Abstract

The AVR9 elicitor from the fungal pathogen Cladosporium fulvum induces defense-related responses, including cell death, specifically in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) plants that carry the Cf-9 resistance gene. To study biochemical mechanisms of resistance in detail, suspension cultures of tomato cells that carry the Cf-9 resistance gene were initiated. Treatment of cells with various elicitors, except AVR9, induced an oxidative burst, ion fluxes, and expression of defense-related genes. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Cf9 tomato leaf discs with Avr9-containing constructs resulted efficiently in transgenic callus formation. Although transgenic callus tissue showed normal regeneration capacity, transgenic plants expressing both the Cf-9 and the Avr9 genes were never obtained. Transgenic F1 seedlings that were generated from crosses between tomato plants expressing the Avr9 gene and wild-type Cf9 plants died within a few weeks. However, callus cultures that were initiated on cotyledons from these seedlings could be maintained for at least 3 months and developed similarly to callus cultures that contained only the Cf-9 or the Avr9 gene. It is concluded, therefore, that induction of defense responses in Cf9 tomato cells by the AVR9 elicitor is developmentally regulated and is absent in callus tissue and cell-suspension cultures, which consists of undifferentiated cells. These results are significant for the use of suspension-cultured cells to investigate signal transduction cascades.

Plants that defend themselves against fungal pathogen attack activate several defense responses, including production of phytoalexins, accumulation of antimicrobial proteins, and reinforcement of cell walls (Dixon et al., 1994). Although these responses are frequently associated with localized collapse of infected tissue, termed the HR, evidence for a causal link between the HR and resistance is presently lacking (Dangl et al., 1996). Activation of these defense responses follows fungal pathogen recognition, which involves elicitor perception and subsequent signal transduction. Most elicitor molecules originate from the invading pathogens, but chemical plant stimuli released during infection can also elicit defense responses (Boller, 1995; De Wit, 1995). Pathogen-derived elicitor molecules can be race specific and produced by the pathogen in planta, or the molecules can be nonspecific and enzymatically released from the surface of the pathogen during the infection process (De Wit, 1995). These various types of elicitor molecules induce biochemical changes as part of the resistance response. Electrolyte leakage, oxidative burst, production of phytoalexins and PR proteins, and increased biosynthesis of ethylene have been described in leaf tissue treated with nonspecific elicitors (Hahlbrock et al., 1986; Peever and Higgins, 1989) and with specific elicitors (Yu et al., 1995; Hammond-Kosack et al., 1996; May et al., 1996; Rustérucci et al., 1996; Wubben et al., 1996).

Many biochemical and physiological aspects of the defense response can be studied in suspension-cultured plant cells. Treatment of parsley cell suspensions with an oligopeptide elicitor from Phytophthora sojae leads to changes in membrane ion permeability, generation of active oxygen species, production of phytoalexins, and activation of defense-related genes (Nürnberger et al., 1994). Glucan elicitors from the same pathogen induce ion fluxes and phytoalexin production in suspension-cultured soybean cells (Ebel et al., 1994). Treatment of suspension-cultured tobacco cells with elicitins from P. sojae leads to ion fluxes and oxidative burst, together with changes in protein phosphorylation and production of ethylene and phytoalexins (Yu, 1995; Rustérucci et al., 1996). These responses have also been described for suspension-cultured tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) cells treated with elicitor preparations derived from different microorganisms such as yeast, Pseudomonas syringae, and Cladosporium fulvum (Felix et al., 1991, 1993; Vera-Estrella et al., 1992, 1994; Chandra et al., 1996).

Tomato plants that are challenged with the fungal pathogen C. fulvum are resistant to infection when carrying a resistance gene that matches an avirulence gene of the intruding pathogen (De Wit, 1995). Two avirulence genes, Avr4 and Avr9, have been cloned and the encoded elicitor peptides have been isolated and characterized (Van Kan et al., 1991; Joosten et al., 1994). As soon as the fungus penetrates the leaf, both avirulence genes are expressed to high levels and the encoded elicitor molecules, which are secreted as pre-proteins, are proteolytically processed in the apoplast into Cys-rich, mature elicitor peptides (Van den Ackerveken et al., 1993; Joosten et al., 1997). Recently, the three-dimensional structure of the AVR9 elicitor peptide was elucidated by 1H-NMR (Vervoort et al., 1997). The AVR9 peptide consists of three antiparallel β-strands interconnected by three disulfide bonds. The AVR9 peptide, which is folded as a cystine knot protein, shows structural homology to carboxy peptidase inhibitor (Vervoort et al., 1997).

The mechanisms of AVR9 perception and subsequent intracellular signal transduction events are not well understood. The Cf-9 resistance gene encodes a putative membrane-anchored glycoprotein with a large extracellular loop consisting of 28 imperfect Leu-rich repeats (Jones et al., 1994). Based on the structural features of the CF9 protein, it has been speculated that it functions as a receptor for the AVR9 elicitor peptide. However, a high-affinity binding site for AVR9 was found to be present on the plasma membranes of tomato and other solanaceous plants, irrespective of the presence of the Cf-9 gene (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). Injection of the AVR9 elicitor peptide into the leaves of Cf9 tomato plants induces an oxidative burst; electrolyte leakage; production of ethylene, salicylic acid, and PR proteins; and a hypersensitive cell death at the injected area (Scholtens-Toma and De Wit, 1988; Hammond-Kosack et al., 1996; May et al., 1996; Wubben et al., 1996). Leaves of tomato plants that do not carry the Cf-9 gene do not respond upon injection of AVR9 elicitor. Seedlings obtained from crosses between wild-type Cf9 tomato plants and transgenic Cf0 tomato plants that express the Avr9 gene showed delayed growth, necrosis, and eventually complete plant death (Hammond-Kosack et al., 1994; Honée et al., 1995).

To study the biochemical mechanism of AVR9-induced plant defense in detail we initiated suspension cultures of tomato cells carrying the Cf-9 gene. These suspension-cultured cells responded upon addition of various nonspecific elicitors. However, treatment of cell-suspension cultures with AVR9 elicitor did not induce ion fluxes, oxidative burst, or activation of PR-protein genes. Using transgenic Cf9 tomato cells expressing the Avr9 gene, we show that undifferentiated Cf9 tomato cells, like callus tissue and cell-suspension cultures, are insensitive to AVR9 elicitor protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Elicitor Preparations

The mature AVR9 elicitor peptide of 28 amino acids was isolated from apoplastic fluid, which was obtained from leaves of the tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) genotype MM-Cf5 infected by race 5 of Cladosporium fulvum, according to the protocol described by Van den Ackerveken et al. (1993). The concentration of the AVR9 peptide was determined by low-pH PAGE (Reisfeld et al., 1962) using a well-defined AVR9 batch as a reference. The Pmg elicitor was kindly provided by Dr. D. Scheel (Institute of Plant Biochemistry, Halle, Germany). Xylanase from Trichoderma viride, chitosan, and chitopentaose were kindly provided by Dr. T. Boller (Friedrich Miescher Institute, Basel, Switzerland). Fusicoccin from Fusicoccum amygdali was purchased from Sigma.

