Abstract

In mammals, neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis are germinal processes that occur in the adult brain throughout life. The subventricular (SVZ) and subgranular (SGZ) zones are the main neurogenic regions in adult brain. Therein, it resides a subpopulation of astrocytes that act as neural stem cells. Increasing evidence indicates that pro-inflammatory and other immunological mediators are important regulators of neural precursors into the SVZ and the SGZ. There are a number of inflammatory cytokines that regulate the function of neural stem cells. Some of the most studied include: interleukin-1, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, insulin-like growth factor-1, growth-regulated oncogene-alpha, leukemia inhibitory factor, cardiotrophin-1, ciliary neurotrophic factor, interferon-gamma, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha. This plethora of immunological mediators can control the migration, proliferation, quiescence, cell-fate choices and survival of neural stem cells and their progeny. Thus, systemic or local inflammatory processes represent important regulators of germinal niches in the adult brain. In this review, we summarized the current evidence regarding the effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines involved in the regulation of adult neural stem cells under in vitro and in vivo conditions. Additionally, we described the role of proinflammatory cytokines in neurodegenerative diseases and some therapeutical approaches for the immunomodulation of neural progenitor cells.

Keywords: Interleukin, neural stem cells, subventricular zone, cytokine, inflammation, microglia

Introduction

Within the adult brain, there are tissue-specific multipotent cells (neural stem cells) that generate neurons and oligodendrocytes, which help in cell maintenance of the central nervous system (CNS). Probably in all adult vertebrate species, new neurons are produced and recruited into specific brain circuits: the olfactory bulb and the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus (Galileo et al., 1990; Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2001; Temple, 2001; Gage, 2002; Sanai et al., 2004). On the other hand, stem-cell-derived oligodendrocytes are incorporated into the white matter of corpus callosum, fimbria and striatum (Menn et al., 2006; Gonzalez-Perez and Alvarez-Buylla, 2011). Besides the homeostatic role of NSCs in the brain, some authors have suggested that neural progenitors can be useful for the design of stem-cell-based therapies against several neurodegenerative disorders (Gonzalez-Castaneda et al., 2011; Kabatas et al., 2011; Kasahara et al., 2011; Mitrecic et al., 2011; Rivera et al., 2011).

To date, it is well- accepted that neurogenesis occurs in discrete regions of the CNS: the subventricular zone (SVZ) and the subgranular zone (SGZ). The source of new neurons in the postnatal brain is neural stem cells (NSCs) or neural precursor cells (NPCs). NSCs are multipotent and self-renewing progenitors that are regulated by a number of proteins or chemical mediators, such as: platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF or FGF-2), Notch, epidermal growth factor (EGF), Sonic hedgehog and gp130 and others (Craig et al., 1996; Kuhn et al., 1997; Lai et al., 2003; Machold et al., 2003; Cooper and Isacson, 2004; Jackson et al., 2006; Aguirre et al., 2007; Galvao et al., 2008; Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2009; Gonzalez-Perez and Quinones-Hinojosa, 2010; Leong and Turnley, 2011; Matsumoto et al., 2011; Galvez-Contreras et al., 2012).

Increasing evidence indicates that inflammatory cells and immunological cytokines can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and modulate NSCs and NPCs population. The BBB has a selective permeability that restricts the entrance of molecules and cells into the brain parenchyma. Under physiological conditions, only a few immune cells (T lymphocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells) can penetrate BBB and infiltrate cerebral tissue (Hickey, 1999; Bonecchi et al., 2009; Whitney et al., 2009). Notably, brain tissue does not intensely reject cell transplants. Hence, these observations supported the notion that the brain was an immunologically privileged organ. To date, accumulating evidence strongly challenges this assumption (For review see (Martino et al., 2011)). In fact, neuroinflammation triggers a significant infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes into the cerebral parenchyma. These inflammatory cells can activate astrocytes and microglia, which promote the release a number of anti- and pro-inflammatory substances, neurotransmitters, chemokines, reactive oxygen species and up-regulated surface receptors, such as cytokine receptors and toll-like receptors (TLR) (Cordiglieri and Farina, 2010; Tian and Rauvala, 2010; Northrop and Yamamoto, 2011). This interaction between the immune system and the brain can affect a number of cerebral functions, such as: neural remodeling, synaptic plasticity, neurotransmitter releasing, stress-associated response, cognitive and metal disease progression, and others (Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2001; Jauregui-Huerta et al., 2010; Leonard, 2010; Muller and Schwarz, 2010; Ramos-Remus and Duran-Barragan, 2010; Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2011). Interestingly, a high immunological surveillance has been associated with a reduction in the regenerative capacity of cerebral tissue (Bonfanti, 2011). Evidence indicates that animals with a primitive immune system (such as newt, urodele or fish) are more efficient to regenerate their body organs, including neural tissue, than some amphibians or mammals (Tassava and Olsen, 1982; Sicard, 1983; Tournefier et al., 1998; Fahmy and Sicard, 2002). During embryonic stages, scar-free repair can also be observed in mammals, but this capability reduces progressively and coincides with the ontogenetic development of immune system (Harty et al., 2003). After that period, inflammation generates a restrictive healing process that poorly supports regeneration in adults (Mescher and Neff, 2006; Costa et al., 2011). Therefore, some authors propose that the less inflammatory response the higher regenerative capacity (Mescher and Neff, 2006; Bonfanti, 2011). Inflammatory cytokines also produce a positive feedback loop that might result in both detrimental and positive consequences to neurogenesis (Ekdahl et al., 2003; Monje et al., 2003; Das and Basu, 2008; Miller et al., 2008; Whitney et al., 2009; McPherson et al., 2011).

In this review, we describe the cellular composition and citoarchitecture of the subventricular zone and the subgranular zone (the main neurogenic niches in the adult brain). We also discuss the latest reports indicating that several immunological molecules can control the function of NSCs and/or NPCs in the adult brain. This evidence indicates that immune system and inflammatory processes modify the homeostasis of neurogenic niches in the adult brain.

Subventricular zone (SVZ)

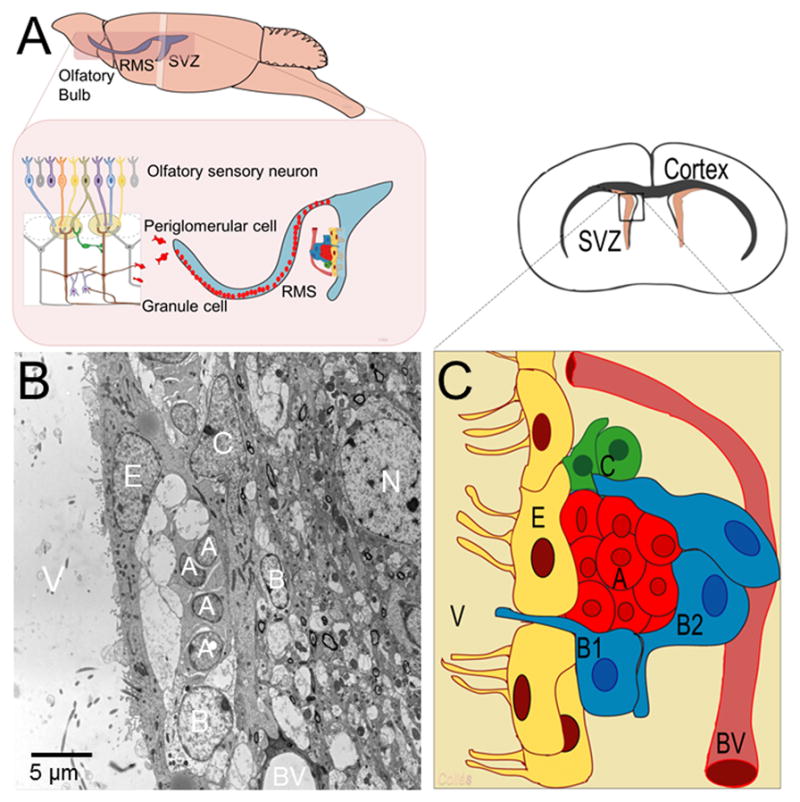

NSCs have been isolated from the SVZ, a cellular niche lining of the lateral ventricles of the adult brain (Figure 1). Interestingly, SVZ NSCs are a subtype of glial cells with structural and molecular characteristics of astrocytes. Mitotic division of astrocyte-like NSCs (type-B1 cells) gives rise to actively proliferating transit amplifying progenitors (type-C cells). Type-C cells, in turn, generate neuroblasts (type-A cells) that migrate toward the olfactory bulb via the rostral migratory stream (RMS) and become interneurons functionally integrated into local networks (Figure 1) (Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1993, 1994; Kriegstein and Alvarez-Buylla, 2009). In addition, SVZ NSCs also generate oligodendrocyte precursors that keep maintaining the oligodendrocyte population of the neighboring corpus callosum, striatum and fimbria fornix (Menn et al., 2006; Gonzalez-Perez et al., 2009).

