Abstract

The reaction of [(MeC5H4)2Ti(SH)2] with cyclic imines with the formula (CH2NR)3 gives 2-aza-1,3-dithiolato chelate complexes [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NR}] (1, R = Ph; 2, R = Me; 3, R = CH2Ph). These compounds demonstrate that azadithiolate ligands can exist on mononuclear metal centers. The complexes were characterized by 1H NMR spectroscopy, ESI-mass spectrometry, and X-ray crystallography. Variable-temperature 1H NMR studies reveal that the dithiolate ligands undergo ring inversion like other dithiatitanacyclohexanes. Treatment of [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] (1) with [Fe(benzylideneacetone)(CO)3] afforded [Fe2{(SCH2)2NPh}(CO)6] in good yield.

Keywords: Iron, Titanium, Hydrogenases, Azadithiolates, Sulfur

Introduction

Cofactors are efficient and interesting tools in enzymes, and consequently they enjoy the attention of chemists. Azadithiolate (S−–CH2–NH–CH2–S−) is one of the seven cofactors that make the H-cluster assembly of the enzyme [FeFe]-hydrogenase that catalyze the interconversion of protons and electrons with molecular hydrogen.[1] Small molecular models of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase indicate that azadithiolates function as proton relays to feed the distal iron center with protons, compensating for the intrinsically slow rates of protonation at metal centers.[2] The biosynthesis of the azadithiolate cofactor is under intense scrutiny among biologists, while chemists are striving to find new synthetic methods to incorporate it into the model systems. It is proposed that this cofactor arises by the condensation two equivalents of dehydroglycine with a 2Fe–2S center, and the former was proposed to arise through the degradation of glycine mediated by a radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) enzyme by the name HydG.[3]

Azadithiolates are derived from the unknown and probably unstable dithiols RN(CH2SH)2, formally a derivative of formaldehyde, an amine, and H2S.[4] In 2001, the first model complex of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase comprising an azadithiolate cofactor was synthesized by the treatment of Li2-[Fe2S2(CO)6] with (ClCH2)2NMe to afford [Fe2{(SCH2)2-NMe}(CO)6].[5] Since then azadithiolato diiron complexes have been described in more than eighty literature reports, which include 120 crystallographic studies. We have further explored the reactions of [Fe3(S)2(CO)9] and [Fe2(SH)2-(CO)6] with (CH2O)n/RNH2, (CH2NR)3 or (CH2)6N4 to give [Fe2{(SCH2)2NR}(CO)6].[6]

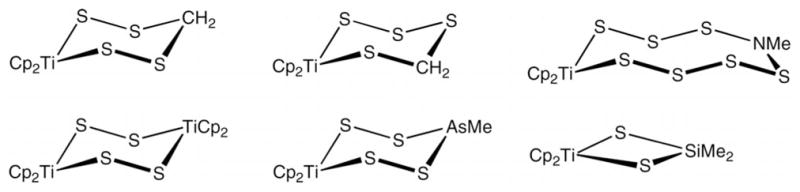

We wished to extend the reaction of [Fe2(SH)2(CO)6] with (CH2NR)3 to the preparation of mononuclear derivatives. Azadithiolato complexes are apparently unknown except for the diiron carbonyl derivatives. Monometallic azadithiolato complexes could prove useful for the construction of bimetallic derivatives of biomimetic value, and there may be applications beyond bioinorganic chemistry. As our approach, we focused on compounds that contain the M(SH)2 group, similar to [Fe2(SH)2(CO)6].[7] The compounds [(RC5H4)2Ti(SH)2] (R = H, Me) are probably the most accessible of such derivatives. Organotitanium complexes have proven to be versatile for the construction of unusual sulfur ligands.[8,9] For example, the (C5R5)2TiIV moiety has served as a platform for the novel sulfur-based ligands summarized in Scheme 1.[9]

Scheme 1.

