Abstract

Genetic admixture in human, the result of inter-marriage among people from different well-differentiated populations, has been extensively studied in the New World, where European colonization brought contact between peoples of Europe, Africa, and Asia and the Amerindian populations. In Asia, genetic admixing has been also prevalent among previously separated human populations. However, studies on admixed populations in Asia have been largely underrepresented in similar efforts in the New World. Here, I will provide an overview of population genomic studies that have been published to date on human admixture in Asia, focusing on population structure and population history.

Keywords: admixture mapping, genetic admixture, local adaptation, population structure

Introduction

Before I review the recent research progress on Asian admixed populations, I would like to first give some overview of the background of admixture studies, especially in the context of population genomics, since admixture analysis is only feasible when individual genomic data are available.

Genetic Structure of Admixed Populations

Human migration resulted in population differentiation, and many populations, especially those living in different continents, have been isolated for quite a long time. However, subsequent migrations that have occurred over the past millennia have resulted in gene flow between previously separated human subpopulations. This has been a common phenomenon throughout the history of modern humans, as previously isolated populations often come into contact through colonization and migration. As a result, admixed populations came into being when previously mutually isolated populations met and inter-married. It is important to conduct a full analysis of genetic structure and characterize the genetic make-up of admixed populations. On the one hand, this will shed light on human genetic history; on the other hand, increased population admixture influences genome heterozygosity, which in turn will affect phenotypes relevant to health; thus, genetic admixture has many implications in medical research.

Admixture Mapping

The estimation of genetic admixture in human populations has been used for a variety of purposes, ranging from the confirmation of historical events, such as population of the effects of other biological parameters, but the emphasis in early studies was on gene mapping of continuous traits. Admixture mapping is a method for localizing disease-causing genetic variants that differ in frequency across populations. This approach was proposed by McKeigue in 1998 [1]; it is based on the association of local chromosomal ancestry with the disease, to test for the linkage of the disease or trait with parental ancestry at each locus, defined as 0, 1, or 2 allele copies inherited from the ancestral populations. However, the idea of using genetic architecture in admixed genomes to locate disease-associated genes was actually first proposed by Rife in 1954 [2], although the original idea was to use the admixture linkage disequilibrium (ALD) generated in recently admixed human populations to assign the traits to linkage groups.

Admixture of populations often leads to extended linkage disequilibrium (LD), which could greatly facilitate the mapping of human disease genes [3-6]. Gene mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium (MALD) has been shown to have special value theoretically [4, 7-14] and empirically [15-29]. MALD has received much attention recently [3, 5]. The initial attraction of MALD was its significantly increased extension of LD (or extended LD) in admixed populations, which requires far fewer markers in mapping disease genes. Previous studies predicted that MALD typically requires only 2,000-3,000 ancestry informative markers (AIMs) for a genomewide search [1, 16]. The utility of MALD depends upon how far LD extends over a chromosomal interval, which, in turn, dictates the spacing and number of markers required for a genomewide scan. Therefore, it is imperative to characterize the magnitude and extent of ALD in the admixed population in which MALD will be performed.

Stephens et al. [10] showed that ALD in African-Americans (AfAs) could exist up to 10 cM, even after 9 generations by simulation. Parra et al. [30] reported strong LD between the FY-null and AT3 loci, which are 22 cM apart on chromosome 1q22. Substantially extended LD in AfA populations were reported in several regions or chromosomes [31-33] using primarily short tandem repeat markers. Patterson et al. [12] showed that strong ALD extends to 17 cM on average in AfAs. Contrarily, it was also reported that the LD in AfA populations is shorter than or similar to those seen in non-admixed populations using single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)-detectable to about 44 kb or larger [34]. The contradicting observations might be due to the selection of the markers based on their allele frequency difference between the parental populations, as shown theoretically by Chakraborty and Weiss [7]. It is therefore important to examine empirically the relationship of LD in the admixed population and allele frequency difference between parental populations. In fact, there have been many studies that have investigated LD patterns in recent admixed populations, such as the AfAs, Mexicans, and Hispanics. In Asia, the only study published so far is on the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, China [35].

In practice, the principle of admixture mapping, proposed by McKeigue [1], is a little different from that of MALD, because it is based on the association of local chromosomal ancestry with the disease rather than on LD between the marker and phenotype, but the information and essence are the same. It is most advantageous to apply this approach to populations that have descended from a recent mix of two ancestral groups that have been geographically isolated for many tens of thousands of years, providing new insights into population history and genotype-phenotype relationships. With the efforts of many scientists in this field, statistical methods, panels of AIMs for admixture typing, and software programs have been rapidly developed; in addition, recent advances in genotyping and sequencing technologies have facilitated genomewide investigation of human genetic variations. Admixture mapping has been applied to a wide range of traits and diseases, for which it is hypothesized that the differences in disease rates across populations are due to population-specific frequency differences of the causal variant(s).

