Abstract

The health disparities literature identified a common pattern among middle-aged African Americans that includes high rates of chronic disease along with low rates of psychiatric disorders despite exposure to high levels of cumulative SES risk. The current study was designed to test hypotheses about the developmental precursors to this pattern. Hypotheses were tested with a representative sample of 443 African American youths living in the rural South. Cumulative SES risk and protective processes were assessed at 11-13 years; psychological adjustment was assessed at ages 14-18 years; genotyping at the 5-HTTLPR was conducted at age 16 years; and allostatic load (AL) was assessed at age 19 years. A Latent Profile Analysis identified 5 profiles that evinced distinct patterns of SES risk, AL, and psychological adjustment, with 2 relatively large profiles designated as focal profiles: a physical health vulnerability profile characterized by high SES risk/high AL/low adjustment problems, and a resilient profile characterized by high SES risk/low AL/low adjustment problems. The physical health vulnerability profile mirrored the pattern found in the adult health disparities literature. Multinomial logistic regression analyses indicated that carrying an s allele at the 5-HTTLPR and receiving less peer support distinguished the physical health vulnerability profile from the resilient profile. Protective parenting and planful self-regulation distinguished both focal profiles from the other 3 profiles. The results suggest the public health importance of preventive interventions that enhance coping and reduce the effects of stress across childhood and adolescence.

Keywords: adjustment, allostatic load, genetics, health, stress

Socioeconomic Status Risk, Allostatic Load, and Adjustment

A Prospective Latent Profile Analysis With Contextual and Genetic Protective Factors The well-documented health disparities between African Americans and members of other ethnic groups do not originate in adulthood, but result from changes in biological processes at earlier stages of development (Geronimus, Hicken, Keene, & Bound, 2006). This may be particularly true for African American youths living in the rural South, who have a distinct profile of characteristics. Risk factors include the chronic poverty and limitations in occupational and educational opportunities endemic to these localities, frequent housing adjustments in response to economic pressures, changing employment status, interpersonal and institutional racism, difficulty in accessing medical care, and marginalization by health care professionals (Dressler, Oths, & Gravlee, 2005). Living in such challenging contexts can have deleterious effects on the functioning of biological stress regulatory systems across the lifespan and, ultimately, on health and psychological well-being (Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009).

Recent research suggests that coping with cumulative SES-related stressors elicits a cascade of biological responses that are functional in the short term but over time may “weather” or damage the systems that regulate the body’s stress response. The concept of allostatic load (AL), a marker of chronic physiological stress and cumulative wear and tear on the body, illustrates the disease-promoting potential of continuous adjustment to stress (McEwen, 2002; Sterling & Eyer, 1988). AL is indexed by elevated physiological activity across multiple systems, including the sympathetic adrenomedullary system (SAM), the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, lipid metabolism, fat deposition, indices of inflammation, and immune functioning (McEwen, 2000; Seeman, McEwen, Rowe, & Singer, 2001). If coping demands are elevated or prolonged, the body mobilizes resources more actively than during less demanding periods. The bodies of individuals with high AL, however, become less efficient at turning off the multiple physiological resources marshaled to deal with chronic demands, even during periods of relative calm. This inability to turn off the demand response sets in motion a cascade of physiological changes that contribute to the development of chronic illnesses, including hypertension, cardiac disease, diabetes, stroke, and psychiatric disorders (Seeman et al., 2001). Despite the pivotal role that AL may play in the development of chronic diseases and health disparities (see Shonkoff et al., 2009), no prospective studies have focused on AL and its antecedents among African American adolescents living in either rural or urban contexts. The present study was designed to help fill this need.

The specific purpose of this study was to address the developmental precursors of a consistent, yet counterintuitive, set of findings in the adult health disparities literature. This literature indicates that African American adults experience greater physical morbidity and mortality across the life span. For example, African American adults are twice as likely as European Americans to die of heart disease, cancer, and diabetes (Lantz et al., 2001; Mensah, Mokdad, Ford, Greenlund, & Croft, 2005). Conversely, findings from epidemiologic surveys consistently indicate that African American adults report equal or lower rates of lifetime mental disorders than do European American adults, even with exposure to cumulative SES risks controlled (Breslau, Kendler, Su, Aguilar-Gaxiola, & Kessler, 2005; Kessler et al., 2005; Riolo, Nguyen, Greden, & King, 2005). Researchers have sought explanations for this counterintuitive pattern. One potential explanation involves misreporting bias (Breslau, Javaras, Blacker, Murphy, & Normand, 2008); however, validation studies have indicated that survey assessments perform with equal accuracy for African Americans and European Americans. The consistency of this finding across different instruments and study populations casts doubt on this explanation (D. R. Williams et al., 2007). It has also been suggested that African Americans have greater access to positive coping resources (e.g., social support) and make greater use of them than do European Americans, but such explanations currently are more theoretical than empirical (S. Schwartz & Meyer, 2010). Thus, the discrepancy between physical and mental health outcomes among African Americans, as well as their developmental origins, remain unexplained.

We propose that the counterintuitive pattern described in the health disparities literature will be foreshadowed during adolescence. We predict that AL and psychological functioning assessments will reveal a pattern that will include exposure to high levels of cumulative SES risk, high AL, and low levels of adjustment problems among a sizable group of rural African American youths. We refer to this pattern as a physical health vulnerability profile. The resilience literature, however, indicates that youths respond to contextual challenges in markedly different ways that are linked to contextual and genetic factors (Cicchetti, Rogosch, Gunnar, & Toth, 2010). Accordingly, we expect additional patterns to emerge. Some youths exposed to high levels of cumulative SES risk will struggle and evince high AL with low behavioral and emotional functioning, a physical and mental health vulnerability profile. Others will adapt remarkably well, exhibiting low AL with high levels of behavioral and emotional competence— a resilient profile—whereas others who are not exposed to high cumulative SES risk will evince low AL with high levels of behavioral and emotional functioning, a low risk profile. Thus, the present study was designed to (a) identify, through confirmatory latent profile analysis, groups of rural African American youths who evince distinct patterns of exposure to cumulative SES risk, AL, and psychological adjustment, and (b) identify, through multinomial logistic regression, parenting, peer, self-regulation, and a genetic factor associated with profile inclusion. In the following section, we will use constructs from John Henryism theory and resilience theory to support our expectation that the hypothesized profiles will emerge as well as our hypotheses about factors that distinguish them.

John Henryism Theory

John Henryism (JH) is a high-effort coping style that features a determination to succeed by working hard even in the face of overwhelming SES-related stressors (James, 1994; James, Hartnett, & Kalsbeek, 1983). The JH construct takes its name from, and was partly inspired by, the legend of John Henry, “the steel-driving man.” According to the story (B. Williams, 1983), John Henry was an African American railroad worker in the late 1800s whose fame was derived from his participation in a steel-driving contest in which he defeated a steam-powered drill. John Henry was forced to harness his great strength to overpower the mechanical drill but afterward died of exhaustion. For James (1994), the fabled actions of John Henry serve to illuminate associations among high-effort coping, chronic sympathetic nervous system arousal, and health problems including hypertension. The construct comprises three main characteristics: efficacious mental and physical vigor, a strong commitment to hard work, and a single-minded determination to succeed. Reviews of the literature present mixed findings regarding an association between the JH construct and health outcomes, but more support the link than refute it, particularly for hypertension in community samples (Bennett et al., 2004; Kiecolt, Hughes, & Keith, 2009). The JH hypothesis has rarely been tested for mental health outcomes, but some theorists expect this coping style to be protective. James (1994) speculated that the “mental vigor” it entails protects against depression. Although not mentioning JH theory, stress-coping research proposes that persons who adopt problem-focused coping and believe they will succeed through persistence and effort are less likely to become depressed and more likely to refrain from drug use and other antisocial activities that are incompatible with their strivings for success (Bandura, 2002). Thus, the JH high-effort coping style is hypothesized to exact a toll on physical health while exerting a protective effect on mental health.

