Abstract

Objectives

To determine the level of agreement between a ‘conventional’ Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) measurement (using Doppler and mercury sphygmomanometer taken by a research nurse) and a ‘pragmatic’ ABI measure (using an oscillometric device taken by a practice nurse) in primary care. To ascertain the utility of a pragmatic ABI measure for the diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in primary care.

Design

Cross-sectional validation and diagnostic accuracy study. Descriptive analyses were used to investigate the agreement between the two procedures using the Bland and Altman method to determine whether the correlation between ABI readings varied systematically. Diagnostic accuracy was assessed via sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, likelihood ratios, positive and negative predictive values, with ABI readings dichotomised and Receiver Operating Curve analysis using both univariable and multivariable logistic regression.

Setting

Primary care in metropolitan and rural Victoria, Australia between October 2009 and November 2010.

Participants

250 persons with cardiovascular disease (CVD) or at high risk (three or more risk factors) of CVD.

Results

Despite a strong association between the two method's measurements of ABI there was poor agreement with 95% of readings within ±0.4 of the 0.9 ABI cut point. The multivariable C statistic of diagnosis of PAD was 0.89. Other diagnostic measures were sensitivity 62%, specificity 92%, positive predictive value 67%, negative predictive value 90%, accuracy 85%, positive likelihood ratio 7.3 and the negative likelihood ratio 0.42.

Conclusions

Oscillometric ABI measures by primary care nurses on a population with a 22% prevalence of PAD lacked sufficient agreement with conventional measures to be recommended for routine diagnosis of PAD. This pragmatic method may however be used as a screening tool high-risk and overt CVD patients in primary care as it can reliably exclude the condition.

Keywords: Primary Care, Vascular Medicine, Public Health

Article summary.

Article focus

To determine the agreement between AnkleBrachial Index (ABI) measured by Doppler and mercury sphygmomanometer by research nurse and that of general practice nurse measurement with an oscillometric device.

To ascertain the utility of oscillometric devices for the diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Key messages

Oscillometric ABI measures by primary care nurses on a population with a 22% prevalence of PAD lacked sufficient agreement with conventional measures to be recommended for routine diagnosis of PAD.

This pragmatic method may, however, be used as a screening tool in high-risk primary care patients as it can reliably exclude the condition.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This validation study was conducted in primary care where undiagnosed PAD is likely to be found.

The intervention was kept as simple as possible by using practice nurses to do single measures on a device they already were familiar with allowing easy implementation.

This approach meant however that practice nurses did not receive extensive training and their performance may have been improved by said.

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) affects an estimated 27 million individuals in Europe and North America with 413 000 related hospital discharges per annum.1 2 These figures are likely to underestimate the true impact of PAD as those with the condition disproportionally suffer from other manifestations of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and are therefore likely to appear in coronary artery disease or stroke statistics. As a consequence, there has been a call for better detection and management of the condition.1

One of the simplest and most useful parameters to objectively assess lower extremity arterial perfusion, and thus diagnose PAD, is the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI). This is the lower of the left and right ABI where each ABI is the ratio of the lower limb systolic blood pressure compared to the higher systolic brachial blood pressure recording. The ABI can be used to screen for haemodynamic significant PAD and helps to define its severity. Patients with objectively documented PAD have a fourfold to sixfold increase in cardiovascular mortality over healthy age-matched individuals.3 PAD is a stronger risk marker for myocardial and stroke morbidity and mortality than those who have already had such an incident event.4 5 However, only 50% of people with PAD are symptomatic which is a significant issue in the detection of PAD.2

Between 2007 and 2009, 19 500 oscillometric devices were distributed by the High Blood Pressure Research Council of Australia to physicians, mostly general practitioners (GPs). We had previously demonstrated that these devices were likely to improve blood pressure management in primary care.6 The current study, Ankle Brachial Index Determination by oscillometric method IN General practice (ABIDING), sought to expand the utility afforded by these machines in primary care. Previous work done in those attending a specialist vascular laboratory in the US demonstrated that patients could have their ABI reliably ascertained by such devices compared to the conventional use of a Doppler ultrasound and mercury sphygmomanometer.7 It was therefore opportune to investigate if such measures were pragmatic in primary care where the greatest opportunity exists to identify those with undiagnosed PAD. Such persons are at very high risk for subsequent adverse cardiovascular events that can be ameliorated through management of modifiable risk factors.

