | − | NA | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | NA | |

| Water ropes | A | − | − | − | − | + | NA | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 3 | Hide | B | − | − | − | +d | − | − | − | − | +d | +d | − | +d | +d | − | |

| Water | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Feed trough | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +d | − | − | |

| Gate ropes | B | − | +d | − | +d | +d | − | − | − | +d | +d | +d | +d | +d | +d | +d | |

| Water ropes | B | +d | − | − | +d | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +d | − | − | − | |

| 4 | Hide | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +d | +d | +d |

| Water | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Feed trough | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +d | − | − | |

| Gate ropes | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +d | +d | +d | |

| Water ropes | B | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | +d | +d | |

Five types of environmental samples were collected from each pen: hide (composite sponge sample); water (direct sample); feed trough (composite sponge sample); gate ropes and water ropes (nylon rope samples).

NA, not available.

Detected a mix of FRIK 47 and FRIK 1641 Δstx2.

Detected FRIK 1641 Δstx2.

Environmental contamination with E. coli O157:H7 was largest in the middle of the study for groups 1 and 2 and toward the end of the study for groups 3 and 4 (Table 6). In that regard, the extent of environmental contamination somewhat coincided with the frequency of animal shedding. However, in each of pens 1, 2, and 3, the detection levels and concentrations of the E. coli O157:H7 challenge strains in the environmental samples were lower than those from RAMS on any given sampling day (Table 7). In all pens, the challenge strains were not detected in any of the water samples over the entire study period. On the sampling days in each pen there were generic E. coli cells cultured from most environmental samples, but based on visual examination of the data, there did not seem to be any correlation with the frequency of detection of the challenge strains. In pen 1, the detection of two of E. coli O157:H7 strains was found on day 20 in the gate rope samples (Table 6). In pen 4, the detection of the challenge strain FRIK 2533 was not found in any of the environmental samples. However, near the end of the sampling period (day 26), detection of FRIK 1641 Δstx2 was confirmed in pen 4.

Table 7.

Numbers of E. coli O157:H7 isolates detected in the housing environment

| Group no. | Sample typea | No. of samples | Detection of E. coli O157:H7 |

Range of CFU/ml of generic E. coli | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of positive samples | Range of CFU/ml | ||||

