Abstract

Evolutionary protein engineering has been dramatically successful, producing a wide variety of new proteins with altered stability, binding affinity, and enzymatic activity. However, the success of such procedures is often unreliable, and the impact of the choice of protein, engineering goal, and evolutionary procedure is not well understood. We have created a framework for understanding aspects of the protein engineering process by computationally mapping regions of feasible sequence space for three small proteins using structure-based design protocols. We then tested the ability of different evolutionary search strategies to explore these sequence spaces. The results point to a non-intuitive relationship between the error-prone PCR mutation rate and the number of rounds of replication. The evolutionary relationships among feasible sequences reveal hub-like sequences that serve as particularly fruitful starting sequences for evolutionary search. Moreover, genetic recombination procedures were examined, and tradeoffs relating sequence diversity and search efficiency were identified. This framework allows us to consider the impact of protein structure on the allowed sequence space and therefore on the challenges that each protein presents to error-prone PCR and genetic recombination procedures.

Introduction

The observation that proteins can be evolved to fulfill different functional roles has been harnessed as a fundamental technology by protein engineers and has had considerable practical application in medicine, industry, and basic science. Laboratory protocols have been developed for evolutionary experiments in which rounds of sequence variation are followed by selecting or screening for desired activity, sometimes in an iterative fashion (1–3). While this class of approaches has produced change-of-function variants with important properties across a variety of application areas, success is by no means guaranteed. The same design goal is generally not performed repeatedly in the same laboratory or between laboratories either with the same or different procedures, so it is difficult to judge the uniqueness of the results and the robustness of the procedures. Nevertheless, there is a sense that the success of these procedures varies between projects and design goals, and it is unclear the extent to which this variability reflects differences in the challenges attempted, in the technology applied, in the sizes or properties of the space of protein sequences searched, or something about the fundamental adaptability or designability of the parent protein. The mutation rate and protocol in the variation procedure influence the distribution of both DNA and protein sequences created, and the screening or selection capabilities limit the number of sequences that can be examined. These factors combine to impact the efficiency of the sequence space search and the likelihood of discovery of a new protein variant with desired properties.

Methods for protein engineering include computational approaches and experimental techniques, as well as hybrids of the two. Computational protein design methods include structure-based modeling of detailed electrostatics, packing, and other interactions, as well as data mining in sequence space (4–7). Computation has also been used to address the designability question, where both atomistic and lattice models have been used to estimate the number of sequences that will fold to a given protein structure (8, 9). While this metric does tell us something about designability, it does not address the accessibility of each of these sequences by standard experimental techniques. Computation has also been used to simulate evolutionary engineering experiments, such as error-prone PCR and gene shuffling, and has provided valuable insights into the effects of experimental parameter variation on the efficiency of the sequence space search (10–12). The current work combines the computational identification of feasible sequences with simulations of evolutionary engineering procedures to address the relative effectiveness of techniques for evolutionary search of sequence space.

Experimental laboratory evolution approaches, at least in principle, can be used to engineer any new function for which there is a screen or selection. They have been applied successfully to modify protein stability, binding affinity and specificity, and enzymatic properties such as catalytic rates, substrates accepted, reactions catalyzed, stereoselectivity, and operating conditions (1–3, 13, 14). Applied to proteins, different laboratory evolution techniques use one or more DNA sequences as substrate for a partial randomization procedure that results in a large library of sequences. The DNA-level genotype of each sequence is physically linked to the protein-level phenotype to enable sequencing of the gene associated with the newly isolated protein activity. Experimental platforms for the selection or screening step of laboratory evolution include cell surface display (on yeast or bacteria) (15–17), phage display (18, 19), mRNA display (20), ribosome display (21), and in vitro compartmentalization (22). Cells have also been used for in vivo compartmentalization when the goal protein function is linked to cellular metabolism (23–24) or fluorescence (25–27). Each of these systems has been used as the foundation for an assay for screening randomized sequence libraries that have been generated by error-prone PCR, genetic recombination, saturation mutagenesis, or by computational protein design. Although the number of unique sequences that can be screened by each assay is not well established, currently not more than 1015 sequences can be examined in one experiment, and typical effective experimental capacity is probably significantly lower, perhaps 106–108. Error-prone PCR randomization strategies generally make low numbers of DNA mutations because a low mutation rate has been shown to typically maximize the number of functional results (28–30). A range of rates is possible experimentally (31), however, and some laboratories have found higher mutation rates to be beneficial (32, 33). Genetic recombination, focused mutagenesis, and computational design techniques can have higher mutation rates and can locate design solutions more distant from wild type (23, 34–38).

In hybrid computational–experimental studies, computational methods have been used as the sequence variation step for evolutionary engineering approaches (24, 39) and to select crossover sites for recombination in gene shuffling experiments (40, 41). They have also been used to choose residue positions most likely to accept mutation (42, 43). Our work serves as a new and complementary approach, using computationally designed sequences to guide evolutionary experiments toward feasible portions of the sequence space.

A useful framing for studying different evolutionary protein engineering approaches identifies a search space (for example, all the sequences explicitly considered), which can be characterized by its size as well as other properties; the framing also identifies the mechanism of effecting the search in this space. It could be critical to evaluate the thoroughness of a search (e.g., the fraction of the potential search space actually examined) as well as its diversity (e.g., the relative differences among the sequences searched; the distribution of goal sequences found within the search space). Each search technique includes a starting sequence or multiple starting sequences and eventually produces a set of protein sequences for screening or selection. The search mechanism biases the set of sequences created, and because no more than 1015 sequences can be screened (much less than the possible 20100 ≈ 10130 sequences possible for a protein with 100 residues), this bias influences the choice of the final engineered protein. A vanishingly small fraction of these 10130 sequences will have the new desired function, and so the distribution of desired protein variants in the sequence space is another important factor that is, in general, hard to quantify but relates to the difficulty of the engineering experiment.

We therefore ask how the biases of the randomization procedures influence the generation of diverse functional libraries and whether the expected locations of desired proteins in the search space point toward beneficial experimental sequence space search procedures. We analyze simulated error-prone PCR and genetic recombination experiments and explore how changes in experimental parameters can influence the efficiency of the sequence-space search for allowed sequences.

We develop and apply a model for evolutionary search to understand better the key factors affecting the search capabilities and outcome of evolutionary engineering experiments. This model includes a definition of the allowed sequences for a protein design problem, and we test the accessibility of these sequences in the search space by simulating different protein engineering experiments. Allowed sequences are defined as those computed to be stable on the wild-type crystal structure backbone fold. Simulated evolutionary experiments start from any allowed sequence, including the wild type, and we test the ability of each simulation to find these allowed sequences. Our representation of these foldable sequences is a “sequence-space graph” that depicts evolutionary paths between sequences. A node in this type of graph represents a protein sequence and for the present study an edge between two nodes indicates that only a single DNA mutation is required to interconvert encodings for those two protein sequences. Because protein folding is a prerequisite for function, an evolutionary search technique that locates many sequences computed to be foldable should also successfully generate sequences with new function. This principle of designing for a stable fold as a prerequisite for locating new function has been used successfully in the past, both computationally to design a beta-lactamase inhibitor and experimentally to design a cytochrome P450 enzyme family (24, 44).