Figure 1. The adult subventricular zone (SVZ).

A) Schematic drawing that represents the sagittal view of the adult SVZ and rostral migratory stream (RMS). B) Transmission electron microscope image of the adult SVZ showing the typical cellular composition of this neurogenic niche. C) A schematic drawing depicts the organization of SVZ neural progenitors. Type-B1 cells, the putative neural stem cells (shown in blue), generate transit amplifying progenitors or type-C cells (in green), which in turn give rise to type-A cells (shown in red). Type-B2 astrocytes (also in blue) enfold migrating neuroblast. Note that the SVZ niche is in close contact to blood vessels (BV) and the ependymal cell layer (E). V: ventricle; N: neuron

Type-B cells extend a petite apical process that contacts the ventricle and a long basal process ending on blood vessels (Figure 1) (Mirzadeh et al., 2008; Shen et al., 2008). These cytoplasmic contacts are important because extracellular matrix or soluble factors secreted by blood vessels seem to play a significant role in regulating adult neurogenesis (Sawamoto et al., 2006; Shen et al., 2008; Tavazoie et al., 2008; Nakagomi et al., 2009). Stromal-derived factor 1, produced by endothelial cells, and the CXC chemokine receptor 4 expressed by SVZ cells have been involved in this intercellular communication (Kokovay et al., 2010). The role of the SVZ-derived interneurons remains unclear but they seem to regulate the olfaction process (So et al., 2008). Interestingly, neuroinflammation induces functional alteration of adult NSCs that contribute to olfactory dysfunction (Tepavcevic et al., 2011).

Subgranular zone (SGZ)

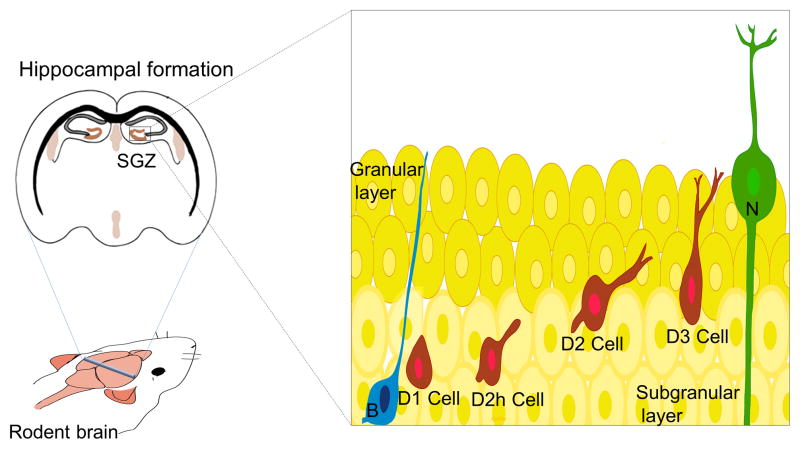

The proliferative region that contains neuronal progenitors in the dentate gyrus is the SGZ within the hippocampus (Figure 2). SGZ progenitors display multipotential characteristic in vitro, but so far, no multipotential properties have been demonstrated in vivo. Consequently, some authors identified type-1 precursors as neuronal progenitors instead of NSCs (Ming and Song, 2011). SGZ precursor cells give rise to neurons that migrate locally into the granular region of the dentate gyrus (Figure 2). The primary progenitors of the SGZ are proliferating radial (also known as type-1 cells) and non-radial astrocytes that divide asymmetrically and originate intermediate progenitors (type-2 cells), also known as type-D cells (Seri et al., 2001). Type-2 progenitors undergo four stages of maturation (D1, D2, D2h and D3) and migrate into the inner granule cell layer and differentiate into dentate granule neurons (Seri et al., 2001; Seri et al., 2004). Newborn granule neurons project axons to the CA3 region and extend dendrites toward the molecular layer (Zhao et al., 2008). Newly generated neurons exhibit hyperexcitability and enhanced synaptic plasticity during developmental stages (Mongiat and Schinder, 2011; Piatti et al., 2011). Yet, after cell maturation, SGZ-derived neurons exhibit similar electrophysiological properties as constitutive mature neurons (Piatti et al., 2011). Newborn granule neurons seem to be important in spatial pattern discrimination, trace conditioning, contextual fear conditioning, clearance of hippocampal memory traces, spatial-navigation learning and long-term spatial memory retention, reorganization of memory to extrahippocampal substrates and depressive behavior (Deng et al., 2010; Aimone et al., 2011; Pechnick et al., 2012).

Figure 2. The adult subgranular zone (SGZ).

Schematic drawing that represents the cytoarchitecture of the SGZ. The primary progenitors (in blue), also known as type-1 cells or type-B cells, give rise to type-2 cells (in red), also known as type-D cells. Intermediate progenitors migrate locally and undergo different maturation stages (D2h, D2, D3 cells) to finally differentiate into granular neurons (N).

