Abstract

Macrophage (MΦ) activation must be tightly controlled to preclude overzealous responses that cause self-damage. MicroRNAs promote classical MΦ activation by blocking antiinflammatory signals and transcription factors but also can prevent excessive TLR signaling. In contrast, the microRNA profile associated with alternatively activated MΦ and their role in regulating wound healing or antihelminthic responses has not been described. By using an in vivo model of alternative activation in which adult Brugia malayi nematodes are implanted surgically in the peritoneal cavity of mice, we identified differential expression of miR-125b-5p, miR-146a-5p, miR-199b-5p, and miR-378-3p in helminth-induced MΦ. In vitro experiments demonstrated that miR-378-3p was specifically induced by IL-4 and revealed the IL-4–receptor/PI3K/Akt-signaling pathway as a target. Chemical inhibition of this pathway showed that intact Akt signaling is an important enhancement factor for alternative activation in vitro and in vivo and is essential for IL-4–driven MΦ proliferation in vivo. Thus, identification of miR-378-3p as an IL-4Rα–induced microRNA led to the discovery that Akt regulates the newly discovered mechanism of IL-4–driven macrophage proliferation. Together, the data suggest that negative regulation of Akt signaling via microRNAs might play a central role in limiting MΦ expansion and alternative activation during type 2 inflammatory settings.

Introduction

Macrophages (MΦ) are involved centrally in recognizing and containing pathogens. Subsequently, they ensure the efficient induction and upkeep of a protective adaptive immune response. MΦ also help to limit the ensuing immune reaction as well as clear apoptotic cells and other debris.1 The adaption of MΦ to these diverse roles is reflected in the multitude of activation phenotypes that have been described.2 Classical (or M1) and IL-4Rα–driven alternative (or M2) activation represent the 2 most divergent phenotypes, with the former thought to be proinflammatory and important for the clearance of microbial pathogens, whereas the latter are predominantly found during helminth infections and are associated with wound healing and immunosuppression.3–6 In either case, MΦ activation must be closely controlled because excessive activation can lead to tissue destruction or fibrosis, respectively.6,7 Control is achieved by external signals, including cytokines (eg, IL-10, IL-278,9) and hormones (eg, glucocorticoids10) but also by MΦ-intrinsic mechanisms. For example, classically activated MΦ become unresponsive to secondary stimulation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as the result, at least in part, of the induction of negative feedback loops blocking or limiting activating signaling cascades.11 The possibility that microRNAs may mediate such feedback mechanisms has recently attracted considerable interest.11

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are short (18-24 nt), noncoding RNAs that influence the translation of specific genes by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR) of the target messenger RNAs (mRNAs). The interaction between a miRNA and mRNA generally results in destabilization of the mRNA and repression of translation.12 In MΦ, miRNAs have so far been mainly studied during classical activation, where several miRNAs have been found to be differentially regulated (reviewed in O'Neill et al13). miR-125b-5p initially is down-regulated by LPS/TNF-induced Akt signaling to allow efficient TNF production14,15 but is induced during later stages, where it acts to limit further TNF production.16 Similarly miR-146a-5p is up-regulated upon stimulation with LPS and targets the MAPK-signaling pathway of TLRs, specifically IRAK1 and TRAF6.17 Thus, these miRNAs are part of feedback loops that prevent excessive MΦ activation and limit potentially harmful proinflammatory responses. Another M1-associated miRNA, miR-155, can suppress M2 activation by targeting the IL-13 receptor,18 suggesting that miRNAs also are involved in shaping the M1/M2 balance. Furthermore, miRNAs have been shown to control cellular proliferation,19 which has potential relevance to M2 MΦ activation because of the recent discovery that MΦ expansion can occur by IL-4–driven local proliferation rather than recruitment from the blood.20

However, the miRNA-profile associated with alternative activation of MΦ has yet to be described. We therefore aimed to identify miRNAs differentially expressed in an in vivo model of alternative activation and dissect their functional roles. Microarray analysis of MΦ elicited by exposure to the nematode Brugia malayi5,21 identified miR-378-3p as one of the most robustly regulated miRNAs in this Th2 infection context, and experiments in vitro demonstrated that miR-378-3p was induced upon stimulation with IL-4. In silico analysis and miRNA manipulation studies identified potential miR-378-3p targets in the PI3K/Akt-signaling cascade, downstream of the IL-4 receptor. The finding that Akt is a target of miR-378-3p led us to test the consequences of Akt inhibition, revealing this signaling pathway as a critical component of IL-4–driven MΦ proliferation and alternative activation in vivo. Thus, it is likely that miRNAs are a general mechanism for limiting MΦ activation in both alternative and classical activation settings.

Methods

Mice and infection

Wild-type (WT; BALB/c or C57BL/6) and IL-4 receptor-α–deficient (IL-4Rα−/−) mice on a BALB/c background were bred in house. Mice were 6-10 weeks of age at the start of each experiment, and all work was performed in accordance with the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986. Adult B malayi parasites were isolated from the peritoneal cavity of infected jirds purchased from TRS Laboratories or maintained in house. Infections were carried out as described previously.21 A detailed description and additional information can be found in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article.

MΦ isolation and purification

Peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) were seeded at 5 × 106 cells per well to 6-well cell-culture plates (NUNC) in RPMI, 5% FCS, 2mM l-glutamine, 0.25 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. After 4 hours incubation at 37°C/5% CO2, nonadherent cells were washed off, and the adherent cells detached with a rubber policeman. Detached cells were > 80% pure MΦ as assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of their F4/80 and CD11b surface expression. In some experiments as indicated, peritoneal MΦ were purified with FACS on a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences) according to their expression of surface molecules (F4/80+, SiglecF−, CD11b+, CD11c−, B220−, CD3−; all antibodies purchased from BioLegend or eBioscience) reaching purities of > 90%.

Cell-culture experiments

For in vitro experiments, thioglycollate (Thio)-elicited PECs were seeded to 24-well plates at 1 × 106 cells per well in complete RPMI. After 4 hours' incubation, nonadherent cells were washed off, and murine recombinant IL-4 (rIL-4, 20ng/mL, Peprotech), recombinant M-CSF (rM-CSF; 20 ng/mL; Peprotech), LPS (100 ng/mL; Escherichia coli 0111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich), and recombinant IFN-γ (rIFNγ; 20 ng/mL; Peprotech) or medium alone were added and incubated for various periods of time as indicated in the “Results.” For triciribine (1,5-dihydro-5-methyl-1-β-D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,5,6,8-pentaazaacenaphthylen-3-amine; Cayman Europe) treatment, cells were pretreated for 1 hour (see Figure 4 for concentrations) before stimulation. Subsequently, nonadherent cells were washed off and the remaining cells lysed in 700 μL of Qiazol.