We have computationally explored the sequence space computed to be foldable for three small proteins, allowing us to design, simulate, and evaluate strategies for protein engineering via directed evolution. The different backbone conformations of these proteins provide interesting constraints on the available sequences, influencing the possible evolutionary paths through the sequence space. Computer simulations of error-prone PCR and genetic recombination were used to explore these sequence spaces and demonstrated that using our sequence-space graphs to guide the choice of starting sequence can help generate more diverse libraries of foldable sequences. We explore the influence of mutation rate and number of rounds of mutation on error-prone PCR experiments and show that the effective diversity of the sequence library produced increases when the simulation starts from a sequence with more allowed proteins close by in mutational space (or sequence-space graph “hubs”). We also explore the relationship between the computed protein energy and its evolvability. Additionally, our model shows that foldable mutants with several changes from the starting sequence are more easily found by genetic recombination than by error-prone PCR but that the similarity between the allowed sequences for our chosen folds limits the possible number of mutations achievable by recombination. Finally, our work provides a framework for understanding and analyzing protein engineering techniques through the effect of structural and stability constraints, and for further exploring the variable success of protein design projects.

Results

Sequence-space graph topology

Sequence-space graph topologies vary by protein structure

Computational protein design techniques (described in Methods) were used to generate an exhaustive list of low-energy sequences for three small proteins: the Pin1 WW domain (WW-domain), bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI), and an immunoglobulin G-binding domain from streptococcal protein G (B-domain), whose crystal structures are shown in Figure 1A (45–48). The 3,000 lowest energy sequences computed to be stable for each of the three protein backbones were considered an estimate of the set of allowed (or “foldable”) sequences for that structure. We then tested the ability of different sequence-space search procedures to find the most diverse sets of these sequences. These sequences were transformed into sequence-space graphs, providing a graphical depiction of the allowed sequence spaces, shown in Figure 1B. Each node in this type of graph represents a protein sequence. An edge between two nodes indicates that a single DNA mutation will interconvert encodings for the two proteins corresponding to those nodes. Surface positions were excluded from the calculations to focus attention on interrelated buried positions most critical for stability.

Figure 1.

(A) Crystal structures of the bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor (BPTI), pin1 WW domain (WW), and an immunoglobulin G binding domain from streptococcal protein G (B-domain) (PDB codes 1BPI, 1F8A, and 1IGD at 1.09, 1.84, and 1.10 Å resolution, respectively (45–48)). Core residues allowed to mutate are colored blue. (B) Sequence-space graphs for BPTI, WW, and B-domain with the five largest components colored in red, orange, yellow, green, and blue, in decreasing size order. The remaining vertices are colored purple. Component sizes are given in Table 2.

The structural constraints of each protein fold influence the type of sequences allowed for its core and therefore the topology of its sequence-space graph. Graph properties such as component sizes, degree distributions, and clustering coefficients can help to characterize the sequence space through which evolutionary routes are taken. Multiple, separated components exist in each sequence-space graph, as shown in Figure 1B and quantified in Tables 1 and 2. This means that single DNA mutations can explore within a component, but that multiple, simultaneous mutations are necessary to cross between components. The sizes of these separated sequence-space graph components differ from one to 2,854, indicating a very wide range. In the B-domain sequence-space graph, nearly all the protein sequences computed to be foldable are part of one giant component, indicating that only single DNA mutations are required to move throughout almost the entire sequence space. The BPTI and WW-domain sequence-space graphs are more fractured, and single DNA mutations would only allow mutation within smaller subsets of these graphs.

Table 1.

Properties of the sequence-space graphs in Figure 1B. A component is a set of connected nodes, and the size of a component is the number of nodes in that connected set. The degree of a node is the number of neighbors it has, or the number of links touching that node. The clustering coefficient describes local topology: the fraction of each node’s neighbors that are neighbors of each other. The shortest path is calculated between every pair of nodes that are connected to each other in the network. The maximum of these shortest paths is defined as the graph diameter. The average of these path lengths is also recorded.

| WW | BPTI | B-domain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Num components | 144 | 320 | 39 |

| avg component size | 20.76 | 9.29 | 76.82 |

| largest component size | 613 | 1251 | 2854 |

| avg degree | 4.18 | 3.28 | 5.64 |

| avg clustering coeff | 0.094 | 0.064 | 0.087 |

| avg shortest paths | 8.94 | 9.69 | 10.52 |

| diameter | 32 | 26 | 31 |

Table 2.

Sizes of the graph components in Figure 1B. The largest five sequence-space graph components are colored red, orange, yellow, green, and blue in descending order, and the remaining vertices that are not part of the largest five components are colored purple.

| BPTI | WW | B-domain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| red | 1251 | 613 | 2854 |

| orange | 158 | 492 | 44 |

| yellow | 102 | 437 | 19 |

| green | 94 | 205 | 12 |

| blue | 92 | 149 | 7 |

| purple | 1303 | 1214 | 64 |

Sequence-space graph nodes are well-connected but with a variable number of neighbors, making evolution between foldable protein sequences efficient but non-uniform

Within each sequence-space graph component, each protein sequence is connected to on average 3.3 to 5.6 other protein sequences by single DNA mutations. This node degree is the number of sequences computed to be foldable that are within one DNA mutation of that sequence. In the full space of all possible protein sequences, with no requirement for fold stability, the average node degree would be between 66 and 119 because each amino acid can reach on average 6 to 7 other protein sequences with a single DNA mutation, and our cores varied in size from 11 to 17 residues. The low observed degree in our graphs indicates that the vast majority of single non-silent DNA mutations away from each native core protein sequence would not yield a protein sequence computed to be foldable.

However, the observed node degrees in our sequence-space graphs are large compared to the expected node degree of zero when 3,000 random sequences of 11 to 17 residues are chosen. This points to the uneven distribution of our foldable sequences in sequence space caused by the selected backbone structures, which result in a relatively small number of residues at each position occurring with each other in various combinations. Moreover, because the residues allowed at individual positions are often of similar character, they are interconvertible with a single base-pair change due to the genetic code. We quantify this bias by computing a “density” of sequences in a region of the search space. The fraction of sequence space expected to fold to a specific structure is tiny. For example, studies of hydrophobic/polar patterned lattice models indicate that approximately 10−9 of the possible sequences for a protein of 100 residues will fold to the same structure (49). If these sequences were spread evenly throughout the search space, multiple mutations would be required to move between every pair of sequences. We created sets of 3,000 random sequences of length 11, 12, and 17 to compare to the B-domain, WW-domain, and BPTI sequence spaces. In each case, we define the “allowed region” of the sequence space occupied by that set of sequences as the product over all positions of the number of amino acids allowed at that position. The sequence density in this region of sequence space is then 3,000 divided by the size of the allowed region. The size of the allowed region is 3.0 × 1011, 4.3 × 109, and 3.1 × 109 for BPTI, WW-domain, and B-domain respectively. In contrast, for the sets of random sequences the allowed regions are of size 1.3 × 1022, 4.1 × 1015, and 2.0 × 1014 for sequences of length 17, 12, and 11, respectively. Therefore, our 3,000 sequences computed to be foldable are clustered together in a small region of the sequence space with a density 105 to 1010 times greater than that for random sequences. This uneven distribution of sequences in the sequence space caused by the selected backbone structure makes evolution between these sequences efficient even though the total number of foldable sequences is still quite low. Indeed, experimental studies where mutations are made between similar amino acids show the foldable sequences to be very dense in a narrow region of sequence space (50, 51).

