Abstract

The effects of abscisic acid (ABA) on the accumulation of proteinase inhibitors I (Inh I) and II (Inh II) in young, excised tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) plants were investigated. When supplied to excised plants through the cut stems, 100 μm ABA induced the activation of the ABA-responsive le4 gene. However, under the same conditions of assay, ABA at concentrations of up to 100 μm induced only low levels of proteinase-inhibitor proteins or mRNAs, compared with levels induced by systemin or jasmonic acid over the 24 h following treatment. In addition, ABA only weakly induced the accumulation of mRNAs of several other wound-response proteins. Assays of the ABA concentrations in leaves following wounding indicated that the ABA levels increased preferentially near the wound site, suggesting that ABA may have accumulated because of desiccation. The evidence suggests that ABA is not a component of the wound-inducible signal transduction pathway leading to defense gene activation but is likely involved in the general maintenance of a healthy plant physiology that facilitates a normal wound response.

In response to herbivory or pathogen invasion, tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) plants activate a signal transduction cascade that leads to the synthesis of more than 15 swrps (Bergey et al., 1996). Two of these genes encode the well-characterized swrps, the Inh I and II proteins. An 18-amino acid peptide isolated from tomato leaves, called systemin, is a powerful inducer of swrps when supplied to excised tomato plants (Pearce et al., 1991), and it has been shown to be mobile in the phloem when applied to wounds on tomato leaves. Systemin has been proposed to function as a systemic signal in the activation of defense genes by activating the release of linolenic acid from membrane lipids of target cells (Conconi et al., 1996), presumably through interaction with a membrane receptor. The linolenic acid released is converted to JA through the octadecanoid pathway (Vick and Zimmerman, 1984). Leaves of intact tomato plants accumulate JA 1 to 2 h following wounding (Doares et al., 1995; Conconi et al., 1996), whereas the accumulation of Inh I and II mRNAs following wounding or systemin treatment is usually detectable within 3 to 4 h, peaking within 9 h, and declining thereafter (Graham et al., 1986; McGurl et al., 1992). Proteinase-inhibitor proteins can be detected as early as 4 h after wounding (Graham et al., 1986) and remain at the maximum levels for days, because they are sequestered in the central vacuoles of leaf cells (Shumway et al., 1970, 1976).

The phytohormones auxin, ethylene, and ABA have been shown to exert various effects on the activation of defensive genes. Auxin was shown to inhibit the activation of an Inh II-CAT chimeric gene (Kernan and Thornberg, 1989) in tobacco calli, but the physiological significance of the inhibition is not known. Ethylene alone does not induce proteinase-inhibitor genes (Ryan, 1974; Kernan and Thornberg, 1989) or other wound-inducible genes (Paradies et al., 1980; Mauch et al., 1984), but recent reports suggest that wound-induced ethylene production is required for maximal expression of defense genes (Weiss and Bevan, 1991; O'Donnell et al., 1996) and requires the presence of JA (Xu et al., 1994; O'Donnell et al., 1996).

Evidence has been presented that ABA acts as a primary signal in the systemic wound-signaling cascade in both tomato and potato plants, namely: (a) ABA-deficient potato and tomato mutants fail to accumulate Inh II mRNA in response to wounding when assayed at either 6 (Herde et al., 1996) or 24 h after wounding (Peña-Cortés et al., 1989, 1996); (b) excised leaves of tomato plants accumulated Inh II mRNA when treated with ABA for 24 h (Peña-Cortés et al., 1989, 1993, 1996; Wasternack et al., 1996); and (c) ABA levels increased 2- to 50-fold in tomato leaves 6 h after wounding (Peña-Cortés et al., 1989, 1996; Herde et al., 1996). As a consequence of these observations, a hypothesis evolved that ABA is a key component in the signal transduction cascade leading to defense gene activation (Peña-Cortés et al., 1996; Wasternack and Parthier, 1997).

However, it was reported much earlier (Ryan, 1974) that ABA was unable to induce accumulation of Inh I and II proteins in young tomato plants when it was supplied through their cut stems, a result consistently repeated using young, excised tomato plants (Schaller and Ryan, 1995). Additionally, it has been reported that ABA-treated tobacco calli (Kernan and Thornberg, 1989) and suspension cells (Rickauer et al., 1992) do not accumulate proteinase inhibitors.