| 1 | Hide | 15 | 4 | 1.4 × 101–2.8 × 101 | 1.5 × 101–1.5 × 104 |

| Feed trough | 15 | 1 | 0.6 × 101 | 9.0 × 101–9.8 × 104 | |

| Water | 15 | 0 | NAb | 1.0 × 101–1.1 × 104 | |

| Gate ropes | 14 | 6 | 2.4 × 101–1.2 × 103 | 1.5 × 102–1.2 × 105 | |

| Water ropes | 14 | 1 | 9.9 × 101 | 4.1 × 102–1.2 × 104 | |

| 2 | Hide | 15 | 8 | 0.3 × 101–2.4 × 102 | 1.5 × 101–1.5 × 104 |

| Feed trough | 15 | 1 | 1.72 × 102 | 2.1 × 102–9.8 × 104 | |

| Water | 15 | 0 | NA | 1.0 × 101–1.2 × 104 | |

| Gate ropes | 12 | 7 | 2.2 × 101–1.8 × 103 | 1.4 × 103–1.2 × 105 | |

| Water ropes | 14 | 2 | 8.3 × 101–2.6 × 102 | 2.7 × 102–1.2 × 104 | |

| 3 | Hide | 15 | 5 | 1.3 × 101–1.4 × 103 | 2.0 × 101–1.5 × 104 |

| Feed trough | 15 | 1 | 2.2 × 102 | 9.0 × 101–1.1 × 104 | |

| Water | 15 | 0 | NA | 1.5 × 101–4.6 × 102 | |

| Gate ropes | 15 | 10 | 1.7 × 101–8.4 × 103 | 1.5 × 101–2.2 × 104 | |

| Water ropes | 15 | 3 | 6.2 × 101–2.5 × 102 | 3.0 × 101–9.4 × 103 | |

| 4 | Hide | 15 | 3 | 8.1 × 101–6.6 × 102 | 1.5 × 101–1.1 × 104 |

| Feed trough | 15 | 1 | 2.0 × 103 | 7.0 × 101–9.8 × 104 | |

| Water | 15 | 0 | NA | 2.0 × 101–5.3 × 103 | |

| Gate ropes | 15 | 3 | 6.3 × 101–1.2 × 103 | 8.0 × 101–1.2 × 105 | |

| Water ropes | 15 | 2 | 4.7 × 101–4.4 × 103 | 2.4 × 102–1.2 × 104 | |

Five types of environmental samples were collected from each pen: hide (composite sponge sample); water (direct sample); feed trough (composite sponge sample); gate ropes and water ropes (nylon rope samples).

NA, not available.

Genetic profiles.

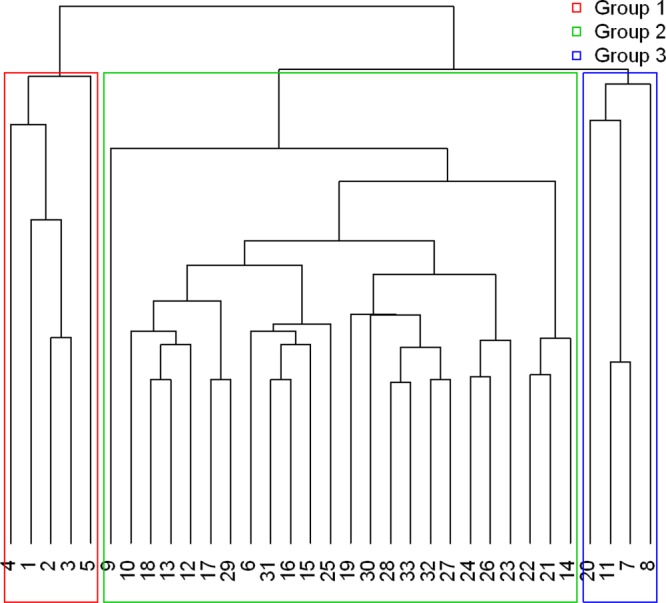

Using the EHEC panel reported by Gonzales et al. (22), presence and absence data were generated for 2,411 E. coli isolates, of which 953 were presumptively identified as E. coli O157:H7. Among the isolates suspected to be E. coli O157:H7, 71% were isolated from RAMS, and 29% were isolated from environmental samples. Thirty-three distinct “genotypes” or gene marker profiles were identified based on the panel of 28 genetic markers (Table 5). These profiles included four different EHEC serotypes (O157:H7, O103, O121, and O145) and multiple variations (25 genotypes total) of generic commensal E. coli. Using K-means partitioning to cluster the E. coli genotypes into subgroups resulted in three clusters with distinct markers (Fig. 1). The three inoculation strains were in a separate cluster from the generic E. coli, confirming their specific potential for human virulence. Furthermore, two different groups within the generic E. coli carrying selected virulence markers (stx, eae, hly, and tir) were found.

Fig 1.

The clusters of genotypes after K-means partitioning of the E. coli isolates represented in Table 5. Three clusters with distinct genetic markers are shown, where the challenge strains (group 1) are in a separate cluster from the generic E. coli (groups 2 and 3). Groups 2 and 3 highlight clustering among the genotypes for generic E. coli, with group 3 representing genotypes carrying select virulence markers (stx, eae, hly, and tir).

DISCUSSION

By comparing the shedding patterns and concentrations of the selected E. coli O157:H7 strains (FRIK 47, FRIK 1641, and FRIK 2533) shed by the cattle under study, distinct abilities of each strain to colonize the bovine GI tract were observed. The data collected revealed strain-specific shedding patterns, durations of shedding, and variations in concentrations shed for each of the selected E. coli O157:H7 challenge strains. FRIK 47 appeared to be more effective at colonizing cattle than FRIK 1641 and FRIK 2533, as shown by the statistically higher proportion of positive RAMS. The results of this study demonstrate the value of investigating E. coli O157:H7 strains of different genotypes in an effort to explain the temporal and animal-to-animal variability in the presence of E. coli O157:H7 in field studies (47, 53). Moreover, these results demonstrate the value of investigating EHEC strains of different genotypes and origins for identification of colonization factors and new targets of intervention strategies. Preharvest intervention targets could be developed based on the presence or absence of gene markers, subtypes, and by comparison with other EHEC strains that persistently colonize cattle.