The node degrees in our sequence-space graphs are variable, as shown in Figure 2. Single DNA mutations from protein sequences with many neighbors (called “hubs”) yield more sequences computed to be foldable than they do from others. There are more of these hub nodes than one would expect from a random graph with the same number of nodes and edges. Therefore, these graphs have a hub-like property similar to that found in other biological networks, but they do not satisfy the formal definition of scale-free..

Figure 2.

Degree distributions for the sequence space graphs shown in Figure 1B. The degree of a node is the number of edges touching that node in its sequence-space graph.

Error-prone PCR Simulation

The number of rounds of error-prone PCR and the screening limit influence search success more strongly than does the mutation rate

We performed computational simulations of evolutionary experiments. The essential idea is that multiple rounds of a protocol to introduce sequence variation were applied to a random starting sequence. The sequences need not correspond to allowed foldable sequences but in this work the starting sequence was always one of those computed to be foldable. A set of rounds of sequence variation was then followed by selection. Only functional sequences pass the selection, and foldability is a prerequisite for functionality in this model. In an initial set of computations, we simulated 9, 12, 15, and 18 rounds of error-prone PCR without selection and studied the resulting sequence distributions as a function of the mutation probability. The resulting protein sequence distributions were characterized by the number of mutations in the final population, the number of unique foldable sequences in the final population, and by counting the number of functional sequences (selected randomly as described in the methods) in the final population. Here, sets of 30, 300, and 1000 sequences were considered functional; thus, the fraction of functional sequences ranged from 1/100 to 1/3 of the foldable space. This procedure is different from those where selection or screening for partial function is used at each step along a path to full function. We consider that function may require a set of concerted changes and so we select for function from the entire sequence space accessible by our error-prone PCR simulations.

The distribution of the number of DNA sequences at the end of 9, 12, 15, and 18 rounds of error-prone PCR approximately follow Poisson distributions, as described in Methods. The expected number of mutations per sequence is proportional to the mutation probability and the number of rounds of error-prone PCR, where the mutation probability (or mutation rate) is defined as the probability of mutation of each DNA base-pair per generation. As shown in Figure 3, diffusion away from the wild-type sequence increased with both increasing mutation rate and increasing rounds of error-prone PCR.

Figure 3.

Histograms of the number of amino-acid mutations per sequence, after 9, 12, 15, or 18 rounds of error-prone PCR at five different DNA mutation probabilities. The mean and standard error bars are shown for simulations on 10,000 starting sequences with 17 amino-acid residues.

Because the node degrees are low compared to what they would be in an exhaustive sequence-space graph, most of these generated sequences leave the graph at some point during their mutation from the starting sequence in our error-prone PCR simulations. We explored the likelihood of this occurring in our 10,000 simulations of 15 rounds of error-prone PCR at a mutation probability of 0.01 per base-pair per generation. The probability of leaving the foldable sequence space at some point during the simulations was 0.94, 0.87, and 0.82 for BPTI, WW-domain, and B-domain, respectively. The probability of ending the simulation within the foldable space having left it at some point during the simulation was 0.002, 0.004, and 0.006 for BPTI, WW-domain, and B-domain, respectively. Therefore, a typical error-prone PCR simulation experiment produced a small fraction of sequences computed to be foldable, and most of those produced remained on the sequence-space graph throughout the simulation.

Using the same simulations of error-prone PCR at varying mutation rates and rounds of replication, we analyzed the impact of a screening limit on the diversity of foldable sequences created. The number of unique, foldable sequences produced increased with the number of rounds of error-prone PCR (Figure 4A). This is because in each round more of the sequence space was explored as more sequences were produced. However, the fraction of foldable sequences in the screening pool decreased drastically with the number of rounds of error-prone PCR (Figure 4B). This is because the number of deleterious mutations increased more rapidly than did the number of allowed mutations. The significance of this observation is underscored by imposing a screening restriction (here of 105 sequences) in Figure 4C. This cutoff eliminated screening of 62% of the sequences after 18 rounds of error-prone PCR, allowing the large fraction of non-folding sequences in the search space to dominate the screening and making 15 rounds of error-prone PCR more effective than 18 rounds. If this cutoff were made at 104 sequences, 12 rounds of error-prone PCR would be preferable and 96% of the sequences from the 18-round experiment would be eliminated. This analysis highlights the tradeoff between increasing diversity and decreasing folding fraction with additional rounds. If the entire pool cannot be screened, the additional rounds may be detrimental. This analysis is based on the effectiveness of search of foldable sequences, and the characteristics of the search for a particular function may not always be the same.

Figure 4.

Variation of the number of unique sequences identified by search as a function of the mutation rate and the number of rounds of error-prone PCR. All simulations started with sequences computed to be foldable for the WW-domain. Error-prone PCR simulations were performed from random single starting sequences computed to be foldable, at 5 different mutation rates and for 9, 12, 15, and 18 rounds of error-prone PCR. All results are mean per trial over 10,000 trials. (A) The number of unique protein sequences generated. (B) The fraction of unique protein sequences within the total number of sequences generated. (Peaks still exist in these curves at a mutation rate of 0.01 but are not visible due to the log scale.) (C) The number of unique protein sequences seen after a screening limit of 105 sequences is imposed.

Figure 4 also highlights that the number of rounds of error-prone PCR has more impact on the number of unique foldable sequences generated than does the mutation probability. A two-fold change in the mutation probability yielded a change of no more than 1.17-fold in the number of unique foldable sequences produced and a ten-fold change in the mutation probability yielded a change of no more than 2.5-fold in the number of unique foldable sequences produced. However, a two-fold change in the number of rounds of error-prone PCR caused up to a 7-fold change in the number of unique foldable sequences produced. This is interesting because the distribution of mutations per sequence is influenced equally by both the mutation probability and the number of rounds of error-prone PCR (Figure 3). However, as the mutation rate increases, the generated mutants are more distant from the starting sequence but the number of sequences created does not increase. At a certain number of rounds of error-prone PCR, a lower mutation probability was always more effective at producing more foldable sequences. However, the requirement for unique foldable sequences made more intermediate mutation rates most effective.