To further examine these discrepancies and more clearly understand the role of ABA in the wound response, we have undertaken a detailed study of the effects of ABA on the accumulation of Inh I and II transcripts and proteins in leaves of young tomato plants. These results do not support a role for ABA as a primary component of the signal transduction pathway for defense gene activation in tomato plants in response to wounding or elicitors. Instead, the cumulative evidence suggests that ABA is required to maintain the physiological condition of the plants in a healthy state that allows the wound response to be functional.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Plant Growth Conditions

Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum cv Castlemart) plants were grown in an environment consisting of 17-h days at 28°C under 300 μE m−2 s−1 of light and 7-h nights at 18°C in total darkness. RH was maintained at 80%. Plants were watered at the beginning of each day. All experiments were performed with 15-d-old plants that had two expanding leaves and one small apical leaf.

Systemin was synthesized as described previously (Pearce et al., 1993). JA was prepared from methyl jasmonate as described by Farmer et al. (1992). (±)-ABA was purchased from Sigma and (+)-ABA was a gift from S. Abrams (National Research Council, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada). No differences were observed in any experiment between the effects of (±)-ABA and (+)-ABA. Stocks of each compound were diluted into 10 mm NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 6.5) just prior to use. The ABA-4′-BSA conjugate was a gift from M.K. Walker-Simmons (U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Washington State University, Pullman).

Plant Treatments and Proteinase-Inhibitor Bioassay

Systemin, JA, and ABA were each supplied to excised plants through their cut stems. Pairs of excised plants were placed in 0.6-mL tubes containing 250 μL of buffer alone (10 mm NaH2PO4, pH 6.5) or in buffered solutions of each elicitor or in ABA and incubated for about 30 min at 25°C under 300 μE m−2 s−1 of light. After about 100 μL of the solutions had been taken up (approximately 50 μL/plant), plants were transferred to 20-mL glass vials containing distilled water and enclosed in a Plexiglas box containing a beaker of 10 m NaOH as a CO2 trap. Plants were continuously illuminated under 300 μE m−2 s−1 of light at 25°C for the duration of each experiment. Wounding was accomplished by crushing the leaves with a hemostat three times perpendicular to the midvein on the distal end of the terminal leaflet of the lower leaf of intact plants. The wounded and the unwounded control plants were continuously illuminated under 300 μE m−2 s−1 of light at 28°C and 80% RH for the duration of each experiment. Inh I and II protein content was quantified in expressed leaf juice by radial immunodiffusion (Ryan, 1967; Trautman et al., 1971) using pure Inh I and II as the standards.

RNA Gel-Blot Analysis

Leaf tissue was frozen in liquid N2, immediately ground to a fine powder in the presence of phenol, and stored at −80°C until tissues from all times were collected. Total RNA was isolated and fractionated by electrophoresis in a formaldehyde-agarose gel (12 μg per lane) as described by McGurl et al. (1995). Gels were stained with ethidium bromide to ensure even loading of RNA. After fractionation, RNA was blotted onto nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell) and identified with appropriately labeled probes. All cDNAs were labeled with a T7 Quickprime Kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following tomato cDNAs were used as probes: Inh I (Graham et al., 1985a), Inh II (Graham et al., 1985b), prosystemin (McGurl et al., 1992), cathepsin D inhibitor (Schaller et al., 1995), Cys proteinase inhibitor (gift from D. Bergey, Washington State University, Pullman), polyphenol oxidase (Constabel et al., 1995), and le4 (gift from E.A. Bray, University of California, Riverside; Cohen and Bray, 1990). Ubiquitin cDNA was a gift from A. Conconi (Washington State University, Pullman). Nitrocellulose filters were prehybridized for 4 h at 65°C in 5× SSC (1× SSC is 150 mm sodium chloride and 15 mm sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 1% SDS, 5× Denhardt's solution (1× Denhardt's solution is 0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% PVP, and 0.02% BSA), and 100 μg/mL denatured herring sperm DNA. Hybridization was performed for at least 12 h at 65°C using the same buffer containing 2 ng/mL radiolabeled probe. Blots were washed three times for 15 min in 0.5× SSC and 1% SDS at 65°C and exposed to Kodak XAR film at −80°C with an intensifying screen.