Using JH as a heuristic to inform a prototype for the physical health vulnerability profile suggest that these youths will display (a) high levels of planful self-regulation and academic competence, indicators of hard work and success; (b) low levels of behavioral and emotional problems; and (c) high AL resulting from the cumulative physiological toll on their bodies from their coping style. We also expect the families of these youths to value hard work and a determination to succeed. Such families will support these values by providing youths with high levels of support, vigilance, monitoring, and communication, a set of parenting practices demonstrated to promote goal-oriented persistence, academic achievement, and avoidance of adjustment problems among rural African Americans (Brody et al., 2006; Brody, Kim, Murry, & Brown, 2004; Brody et al., 2005). Because of their singular focus on success, we also expect youths with the physical health vulnerability profile to be less peer oriented and to depend less on peers for help and support in dealing with negative experiences than youths in the resilient profile. Recent research indicates that adolescents who seek peer support in dealing with daily stressful events display lower cortisol levels than do adolescents who choose to cope without support from friends (Adams, Santo, & Bukowski, 2012). Cortisol levels constitute a component of AL.

Resilience Theory

Resilience has been conceptualized in various ways (see Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten, 2001; Rutter, 1999, 2000), but its essence is a recognition that people respond to adverse experiences in vastly differing ways. Some individuals appear to succumb to the most minor stresses, whereas others seem to cope successfully with highly traumatic experiences. Resilience researchers identify processes that moderate the effects of risk factors over time and contribute to competent youth functioning despite the risk; these processes are termed protective stabilizing effects (Luthar et al., 2000). Several processes, including involved-vigilant parenting, peer social support, planful self-regulation and academic competence, have demonstrated moderation effects in the association of exposure to cumulative SES risk with the development of conduct problems and depressive symptoms (R. H. Bradley, Rock, Caldwell, Harris, & Hamrick, 1987; Brody, Chen, Kogan, Smith, & Brown, 2010; Brody et al., 2006; Brody et al., 2003; Conger et al., 2002; Kim & Brody, 2005). Reviews of the resilience literature identify involved-vigilant parenting as one of the most robust predictors of resilient adaptation in children and adolescents (Luthar & Zelazo, 2003; Masten, 2001). For African American youths, parenting that includes high levels of support and vigilant monitoring with low levels of harshness promotes a positive sense of self that enables youths to cope effectively with both daily hassles and acute stressors (Luthar et al., 2000). The provision of involved-vigilant parenting contributes to a protective cascade that features youths’ development of high levels of planful self-regulation and academic competence, formation of peer networks that support prosocial behavior, and avoidance of emotional and behavioral problems (Brody, Chen, & Kogan, 2010; Kogan et al., 2011). Thus, like the hypothesized characteristics of those with the physical health vulnerability profile, youths in the resilient profile are expected to receive relatively high levels of involved-vigilant parenting and be rated by their teachers as relatively high on planful self-regulation. Similarity on these protective-stabilizing dimensions is hypothesized to account for the low levels of behavioral and emotional problems displayed by youths with either of these profiles across adolescence. Youths with the physical and mental health vulnerability profile, on the other hand, are hypothesized to be exposed to levels of cumulative SES risks that are indistinguishable from the levels that youths with the two focal profiles encounter, but are hypothesized to evince higher levels of behavioral problems, emotional problems, and AL. We expect youths with the physical and mental health vulnerability profile to report receiving relatively low levels of involved-vigilant parenting and their teachers to rate them as relatively low on planful self-regulation and academic competence. Low levels of involved-vigilant parenting at home, along with exposure to cumulative SES risk, have been associated with impaired self-regulation particularly with respect to anger and aggression, elevated levels of depressive symptoms (Brody & Flor, 1998; D. Schwartz, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1997), and higher HPA activity and AL levels (Evans, Kim, Ting, Tesher, & Shannis, 2007; Evans & Kutcher, 2011). Without the benefit of protective-stabilizing parenting and the protective self-regulatory and academic qualities it facilitates, adolescents with the physical and mental health vulnerability profile are expected to show stronger behavioral, emotional, and AL reactivity to cumulative SES risks.

Recently, resilience theory has been expanded to include genetic factors (Cicchetti & Blender, 2006; Kim-Cohen & Gold, 2009). A basic presumption of this expansion is that the multiple determinants of an individual’s reactivity to chronic or acute stressors include genetic inheritance. Evidence of marked variability in response among people exposed to the same environmental risk implies that individual differences in genetic susceptibility might be at work (Caspi, Hariri, Holmes, Uher, & Moffitt, 2010). One such genetic factor is variation at the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4. We tested the hypothesis that a contributor to the predicted difference in AL levels between youths in the physical health risk vulnerability profile and the resilient profile involves SLC6A4. We predicted that youths in the physical health risk vulnerability profile would be more likely than those in the resilient profile to carry a short allele of a variable nucleotide repeat polymorphism in the promoter region of SLC6A4 known as the 5-HTT linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR). We further predicted that carrying this allele would render youths more sensitive to cumulative SES risks and to parent- and self-imposed pressures to succeed, which will be reflected in the physiological strain that AL indexes. Next, we describe the 5-HTTLPR and present evidence for these hypotheses.

The serotonin transporter SLC6A4 is a key regulator of serotonergic neurotransmission, localized to 17p13 and consisting of 14 exons and a single promoter. Variation in the promoter region of the gene, the 5-HTTLPR, results in two main variants, a short (s) and a long (l) allele; the presence of the s allele results in lower serotonin transporter availability. The s variant has 12 copies, and the l variant 14 copies, of a 22-bp repeat element. Recent research by neuroscientists supports the proposition that more youths with the physical health vulnerability profile will carry the s allele than will youths in the resilient profile (Caspi et al., 2010; Way & Taylor, 2010b). Research on the neuroscience of information processing indicates that the 5-HTTLPR genotype affects the processing of social cues, including threat-related cues. Specifically, the s allele is associated with greater activity in the amygdala (Heinz et al., 2005), a brain region involved in the processing of verbal and nonverbal threats (Isenberg et al., 1999), and with enhanced reactivity to punishment cues (Battaglia et al., 2005; Hariri, Drabant, & Weinberger, 2006) and financial stressors (Crişan et al., 2009; Roiser et al., 2009). Other research suggests that s allele carriers may be disposed to rumination as they direct preferential attention toward threat-related stimuli and have difficulty disengaging from such stimuli (Beevers, Wells, Ellis, & McGeary, 2009; Osinsky et al., 2008). Taken together, this literature is consistent with the proposition, informed by neuroimaging and prior G×E research involving the 5-HTTLPR that, because of their genetic makeup, carriers of the s allele are more likely to be hypervigilant and reactive to SES-associated risks and to family and personal pressures to succeed than are carriers of the ll genotype (Caspi et al., 2010). Conversely, the ll genotype can be expected to exert protective effects by modulating reactivity to environmental effects through emotional self-regulatory mechanisms that include downregulation of rumination, self-recriminations for not meeting personal standards, and negative emotions such as frustration and anger. These effects would render youths in the resilience profile less sensitive to contextual stress and pressures to succeed, resulting in lowered AL.

