Background: CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis is an innate mechanism to eliminate CEACAM-binding pathogenic bacteria.

Results: Biochemical analyses and FRET-FLIM imaging reveal the direct binding of the adaptor protein Grb14 to the tyrosine-phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3, and this interaction limits phagocytosis.

Conclusion: Grb14 is a negative regulator of CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis.

Significance: Deciphering CEACAM3 interaction partners illuminates the minimal set of cellular factors controlling phagocytosis.

Keywords: Adaptor Proteins, Bacterial Pathogenesis, Cell Signaling, Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), Microarray, Microbial Pathogenesis, Microscopic Imaging, Phagocytosis, Phosphotyrosine, SH2 Domains

Abstract

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 3 (CEACAM3) is a phagocytic receptor on human granulocytes, which mediates the opsonin-independent recognition and internalization of a restricted set of Gram-negative bacteria such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In an unbiased screen using a SH2 domain microarray we identified the SH2 domain of growth factor receptor-bound protein 14 (Grb14) as a novel binding partner of CEACAM3. Biochemical assays and microscopic studies demonstrated that the Grb14 SH2 domain promoted the rapid recruitment of this adaptor protein to the immunoreceptor-based activation motif (ITAM)-like sequence within the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3. Furthermore, FRET-FLIM analyses confirmed the direct association of Grb14 and CEACAM3 in intact cells at the sites of bacteria-host cell contact. Knockdown of endogenous Grb14 by RNA interference as well as Grb14 overexpression indicate an inhibitory role for this adapter protein in CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis. Therefore, Grb14 is the first negative regulator of CEACAM3-initiated bacterial phagocytosis and might help to focus granulocyte responses to the subcellular sites of pathogen-host cell contact.

Introduction

CEACAM3 is a member of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)4-related cell adhesion molecules (CEACAMs) and is exclusively expressed on human granulocytes. Interestingly, no CEACAM3 orthologues have been identified outside of the primate lineage suggesting a recent evolution of this gene (1). The sole reported function of this receptor is the efficient, opsonin-independent recognition and internalization of CEACAM-binding bacteria such as OpaCEA protein-expressing Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Ngo OpaCEA) (2–4). CEACAM3 consists of an extracellular immunoglobulin-variable (IgV)-like domain followed by a hydrophobic transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic sequence (1). Upon binding of bacteria to the IgV-like domain, CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis is initiated by Src family protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) (5, 6). Indeed, the Src family PTKs Hck and Fgr, which are expressed in granulocytes, are rapidly activated and phosphorylate two tyrosine residues within the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3 (3–5). These tyrosine residues are embedded in an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-like sequence (1). In general, phosphorylated tyrosine residues play an important role during intracellular signal transduction. Phosphotyrosine (pTyr) residues serve as docking sites for other proteins containing specific pTyr recognition domains, e.g. the phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) and/or Src homology 2 (SH2) domains (7, 8). Binding of SH2 domains to pTyr residues enables the formation of protein signaling complexes. This is also true in the case of CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis, where bacterial internalization and killing are based on SH2 domain-mediated protein-protein interactions. For example, the phosphorylated tyrosine residue 230 (pTyr-230) within the ITAM-like sequence of CEACAM3 serves as docking site for the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav (9). The direct binding of the Vav SH2 domain to pTyr-230 of CEACAM3 in turn is responsible for strong activation of the small GTPase Rac, which has been observed in CEACAM3-transfected cell lines and primary human granulocytes upon infection with OpaCEA-protein expressing gonococci (3, 5, 9). At the same time, the phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3 allows recruitment of Nck adaptor proteins, which connect CEACAM3 via Nap1 with the f-actin nucleation promoting WAVE complex (10). Together, GTP-bound Rac and its downstream effector WAVE initiate the formation of actin-based lamellipodia resulting in a rapid internalization of CEACAM3-bound Neisseria (9, 11). Furthermore, the regulatory domain of class I phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) can associate with pTyr-230 of CEACAM3 (12). Indeed, PI3K activity is instrumental for the induction of an oxidative burst response by primary human granulocytes upon encounter of CEACAM-binding bacteria (12). In all these cases, the interaction is mediated by phosphorylated tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3 and SH2 domains found in the binding partners of CEACAM3 (10, 12).

The human genome encodes for more than 100 proteins with one or two SH2 domains (13) and there might be additional CEACAM3-interacting proteins within this set. To identify SH2-domain-mediated associations with a given tyrosine-phosphorylated protein, SH2 domain microarrays offer the possibility to conduct a broad interaction screen (14). Such arrays have been successfully used with synthetic phosphopeptides to detect potential interacting partners of the EGF receptor family of receptor tyrosine kinases and phosphorylated bacterial effector proteins, which are translocated into the infected host cell (15, 16). However, an unbiased screen to uncover potential SH2 domain-containing binding partners has not been applied to phosphorylated CEACAM3.

In this study we demonstrate the successful use of SH2 domain microarrays to identify novel binding partners of CEACAM3 by using the intact phosphorylated receptor. Besides the verification of several known interacting proteins, the microarray format revealed the potential binding of the Grb14 SH2 domain to CEACAM3. Grb14 is expressed in human granulocytes and biochemical analyses confirmed that the SH2 domain of Grb14 directly binds to phosphorylated tyrosine residue 230 of CEACAM3. Also in intact cells, recruitment of Grb14 and direct association with the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3 upon bacterial infection could be observed by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM). As shRNA-mediated knock-down of Grb14 increased, whereas overexpression of Grb14 diminished uptake of bacteria, our results suggest a negative regulatory role of Grb14 in CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Recombinant DNA Constructs

Mammalian expression vectors encoding the HA-GFP-, HA-Cerulean-, and HA-mKate-tagged versions of CEACAM3 were described previously (10, 12, 17). cDNA clones for different human SH2 domain containing proteins were obtained from ImaGenes (Berlin, Germany) and were cloned as described (10, 12). The SH2 domains of Grb7 (clone IRAUp969A1146D), Grb10 (clone IRAUp969H0581D) and Grb14 (clone IRATp970B0580D) were amplified from full-length cDNA by PCR with pimers Grb7-SH2-IF-sense 5′-GAAGTTATCAGTCGACAGTGCAGCCATCCACC-3′ and Grb7-SH2-IF-anti 5′-ATGGTCTAGAAAGCTTAGAGGGCCACCCGCGT-3′, Grb10-SH2-IF-sense 5′-GAAGTTATCAGTCGACTCTACCCTAAGTACAGTGATTCAC-3′ and Grb10-SH2-IF-anti 5′-ATGGTCTAGAAAGCTTATAAGGCCACTCGGATGC-3′, and Grb14-SH2-IF-sense 5′-GAAGTTATCAGTCGACGCCACAAACATGGCTATCCAC-3′ and Grb14-SH2-IF-anti 5′-ATGGTCTAGAAAGCTTACTAGAGAGCAATCCTAGCAC-3′, respectively. The resulting PCR fragments were cloned into pDNR-Dual using the In-Fusion PCR Cloning Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). From pDNR-Dual the inserts were transferred by Cre-mediated recombination into pGEX-LoxP. The SH2 domains of Grb7, Grb10, Grb14 and all other SH2 domains were expressed as GST-fusion proteins in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified as described previously (6). The SH2 domain of Grb14 was also transferred from pDNR-Dual into pEGFP-C1-LoxP by Cre/Lox recombination. Full-length Grb14 was amplified with primers Grb14-IF-sense 5′-GAAGTTATCAGTCGACATGACCACTTCCCTGCAAGATGGGCAGAGC-3′ and Grb14-SH2-IF-anti and the resulting PCR fragment was cloned into pDNR-CMV using the In-Fusion PCR Cloning Kit. Grb14ΔSH2 was generated by amplifying pDNR-CMV Grb14 with primers Grb14ΔSH2-sense 5′-CTAGTAAGCTTTCTAGACCATTCGTTTGGC-3′ and Grb14ΔSH2-anti 5′-GTCTAGAAAGCTTAGGACCGGTGGATAGCC-3′. The resulting PCR product was ligated to produce pDNR-CMV Grb14ΔSH2. Full-length Grb14 and Grb14ΔSH2 were transferred from pDNR-CMV into pmKate2-C1-LoxP by Cre/Lox recombination. pmKate2-C1 LoxP was designed by subcloning mKate2 cDNA from pmKate2-C1 (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) via AgeI/XhoI restriction sites into pEGFP-C1 LoxP (9). The cDNA of mCherry (kindly provided by Oliver Griesbeck, Max-Planck Institute of Neurobiology, Martinsried, Germany) was amplified with PCR primers 5′-ATCACCGGTACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG-3′ and 5′-ATCCTCGAGACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC-3′ and inserted into pEGFP-C1 LoxP using AgeI/XhoI restriction sites to obtain pmCherry-C1 LoxP. The SH2 domains of Grb14 and Slp76 were transferred from pDNR-dual into pmCherry-C1 LoxP by Cre/Lox recombination.

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription PCR

RNA from freshly isolated human granulocytes was prepared by peqGOLD TriFast (PEQLAB, Erlangen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription of mRNA was performed by M-MuLV reverse transcriptase and Oligo-dT(18) primer. PCR for Grb7, Grb10, and Grb14 was performed with primers for the corresponding SH2 domains. Primers for β-actin were used as a positive control: β-actin-sense 5′-AGCGGGAAATCGTGCGTG-3′ and β-actin-anti 5′-GGGTACATGGTGGTGCCG-3′.