Effective library diversity depends on graph topology and the location of the starting sequence

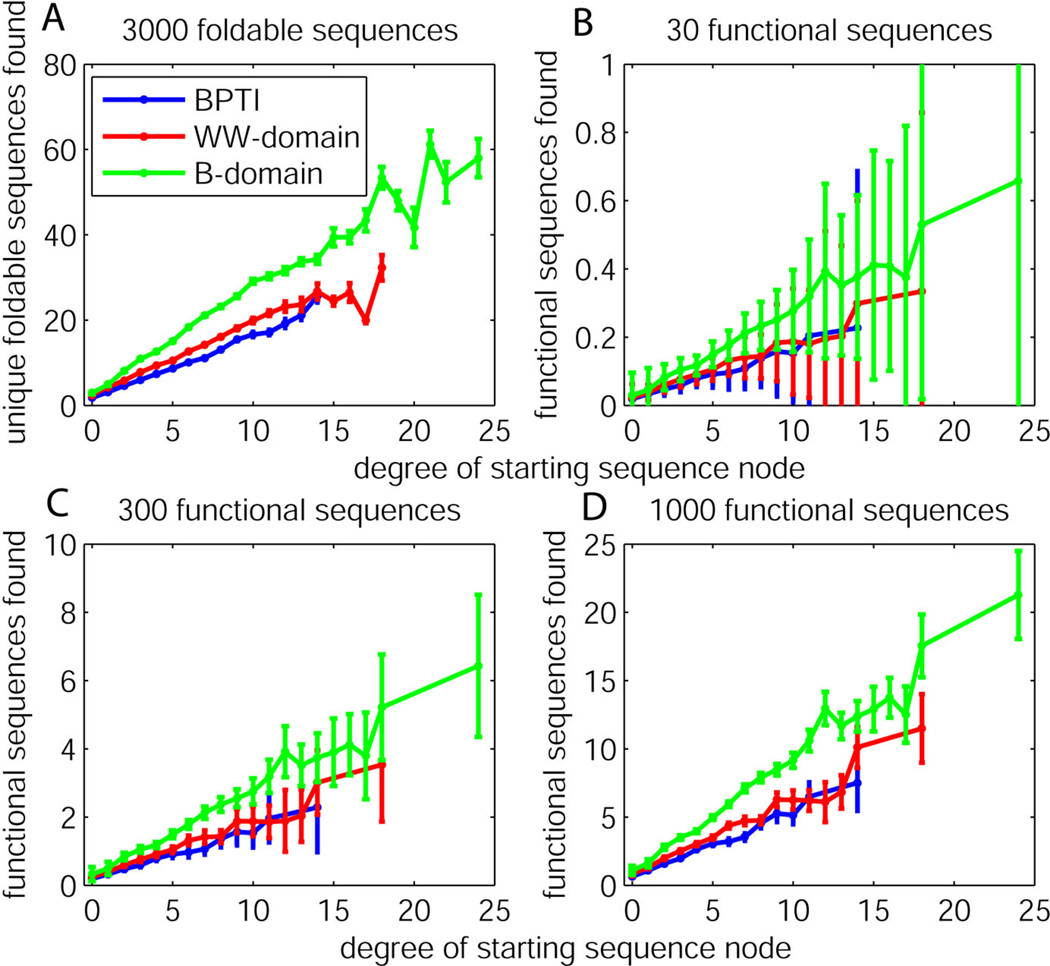

For further error-prone PCR simulations, we held the mutation probability constant at 0.01 per base-pair per generation and the number of rounds of error-prone PCR constant at 15. We then asked how the effective library diversity varied with the local topology of each sequence in our sequence-space graphs. Our measure of diversity is the number of unique foldable sequences generated during the error-prone PCR simulation. In each error-prone PCR simulation, one foldable protein sequence was chosen at random, and a random DNA sequence encoding that protein sequence was chosen as a starting point for error-prone PCR. After fifteen rounds of simulated error-prone PCR, foldable and functional sequences were selected. Averages of these results over 10,000 randomly chosen starting sequences are described.

Figure 5A shows the number of unique foldable protein sequences created after 15 rounds of error-prone PCR, plotted separately by the degree of the starting node. Error-prone PCR simulations that started from nodes with a small degree typically resulted in low-effective diversity sequence libraries, whereas simulations started from nodes with larger degrees typically resulted in higher-effective diversity libraries. This is because simulations from larger degree nodes were more likely to remain on the sequence-space graph throughout the simulation, with that probability increasing by 0.012 per degree on average. To put this number in context, the overall probability of staying on the graph was 0.06, 0.13, and 0.18 for BPTI, WW-domain, and B-domain. Therefore, starting from a node with a degree about 10 larger than an average node should approximately double the probability of staying on the sequence-space graph, compared to the average. Simulations from larger degree nodes were also slightly more likely to return to the graph after having left it at some point in their simulation, with that probability increasing by 0.0001 per degree. In Figures 5B–D the results of the same trials are plotted again by the degree of the starting sequence, where at the end of 15 rounds of error-prone PCR only functional sequences were selected, and where 30, 300, or 1000 functional sequences were randomly pre-selected from the 3,000 sequences computed to be foldable. The averaged results show the trend that locating more foldable sequences does yield more functional ones. The standard error for these results was small, ranging from 0.001 to 0.079 functional sequences found, meaning that the average is well established. Nevertheless, the standard deviation bars plotted for these results show very large variance when function is rare in the sequence space. The implication of these results is that any particular set of evolutionary experiments may produce results far from the average when function is rare, and that exhaustive work may be necessary to experimentally determine average behavior to compare methodologies.

Figure 5.

(A) The number of unique protein sequences generated after 15 rounds of error-prone PCR simulation with the results recorded separately by the degree of the starting sequence in its sequence-space graph. Standard error bars over 10,000 trials are shown. (B–D) The number of functional protein sequences generated after 15 rounds of error-prone PCR simulation. The fraction of the foldable sequence space that is functional is approximately 0.01, 0.1, and 0.3 for plots B, C, and D, respectively. The results are recorded separately by the degree of the starting sequence in its sequence-space graph, and standard deviation bars over 1000 random selections of functional sequences over 10,000 error-prone PCR trials are shown.

These results highlight the principle that the local graph topology surrounding the starting sequence can be a significant influence on the effectiveness of protein evolution experiments. The degree of a node is influenced both by the number of similar sequences that are also computed to be foldable and by the codon bias of the genetic code. For example, neither negatively-charged amino acid (D or E) can be reached from the amino acids F, L, I, M, S, P, T, C, W, or R by a single DNA mutation, regardless of which codons are used to specify them. Neither positively-charged amino acid (R or K) can be reached from the amino acids N, F, V, or A. A goal protein function requiring multiple mutations could be found by successive single mutations, but excessive library sizes might be required to ensure a high probability of creating such a mutant.

It has been suggested that increasing a protein's stability may also increase its evolvability because preliminary stabilizing mutations may allow more potentially destabilizing mutations that improve function (52). This principle has been used successfully to design a family of cytochrome P450 enzymes (44). To explore this concept further, we asked whether the computed stability of our protein sequences correlated with the size of the foldable sequence space available. We compared pairs of sequences from our sequence-space graphs where the sequences were identical except for a mutation at a particular position i. For example, one sequence might have an alanine at that position and another might have a valine. We then asked whether the lower-energy sequence from this pair was more or less evolvable at the remaining positions. The number of sequences in the sequence-space graph where position i is constrained (to alanine, for example) is the evolvability of that sequence in the pair. For every core position in BPTI, WW-domain, and B-domain we counted the number of sequence pairs where the lower-energy sequence was more evolvable and the number of pairs where the higher-energy sequence was more evolvable. As shown in Figure 6, more frequently the lower-energy sequence was more evolvable (at 23 of 38 positions), although this is a weak trend. The positions where the lower-energy sequence was more evolvable were more often the less-buried positions in the protein structures, but this also was not a requirement for the result. These findings are consistent with a picture in which a stabilizing mutation that is uncoupled (or only poorly coupled) to functionally important residues is likely to enlarge the feasible space (53, 54), but a stabilizing mutation that strongly interacts with functionally important residues may have more varied effects.