Ancestry Informative Markers

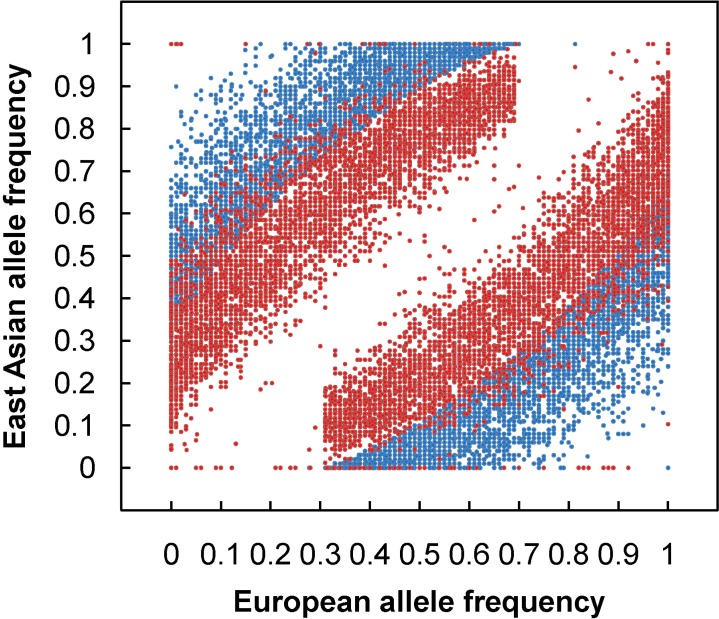

To apply admixture mapping, a set of genetic markers called AIMs, provide information at each locus of the ancestral origin of the allele. An AIM is a polymorphic locus that exhibits substantially different allele frequencies between the ancestral populations, which are often from different geographical regions. For example, Fig. 1 shows an allele frequency distribution of 9,781 AIMs screened from genomewide SNPs from European (EUR) and East Asian (EAS) populations. With a set of AIMs, one can estimate the geographical origins of the ancestors of an individual and ascertain what proportion of the ancestry is derived from each geographical region. The primary utility of estimates of continental ancestry using AIMs is to control for confounding from population stratification in genetic association studies among unrelated individuals from admixed populations. Population admixture has the potential to lead to confounding results from population stratification in genetic association studies, leading to both false positive (type I error) and false negative (type II error) results [36-39]. Now, to facilitate the application of admixture mapping, a number of high-density mapping panels have been constructed, Such panels are already available for disease gene discovery in AfAs [16, 21, 40, 41], Hispanics/Latinos [23, 26, 40], Mexican-Americans (the largest subgroup of Hispanic/Latinos) [28, 41], and Uyghurs [35].

Fig. 1.

European and East Asian allele frequencies for the 9,781 ancestry informative markers. Blue dots indicate allele frequency of European and East Asian populations. Red dots indicate allele frequency of an admixed population from Xinjiang.

Local Adaptation of Admixed Populations

Identifying targets of positive selection in humans has been a central topic in human evolutionary and population genetics. Traditional studies have been relying on the analysis of individual candidate genes. Since the genomics era, the availability of high-density SNPs has provided essential resources for systematically interrogating the entire genome for detecting signatures of natural selection. As a matter of fact, many genomewide scans for recent or ongoing positive selection have been recently performed in humans, while most of the studies to date have been performed in non-admixed populations. In the situation of genetic admixture, when previously isolated populations meet and mix, the resulting admixed population can benefit from several genetic advantages, including increased genetic variation, the creation of novel genotypes, and the masking of deleterious mutations, and these admixture benefits are thought to play an important role in biological adaptation to local environment. As a result, this has led to the use of admixture estimates to detect the action of natural selection in human populations. Such techniques have been regarded as powerful methods for the detection of selection effects, especially when an appreciable number of generations have elapsed since the original admixture.

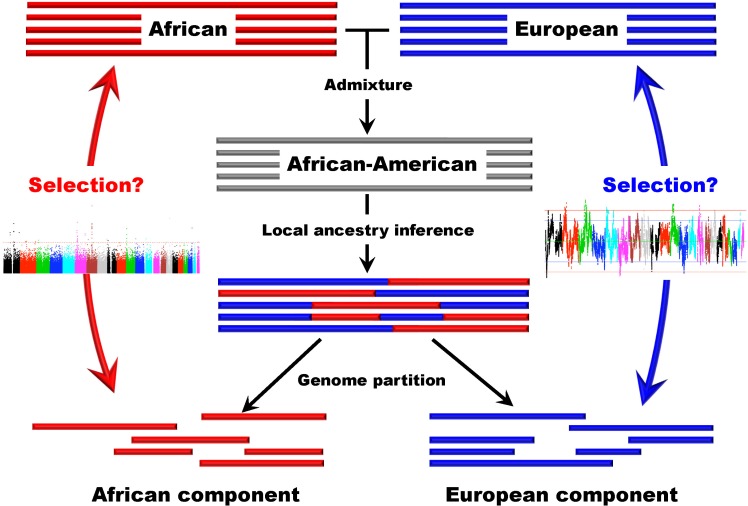

Several studies based on genomic data have been conducted in recently admixed populations in the New World [42-44]. Recently, we developed a new approach that can be used to detect natural selection both before and after population admixture, and we applied this method in AfA data. It is particularly meaningful to investigate natural selection in AfAs due to the high mortality their African ancestry has experienced in history. In this study, we examined 491,526 autosomal SNPs genotyped in 5,210 individuals and conducted a genomewide search for selection signals in 1,890 AfAs. Several genomic regions showing excess African or EUR ancestry, which were thought of as the footprints of selection since population admixture, were detected based on a commonly used approach. However, we also developed a new strategy to detect natural selection both pre- and post-admixture by reconstructing an ancestral African population (AAF) from inferred African components of ancestry in AfAs and comparing it with indigenous African populations (IAF). Interestingly, many selection candidate genes identified by the new approach were associated with AfA-specific high-risk diseases, such as prostate cancer and hypertension, suggesting an important role that these disease-related genes might have played in adapting to a new environment. CD36 and HBB, whose mutations confer a degree of protection against malaria, were also located in the highly differentiated regions between AAF and IAF. Further analysis showed that the frequencies of alleles protecting against malaria in AAF were lower than that in IAF, which is consistent with the relaxed selection pressure of malaria in the New World. There is no overlap between the top candidate genes detected by the 2 approaches, indicating the different environmental pressures AfAs experienced pre- and post-population admixture. We suggest that the new approach (see Fig. 2 for a schematic framework of this approach) is reasonably powerful and can also be applied to other admixed populations, such as Latinos and Uyghurs.

Fig. 2.

A schematic framework for detecting natural selection in African-American populations based on admixture analysis.

I will not go further on this topic in this review paper, since so far there is no study that has been performed in Asian populations using admixture analysis. However, we believe that the discoveries have greatly enriched our understanding of human origins and history and hold large potential for identifying genes with important biological functions; this, in turn, will elucidate the genetic basis of some human diseases [45, 46]. These studies together provide many new insights into the natural selection process and mechanisms, which will ultimately improve the modern evolution theory.

