Abstract

When specialists propose screening guidelines for primary care clinicians to implement, differences in perspectives between the 2 groups can create conflicts. Two recent specialty organization guidelines illustrate this issue. The American Urological Association guideline panel and National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend that average-risk men first be counseled about the risks and benefits of prostate-specific antigen screening for prostate cancer at age 40 rather than at the previously recommended age of 50 years. There is no direct evidence, however, that this recommendation has any impact on prostate cancer-specific mortality. To avoid distracting primary care clinicians from providing services with proven benefit and value for patients, professional organizations should follow appropriate standards for developing guidelines. Primary care societies and health care systems should also be encouraged to evaluate the evidence and decide whether implementing the recommendations are feasible and appropriate.

Key words: prostate-specific antigen, early detection of cancer, guidelines as topic, evidence-based medicine

Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.

Rudyard Kipling, The Ballad of East and West

PRIMARY CARE VS SPECIALIST PERSPECTIVES ON CANCER SCREENING

Should primary care clinicians adopt guidelines developed primarily by specialists? We believe the answer should depend on the quality of the evidence and the appropriateness and feasibility of implementing the guideline. Compared with primary care clinicians, specialists care for disproportionate numbers of patients with advanced-stage disease. Both groups of physicians have the same goals of minimizing morbidity and mortality from the diseases that they treat, but specialists are not under the same obligation to weigh priorities across all diseases. These different perspectives can create conflict when specialists propose screening guidelines. We illustrate this conflict with the case of prostate cancer screening in younger men.

Rationale for Screening at an Earlier Age

Owing to inconclusive evidence, past prostate cancer screening guidelines from specialist physicians have differed sharply from those of generalist clinicians.1-3 By applying better evidence, screening recommendations have converged toward a consensus that men should be informed of the benefits and harms of screening. Now, however, 2 prominent specialty groups have issued guidelines that adhere to the spirit of informed decision making, but have extended the recommendations to younger men. These guidelines illustrate the consequences of conflicting perspectives.

In 2009, the American Urological Association (AUA) released a guideline on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening for prostate cancer.4 The guideline, developed by a multidisciplinary panel largely composed of specialists, departed from the previous recommendation to begin addressing screening with average-risk men at age 50 years, stating that “… the age for obtaining a baseline PSA test [in a well-informed patient] has been lowered to 40 years.” The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), which convened a multidisciplinary panel dominated by specialists, also recommended offering average-risk men baseline PSA testing at age 40 years.5

The AUA and NCCN guidelines are intended for health care professionals who counsel patients about screening. Because most people receive preventive services in the primary care setting, the responsibility for implementing these guidelines will fall largely to primary care clinicians. Explaining the benefits and harms of PSA screening entails a potentially time consuming discussion, but often this type of discussion does not take place.6-8 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) currently recommends delivering 35 adult preventive services, for which it found high certainty of moderate or high net benefit.9 Investigators have estimated that it would require 7.4 hours a day for primary care physicians to provide these recommended services.10 Given the limited time in a typically rushed primary care visit, is there sufficient evidence that the net benefits of starting PSA screening at age 40 years justify additional counseling time?

Evidence for Screening at an Earlier Age

The most recent AUA and NCCN guidelines were released after the 2009 publication of 2 large randomized screening trials, the US Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO)11 and the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC).12 In the PLCO, which enrolled men aged 50 to 74 years, screening did not reduce prostate cancer mortality, though screening was widespread among the control group.11 The ERSPC, which had less contamination, reported that screening significantly reduced prostate cancer mortality by 20% among men aged 55 to 69 years.12 The absolute mortality risk reduction with screening, however, was less than 1 per 1,000 men, implying that more than 1,400 men needed to be screened to prevent 1 prostate cancer death in 9 years of follow-up. The small mortality reduction with screening must be weighed against its potential harms, including false-positive tests, overdiagnosis, and treatment complications.13