Representative dithiatitanacycles.

Herein, we describe a new addition to the library of dithiolatotitanocenes by showing that titanocene stabilizes azadithiolate ligands. We also describe the transfer of the azadithiolate ligand from titanocene to the diiron centers to form [Fe2{(SCH2)2NR}(CO)6].

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

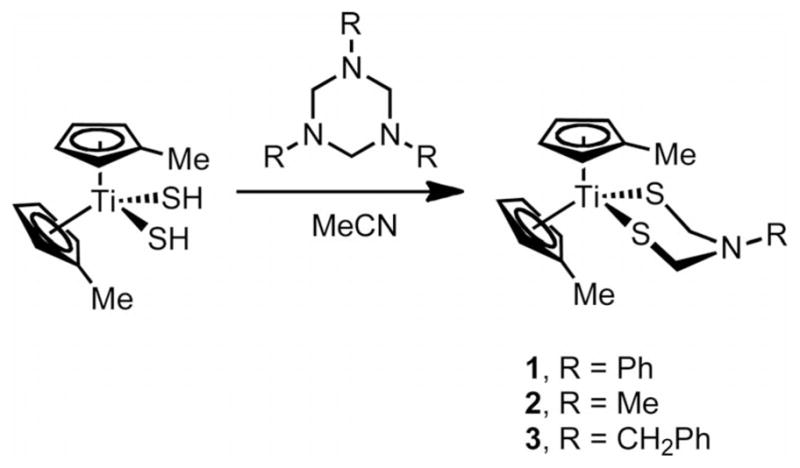

The complexes [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NR}] form upon treatment of [(MeC5H4)2Ti(SH)2] with the cyclic imines (CH2NR)3 (R = Ph, Me, and CH2Ph) in acetonitrile solutions. The reactions require a few hours to overnight at room temperature and are accompanied by striking color changes. [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] (1) was obtained in analytical purity as dark purple–brown crystals in ca. 39 % yield (Scheme 2). The related compound 2 was obtained similarly as a green microcrystals in 70 % yield within 2 h. Compound 3 required almost 10 h at room temperature to yield 48 % of the desired product. The corresponding reactions with [(C5H5)2Ti(SH)2] were found to proceed similarly, but the products were less easily purified.

Scheme 2.

Formation of azadithiolatotitanocenes.

The new azadithiolate complexes are proposed to arise by the initial abstraction of the active SH protons in [(MeC5H4)2Ti(SH)2] by the amine base in the triazine. This proposal is supported by the noticeably faster formation of 2 relative to the formation of 1 and 3; presumably because of the enhanced basicity of (CH2NMe)3. It is also noteworthy that other heterocycles, e.g. (CH2O)3 and (CH2S)3 did not yield the corresponding dithiolatotitanocene complexes upon reaction with [(RC5H4)2Ti(SH)2]. Preliminary attempts to generalize the reaction with other bis(hydrosulf [Ni(dppe)(SH)2] and [Pt(SH)2-(PPh3)2] have proven unsuccessful, possibly because the –SH groups of these compounds are insufficiently acidic.