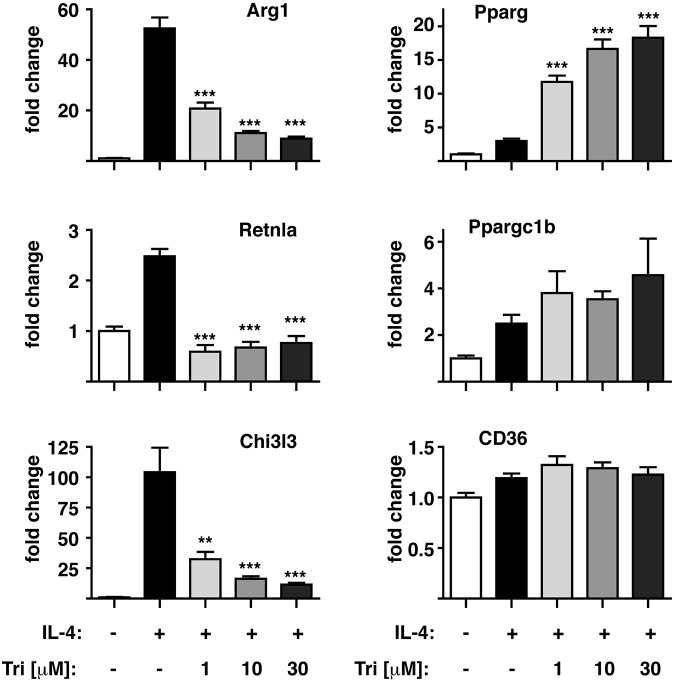

Figure 4.

Akt-inhibition modulates alternative activation of MΦ in vitro. Thio-MΦ were stimulated with rIL-4 (+) or medium (−) after preincubation with the indicated concentration of triciribine for 1 hour and analyzed for expression of alternative activation markers by qRT-PCR. Data are representative of 3-4 animals per group. Error bars indicate SEM. One of 4 experiments shown. Asterisks indicate statistical differences compared with IL-4–treated samples. ***P < .001, **P < .01.

miRNA microarray

The miRCURY miRNA probe set version 8.1 (Exiqon) was printed onto Codelink slides (GE Healthcare) in triplicate per array. Arrays were spot-checked with random hexamer-labeled RNAs. For experiments in this report, RNA (1 μg) was labeled by using the Hy3 power labeling kit (Exiqon), and hybridization and washing were carried out by following the manufacturer's instructions.

Array analysis was carried out with a comparative strategy to identify robustly regulated miRNAs. The background subtracted data were quantile normalized, and the probes recognizing murine miRNA were selected to minimize the multiple testing problem. Medians were calculated for each miRNA per group (n = 4) and expression compared by t test (WT vs IL-4Rα−/− and WT vs Thio). The regulated miRNAs in each comparison were then selected on the basis of those with 2 or more significantly regulated probes and a log2 median intensity on the array greater than the 50th percentile. Our second analysis strategy used the limma suite22 in bioconductor.23 A linear model was fitted to each probe across all 4 groups and regulated miRNAs extracted by contrast. Similarly to our analysis of medians, we selected miRNAs as regulated if 2 or more probes for the miRNA had significant uncorrected P values and the median was greater than the 50th percentile. The lists from each analysis were then examined and overlapping miRNAs chosen for follow-up analysis. Microarray data have been deposited to NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession no. GSE35047 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc= GSE35047).

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

Whole 3′UTRs of target genes (ie, Akt1, Grb2) were cloned into the psiCHECK-2 vector (Promega) immediately downstream of the Renilla luciferase gene. Mutations in the 3′UTR of Akt1 or Grb2 were generated with the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene), resulting in altered binding sites for miR-378-3p (AGUCCAG → AGUGGAG). NIH-3T3 fibroblasts were cotransfected with 200 ng of the psiCHECK-2 constructs and 2.5 pmol of synthetic miR-378-3p precursor (hsa-miR-378 premiR; Applied Biosystems) or scrambled miRNA control (premiR neg. control no. 1; Applied Biosystems) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 48 hours after transfection, relative luminescence was measured with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) on a LumiStar luminometer (BMG Labtech) following the manufacturer's instructions. Resulting luminescence values were used to generate ratios of Renilla to firefly luciferase activity and are depicted as fold change compared with a no-RNA transfected control for each construct.

Affymetrix messenger RNA array and data analysis

To determine genes potentially regulated by miR-378-3p, NIH-3T3 cells were reverse-transfected with a miR-378-3p mimic or inhibitor (25nM) and compared with control-transfected RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC)–free siRNA cells. A total of 300 ng of total RNA was converted to cDNA with the GeneChip WT cDNA Synthesis and Amplification Kit (Affymetrix) and hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Array according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the bioinformatic analysis, Partek Genomics Suite Version 6.5 software (Partek Inc) was used to assess the GeneChip quality control and perform gene expression analysis using Affymetrix metafiles. Data from 9 chips met the quality control requirements; thereby, all were included.

The RMA method was used to normalize and summarize the intensity levels of all 28 853 probes.24 On the basis of the (log 2 value) of negative control probes of each chip, the background fluorescence was calculated in StatPlus statistical tool pack software (AnalystSoft) and then used to statistically eliminate the microarray's background noise generating a list of 12 665 probes. We used Partek software to compute the fold change and statistical significance (false discovery rate–adjusted P value) using 1-way ANOVA test. Microarray data have been deposited to NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession no. GSE34873 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc= GSE34873).

In vivo IL-4 complex treatment

MΦ proliferation in vivo was stimulated by intraperitoneal injection of 5 μg of rIL-4 complexed to 25 μg of anti–IL-4 antibody (IL-4c; clone: 11B11; molar ratio 2:1).20 Where indicated, mice were pretreated intraperitoneally with triciribine (1 mg/kg) 1 hour before injection of IL-4c. At 21 hours after IL-4c injection, mice received 100 μL of BrdU (10 mg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) subcutaneously, and PECs were harvested 3 hours later.

MΦ transfection experiments

RAW264.7 cells were stained with 5μM of Vybrant CFDA SE cell tracer (Invitrogen) followed by reverse transfection with a miR-378-3p mimic or inhibitor (25nM) as described previously and analyzed for cellular expansion after 24 hours and 48 hours. At 4 hours before the end of the incubation, 100 μL of alamarBlue was added to the culture. Cell proliferation was analyzed by measuring alamarBlue conversion in a FluoStar (BMG Labtech) fluorescence plate reader and Vybrant CFDA SE dilution by FACS analysis. Data were pooled from 3 experiments and are presented as percent of control to account for inter-experimental changes in staining intensity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with JMP statistical analysis software (JMP 8.0.1; SAS Institute Inc). Differences between groups were determined by ANOVA followed by a Tukey-Kramer HSD multiple comparison test. In some cases, data were log-transformed to achieve normal distribution as determined by optical examination of residuals, or where this was not possible, a Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Differences were considered statistically significant for P< .05.

Results

To identify miRNAs differentially regulated in alternatively activated MΦ in vivo, we performed a miRNA array screen on peritoneal MΦ isolated from mice surgically implanted with the parasitic nematode B malayi. As described previously, B malayi implant results in a very strongly Th2-biased immune response and induces the accumulation of alternatively activated MΦ at the site of implantation.5 For comparison, we used IL-4Rα–deficient (IL-4Rα−/−) animals whose MΦ fail to express alternative activation markers in this model.25 Additional WT mice underwent sham surgery and were injected with Thio 3 days before necropsy to generate inflammatory MΦ not associated with helminth infection. A 2-way comparison of WT nematode-elicited MΦ (NeMΦ) with Thio-elicited MΦ (Thio-MΦ) or IL-4Rα−/− NeMΦ allowed us to identify infection-dependent and IL-4Rα–dependent miRNAs, respectively. At 3 weeks after implantation, MΦ were isolated from the peritoneal cavity by adherence to cell-culture plates and total RNA extracted. The expression levels of 648 unique human and mouse miRNAs in their mature form were determined by use of the Exiqon miRCury 8.1 array platform. Bioinformatic analysis (see “miRNA microarray” for details) revealed differential expression of 19 miRNAs in WT-NeMΦ compared with either Thio-MΦ or IL-4Rα−/− NeMΦ (supplemental Table 2).

