Abstract

Calcium (Ca2+) signals drive the fundamental events surrounding fertilization and the activation of development in all species examined to date. Initial studies of Ca2+ signaling at fertilization in marine animals were tightly linked to new discoveries of bioluminescent proteins and their use as fluorescent Ca2+ sensors. Since that time, there has been rapid progress in our understanding of the key functions for Ca2+ in many cell types and the impact of cellular localization on Ca2+ signaling pathways. In this review, which focuses on mammalian egg activation, we consider how Ca2+ is regulated and stored at different stages of oocyte development and examine the functions of molecules that serve as both regulators of Ca2+ release and effectors of Ca2+ signals. We then summarize studies exploring how Ca2+ directs downstream effectors mediating both egg activation and later signaling events required for successful preimplantation embryo development. Throughout this review, we focus attention on how localization of Ca2+ signals influences downstream signaling events, and attempt to highlight gaps in our knowledge that are ripe areas for future research.

Keywords: fertilization, oocyte, calcium influx, SOCE, CaMKII

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) is a ubiquitous second messenger that regulates secretion, contraction, metabolic enzymes, gene expression, and many other cell functions. Ca2+ has critical roles in fertilization in all animal species studied to date, from marine invertebrates to mammals. In all of these organisms, a rise in intracellular Ca2+ is responsible for releasing unfertilized eggs from arrest in meiosis and triggering the embryonic developmental program; this process is known as “egg activation”.

Our current knowledge regarding Ca2+ signaling during fertilization and embryo development in mammals was made possible by key observations and methodological developments largely generated by early studies of marine animals. Experiments in sea urchins in the 1930’s led to the first suggestion that Ca2+ was important at fertilization (Heilbrunn and Young 1930; Mazia 1937). In 1962, Shimomura et al. purified the bioluminescent, blue light-emitting protein aequorin from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria and reported that it could be utilized as an indicator of Ca2+ concentrations in biological fluids (Shimomura et al. 1962; Shimomura et al. 1963). Microinjection of purified aequorin into medaka eggs resulted in the first documentation of a large increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels in response to a fertilizing sperm (Ridgway et al. 1977). Aequorin was eventually used to demonstrate that in mouse and hamster eggs, unlike the single large increase in Ca2+ observed in most marine animals, multiple oscillations in intracellular Ca2+ occur and persist for several hours after fertilization (Cuthbertson and Cobbold 1985; Cuthbertson et al. 1981; Miyazaki et al. 1986). This finding was later shown to be true of all types of mammalian eggs.

In the early 1980’s, a series of optical indicators for Ca2+ were developed based on the Ca2+ chelator, 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, better known as BAPTA (Tsien 1983). The addition of acetoxymethyl ester groups to these tetracarboxylate indicators allowed cellular uptake without microinjection; cleavage of the ester group by intracellular esterases resulted in trapping of the indicator in the cytoplasm. The indicators had strongly enhanced ultraviolet light-induced fluorescence in response to Ca2+ binding, and allowed detection of sub-micromolar changes in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. The later development of fluorescent Ca2+ indicators with excitation and emission spectra in the visible range expanded their use dramatically (Minta et al. 1989). Finally, ratiometric Ca2+ indicators such as fura-2 were developed whose peak excitation wavelength altered in response to Ca2+ binding, allowing calculations of increases in Ca2+ over baseline levels (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985). Ratiometric Ca2+ indicators are currently used widely to study Ca2+ signaling at fertilization in mammals.

In the 1970’s, a second bioluminescent protein, green fluorescent protein, was purified from several Aequora species, and the protein was eventually cloned (Chalfie 1995; Prasher et al. 1992; Prendergast and Mann 1978). Expression of green fluorescent protein in prokaryotic cells was reported in 1994, beginning the modern era of using exogenously expressed fluorescent proteins as markers of gene expression and as genetically encoded sensors of Ca2+ and other small molecules. Together, these studies set the stage for rapid progress in our understanding of the key functions for Ca2+ during mammalian egg activation and embryo development, and the impact of cellular localization on these signaling pathways.

In this review, which focuses on mammals, we first consider in detail how Ca2+ itself is regulated and stored at different stages of oocyte development and how Ca2+ is released during egg activation. We then summarize the available literature regarding how Ca2+ directs the numerous downstream events of egg activation required for successful preimplantation embryo development. We focus attention on how the localization of various Ca2+ pools influences downstream signaling events. Throughout this review, we will attempt to highlight gaps in our knowledge that are ripe areas for future research.

Regulation of calcium stores

Both the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria regulate intracellular signaling through the storage and release of Ca2+. The ER is the major Ca2+ storage organelle in eggs and it plays a critical role in the initiation of Ca2+ release at fertilization. The ER contains Ca2+ pumps, intraluminal Ca2+ storage proteins, and specific Ca2+-releasing channels, which together regulate Ca2+ signaling while maintaining cellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Mitochondria mainly serve as energy-supplying organelles that in oocytes provide ATP for fertilization and preimplantation embryo development (Torner et al. 2004). However, mitochondria also regulate intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis by serving as a “buffer” for high cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. Ca2+ enters mitochondria when the Ca2+ concentration in the cytoplasm is over a certain threshold, and once the cytoplasmic Ca2+ has returned to its resting level, Ca2+ is pumped back into cytoplasm by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (Bootman et al. 2001). In addition to the ER and mitochondria, there is evidence that Ca2+ can be stored and released by actin filaments in response to both extracellular and intracellular signals (Lange and Gartzke 2006).

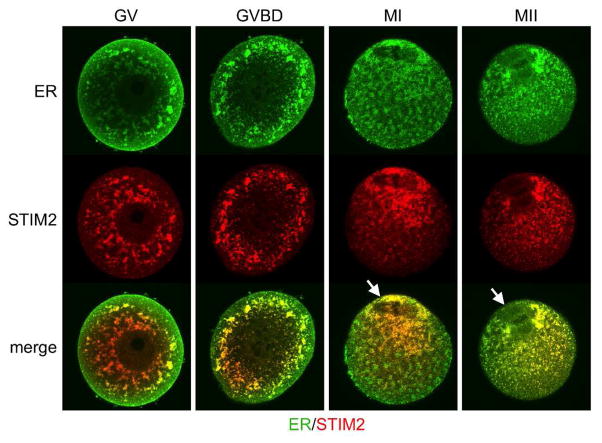

Intracellular Ca2+ stores are regulated in part by “store operated Ca2+ entry” (SOCE), a mechanism to replenish intracellular Ca2+ from the extracellular environment (Putney 1986). Several molecules involved in mediating SOCE are now identified. Depletion of ER Ca2+ stores is recognized by one of two STIM proteins, STIM1 and STIM2, which are single transmembrane ER proteins that bind Ca2+ through an EF-hand motif located in the ER lumen (Cai 2007; Hewavitharana et al. 2007; Roos et al. 2005; Williams et al. 2001). STIM2 is activated by small decreases in ER luminal Ca2+, suggesting it functions to stabilize basal cytosolic and ER Ca2+ levels under non-stimulated conditions (Brandman et al. 2007). In contrast, STIM1 is only activated by larger decreases in ER luminal Ca2+ that occur during triggered Ca2+ signaling events, at least in part because of its higher Ca2+affinity. In somatic cells, significant lowering of ER Ca2+ levels causes oligomerization and redistribution of STIM1 into punctate ER structures near the plasma membrane (Liou et al. 2005; Smyth et al. 2008). These activated STIM1 oligomers signal to ORAI proteins, which are highly selective plasma membrane Ca2+ channel subunits, stimulating transport of extracellular Ca2+ into the cytosol (Feske et al. 2006; Vig et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2005). Sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) pumps can then transport Ca2+ back into the ER, replenishing cellular stores. Mammalian oocytes express both STIM1 and ORAI1 (Gomez-Fernandez et al. 2009; Koh et al. 2009). Mouse oocytes also express STIM2, which co-localizes with the ER marker calreticulin (Fig. 1). STIM2 distribution changes during oocyte maturation, when it becomes strongly associated with the region surrounding the meiotic spindles and is lower in the vegetal poles. These findings indicate that similar to somatic cells, both STIM1 and STIM2 likely function to regulate ER Ca2+ stores in mouse and other mammalian oocytes.

Figure 1. Localization of STIM2 in maturing mouse oocytes.

Mouse oocytes at the germinal vesicle (GV), germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD), metaphase I (MI), and metaphase II (MII) stages were fixed and stained for both STIM2 (red) and calreticulin, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER; green) marker. Antibodies used were anti-STIM2 (Cat# 4125; ProSci Inc., Poway, CA) and anti-calreticulin (cat# sc-7431; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Spindle region indicated on merged images with arrows.

