Abstract

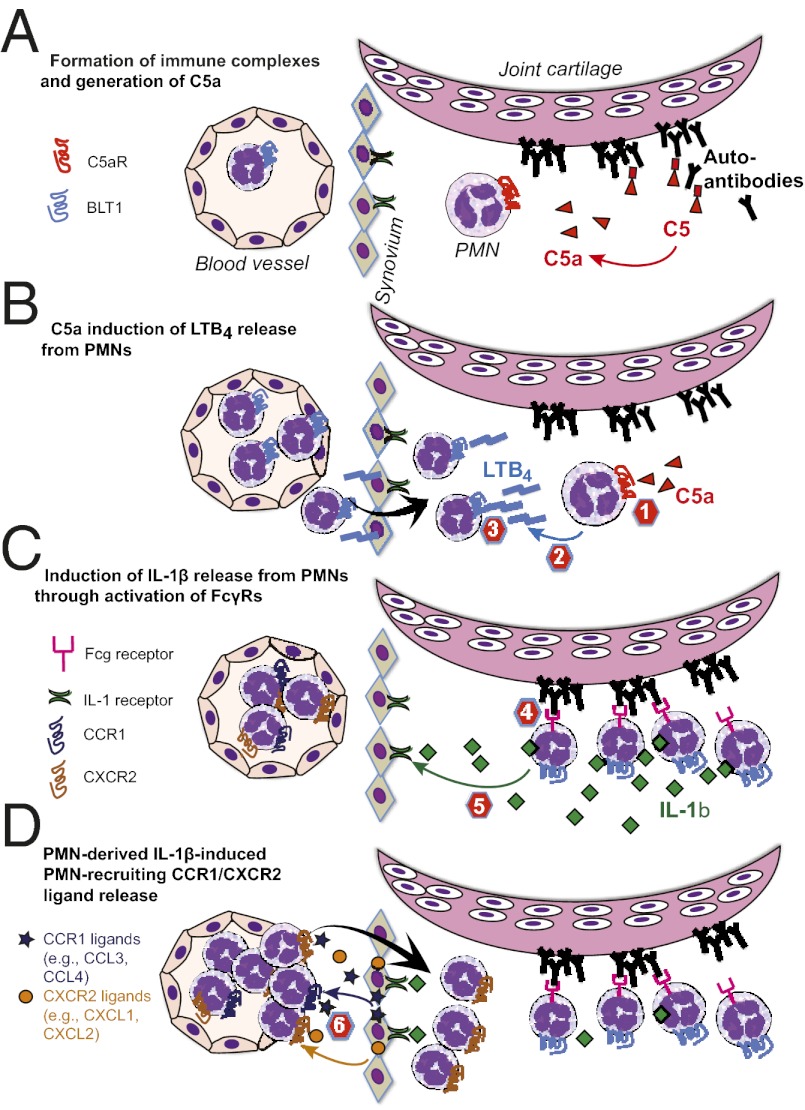

Neutrophil recruitment into the joint is a hallmark of inflammatory arthritides, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In a mouse model of autoantibody-induced inflammatory arthritis, neutrophils infiltrate the joint via multiple chemoattractant receptors, including the leukotriene B4 (LTB4) receptor BLT1 and the chemokine receptors CCR1 and CXCR2. Once in the joint, neutrophils perpetuate their own recruitment by releasing LTB4 and IL-1β, presumably after activation by immune complexes deposited on joint structures. Two pathways by which immune complexes may activate neutrophils include complement fixation, resulting in the generation of C5a, and direct engagement of Fcγ receptors (FcγRs). Previous investigations showed that this model of autoantibody-induced arthritis requires the C5a receptor C5aR and FcγRs, but the simultaneous necessity for both pathways was not understood. Here we show that C5aR and FcγRs work in sequence to initiate and sustain neutrophil recruitment in vivo. Specifically, C5aR activation of neutrophils is required for LTB4 release and early neutrophil recruitment into the joint, whereas FcγR engagement upon neutrophils induces IL-1β release and subsequent neutrophil-active chemokine production, ensuring continued inflammation. These findings support the concept that immune complex-mediated leukocyte activation is not composed of overlapping and redundant pathways, but that each element serves a distinct and critical function in vivo, culminating in tissue inflammation.

Sequential cascades of chemoattractants are a hallmark of immune cell recruitment in sterile inflammation (1, 2). We have recently shown that a lipid–cytokine–chemokine cascade, consisting of leukotriene B4 (LTB4)–IL-1β–neutrophil-active CCR1 and CXCR2 chemokine ligands drives neutrophil [polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN)] recruitment into the joint in a model of autoantibody-induced arthritis (3, 4). These mediators act in a nonredundant, sequential manner to regulate the recruitment of PMNs into the joint. Surprisingly, PMNs themselves are the predominant source of LTB4 and IL-1β in this model, suggesting that PMNs can be central choreographers of inflammation, rather than pure effector cells (3, 5). Orchestration of PMN recruitment requires highly organized temporal and spatial patterns of chemoattractant expression (3, 6–8). The molecular mechanisms that achieve this sophisticated organization, however, are unknown and presumably differ depending on the individual pathologic stimulus and the specific tissue site. In this model of autoantibody-induced arthritis, despite progress in identifying the chemoattractants driving PMN recruitment, the specific stimuli inducing the sequential release of LTB4 and IL-1β have not been defined.

Arthritis is induced in this model by the transfer of serum from K/BxN mice into recipient mice and is therefore often referred to as the “K/BxN serum transfer model.” This model of autoantibody-induced arthritis is a prototypical model for immune complex (IC)-induced PMN-driven inflammation. K/BxN serum contains autoantibodies against glucose 6-phosphate isomerase (GPI), which form ICs on the cartilage surface (9–11). Notably, the classical pathway of complement activation does not play a role in this model, which, however, requires the complement factors C3 and C5 (9). C3 and IgG depositions colocalize in arthritic joints, implying that C3b-IgG complexes are formed on the cartilage surface, which activate complement via the alternative pathway finally cleaving C5a from C5 (9).

In the K/BxN serum transfer model, adaptive immunity is bypassed and arthritis is independent of T and B lymphocytes and is instead dependent on innate immune cells and PMNs in particular (12–14). Several effector mechanisms are critically involved in the generation of arthritis in this model. In addition to LTB4 and IL-1β, the C5a receptor (C5aR) and Fcγ receptors (FcγRs) are both also required for the development of arthritis. However, how these cell surface receptors and soluble mediators interact at the cellular level to initiate arthritis is not known.

C5aR and FcγRs are central mediators of innate immunity and key for the execution of the effector phase of immune responses triggered by immune complexes (15, 16). One emerging paradigm suggests that the functions of C5aR and FcγR are intertwined and that a main function of C5aR is to lower the threshold for FcγR activation, which in turn executes the actual effector response (16–21). The relevance of this cross-regulation in vivo has been shown for autoimmune hemolytic anemia and IC-induced lung inflammation, where C5aR regulation of FcγR function occurs in Kupffer cells and alveolar macrophages, respectively (18, 19). In the latter model, this regulation enables alveolar macrophages to more efficiently direct PMN recruitment into the lung (18). However, it is not known whether this paradigm also holds true for immune responses that are not coordinated by tissue resident immune cells, and it is not known which effector mechanisms downstream of C5aR and FcγRs are required for disease induction and progression.

Although it has been a matter of debate, most recent data suggest that tissue mast cells are not required for autoantibody-induced arthritis (22). The role of macrophages in this model is still debated, as macrophage-deficient op/op mice are fully susceptible to arthritis (23), whereas clodronate depletion of macrophages protects against arthritis (24). Natural killer (NK) cells and dendritic cells (DCs) are also not required for arthritis in this model (25), but compelling data suggest that PMNs are indispensable (12–14), and that C5aR and FcγR function in PMNs is required to initiate arthritis (13). However, the precise roles of C5aR and FcγR and the downstream effects of their activation on PMNs critical for the development of arthritis in this model have not been defined.

