Abstract

Cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1) catalyzes conversion of cholesterol (CH) to pregnenolone, the precursor to all steroid hormones. This process proceeds via three sequential monooxygenation reactions: two stereospecific hydroxylations with formation first of 22R-hydroxycholesterol (22-HC) and then 20α,22R-dihydroxycholesterol (20,22-DHC), followed by the C20-C22 bond cleavage. Herein we have employed EPR and ENDOR spectroscopy to characterize the intermediates in the first hydroxylation step by 77K radiolytic one-electron cryoreduction and subsequent annealing of the ternary oxy cytochrome P450scc-cholesterol complex. This approach is fully validated by the demonstration that the cryoreduced ternary complex of oxy-P450scc-CH is catalytically competent and hydroxylates cholesterol to form 22R-HC with no detectable formation of 20-HC, just as occurs under physiological conditions. Cryoreduction of the ternary complex trapped at 77K produces predominantly the hydroperoxy-ferriheme P450scc intermediate, along with a minor fraction of peroxo-ferriheme intermediate that converts into a new hydroperoxo-ferriheme species at 145K. This behavior reveals that the distal pocket of the parent oxy-P450scc-cholesterol complex exhibits an efficient proton delivery network, with an ordered water molecule H-bonded to the distal oxygen of the dioxygen ligand. During annealing of the hydroperoxy-ferric P450scc intermediates at 185K they convert to the primary product complex in which CH has been converted to 22-HC. In this process, the hydroperoxy-ferric intermediate decays with a large sKIE, as expected when proton delivery to the terminal O leads to formation of Compound I (Cpd I). 1H ENDOR measurements of the primary product formed in deuterated solvent show that the heme Fe(III) is coordinated to the 22R-O1H of 22-HC, where the 1H is derived from substrate and exchanges to D after annealing at higher temperatures. These observations establish that Cpd I is agent that hydroxylates CH, rather than the hydroperoxy-ferric heme.

The main precursor of all steroid hormones in vertebrates is pregnenolone which is formed from cholesterol via a three monooxygenation reactions successively catalyzed by P450scc (CYP11A1).1–3 During the first step, cholesterol (CH) is hydroxylated to 22R-hydroxycholesterol (22-HC), which in the second step is converted into 20α,22R dihydroxycholesterol (20,22-DHC). Cleavage of the C20-C22 bond in the third step produces pregnenolone. To our knowledge the active oxygen species has not been experimentally stabled for any one of these three steps of hydroxylation. By analogy with other cytochrome P450 reactions, one might expect that in the first step or two, compound I is the hydroxylating intermediate, while the last step might proceed with the peroxo-ferric intermediate as active species.4–8,9 On the other hand, experiments on the cryoreduction of oxy-CYP19 reported recently by Sligar and coworkers suggested that the peroxo intermediate, rather than Cpd I, is catalytically competent in the hydroxylation of androstenedione to form 19-OH-androstenedione.10

Despite many efforts, direct observation and detailed characterization of the catalytically active intermediates in the monooxygenase reactions of cytochromes P450 remains elusive. There have been reports of short-lived species with optical spectra characteristic of a compound I that are generated during reaction of cytochromes P450 with mCPBA, and that are proposed as hydroxylating species in the monooxygenase cycle.11,12 Only recently, Green and coworker have managed for the first time to freeze-trap compound I (Cpd I), formed in the absence of a bound substrate during reaction of cytochrome P450119 with mCPBA, and to study its EPR and Mossbauer spectra and reactivity.13 The crystallographic structures for binary complexes of ferric cytochromes P450 with substrate allow insights, and the structures of P450scc with bound CH and 22-HC reveal how the active site of this hemeprotein is organized to bind both this initial substrate and its hydroxylation product (Fig 1).14,15 However, these equilibrium structures do not themselves imply a mechanism of the initial monooxygenation reaction. Crystallographic studies with cryoreduced oxy-P450-substrate complexes represent an extremely informative and promising approach, although experimentally quite challenging, but have not been successfully applied to P450scc.16–18 We have previously demonstrated that application of a cryoreduction/annealing protocol in combination with EPR/ENDOR spectroscopy allows an identification of the active species in the catalytic cycle of a heme-monooxygenases.8 Herein, application of this approach demonstrates that CPD I is the reactive heme state in the hydroxylation of cholesterol by CYP11A1 to form 22-HC.

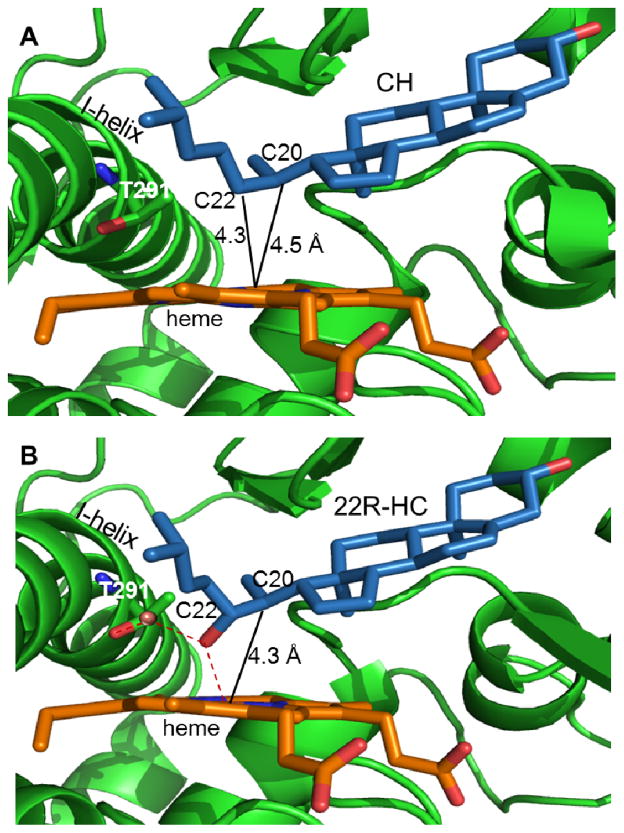

Fig 1.

Active site of CYP11A1 in complex with: cholesterol (A, PDB ID code 3N9Y); 22R-hydroxycholesterol (B, PDB ID code 3N9Z). Water molecules within the active site are represented as red spheres; dashed lines indicate hydrogen bonds; solid lines indicate distance from heme iron to carbon atoms of CH substrate or 22R-HC intermediate (position of subsequent hydroxylation).

Material and methods

Chemicals

Cholesterol (CH), 20α–hydroxycholesterol (20-HC), 22R-hydroxycholesterol (22-HC), sodium dithionite, hydroxypropyl-β–cyclodextrin, sodium cholate, glycerol, glycerol(-OD3) were from Sigma-Aldrich. D2O was obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc. O2 was purchased from Cryogenic Gas Co.

