Abstract

The human frontal lobe is critical for cognitive function in the healthy brain. Many psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are associated with apparent mitochondrial dysfunction and bioenergetic abnormalities in the frontal lobe. Therefore, measuring cerebral bioenergetics associated with creatine kinase (CK) and ATP synthase reactions could provide crucial information regarding the underlying molecular mechanisms associated with psychiatric disorders. In this study, the unidirectional forward chemical exchange metabolic fluxes of creatine kinase and ATP synthase reactions as well as reverse chemical exchange metabolic flux associated with ATP hydrolysis were determined at 4T by 31P magnetization transfer. The current experiments indicate that the kinetic network of PCr↔ATP↔Pi can be measured reliably in the human frontal lobe at 4T, which will enable detailed in vivo characterization of bioenergetic abnormalities in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), bioenergetics, frontal lobe, 31P MRS, magnetization transfer

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are common and severe brain disorders with significant negative impact on the affected individual and on society. Although the exact etiology of these disorders is unknown, numerous in vivo studies have demonstrated that abnormalities in neural activity and energy metabolism exist in persons with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (1–3). Using 1H MRS, our group recently demonstrated that total creatine (tCr) concentrations are reduced in the anterior cingulate cortex and parieto-occipital cortex of patients with schizophrenia (4). Postmortem studies also have identified abnormalities in mitochondrial structure (5), dysfunctional oxidative phosphorylation (6), and altered mitochondria related gene expression(7) in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Energy production, which largely occurs in mitochondria, is critical for many metabolic and intracellular signaling pathways and for glutamate-glutamine cycling during neurotransmission. Thus, it has great bearing on brain function, including emotional, cognitive and sensorimotor processes. Therefore, quantifying energy metabolism rates in vivo may provide crucial information on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and help identify novel targets for drug development.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a high-energy phosphate (HEP) compound, is the universal “energy currency” in living cells (8). It is required to restore cell membrane ion gradients and for most signaling pathways, including intracellular and intercellular signaling. The majority of ATP is formed from adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and inorganic phosphate (Pi) in the mitochondria through oxidative phosphorylation catalyzed by the enzyme ATP synthase (ATPsyn) (9). This biochemical process is also coupled to the creatine kinase (CK) reaction linking to phosphocreatine (PCr), which acts as a HEP reservoir and carrier for transferring energy from the mitochondria to the sites of utilization in the cytosol, therefore maintaining a stable ATP level in living cells (10,11). These chemical exchange reactions of PCr↔ATP↔Pi play a fundamental role in cerebral bioenergetics and brain function. Cerebral ATP metabolic rates can be determined explicitly and noninvasively by the in vivo 31P magnetization transfer (MT) approach which directly reflects mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation(12–15).

Although abnormal mitochondrial function in the frontal lobe appears to be associated with psychiatric diseases, CK and ATPsyn reaction rates have not previously been measured in this region in vivo. In the current study, we explored whether ATP synthesis rates catalyzed by CK and ATPsyn can be separately determined in the human frontal lobe at 4T scanner.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Human subjects and MR imaging

Seventeen healthy human subjects without any psychiatric or substance use disorders (10 males and 7 females, 24.7±4.3 years old) were recruited for these studies. All subjects provided informed consent and the study procedure was approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Review Board. The MR experiments were conducted using a 4T whole-body scanner interfaced with a Varian INOVA console. Brain anatomic imaging and shimming was conducted by a birdcage volume coil. After global shimming, a 6.5×6.5×5.0 cm3 voxel within the main sensitivity region of the 7-cm 31P surface coil applied over the frontal lobe was manually shimmed to further minimize magnetic field inhomogeneity (B0).

In vivo 31P experiments

All the 31P signal was acquired from the sensitivity region of the surface coil except that signal from extra-cranial muscles was eliminated by outer-volume saturation (12). The 31P MT pulse sequence has been described in previous papers, with modification of NMR parameters for the current study. Briefly, a pulse train constructed with multiple hyperbolic Sech pulses with varied RF pulse amplitudes according to the BISTRO scheme (16) was used to saturate selectively the resonance peak of γ-ATP (one-site saturation for measurement of CK and ATPsyn reaction rate constants) and both resonances of PCr and Pi (two-site saturation for measurement of the chemical reaction rate constant of ATP hydrolysis to PCr and Pi) (17), in separate experiments. Note that the resonance peak at −2.5 ppm is composed of signal from all nucleoside triphosphates (including ATP, Guanosine-5′-triphosphate and others) and is sometimes referred to as the γ-NTP peak, however, the vast majority of the signal in this peak arises from ATP and therefore we will refer to it as the γ-ATP peak in this study.