The primary aim of ABIDING was to establish if there was agreement between a pragmatic ABI (measured by a practice nurse using an oscillometric blood pressure device) and a conventional ABI (measured by a research nurse using mercury sphygmomanometer and Doppler devices). A secondary aim was to ascertain diagnostic accuracy of the pragmatic approach for ascertaining PAD.

Methods

GPs and participants were recruited through the REACH Registry Victorian database. The international REACH Registry was a prospective, observational registry designed to provide long-term follow-up (36 months) of patients at high risk of atherothrombotic events. Globally 67 888 patients were involved in the REACH registry of whom 2782 were recruited from 281 general practitioners around Australia.8 9 Practices were eligible for ABIDING if they had previously enrolled participants in the REACH registry and had a practice nurse willing to participate or were willing to appoint a locum tenens nurse. Eligibility criteria for REACH are published elsewhere but can be summarised as at entry (March–June 2004) aged 45+ years, had known CVD or at least three atherosclerosis risk factors, and were physically able to attend their usual general practice.8

Participant recruitment

All Melbourne (metropolitan) and Warrnambool (rural) Victorian study participants who had consented to follow-up, who had been identified by their GPs as alive and for whom we had a current address, were contacted by mail. If no reply was received from the participant within 4 weeks, a second letter was sent and then a telephone call made. Participants were seen in their usual GP's clinic between October 2009 and November 2010.

Research and practice nurses

Three experienced research nurses conducted the reference standard tests. They received standardised training from a senior research nurse who was one of the operators. Practice nurses were given training in situ by the research nurse and were observed by them. Because they worked contemporaneously the research nurse was not blinded to the practice nurses results.

‘Conventional’ and ‘pragmatic’ ABI estimation

All participants were rested supine for 5 min before measurement. Doppler blood pressure measurements (by research nurse) and automated oscillometric blood pressure measurements (by practice nurse) were performed using cuffs that had bladders >80% of the diameter of the arms and ankles measured.

Conventional measures involved Doppler blood pressure measurements in the lower limb made with a Nicolet Vascular Doppler with a 5 MHz probe. The cuff was inflated to 30 mm Hg above systolic blood pressure and deflated slowly until a flow signal was detected over the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial arteries. Brachial artery systolic pressure was determined similarly but utilising a stethoscope rather than a Doppler. The ABI for each lower extremity was calculated as the pedal pressure divided by the higher of the two brachial pressures. PAD is defined as an ABI <0.9 in either lower limb.10 The mercury sphygmomanometer was calibrated by a certified laboratory.

Research nurses were trained in the measurement of ABI and were certified prior to the start of the study. Practice nurses were simply observed and technique corrected if required. Oscillometric measurements were made by the practice nurse on all limbs using a standard automated blood pressure cuff system (OMRON HEM-907, Omron Healthcare Singapore Pte Ltd, Singapore). This device is a validated blood pressure measurement device.11 12 Oscillometric devices were new and therefore had factory calibration. Participants also completed the Edinburgh Claudication questionnaire (ECQ).13