Generation of Stable Knock-down Cell Lines

Stable knock-down of Grb14 in CEACAM3 expressing HeLa cells was performed as described using the pLKO.1 lentiviral vector (10). shRNA oligonucleotides directed against Grb14 (Grb14-shRNA-sense 5′-CCGGGTGACTTATTAAACTATTGAAGGCTCGAGCCTTCAATAGTTTAATAAGTCACTTTTTTTG-3′ and Grb14-shRNA-anti 5′-AATTCAAAAAAAGTGACTTATTAAACTATTGAAGGCTCGAGCCTTCAATAGTTTAATAAGTCAC-3′) were annealed and ligated into AgeI/EcoRI restricted pLKO.1. The resulting pLKO.1-Grb14-shRNA plasmid or the empty pLKO.1 was co-transfected with pMD2.G and psPAX2 into 293 cells. 72 h after transfection, the virus-containing media were removed and used for transduction of HeLa CEACAM3 cells. Transduced cells were selected for at least 48 h in 1 μg/ml puromycin before further use.

Cell Culture, Transfection of Cells, Cell Lysis, and Western Blotting

The human embryonic kidney cell line 293T (293 cells) was grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% calf serum (CS). HeLa cells stably expressing CEACAM3 were provided by W. Zimmermann (Tumor Immunology Laboratory, LMU München, Germany) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Both cell lines were subcultured every 2–3 days. Transfection of 293 cells with expression vectors was accomplished by standard calcium phosphate co-precipitation using a total amount of 6 μg of plasmid/10 cm culture dish. Cells were used 2 days after transfection. Primary human granulocytes were isolated as described (3). Cell lysis and Western blotting were performed as described previously (18).

Bacteria

Non-piliated N. gonorrhoeae MS11-B2.1 strain N309 expressing a CEACAM-binding Opa protein (Opa52 binding to CEACAM1, CEACAM3, CEA, and CEACAM6, referred to as OpaCEA) was described previously (3, 19). Bacteria were grown on GC agar (Invitrogen) supplemented with vitamins at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in humid atmosphere and selected based on antibiotic resistance and microscopic evaluation of colony opacity. For infection, overnight grown bacteria were taken from GC agar plates, suspended in PBS, and colony forming units (cfu) were estimated by A550 readings according to a standard curve. For labeling, bacteria (2 × 108/ml) were washed with sterile PBS and suspended in 0.5 μg/ml 5-(6)-carboxyfluorescein-succinimidylester (fluorescein), or 4 μg/ml PacificBlue-NHS (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, Karlsruhe, Germany) in PBS. Suspensions were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min in the dark under constant shaking. Afterward, bacteria were washed three times with PBS.

Antibodies and Reagents

Monoclonal antibody (mAb) against the GST-tag (clone B-14) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), mAb against phosphotyrosine (clone PY72) was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY), mAb against GFP (clone JL-8) and pAb against mCherry were from Clontech (Mountain View, CA), mAb against CEACAMs were purchased from Genovac (clone D14HD11; Freiburg, Germany) or ImmunoTools (clone IH4Fc; Friesoythe, Germany). Polyclonal antibody (pAb) against human Grb14 was purchased from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA). The mAb against HA-tag and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against N. gonorrhoeae (IG-511) were generated as described (9). Rabbit polyclonal antiserum against mKate was produced in the local animal facility at the University of Konstanz. All peroxidase- and fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA).

Manufacturing and Probing of SH2 Domain Arrays

Purified SH2 domains were spotted in quadruplicate at 1.3 ng/spot onto aldehyde-modified glass slides (Nexterion Slides AL, PEQLAB, Erlangen, Germany) using a piezoelectric non-contact microarrayer (NanoPlotter 2.1, GeSim, Dresden, Germany). Each array consisted of 16 × 16 spots with a spot to spot distance of 0.714 mm. After 1-h incubation at 70% humidity, the slide was attached to a 16 well incubation chamber (16 Pad FAST Slide incubation chamber, Whatman). Afterward, free aldehyde groups of the surface were inactivated by incubation with 0.25% NaBH4 in PBS for 20 min followed by three washing-steps with PBS-T (PBS containing 0.01% Tween-20). Arrays were incubated with cell lysates or PBS-T over night at 4 °C. Following incubation, the arrays were washed three times with PBS-T and probed with specific primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature followed by Cy3-labeled secondary antibody. Finally, the slide was washed three times with PBS-T, rinsed with PBS, and dried by centrifugation.

Scanning and Analysis of Protein Arrays

SH2 domain arrays were scanned at 532 nm wavelength using the microarray scanner LS-Reloaded (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Fluorescence intensities of the spots were determined using the image analysis software Array-Pro Analyzer 4.5 (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). Binding signals of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated CEACAM3 were normalized to the amount of array-bound SH2 domains as measured by probing arrays with anti-GST antibody.

GST Pull-down Assay, Far Western Probing of Peptide Spot Membranes, and Co-immunoprecipitation

For GST pull-down assays, 5 μg of purified GST or GST-fusion proteins attached to glutathione-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) were added to 750 μl of cleared lysates from 293 cells transfected with CEACAM-encoding constructs or the empty vector (6 μg). Where indicated, the cells were additionally co-transfected with a v-Src-encoding plasmid (0.5 μg) to ensure maximum tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM3. Samples were incubated over night at 4 °C under constant rotation. After four washes with PBS-T, precipitates were boiled in 2× SDS sample buffer before SDS gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis. Generation and probing of peptide spot membranes was conducted as described previously using 20 μg of GST-Grb14-SH2 or GST alone (6, 12). For co-immunoprecipitations, 293 cells were transfected with the indicated combination of constructs and lysed after 48 h. For precipitation, lysates were incubated with 3 μg of polyclonal rabbit anti-mKate antibody for 3 h followed by 1-h incubation with protein A/G-Sepharose, all at 4 °C. After three washes with Triton buffer, precipitates were boiled in SDS sample buffer before SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Immunofluorescence Staining and Confocal Microscopy

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described (6) using a TCS SP5 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) (17).

FRET Measurements

For acceptor bleaching experiments the implemented FRET acceptor bleaching wizard of the Leica TCS SP5 was used. Prebleach and postbleach images were serially recorded with excitation of EGFP at 488 nm and mCherry at 561 nm and appropriate emission bands. Low laser intensities were used to avoid acquisition bleaching. The acceptor mCherry was bleached with high laser intensity at 561 nm. Images were processed with ImageJ as described previously (17). Apparent FRET efficiency was calculated by Eapp = 1 − (DDpre/DDpost) with DDpre, the donor prebleach intensity and DDpost, the donor postbleach intensity at 488 nm excitation, respectively. Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) measurements to determine fluorescence lifetime were performed using a FLIM upgrade kit (Picoquant, Berlin, Germany) for standard confocal scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP5). EGFP was excited with a tunable Ti:Sapphire laser (Mira, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) by two-photon excitation at 950 nm. FLIM data were processed using pixel-based fitting software (SymPhoTime, Picoquant) to determine EGFP lifetimes in presence (τDA) and absence (τD) of the acceptor mCherry. Goodness of fit was assessed by the calculated standard least squares (χ2). FRET efficiency (E) was determined by E = 1 − (τDA/τD).

Quantification of Bacterial Invasion

Bacterial invasion was determined by flow cytometry as described previously (20). Briefly, 1 day before infection 1 × 106 cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates. Cells were infected at MOI of 20 fluorescein-labeled bacteria/cell. After 1 h of infection, the infected cells were suspended by 1 min trypsin treatment. After two times washing with ice-cold flow buffer (PBS containing 1% heat inactivated FCS) the cells were resuspended in 1 ml of flow buffer. To quench signals from extracellular bacteria, trypan blue was added to a final concentration of 0.2% directly before flow cytometric analysis (LSR II; BD Biosciences). To determine the rate of internalization, Cerulean-positive cells were gated and analyzed for fluorescein-fluorescence. The mean fluorescein-fluorescence is used as an estimate for internalized bacteria and thus multiplied by the percentage of fluorescein-positive cells to yield the uptake index (20). To account for inter-experimental deviations in absolute fluorescence intensity, values were normalized to the CEACAM3-only samples, the mean value of which was set as 100%. Alternatively, uptake of bacteria was quantified by differential staining of intra- and extracellular bacteria as described previously (21). Briefly, transfected 293 cells were seeded on coated coverslips and infected the following day with PacificBlue-labeled gonococci at an MOI of 30 for 1 h. Samples were washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After washing, samples were blocked with 10% heat inactivated CS in PBS and stained for extracellular bacteria with a polyclonal anti-Neisseria antibody (IG-511) followed by an appropriate Cy5-labeled secondary antibody. After three washes with PBS, samples were embedded in mounting medium (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark).