Saturation time was controlled by varying the cycling number of the BISTRO pulse train. For the one-site saturation experiment, a hyperbolic Sech pulse (pulse width = 55 ms, frequency-selective bandwidth = 200 Hz) was applied and saturation time from 0 to 12.73 s was used. For the two-site saturation experiment, the RF pulse described above was modified to saturate PCr and Pi simultaneously. The saturation RF pulse with a single saturation frequency band was replaced by a hyperbolic Sech RF pulse (pulse width = 100 ms) with two identical saturation bands (140-Hz width for each) separated by 360-Hz between the band centers, which equals the chemical shift difference (in Hz) between the PCr and Pi resonance peaks at 4.0 Tesla. Saturation time was varied from 0 to 11.89 s.

The offset RF saturation effect caused by the imperfection of the frequency profile of BISTRO pulse trains was experimentally determined by measuring and comparing the magnetization of chemically non-exchangeable phosphate metabolites acquired in the presence of the BISTRO saturation pulse train at a selected saturation frequency and in the absence of the saturation pulse train. This measurement was performed with varied saturation times. The ratios of these two magnetizations provided the correction factors as a function of the saturation time. The correction factors were applied in the data processing of the saturated in vivo 31P spectra in this work.

A 200-μs hard RF pulse was used to excite the phosphate spins and its flip angle (nominal 90°) was adjusted to achieve an optimal NMR signal from the human frontal lobe. In vivo 31P spectra were acquired using the following acquisition parameters: 5000 Hz spectral width, 1024 complex data points, 32 and 24 signal averages for the one-site and two-site saturation experiment, respectively. All in vivo 31P spectra were acquired with a 14-s repetition time (TR) at the approximately fully relaxed condition. The specific absorption rate (SAR) was maintained below limit of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Due to the relatively long measurement time needed for conducting each in vivo 31P MT experiment, 17 subjects were divided into three sub-groups: (i) one-site saturation (n=9), (ii) two-site saturation (n=8, 6 of 8 overlapped with (i)), and (iii) the experiments for determining the offset RF saturation effect (n=6). The total measurement time for each experimental session was ≤ 70 min.

In order to delineate the 31P sensitivity region of the surface coil used in the current experiment setup, 1D profiles of Pi signal along three orthogonal dimensions were acquired from a phantom (14-cm diameter cylindrical bottle) with in-organic phosphate solution ([Pi] = 0.6 M and pH = 7.1).

Spectrum processing

The 31P spectra were analyzed in the time domain using the AMARES algorithm within jMRUI-software package (18). In this study, the initial 4 points of FID (the first 0.9 ms of the signal) were truncated to remove the broad component. Eight resonance peaks (PE: phosphoethanolamine; Pi: inorganic phosphate; GPC: glycerophosphocholine; GPE: glycerophosphoethanolamine; PCr: phosphocreatine; and three adenosine triphosphates: α-, β-, γ-ATP) were included in the basis set. The starting values of spectral resonances positions referred to PCr and line widths were initialed in the spectra fitting. The chemical shift of the PCr resonance peak was assigned to 0 ppm. The spectra base line and zero and first order phase were corrected.

Chemical exchange rates measured by progressive saturation transfer

The chemical exchange reactions among PCr, ATP and Pi were simply illustrated as the Eq. [1], where kf and kr are the pseudo first-order forward and reverse rate constant, respectively. For the experiments using progressive saturation on the γ-ATP resonance, the magnetizations of PCr or Pi are governed by the Eqs. [2a] and [2b](19).

| (1) |

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

Where Ms and M0 are the magnetization of PCr, or Pi at saturation time (t) and Boltzmann thermal equilibrium condition, respectively; k is the pseudo first-order forward rate constant involving ATP production via the CK or ATPsyn reaction. and are the intrinsic and apparent spin-lattice relaxation times of PCr or Pi, respectively. Therefore kf of CK and ATPsyn reactions, and of PCr and Pi can be determined by fitting the experimental data to a single exponential decay according to Eqs. [2a] and [2b] (14). Similarly, Eqs. [2a] and [2b] also can be used for the two-site (PCr and Pi) saturation experiment (17) except that M refers to magnetizations of γ-ATP. In this case, k is the pseudo first-order reverse rate constant ( ) for ATP utilization via the ATPase and reverse CK reactions and

and are the intrinsic and apparent spin-lattice relaxation time of γ-ATP, respectively.