Immunomodulation of NSCs

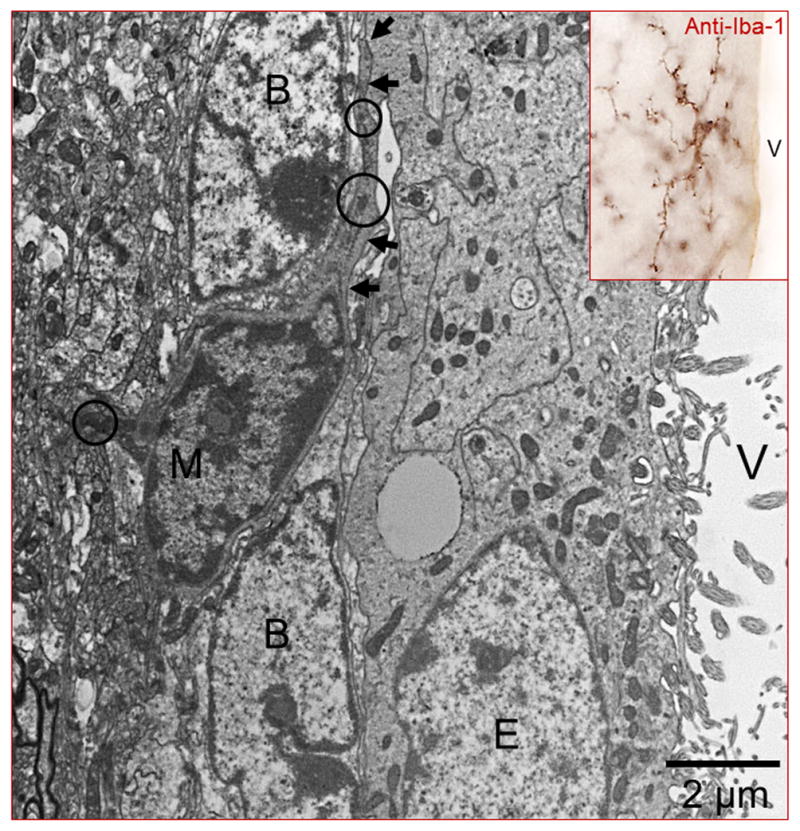

There are a number of trophic factors or molecules that regulate adult NSCs in vivo and in vitro. A classical point of view indicated that most of main mediators of NSCs did not correspond to immune-system-derived molecules. However, growing evidence indicates that immunological molecules can target neurogenic niches and control cell proliferation, survival, differentiation and migration. Cytokines are immunological polypeptides involved in cellular communication, which are abundantly produced by macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, endothelium, dendritic cells and epithelial cells (Miller et al., 2008; Bonecchi et al., 2009). In the central nervous system, microglia is the main immune effector cell in the brain and source of a number of cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Schwamborn et al., 2003; Widera et al., 2004; Whitney et al., 2009), interleukin-4 (IL-4) (von Zahn et al., 1997; Butovsky et al., 2006), interferon gamma (IFN-γ) (Ben-Hur et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2004; Song et al., 2005; Johansson et al., 2008), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (Choi et al., 2008) and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (Bauer and Patterson, 2006; Covey and Levison, 2007; Oshima et al., 2007; Bauer, 2009). Interestingly, microglia cells are abundant along the wall of the ventricles and are in close contact to type-B cells (Figure 3). This suggests a local interaction between immune cells and NSCs. In fact, activated microglia can increase neurogenesis by producing IGF-1 that, in turn, activates the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (Choi et al., 2008). Microglial modulation of NSC may also be mediated by activation of mitogen activated protein kinase C (PKC) and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathways (Morgan et al., 2004).

Figure 3. Microglia in the adult SVZ.

Iba-1 immunocytochemistry to label microglial cells (inset). Note that “resting” microglia is highly branched and displays a typical ‘bushy’ morphology. By electron microscopy, a microglia cell (M) can be easily identified by its dark nucleus and cytoplasm (delineated by the arrows). Electrodense corpuses in the cytoplasm (circles) are commonly found in this type of cells. Note that microglial cytoplasmic expansions (arrows) are in close contact with type-B cells. B: Type-B cell; E: Ependymal cell; V: Ventricle.

Cytokines and NSCs

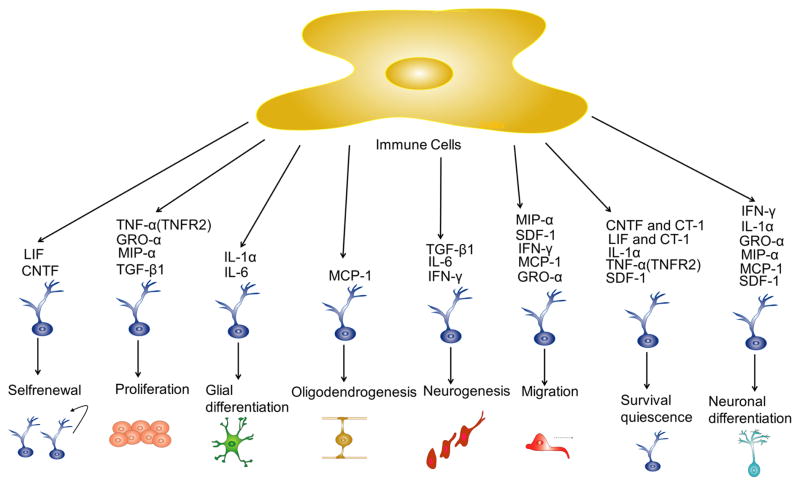

In the brain, an inflammatory process triggers a cascade of molecular and transcriptional events that conclude in a massive production of cytokines from local microglia and infiltrative white blood cells (neutrophils, monocytes and lymphocytes). Neural precursor cells in the adult SVZ express receptors for a range of chemokines, which act as chemoattractants, directing neural precursor cell migration (Tran et al., 2007; Gordon et al., 2009; Gordon et al., 2011). G-protein-coupled chemokine receptors trigger phospholipase C (PLC)/PKC pathway, Janus kinase-signal transducer and JAK/STAT in adult NSCs (Miller et al., 2008; Bauer, 2009). Therefore, pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are able to initiate a myriad of effects in neural progenitor cells of the SVZ and the SGZ. Modulation of NSCs by cytokines depends on their molar concentration, length of inflammatory stimuli, brain region involved and cell subtypes. It has been proposed that according to the properties of the downstream pathway activated, cytokines can modify multiple functions of NSCs, such as quiescence, cell adhesion, migration, differentiation, cytoskeletal rearrangement, self-renewal and cell survival (Figure 4) (Leong and Turnley, 2011). There is a number of pro-inflammatory cytokines that have been involved in NSCs modulation, but only a few of them play a significant role during brain inflammation of CNS, for instance: IL-6, IL-1, TNF-α, MCP-1, LIF, CNTF, cardiotrophin-1 (CT-1), IL-18 and others.

Figure 4. Proinflammatory cytokines and NSCs in the adult brain.

During neuroinflammation microglia and other immune cells produce a myriad of pro-inflammatory cytokines that activate several signaling intracellular pathways, which triggers multiple effects on the adult SGZ and SVZ progenitors.

IL-1

Interleukin 1 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that consists of two distinct proteins: interleukin-1-alpha (IL-1α) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). IL-1α has two binding sites to interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) that is similar, but not identical, to that of IL-1β. IL-1R is expressed in the SGZ in the hippocampus, but is not in the SVZ progenitor cells. Administration of IL-1β protein significantly decreases the number of BrdU (5-Bromo-2′-deouxyuridine) positive cells in the SGZ at the dentate gyrus. The administration of an antagonist protein to the IL-1R can block the stress-induced decrement of cell proliferation in the SGZ. IL-1β also inhibits differentiation of NSCs without affecting cell survival (Koo and Duman, 2008, 2009). Anti-proliferative effects of IL-1β may occur via activation of the NF-κB, JNK or P38 MAPK pathways. (Koo and Duman, 2008; Mathieu et al., 2010). In contrast, IL-1α has showed different effects as promotes neuronal differentiation and cell survival in mesechymal stem cells (Greco and Rameshwar, 2007). Further, IL-1α strongly enhances astrocytic differentiation without affecting cell viability (Ajmone-Cat et al., 2010).

IL-6

Activated microglial cells produce IL-6 that reduces proliferation, differentiation and survival of neural precursor in the SGZ of dentate gyrus (Spooren et al., 2011) and induces differentiation of NSCs into astrocytic lineage (McPherson et al., 2011; Spooren et al., 2011). Interestingly, NSCs do not express a functional receptor for IL-6 (IL-6R), consequently they cannot properly respond to IL-6 stimulation. Instead, IL-6 joins to a soluble form of IL-6R (sIL-6R) that binds to gp-130 and leads to the activation of the JAK/STAT3 pathway and the MAPK cascade (Dominguez et al., 2008). Further, Hyper-IL-6, an active protein derived from IL-6/sIL-6R fusion, induces NSCs to differentiate into glutamate-responsive neurons, oligodendroglia and astrocytes (Islam et al., 2009). Remarkably, GFAP IL-6 transgenic mice, in which IL-6 under the regulatory control of the glial fibrillary acidic protein gene promoter was overexpressed in the CNS, exhibit a severe neurologic impairment characterized by tremor, ataxia, and seizure (Campbell et al., 1993). Neuro-pathologic manifestations include angiogenesis, neurodegeneration, astrocytosis, and induction of acute-phase-protein production (Campbell et al., 1993). Interestingly, IL-6 promotes peripheral nerve regeneration and neuronal sprouting in the nigro-striatal pathway (Grunblatt et al., 2000). IL-6 has also shown to improve postnatal survival of cultured mesencephalic catecholaminergic and septal cholinergic neurons (Hama et al., 1991).