RESULTS

SH2 Domain Array Identified the Grb14 SH2 Domain as an Interaction Partner of Phosphorylated CEACAM3

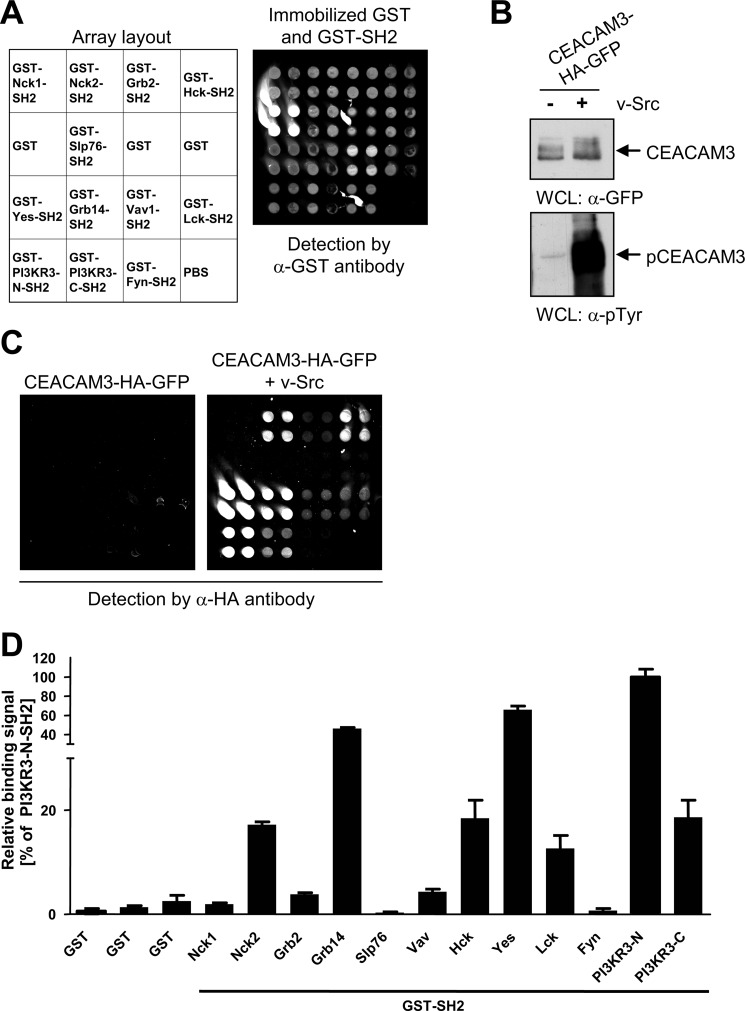

The human genome encodes more than 100 different SH2 domains. To identify further SH2 domain signaling proteins interacting with the phosphorylated ITAM-like sequence of CEACAM3, we performed a screen using a custom-made SH2 domain protein array. For this purpose, recombinant GST-fused SH2 domains of different proteins or GST alone were immobilized on aldehyde-modified glass slides in quadruplicates (for a layout of the array see Fig. 1A). The SH2 domains of Nck2, Vav, PI3K, as well as Src-kinases Hck, Yes, and Lck were employed as they are known binding partners of CEACAM3 (6, 9, 10, 12). Furthermore, the SH2 domains of Fyn, Slp76, and Grb2 were arrayed as negative controls, as they have been shown previously not to bind to phosphorylated CEACAM3 (6, 10). Successful immobilization of GST alone and GST-SH2 domains was verified by incubating one array with anti-GST antibody, followed by Cy3-labeled secondary antibody and readout at 532 nm (Fig. 1A). To prepare the cell lysates for probing the arrays, 293 cells were co-transfected with or without a v-Src-encoding plasmid together with a CEACAM3-HA-GFP encoding vector. The expression of the constitutive active PTK v-Src ensured phosphorylation of CEACAM3 at tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic ITAM-like sequence (4, 6). Western blotting confirmed equal expression of the receptor in the whole cell lysates (Fig. 1B, upper panel) and, as expected, v-Src promoted strong tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM3 (Fig. 1B, lower panel). Next, arrays were incubated with cell lysate containing either phosphorylated or unphosphorylated CEACAM3 (Fig. 1C). After washing, CEACAM3 bound to immobilized SH2 domains on the array was detected with anti-HA antibody. In agreement with previous biochemical and functional studies, phosphorylated CEACAM3 strongly associated with the recombinant GST-SH2 domains of PI3K, Nck2, Hck, Yes, and Lck (Fig. 1, C and D). In contrast to GST pull-down analyses (9, 10), only weak interactions with the SH2 domains of Nck1 and Vav could be observed in this format. Clearly, there was no association of unphosphorylated CEACAM3 with any of the GST-SH2 domains or GST alone (Fig. 1, C and D). As expected, phosphorylated CEACAM3 showed no association with the SH2 domains of Grb2, Slp76, and Fyn or with GST alone (Fig. 1, C and D). In addition to known binding interactions, phosphorylated CEACAM3 showed a pronounced association with the SH2 domain of the adaptor protein Grb14, a member of the SH2 domain containing Grb7 family (Fig. 1, C and D). This interaction has not been described before. The verification of multiple known SH2 domain binding events to phosphorylated CEACAM3 demonstrated that the microarray detects relevant protein-protein interactions and suggested that Grb14 might be a novel binding partner of CEACAM3.

FIGURE 1.

SH2 domain microarray identifies Grb14 as an interaction partner of phosphorylated CEACAM3. A, different recombinant GST-SH2 domains, GST, or the spotting buffer (PBS) alone were immobilized in quadruplicate spots on aldehyde-modified glass slides as indicated in the array layout. Immobilized proteins were detected by monoclonal anti-GST antibody followed by Cy3-labeled secondary antibody. B, 293 cells were co-transfected with a vector encoding GFP-HA-tagged CEACAM3 together or not with v-Src. Equal amounts of whole cell lysates (WCLs) were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with monoclonal anti-GFP (top panel), or monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine (pTyr) (lower panel) antibodies. C, fluorescent images of SH2 arrays, probed with lysates from B. CEACAM3 bound to the array was detected by monoclonal anti-HA antibody followed by Cy3-labeled secondary antibody. D, plot shows the relative signals of phosphorylated CEACAM3 versus non-phosphorylated CEACAM3 binding to immobilized GST-fusion proteins. Bars represent mean values ± S.D. of quadruplicate spots from three independent experiments.

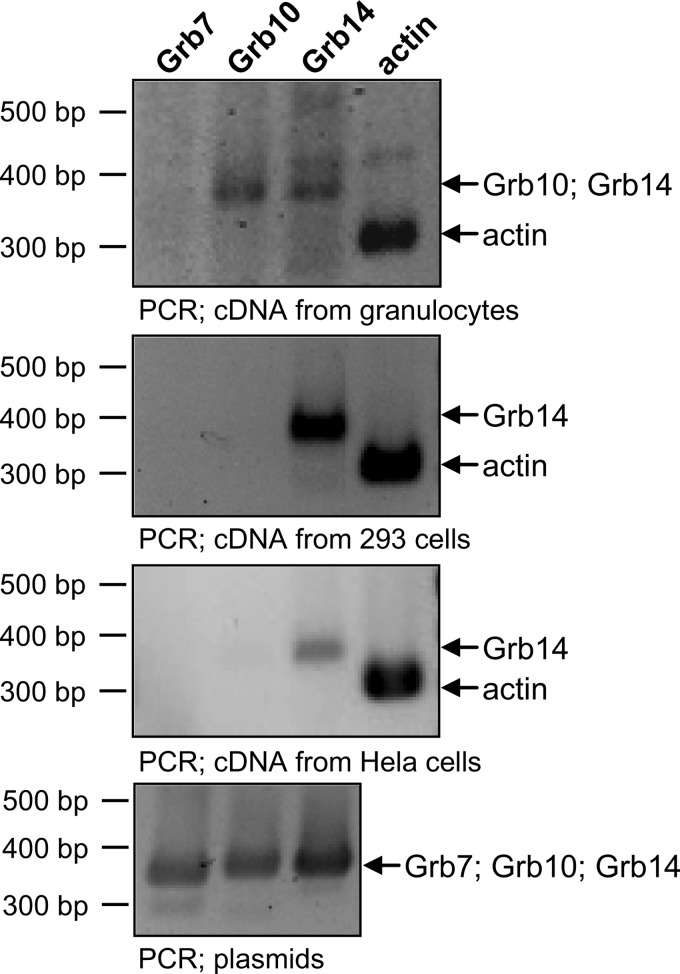

Grb14 Is Transcribed in Human Granulocytes

To investigate a potential physiological relevance of the Grb14-CEACAM3 interaction, the expression of Grb14 mRNA in human granulocytes was analyzed. For this purpose, RNA was extracted from primary human granulocytes followed by reverse transcription into cDNA and PCR with specific primer sets for each of three Grb7 family members. Importantly, Grb14 mRNA as well as Grb10 mRNA was present in human granulocytes (Fig. 2). In contrast, in 293 cells as well as in HeLa cells only the grb14 gene was transcribed (Fig. 2). To show that the used primer pairs are functional, PCR was performed using the full-length cloned cDNAs of Grb7, Grb10, and Grb14 obtained from ImaGenes (Berlin, Germany) as templates (Fig. 2, lowest panel). As a control for successful RNA preparation and cDNA generation, actin mRNA was detected in all samples (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Grb14 is expressed in human granulocytes, 293 cells, and HeLa cells. RNA was extracted from human granulocytes, 293 cells, and HeLa cells followed by reverse transcription into cDNA. The cDNA prepared from human granulocytes (first panel), 293 cells (second panel), and HeLa cells (third panel) were employed in PCR with specific primers for Grb7-, Grb10-, Grb14-, or actin-cDNA. Specificity of the PCR was verified using plasmids containing the indicated full-length cDNA (bottom panel).