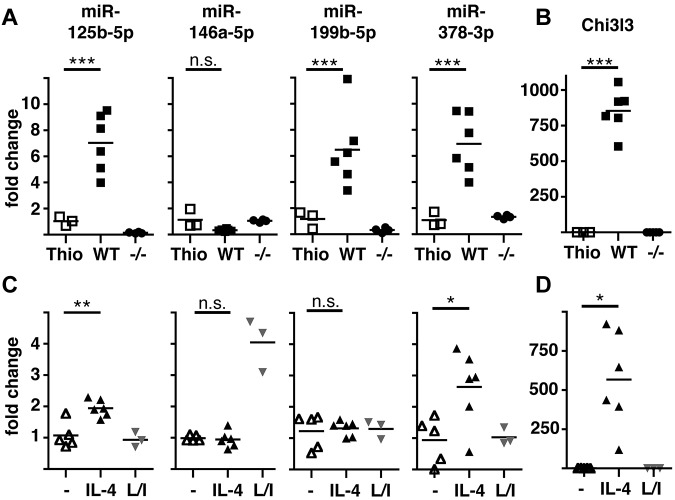

We then chose to validate expression levels of the 10 most differentially regulated miRNAs (ie, greatest fold change) identified in the array. A proportion of the originally isolated RNA was subjected to quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), with further analysis in 2 subsequent experiments using FACS-sorted MΦ (> 90% F4/80+CD11b+). These experiments confirmed significant differential expression of 9 of these 10 miRNAs but also revealed that only 4 of these were differentially regulated in both comparisons (WT NeMΦ vs WT Thio-MΦ and vs IL-4Rα−/− NeMΦ) and therefore specific for alternatively activated MΦ (Table 1 and Figure 1A). miR-125b-5p, miR-199b-5p, and miR-378-3p were found to be significantly up-regulated in vivo, whereas miR-146a-5p showed a tendency toward an IL-4Rα–dependent downmodulation (Figure 1A). This tendency in miR-146a-5p expression was statistically significant (P = .0022) when all 3 experiments were combined. To confirm the activation state of the isolated MΦ, expression of the alternative activation marker chitinase 3-like 3 (Chi3l3/Ym1) was measured and, as expected, found to be exclusively up-regulated in WT NeMΦ but not in IL-4Rα−/− MΦ (Figure 1B).

Table 1.

Log2-fold change of significantly differentially expressed microRNAs as assessed by microRNA array or qRT-PCR

| microRNA-ID | BALB/c NeMΦ vs BALB/c ThioMΦ |

BALB/c NeMΦ vs IL-4Rα−/− NeMΦ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Array | qRT-PCR | Array | qRT-PCR | |

| miR-18a-5p | −1.31 | −1.01 | – | – |

| miR-125b-5p | – | 2.11 | 1.91 | 4.90 |

| miR-146a-5p | −1.46 | −1.47 | – | −1.47 |

| miR-150-5p | – | – | −1.97 | −2.15 |

| miR-199b-5p | – | 3.49 | 2.04 | 4.59 |

| miR-221-3p | −1.53 | −2.11 | – | – |

| miR-222-3p | −1.27 | −2.11 | – | – |

| miR-342-3p | −1.51 | −1.81 | – | – |

| miR-378-3p | 2.10 | 2.42 | 2.28 | 2.14 |

| miR-689 | – | – | −2.56 | – |

– indicates not significant.

Figure 1.

Validation of differential expression of miRNAs in AAMΦ in vivo and in vitro. (A) Peritoneal MΦ were isolated from Thio-injected BALB/c mice or from B malayi–infected BALB/c (WT) or IL-4Rα−/− (−/−) mice and expression of the indicated miRNAs assessed by qRT-PCR. Each data point shown reflects data from individual mice. (B) Chi3l3 expression in the cells isolated in panel A. (C) Thio-elicited, adherence-purified MΦ were incubated with rIL-4 (IL-4), LPS/IFNγ (L/I), or without stimulus (−) for 16 hours and analyzed as in panel A. (D) Chi3l3 expression in the cells isolated in panel C. One of 3 separate experiments shown. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; n.s. indicates not significant.

It was possible that the changes we observed were the result of secondary (IL-4Rα–dependent) events occurring in vivo and not because of direct MΦ activation via IL-4/13. Thus, we tested the expression of miR125b-5p, miR-146a-5p, miR-199b-5p, and miR-378-3p in Thio-MΦ stimulated in vitro with rIL-4 or LPS and rIFNγ (Figure 1C). qRT-PCR revealed significant up-regulation of miR-125b-5p and miR-378-3p after treatment with IL-4 but not after LPS/IFNγ-stimulation, confirming the association of these miRNAs with the alternative activation phenotype. In contrast, miR-199b-5p was not altered by IL-4 or LPS/IFNγ treatment, indicating that the observed up-regulation in vivo is not because of direct effects of IL-4R–signaling on MΦ. miR-146a-5p has previously been found to be highly up-regulated in classically activated MΦ17 and was consequently specifically induced by LPS/IFNγ stimulation, but no change in expression could be detected by IL-4 stimulation in vitro at this time point (Figure 1C). Successful and specific induction of alternative activation under these conditions was confirmed by Chi3l3-expression (Figure 1D).

miR-125b expression in MΦ has previously been demonstrated to be modulated by factors other than IL-4.15,16 We selected miR-378-3p for further investigation into its potential to regulate alternative activation of MΦ because it appeared to be the most specific for IL-4Rα–mediated signals. Furthermore, miR-378-3p was of particular interest because it is encoded in an intronic region of the peroxisome proliferative–activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 β gene (Ppargc1b),26 which has previously been shown to be associated with the alternative activation phenotype.27

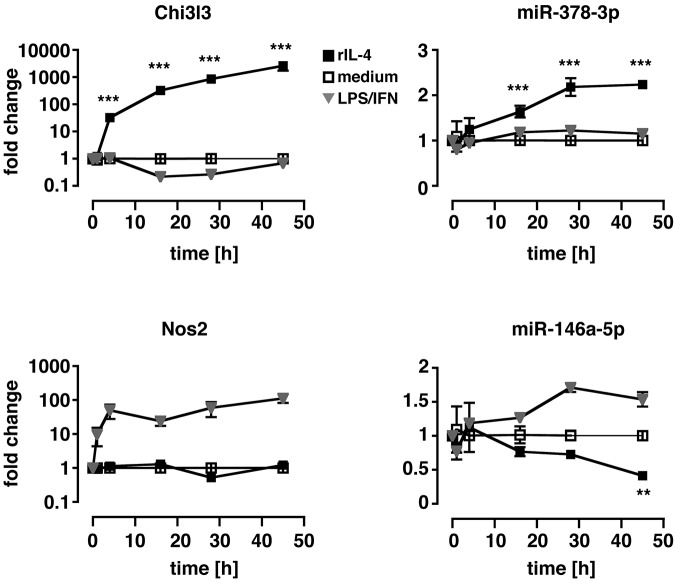

To evaluate whether up-regulation of miR-378-3p was a prerequisite for alternative MΦ activation or a consequence thereof, we performed in vitro time-course experiments of IL-4 stimulation (Figure 2) in which Thio-MΦ were incubated with murine rIL-4 for 1, 4, 16, 28, and 45 hours. Cells were subsequently analyzed for mRNA and miRNA expression with qRT-PCR. Significantly increased levels of Chi3l3 expression were detectable as early as 4 hours after treatment of MΦ with IL-4 and continued to increase until the end of the experiment. In contrast, miR-378-3p was not significantly up-regulated until 16 hours after the addition of IL-4 but remained elevated thereafter. Notably, classical activation of MΦ via the use of LPS/IFNγ did not result in the up-regulation of Chi3l3 or miR-378-3p at any time point but potently induced expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nos2) and miR-146a-5p as described previously.17,28 Interestingly, in line with our in vivo data (Figure 1A), miR-146a-5p was significantly reduced after IL-4 stimulation at very late time points (45 hours) but not at 24 hours. This finding might explain why we were unable to detect a direct effect of IL-4 on miR-146a-5p expression in the previous in vitro experiments measured at 16 hours after treatment (Figure 1C).