It is not clear whether SOCE plays an important role in replenishing Ca2+ stores in mature mammalian oocytes during fertilization. In somatic cells, SOCE is suppressed during mitotic stages of the cell cycle by phosphorylation of STIM1 (Smyth et al. 2009). In maturing Xenopus oocytes, SOCE becomes uncoupled from Ca2+ depletion around the time of germinal vesicle (GV) breakdown (Machaca and Haun 2000; Machaca and Haun 2002). In addition, ORAI1 becomes internalized and STIM1 oligomerization does not occur, indicating that SOCE is essentially inactive during meiosis in Xenopus (Yu et al. 2009a). It is well documented that SOCE can be induced experimentally in mature mammalian oocytes (Machaty et al. 2002; Martin-Romero et al. 2008; McGuinness et al. 1996; Miao et al. 2012), but there are conflicting reports regarding whether SOCE is required for egg activation. During mouse fertilization, inhibiting SOCE using either gadolinium or the specific SOCE inhibitor Synta66 (Ng et al. 2008) does not prevent replenishment of intracellular Ca2+ stores after fertilization, indicating that Ca2+ influx occurs through alternative channels (Miao et al. 2012). In pig oocytes in which siRNA was used to knock down STIM1 protein levels during oocyte maturation, fertilization mainly induced only a single Ca2+ transient and no subsequent oscillations occurred (Lee et al. 2012). Of note, the amplitude of the first Ca2+ transient in the control eggs shown in this study was much higher than that in the STIM1-depleted eggs, indicating that the Ca2+ stores had been depleted before fertilization occurred. Although it is certainly possible that there are species differences in a requirement for SOCE at fertilization, our interpretation of these apparently conflicting results is that porcine oocytes require STIM1 to maintain ER Ca2+ stores during maturation; consequently, STIM1-depleted oocytes have diminished Ca2+ stores leading to the single low amplitude sperm-induced Ca2+ transient and failure of the sperm-induced egg activation cascade. In support of this interpretation, the same authors demonstrated that the amount of Ca2+ mobilized in response to ionomycin treatment is far less in STIM1-depleted pig oocytes than in controls (Lee et al. 2012). Further experiments in these and other mammalian systems may shed light on whether these results represent species differences or whether alternative mechanisms are required to promote Ca2+ influx during fertilization of mammalian oocytes.

Alterations in calcium release mechanisms during oocyte maturation

In most mammals, GV oocytes arrested in the diplotene stage of meiosis I are stimulated to resume meiosis in response to the LH surge. The oocyte subsequently undergoes GV breakdown, progresses through the remainder of meiosis I, extrudes the first polar body, and finally becomes arrested again at metaphase of meiosis II (MII). This process is referred to as “oocyte maturation”, and it includes a complex sequence of nuclear and cytoplasmic events that prepare the egg for fertilization and initiation of embryo development.

During maturation to MII, the ER undergoes a dramatic microtubule- and microfilament-dependent structural reorganization (FitzHarris et al. 2007; Mann et al. 2010; Mehlmann et al. 1995). In GV stage oocytes, the ER is continuous with the nuclear envelope and has a fine reticular structure throughout the cytoplasm, with few small accumulations in the cortex (Mehlmann et al. 1995). At GVBD, the ER begins to restructure into a dense reticular network intimately connected with the MI spindle as it migrates toward the oocyte cortex (FitzHarris et al. 2007). At MII, the ER is no longer tightly associated with the spindle. Instead, it is organized in a reticular network of large diameter (~2–3 Om) sub-plasma membrane accumulations mainly in regions away from the MII spindle (Mehlmann et al. 1995).

Concomitant with the changes in organization of Ca2+ storage organelles, the oocyte’s ability to release Ca2+ in response to various triggers changes with maturation. The Ca2+ transient induced by the Ca2+ ionophore, ionomycin, in MII eggs is approximately 3-fold larger than that induced in GV oocytes, and the greatest change occurs between MI and MII (Jones et al. 1995; Mehlmann and Kline 1994). Similarly, MII eggs release more Ca2+ than GV oocytes in response to either microinjected inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) or fertilization by sperm (Fujiwara et al. 1993; Mehlmann and Kline 1994). One explanation for these findings would be that there are larger releasable Ca2+ stores in MII eggs than in GV oocytes. However, mouse GV oocytes treated with thimerosal, a chemical that sensitizes the IP3-receptor so that more Ca2+ is released in response to the same amount of IP3, release just as much Ca2+ as MII eggs, and more than that induced by treating GV oocytes with ionomycin (Mehlmann and Kline 1994). In oocytes of other species, such as the hamster, IP3 sensitivity changes less dramatically over the course of maturation, with GV oocytes containing at least 80% of the IP3-sensitive Ca2+ stores present in MII eggs. (Fujiwara et al. 1993). These findings indicate that at least in some species the Ca2+ stores in GV oocytes and MII eggs are similar, and that GV oocytes are much less sensitive to Ca2+ release mechanisms. The increase in sensitivity of MII eggs to IP3-mediated Ca2+ release is likely caused in part by recruitment of IP3-receptor type 1 (IP3R1) mRNA for translation during maturation, resulting in increased protein levels in MII eggs (He et al. 1997; Mehlmann et al. 1996; Xu et al. 1994). In addition, changes in phosphorylation of IP3R1 likely increase the efficiency of Ca2+ release in MII eggs (Wakai et al. 2012).

Egg activation overview

The transition of an unfertilized egg, which is arrested in metaphase of meiosis II, to a developing embryo, requires completion of a sequence of events known as egg activation. These events include cortical granule (CG) exocytosis, modifications of the zona pellucida and plasma membrane that prevent polyspermy, completion of meiosis, recruitment of maternal mRNAs into polysomes for translation, and formation of male and female pronuclei (Schultz and Kopf 1995). In all animal species studied to date, alterations in intracellular Ca2+ initiate egg activation.

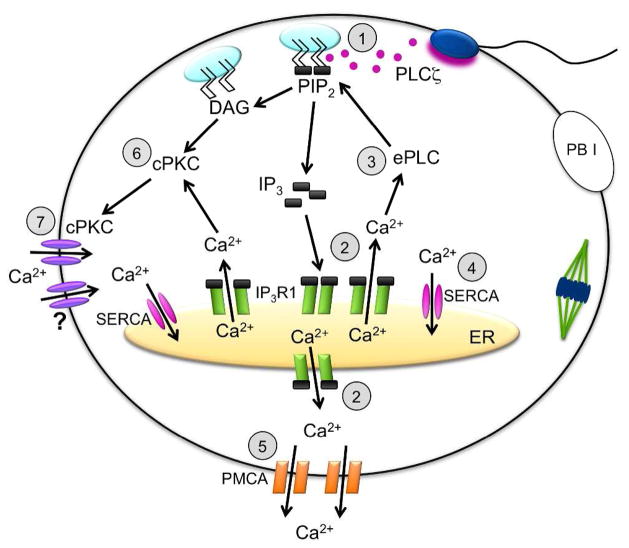

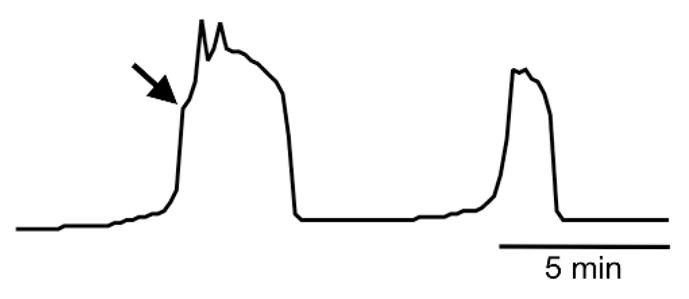

In mammals, Ca2+ release occurs after sperm-egg plasma membrane fusion in response to release of sperm head-associated phospholipase C zeta (PLCζ) into the egg’s cytoplasm (Kashir et al. 2012; Knott et al. 2005; Saunders et al. 2002). PLCζ catalyzes breakdown of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG); endogenous egg PLCβ isoforms likely also contribute to IP3 generation at fertilization (Igarashi et al. 2007). IP3 subsequently binds to IP3R1 in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membranes, triggering Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive ER stores (Miyazaki et al. 1992; Xu et al. 1994). This initial Ca2+ release leads to the generation of low frequency oscillations in intracellular Ca2+ that result from the sequential release of Ca2+ from ER stores followed by reuptake of Ca2+ into the ER via SERCA pumps and extrusion of Ca2+ from the egg via plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase pumps. These Ca2+ oscillations continue for several hours, and are dependent on replenishment of Ca2+ stores by influx of extracellular Ca2+ (Igusa and Miyazaki 1983; Kline and Kline 1992). The characteristic shapes of the first two Ca2+ transients are shown in Figure 2, and a schematic diagram showing how Ca2+ fluxes are initiated at fertilization is shown in Figure 3. In the following sections, we will review in detail the contributions of different signaling molecules to generating the Ca2+ oscillations.