Statistical methods

Descriptive analyses were used to investigate the agreement between the two procedures using the Bland and Altman method to determine whether measurements could be used interchangeably and if the correlation between ABI readings varied systematically.14 Although the variability in the differences appeared to be proportional to the mean, applying a log transformation to the data did not substantially alter agreement and so raw scores are presented. Correlations between the paired readings were also calculated. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and accuracy with exact 95% CI are reported, where ABI readings taken under both conditions were dichotomised at 0.9 (reference standard). The diagnostic accuracy was evaluated using Receiver Operating Curve analysis and quantified as the area under the curve (AUC or C statistic), as determined using both univariable and multivariable logistic regression. In the multivariable model we adjusted for age, body mass index (BMI), gender and smoking status (never, former and current). The calibration of this model was validated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic.15 We examined likelihood ratios, the ratio of the expected test results in participants with PAD to those participants without. All results are reported with 95% CI. All analyses were conducted using Stata V.12.0.

Power calculations

Assuming a type 1 error of 5% (α=0.05) a total sample of 250 participants provided 80% power to detect systematic bias between the readings taken by the research and practice nurses if the mean difference was 0.0255.14 Eight participants were excluded as 6 pragmatic and 2 conventional ABI readings were absent. In all other cases each patient had at least one conventional and pragmatic ABI reading (for the same leg). For a sample of 242 the difference that we could detect was 0.0257. We expected strong correlations between ABI readings taken using the different methods. Both calculations assumed a correlation between readings of 0.61 and SDs as reported in Benchimol et al.16