The selection of the challenge strains was based on their differences in origins, their variations in genotypes, and their expected potential for colonization. Both FRIK 47 and FRIK 1641 (both variants) were able to persist throughout the study period in both the steers and the environment; however, FRIK 2533 was unable to persist. Large variations in the shedding patterns for all three challenge strains of E. coli O157:H7 were observed. For example, in three out of five steers in the FRIK 1641 challenge group, there was a prolonged delay (>10 days) before the onset of shedding postinoculation, possibly indicating colonization due to reexposure from contaminated environment or colonized steers in the group. Also, three steers shed no detectable levels of E. coli O157:H7 throughout the study. The absence of shedding E. coli O157:H7 postinoculation was observed despite the inoculation dose of 106 CFU and the continuous exposure to E. coli O157:H7 through infected cattle and the contaminated environment. This failure of shedding postinoculation may be due to a natural resistance, the shedding of concentrations below the detection limit, or no colonization. Similar to the findings in this study, large variation in shedding patterns, including intermittent shedding (14, 44), and concentration of E. coli O157:H7 have been reported (46) in addition to no shedding of the pathogens after experimental challenge (27, 48).

Given successful colonization, strains FRIK 47 and FRIK 1641 were observed to have similar wave-like patterns of shedding, with a peak in the number of E. coli cells several days (average of 6 days; SD, 1.3) postinoculation. However, despite the similar concentrations, there was large variation observed between the onset of colonization and the length of continuous shedding intervals between the two strains, as seen in Table 1. It remains unknown as to how the variation in genetic markers between FRIK 47 and FRIK 1641 may impact their ability to colonize cattle. In a study by Döpfer et al. (17), the length of the shedding intervals necessary for propagation of E. coli through populations of beef cattle was shorter for E. coli with multiple virulence genes, i.e., Shiga toxins and intimin, than those E. coli encoding only Shiga toxins (17). Also previous research has shown, that E. coli bacteria without Shiga toxin genes are lost more frequently than to E. coli with Shiga toxins (18).

An unexpected observation in the study was the detection of a variant form of the challenge strain FRIK 1641 in group 3 which lacked the stx2 gene. It appeared that FRIK 1641 was genetically unstable in vivo, as evidenced by the recovery of both the challenge strain and the variant at day 1 following inoculation. Both FRIK 1641 and the variant (FRIK 1641 Δstx2) were detected throughout the sampling period, indicating that the genetic change(s) had little effect on shedding. However, only FRIK 1641 Δstx2 was detected in the environment. It can only be speculated as to whether the lack of stx2 in the FRIK 1641 variant influenced colonization and shedding postinoculation or whether loss of the stx2 gene changed the ability to persist in and transmit to the environment.

The group of steers inoculated with strain FRIK 2533 did not shed the strain persistently. Despite its dairy farm origin, the strain may lack genetic determinants necessary for bovine colonization. It is known that this strain lacks the hemolysin gene, hly (Table 5), which suggests that this gene or another on the pO157 plasmid plays a role in colonization. Whether the lack of the hemolysin gene or the inoculation dose is the cause of FRIK 2533 not persisting in the current study population remains speculative. It is possible that the lack of the pO157 plasmid implies the lack of other genetic markers that are crucial to the survival and colonization of the bovine gastrointestinal tract (32). One study has shown that the lack of the pO157 plasmid reduces the pathogens' ability to colonize the mucosa at the recto-anal junction in cattle, (31); however, the persistence of this strain (without pO157) was detectable for longer periods of time (1 to 2 weeks) in comparison to the findings in this study (1 day).

Despite ardent measures to prevent carryover, the variant FRIK 1641 Δstx2 was able to spread into the environment in group 1 (day 20; gate ropes), one steer in group 2, and 5 steers and the environment in group 4. That the time interval until the FRIK 1641 variant was detected for group 2 was 28 days and for group 4 was 24 days postinoculation of group 3 (Table 1) implies that the potential carryover between the groups did not occur due to inoculation at the start of the study. The unintentional spread highlights the potential ability of this organism to colonize cattle and persist in the environment even though it lacks the Shiga toxin gene.