In this study, we set out to identify the inducers of LTB4 and IL-1β release from PMNs required for the pathogenesis of autoantibody-induced arthritis in this model. We hypothesized that the requirement of C5aR and FcγRs may be directly connected to the release of LTB4 and IL-1β from PMNs. Here, we demonstrate that C5aR and FcγRs on PMNs each separately contributes to the initiation of arthritis by inducing the release of LTB4 and IL-1β from PMNs in vivo, respectively. These findings support the concept that immune complex-mediated leukocyte activation is not composed of seemingly overlapping and redundant pathways, but that each element serves a distinct and critical function in vivo in a sequential, nonredundant manner culminating in tissue inflammation. Additionally, these results highlight how highly organized temporal and spatial patterns of chemoattractant expression can be achieved in vivo to orchestrate PMN recruitment and exemplify how PMNs can choreograph their own recruitment and inflammation.

Results

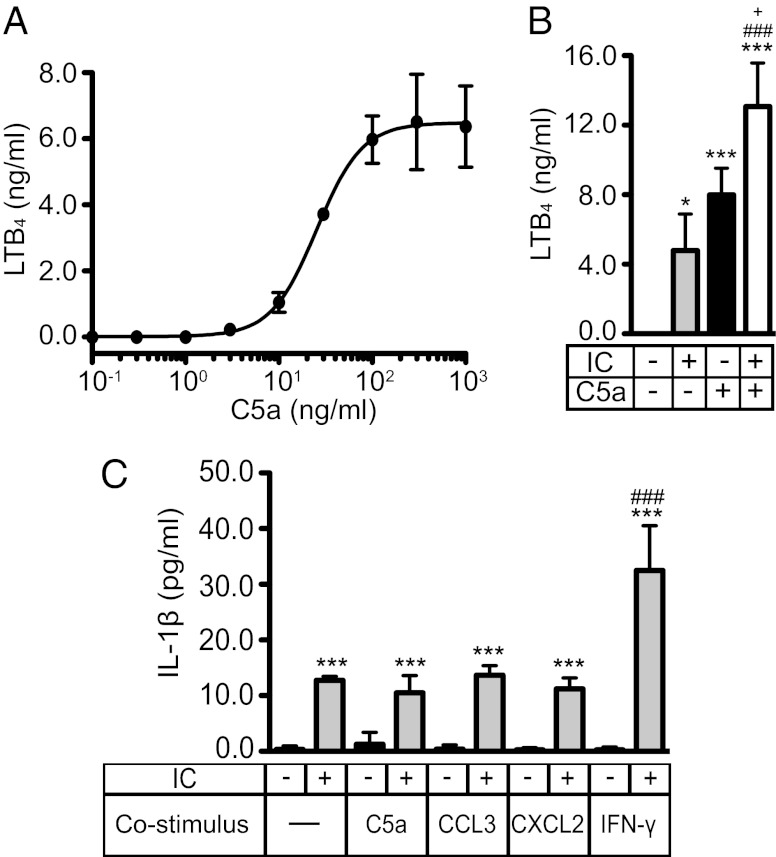

C5a and ICs Induce the Release of LTB4 from PMNs in Vitro.

Because PMNs are a critical source of LTB4 in autoantibody-induced arthritis (5), we tested whether C5a and immobilized ICs induce the release of LTB4 from resting bone marrow (BM) PMNs in vitro. C5a dose-dependently induced the release of LTB4 into the medium with levels of LTB4 plateauing at ∼6 ng/mL following 1 h of C5a stimulation (Fig. 1A). The EC50 of C5a-induced LTB4 release was 25 ng/mL C5a, which is comparable to the reported C5a concentration present in arthritic joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (26, 27). LTB4 release was persistent and after 18 h of C5a (100 ng/mL) stimulation, 3 ng/mL LTB4 was still found in the medium (Fig. S1A). Likewise, we examined the effect of immobilized IgG1 ICs on the release of LTB4. Stimulation of PMNs with ICs, but not with antigen or antibody alone, induced the release of LTB4 (Fig. S1B).

Fig. 1.

C5a and ICs induce LTB4 and IL-1β release from resting PMNs. (A) Dose–response analysis for the release of LTB4 from PMNs after stimulation with varying concentrations of murine recombinant C5a for 1 h. The EC50 of LTB4 induction by C5a is 25.4 ng/mL. (B) Release of LTB4 from PMNs after stimulation with IC, C5a (10 ng/mL), or both combined for 1 h. (C) Release of IL-1β from PMNs after stimulation with IC, C5a (100 ng/mL), CCL3 (100 ng/mL), CXCL2 (100 ng/mL), and IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) alone or combined for 18 h. All data represent concentrations in the supernatant determined by ELISA, shown as mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiments). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with unstimulated control, ### P < 0.001 compared with stimulation with IC, and +P < 0.05 compared with stimulation with C5a.

Next, we costimulated PMNs with ICs and C5a, which elicited an additive effect on the induction of LTB4 (Fig. 1B). We also tested the effect of CCL3, CXCL2, IL-1β, fMLF, GM-CSF, and 2-thio-PAF, a stable analog of PAF, on the release of LTB4. We found that none of these stimuli had an effect (Fig. S1C), which indicates that LTB4 induction in resting PMNs is specific to certain stimuli.

To ensure that LTB4 was specifically induced by activation of C5aR and FcγRs, respectively, the release of LTB4 from C5ar−/− and Fcer1g−/− PMNs was tested. Fcer1g−/− PMNs are deficient in FcRγ, the common signaling chain of activating Fcγ receptors in the mouse. As expected, C5ar−/− PMNs did not release LTB4 after C5a stimulation, but released LTB4 after IC stimulation. Conversely, Fcer1g−/− PMNs released LTB4 only when stimulated with C5a (Fig. S1D). LTB4 release was not impaired in Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4-defcient (Tlr4−/−) PMNs, eliminating the possibility that activation of PMNs by LPS contamination played a role in C5a-induced LTB4 release (Fig. S1E).

We also determined whether C5a induces the release of IL-1β from PMNs in vitro and whether C5a affects the recently described induction of IL-1β in PMNs by ICs (3). In contrast to IC stimulation, C5a had no effect on the release of IL-1β, nor did CCL3 or CXCL2 (Fig. 1C). However, IFN-γ did augment IC-induced release of IL-1β (Fig. 1C).