Population Admixture Dynamics

Human diasporas over the past millennia have resulted in even more frequent intercontinental marriages and population admixtures. Many recently admixed populations, such as AfAs and Mestizos, have received much attention due to their potential advantages in the discovery of disease-associated genes. Particularly, a disease gene mapping strategy, named admixture mapping or MALD, as aforementioned, has been developed [1, 7, 11, 47]. The statistical power of admixture mapping or MALD relies on the fact that population admixture creates extended and elevated LD between loci with different allele frequencies among the parental source populations [7, 10, 48], while the historical population admixture processes determine the LD pattern in an admixed population. Therefore, as shown in several theoretical and simulation studies, population admixture dynamics have a strong effect on the power of admixture mapping [48-51].

In fact, accurate understanding of population admixture dynamics is important not only to admixture mapping but also to other applications, such as elucidating population history [52] and detecting natural selection signatures in admixed populations [49, 53]. However, the fine admixture dynamics of recently admixed populations has not been well established, even though some studies have examined the simulated data [54, 55] or experimental data with sparse markers [48, 51]. In addition, admixture dynamics of relatively ancient admixed populations has rarely been studied. Recently, the availability of genomewide high-density SNPs data has facilitated the study on detailed genetic structures of admixed populations [35, 44, 56-61]. However, most of these studies relied on simplified models that do not take into account the inherent complexity of the admixture processes. Moreover, the haplotype and chromosomal segment patterns shaped by recombination within each individual have been deliberately ignored in most studies due to many inherent challenges [62].

For individuals from admixed populations that have existed for a long time, their chromosomes resemble a mosaic of chromosomal segments of distinct ancestry (CSDA). The CSDA in the admixed population would have been reshaped and rearranged by recombination in each generation, which should provide some information about the population history. In other words, the CSDA will be spliced into smaller pieces as the number of generations since admixture increases, while the chromosomes from recently admixed individuals contain much longer CSDAs. Information regarding the average CSDA length has been used to infer the number of generations since admixture in various studies [57, 63-66]. However, the distribution of CSDA length may contain more valuable information concerning population admixture history and admixture dynamics, which has not yet been explored.

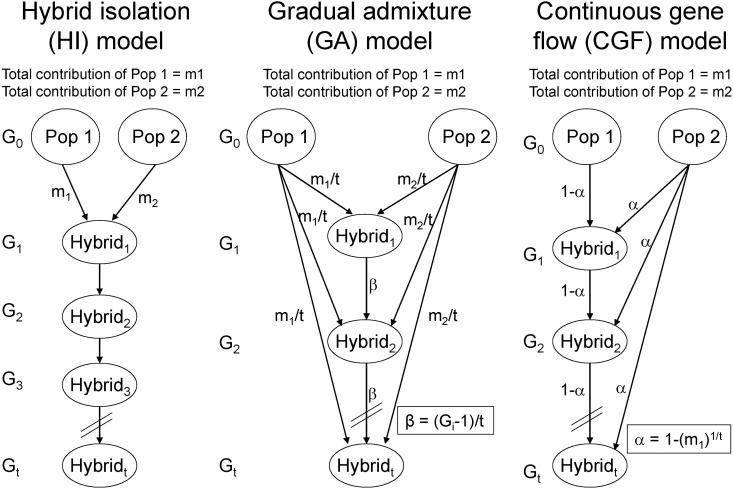

In a recent study [67], we proposed 2 approaches to explore population admixture dynamics and, by analyzing genomewide empirical and simulated data, demonstrated that the approach based on the distribution of CSDA was more powerful than that based on the distribution of individual ancestry proportions. As a result, analysis of 1,890 AfAs showed that a continuous gene flow (CGF) model (Fig. 3), in which AfAs continuously received gene flow from EUR populations over about 14 generations, best explained the admixture dynamics of AfAs among several putative models. Interestingly, we observed that some AfAs had much more EUR ancestry than the simulated samples, indicating substructures of local ancestries in AfAs that could have been caused by individuals from some particular lineages having continuously inter-married with people of EUR ancestry. On the contrary, the admixture dynamics of Mexicans was more likely to be explained by a gradual admixture (GA) model (Fig. 3), in which Mexicans continuously received gene flow from both EUR and Amerindian populations for about 24 generations. The higher proportion of long CSDAs observed in Mexican-Americans relative to Mexican-Mestizos suggested recent gene flow from EUR-Americans to Mexican-Americans. The genetic components of sub-Saharan Africans in Middle Eastern populations, such as Mozabite, Bedouin, and Palestinians, could be explained by one early admixture followed by some recent gene flow from Africans. In summary, this study not only provides new approaches to explore population admixture dynamics but also advances our understanding on historical admixture processes of AfAs, Mexicans, and Middle Eastern populations.

Fig. 3.

Typical admixture models. HI model and CGF model were adapted from Long [49], GA model was adapted from Ewens and Spielman [50]. In each model, the genetic contributions of Pop1 and Pop2 are m1 and m2, respectively. The admixed population experienced Gi generations, which range from 1 to t generations.

Again, since admixed populations in Asia have not been studied, I will not go further into details. This approach can be also applied in admixed populations in Asia to explore the admixture dynamics of admixed populations in Asia.

Genetic Structure and History of Admixed Populations in Different Geographical Regions

In the following, I will review the studies on population admixture in different geographical regions in Asia-i.e., East Asia, Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

Population Admixture in East Asia

In East Asia, most of the populations that have been studied are thought to be relatively homogeneous. Most people identify themselves with one particular ethnic group, but in fact, we are highly mixed. A report from the HUGO PanAsia SNP Consortium, which was published in Science in 2009 [68], revealed a picture of prevalent gene flow among Asian populations. As a collaborative effort of 93 scientists from 10 countries, this study conducted the first large-scale and genomewide study on the genetic diversity of 73 Asian populations, representing a broad geographic sample of the major ethnic groups and linguistic families in Asia.