Figure 2.

Kinetics of miR-378-3p induction during in vitro alternative activation. Thio-elicited, adherence-purified MΦ were incubated with rIL-4 (black squares), LPS and rIFNγ (gray triangles), or with medium alone (open squares) for the indicated time and analyzed for miRNA and mRNA expression. Statistics indicate differences between rIL-4–treated samples and media controls. **P < .01; ***P < .001. Each data point represents mean and SEM of 3 individual animals. One of 2 separate experiments shown.

To examine cellular genes that respond to changes in miR-378-3p expression, we used a murine fibroblast cell line that expresses miR-378-3p and supports miRNA overexpression and inhibition analysis, as described.29 NIH-3T3 fibroblasts were transfected with either miR-378-3p–mimics or inhibitors and resulting changes in gene-expression analyzed with an Affymetrix-mRNA array. We were able to identify 491 significantly differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate; P < .05) with more than 1.4-fold change in either of the 2 conditions compared with a negative-control. Pathway enrichment analysis of these differentially expressed genes by DAVID Bioinformatics Resources for gene annotation and KEGG pathway analysis (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp) revealed the Jak-STAT signaling pathway as significantly over-represented (EASE-score P < .05).

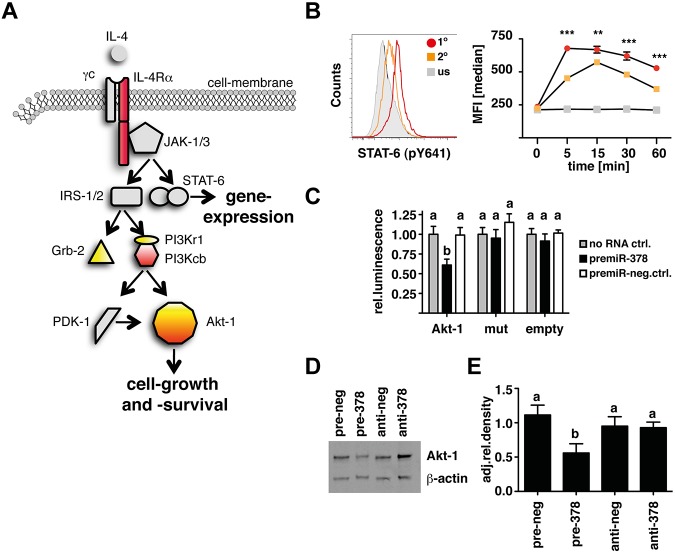

More specifically, in conjunction with the online prediction software TargetScan (TargetScanMouse; Release 5.1:April2009; http://www.targetscan.org) several potential target-genes within the IL-4Rα/PI3K/Akt–signaling cascade could be identified. Figure 3A illustrates the components of the IL-4Rα pathway that were predicted by TargetScan (yellow) and differentially expressed in transfected fibroblasts (red). In particular Akt-1 was identified in both analyses. This finding suggested the possibility that IL-4 induction of miR-378-3p results in a negative feedback on the IL-4 signaling pathway. Because receptor “tolerance” has not previously been described for this pathway, we tested whether IL-4 does induce a negative feedback-mechanism by measuring STAT-6–phosphorylation in Thio-MΦ after secondary IL-4 stimulation. As outlined in Figure 3B, MΦ that had previously been exposed to IL-4 showed reduced and delayed STAT-6 phosphorylation in response to secondary IL-4 stimulation.

Figure 3.

miR-378-3p targets the IL-4R/PI3K/Akt-signaling pathway. (A) Schematic depiction of the IL-4R–signaling cascade highlighting putative targets for miR-378-3p. Yellow indicates predicted by TargetScan; red: differentially expressed genes in pre- and anti-miR-378-3p–transfected fibroblasts. (B) Analysis of rIL-4–elicited STAT-6 phosphorylation by intracellular FACS staining. Histogram of STAT-6 (pY641) expression in Thio-MΦ preincubated with rIL-4 (orange line) or medium (red line) for 24 hours before restimulation with rIL-4 (open histograms) or medium (filled gray histograms) for 5 minutes. Timeline of pSTAT-6 (pY641) expression in rIL-4 (orange squares) or medium (red circles) pretreated, rIL-4–stimulated (colored symbols) or unstimulated (gray symbols) cells. Data show median fluorescence intensity of 6 individual animals ±SEM. For unstimulated controls, cells were pooled from several animals. Asterisks indicate statistical differences between rIL-4–preincubated and freshly stimulated MΦ. ***P < .001; **P < .01. (C) Luciferase-assay using the 3′UTR of wild-type Akt-1 (Akt-1) or constructs with mutated seed-region binding sites for both predicted miR-378-3p binding sites (mut) or without insert (empty). Data indicate cotransfection with a miR-378-3p mimic (black bars) or a scrambled control (open bars). Data are pooled from 5 separate experiments and depicted as relative luminescence compared with no-RNA controls (gray bars). Bars not connected by the same letters are statistically significantly different. (D) Representative Western blot analysis of RAW264.7 cells 12 hours after transfection with a mimic (pre-378) or inhibitor (anti-378) of miR-378-3p or appropriate negative controls (pre- and anti-neg). Samples were separated on 4%-12% Bis-Tris gels and stained for Akt-1 and β-actin at the same time. (E) Densitometric analysis of the samples analyzed in panel D. Data are representative of 4 separate experiments. Columns not connected by the same letters are statistically significantly different.

To obtain direct evidence that miR-378-3p targets the PI3K/Akt1-pathway, we generated Luciferase-constructs containing the 3′UTR of thymoma viral proto-oncogene 1 (Akt1) or a mutated version thereof where 2 nucleotides within both seed-region-binding sites for miR-378-3p were altered (supplemental Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 3C, cotransfecting NIH-3T3 fibroblasts with a mimic of miR-378-3p significantly inhibited Luciferase expression compared with cells transfected with the Luciferase construct alone or cotransfected with a negative control RNA. Importantly, these effects were lost when both miR-378-3p–binding sites within the Akt1-3′UTR were mutated. Furthermore, transfection of RAW264.7 cells led to a marked decrease in Akt-1 protein levels as assessed by Western blot analysis (P < .01 in every comparison; Figure 3D-E). Similar results were obtained for growth factor receptor–bound protein 2 (Grb2; P < .05; supplemental Figure 1B-D). Interestingly, the use of a miR-378-3p inhibitor increased protein expression of Akt-1 in some experiments, but this was not significant when the data of several experiments were combined (Figure 3D-E).