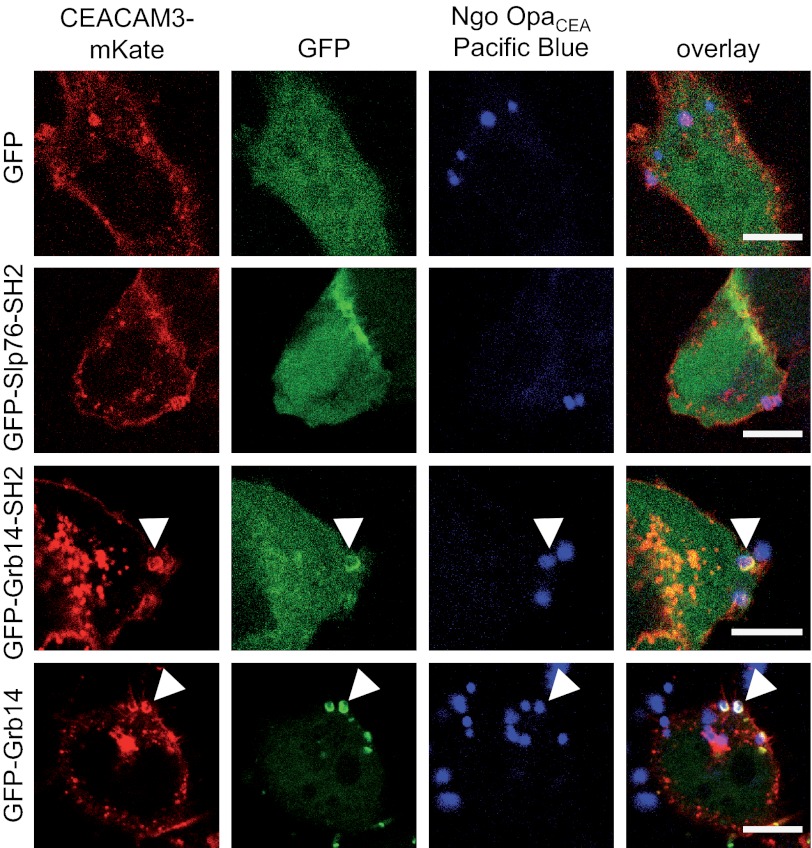

Grb14 Is Recruited to CEACAM3 upon Infection with CEACAM3-binding Bacteria

If the SH2 domain of Grb14 associates with the phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3, the adapter protein should be selectively recruited to the receptor upon bacterial binding. Therefore, we transfected 293 cells with constructs encoding CEACAM3 fused to mKate (CEACAM3-mKate) together with GFP-tagged full-length Grb14 (GFP-Grb14) or the isolated Grb14-SH2 domain (GFP-Grb14-SH2). Confocal microscopy revealed that the GFP-Grb14-SH2 domain as well as full-length GFP-Grb14 was strongly recruited to the sites, where OpaCEA protein expressing N. gonorrhoeae bound to CEACAM3 (Fig. 3). In contrast, GFP alone or the GFP-tagged SH2 domain of Slp76 was not recruited to CEACAM3 upon bacterial infection, in line with previous reports (Fig. 3) (17). These results demonstrate that Grb14 is recruited to clustered CEACAM3 after engagement by gonococci. These results further suggest that Grb14 can bind to the cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3.

FIGURE 3.

Grb14 is recruited to CEACAM3 upon infection with CEACAM3-binding bacteria. 293 cells were co-transfected with expression plasmids encoding for mKate-tagged wild type CEACAM3 (CEACAM3-mKate) together with GFP alone or the indicated GFP-tagged SH2-domains derived from Grb14, Slp76, or the full-length Grb14, respectively. Cells were infected for 30 min with PacificBlue-labeled OpaCEA protein-expressing N. gonorrhoeae (Ngo OpaCEA), fixed, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Bars represent 10 μm.

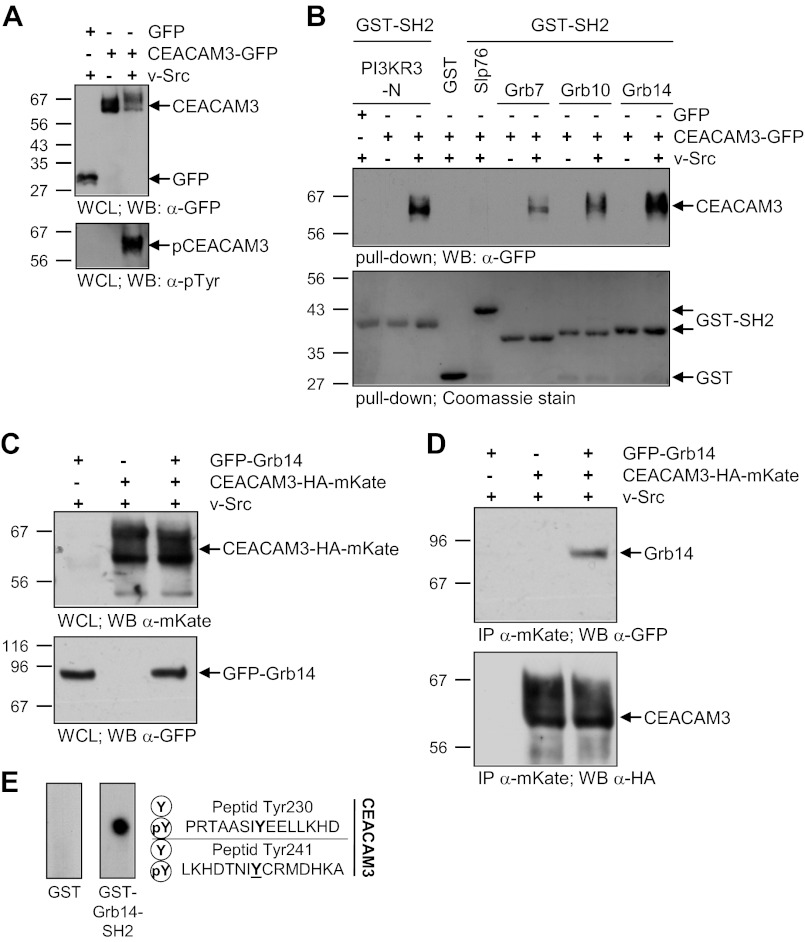

The SH2 Domain of Grb14 Directly Interacts with Phosphorylated CEACAM3

To investigate the interaction between Grb14 and CEACAM3 in more detail, we used GST-pull-down assays with the isolated SH2 domains of Grb7, Grb10, and Grb14, which were expressed in E. coli and purified. Next, 293 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding CEACAM3-GFP or GFP alone. To ensure maximum tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM3 in the lysates, same samples were co-transfected with a v-Src-encoding plasmid. CEACAM3-GFP and GFP were present in the cell lysates at similar levels (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, v-Src-mediated phosphorylation of CEACAM3 was verified by Western blotting (Fig. 4A). The lysates were probed with GST-fusion proteins of isolated SH2 domains of Grb7, Grb10, Grb14, PI3KR3-N, Slp76, or GST alone in GST pull-down assays. The N-terminal SH2 domain of the regulatory subunit γ of class I PI3K (PI3KR3-N-SH2) was previously shown to interact with phosphorylated CEACAM3 (12). Indeed GST-PI3KR3-N-SH2 was able to precipitate phosphorylated, but not unphosphorylated CEACAM3, whereas the Slp76-SH2 domain and GST alone could not precipitate CEACAM3 (Fig. 4B). Similarly, the SH2 domains of the Grb7 family were able to pull down phosphorylated CEACAM3 (Fig. 4B). The Grb14-SH2 domain showed the strongest association with phosphorylated CEACAM3.

FIGURE 4.

The SH2 domain of Grb14 interacts directly with phosphorylated CEACAM3. A, 293 cells were transfected with an empty control vector (GFP) or GFP-tagged CEACAM3 together or not with v-Src. The WCLs were analyzed by Western blotting for equal expression of CEACAM3 with mAb against GFP (top panel) and tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM3 was verified by mAb against phosphotyrosine (pTyr; lower panel). B, indicated recombinant GST-SH2 domains or GST alone were incubated in pull-down assays with lysates from A. Precipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with monoclonal GFP antibody to detect precipitated CEACAM3 (top panel). The membranes were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Coomassie) to verify equal amounts of GST or GST-fusion proteins used in the pull-down (lower panel). C, 293 cells were co-transfected with or without a vector encoding GFP-tagged Grb14 and a vector encoding mKate-HA-tagged CEACAM3 together with v-Src. Equal amounts of whole cell lysates (WCLs) were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with polyclonal anti-mKate (top panel) or monoclonal anti-GFP (lower panel) antibodies. D, lysates from C were used in an immunoprecipitation (IP) with pAb against mKate. Precipitates were probed with monoclonal anti-GFP antibody against GFP-Grb14 (top panel) and after stripping of the membrane, the immunoprecipitated CEACAM3-HA-mKate was detected with monoclonal anti-HA antibody (lower panel). E, peptide spot membranes harboring synthetic 15-mer peptides surrounding tyrosine residues of the CEACAM3 cytoplasmic domain (as indicated) in the unphosphorylated (Y) or the tyrosine-phosphorylated (pY) form were probed with GST or GST-Grb14-SH2. Bound GST-fusion proteins were detected with monoclonal anti-GST antibody.

To further analyze if full-length Grb14 associates with phosphorylated CEACAM3 in a cellular context, we performed co-immunoprecipitations. For this purpose, HA-mKate-tagged CEACAM3 and GFP-fused Grb14 were expressed in the presence of v-Src in 293 cells. Equal amounts of CEACAM3-HA-mKate and GFP-Grb14 were verified by Western blotting (Fig. 4C). Using a polyclonal anti-mKate antibody, the immunoprecipitation of CEACAM3-HA-mKate revealed an association between phosphorylated CEACAM3 and full-length Grb14 (Fig. 4D).

To clarify, which tyrosine residue within the CEACAM3 ITAM-like sequence is responsible for Grb14 association and to prove if this is a direct binding we used synthetic 15mer peptides encompassing each of the two tyrosine residues within the CEACAM3 ITAM-like sequence. The peptides were synthesized as individual spots on a cellulose membrane (22). Each peptide was produced in the phosphorylated form (pY), and the unphosphorylated form (Y). The membrane was incubated with recombinant GST-Grb14-SH2 domain or GST alone. After washing, the bound protein was detected by monoclonal GST antibody. The GST-Grb14-SH2 domain exclusively bound to the phosphorylated tyrosine residue pTyr-230, whereas there was no binding to the same peptide in the unphosphorylated form (Fig. 4E). In contrast, there was no binding of Grb14-SH2 to tyrosine residue Tyr-241, neither in the phosphorylated, nor in the unphosphorylated form (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, there was no binding of GST alone to any of the tested peptides (Fig. 4E).