Figure 2. Characteristic appearance of first and second sperm-induced Ca2+ transients.

Arrow indicates “shoulder” in first Ca2+ transient.

Figure 3. Ca2+ release and reuptake pathways during initial egg activation.

Schematic diagram of Ca2+ release from ER stores in response to PLCζ-mediated generation of IP3 and the channels responsible for Ca2+ extrusion and reuptake. 1) PLCζ hydrolyzes PIP2 in cortical pool to generate IP3 and DAG. 2) IP3 mediates Ca2+ release from ER stores via IP3R1. 3) Increased cytosolic Ca2+ and possibly other signaling molecules activate endogenous egg PLC(s), causing generation of additional IP3. 4) Ca2+ re-enters ER stores via SERCA pumps. 5) Cytoplasmic Ca2+ is extruded from egg by PMCA pumps. 6) DAG and Ca2+ promote plasma membrane translocation of cPKC. 7) Phosphorylation of cPKC-sensitive Ca2+ channels promotes Ca2+ influx. PB I, first polar body; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; PLCζ, phospholipase C zeta; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; DAG, diacylglycerol; ePLC, egg phospholipase C; cPKC, conventional protein kinase C; IP3R1, type 1 IP3 receptor; Ca2+, calcium; SERCA, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase pump; PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase pump; ?, cPKC-sensitive plasma membrane Ca2+ channel(s), identity unknown.

Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C

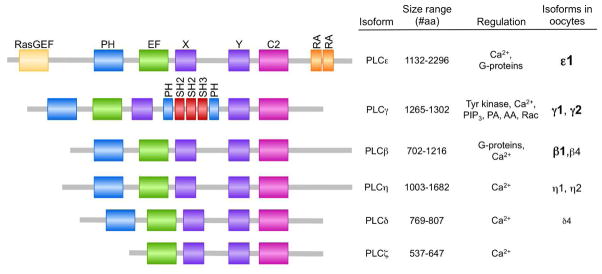

The 13 mammalian phosphoinositide PLCs are grouped into six sub-families, β, γ, δ, ε, η, and ζ, on the basis of sequence homology and the location of structural domains (Fig. 4)(Rhee and Bae 1997; Suh et al. 2008). Although these PLC isoforms all catalyze the hydrolysis of PIP2 to IP3 and DAG, the signals that activate them differ, and they are expressed in a tissue and cell-specific fashion that controls their contributions to modulating cellular responses. Several different PLC isoforms are found in the fertilized egg and likely contribute to IP3-receptor-mediated Ca2+ fluxes. As mentioned above, the sperm delivers PLCζ to the egg at the time of sperm-egg fusion. In addition, mouse oocytes contain mRNAs encoding at least 8 of the 13 PLC isoforms, including members of all sub-families except for PLCζ (Fig. 4). Based on information deposited in GEO Profiles (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geoprofiles), human and cow oocytes appear to contain the same PLC isoforms as mouse oocytes, but there is much less information available regarding the relative quantities of the various isoforms.

Figure 4. Phospholipase C isoforms.

Schematic diagram of functional domains of the six mammalian PLC sub-families. The size ranges of the proteins and their splice forms within each PLC sub-family and known regulatory mechanisms are indicated. Based on 3 distinct microarray datasets deposited in GEO Profiles, mammalian oocytes contain the listed PLC isoforms. Isoforms listed in larger, bold font have the highest signal intensities; isoforms in smaller, plain font have lower signal intensities, suggesting relative abundance of the mRNAs. PLC isoforms with an average signal intensity in fully grown oocytes of < 50 across the three datasets are not listed. RasGEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras-like small GTPases domain; PH, pleckstrin homology domain; EF, EF-hand-like domain; X and Y, catalytic domains; C2, C2-domain Ca2+-binding pocket; RA, Ras-association domain; SH2, Src-homology 2 domain; SH3, Src-homology 3 domain; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate; PA, phosphatidic acid; AA, arachidonic acid; Rac, Rac GTPases.

PLCζ contains the conserved Ca2+-binding EF hand domain, catalytic domains, and C2 domains found in all PLCs (Fig. 4). However, it lacks the phosphatidylinositol-binding pleckstrin homology domain, which can mediate plasma membrane localization of other PLCs via interactions with phospholipids [reviewed in (Ito et al. 2011)]. Instead, PLCζ localizes diffusely throughout the cytoplasm when exogenously expressed in mouse eggs, suggesting that the sperm PLCζ that enters the egg at fertilization is also freely diffusible (Yu et al. 2012). Indeed, there is evidence that PLCζ targets a cortical but non-plasma membrane pool of PIP2 for hydrolysis at fertilization (Yu et al. 2012). A second unusual feature of PLCζ is its extremely high Ca2+ sensitivity, with 70% maximal activity at Ca2+ concentrations of 100 nM (Kouchi et al. 2004). This high Ca2+ sensitivity suggests that simple exposure of sperm-derived PLCζ to basal cytoplasmic egg Ca2+ levels could stimulate PLCζ to produce an amount of IP3 sufficient to trigger the initial release of Ca2+ from ER stores.

PLCβ isoforms are typically activated by G-protein-dependent pathways linked to transmembrane receptors (Rhee and Bae 1997). A unique feature of PLCβ isoforms is their elongated C-terminal region that mediates interactions with Gq-family α subunits, whereas the PH domain appears to mediate Gβγ subunit interactions (Suh et al. 2008). Gαq does not appear to activate egg PLCβ isoforms at fertilization because a Gαq-specific function-blocking antibody does not prevent sperm-induced egg activation (Williams et al. 1998). However, blocking activity of Gβγ subunits by microinjecting eggs with phosducin partially inhibits pronucleus formation after fertilization (Moore et al. 1994), suggesting that Gβγ-mediated PLCβ activation could facilitate IP3 generation. In addition, PLCβ isoform activity is enhanced by rising Ca2+ levels (Taylor et al. 1991) such as would be expected in the fertilized egg downstream of PLCζ activity. This property of PLCβ suggests that it could promote additional IP3 production and subsequent IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release, contributing to the large increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ observed in the fertilized egg. Indeed, there is evidence in mouse oocytes that reduction of PLCβ1 protein results in alterations of Ca2+ oscillatory activity observed at fertilization, suggesting that PLCβ1 normally functions in collaboration with PLCζ to generate the IP3 required for the observed Ca2+ oscillatory pattern (Igarashi et al. 2007).

The PLCγ isoforms participate in mitogenic responses via interactions with receptor- and non-receptor (cytosolic) tyrosine kinases, and can also be activated by lipid-derived second messengers such as those generated by phospholipase D or phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (Rhee and Bae 1997). The PLCγ SH2 domains mediate association with receptor tyrosine kinases, which phosphorylate and activate PLCγ. Plasma membrane targeting of PLCγ may also be mediated by interactions between the PH domain and PIP3 generated by phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity. Both PLCγ1 and PLCγ2 are present in mouse eggs, and microinjecting recombinant PLCγ1 into mouse eggs can induce low frequency Ca2+ oscillations similar to those induced by sperm (Mehlmann et al. 2001). However, inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinases, Src-family kinases, or SH2 domain-mediated PLCγ activation does not affect sperm-induced Ca2+ release, indicating that PLCγ activation by these mechanisms is not required at fertilization (Kurokawa et al. 2004; Mehlmann et al. 1998; Mehlmann et al. 2001; Mehlmann and Jaffe 2005). The possibility remains; however, that egg PLCγ could contribute to IP3 generation downstream of either cytosolic tyrosine kinase activity or lipid second messengers generated at fertilization. Indeed, there is evidence in the mouse that fertilization causes activation of Src-family tyrosine kinases in localized regions of the egg (McGinnis et al. 2007; McGinnis et al. 2011). In addition, a unique cytosolic PLA2 isoform, cPLA2γ, is highly abundant in the mouse egg (Vitale et al. 2005), and could generate lipid-signaling molecules such as arachidonic acid that activate PLCγ.

Like PLCζ, both PLCη isoforms are very sensitive to activation by Ca2+ (Stewart et al. 2007), so endogenous egg PLCη, if present, would likely contribute to IP3 generation downstream of the initial PLCζ-mediated Ca2+ increase. Although PLCδ isoforms are about 10-fold less sensitive to Ca2+ than PLCη isoforms (Stewart et al. 2007), a contribution of these PLCs to fertilization-induced Ca2+ release is also possible. PLCε is activated by small GTPases, Gα12/13, and Gβγ subunits. PLCε could in theory promote IP3 generation at fertilization, but expression in mouse eggs of a constitutively active form of RAS, which should activate PLCε, does not induce Ca2+ release or other egg activation events (Moore et al. 1994), making this an unlikely scenario.