The identification of Akt as a target of miR-378-3p led us to assess the potential influence of Akt-inhibition on MΦ alternative activation by using a specific Akt inhibitor, triciribine30 (Figure 4). Preincubation of Thio-MΦ with triciribine severely disrupted their ability to fully alternatively activate in a dose-dependent manner as shown for the expression of Chi3l3, resistin-like α (Retnla/Relm-α) and arginase 1 (Arg1; Figure 4). Of note, Akt inhibition differentially affected the expression of these markers with complete abrogation of IL-4–driven Retnla but only partial inhibition of Chi3l3 and Arg1 induction. In contrast, other marker genes of alternative MΦ activation (eg, Cd36, Pparg, Ppargc1b) were not negatively influenced by the inhibition of Akt. Thus, limiting Akt-signaling does not completely block IL-4–mediated alternative activation but changes the associated gene expression profile, perhaps to generate cells better suited to chronic type-2 inflammatory settings.

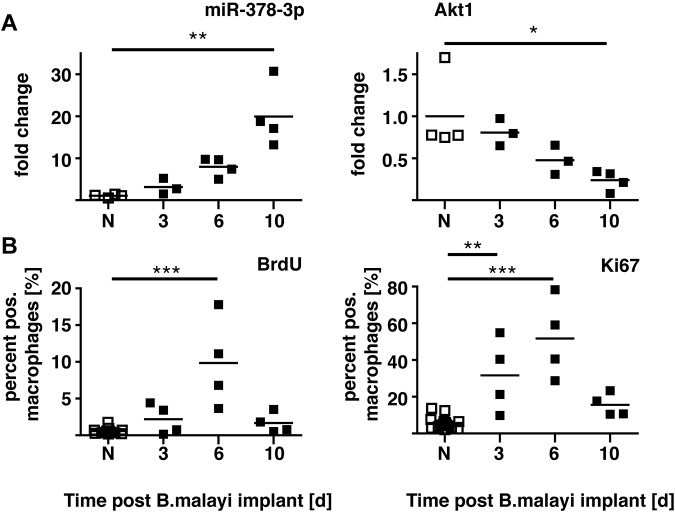

We recently demonstrated that proliferation of the local MΦ population is an integral part of Th2-mediated inflammation with no requirement for blood monocyte recruitment.20 The expansion in cell numbers after surgical implantation of B malayi nematodes occurs as an early burst of rapid cellular proliferation, which then subsides (supplemental Figure 4 in Jenkins et al20). Of note, RNA isolated from these MΦ revealed a delayed increase in miR-378-3p expression that peaked when MΦ proliferation subsided and Akt1 gene expression declined (Figure 5). Critically, injection of active IL-4 alone can drive this proliferative program in vivo. Because both miRNAs and the PI3K/Akt pathway inherently are associated with cellular growth and proliferation, we speculated that IL-4–driven MΦ proliferation is mediated via Akt signaling, with miR-378-3p and possibly other miRNAs acting as negative regulators.

Figure 5.

Time course of miR-378-3p expression and markers of proliferation after B malayi implantation. (A) Gene expression of miR-378-3p and Akt1 in peritoneal MΦ isolated from B malayi implanted C57BL/6 mice at the indicated time points after implantation. N indicates naive animals. Data points represent individual animals or separate pools of animals. (B) FACS analysis of Ki67 expression and BrdU incorporation in the MΦ analyzed in panel A. Data from the same experiment shown in supplemental Figure 4 in Jenkins et al.20 One experiment of 1 shown. ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05.

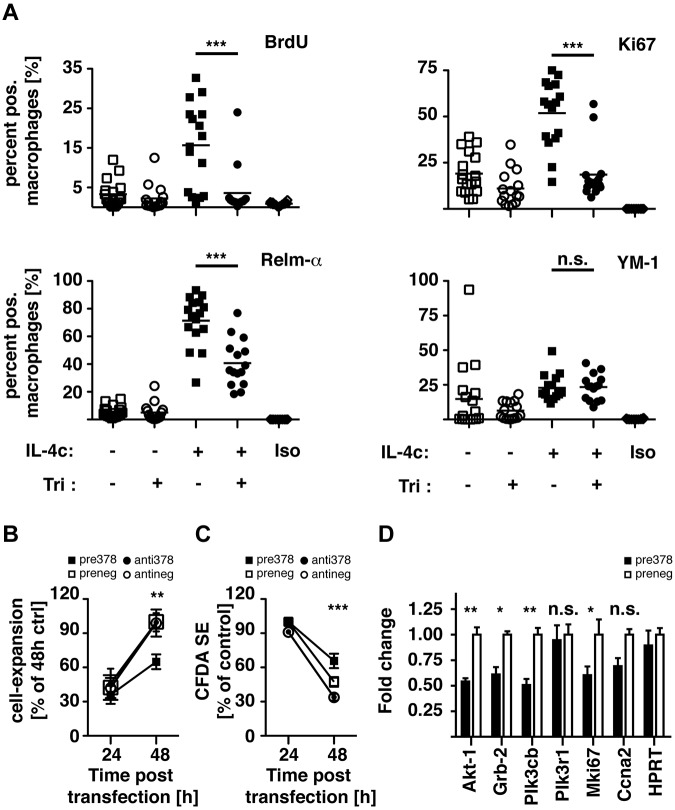

We thus chose to test the role of Akt-signaling during IL-4–mediated MΦ proliferation. For this, mice received a single dose of triciribine or vehicle control intraperitoneally 1 hour before the injection of IL-4 complexed with anti–IL-4 antibody (IL-4c), which allows sustained delivery of active cytokine.20 After 21 hours, mice were injected with BrdU to label cells in the S-phase, and 3 hours later peritoneal exudate cells were analyzed for expression of proliferation and alternative activation markers by FACS. Pretreatment with triciribine completely abrogated IL-4c–induced MΦ proliferation as measured by the incorporation of BrdU or expression of Ki67 (Figure 6A). Simultaneously, protein levels of the alternative activation marker Relm-α were only partially reduced and YM-1 expression did not seem affected at all. These data indicate that similar to the effects observed in vitro, IL-4–induced Akt-signaling is responsible for only specific features of alternative MΦ activation but is essential for IL-4–driven proliferation.

Figure 6.

Akt inhibition and miR-378-3p overexpression negatively regulate MΦ proliferation. (A) BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of triciribine (1 mg/kg) or vehicle control 1 hour before injection of IL-4c or PBS. After 24 hours cells were analyzed for proliferation and alternative activation by FACS analysis. Each data point is representative of an individual animal. Pooled data from 3 separate experiments shown. (B) Conversion of alamarBlue by RAW264.7 cells 24 and 48 hours after transfection with a miR-378-3p mimic (black squares) or inhibitor (black circles) or the appropriate negative controls (open symbols). Data representative of 3 separate experiments. (C) FACS-analysis of Vybrant CFDA SE dilution in the cells analyzed in panel A. (D) Gene expression of miR-378-3p target genes and genes associated with cell proliferation in RAW264.7 cells 48 hours after transfection with a miR-378-3p mimic (black bars) or the appropriate negative control (open bars). ***P < .001; **P < .01; *P < .05; n.s. indicates not significant.

