Abstract

Objectives

The high likelihood of recurrences in depression is linked to progressive increase in emotional reactivity to stress (stress sensitization). Mindfulness-based therapies teach mindfulness skills designed to decrease emotional reactivity in the face of negative-affect producing stressors. The primary aim of the current study was to assess whether Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) is efficacious in reducing emotional reactivity to social evaluative threat in a clinical sample with recurrent depression. A secondary aim was to assess whether improvement in emotional reactivity mediates improvements in depressive symptoms.

Methods

Fifty-two individuals with partially-remitted depression were randomized into an 8-week MBCT course or a waitlist control condition. All participants underwent the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) before and after the 8-week trial period. Emotional reactivity to stress was assessed with the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory at several time points before, during and after the stressor.

Results

MBCT was associated with decreased emotional reactivity to social stress, specifically during the recovery (post-stressor) phase of the TSST. Waitlist controls showed an increase in anticipatory (pre-stressor) anxiety, which was absent in the MBCT group. Improvements in emotional reactivity partially mediated improvements in depressive symptoms.

Limitations

Limitations include small sample size, lack of objective or treatment adherence measures, and non-generalizability to more severely depressed populations.

Conclusions

Given that emotional reactivity to stress is an important psychopathological process underlying the chronic and recurrent nature of depression, these findings suggest that mindfulness skills are important in adaptive emotion regulation when coping with stress.

Keywords: Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy, meditation, depression, emotional reactivity, Trier Social Stress Test

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a debilitating mood disorder that affects almost 19 million adults in the U.S at any given time (Narrow, 1998) and almost 20% of the U.S. population over a lifetime (Blazer, Kessler, McGonagle, & Swartz, 1994; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). MDD is recurrent and progressive, with the likelihood of repeated episodes increasing with each subsequent episode. Approximately 60% of individuals who had experienced one episode will experience a second episode whereas 90% of those who had experienced three episodes will have the fourth one (Judd, 1997; Mueller et al., 1999; Solomon et al., 2000). Thus, depression models attempt to explain not only why certain individuals are more likely to become depressed but also why the likelihood of recurrence increases with each subsequent episode (Hammen, 2005; Kendler, Thornton, & Gardner, 2000; Mitchell, Parker, Gladstone, Wilhelm, & Austin, 2003; Post, 2010; Segal, Gemar, & Williams, 1999; Segal et al., 2006; Segal, Williams, Teasdale, & Gemar, 1996).

Most theories posit an interaction between a latent but progressive vulnerability (diathesis) and negative life events (stress) (Abramson et al., 1999; Beck, 1987; Hankin, 2008; Hankin & Abramson, 2001). The relationship between depression and stress is complex and changes over time, such that earlier episodes are more likely than later episodes to be cued by major life stressors (Post, 1992; Stroud, Davila, & Moyer, 2008). Both biological (Post, 1992) and cognitive (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002) models hypothesize that individual (intra-personal) vulnerability risk processes are strengthened, and becomes more “autonomous” with each episode, such that lower levels of external provocation (stress) are needed to trigger a subsequent episode. This phenomenon was first termed “kindling”1(Post, 1992) and later became known as “stress sensitization” (Monroe & Harkness, 2005; Morris, Ciesla, & Garber, 2010; Post, 2010; Stroud, Davila, Hammen, & Vrshek-Schallhorn, 2011)1. Stress sensitization explains both the inter- and intra-individual variability in responses to stress, both in terms of differing thresholds of stress needed to trigger the same response, and differing magnitudes of response to the same stressor.

Cognitive theorists describe this progressive vulnerability as “cognitive reactivity”, or the activation of latent negative information processing biases in response to negative affect that serve to further escalate the negative affect into an episode (Teasdale, 1988). Biological theorists describe the diathesis as insufficient modulation of the limbic system by the prefrontal cortex, resulting in prolonged activation of the amygdala and sympathetic nervous system in response to stressors (Davidson, Pizzagalli, Nitschke, & Putnam, 2002; Drevets, 2001; Johnstone, van Reekum, Urry, Kalin, & Davidson, 2007; Ochsner, Bunge, Gross, & Gabrieli, 2002; Ochsner & Gross, 2005; Siegle, Steinhauer, Thase, Stenger, & Carter, 2002; Siegle, Thompson, Carter, Steinhauer, & Thase, 2007). Both theories report the progressive potentiation or kindling of this vulnerability, whether described in biological or cognitive terms (Post, 1992; Post, Rubinow, & Ballenger, 1984; Segal, Teasdale, Williams, & Gemar, 2002; Segal et al., 1996). The common end result in both models is progressively prolonged or intensified negative affect or “emotional reactivity” in response to stress, that puts individuals at risk for a depressive episode. For example, research has shown that heightened emotional reactivity to daily stress is a hallmark of depressive tendencies (Myin-Germeys et al., 2003; Pine, Cohen, & Brook, 2001) and a predictor of future depression (Cohen, Gunthert, Butler, O’Neill, & Tolpin, 2005; Pine et al., 2001) and poor treatment response (Cohen et al., 2008). Individuals with longer durations of negative affect following daily life stressors are more likely to develop depressive symptoms than those who recover more quickly (Cohen et al., 2005). This failure to “bounce back” from transient negative affect highlights the importance of negative affect regulation and affect recovery in depression research and treatment.

Mindfulness-based therapies such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) are meditation-based emotion regulation training programs that target emotional reactivity to stress in a wide range of clinical and non-clinical populations. While MBSR was created with broad clinical and non-clinical applications, MBCT was created by cognitively-oriented researchers specifically for use as depression relapse prevention (Segal et al., 2002). MBCT assumes that among people at risk for depression, life stress leads to dysphoria, which in turn activates negative thinking patterns, which further escalate the negative affect in a cycle that gradually progresses into a full-blown depressive episode (Segal et al., 2002; Segal et al., 1996). MBCT attempts to interrupt this process by teaching depressed patients to disidentfy with or “decenter” from negative self-evaluative or ruminative thinking patterns and interrupt the stress-induced positive feedback loop between negative affect and negative thinking patterns. Thus, although the associative network activated by stress includes both negative cognitions and negative feelings (Teasdale, 1988; Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995) MBCT largely emphasizes and targets the cognitive reactivity component of the cognition-affect cycle (Segal et al., 2002).

In accordance with this model, previous theoretical accounts and research have focused on cognitive reactivity as an important change process in MBCT. Cognitive reactivity is operationalized as the magnitude of change on the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (Weissman, 1979) in response to negative mood provocation or affective challenge paradigms which are intended to serve as “as manipulable experimental analogues for real-world environmental stressors” (Segal et al., 1999, p 8). Segal (2006) showed that greater cognitive reactivity after CBT or antidepressant medications (ADM) predicted higher rates of relapse over the course of 18 months. Moreover, patients who recovered with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) showed significantly less cognitive reactivity to affective challenge than those who recovered with ADM. Unlike CBT, MBCT aims to help patients hold negative thoughts (and feelings) in awareness rather diminishing them. Consistent with this, Kuyken et al (2010) found that individuals who had undergone MBCT had higher cognitive reactivity than those who received ADM, but the relationship between cognitive reactivity and relapse 15 months later was decoupled in the MBCT (but not the ADM) condition. In other words, depressed patients undergoing MBCT responded with increased activation in negative thinking while in a dysphoric mood, but this increase in cognitive activation did not result in affective deterioration2.