Avr9-Containing Constructs for Plant Transformation

A 440-bp CaMV 35S promoter fragment was amplified by PCR using construct pMOG410 (Hood et al., 1993) as the template and the two oligonucleotides 5′-CTTGGATCCCTGCAGGTCAAC-3′ and 5′-CTGGAATTCACGTGTCCTCTCCAAATG-3′ as forward and reverse primers, respectively. The reverse primer in combination with the oligonucleotide 5′-TTGACTGGATCCAAAATCTAAC-3′ as the forward primer and construct pETVgus27–1 as the template (Martini et al., 1993) were used for amplification by PCR of a gst1 promoter fragment. This gst1 promoter fragment consists of 340-bp gst1 promoter sequences from −402 to −130 fused to CaMV 35S promoter sequences from −46 to +8 encompassing the TATA box. The oligonucleotide primers were constructed in such a way that the amplified CaMV 35S and gst1 promoter fragments contained a BamHI site at the 5′ terminus and an EcoRI site at the 3′ terminus to enable cloning in pBluescript and to generate pFM1 and pFM2, respectively. Except for the EcoRI sites, the 3′ end of the cloned promoter fragments also contained a Pml1 site. After restriction of pFM1 and pFM2 with Pml1 and EcoRI, a SnaB1-EcoRI fragment containing the synthetic tobacco mosaic virus-untranslated omega-leader sequence (Gallie et al., 1987) 5′-TACGTATTTTTACAACAATTACCAACAACAACAAACAACAAACAACATTACAATTACTATTTACAATTACCATGGTGAATTC-3′ was inserted downstream of the CaMV 35S and gst1 promoter fragments, generating constructs pFM4 and pFM5, respectively. In constructs pFM4 and pFM5, a NcoI site is present immediately upstream of the EcoRI site.

Two oligonucleotide primers, 5′-CCAGGTACCATCCATGGGATTTGTTC-3′ and 5′-CGATAAAAGAGCTCAATGTACACATTGG-3′, and construct potato virus X:Avr9 (Hammond-Kosack et al., 1995) as the template, were used to amplify by PCR a fragment encoding the PR1a signal sequence fused to the mature AVR9 elicitor peptide of 28 amino acid residues. These primers also generated a PR1a-Avr9(R8K) fragment by PCR amplification using potato virus X:Avr9(R8K) (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997) as the template. Both amplified fragments contain KpnI and NcoI sites at the 5′ terminus and a SacI site at the 3′ terminus. Using the KpnI and SacI sites, the fragments were cloned in pBluescript-derived vectors, which placed the PR1a-Avr9 and PR1a-Avr9(R8K) fragments upstream of the TPI-II terminator sequences (An et al., 1989), thereby generating constructs pFM8 and pFM9, respectively. In pFM8 and pFM9 EcoRI sites are present downstream of the TPI-II fragment. The NcoI-EcoRI fragment of pFM8 containing the PR1a-Avr9 coding sequences fused to the TPI-II terminator sequences was cloned in NcoI and EcoRI linearized pFM4 and pFM5 generating constructs pFM10 and pFM12, respectively. The NcoI-EcoRI fragment of pFM9 containing the PR1a-Avr9(R8K) coding sequences fused to the TPI-II terminator sequences was also cloned in NcoI- and EcoRI-linearized pFM4, generating construct pFM11. Subsequently, the Avr9 expression cassettes of constructs pFM10, pFM11, and pFM12 were as BamHI-EcoRI fragments cloned in the binary vector pMOG800, which differs from pMOG402 (Jongedijk et al., 1995) by an extra KpnI site in the multiple cloning site, revealing pMOG978, pMOG979, and pMOG980.

The full-length Cf-9 coding sequence was amplified by PCR using Cf-9 cDNA as the template (kindly provided by J. Jones, Norwich, UK; Jones et al., 1994) and the forward oligonucleotide primer 5′ TGCTCTAGAGCATGCCATGGATTGTGTAAAACTTG-3′ and the reverse oligonucleotide primer 5′-AGACTGCAGCTAATATCTTTTCTTGTG-3′. These oligonucleotide primers were constructed in such a way that the amplified fragment at the 5′ terminus contained the XbaI and NcoI sites and at the 3′ terminus a PstI site. The XbaI and PstI sites were used for cloning of the Cf-9 fragment in a pBluescript-derived vector, which placed the Cf-9 coding sequence upstream of TPI-II terminator sequences, resulting in construct pCf9.4. Construct pCf9.4 contained a BamHI site downstream of the TPI-II sequences. Subsequently, the NcoI-XbaI fragment of construct pFM4 encompassing gst1:Ω sequences was placed in front of the Cf-9 coding sequence in construct pCf9.4, which revealed construct pCf9.5. The Cf-9 expression cassette of construct pCf9.5 was cloned as a BamHI fragment in BamHI-linearized pMOG979, which resulted in construct pMOG1043.

Tissue Culture

Tomato seeds of lines Sonato and Sonatine, harboring the C. fulvum resistance genes Cf-2 and Cf-4, and Cf-2, C-f4, and Cf-9, respectively, were surface sterilized for 20 min in 2% (w/v) NaOCl and subsequently were allowed to germinate on synthetic Murashige-Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) supplemented with 1% (w/v) agar and 2% (w/v) Suc at 25°C. After 10 d, explants of cotyledons were transferred to synthetic medium containing Murashige-Skoog salts and B5 vitamins (Gamborg et al., 1968) supplemented with 1 mg/L 2,4-D, 0.1 mg/L 6-furfurylaminopurine (kinetin), 3% (w/v) Suc, and 1% (w/v) agar, pH 5.7, and incubated in the dark at 25°C to induce callus formation. Callus tissue was transferred onto fresh medium every 4 weeks. After 4 to 6 months, friable calli were transferred into liquid Murashige-Skoog medium (as above) and incubated under continuous shaking (120 rpm, at 25°C in the dark). Every 7 d, cells growing in the log phase were transferred into fresh medium. Suspension-cultured cells used for all experiments were 5 to 6 d old. Cell viability was determined by the use of fluorescein diacetate according to the method of Widholm (1972).

For transformation of MM genotypes Cf0 and Cf9 constructs pMOG978, pMOG979, and pMOG980 were transferred to Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 (Hood et al., 1993). Plant transformation was performed as described by Van Roekel et al. (1993). Primary transformant MM-Cf0 978-16 was selfed and crossed with wild-type MM-Cf9. Seedlings were grown on synthetic Murashige-Skoog medium containing 20% (w/v) Suc and 1% (w/v) agar, at 25°C and with 16 h of light. One cotyledon from each seedling was cut off and used to induce callus (at 25°C in the dark) on modified R3B medium (Meredith, 1979; Koornneef et al., 1987), which is a Murashige-Skoog medium containing 2 mg/L 1-naphthaleneacetic acid, 1 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine, and 3% (w/v) Suc.

GUS Assay

Histochemical localization of GUS activity in transgenic callus was performed with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide as described by Jefferson (1987). Upon vacuum infiltration of explants with a solution consisting of 100 mm sodium phosphate and 0.5 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide, the enzymatic reaction was allowed to proceed for 16 h at 37°C. Finally, leaf explants were cleared of pigment by incubation in ethanol to make blue color more apparent.