Sample preparation

Mature bovine recombinant P450scc was expressed, purified and concentrated as described.19,20 All experiments on cryoreduction were conducted using 0.25 mM oxy-P450scc in 33% glycerol (v/v) – buffer mixture containing 0.6 M NaCI, 0.04 mM KPi (pH 7.5), 0.2 % sodium cholate and 1 mM CH. When needed, the protein was exchanged into buffers made using D2O and d3-glycerol. In D2O samples, the pH was adjusted to pH 7.1.21 Final concentration of cholesterol was achieved by adding the required volume of stock solution of 10 mM cholesterol in 45% aqueous solution of hydroxypropyl-β–cyclodextrin to the protein solution.

The preparation of oxy-P450scc-cholesterol complex was conducted using modified procedure described by Tuckey.22 The ferrous P450scc samples were made first by incubating the ferric protein in aqueous buffer containing 1.6mM CH in an anaerobic glovebox overnight at 3° C to remove oxygen from the protein solution. An aliquot of a standardized solution of sodium dithionite was added to reduce the ferric P450scc, using 10% excess of dithionite. An extinction coefficient of 8000 M−1 cm−1 at 315 nm was used to determine the concentration of dithionite. Then the reduced protein solution was mixed with oxygen free glycerol. Complete reduction of protein was confirmed spectrophotometrically. The sample of Fe(II)P450scc containing 1mM CH was transferred into EPR tubes. Oxy-P450scc complexes were made by bubbling the Fe(II)P450scc sample at −11°C with 20 ml cold oxygen gas for 40–60s.(under these conditions the half-time of autooxidation of the oxycomplex, is ~ 10min22) The samples were then stored in quartz EPR tubes at 77 K until cryoreduction.

γ-Irradiation of the frozen hemoprotein solutions at 77 K typically was performed for ~20h (dose rate of 0.1 Mrad/h, total dose 2 Mrad) using a Gammacell 220 60Co. Annealing at temperatures over the range 77–270 K was performed by placing the EPR sample in the appropriate bath (e.g., n-pentane or methanol cooled with liquid nitrogen) and then refreezing in liquid nitrogen.

Spectroscopic Techniques

EPR/ENDOR measurements of samples were conducted as previously described.23,24 UV-VIS spectra of the samples in OD 4 mm quartz tubes were measured at 77 K through immersion in a liquid N2 finger dewar with a USB 2000 spectrophotometer (Ocean Optics, Inc.).23

Results

Effect of substrates on EPR/ENDOR of ferri-cytochrome P450scc heme site

We have studied the effect of substrates and products on the EPR/ENDOR spectra of ferric P450scc to provide a reference for assigning specific states that arise during cryoreduction/annealing of the tertiary oxy P450scc-substrate complex.

The low temperature EPR spectrum of ferric P450scc in the presence of cholesterol exhibits a high-spin (S=5/2) EPR signal, g = [8.09, 3.59, 1.69] plus a weak low-spin (S=1/2) signal, g = [2.43, 2.25, 1.917] (Table 1, Fig S1). The high-spin signal is assigned to the conformational sub-state with penta-coordinated heme iron (III), as seen in the crystal structure (Fig 1); the low-spin signal is characteristic of a minority hexa-coordinate aquo-ferric form. The signals are very similar to those reported for P450scc isolated from bovine adrenocortical mitochondria.25,26 The presence of a coordinated water in the low-spin conformer of the complex is confirmed by 1H ENDOR spectra, which exhibit a signal from exchangeable proton(s) of the bound water, with maximum hyperfine coupling A ≅ 8.5 MHz lying along g1 (Fig S3), as seen in other aquo-ferric heme complexes.24 The appearance of a low-spin spin state at low temperature was observed for other substrate bound ferri cytochromes P450cam.27

Table 1.

g-tensor components for Fe(III) P450scc complexes

| Substrate | species | g1 | g2 | g3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH | ls | 2.43 | 2.25 | 1.917 |

| hs | 8.09 | 3.59 | 1.69 | |

| 22-HC | major | 2.467 | 2.255 | 1.908 |

| l minor | 2.443 | 2.255 | 1.917 | |

| 20-HC | 2.41 | 2.246 | 1.924 |

The binary complex of 22-HC with Fe(III)P450scc shows low-spin EPR signals, from two conformational sub-states, with g(1) = [2.467, 2.255, 1.908] (major, ~ 75% of total protein) and g(2) = [2.443,2.255 and 1.917] (minor) (Table 1, Fig S2), in agreement with a previous report.25 The major signal may be assigned to a state with 22-HC-bound to the ferric heme through the hydroxyl group; the minor signal may be a second conformer of bound 22-HC, but also could be the aquo-ferric heme form. Interestingly, the relative intensities of the signals are found to change in deuterated solvent (not shown). The crystal structure for the complex of ferric P450scc with 22-HC (Fig 1) 14,15 shows the 22R-hydroxyl located in close proximity to the heme iron, with a reported distance of ~2.6 A, suggesting formation of coordination bond as indicated by EPR for the majority low-spin form.

The 2D field-frequency pattern of 1H ENDOR signals collected across the EPR envelope of the low-spin EPR signal of the complex with 22-HC is considerably different and better resolved (Fig S4) as compared to that for complex ferric P450scc-CH (Fig S3). The spectrum collected at the field that corresponds to g1 for the majority conformation shows two resolved 1H ENDOR signals, with Amax = 4.8 and 8.3 MHz. The latter disappears in deuterated solvent, and is assigned to the iron-coordinated 22R hydroxyl proton; the non-exchangeable signal with A = 4.8MHz is assigned to the 1H atom of substrate closest to the Fe(III), one at either the C-22 or C20 positions.28

In agreement with a previous report,25 the other possible product of the hydroxylation of cholesterol, 20-HC, forms only a single low-spin complex with P450scc, with g = [2.416, 2.248, 1.924] (Table 1, Fig S2). The crystal structure for this complex reveals that the 20-hydroxyl is positioned away from the heme iron (distance 3.7 A) and is hydrogen bonded to a water molecule coordinated to the heme iron.14 Correspondingly, the 1H ENDOR pattern for this water ligand is similar, although not identical, to that for Fe(III)-coordinated water of ferric P450scc in the presence of cholesterol (Fig S5).