Figure 6.

Evolvability of sequence pairs with one mutation and different energies. (A) For pairs of sequences with a mutation at only one position, we asked whether the sequence with the lower or higher computed energy was more evolvable. This evolvability is defined as the number of sequences remaining in the sequence-space graph when the variable position in the pair is constrained. This was done for all pairs of sequences found in the sequence-space graphs that had only a single mutation between them, and the results are separated by each core position in order by the residue number in the structure. (B) In BPTI the core positions are 4, 6, 10, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 33, 35, 36, 43, 44, 45, and 47. (C) In WW-domain the core positions are 9, 11, 15, 17, 20, 23, 27, 28, 29, 36, 37, and 38. (D) In B-domain the core positions are 8, 10, 12, 14, 31, 35, 39, 44, 48, 57, and 59.

Genetic Recombination Simulation

Genetic recombination can make multiple mutations and the efficiency of this process depends on the identity between the starting sequences

Making multiple mutations from a starting sequence may be important for evolutionary protein engineering projects when more drastic functional changes are desired. Indeed, multiple mutations have even been shown to be required for new function in some cases, where subsets of the functional mutations were shown to be nonfunctional (39, 55, 56). Each genetic recombination experiment started with two or three parent sequences randomly chosen from our sequence-space graph, and two or six new sequences were created in each recombination event. These new sequences could each be a new foldable protein sequence, a copy of a parent sequence, or a protein sequence not computed to be foldable. We ran 10,000 trials of genetic recombination in each sequence-space graph. Figure 7 depicts the distribution of amino acid mutations away from the starting sequence for both the error-prone PCR and genetic recombination experiments. A larger fraction of unique foldable multiple mutants was created by genetic recombination than by error-prone PCR, and the distribution of mutations away from the starting sequences illustrates that achieving three or more mutations in one trial was more likely in the genetic recombination simulations. Because of the similarity between the sequences computed to be foldable (the mean of the pairwise amino acid distances between foldable sequences is 6.3 with variance 3.5) there is relatively limited diversity among sequences selected for recombination. With larger sets of positions varied and greater variability among them it is likely that larger gains could be seen for genetic recombination.

Figure 7.

The distribution of unique foldable sequences found in each evolutionary simulation as a function of the number of mutations from the starting sequence. (A) Fraction of unique foldable sequences found in each simulation of 15 rounds of error-prone PCR with a mutation probability of 0.01 per base-pair per generation. Each simulation started with one sequence and after each trial the distance of each unique foldable resulting sequence to this one sequence was computed. (B) Fraction of unique foldable sequences found in each genetic recombination simulation started with 2 randomly-chosen foldable sequences. These sequences were cut once and recombined to produce 2 sequences. For each of the two resulting sequences, the minimum distance from each resulting sequence to a starting sequence was computed. (C) Fraction of unique foldable sequences found in each genetic recombination simulation started with 3 randomly chosen foldable sequences. These sequences were cut twice at random and recombined such that 6 sequences were produced. These 6 sequences contained all possible combinations of the three starting sequences such that some fragment from each starting sequence was part of each resulting sequence. The minimum distance from each resulting sequence to the closest starting sequence was computed.

Figure 8A depicts the relationship between the relative similarity of recombined sequences and the success of generating a new foldable sequence. These results point to a region of optimal DNA distance between the starting sequences for recombination where new, foldable sequences were most likely to be generated by a recombination event. When the two parent sequences were very similar to one another, recombining them most frequently resulted in one or two copies of the parent sequences; when the two parent sequences were very different from one another, recombination most often produced one or two sequences not computed to be foldable. We repeated these simulations with a different recombination procedure, starting with three randomly-chosen foldable sequences which were recombined around two points to produce six sequences containing fragments from all three starting sequences in all combinations. The results from these simulations were very similar and point to a nearly idential optimal region of DNA distances between the parent sequences (between 0.14 and 1.29 bases per residue for WW-domain).

Figure 8.

Genetic recombination results at each distance between parent sequences. Each genetic recombination trial starts with two parent sequences computed to be foldable and sequences were cut once at a random location and recombined. The number of sequences seen per trial were plotted at each DNA distance per residue between the parent sequences. Standard error bars over 10,000 trials are shown. (A) Only sequences that were computed to be foldable and were different from either parent sequence are included. (B) Only sequences that were computed to be foldable, were different from either parent sequence, and were in a different graph component from that of either parent sequence are included.

Figure 8B shows the fraction of sequences generated by each recombination event that were both computed to be foldable and were located in a separate component of the sequence-space graph from that of either parent. These results were again separated by the DNA distance between the parent sequences, indicating that a larger sequence difference was necessary to hop to a separate component of sequence space. A new sequence in a new sequence-space graph component was generated with probability 0.05, 0.04, and 0.002 in the BPTI, WW-domain, and B-domain sequence spaces, respectively. Genetic recombination appears to be an excellent method for making large jumps in sequence space with direction toward the portions of sequence-space computed to be foldable. Choosing an optimal DNA distance between the starting sequences could further improve the success of this technique.

Discussion and Conclusion

Here we have applied protein structural modeling to estimate the space of foldable sequences and carried out simulations of accelerated evolution in the entire sequence space to understand better this important technology. Fundamental to the analysis is the concept that stable folded structure is a prerequisite for function; this is usually but not always the case for natural proteins. The results indicate that the foldable sequences are non-uniformly distributed in sequence space, with a sequence density in the allowed region 105 to 1010 times greater than that for random sequences of the same length. Nevertheless, the sets of foldable sequences are sparsely distributed, such that many point mutations lead to non-foldable sequences. A relatively small number of sequences exist as hubs such that they are connected to a relatively large number of foldable neighbors via point mutations. These hubs were found to be especially productive starting points for error-prone PCR simulated evolutionary experiments. Evolutionary simulations also indicate that once a sequence leaves the set of foldable sequences, it is very rare for its descendents to re-enter the foldable space.

The simulations demonstrate a tradeoff between diversity and screening (or selection) capacity. Increases to the mutation rate do not increase the diversity of foldable sequences as effectively as corresponding increases in the number of rounds of error-prone PCR. This is due partially to the observation that greater mutation rate leads to increased probability of leaving the set of foldable sequences (which is generally irreversible); moreover, simulations with greater mutation rate tend to more sparsely sample the space of mutant sequences as compared to simulations with a lower mutation rate and correspondingly more rounds of error-prone PCR. However, the exponential increase in the number of sequences with more rounds of error-prone PCR decreases the fraction of unique foldable sequences. That is, a greater number of unique foldable sequences results from long evolution; a greater fraction can be obtained with shorter evolution. Thus, experiments that can access the full number of unique foldables by screening or selecting the entire “culture” should use long evolution; but with a smaller screening capacity, one can only access the fraction foldable, and so shorter evolution may be preferable. A hybrid strategy may be particularly effective, in which evolution is carried out up to the screening capacity, non-foldables are eliminated (because they are unlikely to evolve into foldables), and evolution is continued on to the remainder up to the screening capacity. This would produce the diverse foldable sequence library associated with longer continuous evolution schemes without the corresponding increase in selection or screening capacity that would otherwise be necessary. The genetic recombination simulations demonstrated that recombination efficiently makes multiple mutations with direction toward the foldable portions of the sequence space and that the sequence identity between the parent sequences influences this outcome. Sequence identities between approximately 10% and 40% produced new foldable sequences with the highest probability for the cases studied here. However, our procedure is biased toward frequent recombination, and so parent sequences with less similarity may also be useful experimentally. The methods presented here largely examine the best approaches for searching the space of foldable sequences, because folding is generally a prerequisite for function.