It is now well established that PLCζ activity initiates Ca2+ release at fertilization, even though only a very small quantity of the protein is carried into the egg by the single fertilizing sperm (Saunders et al. 2002). However, the variety of endogenous PLC isoforms expressed in mammalian eggs, combined with the initial generation of several potential activators of these PLC isoforms, indicates that endogenous egg PLCs likely contribute significant amounts of enzymatic activity toward PIP2 hydrolysis at fertilization (Fig. 3). The identity of endogenous egg PLCs and their relative contributions to controlling Ca2+ oscillations at fertilization are ripe areas for future research.

Protein kinase C (PKC)-mediated regulation of calcium

Numerous PKC isoforms are expressed in mammalian eggs, including members of the conventional, novel, and atypical PKC subfamilies (Kalive et al. 2010). Conventional PKCs (cPKCs), which include PKCα, β, and γ isoforms, undergo Ca2+-dependent activation by DAG and anionic phospholipids, resulting in plasma membrane translocation and phosphorylation of substrate proteins on serine or threonine residues. In somatic cells, cPKC movement between the plasma membrane and cytoplasm occurs in synchrony with alterations in intracellular Ca2+ (Oancea and Meyer 1998). In mouse eggs, cPKCs translocate to the plasma membrane in response to elevations in intracellular Ca2+ via interactions of Ca2+ with the regulatory C2 domain (Halet et al. 2004). DAG generated during PIP2 hydrolysis by PLC also binds to the regulatory C1 domains, and likely increases the time of cPKC membrane association. As in somatic cells, when egg Ca2+ levels return to baseline, the cPKCs dissociate and return to the cytosol until the subsequent Ca2+ rise.

Modulation of PKC activity in the egg at fertilization by either over-expression of PKC isoforms or use of cell-permeant PKC activators significantly increases the duration and frequency of Ca2+ oscillations, and also promotes Ca2+ influx (Halet et al. 2004; Yu et al. 2008). Furthermore, inhibition of PKC activity reduces the persistence of Ca2+ oscillations; this effect is partially mitigated by increasing the extracellular Ca2+ concentration. These findings suggest that PKC activity regulates Ca2+ influx at fertilization by phosphorylating substrates at or near the plasma membrane (Fig. 3).

The nature of these cPKC substrates is not known. One possibility is that cPKC phosphorylates one or more cellular components involved in SOCE, e.g., STIM1 or ORAI1, promoting additional Ca2+ uptake via this route. This seems unlikely because in somatic cells, both STIM1 phosphorylation on serine residues and PKC-mediated phosphorylation of ORAI1 are associated with suppression of SOCE (Kawasaki et al. 2010; Smyth et al. 2009). In Xenopus oocytes, SOCE is inactive during meiosis as a result of internalization of ORAI1 into an intracellular vesicular compartment (Yu et al. 2009a). Furthermore, in mouse eggs, inhibiting SOCE has no effect on sperm-induced Ca2+ oscillations, suggesting that the majority of Ca2+ influx at fertilization occurs through non-SOCE-associated Ca2+ channels (Miao et al. 2012). There is precedent for this idea because somatic cell ion channels including transient receptor potential-family Ca2+-permeable channels can be activated by PKC or DAG (Dai et al. 2009; Large et al. 2009), but the molecular basis for Ca2+ influx across the egg plasma membrane at fertilization remains to be determined.

Impact of calcium oscillation parameters on egg activation

Based on studies of mouse eggs fertilized in vitro, the first Ca2+ transient occurs within a few minutes of sperm–egg fusion after a prolonged (~1 min) small rise in cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Deguchi et al. 2000). The characteristic shape of the first Ca2+ transient is an extremely rapid rise for 2–3 seconds, followed by an inflection point representing a very short decrease in the rate of Ca2+ rise, referred to as a “shoulder”, and then a resumption of a the very rapid rate of Ca2+ rise to a peak of 1–3 OM (Fig. 2). The Ca2+ level drops but remains significantly elevated above baseline for up to several minutes; there are often additional small Ca2+ spikes superimposed on the early period of the first transient. The first transient is completed with a rapid drop in Ca2+ to baseline. This multi-component first Ca2+ transient pattern is consistent with the idea that several distinct mechanisms contribute to Ca2+ release, including IP3 generation by sperm PLCζ and multiple egg PLC isoforms. In addition, Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release likely contributes. Succeeding Ca2+ transients are typically of lower amplitude, shorter duration, either lack or have a less distinct shoulder and superimposed spike pattern, and slow in frequency over time. The Ca2+ oscillation frequency is highly variable in different species and even between different eggs from the same individual, ranging from as high as every ~3 min in the hamster to ~50 min in the cow (Jones 1998). The oscillations generally persist for several hours, ending around the time of pronucleus formation.

Spatiotemporal analysis of the first Ca2+ transient in the mouse indicates that it is initiated near the site of sperm-egg fusion and subsequently a wave of increased Ca2+ is propagated toward the opposite side of the egg (Deguchi et al. 2000). Subsequent Ca2+ transients are initiated from regions in the egg cortex not restricted to the sperm entry site, likely from cortical regions enriched in ER accumulations (Kline et al. 1999). Cytoplasmic movements reminiscent of those that occur after fertilization in numerous lower species appear to coincide with these Ca2+ waves (Deguchi et al. 2000). These cytoplasmic movements depend on actomyosin-based cytoskeletal alterations, and the extent of these movements has been proposed to correlate with developmental potential (Ajduk et al. 2011). This correlation would not be surprising because there is a clear correlation between the total Ca2+ signal experienced by the egg after fertilization and the success of both pre- and post-implantation embryo development (Ozil et al. 2006; Ozil et al. 2005). The importance of the Ca2+ oscillatory pattern for subsequent development has raised concerns regarding the use of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) for clinical assisted reproduction. ICSI results in Ca2+ oscillations similar to those induced by standard in vitro fertilization, but spatiotemporal aspects of the signaling pattern differ somewhat (Sato et al. 1999).

Not surprisingly, qualities of the egg also strongly influence the Ca2+ oscillatory pattern. Eggs fertilized later than normal after ovulation, referred to as “post-ovulatory aged eggs” or “aged eggs”, have altered Ca2+ oscillatory patterns including higher frequency but lower amplitude Ca2+ transients that have slower rates of rise and fall (Hao et al. 2009; Igarashi et al. 1997; Jones and Whittingham 1996). These alterations appear to be due in part to decreases in egg ER Ca2+ stores with time after ovulation (Jones and Whittingham 1996; Takahashi et al. 2009), which is a finding consistent with a non-existent or poorly functioning SOCE system during meiotic stages of the cell cycle. Aged eggs have lower developmental potential than recently ovulated eggs, likely as a result of these perturbations in Ca2+ signaling.

Early responses to calcium signals at fertilization

Mitochondrial energy production

One of the earliest effects of sperm-induced Ca2+ release is stimulation of mitochondrial energy production (Campbell and Swann 2006; Dumollard et al. 2004). In somatic cells, mitochondrial function is regulated by Ca2+ uptake into the mitochondrial matrix through the high capacity Ca2+ uniporter. The increase in Ca2+ levels causes activation of several Ca2+-sensitive mitochondrial enzymes and subsequently increased NADH/NAD ratios and ATP production (Ashby and Tepikin 2001). In addition, Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial substrate carriers can be activated directly by increases in cytosolic Ca2+(Satrustegui et al. 2007). Based on work in sea urchin and ascidian eggs, Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria most likely also occurs at fertilization in mammalian eggs (Dumollard et al. 2006). In mouse eggs, coincident with each cytosolic Ca2+ transient there is a measurable increase in NADH and decrease in FAD2+, both of which occur during activation of the citric acid cycle (Dumollard et al. 2004). Furthermore, the amount of ATP in the egg begins to increase at the time of the first Ca2+ transient, and continues to increase during the entire period encompassed by continuing Ca2+ oscillations before returning to baseline with their cessation (Campbell and Swann 2006).