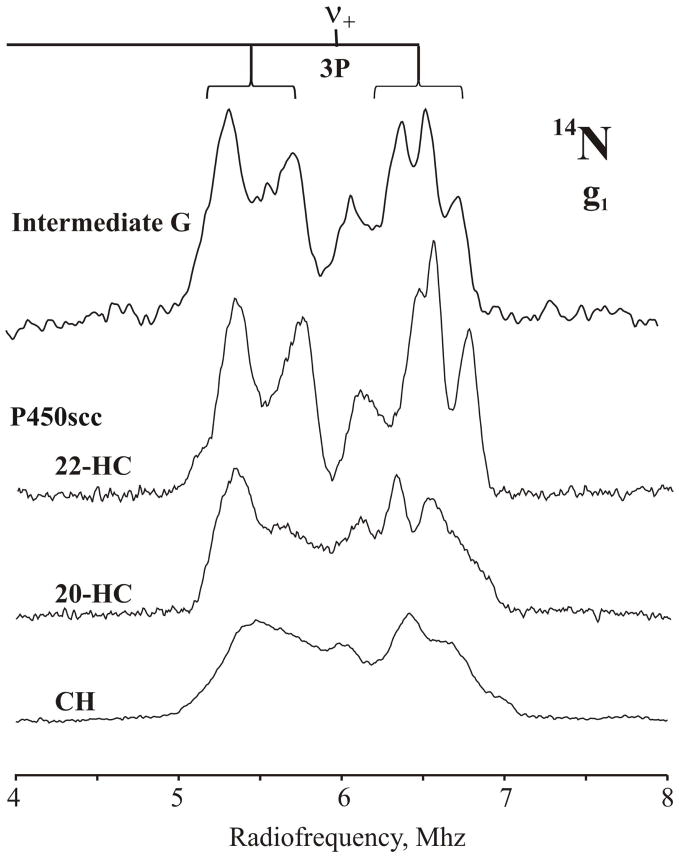

Figure 2 shows the 14N ENDOR spectra of the pyrrole nitrogens of the majority complex of ferric P450scc with CH, 22-HC, and 20-HC, and intermediate G (see below). The signals represent the quadrupole-split (3P), ν+ = A/2 + νN branch of the 14N response. We specifically note that the pyrrole 14N ENDOR spectra are distinctly sharpened when H2O bound to the ferriheme of the CH and 20-HC complexes is replaced by the 22R-hydroxyl of 22-HC, indicating a more sharply defined structure in this latter complex (Fig 2). The signals show overlapping responses from what appear to be four similar, but distinguishable 14N ligands, indicating a complete symmetry lowering of the heme iron coordination environment in this complex. We consider as being less likely the alternative interpretation, that the multiplicity of signals come from relatively symmetric heme in multiple conformational sub-states, because the cholesterol and 20-HC complexes show only a single sub-state in their low-spin EPR spectra (Fig S2), and the 22-HC complex, which shows two substates in the EPR spectrum, is interrogated at a field where only the dominant sub-state contributes. The average hyperfine couplings and quadrupole splittings in all cases are A(g1) ~ 6 MHz and 3P(g1) ~ 2 MHz.

Fig 2.

14N 35 GHz CW ENDOR spectrum (ν+ -branch) of the complexes of ferri P450scc with cholesterol, 22-CH and 20-CH and the intermediate G, taken at respective g1. Conditions: 2K, 2G, rf sweep rate = 0.2MH/s, bandwidth broadening 20kHz.

Cryoreduced ternary complex oxy P450scc-cholesterol

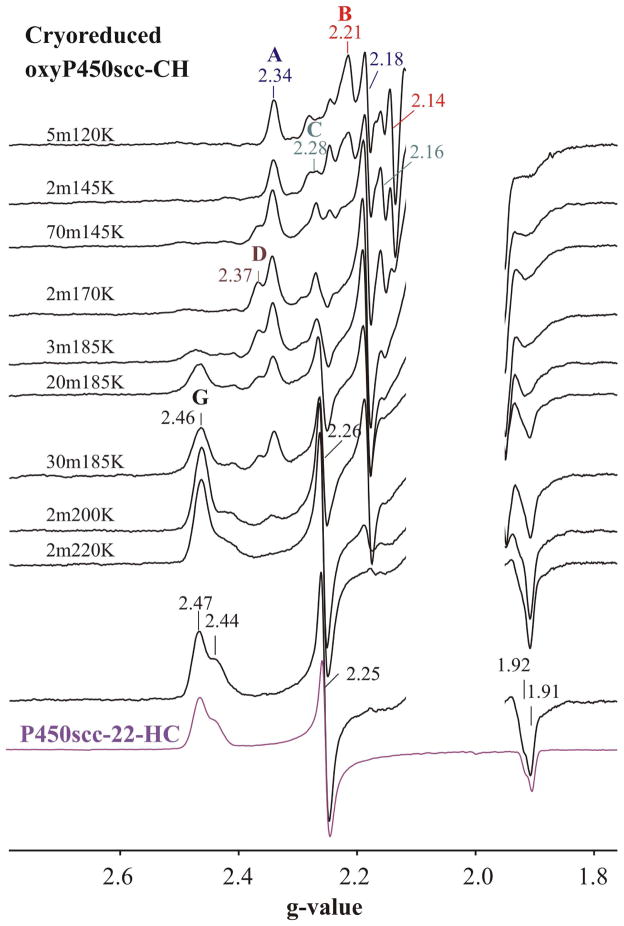

Figure 3 presents EPR spectra of the oxy-P450scc-CH ternary complex after exposure to γ-irradiation at 77K and annealing the cryogenerated intermediate at indicated temperatures between 145 and 220K. The spectrum of the cryoreduced complex trapped at 77K displays three distinct EPR signals. The main signal A, which accounts for approximately 70 % of the reduced oxy-ferro heme centers (Fig S6), has g = [2.34, 2.18, 1.95](Table 2), characteristic of hydroperoxo-ferriheme intermediate.8,28–30 The intermediate exhibits a resolved proton ENDOR signal with Amax~10 MHz that disappears in deuterated solvent and is assignable to the proton of the hydroperoxo ligand (Fig 4).28,29

Fig 3.

EPR spectra of cryoreduced oxy P450scc-CH ternary complex and after annealing steps at indicated temperatures. (For clarity the EPR signal from residual low-spin ferric P450scc available in the spectra was subtracted and radiolytically induced radical signal was omitted). For comparison in the bottom of the Figure EPR spectrum of the complex of ferri P450scc with 22-CH is presented. Conditions: T=25K, 9.360 GHz, 13W, 10G.

Table 2.

g-values for 77 K cryoreduced oxy-P450scc-CH Complex and the Intermediates arising during its annealing

| Species | Tan(K) | g1 | g2 | g3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (major) | 77K | 2.34 | 2.182 | 1.949 |