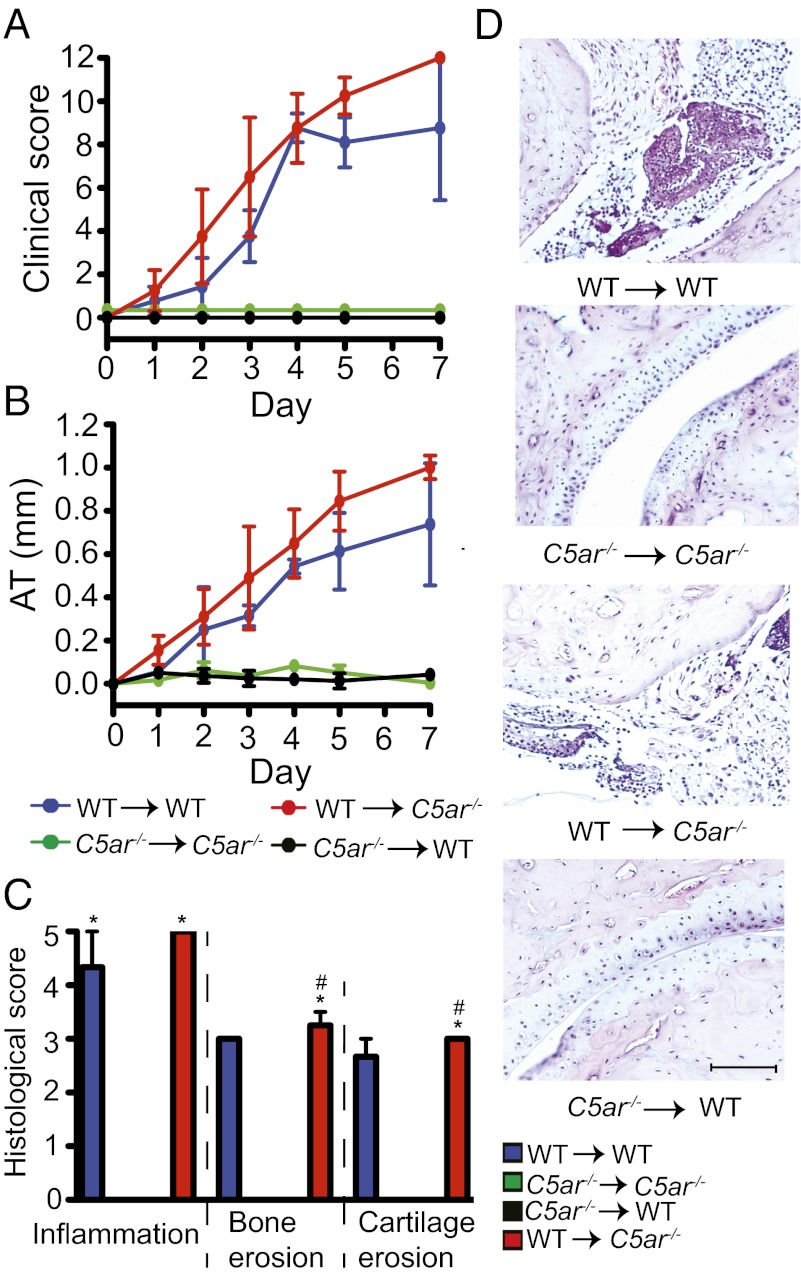

C5aR on Radiosensitive Cells Is Necessary and Sufficient for Arthritis.

We developed a protocol for the generation of bone marrow chimeric (BMC) mice that replaces recipient PMNs with donor PMNs while leaving tissue mast cells and tissue macrophages of recipient origin at the time the mice are used for experiments. Using this protocol, we addressed which cells must express C5aR for the induction of arthritis by generating BMC mice using WT and C5ar−/− mice. After bone marrow engraftment, chimeric mice were subjected to K/BxN serum transfer and arthritis was clinically evaluated (Fig. 2 A and B). As expected, BMC mice that had WT bone marrow transplanted into (→) WT recipient mice were susceptible to arthritis. In contrast, C5ar−/− → C5ar−/− controls were resistant to arthritis as were C5ar−/− → WT BMC. However, WT → C5ar−/− BMC developed arthritis indistinguishable from WT → WT controls. Consistent with these clinical observations, histological analysis showed the ankles of WT → WT controls and WT → C5ar−/− BMC were severely inflamed, whereas the joints of C5ar−/− → WT BMC and C5ar−/− → C5ar−/− controls showed no signs of arthritis (Fig. 2 C and D). These results indicate that C5aR expression on radiosensitive cells is necessary and sufficient for arthritis, whereas C5aR on radioresistant cells does not contribute to the development of arthritis.

Fig. 2.

C5aR on radiosensitive cells is necessary and sufficient for arthritis. (A and B) Arthritis in BMC of WT and C5ar−/− mice. Clinical score and ankle thickening (AT) were assessed daily (n = 4 mice per group). WT → WT or WT → C5ar−/− vs. C5ar−/− → C5ar −/− or C5ar−/− → WT, P < 0.001 in clinical score and in AT. (C) Histological scoring of ankles from mice in A and B. *P < 0.05 compared with C5ar−/− → C5ar−/−, and #P < 0.05 compared with C5ar−/− → WT. (D) Respective representative sections. One representative of two independent experiments is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

To exclude that C5aR on mast cells plays a role, C5ar−/− mice served as recipients and Kitw/Kitw-v mice, a mast cell-deficient strain resistant to arthritis (28), served as BM donors. After serum transfer, Kitw/Kitw-v → C5ar−/− BMC developed clinical signs of arthritis and histopathological evidence of inflammation and bone and cartilage erosion indistinguishable from those of WT → C5ar−/− BMC (Fig. S2 A–D). In this experiment, chimeric mice have no functional mast cells expressing C5aR and yet were fully susceptible to arthritis. These results suggest that C5aR on mast cells is not required for arthritis.

Osteoblasts are radiosensitive, express C5aR, and may modulate arthritis (29, 30). To determine whether C5aR on osteoblasts contributes to arthritis, C5ar−/− recipients were reconstituted with BM from osteoblast-deficient (osteoprotegerin-deficient; Tnfrdf11b−/−) mice. Tnfrdf11b−/− → C5ar−/− BMC were fully susceptible to arthritis (Fig. S2 A and B), demonstrating that C5aR on osteoblasts does not contribute to arthritis. Likewise, histological analysis of Tnfrdf11b−/− → C5ar−/− BMC revealed severe signs of inflammation and cartilage and bone erosions (Fig. S2 C and D).

We attempted to restore arthritis in C5ar−/− mice by adoptive transfer of WT PMNs or whole WT BM. For the PMN transfer experiments, 107 WT PMNs were injected daily on days 0–3 into each recipient C5ar−/− mouse (Fig. S2 E and F). For the BM transfer experiments, each individual C5ar−/− recipient mouse obtained the total BM of one WT mouse daily on days 0–3 (Fig. S2 G and H). Neither adoptive transfer experiment restored arthritis susceptibility to C5ar−/− mice. These data may suggest that there is another C5aR-expressing radiosensitive cell that is not present in the BM, or is not present in high enough numbers in the BM, that is required for the induction of arthritis. Alternatively, these data may also suggest that C5aR is required on the majority of PMNs entering the joint, as we have found that after adoptive PMN transfer, the percentage of adoptively transferred PMNs in the blood and joint of recipient mice is very low (<2% of blood PMNs) (4).

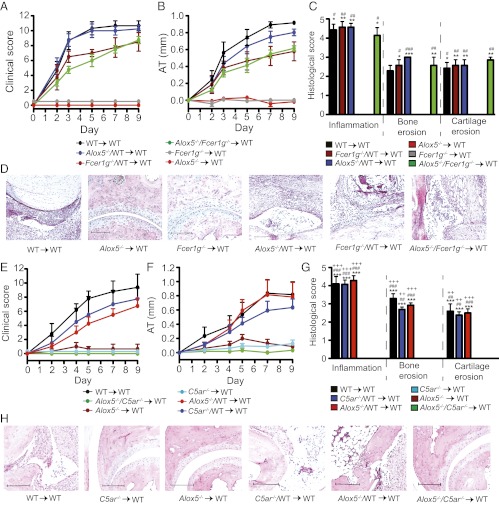

5-Lipoxygenase Must Be Coexpressed with C5aR in PMNs but Not with FcRγ for Arthritis.