Binding Assays

Microsomal membrane fractions were prepared from 6-d-old Sonato and Sonatine cell-suspension cultures following the protocol for the isolation of microsomal membranes from leaf tissue described by Kooman-Gersmann et al. (1996). Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (1976) with BSA as a standard. Binding assays with 125I-AVR9 were performed according to the protocol described by Kooman-Gersmann et al. (1996).

Ion Flux Measurements

Changes in the concentration of extracellular H+ were determined using a micro-pH electrode (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Changes of the extracellular pH induced by chitopentaose, xylanase, AVR9, or fusicoccin were registered for 4 h in 5-mL suspension aliquots, which were incubated on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm (Felix et al., 1993). Alternatively, changes of the extracellular pH induced by Pmg elicitor, AVR9, or fusicoccin were followed according to the method of Conrath et al. (1991). An assay suspension was prepared that contained 5- to 6-d-grown cells washed with fresh medium and subsequently resuspended to a cell density of 2 to 6 × 105 cells/mL in 1 mm Mes buffer containing 4% of the liquid growth medium and 3% (w/v) Suc, pH 5.7 adjusted with Bis-Tris. The assay suspension was preincubated for 2 h and subsequently elicitor treated. Changes of the extracellular pH AVR9 or fussicoccin were also measured according to the protocol of Vera-Estrella et al. (1994). Cells were resuspended in 0.3 μm Tris/Mes buffer with 3% (w/v) Suc, pH 6.5, to a cell density of 2 to 6 × 105 cells/mL and preincubated on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm for 2 h. Changes of the extracellular H+ concentration were recorded for 4 h after addition of AVR9 or fusicoccin.

Uptake of [45Ca]2+ into tomato cells was monitored according to the method of Conrath et al. (1991). Tomato cells were preincubated for 2 h in an assay suspension as described above. Subsequently, elicitor-induced [45Ca]2+ uptake was measured for 2 h.

Determination of Active Oxygen Species

Generation of H2O2 was monitored in a fluorescence transition assay (Apostol et al., 1989). In an assay suspension, suspension-cultured tomato cells were preincubated for 3 to 4 h under continuous shaking at 120 rpm. Subsequently, a 2-mL aliquot of the assay suspension was transferred to a 3-mL quartz cuvette and 4 μL of 1 mg/mL pyranine (8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid trisodium salt; Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) was added. To prevent sedimentation of cells, the cells were continuously stirred at a slow speed without mechanically disrupting or eliciting them. Subsequently, elicitor was added and the production of H2O2 was followed up to 6 h after elicitation by monitoring the quenching of fluorescence of pyranine (emission 512 nm and excitation 405 nm).

For measurement of O2− generation Cyt c reduction was followed according to the method described by Doke (1985), using 50-μL suspension-cultured cells in a final volume of 1 mL.

Oxygen consumption was monitored on 2.5-mL aliquots of suspension-cultured cells using a Clark O2 electrode (Rank Bros., Bottisham, Cambridge, UK) and recorded continuously for 30 min.

RNA Isolation and RNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Suspension-cultured tomato cells were collected by filtration and subsequently frozen in liquid N2. Total RNA was isolated according to the protocol described by Verwoerd et al. (1989). Thirty micrograms of total RNA was separated on a 1.5% agarose gel containing formaldehyde and subsequently transferred to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham) as described by Maniatis et al. (1982). The blot was hybridized with cDNA probes labeled with α-32P using the Ready.To.Go labeling kit from Pharmacia, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The blot was washed at 65°C in 2× SSC.

RESULTS

Injection of the AVR9 elicitor peptide in leaves of the tomato line Sonatine, which carries the resistance genes Cf-2, Cf-4, and Cf-9, results in a typical HR at the injected area. Leaves of line Sonato, which carries the resistance genes Cf-2 and Cf-4, do not respond upon AVR9 injection, indicating that this HR is highly specific. In leaves of Sonatine plants, necrosis can be induced by AVR9 at a concentration of 1 μg/μL. To study defense-related responses that were specifically induced by the AVR9 elicitor, Sonato and Sonatine cell-suspension cultures were established.

Elicitation of Suspension-Cultured Tomato Cells

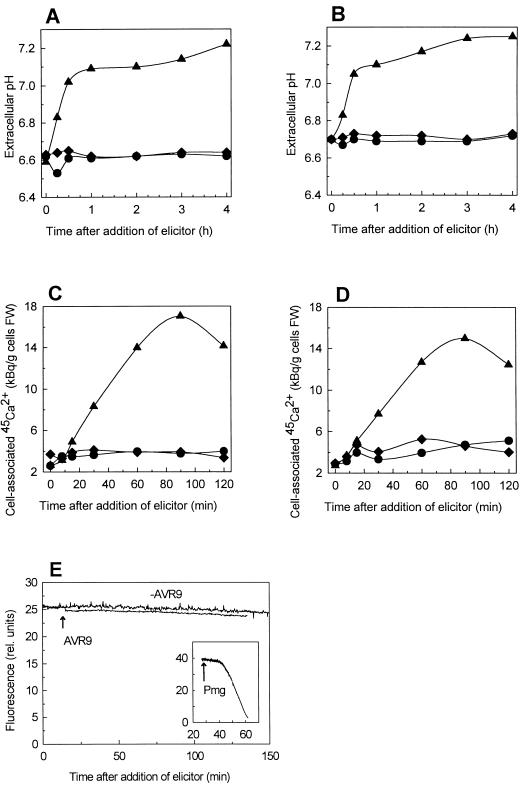

Addition of AVR9 elicitor as high as 10 μg/μL to suspension-cultured Sonatine cells that contain the Cf-9 gene and to Sonato cells without the Cf-9 gene did not induce increase or decrease of the extracellular pH (Fig. 1, A and B). Treatment of suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells with the nonspecific elicitor preparation Pmg (Parker et al., 1991) at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL raised the extracellular pH (Fig. 1, A and B). Suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells responded identically to Pmg-elicitor treatment. The time course of Pmg-elicitor-induced extracellular alkalization was similar, as reported for suspension-cultured parsley cells (Nurnberger et al., 1994). Alkalization of the extracellular medium of Sonato and Sonatine cell cultures was also observed after addition of the nonspecific elicitors chitopentaose, at a final concentration of 10 nm, and xylanase, at a concentration of 10 μg/mL (results not shown). Both elicitors have been reported to induce an increase of the pH in tomato MsK8 cell-suspension medium (Felix et al., 1993). Suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells responded also upon the addition of the phytotoxin fusicoccin. Fusicoccin stimulates H+-ATPase activity, thereby inducing extracellular acidification (Marrè et al., 1993). At a final concentration of 2 μm, fusicoccin induced extracellular acidification in both Sonato and Sonatine cell cultures (results not shown). In addition to H+ fluxes, elicitor-induced changes in the Ca2+ permeability of plasma membranes of the suspension-cultured cells were analyzed. Treatment of suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells with Pmg elicitor resulted in a Ca2+ influx (Fig. 1, C and D), whereas addition of AVR9 elicitor up to 10 μg/mL did not stimulate Ca2+ uptake (Fig. 1, C and D).

