Abstract

Microscopic colitis may be defined as a clinical syndrome, of unknown etiology, consisting of chronic watery diarrhea, with no alterations in the large bowel at the endoscopic and radiologic evaluation. Therefore, a definitive diagnosis is only possible by histological analysis. The epidemiological impact of this disease has become increasingly clear in the last years, with most data coming from Western countries. Microscopic colitis includes two histological subtypes [collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC)] with no differences in clinical presentation and management. Collagenous colitis is characterized by a thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer that is absent in LC. The main feature of LC is an increase of the density of intra-epithelial lymphocytes in the surface epithelium. A number of pathogenetic theories have been proposed over the years, involving the role of luminal agents, autoimmunity, eosinophils, genetics (human leukocyte antigen), biliary acids, infections, alterations of pericryptal fibroblasts, and drug intake; drugs like ticlopidine, carbamazepine or ranitidine are especially associated with the development of LC, while CC is more frequently linked to cimetidine, non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and lansoprazole. Microscopic colitis typically presents as chronic or intermittent watery diarrhea, that may be accompanied by symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss and incontinence. Recent evidence has added new pharmacological options for the treatment of microscopic colitis: the role of steroidal therapy, especially oral budesonide, has gained relevance, as well as immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. The use of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α agents, infliximab and adalimumab, constitutes a new, interesting tool for the treatment of microscopic colitis, but larger, adequately designed studies are needed to confirm existing data.

Keywords: Microscopic colitis, Lymphocytic colitis, Collagenous colitis, Watery diarrhea, Immunosuppressive agents, Anti-tumor necrosis factor-α agents

INTRODUCTION

Microscopic colitis is a clinical syndrome of unknown etiology, characterized by chronic watery diarrhea in the absence of macroscopic changes in the large bowel. Once a rare diagnosis, its prevalence is now increasing, also because of the reduction of misdiagnoses, as it is included more and more often in the differential diagnosis of watery diarrhea.

As a consequence, knowledge about microscopic colitis has significantly improved in the last decade, with breakthroughs such as the recent reports of endoscopic findings or the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α agents (infliximab and adalimumab) for refractory forms of the disease.

This paper will review the state of the art of epidemiology, theories on pathogenesis, diagnostic opportunities and, in particular, therapeutic improvements for microscopic colitis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Epidemiological data on microscopic colitis (MC)[1] mainly originate from the Western world. MC accounts for 4%-13% of cases of chronic diarrhea. In Europe, collagenous colitis (CC)[2] has an incidence of 0.6-2.3/100 000 per year, and a prevalence of 10-15.7/100 000. Lymphocytic colitis (LC)[3], on the other hand, has an incidence of 3.1/100 000 per year, and a prevalence of 14.4/100 000. In particular, three European epidemiological studies have shown data on the incidence of MC in, respectively, France (0.6/100 000 per year), Sweden (1.8/100 000 per year) and Spain (1.1/100 000 per year). Recent data from North America report an incidence of 3.1-4.6/100 000 per year for CC and 5.4/100 000 per year for LC[4-7]. A Spanish study has devoted particular attention to the epidemiological differences between CC and LC: patients with CC seem to be younger than patients with LC in a statistically significant way; moreover, in these patients diagnosis occurs later than in those with LC[5]. Both pathologies are more frequent among females, but more markedly so in CC[8], though this finding is not statistically significant[9].

Actually, it may be difficult to determine the real epidemiological impact of MC for at least two reasons. First, the low specificity of signs and symptoms may cause the diagnosis to be missed or at least delayed, so that the incidence of the condition is underestimated. Secondly, until recently there were no epidemiological population studies, the scientific literature on MC mainly consisting of sporadic case reports. It is therefore unclear whether the increased incidence of MC is real or a simple consequence of the increased attention drawn to the disease[10].

PATHOGENESIS

The aetiology of MC is still unknown: a number of pathogenetic theories have been however proposed over the years, often in small or conflicting reports.

Abnormal response of luminal antigens

This group of theories is supported by multiple pieces of evidence. It has been shown that an ileostomy with a diversion of the faecal flow determines the clinical and histological resolution of the disease[11-13]; in a case in which a Hartmann’s intervention had been performed, the disease was still present in the intact proximal colon, whereas it had disappeared in the distal colon, that had undergone diversion[14].

Moreover, the benefits of drugs such as colestyramine in affected patients could be partly related to the removal of luminal toxins[15]. However, most of the patients with CC do not improve with cholestyramine; if toxins do play a role, it could therefore be less important in CC than in LC[16].

Chronic inflammation/autoimmunity

One of the most plausible pathogenetic hypotheses identifies the cause of MC in autoimmunity: a chronic inflammatory process against self antigens unleashed by an initial stimulation (infectious, chemical, or of other nature) in a predisposed individual.

This theory rests on diverse, solid items of evidence: (1), MC is more common among females, like most other autoimmune diseases; (2), in MC various markers of autoimmunity have been found, such as the antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and antiwall antibodies[17], and, in one case, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies[18]; moreover, a recent controlled study by Holstein and colleagues has found a statistically significant association of IgG ANA, antigliadin IgA, anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies IgA and IgG with with CC, but not with LC[19]; and (3), there is association between MC and various autoimmune diseases, such as thyroid diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus 1, disorders of the connective tissue, and coeliac disease[17]; this latter association has a particular importance: in about 30% of untreated celiac patients, colon biopsies show lesions identical to those of LC, and these lesions are even more evident in the cases of refractory coeliac disease[20-22]. Conversely, another study has evaluated the frequency of coeliac disease in the patients with LC: of 46 patients with MC who had undergone the screening for coeliac disease, 19 had CC and 27 had LC; of these, 4 were coeliac, and all had LC, an incidence much higher than in the general population[23]. Moreover, another study shows that the CC can be a way of presentation of the coeliac disease[24]. The possibility that the autoimmune process could be mediated by an abnormal response to luminal antigens (a notion included in the above described theory) would strengthen both theories and pave the way to linking them to each other or even merging them.