Lastly, the chemical reaction flux (F) can be calculated by

| (3) |

Where, k is forward or reverse chemical exchange constant as described above (s−1) and [M] is the metabolite concentration (μmol/ml) of PCr, Pi and ATP, respectively, according to the one-site or two-site saturation experiment. The chemical reaction fluxes were converted to μmol/g/min assuming brain tissue density of 1.1g/ml.

All data are reported as means +/− one standard deviation.

RESULTS

Phosphate metabolite concentrations and magnetization transfer results

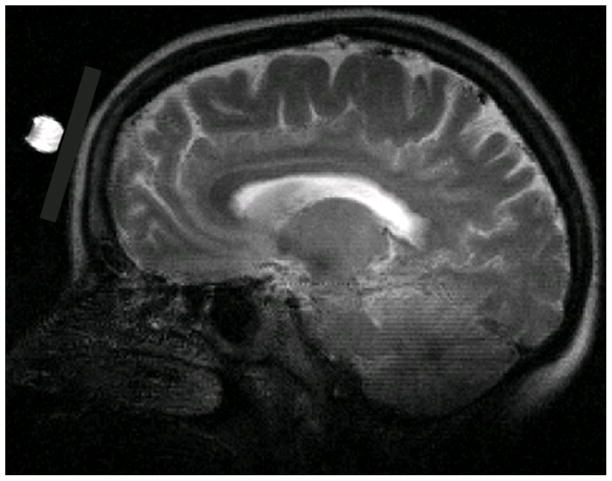

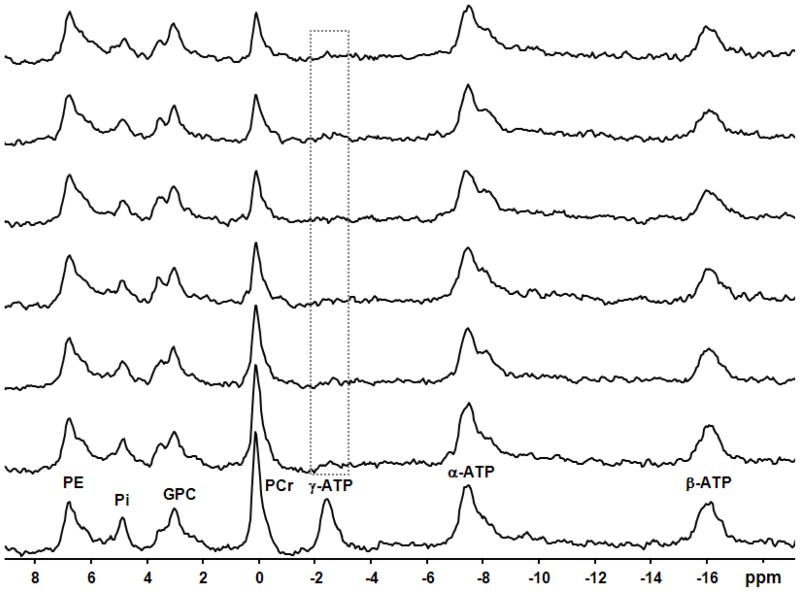

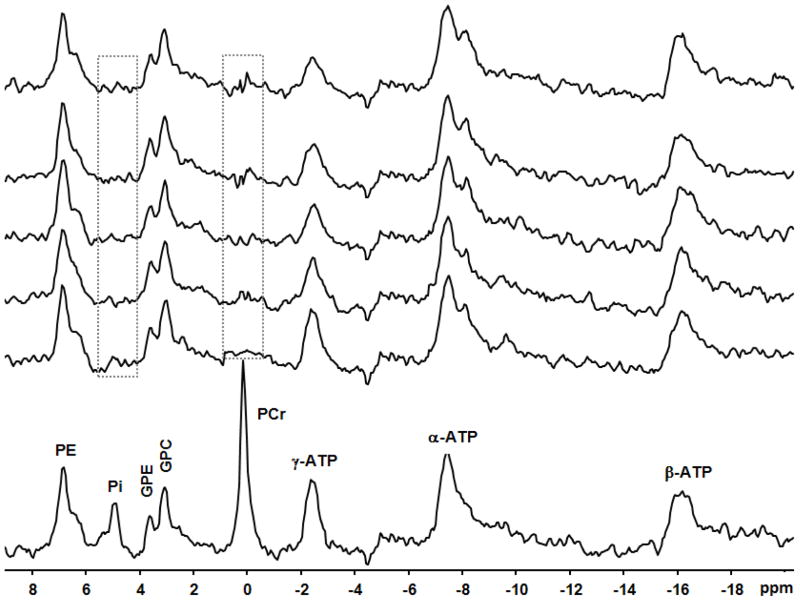

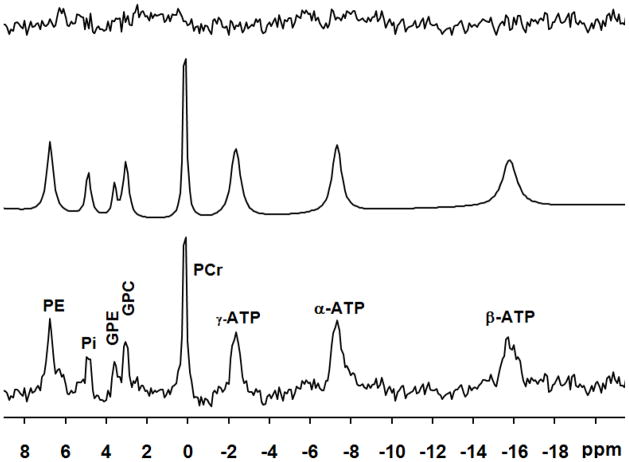

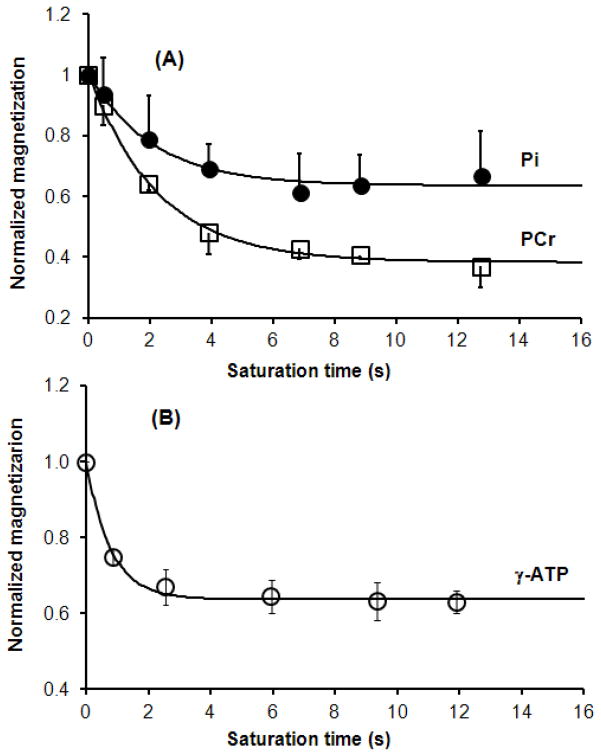

Brain anatomic imaging (in the sagittal orientation) and experiment set-up are illustrated in Fig. 1. The 31P sensitivity region of the surface coil used in the current experiment was determined as ~160 cc, mainly covering the human frontal lobe. 31P spectra acquired from representative subjects for one-site (γ-ATP) and two-site (PCr and Pi) saturation are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The bottom spectra in the Figs. 2 and 3 were acquired in the absence of saturation at approximately full relaxation, and were used to quantify the steady-state concentration of PCr, ATP and Pi. A spectral curve-fitting result is illustrated in Fig. 4, indicating an excellent spectral fitting quality. Based on the measured peak area ratios of PCr, γ-ATP and Pi and [ATP] = 3.0 μmol/ml taken from the literature (20, 21), PCr and Pi concentrations were determined and presented in Table 1. With the progressive increase in saturation time indicated in Fig. 5, magnetizations of PCr and Pi for one-site saturation and γ-ATP for two-site saturation gradually decreased and settled to a low steady-state at the longest saturation times. PCr and Pi magnetization decreased by about 63% and 33% at steady-state while that of γ-ATP decreased by about 37% (see Table 1).

Fig. 1.

T2-weighted Brain anatomic imaging (in the sagittal orientation) with a 7-cm 31P surface coil. 31P surface coil position is illustrated by a 1-cm sphere with the saline solution at the center of 31P surface coil.

Fig. 2.

In vivo31P spectra with 10-Hz line broadening of a representative subject in the absence and presence of complete saturation (lowest spectrum and all higher ones, respectively) on the γ-ATP resonance (illustrated by the box) with varied saturation times (from 0 to 12.73 s, longer saturation times presented in progressively higher spectra). All resonance peaks are labeled in the lowest spectrum.