In addition to providing energy for egg activation and embryo development, mitochondria participate in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Because of their active Ca2+ uptake and efflux mechanisms, mitochondria serve to buffer cytosolic Ca2+ levels while at the same time prolonging the time of cytosolic Ca2+ elevation. Mitochondria located in close proximity to the ER can also facilitate refilling of ER stores after IP3-stimulated Ca2+ release (Malli et al. 2005). In mouse eggs, chemical inhibitors of mitochondrial function disrupt the sperm-induced Ca2+ oscillatory pattern, and cause a sustained increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Liu et al. 2001). These findings support a model in which mitochondrial Ca2+ sequestration normally contributes to returning Ca2+ levels to baseline between the Ca2+ transients. Contributions of mitochondria to regulating spatiotemporal aspects of Ca2+ oscillatory behavior and the reciprocal, i.e., contributions of Ca2+ fluxes to regulating mitochondrial function, could explain why eggs that do not undergo appropriate maturation-associated mitochondrial redistribution or have abnormally functioning mitochondria have low developmental competence (Au et al. 2005; Fernandes et al. 2012; Hao et al. 2009).

Cortical granule exocytosis/zona pellucida block to polyspermy

Cortical granules (CGs) are membrane-bound vesicles located in the cortex of the mature egg, but restricted from the actin cap region overlying the metaphase II spindle (Deng et al. 2003). CG exocytosis can be observed within minutes of the first Ca2+ transient after fertilization, and the Ca2+ increase is both necessary and sufficient for this event (Abbott and Ducibella 2001). Additional Ca2+ oscillations continue to drive waves of CG exocytosis, so that the number of CGs remaining in the egg continues to decrease with time after fertilization, and most of the CGs are gone in pronuclear stage embryos (Ducibella et al. 2002). The Ca2+-dependent downstream mediators that transduce the Ca2+ signal to cause CG exocytosis in mammalian eggs have not yet been identified. By analogy to somatic cells, these could include calmodulin, calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), PKC isoforms, and actin depolymerizing enzymes, among others.

Exposure of the zona pellucida to CG contents extruded into the perivitelline space results in biochemical modifications that comprise the zona pellucida block to polyspermy. In mammalian eggs only a single protein, the metalloendoprotease ovastacin, has been demonstrated to be a CG component (Burkart et al. 2012). Ovastacin cleaves the zona pellucida glycoprotein ZP2, which prevents additional sperm binding (Burkart et al. 2012). Thus, Ca2+ signaling upstream of CG exocytosis is a critical regulator of the zona pellucida block to polyspermy.

Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)/cell cycle resumption

CaMKII is a ubiquitous serine-threonine protein kinase that is activated by Ca2+ and calmodulin to phosphorylate diverse substrates. CaMKII oligomers undergo autophosphorylation after Ca2+/calmodulin binding to the autoinhibitory region relieves inhibition of the catalytic sites (Tombes et al. 2003). The phosphorylated form of CaMKII has “autonomous” activity independent of Ca2+. This complex autoregulatory behavior of CaMKII allows it to decode the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ spikes (De Koninck and Schulman 1998). In mouse eggs, CaMKII activity rises with the first Ca2+ transient and then parallels the subsequent Ca2+ oscillations, indicating that this enzyme is a proximal decoder of the Ca2+ signals at fertilization (Markoulaki et al. 2004).

In mammals, four genes encode multiple isoforms of CaMKII (α, β, γ, and δ) that have distinct expression and localization patterns allowing for differential regulation of their downstream effectors (Tombes et al. 2003). CaMKIIγ is the predominant isoform in mouse eggs, although CaMKIIδ is also expressed to some degree (Backs et al. 2010). Several lines of evidence indicate that CaMKII is an important proximal effector of Ca2+ signaling during egg activation. First, CaMKII inhibitors prevent cell cycle progression in both parthenogenetically activated and fertilized mouse eggs (Johnson et al. 1998). Furthermore, expressing a constitutively active form of CaMKII (lacking the autoinhibitory domain) induces complete egg activation and subsequent formation of developmentally competent blastocysts in the absence of any measurable alterations in egg cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Knott et al. 2006). A definitive role for the CaMKII isoform in promoting cell cycle resumption at fertilization was demonstrated using CaMKIIγ knockout mice. Eggs from these mice exhibit a normal pattern of sperm-induced Ca2+ oscillations and undergo CG exocytosis; however, they completely fail to resume meiosis and as a result the females are completely infertile (Backs et al. 2010). CaMKII substrates whose phosphorylation is required for meiosis II resumption include Wee1b, an inhibitor of the cell cycle regulator cyclin dependent kinase 1, and endogenous meiotic inhibitor 2, which regulates function of the anaphase promoting complex (Oh et al. 2011; Perry and Verlhac 2008). These studies clearly indicate that CaMKIIγ is a requisite mediator of cell cycle resumption at fertilization.

Later calcium-dependent responses during egg activation

Polar body emission

Emission of the second polar body (PB2) is driven largely by the early Ca2+/CaMKII-driven cell cycle resumption events described above. However, there appears to be a continuing role for Ca2+ in mediating successful cytokinesis. Activation of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzyme myosin light chain kinase (MYLK2) and its downstream target, myosin II, are required to regulate spindle position and completion of PB2 emission (Matson et al. 2006). The Ca2+-dependent PKC isoform, PKCα, and the phosphorylated form of myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate (MARCKS) both associate with the contractile ring of the forming PB2 (Kalive et al. 2010; Michaut et al. 2005). Because phosphorylation of MARCKS modulates actin crosslinking activity, these findings suggest a functional role for PKCα in modulating cytoskeletal activity required for PB2 emission.

Subcellular localization of the Ca2+ signal involved in PB2 emission appears to be critical for its success. Blocking Ca2+ influx in fertilized mouse eggs prevents PB2 emission, despite the occurrence of multiple intracellular Ca2+ oscillations and cell cycle resumption; the end result of this treatment is formation of embryos containing three pronuclei (Miao et al. 2012). There is precedent in the plant literature for the idea that Ca2+ influx is required for fertilization. In maize, Ca2+ influx is initiated locally at the site of sperm-egg cell fusion, is propagated to the opposite pole of the egg cell in association with actomyosin-based cortical contraction, and is followed by an overall increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Antoine et al. 2000; Antoine et al. 2001). The Ca2+ influx is required for sperm-egg cell fusion (Antoine et al. 2001).

In the mouse, even when Ca2+ influx is prevented, PB2 emission occurs when eggs are parthenogenetically activated with a constitutively active form of CaMKII. This finding suggests that Ca2+ influx-mediated signaling in the sub-plasma membrane region may act via CaMKII to mediate PB2 emission. The set of molecular players involved in such a signaling pathway likely include PKCα, MARCKS, MYLK2, myosin II and other Ca2+-sensitive cytoskeletal elements, but how these molecules might be regulated by Ca2+influx and CaMKII remains an open question.

Membrane block to polyspermy

In additional to the relatively rapid establishment of the zona pellucida block to polyspermy, properties of the egg plasma membrane change slowly after fertilization in a way that impairs binding of supernumerary sperm. These changes comprise the “membrane block to polyspermy”, which is assessed experimentally by measuring the ability of fertilized zona pellucida-free eggs to bind and fuse with additional sperm. Like other egg activation events detailed above, the membrane block is a graded response to Ca2+ signals, with more effective/more quickly established membrane blocks occurring in eggs that have higher numbers of Ca2+ oscillations (Gardner et al. 2007). However, Ca2+ signals alone are not sufficient, because eggs that undergo ICSI or that artificially express PLCζ have normal patterns of Ca2+ oscillations but do not form a membrane block (Maleszewski et al. 1996; Wortzman-Show et al. 2007). These findings suggest that sperm-egg fusion provides an essential signal to the plasma membrane and/or cortical cytoskeleton that, along with Ca2+, is required for establishment of the membrane block.

Maternal mRNA recruitment

During oocyte maturation, maternal mRNAs are recruited to polysomes for translation. This process continues after fertilization so that translation of new proteins required for embryo development can be initiated before transcription begins from the newly formed embryonic genome. Like CG exocytosis and the membrane block to polyspermy, recruitment of maternal mRNAs appears to be a graded response to the number of Ca2+ oscillations experienced by the egg (Ducibella et al. 2002). However, artificial methods of inducing cell cycle resumption, in the absence of Ca2+ elevation, can result in maternal mRNA recruitment (Knott et al. 2006). These findings indicate that the effects of Ca2+ are not direct, but instead occur indirectly by a process downstream of cell cycle resumption.

Calcium signaling during preimplantation embryo development

Mitotic cleavage divisions

Ca2+ transients are observed during mitotic cleavage events in embryos of a wide variety of invertebrate and vertebrate species (Whitaker 2006). These Ca2+ fluctuations may occur in restricted microdomains, so can be difficult to measure, but appear to be essential for mitotic divisions in fruit fly, sea urchin, starfish, and frog embryos. Although Ca2+ transients have been observed in association with pronuclear envelope breakdown in the mouse, these transients are not observed in all embryos (Day et al. 2000), and are not observed in parthenotes that nevertheless undergo mitotic cleavages (Kono et al. 1996). However, artificially induced Ca2+ increases provided to pronuclear stage embryos close to the time of nuclear envelope breakdown can accelerate this process, suggesting that although Ca2+ transients are not essential in the mouse they can participate in signaling during mitosis (FitzHarris et al. 2005).