Overview of the Current Study

We investigated the developmental precursors of a pattern described in the adult health disparities literature in which, relative to European Americans, African Americans evince higher levels of physical health problems but similar levels of psychological adjustment. On the basis of theoretical and empirical literature, we hypothesized that different patterns of exposure to cumulative SES risks would emerge for rural African American youths over a period of 8 years, with a sizable number characterized by high AL and low adjustment problems (physical health vulnerability profile). In addition, we anticipated that protective factors would distinguish the profiles. We investigated the study hypotheses longitudinally with a representative sample of rural African American youths. Cumulative SES risk and protective processes were assessed during preadolescence, ages 11-13 years; indicators of psychological adjustment were assessed at ages 14-18 years; genotyping at the 5-HTTLPR was conducted at age 16 years; and AL was assessed at the beginning of emerging adulthood, age 19 years. We took a person-centered perspective, testing the grouping hypotheses with confirmatory latent profile analyses (LPA). LPA creates a taxonomy based on similar patterns of response (McCutcheon, 1987); individuals within the same latent class are homogenous and distinct from other classes. LPA is a relatively anonymous approach in which the number of classes and the substantive characterization of the profiles that represent those classes are determined by an iterative process. LPA is also a “person-centered” approach, in which groups of individuals are prioritized, rather than a traditional approach (e.g., regression) that prioritizes variable-centered models. In addition, LPA allows the testing of hypotheses involving predictors of class membership. We used multinomial logistic regression to test hypotheses about the ways in which protective processes and the 5-HTTLPR s allele would distinguish the profiles.

Method

Participants

African American primary caregivers and a target child selected from each family participated in annual data collections; target child mean age was 11.2 years at the first assessment and 19.2 years at the last assessment. The families resided in nine rural counties in Georgia, in small towns and communities in which poverty rates are among the highest in the nation and unemployment rates are above the national average (Proctor & Dalaker, 2003). At the first assessment, although the primary caregivers in the sample worked an average of 39.4 hours per week, 46.3% lived below federal poverty standards; the proportion was 49.1% at the last assessment. Of the youths in the sample, 53% were female. At the age 11 data collection, a majority (78%) of the caregivers had completed high school or earned a GED; the median family income per month was $1655 at the age 11 data collection and $1169 at the age 19 data collection. The decrease in family income and increase in the proportion of families living in poverty over time were due to the economic recession that was occurring during 2010, when the last wave of data was collected. Overall, the families can be characterized as working poor.

At the first assessment, 667 families were selected randomly from lists of 5th-grade students that schools provided (see Brody, Murry, et al., 2004, for a full description). From a sample of 561 at the age 18 data collection (a retention rate of 84%), 500 emerging adults were selected randomly to participate in the assessments of allostatic load and other variables at the age 19 data collection; of this subsample, 489 agreed to participate. Analyses indicated that the sample providing data at age 19 was comparable on indicators of cumulative risk and adjustment patterns to the larger sample who provided data at ages 11 through 18. Of the 489 participants for whom data on allostatic load had been collected, 443 provided DNA samples and were successfully genotyped at the 5-HTTLPR. Comparisons, using independent t tests and chi-square tests, of the 443 youths who provided genetic data with the 46 who did not provide it did not reveal any differences on any demographic or study variables.

Procedure

All data were collected in participants’ residences using a standardized protocol. One home visit that lasted approximately 2 hours took place at each wave of data collection. Two African American field researchers worked separately with the primary caregiver and the target child. Interviews were conducted privately, with no other family members present or able to overhear the conversation. Primary caregivers consented to their own and the youths’ participation in the study, and the youths assented to their own participation.

Measures

Preadolescent cumulative risk, parenting processes, protective peer relationships, and target youth protective factors

Three waves of preadolescent data were collected when the target youths were 11, 12, and 13 years of age.

Cumulative risk

Numerous studies of both physical morbidity and psychological dysfunction support the basic tenet of cumulative socioeconomic risk. Seven standard indicators of such risk were assessed, with each risk factor scored dichotomously (0 if absent, 1 if present; see Evans, 2003; Kim & Brody, 2005; Rutter, 1993; Sameroff, 1989; Werner & Smith, 1982; Wilson, 1987). Cumulative risk was defined as the average of the risk factors across the three annual preadolescent assessments. This yielded a cumulative risk index that ranged from 0 to 21 (M = 6.83, SD = 3.98). The seven risk indicators were family poverty as assessed using United States government criteria, primary caregiver noncompletion of high school or an equivalent, primary caregiver unemployment, single-parent family structure, maternal age of 17 years or younger at the target youth’s birth, family receipt of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and income rated by the primary caregiver as not adequate to meet all needs.

Parenting processes

The protective parenting processes of support, monitoring, and the adverse practice of harsh parenting were assessed via target youth reports. A revised version of the four-item Social Support for Emotional Reasons subscale from Carver, Scheier, and Weintraub’s (1989) COPE scale assessed levels of parental support. On a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot), the target youth responded to items such as, “I get emotional support from my caregiver” and “I get sympathy and understanding from my caregiver.” Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .78 to .87 across the three waves. The three-item Unsupervised Opportunity Scale (Brody, Beach, Philibert, Chen, & Murry, 2009) assessed caregiver monitoring. On a response scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (7 or more times), target children indicated how often during the past 2 months they went after school to a place where no adults were around, were with a member of the opposite sex, and went out on a weekend without adult supervision. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .62 to .84 across the three waves. Four items that index harsh parenting drawn from the Harsh/Inconsistent Parenting Scale (Brody et al., 2001) assessed caregivers’ use of slapping, hitting, and shouting to discipline the target youth. The youth rated each harsh disciplinary practice on a scale that ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .54 to .66 across the three waves. Low internal consistency is common in the literature for measures of harsh parenting due to low base rates of these disciplinary practices (Simons & Burt, 2011; Whitbeck et al., 1997). Each parenting measure was averaged across all waves of assessment. Finally, the measures of support, monitoring, and reverse coded harsh parenting were standardized and summed to form the involved-vigilant protective parenting construct, α = .84.

Protective peer relationships

Protective peer relationships were assessed via target youth reports. The same revised version of the four-item Social Support for Emotional Reasons subscale from Carver et al.’s (1989) COPE scale was used to assess levels of peer support. On a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot), the target youth responded to items such as, “I get emotional support from one of my friends” and “I discuss my feelings with a friend I feel close to.” On a response set ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (very or often true), youths rated their friendship quality using a three-item scale. An example item is, “If my friend had a problem, I would try to help.” Each peer relationship measure was averaged across the three waves of assessment, then they were standardized and summed to form the protective peer relationship construct, α = .86.

Target youth protective factors: Planful self-regulation and school competence

One of each target youth’s teachers assessed planful self-regulation and school competence at each of the three waves of data collection that took place during preadolescence. Planful self-regulation was assessed using the five-item Self-Control Inventory (Humphrey, 1982). Each item was rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (almost always). Example items include, “sticks to what he/she is doing even during long, unpleasant tasks until finished,” “works toward a goal,” and “pays attention to what he/she is doing.” Alphas across the three preadolescent waves ranged from .79 to .93. The teachers also completed a revised version of the School subscale of the Perceived Competence Scale (Harter, 1982), which measures scholastic competence. The subscale consists of seven items that in the revised version were rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (always). Example items include, “very good at his/her school work,” “just as smart as other kids his/her age,” and “does well in class.” Alphas across the three waves ranged from .83 to .92. The means of teachers’ ratings of self-regulation and school competence across the three preadolescent assessments constituted the units of analysis.

Adolescent psychological adjustment

Five waves of adolescent data were collected when the target youths were 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18 years of age. To assess adolescent adjustment, “insider” reports from the adolescents themselves as well as “outsider” reports from mothers were used. These two perspectives provide a more complete appraisal across the adolescent years than does a single perspective (Brody & Sigel, 1990). Adolescents reported their delinquent behavior, substance use, and depressive symptoms; mothers reported their perceptions of adolescents’ externalizing (aggression, rule breaking) and internalizing (withdrawal, anxiety, depression) problems.