| B(minor) | 77K | 2.214 | 2.14 | nd |

| C(minor) | 77K | 2.28 | 2.156 | nd |

| D | 170K | 2.366 | 2.182 | 1.95 |

| G | 185K | 2.463 | 2.257 | 1.908 |

| E(major) | 220K | 2.447 | 2.254 | 1.907 |

| E(minor) | 220K | 2.443 | 2.254 | 1.918 |

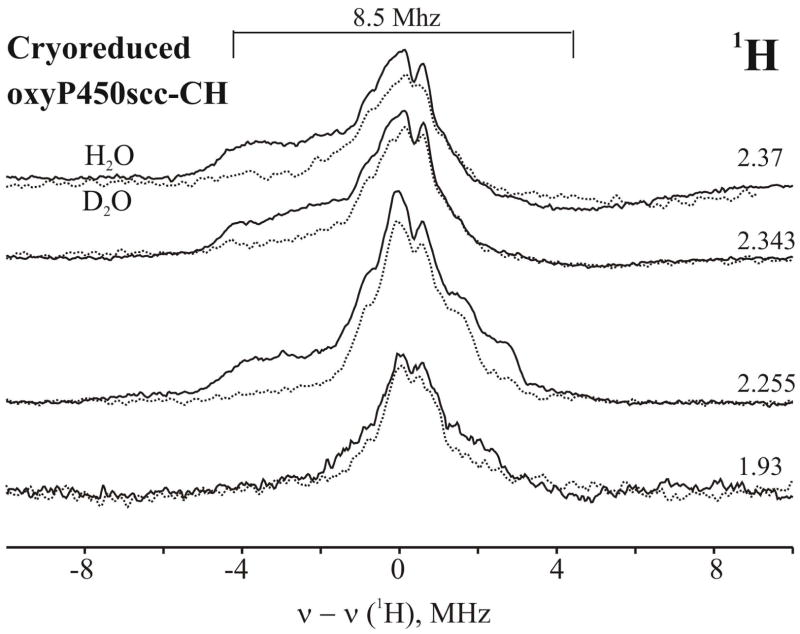

Fig 4.

1H 35 GHz CW ENDOR spectra taken at indicated g-values of the cryoreduced oxy-P450scc-CH in 35% glycerol/H2O buffer(pH 7.4) (solid line) and 35% d3-glycerol/D2O buffer (pH 7.0) (dotted line) annealed at 170K for 2 min. Conditions: T=2K, 2G, rf sweep rate = 1Mhz/s, bandwidth broadening = 60kHz, 30scans.

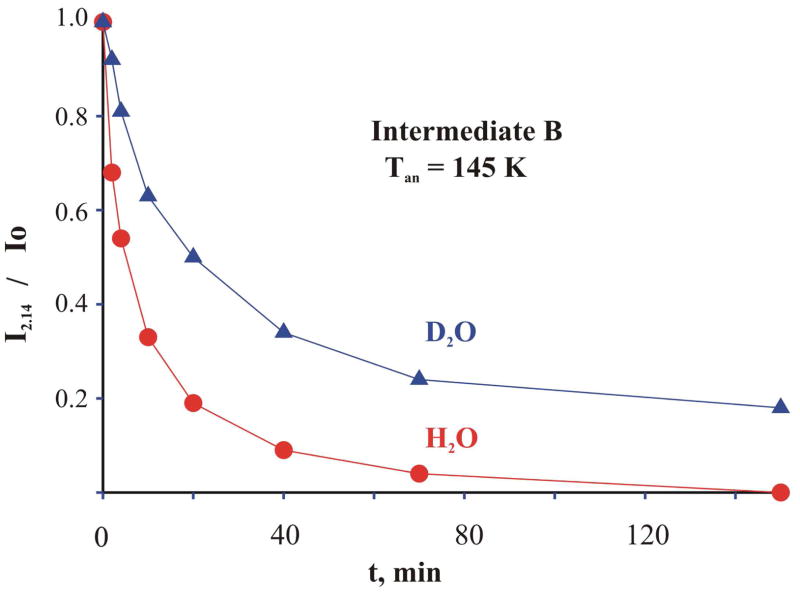

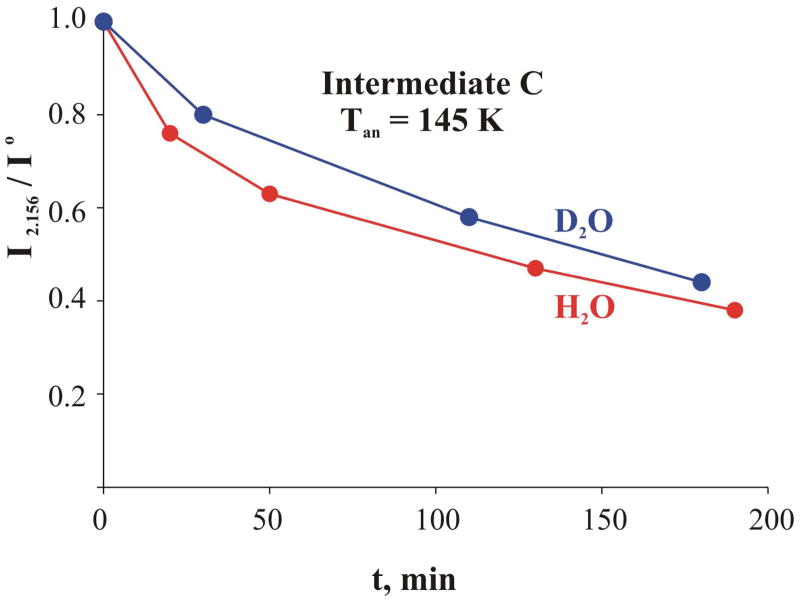

Two minor signals, B and C, are characterized by g-values of 2.214, 2.14, and 2.28, 2.156, respectively (Table 2). The g-values for B are typical of a peroxo-ferriheme intermediate,8,28,31 while as shown below C is probably in the hydroperoxo-ferriheme state.28,29 The observation of hydroperoxo-ferriheme state A as the main product of 77K cryoreduction indicates that in the majority of the ternary oxy complex conformers that are the precursors to A, a hydrogen bonding network tied to the precursor dioxygen ligand supports proton delivery, even at 77K.8,28–30,32 This was shown previously to imply the presence of an ordered water molecule in the vicinity of the distal oxygen of the O2 ligand, as in the case of oxy-P450cam and oxy-heme oxygenase.16,17,28,29 The majority hydroperoxo species, A, is stable during progressive annealing of the cryoreduced ternary cholesterol complex at temperatures from 145K to170 K. In contrast, during annealing at 145 K the peroxo-ferric intermediate B decays (Fig 3) in a fashion that can be described by a ‘stretched exponential, as is often the case,33 and the decay slows by a factor of over five in D2O/d3-glycerol mixture (Fig 5). This significant solvent kinetic isotope effect (sKIE) indicates that the rate-limiting step involves protonation of the peroxo ligand. Intermediate C also decays at 145 K but this process shows only a weak sKIE < 1.5 (Fig 6), suggesting proton-independent structural changes in the active site of intermediate C during the relaxation. It appears that B and C both converted to a new species, D, during their decay. The g-values of D (Table 2), (g = [2.37, 2.18, 1.94,) are characteristic of a hydroperoxy-ferriheme species, but with a slightly different environment than that of A (Fig 3, Table 2).

Fig 5.

Kinetics of decay of the cryogenerated peroxo-ferriheme species B at 145 K in H2O (red) and D2O (blue) buffers at 145K.

Fig 6.

Kinetics of the decay of the intermediate C at 145 K in H2O (red) and D2O (blue) at 145K.