The oral challenge model used in this study included relevant parameters for the colonization and persistence of E. coli O157:H7 in cattle, among which are low infectious dose exposure relevant to “real-world” exposure (34, 47, 53), young cattle, group housing, and cleaning of the environment. It has been shown that age-related effects, along with dose, may influence the probability of colonization or shedding in cattle. In a study done by Besser et al. (6), a low infectious dose of <500 CFU was sufficient to cause fecal excretion of E. coli O157:H7 in high numbers for prolonged periods in young calves. However, in an experimental study conducted by Cray and Moon (14), it was found that a dose of 107 CFU was insufficient to colonize all adult cattle. It is estimated that fewer than 10% of dairy cattle shed the pathogen in their feces, with findings that weaned calves (4 to 6 months of age) have higher prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 than both preweaned calves and adult cattle (19, 24, 53). In the current study, it was expected that the majority of the study population would likely become colonized and shed the challenge E. coli O157:H7 strains.

The levels of E. coli O157:H7 excreted into the environment reached ≥105 CFU/ml, but these concentrations were detected only for a few sampling days per steer and cannot explain the difference in shedding patterns of the steers. Persistent colonization was detected for the duration of several weeks in some steers either as continuous shedding or shedding patterns interrupted by less than 2 days. Even the highest shedding concentrations of E. coli O157:H7 (>105 CFU/ml) into the environment did not result in highly contaminated hides (or other environmental samples), in contrast to other reports (2, 41). The cleaning regimen of pens may have resulted in decreased hide contamination and prevention of the accumulation of manure on the pen floors.

In previous studies, intermittent shedding patterns were explained by intermittent environmental exposure to the organism or by the persistence of an undetectable number of bacteria in the digestive tract, where periodical replication of the bacteria leads to intermittent detection (23). In this study, most of the environmental samples positive for E. coli O157:H7 were detected in hide samples and rope samples. These findings support the idea that if reoccurring colonization was the cause for intermittent shedding, those patterns most likely resulted from the steers' social interactions and their contact with the ropes, which were considered to be representative of their environment. Several studies have reported that this intermittent environmental exposure can be caused by contaminated water, feed sources, or bedding (15, 19, 30, 48). However, in this study contaminated water was not detected, minimal detection was found in the feed troughs, and no bedding was provided to the steers. So these are all unlikely causes of the observed intermittent shedding and pathogen persistence.

The gene panel reported by Gonzales et al. (22) was a useful tool for characterizing the genetic markers of the isolates collected from the current study in a time-efficient and discriminatory manner. The genetic markers contained in the panel allowed for differentiation of the challenge strains and the generic E. coli within samples. Using K-means partitioning to cluster the genotypes of the E. coli selected from the experimental samplings into subgroups resulted in three clusters with distinct markers. The three inoculation strains were in a separate cluster from the generic E. coli and from the generic E. coli carrying selected virulence markers (stx, eae, hly, and tir). Subgroups of generic E. coli isolates could be distinguished based on the presence of markers such as Shiga toxins and different prophage regions. Variation in prophage regions is a major factor in generating the genomic diversity among O157 strains (40). In this study, that diversity was confirmed using a selection of prophage regions for characterizing the strains of E. coli O157:H7 (Table 5).