Adolescent delinquent behavior, depression, and substance use

At ages 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18, adolescents reported their own delinquent/antisocial behavior, depressive symptoms, and substance use using 14 questions from the National Youth Survey (Elliott, Ageton, & Huizinga, 1985). They indicated how many times during the past year they engaged in activities such as theft, truancy, fighting, and vandalism, and how many times they were suspended from school. Because this instrument assesses count data, internal consistency analyses were not executed. The count data were averaged across assessments to form the unit of analysis. Self-reports of depressive symptoms were obtained at ages 16 and 17 using the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Helsel & Matson, 1984). Adolescents rated each of 27 symptoms on a scale of 0 (absent), 1 (mild), or 2 (definite). Alphas were .86 at age 16 and .84 at age 17; the average of the two assessments served as the unit of analysis. At all five data collection waves, adolescents reported their past-month use of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana, as well as excessive drinking, on a widely used instrument from the Monitoring the Future Study (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2007). Responses to these four items were summed to form a substance use composite, a procedure that is consistent with our own and others’ prior research (Brody & Ge, 2001; Newcomb & Bentler, 1988). Average substance use across time constituted the unit of analysis.

Adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems

Mothers assessed adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms when the youths were 14, 16, 17, and 18 years of age using the parent form of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991); this assessment was not included in the protocol at the age 15 data collection. The Aggressive and Rule Breaking subscales were used to index externalizing symptoms; alphas for these 35 items ranged from .90 to .92 across data collection waves. The Withdrawn and Anxious/Depressed subscales were used to index internalizing symptoms; alphas for these 21 items ranged from .84 to .91 across waves. Each indicator of internalizing or externalizing behavior was averaged across all assessments.

Emerging adult allostatic load

The protocol for measuring allostatic load in emerging adulthood, when youths were 19 years of age, was based on procedures that Evans and colleagues (Evans, 2003; Evans et al., 2007) used for field studies involving children and youths. Resting blood pressure was monitored with a Critikon Dinamap Pro 100 (Critikon; Tampa, FL) while the emerging adult sat reading quietly. Seven readings were taken every 2 minutes, and the average of the second through the seventh readings was used as the resting index. This procedure yields highly reliable indices of chronic resting blood pressure (Kamarck et al., 1992). Overnight (8 p.m. to 8 a.m.) urine output was collected beginning on the evening of data collection so that emerging adults’ urinary catecholamines and cortisol could be assayed. All urine voided during this time was stored on ice in a container with a preservative (metabisulfite). Total volume was recorded, and four 10-ml. samples were randomly extracted and deep frozen at −80° C until subsequent assays were completed. The pH of two of the 10-ml. samples was adjusted to 3 to inhibit oxidation of catecholamines. Total unbound cortisol was assayed with a radioimmune assay (Contreras, Hane, & Tyrrell, 1986). Epinephrine and norepinephrine were assayed with high-pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (Riggin & Kissinger, 1977). Creatinine was assayed to control for differences in body size and incomplete urine voiding (Tietz, 1976). Technicians blind to the participants’ cumulative risk status assayed the samples.

Allostatic load was calculated by summing the number of physiological indicators on which each emerging adult scored in the top quartile of risk; possible scores ranged from 0 to 6. The allostatic load indicators included overnight cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine; resting diastolic and systolic blood pressure; and fat deposits measured via body mass index (weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters). Prior studies of allostatic load in adults (Kubzansky, Kawachi, & Sparrow, 1999; Seeman, Singer, Ryff, Dienberg Love, & Levy-Storms, 2002; Singer & Ryff, 1999) and in children (Evans, 2003; Evans et al., 2007) have included similar metrics, combining multiple physiological indicators of risk into one total allostatic load index.

Genotyping

Participants’ DNA was obtained at age 16 using Oragene DNA kits (Genetek; Calgary, Alberta, Canada). Participants rinsed their mouths with tap water, then deposited 4 ml of saliva in the Oragene sample vial. The vial was sealed, inverted, and shipped via courier to a central laboratory in Iowa City, where samples were prepared according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Genotype at the 5-HTTLPR was determined for each sample as described previously (S. L. Bradley, Dodelzon, Sandhu, & Philibert, 2005) using the primers FGGCG TTGCCGCTCTGAATGC and R-GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC, standard Taq polymerase and buffer, standard dNTPs with the addition of 100μmM7-deaza GTP, and 10% DMSO. The resulting polymerase chain reaction products were electrophoresed on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel, and products were visualized using silver staining. Genotype was then called by two individuals blind to the study hypotheses and other information about the participants. Of the sample, 5.0% were homozygous for the short allele (ss), 33.8% were heterozygous (sl), and 61.2% were homozygous for the long allele (ll). None of the alleles deviated from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p = .77, ns). Consistent with prior research (Brody et al., 2011; Hariri et al., 2005), genotyping results were used to form two groups of participants: those homozygous for the long allele (coded as 0, n = 271, 61.2%) and those with either one or two copies of the short allele (coded as 1, n = 172, 38.8%).

Statistical Analyses

We used a person-centered approach in this study to identify groups of adolescents who showed similar patterns of cumulative SES risk, adjustment problems, and allostatic load using Latent Profile Analysis (LPA). LPA identifies latent profiles on the basis of observed response patterns (B. Muthén, 2006) and is conceptually similar to cluster analysis. LPAs were performed with Mplus version 6.1 (L. K. Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010). LPA models are fit in a series of steps starting with a one-class model; the number of classes is subsequently increased until there is no further improvement in the model. The implementation of LPA in this study allowed for missing data on the measured outcomes using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation.

Model comparison was conducted using a series of standard fit indices, including the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), the sample size adjusted BIC (SSA BIC; Sclove, 1987), and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987); lower scores represent better-fitting models. We also considered the Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) likelihood ratio test, which compares the estimated model with a model having one class less than the estimated model. The LMR likelihood ratio test produces a p-value that indicates the better-fitting model. A p-value less than .05 indicates that the model with one class less should be rejected in favor of the estimated model. We also assessed entropy, which refers to average accuracy in assigning individuals to classes. Entropy values range from 0 to1, with higher scores reflecting greater accuracy in classification. Optimal models were chosen based on goodness-of-fit and parsimony. Gender was included in each model as a control variable.

After the hypothesized groups were identified, we then examined multinomial logistic regression models to identify the factors that were hypothesized to predict latent profile class membership. Three domains of risk and protective factors were examined: youth characteristics (gender, s allele presence or absence, planful self-regulation, and school competence), involved-vigilant protective parenting, and positive peer relationships. Multinomial logistic regression allowed us to examine simultaneously the possibility that youths were more likely to be in a particular profile group than were individuals with different personal, parenting, peer, and genetic characteristics.

Results

LPA Models

The LPA analyses were performed in three stages. In the first stage, two separate LPAs were conducted; one focused on the variables of cumulative risk and allostatic load and the second focused on the insider/outsider assessments of adolescent adjustment problems— internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, delinquent activity, substance use, and depression. Fit statistics for the first stage of LPAs, described previously, are summarized in Table 1. The AIC and BIC values decreased as the number of classes increased. The LMR likelihood ratio test indicated that the three-class model for cumulative SES risk and allostatic load was more favorable than the two-class model (p < .05), but the four-class model was not better than the three-class model (p > .05). Similarly, the LMR ratio test indicated that the two-class model for adolescent adjustment problems was more favorable than the three-class model.

Table 1.