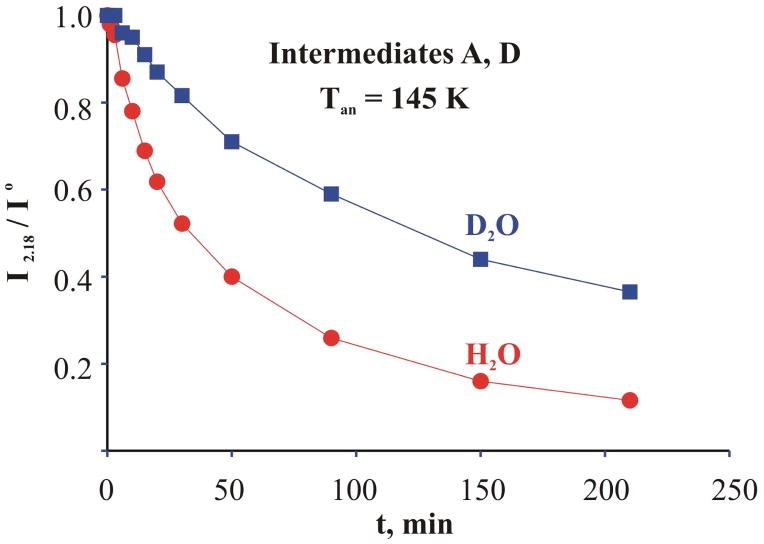

The hydroperoxo-ferric states A and D decay in parallel at 185K (Fig 3). The data presented in Fig 7 show that this relaxation is characterized by a solvent kinetic isotope effect, sKIE of ≥ 4. This behavior is expected if Cpd I is the active heme state. Heterolytic cleavage of the ferriheme hydroperoxy ligand to form the Compound I, ferryl porpyrin π-cation radical, intermediate requires protonation of the distal hydroperoxy oxygen, and accordingly is expected to show a significant sKIE when protonation is the rate limiting step, as observed here (Fig 7).

Fig 7.

Kinetics of decays of hydroperoxy ferric intermediates A and D in H2O (red) and D2O (blue) at 185K.

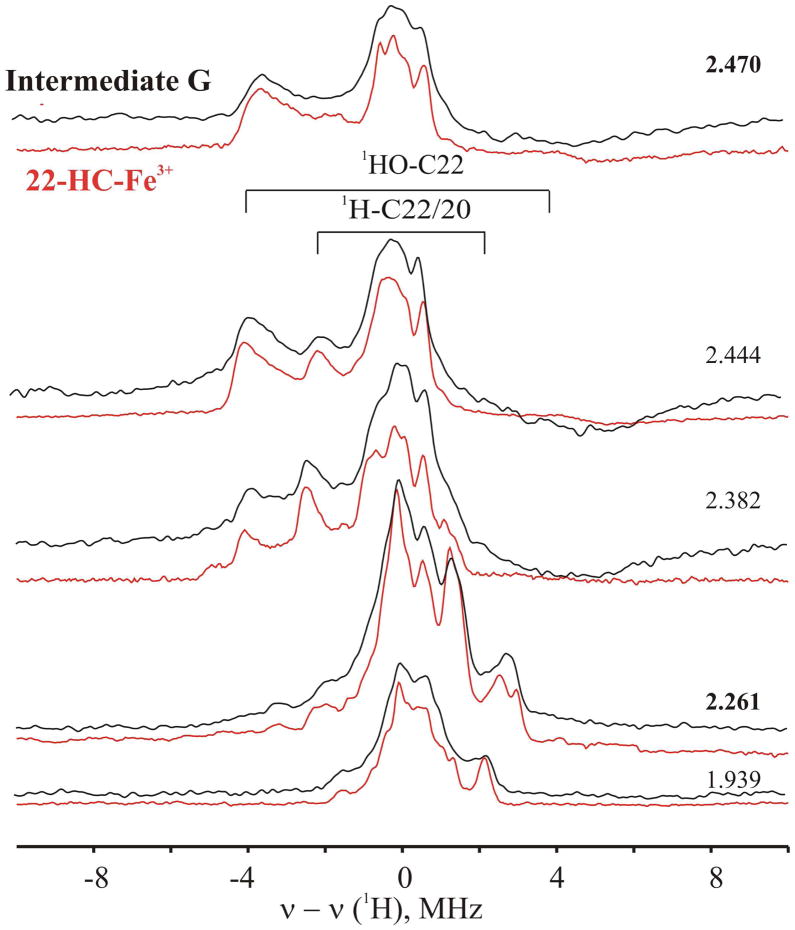

The loss of the hydroperoxo species is accompanied by the formation of a new species G which has two sub-states, the dominant one with g-values g = [2.463, 2.257, 1.908]. The g-values of the two sub-states are the same as those of the EPR spectrum of the complex of ferric P450scc with 22-HC (Fig 3, Table 1). The only meaningful difference between the two spectra is in the relative proportions of the two sub-states: the primary product G forming after decay of the ferric hydroperoxo intermediates at 185K contains relatively small amounts of the second conformer showing EPR signal with g = [2.44,2.25,1.92]. Thus we infer that cholesterol has been hydroxylated during the annealing process and that species G is the product complex between ferric P450scc and 22-HC.

This assignment of intermediate G to the primary product complex is confirmed by the 1H and 14N ENDOR spectra for the G intermediate. As shown in Fig 8 the 1H ENDOR spectrum of the dominant G sub-state is essentially the same as that obtained from the majority EPR signal of the 22-HC–ferric P450scc complex, with the same two resolved 1H ENDOR signals, (Amax = 4.8 and ~ 8 MHz) (Fig S4). Likewise, the 14N ENDOR spectra of the majority conformers of G and of the 22-HC–ferric P450scc complex are the same, and differ from that of the aquo-ferriheme complex in the presence of cholesterol Fig 2.

Fig 8.

1H 35 GHz CW ENDOR spectra taken at indicated g-values for the intermediate G (1m200K) (black) and the complex of P450scc-22CH (red). Conditions: as in Fig 2.