X-ray Crystallography

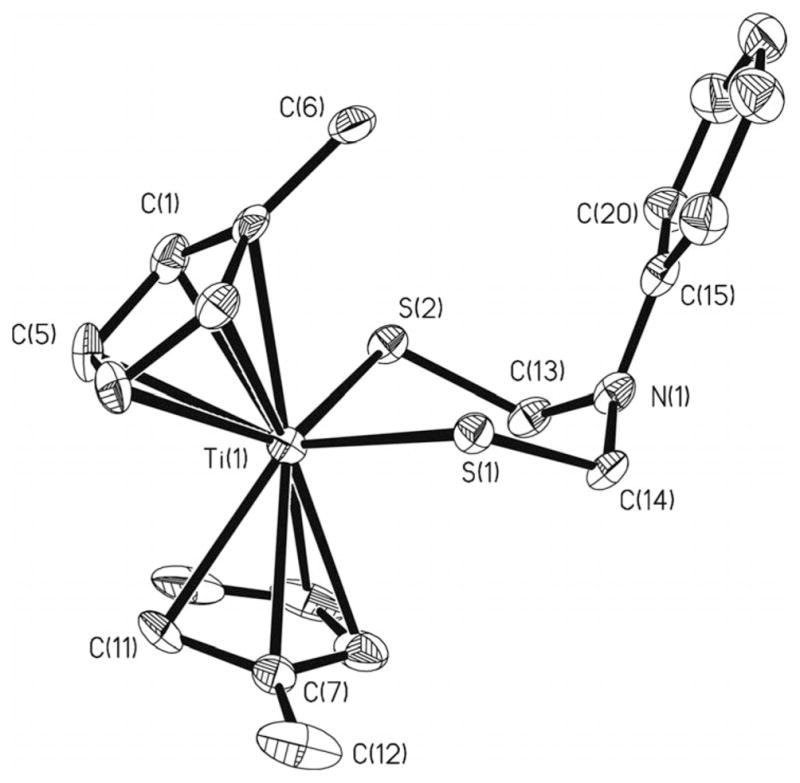

Crystallographic analysis of 1 confirms the expected structure (Figure 1, Table 1). The S1–Ti–S2 angle is 91.15(4) Å and is similar to the relative titanacycles.[9] The Ti–S bond length averages to 2.389(15) Å, and the S–C bond length averages to 1.856(4) Å. The sum of the bond angles around N1 is 353°, which indicates a degree of planarity, as is typical for N-phenyl derivatives of azadithiolates.[10] The phenyl ring is, however, twisted by 27.2° from the plane defined by the CH2–N1–CH2 group.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] (1). Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Ellipsoids depicted at 35 % probability level.

Table 1.

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] for [(MeC5H4)2-Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] (1).

| Bond lengths | Bond angles | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ti(1)–S(1) | 2.4022(15) | S(1)–Ti(1)–S(2) | 91.14(5) |

| Ti(1)–S(2) | 2.3764(16) | C(14)–N(1)–C(15) | 118.8(4) |

| S(1)–C(14) | 1.857(4) | C(14)–N(1)–C(13) | 115.3(4) |

| S(2)–C(13) | 1.855(4) | S(1)–C(14)–N(1) | 115.7(3) |

| C(13)–N(1) | 1.434(5) | N(1)–C(13)–S(2) | 113.0(3) |

| C(14)–N(1) | 1.447(5) | C(14)–S(1)–Ti(1) | 108.16(14) |

| N(1)–C(15) | 1.422(5) | C(13)–S(2)–Ti(1) | 105.18(14) |

| C(13)–N(1)–C(15) | 119.1(4) |

1H NMR Spectroscopy

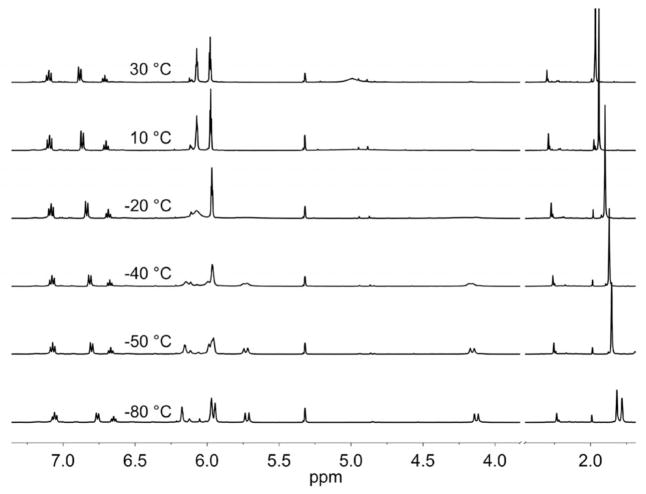

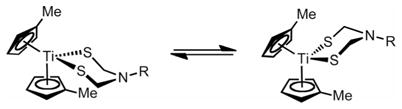

The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 in CD2Cl2 at 20 °C displays broadened signals for CH2 at δ ≈ 5 ppm, consistent with ring inversion as seen for related titanacycles[11] [Equation (1)].