Results

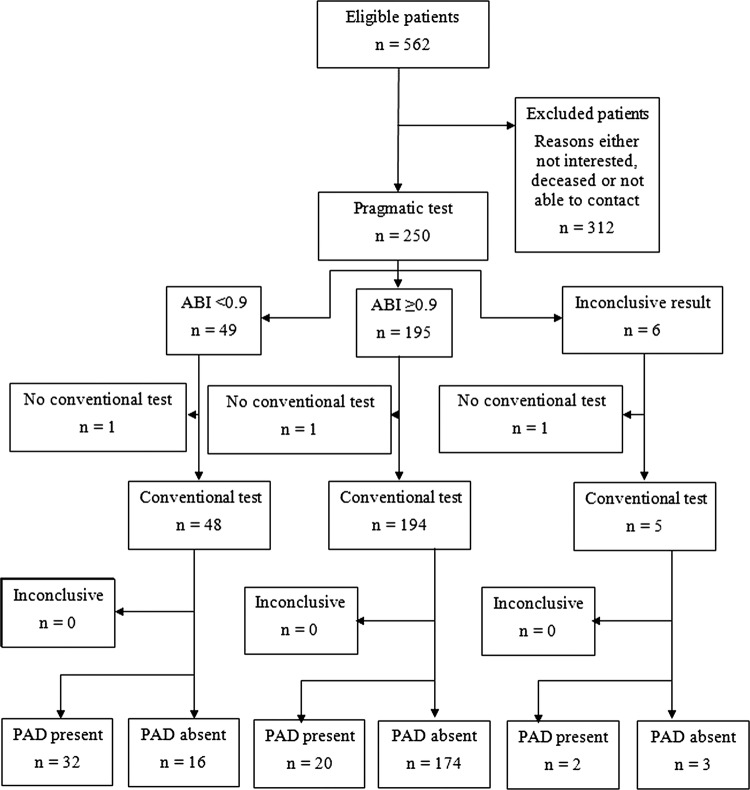

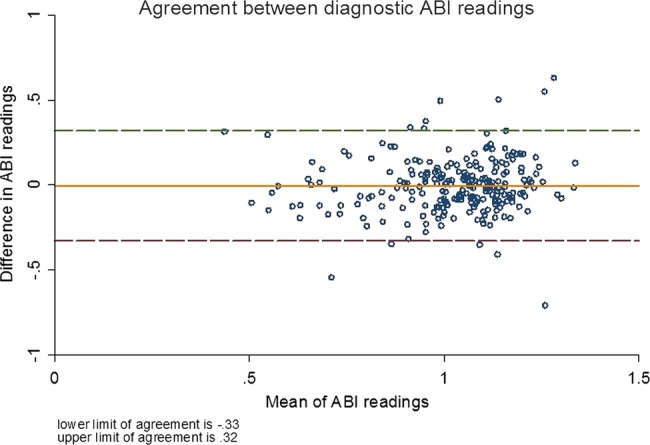

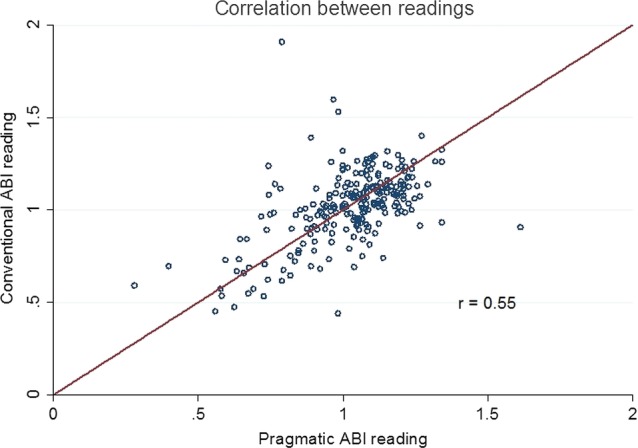

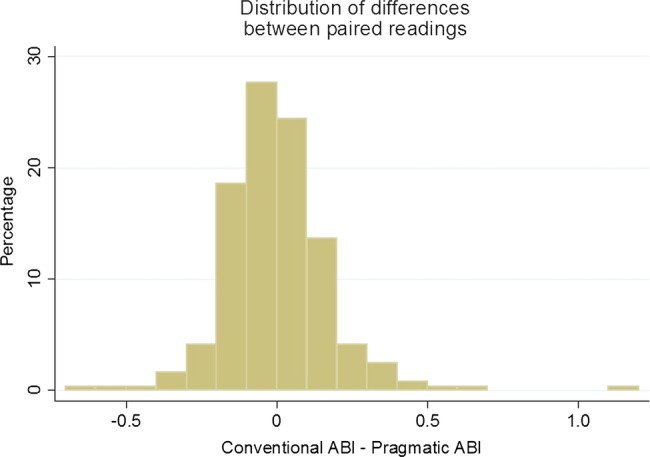

The flow chart of the study is shown in figure 1. The characteristics of the ABIDING population are shown in table 1. There was no difference between those excluded and included in the analysis for any trait that we measured. We also compared in table 1 those diagnosed with PAD versus not using conventional ABI. Those with PAD were older (p=0.003) and more likely to be women (p=0.003). Figure 2 shows that there was poor agreement between pragmatic and conventional determination of ABI with 95% of readings within ±0.4. Figure 3 shows correlation between conventional and pragmatic ABI measurements, indicating a strong association between the two measurements, despite the poor agreement. The distribution of differences between the ABI measures is shown in figure 4. These differences were regressed on all possible confounders measured in our study, in both univariable and multivariable models. There were no significant associations, suggesting that the differences were completely random.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of a diagnostic accuracy in ABIDING as per STARD standard.25

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants by conventional peripheral arterial disease status expressed as a mean (SD) or N (%) as appropriate

| Variable | Included | Conventional ABI≥0.9 | Conventional ABI<0.9 | p for difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 242 | 192 | 52 | |

| Age in years | 71.2 (7.4) | 70.4 (7.0) | 73.9 (8.3) | 0.003 |

| Male sex (%) | 167 (69.0) | 140 (73.7) | 27 (52.0) | 0.003 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 141.5 (18.9) | 140.6 (17.8) | 144.5 (22.4) | 0.35 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 76.7 (9.9) | 77.0 (9.8) | 75.5 (10.4) | 0.55 |

| BMI (kg/h2) | 27.5 (4.4) | 27.5 (4.4) | 27.2 (4.4) | 0.63 |

| Waist | 99.9 (10.8) | 100.1 (10.4) | 99.2 (12.3) | 0.60 |

| Smoking status | 0.31 | |||

| Never | 98 (40.7) | 81 (42.9) | 17 (32.7) | |

| Former | 131 (54.4) | 100 (52.9) | 31 (59.6) | |

| Current | 12 (5.0) | 8 (4.2) | 4 (7.7) |

ABI, Ankle-Brachial Index; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Figure 2.