Fig. 3.

In vivo31P spectra with 10-Hz line broadening of a representative subject in the absence and presence of complete saturation (lowest spectrum and all higher ones, respectively) on the PCr and Pi resonances (illustrated by the boxes) with varied saturation times (0 to 11.89 s, longer saturation times presented in progressively higher spectra).

Fig. 4.

A 31P spectrum (bottom) acquired from the frontal lobe of a representative subject and its fitted spectrum (middle) and residue (upper). A line-broadening of 6 Hz was applied to display the spectra.

Table 1.

Results of Magnetization Saturation Transfer Measurements in the Human Frontal lobe

| Sat (γ-ATP) | Sat (PCr and Pi) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Subject # | N=9 | N=8 | ||

| Concentration (μmol/ml) | [PCr]=4.13±0.40; [Pi]=1.09±0.17 | [PCr]=4.14±0.62; [Pi]=1.08±0.21 | ||

| M*/M0 of PCr | 0.37±0.07 | — | ||

| M*/M0 of γ-ATP | — | 0.63± 0.05 | ||

| M*/M0 of Pi | 0.67±0.11 | — | ||

| Rate constant (s−1) |

|

|

||

|

| ||||

| T1 (s) |

|

|

||

|

| ||||

|

|

|

|||

|

| ||||

| Chemical exchange flux (μmol/g/min) |

|

|

||

|

| ||||

|

|

||||

Fig. 5.

Dependence of the averaged normalized resonance peaks integrals on the saturation time for one-site saturation (A, n=9) and two-site saturation (B, n=8), respectively. The peak integrals represent the normalized Ms/M0 ratios with the correction of offset RF saturation effect. The apparent and intrinsic spin-lattice relaxation times of PCr and Pi, the forward rate constants ( and ), were determined by the regression analyses presented in (A). The apparent and intrinsic spin-lattice relaxation times of γ-ATP, the reverse rate constant ( ), were determined by the least-square regression and presented in (B).

Chemical exchange rate constants and fluxes determined by magnetization transfer experiments

Figs. 5A shows the time dependency of the averaged and normalized resonance peak integrals of PCr and Pi on the saturation time during the progressive saturation experiment and their least-square regression curves according to Eqs. [2a] and [2b]. and of PCr and the forward exchange rate constant from PCr to ATP (i.e. ) were determined as 2.20±0.29 s, 5.80±0.97 s and 0.29±0.04 s−1, respectively. Similarly, and of Pi and the forward exchange rate constant from Pi to ATP (i.e., ) were determined (see Table 1). With the measured concentrations of PCr and Pi, the unidirectional forward chemical exchange fluxes for CK and ATPsyn were calculated and all results are listed in Table 1.

Parallel to our γ-ATP saturation experiment, and of γ-ATP were determined by two-site saturation experiments (see Figs. 3 and 5B). Results including the reverse chemical exchange flux are listed in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that it is feasible to calculate ATP synthesis and hydrolysis rates for the CK and ATPsyn/ATPase reactions in the human frontal lobe non-invasively at 4T. Our results are broadly consistent with previous work (20, 22–25) as described below, and we extend these findings to include a new brain area that has not been previously studied.