|

(1) |

The CH3C5H4 signals split similarly with Tc ≈ −55 °C. At low temperatures the four MeC5H4 and the two CH2 resonances are well resolved (Figure 2). The average chemical shift of the Me signals is temperature dependent and varies by 0.16 ppm from 30 to −80 °C, whereas the average of the CH2 signals is essentially invariant over this range. The variable-temperature spectrum of [(MeC5H4)2TiCl2] over the same range exhibits no change in δMe. The temperature dependence of the [(CH3C5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] signals in 1 is thus associated with the azadithiolate ring. We suggest that the population of the rotamers shifts subtly as a function of temperature. This equilibrium is possibly related to weak interactions between the axial protons of the CH2 groups and CH3C5H4 substituents.

Figure 2.

500 MHz 1H NMR spectrum of [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2-NPh}] (1) in CD2Cl2 solution recorded at various temperatures between −80 and 30 °C.

For a comparison, variable-temperature 1H NMR measurements on [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2CH2}] (4) were recorded over the range −70 and 30 °C (Figure S1). At −70 °C, signals for the diastereotopic MeC5H4 and CH2 are well resolved.

Electrochemistry

The electrochemical properties of complexes 1–4 were studied in dichloromethane solution. All exhibit reversible reduction events with E1/2 values ranging between −1.78 and −1.88 V vs. ferrocene/ferrocenium (Table S1 and Figure S2).

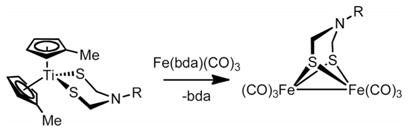

Transfer of Azadithiolate from Ti to Fe

Shaver and co-workers reported that [(C5H5)2Ti-(SCMe3)2] and [(C5H5)Co(CO)2] react to give [{(C5H5)-Co}2(SCMe3)2].[12] We extended Shaver’s method in two ways: using [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] in place of [(C5H5)2Ti(SCMe3)2] and using an Fe(CO)3 source in place of [(C5H5)Co(CO)2]. In this way, we converted [(MeC5H4)2-Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] into [Fe2{(SCH2)2NPh}(CO)6] [Equation (2)]. As the Fe0 source, we used the Fe0 complex of benzylideneacetone, [Fe(bda)(CO)3]. The red diiron product was isolated in 42 % yield after a chromatographic workup. In comparison to the usual routes to diiron azadithiolato complexes, this method proceeds in good yields and avoids the use of [Fe2S2(CO)6].

|

(2) |

In the future, we hope to explore the pathway for this reaction; our preliminary spectroscopic measurements indicate the probable co-formation of [(MeC5H4)4Ti2{(SCH2)2-NPh}] in analogy with previous work.[12]

Conclusions

After many publications and crystal structures, this paper describes the first synthesis and structural characterization of an azadithiolato complex not based on the diiron core. By transferring the azadithiolate cofactor from the titanium center to diiron centers, a new method has been developed that may prove useful to the study of this unusual cofactor and its complexes.