Malabsorption of biliary acids

There is conflicting evidence on the role of biliary acids. The colic infusion of biliary acids in animal models may determine a colitis[25,26], and patients with ileal resection causing malabsorption of biliary acids may have diarrhea. An association between atrophy of ileal villi and MC has also been described[27,28].

However, small studies conducted with the bile acid breath test have shown little or no evidence of malabsorption of biliary acids in patients with MC[29-31]. Other studies investigating the retention of selenium homocholyltaurine have found variable degrees of malabsorption[27,28,32], but this method is still considered uncertain and of dubious validity.

Brainerd diarrhea and other forms of infection

The term “brainerd diarrhea” indicates a watery diarrhea related to the exposure of an unknown etiologic agent (the agent that initially gave its name to the syndrome is raw milk)[33].

Brainerd diarrhea is indistinguishable from MC both clinically[34] and histologically, as it displays the same mucosal lymphocytosis, epithelial damage and collagen deposits[33,34]. Moreover, a subpopulation of patients with MC responds to antibiotic therapy[32,34-36], in particular to metronidazole. Finally, a study on an animal model has shown that human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B27/β 2 microglobulin transgenic mice, exposed to colon bacteria, develop a damage similar to that of LC[37].

A role has also been suggested of infectious agents such as Yersinia[38] and Clostridium difficile (C. difficile)[39,40]. However, this body of evidence has not yet led to identifying a specific etiologic agent.

Correlation with HLA

In general, studies on HLA haplotypes provide insubstantial information: LC has been found to be positively associated with haplotypes A1 and DRW53, DQ2 e DQ1.3, and negatively associated with A3; CC has been found to be both positively and negatively associated with DQ2[17,41,42]; other studies have found no statistically significant association between HLA haplotypes and MC[43].

Role of eosinophils

It has been shown that histamine may cause a chloride hypersecretion in the colon, and this mechanism might contribute to cause the secretory diarrhea associated with CC, through increased blood flow and a reduced sphincter activity. Moreover, a case has been reported of a patient with LC and a significant intraepithelial eosinophil infiltrate that improved with antihistaminic therapy[44]. Also, mast cells could mediate the abnormal deposition of collagen[45], as patients with systemic mastocytosis often display fibrosis[46].

Abnormalities of pericryptal fibroblasts

Physiologic production of collagen at the level of the lamina propria is ensured by a sheath of fibroblasts that surrounds lieberkuhn crypts (pericryptal fibroblasts): the collagen they produce deposits around the crypts in the basal lamina[47-50]. These fibroblasts have a myofibroblast-like behaviour: they form in the deepest part of the crypts and later climb them. During this migration they mature into collagen producing fibrocytes[50]. It has been hypothesized that abnormalities of this process could contribute to the excess deposition of collagen in CC, where collagen deposits below the basal lamina in a subepithelial position[47]. Studies have been conducted with the purpose characterize the subepithelial collagen, but findings are heterogeneous: some reports show that the subepithelial band mostly consists of collagen type VI[51,52], which finding would have pointed to a primary alteration of collagen synthesis[44]; other studies have demonstrated the presence of collagen I and III - the latter probably representing an attempt to repair after a chronic inflammatory damage[53] - and the absence of collagen type IV[44]; Günther et al[54] have shown the presence of collagen VI along with I and III.

Ischemic processes are an insufficient explanation for the differences between LC and CC: while ischemia does not result in alterations of collagen deposition, it also does not account for the inflammatory infiltrate, and no sign of ischemia has been found in LC. Moreover, abnormalities of pericryptal fibroblast similar to those of CC have been also observed in the fibrotic form of ulcerative colitis[49]. Therefore, no clear relationship has been defined so far between MC and dysfunctions of pericryptal fibroblasts.

Drug intake

Use of several drugs has been associated with the development of MC. LC has been suggested to be associated with ticlopidine[55], carbamazepine[56], ranitidine[57], vinburine[58], tardyferon[59], acarbose[60] and Cyclo 3 Fort[61]. In particular, Berrebi et al[55] have shown that ticlopidine-induced LC is accompanied by increased epithelial apoptosis - which could be either a second effect of the drug-associated damage or a consequence of the colitis itself.

The list of drugs suggested as causes of CC includes cimetidine[62], non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs[63,64], and, more recently, lansoprazole[65].

Recently, Beaugerie et al[66] have proposed a scoring system specific for drug-induced MC, based on chronological and causality criteria. Chronological criteria are based on the time between explosure to a drug and an adverse event, the evolution of the event if the therapy is interrupted, and the evolution if the therapy is restored; causality criteria are based on the exclusion of other causes of diarrhea and on specific histological findings. By combining the two sets of criteria, a score is obtained that defines the probability that a drug has caused MC: 0, not related; 1, doubtful; 2, possible; 3, likely; 4, almost definite.

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Definitive diagnosis of MC rests on histological examination, which is necessary both to rule out other possible causes of chronic diarrhea and to distinguish between LC and CC.

The diagnosis of LC is based on the following features. First, an increase of the density of intra-epithelial lymphocytes (IEL) in the surface epithelium. Physiologically, IEL of the colonic mucosa are less than 5 per 100 epithelial cells, while in LC they are at least 25 per 100 surface epithelial cells[3,15,67], typically CD8+, carrying the αβ T-cell receptor[68-70] and expressing the human mucosal lymphocyte antigen, specific for intestinal lymphocytes[68,71,72]; lymphocytosis in the crypt epithelium is also seen, but is less constant[3].

Rarely, an infiltrate of eosinophils in the epithelium can also be found, and in a few reports neutrophils have been described, considered as a sign of acute stage of colitis[73].

Second, an inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria, with prevalence of mononuclear cells such as lymphocytes and plasma cells, but with the sporadic presence of eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages and neutrophils (very rare); unlike those in the surface epithelium, lymphocytes of the lamina propria are mostly CD4+[68,69]. It has been argued that lymphocytosis in the epithelium and in the lamina propria could be a histological response to a primum movens inflammatory process, rather than a primitive immunological dysfunction[16].