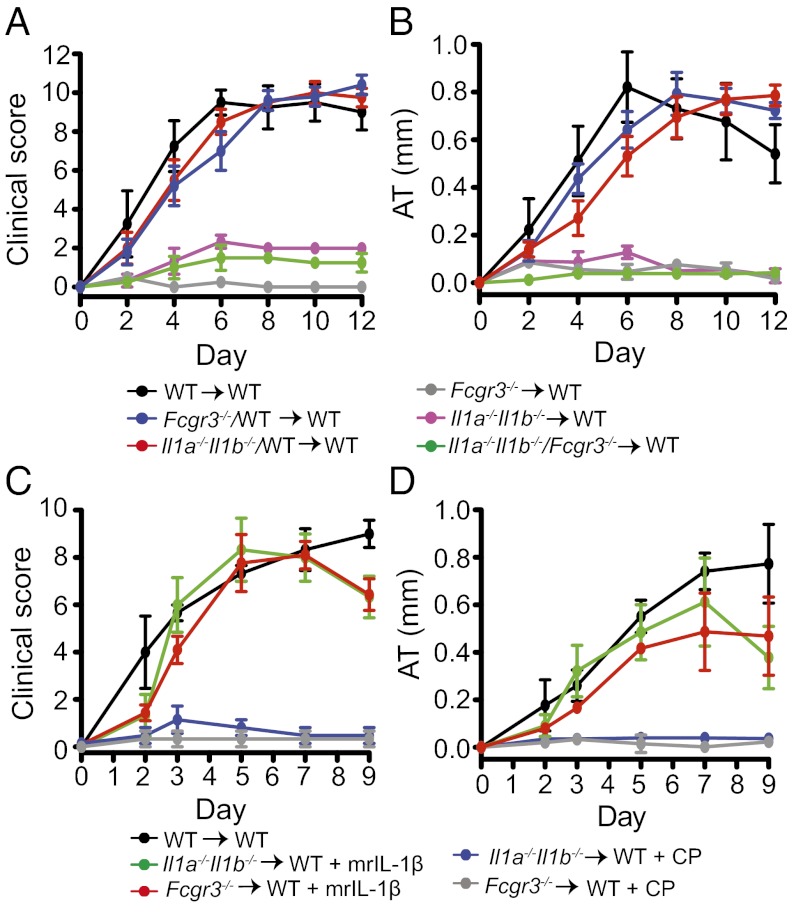

We have shown that C5aR on radiosensitive cells is required for arthritis. Likewise, it was shown previously that 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO), an essential enzyme for LTB4 synthesis, is required in radiosensitive cells and that 5-LO expression in PMNs alone is sufficient for arthritis (5). Now we asked whether 5-LO in PMNs is activated by C5a and/or ICs. To this end, we used mice deficient in 5-LO (Alox5−/−) and generated C5ar−/−/Alox5−/− → WT and Alox5−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT mixed BMC with donor BMs used in a 1:1 ratio and subjected these mice to serum transfer. Whereas Alox5−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT BMC were susceptible to arthritis (Fig. 3 A and B), C5ar−/−/Alox5−/− → WT BMC were resistant (Fig. 3 E and F). At the same time, C5ar−/−/WT → WT and Alox5−/−/WT → WT mixed BMC developed arthritis indistinguishable from WT → WT controls (Fig. 3 E and F). These clinical results were also reflected in the histological analysis (Fig. 3 C, D, G, and H). In Alox5−/−/C5aR−/− → WT mixed BMC there are no radiosensitive cells simultaneously carrying C5aR and capable of synthesizing LTB4. Hence, Alox5−/−/C5aR−/− → WT BMC cannot produce significant amounts of LTB4 if its release mainly depends on C5a. Our results therefore indicate that in vivo, C5aR and 5-LO must be coexpressed in the same cell and that C5a directly induces the release of LTB4 from radiosensitive cells. In contrast, IC-induced LTB4 release from radiosensitive cells is neither required nor sufficient for arthritis, suggesting that in vivo C5a is the only critical inducer of LTB4 in this model.

Fig. 3.

5-LO/C5aR but not 5-LO/FcRγ coexpression in radiosensitive cells is required for arthritis. (A and B) Arthritis in WT → WT, Fcer1g−/− → WT, Alox5−/− → WT, Alox5−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT, Alox5−/−/WT → WT, and Fcer1g−/−/WT → WT BMC (n = 3–4 mice per group; one representative of two independent experiments shown). P < 0.001 in clinical score and AT for WT → WT, Alox5−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT, Alox5−/−/WT → WT, or Fcer1g−/−/WT → WT vs. Fcer1g−/− → WT, or Alox5−/− → WT. (C) Histological score of ankles from mice in A and B (n = 9–15 mice per group; data compiled from three independent experiments). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 for indicated group vs. Alox5−/− → WT; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 for indicated group vs. Fcer1g−/− → WT. (D) Respective representative sections. (E and F) Arthritis in WT → WT, C5ar−/− → WT, Alox5−/− → WT, Alox5−/−/C5ar−/− → WT, Alox5−/−/WT → WT, and C5ar−/−/WT → WT BMC (n = 4–5 mice per group; one representative of three independent experiments is shown). P < 0.001 in clinical score for WT → WT, Alox5−/−/WT → WT, or C5ar−/−/WT → WT vs. Alox5−/− → WT, Alox5−/−/C5ar −/− → WT, or C5ar−/− → WT; P < 0.001 in AT for WT → WT or Alox5−/−/WT → WT vs. Alox5−/− → WT, Alox5−/−/C5ar−/− → WT, or C5ar−/− → WT; and P < 0.01 in AT for C5ar−/−/WT → WT vs. Alox5−/− → WT, Alox5−/−/C5ar−/− → WT, or C5ar−/− → WT. (G) Histological score of mice from A and B (n = 9–15 mice per group; compiled from three independent experiments). ***P < 0.001 for indicated group vs. Alox5−/−/C5ar −/− → WT; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 for indicated group vs. Alox5−/− → WT; ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 for indicated group vs. C5ar−/− → WT. (H) Respective representative sections. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

To corroborate these findings and to exclude that tissue mast cells or macrophages are a source of LTB4 in this model, a variant of the experiment was conducted, generating Alox5−/−/C5ar−/− → Alox5−/− and Alox5−/−/WT → Alox5−/− mixed BMC with the BMs mixed in a ratio of 3:1 in favor of Alox5−/− cells and subjecting these mice to serum transfer. WT → Alox5−/−, Alox5−/− → Alox5−/−, and C5ar−/− → Alox5−/− BMC served as controls. WT → Alox5−/− BMC developed severe arthritis, confirming that 5-LO expression in radiosensitive cells is sufficient for arthritis. C5ar−/− → Alox5−/− and Alox5−/− → Alox5−/− BMC did not develop arthritis. In contrast, Alox5−/−/WT → Alox5−/− BMC developed arthritis, albeit less severe than that in WT → Alox5−/− BMC (Fig. S3 A and B). Thus, 25% WT BM still produced enough LTB4 to initiate and sustain arthritis. However, Alox5−/−/C5ar−/− → Alox5−/− BMC did not exhibit signs of arthritis, demonstrating that C5ar−/− BM cells did not synthesize sufficient amounts of LTB4 to induce arthritis, supporting our conclusion that C5a directly activates 5-LO.

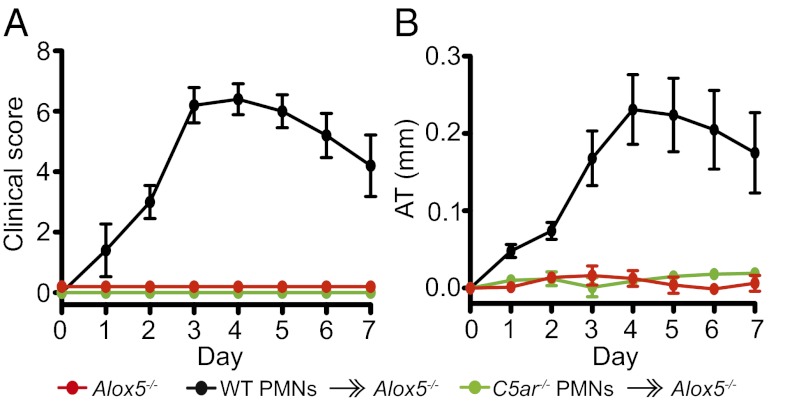

To prove that C5aR expression is specifically required on PMNs to induce LTB4, WT and C5ar−/− PMNs were adoptively transferred into Alox5−/− mice. It had previously been shown that adoptive transfer of WT PMNs into Alox5−/− mice transiently restores arthritis (5). We confirmed that adoptive transfer of WT PMNs transiently restores arthritis in Alox5−/− mice. However, adoptive transfer of C5ar−/− PMNs into Alox5−/− mice failed to do so (Fig. 4 A and B), indicating that C5aR on PMNs is required to induce LTB4 to initiate arthritis.