Together, these results demonstrate that Grb14 physically associates with CEACAM3. This interaction occurs by direct binding of the Grb14 SH2 domain to the phosphorylated residue pTyr-230 within the ITAM-like sequence of CEACAM3.

Grb14-SH2 Directly Associates with CEACAM3 in Intact Cells

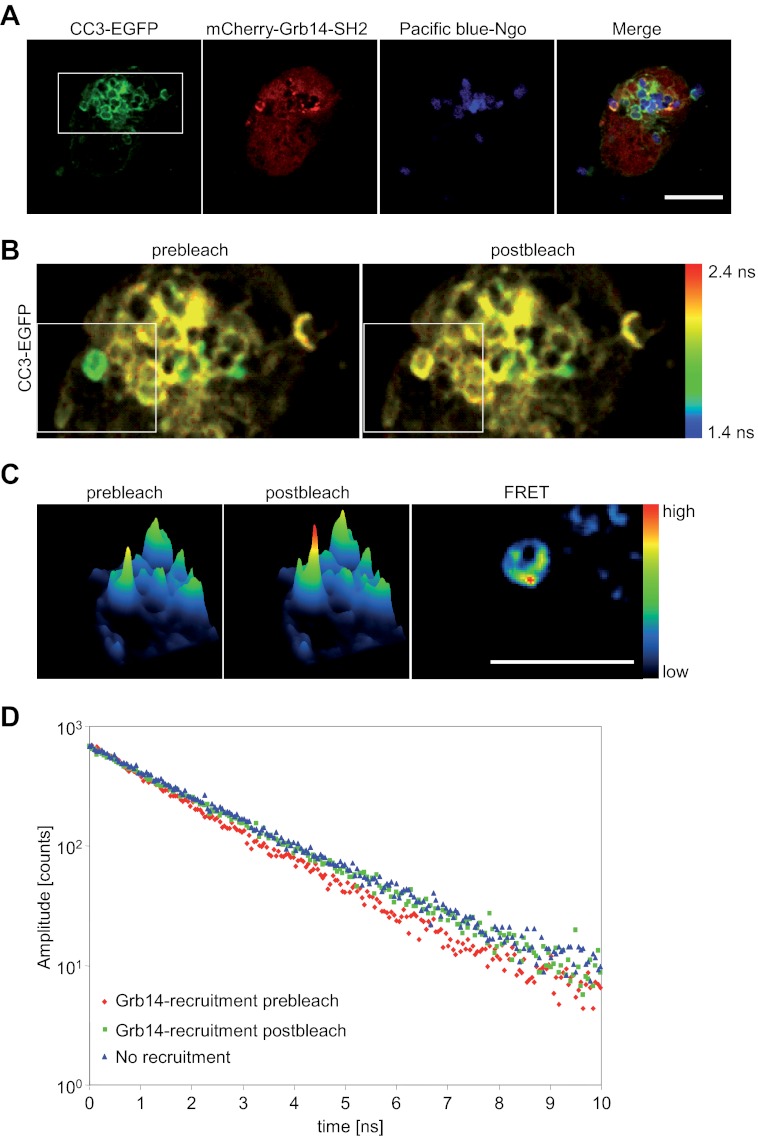

The previous results demonstrate a direct binding of recombinant Grb14-SH2 to the phosphorylated ITAM-like motif of CEACAM3 in vitro. To verify, that this interaction occurs in intact cells, we used FLIM to detect fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between CEACAM3 and Grb14. We could show previously that FRET allows the analysis of protein-protein interactions at the CEACAM3 cytoplasmic domain in intact cells (17). To allow FRET detection by FLIM, we used EGFP as a FRET-donor and mCherry as an acceptor. The EGFP-mCherry FRET pair is particularly suited for this type of analysis because of the single exponential fluorescence decay of EGFP in absence of the acceptor (23). In contrast, CFP, which is widely used together with YFP in intensity-based FRET approaches, shows double exponential fluorescence decay even in the absence of the YFP acceptor impeding calculation of fluorescence lifetimes and FRET efficiencies (24). As a standard reference, we first analyzed the EGFP lifetime of CEACAM3-EGFP transfected 293 cells in the absence of a FRET acceptor. As expected, we found a single exponential fluorescence decay with an EGFP lifetime of 2.10 ns (χ2 = 1.11) (data not shown). Subsequently, CEACAM3-EGFP was expressed together with a mCherry-Grb14-SH2 fusion protein. Cells were infected with PacificBlue-labeled OpaCEA expressing gonococci for 30 min and fixed (Fig. 5A). Strikingly, at sites where Grb14-SH2 colocalized with CEACAM3-bound bacteria the average EGFP fluorescence lifetime was reduced to 1.71 ns indicative of FRET between EGFP and mCherry at these sites.

FIGURE 5.

Grb14-SH2 intimately binds to CEACAM3 at sites of bacterial host cell contact. A, 293 cells were cotransfected to express wild type CEACAM3-EGFP and mCherry-Grb14-SH2. Two days later, cells were infected with PacificBlue-labeled OpaCEA protein-expressing gonococci (Ngo) for 30 min and fixed. Bar represents 10 μm. B, FLIM was applied to a defined region as indicated in A (white rectangle). The image represents the mean EGFP lifetime on a pixel-by-pixel basis and lifetime values are color-coded (see bar on the right). Distinct EGFP lifetimes were determined by fitting the fluorescence decay as described under the “Experimental Procedures.” C, images were recorded before and after photobleaching of the acceptor mCherry in a defined region (white rectangle in B) and analyzed for FRET. Bar represents 5 μm. D, fluorescence decay at sites of mCherry-Grb14-SH2 recruitment in comparison to regions with no recruitment or after photobleaching of the mCherry acceptor.

Analysis of the time resolved fluorescence data reveals a biexponential decay behavior with an additional decay component with a fluorescence lifetime of τ = 1.27 ns (χ2 = 0.90) (Fig. 5B, prebleach). Accordingly, the FRET efficiency between CEACAM3-GFP and Grb14-SH2-mCherry is 39.5% with 46.8% of CEACAM3 molecules associated with Grb14-SH2 under these conditions. In EGFP-positive regions without recruitment of the mCherry labeled SH2 domain, only a single lifetime was found (τ = 2.06 ns; χ2 = 0.92) that matched the fluorescence lifetime of EGFP measured in the absence of mCherry co-expression (Fig. 5B). As an internal control, we applied acceptor photobleaching to a defined region, where CEACAM3 was engaged by bacteria and colocalized with Grb14-SH2 (white rectangle in Fig. 5B). Exactly at the bacteria-host cell interface we observed a clear increase of the EGFP intensity after bleaching of mCherry, indicating FRET between the two fluorescence proteins and demonstrating intimate binding of Grb14-SH2 to CEACAM3 at these sites (Fig. 5C) with Eapp = 20.5%. This closely matches the FRET efficiency obtained from the FLIM measurements, which is 18.5%, when taking the proportion of interacting donor molecules into account. Furthermore, upon acceptor bleaching, FRET was abolished and only a single lifetime for EGFP was identified (τ = 2.05 ns; χ2 = 0.99) (Fig. 5, B and D). As additional controls for this microscopic approach, we analyzed infected cells expressing CEACAM3-EGFP together with mCherry-Slp76-SH2 or expressing CEACAM3 with a deletion of the cytoplasmic domain (CEACAM3ΔCT-EGFP) together with mCherry-Grb14-SH2, respectively. In line with our previous experiments (see Fig. 3), we did not observe colocalization of Slp76-SH2 with CEACAM3 or colocalization of Grb14-SH2 with CEACAM3ΔCT at bacterial binding sites (supplemental Fig. S1A). Furthermore, FLIM revealed single exponential fluorescence decays at sites where CEACAM3 was engaged by bacteria with τ = 2.11 ns (χ2 = 0.90) for CEACAM3 with Slp76-SH2 and τ = 2.10 ns (χ2 = 1.03) for CEACAM3ΔCT with Grb14-SH2 (supplemental Fig. S1B). Taken together, these results reveal an intimate, direct association of the SH2 domain of Grb14 with tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM3 in intact cells, exactly at the subcellular sites, where gonococci engage their host receptor.