TNF-α

Decreased neurogenesis has been observed by effect of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (Whitney et al., 2009). TNF-α reduces the number of newly born and post-mitotic neurons, increases astrocyte population and increases expression of the anti-neurogenic hairy and enhancer of split-1 gene (Hes1), which suggest that TNF-α has a detrimental effect on neuronal lineage fate via the transcriptional repressor Hes1 (Keohane et al., 2009). Interestingly, it seems that TNF-α has both negative and positive actions on neurogenesis depending on the subtype of receptor activated. Thus, when TNF-α binds to TNFR1 receptor neurogenesis is inhibited and when it binds to TNFR2 receptor proliferation and survival of NSCs is enhanced (Iosif et al., 2006; Gomez-Nicola et al., 2011). TNF-α-induced proliferation of adult neural stem cells occurs via activation of canonical NF-kappaB pathway: IKK-β activates NF-kappaB signaling, which results in activation of NF-kappaB followed by up-regulation of the target gene cyclin D1 (Widera et al., 2006). TNF-α also promotes the production of chemokines that alters differentiation and migration of neural precursors. During inflammation, TNF-α increases the expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1, also known as MCP-1 or CCL2, which enhances migration of NSCs from the SVZ (Schwamborn et al., 2003; Widera et al., 2004; Gordon et al., 2012). MCP-1 also increases both neuronal and oligodendrocytic differentiation, while decreases astrocytic differentiation (Gordon et al., 2011). The mechanism by which the MCP-1 alters the fate choice of neural precursor cells is currently unknown, but it appears to involve changes on NeuroD expression (Boutin et al., 2010).

IFN-γ

The inflammatory cytokine IFN-γ promotes neural differentiation and neurite outgrowth of murine adult NSCs (Wong et al., 2004; Johansson et al., 2008) and the human neuroblastoma cells (Song et al., 2005). IFN-γ-induced activation of microglia enhances neurogenesis (Butovsky et al., 2006). IFN-γ regulates the expression of cytokine and chemokine receptors (MCP-1/CCL2, CXCR4 and CCR5) in astrocytes (Leong and Turnley, 2011). Chemokine receptors modulate NSCs differentiation as found in a mouse model of demyelination, where CXCR4 promoted differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (Gordon et al., 2012). On the other hand, CCL2 chemokine promotes neuronal differentiation of SVZ progenitors without affecting NSCs proliferation and survival (Liu et al., 2007). It has been reported that hydrogels enriched with IFN-γ provides suitable substrate for the differentiation of NSCs into neurons (Leipzig et al., 2010). Pro-neuronal differentiation induced by IFN-γ is mediated by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways (Kim et al., 2007), which is also required for neuronal differentiation of embryonic stem cells and PC12 cells (Wang et al., 2001; Zentrich et al., 2002; Akiyama et al., 2004; Amura et al., 2005). IFN-γ has shown a dual effect on NSCs, because not only stimulates neuronal differentiation, but also promotes migration and reduces proliferation and cell survival of neural progenitors (Ben-Hur et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2004; Song et al., 2005). Reduction in proliferation and survival activated by IFN-γ receptors is mediated through STAT/1 signaling pathway (Makela et al., 2010).

IL-15

IL-15 is up-regulated during inflammation by activated microglial and reactive astrocytes. IL-15 has been proposed as a regulator of neurogenesis because it is expressed by the NSCs in the SVZ and the rostral migratory stream (Gomez-Nicola et al., 2011). IL-15 reduces proliferation, differentiation and self-renewal of NSCs as shown in IL-15-knockout mice, which exhibit deficient proliferation and self-renewal (Huang et al., 2009; Gomez-Nicola et al., 2011). IL-15 stimulation triggers MAPK (also known as ERK) pathway and activates JAK1 and STAT3/5 in microglia cells. Thus, IL-15 deficiency leads to a defective activation of JAK/STAT and ERK MAPK pathways in cultured NSCs (Gomez-Nicola et al., 2011).

IL-18

Interleukin 18 (IL-18) is another proinflammatory cytokine that act as a cofactor with IL-12 to generate IFN-γ-producing TH1 cells. Microglia and astrocytes are potential sources of IL-18 into the brain. IL-18 receptor (IL-18R) has two isoforms known: IL-18Rα and IL-18Rβ subunits, both of them are expressed by neurons. IL-18 inhibits neuronal differentiation and induces neuronal apoptosis in neural progenitor cells (Liu et al., 2005; Alboni et al., 2010). Interestingly, IL-18 is also produced by ependymal cells, but its role in the adult SVZ niche has not been fully determined (Alboni et al., 2010).

LIF, CNTF and CT-1

Leukemia inhibitory factor causes production of acute phase proteins that are necessary for promoting the fever induced by TNF and IL-1. Acute LIF or CNTF exposure stimulates the amplification and self-renewal of NSCs derived from the SVZ (Bauer and Patterson, 2006; Covey and Levison, 2007; Oshima et al., 2007). In contrasts, chronic exposure to LIF or CNTF alters the formation of NSC progenies and promotes self-renewal of SVZ progenitor cells (Bauer, 2009). Interestingly, combined actions of LIF, CNTF and CT-1 modulate survival and function of motor neurons, where LIF specifically controls the motor endplate size (Matsumoto et al., 2011). These effects of LIF seem to be mainly mediated by intracellular phosphorylation of STAT3 (Burdon et al., 2002).

Other cytokines and chemokines

Other proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines can also modulate neurogenic niches. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-α) and grow regulated oncogene-alpha (GRO-α) not only instruct migration, but also proliferation and differentiation of neural precursors (Eugenin et al., 2003; Tran et al., 2007; Gordon et al., 2009; Gordon et al., 2011, 2012). CXCL12 chemokyne, also known as stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), induces migration and increases survival of precursor cells (Molyneaux et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2004; Widera et al., 2004). SDF-1 also promotes quiescence (Krathwohl and Kaiser, 2004) and proliferation of neural progenitors (Gong et al., 2006). CXCL12/CVCR4 may support quiescence and inhibit proliferation of NPCs (Leong and Turnley, 2011). Chemokine migration is triggered by Rho-family molecules that induce cytoskeletal changes. Evidence indicates that inhibition of the Rho signaling pathway has a range of effects on NSCs function (Leong and Turnley, 2011; Turbic et al., 2011).

There are cytokines that inhibits the synthesis of TNF-α, prostaglandins, nitric oxide or eicosanoids, which decreases inflammation. These anti-inflammatory molecules can also generate changes on NSCs. Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) enhances cell proliferation in the dentate gyrus, without changing neuronal fate in the SGZ (Battista et al., 2006). Adenoviral-mediated delivery of TGF-β1 increase neurogenesis in the adult SVZ (Mathieu et al., 2010). IL-10 induces immunosuppression and promotes remyelination and neuronal repair (Yang et al., 2009). IL-4-treated microglia promotes oligodendroglial lineage via the IGF-1 signaling pathway (Mathieu et al., 2010).