Fit Indices for General Latent Profile Analysis

| Free Parameters |

AIC | BIC | SSA BIC | Entropy | LMR p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Risk/Allostatic Load | ||||||

| 1-class model | 4 | 3277.88 | 3294.65 | 3281.95 | -- | -- |

| 2-class model | 8 | 3217.89 | 3251.43 | 3226.04 | 0.68 | 0.000 |

| 3-class model | 12 | 3190.83 | 3241.14 | 3203.05 | 0.78 | 0.000 |

| 4-class model | 16 | 3033.40 | 3100.48 | 3049.69 | 0.99 | 0.168 |

|

| ||||||

| Adjustment Problems | ||||||

| 1-class model | 10 | 9395.56 | 9437.48 | 9405.74 | -- | -- |

| 2-class model | 17 | 8934.35 | 9005.62 | 8951.67 | 0.93 | 0.000 |

| 3-class model | 24 | 8719.41 | 8820.03 | 8743.86 | 0.91 | 0.361 |

| 4-class model | 31 | 8462.87 | 8592.83 | 8494.44 | 0.93 | 0.008 |

|

| ||||||

| Confirmatory Latent Profile Analysis with Two Latent Categorical Variables | ||||||

| 2 × 3 model | 31 | 12124.16 | 12254.12 | 12155.73 | 0.84 | -- |

| 2 × 2 model | 26 | 12154.24 | 12263.25 | 12180.72 | 0.81 | -- |

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; SSA BIC = Sample Size Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion; LMR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test.

In the second stage of the analyses, the final models for the separate solutions for cumulative risk and allostatic load and for adolescent adjustment problems were entered together in one overall model (confirmatory LPA; see L. K. Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2010, example 7.14) that included the influence of gender on class probability. Two categorical latent variables, one for each LPA model, were estimated. In selecting our final model, we considered whether the latent classes evinced logical patterns, were distinct from other classes, and had adequate sample sizes for follow-up analyses. The confirmatory 2 × 3 LPA model identified a small class of 17 participants that was deemed inadequate for meaningful follow-up analyses. Taking into consideration model fit as well as interpretation, we therefore selected a confirmatory 2 × 2 confirmatory LPA model as the final model. This model identified four classes. Of the study participants, 229 were initially classified into a low cumulative SES risk/low AL/low adjustment problem group; 151 were classified into a high cumulative risk/high AL/low adjustment problem group; 63 were classified into a moderate cumulative SES risk/low AL/high adjustment problem group; and 46 were classified into a high cumulative SES risk/high AL/high adjustment problem group.

The third stage of confirmatory LPA analysis was executed with the youths manifesting the low-risk profile to identify a group of resilient youths characterized by high exposure to cumulative SES risk, low AL, and low adjustment problems. A review of the individual plots of cumulative SES risk within the low-risk profile revealed substantial individual variation. Although the mean level was relatively low, within-group variation was clearly evident (M = 5.58, SD = 3.92, variance = 15.36, range = 0-15, cumulative risk score > 8 for 25% of profile members). Informed by these data, we executed a confirmatory LPA modeling technique (see Finch & Bronk, 2011, for computational procedures in Mplus) on the members of the low-risk profile identified in the second stage of the LPA process. This confirmatory LPA ran a two-class model on the means of each of the SES risk indicators that were measured at the three time points across preadolescence. The mean SES risk indicators were constrained for one of the two classes to create a group that was similar to the physical health vulnerability profile in terms of cumulative SES risk. The analysis identified with high accuracy (entropy = .83) a robust resilient profile that included 115 youths with high cumulative SES risk/low AL/low adjustment problems (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

ANOVA and Descriptive Statistics of Components of the Cumulative Risk Index for the Latent Profile Classes

| Latent Profile Classes |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk (n = 114) |

Resilient (n = 115) |

Physical health vulnerability (n = 151) |

Mental health vulnerability (n = 63) |

Physical and mental health vulnerability (n = 46) |

|||||||

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F |

| Total index score | 2.46a | 1.88 | 8.66b | 2.82 | 8.12b | 3.28 | 6.89c | 3.71 | 8.78b | 4.67 | 75.92*** |

| Parent age at child birth ≤ 17 |

0.04a | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.03a | 0.18 | 0.13b | 0.34 | 1.59 |

| Poverty 150% below limit | 0.41a | 0.56 | 2.43b | 0.64 | 2.23b | 1.02 | 1.81c | 1.12 | 1.93c | 1.10 | 96.50*** |

| Parent unemployment | 0.21a | 0.59 | 0.81b | 1.11 | 0.70b | 1.08 | 0.60b | 0.98 | 1.17c | 1.39 | 9.25*** |

| Single-parent family | 0.81a | 1.16 | 2.11b | 1.13 | 1.96b | 1.21 | 1.95b | 1.24 | 2.11b | 1.21 | 23.48*** |

| TANF receipt | 0.02a | 0.19 | 0.21b | 0.58 | 0.21b | 0.61 | 0.27b | 0.74 | 0.59c | 1.11 | 7.08*** |

| Parent education < high school |

0.58a | 1.07 | 1.97b | 1.26 | 1.93bd | 1.30 | 1.17c | 1.35 | 1.52cd | 1.39 | 24.94*** |

| Inadequate income for needs |

0.40a | 0.70 | 1.06b | 1.07 | 1.01b | 1.09 | 1.05b | 1.07 | 1.33b | 1.05 | 10.63*** |

Note. Means designated with the same superscript are not significantly different based on least significant differences post-hoc comparisons (p < .05). AL = allostatic load; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

p < .001.

Table 3.

ANOVA and Descriptive Statistics of Components of Adjustment Problems and Allostatic Load for the Latent Profile Classes

| Latent Profile Classes |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk (n = 114) |

Resilient (n = 115) |

Physical health vulnerability (n = 151) |

Mental health vulnerability (n = 63) |

Physical and mental health vulnerability (n = 46) |

|||||||

| Variables | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F |

| Adjustment problems | |||||||||||

| Internalizing problems | 1.09a | 1.24 | 1.51bd | 1.50 | 1.22ab | 1.29 | 1.76cd | 1.54 | 2.29c | 2.11 | 7.16*** |

| Externalizing problems | 1.38a | 1.24 | 1.93b | 1.56 | 1.71ab | 1.60 | 3.07c | 1.88 | 3.18c | 2.10 | 18.47*** |

| Delinquent behaviors | 0.78a | 0.80 | 0.79a | 0.90 | 0.72a | 0.81 | 4.66b | 1.20 | 4.80b | 1.23 | 381.99*** |

| Substance use | 0.56a | 1.04 | 0.41a | 0.77 | 0.43a | 0.80 | 1.89b | 1.56 | 2.12b | 1.96 | 39.43*** |

| Depression | 6.04a | 4.95 | 6.59a | 5.03 | 6.22a | 5.01 | 9.40b | 5.30 | 10.08b | 6.38 | 9.24*** |

|

| |||||||||||

| Allostatic load | |||||||||||

| Quartile score (0-6)1 | 0.84a | 0.78 | 0.49b | 0.50 | 2.72c | 0.77 | 0.57b | 0.56 | 2.87c | 0.75 | 279.57*** |

| Body mass index | 25.49a | 6.05 | 25.63a | 6.40 | 31.08b | 8.92 | 25.05a | 5.91 | 30.07b | 9.46 | 15.52*** |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 109.08ac | 12.65 | 107.46a | 10.28 | 117.79b | 11.93 | 112.25c | 9.40 | 121.03b | 11.70 | 22.48*** |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 71.30a | 8.76 | 69.31a | 6.37 | 77.55b | 8.68 | 69.28a | 7.10 | 76.35b | 10.66 | 23.60*** |

| Norepinephrine (ng/mg creatinine) | 35.31a | 27.10 | 29.12ab | 14.75 | 51.41c | 31.31 | 25.74b | 15.86 | 57.74c | 30.32 | 24.44*** |

| Epinephrine (ng/mg creatinine) | 5.84a | 4.96 | 4.89a | 2.90 | 9.94b | 6.83 | 5.57a | 4.54 | 11.92c | 7.75 | 25.73*** |

| Cortisol (μg/mg creatinine) | 3.90a | 2.74 | 3.79a | 2.23 | 5.88b | 4.19 | 4.33a | 3.17 | 5.72b | 3.33 | 10.15*** |

Note. Means designated with the same superscript are not significantly different based on least significant differences post-hoc comparisons (p < .05). AL = allostatic load.