Experimental Section

Materials and Methods

Standard Schlenk techniques were used unless otherwise noted. Solvents used for syntheses were HPLC grade and further purified by using an alumina filtration system (Glass-contour Co., Irvine, CA). NMR solvents were either dried with CaH2 and stored under nitrogen over activated molecular sieves or purchased as ampoules from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. The reagent [(MeC5H4)2Ti(SH)2][13] was prepared as previously described but by using the new route to Na(MeC5H4).[14] 1,3,5-Tri-phenyl-1,3,5-triazine was synthesized by the condensation of aqueous formaldehyde and aniline, and the crude product was purified by recrystallization from CH2Cl2/hexane. 1,3,5-Trimethyl-1,3,5-triazine and 1,3,5-tribenzyl-1,3,5-triazine were obtained from Aldrich and used as received. Solvents were dried and deoxygenated prior to use. Elemental analyses were conducted at the University of Illinois, Microanalytical Laboratory. FAB-MS were collected on a MicroMass 700-VSE mass spectrometer. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury spectrometer, and the chemical shifts were referenced to the residual protons of deuterated solvents.

[(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] (1)

A solution of [(MeC5H4)2Ti-(SH)2] (272 mg, 1 mmol) in MeCN (20 mL) was treated with a solution of (CH2NPh)3 (292 mg, 1 mmol) of in MeCN (10 mL). The initially orange reaction mixture slowly turned dark brown. After stirring the reaction mixture overnight, the product [(MeC5H4)2-Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] had precipitated as dark purple–brown crystals. After filtration of the mixture, this solid was washed repeatedly with hexane. Additional product could be isolated from the filtrate by reducing the solvent volume followed by addition of ether. Yield: 150 mg (39 %). C20H23NS2Ti (389.4): calcd. C 61.71, H 5.91, N 3.60; found C 61.69, H 5.51, N 4.24. FAB-MS: m/z = 391 [M2+]. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ = 7.09 (t, 2 H, Ph), 6.88 (d, 2 H, Ph) 6.70 (t, 1 H, Ph), 6.07 (t, 4 H, C5H4Me), 5.97 (t, 4 H, C5H4Me), 4.98 (br., 4 H, SCH2N), 1.95 (s, 6 H, CH3C5H4) ppm. 1H NMR (CDCl3, −60 °C): δ = 7.07 (t, 2 H, Ph), 6.78 (d, 2 H, Ph) 6.66 (t, 1 H, Ph), 6.16–5.95 (8 H, C5H4Me), 5.71 (d, 2 H, SCH2N), 4.14 (d, 2 H, SCH2N), 1.84 and 1.83 (2 ×s, 6 H, CH3C5H4) ppm.

[(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NMe}] (2)

A solution of [(MeC5H4)2Ti-(SH)2] (100 mg, 0.368 mmol) in MeCN (20 mL) was treated with (CH2NMe)3 (175 mg, 0.740 mmol). The orange reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature, turning dark green over this time. The reaction mixture was evaporated to dryness and extracted into a minimum amount of CH2Cl2. Column chromatography eluting with 1:4 (MeCN:toluene) gave a dark green band. The product 2 was obtained as a dark purple–brown crystalline solid upon evaporation of the solution to dryness. The solid was purified by recrystallization from CH2Cl2 by the addition of hexane. Yield: 42 mg (65 %). C20H23NS2Ti (389.4): calcd. C 54.81, H 6.30, N 4.16; found C 55.06 H 6.42, N 4.28. FAB-MS: m/z = 327.1. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ = 6.05 (br., 4 H, C5H4Me), 5.98 (br., 4 H, C5H4Me), 4.47 (br., 4 H, SCH2N), 2.15 (br., 6 H, CH3C5H4), 1.78 (s, NMe) ppm. 1H NMR (CDCl3, −60 °C): δ = 6.12–5.80 (m, 8 H, C5H4Me), 4.91 (d, 2 H, SCH2N), 3.98 (d, 2 H, SCH2N), 2.36 (s, 3 H, NCH3), 1.78–1.70 (m, 6 H, CH3C5H4) ppm.