Extraction and Quantification of ABA

At intervals, leaf tissue was frozen in liquid N2, weighed, lyophilized, and weighed dry. ABA was extracted as follows by a procedure adapted from Walker-Simmons (1987). Powdered tissue was suspended in methanol containing 0.5 g/L citric acid monohydrate and 100 mg/L butylated hydroxytoluene at a ratio of 10 mg of dry tissue per 0.1 mL of methanol solution. Suspensions were stirred in sealed tubes for 36 h at 4°C in the dark and centrifuged at 1500g. The supernatants were recovered, adjusted to 70% methanol using a 62.5% solution of the extracting methanol, and passed through a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters). The eluates were dried, resuspended in TBS, diluted as described (Walker-Simmons, 1987), and stored at 4°C in the dark until assayed. ABA was assayed as described previously (Walker-Simmons, 1987) using an indirect ELISA method with a rabbit monoclonal antibody prepared against cis, trans (+)-ABA (Idetek, Inc., San Bruno, CA).

Two types of controls were performed to validate the results of this technique. First, [3H]ABA was added to methanol-suspended tissue, and recovery after elution from the Sep-Pak C18 cartridge was determined by liquid-scintillation counting. Second, a known amount of (+)-ABA was added to selected methanol-suspended samples. The ELISA method was used to measure the amount of ABA in these spiked samples. Recovery was then expressed as the difference between the spiked and original samples divided by the amount of (+)-ABA added. In both cases recovery was found to be ≥ 99%. Additionally, the accuracy of the indirect ELISA method was verified previously by HPLC and GC-MS (Walker-Simmons, 1987; Munns and King, 1988).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Accumulation of Proteinase-Inhibitor Proteins and mRNAs in Plants Treated with ABA

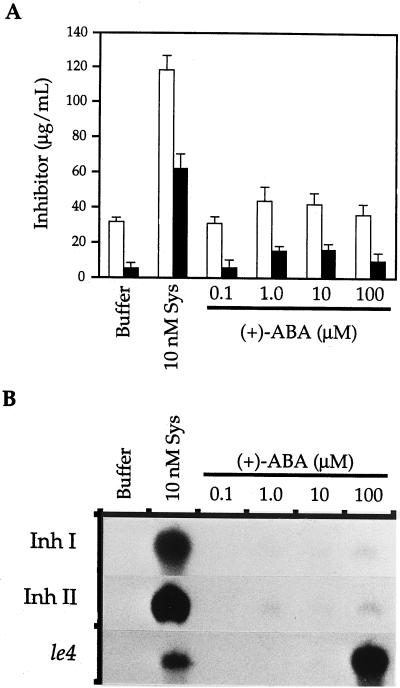

ABA in buffer was supplied to young tomato plants at various concentrations and leaves were analyzed 6 h later for the accumulation of Inh I and II mRNA or 24 h later for the accumulation of Inh I and II protein. Figure 1A shows that plants continuously supplied with systemin accumulated high levels of Inh I and II proteins, whereas plants continuously supplied with 100 μm ABA accumulated only slightly more Inh I and II protein than the control plants that were supplied with buffer alone. Northern blots of identically treated plants (Fig. 1B) revealed that ABA only weakly induced the accumulation of mRNAs encoding Inh I and II 6 h after treatment compared with induction by systemin. To ensure that ABA was taken up by plants, the cDNA of an ABA-inducible gene, le4 (Cohen and Bray, 1990), was used as a probe in northern blotting. Cohen and Bray (1990) previously reported that 100 μm ABA is the lowest concentration that results in a strong induction of the le4 gene in tomato leaves. Consistent with their observation, Figure 1B shows that sufficient ABA is taken up by young plants supplied with 100 μm ABA to strongly induce the le4 gene. For this reason, all subsequent experiments were performed with ABA at this concentration.

Figure 1.

The effects of systemin (Sys) and ABA on the accumulation of Inh I and II mRNAs and proteins in young tomato plants. Excised plants were continuously supplied with buffer or with buffer plus systemin or ABA as indicated. A, Expressed leaf juice was assayed for Inh I (white bars) and II (black bars) protein content by radial immunodiffusion after 24 h of treatment with systemin and ABA. The means ± se of six plants per treatment were plotted. B, After 6 h, leaves from six plants per treatment were frozen for mRNA analysis by northern blotting and hybridization with radiolabeled probes prepared from cDNAs encoding Inh I, Inh II, and le4.