Furthermore, to establish a role for miR-378-3p in the regulation of MΦ proliferation,we transfected RAW264.7 cells with a miR-378-3p mimic or inhibitor and analyzed the resulting changes in cellular expansion. Conversion of alamarBlue and loss of Vybrant CFDA SE staining were used to monitor cell expansion and cell division, respectively. During a 24-hour period, cells transfected with the miR-378-3p mimic displayed a significantly reduced increase in the conversion of alamarBlue (Figure 6B) and loss of Vybrant CFDA SE staining (Figure 6C), demonstrating that miR378-3p negatively regulated cell proliferation. Transfection with the miR-378-3p inhibitor had no effect on cellular expansion, indicating that only enhanced miR-378-3p expression as found after IL-4 stimulation regulates proliferation. What is more, gene-expression analyses of RAW264.7 cells transfected with miR-378-3p showed significant reduction in expression of Akt-1 and Grb2, as well as the putative target Pik3cb (Figure 3A) and the proliferation marker Mki67 (Figure 6D). Taken together, these results are consistent with a negative regulation of MΦ proliferation by miR-378-3p through modulation of the PI3K/Akt-signaling pathway.

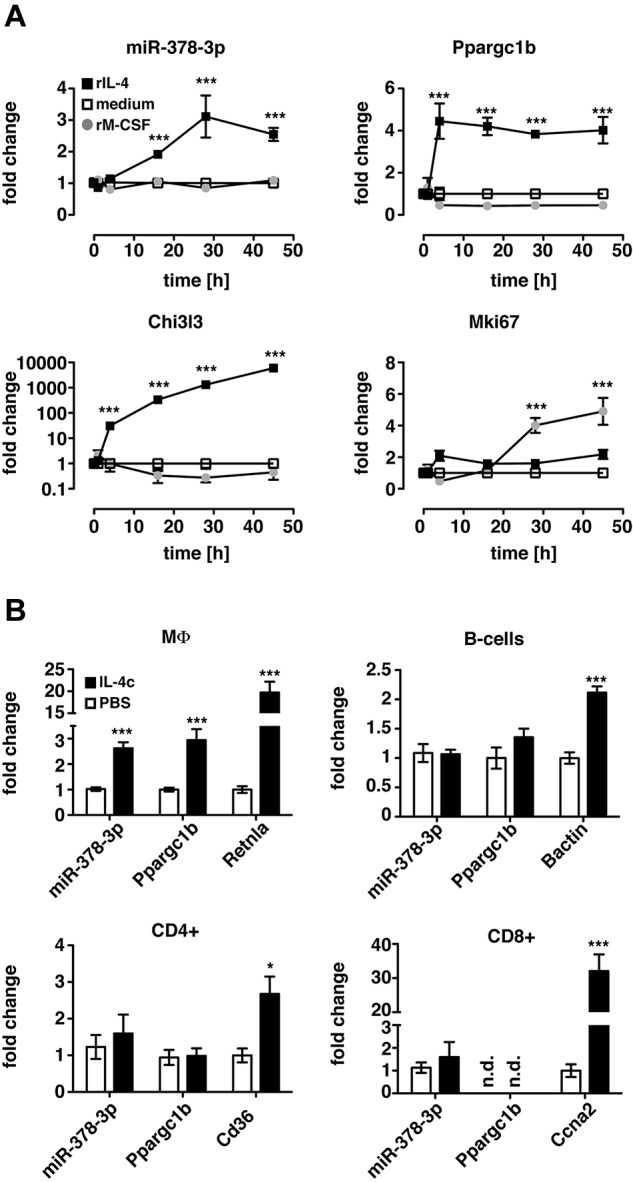

IL-4 impacts the activation state of many cell types, and the PI3K/Akt pathway regulates cellular expansion in various biologic settings. Thus, to determine whether induction of miR-378-3p and therefore potential regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling was a general characteristic of either MΦ proliferation or IL-4 signaling in other cell types, we analyzed miR-378-3p expression in MΦ during IL-4–independent, M-CSF–driven proliferation and in B and T cells after IL-4c stimulation in vivo. As expected, treatment of Thio-MΦ with rM-CSF in vitro stimulated MΦ proliferation as confirmed by increased gene expression of Mki67 (Figure 7A). However, at no point after stimulation could the induction of miR-378-3p or its parent gene (Ppargc1b) be detected.

Figure 7.

Induction of miR-378-3p is specific to IL-4–mediated signaling in MΦ. (A) Thio-elicited, adherence-purified MΦ were incubated with rIL-4 (black squares), rM-CSF (gray circles), or with medium alone (open squares) for the indicated time and analyzed for miRNA and mRNA expression. Statistics indicate differences between rM-CSF–treated samples and rIL-4 controls. ***P < .001. Each data point represents mean and SEM of 6 individual animals. Results from a single experiment shown. (B) CD11b+F4/80+ (MΦ), CD19+F4/80− (B cells), CD4+CD11b− lymphocytes (CD4+) and CD8+CD11b− lymphocytes (CD8+) were FACS-sorted from IL-4c injected (filled bars) or PBS-injected control animals (open bars) and subjected to qRT-PCR. Data are depicted as fold change above PBS controls. Statistics indicate differences between IL-4c–treated samples and PBS-controls. ***P < .001; *P < .05. Bars depict mean and SEM of 10 individual animals per group pooled from 2 independent experiments, except for the CD8+ data, which is from 1 representative experiment. The second experiment is not shown because Ccna2 in the PBS controls was not detectable resulting in a fold change of infinity for the IL-4c treatment.

Similarly, enhanced expression of miR-378-3p and Ppargc1b after IL-4c injection in vivo was found in peritoneal MΦ (F4/80+CD11b+) but not in B cells (CD19+F4/80−), CD4+ (CD4+CD11b−), or CD8+ lymphocytes (CD8+CD11b−) isolated from the same animal (Figure 7B). Of note, IL-4c has previously been shown to also induce proliferation of CD8+ lymphocytes,31 as confirmed in our data by increased expression of cyclin A2 (Ccna2). The failure to induce miR-378-3p in these cells as well as in M-CSF–stimulated macrophages indicates that miR-378-3p is not a general feature of cellular proliferation, whether IL-4 dependent or independent. Furthermore, the lack of induction of miR-378-3p in other cells stimulated with IL-4c shows that although IL-4 signaling has widespread effects on various cell types, the mechanisms controlling these effects are governed by different regulatory mechanisms. Induction of miR-378-3p therefore appears to be a very specific feature of alternative MΦ activation.

Discussion

MΦ isolated from mice infected with the human filarial parasite B malayi become alternatively activated because of exposure to Th2 cells.21 In this in vivo setting, we have identified changes in MΦ expression of miR-125b-5p, miR-199b-5p, miR-378-3p, and miR-146a-5p associated with IL-4Rα–driven alternative activation. In vitro confirmation revealed that miR-125b-5p, miR-378-3p, and miR-146a-5p were directly regulated by IL-4, whereas miR-199b-5p was not, suggesting miR-199b-5p is induced in vivo by other factors and/or that IL-4 is not sufficient. Interestingly another miRNA, miR-223-3p, has recently been described to be associated with the alternative activation phenotype.32 Indeed, miR-223-3p was significantly enhanced in WT NeMΦ vs IL-4Rα−/− NeMΦ in our array but was not among the most highly differentially expressed microRNAs in this in vivo setting and thus not pursued in this study.