[(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NCH2Ph}] (3)

A solution of [(MeC5H4)2-Ti(SH)2] (272 mg, 1.0 mmol) in MeCN (15 mL) was treated with a solution of [CH2N(CH2Ph)]3 (370 mg, 1.0 mmol) in 15 mL of MeCN (15 mL). Even though no color change was observed immediately after the addition, the color of the solution darkened over the course of 30 min. The reddish–brown color of the reaction mixture turned to dark green upon stirring for about 24 h. The solution was concentrated to dryness under vacuum. The resulting green oil was dissolved in dichloromethane (≈5 mL), which was purified on silica gel; a green oil was obtained. The oil was extracted into and crystallized from a pentane solution after storage at −20 °C for 12 h. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ = 7.20 (m, 5 H, Ph), 6.10 (t, 4 H, C5H4Me), 5.98 (t, 4 H, C5H4Me), 4.43 (br., 4 H, SCH2N), 3.63 (s, 2 H, NCH2Ph), 2.30 (s, 6 H, CH3C5H4) ppm. 1H NMR (CDCl3, −60 °C): δ = 7.20 (m, 5 H, Ph), 6.14–5.83 (8 H, C5H4Me), 4.89 (d, 2 H, SCH2N), 4.00 (d, 2 H, SCH2N), 3.57 (s, 2 H, NCH2Ph), 2.27 (s, 6 H, CH3C5H4) ppm.

Reaction of [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2NPh}] (1) and [Fe(bda)(CO)3]

A 100-mL Schlenk flask was charged with 1 (195 mg, 0.5 mmol) and [Fe(bda)(CO)3] (286 mg, 1 mmol). Dry toluene (30 mL) was added to this mixture, the solution was stirred at 90 °C, and the progress of the reaction was monitored by IR spectroscopy. After 26 h, [Fe(bda)(CO)3] had been fully consumed. Over the course of the reaction, the reaction mixture turned reddish–brown, and a dark brown precipitate formed. The reaction mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated under vacuum to a brown paste. The paste was taken up in CH2Cl2/hexane (1:9, 10 mL) and filtered through a pad of silica gel to remove a dark green insoluble material. Evaporation of the filtrate gave 96 mg (42 %) of [Fe2{(SCH2)2-NPh}(CO)6]. The IR spectrum of the resulting compound exhibits CO bands at: ν̃ = 2077 (m), 2039 (s), 2022 (w), 2005 (s), 1983 (m) cm−1, which closely matches previously reported data.[5]

Crystal Structure Determination

Crystals of [(MeC5H4)2Ti{(SCH2)2- NPh}] (1) were grown by vapor diffusion of hexane into a CH2Cl2 solution of 1 (Table 2). The crystal was mounted on a thin glass fibre by using oil (Paratone-N, Exxon) before being transferred to a Siemens Platform/CCD automated diffractometer for data collection. Data processing was performed with the integrated program package SHELXTL. The structure was solved by direct methods and refined by using full-matrix least-squares on F2 with the program SHELXL-93. Hydrogen atoms were fixed in idealized positions with thermal parameters 1.5×those of the attached carbon atoms. The data was corrected for absorption on the basis of Ψ scans. Crystallographic data are summarized in Table S1. Selected bond lengths and angles are reported in Table S2. CCDC-188272 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Table 2.

Crystal and structure refinement data for 1.

| Empirical formula | C20H23NS2Ti |

| Formula weight | 389.41 |

| Crystal color | black prism |

| Crystal size | 0.22 ×0.12 ×0.08 |

| Space group | P21/n |

| a / Å | 10.126(4) |

| b / Å | 7.891(3) |

| c / Å | 22.580(8) |

| α / ° | 90 |

| β / ° | 96.389(8) |

| γ/ ° | 90 |

| V / Å3 | 1793.1(11) |

| Z | 4 |

| Dcalcd. / g cm−3 | 1.4443 |

| μ / mm−1 | 0.711 |

| Temperature / K | 193(2) |

| Absorption correction | ψ scan |

| Tmin, Tmax | 0.7439, 0.9769 |

| No. of measured reflections | 12266 |

| No. of independent reflections | 4308 |

| R1/wR2 [I >2σ(I)] | 0.0580 |

| R1/wR2 (all reflections) | 0.0949 |

| S | 1.04 |

| No. of refined parameters | 14648 |

| No. of restraints | 797 |

| Residual electron density between / e Å−3 | −0.463 and 0.467 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported as part of the ANSER Center, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award Number DE-SC0001059. R. A. is grateful for the Rubicon grant from The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). We thank James M. Camara II for advice and help.