Fig. 4.

C5aR/5-LO coexpression in PMNs is required for arthritis. (A and B) A total of 20 × 106 WT or C5ar−/− PMNs were adoptively transferred into Alox5−/− mice (“WT PMNs  Alox5−/−” and “C5ar−/− PMNs

Alox5−/−” and “C5ar−/− PMNs  Alox5−/−”) together with K/BxN serum i.v. on days 0 and 2. Alox5−/− mice receiving only K/BxN serum served as controls. Mice were clinically scored daily (n = 4–5 mice per group; one representative of three independent experiments is shown). P < 0.001 for WT PMNs

Alox5−/−”) together with K/BxN serum i.v. on days 0 and 2. Alox5−/− mice receiving only K/BxN serum served as controls. Mice were clinically scored daily (n = 4–5 mice per group; one representative of three independent experiments is shown). P < 0.001 for WT PMNs  Alox5−/− vs. C5ar−/− PMNs

Alox5−/− vs. C5ar−/− PMNs  Alox5−/− or Alox5−/− controls in clinical score and ankle thickening. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Alox5−/− or Alox5−/− controls in clinical score and ankle thickening. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

FcRγ and IL-1α/β Must Be Coexpressed in PMNs.

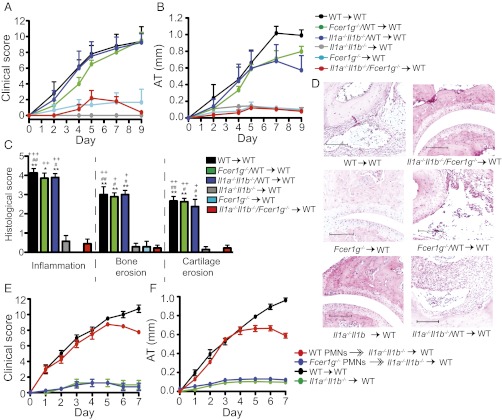

We generated Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/WT → WT, Fcer1g−/−/WT → WT, and Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcer1g −/− → WT mixed BMC with donor BMs used in a 1:1 ratio, as well as Fcer1g −/− → WT and Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT BMC and WT → WT control BMC. Fcer1g−/− → WT BMC were resistant to arthritis, confirming that FcRγ expression on radiosensitive cells is required for arthritis. Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT and Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT BMC displayed only minor signs of arthritis, whereas WT → WT controls, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/WT → WT, and Fcer1g−/−/WT → WT BMC developed severe arthritis (Fig. 5 A and B). Consistently, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/WT → WT and Fcer1g−/−/WT → WT BMC showed histological signs of arthritis indistinguishable from WT → WT controls, whereas Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT, and Fcer1g−/− → WT BMC hardly showed signs of arthritis (Fig. 5 C and D). The requirement for FcRγ and IL-1α/β to be coexpressed suggests that ICs directly induce IL-1β release.

Fig. 5.

IL-1β/FcRγ coexpression in PMNs is required for arthritis. (A and B) Arthritis in WT → WT, Fcer1g−/− → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/WT → WT, and Fcer1g−/−/WT → WT BMC (n = 4–5 mice per group). P < 0.0001, WT → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/WT → WT, and Fcer1g−/−/WT → WT vs. Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT, and Fcer1g−/− → WT. (C) Histological score of ankles from mice in A and B (n = 7–9 mice per group; data compiled from two independent experiments). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for indicated group vs. Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcer1g−/− → WT; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 for indicated group vs. Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT; +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01, +++P < 0.001 for indicated group vs. Fcer1g−/− → WT. (D) Respective representative sections. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (E and F) Clinical evaluation. A total of 20 × 106 WT or Fcer1g−/− PMNs were adoptively transferred i.v. into Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT chimeras (WT PMNs  Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT; Fcer1g−/− PMNs

Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT; Fcer1g−/− PMNs  Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT) with K/BxN serum on days 0 and 2. WT → WT and Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT chimera obtaining only K/BxN serum served as controls (n = 4 mice per group; one representative of three independent experiments is shown). P < 0.001 for WT PMNs

Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT) with K/BxN serum on days 0 and 2. WT → WT and Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT chimera obtaining only K/BxN serum served as controls (n = 4 mice per group; one representative of three independent experiments is shown). P < 0.001 for WT PMNs  Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT vs. Fcer1g−/− PMNs

Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT vs. Fcer1g−/− PMNs  Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT or vs. Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT chimera in clinical score and AT. All data presented are mean ± SEM.

Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT or vs. Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT chimera in clinical score and AT. All data presented are mean ± SEM.

To show that ICs induce IL-1β in PMNs, we generated Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT chimera and adoptively transferred WT and Fcer1g−/− PMNs into these BMC mice. Whereas Fcer1g−/− PMNs had no effect on arthritis in Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT BMC mice, adoptive transfer of WT PMNs significantly reinforced arthritis (Fig. 5 E and F), suggesting a requirement for FcγR activation on PMNs for IL-1β induction.

FcγRIII Is Required for IL-1β Release from PMN in Arthritis.

As K/BxN serum predominantly contains anti-GPI IgG1 antibodies (10, 31), and IgG1-ICs bind with highest avidity to FcγRIII, which is highly expressed on PMNs (21), we examined whether FcγRIII is required for the induction of IL-1β. Although it is known that FcγRIII contributes to autoantibody-induced arthritis (9), the relative contribution of FcγRIII on radioresistant vs. radiosensitive cells has not been addressed. We therefore generated all “criss-cross” BMC combinations of Fcgr3−/− and WT mice. Fcgr3−/− → Fcgr3−/− controls and Fcgr3−/− → WT BMC did not develop arthritis. In contrast, WT → Fcgr3−/− BMC developed marked arthritis, albeit attenuated compared with that in WT → WT controls (Fig. S4 A–D). Thus, expression of FcγRIII on radiosensitive cells is a prerequisite for arthritis, whereas expression on radioresistant cells is dispensable but appears to augment arthritis.

To determine whether FcγRIII on mast cells plays a role in arthritis in this model, we generated Kitw/Kitw-v → Fcgr3−/− BMC and subjected them to K/BxN serum transfer. Arthritis in Kitw/Kitw-v → Fcgr3−/− BMC was indistinguishable from that in WT → Fcgr3−/− BMC, suggesting that FcγRIII on mast cells does not play an important role in the development of arthritis in this model (Fig. S4 E and F). These clinical findings were confirmed by the histopathological analysis of ankle joints (Fig. S4 G and H).

We also addressed whether FcγRIII is critical for the induction of IL-1β by generating Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcgr3 −/− → WT mixed BMC with donor BMs used in a 1:1 ratio and their respective controls. Whereas Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/WT → WT and Fcgr3 −/−/WT → WT BMC were susceptible to arthritis, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcgr3 −/− → WT BMC exhibited only minor signs of arthritis (Fig. 6 A and B), indicating that FcγRIII is responsible for the induction of IL-1β in PMNs. Additionally, IL-1β injected daily on days 0–2 restored clinical and histopathological arthritis in Fcgr3 −/− → WT BMC, suggesting that IL-1β is the only essential effector downstream of FcγRIII (Fig. 6 C and D and Fig. S5 A and B).