Proinflammatory cytokines and NSCs in neurodegenerative diseases

Neuroinflammation may occur after traumatic brain injuries, infections, autoimmunity or stroke (Kabatas et al., 2011; Kasahara et al., 2011). Immune cells and proinflammatory cytokines are important mediators of neural regeneration after injury. Immunodeficient mice depleted of CD4+ T lymphocytes have less apoptosis and high proliferation of NSCs following stroke (Saino et al., 2010). Proinflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease (Giunta et al., 2012), Parkinson’s disease (Mertens et al., 2010), Huntington’s disease (Soulet and Cicchetti, 2011), epilepsy (Vezzani et al., 2011) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Philips and Robberecht, 2011). Chronic inflammation has also been related to the initiation of the depressive symptoms observed in neurodegenerative diseases as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease (Leonard, 2010; Mertens et al., 2010; Wuwongse et al., 2010). Notably, the brain of patients or animal models with neurodegenerative disorders exhibit alterations in their neurogenic niches (Curtis et al., 2007). The SGZ of patients with Alzheimer’s disease shows an increase in the expression of doublecortin and polysialylated nerve cell adhesion protein, markers for immature neuronal cells (Jin et al., 2004a). These data agree with an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease (Jin et al., 2004b), but disagree with another report indicating that knock-our mice for preseninlin-1 and amyloid protein precursor show a deficient neurogenesis in the SGZ (Feng et al., 2001; Wen et al., 2002). The SVZ of patients with Huntington’s disease overexpresses the proliferating cell nuclear antigen and β-tubulin (a marker of neuroblasts) (Curtis et al., 2003). Striatal lesions in mice promote SVZ neurogenesis and cell reactivity as that observed in Huntington’s disease (Jin et al., 2004b). Animal models have also shown that seizures enhance adult neurogenesis in the SVZ and the SGZ of epileptic mice (Parent et al., 1997). Taken together, this evidence indicates that neuroinflammation is involved in the etiology of a broad range of neurological diseases and stem cell modulation. However, the significance of the modulation of adult neurogenesis in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders remains to be elucidated.

Promising therapeutic approaches for neural immunomodulation

Basically, two therapeutic approaches for the manipulation of stem-cell progenitors can be considered: the stem-cell transplantation and the stimulation of endogenous neural progenitors. Notably, the cross-talk between immune cells and NSCs appears to determine the efficacy of endogenous regenerative responses, as well as the fate and functional integration of grafted NSPCs (Kokaia et al., 2012). In models of stroke and neurodegenerative diseases, it has been observed that endogenous SVZ progenitors actively migrate into the injured area (Cooper and Isacson, 2004; Yamashita et al., 2006; Gonzalez-Perez and Alvarez-Buylla, 2011). Vaccination with the immunomodulator glatiramer (also known as Copolymer 1, Cop-1, or Copaxone) increases oligodendrogenesis and promotes myelin repair in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, a model of multiple sclerosis (Skihar et al., 2009). These data suggests that neural regeneration may be attained by stimulating endogenous SVZ progenitors with immunological cytokines.

On the other hand, NSCs transplantation promotes tissue repair by replacing neural cells and modulating the innate immune response (Martino et al., 2011). Transplanted NSCs can also act as immunomodulators that promote neural regeneration (Kokaia et al., 2012). Therefore, transplantation of NSCs has been proposed as an alternative therapy in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, Huntington’s disease and stroke (Lindvall and Kokaia, 2010). To date, the function of newborn cells derived from NSC is still questioned and remains to be completely elucidated. Hence, the significance of the modulation of adult neurogenesis by immunological cytokines in neurological disorders can only be speculated. Newborn cells may represent a regenerative attempt to repair cerebral parenchyma, while the immune system modulates the function of NSCs through cytokine and toll-like receptors. Therefore, pro-inflammatory cytokines produced during some neurological disorders or cell transplantation procedures may affect the success of stem-cell-based therapies (Pluchino et al., 2005). In fact, this also suggests that immuno-depressed mice may not be an ideal model to predict the success of stem-cell-based therapies in humans. Besides, survival and integration of transplanted NPCs in the human brain is to be elucidated.

Conclusion

In summary, the current literature indicates that pro-inflammatory cytokines inhibit neurogenesis, whereas anti-inflammatory cytokines generally enhance neurogenesis. Proinflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders and regulate neurogenesis in the adult SGZ and SVZ, but the significance of this modulation remains to be understood. The control of neuroinflammation has important implications for cellular therapy in two different directions: 1) It may limit the therapeutic potential of transplanted adult NSCs or 2) It may promote the regenerative potential of endogenous neural precursors. Therefore, pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines may have both detrimental and beneficial effects on the regulation of adult NSCs. Thus, future stem-cell-based therapies may involve therapeutic strategies to regulate the production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Yet, future studies are needed to unveil the molecular mechanisms governing the interaction between neural stem cells and the immune system, as well as its implications for cellular therapy

Proinflammatory cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders

Cytokines and immune mediators regulate neurogenic niches in the adult brain

Neuroinflammation can limit the therapeutic use of grafted neural stem cells (NSCs)

However, neuroinflammation can also promote the regenerative potential of NSCs

Stem-cell-based therapies should involve the regulation of immune system mediators

Acknowledgments

The authors were supported by CONACyT’s (CB-2008-101476), The National Institute of Health and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS; R01 NS070024), the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ciberned, Centro de Investigacion Principe Felipe y Red de Terapia Celular, and the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (SAF2008-01274).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguirre A, Dupree JL, Mangin JM, Gallo V. A functional role for EGFR signaling in myelination and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:990–1002. doi: 10.1038/nn1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimone JB, Deng W, Gage FH. Resolving new memories: a critical look at the dentate gyrus, adult neurogenesis, and pattern separation. Neuron. 2011;70:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajmone-Cat MA, Cacci E, Ragazzoni Y, Minghetti L, Biagioni S. Pro-gliogenic effect of IL-1alpha in the differentiation of embryonic neural precursor cells in vitro. J Neurochem. 2010;113:1060–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama S, Yonezawa T, Kudo TA, Li MG, Wang H, Ito M, Yoshioka K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Kanamaru R, Tamura S, Kobayashi T. Activation mechanism of c-Jun amino-terminal kinase in the course of neural differentiation of P19 embryonic carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36616–36620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alboni S, Cervia D, Sugama S, Conti B. Interleukin 18 in the CNS. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Tramontin AD. A unified hypothesis on the lineage of neural stem cells. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2(2):287–293. doi: 10.1038/35067582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amura CR, Marek L, Winn RA, Heasley LE. Inhibited neurogenesis in JNK1-deficient embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10791–10802. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10791-10802.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battista D, Ferrari CC, Gage FH, Pitossi FJ. Neurogenic niche modulation by activated microglia: transforming growth factor beta increases neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23:83–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S. Cytokine control of adult neural stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1153:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Patterson PH. Leukemia inhibitory factor promotes neural stem cell self-renewal in the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12089–12099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3047-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hur T, Ben-Menachem O, Furer V, Einstein O, Mizrachi-Kol R, Grigoriadis N. Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on the growth, fate, and motility of multipotential neural precursor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:623–631. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonecchi R, Galliera E, Borroni EM, Corsi MM, Locati M, Mantovani A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: an overview. Front Biosci. 2009;14:540–551. doi: 10.2741/3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti L. From hydra regeneration to human brain structural plasticity: a long trip through narrowing roads. Scientific World Journal. 2011;11:1270–1299. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutin C, Hardt O, de Chevigny A, Core N, Goebbels S, Seidenfaden R, Bosio A, Cremer H. NeuroD1 induces terminal neuronal differentiation in olfactory neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1201–1206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdon T, Smith A, Savatier P. Signalling, cell cycle and pluripotency in embryonic stem cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:432–438. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Ziv Y, Schwartz A, Landa G, Talpalar AE, Pluchino S, Martino G, Schwartz M. Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-gamma differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IL, Abraham CR, Masliah E, Kemper P, Inglis JD, Oldstone MB, Mucke L. Neurologic disease induced in transgenic mice by cerebral overexpression of interleukin 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10061–10065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper O, Isacson O. Intrastriatal transforming growth factor alpha delivery to a model of Parkinson’s disease induces proliferation and migration of endogenous adult neural progenitor cells without differentiation into dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8924–8931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2344-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordiglieri C, Farina C. Astrocytes Exert and Control Immune Responses in the Brain. Current Immunology Reviews. 2010;6:150–159. [Google Scholar]