Footnotes

Supporting Information (see footnote on the first page of this article): Experimental details and VT-NMR spectra of compound 4 and electrochemical properties of compounds 1–4 are presented.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejic.201001208.

References

- 1.Tard C, Pickett CJ. Chem Rev. 2009;109:2245. doi: 10.1021/cr800542q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gloaguen F, Rauchfuss TB. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:100. doi: 10.1039/b801796b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton BE, Olsen MT, Rauchfuss TB. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16834. doi: 10.1021/ja8057666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulder DW, Boyd ES, Sarma R, Lange RK, Endrizzi JA, Broderick JB, Peters JW. Nature. 2010;465:248. doi: 10.1038/nature08993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mulder DW, Ortillo DO, Gardenghi DJ, Naumov AV, Ruebush SS, Szilagyi RK, Huynh B, Broderick JB, Peters JW. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6240. doi: 10.1021/bi9000563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rauchfuss TB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:4166. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bethel RD, Singleton ML, Darensbourg MY. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8567–8569. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henery-Logan KR, Abdou-Sabet S. J Org Chem. 1973;38:916. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence JD, Li H, Rauchfuss TB, Bénard M, Rohmer M-M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:1768. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010504)40:9<1768::aid-anie17680>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2001;113:1818. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Rauchfuss TB. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:726. doi: 10.1021/ja016964n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peruzzini M, de los Rios I, Romerosa A. Prog Inorg Chem. 2001;49:169. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephan DW, Nadasdi TT. Coord Chem Rev. 1996;147:147. [Google Scholar]; Steudel R, Hassenberg K, Munchow V, Schumann O, Pickardt J. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2000:921. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giolando DM, Rauchfuss TB, Rheingold AL, Wilson SR. Organometallics. 1987;6:667. [Google Scholar]; Giolando DM, Rauchfuss TB, Clark GR. Inorg Chem. 1987;26:2080. [Google Scholar]; Giolando DM, Rauchfuss TB. Organometallics. 1984;3:487. [Google Scholar]; Steudel R, Schumann O, Buschmann J, Luger P. Angew Chem. 1998;110:515. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980918)37:17<2377::AID-ANIE2377>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:492. [Google Scholar]; Steudel R, Holz B, Pickardt J. Angew Chem. 1989;101:1301. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1989;28:1269. [Google Scholar]; Bergemann K, Kustos M, Krueger P, Steudel R. Angew Chem. 1995;107:1481. [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:1330. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song LC, Ge JH, Zhang XG, Liu Y, Hu QM. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2006:3204. [Google Scholar]; Vijaikanth V, Capon JF, Gloaguen F, Pétillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J. J Organomet Chem. 2007;692:4177. [Google Scholar]; Ott S, Borgström M, Kritikos M, Lomoth R, Bergquist J, Åkermark B, Hammarström L, Sun L. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:4683. doi: 10.1021/ic0303385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Si G, Wang WG, Wang HY, Tung CH, Wu LZ. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:8101. doi: 10.1021/ic800676y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaver A, McCall JM. Organometallics. 1984;3:1823. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaver A, Morris S, Turrin R, Day VW. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:3622. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darkwa J, Giolando DM, Murphy CJ, Rauchfuss TB. Inorg Synth. 1990;27:51. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jana R, Kumar MS, Singh N, Elias AJ. J Organomet Chem. 2008;693:3780. Received: November 16, 2010 Published Online: January 14, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.