Derived from the total number of biomarkers (systolic and diastolic blood pressure; overnight urinary cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine; and body mass index) on which each participant fell into the upper quartile of risk.

p < .001.

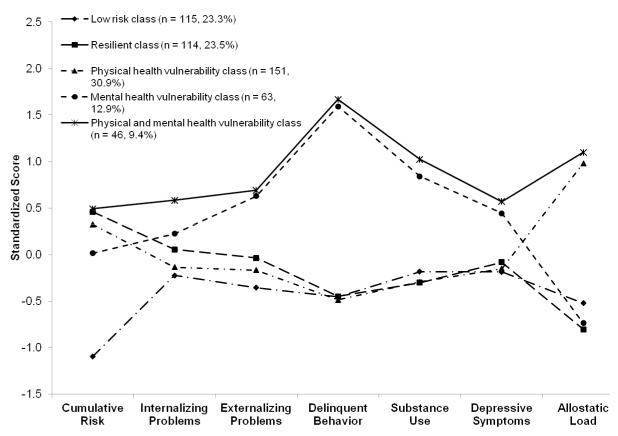

The Latent Class Profiles and their Cumulative SES Risk, Psychological Adjustment, and Allostatic Load

The five latent class profiles are depicted graphically in Figure 1. The standardized means for each profile on cumulative SES risk, adjustment problems, and allostatic load depicted in Figure 1 are based on analyses presented in Tables 2 and 3. These two tables present the means of the study constructs for each profile along with univariate analyses designed to detect constructs that differ among the five profiles. The one-way analyses of variance presented in these tables produces an F statistic indicating whether significant variation exists in an indicator across groups. Least squares post-hoc comparisons were used to test for significant differences among cell means.

Figure 1.

Latent profile membership standardized scores for the study sample.

A first profile displayed high levels of cumulative SES risk, low levels of adjustment problems, and high AL. On the basis of the adult health disparities literature and theoretical conceptualizations, these youths were classified into a physical health vulnerability profile. This classification included the largest number of youths (n = 151, 30.9%) and supported the study hypothesis that a sizable group of rural African American adolescents would emerge who resembled a pattern described in the adult health disparities literature. Youths in a second profile displayed equally high exposure to cumulative SES risk and similarly low levels of adjustment problems across adolescence as did those in the first profile, along with substantially lower (> 4 SD) AL. Given evidence of exposure to high levels of cumulative risk coupled with low levels of adjustment problems and AL, we classified these youths into a resilient profile (n = 115, 23.5%). A third profile, the smallest (n = 46, 9.4), was classified as displaying high physical and mental health vulnerability. These youths were characterized by exposure to high cumulative SES risk along with high levels of adjustment problems and high AL. Youths in this profile were exposed to similar levels of cumulative SES risks as were youths in the physical health and resilient profiles, yet they evinced much higher levels of adjustment problems across adolescence than did youths in either of the other profiles. They also displayed substantially higher AL than did resilient youths and high levels of AL that were indistinguishable from those of youths in the physical health vulnerability profile. Youths in the fourth profile were exposed to moderate levels of cumulative SES risk coupled with high adjustment problems and low AL. These youths comprised a mental health vulnerability profile (n = 63, 12.9%). The fifth and last profile was characterized by relatively low levels of exposure to cumulative SES risk, low levels of adjustment problems across adolescence, and low AL. These youths were classified into a low risk profile (n = 114, 23.3%). Youths in the resilient profile evinced levels of adjustment problems and AL that were indistinguishable from those of youths in the low risk profile. Youths in the physical health vulnerability profile, relative to those in the low risk profile, evinced indistinguishably low levels of adjustment problems but substantially higher levels of AL (> 2 SD).

Multinomial Logistic Regression Analyses

We conducted two multinomial logistic regressions using the physical health vulnerability profile and the resilient profile as the reference groups to determine how the hypothesized protective processes and 5-HTTLPR status contributed to inclusion in each focal profile. These analyses were designed to determine which factors were significantly related to inclusion in each of these two profiles versus each of the other profiles. All of the protective processes and 5-HTTLPR status were entered simultaneously into each of the models. Table 4 displays the results with the physical health vulnerability profile as the reference group; Table 5 presents the results with the resilient profile as the reference group. A negative coefficient indicates a greater likelihood of inclusion in the reference profile, and a positive coefficient indicates a greater likelihood of inclusion in a comparison profile.

Table 4.

Log Odds Coefficients and Odds Ratio for Latent Profile Classes with Gender, 5-HTTLPR Status, and Protective Factors during Preadolescent as Predictors Using the Physical Health Vulnerability Class as the Reference Group (N = 443)

| Latent Profile Class | Effect | Logit | SE | t | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | Male | 0.003 | 0.287 | 0.011 | 1.003 |

| 5-HTTLPR (s allele) | −0.507 | 0.278 | −1.820 | 0.602 | |

| Self-control | 0.019 | 0.074 | 0.257 | 1.019 | |

| School competence | 0.078 | 0.064 | 1.217 | 1.081 | |

| Peer relationship | 0.152 | 0.084 | 1.810 | 1.164 | |

| Parenting | −0.247** | 0.087 | −2.850 | 0.781 | |

|

| |||||

| Resilient | Male | −0.424 | 0.282 | 1.500 | 0.655 |

| 5-HTTLPR (s allele) | −0.655* | 0.280 | 2.342 | 0.520 | |

| Self-control | −0.036 | 0.058 | 0.626 | 0.964 | |

| School competence | −0.028 | 0.048 | 0.593 | 0.972 | |

| Peer relationship | 0.211** | 0.080 | −2.634 | 1.235 | |

| Parenting | −0.033 | 0.079 | 0.414 | 0.968 | |

|

| |||||

| Mental health vulnerability |

Male | 0.894* | 0.375 | 2.382 | 2.445 |

| 5-HTTLPR (s allele) | −0.646 | 0.345 | −1.874 | 0.524 | |

| Self-control | −0.203** | 0.068 | −2.984 | 0.816 | |

| School competence | 0.073 | 0.066 | 1.103 | 1.076 | |

| Peer relationship | 0.101 | 0.102 | 0.989 | 1.106 | |

| Parenting | −0.448*** | 0.085 | −5.259 | 0.639 | |

|

| |||||

| Physical and mental health vulnerability |

Male | 0.557 | 0.377 | 1.478 | 1.746 |

| 5-HTTLPR (s allele) | −0.898* | 0.380 | −2.365 | 0.407 | |

| Self-control | −0.215* | 0.086 | −2.508 | 0.806 | |

| School competence | 0.102 | 0.085 | 1.203 | 1.108 | |

| Peer relationship | 0.079 | 0.109 | 0.724 | 1.082 | |

| Parenting | −0.442*** | 0.100 | −4.430 | 0.643 | |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 5.