- Costa RA, Ruiz-de-Souza V, Azevedo GM, Jr, Gava E, Kitten GT, Vaz NM, Carvalho CR. Indirect effects of oral tolerance improve wound healing in skin. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19:487–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey MV, Levison SW. Leukemia inhibitory factor participates in the expansion of neural stem/progenitors after perinatal hypoxia/ischemia. Neuroscience. 2007;148:501–509. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROSCIENCE.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig CG, Tropepe V, Morshead CM, Reynolds BA, Weiss S, Van der Kooy D. In vivo growth factor expansion of endogenous subependymal neural precursor cell populations in the adult mouse brain. JNeurosci. 1996;16:2649–2658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02649.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Faull RL, Eriksson PS. The effect of neurodegenerative diseases on the subventricular zone. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:712–723. doi: 10.1038/nrn2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MA, Penney EB, Pearson AG, van Roon-Mom WM, Butterworth NJ, Dragunow M, Connor B, Faull RL. Increased cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult human Huntington’s disease brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9023–9027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1532244100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YS, Cho HY, Hoyt KR, Naegele JR, Obrietan K. IGF-1 receptor-mediated ERK/MAPK signaling couples status epilepticus to progenitor cell proliferation in the subgranular layer of the dentate gyrus. Glia. 2008;56:791–800. doi: 10.1002/glia.20653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Basu A. Inflammation: a new candidate in modulating adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1199–1208. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Aimone JB, Gage FH. New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:339–350. doi: 10.1038/nrn2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez E, Rivat C, Pommier B, Mauborgne A, Pohl M. JAK/STAT3 pathway is activated in spinal cord microglia after peripheral nerve injury and contributes to neuropathic pain development in rat. J Neurochem. 2008;107:50–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl CT, Claasen JH, Bonde S, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O. Inflammation is detrimental for neurogenesis in adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13632–13637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234031100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugenin EA, D’Aversa TG, Lopez L, Calderon TM, Berman JW. MCP-1 (CCL2) protects human neurons and astrocytes from NMDA or HIV-tat-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1299–1311. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy GH, Sicard RE. A role for effectors of cellular immunity in epimorphic regeneration of amphibian limbs. In Vivo. 2002;16:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R, Rampon C, Tang YP, Shrom D, Jin J, Kyin M, Sopher B, Miller MW, Ware CB, Martin GM, Kim SH, Langdon RB, Sisodia SS, Tsien JZ. Deficient neurogenesis in forebrain-specific presenilin-1 knockout mice is associated with reduced clearance of hippocampal memory traces. Neuron. 2001;32:911–926. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:612–613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00612.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galileo DS, Gray GE, Owens GC, Majors J, Sanes JR. Neurons and glia arise from a common progenitor in chicken optic tectum: Demonstration with two retroviruses and cell type-specific antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:458–462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvao RP, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling does not stimulate subventricular zone neurogenesis in adult mice and rats. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13368–13383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2918-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez-Contreras AY, Gonzalez-Castaneda RE, Luquin S, Gonzalez-Perez O. Role of fibroblast growth factor receptors in astrocytic stem cells. Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2012;7:81–86. doi: 10.2174/157436212799278205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giunta B, Obregon D, Velisetty R, Sanberg PR, Borlongan CV, Tan J. The immunology of traumatic brain injury: a prime target for Alzheimer inverted question marks disease prevention. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:185. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Nicola D, Valle-Argos B, Pallas-Bazarra N, Nieto-Sampedro M. Interleukin-15 regulates proliferation and self-renewal of adult neural stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1960–1970. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-01-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, He X, Qi L, Zuo H, Xie Z. Stromal cell derived factor-1 acutely promotes neural progenitor cell proliferation in vitro by a mechanism involving the ERK1/2 and PI-3K signal pathways. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Castaneda RE, Galvez-Contreras AY, Luquin S, Gonzalez-Perez O. Neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease: a realistic alternative to neuronal degeneration? Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2011;6:314–319. doi: 10.2174/157436211797483949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez O, Quinones-Hinojosa A. Dose-dependent effect of EGF on migration and differentiation of adult subventricular zone astrocytes. Glia. 2010;58:975–983. doi: 10.1002/glia.20979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez O, Alvarez-Buylla A. Oligodendrogenesis in the subventricular zone and the role of epidermal growth factor. Brain Res Rev. 2011;67:147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez O, Ramos-Remus C, Garcia-Estrada J, Luquin S. Prednisone induces anxiety and glial cerebral changes in rats. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:2529–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez O, Romero-Rodriguez R, Soriano-Navarro M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Epidermal Growth Factor Induces the Progeny of Subventricular Zone Type B Cells to Migrate and Differentiate into Oligodendrocytes. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2032–2043. doi: 10.1002/stem.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perez O, Chavez-Casillas O, Jauregui-Huerta F, Lopez-Virgen V, Guzman-Muniz J, Moy-Lopez N, Gonzalez-Castaneda RE, Luquin S. Stress by noise produces differential effects on the proliferation rate of radial astrocytes and survival of neuroblasts in the adult subgranular zone. Neurosci Res. 2011;70:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RJ, McGregor AL, Connor B. Chemokines direct neural progenitor cell migration following striatal cell loss. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;41:219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RJ, Mehrabi NF, Maucksch C, Connor B. Chemokines influence the migration and fate of neural precursor cells from the young adult and middle-aged rat subventricular zone. Exp Neurol. 2011;233:587–594. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RJ, Mehrabi NF, Maucksch C, Connor B. Chemokines influence the migration and fate of neural precursor cells from the young adult and middle-aged rat subventricular zone. Exp Neurol. 2012;233:587–594. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco SJ, Rameshwar P. Enhancing effect of IL-1alpha on neurogenesis from adult human mesenchymal stem cells: implication for inflammatory mediators in regenerative medicine. J Immunol. 2007;179:3342–3350. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunblatt E, Mandel S, Youdim MB. Neuroprotective strategies in Parkinson’s disease using the models of 6-hydroxydopamine and MPTP. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;899:262–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama T, Kushima Y, Miyamoto M, Kubota M, Takei N, Hatanaka H. Interleukin-6 improves the survival of mesencephalic catecholaminergic and septal cholinergic neurons from postnatal, two-week-old rats in cultures. Neuroscience. 1991;40:445–452. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harty M, Neff AW, King MW, Mescher AL. Regeneration or scarring: an immunologic perspective. Dev Dyn. 2003;226:268–279. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey WF. Leukocyte traffic in the central nervous system: the participants and their roles. Semin Immunol. 1999;11:125–137. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YS, Cheng SN, Chueh SH, Tsai YL, Liou NH, Guo YW, Liao MH, Shen LH, Chen CC, Liu JC, Ma KH. Effects of interleukin-15 on neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells. Brain Res. 2009;1304:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iosif RE, Ekdahl CT, Ahlenius H, Pronk CJ, Bonde S, Kokaia Z, Jacobsen SE, Lindvall O. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 is a negative regulator of progenitor proliferation in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9703–9712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2723-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam O, Gong X, Rose-John S, Heese K. Interleukin-6 and neural stem cells: more than gliogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:188–199. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Gil-Perotin S, Roy M, Quinones-Hinojosa A, VandenBerg S, Alvarez-Buylla A. PDGFR alpha-positive B cells are neural stem cells in the adult SVZ that form glioma-like growths in response to increased PDGF signaling. Neuron. 2006;51:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauregui-Huerta F, Ruvalcaba-Delgadillo Y, Gonzalez-Castaneda R, Garcia-Estrada J, Gonzalez-Perez O, Luquin S. Responses of glial cells to stress and glucocorticoids. Curr Immunol Rev. 2010;6:195–204. doi: 10.2174/157339510791823790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Peel AL, Mao XO, Xie L, Cottrell BA, Henshall DC, Greenberg DA. Increased hippocampal neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004a;101:343–347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin K, Galvan V, Xie L, Mao XO, Gorostiza OF, Bredesen DE, Greenberg DA. Enhanced neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic (PDGF-APPSw, Ind) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004b;101:13363–13367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403678101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson S, Price J, Modo M. Effect of inflammatory cytokines on major histocompatibility complex expression and differentiation of human neural stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2444–2454. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabatas S, Cansever TEC, Yilmaz C. The Therapeutic Potential of Neural Stem Cells in Traumatic Brain Injuries. Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2011;6:327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara Y, Nakagomi T, Nakano-Doi A, Matsuyama T, Taguchi A. The Therapeutic Potential of Neural Stem Cells in Cerebral Ischemia. Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2011;6:347–352. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane A, Ryan S, Maloney E, Sullivan AM, Nolan YM. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha impairs neuronal differentiation but not proliferation of hippocampal neural precursor cells: Role of Hes1. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;43:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Son TG, Kim K, Park HR, Mattson MP, Lee J. Interferon-gamma promotes differentiation of neural progenitor cells via the JNK pathway. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1399–1406. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9323-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokaia Z, Martino G, Schwartz M, Lindvall O. Cross-talk between neural stem cells and immune cells: the key to better brain repair? Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1078–1087. doi: 10.1038/nn.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E, Goderie S, Wang Y, Lotz S, Lin G, Sun Y, Roysam B, Shen Q, Temple S. Adult SVZ lineage cells home to and leave the vascular niche via differential responses to SDF1/CXCR4 signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JW, Duman RS. IL-1beta is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:751–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708092105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo JW, Duman RS. Evidence for IL-1 receptor blockade as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of depression. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:664–671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krathwohl MD, Kaiser JL. HIV-1 promotes quiescence in human neural progenitor cells. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:216–226. doi: 10.1086/422008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegstein A, Alvarez-Buylla A. The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:149–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn HG, Winkler J, Kempermann G, Thal LJ, Gage FH. Epidermal growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2 have different effects on neural progenitors in the adult rat brain. JNeurosci. 1997;17:5820–5829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05820.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai K, Kaspar BK, Gage FH, Schaffer DV. Sonic hedgehog regulates adult neural progenitor proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:21–27. doi: 10.1038/nn983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipzig ND, Xu C, Zahir T, Shoichet MS. Functional immobilization of interferon-gamma induces neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;93:625–633. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard BE. The concept of depression as a dysfunction of the immune system. Curr Immunol Rev. 2010;6:205–212. doi: 10.2174/157339510791823835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong SY, Turnley AM. Regulation of adult neural precursor cell migration. Neurochem Int. 2011;59:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindvall O, Kokaia Z. Stem cells in human neurodegenerative disorders--time for clinical translation? J Clin Invest. 2010;120:29–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI40543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XS, Zhang ZG, Zhang RL, Gregg SR, Wang L, Yier T, Chopp M. Chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) induces migration and differentiation of subventricular zone cells after stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2120–2125. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YP, Lin HI, Tzeng SF. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-18 modulate neuronal cell fate in embryonic neural progenitor culture. Brain Res. 2005;1054:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Proliferating subventricular zone cells in the adult mammalian forebrain can differentiate into neurons and glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2074–2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machold R, Hayashi S, Rutlin M, Muzumdar MD, Nery S, Corbin JG, Gritli-Linde A, Dellovade T, Porter JA, Rubin LL, Dudek H, McMahon AP, Fishell G. Sonic hedgehog is required for progenitor cell maintenance in telencephalic stem cell niches. Neuron. 2003;39:937–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makela J, Koivuniemi R, Korhonen L, Lindholm D. Interferon-gamma produced by microglia and the neuropeptide PACAP have opposite effects on the viability of neural progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino G, Pluchino S, Bonfanti L, Schwartz M. Brain regeneration in physiology and pathology: the immune signature driving therapeutic plasticity of neural stem cells. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1281–1304. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu P, Battista D, Depino A, Roca V, Graciarena M, Pitossi F. The more you have, the less you get: the functional role of inflammation on neuronal differentiation of endogenous and transplanted neural stem cells in the adult brain. J Neurochem. 2010;112:1368–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A, Onoyama I, Sunabori T, Kageyama R, Okano H, Nakayama KI. Fbxw7-dependent degradation of Notch is required for control of “stemness” and neuronal-glial differentiation in neural stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13754–13764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson CA, Aoyama M, Harry GJ. Interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 regulation of neural progenitor cell proliferation with hippocampal injury: differential regulatory pathways in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the adolescent and mature mouse brain. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:850–862. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menn B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yaschine C, Gonzalez-Perez O, Rowitch D, Alvarez-Buylla A. Origin of oligodendrocytes in the subventricular zone of the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7907–7918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1299-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens B, Vanderheyden P, Michotte Y, Sarre S. The role of the central renin-angiotensin system in Parkinson’s disease. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2010;11:49–56. doi: 10.1177/1470320309347789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mescher AL, Neff AW. Limb regeneration in amphibians: immunological considerations. Scientific World Journal. 2006;6(Suppl 1):1–11. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RJ, Rostene W, Apartis E, Banisadr G, Biber K, Milligan ED, White FA, Zhang J. Chemokine action in the nervous system. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11792–11795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3588-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011;70:687–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh Z, Merkle FT, Soriano-Navarro M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Neural stem cells confer unique pinwheel architecture to the ventricular surface in neurogenic regions of the adult brain. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrecic D, Nicaise C, Gajovic S, Pochet R. The Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cells in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2011;6:341–346. [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux KA, Zinszner H, Kunwar PS, Schaible K, Stebler J, Sunshine MJ, O’Brien W, Raz E, Littman D, Wylie C, Lehmann R. The chemokine SDF1/CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 regulate mouse germ cell migration and survival. Development. 2003;130:4279–4286. doi: 10.1242/dev.00640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mongiat LA, Schinder AF. Adult neurogenesis and the plasticity of the dentate gyrus network. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monje ML, Toda H, Palmer TD. Inflammatory blockade restores adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science. 2003;302:1760–1765. doi: 10.1126/science.1088417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SC, Taylor DL, Pocock JM. Microglia release activators of neuronal proliferation mediated by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt and delta-Notch signalling cascades. J Neurochem. 2004;90:89–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller N, Schwarz MJ. Immune System and Schizophrenia. Curr Immunol Rev. 2010;6:213–220. doi: 10.2174/157339510791823673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagomi N, Nakagomi T, Kubo S, Nakano-Doi A, Saino O, Takata M, Yoshikawa H, Stern DM, Matsuyama T, Taguchi A. Endothelial cells support survival, proliferation, and neuronal differentiation of transplanted adult ischemia-induced neural stem/progenitor cells after cerebral infarction. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2185–2195. doi: 10.1002/stem.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northrop NA, Yamamoto BK. Neuroimmune pharmacology from a neuroscience perspective. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011;6:10–19. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9239-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima K, Teo DT, Senn P, Starlinger V, Heller S. LIF promotes neurogenesis and maintains neural precursors in cell populations derived from spiral ganglion stem cells. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent JM, Yu TW, Leibowitz RT, Geschwind DH, Sloviter RS, Lowenstein DH. Dentate granule cell neurogenesis is increased by seizures and contributes to aberrant network reorganization in the adult rat hippocampus. JNeurosci. 1997;17:3727–3738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03727.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechnick RN, Zonis S, Wawrowsky K, Cosgayon R, Farrokhi C, Lacayo L, Chesnokova V. Antidepressants stimulate hippocampal neurogenesis by inhibiting p21 expression in the subgranular zone of the hipppocampus. PLoS One. 2012;6:e27290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Huang Y, Rose J, Erichsen D, Herek S, Fujii N, Tamamura H, Zheng J. Stromal cell-derived factor 1-mediated CXCR4 signaling in rat and human cortical neural progenitor cells. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:35–50. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips T, Robberecht W. Neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: role of glial activation in motor neuron disease. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:253–263. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piatti VC, Davies-Sala MG, Esposito MS, Mongiat LA, Trinchero MF, Schinder AF. The timing for neuronal maturation in the adult hippocampus is modulated by local network activity. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7715–7728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1380-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluchino S, Zanotti L, Rossi B, Brambilla E, Ottoboni L, Salani G, Martinello M, Cattalini A, Bergami A, Furlan R, Comi G, Constantin G, Martino G. Neurosphere-derived multipotent precursors promote neuroprotection by an immunomodulatory mechanism. Nature. 2005;436:266–271. doi: 10.1038/nature03889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Remus C, Duran-Barragan S. Neurological Involvement in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Current Immunology Reviews. 2010;6:174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera FJ, Kraus J, Steffenhagen C, Kury P, Weidner N, Aigner L. Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis: The Therapeutic Potential of Neural and Mesenchymal Stem/Progenitor Cells. Curr Signal Transduct Ther. 2011;6:293–313. [Google Scholar]