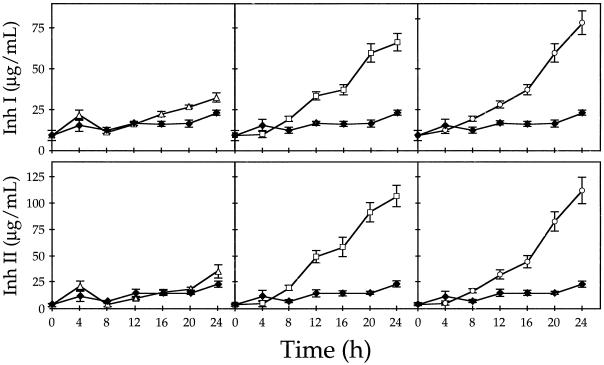

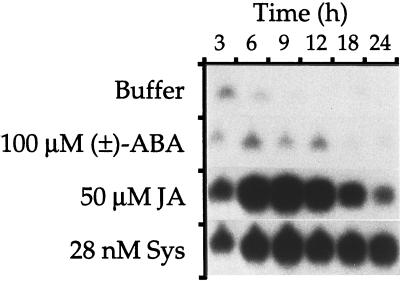

The time course of the accumulation of Inh I and II proteins in response to ABA was compared with the accumulation in response to systemin and JA (Fig. 2). Expressed leaf juice from individual plants treated with ABA was assayed for Inh I and II content at 4-h intervals during a 24-h period. As previously found (Farmer and Ryan, 1990; Pearce et al., 1991; Schaller et al., 1995; Schaller and Ryan, 1996), treatment of excised plants with either systemin or JA for 30 min resulted in a marked accumulation of inhibitor proteins with time (Fig. 2). However, supplying excised plants with ABA throughout the incubation time only weakly induced inhibitor protein accumulation (Fig. 2), and this level remained low even when the incubation time was extended to 48 h (data not shown). Likewise, ABA treatment induced only a weak accumulation of Inh II transcript compared with the responses induced by systemin and JA during the 24 h following treatment (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with reports that show ABA does not strongly induce Inh I and II genes in tomato (Ryan, 1974; Schaller and Ryan, 1995) and tobacco (Kernan and Thornberg, 1989; Rickauer et al., 1992).

Figure 2.

Time course of Inh I and II protein accumulation in young tomato plants supplied with buffer (♦) or with buffer plus ABA (100 μm, ▵), JA (40 μm, □), or systemin (28 nm, ○). At 4-h intervals, leaf juice was expressed and assayed for proteinase inhibitors by radial immunodiffusion. Each data point represents the average of 14 plants ± se.

Figure 3.

Time course of Inh II mRNA accumulation in young tomato plants in response to ABA, JA, and systemin (Sys). The plants were supplied with buffer or with buffer plus ABA, JA, or systemin as shown. At the indicated times, leaves from six plants per treatment were frozen for RNA extraction and assayed by northern blotting. Three independent experiments were performed and results from one representative experiment are shown.

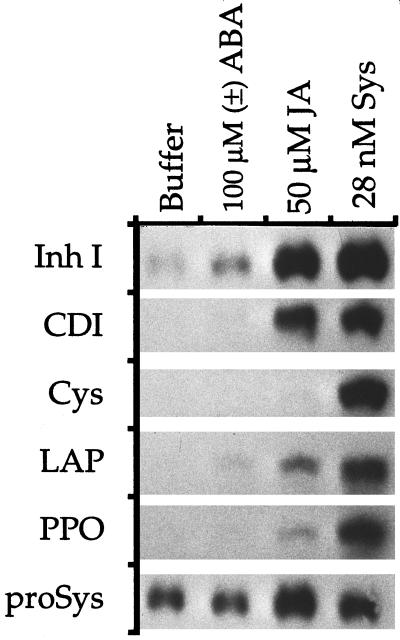

Effects of ABA on the Accumulation of mRNAs Encoding Other Defense Proteins

The ABA inducibilities of several other swrp genes were also tested by northern blotting. Since the largest increases in Inh II accumulation in response to ABA relative to buffer controls were observed at 12 h after treatment (Fig. 3), this time was selected to test the ABA inducibility of other swrps. All six of the swrp mRNAs were strongly induced by systemin, whereas all but the Cys proteinase inhibitor was induced to measurable levels by JA. In response to ABA treatment, very low levels of mRNAs encoding Inh I, cathepsin D inhibitor, and Leu aminopeptidase were observed when compared with plants supplied with buffer alone (Fig. 4). Polyphenol oxidase mRNA accumulation was negligible, whereas Cys proteinase-inhibitor mRNA accumulation was not observed upon ABA treatment (Fig. 4). Therefore, several wound-responsive genes of tomato, which are strongly activated by primary signals, including chitosan (Walker-Simmons and Ryan, 1984, 1986), oligosaccharides (Bishop et al., 1984; Walker-Simmons and Ryan, 1986), and systemin (Pearce et al., 1991, 1993; McGurl et al., 1992; Constabel et al., 1995; Schaller et al., 1995), and the octadecanoid pathway components linolenic acid (Farmer and Ryan, 1992; Peña-Cortés et al., 1996), phytodienoic acid (Farmer and Ryan, 1992), and JA (Farmer and Ryan, 1992; Peña-Cortés et al., 1996; Wasternack et al., 1996), are only weakly activated by ABA or not activated at all.