Figure 1.

Time courses of elicitor-stimulated H+ and Ca2+ fluxes across the plasma membrane and H2O2 production in suspension-cultured tomato cells. Extracellular alkalization of Sonato (A) and Sonatine (B) cells, Ca2+ influx of Sonato (C) and Sonatine cells (D), and H2O2 production of Sonatine cells (E) are shown. ♦, untreated; •, AVR9 elicitor (10 μg/mL); and ▴, Pmg elicitor (50 μg/mL). FW, Fresh weight.

The oxidative burst, measured by the release of H2O2, was investigated by monitoring decreasing fluorescence of pyranin due to oxidation after challenging suspension-cultured Sonatine and Sonato cells with different elicitor preparations. Addition of the Pmg elicitor to Sonatine cells induced the formation of H2O2 (Fig. 1E). The same response was recorded for Sonato cells treated with Pmg elicitor (results not shown). Treatment of suspension-cultured Sonatine cells with AVR9 elicitor up to 10 μg/mL did not induce H2O2 production (Fig. 1E). Release of H2O2 by Sonato cells was also not induced by addition of AVR9 elicitor (results not shown). Treatment of Sonato and Sonatine cell suspensions with AVR9 did not induce O2 uptake or the generation of the oxygen radicals O2−, which was measured by Cyt c reduction (results not shown). In conclusion, suspension-cultured Sonatine cells did not respond by an oxidative burst upon AVR9 elicitor treatment.

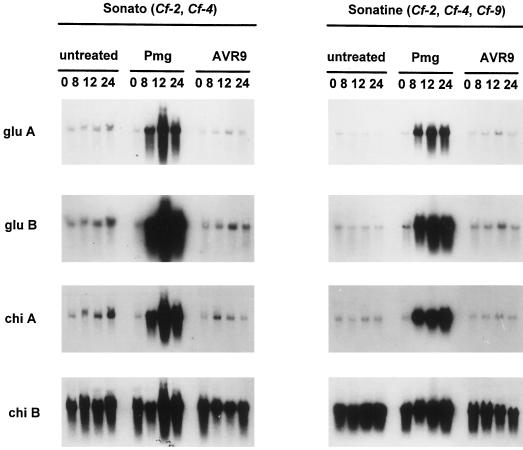

To investigate elicitor-induced transcriptional activation of defense-related genes, total RNA isolated from elicitor-treated suspension cells was hybridized with cDNA clones of tomato PR-protein genes that encode basic and acidic isoforms of chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase. The gene encoding the basic isoform of chitinase was found to be constitutively expressed in suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells (Fig. 2). Expression of genes that encoded the acidic and basic isoforms of β-1,3-glucanase and the acidic isoform of chitinase was increased in Pmg elicitor-treated suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells (Fig. 2). Addition of AVR9 elicitor to suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells did not increase expression of any of these PR-protein genes.

Figure 2.

Elicitor-induced PR-protein gene expression. Northern-blot analysis of total RNA (20 μg) isolated from suspension-cultured Sonato cells (left panel) and Sonatine cells (right panel) at different time points (0, 8, 12, and 24 h) after treatment with AVR9 elicitor (10 μg/mL) and Pmg elicitor (50 μg/mL) or from untreated cells. Hybridization was performed with 32P-labeled cDNA probes from acidic 1,3 β-glucanase (glu A), basic 1,3 β-glucanase (glu B), acidic chitinase (chi A), and basic chitinase (chi B).

Cell Death Induced in Transgenic Cf9 Tomato Cells Expressing the Avr9 Gene

Sonatine cell-suspension cultures, which were established from independently initiated calli, responded upon treatment with various elicitors except AVR9. The inability of suspension-cultured Sonatine cells to respond to AVR9 treatment is therefore not due to a lack of a general biochemical mechanism involved in the induction of defense-related responses. Elicitor binding to a cellular receptor is required for elicitor perception. Binding studies using microsomal membranes isolated from suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells showed Kd and receptor concentration values of 0.08 pm and 0.5 pmol/mg microsomal protein, respectively, which are similar to those reported for microsomal membranes obtained from tomato leaves (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). Conditions in the extracellular medium of suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells, such as pH, ionic strength, and temperature, allow optimal AVR9 binding (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). Thus, the fact that suspension-cultured Sonatine cells do not respond to AVR9 challenge is not due to a defect in the AVR9 binding of these cells.

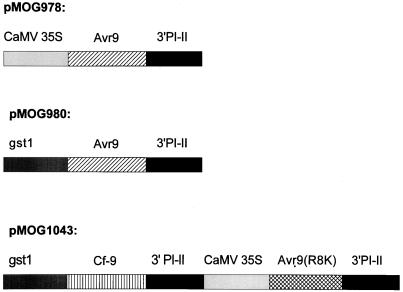

In contrast to Sonatine cell suspensions, leaves of Sonatine plants respond to AVR9 injection, which suggests that induction of defense-related responses by the AVR9 elicitor is developmentally regulated. Three different Avr9-containing constructs, pMOG978, pMOG980, and pMOG1043, were designed for A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of tomato plants (Fig. 3). A synthetic sequence encoding the mature AVR9 peptide of 28 amino acid residues, fused to the PR1a signal sequence to target the AVR9 peptide to the apoplast, was placed behind the tobacco mosaic virus omega-leader. In construct pMOG978, the Ω-PR1a-Avr9 cassette was put under the transcriptional control of the constitutive CaMV 35S promoter and terminator sequences of the proteinase inhibitor II gene (PI-II) from potato (An et al., 1989). In construct pMOG980, the Ω-PR1a-Avr9 cassette of pMOG978 is put under the transcriptional control of the pathogen-inducible gst1 promoter sequences from potato (Martini et al., 1993) and the PI-II terminator sequences. Construct pMOG1043 harbors a 35S:Ω-PR1a-Avr9:TPI-II cassette together with the Cf-9 coding sequence under the transcriptional control of gst1 promoter and PI-II terminator sequences. The Avr9 coding sequence of pMOG1043 contains one nucleotide substitution, which results in Arg (R) changed into a Lys (K) at position 8 of the 28-amino acid AVR9 peptide. The AVR9(R8K) mutant elicitor peptide is more active on Cf9 tomato leaves than the wild-type AVR9 elicitor (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1997).

Figure 3.

Physical map of the Avr9 and the Cf-9 gene expression cassettes of the transformation vectors pMOG978, pMOG980, and pMOG1043. CaMV 35S, CaMV 35S promoter fused to tobacco mosaic virus-untranslated omega-leader sequences; gst1, pathogen-inducible gst1 promoter fragment fused to the TATA box of the 35S CaMV promoter and tobacco mosaic virus-untranslated omega-leader sequences; 3′PI-II, proteinase inhibitor terminator sequences; Avr9, coding sequences of the PR1a signal peptide fused to the mature AVR9 elicitor peptide of 28-amino acid residues; Avr9(R8K), coding sequences of the PR1a signal peptide fused to the mutant, mature AVR9 elicitor peptide of 28-amino acid residues containing an Arg-8-Lys substitution; and Cf-9, sequence encoding the CF9 protein.