Log Odds Coefficients and Odds Ratio for Latent Profile Classes with Gender, 5-HTTLPR Status, and Protective Factors during Preadolescent as Predictors Using the Resilient Class as the Reference Group (N = 443)

| Latent Profile Class | Effect | Logit | SE | t | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | Male | 0.427 | 0.305 | 1.397 | 1.532 |

| 5-HTTLPR (s allele) | 0.148 | 0.311 | 0.476 | 1.160 | |

| Self-control | 0.055 | 0.075 | 0.738 | 1.057 | |

| School competence | 0.106 | 0.064 | 1.653 | 1.112 | |

| Peer relationship | −0.059 | 0.092 | −0.646 | 0.942 | |

| Parenting | −0.214* | 0.090 | −2.369 | 0.808 | |

| Physical health vulnerability |

Male | 0.424 | 0.282 | 1.500 | 1.527 |

| 5-HTTLPR (s allele) | 0.655* | 0.280 | 2.342 | 1.925 | |

| Self-control | 0.036 | 0.058 | 0.626 | 1.037 | |

| School competence | 0.028 | 0.048 | 0.593 | 1.029 | |

| Peer relationship | −0.211** | 0.080 | −2.634 | 0.810 | |

| Parenting | 0.033 | 0.079 | 0.414 | 1.033 | |

|

| |||||

| Mental health vulnerability |

Male | 1.318** | 0.391 | 3.374 | 3.735 |

| 5-HTTLPR (s allele) | 0.008 | 0.369 | 0.023 | 1.008 | |

| Self-control | −0.166* | 0.070 | −2.372 | 0.847 | |

| School competence | 0.102 | 0.069 | 1.481 | 1.107 | |

| Peer relationship | −0.111 | 0.109 | −1.016 | 0.895 | |

| Parenting | −0.415*** | 0.089 | −4.663 | 0.661 | |

|

| |||||

| Physical and mental health vulnerability |

Male | 0.981* | 0.393 | 2.499 | 2.667 |

| 5-HTTLPR (s allele) | −0.244 | 0.403 | −0.605 | 0.784 | |

| Self-control | −0.179* | 0.087 | −2.044 | 0.836 | |

| School competence | 0.131 | 0.086 | 1.522 | 1.140 | |

| Peer relationship | −0.132 | 0.115 | −1.144 | 0.876 | |

| Parenting | −0.409*** | 0.103 | −3.958 | 0.664 | |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Physical health vulnerability profile

Youths who received high levels of protective parenting were more likely to be members of the physical health vulnerability profile than to be members of the (a) low risk, (b) mental health vulnerability, or (c) physical and mental health vulnerability profile. High levels of planful self-regulation were associated with membership in the reference profile rather than membership in the mental health vulnerability or physical and mental health vulnerability profile. In addition, carrying an s allele at the 5-HTTLPR was associated with a greater likelihood of membership in the reference profile than membership in the resilient profile or the physical and mental health vulnerability profile. Finally, being male was associated with a higher probability of membership in the mental health vulnerability profile than in the reference profile.

Resilient profile

Many of the results reported above for the factors that distinguished membership in the physical health vulnerability profile from membership in the other profiles were replicated for the resilient profile. Other findings also emerged. Receipt of protective parenting was linked to a higher probability of membership in the resilient profile than in the (a) low risk, (b) mental health vulnerability, or (c) physical and mental health vulnerability profile. High levels of planful self-regulation were also linked with a higher probability of membership in the resilient profile than in the mental health vulnerability or mental and physical health vulnerability profile. Of particular importance, not carrying an s allele at the 5-HTTLPR and having supportive friends distinguished membership in the resilient profile from membership in the physical health vulnerability profile. Finally, male youths had a lower probability of membership in the resilient profile than in the mental health vulnerability or physical and mental health vulnerability profile.

Discussion

Using a prospective design that was guided by John Henryism theory and resilience theory, we tested predictions designed to examine the developmental precursors for the counterintuitive patterning of physical and mental health outcomes in the adult health disparities literature. We predicted that LPA would empirically identify two theoretically important focal profiles: a physical health vulnerability profile and a resilient profile. This hypothesis was confirmed. The physical health vulnerability profile mirrored the counterintuitive pattern; youths were exposed to high levels of cumulative SES risk, evinced high levels of AL, and displayed low levels of adjustment problems. Youths in the resilient profile were also exposed to high levels of cumulative SES risk, yet they displayed low levels of AL along with low levels of adjustment problems. Together, these two profiles accounted for 54.4% of the representative sample of rural African Americans, with 30.9% included in the physical health vulnerability profile and 23.5% included in the resilient profile. These findings are consistent with propositions that poor health and health disparities during adulthood are tied to experiences earlier in life, particularly for persons growing up with the stressors associated with low SES (Shonkoff et al., 2009). The present findings are also consistent with theoretical propositions that some individuals are more susceptible to environmental stressors than are others. Thus, not all rural African American youths exposed to cumulative SES risks will develop physiological dysregulation.

The physical health vulnerability profile was suggested by John Henryism theory. Extrapolating the theory to adolescence, we predicted that a sizable group of youths would be identified who would resemble the legendary folk hero whose name the theory bears. They would be highly goal directed and hard working, have a singular focus on success, have little inclination to stray from conventional paths, have little need for peer support, and manifest a physiology that showed signs of wear and tear. The data supported John Henryism predictions. Teachers rated these youths as evincing high levels of planful self-regulation and academic competence. Self-reports and parent ratings revealed low levels of adjustment problems. The AL indicators showed that youths in this profile were at least two SD higher on the indicators than were those in the resilient and low risk profiles. Consistent with John Henryism theory, we surmise that these youths are beginning to experience physiological wear even though they appear psychologically well-adjusted.

The prediction that carrying an s allele at the 5-HTTLPR would distinguish the two focal profiles was based on recent expansions of resilience theory (Cicchetti & Blender, 2006; Kim-Cohen & Gold, 2009). Consistent with the study hypothesis, youths with the physical health vulnerability profile were more likely than those in the resilient profile to carry an s allele. This finding is consistent with the proposition, informed by neuroimaging and prior G×E research involving the 5-HTTLPR, that, because of their genetic makeup, youths carrying an s allele are more likely to be affected by SES risks and by family and personal pressures to succeed than are those with the ll genotype (Caspi et al., 2010). We speculate that this heightened sensitivity predisposes youths to be more attentive, vigilant, and, in turn, reactive to negative and threatening cues in general, whether they emanate from family, self, or the larger rural Southern community context (Munafò, Brown, & Hariri, 2008). This heightened reactivity is conjectured to trigger frequent releases of catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine) and cortisol. Supporting this conjecture are data indicating that carriers of the 5-HTTLPR s allele have a heightened cortisol response following exposure to stress (Way & Taylor, 2010a). The results also buttress suggestions that genetic status contributes to resilience (Kim-Cohen & Gold, 2009; Moffitt, Caspi, & Rutter, 2006). The observed buffering effects of not carrying an s allele suggested an emotional self-regulatory mechanism in which the genotype contributes to youths’ downregulation of rumination, self-recrimination for not living up to personal or family standards, and negative emotions that are linked to frustration, such as anger. Further research is needed to test this hypothesis.

An extrapolation of John Henryism theory suggested the role of peer support in distinguishing between the focal profiles. The theory implies a defensive, self-reliant coping style in which youths assume that others outside the family will not contribute to success strivings and might even interfere with them. Indeed, youths in the physical health vulnerability profile, compared with resilient profile youths, appear to be less socially connected and less likely to share their emotions with agemates. The present results build on recent research indicating that access to peer support has protective stabilizing properties that extend to physiological outcomes (see Adams et al., 2012). Exposure to contextual or self-imposed stress without peer support may result in elevated physiologic stress responses, whereas having peer support may attenuate the link, most likely by downregulating negative affective states that trigger neuroendocrine responses. These results support the proposition that access to family and peer support has beneficial effects on the functioning of biological stress regulation mechanisms across the life span and, ultimately, on health (Repetti, Taylor, & Saxbe, 2007).

A specific theoretical comment concerns factors that distinguish the two focal profiles from the mental health vulnerability profile and the physical and mental health vulnerability profile. Relative to those in the focal profiles, youths included in the other two vulnerability profiles were more likely to be male, receive less protective parenting, and evince low levels of planful self-regulation. These differences are consistent with other studies indicating that, when male youths are exposed to either moderate or high levels of life stress and receive low levels of protective parenting, they are more likely to respond by losing inhibitory controls (i.e., planful self-regulation) and manifesting higher levels of externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and drug use compared with female youths (Brody et al., 2006; Rutter, 1990). That this dysregulation was accompanied by elevated AL for youths with the physical and mental health vulnerability profile was likely due to their exposure to relatively greater cumulative SES risks and receipt of low levels of protective parenting, circumstances that have been shown to ramp up neuroendocrine indicators of AL (Evans et al., 2007).