Third, surface epithelial damage, manifested with flattening and degeneration of the epithelial cells (with features such as vacuolization of cytoplasm, nuclear irregularity, karyorrhexis and pyknosis) and focal loss and detachment of the epithelium - these features being more common in CC-[3,74,75]. There is also a minimal distortion of the structure of the crypts, but no crypt abscesses and granulomas[76]. Moreover, active cryptitis has been reported by Gledhill et al[49] in 41% of subjects with LC and in 29% with CC.

CC is characterized by a thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer that is absent in LC. The collagen band appears extremely eosinophilic in routine hematoxylin-eosin staining, but is better recognizable with Masson’s trichrome staining; tenascin immunohistochemical stain appears to further improve sensitivity[77,78].

In the healthy colon, the subepithelial collagen band is thinner than 3 μm[48]. The diagnostic criterion for CC has been proposed to be a thickness of at least 10 μm by some authors[15,32,74], at least 7 μm by others[29,49,76]. However, it is plausible that in most cases the collagen band reaches even 100 μm[15]. According to Lazenby et al[3], the thickness of the collagen band alone is neither sufficient nor necessary for the diagnosis of CC: there are also some qualitative abnormalities, such as entrapment of red blood cells and cells of inflammation in the collagen band, and an irregular appearance of the inferior edge of the basement membrane, because of collagen bundles extending into the lamina propria. Some studies report a decreasing gradient of presence of intraepithelial lymphocytes and thickness of collagen band from the cecum to the rectum[69,76], others suggest that biopsies of the transverse colon give the best chance of diagnosis[79], but as a general rule left-sided colonic biopsies, easily carried out with a flexible rectosigmoidoscope, are considered sufficient for the diagnosis of MC; if descending colon biopsies are not diagnostic and clinical suspicion is strong, a colonoscopy with random biopsies can be performed.

Studies of immunohistochemistry have shown that the collagen band consists basically of type III collagen - the subtype produced with repair functions - pointing to a reactive origin (the normal basement membrane mainly consists of fibronectin, laminin and type IV collagen)[80].

The histological features of MC are not specific: CC-like findings have been reported in colon cancer, carcinoid lesions, hyperplastic polyps, C. difficile infection, Crohn’s colitis, constipation and healthy people[48,76,80-87], while features resembling LC have been described in human immunodeficiency virus, Crohn’s disease, healthy people[67,81,88,89].

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

MC typically presents as chronic or intermittent watery diarrhea. The colon is normal both on endoscopic investigations and on imaging, so that a conclusive diagnosis can only be reached through biopsy and histological examination[90]. Lately, however, endoscopic findings have been described in patients with MC (as carefully reviewed by Koulaouzidis et al[91]), especially CC, such as colonic mucosal defects (mucosal tears or fractures)[92-94] and alterations of vascular patterns, e.g. crowding of vessels, with dilated, circling or winding blood capillaries[95]. Endomicroscopy[96] and indigo carmine chromoendoscopy[97] for the endoscopic diagnosis of MC have also been tested.

The severity of symptoms is variable: up to 22% of patients have > 10 bowel movements per day and up to 27% having nocturnal diarrhea[32].

Diarrhea may be accompanied by symptoms such as abdominal pain, weight loss, incontinence[88,98-103]. MC has been associated with a significant impairment of the overall quality of life, comparable to if not worse than that of other severe gastroenterological conditions such as anal fissures, severe chronic constipation, faecal incontinence[104].

MC may be associated with an increased risk of lymphoma[105,106], and, in women, lung cancer, even though the overall risk of malignancy and mortality is not different from the general population[107]. Cases of MC as paraneoplastic manifestation have been described, e.g. in colon cancer[108].

The natural course of the disease is extremely variable. The rate of spontaneous symptomatic remission after many years was reported as varying between 60% and 93% in LC[88,109] and as much as from 2% to 92% in CC[32,110-112]. More informative data come from studies that have analysed the smaller timeframe of 6/8 wk, highlighting a general tendency to lower response rates to placebo for CC (12%-20%)[109-111] than for LC (48%)[112]. These findings suggest that LC might have an intrinsically higher tendency to spontaneous remission than CC.