Previous work indicated that in vivo 31P MT provides a non-invasive approach for directly studying bioenergetics/mitochondrial function associated with brain activity changes (12–14, 24, 26). The major obstacle to this approach is the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) especially for ATPsyn reaction measurements because of the intrinsically low nuclear gyromagnetic ratio of 31P and the low concentration of Pi (~1mM). Therefore, to achieve sufficient SNR for ATPsyn reaction measurements in this preliminary study, a relatively large region covered by a 7-cm 31P surface coil was studied at 4T, where our group conducts patient-oriented MRS studies based on a private psychiatric hospital. Based on our results of 1D profiles of three orthogonal dimensions, the majority of 31P signal acquired by the 7-cm 31P coil come from the region of the frontal lobe including gray and white matter contributions. In this study we did not conduct an explicit comparison between 4T and our previous data collected at 7T. However, there are some interesting differences between 4T and 7T studies that deserve mention. First, the 31P signal from Pi in the intra-cellular and extra-cellular compartments and GPE/GPC (see Figs. 2 and 3) are resolved at 7T(14) while at 4T they were resolved only 20% of the time (3 subjects out of 17; see Figs. 3 and 4) despite very good shimming. In the current experiment, the line width of PCr is ~ 14 and 10 Hz without line broadening for the case of Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. Second, of PCr was 5.80 ± 0.97 s at 4T compared but was much shorter at 7T (4.89 ± 0.54 s) (14). An even shorter for PCr (3.83±0.57 s) was measured in the rat brain at 9.4T (13). The observed decreases in of PCr as magnetic field strength increases suggest that the 31P spin of PCr relaxation may be dominated by the chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) mechanism (27). By contrast, of Pi was calculated at 3.56 ± 0.72 s, 3.77 ± 0.53 s and 4.03 ± 0.64 s at 4T, 7T and 9.4T, respectively (13,14), with the significant difference between 4T and 7T on the one hand and 9.4T on the other (p=0.007, two-tailed t-test). This relationship demonstrates that the intrinsic T1 of Pi increases with the magnetic field strength and the 31P spin of Pi relaxation may be dominated by dipolar interactions (27). of γ-ATP was calculated as 1.42 ± 0.21 s in the current 4T study, which is similar to observations at 7T and 9.4T (~1.35 s and ~1.24 s in human and rat brain, respectively) (13,14,28). Again, this observation indicates that the field dependence of phosphate T1 is mainly due to two competing relaxation mechanisms, CSA and dipolar interactions. The intrinsic relaxation times of PCr, γ-ATP and Pi were compared in the current study, but similar trends have been observed in previous studies measuring T1 via a conventional inversion recovery method and single exponential curve fitting (29,30). T1 measurements for PCr, γ-ATP and Pi would be affected by the chemical exchange rate constants since the three metabolites are involved in chemical reactions with one another (31).

In addition to measuring the unidirectional forward chemical exchange fluxes of CK and ATPsyn reactions and simultaneously the intrinsic relaxation times of PCr and Pi in one set of experiments, we measured the reverse chemical exchange flux and the γ-ATP intrinsic relaxation time by saturating PCr and Pi simultaneously in another. The apparent total ATP hydrolysis rate constant, , were determined as 0.43 ± 0.07 s−1. Using the unidirectional forward chemical exchange constants calculated from saturating γ-ATP and concentrations of PCr, ATP and Pi, as well as a chemical balance condition assumption, the reverse chemical exchange rate constant of ATP hydrolysis to PCr and Pi were deduced as 0.45 ± 0.06 s−1, very similar to the value (0.43 ± 0.07 s−1) directly determined by the two-site saturation experiment and not significant difference. Therefore, the current experiments measuring forward and reverse chemical reaction fluxes indicate that the chemical reactions among PCr, ATP and Pi are at an approximately balanced condition and the simple global chemical exchange model of PCr↔ATP↔Pi can be used to measure energy production and utilization in a combined 31P magnetization transfer strategy.

One methodological limitation of conventional 31P magnetization transfer approaches is the relatively long acquisition time (14, 19, 32–40), which prevents adequate temporal resolution for dynamic studies such as monitoring acute drug effects. For instance, the current measurements were performed with a 14-s repetition time at an approximately (although perhaps not completely) fully relaxed condition.

Some novel 31P MT approaches such as FAST and TRIST aim to measure the same chemical reaction fluxes (41, 42). Recently, we developed a 31P MT MRS approach (T1nom), aimed at rapidly mapping energy-ATP metabolic fluxes (28,43). Using this approach, only 2 spectra with optimized flip angles (β) and TR need be obtained to calculate chemical exchange fluxes of the CK and ATPsyn reactions as long as the intrinsic relaxation times of PCr, γ-ATP and Pi are known. The great advantage of this approach is that the acquisition time is significantly shorter, enabling improved SNR, increased spatial/temporal resolution, and higher reliability. Our current measurements lay the groundwork for rapid acquisition 31P MT MRS with the increased spatial and temporal resolution by establishing the necessary values for the relevant metabolites in the healthy human frontal lobe at 4T.