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the strain-specific genotypes of E. coli O157:H7, which happen to be of different ecological origins, are important factors in determining the occurrence and persistence of E. coli O157:H7 shedding in the bovine host. Based on the results of this study, along with previous studies (8, 17, 21a), the role that specific genetic markers play in the ability of certain strains of E. coli O157:H7 to colonize, transmit, and persist in cattle needs to be explored further. Moreover, the observed differences between O157:H7 strains may partially explain the observed variability in the detection of this pathogen in the field studies and suggests that the type and intensity of measures to control this pathogen at the preharvest level may need to be strain specific. The capabilities of the gene panel reported by Gonzales et al. (22) to subtype E. coli based on prophage regions has proven repeatable in distinguishing between the study strains, and future work may allow for even greater subtyping of closely related strains of E. coli O157:H7 using the prophage regions. The ability to efficiently distinguish between various strains of E. coli O157:H7 in cattle will be crucial for further understanding of the strain-specific ecology and epidemiology that may lead to the development of strain-specific preharvest interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation grant NSF-EF-0913042 to D.D. funded under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Alexander ER, et al. 1995. Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreak linked to commercially distributed dry-cured salami—Washington and California. JAMA 273:985–986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arthur TM, et al. 2009. Longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in a beef cattle feedlot and role of high-level shedders in hide contamination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6515–6523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berry ED, Cutter CN. 2000. Effects of acid adaptation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on efficacy of acetic acid spray washes to decontaminate beef carcass tissue. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1493–1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Besser RE, et al. 1993. An outbreak of diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from Escherichia coli O157:H7 in fresh-pressed apple cider. JAMA 269:2217–2220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Besser TE, et al. 1997. Duration of detection of fecal excretion of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cattle. J. Infect. Dis. 175:726–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Besser TE, Richards BL, Rice DH, Hancock DD. 2001. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection of calves: infectious dose and direct contact transmission. Epidemiol. Infect. 127:555–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Borcard D, Gillet F, Legendre P. 2011. Numerical ecology with R. Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown CA, Harmon BG, Zhao T, Doyle MP. 1997. Experimental Escherichia coli O157:H7 carriage in calves. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:27–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caprioli A, Morabito S, Brugere H, Oswald E. 2005. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: emerging issues on virulence and modes of transmission. Vet. Res. 36:289–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Castillo A, Lucia LM, Goodson KJ, Savell JW, Acuff GR. 1999. Decontamination of beef carcass surface tissue by steam vacuuming alone and combined with hot water and lactic acid sprays. J. Food Prot. 62:146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Castillo A, et al. 2001. Lactic acid sprays reduce bacterial pathogens on cold beef carcass surfaces and in subsequently produced ground beef. J. Food Prot. 64:58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cobbold RN, et al. 2007. Rectoanal junction colonization of feedlot cattle by Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its association with supershedders and excretion dynamics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1563–1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cray WC, Casey TA, Bosworth BT, Rasmussen MA. 1998. Effect of dietary stress on fecal shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in calves. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1975–1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cray WC, Moon HW. 1995. Experimental infection of calves and adult cattle with Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1586–1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davis MA, Cloud-Hansen KA, Carpenter J, Hovde CJ. 2005. Escherichia coli O157:H7 in environments of culture-positive cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6816–6822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diez-Gonzalez F, Callaway TR, Kizoulis MG, Russell JB. 1998. Grain feeding and the dissemination of acid-resistant Escherichia coli from cattle. Science 281:1666–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Döpfer D, Geue L, de Bree J, de Jong MCM. 2006. Dynamics of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from German beef cattle between birth and slaughter. Prev. Vet. Med. 73:229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Döpfer D, et al. 2012. Dynamics of shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC) and their virulence factors in cattle. Prev. Vet. Med. 103:22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Faith NG, et al. 1996. Prevalence and clonal nature of Escherichia coli O157:H7 on dairy farms in Wisconsin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1519–1525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fratamico PM, DebRoy C, Strobaugh TP, Chen CY. 2005. DNA sequence of the Escherichia coli O103O antigen gene cluster and detection of enterohemorrhagic E. coli O103 by PCR amplification of the wzx and wzy genes. Can. J. Microbiol. 51:515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garber LP, et al. 1995. Risk factors for fecal shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in dairy calves. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 207:46–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a. Gautam R, et al. 2012. The strain-specific dynamics of Escherichia coli O157:H7 faecal shedding in cattle post inoculation. J. Biol. Dyn. 6:1052–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gonzales TK, et al. 2011. A high-throughput open-array qPCR gene panel to identify, virulotype, and subtype O157 and non-O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol. Cell. Probes 25:222–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grauke LJ, et al. 2002. Gastrointestinal tract location of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in ruminants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2269–2277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hancock DD, et al. 1994. The prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in dairy and beef cattle in Washington state. Epidemiol. Infect. 