Both miR-125b-5p and miR-146a-5p have already been associated with classical MΦ activation. miR-125b-5p expression is initially reduced after LPS stimulation, allowing efficient production of its target, the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α15 but miR-125b-5p is then up-regulated during LPS-tolerance to prevent further/excessive TNF production.16 Thus, miR-125b-5p up-regulation in alternatively activated MΦ may represent a failsafe switch preventing concomitant production of proinflammatory mediators like TNF-α. miR-146a-5p, on the other hand, is normally induced after classical activation of monocytes and is presumed to act in a feedback loop, blocking further TLR and cytokine signaling.17,33 Downmodulation of this miRNA in IL-4–stimulated MΦ could enhance TLR signaling and thus seems counterintuitive. However, reduced levels of miR-146a-5p did not occur until very late after IL-4 stimulation (Figure 3), and long-term preincubation of MΦ with IL-4 has previously been shown to potentiate production of proinflammatory cytokines after secondary stimulation with LPS.34 Thus, whereas up-regulation of miR-125b-5p might help prevent concomitant production of inflammatory mediators, miR-146a-5p–downmodulation may simultaneously sensitize MΦ for potential bacterial pathogens and allow MΦ to quickly adapt their activation phenotype to newly arising challenges. Further experiments are needed to determine the exact role of these 2 miRNAs in shaping MΦ activation.

Here we focus on the new finding that up-regulation of miR-378-3p is part of the alternative MΦ activation program. This finding is consistent with a report that miR-378-3p is up-regulated in a model of allergic airway inflammation.35 Although the authors did not perform cell-type specific analyses, the inflammatory response in these models is characterized by the accumulation of MΦ exhibiting an alternative activation phenotype.36 As noted previously, miR-378-3p is encoded in an intronic region of Ppargc1b,26 a protein associated with alternative activation.27 Thus, coexpression of miR-378-3p may have evolved to complement the role of the protein-encoding gene.37 Ppargc1b is expressed by 4 hours after IL-4 stimulation, which would suggest that Ppargc1b and the primary transcript of mir-378-3p are primary targets of IL-4–induced gene transcription. However, the mature form of miR-378-3p is delayed with respect to its parent gene and other alternative activation markers and thus secondary factors may be needed to regulate its processing.

We identified several miR-378-3p targets within the IL-4R–signaling cascade and more specifically within the PI3K/Akt-signaling pathway. Previous work by MacKinnon et al showed that signaling via PI3K is important for full alternative activation of MΦ,38 and we have extended these findings by using the Akt-specific inhibitor triciribine, confirming Akt as an important downstream target of PI3K during IL-4–induced alternative activation. Interestingly Varin et al showed that pretreatment of MΦ with IL-4 prevented subsequent Akt signaling induced by Neisseria meningitidis, suggesting the induction of a feedback inhibitory mechanism by IL-4.39 Importantly these effects were not observed until approximately 12 hours after IL-4 stimulation, a time point that roughly coincides with the induction of miR-378-3p in our experiments. In addition miR-378-3p has been predicted to target the progesterone-receptor,40 and progesterone has been shown to be an important enhancement factor for alternative activation in wound healing.41 Taken together, these findings strongly suggest a role for miR-378-3p as feedback inhibitor of alternative activation. In this context PI3K/Akt signaling has been shown to enhance antiinflammatory cytokine production during classical MΦ activation and simultaneously reduce production of proinflammatory cytokines.42 Thus, induction of miR-378-3p and limitation of Akt-signaling in alternatively activated MΦ could, similar to our findings with miR-146a-3p, indicate a sensitization for potential concomitant bacterial infections.

PI3K/Akt is a central signaling pathway important for cellular growth and survival, triggered by various growth factors and insulin but also by cytokines and TLR stimulation.43 Although tissue MΦ typically have been regarded as nondividing, recent data show that resident MΦ numbers can be maintained by proliferation.20,44,45 We further demonstrated that tissue MΦ can undergo rapid and extensive proliferation in vivo in response to IL-4 as a mechanism of Th2-driven inflammation that can replace monocyte recruitment.20 Using triciribine, we show here that, similar to the findings in vitro, intact PI3K/Akt-signaling enhances alternative activation of MΦ in vivo but moreover is absolutely essential for IL-4–induced MΦ proliferation.

In a related context, miR-378-3p has been shown to be up-regulated during differentiation of proliferating myoblasts to nonproliferating myotubes and consequently severely downmodulated in cardiotoxin-induced muscle regeneration.46 Similarly, in a model of surgically induced liver injury downmodulation of miR-378-3p has been proposed to allow efficient hepatocyte proliferation by derepressing pro-proliferative molecules like ornithine decarboxylase.47 A human ortholog of miR-378-3p with identical mature sequence, miR-422a, has, in concert with other miRNAs, been proposed to block proliferation of tumor cells by targeting the MAPK pathway.48 Taken together with our observation that miR-378-3p negatively regulated RAW264.7 cell expansion, these results suggest that miR-378-3p is centrally involved in the control of proliferation. Indeed, some of the main pathways identified as potential targets for miR-378-3p in our bioinformatic pathway analysis of transfected fibroblasts, in addition to the Jak/Stat-signaling pathway, included cell cycle–, p53-, and MAPK-signaling pathways, which merit further validation. Importantly our data indicate that despite miR-378-3p having the potential to control proliferation in various cell types and under multiple settings, its induction under normal conditions seems restricted to IL-4–activated MΦ. Most likely this reflects the fact that miR-378-3p will target other, as yet-undefined target genes besides Akt1 and thus have a much broader effect on the cellular phenotype, than discussed here.

We have been unable to demonstrate significant MΦ proliferation with IL-4 in vitro, suggesting that additional signals to the cell, either through cell–cell contacts or as yet-undefined soluble mediators are required. In addition, miRNAs do not typically induce complete knockdown of their targets,12 and miRNAs often act in families targeting a whole metabolic or signaling pathway rather than individual members of these pathways leading to a general suppression of whole metabolic or activation program.49 Further, in vivo MΦ transfection with miRNAs is challenging. For these reasons, it remains to be directly demonstrated whether miR-378-3p, possibly in combination with other miRNAs, regulates MΦ proliferation via Akt inhibition in vivo. We have circumstantial evidence showing that peak proliferation of MΦ after B malayi implantation precedes miR-378-3p induction and this is paralleled by a concomitant down-regulation in Akt1-expression (Figure 5). Similarly transfection of RAW264.7 cells with miR-378-3p reduced expression of PI3K/Akt-pathway molecules and negatively impacted on cellular expansion.

Beyond the putative link between miR-378-3p and IL-4–driven macrophage proliferation, this study has generated the novel and important finding that miR-378-3p is an IL-4–dependent miRNA up-regulated in MΦ both in vitro and in vivo, which targets the Akt-signaling pathway. Importantly, this finding has led to the independent observation that the local MΦ proliferation that occurs during Th2 mediated inflammation relies on Akt. This has important therapeutic implications as PI3K/Akt inhibitors are already being developed to target proliferation during cancer50,51 and thus might have off target effects on MΦ. In addition, efforts to target this pathway may generate important therapeutics to control MΦ proliferation, which is believed to exacerbate diseases such as glomerulonephritis and atherosclerosis.52,53

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yvonne Harcus for excellent technical assistance, Martin Waterfall for performing outstanding FACS sorting, and Frank Brombacher for providing the IL-4Rα−/− mice.