In summary, a 31P MT approach to measure ATP metabolic rates in the human frontal lobe was applied in the current study. Specifically, the unidirectional forward chemical exchange metabolic fluxes of the CK and ATPsyn reactions and reverse chemical exchange metabolic flux associated with ATP hydrolysis were determined at 4T. Thus, the current experiments indicate the kinetic network of PCr↔ATP↔Pi can be measured in human frontal lobe at 4T by using in vivo 31P MT. This work provides a foundation for future studies of bioenergetics/mitochondrial function in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders at our 4T scanner.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NIH grants: 1R21MH092704, 5K23MH079982 and 5T32DA015036.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rezin GT, Amboni G, Zugno AI, Quevedo J, Streck EL. Mitochondrial dysfunction and psychiatric disorders. Neurochem Res. 2009;34(6):1021–1029. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9865-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stork C, Renshaw PF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder: evidence from magnetic resonance spectroscopy research. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10 (10):900–919. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smesny S, Rosburg T, Nenadic I, Fenk KP, Kunstmann S, Rzanny R, Volz HP, Sauer H. Metabolic mapping using 2D 31P-MR spectroscopy reveals frontal and thalamic metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2007;35(2):729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ongur D, Prescot AP, Jensen JE, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF. Creatine abnormalities in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;172(1):44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cataldo AM, McPhie DL, Lange NT, Punzell S, Elmiligy S, Ye NZ, Froimowitz MP, Hassinger LC, Menesale EB, Sargent LW, Logan DJ, Carpenter AE, Cohen BM. Abnormalities in mitochondrial structure in cells from patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Pathol. 177(2):575–585. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.081068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchbanks RM, Mulcrone J, Whatley SA. Aspects of oxidative metabolism in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(3):293–298. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Shachar D, Laifenfeld D. Mitochondria, synaptic plasticity, and schizophrenia. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2004;59:273–296. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(04)59011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2001;21(10):1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slater EC, Holton FA. Oxidative phosphorylation coupled with the oxidation of alpha-ketoglutarate by heart-muscle sarcosomes. I. Kinetics of the oxidative phosphorylation reaction and adenine nucleotide specificity. Biochem J. 1953;55(3):530–544. doi: 10.1042/bj0550530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saks VA, Ventura-Clapier R, Aliev MK. Metabolic control and metabolic capacity: two aspects of creatine kinase functioning in the cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1274(3):81–88. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemp GJ. Non-invasive methods for studying brain energy metabolism: what they show and what it means. Dev Neurosci. 2000;22(5–6):418–428. doi: 10.1159/000017471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaumeil MM, Valette J, Guillermier M, Brouillet E, Boumezbeur F, Herard AS, Bloch G, Hantraye P, Lebon V. Multimodal neuroimaging provides a highly consistent picture of energy metabolism, validating 31P MRS for measuring brain ATP synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(10):3988–3993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806516106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du F, Zhu XH, Zhang Y, Friedman M, Zhang N, Ugurbil K, Chen W. Tightly coupled brain activity and cerebral ATP metabolic rate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(17):6409–6414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710766105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du F, Zhu XH, Qiao H, Zhang X, Chen W. Efficient in vivo 31P magnetization transfer approach for noninvasively determining multiple kinetic parameters and metabolic fluxes of ATP metabolism in the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(1):103–114. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown TR, Ugurbil K, Shulman RG. 31P nuclear magnetic resonance measurements of ATPase kinetics in aerobic Escherichia coli cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74(12):5551–5553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Graaf RA, Luo Y, Garwood M, Nicolay K. B1-insensitive, single-shot localization and water suppression. J Magn Reson B. 1996;113(1):35–45. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer RG, Balschi JA, Leigh JS, Jr, Ingwall JS. ATP synthesis and degradation rates in the perfused rat heart 31P-nuclear magnetic resonance double saturation transfer measurements. Biophys J. 1988;54(5):921–929. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83028-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Boogaart A, Van Hecke A, Van Huffel P, Graveron-Demilly S, van Ormondt D, de Beer R. MRUI: a graphical user interface for accurate routine MRS data analysis. Prague; 1996. p. 318. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degani H, Laughlin M, Campbell S, Shulman RG. Kinetics of creatine kinase in heart: a 31P NMR saturation- and inversion-transfer study. Biochemistry. 1985;24(20):5510–5516. doi: 10.1021/bi00341a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hetherington HP, Spencer DD, Vaughan JT, Pan JW. Quantitative 31P spectroscopic imaging of human brain at 4 Tesla: assessment of gray and white matter differences of phosphocreatine and ATP. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45(1):46–52. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200101)45:1<46::aid-mrm1008>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siesjo BK. Brain energy metabolism. New York: Wiley; 1978. pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mora BN, Narasimhan PT, Ross BD. 31P magnetization transfer studies in the monkey brain. Magn Reson Med. 1992;26(1):100–115. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910260111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mlynarikv ZS, Brehm A, Bischof M, Roden M. An optimized protocol for measuring rate constant of creatine kinase reaction in human brain by 31P NMR saturation transfer. 13th Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med; 2005. p. 2767. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lei H, Ugurbil K, Chen W. Measurement of unidirectional Pi to ATP flux in human visual cortex at 7 T by using in vivo 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(24):14409–14414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2332656100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mason GF, Chu WJ, Vaughan JT, Ponder SL, Twieg DB, Adams D, Hetherington HP. Evaluation of 31P metabolite differences in human cerebral gray and white matter. Magn Reson Med. 1998;39(3):346–353. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du F, Zhang Y, Iltis I, Marjanska M, Zhu XH, Henry PG, Chen W. In vivo proton MRS to quantify anesthetic effects of pentobarbital on cerebral metabolism and brain activity in rat. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(6):1385–1393. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evelhoch JL, Ewy CS, Siegfried BA, Ackerman JJ, Rice DW, Briggs RW. 31P spin-lattice relaxation times and resonance linewidths of rat tissue in vivo: dependence upon the static magnetic field strength. Magn Reson Med. 1985;2(4):410–417. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910020409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiong Q, Du F, Zhu X, Zhang P, Suntharalingam P, Ippolito J, Kamdar FD, Chen W, Zhang J. ATP production rate via creatine kinase or ATP synthase in vivo: a novel superfast magnetization saturation transfer method. Circ Res. 108(6):653–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiao H, Zhang X, Zhu XH, Du F, Chen W. In vivo 31P MRS of human brain at high/ultrahigh fields: a quantitative comparison of NMR detection sensitivity and spectral resolution between 4 T and 7 T. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24(10):1281–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogner W, Chmelik M, Schmid AI, Moser E, Trattnig S, Gruber S. Assessment of 31P relaxation times in the human calf muscle: a comparison between 3 T and 7 T in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62(3):574–582. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horska A, Horsky J, Spencer RGS. Measurement of Spin-lattice Relaxation Times in Systems Undergoing Chemcial Exchange. J Magn Reson Series A. 1994;110:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiss RG, Gerstenblith G, Bottomley PA. ATP flux through creatine kinase in the normal, stressed, and failing human heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(3):808–813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408962102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joubert F, Mateo P, Gillet B, Beloeil JC, Mazet JL, Hoerter JA. CK flux or direct ATP transfer: versatility of energy transfer pathways evidenced by NMR in the perfused heart. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;256–257(1–2):43–58. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009858.41434.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mora BN, Narasimhan PT, Ross BD. 31P magnetization transfer studies in the monkey brain. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1992;26(1):100–115. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910260111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bottomley PA, Hardy CJ. Maping creatine kinase reaction rates in human brain and heart with 4 Tesla saturation transfer 31P NMR. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1992;99:443–448. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mora B, Narasimhan PT, Ross BD, Allman J, Barker PB. 31P saturation transfer and phosphocreatine imaging in the monkey brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(19):8372–8376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brindle KM, Blackledge MJ, Challiss RA, Radda GK. 31P NMR magnetization-transfer measurements of ATP turnover during steady-state isometric muscle contraction in the rat hind limb in vivo. Biochemistry. 1989;28(11):4887–4893. doi: 10.1021/bi00437a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bottomley PA, Hardy CJ, Roemer PB, Weiss RG. Problems and expediencies in human 31P spectroscopy. The definition of localized volumes, dealing with saturation and the technique-dependence of quantification. NMR in Biomedicine. 1989;2(5–6):284–289. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940020518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spencer RG, Balschi JA, Leigh JS, Jr, Ingwall JS. ATP synthesis and degradation rates in the perfused rat heart 31P-nuclear magnetic resonance double saturation transfer measurements. Biophysical Journal. 1988;54(5):921–929. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83028-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sture Forsen RAH. Study of moderately rapid chemical exchange reactions by means of nuclear magnetic resonance. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1963;39(11):2892–2901. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bottomley PA, Ouwerkerk R, Lee RF, Weiss RG. Four-angle saturation transfer (FAST) method for measuring creatine kinase reaction rates in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(5):850–863. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schar M, El-Sharkawy AM, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. Triple repetition time saturation transfer (TRiST) 31P spectroscopy for measuring human creatine kinase reaction kinetics. Magn Reson Med. 63(6):1493–1501. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du F, Xiong Q, Zhu X-H, Chen W. An Improved Magnetization Saturation Transfer Approach---T1nom for Rapidly Measuring and Quantifying CK Activity in the Rat Brain. Stockholm, Sweden: 2010. p. 1111. [Google Scholar]