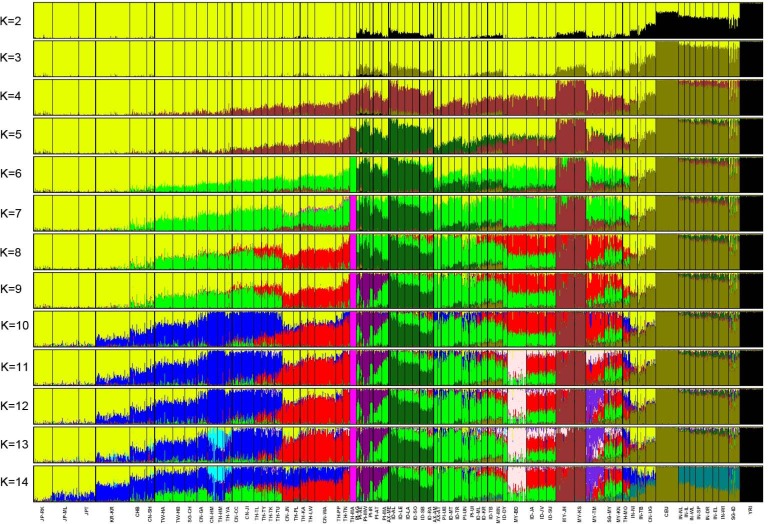

Considerable gene flow among Asian populations was observed amongst sub-populations in these clusters, including those groups believed to practice endogamy based on linguistic, cultural, and ethnic information. In fact, most populations studied show evidence of admixture in population structure analyses. For example, the Han Chinese have grown to become the largest ethnic group today, in a demographic expansion that has occurred mostly within historical times. The analysis in this study reveals that the 6 Han Chinese populations show varying degrees of admixture (Fig. 4) between a northern 'Altaic' cluster and a 'Sino-Tibetan/Tai-Kadai' cluster, which is most frequent in the ethnic groups sampled from southern China and northern Thailand. Finally, most of the Indian populations showed evidence of shared ancestry with EUR populations, which is consistent with our understanding of the expansion of Indo-EUR speaking populations (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Estimated population structure. Each individual is represented by a thin vertical line, which is partitioned by STRUCTURE into K colored segments representing estimated membership fractions in each K cluster. Black lines separate individuals of different populations. Populations are labeled below the figure. All population IDs except the 4 HapMap samples (YRI, CEU, CHB, and JPT) are denoted by 4 characters. The first 2 letters indicate the country where the samples were collected or (in the case of Affymetrix) genotyped according to the following convention: AX, Affymetrix; CN, China; ID, Indonesia; IN, India; JP, Japan; KR, Korea; MY, Malaysia; PI, Philippines; SG, Singapore; TH, Thailand; TW, Taiwan. The last 2 letters are unique IDs for the population. Populations from the same linguistic group or neighboring geographic locations tend to share the same cluster. At K = 14, each language family can be specified by a cluster (color), although Sino-Tibetan-speaking populations tend to cluster with both Altaic- and Tai-Kadai-speaking populations. The figure shown for a given K is based on the highest probability run of 10 STRUCTURE runs at that K.

Population Admixture in Central Asia

Many human populations that settled in Central Asia demonstrate an array of mixed anthropological features of East Eurasians (EEA) and West Eurasians (WEA), indicating a possible scenario of biological admixture between already differentiated EEA and WEA populations. However, their complex biological origin and genomic make-up, as well as their genetic interaction with surrounding populations, are not well understood. Despite Central Asia being a vast territory that has been crucial in human history due to its strategic location [69], populations in this region are not on the list of the 2 large-scale international collaborative efforts, such as the International HapMap Project [70] and the 1000 Genome Project [71], and population genomic studies on Central Asian populations have been largely underrepresented in similar efforts worldwide [68, 72-76].

In an attempt to decipher the genetic structure and population history in Central Asia, we conducted, to our knowledge, the first genomewide studies of the Uyghur residing in Xinjiang, which is geographically located in Central Asia. Uyghur that settled in Xinjiang of China (UIG) is a population presenting a typical admixture of eastern and western anthropometric traits; we dissected its genomic structure at the population level, individual level, and chromosome level using 20,177 SNPs spanning over almost the entire chromosome 21. Our results showed that UIG was formed by two-way admixture, with 60% of ancestry from EUR and 40% of ancestry from EAS. Overall LD in UIG was similar to that in its parental populations, represented by EAS and EUR for common alleles, and UIG manifested elevation of LD only within 500 kb and at a level of 0.1 < r2 < 0.8 when AIMs were used. The size of chromosomal segments that were derived from EASs and EURs was on average 2.4 cM and 4.1 cM, respectively. Both the magnitude of LD and fragmentary ancestral chromosome segments indicated a long period of history of Uyghur. Under the assumption of a hybrid isolation (HI) model, the admixture event of UIG was estimated to have taken place about 126 (107-146) generations, or 2,520 (2,140-2,920) years ago, assuming 20 years per generation. In spite of the long history and short LD of Uyghur compared with recent admixture populations, such as African-Americans, we suggested that MALD is still applicable in Uyghur, except that about 10-fold AIMs are necessary for a whole-genome scan.

Later in the same year, following up on our previous study, we conducted a genomewide analysis of admixture for 2 Uyghur population samples (HGDP-UG and PanAsia-UG) collected from northern and southern Xinjiang of China, respectively. Both HGDP-UG and PanAsia-UG showed substantial admixture of EAS and EUR ancestries, with an empirical estimation of ancestry contribution of 53:47 (EAS:EUR) and 48:52 for HGDP-UG and PanAsia-UG, respectively. The effective admixture time under a model with a single pulse of admixture was estimated to be 110 generations and 129 generations; i.e., admixture events occurred about 2,200 years and 2,580 years ago for HGDP-UG and PanAsia-UG, respectively, assuming an average of 20 years per generation. Despite their earlier history versus other admixture populations, such as AfAs and Latinos, admixture mapping, an economical and powerful approach for localizing disease genes, holds equal promise for Uyghurs because of their mixture of ancestry from different continents as well as their large population size. We screened multiple databases and identified a genomewide SNP panel that can distinguish EAS and EUR ancestry of chromosomal segments in Uyghurs. The panel contains 8,150 AIMs showing large frequency differences between EAS and EUR (FST > 0.25, mean FST = 0.43) but little frequency difference (7,999 AIMs validated) within both EAS and EUR populations (FST < 0.05, mean FST < 0.01). We evaluated the effectiveness of this admixture map for localizing disease genes in 2 Uyghur populations. Our map constitutes the first practical resource for admixture mapping in Uyghurs, and it will enable studies of diseases showing different genetic risks in European and EAS populations.