What do the epidemiology of prostate cancer and these results say about the wisdom of extending PSA screening to men aged 40 years? Of 29,093 US prostate cancer deaths in 2007, nearly 96% occurred among men aged 60 years and older; only about 100 deaths (and just under 3% of incident cases) occurred in men aged 50 years and younger.14 Although we lack direct evidence that a baseline PSA at age 40 years reduces the mortality toll after age 60 years, the ERSPC provides hints to the contrary. While not included in the estimate of screening efficacy, men aged between 50 and 54 years were randomized in the ERSPC. After about 55,000 person-years of follow-up, only 6 prostate cancer deaths had occurred in the screening group and 4 in the control group.12 A decision model study based on ERSPC and population data suggested that the lifetime benefit of beginning routine screening for average-risk men at age 40 rather than age 50 years would be less than 1 fewer prostate-cancer deaths per 1,000 men.15

The remaining arguments for discussing earlier screening rely on weak indirect evidence. The NCCN made a category 2B recommendation (nonuniform consensus based on “lower-level evidence”) based on the rationale that first offering PSA testing at the age of 40 years could prevent “tragic, untimely early deaths.”5 The AUA guideline speculated that being diagnosed in their 40s might cure some additional men destined to die at age 55 to 64 years.4 They reasoned that these younger men might have more “curable” cancer than older men based on observational data showing more favorable tumor characteristics and lower risk for PSA progression after radical prostatectomy.16-18 This contention cannot be proved without controlled trials documenting greater survival with aggressive treatment. Another justification is that the higher specificity of PSA in younger men might reduce the number of prostate biopsies.19 Unfortunately, the common practice of lowering the PSA biopsy threshold for men in their 40s to increase test sensitivity inevitably reduces specificity.20 Finally, the AUA authors assert that obtaining a PSA level at 40 years can establish a baseline for calculating PSA velocity and determining subsequent screening intervals. Analyses of the ERSPC21 and the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial22 data, however, show that measuring PSA velocity does not appreciably improve the predictive value of total PSA.

These arguments supporting prostate screening at 40 years seem weak in the face of epidemiologic reality, decision modeling, and the evidence from the ERSPC. Tellingly, the American Cancer Society, which has often recommended cancer screening when more conservative guidelines have not, recommends in its most recent screening guidelines holding screening discussions before 50 years only with men in high-risk populations (African Americans, positive family history in first-degree relatives).19 In May 2012, the USPSTF issued recommendations against screening any healthy man, regardless of age, race, or family history.23

DEVELOPING GUIDELINES FOR SCREENING AND PREVENTION RELEVANT TO PRIMARY CARE

Viewed narrowly, the 2 specialty guidelines appear to be well-meaning efforts that, although based on untested hypotheses rather than direct evidence, might marginally reduce prostate cancer morbidity and mortality. More broadly, however, to propose screening strategies without any direct evidence of benefit takes us in the wrong direction—away from what has been a generally rising standard of evidence—and toward accepting expert opinion as adequate grounds for recommending procedures that expose many to the risk of harms for the benefit of very few.

A direct consequence of following the AUA and NCCN recommendations would be to enlarge the population being counseled about screening. This outcome would reduce the time available for implementing proven screening and preventive services in primary care. Furthermore, when the legal system argues that such guidelines represent the community standard of care, primary care clinicians who fail to follow them may be exposed to unjustified medical-legal action.24 Notably, the AUA has been aggressively targeting the media, lawmakers, and patients with proscreening messages after the release of the USPSTF recommendation.25