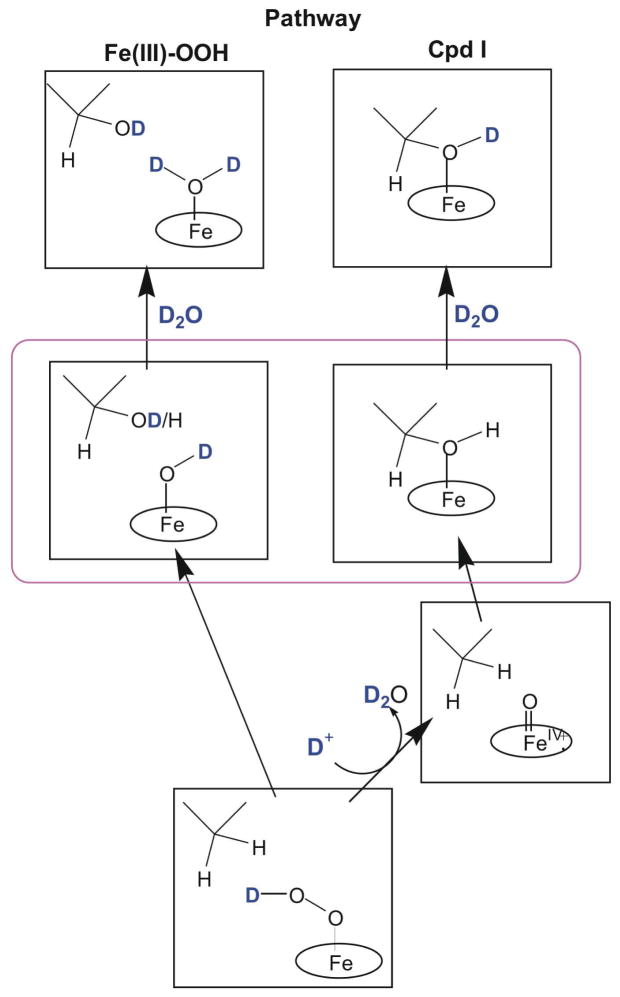

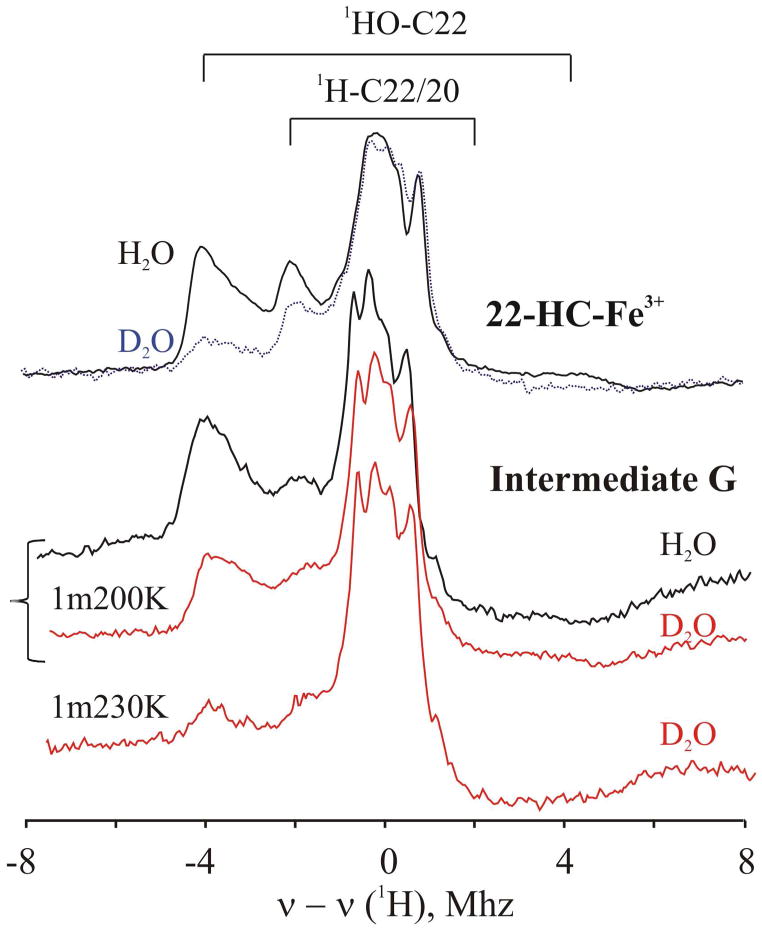

As illustrated in Figure 9, characterization of the coordination sphere of the ferriheme in the primary product, G, by ENDOR spectroscopy distinguishes between alternative active species, hydroperoxo-ferric or Cpd I. Insertion of an oxygen atom into cholesterol by the ferryl ion of Compound I should generate 22R-OH with its hydroxyl group bound to Fe(III). Moreover, the hydroxyl proton should be a 1H that originates from a 22C-H of substrate, even if the reaction proceeds in D2O buffer. In contrast, if the hydroperoxo-ferric heme intermediate is the hydroxylating species, the initial product state formed in D2O buffer should contain DxO bound to Fe, with the D derived from solvent.8 In the ENDOR measurements on G, the 1H signal with the larger coupling, which is associated with the heme-bound 22R-hydroxyl of 22-HC, is largely preserved when G is generated in D2O buffer, Fig 10. This is as predicted when Cpd I is the hydroxylating agent (Fig 9) and previously found for P450cam.28 These observations thus confirm that Cpd I is indeed the active species in hydroxylation of cholesterol to form the 22-HC product.

Figure 9.

Schematic view of the reaction via the two alternative active-oxygen species as carried out in D2O buffer.

Fig 10.

(A) 1H 35 GHz CW ENDOR spectra of the complex of Fe(III)P450scc with 22-HC taken at g1 = 2.44 in H2O (solid) and D2O (dotted). (B) 1H 35 GHz CW ENDOR spectra of the primary product G taken at g1 = 2.46 in H2O (black) and D2O (orange) trapped after annealing at 200K for 1 min and at 230K for 1min. Conditions: as in Fig 2.

During annealing at 220–240K, intermediate G relaxes to the product complex in its equilibrium state, the only change being a decrease in the low-spin ferri-heme substate with g1 = 2.46–2.47 and an increase in the substate with g1 = 2.44 and, yielding an EPR spectrum that is the same as that seen for the complex prepared by adding 22-HC to P450scc (Fig 3). Correspondingly, during relaxation of G to the equilibrium state at 230K the 22R-hydroxyl proton signal disappears as exchange with D2O solvent is enabled, but the signal assigned to the 1H at either the C-22 or C20 positions of 22R remains (Fig 10). Taken together, the kinetic (Fig 7), EPR (Fig 3), and ENDOR (Figs 8, 10) observations strongly support the conclusion that Compound I is the active hydroxylating species in P450scc catalytic conversion of cholesterol into the 22-HC.

Interestingly, during annealing of the cryoreduced complex with cholesterol no product complex is detected that has the g-values of the complex between P450scc and 20-HC. This observation is in agreement with the fact that the latter is only a minor product during metabolism of cholesterol under physiological condition. 1,3

Discussion

This study provides new information about the structure of the oxy-heme center in the ternary oxy-P450scc-cholesterol complex and about the mechanism of the first step in the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone catalyzed by P450scc, the hydroxylation of cholesterol to 22-HC.