Figure 4.

Induction of genes encoding several swrps in young tomato plants in response to buffer or to buffer plus ABA, JA, or systemin (Sys). After 12 h, leaves from six plants per treatment were frozen for RNA extraction. mRNA detection was achieved by northern blotting, and hybridization was achieved with radiolabeled probes prepared from cDNAs encoding Inh I, cathepsin D inhibitor (CDI), Cys proteinase inhibitor (Cys), Leu amino peptidase (LAP), polyphenol oxidase (PPO), or prosystemin (proSys). Three independent experiments were performed, which were in full agreement. Results from one representative experiment are shown.

Accumulation of ABA in Leaves in Response to Wounding

A model for the systemic wound-signaling cascade was originally proposed in which wounding and elicitors activated defense genes via the octadecanoid pathway (Farmer and Ryan, 1992; Doares et al., 1995). This model was modified to include ABA accumulation as an obligatory component between systemin and JA (Peña-Cortés et al., 1996; Wasternack and Parthier, 1997). This modification was supported by several reports, all of which indicated that ABA was both necessary and sufficient for activating defense genes (Peña-Cortés et al., 1989, 1993, 1996; Herde et al., 1996; Wasternack et al., 1996). The modified model also predicted that ABA accumulates in response to wounding and that this accumulation parallels or slightly precedes the wound-induced accumulation of JA. This was supported by data showing that ABA accumulated in intact tomato plants 6 h after wounding (Herde et al., 1996). However, since the accumulation of JA in intact tomato plants peaks approximately 1 h after wounding and returns to the original level several hours later (Doares et al., 1995; Conconi et al., 1996), it was unclear how the accumulation of ABA at 6 h was exerting a direct effect on gene activation occurring at 3 h following wounding.

