Abstract

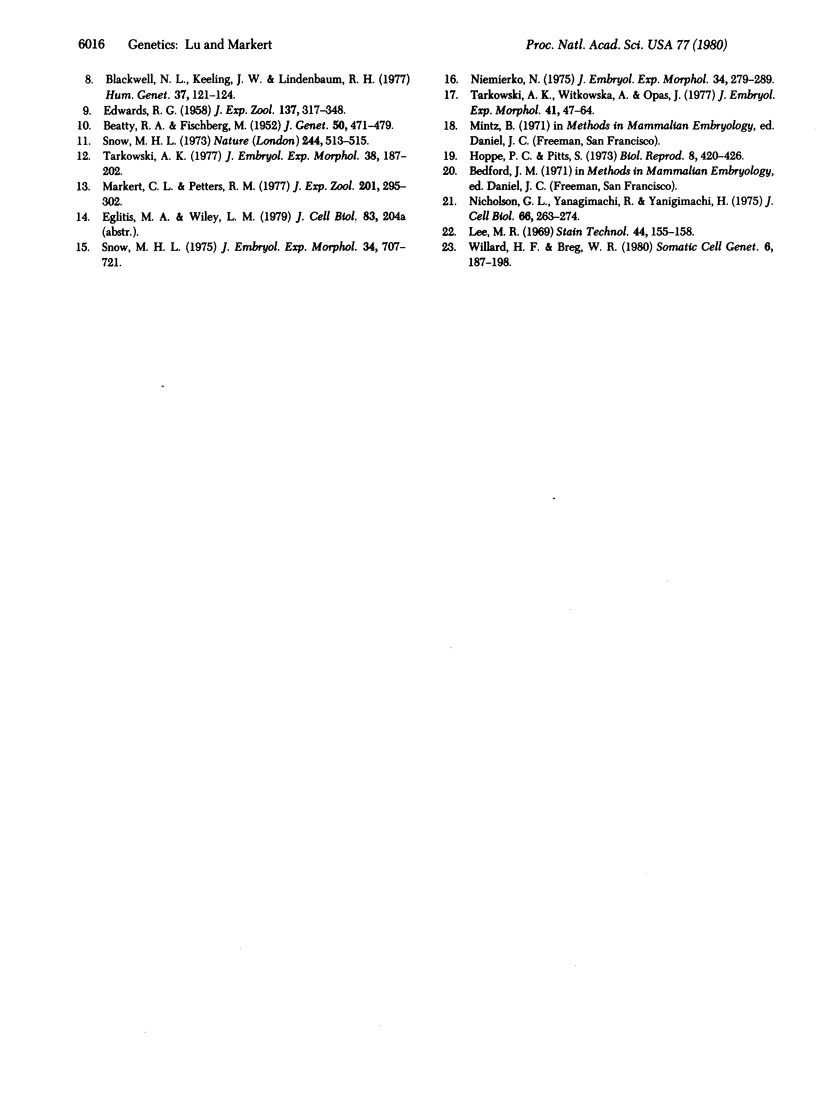

Tetraploid mouse embryos were produced by cytochalasin B treatment. These embryos usually die before completion of embryonic development and are abnormal morphologically and physiologically. The tetraploid embryos can be rescued to develop to maturity by aggregating them with normal diploid embryos to produce diploid/tetraploid chimeric mice. The diploid/tetraploid chimeric embryos are frequently abnormal: the larger the proportion of tetraploid cells, the greater the abnormality. By karyotype analysis and by the use of appropriate pigment cell markers, we have demonstrated that two of our surviving chimeras are in fact diploid/tetraploid chimeras. One surviving chimera is retarded in growth and displays neurological abnormalities. The coat color chimerism suggests that this chimera is about 50% tetraploid. Another chimera with about 10% tetraploid pigment cells in the coat is only slightly retarded in growth and is a fertile male. Tetraploid cells are distributed in many, if not all, tissues of embryos but evidently are physiologically inadequate to support completely normal development and function in the absence of substantial numbers of normal diploid cells.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blackwell N. L., Keeling J. W., Lindenbaum R. H. Dispermic origin of a 69,XXY triploid. Hum Genet. 1977 Jun 10;37(1):121–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00293783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDWARDS R. G. Colchicine-induced heteroploidy in the mouse. I. The induction of triploidy by treatment of the gametes. J Exp Zool. 1958 Mar;137(2):317–347. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401370206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher E. M., Hoppe P. C. Use of chimeras to transmit lethal genes in the mouse and to demonstrate allelism of the two X-linked male lethal genes jp and msd. J Exp Zool. 1973 Feb;183(2):181–184. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401830205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe P. C., Pitts S. Fertilization in vitro and development of mouse ova. Biol Reprod. 1973 May;8(4):420–426. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/8.4.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly T. E., Rary J. M. Mosaic tetraploidy in a two-year-old female. Clin Genet. 1974;6(3):221–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. R. A widely applicable technic for direct processing of bone marrow for chromosomes of vertebrates. Stain Technol. 1969 May;44(3):155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert C. L., Petters R. M. Homozygous mouse embryos produced by microsurgery. J Exp Zool. 1977 Aug;201(2):295–302. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402010213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markert C. L., Petters R. M. Manufactured hexaparental mice show that adults are derived from three embyronic cells. Science. 1978 Oct 6;202(4363):56–58. doi: 10.1126/science.694518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson G. L., Yanagimachi R., Yanagimachi H. Ultrastructural localization of lectin-binding sites on the zonae pellucidae and plasma membranes of mammalian eggs. J Cell Biol. 1975 Aug;66(2):263–274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.66.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemierko A. Induction of triploidy in the mouse by cytochalasin B. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1975 Oct;34(2):279–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petters R. M., Markert C. L. Production and reproductive performance of hexaparental and octaparental mice. J Hered. 1980 Mar-Apr;71(2):70–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow M. H. Embryonic development of tetraploid mice during the second half of gestation. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1975 Dec;34(3):707–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow M. H. Tetraploid mouse embryos produced by cytochalasin B during cleavage. Nature. 1973 Aug 24;244(5417):513–515. doi: 10.1038/244513a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens L. C., Varnum D. S., Eicher E. M. Viable chimaeras produced from normal and parthenogenetic mouse embryos. Nature. 1977 Oct 6;269(5628):515–517. doi: 10.1038/269515a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surani M. A., Barton S. C., Kaufman M. H. Development to term of chimaeras between diploid parthenogenetic and fertilised embryos. Nature. 1977 Dec 15;270(5638):601–603. doi: 10.1038/270601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkowki A. K. In vitro development of haploid mouse embryos produced by bisection of one-cell fertilized eggs. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1977 Apr;38:187–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkowski A. K., Witkowska A., Opas J. Development of cytochalasin in B-induced tetraploid and diploid/tetraploid mosaic mouse embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1977 Oct;41:47–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard H. F., Breg W. R. Human X chromosomes: synchrony of DNA replication in diploid and triploid fibroblasts with multiple active or inactive X chromosomes. Somatic Cell Genet. 1980 Mar;6(2):187–198. doi: 10.1007/BF01538795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]