However, less attention has been paid to the affective component in the cognitive-affective associative network. Emotional reactivity, or the intensity and/or duration of negative affect in response to a stressor, is an important process believed to be changed in the course of MBCT (Segal et al., 2002). As an emotion regulation program, MBCT teaches patients to change their relationships with both negative thoughts and emotions, to hold them in awareness, and accept them with a nonjudgmental and compassionate attitude, instead of with a secondary layer of self-referential negative evaluation that serves to exacerbate them. Indeed, Kuyken et al. (2010) showed that developing a compassionate attitude toward one’s own negative thoughts and feelings mediated the effect of MBCT on depressive symptoms and relapse. As a result, the program is expected to help patients regulate their emotions more effectively in response to negative affect-producing stressors (Farb et al., 2007; Grant, Courtemanche, & Rainville, 2011; Segal et al., 1999). The application of MBCT in a broader sense, as an emotion regulation intervention is consistent with recent efforts to integrate cognitive, behavioral and biological models of depression and meditation through the study of emotion and integrate MBCT for depression with the prevailing affective neuroscience/emotion regulation models of the larger field of mindfulness and meditation research (Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009; Dakwar & Levin, 2009; De Raedt & Koster, 2010; Kuyken et al., 2010; Rottenberg & Johnson, 2007; Way, Creswell, Eisenberger, & Lieberman, 2010; Williams, 2010) .

Recently, MBCT has expanded beyond depression relapse prevention, and also beyond depression-specific cognitive reactivity theories into broader clinical applications and broader transdiagnostic emotion regulation models that combine cognitive, affective and biological approaches (Chambers et al., 2009; De Raedt & Koster, 2010; Way et al., 2010). MBCT (including the present study) has expanded into the treatment of acute or residual depression (Barnhofer et al., 2009; Britton, Haynes, Fridel, & Bootzin, 2010; Eisendrath et al., 2008; Finucane & Mercer, 2006; Kenny & Williams, 2007; Kingston, Dooley, Bates, Lawlor, & Malone, 2007; Kuyken et al., 2008; Manicavasgar, Parker, & Perich, in press; Schroevers & Brandsma, 2009; Shahar, Britton, Sbarra, Figueredo, & Bootzin, 2010; Williams et al., 2008) bipolar disorder (Williams et al., 2008), anxiety disorders (Evans et al., 2008; Finucane & Mercer, 2006; Kim et al., 2009; Lovas & Barsky, 2010; Piet, Hougaard, Hecksher, & Rosenberg, 2010; Schroevers & Brandsma, 2009) and conditions where emotional reactivity and regulation (rather than depression-specific cognitive reactivity) is the common unifying feature and treatment target (Baer, Fischer, & Huss, 2005; Foley, Baillie, Huxter, Price, & Sinclair, 2010; Oken et al., 2010; Rimes & Wingrove, 2010; Sachse, Keville, & Feigenbaum, 2011; Semple, Lee, Rosa, & Miller, 2009; van der Lee & Garssen, in press). Thus, the effects of MBCT on emotional reactivity in depression may have broad implications related to the transdiagnostic applications of MBCT specifically and mindfulness-based interventions in general.

A number of studies support the relationship between mindfulness and reduced emotional reactivity to stress, including attenuated emotional responses to threatening situations or faster recovery from transient negative affect (Arch & Craske, 2006, 2010; Brewer et al., 2009; Broderick, 2005; Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, & Hofmann, 2006; Creswell, Way, Eisenberger, & Lieberman, 2007; Erisman & Roemer, 2010; Goldin & Gross, 2010; Kaviani, Javaheri, & Hatami, 2011; Kuehner, Huffziger, & Liebsch, 2009; McKee, Zvolensky, Solomon, Bernstein, & Leen-Feldner, 2007; Ortner, Kilner, & Zelazo, 2007; Pace et al., 2009; Proulx, 2008; Raes et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2011; Vujanovic, Zvolensky, Bernstein, Feldner, & McLeish, 2007; Weinstein, Brown, & Ryan, 2009). For example, Arch and Craske (2006) found that undergraduate students who underwent a brief mindfulness induction (breath awareness) reported less negative emotional reactivity in response to affectively valenced slides compared to controls. Broderick (2005) found that undergraduate students assigned to a brief mindfulness meditation condition showed faster recovery from a sad mood induction compared to a distraction condition. Decreased emotional reactivity and better emotion regulation in meditators has also been reported using biological measures, including greater prefrontal inhibition of the amygdala (Brefczynski-Lewis, Lutz, Schaefer, Levinson, & Davidson, 2007; Creswell et al., 2007; Farb et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2011; Way et al., 2010) and decreased sympathetic hyperarousal (Barnes, Treiber, & Davis, 2001; Carlson, Speca, Faris, & Patel, 2007; Maclean et al., 1994; Ortner et al., 2007; Sudsuang, Chentanez, & Veluvan, 1991).

However, none of these studies examined whether MBCT directly influences the way depressed patients respond emotionally to stress. In addition, these studies suffer from other methodological limitations: Most of them used brief mindfulness induction (under 10 minutes) in undergraduate students or other non-clinical samples. Only two studies have demonstrated improved emotional reactivity (using personalized scripts) following a standard (8 week) mindfulness interventions in clinical samples (social anxiety and substance abuse) (Brewer et al., 2009; Goldin & Gross, 2010), but neither used a depressed sample undergoing MBCT.

Within the MBCT literature, very few studies have examined emotional reactivity to stress. Ma and Teasdale (2004) attempted to assess MBCT’s effect on stress-related relapse, but was unable to “examine directly the protective effects of MBCT in the face of different severities of environmental stress because the occurrence of events of those who did not relapse was not examined” (p. 39). Recently, Kaviani (2011) found that MBCT reduced depression and anxiety during a natural anticipated stressor (exam period) in a non-clinical sample of university students. Thus, at present, no studies have examined how MBCT directly influences the way depressed patients respond emotionally to stress.

In order to most fruitfully examine MBCT’s effects on emotional reactivity to stress with specific relevance for depression, a number of methodological issues must be considered. First, not all stressors are equal. Segal (2006) warned that the negative mood provocation method that is typically used to generate negative affect (i.e. sad music or negative slides) probably does not have the ecological validity of “being rejected by a social partner” (p. 755). Indeed, the most salient and impactful stressors and the ones that most commonly precipitate depressive episodes are interpersonal and involve social evaluation, rejection, or loss (Gunthert, Cohen, Butler, & Beck, 2007; Ingram, Miranda, & Segal, 1998; Leary, 2004).While more recent studies have recognized the importance of using social evaluative threat as the stressor rather than a generic emotional film, scripts or slides, (Creswell et al., 2007; Pace et al., 2009; Weinstein et al., 2009), none were intervention studies with clinical samples. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to investigate the effects on MBCT on emotional reactivity to an ecologically valid and provocative stressor (The Trier Social Stress Test (Kirschbaum, Pirke, & HellHammer, 1993).