Agreement between pragmatic and conventional determination of Ankle-Brachial Index.

Figure 3.

Correlation between pragmatic and conventional determination of Ankle-Brachial Index.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the difference between the conventional and the pragmatic Ankle-Brachial Index readings.

A 2×2 table of dichotomised conventional and pragmatic measurements is shown (table 2). We examined the two groups comprising the 36 participants where the PAD classification differed. There were no differences in any measured trait between those groups (data not shown). The respective pragmatic method diagnostic performance, assuming the conventional method as gold standard, was sensitivity 62% (95% CI 47% to 75%), specificity 92% (87% to 95%), positive predictive value 67% (52% to 80%), negative predictive value 90% (85% to 94%) and accuracy 85% (80% to 89%). The likelihood ratio for a positive result (LR+) was 7.3 (95% CI 4.4 to 12.0) and likelihood ratio test for a negative result (LR−) 0.42 (0.30 to 0.59). Test performance for the asymptomatic subgroup on ECQ (N=183 PAD 18%) sensitivity 54% (95% CI 37% to 69%) specificity 93% (89% to 97%) and symptomatic (N=18 PAD 61%) sensitivity 9% (2% to 41%) specificity 57% (18% to 90%). Area under the Receiver Operator Characteristic curves (AUC/C statistic) of pragmatic ABI against the conventional ABI <0.9 and thus PAD was 0.87 (95% CI 0.82 to 0.93). The AUC from multivariable analysis (adjusting for age, gender, BMI and smoking status) for all analyses were almost identical 89% (95% CI 84% to 93%).

Table 2.

2×2 Table of conventional and pragmatic ABI determinations

| PAD positive (conventional ABI<0.9) | PAD negative (conventional ABI≥0.9) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test positive (pragmatic ABI <0.9) | 32 | 16 | 48 |

| Test negative (pragmatic ABI ≥0.9) | 20 | 174 | 194 |

| Total | 52 | 190 | 242 |

ABI, Ankle-Brachial Index; PAD, peripheral arterial disease.

Based on the differences in table 1 for those with PAD versus not we conducted a post hoc subgroup analyses on pragmatic versus conventional ABI readings by gender, age (dichotomised as young or old) and all pairwise combinations. The agreement between reading and diagnostic criteria did not improve for any subgroup (data not shown). We also investigated (using multivariable logistic regression) whether there was any evidence that disagreements were systematic. There was no difference in disagreements apart from current smokers were more likely to produce readings that disagreed compared to non-smokers (p=0.025). A subgroup analysis with current smokers removed did not alter the diagnostic criteria of the tests. As could be expected in non-invasive testing there were no reported adverse events.

Sensitivity analyses for excluding upper ABI cut point of 1.4 (concern regarding possible arterial incompressibility) did not affect the outcomes, and the range 0.85–0.95 gave 0.85 sensitivity 54% and specificity 95%, and 0.95 sensitivity 71% and specificity 86%.

Discussion

ABIDING demonstrated that use of oscillometric devices by general practice nurses to determine ABI and therefore the presence of PAD had high specificity (92%) and negative predictive value (90%), good accuracy (84%) but modest sensitivity (62%) and positive predictive value (67%). The modest sensitivity and the LR+ 7.3 indicate that this test has little value for confirming the presence of PAD. On the contrary high specificity and negative predictive value suggests that the test has some value in ruling out the disease (ie, when the test is negative). Looking at the symptomatic individuals as determined by ECQ showed that, though the numbers were small, the pragmatic measure had a poor performance as a diagnostic test in this high-prevalence (61%) subgroup. Changing the cut point to improve sensitivity or specificity simply compromised the other measure and therefore did not improve test performance.