Structure of the oxy-heme Center

Cryoreduction of the oxy-P450scc-substrate complex at 77K generates EPR-active states that retain the conformation of the oxy-precursor8,23,24,28–33 and thus provides a sensitive EPR/ENDOR probe of the diamagnetic oxy-ferrous precursor. The data presented here show that the ternary oxy-P450-cholesterol complex exists in at least three different conformational sub-states that form spectroscopically distinct intermediates A, B and C upon 77 K reduction (Fig 3, Table 2). EPR spectra show that the main products of radiolytic cryoreduction, species A and C, are distinct sub-states of the hydroperoxy-ferriheme state, with peroxo-ferriheme intermediate B a minor trapped product. As in situ cryoreduction of an oxy-heme must first form the peroxo-ferriheme species, the majority of cryoreduced oxy-heme conformers thus must undergo proton transfer at 77K to form the observed A and C states.8,34 Previous cryoreduction studies with a variety of oxy-hemoproteins, including cytochromes P450,28,30,33 NOS,23 heme oxygenase,29,35 IDO/TDO32 and oxy-globins24,31,34,36 showed that such proton transfer to the basic peroxo-ligand trapped at 77K or below requires the presence in the parent oxy-hemoprotein of a hydrogen-bonded proton delivery network that includes an ordered water molecule in the active site that is hydrogen bonded to the terminal oxygen of the bound dioxygen ligand. This water serves as the proton shuttle to the peroxide ligand generated by cryoreduction at 77K or below.35,37–40 The transferred proton can originate from acid/base groups provided by amino acid residues within the active site,28,29,35 from bound substrate,23 or from water clusters connected to the active site by a proton delivery network.41,42 Perturbation of this network in P450cam by site specific mutation inhibits this proton delivery and inhibits conversion of cryogenerated peroxo to hydroperoxo species.28 The nature of the substrate bound to P450cam was further shown to significantly modulate proton delivery, and thereby lengthen the lifetime of the peroxo intermediate during annealing measurements.33

In case of gsNOS, bound NOHA stabilizes the enzymatically active, cryogenerated peroxo-ferriheme intermediate, whereas in the presence of Arg only the hydroperoxo species is formed at temperatures below 77K.23 Bound substrate was also shown to effectively inhibit protonation of the peroxo ligand in cryoreduced oxy-IDO and TDO.24 Correspondingly, cryoreduction of oxy-globins, which do not have such a bound water, exclusively generates peroxo-ferric intermediates. In all cryogenerated peroxo-intermediates of hemoproteins studied to date, the peroxo ligand forms an H-bond with a nearby amino acid residue (for instance, distal His in case of globins31,36) or bound substrate.23,32 In the absence of such H-bonding interactions, a superoxy-ferrous species is trapped as the product of 77K cryoreduction.34 The peroxo-ligand becomes protonated only at higher temperatures (for example, above 170K in the oxy-globins),36 at which a molecule of water might diffuse to the distal oxygen of the peroxo-ligand.32,36

Overall, comparison with previous measurements on numerous proteins thus indicates that the ternary oxy-P450scc-cholesterol complex contains an active-site water molecule that H-bonds to the terminal oxygen of the dioxygen ligand. This situation resembles that shown crystallographically for the oxy-P450cam-camphor complex, in which binding of dioxygen to the ferrous heme leads to incorporation of a water molecule that forms an H-bond to the distal oxygen of O2,16 and provides effective delivery of the first proton for monooxygenation at temperatures below 77K.28. The observation of the minor peroxo-intermediate B along with the majority hydroperoxo-products of cryoreduction indicates the additional presence of minority conformers of the ternary complex in which the H-bonding network to dioxygen is disrupted. However, the fact that protonation of the peroxo- ligand nonetheless still occurs at the relatively low temperature of 120–145K, where long-distance diffusion of a molecule water to the cryogenerated peroxo ligand is strongly hindered, suggests that these conformers likewise have a molecule of water incorporated in the vicinity of the dioxygen ligand, but that some minimal reorientation of this water is required to establish the required pathway for proton transfer.

Hydroxylation of Cholesterol

As with other monooxygenases8 the cryoreduction approach to studying the hydroxylation of substrate by P450scc, is fully validated by (i) the demonstration that the cryoreduced ternary complex of oxy-P450scc-CH is catalytically competent and hydroxylates cholesterol to form 22R-HC, and (ii) the absence of detectable formation of 20-HC, consistent with catalysis under physiological conditions,. Controlled annealing of the cryogenerated hydroperoxo-ferriheme intermediates A, C, enables a detailed examination of successive steps in cholesterol hydroxylation by EPR and ENDOR spectroscopy.

The initial intermediates formed by 77K cryoreduction of the ternary oxy-P450scc– substrate complex, A, B, C, relax to the two low-spin hydroperoxy-ferriheme species A and D (Table 2) upon annealing at 145–170K. (Table 2) The existence of spectroscopic differences between species A, D indicates the presence of heterogeneity within the hydroperoxy-ferriheme site that likely reflects the corresponding heterogeneity of the oxy-heme structure. Further annealing at 185K results in full conversion of both intermediates A and D into the primary product of hydroxylation, species G, which again exists in two sub-states. Both exhibit the same g tensors as the two sub-states of the equilibrium complex of ferric P450scc with 22-HC (Fig 3, Table 1) in which 22R-OH group is coordinated to the heme iron (III) at the distal axial position,14,15 with G differing only in the relative proportions of the two sub-states (Fig 3).

Species A and D decay in parallel with a large solvent isotope effect, effective sKIE ≥ 4, which indicates that the rate limiting step in this process is the proton-assisted reaction of hydroperoxo-intermediate, as expected for conversion to Compound I. The structure and isotopic composition of the primary product of hydroxylation trapped during progressive annealing, as determined by ENDOR spectroscopy, confirms that Compound I is indeed the catalytically active heme species.

Previous studies of P450cam and gsNOS8,23,28,33 showed that the newly formed hydroxyl group of the hydroxylated product is coordinated to the ferric heme iron in the non-equilibrium primary product state when the ferryl moiety of Cpd I is the active species. In contrast, hydroxylation of substrate by peroxo-/hydroperoxo- moiety involves an concerted insertion of the distal peroxy/hydroperoxy oxygen into substrate, and would generate a primary product state with a hexa-coordinate ferric-heme moiety with water/hydroxide as the sixth axial ligand.8 This scenario describes heme hydroxylation by cryoreduced oxy-HO.29

With this foundation, the 1H ENDOR data collected from the primary product of hydroxylation, G, formed during annealing at 200K in deuterated solvent, (Fig 10) establishes that Cpd I is the hydroxylating agent. The insertion of oxygen into cholesterol the C22-H bond by the ferryl moiety of enzyme in deuterated solvent must yield 22-HC, C22-OH as product, rather than 22-HC C22-OD, which would be the product if deuterated hydroperoxy-intermediate (FeOOD) were the active species (Fig 9). In fact, the primary product G formed with the enzyme in a D2O/d3-glycerol mixture shows a strong 1H ENDOR signal from the coordinated hydroxyl of 22-HC, and that this exchanges for D during annealing at higher temperatures. This is precisely as expected (Fig 9) if the ferryl oxygen inserted in the C-H bond of substrate (Fig 10). Failure to detect Cpd I by EPR during this process can be accounted for by a high rate of reaction with bound substrate, which prevents its accumulation.

In the final stage of annealing G the non-equilibrium proportions of the two conformations of 22-HC coordinated to heme iron (III) relax to the equilibrium proportions upon annealing at 240K (Fig 3).