Second, the time course of emotional reactions (“affective chronometry”) has been recently highlighted as important in the study of depression (Davidson, 2003; Davidson, Jackson, & Kalin, 2000). Davidson (2003) argued that “time course variables are particularly germane to understanding vulnerability to psychopathology, as certain forms of mood and anxiety disorders may be specifically associated with either a failure to turn off a response sufficiently quickly and/or an abnormally early onset of the response” (p.658). According to Davidson, emotional reactivity and regulation can occur at three distinct temporal windows: before, during and after the stressor. For example, he (Davidson, 2003) suggested less variability in emotional reactivity during an exposure to a negative affect-producing stimulus (emotion generation) and more variability in emotional reactivity after exposure to the stimulus is terminated (emotion regulation). Studies from his laboratory confirmed this by showing that people with different affective styles show different patterns of emotional reactivity only following exposure to a negative stimulus. For example, Jackson et al. (2003) found that prefrontal cortex activation asymmetry mostly explained variability in eyeblink startle magnitude following a negative stimulus, not during the stimulus. One notable shortcoming in such studies is the use of stimuli that are not ecologically valid (pictures) and the short time period in which reactivity was assessed (a few seconds after exposure to the stimulus). One purpose of the current study is to expand this research line by assessing emotional reactivity to a real-world stressor and by assessing reactivity during longer time periods following the stressor.

To summarize, the primary aim of the current study was to assess the effects of MBCT on emotion reactivity in order to further clarify how MBCT works and to expand the cognitive focus of MBCT into a broader emotion-regulation framework. A secondary aim was to explore whether MBCT’s effect on depressive symptoms are mediated by changes in emotion reactivity. In addition, we sought to address several methodological limitations that undermined previous research on emotional reactivity by a) assessing emotion reactivity during several time points before, during and after the stimulus and b) by using an externally valid, laboratory-based stressor that is known to provoke considerable stress. We examined our hypotheses in a wait-list randomized controlled trial of MBCT with in a sample of individuals with recurrent depression.

Methods

Participants

Participants (n=52) were recruited through community advertisements for a meditation-based depression-relapse prevention program. Consistent with Kuyken et al., (2008), the target population was individuals with a recurrent form of unipolar depression in partial or full remission with varying degrees of residual symptoms, because these individuals are considered at high risk for recurrence and because previous studies have shown that MBCT is effective for more recurrent forms of depression (Ma & Teasdale, 2004; Teasdale et al., 2000). A Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I (SCID-I) and Axis II (SCID-II) Disorders and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) were used to determine diagnostic eligibility. Participants met DSM-IV criteria for major depression at some point in the last 5 years and had a lifetime history of at least 3 episodes, but were in partial remission during the last 8 weeks with a varying degree of residual symptoms. Partial remission was defined by a subjectively reported improvement in symptoms in the last 2 months, HRSD score ≤ 20 and the exclusion of severely depressed mood (HRSD item #1 >2), severe anhedonia (HRSD item #7 >3) or active suicidal ideation (HRSD item #3 >2). Exclusion criteria included a) a history of bipolar disorder, cyclothymia, schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, persistent antisocial behavior or repeated self-harm, borderline personality disorder, organic brain damage, b) current panic, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorder, or substance abuse/dependence, c) inability to read/write in English, d) current psychotherapy or e) a regular meditation practice. Individuals on antidepressants were permitted to participate as long as they reported no change in medication type or dose during the three months prior to enrollment or during the active phase of the study.

Procedure

All participants were recruited through community advertisements from January 2004 through June 2005. Eligible participants participated in MBCT groups or waitlist from July 2004 through December 2005. Following a screening interview for diagnostic eligibility, participants completed a packet of self-report questionnaires and a 3-hour laboratory-based assessment that included the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) (Kirschbaum et al., 1993).

Participants were then block randomized to either the MBCT program or waitlist control condition in a 3:2 ratio without reference (stratification) to baseline characteristics to ensure rapid and adequate enrollment in the treatment arm. In blocks of 5, opaque, sealed letter-size envelopes with treatment allocation information were shuffled and placed in identical sequentially numbered containers and presented to the patients after successful completion of baseline assessments. Treatment allocation was recorded by the first author, who was also the intervention therapist, and therefore not blind to intervention allocation. Because baseline assessments were conducted before randomization, participants and research personnel were blind to treatment conditions during this phase of the project. After 8 weeks of treatment or waitlist condition, participants completed a post-treatment questionnaire packet and returned to the laboratory to repeat the TSST. Research personnel who collected or scored any post-baseline data also were blind to treatment conditions. Waitlisted subjects entered the next available wave of the MBCT program, after completing the second assessment. The sample size was calculated to have a power of .8 to detect a medium effect size for changes in depression and anxiety symptoms. A medium effect size has been found for depression and anxiety in two meta-analyses of MBCT/MBSR (Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004; Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010).

The study protocol was approved by the University of Arizona institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent for research participation. The study was conducted at the University of Arizona Department of Psychology. No adverse events occurred during the trial.

Laboratory-Based Stress Induction Procedure

Prior to laboratory assessment, participants completed 3 weeks of sleep diaries (to establish circadian timing). Laboratory assessments were scheduled in the late afternoon (around 5 pm) according to subject’s circadian time because circadian timing affects stress reactivity (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004). The Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) is a procedure that reliably produces moderate psychological distress in laboratory settings (Kirschbaum et al., 1993). In order to prompt evaluative self-focus, subjects delivered a speech in front of a one-way mirror and were told that a panel or judges were behind the mirror, evaluating their performance. The speech was made in front of a microphone, under two tripod-mounted 1000 watt halogen stage lights, in the presence of 2 video cameras with feedback to a closed circuit television. A judge in a white lab coat with a clipboard was seated directly in front of the subject and trained to give no social feedback. Participants were told that their performance was being recorded for later analysis. Subjects were given 5 minutes to prepare their speeches but were not allowed to use the notes they had prepared. The speech lasted for a full 5 minutes and was followed by a 5 minute serial subtraction task. If the subject paused, they were instructed to continue. At each laboratory assessment (before and after the treatment period), the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983) was administered at five time points: a) upon arrival in the laboratory, before the stressor (baseline), b) immediately after the stressor with reference to anxiety levels during the stressor (“How did you feel DURING the speech?”, c) immediately after the stressor (“How are you feeling now?”), d) 40 minutes and e) 90 minutes post-stressor offset. These time points were based on the chronometry of psychological and physiological reactivity to the TSST (Dickerson & Kemeny, 2004; Kirschbaum et al., 1993; Takahashi et al., 2005). Subjects were not instructed to try to alter or regulate their emotional response, although many individuals will repair negative affective states spontaneously in absence of instruction (Forgas & Ciarrochi, 2002; Hemenover, Augustine, Shulman, Tran, & Barlett, 2008).

A detailed, scripted manual of the TSST ensured consistent administration across sessions (Payne et al., 2006). Pre- and post-treatment TSST protocols differed only in the speech topic and the starting and subtraction numbers for the arithmetic task. All laboratory sessions were conducted by staff members that were blind to the treatment allocation or phase of the study.

Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (First, 2002) were used to assess current and past diagnostic status at entry into the study. In order to facilitate more accurate recall for past depression, participants were asked to make a list of all past depressions and bring it with them to the interview. The list included age, duration, estimated severity/impairment and if it was associated with an identifiable stressor. Reliability for a subset of interviews (10%) had over 90% agreement with an independent clinician for the diagnosis of MDD.

Depression History

History of past depression was assessed during the diagnostic assessment. As described above, participants were asked to describe the symptom severity and duration of each possible episode. All participants had at least 3 prior lifetime episodes. In cases where participants were unsure about being sufficiently symptom-free between episodes to identify distinct episodes, the number of episodes was determined, in some instances, based on the clinical judgment of the interviewer. Additionally, some patients reported a large number of short episodes whereas others reported fewer but longer episodes. Given this ambiguity about the distinctiveness of episodes and the variability in number of months of depression between patients, past depression was operationalized as the number of months over the course of their lives that patients met diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode.