Because node degree and the location of starting sequences in our sequence-space graphs influenced the results of our evolutionary simulations, protein design calculations such as those described here might be used to generate sequence-space graphs to aid selection of sequences for evolutionary design. However, generating an entire sequence-space graph currently requires tremendous computational resources for proteins much larger than those analyzed here. However, simpler procedures could be used to obtain the relevant information. The number of neighbors (node degree) could be estimated by computationally exploring only the area of the sequence-space graph local to a chosen starting sequence. Such an exploration of all single mutations for a protein is computationally inexpensive compared to exploring the global graph properties, as was done in this study. Locating the well-separated sequences necessary for recombination could also be done using computational design of a small number of sequences. BLAST (57) could also be used to search for new sequences with the desired separation.

Our results provide a complement to previous studies of sequence-space graph topology and evolution for lattice protein models. One widely used metric is protein “designability”, which is the number of sequences compatible with a given protein structure (8). This property has been related to protein mutability (8, 58), and mutational funnels in sequence space have been found that center around a single highly-designable sequence (59). Designability has also been related to thermodynamic stability (8, 58) and the most highly designable sequences are thought to have the fastest folding rates (60).

All-atom protein models have also been used in the past to explore protein designability and evolution. Kuhlman et al. use a Monte Carlo based mutation technique find that the sequence space compatible with a given structure is very close to the native sequence, with 51% identity in the core (61). Koehl et al. perform a random sequence threading procedure and find that the entropy of each position is similar in the design and in nature (9). Larson et al. use a Monte Carlo based mutation procedure along with backbone sampling and find that the diversity of allowed sequence is influenced by the fold but that designed sequences have greater sequence entropy than do natural sequences (62).

From the perspective of protein design, it is relevant to discuss designability not only as the number of sequences allowed for a given structure and how similar these sequences are to the wild-type but also in terms of the accessibility of these sequences by different protein engineering techniques. This work explores this aspect of designability by exploring evolution on a sequence space created by an all-atom protein design technique. Lists of real foldable and functional sequences (and non-foldable and non-functional sequences) for a real protein and goal function would be useful for validating the conclusions presented in this article. Lacking such data, we have generated allowed protein sequences computationally, and used multiple techniques to do so in order to reduce the influence of computational error in our conclusions. However, due to approximations in the search algorithm, these lists are lower bounds on the true sequences allowed for each protein; the rigid backbone and the discrete rotamer library used during the sequence and structure search disallow some sequences that would be able to fold similarly to the wild-type sequence. Although some sequences are missing from our foldable sequence spaces, the sequences chosen are expected to be stable on their respective backbone structures.

This work provides a framework for thinking about evolutionary protein engineering and provides a general methodology for exploring foldable protein sequences with simulations of experimental sequence-space search techniques. Ultimately one cares directly about function, and particularly if the distribution of functional sequences is strongly non-uniform across the space of foldable sequences, adopting procedures that optimize search of the functional space directly are best. In the absence of specific knowledge about the distribution of functional sequences, adopting procedures that optimize search of the foldable space may be the best approach.

Methods

Evolution simulations

Evolution simulations were performed using our own code in the C++ programming language. Multiple rounds of error-prone PCR were simulated from one starting DNA sequence in each trial. We ran 10,000 trials of each error-prone PCR experiment from randomly-chosen starting sequences to generate good estimates of the reported statistics for each combination of parameters. The mutation rate (the probability of mutating each DNA base to any of the four bases in each round of error-prone PCR) was varied from 0.001 to 0.05 per base-pair per generation in Figure 3 and from 0.001 to 0.02 per base-pair per generation in Figure 4, and this probability was fixed at 0.01 per base-pair per generation in all subsequent trials. The number of rounds of error-prone PCR was 9, 12, 15, or 18 in Figures 3 and 4 and was fixed to 15 in all subsequent trials. The starting DNA sequence coding for a given protein sequence was chosen at random when multiple codons were allowed. In genetic recombination simulations, the two or three starting parent sequences were chosen at random from the list of allowed sequences, one or two cut positions between amino acid residues were chosen at random, and the sequences were recombined around these points. The order of the cut fragments was maintained during the recombination. The random() function in C++ was used for random number generation, with varying random number seeds.

We focused on the number of unique allowed protein sequences seen in the last round of error-prone PCR as the output of each simulation. This was highlighted over other possible metrics (such as the maximum number of mutations found or the total number of allowed sequences found) because creating the largest number of different foldable sequences (or the most diverse possible foldable library) should allow the greatest chance of locating functional sequences during subsequent library screening or selection.

In our simulations of error-prone PCR and genetic recombination, we sought to capture the most fundamental characteristics of these experiments. In error-prone PCR experiments, the mutation probability and the sequence replication process at the DNA level were the fundamental elements of the process captured in our model. It is important to note that the sequences subjected to error-prone PCR represent the protein cores only, and we assume that mutation will also occur at surface positions but that surface mutations will not affect protein stability, which is an approximation. We did not consider the DNA base mutation bias that differs between organisms because experimentalists can counter this effect for the most part by adding the appropriate dNTP's to bias the experiment toward the ideal in our model: an equal mutation probability between all DNA bases (31). In our genetic recombination experiments, the process of cutting the parent sequences at a random position and recombining them to yield variable new sequences were the fundamental processes that we modeled. For example, one of the first techniques of this type cut four parents sequences into random fragments of 10–50 base-pairs each (63). Different experimental procedures for performing recombination contain different biases (for example, on where these cuts occur), but experimental genetic recombination procedures have been getting closer to the ideal in our model: all possible cut locations between codons are equally likely, where the probability of obtaining an allowed sequence is increased because codon boundaries are respected and the gene length and fragment positions remain constant.

In our analysis of the distribution of mutations in error-prone PCR simulations shown in Figure 3, we found that the distributions fit well to Poisson distributions where the expected number of mutations per sequence (at the low mutation rate limit) is the mutation probability times the number of rounds of error-prone PCR times the number of DNA bases in the sequence, divided by two. Because the probability of a DNA mutation being non-silent is 0.760417, the distribution of amino acid mutations at the end of each simulation is also approximately Poisson. Again at the low mutation rate limit, the expected number of amino acid mutations per sequence is the DNA mutation probability times 0.760417 times the number of rounds of error-prone PCR times the number of DNA bases in the sequence, divided by two. In this Poisson analysis, stop codons are considered to code for a “stop” amino acid, which always creates a non-folding sequence in our model.