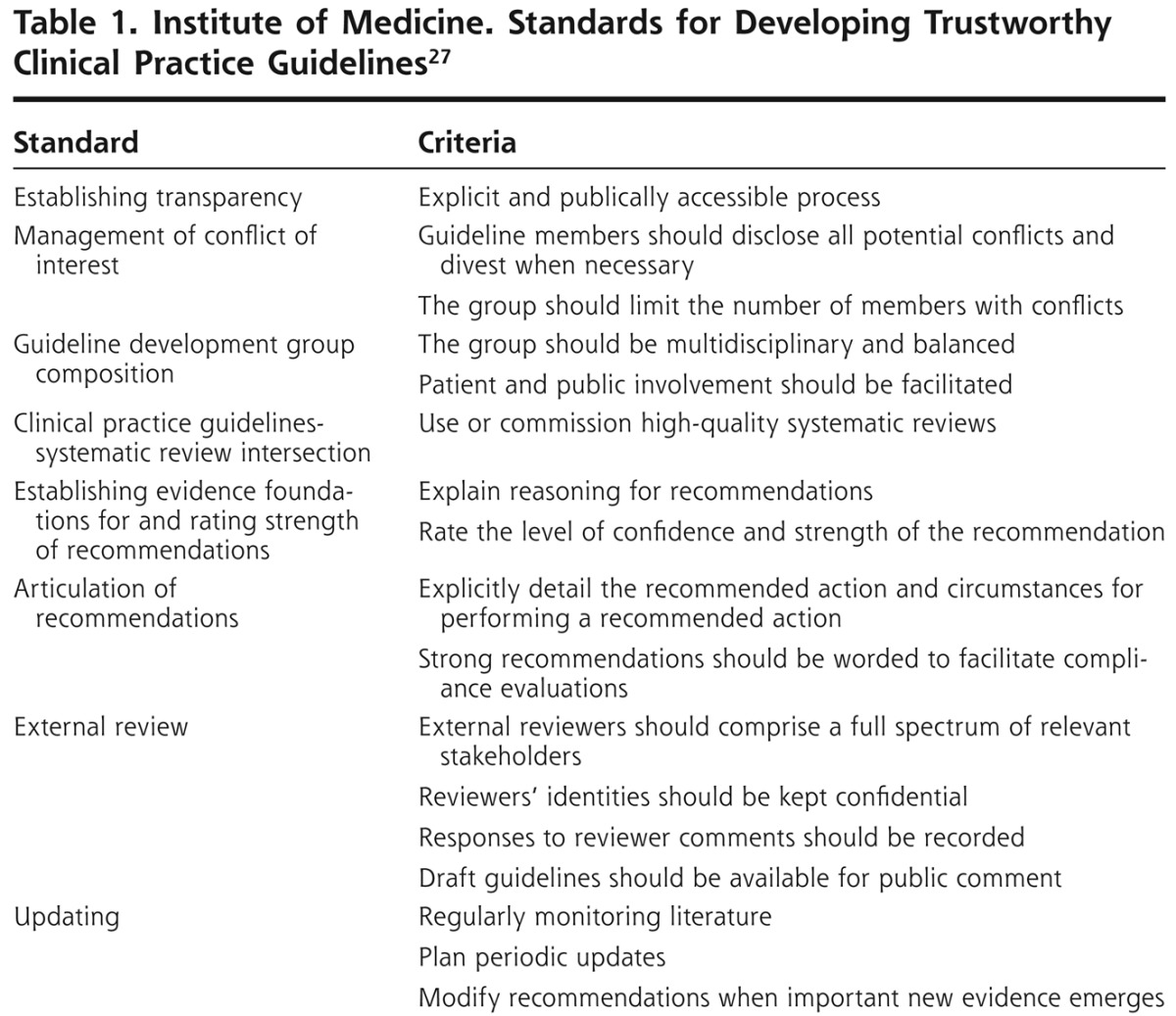

Ideally, groups that develop guidelines will eventually achieve consensus on methodological issues, such as the optimal composition of expert panels, deciding what scientific evidence is strong enough to be admissible, and how to avoid going beyond the evidence when making practice recommendations. To strengthen the guideline development process, generalist clinicians and experts in evidence synthesis should be included on guideline panels and on external review panels. Guidelines should be based on systematic review of the evidence, and not based solely on expert opinion. Widespread use of the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system for categorizing the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations would be an important step in the right direction.26 The Institute of Medicine recently issued performance standards for practice guideline developers (Table 1),27 and the American Cancer Society has committed to following these principles.28

Table 1.

Institute of Medicine. Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines27

Most primary care clinicians lack the time to study guidelines and form independent opinions about them. In an important trend, primary care professional societies have begun to vet specialty guidelines. The American College of Physicians is developing Clinical Guidance Statements29 and the American Academy of Family Physicians30 has implemented evidence-based processes for evaluating guidelines developed by other organizations. The publication of rigorous GRADE and Institute of Medicine standards for developing and assessing the credibility of guidelines along with primary care professional society efforts to filter specialty guidelines are encouraging signs. This support will empower clinicians to choose which guidelines belong in primary care practice, enabling them to focus on providing services with proven effectiveness and value to their patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding support: Dr Hoffman is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

To read or post commentaries in response to this article, see it online at http://www.annfammed.org/content/10/6/568.