Depression symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-24)(Gelenberg et al., 1990). The BDI is a 21-item self report measure that assesses depressive symptomatology, with an emphasis on cognitive symptoms. The BDI is a widely used measure of depressive symptoms and has excellent psychometric properties (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988)(alpha = .81. pre- treatment, .90 post-treatment).

The HRSD is a widely used clinician administered interview assessment of depressive symptomatology (Gelenberg et al., 1990). The HRSD and diagnostic interviews were conducted by the first author who was trained in administering the HSRD until an adequate level of reliability (> .90) with other raters of the same version was achieved. The HRSD-24 was used for screening purposes only (alpha= .77).

Emotional Reactivity to Social Stress

The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y (STAI-Y1;(Spielberger et al., 1983) is a 20-item self-report inventory where respondents rate their current levels of negative affect on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1=not at all to 4= very much so. The STAI was initially intended to assess anxiety, but has been more recently determined to measure a broader type of distress, a “higher order factor of negative affect” that incorporates both anxiety (worry, distressing thoughts) and depression (dysphoric mood and negative self-appraisal (Bieling, Antony, & Swinson, 1998; Caci, Bayle, Dossios, Robert, & Boyer, 2003; Gros, Antony, Simms, & McCabe, 2007). The STAI-Form Y demonstrates good psychometric properties, including strong internal consistency (alpha coefficients range between .86 and .95) in diverse adult and adolescent samples, adequate test-retest reliability, and convergent validity. In the current sample, internal consistency ranged from .89 to .93 and the intra-class correlation (ICC=.93) were high. Sensitivity to change, as measured by effect size (ηp2 = .44–55) and the standardized response mean (.99–1.1) for stress induction was high (see manipulation check section for details).

Mindfulness Meditation (MM) Practice Logs

Participants in the MBCT group kept track of their daily MM practice during the 8 weeks of active treatment. Diaries included information about the type of meditation, the number of minutes practiced and use of CD/tape. Logs for the preceding week were collected at each class meeting. See Britton et al 2010 for details.

Intervention

MBCT (Segal, Teasdale, & Williams, 2004; Segal et al., 2002; Teasdale, 2004) is an 8-week group-based intervention that combines principles from cognitive-behavioral therapy (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; (Kabat-Zinn, 1990) using a psychoeducational and client-centered format. MBCT sessions focus on cultivating mindfulness or non-judgmental present-moment awareness of mental content and everyday activities, including sitting, lying down, breathing, walking, and other simple movements. Homework assignments consisted of practicing mindfulness meditation exercises with the aid of a guided audio CD and completing worksheets related to stress, automatic thoughts, and common reactions to various types of events. A session-by session description with handouts and homework assignments is available in the MBCT manual (Segal et al., 2002). Sessions were conducted by the first author who had more than 10 years (approximately 3000 hours) of mindfulness practice experience and has received extensive training in delivery of the program through the Center for Mindfulness Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Instructor Certification Program at University of Massachusetts Medical School, and through MBCT training with Dr. Zindel Segal, the first author of the MBCT manual. Although treatment fidelity and adherence were not formally assessed, we have previously demonstrated that this MBCT intervention was efficacious in reducing residual depression symptoms, and increasing mindfulness (Mindful Attention Awareness scores), compared to controls (Shahar et al., 2010).

Statistical Analysis

Preliminary Analysis

Before analysis, all variables were examined for normality, and no outlying cases had significant influence on the results (as assessed by Cook’s Distance scores). Preliminary analyses were used to describe baseline characteristics, treatment retention and TSST manipulation checks, and to investigate any baseline group differences that might affect the main analyses.

Main Analysis

In order to examine the effect of the treatment on anxiety levels before and after MBCT, a 2×2×5 mixed model ANOVA was performed. The between groups factor was treatment (MBCT, control), and the within groups factors were time in relation to treatment (before treatment, after treatment) and time in relation to the TSST (before TSST, during the TSST, immediately after TSST, 40 minutes after TSST, 90 minutes after TSST). In accordance with Hamilton and Dobson (2002), we controlled for initial depression in all of our analyses, by entering baseline HRSD scores as a covariate. Data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 software. Statistical significance was set at alpha levels < 0.05, two-tailed. Results are reported as mean ± standard error (SE) or number/percentage unless otherwise indicated. Effect sizes were reported as partial η2 (ηp2; small=.01, medium=.06, large=.14) (Green & Salkind, 2005).

Secondary (mediational) analysis: An SPSS Macro (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) was used in order to examine whether improvements in anxiety regulation (emotion reactivity) mediated the effects of MBCT on depressive symptoms. In order to conduct this analysis we first computed a mean anxiety score for each participant based on his/her anxiety scores on all five assessments during the TSST. We then computed anxiety change scores by subtracting the pre-treatment anxiety score from the post-treatment anxiety score. We also computed depression change scores by subtracting pre-treatment BDI scores from post-treatment BDI scores. Despite concerns that difference scores are unreliable, Rogosa and Willett (1983) showed that change scores are reliable estimates of change when individual differences in true change do exist.

Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) approach is based on a bootstrapping procedure that extends Baron and Kenny (1986) regression-based causal steps approach and the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) for the significance level of indirect effect. In short, because the distribution of the indirect effect often deviates from normality, especially in small samples (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004) the bootstrapping approach yields more accurate 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effect.

Results

Participant Flow and sample characteristics

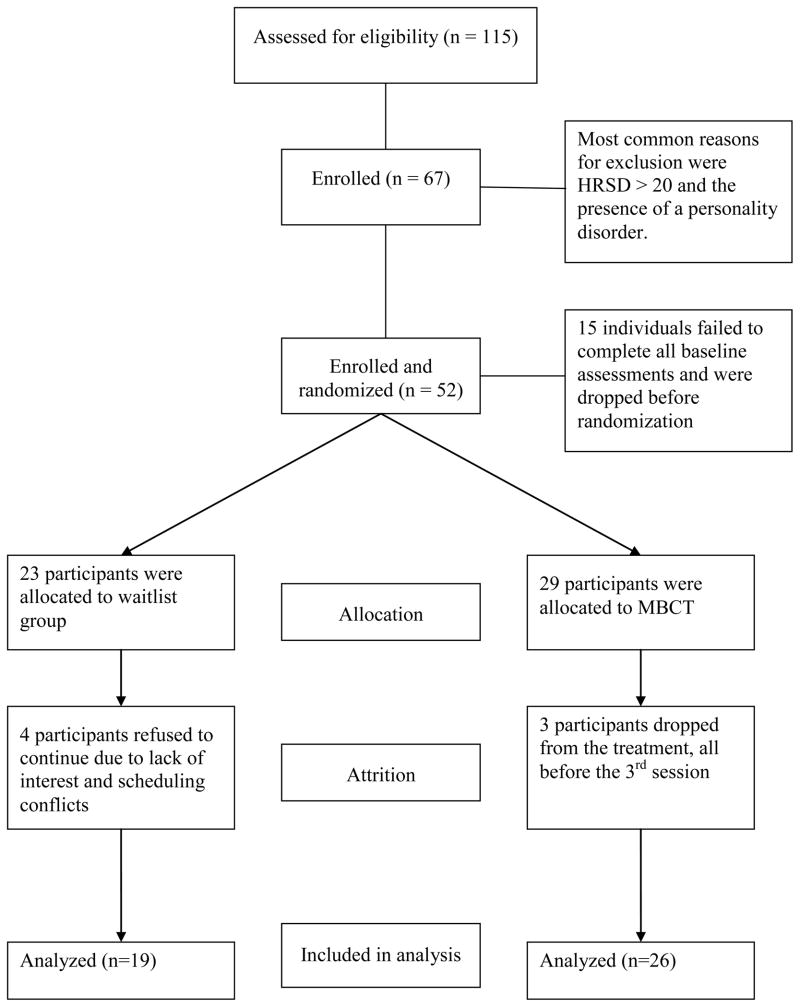

Of the 52 participants that completed baseline assessments, 23 were randomized to waitlist and 29 to MBCT. Twenty-six (90%) MBCT and 19 (82%) waitlisted participants completed all assessments (total n=45). Out of the 29 participants randomized to MBCT, 3 dropped out before the third class. Of the remaining 26, 25 (96.2%) attended at least 7 of the 8 sessions, one person attended 6 sessions, and all attended the all-day retreat. Figure 1 displays the participants’ flow chart. Sample characteristics by treatment group and completion status are displayed in Table 1. Treatment groups and completers vs non-completers did not differ on any variable including age, sex, use of antidepressant medications, depression severity or previous months of depression.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of MBCT and waitlist samples