Sequence-space graph generation

Crystal structures for WW-domain, BPTI, and B-domain were from the Protein Data Bank (PDB codes 1BPI, 1F8A, and 1IGD at 1.09, 1.84, and 1.10 Å resolution, respectively (45–48)). Computational protein sequence and structure search methods were used to determine the allowed sequences for each protein core. These proteins were chosen because they are small but have well-packed cores, making our computational sequence and structure search feasible. The steric constraints in the core restrict the available sequence space, making the allowed sequence spaces small enough to be efficiently searched. Because a wide variety of amino acids would be allowed at surface positions due to reduced steric constraints, we performed our search on the core residues only. These cores were composed of 12, 17, and 11 positions for WW-domain, BPTI and B-domain, respectively (see caption to Figure 6), meaning that full sequence spaces of size 2012, 2017, and 2011 were considered. To obtain upper and lower bounds on the possible steric constraints on these core residues, we followed two different procedures for handling the surface residues. In the first procedure, we cut all the surface residues back to alanine to reduce their steric impact as much as possible. In the second procedure, the surface residues were untouched during the design and remained in their crystal structure conformations. The results from both procedures were sufficiently similar that only those from the first procedure are shown.

These sequence spaces were searched using the dead-end elimination and A* algorithms (64, 65), where the pairwise energy function was the sum of van der Waals, solvent-accessible surface area (66), and a Coulombic elecstrostatic term with a dielectric constant of 4 times the distance between each pair of atoms. Each protein backbone remained rigid during the search, and only the rotamers of each amino acid were considered during the search, using a backbone-independent rotamer library (67–69). The lowest-energy 2,999 sequences for the WW-domain, BPTI, and B-domain cores were recorded and were used to define the allowed sequence space for each protein. The calculated energies for this list of sequences spanned 10, 12, and 55 kcal/mol for WW-domain, BPTI, and B-domain, respectively. The wild-type sequence was added to the list to create a set of 3,000 allowed sequences.

We also created a definition of a “functional” sequence to probe how this additional type of restriction influenced our results. We selected random sets of 30, 300, or 1,000 sequences from our lists of 3,000 allowed sequences to test the ability of our error-prone PCR and genetic recombination simulations to locate these functional subsets of sequence space. These definitions mean that the fraction of the foldable space that was functional was 1/100, 1/10, or 1/3. We chose not to use low-energy as a selection for function because natural proteins are not the most stable proteins for their backbone folds (70).

Sequence-space graphs were created by associating a graph node with each protein sequence computed to be foldable. For every pair of proteins, the mutation distance between them was defined as the smallest number of DNA-base mutations required to mutate from one protein sequence to the other, if any set of codons could be chosen for those protein sequences. If the mutation distance was one, then an edge was drawn between the nodes corresponding to those two proteins. These graphs were used for sequence selection only and were ignored during the evolution simulations, so the approximations here did not influence those results. Java 1.4.2 was used for all graph creation, and the JUNG (Java Universal Network/Graph) Framework was used (71). Note that if 25 surface positions were mutated to alanine, and we selected 3,000 sequences for the core, then if truly any amino acids were allowed at the surface, the “true” sequence-space graph for that protein would have 3000 × 2025 nodes. However, this graph would have 2025 identical sub-graphs of size 3,000 (representing the core residues) with edges between them representing mutations of the surface residues. Therefore, we represent the allowed sequence space as the graph of the sequences available to the core only.

Measurement of graph properties

A component in a graph is a set of nodes where some path of edges connects every pair of nodes. The size of a component in a graph is the number of nodes that are connected in this way. When no edges connect two components in the graph, those components are called separated or disconnected. The degree of a node is the number of edges that touch that node. A node's clustering coefficient describes the connectivity of that node's neighbors and is defined as the fraction of the possible edges between those neighbors that exist. The shortest path between two nodes in a graph is the number of edges along the shortest connected path of edges between two nodes. The average of the shortest paths is computed after calculating the length of the shortest path between every pair of nodes. Shortest paths and component sizes were calculated using the breadth-first search algorithm (72). The shortest path between a node and itself is defined to be zero. The diameter is the length of the longest shortest path in the graph.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Daša Lipovšek, Mark J. Nelson, and K. Dane Wittrup for helpful discussions. This work was partially supported by the DuPont–MIT Alliance and by an NIH Biotechnology Training Grant.