TREATMENT

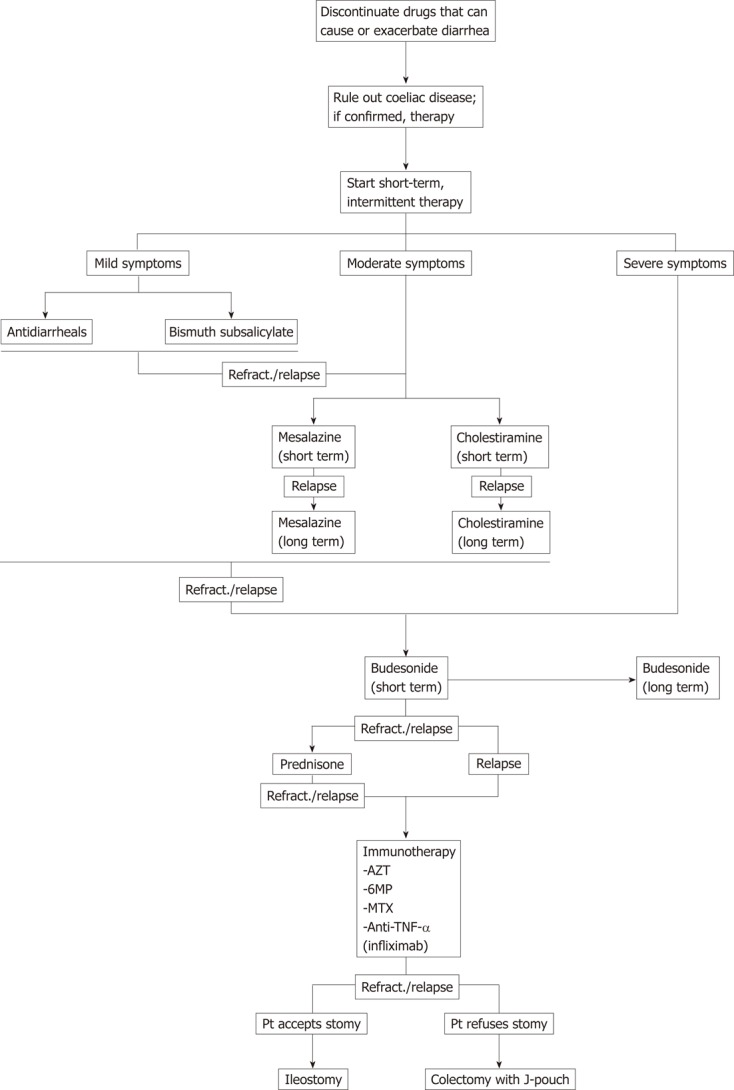

More evidence is available on the treatment of CC than LC, but there is general agreement that there is no reason why the approach to their treatment should differ[113]; available studies also confirm that therapies that proved effective in one tend to be confirmed as effective for the other as well[112]. Another accepted guideline for medical therapy, based on the finding that MC has a high rate of spontaneous remission and remission after therapy, is that intermittent therapy should be favoured and that long-term therapy should only be considered when relapses or refractory symptoms leave no other choice[114]. Therapeutic algorithms that combine available therapies in a meaningful way were proposed in 2003[10], 2008[113] and 2011[90].

Proved association of MC with a range of drugs and with coeliac sprue suggests that both these etiologies are excluded before any medical therapy is initiated. Since patient with coeliac sprue presenting as MC tend to be negative for the typical immune markers of coeliac sprue, a small intestine biopsy remains the most reliable way of ruling it out[115,116]; however, the invasive nature of the test makes it advisable to use it only for patients with a clinical situation strongly suggesting coeliac disease or with a previously diagnosed MC that has already proved refractory to therapy[90].

A number of medical treatments have been attempted in patients with MC. A general consensus persists as to the use of traditional antidiarrhoic agents (loperamide, diphenoxylate) as first-line medical therapy, especially for patients with mild symptoms. The main options to be used as second line therapy are represented by bismuth subsalicylate[117-119] and mesalazine, with or without colestyramine[120]. Despite the efficacy of both is proved by trials, bismuth subsalicylate presents the drawback that it is not suitable for long-term therapy because of its unfavourable side effects profile. The association mesalazine-cholestyramine, on the other end, is made physiologically reasonable by previous evidence on the association between MC and bile acids malabsorption[121,122], and probably deserved to be further investigated.

There is now overwhelming evidence proving the efficacy of short-term therapy with oral budesonide in MC, a corticosteroid that is quickly metabolized by the liver and has therefore limited side effects compared to other steroids[109-112]. Still, the overall adverse effects profile and the high risk of steroid dependency impose that this option be kept for second line or third line after the above mentioned agents, or at the very least that it only be considered as first line in cases with severe symptoms. The efficacy of prednisone has also been assessed[114,123], but because of its intrinsically severe adverse effects profile it should only be used in patients refractory to budesonide, if at all.

Studies on immunosuppressive therapy for refractory MC have made their appearance since budesonide was first proposed as a treatment, mainly because of the similarity between MC and inflammatory bowel diseases. The first ones to be studied were azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine[124-126], so that were recognized as a valid choice for steroid refractory MC early on[127]. Later on, methotrexate was also proved to be effective[128].

In patients refractory to all medical therapy, the surgical option should be considered[125]. A number of interventions, which substantially overlap with the surgical approaches to the inflammatory bowel disease, have shown to have a potential of leading to a complete resolution of the symptoms[13,14,129].

Boswellia serrata extract and probiotics have been found ineffective by one radionuclide computed tomography each[130,131] so that they have since not been proposed in any therapeutic algorithm or reconsidered for subsequent trials.

The most recent developments appear to be focused on two lines of research. The first is the use of low-dosage budesonide as maintenance therapy; this approach appears to be more clinically viable than expected[132,133] and has been deemed as promising[134]. The second is the use of a new category of immunosuppressive agents, anti-TNF-α agents, already used with great results for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases: good results in therapies with both infliximab and adalimumab have been recently reported in experiences of limited size[135-137], providing a valid rationale for a future larger controlled study.

Based on the accepted body of evidence on MC in combination with the most recent developments, we suggest a systematic treatment algorithm for MC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A proposed algorithm for the systemic treatment of microscopic colitis. TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; Refract.: Refractory; AZT: Azathioprine; MP: Mercaptopurine; MTX: Methotrexate; Pt: Patient.

CONCLUSION

Microscopic colitis is a quite common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, whose epidemiological impact has grown in the last years. Colon biopsies are required for the definitive diagnosis, and for the histological characterisation of the two subtypes of the disease (CC and LC), whose clinical features and management do not present however differences.

Over the last years, a series of new pharmacological agents for the treatment of MC has been proposed. The role of steroidal therapy, especially regarding the use of oral budesonide, has gained relevance, as well as immunosuppressive agents as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Few and very recent evidences has introduced anti-TNF-α agents (infliximab and adalimumab) as the possible cutting-edge for the treatment of MC, but larger and adequately designed studies are required to confirm these data.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Dr. Anastasios Koulaouzidis, MD, MRCP, FEBG, Endoscopy Unit, Centre for Liver and Digestive Disorders, Endoscopy Unit, 51 Little France Crescent, Edinburgh EH16 4SA, United Kingdom; Dr. Eldon A Shaffer, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, 3330 Hospital Dr NW, Calgary T2N4N1, Canada