- Saino O, Taguchi A, Nakagomi T, Nakano-Doi A, Kashiwamura S, Doe N, Nakagomi N, Soma T, Yoshikawa H, Stern DM, Okamura H, Matsuyama T. Immunodeficiency reduces neural stem/progenitor cell apoptosis and enhances neurogenesis in the cerebral cortex after stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:2385–2397. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanai N, Tramontin AD, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Barbaro NM, Gupta N, Kunwar S, Lawton MT, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Manuel-Garcia Verdugo J, Berger MS, Alvarez-Buylla A. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature. 2004;427:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamoto K, Wichterle H, Gonzalez-Perez O, Cholfin JA, Yamada M, Spassky N, Murcia NS, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Marin O, Rubenstein JL, Tessier-Lavigne M, Okano H, Alvarez-Buylla A. New neurons follow the flow of cerebrospinal fluid in the adult brain. Science. 2006;311:629–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1119133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamborn J, Lindecke A, Elvers M, Horejschi V, Kerick M, Rafigh M, Pfeiffer J, Prullage M, Kaltschmidt B, Kaltschmidt C. Microarray analysis of tumor necrosis factor alpha induced gene expression in U373 human glioblastoma cells. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seri B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, McEwen BS, Alvarez-Buylla A. Astrocytes give rise to new neurons in the adult mammalian hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7153–7160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07153.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seri B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Collado-Morente L, McEwen BS, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cell types, lineage, and architecture of the germinal zone in the adult dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2004;478:359–378. doi: 10.1002/cne.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Wang Y, Kokovay E, Lin G, Chuang SM, Goderie SK, Roysam B, Temple S. Adult SVZ stem cells lie in a vascular niche: a quantitative analysis of niche cell-cell interactions. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicard RE. Blood cells and their role in regeneration. I. Changes in circulating blood cell counts during forelimb regeneration. Exp Cell Biol. 1983;51:51–59. doi: 10.1159/000163173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skihar V, Silva C, Chojnacki A, Doring A, Stallcup WB, Weiss S, Yong VW. Promoting oligodendrogenesis and myelin repair using the multiple sclerosis medication glatiramer acetate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17992–17997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909607106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So K, Moriya T, Nishitani S, Takahashi H, Shinohara K. The olfactory conditioning in the early postnatal period stimulated neural stem/progenitor cells in the subventricular zone and increased neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb of rats. Neuroscience. 2008;151:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JH, Wang CX, Song DK, Wang P, Shuaib A, Hao C. Interferon gamma induces neurite outgrowth by up-regulation of p35 neuron-specific cyclin-dependent kinase 5 activator via activation of ERK1/2 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12896–12901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulet D, Cicchetti F. The role of immunity in Huntington’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:889–902. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooren A, Kolmus K, Laureys G, Clinckers R, De Keyser J, Haegeman G, Gerlo S. Interleukin-6, a mental cytokine. Brain Res Rev. 2011;67:157–183. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassava RA, Olsen CL. Higher vertebrates do not regenerate digits and legs because the wound epidermis is not functional. A hypothesis. Differentiation. 1982;22:151–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1982.tb01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie M, Van der Veken L, Silva-Vargas V, Louissaint M, Colonna L, Zaidi B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Doetsch F. A specialized vascular niche for adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple S. The development of neural stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:112–117. doi: 10.1038/35102174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepavcevic V, Lazarini F, Alfaro-Cervello C, Kerninon C, Yoshikawa K, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Lledo PM, Nait-Oumesmar B, Baron-Van Evercooren A. Inflammation-induced subventricular zone dysfunction leads to olfactory deficits in a targeted mouse model of multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4722–4734. doi: 10.1172/JCI59145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Rauvala H. Immune Functions of Glia and Neurons in the Central Nervous System. Current Immunology Reviews. 2010;6:160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Tournefier A, Laurens V, Chapusot C, Ducoroy P, Padros MR, Salvadori F, Sammut B. Structure of MHC class I and class II cDNAs and possible immunodeficiency linked to class II expression in the Mexican axolotl. Immunol Rev. 1998;166:259–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PB, Banisadr G, Ren D, Chenn A, Miller RJ. Chemokine receptor expression by neural progenitor cells in neurogenic regions of mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2007;500:1007–1033. doi: 10.1002/cne.21229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turbic A, Leong SY, Turnley AM. Chemokines and inflammatory mediators interact to regulate adult murine neural precursor cell proliferation, survival and differentiation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani A, French J, Bartfai T, Baram TZ. The role of inflammation in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:31–40. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zahn J, Moller T, Kettenmann H, Nolte C. Microglial phagocytosis is modulated by pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3851–3856. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199712220-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ikeda S, Kanno S, Guang LM, Ohnishi M, Sasaki M, Kobayashi T, Tamura S. Activation of c-Jun amino-terminal kinase is required for retinoic acid-induced neural differentiation of P19 embryonal carcinoma cells. FEBS Lett. 2001;503:91–96. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen PH, Shao X, Shao Z, Hof PR, Wisniewski T, Kelley K, Friedrich VL, Jr, Ho L, Pasinetti GM, Shioi J, Robakis NK, Elder GA. Overexpression of wild type but not an FAD mutant presenilin-1 promotes neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adult mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:8–19. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney NP, Eidem TM, Peng H, Huang Y, Zheng JC. Inflammation mediates varying effects in neurogenesis: relevance to the pathogenesis of brain injury and neurodegenerative disorders. J Neurochem. 2009;108:1343–1359. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera D, Mikenberg I, Elvers M, Kaltschmidt C, Kaltschmidt B. Tumor necrosis factor alpha triggers proliferation of adult neural stem cells via IKK/NF-kappaB signaling. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera D, Holtkamp W, Entschladen F, Niggemann B, Zanker K, Kaltschmidt B, Kaltschmidt C. MCP-1 induces migration of adult neural stem cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:381–387. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Goldshmit Y, Turnley AM. Interferon-gamma but not TNF alpha promotes neuronal differentiation and neurite outgrowth of murine adult neural stem cells. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuwongse S, Chang RC, Law AC. The putative neurodegenerative links between depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;91:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Ninomiya M, Hernandez Acosta P, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Sunabori T, Sakaguchi M, Adachi K, Kojima T, Hirota Y, Kawase T, Araki N, Abe K, Okano H, Sawamoto K. Subventricular zone-derived neuroblasts migrate and differentiate into mature neurons in the post-stroke adult striatum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6627–6636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0149-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Jiang Z, Fitzgerald DC, Ma C, Yu S, Li H, Zhao Z, Li Y, Ciric B, Curtis M, Rostami A, Zhang GX. Adult neural stem cells expressing IL-10 confer potent immunomodulation and remyelination in experimental autoimmune encephalitis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3678–3691. doi: 10.1172/JCI37914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Zentrich E, Han SY, Pessoa-Brandao L, Butterfield L, Heasley LE. Collaboration of JNKs and ERKs in nerve growth factor regulation of the neurofilament light chain promoter in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4110–4118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell. 2008;132:645–660. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]