Compaction

Eight-cell stage embryos undergo a dramatic morphogenetic process known as ‘compaction’, in which embryos change into a tightly packed cluster of cells from a loosely connected grouping of blastomeres that remain associated with each other largely by virtue of their common location within the zona pellucida. Compaction occurs as a result of increases in cell membrane apposition and increased intercellular adhesive forces, and is dependent on the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Ducibella and Anderson 1975). Indeed, a brief incubation in Ca2+-free medium allows for blastomere biopsy and experimental embryo dissociation procedures because this treatment significantly weakens intercellular adhesions. Compaction depends on alterations in both actin- and microtubule-based cytoskeletal structures, and involves cadherin 1, calmodulin and PKC (Kalive et al. 2010; Pey et al. 1998). Cadherin 1-mediated intercellular adhesive interactions depend on Ca2+ binding to its extracellular domains (Gumbiner 2005), explaining the reduction in blastomere adhesiveness in the absence of extracellular Ca2+. Alterations in intracellular Ca2+ modulate cytoskeletal architecture and the function of both calmodulin and PKC, indicating that intracellular Ca2+ fluxes are also likely to regulate compaction.

Implantation

Several lines of evidence support the involvement of Ca2+ fluxes in regulating implantation. Prior to implantation, or prior to hatching in vitro, blastocyst stage embryos develop “trophectoderm projections”, which are cytoplasmic projections that intermittently protrude through the zona pellucida to interact with the external environment (Gonzales et al. 1996). This process is reminiscent of the behavior of lamellopodia that form on the mobile edge of migrating cells. Cell migration is highly dependent on Ca2+ via the actions of numerous Ca2+-dependent effectors including calcineurin, calmodulin, actin, myosin, and actomyosin complex-associated proteins such as integrins (Prevarskaya et al. 2011). Both Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores modulate somatic cell migration (Prevarskaya et al. 2011). Based on these findings in somatic cells, it seems likely that Ca2+ fluxes modulate extension and retraction of trophectoderm projections. This idea is supported by recent evidence that a small conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel, KCNN3, plays a role in mouse blastocyst hatching and F-actin assembly in vitro (Lu et al. 2012).

Delayed implantation in the mouse can be induced by performing an ovariectomy on the morning of pregnancy day 4 followed by progesterone treatment (Yoshinaga and Adams 1966). The resulting dormant blastocysts can then be “activated” by a single dose of estrogen, and implantation occurs. How estrogen activates the blastocyst is not clear, but there is evidence that Ca2+ plays a role. In GnRH neurons, estrogen exposure causes a very rapid increase in the frequency of intracellular Ca2+ spikes via a non-genomic signaling pathway (Terasawa et al. 2009). Similarly, intracellular Ca2+ is mobilized by treatment of dormant mouse blastocysts with either cell-permeant or cell-impermeant forms of estradiol (Yu et al. 2009b). This effect is not dependent on extracellular Ca2+ and is blocked by a PLC inhibitor, suggesting that it occurs as a result of Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive stores.

Implantation is promoted by interactions between embryonic trophectoderm cells and the endometrium that are in part dependent on Ca2+ signals. For example, interaction of extracellular matrix ligands with mouse trophectoderm integrins induces a transient elevation of intracellular Ca2+ that is required to strengthen this interaction (Wang et al. 2002). This Ca2+ release is apparently mediated in large part by activation of trophectoderm PLCγ2, indicating that it occurs via Ca2+ release from intracellular stores rather than downstream of Ca2+ influx (Wang et al. 2007). In human cytotrophoblast cells, histamine promotes invasive behavior by inducing PLC-mediated Ca2+ release, implicating Ca2+ signaling in human implantation (Liu et al. 2004). A role for Ca2+ influx-mediated signaling in implantation was suggested by a report describing inhibition of mouse implantation by uterine horn injection with the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker diltiazem (Banerjee et al. 2009). This idea was confirmed recently by a series of experiments demonstrating a role for a serine protease-activated, amiloride-sensitive sodium channel (ENaC) in implantation in the mouse (Ruan et al. 2012). Endometrial epithelial cells express ENaC, which is apparently activated by blastocyst-derived trypsin, leading to sodium influx and membrane hyperpolarization. Membrane hyperpolarization triggers activation of L-type Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ influx, which is the upstream signal for production of molecules essential for implantation including prostaglandin E2 and cyclooxygenase 2 (Ruan et al. 2012). Taken together, these experiments firmly establish roles for both intracellular Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx in regulating the signaling pathways required for embryo implantation.

Concluding Remarks

Knowledge regarding the critical nature of the Ca2+ signal in driving the events surrounding fertilization and the activation of development has now existed for decades. Much has more recently been discovered regarding the molecular players generating, regulating, and serving as effectors of this signal, though a number of questions remain in this area. However, we are only now beginning to appreciate the importance of the spatiotemporal subtleties that influence how Ca2+ signals are generated and transduced. The development of genetically encoded sensors of Ca2+ and other signaling components that can now be targeted to various subcellular compartments, combined with the development of microscopes and analysis techniques that have an ever-increasing capacity for detection of molecular interactions, will likely support rapid expansion of this area of research. We anticipate that research using these new methods will give us a much better appreciation of the fundamental concepts underlying the signals that transform the sperm and egg into a totipotent embryo.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jim Putney, Miranda Bernhardt, and Humphrey Yao for critical review of the manuscript.

Grant Sponsor: Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences, grant number: Z01ES102985..