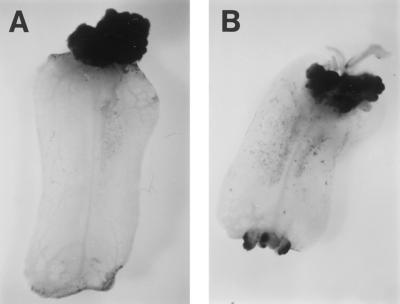

In potato transcriptional activity of the gst1 promoter was shown to be silent in noninfected plant tissue, except for root apices and senescing leaves (Strittmatter et al., 1996). These expression patterns were also found in transgenic tomato plants transformed with a pMOG980-derived construct in which the Avr9 gene was replaced by the uidA locus of Escherichia coli encoding GUS (results not shown). In addition, transgenic callus tissue showed GUS activity, indicating that the gst1 promoter, like the CaMV 35S promoter, is highly active in callus (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Histochemical detection of GUS activity in transgenic MM-CF0 callus that contains the uida locus under the transcriptional control of the CaMV 35S promoter (A) or the gst1 promoter (B).

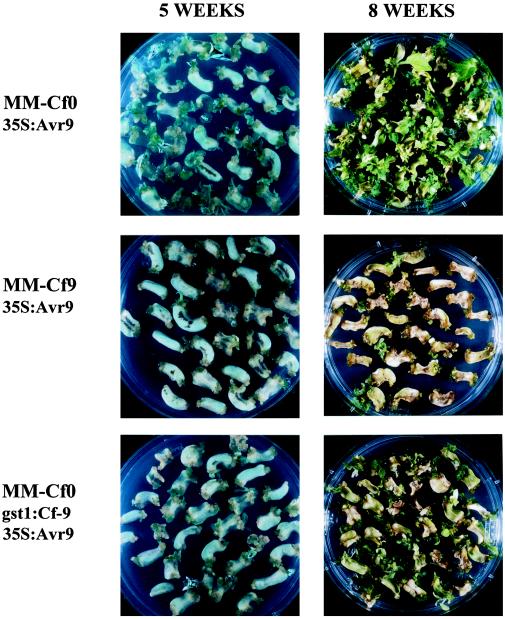

Co-cultivation of leaf discs of tomato MM-Cf0 with A. tumefaciens strains that carry either pMOG978, pMOG980, or pMOG1043 resulted in an average of one callus per leaf disc on selective medium (Table I). Co-cultivation of MM-Cf9 leaf discs with these A. tumefaciens strains resulted in similar callus-formation efficiencies: 1 to 1.4 calli per leaf disc (Table I). Growth of transgenic MM-Cf9 callus tissue that express the Avr9 gene or mutant Avr9(R8K) gene was similar to growth of transgenic MM-Cf0 callus tissue that express Avr9 (Fig. 5). Transgenic MM-Cf0 callus, obtained after transformation with pMOG1043 expressing both the Avr9 and the Cf-9 gene, also showed normal growth (Fig. 5). From MM-Cf0 calli obtained after transformation with constructs pMOG978, pMOG980, and pMOG1043, transgenic plants were obtained after shoot regeneration (Table I). Transgenic plants were also obtained from pMOG980-transformed MM-Cf9 calli after shoot regeneration (Table I). On transgenic MM-Cf9 calli transformed with pMOG978 containing the 35S:Avr9 construct, only a few shoots regenerated but these shoots appeared unable to root on media containing kanamycin, indicating that they had escaped kanamycin selection and thus were not true transformants (Table I). Thus, constitutive expression of the Avr9 gene by the CaMV 35S promoter inhibited regeneration of shoots on transgenic MM-Cf9 callus. When in transgenic MM-Cf9 callus, expression of the Avr9 gene was controlled by the gst1 promoter, which is inactive in shoots, transgenic shoots regenerated and transgenic plants were obtained. These transgenic plants showed a necrotic response upon induction of the gst1 promoter by external stimuli (results not shown). These results suggest that Avr9 gene expression has no effect on growth of undifferentiated Cf9 tissue, whereas upon shoot formation Avr9 gene expression has deleterious effects.

Table I.

Transformation of tomato genotypes MM-Cf0 and MM-Cf9 with Avr9- and Cf-9-containing constructs

| Transformation | Explants | Calli | Calli/Explants | Shoots | Plants | Plants/Explants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. | ||||||

| MM-Cf0 | ||||||

| 35S:Avr9 | 148 | 162 | 1.1 | 104 | 33 | 0.2 |

| MM-Cf0 | ||||||

| gst1:Avr9 | 225 | 218 | 0.9 | 120 | 48 | 0.2 |

| MM-Cf9 | ||||||

| 35S:Avr9 | 117 | 113 | 1.0 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| MM-Cf9 | ||||||

| gst1:Avr9 | 495 | 113 | 1.4 | 298 | 73 | 0.2 |

| MM-Cf0a | ||||||

| gst1:Cf-9-35S: Avr9(R8K) | 96 | 117 | 1.2 | 41 | 6 | 0.1 |

Data obtained from transformation experiments of MM-Cf0 and MM-Cf-9 leaf discs with the constructs pMOG978 (35S:Avr9), pMOG980 (gst1:Avr9), and pMOG1043 (gst1:Cf-9—35S:Avr9[R8K]), respectively. All transformations were performed in parallel except for MM-Cf0 transformed with pMOG1043.

Data obtained from independently performed transformation experiments, parallel transformations of MM-Cf0 and MM-Cf9 with the 35S:Avr9(R8K) construct revealed 1.3 calli/explant and 0.2 plant/explant and 1.5 calli/explant and 0 plant/explant, respectively.

Figure 5.

A. tumefaciens-mediated leaf-disc transformation of cv MM with Avr9- and Cf-9-expressing constructs. Leaf discs of MM-Cf0 on kanamycin-containing medium after co-cultivation with A. tumefaciens strains carrying either construct pMOG978, which contains the 35S:Avr9 expression cassette (top row), or construct pMOG1043, which contains the gst1:Cf-9 and 35S:Avr9(R8K) expression cassettes (bottom row). Leaf discs of MM-Cf9 on kanamycin-containing medium after co-cultivation with an A. tumefaciens strain carrying construct pMOG978, which contains the 35S:Avr9 expression cassette (middle row). Pictures were taken 5 weeks after co-cultivation (left panels), showing callus formation at the edges of the explants, and after 8 weeks, showing shoot regeneration (right panels).