113:199–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hancock DD, Besser TE, Rice DH, Herriott DE, Tarr PI. 1997. A longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157 in fourteen cattle herds. Epidemiol. Infect. 118:193–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Herriott DE, et al. 1998. Association of herd management factors with colonization of dairy cattle by Shiga toxin-positive Escherichia coli O157. J. Food Prot. 61:802–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jeong KC, Kang MY, Kang JH, Baumler DJ, Kaspar CW. 2011. Reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 shedding in cattle by addition of chitosan microparticles to feed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2611–2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jordan D, McEwen SA, Lammerding AM, McNab WB, Wilson JB. 1999. Pre-slaughter control of Escherichia coli O157 in beef cattle: a simulation study. Prev. Vet. Med. 41:55–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kang DH, Koohmaraie M, Dorsa WJ, Siragusa GR. 2001. Development of a multiple-step process for the microbial decontamination of beef trim. J. Food Prot. 64:63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. LeJeune JT, Besser TE, Hancock DD. 2001. Cattle water troughs as reservoirs of Escherichia coli O157. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3053–3057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lim JY, Sheng HQ, Seo KS, Park YH, Hovde CJ. 2007. Characterization of an Escherichia coli O157:H7 plasmid O157 deletion mutant and its survival and persistence in cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2037–2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lim JY, Yoon JW, Hovde CJ. 2010. A brief overview of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its plasmid O157. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20:5–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Low C. 2003. VTEC O157 in cattle. Vet. Rec. 153:539. (Letter.). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Low JC, et al. 2005. Rectal carriage of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 in slaughtered cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:93–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mellmann A, et al. 2005. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in human infection: in vivo evolution of a bacterial pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41:785–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morrison T, et al. 2006. Nanoliter high throughput quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:e123 doi:10.1093/nar/gkl639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nataro JP, Kaper JB. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:142–201 (Erratum, 11:403.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Research Council 2001. Nutrient requirements of dairy cattle, 7th ed. National Academies Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nielsen EM, Tegtmeier C, Andersen HJ, Gronbaek C, Andersen JS. 2002. Influence of age, sex and herd characteristics on the occurrence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 in Danish dairy farms. Vet. Microbiol. 88:245–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ogura Y, et al. 2006. Complexity of the genomic diversity in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 revealed by the combinational use of the O157 Sakai oligoDNA microarray and the whole genome PCR scanning. DNA Res. 13:3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Omisakin F, MacRae M, Ogden ID, Strachan NJC. 2003. Concentration and prevalence of Escherichia coli O157 in cattle feces at slaughter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2444–2447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Perna NT, et al. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529–533 (Erratum, 410:240.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.R Core Development Team 2008. R: a language and environment for statistical computing, 2.13.1 ed R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rice DH, Sheng HQQ, Wynia SA, Hovde CJ. 2003. Rectoanal mucosal swab culture is more sensitive than fecal culture and distinguishes Escherichia coli O157:H7 colonized cattle and those transiently shedding the same organism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4924–4929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Riley LW, et al. 1983. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:681–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Robinson SE, Wright EJ, Hart CA, Bennett M, French NP. 2004. Intermittent and persistent shedding of Escherichia coli O157 in cohorts of naturally infected calves. J. Appl. Microbiol. 97:1045–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shere JA, Bartlett KJ, Kaspar CW. 1998. Longitudinal study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 dissemination on four dairy farms in Wisconsin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1390–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shere JA, et al. 2002. Shedding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in dairy cattle housed in a confined environment following waterborne inoculation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1947–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smith DR, et al. 2005. Use of rope devices to describe and explain the feedlot ecology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by time and place. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2:50–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tarr PI. 1995. Escherichia coli O157:H7: clinical, diagnostic, and epidemiological aspects of human infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang GD, Zhao T, Doyle MP. 1997. Survival and growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in unpasteurized and pasteurized milk. J. Food Prot. 60:610–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wells JG, et al. 1991. Isolation of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and other Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli from dairy cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:985–989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhao T, Doyle MP, Shere J, Garber L. 1995. Prevalence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in a survey of dairy herds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1290–1293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]