| All (n=52) | Completers (n=45) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | MBCT ((N=29) | Waitlist (N=23) | MBCT (N=26) | Waitlist (N=19) |

| Female % | 79.3 | 87.0 | 76.92 | 94.74 |

| Age M (SE) | 47.0 (1.39) | 47.83 (2.28) | 46.58 (1.52) | 46.74 (2.68) |

| Months depressed M | 59.55 (7.10) | 61.70 (8.15) | 59.85 (7.88) | 61.89 (8.97) |

| On AD (%) | 47.7 | 52.2 | 50.00 | 57.90 |

| BDI M (SE) | 9.09 (1.08) | 9.83 (1.27) | 9.10 (1.19) | 10.16 (1.4) |

| HRSD M (SE) | 10.38 (1.13) | 13.17 (1.38) | 10.50 (1.25) | 13.32 (1.48) |

Note. MBCT = Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy; Months Depressed = total number of months of previous depression across all episodes; AD = antidepressant medication; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; HRSD= Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression.

Mindfulness Meditation (MM) practice

Outside of class, the 27 completers reported engaging in formal MM practice an average of 39.94 ± 10 minutes/day, 5.2 ± 1.2 days/week. According to the goal of 45 minutes/day, 6 days/week of formal MM practice (270 minutes/week = 100%), the mean meditation minutes across all weeks was 76 ± 24% with a range of 79 to 308 minutes/week.

Manipulation Check: TSST reliably induces negative affect

We conducted a series of analyses to evaluate the effectiveness of the TSST in producing negative affect/anxiety, and to assess whether repeated administration led to an attenuated response (i.e. habituation). Using the change between baseline and the report of anxiety during the speech, the TSST produced a significant increase in anxiety for all participants at both pre- [t(44) = 7.5, p<.001 ηp2 = .55] and post-treatment [t(44) = 5.9, p<.001, ηp2 = .44]. There was no attenuation in the peak level of anxiety produced by the TSST from pre- to post-treatment assessment (STAI score during speech at pre-treatment = 53.4 ± 10.9, at post-treatment = 50.7 ± 11.12, time main effect, F(42) = 2.3, p = .14).

Main Analyses: The effect of the treatment on emotional reactivity to social stress

The ANOVA failed to find a significant three-way interaction between treatment group, time in relation to treatment, and time in relation to task, indicating that the trajectory of anxiety scores over time was similar in both MBCT and control groups (see Figure 2). However, a significant two-way interaction between treatment and time in relation to treatment was found, F(1,42) = 6.20, p < .05, ηp2 = .13. Simple effects analyses showed that whereas average anxiety rates (collapsing across time in relation to task) decreased in the MBCT group, they did not decrease in the control group (see Table 2).

Figure 2.

Anxiety scores pre- and post-treatment displayed separately for controls (top) and MBCT (bottom). Baseline= immediately prior to the TSST; During speech= anxiety level while the TSST was occurring; Post-speech= anxiety level at the conclusion of the TSST; 40 min= anxiety level approximately 40 minutes after the TSST had concluded; 90 min= anxiety level approximately 90 after the TSST had concluded

***p < .005, **p<.01, *p<.05

Table 2.

Mean (SE) Anxiety Levels Before, During, Immediately After, 40 Minutes After, and 90 Minutes After the TSST, as a Function of the Time of Measurement (Pre or Post Treatment) and the Type of Treatment (MBCT, Control)

| MBCT | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Pre-Tx | Post-Tx | F(1,42) | Pre-Tx | Post-Tx | F(1,42) | |

| Baseline | 40.77 (1.54) | 40.39 (1.80) | 0.05 | 41.40 (1.90) | 46.02 (2.22) | 4.78* |

| During speech | 52.88 (2.24) | 49.53 (2.13) | 3.01 | 54.07 (2.75) | 52.37 (2.62) | 0.51 |

| Post speech | 45.72 (2.02) | 37.92 (1.80) | 28.36*** | 46.92 (2.48) | 45.02 (2.21) | 0.87 |

| 40 min. | 40.94 (1.96) | 35.44 (1.52) | 11.19** | 42.09 (2.41) | 40.89 (1.87) | 0.35 |

| 90 min. | 38.55 (2.07) | 34.46 (1.88) | 8.34** | 40.95 (2.54) | 42.63 (2.31) | 0.94 |

| Overall | 43.77 (1.60) | 39.55 (1.53) | 13.57*** | 45.04 (1.96) | 45.39 (1.89) | 0.06 |

Pre-Tx= Before treatment (week 0); Post-Tx= after treatment (week 9); Baseline= immediately prior to the TSST; During speech= anxiety level while the TSST was occurring; Post-speech= anxiety level at the conclusion of the TSST; 40 min= anxiety level approximately 40 minutes after the TSST had concluded; 90 min= anxiety level approximately 90 after the TSST had concluded.

p < .005,

p<.01,

p<.05

In order to further understand the exact manner in which MBCT decreased anxiety rates, the difference between pre-treatment anxiety and post-treatment anxiety was examined at each TSST time point for the MBCT group and the control group separately. In the control group, a significant increase in pre-speech anxiety was found, followed by non-significant differences at each other measurement points. In contrast, in the MBCT group, no difference was found in pre-speech anxiety and anxiety during the speech, but significant decreases in anxiety rates were recorded at each of the other three post-speech measurement points. Means and F values are presented in Table 2.

Secondary mediational analysis

The effect of treatment on change in depression (c path) was significant (β = −.42, p < .01). In addition, the effect of treatment on change in anxiety (a path) was marginally significant (β = −.27, p = .07), and the direct effect of change in anxiety on change in depression (b path) was significant (β = .39, p < .01). When change in anxiety was taken into account, the direct effect of treatment on depression (c’ path) decreased in relation to the overall effect (c path), although it stayed significant (β = −.31, p < .05). Bootstrapped .95 confidence intervals for the mediated effect did not include 0, indicating that the indirect effect of MBCT on depressive symptoms through changes in anxiety was significant. Overall, the results suggested that improvements in anxiety regulation reliably (although partially) mediated the effects of MBCT on depressive symptoms.