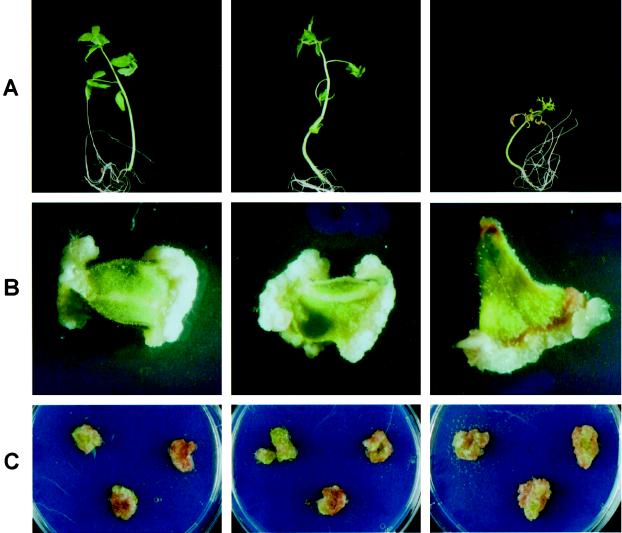

The transgenic plant MM-Cf0 978-16, heterozygous for one intact T-DNA integration of construct pMOG978, was crossed with wild-type MM-Cf9. The appearance of necrosis in F1 seedlings segregated with the presence of the Avr9 transgene and developed as described previously (Honée et al., 1995). In the greenhouse seedlings containing both the Cf-9 and Avr9 genes responded quickly and died within 18 d after sowing (data not shown). Necrosis development was also followed in vitro. On artificial selective medium that contained kanamycin, 29 F1 and 20 MM-Cf0 978-16 seedlings were germinated. On artificial medium without kanamycin, 20 MM-Cf9 seedlings were germinated. After 10 d one cotyledon was cut off from each seedling and transferred to artificial medium containing 2 mg/L 1-naphthaleneacetic acid and 2 mg/L 6-benzylaminopurine to induce callus formation. Within the following 19 d all 29 F1 seedlings, which contain both the Cf-9 and the Avr9 genes, developed a strong necrotic response, resulting in growth inhibition and complete plant death, whereas the MM-Cf9 and MM-Cf0 line 978-16 seedlings developed normally (Fig. 6A). However, callus formation on the explants was similar for all three genotypes. Explants derived from plantlets that expressed both the Avr9 and the Cf-9 genes initiated callus with the same efficiency as explants originating from plantlets that expressed only the Cf-9 or the Avr9 gene. Initially, growth of callus tissue on explants that contained both the Cf-9 and the Avr9 genes appeared retarded compared with callus growth on explants that contained only one of the two genes (Fig. 6B). Probably, stress responses induced in cotyledons that contained both the Avr9 and the Cf-9 genes negatively influenced callus growth. Growth of callus tissue separated from the explants was identical between all three genotypes. Established callus cultures containing Avr9, Cf-9, or both genes developed identically for at least 3 months (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Development of necrosis in F1 seedling from a cross between a transgenic MM-Cf0 978-16 plant expressing Avr9 and a wild-type MM-Cf9 plant. A, In vitro-grown plantlets 4 weeks after seed germination of MM-Cf9 (left), MM-Cf0 978-16 (middle), and F1 progenies of MM-Cf9 crossed with MM-Cf0 line 978-16 (right). B, Callus, 2.5 weeks after initiation on cotyledons from the plantlets shown in A: left, callus on a cv MM-Cf9 explant; middle, callus on a cv MM-Cf0 978-16 explant; and right, callus on an explant of a F1 progeny from MM-Cf9 crossed with MM-Cf0 line 978-16. C, Several independently established callus cultures 3 months after initiation on MM-Cf9 explants (left), MM-Cf0 explants (middle), and on explants of F1 progenies from MM-Cf9 crossed with MM-Cf0 978-16 (right).

DISCUSSION

Undifferentiated tomato cells, like cell-suspension cultures and callus that contain the Cf-9 resistance gene, do not respond upon AVR9 challenge. However, mechanisms that are involved in elicitor-induced defense responses are functional in these undifferentiated tomato cells. An oxidative burst, ion fluxes, and expression of PR-protein genes were induced in suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells upon treatment with various nonspecific elicitors, as has been reported for other plant cell-suspension cultures (Felix et al., 1993; Nurnberger et al., 1994). Addition of the race-specific elicitor AVR9 to suspension-cultured Sonatine cells did not induce oxidative stress, ion fluxes, or gene activation. In contrast, when Cf9 tomato leaves are injected with AVR9 elicitor preparations, an oxidative burst, expression of PR-protein genes, production of ethylene and salicylic acid, and necrotic cell death are induced (De Wit and Spikman, 1982; Hammond-Kosack et al., 1996; May et al., 1996; Wubben et al., 1996). This suggests that induction of defense responses by AVR9, which is restricted to tomato cells carrying the Cf-9 gene, depends on the developmental stage of the cells and is absent in undifferentiated tomato cells.

Regeneration capacity of transgenic Cf9 callus is not negatively influenced by the expression of the Avr9 transgene. Normal shoot regeneration was observed from transgenic Cf9 callus containing Avr9 under the transcriptional control of the gst1 promoter, which is active in callus and inactive in plantlets. In contrast, regeneration was unsuccessful from transgenic callus, which expressed the cytotoxic compound barnase under control of the gst1 promoter (Strittmatter et al., 1995). No transgenic plants were regenerated from transformed Cf9 callus tissue when the CaMV 35S promoter, which is constitutively active in callus tissue and in plantlets, was used to drive the expression of the Avr9 gene. Normally developing Cf9 callus tissue that expressed the Avr9 gene was not only obtained by A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Cf9 leaf discs with Avr9-containing constructs, but could also be generated from cotyledons from seedlings obtained from crosses between Cf-9- and Avr9-expressing parent plants. Established callus cultures were, even after 3 months of culture, indistinguishable from those containing only one of the two genes, Avr9 or Cf-9. However, from these established Cf9 callus cultures that express the Avr9 gene, no shoots could be regenerated. The inability to regenerate shoots was independent of the presence of the Avr9 and Cf-9 genes and is more likely to be characteristic for the species tomato. Callus cultures from tomato genotypes that display a very high regeneration capacity lose the ability to regenerate shoots when they are cultured for more than 1 month (Koornneef et al., 1993). F1 seedlings in which the Cf-9 gene and 35S:Avr9 transgene were combined developed a severe necrotic response and the plants died within 3 weeks after germination. Progress of the necrotic response in these seedlings was similar to that described previously (Hammond-Kosack et al., 1994; Honée et al., 1995). In conclusion, in undifferentiated Cf9 tomato cells, as in callus tissue, expression of the Avr9 gene has no deleterious effects on growth and regeneration capacity, whereas in differentiated Cf9 tissue such as shoots and plantlets, Avr9 gene expression induces cell death. Necrosis was not observed in AVR9-challenged root tissue of Cf9 plants (G. Honée, unpublished data), which also points to developmental regulation of AVR9-induced necrosis in this organ.

The fact that undifferentiated Cf9 tomato cells are specifically nonresponsive to the AVR9 elicitor peptide suggests that a cellular component at the beginning of the AVR9 signaling cascade is absent or inhibited. Two components of the AVR9 signaling cascade are known and at least partially characterized: the AVR9-binding site and the Cf-9 resistance gene (Jones et al., 1994; Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996). Normal AVR9 binding has been observed with microsomal membranes isolated from suspension-cultured tomato cells, which suggests that AVR9 perception is not due to the absence of the AVR9-binding site. Recently, it has been shown that the Cf-9 resistance gene does not encode the high-affinity binding site for AVR9 present in plasma membranes of tomato and other plant species (Kooman-Gersmann et al., 1996; M. Kooman-Gersmann, unpublished data). A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of line MM-Cf0 leaf discs with construct pMOG1043 containing both the Cf-9 and Avr9 genes resulted in normal development of transgenic callus (Table I). The two promoters, CaMV 35S and gst1, that drive Avr9 and Cf-9 expression, respectively, are highly active in callus. However, growth and regeneration capacity of this callus were not inhibited, indicating that expression of the Avr9 and Cf-9 genes had no deleterious cellular effects on these cell types. These observations make it unlikely that absence of functional CF9 protein explains the absence of AVR9-induced defense responses in undifferentiated tomato cells.