References

- 1.Early detection of prostate cancer and use of transrectal ultrasound. In: American Urological Association 1992 Policy Statement Book. Baltimore, MD: American Urological Association; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mettlin C, Jones G, Averette H, Gusberg SB, Murphy GP. Defining and updating the American Cancer Society guidelines for the cancer-related checkup: prostate and endometrial cancers. CA Cancer J Clin. 1993;43(1):42-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for prostate cancer: recommendation and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):915-916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Urological Association Prostate-specific Antigen Best Practice Statement: 2009 Update. http://www.auanet.org/content/guidelines-and-quality-care/clinical-guidelines/main-reports/psa09.pdf

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network Prostate Cancer Early Detection. 2011. [updated 6/1/11]. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate_detection.pdf

- 6.Hoffman RM, Couper MP, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. Prostate cancer screening decisions: results from the National Survey of Medical Decisions (DECISIONS study). Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1611-1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerra CE, Jacobs SE, Holmes JH, Shea JA. Are physicians discussing prostate cancer screening with their patients and why or why not? A pilot study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):901-907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Federman DG, Goyal S, Kamina A, Peduzzi P, Concato J. Informed consent for PSA screening: does it happen? Eff Clin Pract. 1999;2(4):152-157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United States Preventive Services Task Force USPSTF A and B Recommendations. Washington, DC; Health and Human Services; August 2010. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsabrecs.htm [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Østbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003; 93(4):635-641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, III, et al. PLCO Project Team Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1310-1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. ERSPC Investigators Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(13):1320-1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin K, Lipsitz R, Miller T, Janakiraman S, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Benefits and harms of prostate-specific antigen screening for prostate cancer: an evidence update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(3):192-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2007 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2010. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/cancersbyraceandethnicity.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard K, Barratt A, Mann GJ, Patel MI. A model of prostate-specific antigen screening outcomes for low- to high-risk men: information to support informed choices. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1603-1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter HB, Epstein JI, Partin AW. Influence of age and prostate-specific antigen on the chance of curable prostate cancer among men with nonpalpable disease. Urology. 1999;53(1):126-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan MA, Han M, Partin AW, Epstein JI, Walsh PC. Long-term cancer control of radical prostatectomy in men younger than 50 years of age: update 2003. Urology. 2003;62(1):86-91, discussion 91-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith CV, Bauer JJ, Connelly RR, et al. Prostate cancer in men age 50 years or younger: a review of the Department of Defense Center for Prostate Disease Research multicenter prostate cancer database. J Urol. 2000;164(6):1964-1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf AM, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, et al. American Cancer Society Prostate Cancer Advisory Committee American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(2):70-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oesterling JE, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen in a community-based population of healthy men. Establishment of age-specific reference ranges. JAMA. 1993;270(7):860-864 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vickers AJ, Wolters T, Savage CJ, et al. Prostate specific antigen velocity does not aid prostate cancer detection in men with prior negative biopsy. J Urol. 2010;184(3):907-912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vickers AJ, Till C, Tangen CM, Lilja H, Thompson IM. An empirical evaluation of guidelines on prostate-specific antigen velocity in prostate cancer detection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(6):462-469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(2):120-134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merenstein D. A piece of my mind. Winners and losers. JAMA. 2004;291(1):15-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.News Center AUA Speaks Out Against USPSTF Recommendations. Baltimore, MD: American Urological Association; 2011. http://www.auanet.org/content/health-policy/government-relations-and-advocacy/in-the-news/uspstf-psa-recommendations.cfm?acid=8739 296777%7CNE2UroSTAT666&WT.mc_id=NetNews6652 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE Working Group GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924-926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. National Academy of Sciences; 2011. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines-We-Can-Trust.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brawley O, Byers T, Chen A, et al. New American Cancer Society process for creating trustworthy cancer screening guidelines. JAMA. 2011;306(22):2495-2499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qaseem A, Snow V, Owens DK, Shekelle P, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians The development of clinical practice guidelines and guidance statements of the American College of Physicians: summary of methods. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(3):194-199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Academy of Family Physicians AAFP-endorsement of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines developed by external organizations. Washington, DC: American Academy of Family Physicians; 2011. http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/clinical/clinicalrecs/endorsedguidelines.html [Google Scholar]