Grb14 Is Involved in CEACAM3-mediated Phagocytosis

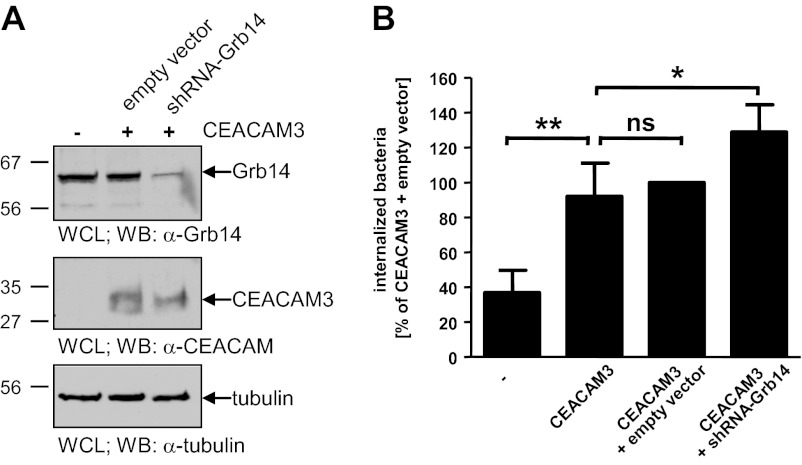

After our detailed analyses of Grb14 binding to pTyr230 of CEACAM3, we wanted to test if Grb14 is functionally involved in bacterial uptake via CEACAM3. Therefore, we chose RNA interference (RNAi) by short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) to deplete Grb14. Accordingly, CEACAM3-expressing HeLa cells were stably transduced with lentiviral particles encoding a shRNA directed against human Grb14. As a control, HeLa CEACAM3 cells were stably transduced with lentiviral particles lacking a shRNA sequence (control virus). Compared with untransduced and control virus transduced cells, knock-down of Grb14 in the shGrb14 cell population was nearly complete and reduced the amount of endogenous Grb14 to about 10% (Fig. 6A, upper panel). Importantly, CEACAM3 expression was not influenced by the viral transduction (Fig. 6A, middle panel). Next, HeLa cells and HeLa CEACAM3 cells with or without Grb14 knock-down were infected with OpaCEA-expressing gonococci and the amount of intracellular bacteria was determined. Significantly, knock-down of Grb14 resulted in an increase in CEACAM3-mediated uptake of gonococci by 30% compared with untransduced or control transduced CEACAM3-expressing HeLa cells (Fig. 6B). Regular HeLa cells, which do not express any CEACAM member endogenously, showed only minor internalization of gonococci (Fig. 6B). These data support the idea that Grb14 has a negative regulatory role during CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis. Together with the biochemical and microscopic analyses, these results suggest that SH2 domain-mediated binding of Grb14 to the ITAM-like sequence inhibits CEACAM3-mediated uptake of bacteria.

FIGURE 6.

Knock-down of Grb14 increases CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis. A, Grb14 expression in HeLa-CEACAM3 cells and HeLa-CEACAM3 cells transduced with empty lentiviral particles (empty vector) or with lentiviral particles encoding a Grb14-directed shRNA (shRNA-Grb14) was analyzed by Western blotting using polyclonal anti-Grb14 antibody (top panel). Expression of CEACAM3 was detected with monoclonal anti-CEACAM antibody (middle panel). After stripping of the membrane, equal protein content of all samples was verified using an anti-tubulin antibody (lower panel). B, HeLa cells, untransduced HeLa-CEACAM3 cells (CEACAM3), and HeLa-CEACAM3 cells transduced with the empty vector or with shRNA-Grb14 were infected with fluorescein-labeled OpaCEA protein-expressing N. gonorrhoeae (MOI 20). After 60 min, bacterial uptake was measured by flow cytometry. Fluorescence of extracellular, cell-associated bacteria was quenched by addition of trypan blue. Bars represent mean values ± S.D. of four separate experiments. n.s., not significant; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

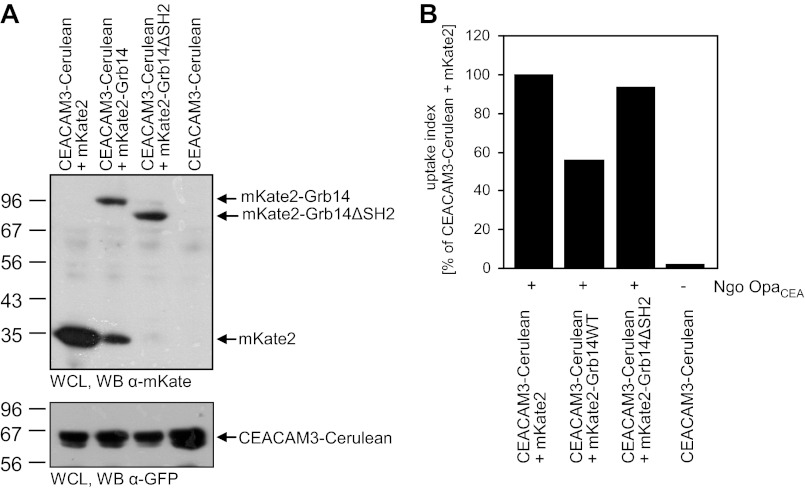

Grb14 SH2 Domain Is Critical for Negative Regulation of CEACAM3-mediated Phagocytosis

Biochemical approaches as well as FLIM analysis clearly demonstrate a Grb14-SH2 domain-mediated binding to the phosphorylated CEACAM3 ITAM-like motif. In order to investigate if this SH2 domain-mediated interaction is linked to the negative regulation of CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis by Grb14, we co-transfected 293 cells with expression plasmids for mKate2, mKate2-tagged wild type Grb14, or a deletion mutant of Grb14 lacking the SH2-domain (Grb14ΔSH2) together with CEACAM3-Cerulean. Equal expression of CEACAM3 and expression of the different Grb14 constructs was verified by Western blotting (Fig. 7A). Cells were infected with OpaCEA-expressing gonococci and phagocytosis was quantified by flow cytometry (Fig. 7B). In line with the increased CEACAM3-mediated uptake in Grb14-depleted cells, internalization of bacteria was strongly decreased in case of Grb14 overexpression compared with mKate2-expressing control cells (Fig. 7B). In contrast, co-expression of Grb14ΔSH2 did not influence CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis (Fig. 7B). This result indicates that the inhibitory effect of Grb14 requires the SH2-domain-mediated binding of the adaptor protein to phosphorylated CEACAM3.

FIGURE 7.

The Grb14 SH2-domain is critical for negative regulation of CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis. A, 293 cells were cotransfected with Cerulean-tagged CEACAM3 together with the indicated mKate2-tagged constructs. Two days later, whole cell lysates (WCL) of the cells were analyzed by Western blotting to verify expression of mKate2, mKate2-Grb14, and mKate2-Grb14ΔSH2 (top panel) as well as expression of CEACAM3-cerulean (bottom panel). B, cells transfected as in A were infected with fluorescein-labeled OpaCEA protein-expressing gonococci (MOI 20) for 1 h. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry by gating on cerulean-positive cells. Fluorescence of extracellular, cell-associated bacteria was quenched by addition of trypan blue, and the fluorescein signal derived from intracellular bacteria was quantified. Shown is a representative experiment repeated twice with similar results.

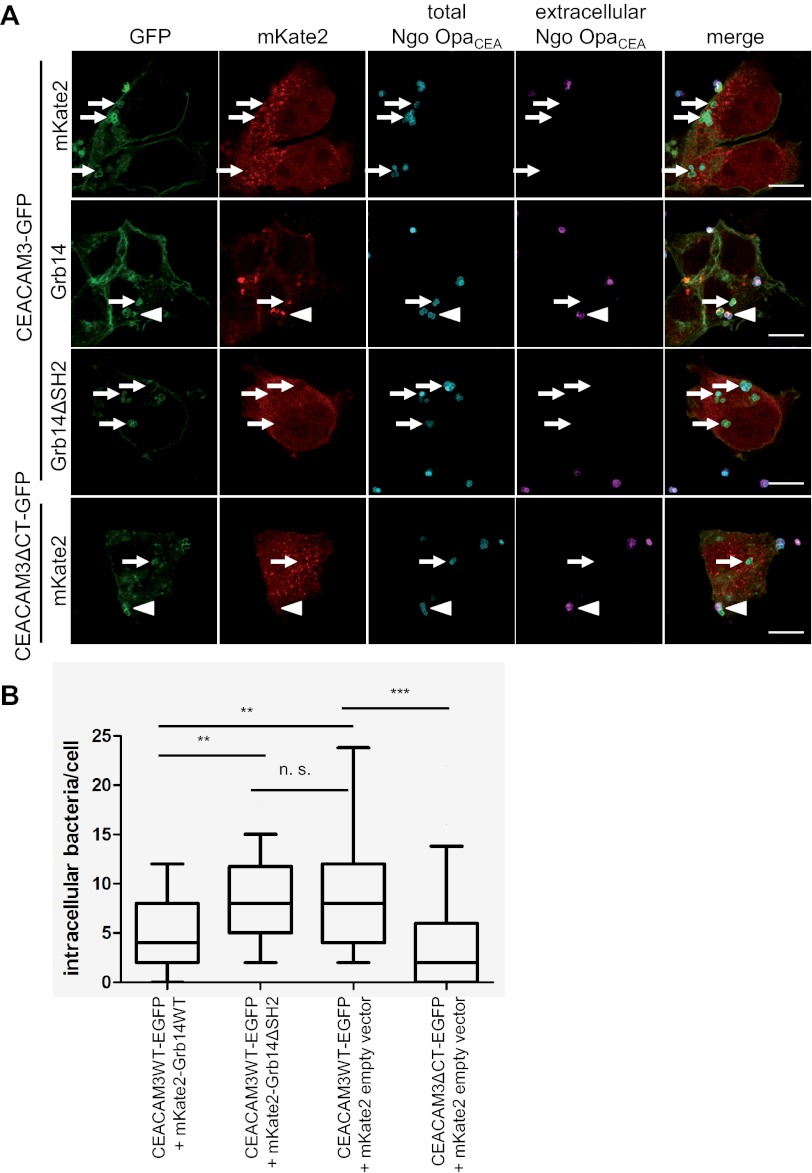

To corroborate this finding, 293 cells co-expressing CEACAM3-GFP together with either wild type Grb14 or Grb14ΔSH2 were infected with PacificBlue-labeled OpaCEA-expressing gonococci. As a further control, we employed cells expressing a mutant form of CEACAM3, which lacks the cytoplasmic domain (CEACAM3ΔCT-GFP). 1 h after infection, samples were fixed and extracellular gonococci were stained with a Neisseriae-specific antibody and a Cy5-labeled secondary antibody (Fig. 8A). As observed before (3), hardly any intracellular bacteria were detected in CEACAM3ΔCT-transfected cells co-expressing mKate, whereas wild type CEACAM3 promoted uptake of bacteria (Fig. 8A). In these wild type CEACAM3 and mKate2-expressing cells, on average 8 bacteria/cell were found intracellularly (Fig. 8B). Importantly, a 50% reduction in intracellular gonococci was detected in cells co-expressing CEACAM3 together with wild type Grb14. In contrast, CEACAM3 and Grb14ΔSH2-expressing cells displayed the same number of intracellular bacteria as CEACAM3 and mKate2-expressing cells (Fig. 8B). Together, these results confirm the critical role of the Grb14 SH2 domain to connect Grb14 with CEACAM3 and further confirm that Grb14 is a negative regulator of CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis.