Cell-suspension cultures are handled relatively easily, which make them valuable and attractive for standardized experiments to study elicitor-induced defense responses. For different cell-suspension cultures, a variety of elicitor molecules have been shown to induce defense-related responses that are similar to the responses in elicited plants. However, the physiological condition and developmental stage between suspension-cultured cells and cells of intact plants differ. Therefore, conclusions drawn from studies on suspension-cultured cells have to be taken with some caution to explain mechanisms involved in the defense of intact plants. For instance, in suspension-cultured Sonato and Sonatine cells the gene encoding the basic isoform of chitinase is constitutively expressed (Fig. 2). For several defense-related genes differential expression patterns have been reported to be developmentally regulated (Cordero et al., 1994; Logemann et al., 1995). Elicitation of Cf9 tomato cells by AVR9 is also under developmental regulation. In contrast to tomato, suspension-cultured transgenic tobacco cells expressing the Cf-9 gene have been reported to respond specifically upon AVR9 treatment (Jones et al., 1996). Apparently, in undifferentiated transgenic tobacco cells, components involved in the AVR9 signaling cascade are actively present. Studying AVR9-induced defense responses in tomato Cf9 cells at different developmental stages will reveal insight in developmental regulation of these defense responses, which is possibly specific for AVR9-Cf9-mediated resistance in tomato.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Prof. Dr. D. Scheel for the kind gift of partial acid hydrolysate of cell walls of P. sojae; Prof. Dr. T. Boller for his kind gift of xylanase, chitosan, and chitopentaose; and Dr. M. Kooman-Gersmann for technical assistance on AVR9-binding assays. Bert Essenstam and Rick Lubbers are acknowledged for excellent horticulture assistance. Drs. Matthieu Joosten, Sietske Hoekstra, and Ronelle Roth are acknowledged for helpful discussions on the manuscript. Financial support by the Landbouw Export Bureau fund is greatly appreciated.

Abbreviations:

- CaMV

cauliflower mosaic virus

- HR

hypersensitive response

- MM

MoneyMaker

- Pmg

partial acid hydrolysate from the cell walls of Phytophthora megasperma f. sp. glycinea (Phytophthora sojae)

- PR

pathogenesis-related

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants to J.B. from the Life Science Foundation, which is subsidized by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research; and from the Ministry of Economic Affairs; the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science; and the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management, and Fishery in the framework of the Industrial Relevant Research Program of The Netherlands Association of Biotechnology Centers in The Netherlands to G.H.

LITERATURE CITED

- An G, Mitra A, Choi HK, Costa MA, An K, Thornburg RW, Ryan CA. Functional analysis of the 3′ control region of the potato wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor II gene. Plant Cell. 1989;1:115–122. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostol I, Heinstein PF, Low PS. Rapid stimulation of an oxidative burst during elicitation of cultured plant cells. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:109–116. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller T. Chemoperception of microbial signals in plant cells. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Martin GB, Low PS. The Pto kinase mediates a signalling pathway leading to the oxidative burst in tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13393–13397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U, Jeblick W, Kauss K. The protein kinase inhibitor, K-252a, decreases Ca2+ uptake and K+ release, and increases coumarin synthesis in parsley cells. FEBS Lett. 1991;279:141–144. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero MJ, Raventós D, San Segundo B. Differential expression and induction of chitinases and β-1,3-glucanases in response to fungal infection during germination in maize seeds. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1994;7:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dangl JL, Dietrich RA, Richberg MH. Death don't have no mercy: cell death programs in plant-microbe interactions. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1793–1807. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit PJGM. Fungal avirulence genes and plant resistance genes: unraveling the molecular basis of gene-for-gene interactions. In: Andrews JH, Tommerup IC, editors. Advances in Botanical Research, Vol 21. London: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 147–185. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit PJGM, Spikeman G. Evidence for the occurrence of race- and cultivar-specific elicitors of necrosis in intercellular fluids of compatible interactions of Cladosporium fulvum and tomato. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1982;21:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Harrison MJ, Lamb CJ. Early events in the activation of plant responses. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1994;32:479–501. [Google Scholar]

- Doke N. NADPH-dependent O2− generation in membrane fractions isolated from wounded potato tubers inoculated with Phytophthora infestans. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1985;27:311–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ebel J, Bhagwat A, Cosio EG, Feger M, Kissel U, Mithöfer A, Waldmuller T. Elicitor-binding proteins and signal transduction in the activation of a phytoalexin defense response. Can J Bot. 1994;37:S506–S510. [Google Scholar]

- Felix G, Grosskopf DG, Regenass M, Basse CW, Boller T. Elicitor-induced ethylene biosynthesis in tomato cells: characterization and use as a bioassay for elicitor action. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:19–25. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix G, Regenass M, Boller T. Specific perception of subnanomolar concentrations of chitin fragments by tomato cells: induction of extracellular alkalinization, changes in protein phosphorylation, and establishment of a refractory state. Plant J. 1993;4:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Gallie DR, Sleat DE, Watts JW, Turner PC, Wilson TMA. The 5′-leader sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA enhances the expression of foreign gene transcripts in vitro and in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3257–3272. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.8.3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamborg OL, Miller RA, Ojima K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp Cell Res. 1968;50:151–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(68)90403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahlbrock K, Cuypers B, Douglas C, Fritzemeier KH, Hoffmann H, Rohwer F, Scheel D, Schulz W. Biochemical interactions of plants with potentially pathogenic fungi. In: Lugtenberg B, editor. Recognition in Microbe-Plant Symbiotic and Pathogenic Interactions, Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 311–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond Kosack KE, Harrison K, Jones JDG. Developmentally regulated cell death on expression of the fungal avirulence gene Avr9 in tomato seedlings carrying the disease-resistance gene Cf-9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10445–10449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond Kosack KE, Silverman P, Raskin I, Jones JDG. Race-specific elicitors of Cladosporium fulvum induce changes in cell morphology and the synthesis of ethylene and salicylic acid in tomato plants carrying the corresponding Cf disease resistance gene. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:1381–1394. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond Kosack KE, Staskawicz BJ, Jones JDG, Baulcombe DC. Functional expression of a fungal avirulence gene from a modified potato virus X genome. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1995;8:181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Honée G, Melchers LS, Vleeshouwers VGAA, Van Roeckel JSC, De Wit PJGM. Production of the AVR9 elicitor from the fungal pathogen Cladosporium fulvum in transgenic tobacco and tomato plants. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;29:909–920. doi: 10.1007/BF00014965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood EE, Gelvin SB, Melchers LS, Hoekema A. New Agrobacterium helper plasmids for gene transfer to plants. Transgenic Res. 1993;2:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA. Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1987;5:387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DA, Thomas CM, Hammond Kosack KE, Balint Kurti PJ, Jones JDG. Isolation of the tomato Cf-9 gene for resistance to Cladosporium fulvum by transposon tagging. Science. 1994;266:789–793. doi: 10.1126/science.7973631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DA, Brading P, Dixon M, Hammond Kosack K, Harrison K, Hatzixanthis K, Parniske M, Piedras P, Torres M, Tang S, and others (1996) Molecular, genetic and physiological analysis of Cladosporium resistance gene function in tomato. In G Stacey, B Mullin, PM Gresshoff, eds, Biology of Plant-Microbe Interactions. International Symposium on Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions, St. Paul, MN, pp 57–64