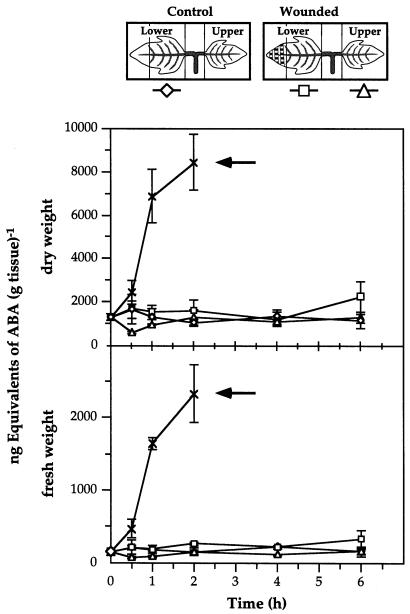

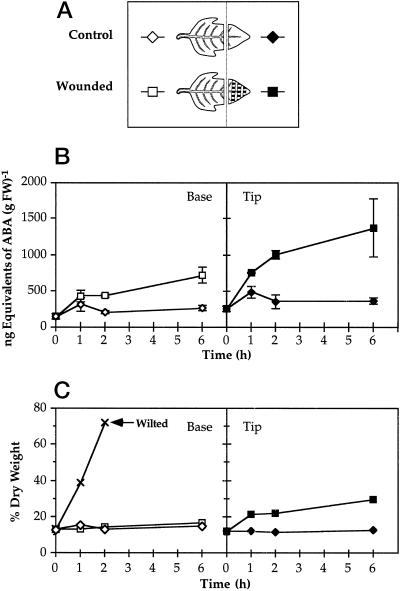

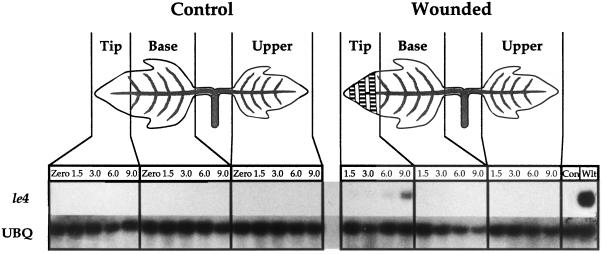

To clarify the relationship between ABA and JA accumulation, we determined the ABA content of tomato leaves during the first 6 h following wounding. The levels of ABA, relative to fresh or to dry weight in both the wounded and systemic leaves, remained low and fell within the margins of experimental error, although about a 2-fold increase in ABA was observed in wounded leaves after 6 h (Fig. 5). In contrast, a 9-fold accumulation of ABA relative to fresh weight occurred after 1 h in leaves of plants that were allowed to wilt (Fig. 5). Since water loss through the wound site may result in localized desiccation, tissue collected from wounded leaves was at least 0.5 cm from the site of injury, as illustrated in Figure 5. When the accumulation of ABA in tissue within 0.5 cm of the wound site (Fig. 6A) was quantified, the level of ABA increased 4-fold after 6 h over unwounded tissue, compared with only a 2-fold accumulation of ABA in the undamaged portion of the wounded leaflet over unwounded controls (Fig. 6B). Under these experimental conditions, the water loss from wounded and unwounded leaves was determined during the time course after wounding and expressed as the dry weight percentage of fresh weight (Fig. 6C). Significant water loss was observed only in the tissue within 0.5 cm of the wound site, the same tissue that displayed a 4-fold increase in the amount of ABA. Northern analysis of the accumulation of le4 mRNA in leaves also indicated that this ABA-responsive gene is activated only near the wound site (Fig. 7). Therefore, the accumulation of ABA in wounded leaves appears to result from the localized dehydration that follows wounding.

Figure 5.

Time course of the accumulation of ABA in young tomato plants in response to wounding and wilting with respect to tissue dry (top) and fresh (bottom) weight. Leaves or leaf subsections were collected at the indicated times as illustrated in the sketch. At each interval, the leaves of four plants per treatment were individually assayed for ABA content by an indirect ELISA method and each assay was performed in triplicate. The means ± se are plotted. Wilting was performed by exposing excised lower leaves to air at 28°C and 80% RH. The hatch marks on the wounded leaflet represent the locations of hemostat-crushed tissue. Arrows indicate wilted leaves.

Figure 6.

Time course of the accumulation of ABA and corresponding water loss in leaves of young tomato plants in response to wounding. A, The illustration shows the location of tissues tested with respect to the site of injury. The hatch marks on the wounded leaflet represent the locations of hemostat-crushed tissue. B, At each interval, leaves from six plants per treatment were assayed in pairs for ABA content by an indirect ELISA method, and each assay was performed in triplicate. The means ± se are plotted. C, Water loss from tissues used in B was monitored by plotting the dry weight percentage of fresh weight (FW) over time. Wilting was performed as described in Figure 5.

Figure 7.

Time-course accumulation of le4 mRNA upon wounding. Six leaves per treatment were collected at the indicated times and divided into sections as illustrated. Sectioned tissue was frozen for RNA analysis by northern blotting and hybridization with radiolabeled probes prepared from cDNAs encoding le4 and ubiquitin (UBQ). Two independent experiments were performed and results from one representative experiment are shown. The hatch marks on the wounded leaflet represent the locations of hemostat-crushed tissue. Con, Leaves of intact, untreated plants; Wlt, excised leaves collected 4 h after being allowed to wilt to 88% of their original fresh weight.

cv Castlemart was originally selected for studies of defense gene activation because it provided the greatest wound inducibility of Inh I and II among the several varieties that were tested. Previous investigations of the involvement of ABA in defense gene activation have used cv Moneymaker and its derived ABA-deficient mutant sitiens (Peña-Cortés et al., 1989, 1996). We obtained similar results using cv Moneymaker and will report the results elsewhere (G.F. Birkenmeier and C.A. Ryan, unpublished data).