FIGURE 8.

The SH2-domain is required for Grb14 recruitment to CEACAM3 and inhibition of CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis. A, 293 cells were cotransfected with GFP-tagged CEACAM3 or GFP-tagged CEACAM3ΔCT together with mKate2, mKate2-Grb14, or mKate2-Grb14ΔSH2 as indicated. 293 cells expressing the indicated constructs were infected with PacificBlue-labeled gonococci (total Ngo OpaCEA) at an MOI of 30 for 1 h. Cells were fixed and extracellular bacteria were stained with polyclonal antibody against gonococci and a Cy5-labeled secondary antibody (extracellular Ngo OpaCEA). Arrowheads indicate extracellular bacteria, small arrows point to internalized bacteria. Bars represent 10 μm. B, quantification of bacterial invasion from A. Boxes indicate the 25/75 percentiles and the median (black line) of the internalized bacteria per cell from three independent experiments. The 10/90 percentiles are indicated by the error bars. Statistical significance was evaluated by Wilcoxon's signed rank test (n = 60). n.s., not significant; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

CEACAM3 mediates rapid and efficient opsonin-independent phagocytosis of CEACAM-binding bacteria by human granulocytes. Several positive regulators of CEACAM3-initiated cellular events have been characterized, which are connected to the ITAM-like sequence of CEACAM3 and promote bacterial uptake in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner (11).

Here we demonstrate that CEACAM3 can interact with the adaptor protein Grb14. This interaction is mediated by a direct binding of the Grb14 SH2 domain to phosphorylated Tyr-230 (pTyr-230) within the ITAM-like sequence of CEACAM3. FLIM-based FRET measurements corroborate the initial biochemical analyses and verify that CEACAM3 can interact with Grb14 in intact cells. The CEACAM3-Grb14 interaction is triggered upon receptor engagement by bacteria and results in local accumulation of Grb14. Importantly, functional assays demonstrate that the SH2-mediated association of Grb14 with the receptor has an inhibitory effect on bacterial internalization and restricts CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis.

Our investigation took advantage of the miniaturized and highly parallel determination of protein-protein interactions afforded by protein domain microarrays (14). Using a panel of recombinant SH2 domains we could indeed verify known protein interactions with phosphorylated CEACAM3 such as the binding of SH2 domains derived from the Src family kinase Hck, the adaptor protein Nck, or the regulatory subunit of PI3K (11). Strikingly, we were able to detect these interactions upon probing of the SH2 domain microarray with complex whole cell lysates containing the full-length receptor. This application clearly expands the use of protein domain microarrays beyond the classical approach, which employed synthetic phospho-peptides (15, 16). In principle, the probing of SH2 domain microarrays with whole cell lysates and the use of differentially labeled antibodies against candidate binding partners would not only allow multiplexed analysis, but also the detection of novel, phosphotyrosine-based protein-protein interactions. Indeed, using the SH2 domain microarray, we observed the binding of the Grb14 SH2 domain to phosphorylated CEACAM3, an interaction, which has not been reported before.

Grb14 is one of three members of the Grb (growth factor receptor-bound) 7 family comprising Grb7, Grb10, and Grb14 (25). Compared with the adaptor protein Grb2, the Grb7 family proteins have distinct domain structures and functions. They consist of an N-terminal proline-rich (PP) motif, a central region containing a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, a C-terminal SH2 domain and a so-called Between PH and SH2 (BPS) domain (25). Grb14 was initially discovered by its ability to bind to the phosphorylated C-terminal domain of the EGF receptor (26). Grb14 is expressed in most tissues, including myeloid cells, and has been found to associate with several activated growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases such as the EGF receptor, FGF receptor, PDGF receptor, and insulin receptor (IR) (27). In particular, the role of Grb14 in IR signaling has been studied in detail. In vitro, Grb14 binding to tyrosine residues in the activation loop of the IR kinase domain interfere with the catalytic activity of the IR (28).

Interestingly, the isolated BPS domain alone is sufficient to mediate the inhibitory effect on IR activity in vitro (28). However, the SH2 domain is needed to localize full-length Grb14 to the IR and to position the BPS domain in the substrate binding groove of the IR to function as a pseudosubstrate and to suppress IR activity (29). Surprisingly, grb14 knock out mice (Grb14−/− mice) do not show overt alterations with regard to size and weight compared with wild type mice (30). However, an enhanced insulin signaling in muscle and liver tissues coupled with improved glucose homeostasis has been observed in Grb14−/− mice, suggesting that Grb14 fine tunes IR-dependent responses (30). Unfortunately, mice do not express a CEACAM3 orthologue and murine CEACAM family members, though the target of murine hepatitis virus (31, 32), do not serve as receptors for human-restricted bacteria, which exclusively bind to human members of the CEACAM family (33). Therefore, Grb14−/− mice or cells derived from these animals cannot be used to decipher CEACAM3 signaling.

Nevertheless, the RNAi-mediated knock-down of Grb14 provided a loss-of-function scenario, where the reduced expression of Grb14 resulted in enhanced CEACAM3-mediated uptake. Moreover, upon overexpression of Grb14, we observed an inhibitory function for Grb14 in CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis of N. gonorrhoeae. Consistent with the known structure-function relationship of Grb14 in growth factor receptor signaling, only expression of full-length Grb14 inhibited CEACAM3-mediated bacterial uptake and deletion of the Grb14-SH2 domain abolished this effect. We currently do not know if in addition to the SH2 domain the BPS domain is also required for this inhibitory function. However, signaling by cytoplasmic PTKs is needed to drive efficient phagocytosis via CEACAM3, and such PTKs could be a target of the Grb14 BPS domain. Furthermore, our experiments with recombinant SH2 domains and synthetic phospho-peptides suggest that Grb14 binds to pTyr-230 within the CEACAM3 cytoplasmic domain. To date, several positive regulators of CEACAM3-mediated uptake, e.g. Vav1 and Src-kinases, are known, which also bind via their SH2 domains to this particular tyrosine residue. As a single tyrosine residue within the ITAM-like sequence supports multiple protein-protein interactions critical for phagocytosis, we have suggested that the CEACAM3 cytoplasmic domain possesses a hemITAM functionality (11). Such a tyrosine-based activation motif centered around a single tyrosine residue has been characterized for the macrophage receptor Dectin-1, which initiates opsonin-independent phagocytosis of dextran-exposing particles including yeast (34). Because of the importance of the phosphorylated tyrosine residue pY230, Grb14 SH2 domain binding might interfere with CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis by blocking access of other proteins to this residue. Therefore, both inhibition of CEACAM3-associated PTKs by the Grb14 BPS domain as well as competition with other SH2-domain containing proteins for pY230 binding could limit CEACAM3-downstream signaling and could explain the reduced opsonin-independent phagocytosis of CEACAM-binding bacteria in the presence of Grb14.

How the association of different SH2 domain containing proteins, having either positive or negative regulatory function, with a single phosphotyrosine residue in CEACAM3 is coordinated, is currently unclear. On the one hand, binding of the 1 μm sized N. gonorrhoeae to host cells triggers the clustering of multiple CEACAM3 molecules (3, 17). The clustered receptor molecules could then accommodate the simultaneous association with several different pTyr-230-binding proteins at a given time point. On the other hand, a sequential and hierarchical recruitment of the different cytoplasmic binding partners to pTyr-230 of CEACAM3 is highly likely. Indeed, a transient association of CEACAM3 and the Hck-SH2 domain was observed (17). Upon CEACAM3 engagement by OpaCEA-expressing N. gonorrhoeae, the Hck-SH2 domain is initially recruited to the receptor and disappears again within 5–10 min, while the bacteria stay associated with the receptor in an intracellular compartment (17). Co-localization studies using live cell imaging would allow the visualization of multiple SH2-domains to CEACAM3. However, such studies do not discriminate between indirect and direct receptor association. Therefore, advanced fluorescence microscopy approaches such as FRET determination are required to clearly resolve the spatial and temporal pattern of protein binding to the hemITAM of CEACAM3. In this regard, application of FRET-FLIM does not only demonstrate the intimate association of a recruited protein, but also directly provides quantitative data about the stoichiometry of the interaction. This is in contrast to intensity-based FRET-methods, where quantification of interaction partners is highly sophisticated and requires the availability of appropriate controls (35). Using the quantitative determination of fluorescence lifetime of the FRET donor GFP, we calculated that almost half of the CEACAM3 molecules during a bacterial internalization event were bound to Grb14-SH2. As we had to employ fixed samples and overexpression of mCherry-Grb14-SH2, this clearly represents only a snap-shot of a non-physiological setting. Expression of the fluorescently tagged full-length protein at physiological levels in combination with live cell FLIM would allow a more precise quantification of CEACAM3-binding by a given protein. However, as the acquisition time for the time-correlated single photon-counting-FLIM setup was in the range of minutes to obtain reliable donor lifetimes, we were not able to analyze phagocytosis-related signaling in living cells. Accordingly, FLIM instrumentation determining fluorophore lifetime in the frequency domain could allow faster image acquisition and might be preferable to elucidate the temporal succession of CEACAM3 binding partners (36).