- Jongectyk E, Tigelaar H, Van Roekel JSC, Bres-Vloermans SA, Van Den Elzen PJM, Cornelisson BJC, Melchers LS. Synergistic activity of chintinases and β-1,3-glucanases enhances fungal resistance in transgenic tomato plants. Euphytica. 1995;85:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Joosten MHAJ, Cozijnsen TJ, De Wit PJGM. Host resistance to a fungal tomato pathogen lost by a single base-pair change in an avirulence gene. Nature. 1994;367:384–386. doi: 10.1038/367384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosten MHAJ, Vogelsang R, Cozijnsen TJ, Verberne MC, De Wit PJGM. The biotrophic fungus Cladosporium fulvum circumvents Cf-4-mediated resistance by producing instable AVR4 elicitors. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1–13. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooman-Gersmann M, Honée G, Bonnema G, De Wit PJGM. A high-affinity binding site for the AVR9 peptide elicitor of Cladosporium fulvum is present on plasma membranes of tomato and other solanaceous plants. Plant Cell. 1996;8:929–938. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.5.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooman-Gersmann M, Vogelsang R, Hoogendijk ECM, De Wit PJGM. Assignment of amino acid residues of the AVR9 peptide of Cladosporium fulvum that determine elicitor activity on tomato genotypes carrying the Cf-9 resistance gene. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1997;10:821–829. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Bade J, Hahnhart C, Horsman K, Schel J, Soppe W, Verkerk R, Zabel P. Characterization and mapping of a gene controlling shoot regeneration in tomato. Plant J. 1993;3:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Hahnhart C, Martinelli L. A genetic analysis of cell culture traits in tomato. Theor Appl Genet. 1987;74:633–641. doi: 10.1007/BF00288863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logeman E, Parniske M, Hahlbrock K. Modes of expression and common structural features of the complete phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene family in parsley. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5905–5909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch E, Sambrook J, eds (1982) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- Marrè E, Bellando M, Marrè MT, Romani G, Vergani P. Synergisms, additive and non-additive factors regulating proton extrusion and intracellular pH. Curr Topics Plant Biochem Physiol. 1993;11:213–230. [Google Scholar]

- Martini N, Egen M, Rüntz I, Strittmatter G. Promoter sequences of potato pathogenesis-related gene mediate transcriptional activation selectively upon fungal infection. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:179–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00277110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May MJ, Hammond Kosack KE, Jones JDG. Involvement of reactive oxygen species, glutathione metabolism, and lipid peroxidation in the Cf-gene-dependent defense response of tomato cotyledons induced by race-specific elicitors of Cladosporium fulvum. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:1367–1379. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith CP. Shoot development in established callus cultures of the cultivated tomato Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. Z Pflanzenphysiol. 1979;95:405–411. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger T, Nennstiel D, Jabs T, Sacks WR, Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. High affinity binding of a fungal oligopeptide elicitor to parsley plasma membranes triggers multiple defense responses. Cell. 1994;78:449–460. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JE, Schulte W, Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. An extracellular glycoprotein from Phytophthora megasperma f. sp. glycinea elicits phytoalexin synthesis in cultured parsley cells and protoplasts. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1991;4:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Peever TL, Higgins VJ. Electrolyte leakage, lipoxygenase, and lipid peroxidation induced in tomato leaf tissue by specific and nonspecific elicitors from Cladosporium fulvum. Plant Physiol. 1989;90:867–875. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.3.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisfeld RA, Lewis UJ, Williams DJ. Disk electrophoresis of basic proteins and peptides on polyacrylamide gels by formaldehyde fixation. Anal Biochem. 1962;107:21–24. doi: 10.1038/195281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustérucci C, Stallaert V, Milat ML, Pugin A, Ricci P, Blein JP. Relationship between active oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, necrosis, and phytoalexin production induced by elicitins in Nicotiana. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:885–891. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.3.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtens-Toma IMJ, De Wit GJM, De Wit PJGM. Characterization of elicitor activities of apoplastic fluids isolated from tomato lines infected with new races of Cladosporium fulvum. Neth J Plant Pathol. 1989;95:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter G, Gheysen G, Gianinazzi-Pearson V, Hahn K, Niebel A, Rohde W, Tacke E. Infections with various types of organisms stimulate transcription from a short promoter fragment of the potato gst1 gene. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1996;9:68–73. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-9-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter G, Janssens J, Opsomer C, Botterman J. Inhibition of fungal disease development in plants by engineering controlled cell death. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:1085–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Ackerveken GFJM, Vossen JPMJ, De Wit PJGM. The AVR9 race-specific elicitor of Cladosporium fulvum is processed by endogenous and plant proteases. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:91–96. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kan JAL, Van Den Ackerveken GFJM, De Wit PJGM. Cloning and characterization of complementary DNA of avirulence gene avr9 of the fungal pathogen Cladosporium fulvum, causal agent of tomato leaf mold. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1991;4:52–59. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-4-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Roekel JSC, Damm B, Melchers LS, Hoekema A. Factors influencing transformation frequency of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) Plant Cell Rep. 1993;12:644–647. doi: 10.1007/BF00232816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera Estrella R, Barkla BJ, Higgins VJ, Blumwald E. Plant defense response to fungal pathogens. Activation of host-plasma membrane H+-ATPase by elicitor-induced enzyme dephosphorylation. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:209–215. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera Estrella R, Blumwald E, Higgins VJ. Effect of specific elicitors of Cladosporium fulvum on tomato suspension cells. Evidence for the involvement of active oxygen species. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:1208–1215. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.3.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort J, Van den Hooven HW, Berg A, Vossen P, Vogelsang R, Joosten MHAJ, De Wit PJGM. The race-specific elicitor AVR9 of the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum: a cystine knot protein. Sequence-specific 1H-NMR assignments, secondary structure and global fold of the protein. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verwoerd TC, Dekker BMM, Hoekema A. A small-scale procedure for the rapid isolation of plant RNA's. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2362. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.6.2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widholm JM. The use of fluorescein diacetate and phosafranine for determining viability of cultured plant cells. Stain Technol. 1972;47:189–194. doi: 10.3109/10520297209116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wubben JP, Lawrence CB, De Wit PJGM. Differential induction of chitinase and 1,3-beta-glucanase gene expression in tomato by Cladosporium fulvum and its race-specific elicitors. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1996;48:105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Yu LM. Elicitins from Phytophthora and basic resistance in tobacco. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4088–4094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]