Population Admixture in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, together with the Island Pacific region, is a cultural melting pot of migrating Neolithic farmers and indigenous Mesolithic hunter-gatherer communities. On the basis of increased cultural, linguistic, and genetic diversity, the origins of Southeast Asian populations are thought to be more complex than those to their north. Two major prehistoric movements of people had great influence on the linguistic, cultural, and genetic diversity of the region. The first colonization of modern humans in the region was around 45,000 years before the present [77], which could have brought the ancestors of modern Papuans and Australians into the region [78]. Notably, archaeological evidence has confirmed human habitation in Eastern Indonesia as far back as 32,000 years ago [79]. The second major human migration event, which is often termed the Austronesian expansion, was relatively recent, coinciding with the first agricultural settlements in Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) [80]; it is often putatively linked to demic dispersal from mainland China during the Mid-Holocene [81], and based on linguistic studies, the Austronesian expansion is proposed to have originated in Taiwan around 5,000-6,000 years ago and spread to Southeast Asia, Near and Remote Oceania, and Madagascar [82, 83]. However, our knowledge about the historical origin and spread of Austronesian-speaking peoples has been overwhelmingly from linguistic, archeological, and anthropological studies, while contributions from genetic studies are limited, and especially, genetic dating of the expansion time of Austronesians is almost absent [84].

Undoubtedly, the Austronesian expansion has had a major cultural influence on Asia-Pacific pre-history. The biological contribution of Austronesian-speaking peoples to the pre-existing local populations in ISEA was first noted by Wallace in 1869 [85]. As Wallace observed, people in the region between mainland Asia and New Guinea in the west are similar to their neighbors in mainland Southeast Asia, while the eastern groups near New Guinea are similar to Melanesians, leaving intervening populations intermediate in appearance [85]. This admixture pattern was revealed by mtDNA and non-recombining region of the Y chromosome (NRY) studies [86, 87] as well as by a recent study [81] based on multiple autosomal and X-chromosomal SNPs.

The genetic admixture with local populations during the Austronesian expansion could provide a unique opportunity to shed light on the migration history of Austronesian-speaking people. However, previous studies based on haploid genomes could not study admixture at the individual level. Studies of multiple loci of the nuclear genome are more powerful [88] in studying admixture at the individual level, but the sparse low-density loci examined in previous genomewide studies do not allow estimation of the admixture time, which relies on recombination information extracted from high-density genomewide data.

We analyzed dense genomewide SNP data from 2 studies [68, 89]. The first consists of about 50,000 SNPs analyzed in 288 individuals from 13 Austronesian-speaking populations and 2 Papuan-speaking populations across Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, while the second consists of about 680,000 SNPs analyzed in 36 individuals from 7 populations from Indonesia and 25 individuals from New Guinea. Apart from a general description of population structure and its relationship with geography, language, and demographic history, we focus on estimating the amount and time of admixture involving Asian and Papuan ancestry across E. Indonesia to test the various scenarios that might explain the admixture history. Because genetic recombination breaks down parental genomes into segments of different sizes, the genome of a descendant of an admixture event is composed of different combinations of these ancestral segments, or 'blocks' [90]. Admixture time can be estimated from the information based on distribution of ancestral segments and the recombination breakpoints in an admixed genome [34, 57, 63, 66, 90]. In this study, we assume that a cline of admixture times that decreases from west to east across E. Indonesia would support a scenario of incoming Asians admixing with indigenous Papuan groups, while a cline in the opposite direction would indicate incoming Papuans admixing with resident Asians. Moreover, the actual admixture times would indicate when the migration occurred. Our approach is thus to estimate population admixture time by taking advantage of available genomewide data of both E. Indonesian populations showing admixture and their ancestry reference populations.

In summary, the admixture time analysis of 2 different datasets provides compelling evidence that people of Asian ancestry began moving through E. Indonesia about 4,000 years ago, from west to east, and admixed with resident groups of Papuan ancestry. Furthermore, this scenario is in excellent agreement with linguistic and archeological evidence for a pre-Austronesian presence of Papuans in E. Indonesia [91, 92] and for an eastward spread of Austronesian-speaking farmers across E. Indonesia [82, 83]. Our analyses thus refute suggestions that the Asian ancestry observed in Indonesia largely predates the Austronesian expansion [93, 94]. Instead, our analyses of genomewide data indicate that there was a strong and significant genetic impact associated with the Austronesian expansion in Indonesia, just as similar analyses have pointed to a strong and significant genetic impact associated with the Austronesian expansion through Near and Remote Oceania [87, 95, 96]. Given that admixture among human populations (and between modern and archaic humans) is increasingly being recognized as a significant aspect of modern human biology [97], estimates of the time of admixture should provide important new insights into the history of our species.

Population Admixture in South Asia

All the published results in this area so far have been focused on populations in India. There were recently 2 studies on the Siddis, which are a group of people showing evident genetic admixture in India. The Siddis (Afro-Indians) are a tribal population whose members live in coastal Karnataka, Gujarat, and some parts of Andhra Pradesh. Historical records indicate that the Portuguese brought the Siddis to India from Africa about 300-500 years ago; members of this population are believed to be descendants of the Bantu-speaking population of Africa. However, there is little information about their more precise ancestral origins. One Indian group, led by Dr. Mukerji, studied this population [98] based on genomewide SNP data generated using Affymetrix 50K chips. The authors carried out this study by using a set of 18,534 autosomal markers common between Indian, CEPH-HGDP, and HapMap populations. Principal components analysis clearly revealed that the African-Indian population derived its ancestry from Bantu-speaking west African as well as Indo-European-speaking north and northwest Indian population(s). STRUCTURE and ADMIXTURE analyses show that overall, the OG-W-IPs derived 58.7% of their genomic ancestry from their African past and have very little inter-individual ancestry variation (8.4%). The extent of LD also reveals that the admixture event has been recent. Functional annotation of genes encompassing the AIMs that are closer in allele frequency to the Indian ancestral population revealed significant enrichment of biological processes, such as ion channel activity, and cadherins. They briefly examined the implications of determining the genetic diversity of this population, which could provide opportunities for studies involving admixture mapping.