From our studies, Grb14 emerges as a non-enzymatic, negative regulator of the phagocytic receptor CEACAM3. Though Grb14 and CEACAM3 are expressed by human granulocytes, it is difficult to verify the functional interaction of these two proteins in primary cells. This is mainly due to the inaccessibility of human granulocytes for genetic manipulation by recombinant cDNA or shRNA constructs. Furthermore, murine granulocytes, which could be isolated from wild type and Grb14−/− mice, do not express CEACAM3 (37). The generation of transgenic mice expressing CEACAM3 under the control of a granulocyte specific promoter might be a promising route to allow future functional investigations of CEACAM3-binding partners in the proper cellular context. Nevertheless, previous studies using pharmacological inhibitors or cell-permeable function-blocking peptides have provided convincing evidence that CEACAM3-expressing 293 cells are relevant surrogates for primary granulocytes with regard to CEACAM3-mediated bacterial uptake (3, 6, 9, 12).

Together, our study reveals a novel and direct interaction between the adaptor protein Grb14 and the tyrosine-phosphorylated cytoplasmic domain of CEACAM3. Our functional analyses suggest that this SH2-domain-based interaction between Grb14 and the receptor limits CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis and fine tunes the uptake of CEACAM-binding bacteria and cellular responses by human granulocytes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Oliver Griesbeck (Max-Planck Institute of Neurobiology, Martinsried, Germany) for mCherry cDNA, N.I. Dierdorf for help with lentivirus production, as well as S. Feindler-Boeckh and S. Daenicke for expert technical assistance.

This study was supported by funds from the Landesstiftung BW (LS-Prot-66) and by a grant from the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of Baden-Württemberg (CAP17) (to C. R. H.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- CEA

- carcinoembryonic antigen

- ITAM

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

- PTB

- phosphotyrosine-binding

- SH

- Src homology

- FLIM

- fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy

- TCSPC

- time-correlated single photon counting

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- CEACAM

- carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule

- PTK

- protein tyrosine kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pils S., Gerrard D., Meyer A., Hauck. C. R. (2008) Intl. J. Med. Microbiol. 298, 553–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen T., Gotschlich E. C. (1996) CGM1a antigen of neutrophils, a receptor of gonococcal opacity proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 14851–14856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmitter T., Agerer F., Peterson L., Munzner P., Hauck C. R. (2004) Granulocyte CEACAM3 is a phagocytic receptor of the innate immune system that mediates recognition and elimination of human-specific pathogens. J. Exp. Med. 199, 35–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCaw S. E., Schneider J., Liao E. H., Zimmermann W., Gray-Owen S. D. (2003) Immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif phosphorylation during engulfment of Neisseria gonorrhoeae by the neutrophil-restricted CEACAM3 (CD66d) receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 49, 623–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hauck C. R., Meyer T. F., Lang F., Gulbins E. (1998) CD66-mediated phagocytosis of Opa52 Neisseria gonorrhoeae requires a Src-like tyrosine kinase- and Rac1-dependent signaling pathway. EMBO J. 17, 443–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmitter T., Pils S., Weibel S., Agerer F., Peterson L., Buntru A., Kopp K., Hauck C. R. (2007) Opa proteins of pathogenic neisseriae initiate Src kinase-dependent or lipid raft-mediated uptake via distinct human carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule isoforms. Infect. Immun. 75, 4116–4126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pawson T., Gish G. D., Nash P. (2001) SH2 domains, interaction modules and cellular wiring. Trends Cell Biol. 11, 504–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schlessinger J., Lemmon M. A. (2003) SH2 and PTB domains in tyrosine kinase signaling. Sci. STKE. 2003, RE12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schmitter T., Pils S., Sakk V., Frank R., Fischer K. D., Hauck C. R. (2007) The granulocyte receptor carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 3 (CEACAM3) directly associates with Vav to promote phagocytosis of human pathogens. J. Immunol. 178, 3797–3805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pils S., Kopp K., Peterson L., Delgado-Tascón J., Nyffenegger-Jann N. J., Hauck C. R. (2012) The adaptor molecule Nck localizes the WAVE complex to promote actin polymerization during CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis of bacteria. PLoS One 7, e32808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buntru A., Roth A., Nyffenegger-Jann N. J., Hauck C. R. (2012) HemITAM signaling by CEACAM3, a human granulocyte receptor recognizing bacterial pathogens. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 524, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buntru A., Kopp K., Voges M., Frank R., Bachmann V., Hauck C. R. (2011) Phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase activity is critical for initiating the oxidative burst and bacterial destruction during CEACAM3-mediated phagocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 9555–9566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu B. A., Jablonowski K., Raina M., Arcé M., Pawson T., Nash P. D. (2006) The human and mouse complement of SH2 domain proteins-establishing the boundaries of phosphotyrosine signaling. Mol. Cell 22, 851–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wolf-Yadlin A., Sevecka M., MacBeath G. (2009) Dissecting protein function and signaling using protein microarrays. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 13, 398–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones R. B., Gordus A., Krall J. A., MacBeath G. (2006) A quantitative protein interaction network for the ErbB receptors using protein microarrays. Nature 439, 168–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehlitz A., Banhart S., Mäurer A. P., Kaushansky A., Gordus A. G., Zielecki J., Macbeath G., Meyer T. F. (2010) Tarp regulates early Chlamydia-induced host cell survival through interactions with the human adaptor protein SHC1. J. Cell Biol. 190, 143–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buntru A., Zimmermann T., Hauck C. R. (2009) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based subcellular visualization of pathogen-induced host receptor signaling. BMC Biol. 7, 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hauck C. R., Hunter T., Schlaepfer D. D. (2001) The v-Src SH3 domain facilitates a cell adhesion-independent association with focal adhesion kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17653–17662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kupsch E. M., Knepper B., Kuroki T., Heuer I., Meyer T. F. (1993) Variable opacity (Opa) outer membrane proteins account for the cell tropisms displayed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae for human leukocytes and epithelial cells. EMBO J. 12, 641–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pils S., Schmitter T., Neske F., Hauck C. R. (2006) Quantification of bacterial invasion into adherent cells by flow cytometry. J. Microbiol. Methods 65, 301–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuespert K., Roth A., Hauck C. R. (2011) Neisseria meningitidis has two independent modes of recognizing its human receptor CEACAM1. PLoS One 6, e14609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frank R. (1992) Spot-synthesis: an easy technique for the positionally addressable, parallel chemical synthesis on a membrane support. Tetrahedron 48, 9217–9232 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peter M., Ameer-Beg S. M., Hughes M. K., Keppler M. D., Prag S., Marsh M., Vojnovic B., Ng T. (2005) Multiphoton-FLIM quantification of the EGFP-mRFP1 FRET pair for localization of membrane receptor-kinase interactions. Biophys. J. 88, 1224–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tramier M., Gautier I., Piolot T., Ravalet S., Kemnitz K., Coppey J., Durieux C., Mignotte V., Coppey-Moisan M. (2002) Picosecond-hetero-FRET microscopy to probe protein-protein interactions in live cells. Biophys. J. 83, 3570–3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Han D. C., Shen T. L., Guan J. L. (2001) The Grb7 family proteins: structure, interactions with other signaling molecules and potential cellular functions. Oncogene 20, 6315–6321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Daly R. J., Sanderson G. M., Janes P. W., Sutherland R. L. (1996) Cloning and characterization of GRB14, a novel member of the GRB7 gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 12502–12510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holt L. J., Siddle K. (2005) Grb10 and Grb14: enigmatic regulators of insulin action–and more? Biochem. J. 388, 393–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Béréziat V., Kasus-Jacobi A., Perdereau D., Cariou B., Girard J., Burnol A. F. (2002) Inhibition of insulin receptor catalytic activity by the molecular adapter Grb14. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4845–4852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Depetris R. S., Hu J., Gimpelevich I., Holt L. J., Daly R. J., Hubbard S. R. (2005) Structural basis for inhibition of the insulin receptor by the adaptor protein Grb14. Mol. Cell 20, 325–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cooney G. J., Lyons R. J., Crew A. J., Jensen T. E., Molero J. C., Mitchell C. J., Biden T. J., Ormandy C. J., James D. E., Daly R. J. (2004) Improved glucose homeostasis and enhanced insulin signaling in Grb14-deficient mice. EMBO J. 23, 582–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dveksler G. S., Dieffenbach C. W., Cardellichio C. B., McCuaig K., Pensiero M. N., Jiang G. S., Beauchemin N., Holmes K. V. (1993) Several members of the mouse carcinoembryonic antigen-related glycoprotein family are functional receptors for the coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus-A59. J. Virol. 67, 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hemmila E., Turbide C., Olson M., Jothy S., Holmes K. V., Beauchemin N. (2004) Ceacam1a−/− mice are completely resistant to infection by murine coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus A59. J. Virol. 78, 10156–10165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Voges M., Bachmann V., Kammerer R., Gophna U., Hauck C. R. (2010) CEACAM1 recognition by bacterial pathogens is species-specific. BMC Microbiol. 10, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goodridge H. S., Reyes C. N., Becker C. A., Katsumoto T. R., Ma J., Wolf A. J., Bose N., Chan A. S., Magee A. S., Danielson M. E., Weiss A., Vasilakos J. P., Underhill D. M. (2011) Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a phagocytic synapse. Nature 472, 471–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoppe A., Christensen K., Swanson J. A. (2002) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based stoichiometry in living cells. Biophys. J. 83, 3652–3664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gratton E., Breusegem S., Sutin J., Ruan Q., Barry N. (2003) Fluorescence lifetime imaging for the two-photon microscope: time-domain and frequency-domain methods. J. Biomed. Opt. 8, 381–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kammerer R., Zimmermann W. (2010) Coevolution of activating and inhibitory receptors within mammalian carcinoembryonic antigen families. BMC Biology 8, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]