Abbreviations

- Ca2+

calcium

- CAMKII

calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- CG

cortical granule

- cPKC

conventional protein kinase C

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- ENaC

serine protease-activated, amiloride-sensitive sodium channel

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ICSI

intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- IP3R1

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, type 1

- MARCKS

myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C substrate

- MII

metaphase of meiosis II

- MYLK2

myosin light chain kinase

- PB2

second polar body

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PLCζ

phospholipase C zeta

- SERCA

sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase

- SOCE

store operated calcium entry

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- Abbott AL, Ducibella T. Calcium and the control of mammalian cortical granule exocytosis. Front Biosci. 2001;6:D792–806. doi: 10.2741/abbott. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajduk A, Ilozue T, Windsor S, Yu Y, Seres KB, Bomphrey RJ, Tom BD, Swann K, Thomas A, Graham C, Zernicka-Goetz M. Rhythmic actomyosin-driven contractions induced by sperm entry predict mammalian embryo viability. Nat Commun. 2011;2:417. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine AF, Faure JE, Cordeiro S, Dumas C, Rougier M, Feijo JA. A calcium influx is triggered and propagates in the zygote as a wavefront during in vitro fertilization of flowering plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(19):10643–10648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180243697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine AF, Faure JE, Dumas C, Feijo JA. Differential contribution of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and Ca2+ influx to gamete fusion and egg activation in maize. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(12):1120–1123. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby MC, Tepikin AV. ER calcium and the functions of intracellular organelles. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12(1):11–17. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au HK, Yeh TS, Kao SH, Tzeng CR, Hsieh RH. Abnormal mitochondrial structure in human unfertilized oocytes and arrested embryos. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1042:177–185. doi: 10.1196/annals.1338.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backs J, Stein P, Backs T, Duncan FE, Grueter CE, McAnally J, Qi X, Schultz RM, Olson EN. The gamma isoform of CaM kinase II controls mouse egg activation by regulating cell cycle resumption. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(1):81–86. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912658106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Padh H, Nivsarkar M. Role of the calcium channel in blastocyst implantation: a novel contraceptive target. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;20(1):43–53. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.2009.20.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Collins TJ, Peppiatt CM, Prothero LS, MacKenzie L, De Smet P, Travers M, Tovey SC, Seo JT, Berridge MJ, Ciccolini F, Lipp P. Calcium signalling--an overview. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2001;12(1):3–10. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandman O, Liou J, Park WS, Meyer T. STIM2 is a feedback regulator that stabilizes basal cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels. Cell. 2007;131(7):1327–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart AD, Xiong B, Baibakov B, Jimenez-Movilla M, Dean J. Ovastacin, a cortical granule protease, cleaves ZP2 in the zona pellucida to prevent polyspermy. J Cell Biol. 2012;197(1):37–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201112094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X. Molecular evolution and functional divergence of the Ca2+ sensor protein in store-operated Ca2+ entry: stromal interaction molecule. PLoS One. 2007;2(7):e609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K, Swann K. Ca2+ oscillations stimulate an ATP increase during fertilization of mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 2006;298(1):225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie M. Green fluorescent protein. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;62(4):651–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb08712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson KS, Cobbold PH. Phorbol ester and sperm activate mouse oocytes by inducing sustained oscillations in cell Ca2+ Nature. 1985;316(6028):541–542. doi: 10.1038/316541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbertson KS, Whittingham DG, Cobbold PH. Free Ca2+ increases in exponential phases during mouse oocyte activation. Nature. 1981;294(5843):754–757. doi: 10.1038/294754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S, Hall DD, Hell JW. Supramolecular assemblies and localized regulation of voltage-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(2):411–452. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day ML, McGuinness OM, Berridge MJ, Johnson MH. Regulation of fertilization-induced Ca(2+) spiking in the mouse zygote. Cell Calcium. 2000;28(1):47–54. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Koninck P, Schulman H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science. 1998;279(5348):227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi R, Shirakawa H, Oda S, Mohri T, Miyazaki S. Spatiotemporal analysis of Ca(2+) waves in relation to the sperm entry site and animal-vegetal axis during Ca(2+) oscillations in fertilized mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 2000;218(2):299–313. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M, Kishikawa H, Yanagimachi R, Kopf GS, Schultz RM, Williams CJ. Chromatin-mediated cortical granule redistribution is responsible for the formation of the cortical granule-free domain in mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 2003;257(1):166–176. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducibella T, Anderson E. Cell shape and membrane changes in the eight-cell mouse embryo: prerequisites for morphogenesis of the blastocyst. Dev Biol. 1975;47(1):45–58. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducibella T, Huneau D, Angelichio E, Xu Z, Schultz RM, Kopf GS, Fissore R, Madoux S, Ozil JP. Egg-to-embryo transition is driven by differential responses to Ca(2+) oscillation number. Dev Biol. 2002;250(2):280–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumollard R, Duchen M, Sardet C. Calcium signals and mitochondria at fertilisation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17(2):314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumollard R, Marangos P, Fitzharris G, Swann K, Duchen M, Carroll J. Sperm-triggered [Ca2+] oscillations and Ca2+ homeostasis in the mouse egg have an absolute requirement for mitochondrial ATP production. Development. 2004;131(13):3057–3067. doi: 10.1242/dev.01181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes R, Tsuda C, Perumalsamy AL, Naranian T, Chong J, Acton BM, Tong ZB, Nelson LM, Jurisicova A. NLRP5 mediates mitochondrial function in mouse oocytes and embryos. Biol Reprod. 2012;86(5):138, 131–110. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.093583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441(7090):179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzHarris G, Larman M, Richards C, Carroll J. An increase in [Ca2+]i is sufficient but not necessary for driving mitosis in early mouse embryos. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 19):4563–4575. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzHarris G, Marangos P, Carroll J. Changes in endoplasmic reticulum structure during mouse oocyte maturation are controlled by the cytoskeleton and cytoplasmic dynein. Dev Biol. 2007;305(1):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara T, Nakada K, Shirakawa H, Miyazaki S. Development of inositol trisphosphate-induced calcium release mechanism during maturation of hamster oocytes. Dev Biol. 1993;156(1):69–79. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner AJ, Williams CJ, Evans JP. Establishment of the mammalian membrane block to polyspermy: evidence for calcium-dependent and -independent regulation. Reproduction. 2007;133(2):383–393. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Fernandez C, Pozo-Guisado E, Ganan-Parra M, Perianes MJ, Alvarez IS, Martin-Romero FJ. Relocalization of STIM1 in mouse oocytes at fertilization: early involvement of store-operated calcium entry. Reproduction. 2009;138(2):211–221. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales DS, Jones JM, Pinyopummintr T, Carnevale EM, Ginther OJ, Shapiro SS, Bavister BD. Trophectoderm projections: a potential means for locomotion, attachment and implantation of bovine, equine and human blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(12):2739–2745. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(6):3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbiner BM. Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(8):622–634. doi: 10.1038/nrm1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halet G, Tunwell R, Parkinson SJ, Carroll J. Conventional PKCs regulate the temporal pattern of Ca2+ oscillations at fertilization in mouse eggs. J Cell Biol. 2004;164(7):1033–1044. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao ZD, Liu S, Wu Y, Wan PC, Cui MS, Chen H, Zeng SM. Abnormal changes in mitochondria, lipid droplets, ATP and glutathione content, and Ca(2+) release after electro-activation contribute to poor developmental competence of porcine oocyte during in vitro ageing. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21(2):323–332. doi: 10.1071/rd08157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CL, Damiani P, Parys JB, Fissore RA. Calcium, calcium release receptors, and meiotic resumption in bovine oocytes. Biol Reprod. 1997;57(5):1245–1255. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.5.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn LV, Young RA. The activation of ultra-violet rays on Arbacia egg protoplasm. Physiol Zool. 1930;3:330–341. [Google Scholar]