Discussion

This study assessed the effects of MBCT on emotional reactivity to a laboratory-based social evaluative threat in a sample with partially remitted recurrent depression. The main results were the following: MBCT was associated with an overall decrease in emotional reactivity. Overall anxiety levels (collapsed across all TSST time points) decreased significantly for the MBCT group, but not controls, when compared to pre-treatment levels. A closer examination of specific assessment points during the TSST revealed that this decreased emotional reactivity in the MBCT group was specific to the post-stressor recovery phase. The MBCT group showed an attenuation of negative affect/anxiety at all post-stressor time points compared to pre-treatment baseline, while post-speech anxiety levels did not change from pre-treatment among participants in the control group. Before treatment, anxiety levels in all participants remained elevated following the speech, and did not return to pre-speech baseline levels until 40 minutes after the speech had concluded. After treatment, anxiety levels in MBCT group returned to baseline levels immediately after the speech had concluded (i.e. 40 minutes earlier than before treatment). These data suggest that MBCT training is associated with a faster affective recovery from potent negative-affect producing stressors. Furthermore, the mediational analysis showed that MBCT’s positive effects on depressive symptoms was partially mediated by these improvements in anxiety regulation.

Examination of the pre-stressor time point (i.e. anticipatory anxiety before the speech) also suggests a beneficial effect of MBCT participation. The control group showed an increase in pre-speech anxiety at post-treatment compared to pre-treatment, which indicates an increased sensitization to stress in the control group in the form of more anticipatory anxiety (i.e. larger emotional response to same stressor). The MBCT group experienced similar levels of pre-task anxiety before and after treatment. i.e., they did not experience stress sensitization that the control participants experienced. These findings suggest that MBCT may help depressed patients to better regulate their anticipatory anxiety before anticipated stressors. We believe that the findings regarding better regulation of anticipatory anxiety are particularly important because anticipatory anxiety affects the intensity of response to subsequent stressors and plays an important role in anxiety disorders (Grillon, Ameli, Foot, & Davis, 1993), and mortality risk (Peterson, Seligman, Yurko, Martin, & Friedman, 1998).

Although MBCT was associated with an overall decrease in stress-related anxiety, these changes were specific to pre- and post -stressor anxiety and not anxiety during the stressor. Similarly, other studies (Farb et al., 2010; Kuyken et al., 2010) also found no difference in the magnitude of immediate emotional in response to provocation following eight weeks of mindfulness training or control treatment. Rather, increased duration of negative affect following a stressor, rather than the initial intensity, is associated with depression risk (Cohen et al., 2005; Gillihan et al., 2010). Similarly, Jackson et al., (2003) found that an affective style characteristic of depression (less left-side activation in the prefrontal cortex) was associated with increased emotion reactivity after picture presentation but not during picture presentation. This is consistent with the idea that emotional reactions to stress, including negative affect and physiological arousal, are adaptive (up to a point) and need not be eliminated (Mayne, 2001; McEwen & Seeman, 1999). Rapid recovery after the stressor has passed is also adaptive, as prolonged arousal and negative affect can deplete the organism’s resources and increase risk for depression. Our data suggest that mindfulness training may exert a nuanced effect that is specific to the horizontal time course (chronometry) rather than a generalized suppression or blunting of the intensity or amplitude of emotional responses (Taylor et al., 2011).

These data have clinical relevance for the treatment of depression specifically, for the treatment of conditions where poor affect regulation is a central target (addictions) and for mindfulness and meditation-based interventions in general. In depression, the potentiation or prolongation of negative affect, which may be indicative of poor prefrontal control of the amygdala, and/or activation of negative cognitive schemas (cognitive reactivity) (De Raedt & Koster, 2010) is associated with higher likelihood of current and future depression as well as poor treatment response (Cohen et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2008; Myin-Germeys et al., 2003; Pine et al., 2001) and is therefore a central treatment target. Our data suggests that MBCT can effectively target such reactivity and that this effects at least partially mediates improvement in residual depressive symptoms which reliably predicts relapse.

In addition to depression, a broad range of emotional disturbances characterized by persistent negative affect are associated with poor emotional regulation, high emotional reactivity and/or poor prefrontal control (Baxter et al., 1989; Bench, Friston, Brown, Frackowiak, & Dolan, 1993; Clark, Chamberlain, & Sahakian, 2009; Couyoumdjian et al., 2009; Hemenover, 2003; Mayberg et al., 1999; Meyer et al., 2004; Siegle & Hasselmo, 2002). It has been proposed that the broad therapeutic effects of mindfulness meditation are mediated by strengthening prefrontal attention and emotion regulation systems (Chambers et al., 2009; Creswell et al., 2007; Davidson & Lutz, 2008; Hofmann & Asmundson, 2008; Teasdale et al., 1995; Way et al., 2010). Davidson (2003) hypothesized that the greater prefrontal control of the amygdala (Brefczynski-Lewis et al., 2007; Creswell et al., 2007; Farb et al., 2007; Goldin & Gross, 2010; Taylor et al., 2011; Way et al., 2010), or the decoupling from self-referential elaboration (Farb et al., 2010; Farb et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2011) would result in greater capacity to regulate negative emotion and specifically “to decrease the duration of negative affect once it arises” (p. 662), in other words, hasten affective recovery.

“Excessive identification with the negative emotion should result in a perseveration or lingering of the negative affect, following the offset of the acute elicitor. We might thus expect that the largest temporal region during which a transformation in the affective reaction might occur is in the post-stimulus recovery period following the offset of a negative stimulus. In other words, meditation training should speed the recovery following the offset of a negative stimulus” (Davidson, 2010, p 10)

The findings from this study add to the growing support for these emotion regulation models of mindfulness, and integrate MBCT for depression within larger affective neuroscience models of meditation.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first to use a potent, standardized laboratory-based social evaluative stressor before and after a randomized controlled trial of MBCT in a depressed population. This study also addressed the emotional component of MBCT’s theoretical framework which may have broader applications than depression-specific cognitive reactivity focus. At the same time, although the current study demonstrates that MBCT reduces emotional reactivity, it does not address the mechanism of action, or how this reduction is accomplished. It is hypothesized that this therapeutic target is achieved through teaching patients to hold their thoughts and feelings in awareness while adopting a patient, compassionate, and nonjudgmental attitude toward these feelings. Kuyken et al. (2010) findings that self-compassion mediate MBCT’s effects on outcome support this hypothesis. Because MBCT uses a variety of meditative techniques, it is difficult to sort out which techniques are related to which outcomes, so future studies may also want to consider dismantling designs (Kuyken et al., 2010; Murphy, Cooper, Hollon, & Fairburn, 2009).

The present study has several other limitations, most notably the small sample size and the limited statistical power. The specificity of the sample (partially remitted recurrent depression) is both a strength and a limitation: Individuals with 3+ episodes and residual symptoms represent the population that most benefits from MBCT (Ma & Teasdale, 2004; Teasdale et al., 2000) as well as those at highest risk for recurrence. However, the high number of exclusion criteria may limit the ability to generalize to more severely depressed samples or other clinical populations. The use of an 8-week mindfulness course limits the ability to speculate on the effects of other forms of meditation or the effects of longer durations of training. The classic limitations of a wait-list control design include the possibility of expectancy effects and differential attrition. While the MBCT group’s previously reported increase in mindfulness and improvement in depression is consistent with other studies where high quality MBCT was administered, checks on competency (Crane, Kuyken, Hastings, Rothwell, & Williams, 2010) and adherence (Segal et al., 2002) should be included in future research to ensure treatment fidelity.