In this picture, the hydroperoxo-ferriheme intermediate undergoes the key O-O bond-breaking reaction. Comparison of the spin-Hamiltonian parameters for the hydroperoxo-ferriheme as generated in different proteins/enzymes thus affords an opportunity to consider the properties of this state that control O-O bond breaking. As discussed earlier, the peroxo- and hydroperoxo-ferrihemes exhibit low-spin ferriheme EPR spectra that are distinguished by g1: g1 < 2.27 for peroxo; g1 ≥ 2.28 for hydroperoxo. As shown in Table S1, the range of values observed to date for hydroperoxo-ferrihemes, 2.28 ≤ g1 ≤ 2.37 is essentially the same for proteins with proximal histidyl and cysteinyl ligands, suggesting that the proximal ligand plays essentially no role in determining the ground state electronic structure of this species, unlike the case of the aquaferriheme form.

The values of g1 for heme oxygenase, for which the active-oxygen species is the hydroperoxo-ferriheme, and for P450scc-CH, for which Cpd I is the active-oxygen species, are essentially the same, suggesting that the ground state electronic structure of the Fe-OOH moiety plays little role in determining the fate of this state, and hence the ultimate active-oxygen species. This supports the suggestion that the fate of the Fe-OOH is determined by a kinetic competition between heterolytic bond cleavage to form Cpd I, versus direct reaction with substrate (substrate modulation of reactivity),33 as influenced by the properties of the heme pocket.8

Summary

Cryoreduction/annealing experiments in combination with EPR/ENDOR spectroscopy have demonstrated that Compound I is the reactive species during P450scc catalyzed hydroxylation of CH to 22-HC. The cryoreduction experiments further indicate the presence of the proton delivery network which includes an ordered water molecule that is H-bonded to the distal oxygen of the dioxygen ligand in the ternary oxy-P450scc-CH complex, and which provides efficient proton transfer to the one electron reduced oxy-heme site.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH for support (HL13531, B.M.H.) and Prof. H. Halpern, Pritzker School of Medicine, University of Chicago, for access to the 60Co Gamma cell irradiator.

Abbreviations

- P450scc

cytochrome CYP11A1

- CH

cholesterol

- 22-HC

22R-hydroxycholesterol

- 20HC

20α-hydroxycholesterol

- 20α

22R-dihydroxycholesterol, 20,22-DHC

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Includes one scheme and six EPR and ENDOR figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bernhardt R, Waterman MR. In: Met Ions Life Sci. Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK, editors. Vol. 3. John Wiley and Sons; 2007. p. 361. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilep AA, Sushko TA, Usanov SA. Biochim Biophys Acta, Proteins Proteomics. 2011;1814:200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuckey RC. Placenta. 2005;26:273. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Montellano PRO, De Voss JJ. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:477. doi: 10.1039/b101297p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denisov IG, Makris TM, Sligar SG, Schlichting I. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2253. doi: 10.1021/cr0307143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hlavica P. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:4335. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhtar M, Njar VCO, Wright JN. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;44:375. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90241-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davydov R, Hoffman BM. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;507:36. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gantt SL, Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, Sligar SG. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;387:169. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kellner DG, Hung SC, Weiss KE, Sligar SG. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100745200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spolitak T, Funhoff EG, Ballou DP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;493:184. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rittle J, Green MT. Science. 2010;330:933. doi: 10.1126/science.1193478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strushkevich N, MacKenzie F, Cherkesova T, Grabovec I, Usanov S, Park HW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019441108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mast N, Annalora AJ, Lodowski DT, Palczewski K, Stout CD, Pikuleva IA. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:5607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.188433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlichting I, Berendzen J, Chu K, Stock AM, Maves SA, Benson DE, Sweet BM, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Sligar SG. Science. 2000;287:1615. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsui T, Unno M, Ikeda-Saito M. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:240. doi: 10.1021/ar9001685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuehnel K, Derat E, Terner J, Shaik S, Schlichting I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:99. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606285103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lepesheva GI, Usanov SA. Biochemistry (Moscow) 1998;63:224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lepesheva GI, Strushkevich NV, Usanov SA. Biochim Biophys Acta, Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 1999;1434:31. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glasoe PK, Long FA. J Phys Chem. 1960;64:188. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuckey RC, Kamin H. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:9309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davydov R, Sudhamsu J, Lees NS, Crane BR, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14493. doi: 10.1021/ja906133h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davydov R, Osborne R, Shanmugam M, Du J, Dawson J, Hoffman B. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14995. doi: 10.1021/ja1059747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orme-Johnson NR, Light DR, White-Stevens RW, Orme-Johnson WH. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeuchi K, Tsubaki M, Futagawa J, Masuya F, Hori H. J Biochem. 2001;130:789. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipscomb JD. Biochemistry. 1980;19:3590. doi: 10.1021/bi00556a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davydov R, Makris TM, Kofman V, Werst DW, Sligar SG, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1403. doi: 10.1021/ja003583l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davydov R, Kofman V, Fujii H, Yoshida T, Ikeda-Saito M, Hoffman B. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1798. doi: 10.1021/ja0122391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davydov R, Razeghifard R, Im SC, Waskell L, Hoffman BM. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9661. doi: 10.1021/bi800926x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davydov R, Kofman V, Nocek J, Noble RW, Hui H, Hoffman BM. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6330. doi: 10.1021/bi036273z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davydov RM, Chauhan N, Thackray SJ, Anderson JLR, Papadopoulou ND, Mowat CG, Chapman SK, Raven EL, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5494. doi: 10.1021/ja100518z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davydov R, Perera R, Jin S, Yang TC, Bryson TA, Sono M, Dawson JH, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1403. doi: 10.1021/ja045351i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davydov R, Satterlee JD, Fujii H, Sauer-Masarwa A, Busch DH, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:16340. doi: 10.1021/ja037037e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davydov R, Chemerisov S, Werst DE, Rajh T, Matsui T, Ikeda-Saito M, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15960. doi: 10.1021/ja044646t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kappl R, Hohn-Berlage M, Huttermann J, Bartlett N, Symons MCR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;827:327. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar D, Hirao H, De VSP, Zheng J, Wang D, Thiel W, Shaik S. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:19946. doi: 10.1021/jp054754h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vidossich P, Fiorin G, Alfonso-Prieto M, Derat E, Shaik S, Rovira C. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:5161. doi: 10.1021/jp911170b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Igarashi J, Jamal J, Yang W, Poulos TL. JBIC, J Biol Inorg Chem. 2006;11:753. doi: 10.1007/s00775-006-0123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho KB, Derat E, Shaik S. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3182. doi: 10.1021/ja066662r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guallar V, Harris DL, Batista VS, Miller WH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1430. doi: 10.1021/ja016474v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonin J, Costentin C, Louault C, Robert M, Saveant JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:6668. doi: 10.1021/ja110935c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.