The physical health vulnerability profile and the physical and mental health vulnerability profile both evinced similarly high levels of AL, even though youths with the former profile were more likely to carry an s allele at the 5-HTTLPR. We think this is an interesting finding for which there are two plausible explanations. First, the difference in percentages of youths carrying the s allele at the 5-HTTLPR may be due to a lack of power. The physical and mental health vulnerability profile was the smallest group to emerge from the LPA (9.3%). A larger sample might have revealed that the profiles had similar percentages of youths who carried the s allele at the 5-HTTLPR. A second explanation, one we endorse, is that there are multiple distinct pathways to elevated AL when youths are exposed to high levels of cumulative SES risks. The first, exemplified by those in the physical health vulnerability profile, involves the consequences of dealing with pressures to succeed while carrying an s allele that we discussed previously. These youths may appear to be coping well, and the youths themselves may think and report the same, until indicators of physiological stress are included in assessments of well-being. This could be termed a “cost” of coping pathways. A second pathway, exemplified in the physical and mental health vulnerability profile, involves a lack of countervailing protection to buffer the impact of exposure to SES stressors. The sequelae of growing up in these circumstances could include low self-regulation and emotion regulation skills, poor adjustment, and elevated neuroendocrine responses (Cicchetti & Toth, 2009).

From a public health perspective, the results suggest that developmentally well-timed preventive interventions designed to enhance coping and reduce the effects of stress during childhood, preadolescence, and adolescence may be necessary to interrupt the effects of exposure to SES risks on AL and psychological adjustment. Given the importance of family support and parenting, we believe that these prevention efforts should be family centered with a particular focus on parenting and the enhancement of self-regulatory skills. Helping parents to develop and exercise, at successive developmental stages, parenting practices that include emotional support, instrumental assistance, and communication about potential areas of concern promotes a positive sense of self and security that enables children, preadolescents, and adolescents to cope more effectively with both daily hassles and self-imposed pressures that can take a silent toll on physical and mental health (Luthar et al., 2000). Additional components of such prevention programming could equip youths at different ages with developmentally appropriate (a) stress-coping skills and cognitive behavioral management skills (Antoni et al., 2001), (b) mindfulness training that would help youths to relax and focus on the present (Bishop, 2002), and (c) interventions that help children and adolescents to build and access social support networks.

The present study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. Prospective research in which participants are younger than 11 years of age may demonstrate whether differences in profiles of adjustment and AL emerge earlier than preadolescence. It is also not known whether the results of this study generalize to urban African American families or to families of other ethnicities living in either rural or urban communities. Future studies should also incorporate variables similar to those included in this study, along with youth coping processes and social support from both extended family members and extrafamilial sources. Finally, the present results suggest that youths exposed to high levels of cumulative SES risk, even those who are behaviorally and emotionally well-adjusted, represent a group at particularly high risk for elevated allostatic load. Research on the design of preventive interventions for these youths may yield approaches that are effective in deterring their subsequent development of chronic diseases and the mental health challenges that accompany them.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number 5R01HD030588-16A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and Award Number 1P30DA027827 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Gene H. Brody, Institute for Behavioral Research, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia

Tianyi Yu, Institute for Behavioral Research, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia.

Yi-fu Chen, Institute for Behavioral Research, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia.

Steven M. Kogan, Institute for Behavioral Research, Center for Family Research, University of Georgia

Gary W. Evans, Department of Human Development, Cornell University

Steven R. H. Beach, Department of Child and Family Development, University of Georgia

Michael Windle, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health, Emory University.

Ronald L. Simons, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia

Meg Gerrard, Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth College.

Frederick X. Gibbons, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Dartmouth College

Robert A. Philibert, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Adams RE, Santo JB, Bukowski WM. The presence of a best friend buffers the effects of negative experiences. Developmental Psychology. 2012;47:1786–1791. doi: 10.1037/a0025401. doi:10.1037/a0025401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52:317–332. doi: 10.1007/BF02294359. [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Klibourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education. 2002;31:101–119. doi:10.1080/0305724022014322. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Ogliari A, Zanoni A, Citterio A, Pozzoli U, Giorda R, Marino C. Influence of the serotonin transporter promoter gene and shyness on children’s cerebral responses to facial expressions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.85. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Wells TT, Ellis AJ, McGeary JE. Association of the serotonin transporter gene promoter region (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism with biased attention for emotional stimuli. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:670–681. doi: 10.1037/a0016198. doi:10.1037/a0016198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett GG, Merritt MM, Sollers JJ, III, Edwards CL, Whitfield KE, Brandon DT, Tucker RD. Stress, coping, and health outcomes among African-Americans: A review of the John Henryism hypothesis. Psychology and Health. 2004;19:369–383. doi:10.1080/0887044042000193505. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR. What do we really know about Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:71–83. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00010. Retrieved from http://www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/content/64/1/71.abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Rock SL, Caldwell BM, Harris PT, Hamrick HM. Home environment and school performance among Black elementary school children. Journal of Negro Education. 1987;56:499–509. doi:10.2307/2295348. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SL, Dodelzon K, Sandhu HK, Philibert RA. Relationship of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and haplotypes to mRNA transcription. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2005;136:58–61. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30185. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Javaras KN, Blacker D, Murphy JM, Normand S-LT. Differential item functioning between ethnic groups in the epidemiological assessment of depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196:297–306. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816a490e. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e31816a490e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kessler RC. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:317–327. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003514. doi:10.1017/S0033291704003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SRH, Chen Y.-f., Obasi E, Philibert RA, Kogan SM, Simons RL. Perceived discrimination, serotonin transporter linked polymorphic region status, and the development of conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:617–627. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000046. doi:10.1017/S0954579411000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Beach SRH, Philibert RA, Chen Y.-f., Murry VM. Prevention effects moderate the association of 5-HTTLPR and youth risk behavior initiation: Gene × environment hypotheses tested via a randomized prevention design. Child Development. 2009;80:645–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01288.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y.-f., Kogan SM. A cascade model connecting life stress to risk behavior among rural African American emerging adults. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:667–678. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000350. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y.-f., Kogan SM, Smith K, Brown AC. Buffering effects of a family-based intervention for African American emerging adults. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:1426–1435. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00774.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y.-f., Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent African American families. Child Development. 1998;69:803–816. doi:10.2307/1132205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X. Linking parenting processes and self-regulation to psychological functioning and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:82–94. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.82. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger RD, Gibbons FX, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Simons RL. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72:1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Kim SY, Murry VM, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Conger RD. Neighborhood disadvantage moderates associations of parenting and older sibling problem attitudes and behavior with conduct disorders in African American children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:211–222. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.211. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kim S, Murry VM, Brown AC. Protective longitudinal paths linking child competence to behavioral problems among African American siblings. Child Development. 2004;75:455–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00686.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair LD, Neubaum-Carlan E. The Strong African American Families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, McNair LD, Chen Y.-f., Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Wills TA. Linking changes in parenting to parent-child relationship quality and youth self-control: The Strong African American Families program. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:47–69. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00086.x. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Sigel IE. Methods of family research: Biographies of research projects. Vol. 2. Clinical populations. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic sensitivity to the environment: The case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:509–527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Blender JA. A multiple-levels-of-analysis perspective on resilience: Implications for the developing brain, neural plasticity, and preventive interventions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1094:248–258. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.029. doi:10.1196/annals.1376.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Gunnar MR, Toth SL. The differential impacts of early physical and sexual abuse and internalizing problems on daytime cortisol rhythm in school-aged children. Child Development. 2010;81:252–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01393.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescent depression. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt LM, editors. Handbook of depression in adolescents. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; New York, NY: 2009. pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]