In summary, our experiments with tomato indicate (a) unlike all other known primary signals, ABA does not strongly induce systemic wound-response genes; (b) accumulation of ABA in response to wounding is enhanced in tissue within 0.5 cm of the site of injury and may be due to water loss; and (c) there is no detectable ABA accumulation in distal leaves. The failure of the ABA-deficient tomato mutants to activate defensive genes upon wounding (Peña-Cortés et al., 1989, 1996; Herde et al., 1996) indicates that the presence of physiological levels of ABA may be required to potentiate the wound-signaling cascade, but the specific manner in which this may occur is unknown. However, since ABA does not behave as a primary component of the systemic wound-signal transduction cascade in tomato, its role appears to be in maintaining the physiological condition of the plants so that the wound response is functional.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sue Vogtman and Thom Koehler for growing and maintaining the plants used in this study, Dr. M.K. Walker-Simmons (U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Washington State University, Pullman) for her help and guidance with assaying ABA, and Dr. Elizabeth Bray (University of California, Riverside) for her generous gift of the le4 cDNA.

Abbreviations:

- Inh I and II

proteinase inhibitors I and II, respectively

- JA

jasmonic acid

- swrps

systemic wound-response proteins

Footnotes

This research was supported in part by the Washington State University College of Agriculture (project no. 1791), the National Science Foundation (grant nos. IBN-9184542 and IBN-9117795) to C.A.R., and a fellowship from the Charlotte Y. Martin Foundation to G.F.B.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bergey DR, Howe GA, Ryan CA. Polypeptide signaling for plant defensive genes exhibits analogies to defense signaling in animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12053–12058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop PD, Pearce G, Bryant JE, Ryan CA. Isolation and characterization of the proteinase inhibitor-inducing factor from tomato leaves: identity and activity of poly- and oligogalacturonide fragments. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13172–13176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A, Bray EA. Characterization of three mRNAs that accumulate in wilted tomato leaves in response to elevated levels of endogenous abscisic acid. Planta. 1990;182:27–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00239979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conconi A, Miquel M, Browse JA, Ryan CA. Intracellular levels of free linolenic and linoleic acids increase in tomato leaves in response to wounding. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:797–803. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.3.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constabel CP, Bergey DR, Ryan CA. Systemin activates synthesis of wound-inducible tomato leaf polyphenol oxidase via the octadecanoid defense signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:407–411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doares SH, Syrovets T, Weiler EW, Ryan CA. Oligogalacturonides and chitosan activate plant defensive genes through the octadecanoid pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4095–4098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EE, Johnson RR, Ryan CA. Regulation of proteinase inhibitor genes by methyl jasmonate and jasmonic acid. Plant Physiol. 1992;98:995–1002. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.3.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EE, Ryan CA. Interplant communication: airborne methyl jasmonate induces synthesis of proteinase inhibitors in plant leaves. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7713–7716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EE, Ryan CA. Octadecanoid precursors of jasmonic acid activate the synthesis of wound-inducible proteinase inhibitors. Plant Cell. 1992;4:129–134. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JS, Hall G, Pearce G, Ryan CA. Regulation of synthesis of proteinase inhibitors I and II mRNAs in leaves of wounded tomato plants. Planta. 1986;169:399–405. doi: 10.1007/BF00392137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JS, Pearce G, Merryweather J, Titani K, Ericsson L, Ryan CA. Wound-induced proteinase inhibitors from tomato leaves. I. The cDNA-deduced primary structure of pre-inhibitor I and its post-translational processing. J Biol Chem. 1985a;260:6555–6560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JS, Pearce G, Merryweather J, Titani K, Ericsson L, Ryan CA. Wound-induced proteinase inhibitors from tomato leaves. II. The cDNA-deduced primary structure of pre-inhibitor II. J Biol Chem. 1985b;260:6561–6564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herde O, Atzorn R, Fisahn J, Wasternack C, Willmitzer L, Peña-Cortés H. Localized wounding by heat initiates the accumulation of proteinase inhibitor II in abscisic acid-deficient plants by triggering jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:853–860. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.2.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernan A, Thornberg RW. Auxin levels regulate the expression of a wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor II-chloram-phenicol acetyl transferase gene fusion invitro and in vivo. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:73–78. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauch F, Hadwiger LA, Boller T. Ethylene. Symptom, not signal for the induction of chitinase and β-1,3-glucanase in pea pods by pathogens and elicitors. Plant Physiol. 1984;76:607–611. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.3.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurl B, Mukherjee S, Kahn M, Ryan CA. Characterization of two proteinase inhibitor (ATI) cDNAs from alfalfa leaves (Medicago sativa var. Vernema): the expression of ATI genes in response to wounding and soil microorganisms. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:995–1001. doi: 10.1007/BF00037026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurl B, Pearce G, Orozco-Cardenas M, Ryan CA. Structure, expression, and antisense inhibition of the systemin precursor gene. Science. 1992;255:1570–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.1549783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R, King RW. Abscisic acid is not the only stomatal inhibitor in the transpiration stream of wheat plants. Plant Physiol. 1988;88:703–708. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.3.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell PJ, Calvert C, Atzorn R, Wasternack C, Leyser HMO, Bowles DJ. Ethylene as a signal mediating the wound response of tomato plants. Science. 1996;274:1914–1917. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies I, Konze JR, Elstner EF. Ethylene. Indicator but not inducer of phytoalexin synthesis in soybean. Plant Physiol. 1980;66:1106–1109. doi: 10.1104/pp.66.6.1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce G, Johnson S, Ryan CA. Structure-activity of deleted substituted systemin, an 18-amino acid polypeptide inducer of plant defensive genes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce G, Strydom D, Johnson S, Ryan CA. A polypeptide from tomato leaves induces wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor proteins. Science. 1991;253:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.253.5022.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Cortés H, Albrecht T, Prat S, Weiler EW, Willmitzer L. Aspirin prevents wound-induced gene expression in tomato leaves by blocking jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Planta. 1993;191:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Cortés H, Prat S, Atzorn R, Wasternack C, Willmitzer L. Abscisic acid-deficient plants do not accumulate proteinase inhibitor II following systemin treatment. Planta. 1996;198:447–451. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Cortés H, Sánchez-Serrano JJ, Mertens R, Willmitzer L, Prat S. Abscisic acid is involved in the wound-induced expression of the proteinase inhibitor II gene in potato and tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9851–9855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickauer M, Bottin A, Esquerre-Tugaye M. Regulation of proteinase inhibitor production in tobacco cells by fungal elicitors, hormonal factors and methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1992;30:579–584. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CA. Quantitative determination of soluble cellular proteins by radial diffusion in agar gels containing antibodies. Anal Biochem. 1967;19:434–440. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(67)90233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. Assay and biochemical properties of the proteinase inhibitor-inducing factor, a wound hormone. Plant Physiol. 1974;54:328–332. doi: 10.1104/pp.54.3.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller A, Bergey DR, Ryan CA. Induction of wound response genes in tomato leaves by bestatin, an inhibitor of aminopeptidases. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1893–1898. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.11.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller A, Ryan CA. Systemin—a polypeptide defense signal in plants. Bioessays. 1995;18:27–33. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller A, Ryan CA. Molecular cloning of a tomato leaf cDNA encoding an aspartic protease, a systemic wound response protein. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31:1073–1077. doi: 10.1007/BF00040725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway LK, Rancour JM, Ryan CA. Vacuolar protein bodies in tomato leaf cells and their relationship to storage of chymotrypsin inhibitor I protein. Planta. 1970;93:1–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00387647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumway LK, Vie Yang V, Ryan CA. Evidence for the presence of proteinase inhibitor I in vacuolar protein bodies of plant cells. Planta. 1976;129:161–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00390023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautman R, Cowan KM, Wagner GG. Data processing for immunodiffusion. Immunochemistry. 1971;8:901–906. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(71)90429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vick BA, Zimmerman DC. Biosynthesis of jasmonic acid by several plant species. Plant Physiol. 1984;75:458–461. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.2.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Simmons M. ABA levels and sensitivity in developing wheat embryos of sprouting resistant and susceptible cultivars. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:61–66. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Simmons M, Ryan CA. Proteinase inhibitor synthesis in tomato leaves. Induction by chitosan oligomers and chemically modified chitosan and chitin. Plant Physiol. 1984;76:787–790. doi: 10.1104/pp.76.3.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker-Simmons M, Ryan CA. Proteinase inhibitor I accumulation in tomato suspension cultures. Induction by plant and fungal cell wall fragments and an extracellular polysaccharide secreted into the medium. Plant Physiol. 1986;80:68–71. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Atzorn R, Peña-Cortés H, Parthier B. Alteration of gene expression by jasmonate and ABA in tobacco and tomato. J Plant Physiol. 1996;147:503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C, Parthier B. Jasmonate-signaled plant gene expression. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss C, Bevan M. Ethylene and a wound signal modulate local and systemic transcription of win2 genes in transgenic potato plants. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:943–951. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Chang PL, Liu D, Narasimhan ML, Raghothama KG, Hasegawa PM, Bressan RA. Plant defense genes are synergistically induced by ethylene and methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1077–1085. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.8.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]