The second group, led by Dr. Thangaraj, performed a genomewide survey to understand the population history of the Siddis [99]. Using hundreds of thousands of autosomal markers, they showed that the Siddis inherited ancestry from Africans, Indians, and possibly Europeans (Portuguese). Additionally, analyses of the uniparental (Y-chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA) markers indicate that the Siddis trace their ancestry to Bantu speakers from sub-Saharan Africa. They estimated that the admixture between the African ancestors of the Siddis and neighboring South Asian groups probably occurred in the past 8 generations (-200 years ago), consistent with historical records.

Perspective

Recent advances in genotyping and sequencing technologies have facilitated genomewide investigation of human genetic variations and provided new insights into population structure and admixture history. Admixed populations are attracting more and more attention from both evolutionary and medical studies as well as from the other fields. Without understanding the genetic structure and history of admixed populations well, our knowledge about human genetics would not be complete. Unfortunately, studies on admixed populations in Asia are so far very limited, although gene flow among Asian populations is prevalent [68]. The studies published and mentioned in this review have been focused on investigating the genetic structure and genetic history of a limited number of well-known admixed populations in Asia. Further efforts should be made to reveal local adaptation signatures and also apply admixture mapping in those well-known admixed populations; in the future, more powerful methods are expected to be developed and applied to many more populations with longer histories and more complex admixture scenarios.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grants 31171218 and 30971577, by the Shanghai Rising-Star Program 11QA-1407600, and by the Science Foundation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) (KSCX2-EW-Q-1-11; KSCX2-EW-R-01-05; KSCX2-EW-J-15-05). This research was supported in part by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MoST) International Cooperation Base of China. Shuhua Xu is Max-Planck Independent Research Group Leader and member of CAS Youth Innovation Promotion Association. Shuhua Xu also gratefully acknowledges the support of the National Program for Top-notch Young Innovative Talents and the support of the K.C. Wong Education Foundation, Hong Kong.