These findings were in contrast to the experience in a specialist centre where their test performance (both limbs in comparison to ABIDING lower of the two measures) was sensitivity left/right leg 88/73% (62%), specificity 85/95% (92%), positive predictive value 65/88% (69%), negative predictive value 96/88% (90%), LR+ left/right leg 5.9/14.6 (7.9) and LR− 0.14/0.28 (0.4).4 A good diagnostic test has a LR+ >10 and LR− <0.1.17 This difference in performance to some extent may be accounted for by patient selection but is more likely due to operator expertise. In the specialist centre, the mean age was 10 years younger and 53% were women compared to only 22% in ABIDING. The respective prevalence of PAD was 32% and 22%. In other studies reporting being conducted in primary care Mehlsen et al18 enrolled 1258 consecutive general practice patients for an oscillometric determination of ABI, with those with an ABI <0.9 referred for a Doppler measure in a vascular unit. Hence all ‘negatives’ including false negatives did not have a gold standard measure and therefore this was not a true measure of test performance in primary care. Nicholai et al19 and Aboyens20 had similar limitations. Verberk et al21 conducted a systematic review of automated oscillometric devices including a subgroup analysis on devices developed for arm blood pressure (BP) measurement. Only 1 of the 18 studies identified was conducted in primary care and that with an ABIgram and not a simple BP arm device.22 Although the investigators demonstrated its reliability, the use of this special piece of equipment would seem to effect is acceptability as is the current situation. ABI is a valid and reliable clinical measure although an indirect one. The true gold standard would be an intravascular perfusion study. Both methods have been compared to the true gold standard in 85 patients with claudication undergoing angiography.23 The oscillometric method showed 97% sensitivity, 89% specificity, 98% positive predictive value and 86% negative predictive value. The Doppler method showed 95% sensitivity, 56% specificity, 91% positive predictive value and 68% negative predictive value. This study suggests that the oscillometric method had greater diagnostic accuracy but the test was performed by physicians not specifically trained to use the Doppler probe. This said ABI is a practical tool and is superior to clinical examination for identifying PAD.20 However, screening whole populations is not always practical. ABI ascertainment of PAD is most effective by identifying high-risk patients as we have done in ABIDING. By including high-risk and overt CVD patients we were confident that we should get a distribution of ABI scores that included PAD diagnostic scores and the outcome of the study supports this (22% had PAD by the conventional method).

If our method had been reliable it would have been readily implementable as Australian GPs have ready access to oscillometric sphygmomanometers. More than 19 500 devices were distributed on behalf of the High Blood Pressure Research Council of Australia, mostly to GPs, over the years 2007–2009. Practice nurses were chosen rather than GPs as this approach is also more likely to be implementable. A survey by Mohler et al24 of primary care clinicians showed that most (88%) thought ABI to be feasible in that setting.

Study limitations

The intervention was kept as simple as possible by using practice nurses to do single measures on a device they were familiar with but did not receive extensive further training on. While this means that this is simple to introduce into clinical practice the practice nurse performance may have been improved by more intense training and repeated limb measurements.

Conclusion

Oscillometric ABI measures by primary care nurses on a population with a 22% prevalence of PAD lacked sufficient agreement with conventional measures to be recommended for routine diagnosis of PAD. This pragmatic method may however be used as a screening tool in high-risk primary care patients as it can reliably exclude the condition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of practice nurses, Dr Nyi Nyi Tun who assisted with the literature review, and research nurses Christine Mulvaney, Sue Loftus and Anne Bruce.