This work was funded by the Medical Research Council United Kingdom (MRC-UK G0600818) and the Wellcome Trust (Center for Immunity, Infection and Evolution; 082611/Z/07/Z). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: D.R. designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; S.J.J. performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and contributed vital new analytical tools; N.N.L. performed research, analyzed and interpreted data; I.J.G. analyzed and interpreted data; T.E.S. contributed vital new tools; S.D. performed research; and A.H.B. and J.E.A. contributed to data interpretation, manuscript preparation, and project supervision.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Judith E. Allen, The University of Edinburgh, Institute of Immunology and Infection Research, Ashworth Laboratories, West Mains Rd, EH9 3JT Edinburgh, United Kingdom; e-mail: j.allen@ed.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Díaz A, Allen JE. Mapping immune response profiles: the emerging scenario from helminth immunology. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(12):3319–3326. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity. 2010;32(5):593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loke P, Nair MG, Parkinson J, Guiliano D, Blaxter M, Allen JE. IL-4 dependent alternatively-activated macrophages have a distinctive in vivo gene expression phenotype. BMC Immunol. 2002;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 2008;13:453–461. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Obstacles and opportunities for understanding macrophage polarization. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89(4):557–563. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0710409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hölscher C, Hölscher A, Rückerl D, et al. The IL-27 receptor chain WSX-1 differentially regulates antibacterial immunity and survival during experimental tuberculosis. J Immunol. 2005;174(6):3534–3544. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang R, Patel D, Morris JJ, Rutschman RL, Murray PJ. Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J Immunol. 2002;169(5):2253–2263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhen T, Cidlowski JA. Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids—new mechanisms for old drugs. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1711–1723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivashkiv LB. Inflammatory signaling in macrophages: transitions from acute to tolerant and alternative activation states. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(9):2477–2481. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466(7308):835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Neill LA, Sheedy FJ, McCoy CE. MicroRNAs: the fine-tuners of Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(3):163–175. doi: 10.1038/nri2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Androulidaki A, Iliopoulos D, Arranz A, et al. The kinase Akt1 controls macrophage response to lipopolysaccharide by regulating microRNAs. Immunity. 2009;31(2):220–231. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tili E, Michaille J-J, Cimino A, et al. Modulation of miR-155 and miR-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/TNF-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5082–5089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Gazzar M, McCall CE. MicroRNAs distinguish translational from transcriptional silencing during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(27):20940–20951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.115063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang K-J, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB–dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(33):12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Nunez RT, Louafi F, Sanchez-Elsner T. The interleukin 13 (IL-13) pathway in human macrophages is modulated by microRNA-155 via direct targeting of interleukin 13 receptor alpha1 (IL13R{alpha}1). J Biol Chem. 2010;286(3):1786–1794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palma CA, Tonna EJ, Ma DF, Lutherborrow MA. MicroRNA control of myelopoiesis and the differentiation block in acute myeloid leukaemia. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(5):978–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins SJ, Ruckerl D, Cook PC, et al. Local macrophage proliferation, rather than recruitment from the blood, is a signature of TH2 inflammation. Science. 2011;332(6035):1284–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.1204351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loke P, Gallagher I, Nair MG, et al. Alternative activation is an innate response to injury that requires CD4+ T cells to be sustained during chronic infection. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):3926–3936. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smyth GK. Limma: linear models for microarray data. In: Gentleman R, Carey V, Huber W, Irizarry R, Dudoit S, editors. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions using R and Bioconductor. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5(10):R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whyte CS, Bishop ET, Ruckerl D, et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)1 is a key determinant of differential macrophage activation and function. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90(5):845–854. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1110644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eichner LJ, Perry MC, Dufour CR, et al. miR-378(*) mediates metabolic shift in breast cancer cells via the PGC-1beta/ERRgamma transcriptional pathway. Cell Metab. 2010;12(4):352–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, et al. Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1beta attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2006;4(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosser DM. The many faces of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73(2):209–212. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santhakumar D, Forster T, Laqtom NN, et al. Combined agonist-antagonist genome-wide functional screening identifies broadly active antiviral microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(31):13830–13835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008861107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun J, Ramnath RD, Tamizhselvi R, Bhatia M. Role of protein kinase C and phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt in substance P-induced proinflammatory pathways in mouse macrophages. FASEB J. 2009;23(4):997–1010. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyman O, Kovar M, Rubinstein MP, Surh CD, Sprent J. Selective stimulation of T cell subsets with antibody-cytokine immune complexes. Science. 2006;311(5769):1924–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1122927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuang G, Meng C, Guo X, et al. A novel regulator of macrophage activation: miR-223 in obesity associated adipose tissue inflammation. Circulation. 2012;125(23):2892–2903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jurkin J, Schichl YM, Koeffel R, et al. miR-146a is differentially expressed by myeloid dendritic cell subsets and desensitizes cells to TLR2-dependent activation. J Immunol. 2010;184(9):4955–4965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D'Andrea A, Ma X, Aste-Amezaga M, Paganin C, Trinchieri G. Stimulatory and inhibitory effects of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 on the production of cytokines by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: priming for IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha production. J Exp Med. 1995;181(2):537–546. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu TX, Munitz A, Rothenberg ME. MicroRNA-21 is up-regulated in allergic airway inflammation and regulates IL-12p35 expression. J Immunol. 2009;182(8):4994–5002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melgert BN, Oriss TB, Qi Z, et al. Macrophages: regulators of sex differences in asthma? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2010;42(5):595–603. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0016OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Rooij E, Quiat D, Johnson BA, et al. A family of microRNAs encoded by myosin genes governs myosin expression and muscle performance. Dev Cell. 2009;17(5):662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacKinnon A, Farnworth S, Hodkinson P, et al. Regulation of alternative macrophage activation by galectin-3. J Immunol. 2008;180(4):2650–2658. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varin A, Mukhopadhyay S, Herbein G, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages by IL-4 impairs phagocytosis of pathogens but potentiates microbial-induced signalling and cytokine secretion. Blood. 2010;115(2):353–362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou J, Song T, Gong S, Zhong M, Su G. microRNA regulation of the expression of the estrogen receptor in endometrial cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2010;3(3):387–392. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Routley CE, Ashcroft GS. Effect of estrogen and progesterone on macrophage activation during wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17(1):42–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin M, Rehani K, Jope RS, Michalek SM. Toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine production is differentially regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(8):777–784. doi: 10.1038/ni1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weichhart T, Saemann MD. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in innate immune cells: emerging therapeutic applications. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(Suppl 3):iii70–iii74. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.098459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chorro L, Sarde A, Li M, et al. Langerhans cell (LC) proliferation mediates neonatal development, homeostasis, and inflammation-associated expansion of the epidermal LC network. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):3089–3100. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davies LC, Rosas M, Smith PJ, Fraser DJ, Jones SA, Taylor PR. A quantifiable proliferative burst of tissue macrophages restores homeostatic macrophage populations after acute inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(8):2155–2164. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gagan J, Dey BK, Layer R, Yan Z, Dutta A. MICRORNA-378 targets the myogenic repressor MyoR during myoblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19431–19438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song G, Sharma AD, Roll GR, et al. MicroRNAs control hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2010;51(5):1735–1743. doi: 10.1002/hep.23547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gougelet A, Pissaloux D, Besse A, et al. Micro-RNA profiles in osteosarcoma as a predictive tool for ifosfamide response. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(3):680–690. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao C, Rajewsky K. MicroRNA control in the immune system: basic principles. Cell. 2009;136(1):26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng JQ, Lindsley CW, Cheng GZ, Yang H, Nicosia SV. The Akt/PKB pathway: molecular target for cancer drug discovery. Oncogene. 2005;24(50):7482–7492. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarker D, Reid AHM, Yap TA, de Bono JS. Targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway for the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(15):4799–4805. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Isbel NM, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Hill PA, Dowling J, Atkins RC. Local macrophage proliferation correlates with increased renal M-CSF expression in human glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(8):1638–1647. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.8.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuo CL, Murphy AJ, Sayers S, et al. Cdkn2a is an atherosclerosis modifier locus that regulates monocyte/macrophage proliferation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(11):2483–2492. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.