References

- 1.McKeigue PM. Mapping genes that underlie ethnic differences in disease risk: methods for detecting linkage in admixed populations, by conditioning on parental admixture. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:241–251. doi: 10.1086/301908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rife DC. Populations of hybrid origin as source material for the detection of linkage. Am J Hum Genet. 1954;6:26–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKeigue PM. Prospects for admixture mapping of complex traits. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:1–7. doi: 10.1086/426949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reich D, Patterson N. Will admixture mapping work to find disease genes? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:1605–1607. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith MW, O'Brien SJ. Mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium: advances, limitations and guidelines. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:623–632. doi: 10.1038/nrg1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seldin MF. Admixture mapping as a tool in gene discovery. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty R, Weiss KM. Admixture as a tool for finding linked genes and detecting that difference from allelic association between loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:9119–9123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Risch N. Mapping genes for complex diseases using association studies with recently admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet Suppl. 1992;51:13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briscoe D, Stephens JC, O'Brien SJ. Linkage disequilibrium in admixed populations: applications in gene mapping. J Hered. 1994;85:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephens JC, Briscoe D, O'Brien SJ. Mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium in human populations: limits and guidelines. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:809–824. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKeigue PM. Mapping genes underlying ethnic differences in disease risk by linkage disequilibrium in recently admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:188–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson N, Hattangadi N, Lane B, Lohmueller KE, Hafler DA, Oksenberg JR, et al. Methods for high-density admixture mapping of disease genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:979–1000. doi: 10.1086/420871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X, Cooper RS, Elston RC. Linkage analysis of a complex disease through use of admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1136–1153. doi: 10.1086/421329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu X, Zhang S, Tang H, Cooper R. A classical likelihood based approach for admixture mapping using EM algorithm. Hum Genet. 2006;120:431–445. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0224-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oksenberg JR, Barcellos LF, Cree BA, Baranzini SE, Bugawan TL, Khan O, et al. Mapping multiple sclerosis susceptibility to the HLA-DR locus in African Americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:160–167. doi: 10.1086/380997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MW, Patterson N, Lautenberger JA, Truelove AL, McDonald GJ, Waliszewska A, et al. A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in African Americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1001–1013. doi: 10.1086/420856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich D, Patterson N, De Jager PL, McDonald GJ, Waliszewska A, Tandon A, et al. A whole-genome admixture scan finds a candidate locus for multiple sclerosis susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1113–1118. doi: 10.1038/ng1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu X, Luke A, Cooper RS, Quertermous T, Hanis C, Mosley T, et al. Admixture mapping for hypertension loci with genome-scan markers. Nat Genet. 2005;37:177–181. doi: 10.1038/ng1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shriver MD, Mei R, Bigham A, Mao X, Brutsaert TD, Parra EJ, et al. Finding the genes underlying adaptation to hypoxia using genomic scans for genetic adaptation and admixture mapping. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;588:89–100. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-34817-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang H, Jorgenson E, Gadde M, Kardia SL, Rao DC, Zhu X, et al. Racial admixture and its impact on BMI and blood pressure in African and Mexican Americans. Hum Genet. 2006;119:624–633. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian C, Hinds DA, Shigeta R, Kittles R, Ballinger DG, Seldin MF. A genomewide single-nucleotide-polymorphism panel with high ancestry information for African American admixture mapping. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:640–649. doi: 10.1086/507954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barnes KC, Grant AV, Hansel NN, Gao P, Dunston GM. African Americans with asthma: genetic insights. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:58–68. doi: 10.1513/pats.200607-146JG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao X, Bigham AW, Mei R, Gutierrez G, Weiss KM, Brutsaert TD, et al. A genomewide admixture mapping panel for Hispanic/Latino populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1171–1178. doi: 10.1086/518564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Marignac VL, Valladares A, Cameron E, Chan A, Perera A, Globus-Goldberg R, et al. Admixture in Mexico City: implications for admixture mapping of type 2 diabetes genetic risk factors. Hum Genet. 2007;120:807–819. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton HL, Kittles RA, Parra E, McKeigue P, Mao X, Cheng K, et al. Genetic evidence for the convergent evolution of light skin in Europeans and East Asians. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:710–722. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Price AL, Patterson N, Yu F, Cox DR, Waliszewska A, McDonald GJ, et al. A genomewide admixture map for Latino populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1024–1036. doi: 10.1086/518313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reich D, Patterson N, Ramesh V, De Jager PL, McDonald GJ, Tandon A, et al. Admixture mapping of an allele affecting interleukin 6 soluble receptor and interleukin 6 levels. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:716–726. doi: 10.1086/513206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian C, Hinds DA, Shigeta R, Adler SG, Lee A, Pahl MV, et al. A genomewide single-nucleotide-polymorphism panel for Mexican American admixture mapping. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1014–1023. doi: 10.1086/513522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wassel Fyr CL, Kanaya AM, Cummings SR, Reich D, Hsueh WC, Reiner AP, et al. Genetic admixture, adipocytokines, and adiposity in Black Americans: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Hum Genet. 2007;121:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0353-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parra EJ, Marcini A, Akey J, Martinson J, Batzer MA, Cooper R, et al. Estimating African American admixture proportions by use of population-specific alleles. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1839–1851. doi: 10.1086/302148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lautenberger JA, Stephens JC, O'Brien SJ, Smith MW. Significant admixture linkage disequilibrium across 30 cM around the FY locus in African Americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:969–978. doi: 10.1086/302820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rybicki BA, Iyengar SK, Harris T, Liptak R, Elston RC, Sheffer R, et al. The distribution of long range admixture linkage disequilibrium in an African-American population. Hum Hered. 2002;53:187–196. doi: 10.1159/000066193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins-Schramm HE, Chima B, Operario DJ, Criswell LA, Seldin MF. Markers informative for ancestry demonstrate consistent megabase-length linkage disequilibrium in the African American population. Hum Genet. 2003;113:211–219. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0961-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu S, Jin L. A genome-wide analysis of admixture in Uyghurs and a high-density admixture map for disease-gene discovery. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:322–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lander E, Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet. 1995;11:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Risch N, Merikangas K. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science. 1996;273:1516–1517. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khoury MJ, Yang Q. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases: an epidemiologic perspective. Epidemiology. 1998;9:350–354. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199805000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang H, Quertermous T, Rodriguez B, Kardia SL, Zhu X, Brown A, et al. Genetic structure, self-identified race/ethnicity, and confounding in case-control association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:268–275. doi: 10.1086/427888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith MW, Lautenberger JA, Shin HD, Chretien JP, Shrestha S, Gilbert DA, et al. Markers for mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium in African American and Hispanic populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1080–1094. doi: 10.1086/323922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins-Schramm HE, Phillips CM, Operario DJ, Lee JS, Weber JL, Hanson RL, et al. Ethnic-difference markers for use in mapping by admixture linkage disequilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:737–750. doi: 10.1086/339368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang H, Choudhry S, Mei R, Morgan M, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Burchard EG, et al. Recent genetic selection in the ancestral admixture of Puerto Ricans. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:626–633. doi: 10.1086/520769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basu A, Tang H, Zhu X, Gu CC, Hanis C, Boerwinkle E, et al. Genome-wide distribution of ancestry in Mexican Americans. Hum Genet. 2008;124:207–214. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryc K, Auton A, Nelson MR, Oksenberg JR, Hauser SL, Williams S, et al. Genome-wide patterns of population structure and admixture in West Africans and African Americans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:786–791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909559107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabeti PC, Varilly P, Fry B, Lohmueller J, Hostetter E, Cotsapas C, et al. Genome-wide detection and characterization of positive selection in human populations. Nature. 2007;449:913–918. doi: 10.1038/nature06250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akey JM. Constructing genomic maps of positive selection in humans: where do we go from here? Genome Res. 2009;19:711–722. doi: 10.1101/gr.086652.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montana G, Pritchard JK. Statistical tests for admixture mapping with case-control and cases-only data. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:771–789. doi: 10.1086/425281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pfaff CL, Parra EJ, Bonilla C, Hiester K, McKeigue PM, Kamboh MI, et al. Population structure in admixed populations: effect of admixture dynamics on the pattern of linkage disequilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:198–207. doi: 10.1086/316935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long JC. The genetic structure of admixed populations. Genetics. 