Footnotes

Contributor: MRN conceived and designed the study. MRN, TMW, CMR and LS were members of the management committee. SQ was the study statistician. FH was general practitioner liaison. All had input into the writing of the manuscript. MRN is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: NHMRC.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study had ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Tasmania) Network (H0010410) and Monash University Standing Committee on Ethics in Research involving Humans (2009000860), and was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trails Registry (ACTRN12609000744257). It was funded by the RACGP Research Foundation (Cardiovascular Research Grant) and the National Health and Medical Research Council (Project grant 544935), and was supported by the Primary Healthcare Research, Evaluation and Development scheme. Oscillometric devices were loaned by the High Blood Pressure Research Council of Australia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Belch JJF, Topol EJ, Agnelli G, et al. Critical issues in peripheral arterial disease detection and management: a call to action. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:884–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golomb BA, Dang TT, Criqui MH. Peripheral arterial disease: morbidity and mortality implications. Circulation 2006;114:688–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDaniel M, Cronenwett J. Basic data related to the natural history of intermittent claudication. Ann Vasc Surg 1989;3:273–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PWF, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2007;297:1197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenna M, Wolfson S, Kuller L. The ratio of ankle and arm arterial pressure as an independent predictor of mortality. Atherosclerosis 1991;87:119–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson MR, Quinn S, Bowers-Ingram L, et al. Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of Oscillometric versus Manual Sphygmomanometer for Blood Pressure Management in Primary Care (CRAB). Am J Hypertens 2009;22:598–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckman JA, Higgins CO, Gerhard-Herman M. Automated oscillometric determination of the ankle-brachial index provides accuracy necessary for office practice. Hypertension 2006;47:35–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis 10.1001/jama.295.2.180. JAMA 2006;295:180–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid CM, Nelson M, Chew D, et al. Australians @ Risk: management of cardiovascular risk factors in the REACH registry. Heart Lung Circ 2008;17:114–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doobay AV, Anand SS. Sensitivity and specificity of the ankle–brachial index to predict future cardiovascular outcomes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005;25:1463–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assaad MA, Topouchian JA, Darne BM, et al. Validation of the Omron HEM-907 device for blood pressure measurement. Devices Technol 2002;7:237–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White WB, Anwar YA. Evaluation of the overall efficacy of the Omron office digital blood pressure HEM-907 monitor in adults. Devices Technol 2001;6:107–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leng GC, Fowkes F. The Edinburgh claudication questionnaire: an improved version of the WHO/ROSE questionnaire for use in epidemiological surveys. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:1101–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd edn New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benchimol A, Bernard V, Pillois X, et al. Validation of a new method of detecting peripheral artery disease by determination of ankle-brachial index using an automatic blood pressure device. Angiology 2004;55:127–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Šimundic´ A-M. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. http://www.ifcc.org/ifccfiles/docs/190404200805.pdf (accessed 19 October 2012). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Mehlsen J, Wiinberg N, Bruce C. Oscillometric blood pressure measurement: a simple method in screening for peripheral arterial disease. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2008;28:426–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolai SPA, Kruidenier LM, Rouwet EV, et al. Ankle Brachial Index in primary care: are we doing it right? Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:422–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aboyans V, Lacroix P, Doucet S, et al. Diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease in general practice: can the Ankle–Brachial Ibe measured either by pulse palpation or an automatic blood pressure device? Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:1001–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verberk WJ, Kollias A, Stergiou GS. Automated oscillometric determination of the Ankle-Brachial Index: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens Res 2012;1:1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raines JK, Farrar J, Noicely K, et al. Ankle/Brachial Index in the primary care setting. Vasc Endovasc Surg 2004;38:131–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vega J, Romaní S, Garcipérez FJ, et al. Peripheral arterial disease: efficacy of the oscillometric method. Rev Esp Cardiol 2011;64:619–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohler ER, 3rd, Treat-Jacobson D, Reilly MP, et al. Utility and barriers to performance of the Ankle-Brachial Index in primary care practice. Vasc Med 2004;9:253–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. The STARD Statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Clin Chem 2003;49:7–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.