References

- 1.Bloom JD, Meyer MM, Meinhold P, Otey CR, MacMillan D, Arnold FH. Evolving strategies for enzyme engineering. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005;15:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reetz MT. Controlling the enantioselectivity of enzymes by directed evolution: Practical and theoretical ramifications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:5716–5722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306866101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin AM, Weiss GA. Optimizing the affinity and specificity of proteins with molecular display. Mol. Biosyst. 2006;2:49–57. doi: 10.1039/b511782h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker D. Prediction and design of macromolecular structures and interactions. Philos. T. Roy. Soc. B. 2006;361:459–463. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butterfoss GL, Kuhlman B. Computer-based design of novel protein structures. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2006;35:49–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vizcarra CL, Mayo SL. Electrostatics in computational protein design. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005;9:622–626. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dwyer MA, Looger LL, Hellinga HW. Computational design of a biologically active enzyme. Science. 2004;304:1967–1971. doi: 10.1126/science.1098432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H, Helling R, Tang C, Wingreen N. Emergence of preferred structures in a simple model of protein folding. Science. 1996;273:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koehl P, Levitt M. Protein topology and stability define the space of allowed sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:1280–1285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032405199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogarad LD, Deem MW. A hierarchical approach to protein molecular evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:2591–2595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore GL, Maranas CD. Modeling DNA mutation and recombination for directed evolution experiments. J. Theor. Biol. 2000;205:483–503. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maheshri N, Schaffer DV. Computational and experimental analysis of DNA shuffling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:3071–3076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537968100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen M, Iverson B, Georgiou G. High-throughput screening of enzyme libraries. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000;11:331–337. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amstutz P, Forrer P, Zahnd C, Pluckthun A. In vitro display for technologies: novel developments and applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2001;12:400–405. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boder ET, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for directed evolution of protein expression, affinity, and stability. Methods Enzymol. 2000;328:430–444. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)28410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daugherty PS, Chen G, Olsen MJ, Iverson BL, Georgiou G. Antibody affinity maturation using bacterial surface display. Protein Eng. 1998;11:825–832. doi: 10.1093/protein/11.9.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samuelson P, Gunneriusson E, Nygren P, Stahl S. Display of proteins on bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 2002;96:129–154. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(02)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith GP, Petrenko VA. Phage display. Chem. Rev. 1997;97(2):391–410. doi: 10.1021/cr960065d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seed B. Purification of genomic sequences from bacteriophage libraries by recombination and selection in vivo. Nuc. Acids. Res. 1983;11:2427–2445. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.8.2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts RW, Szostak JW. RNA-peptide fusions for the in vitro selection of peptides and proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:12297–12302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanes J, Pluckthun A. In vitro selection and evolution of functional proteins by using ribosome display. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:4937–4942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tawfik DS, Griffiths AD. Man-made cell-like compartments for molecular evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:652–656. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stemmer WP. Rapid evolution of a protein in vitro by DNA shuffling. Nature. 1994;370:389–391. doi: 10.1038/370389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes RJ, Bentzien J, Ary ML, Hwang MY, Jacinto JM, Vielmetter J, Kundu A, Dahiyat BI. Combining computational and experimental screening for rapid optimization of protein properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:15926–15931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212627499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wahler D, Reymond J. Novel methods for biocatalyst screening. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:152–158. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bevis BJ, Glick BS. Rapidly maturing variants of the discosoma red fluorescent protein (DsRed) Nature Biotechnol. 2002;20:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Voigt CA, Mayo SL, Arnold FH, Wang Z. Computationally focusing the directed evolution of proteins. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl. 2001;37:58–63. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao H, Arnold FH. Directed evolution converts subtilisin E into a functional equicalent of thermitase. Prot. Eng. 1999;12:47–53. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnold FH. Design by directed evolution. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neylon C. Chemical and biochemical strategies for the randomization of protein encoding DNA sequences: library construction methods for directed evolution. Nuc. Acids Res. 2004;32:1448–1459. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daugherty PS, Chen G, Iverson BL, Georgiou G. Quantitative analysis of the effect of the mutation frequency on the affinity maturation of single chain Fv antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:2029–2034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030527597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaccolo M, Gherardi E. The effect of high-frequency random mutagenesis on in vitro protein evolution: A study on TEM-1 beta-lactamase. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:775–783. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coco WM, Levinson WE, Crist MJ, Hektor HJ, Darzins A, Pienkos PT, Squires CH, Monticello DJ. DNA shuffling method for generating highly recombined genes and evolved enzymes. Nature Biotechnol. 2001;19:354–359. doi: 10.1038/86744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao HM, Giver L, Shao ZX, Affholter JA, Arnold FH. Molecular evolution by staggered extension process (StEP) in vitro recombination. Nature Biotechnol. 1998;16:258–261. doi: 10.1038/nbt0398-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowe LA, Geddie ML, Alexander OB, Matsumura I. A comparison of directed evolution approaches using the α-Glucuronidase model system. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;332:851–860. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00972-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ostermeier M, Shim JH, Benkovic SJ. A combinatorial approach to hybrid enzymes independent of DNA homology. Nature Biotechnol. 1999;17:1205–1209. doi: 10.1038/70754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zha DX, Eipper A, Reetz MT. Assembly of designed oligonucleotides as an efficient method for gene recombination: A new tool in directed evolution. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:34–39. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200390011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mena MA, Treynor TP, Mayo SL, Daugherty PS. Blue fluorescent proteins with enhanced brightness and photostability from a structurally targeted library. Nature Biotechnol. 2006;24:1569–1571. doi: 10.1038/nbt1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silberg JJ, Endelman JB, Arnold FH. SCHEMA-guided protein recombination. Methods Enzymol. 2004;388:35–42. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)88004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saraf MC, Horswill AR, Benkovic SJ, Maranas CD. FamClash: a method for ranking the activity of engineered enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:4142–4147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400065101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voigt CA, Mayo SL, Arnold FH, Wang Z. Computational method to reduce the search space for directed protein evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:3778–3783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051614498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saraf MC, Moore GL, Goodey NM, Cao VY, Benkovic SJ, Maranas CD. IPRO: an iterative computational protein library redesign and optimization procedure. Biophys J. 2006;90:4167–4180. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.079277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bloom JD, Labthavikul ST, Otey CR, Arnold FH. Protein stability promotes evolvability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:5869–5874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510098103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parkin S, Rupp B, Hope H. The structure of bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor at 125K: Definition of carboxyl-terminal residues Gly57 and Ala58. Acta. Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 1996;52:18–29. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995008675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verdecia MA, Bowman ME, Lu KP, Hunter T, Noel JP. Structural basis for the phosphoserine-proline recognition by group IV WW domains. Nature Struct. Biol. 2000;7:639–643. doi: 10.1038/77929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Derrick JP, Wigley DB. The third IgG-binding domain from streptococcal protein G: An analysis by x-ray crystallography of the structure alone and in complex with FAB. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;243:906–918. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nuc. Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lau KF, Dill KA. Theory for protein mutability and biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:638–642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim WA, Sauer RT. Alternative packing arrangements in the hydrophobic core of l repressor. Nature. 1989;339:31–36. doi: 10.1038/339031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamtekar S, Schiffer JM, Xiong H, Babik JM, Hecht MH. Protein design by binary patterning of polar and nonpolar amino acids. Science. 1993;262:1680–1685. doi: 10.1126/science.8259512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bloom JD, Wilke CO, Arnold FH, Adami C. Stability and the evolvability of function in a model protein. Biophys. J. 2004;86(5):2758–2764. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74329-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reetz MT, Carballeira JD, Vogel A. Iterative saturation mutagenesis on the basis of B factors as a strategy for increasing protein thermostability. Ang. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7745–7751. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong A, Albright SN, Wolfner MF. Evidence for structural constraint on ovulin, a rapidly evolving Drosophila melanogaster seminal protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:18644–18649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601849103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hill CM, Li WS, Thoden JB, Holden HM, Raushel FM. Enhanced degradation of chemical warfare agents through molecular engineering of the phosphotriesterase active site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8990–8991. doi: 10.1021/ja0358798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Green DF, Dennis AT, Fam PS, Tidor B, Jasanoff A. Rational design of new binding specificity by simultaneous mutagenesis of calmodulin and a target peptide. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12547–12559. doi: 10.1021/bi060857u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nuc. Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Helling R, Li H, Mélin R, Miller J, Wingreen N, Zeng C, Tang C. The designability of protein structures. J. Mol. Graphics Modell. 2001;19:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bornberg-Bauer E, Chan HS. Modeling evolutionary landscapes: Mutational stability, topology, and superfunnels in sequence space. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:10689–10694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xia Y, Levitt M. Funnel-like organization in sequence space determines the distributions of protein stability and folding rate preferred by evolution. Proteins. 2004;55:107–114. doi: 10.1002/prot.10563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuhlman B, Baker D. Native protein sequences are close to optimal for their structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:10383–10388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larson SM, England JL, Desjarlais JR, Pande VS. Thoroughly sampling sequence space: Large-scale protein design of structural ensembles. Protein Science. 2002;11:2804–2813. doi: 10.1110/ps.0203902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stemmer WPC. DNA shuffling by random fragmentation and reassembly: In vitro recombination for molecular evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:10747–10751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desmet J, de Maeyer M, Hazes B, Lasters I. The dead-end elimination theorem and its use in protein side-chain positioning. Nature. 1992;356:539–542. doi: 10.1038/356539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leach AR, Lemon AP. Exploring the conformational space of protein side chains using dead-end elimination and the A* algorithm. Proteins. 1998;33:227–239. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19981101)33:2<227::aid-prot7>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sitkoff D, Sharp KA, Honig B. Accurate calculation of hydration free-energies using macroscopic solvent models. J. Phys Chem. 1994;98:1978–1988. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dunbrack RL, Karplus M. Backbone-dependent rotamer library for proteins – application to side-chain prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;230:543–574. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dunbrack RL, Cohen FE. Bayesian statistical analysis of protein sidechain rotamer preferences. Protein Science. 1997;6:1661–1681. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dunbrack RL, Karplus M. Rotamer libraries in the 21st century. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malakauskas SM, Mayo SL. Design, structure and stability of a hyperthermophilic protein variant. Nature Struct. Biol. 1998;5:470–475. doi: 10.1038/nsb0698-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Madadhain J, Fisher D, White S. JUNG: Java Universal Network/Graph Framework. http://jung.sourceforge.net. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corman T, Leiserson C, Rivest R. Introduction to Algorithms. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]