1991;127:417–428. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ewens WJ, Spielman RS. The transmission/disequilibrium test: history, subdivision, and admixture. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:455–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parra EJ, Kittles RA, Argyropoulos G, Pfaff CL, Hiester K, Bonilla C, et al. Ancestral proportions and admixture dynamics in geographically defined African Americans living in South Carolina. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001;114:18–29. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200101)114:1<18::AID-AJPA1002>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pool JE, Nielsen R. Inference of historical changes in migration rate from the lengths of migrant tracts. Genetics. 2009;181:711–719. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.098095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams J, Ward RH. Admixture studies and the detection of selection. Science. 1973;180:1137–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4091.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo W, Fung WK. The admixture linkage disequilibrium and genetic linkage inference on the gradual admixture population. Yi Chuan Xue Bao. 2006;33:12–18. doi: 10.1016/S0379-4172(06)60002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verdu P, Rosenberg NA. A general mechanistic model for admixture histories of hybrid populations. Genetics. 2011;189:1413–1426. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.132787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu S, Huang W, Wang H, He Y, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al. Dissecting linkage disequilibrium in African-American genomes: roles of markers and individuals. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2049–2058. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu S, Huang W, Qian J, Jin L. Analysis of genomic admixture in Uyghur and its implication in mapping strategy. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:883–894. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silva-Zolezzi I, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Estrada-Gil J, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Uribe-Figueroa L, Contreras A, et al. Analysis of genomic diversity in Mexican Mestizo populations to develop genomic medicine in Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8611–8616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903045106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu S, Jin W, Jin L. Haplotype-sharing analysis showing Uyghurs are unlikely genetic donors. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:2197–2206. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zakharia F, Basu A, Absher D, Assimes TL, Go AS, Hlatky MA, et al. Characterizing the admixed African ancestry of African Americans. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R141. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-12-r141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bryc K, Velez C, Karafet T, Moreno-Estrada A, Reynolds A, Auton A, et al. Colloquium paper: genome-wide patterns of population structure and admixture among Hispanic/Latino populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(Suppl 2):8954–8961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914618107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu S, Jin L. Chromosome-wide haplotype sharing: a measure integrating recombination information to reconstruct the phylogeny of human populations. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75:694–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–1587. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seldin MF, Morii T, Collins-Schramm HE, Chima B, Kittles R, Criswell LA, et al. Putative ancestral origins of chromosomal segments in individual african americans: implications for admixture mapping. Genome Res. 2004;14:1076–1084. doi: 10.1101/gr.2165904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang H, Coram M, Wang P, Zhu X, Risch N. Reconstructing genetic ancestry blocks in admixed individuals. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:1–12. doi: 10.1086/504302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Price AL, Tandon A, Patterson N, Barnes KC, Rafaels N, Ruczinski I, et al. Sensitive detection of chromosomal segments of distinct ancestry in admixed populations. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jin W, Wang S, Wang H, Jin L, Shuhua X. Exploring population admixture dynamics using empirical and simulated genome-wide distribution of ancestral chromosomal segments. Am J Hum Genet. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.008. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium. Abdulla MA, Ahmed I, Assawamakin A, Bhak J, Brahmachari SK, et al. Mapping human genetic diversity in Asia. Science. 2009;326:1541–1545. doi: 10.1126/science.1177074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Comas D, Plaza S, Wells RS, Yuldaseva N, Lao O, Calafell F, et al. Admixture, migrations, and dispersals in Central Asia: evidence from maternal DNA lineages. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:495–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.International HapMap Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Altshuler D, Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Bentley DR, Chakravarti A, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamaguchi-Kabata Y, Nakazono K, Takahashi A, Saito S, Hosono N, Kubo M, et al. Japanese population structure, based on SNP genotypes from 7003 individuals compared to other ethnic groups: effects on population-based association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen J, Zheng H, Bei JX, Sun L, Jia WH, Li T, et al. Genetic structure of the Han Chinese population revealed by genome-wide SNP variation. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:775–785. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tishkoff SA, Reed FA, Friedlaender FR, Ehret C, Ranciaro A, Froment A, et al. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009;324:1035–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.1172257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu S, Yin X, Li S, Jin W, Lou H, Yang L, et al. Genomic dissection of population substructure of Han Chinese and its implication in association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:762–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McEvoy BP, Lind JM, Wang ET, Moyzis RK, Visscher PM, van Holst Pellekaan SM, et al. Whole-genome genetic diversity in a sample of Australians with deep Aboriginal ancestry. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barker G. The archaeology of foraging and farming at Niah Cave, Sarawak. Asian Perspect. 2005;44:90–106. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Birdsell JB. The recalibration of a paradigm for the first peopling of Greater Australia. In: Allen J, Golson J, Jones R, editors. Sunda and Sahul: Prehistoric Studies in Southest Asia, Melanesia, and Australia. New York: Academic Press; 1977. pp. 113–167. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bellwood P, Nitihaminoto G, Irwin G, Gunadi, Waluyo A, Tanudirjo D. 35,000 years of prehistory in the northern Moluccas. In: Bartstra GJ, editor. Bird's Head Approaches: Irian Jaya Studies, A Programme for Interdisciplinary Research. Balkema: Rotterdam; 1998. pp. 233–275. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bellwood P. First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cox MP, Karafet TM, Lansing JS, Sudoyo H, Hammer MF. Autosomal and X-linked single nucleotide polymorphisms reveal a steep Asian-Melanesian ancestry cline in eastern Indonesia and a sex bias in admixture rates. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277:1589–1596. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gray RD, Drummond AJ, Greenhill SJ. Language phylogenies reveal expansion pulses and pauses in Pacific settlement. Science. 2009;323:479–483. doi: 10.1126/science.1166858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lewis MP. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 16th ed. Dallas: SIL International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bellwood P, Fox JJ, Tryon D. The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Canberra: ANU E Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wallace AR. The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan, and the Bird of Paradise. London: Macmillan and Co.; 1869. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mona S, Grunz KE, Brauer S, Pakendorf B, Castri L, Sudoyo H, et al. Genetic admixture history of Eastern Indonesia as revealed by Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1865–1877. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Karafet TM, Hallmark B, Cox MP, Sudoyo H, Downey S, Lansing JS, et al. Major east-west division underlies Y chromosome stratification across Indonesia. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:1833–1844. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ellegren H. The different levels of genetic diversity in sex chromosomes and autosomes. Trends Genet. 2009;25:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reich D, Patterson N, Kircher M, Delfin F, Nandineni MR, Pugach I, et al. Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:516–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pugach I, Matveyev R, Wollstein A, Kayser M, Stoneking M. Dating the age of admixture via wavelet transform analysis of genome-wide data. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ross M. Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages. In: Pawley A, Attenborough R, Golson J, Hide R, editors. Papuan Pasts: Cultural, Linguistic and Biological Histories of Papuan-speaking Peoples. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics; 2005. pp. 15–65. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Denham T, Donohue M. Pre-Austronesian dispersal of banana cultivars West from New Guinea: linguistic relics from Eastern Indonesia. Archaeol Ocean. 2009;44:18–28. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hill C, Soares P, Mormina M, Macaulay V, Clarke D, Blumbach PB, et al. A mitochondrial stratigraphy for island southeast Asia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:29–43. doi: 10.1086/510412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Soares P, Trejaut JA, Loo JH, Hill C, Mormina M, Lee CL, et al. Climate change and postglacial human dispersals in southeast Asia. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1209–1218. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Friedlaender JS, Friedlaender FR, Reed FA, Kidd KK, Kidd JR, Chambers GK, et al. The genetic structure of Pacific Islanders. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wollstein A, Lao O, Becker C, Brauer S, Trent RJ, Nürnberg P, et al. Demographic history of Oceania inferred from genome-wide data. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1983–1992. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stoneking M, Krause J. Learning about human population history from ancient and modern genomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nrg3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Narang A, Jha P, Rawat V, Mukhopadhyay A, Dash D, et al. Indian Genome Variation Consortium. Recent admixture in an Indian population of African ancestry. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shah AM, Tamang R, Moorjani P, Rani DS, Govindaraj P, Kulkarni G, et al. Indian Siddis: African descendants with Indian admixture. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]