S- Editor Wu X L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

References

- 1.Read NW, Krejs GJ, Read MG, Santa Ana CA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Chronic diarrhea of unknown origin. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:264–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindström CG. ‘Collagenous colitis’ with watery diarrhoea--a new entity? Pathol Eur. 1976;11:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH, Giardiello FM, Jessurun J, Bayless TM. Lymphocytic (“microscopic”) colitis: a comparative histopathologic study with particular reference to collagenous colitis. Hum Pathol. 1989;20:18–28. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pardi DS, Loftus EV, Smyrk TC, Kammer PP, Tremaine WJ, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, Sandborn WJ. The epidemiology of microscopic colitis: a population based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gut. 2007;56:504–508. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.105890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández-Bañares F, Salas A, Forné M, Esteve M, Espinós J, Viver JM. Incidence of collagenous and lymphocytic colitis: a 5-year population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:418–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohr J, Tysk C, Eriksson S, Järnerot G. Collagenous colitis in Orebro, Sweden, an epidemiological study 1984-1993. Gut. 1995;37:394–397. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.3.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raclot G, Queneau PE, Ottignon Y, Angonin R, Monnot B, Leroy M, Devalland C, Girard V, Carbillet JP, Carayon P. Incidence of collagenous colitis: A retrospective study in the east of France. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:A23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pardi DS, Kelly CP. Microscopic colitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1155–1165. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández-Bañares F, Salas A, Esteve M, Espinós J, Forné M, Viver JM. Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis. evaluation of clinical and histological features, response to treatment, and long-term follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:340–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loftus EV. Microscopic colitis: epidemiology and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:S31–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.amjgastroenterol.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veress B, Löfberg R, Bergman L. Microscopic colitis syndrome. Gut. 1995;36:880–886. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Järnerot G, Tysk C, Bohr J, Eriksson S. Collagenous colitis and fecal stream diversion. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:449–455. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams RA, Gelfand DV. Total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis to successfully treat a patient with collagenous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2147. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Järnerot G, Bohr J, Tysk C, Eriksson S. Faecal stream diversion in patients with collagenous colitis. Gut. 1996;38:154–155. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.1.154-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tagkalidis P, Bhathal P, Gibson P. Microscopic colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:236–248. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tremaine WJ. Collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:245–249. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200004000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giardiello FM, Lazenby AJ, Bayless TM, Levine EJ, Bias WB, Ladenson PW, Hutcheon DF, Derevjanik NL, Yardley JH. Lymphocytic (microscopic) colitis. Clinicopathologic study of 18 patients and comparison to collagenous colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1730–1738. doi: 10.1007/BF01540051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freeman HJ. Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in collagenous or lymphocytic colitis with or without celiac disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1997;11:417–420. doi: 10.1155/1997/210856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holstein A, Burmeister J, Plaschke A, Rosemeier D, Widjaja A, Egberts EH. Autoantibody profiles in microscopic colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1016–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.04027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolber R, Owen D, Freeman H. Colonic lymphocytosis in patients with celiac sprue. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:1092–1096. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90144-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DuBois RN, Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH, Hendrix TR, Bayless TM, Giardiello FM. Lymphocytic enterocolitis in patients with ‘refractory sprue’. JAMA. 1989;262:935–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fine KD, Lee EL, Meyer RL. Colonic histopathology in untreated celiac sprue or refractory sprue: is it lymphocytic colitis or colonic lymphocytosis? Hum Pathol. 1998;29:1433–1440. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matteoni CA, Goldblum JR, Wang N, Brzezinski A, Achkar E, Soffer EE. Celiac disease is highly prevalent in lymphocytic colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:225–227. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman HJ. Collagenous colitis as the presenting feature of biopsy-defined celiac disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:664–668. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000135363.12794.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chadwick VS, Gaginella TS, Carlson GL, Debongnie JC, Phillips SF, Hofmann AF. Effect of molecular structure on bile acid-induced alterations in absorptive function, permeability, and morphology in the perfused rabbit colon. J Lab Clin Med. 1979;94:661–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breuer NF, Rampton DS, Tammar A, Murphy GM, Dowling RH. Effect of colonic perfusion with sulfated and nonsulfated bile acids on mucosal structure and function in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:969–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis FW, Warren GH, Goff JS. Collagenous colitis with involvement of terminal ileum. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1161–1163. doi: 10.1007/BF01297466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marteau P, Lavergne-Slove A, Lemann M, Bouhnik Y, Bertheau P, Becheur H, Galian A, Rambaud JC. Primary ileal villous atrophy is often associated with microscopic colitis. Gut. 1997;41:561–564. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fausa O, Foerster A, Hovig T. Collagenous colitis. A clinical, histological, and ultrastructural study. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1985;107:8–23. doi: 10.3109/00365528509099747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kingham JG, Levison DA, Ball JA, Dawson AM. Microscopic colitis-a cause of chronic watery diarrhoea. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;285:1601–1604. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6355.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giardiello FM, Bayless TM, Jessurun J, Hamilton SR, Yardley JH. Collagenous colitis: physiologic and histopathologic studies in seven patients. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:46–49. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohr J, Tysk C, Eriksson S, Abrahamsson H, Järnerot G. Collagenous colitis: a retrospective study of clinical presentation and treatment in 163 patients. Gut. 1996;39:846–851. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.6.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osterholm MT, MacDonald KL, White KE, Wells JG, Spika JS, Potter ME, Forfang JC, Sorenson RM, Milloy PT, Blake PA. An outbreak of a newly recognized chronic diarrhea syndrome associated with raw milk consumption. JAMA. 1986;256:484–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryant DA, Mintz ED, Puhr ND, Griffin PM, Petras RE. Colonic epithelial lymphocytosis associated with an epidemic of chronic diarrhea. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1102–1109. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zins BJ, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ. Collagenous and lymphocytic colitis: subject review and therapeutic alternatives. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1394–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardi DS, Ramnath VR, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJl. Treatment outcomes in lymphocytic colitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120 Suppl 1:A13. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rath HC, Herfarth HH, Ikeda JS, Grenther WB, Hamm TE, Balish E, Taurog JD, Hammer RE, Wilson KH, Sartor RB. Normal luminal bacteria, especially Bacteroides species, mediate chronic colitis, gastritis, and arthritis in HLA-B27/human beta2 microglobulin transgenic rats. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:945–953. doi: 10.1172/JCI118878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bohr J, Nordfelth R, Järnerot G, Tysk C. Yersinia species in collagenous colitis: a serologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:711–714. doi: 10.1080/00365520212509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Byrne MF, McVey G, Royston D, Patchett SE. Association of Clostridium difficile infection with collagenous colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:285. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erim T, Alazmi WM, O’Loughlin CJ, Barkin JS. Collagenous colitis associated with Clostridium difficile: a cause effect? Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1374–1375. doi: 10.1023/a:1024127713979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giardiello FM, Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH, Bias WB, Johnson J, Alianiello RG, Bedine MS, Bayless TM. Increased HLA A1 and diminished HLA A3 in lymphocytic colitis compared to controls and patients with collagenous colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:496–499. doi: 10.1007/BF01307569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fine KD, Do K, Schulte K, Ogunji F, Guerra R, Osowski L, McCormack J. High prevalence of celiac sprue-like HLA-DQ genes and enteropathy in patients with the microscopic colitis syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1974–1982. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sylwestrowicz T, Kelly JK, Hwang WS, Shaffer EA. Collagenous colitis and microscopic colitis: the watery diarrhea-colitis syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:763–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baum CA, Bhatia P, Miner PB. Increased colonic mucosal mast cells associated with severe watery diarrhea and microscopic colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1462–1465. doi: 10.1007/BF01538086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molas GJ, Flejou JF, Potet F. Microscopic colitis, collagenous colitis, and mast cells. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:920–921. doi: 10.1007/BF01536812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brunning RD, McKenna RW, Rosai J, Parkin JL, Risdall R. Systemic mastocytosis. Extracutaneous manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:425–438. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang WS, Kelly JK, Shaffer EA, Hershfield NB. Collagenous colitis: a disease of pericryptal fibroblast sheath? J Pathol. 1986;149:33–40. doi: 10.1002/path.1711490108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gledhill A, Cole FM. Significance of basement membrane thickening in the human colon. Gut. 1984;25:1085–1088. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.10.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balázs M, Egerszegi P, Vadász G, Kovács A. Collagenous colitis: an electron microscopic study including comparison with the chronic fibrotic stage of ulcerative colitis. Histopathology. 1988;13:319–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1988.tb02042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaye GI, Lane N, Pascal RR. Colonic pericryptal fibroblast sheath: replication, migration, and cytodifferentiation of a mesenchymal cell system in adult tissue. II. Fine structural aspects of normal rabbit and human colon. Gastroenterology. 1968;54:852–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duerr RH, Targan SR, Landers CJ, Sutherland LR, Shanahan F. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in ulcerative colitis. Comparison with other colitides/diarrheal illnesses. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1590–1596. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90657-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aigner T, Neureiter D, Müller S, Küspert G, Belke J, Kirchner T. Extracellular matrix composition and gene expression in collagenous colitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:136–143. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stampfl DA, Friedman LS. Collagenous colitis: pathophysiologic considerations. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:705–711. doi: 10.1007/BF01311225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Günther U, Schuppan D, Bauer M, Matthes H, Stallmach A, Schmitt-Gräff A, Riecken EO, Herbst H. Fibrogenesis and fibrolysis in collagenous colitis. Patterns of procollagen types I and IV, matrix-metalloproteinase-1 and -13, and TIMP-1 gene expression. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:493–503. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berrebi D, Sautet A, Flejou JF, Dauge MC, Peuchmaur M, Potet F. Ticlopidine induced colitis: a histopathological study including apoptosis. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:280–283. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.4.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mahajan L, Wyllie R, Goldblum J. Lymphocytic colitis in a pediatric patient: a possible adverse reaction to carbamazepine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2126–2127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beaugerie L, Patey N, Brousse N. Ranitidine, diarrhoea, and lymphocytic colitis. Gut. 1995;37:708–711. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.5.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chauveau E, Prignet JM, Carloz E, Duval JL, Gilles B. [Lymphocytic colitis likely attributable to use of vinburnine (Cervoxan)] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1998;22:362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bouchet-Laneuw F, Deplaix P, Dumollard JM, Barthélémy C, Weber FX, Védrines P, Audigier JC. [Chronic diarrhea following ingestion of Tardyferon associated with lymphocytic colitis] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1997;21:83–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piche T, Raimondi V, Schneider S, Hébuterne X, Rampal P. Acarbose and lymphocytic colitis. Lancet. 2000;356:1246. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beaugerie L, Luboinski J, Brousse N, Cosnes J, Chatelet FP, Gendre JP, Le Quintrec Y. Drug induced lymphocytic colitis. Gut. 1994;35:426–428. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duncan HD, Talbot IC, Silk DB. Collagenous colitis and cimetidine. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:819–820. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199708000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riddell RH, Tanaka M, Mazzoleni G. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as a possible cause of collagenous colitis: a case-control study. Gut. 1992;33:683–686. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.5.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giardiello FM, Hansen FC, Lazenby AJ, Hellman DB, Milligan FD, Bayless TM, Yardley JH. Collagenous colitis in setting of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and antibiotics. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:257–260. doi: 10.1007/BF01536772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilcox GM, Mattia A. Collagenous colitis associated with lansoprazole. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:164–166. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beaugerie L, Pardi DS. Review article: drug-induced microscopic colitis - proposal for a scoring system and review of the literature. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang N, Dumot JA, Achkar E, Easley KA, Petras RE, Goldblum JR. Colonic epithelial lymphocytosis without a thickened subepithelial collagen table: a clinicopathologic study of 40 cases supporting a heterogeneous entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1068–1074. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Armes J, Gee DC, Macrae FA, Schroeder W, Bhathal PS. Collagenous colitis: jejunal and colorectal pathology. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:784–787. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.9.