Fig. 6.

FcγRIII is required for IL-1β release. (A and B) Arthritis in WT → WT, Fcgr3−/− → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcgr3−/− → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/WT → WT, and Fcgr3−/−/WT → WT BMC (n = 3–5 mice per group). WT → WT, Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/WT → WT, or Fcgr3−/−/WT vs. Il1a−/−Il1b−/−/Fcgr3−/− → WT, Fcgr3−/− → WT, or Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT, P < 0.001 in clinical score and AT. One representative of two independent experiments is shown. (C and D) Arthritis in WT → WT, Fcgr3−/− → WT, and Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT chimera after i.p. injection of K/BxN serum. Fcgr3−/− → WT and Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT chimera were additionally injected i.p. with either 2.5 μg mrIL-1β or its carrier protein (CP) alone, as a control, daily on days 0–2 (n = 3 mice per group). Clinical score and ankle thickening were determined every other day. ***P < 0.001 for Fcgr3−/− → WT + mrIL-1 vs. Fcgr3−/− → WT + CP and Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT + mrIL-1 vs. Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT + CP in clinical score and AT. All data presented are mean ± SEM.

LTB4 and IL-1β Release from C5a- and Immune Complex-Stimulated Human Neutrophils.

To extend our findings to humans, we determined whether C5a and ICs could induce the release of LTB4 and IL-1β, respectively, from human PMNs. Similar to what we found for murine PMNs, human recombinant C5a in a dose-dependent manner induced the release of LTB4 from freshly isolated human peripheral blood PMNs (Fig. S6A). Likewise, we also found that immobilized ICs induced the release of IL-1β from human GM-CSF prestimulated peripheral blood neutrophils (Fig. S6B).

Discussion

We have defined specific roles for C5aR and FcγR signaling in PMNs required for the initiation and progression of autoantibody-induced arthritis. We demonstrate that C5aR and FcγR activation upon PMNs specifically induces the release of two key mediators, LTB4 and IL-1β, respectively. Thus, we have uncovered a previously unknown direct connection between essential mediators in this model linking C5aR activation to LTB4 release and FcγR engagement to IL-1β release, elucidating the previously enigmatic necessity for both C5aR and FcγR in autoantibody-induced arthritis.

These findings are noteworthy in two additional aspects. First, they suggest that C5aR and FcγR activation on PMNs is required to orchestrate PMN recruitment and subsequent inflammation. In other models of autoantibody-induced inflammation, activation of FcγRs and C5aR on tissue resident immune cells, such as macrophages, was required for the recruitment of PMNs into peripheral tissue sites (18). Second, C5aR-induced LTB4 release and FcγR-induced IL-1β release in vivo occur independently from each other without cross-regulation between the two receptor classes. The relationship between C5aR and FcγRs on PMNs in autoantibody-induced arthritis, therefore, significantly differs from the cross-regulation found in other models of autoantibody-induced inflammation, where C5aR signaling is thought to primarily set the threshold for subsequent sustained activation of FcγRs on tissue resident immune cells (16, 18). This paradigm is apparently not operational in our model of autoantibody-induced PMN-driven arthritis.

Detailed investigation into mechanisms of effector cell recruitment in several mouse models of sterile inflammation in recent years supports the notion of sequential cascades of chemoattractants collaborating in a nonredundant manner to initiate inflammation (1–3, 6, 7). The choreography of PMN recruitment by nonredundant chemoattractant cascades, however, demands highly organized temporal and spatial patterns of chemoattractant expression (3, 6, 7). This mechanism may be particularly relevant when a single cell type is the major source for several chemoattractants required in a cascade, as this is the case for the PMN in autoantibody-induced arthritis. Our results suggest that the highly organized pattern of chemoattractant expression that is operational in vivo is achieved by the specificity of the stimuli inducing these chemoattractants.

To determine whether C5aR and FcγRs directly induce LTB4 and IL-1β from PMNs in vivo we generated mixed BMC mice. These mice allowed us to directly examine a stimulus–response relationship occurring in the same cell type, while evaluating its relevance in a complex biological system in vivo. We used a protocol for the generation of chimeric mice that was optimized to leave tissue mast cells and tissue macrophages of recipient origin during the duration of the experiment. This protocol exploited the fact that 4 wk after sublethal irradiation and BM reconstitution, peripheral PMN counts have fully recovered and are of donor origin (32), whereas tissue mast cells and macrophages are radioresistant and are of recipient origin during the duration of the experiment (13, 33–35). For this reason, protocols designed to examine the effect of donor mast cells in reconstituted mice wait at least 10 wk after donor mast transfer before using these reconstituted mice for experiments (28). In our studies, we used BMC mice 4 wk after BM reconstitution, when tissue mast cells and macrophages were still of recipient origin (Fig. S7). Mast cells were suggested to play an essential role in the K/BxN model of autoantibody-induced arthritis, and C5aR and FcγRIII on mast cells as well as mast cell-derived IL-1β were considered to significantly contribute to arthritis (28, 36–38). However, we found that C5aR and FcγRIII on radiosensitive cells alone are completely sufficient for arthritis and that Kitw/Kitw-v → C5ar−/− and Kitw/Kitw-v → Fcgr3−/− chimeric mice were also fully susceptible to arthritis, demonstrating that C5aR and FcγRIII on mast cells do not contribute significantly to arthritis in the K/BxN model. Furthermore, while this article was in preparation, a new mast cell-deficient mouse strain was developed, applying Cre-mediated mast cell genotoxicity by use of the mast cell-specific carboxypeptidase A3 locus (22). These Cpa3Cre/+ mice are more specifically mast cell-deficient than the previously used Kit mutant mouse strains. Consistent with our results, Cpa3Cre/+ mice are fully susceptible to autoantibody-induced arthritis in the K/BxN model (22).

The overall importance of PMNs in autoantibody-induced arthritis has recently been readdressed by Monach et al., using Growth factor independent 1 (Gfi-1)-deficient mice (13). Gfi-1 is a zinc-finger transcriptional repressor required for maturation of granulocyte and lymphocyte lineages (39–42). Gfi1−/− mice exhibit several hematological abnormalities, among others, dysfunctional terminal PMN differentiation (39, 42). Monach et al. (13) confirmed the requirement for PMNs in autoantibody-induced arthritis. They demonstrated that Gfi1−/− mice were protected from arthritis in the K/BxN model and that arthritis susceptibility was restored in WT → Gfi1−/− chimeric mice. Furthermore, they also examined arthritis in bone marrow chimeric mice using Gfi1−/− mice as recipients and C5ar−/−, Fcer1g−/−, Fcgr3−/−, Alox5−/−, or Il1a−/−Il1b−/− mice as bone marrow donors. Consistent with our results, they found C5aR and FcRγ on PMNs were required for arthritis. However, in contrast to our findings, in Gfi1−/− mice, they found that PMN-derived IL-1β and 5-LO contributed to the severity of arthritis, but neither was required. We believe that this discrepancy with our data may be due to the hyperexcitable immune system of Gfi1−/− mice. Despite being deficient in mature PMNs, Gfi1−/− mice also exhibit enhanced inflammation (39, 42). Gfi1−/− mice die after minor doses of LPS from a cytokine storm with highly elevated levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, likely due to Gfi1−/− macrophages, which secrete much higher amounts of IL-1β and TNF-α after stimulation with LPS than WT macrophages (42). Of note, Monach et al. (13) found WT → Gfi1−/− chimeric mice developed overexuberant arthritis, in which macrophages were still of Gfi−/− origin. Therefore, it is certainly conceivable that hyperactive macrophages of Gfi−/− origin in these chimeras released enough IL-1β and LTB4 upon K/BxN serum transfer to compensate for the lack of PMN-derived LTB4 and IL-1β. Further, in contrast to our results, Monach et al. (13) concluded that FcγRIII was not required on PMNs for arthritis in the model. However, because we found that FcγRIII is required on PMNs specifically to induce IL-1β release, and Monach et al. found that IL-1β release from PMNs was contributory but not required in Gfi1−/− mice, it is not surprising that they found arthritis in WT → Gfi−/− chimeras was not dependent on FcγRIII.