Because self-report measures, like the STAI, are sensitive to bias and demand characteristics, use of objective measures would lend convergent validity to these findings. Furthermore, use of continuous, rather than repeated, measures would yield more fine-grained information about the timecourse of affective responding. While the current study suggests that MBCT decreases emotional reactivity to social stress, the clinical significance is unknown. Given that prolonged negative affect in response to stress is a marker of depression vulnerability (Cohen et al., 2005; Gillihan et al., 2010) and treatment response (Cohen et al., 2008; Davidson et al., 2002), future research should investigate whether this decreased emotional reactivity predicts relapse/sustained recovery from depression, as well as the relationship between and the respective contributions of cognitive and emotional reactivity, using appropriate designs (Kazdin, 2007; Kraemer, Kiernan, Essex, & Kupfer, 2008; Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study suggests that mindfulness meditation training is associated with decreased emotional reactivity in the face of a negative-affect producing stressor and that this improvement in emotional reactivity is at least partially responsible for the program’s effect on depressive symptoms. By providing evidence of faster affective recovery in a (stress-sensitive) chronically depressed sample, this study strengthens the empirical basis for applying mindfulness-based approaches to depressed samples, as well as other conditions with poor affect regulation.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by grants T32-AT001287, MH067553-05 from the National Institutes of Health, the Mind and Life Institute, the American Association for University Women grant, and Philanthropic Educational Organization (Willoughby Britton). We give special thanks to the research assistants at the University of Arizona Research Laboratory for their time and effort

Role of Funding Source:

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health, the Mind and Life Institute, the American Association for University Women, and Philanthropic Educations Organization; the sponsors had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

APPENDIX. CONSORT Checklist 2010 as separate attachment

| CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomised trial*

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Section/Topic | Item No | Checklist item | Reported on page No |

| Title and abstract | |||

| 1a | Identification as a randomised trial in the title | 1

|

|

| 1b | Structured summary of trial design, methods, results, and conclusions (for specific guidance see CONSORT for abstracts) | 2

|

|

| Introduction | |||

| Background and objectives | 2a | Scientific background and explanation of rationale | 4-12

|

| 2b | Specific objectives or hypotheses | 11-12

|

|

| Methods | |||

| Trial design | 3a | Description of trial design (such as parallel, factorial) including allocation ratio | 13-14

|

| 3b | Important changes to methods after trial commencement (such as eligibility criteria), with reasons | ||

| Participants | 4a | Eligibility criteria for participants | 12-13

|

| 4b | Settings and locations where the data were collected | 14

|

|

| Interventions | 5 | The interventions for each group with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered | 18

|

| Outcomes | 6a | Completely defined pre-specified primary and secondary outcome measures, including how and when they were assessed | 14-18

|

| 6b | Any changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced, with reasons | ||

| Sample size | 7a | How sample size was determined | 14

|

| 7b | When applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines | ||

| Randomisation: | |||

| Sequence generation | 8a | Method used to generate the random allocation sequence | 13-14

|

| 8b | Type of randomisation; details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size) | 13-14

|

|

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 9 | Mechanism used to implement the random allocation sequence (such as sequentially numbered containers), describing any steps taken to conceal the sequence until interventions were assigned | 13-14

|

| Implementation | 10 | Who generated the random allocation sequence, who enrolled participants, and who assigned participants to interventions | 13-14

|

| Blinding | 11a | If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how | 14

|

| 11b | If relevant, description of the similarity of interventions | ||

| Statistical methods | 12a | Statistical methods used to compare groups for primary and secondary outcomes | 19-20

|

| 12b | Methods for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses | 19-20

|

|

| Results | |||

| Participant flow (a diagram is strongly recommended) | 13a | For each group, the numbers of participants who were randomly assigned, received intended treatment, and were analysed for the primary outcome | 20

|

| 13b | For each group, losses and exclusions after randomisation, together with reasons | 20

|

|

| Recruitment | 14a | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up | 13

|

| 14b | Why the trial ended or was stopped | ||

| Baseline data | 15 | A table showing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics for each group | 32

|

| Numbers analysed | 16 | For each group, number of participants (denominator) included in each analysis and whether the analysis was by original assigned groups | 20

|

| Outcomes and estimation | 17a | For each primary and secondary outcome, results for each group, and the estimated effect size and its precision (such as 95% confidence interval) | 21-22

|

| 17b | For binary outcomes, presentation of both absolute and relative effect sizes is recommended | ||

| Ancillary analyses | 18 | Results of any other analyses performed, including subgroup analyses and adjusted analyses, distinguishing pre- specified from exploratory | |

| Harms | 19 | All important harms or unintended effects in each group (for specific guidance see CONSORT for harms) | 14

|

| Discussion | |||

| Limitations | 20 | Trial limitations, addressing sources of potential bias, imprecision, and, if relevant, multiplicity of analyses | 26-27

|

| Generalisability | 21 | Generalisability (external validity, applicability) of the trial findings | 26-27

|

| Interpretation | 22 | Interpretation consistent with results, balancing benefits and harms, and considering other relevant evidence | 23-26

|

| Other information | |||

| Registration | 23 | Registration number and name of trial registry | 29

|

| Protocol | 24 | Where the full trial protocol can be accessed, if available | |

| Funding | 25 | Sources of funding and other support (such as supply of drugs), role of funders | 29 |

Footnotes

Increased “autonomy” in this context means “decreased reliance on stress”, but it should not be confused with the “Stress Autonomy” model which states that the decoupling of stress and depression means that stressful events are no longer capable of triggering a depression. See Monroe and Harkness 2005.

On the other hand, see findings by Raes, Dewulf, Van Heeringen, & Williams (2009) for findings showing less cognitive reactivity after MBCT. Clearly, these inconsistent results regarding the role of cognitive reactivity need further study but they are not the focus of the current study.