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mosnier JF, Larvol L, Barge J, Dubois S, De La Bigne G, Hénin D, Cerf M. Lymphocytic and collagenous colitis: an immunohistochemical study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:709–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lazenby AJ, Alaniello RG, Fox WM, Giardiello FM, Yardley JH. T cell receptors in collagenous and lymphocytic colitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:A459. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bogomoletz WV, Fléjou JF. Newly recognized forms of colitis: collagenous colitis, microscopic (lymphocytic) colitis, and lymphoid follicular proctitis. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1991;8:178–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cerf-Bensussan N, Jarry A, Brousse N, Lisowska-Grospierre B, Guy-Grand D, Griscelli C. A monoclonal antibody (HML-1) defining a novel membrane molecule present on human intestinal lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1279–1285. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kingham JG, Levison DA, Morson BC, Dawson AM. Collagenous colitis. Gut. 1986;27:570–577. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.5.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baert F, Wouters K, D’Haens G, Hoang P, Naegels S, D’Heygere F, Holvoet J, Louis E, Devos M, Geboes K. Lymphocytic colitis: a distinct clinical entity? A clinicopathological confrontation of lymphocytic and collagenous colitis. Gut. 1999;45:375–381. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jawhari A, Talbot IC. Microscopic, lymphocytic and collagenous colitis. Histopathology. 1996;29:101–110. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jessurun J, Yardley JH, Giardiello FM, Hamilton SR, Bayless TM. Chronic colitis with thickening of the subepithelial collagen layer (collagenous colitis): histopathologic findings in 15 patients. Hum Pathol. 1987;18:839–848. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anagnostopoulos I, Schuppan D, Riecken EO, Gross UM, Stein H. Tenascin labelling in colorectal biopsies: a useful marker in the diagnosis of collagenous colitis. Histopathology. 1999;34:425–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Müller S, Neureiter D, Stolte M, Verbeke C, Heuschmann P, Kirchner T, Aigner T. Tenascin: a sensitive and specific diagnostic marker of minimal collagenous colitis. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:435–441. doi: 10.1007/s004280000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Offner FA, Jao RV, Lewin KJ, Havelec L, Weinstein WM. Collagenous colitis: a study of the distribution of morphological abnormalities and their histological detection. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:451–457. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(99)90122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Flejou JF, Grimaud JA, Molas G, Baviera E, Potet F. Collagenous colitis. Ultrastructural study and collagen immunotyping of four cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:977–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johansen A, Anstad K. [Norwegian Nurses’ Association’s district presidents: ties between the central organization and the membership] Sykepleien. 1976;63:522–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goff JS, Barnett JL, Pelke T, Appelman HD. Collagenous colitis: histopathology and clinical course. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gubbins GP, Dekovich AA, Ma CK, Batra SK. Collagenous colitis: report of nine cases and review of the literature. South Med J. 1991;84:33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nussinson E, Samara M, Vigder L, Shafer I, Tzur N. Concurrent collagenous colitis and multiple ileal carcinoids. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:1040–1044. doi: 10.1007/BF01536004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gardiner GW, Goldberg R, Currie D, Murray D. Colonic carcinoma associated with an abnormal collagen table. Collagenous colitis. Cancer. 1984;54:2973–2977. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841215)54:12<2973::aid-cncr2820541227>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang HH, Owings DV, Antonioli DA, Goldman H. Increased subepithelial collagen deposition is not specific for collagenous colitis. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Leigh C, Elahmady A, Mitros FA, Metcalf A, al-Jurf A. Collagenous colitis associated with chronic constipation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17:81–84. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mullhaupt B, Güller U, Anabitarte M, Güller R, Fried M. Lymphocytic colitis: clinical presentation and long term course. Gut. 1998;43:629–633. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Levison DA, Lazenby AJ, Yardley JH. Microscopic colitis cases revisited. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1594–1596. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90194-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yen EF, Pardi DS. Review article: Microscopic colitis--lymphocytic, collagenous and ‘mast cell’ colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:21–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koulaouzidis A, Saeed AA. Distinct colonoscopy findings of microscopic colitis: not so microscopic after all? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4157–4165. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i37.4157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wickbom A, Lindqvist M, Bohr J, Ung KA, Bergman J, Eriksson S, Tysk C. Colonic mucosal tears in collagenous colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:726–729. doi: 10.1080/00365520500453473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Koulaouzidis A, Henry JA, Saeed AA. Mucosal tears can occur spontaneously in collagenous colitis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:549. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dunzendorfer T, Wilkins S, Johnson R. Mucosal tear in collagenous colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:e57. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Couto G, Bispo M, Barreiro P, Monteiro L, Matos L. Unique endoscopy findings in collagenous colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1186–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kiesslich R, Hoffman A, Goetz M, Biesterfeld S, Vieth M, Galle PR, Neurath MF. In vivo diagnosis of collagenous colitis by confocal endomicroscopy. Gut. 2006;55:591–592. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.084970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suzuki G, Mellander MR, Suzuki A, Rubio CA, Lambert R, Björk J, Schmidt PT. Usefulness of colonoscopic examination with indigo carmine in diagnosing microscopic colitis. Endoscopy. 2011;43:1100–1104. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1291423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Madisch A, Bethke B, Stolte M, Miehlke S. Is there an association of microscopic colitis and irritable bowel syndrome--a subgroup analysis of placebo-controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6409. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i41.6409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Madisch A, Miehlke S, Lindner M, Bethke B, Stolte M. Clinical course of collagenous colitis over a period of 10 years. Z Gastroenterol. 2006;44:971–974. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-926963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bonner GF, Petras RE, Cheong DM, Grewal ID, Breno S, Ruderman WB. Short- and long-term follow-up of treatment for lymphocytic and collagenous colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:85–91. doi: 10.1002/ibd.3780060204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bonderup OK, Folkersen BH, Gjersøe P, Teglbjaerg PS. Collagenous colitis: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:493–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Madisch A, Heymer P, Voss C, Wigginghaus B, Bästlein E, Bayerdörffer E, Meier E, Schimming W, Bethke B, Stolte M, et al. Oral budesonide therapy improves quality of life in patients with collagenous colitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:312–316. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0660-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hjortswang H, Tysk C, Bohr J, Benoni C, Kilander A, Larsson L, Vigren L, Ström M. Defining clinical criteria for clinical remission and disease activity in collagenous colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1875–1881. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sailer M, Bussen D, Debus ES, Fuchs KH, Thiede A. Quality of life in patients with benign anorectal disorders. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1716–1719. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Edwards DB. Collagenous colitis and histiocytic lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:260–261. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-3-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ouyahya F, Michenet P, Gargot D, Breteau N, Buzacoux J, Legoux JL. [Lymphocytic colitis, followed by collagenous colitis, associated with mycosis fungoides-type T-cell lymphoma] Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1993;17:976–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chan JL, Tersmette AC, Offerhaus GJ, Gruber SB, Bayless TM, Giardiello FM. Cancer risk in collagenous colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:40–43. doi: 10.1097/00054725-199902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Freeman HJ, Berean KW. Resolution of paraneoplastic collagenous enterocolitis after resection of colon cancer. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:357–360. doi: 10.1155/2006/893928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Miehlke S, Heymer P, Bethke B, Bästlein E, Meier E, Bartram HP, Wilhelms G, Lehn N, Dorta G, DeLarive J, et al. Budesonide treatment for collagenous colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:978–984. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bonderup OK, Hansen JB, Birket-Smith L, Vestergaard V, Teglbjaerg PS, Fallingborg J. Budesonide treatment of collagenous colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial with morphometric analysis. Gut. 2003;52:248–251. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Baert F, Schmit A, D’Haens G, Dedeurwaerdere F, Louis E, Cabooter M, De Vos M, Fontaine F, Naegels S, Schurmans P, et al. Budesonide in collagenous colitis: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial with histologic follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:20–25. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.30295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Miehlke S, Madisch A, Karimi D, Wonschik S, Kuhlisch E, Beckmann R, Morgner A, Mueller R, Greinwald R, Seitz G, et al. Budesonide is effective in treating lymphocytic colitis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2092–2100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chande N. Microscopic colitis: an approach to treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:686–688. doi: 10.1155/2008/671969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chande N, McDonald JW, Macdonald JK. Interventions for treating lymphocytic colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006096. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006096.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Bohr J, Tysk C, Yang P, Danielsson D, Järnerot G. Autoantibodies and immunoglobulins in collagenous colitis. Gut. 1996;39:73–76. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ramzan NN, Shapiro MS, Pasha TM, Corn T, Olden KW, Braaten JK, Hentz J. Is celiac disease associated with microscopic and collagenous colitis? Gastroenterology. 2001;120:A684. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fine KD, Lee EL. Efficacy of open-label bismuth subsalicylate for the treatment of microscopic colitis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70629-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fine KD, Ogunji F, Lee EL, Lafon G, Tanzi M. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of bismuth subsalicylate for microscopic colitis. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:A880. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Amaro R, Poniecka A, Rogers AI. Collagenous colitis treated successfully with bismuth subsalicylate. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1447–1450. doi: 10.1023/a:1005584810298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Calabrese C, Fabbri A, Areni A, Zahlane D, Scialpi C, Di Febo G. Mesalazine with or without cholestyramine in the treatment of microscopic colitis: randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:809–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ung KA, Gillberg R, Kilander A, Abrahamsson H. Role of bile acids and bile acid binding agents in patients with collagenous colitis. Gut. 2000;46:170–175. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.2.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fernandez-Bañares F, Esteve M, Salas A, Forné TM, Espinos JC, Martín-Comin J, Viver JM. Bile acid malabsorption in microscopic colitis and in previously unexplained functional chronic diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2231–2238. doi: 10.1023/a:1011927302076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Munck LK, Kjeldsen J, Philipsen E, Fischer Hansen B. Incomplete remission with short-term prednisolone treatment in collagenous colitis: a randomized study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:606–610. doi: 10.1080/00365520310002210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Deslandres C, Moussavou-Kombilia JB, Russo P, Seidman EG. Steroid-resistant lymphocytic enterocolitis and bronchitis responsive to 6-mercaptopurine in an adolescent. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:341–346. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199709000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pardi DS, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ. Treatment of refractory microscopic colitis with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1483–1484. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Vennamaneni SR, Bonner GF. Use of azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for treatment of steroid-dependent lymphocytic and collagenous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2798–2799. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pardi DS, Ramnath VR, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Sandborn WJ. Lymphocytic colitis: clinical features, treatment, and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2829–2833. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Riddell J, Hillman L, Chiragakis L, Clarke A. Collagenous colitis: oral low-dose methotrexate for patients with difficult symptoms: long-term outcomes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1589–1593. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Varghese L, Galandiuk S, Tremaine WJ, Burgart LJ. Lymphocytic colitis treated with proctocolectomy and ileal J-pouch-anal anastomosis: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:123–126. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6126-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wildt S, Munck LK, Vinter-Jensen L, Hanse BF, Nordgaard-Lassen I, Christensen S, Avnstroem S, Rasmussen SN, Rumessen JJ. Probiotic treatment of collagenous colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. Lactis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:395–401. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000218763.99334.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Madisch A, Miehlke S, Eichele O, Mrwa J, Bethke B, Kuhlisch E, Bästlein E, Wilhelms G, Morgner A, Wigginghaus B, et al. Boswellia serrata extract for the treatment of collagenous colitis. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1445–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0364-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Miehlke S, Madisch A, Bethke B, Morgner A, Kuhlisch E, Henker C, Vogel G, Andersen M, Meier E, Baretton G, et al. Oral budesonide for maintenance treatment of collagenous colitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1510–1516. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Bonderup OK, Hansen JB, Teglbjaerg PS, Christensen LA, Fallingborg JF. Long-term budesonide treatment of collagenous colitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gut. 2009;58:68–72. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.156513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pardi DS. After budesonide, what next for collagenous colitis? Gut. 2009;58:3–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Aram G, Bayless TM, Chen ZM, Montgomery EA, Donowitz M, Giardiello FM. Refractory lymphocytic enterocolitis and tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Esteve M, Mahadevan U, Sainz E, Rodriguez E, Salas A, Fernández-Bañares F. Efficacy of anti-TNF therapies in refractory severe microscopic colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:612–618. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Münch A, Ignatova S, Ström M. Adalimumab in budesonide and methotrexate refractory collagenous colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:59–63. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.639079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]