C5aR is widely expressed on hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells, and its expression is up-regulated on many cell types under inflammatory conditions (43). Diverse cell types resident in the joint express C5aR, including endothelial cells, synovial cells, and mast cells. In patients with RA, C5aR expression is enhanced on resident synovial cells (44), and C5aR+ subtypes of mast cells are enriched in the synovium of these patients (45). Additionally, C5aR expression has also been described in osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and chondroblasts and may play a significant role in bone remodeling and inflammation (30, 46). Our data, however, demonstrate that C5aR expression on radiosensitive cells alone is necessary and sufficient in autoantibody-induced arthritis, whereas C5aR on radioresistant cells is not required. We were not able to restore arthritis in C5ar−/− mice by adoptive transfer of WT PMNs or WT BM, which might suggest that a radiosensitive cell not in the BM is required for arthritis; however, WT BM did restore disease susceptibility when transplanted into irradiated C5ar−/− recipient mice. We have previously found that after adoptive transfer of PMNs, less than 2% of the circulating peripheral blood PMNs and a minority of the joint fluid PMNs are of donor origin (4). Therefore, we interpret the apparent discrepancy between the WT → C5ar−/− adoptive transfer and bone marrow transplantation experiments as due to C5aR being required on the majority of PMNs entering the joint, calling for the presence of greater numbers of circulating C5aR+ PMNs than is achievable with adoptive transfer alone. As additional evidence for the requirement of C5aR on PMNs, we found that adoptive transfer of wild-type PMNs restored arthritis in Alox5−/− mice, whereas C5ar−/− PMNs did not. This result suggests that C5aR on PMNs does play an essential role for the generation of arthritis; otherwise C5ar−/− PMNs would have restored arthritis in Alox5−/− mice.

In vitro, both C5a and ICs induced LTB4 and cooperated in an additive manner, but in vivo, FcγR-induced LTB4 release was not required for arthritis. The reason for this is not known; however, in vitro C5a appeared more efficacious in inducing LTB4 than ICs. Therefore, in vivo, IC-induced LTB4 release may be too weak to induce arthritis in the absence of C5aR, whereas C5a-induced LTB4 release appears vigorous enough alone to induce arthritis. It is also conceivable that C5a, as a diffusible mediator, may be more efficient in encountering PMNs entering the joint compared with ICs, which might be restricted to the joint cartilage surface. Notably, both LTB4 and C5a are continuously required for arthritis in this model (4, 5, 9), supporting the notion that C5a is the critical inducer of LTB4 in vivo.

In models of C5a-induced peritonitis and antibody-mediated tumor immunotherapy, PMN recruitment is reduced in BLT1-deficient (Ltb4r1−/−) mice (47). Further, in a model of C5a-induced dermatitis, PMN recruitment is also reduced when 5-LO activity is inhibited (48). These studies suggest that LTB4 and its receptor BLT1 are required for PMN recruitment following the local generation of C5a. Although these studies did not address the cellular source and mode of LTB4 induction, they are consistent with our findings and support the idea that the “C5a−LTB4 axis” “kickstarts” PMN recruitment. The C5a−LTB4 axis is particularly suitable for this role as C5a is generated immediately upon diverse pathological stimuli, and, due to its ultrarapid production and high potency, LTB4 is poised to initiate PMN recruitment cascades (1, 2).

FcγR signaling is also required for the induction of autoantibody-induced arthritis (9, 49, 50). We found here that FcγRIII on both radiosensitive and radioresistant cells contributed to arthritis, but only its expression on radiosensitive cells was necessary and sufficient. Most importantly, we have shown here that FcγRIII and IL-1β must be coexpressed in the same radiosensitive cell and that PMNs must be activated via FcγRs to restore arthritis in Il1a−/−Il1b−/− → WT BMC. This provides evidence that in vivo IL-1β from PMNs is required for arthritis and that it is directly induced via FcγRIII in PMNs. This is consistent with our prior observation that PMNs are required to express IL-1β to restore arthritis in Ltbr4−/− mice (3). In our previous study, we also showed that IL-1β amplifies arthritis by inducing the release of PMN-active CCR1 and CXCR2 chemokine ligands, especially from fibroblast-like synovial cells and endothelial cells (3). The specific roles of C5aR and FcγRIII elucidated here, in concert with our prior observations, suggest that C5aR-induced LTB4 production is upstream of FcγRIII-induced IL-1β release from PMNs.

Our findings have correlations to inflammatory arthritis in humans, as C5a, LTB4, ICs, IL-1β, and their respective receptors are abundant in arthritic joints (26, 44, 51–55), and PMNs constitute the bulk of cells in the synovial fluid (56). C5a and LTB4 are elevated in the synovial fluid of patients with RA, and the activation level of the alternative complement pathway in the synovial fluid of patients with RA correlates with levels of LTB4 (57). The concentration of C5a in RA synovial fluid averages ∼20 ng/mL (26, 27), a concentration that we found induces the release of LTB4 from mouse and human PMNs, suggesting that this pathway is relevant under physiological conditions. Intriguingly, expression of IL-1β is a characteristic feature of PMNs infiltrating the synovial fluid (58, 59), and because synovial fluid of patients with RA induces the release of IL-1β from PMNs, it was suggested that ICs in the synovial fluid are responsible for this activity (60). Our data confirm that ICs induce the release of IL-1β from GM-CSF prestimulated human PMNs in vitro, which supports the hypothesis that in the proinflammatory milieu of arthritic joints, ICs may induce the release of IL-1β from PMNs. Although PMNs do not express high levels of IL-1β on an individual level, the vast number of PMNs in the joint certainly makes them a potential major source of IL-1β. Although IL-1β inhibition is less efficacious than TNF inhibition for the treatment of RA, it still improves clinical symptoms in RA and other arthritides (61). Therefore, the detailed study of specific leukocyte activation pathways made possible using in vivo animal models provides unique mechanistic insights into the intricate pathophysiology of immune complex-mediated diseases in humans, which may then inform future approaches to develop new therapeutic strategies.

Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6 WT mice, congenic for CD45.1, Kitw/Kitw-v, Tnfrdf11b−/−, Alox5−/−, Fcgr3−/−, and Tlr4−/− mice, all on the C57BL/6 background, were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (JAX). Fcer1g−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background were purchased from Taconic Farms. Il1a−/−Il1b−/− and C5ar−/− mice on the C57BL/6 background were kindly provided by Y. Iwakura (University of Tokyo) (62) and C. Gerard (Children’s Hospital, Boston) (63), respectively. All strains were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Massachusetts General Hospital. KRN mice were kindly provided by D. Mathis and C. Benoist (Harvard Medical School, Boston) and housed at JAX. K/BxN mice were obtained by crossing KRN with NOD/LtJ mice. All experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care. Age- and sex-matched, 6- to 12-wk-old mice were used in all experiments.

Generation of Bone Marrow Chimera.