- Hewavitharana T, Deng X, Soboloff J, Gill DL. Role of STIM and Orai proteins in the store-operated calcium signaling pathway. Cell Calcium. 2007;42(2):173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi H, Knott JG, Schultz RM, Williams CJ. Alterations of PLCbeta1 in mouse eggs change calcium oscillatory behavior following fertilization. Dev Biol. 2007;312(1):321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi H, Takahashi E, Hiroi M, Doi K. Aging-related changes in calcium oscillations in fertilized mouse oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;48(3):383–390. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199711)48:3<383::AID-MRD12>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igusa Y, Miyazaki S. Effects of altered extracellular and intracellular calcium concentration on hyperpolarizing responses of the hamster egg. J Physiol. 1983;340:611–632. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J, Parrington J, Fissore RA. PLCzeta and its role as a trigger of development in vertebrates. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78(10–11):846–853. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Bierle BM, Gallicano GI, Capco DG. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and calmodulin: regulators of the meiotic spindle in mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 1998;204(2):464–477. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KT. Ca2+ oscillations in the activation of the egg and development of the embryo in mammals. Int J Dev Biol. 1998;42(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KT, Carroll J, Whittingham DG. Ionomycin, thapsigargin, ryanodine, and sperm induced Ca2+ release increase during meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(12):6671–6677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KT, Whittingham DG. A comparison of sperm- and IP3-induced Ca2+ release in activated and aging mouse oocytes. Dev Biol. 1996;178(2):229–237. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalive M, Faust JJ, Koeneman BA, Capco DG. Involvement of the PKC family in regulation of early development. Mol Reprod Dev. 2010;77(2):95–104. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashir J, Konstantinidis M, Jones C, Lemmon B, Lee HC, Hamer R, Heindryckx B, Deane CM, De Sutter P, Fissore RA, Parrington J, Wells D, Coward K. A maternally inherited autosomal point mutation in human phospholipase C zeta (PLCzeta) leads to male infertility. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(1):222–231. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T, Ueyama T, Lange I, Feske S, Saito N. Protein kinase C-induced phosphorylation of Orai1 regulates the intracellular Ca2+ level via the store-operated Ca2+ channel. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(33):25720–25730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.022996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline D, Kline JT. Repetitive calcium transients and the role of calcium in exocytosis and cell cycle activation in the mouse egg. Dev Biol. 1992;149(1):80–89. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90265-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline D, Mehlmann L, Fox C, Terasaki M. The cortical endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of the mouse egg: localization of ER clusters in relation to the generation of repetitive calcium waves. Dev Biol. 1999;215(2):431–442. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott JG, Gardner AJ, Madgwick S, Jones KT, Williams CJ, Schultz RM. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II triggers mouse egg activation and embryo development in the absence of Ca2+ oscillations. Dev Biol. 2006;296(2):388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott JG, Kurokawa M, Fissore RA, Schultz RM, Williams CJ. Transgenic RNA interference reveals role for mouse sperm phospholipase Czeta in triggering Ca2+ oscillations during fertilization. Biol Reprod. 2005;72(4):992–996. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.036244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh S, Lee K, Wang C, Cabot RA, Machaty Z. STIM1 regulates store-operated Ca2+ entry in oocytes. Dev Biol. 2009;330(2):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono T, Jones KT, Bos-Mikich A, Whittingham DG, Carroll J. A cell cycle-associated change in Ca2+ releasing activity leads to the generation of Ca2+ transients in mouse embryos during the first mitotic division. J Cell Biol. 1996;132(5):915–923. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.5.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi Z, Fukami K, Shikano T, Oda S, Nakamura Y, Takenawa T, Miyazaki S. Recombinant phospholipase Czeta has high Ca2+ sensitivity and induces Ca2+ oscillations in mouse eggs. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(11):10408–10412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa M, Sato K, Smyth J, Wu H, Fukami K, Takenawa T, Fissore RA. Evidence that activation of Src family kinase is not required for fertilization-associated [Ca2+]i oscillations in mouse eggs. Reproduction. 2004;127(4):441–454. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange K, Gartzke J. F-actin-based Ca signaling-a critical comparison with the current concept of Ca signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209(2):270–287. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA, Saleh SN, Albert AP. Role of phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and diacylglycerol in regulating native TRPC channel proteins in vascular smooth muscle. Cell Calcium. 2009;45(6):574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Wang C, Machaty Z. STIM1 is required for Ca2+ signaling during mammalian fertilization. Dev Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Meyer T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol. 2005;15(13):1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Hammar K, Smith PJ, Inoue S, Keefe DL. Mitochondrial modulation of calcium signaling at the initiation of development. Cell Calcium. 2001;30(6):423–433. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2001.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Kilburn BA, Leach RE, Romero R, Paria BC, Armant DR. Histamine enhances cytotrophoblast invasion by inducing intracellular calcium transients through the histamine type-1 receptor. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;68(3):345–353. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YC, Ding GL, Yang J, Zhang YL, Shi S, Zhang RJ, Zhang D, Pan JX, Sheng JZ, Huang HF. Small-conductance calcium-activated K(+) channels 3 (SK3) regulate blastocyst hatching by control of intracellular calcium concentration. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1421–1430. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machaca K, Haun S. Store-operated calcium entry inactivates at the germinal vesicle breakdown stage of Xenopus meiosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(49):38710–38715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007887200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machaca K, Haun S. Induction of maturation-promoting factor during Xenopus oocyte maturation uncouples Ca(2+) store depletion from store-operated Ca(2+) entry. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(1):75–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machaty Z, Ramsoondar JJ, Bonk AJ, Bondioli KR, Prather RS. Capacitative calcium entry mechanism in porcine oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2002;66(3):667–674. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleszewski M, Kimura Y, Yanagimachi R. Sperm membrane incorporation into oolemma contributes to the oolemma block to sperm penetration: evidence based on intracytoplasmic sperm injection experiments in the mouse. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;44(2):256–259. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199606)44:2<256::AID-MRD16>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malli R, Frieden M, Trenker M, Graier WF. The role of mitochondria for Ca2+ refilling of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(13):12114–12122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409353200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JS, Lowther KM, Mehlmann LM. Reorganization of the endoplasmic reticulum and development of Ca2+ release mechanisms during meiotic maturation of human oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2010;83(4):578–583. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.085985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoulaki S, Matson S, Ducibella T. Fertilization stimulates long-lasting oscillations of CaMKII activity in mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 2004;272(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Romero FJ, Ortiz-de-Galisteo JR, Lara-Laranjeira J, Dominguez-Arroyo JA, Gonzalez-Carrera E, Alvarez IS. Store-operated calcium entry in human oocytes and sensitivity to oxidative stress. Biol Reprod. 2008;78(2):307–315. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.064527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson S, Markoulaki S, Ducibella T. Antagonists of myosin light chain kinase and of myosin II inhibit specific events of egg activation in fertilized mouse eggs. Biol Reprod. 2006;74(1):169–176. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.046409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazia D. The release of calcium in Arbacia eggs upon fertilization. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1937;10:291–304. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis LK, Albertini DF, Kinsey WH. Localized activation of Src-family protein kinases in the mouse egg. Dev Biol. 2007;306(1):241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis LK, Carroll DJ, Kinsey WH. Protein tyrosine kinase signaling during oocyte maturation and fertilization. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78(10–11):831–845. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness OM, Moreton RB, Johnson MH, Berridge MJ. A direct measurement of increased divalent cation influx in fertilised mouse oocytes. Development. 1996;122(7):2199–2206. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.7.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlmann LM, Carpenter G, Rhee SG, Jaffe LA. SH2 domain-mediated activation of phospholipase Cgamma is not required to initiate Ca2+ release at fertilization of mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 1998;203(1):221–232. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlmann LM, Chattopadhyay A, Carpenter G, Jaffe LA. Evidence that phospholipase C from the sperm is not responsible for initiating Ca(2+) release at fertilization in mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 2001;236(2):492–501. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlmann LM, Jaffe LA. SH2 domain-mediated activation of an SRC family kinase is not required to initiate Ca2+ release at fertilization in mouse eggs. Reproduction. 2005;129(5):557–564. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlmann LM, Kline D. Regulation of intracellular calcium in the mouse egg: calcium release in response to sperm or inositol trisphosphate is enhanced after meiotic maturation. Biol Reprod. 1994;51(6):1088–1098. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlmann LM, Mikoshiba K, Kline D. Redistribution and increase in cortical inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors after meiotic maturation of the mouse oocyte. Dev Biol. 1996;180(2):489–498. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlmann LM, Terasaki M, Jaffe LA, Kline D. Reorganization of the endoplasmic reticulum during meiotic maturation of the mouse oocyte. Dev Biol. 1995;170(2):607–615. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao YL, Stein P, Jefferson WN, Padilla-Banks E, Williams CJ. Calcium influx-mediated signaling is required for complete mouse egg activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(11):4169–4174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112333109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaut MA, Williams CJ, Schultz RM. Phosphorylated MARCKS: a novel centrosome component that also defines a peripheral subdomain of the cortical actin cap in mouse eggs. Dev Biol. 2005;280(1):26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minta A, Kao JP, Tsien RY. Fluorescent indicators for cytosolic calcium based on rhodamine and fluorescein chromophores. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(14):8171–8178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S, Hashimoto N, Yoshimoto Y, Kishimoto T, Igusa Y, Hiramoto Y. Temporal and spatial dynamics of the periodic increase in intracellular free calcium at fertilization of golden hamster eggs. Dev Biol. 1986;118(1):259–267. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S, Yuzaki M, Nakada K, Shirakawa H, Nakanishi S, Nakade S, Mikoshiba K. Block of Ca2+ wave and Ca2+ oscillation by antibody to the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in fertilized hamster eggs. Science. 1992;257(5067):251–255. doi: 10.1126/science.1321497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GD, Ayabe T, Visconti PE, Schultz RM, Kopf GS. Roles of heterotrimeric and monomeric G proteins in sperm-induced activation of mouse eggs. Development. 1994;120(11):3313–3323. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.11.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SW, di Capite J, Singaravelu K, Parekh AB. Sustained activation of the tyrosine kinase Syk by antigen in mast cells requires local Ca2+ influx through Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(46):31348–31355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oancea E, Meyer T. Protein kinase C as a molecular machine for decoding calcium and diacylglycerol signals. Cell. 1998;95(3):307–318. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81763-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh JS, Susor A, Conti M. Protein tyrosine kinase Wee1B is essential for metaphase II exit in mouse oocytes. Science. 2011;332(6028):462–465. doi: 10.1126/science.1199211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozil JP, Banrezes B, Toth S, Pan H, Schultz RM. Ca2+ oscillatory pattern in fertilized mouse eggs affects gene expression and development to term. Dev Biol. 2006;300(2):534–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozil JP, Markoulaki S, Toth S, Matson S, Banrezes B, Knott JG, Schultz RM, Huneau D, Ducibella T. Egg activation events are regulated by the duration of a sustained [Ca2+]cyt signal in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2005;282(1):39–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry AC, Verlhac MH. Second meiotic arrest and exit in frogs and mice. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(3):246–251. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pey R, Vial C, Schatten G, Hafner M. Increase of intracellular Ca2+ and relocation of E-cadherin during experimental decompaction of mouse embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(22):12977–12982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.12977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasher DC, Eckenrode VK, Ward WW, Prendergast FG, Cormier MJ. Primary structure of the Aequorea victoria green-fluorescent protein. Gene. 1992;111(2):229–233. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90691-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast FG, Mann KG. Chemical and physical properties of aequorin and the green fluorescent protein isolated from Aequorea forskalea. Biochemistry. 1978;17(17):3448–3453. doi: 10.1021/bi00610a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y. Calcium in tumour metastasis: new roles for known actors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(8):609–618. doi: 10.1038/nrc3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW., Jr A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 1986;7(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SG, Bae YS. Regulation of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isozymes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(24):15045–15048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway EB, Gilkey JC, Jaffe LF. Free calcium increases explosively in activating medaka eggs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74(2):623–627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S, Safrina O, Kozak JA, Wagner SL, Cahalan MD, Velicelebi G, Stauderman KA. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(3):435–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan YC, Guo JH, Liu X, Zhang R, Tsang LL, Dong JD, Chen H, Yu MK, Jiang X, Zhang XH, Fok KL, Chung YW, Huang H, Zhou WL, Chan HC. Activation of the epithelial Na(+) channel triggers prostaglandin E(2) release and production required for embryo implantation. Nat Med. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nm.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]