Conflict of Interest: This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramson L, Alloy L, Hogan M, Whitehouse W, Donovan P, Rose D, et al. Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1999;13:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1849–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Craske MG. Laboratory stressors in clinically anxious and non-anxious individuals: the moderating role of mindfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Fischer S, Huss DB. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy applied to binge eating: A case study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12:351–358. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes VA, Treiber FA, Davis H. Impact of Transcendental Meditation on cardiovascular function at rest and during acute stress in adolescents with high normal blood pressure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2001;51:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhofer T, Crane C, Hargus E, Amarasinghe M, Winder R, Williams JM. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as a treatment for chronic depression: A preliminary study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter LR, Jr, Schwartz JM, Phelps ME, Mazziotta JC, Guze BH, Selin CE, et al. Reduction of prefrontal cortex glucose metabolism common to three types of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:243–250. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810030049007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. Cognitive models of depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 1987;1:5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R, Garbin M. Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BE, Emery G. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bench CJ, Friston KJ, Brown RG, Frackowiak RS, Dolan RJ. Regional cerebral blood flow in depression measured by positron emission tomography: the relationship with clinical dimensions. Psychological Medicine. 1993;23:579–590. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, Antony MM, Swinson RP. The State–Trait Anxiety Inventory, trait version: Structure and content re-examined. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:777–788. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The national comorbidity survey. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Lutz A, Schaefer HS, Levinson DB, Davidson RJ. Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2007;104:11483–11488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606552104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Sinha R, Chen JA, Michalsen RN, Babuscio TA, Nich C, et al. Mindfulness training and stress reactivity in substance abuse: results from a randomized, controlled stage I pilot study. Substance Abuse. 2009;30:306–317. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton WB, Haynes PL, Fridel KW, Bootzin RR. Polysomnographic and subjective measures of sleep continuity before and after Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in partially remitted depression. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72:539–548. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181dc1bad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick P. Mindfulness and coping with dysphoric mood: Contrasts with rumination and distraction. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29:501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Caci H, Bayle FJ, Dossios C, Robert P, Boyer P. The Spielberger trait anxiety inventory measures more than anxiety. European Psychiatry. 2003;18:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Barlow D, Brown T, Hofmann S. Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1251–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, Patel KD. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behavior and Immunity. 2007;21:1038–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers R, Gullone E, Allen NB. Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms in depression: implications for treatment. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32:57–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LH, Gunthert KC, Butler AC, O’Neill SC, Tolpin LH. Daily affective reactivity as a prospective predictor of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1687–1713. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2005.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LH, Gunthert KC, Butler AC, Parrish BP, Wenze SJ, Beck JS. Negative affective spillover from daily events predicts early response to cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:955–965. doi: 10.1037/a0014131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couyoumdjian A, Sdoia S, Tempesta D, Curcio G, Rastellini E, LDEG, et al. The effects of sleep and sleep deprivation on task-switching performance. Journal of Sleep Research. 2009;19:64–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane R, Kuyken W, Hastings RP, Rothwell N, Williams JMG. Training teachers to deliver mindfulness-based interventions: Learning from the UK experience. Mindfulness. 2010;1:74–86. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0010-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J, Way B, Eisenberger N, Lieberman M. Neural correlates of dispositional mindfulness during affect labeling. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:560–565. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180f6171f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakwar E, Levin FR. The emerging role of meditation in addressing psychiatric illness, with a focus on substance use disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2009;17:254–267. doi: 10.1080/10673220903149135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R, Lutz A. Buddha’s Brain: Neuroplasticity and Meditation. IEEE Signal Processing. 2008;25:171–174. doi: 10.1109/msp.2008.4431873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Affective neuroscience and psychophysiology: toward a synthesis. Psychophysiology. 2003;40:655–665. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Empirical explorations of mindfulness: conceptual and methodological conundrums. Emotion. 2010;10:8–11. doi: 10.1037/a0018480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Jackson DC, Kalin NH. Emotion, plasticity, context, and regulation: perspectives from affective neuroscience. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:890–909. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Pizzagalli D, Nitschke JB, Putnam KM. Depression, perspectives from affective neuroscience. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:545–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Raedt R, Koster E. Understanding vulnerability for depression from a cognitive neuroscience perspective: A reappraisal of attentional factors and a new conceptual framework. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10:50–70. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC. Neuroimaging and neuropathological studies of depression: implications for the cognitive-emotional features of mood disorders. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2001;11:240–249. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisendrath SJ, Delucchi K, Bitner R, Fenimore P, Smit M, McLane M. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for treatment-resistant depression: a pilot study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2008;77:319–320. doi: 10.1159/000142525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisman SM, Roemer L. A preliminary investigation of the effects of experimentally induced mindfulness on emotional responding to film clips. Emotion. 2010;10:72–82. doi: 10.1037/a0017162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Ferrando S, Findler M, Stowell C, Smart C, Haglin D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:716–721. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farb NA, Anderson AK, Mayberg H, Bean J, McKeon D, Segal ZV. Minding one’s emotions: mindfulness training alters the neural expression of sadness. Emotion. 2010;10:25–33. doi: 10.1037/a0017151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farb NA, Segal ZV, Mayberg H, Bean J, McKeon D, Fatima Z, et al. Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2007;2:313–322. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane A, Mercer SW. An exploratory mixed methods study of the acceptability and effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for patients with active depression and anxiety in primary care. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) [Google Scholar]

- Foley E, Baillie A, Huxter M, Price M, Sinclair E. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for individuals whose lives have been affected by cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:72–79. doi: 10.1037/a0017566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgas J, Ciarrochi J. On managing moods: Evidence for the role of homeostatic cognitive strategies in affect regulation. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:336–345. [Google Scholar]

- Gelenberg AJ, Wojcik JD, Falk WE, Baldessarini RJ, Zeisel SH, Schoenfeld D, et al. Tyrosine for depression: a double-blind trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1990;19:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillihan S, Rao H, Wang J, Detre J, Breland J, Sankoorikal G, et al. Serotonin transporter genotype modulates amygdala activity during mood regulation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5:1–10. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Gross JJ. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion. 2010;10:83–91. doi: 10.1037/a0018441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JA, Courtemanche J, Rainville P. A non-elaborative mental stance and decoupling of executive and pain-related cortices predicts low pain sensitivity in Zen meditators. Pain. 2011;152:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S, Salkind N. Using SPSS for Windows and Macintosh: Analyzing and understanding data. 4. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Ameli R, Foot M, Davis M. Fear-potentiated startle: relationship to the level of state/trait anxiety in healthy subjects. Biological Psychiatry. 1993;33:566–574. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90094-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Antony MM, Simms LJ, McCabe RE. Psychometric properties of the State-Trait Inventory for Cognitive and Somatic Anxiety (STICSA): comparison to the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:369–381. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthert K, Cohen L, Butler A, Beck J. Depression and next-day spillover of negative mood and depressive cognitions following interpersonal stress. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2007;31:521–532. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KE, Dobson KS. Cognitive therapy of depression: pre-treatment patient predictors of outcome. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:875–893. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Cognitive vulnerability-stress model of depression during adolescence: investigating depressive symptom specificity in a multi-wave prospective study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:999–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: an elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemenover SH. Individual differences in rate of affect change: studies in affective chronometry. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:121–131. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemenover SH, Augustine AA, Shulman T, Tran TQ, Barlett CP. Individual differences in negative affect repair. Emotion. 2008;8:468–478. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Asmundson GJ. Acceptance and mindfulness-based therapy: new wave or old hat? Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram R, Miranda J, Segal Z. Proximal and distal perspectives: An integrative approach to cognitive vulnerability. In: Ingram R, Miranda J, Segal Z, editors. Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression. New York: Guilford; 1998. pp. 226–265. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DC, Mueller CJ, Dolski I, Dalton KM, Nitschke JB, Urry HL, et al. Now you feel it, now you don’t: frontal brain electrical asymmetry and individual differences in emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2003;14:612–617. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone T, van Reekum CM, Urry HL, Kalin NH, Davidson RJ. Failure to regulate: counterproductive recruitment of top-down prefrontal-subcortical circuitry in major depression. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:8877–8884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2063-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL. The clinical course of unipolar major depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:989–991. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Delacorte Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kaviani H, Javaheri F, Hatami N. Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) reduces depression and anxiety induced by real stressful setting in non-clinical population. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2011;11:285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Thornton LM, Gardner CO. Stressful life events and previous episodes in the etiology of major depression in women: an evaluation of the “kindling” hypothesis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1243–1251. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny MA, Williams JM. Treatment-resistant depressed patients show a good response to Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YW, Lee SH, Choi TK, Suh SY, Kim B, Kim CM, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as an adjuvant to pharmacotherapy in patients with panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:601–606. doi: 10.1002/da.20552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston T, Dooley B, Bates A, Lawlor E, Malone K. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2007;80:193–203. doi: 10.1348/147608306X116016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, HellHammer DH. The Trier Social Stress Test”: A tool for investigating psychobiological stress response in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Kiernan M, Essex M, Kupfer D. How and why criteria defining moderators and mediators differ between the Baron & Kenny and MacArthur approaches. Health Psychology. 2008;27:S101–108. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H, Wilson T, Fairburn C, Agras W. Mediators and Moderators of Treatment Effects in Randomized Clinical Trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]