BMC were generated by sublethal irradiation of the recipient mice (10 Gy, 10 min) and subsequent BM reconstitution with 107 freshly isolated bone marrow cells within 24 h. Mixed BMC were generated by reconstituting the recipient’s BM with BM from two different donor strains in a 1:1 or 3:1 ratio, as indicated in the text. For a 1:1 ratio, each donor contributed 5 × 106 BM cells for the reconstitution, and for a 3:1 ratio one donor contributed 7.5 × 106 and the other donor 2.5 × 106 BM cells (Fig. S8). Four weeks after reconstitution chimeric mice were used for experiments. The recovery of PMN blood counts at 4 wk after irradiation was confirmed by WBC differential count. FACS analysis of CD45.1 and CD45.2 expression on BM-derived blood cells was used to control for chimerism, exploiting the congenic expression of the CD45.1 allele in WT mice vs. CD45.2 expression in all other strains used in this study. Staining reagents used were anti-CD45.1 PE, CD45.2 FITC, and anti-Ly6G PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD Bioscience). At the time of the experiments, ≥95% of PMNs were of donor origin (Fig. S7). To address the origin of tissue macrophages, macrophages were isolated from chimeric mice by peritoneal lavage and stained with anti-CD45.1, anti-CD45.2, and anti-F4/80 PerCP-Cy5.5 (BD Bioscience). At the time of the experiments, more than 95% of peritoneal macrophages were of recipient origin (Fig. S7).

Serum Transfer and Arthritis Scoring.

K/BxN serum was harvested from 8-wk-old arthritic K/BxN mice and stored at −80 °C. For induction of arthritis 150 μL of serum was injected i.p. or, if adoptive transfers of PMNs were conducted, i.v., into recipient mice on days 0 and 2 of the experiment. The clinical score was determined, as follows: 0, no arthritis; 1, localized edema/erythema on one paw surface; 2, edema/erythema on the entirety of one paw surface; and 3, edema/erythema on both paw surfaces. Scores were added for all four paws to a composite score of maximal 12. Ankle thickness was determined with a pocket thickness gauge (Mitutoyo). Ankle thickening (ankle thickness compared with baseline on day 0) was calculated as the mean difference between the current ankle thickness and the ankle thickness on day 0. For histopathological analysis, ankles were dissected and fixed in 4% (vol/vol) neutral buffered paraformaldehyde, demineralized in modified Kristensen’s solution, and H&E stained. The degree of inflammation, bone erosions, and cartilage erosions were scored, as described before (64). Briefly, they were scored as follows: 0, normal; 1, minimal; 2, mild; 3, moderate; 4, marked; and 5, severe.

IL-1β Administration.

Mice received 250 μL of 10 μg/mL murine recombinant IL-1β (mrIL-1) (R&D Systems) in sterile PBS containing 0.1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich), which served as carrier protein (CP) (50 μg CP per 1 μg IL-1). Control mice received 250 μL of 0.1% BSA in sterile PBS (= 125 μg CP). mrIL-1β and CP were given i.p. on days 0, 1, and 2, if applicable, 4 h after K/BxN serum.

BM PMN Adoptive Transfer.

Isolation and adoptive transfer studies of BM PMNs were performed according to established protocols (3). PMNs were greater than 90% pure and 95% viable as determined by Wright–Giemsa staining and trypan blue exclusion, respectively. A total of 20 × 106 PMNs in HBSS were injected i.v. via tail vein on days 0 and 2 before i.v. injection of 150 μL K/BxN serum.

Immunomagnetic Isolation and in Vitro Stimulation of PMNs.

BM PMNs for in vitro experiments were isolated using immunomagnetic separation. Freshly harvested mouse BM leukocytes were stained with PE-conjugated anti-Ly6G (BD Biosciences) and isolated with an EasySep PE selection kit (Stem Cell Technologies). Purity was greater than 95%. PMNs were resuspended in complete DMEM in a concentration of 5 × 106 BM PMNs/mL. For in vitro experiments, 5 × 105 BM PMNs per well were seeded into 96-well plates (Corning) and stimulated with ICs and recombinant murine C5a, CXCL2, CCL3, IL-1β, GM-CSF, and IFN-γ (R&D Systems), as indicated. ICs were prepared as described previously (3). PMNs were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for the time indicated. After harvest cell-free supernatants were stored at −80 °C. The concentration of LTB4 and IL-1β in the supernatant was determined by the LTB4 Parameter Assay Kit (R&D Systems) and by the Mouse IL-1β ELISA Ready-SET-Go Kit (eBioscience), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In Vitro Stimulation of Human PMNs.

The study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board and each subject provided written consent. Human PMNs were freshly isolated using Dextran and Ficoll from heparinized peripheral blood of healthy donors. After purification, neutrophils were counted and resuspended to a cell concentration of 5 × 106/mL in RPMI, 1% human serum, 10 mM Hepes. For stimulation with recombinant human C5a (R&D Systems), 1 mL of PMNs was seeded into round-bottom polypropylene tubes and stimulated for 1 h with C5a. Afterward, cell-free supernatants were harvested and the LTB4 contents assayed by ELISA (R&D Systems). For stimulation with immune complexes, PMNs were prestimulated with 50 ng/mL GM-CSF (Peprotech) for 30 min. Afterward, PMNs were seeded into 96-well plates coated with immune complexes, as described above, and stimulated for 20 h. Cell-free supernatants were assayed for IL-1β by ELISA (R&D Systems).

Statistical Analysis.

All data are presented as mean ± SEM or mean ± SD. Statistical differences in the clinical score (CS) and the ankle thickening (AT) were determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests. Differences in histological scores were determined by a Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn posttests. ELISA data were evaluated by a two-tailed Student’s t test or by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest, if more than two groups were compared. For all statistical analyses GraphPad Prism 5.0 was used, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) Grant Sa1960/1-1 (to C.D.S.), the Arthritis Foundation (C.D.S.), and National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI050892 (to A.D.L.) and K08 AR054094 (to N.D.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

See Author Summary on page 18647 (volume 109, number 46).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1213797109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sadik CD, Kim ND, Luster AD. Neutrophils cascading their way to inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(10):452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadik CD, Luster AD. Lipid-cytokine-chemokine cascades orchestrate leukocyte recruitment in inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91(2):207–215. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0811402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou RC, et al. Lipid-cytokine-chemokine cascade drives neutrophil recruitment in a murine model of inflammatory arthritis. Immunity. 2010;33(2):266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim ND, Chou RC, Seung E, Tager AM, Luster AD. A unique requirement for the leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 for neutrophil recruitment in inflammatory arthritis. J Exp Med. 2006;203(4):829–835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen M, et al. Neutrophil-derived leukotriene B4 is required for inflammatory arthritis. J Exp Med. 2006;203(4):837–842. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald B, Kubes P. Chemokines: Sirens of neutrophil recruitment-but is it just one song? Immunity. 2010;33(2):148–149. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald B, et al. Intravascular danger signals guide neutrophils to sites of sterile inflammation. Science. 2010;330(6002):362–366. doi: 10.1126/science.1195491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald B, Kubes P. Cellular and molecular choreography of neutrophil recruitment to sites of sterile inflammation. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89(11):1079–1088. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji H, et al. Arthritis critically dependent on innate immune system players. Immunity. 2002;16(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kouskoff V, et al. Organ-specific disease provoked by systemic autoimmunity. Cell. 1996;87(5):811–822. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto I, Staub A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Arthritis provoked by linked T and B cell recognition of a glycolytic enzyme. Science. 1999;286(5445):1732–1735. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wipke BT, Allen PM. Essential role of neutrophils in the initiation and progression of a murine model of rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2001;167(3):1601–1608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monach PA, et al. Neutrophils in a mouse model of autoantibody-mediated arthritis: Critical producers of Fc receptor gamma, the receptor for C5a, and lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):753–764. doi: 10.1002/art.27238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott ER, et al. Deletion of Syk in neutrophils prevents immune complex arthritis. J Immunol. 2011;187(8):4319–4330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt RE, Gessner JE. Fc receptors and their interaction with complement in autoimmunity. Immunol Lett. 2005;100(1):56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klos A, et al. The role of the anaphylatoxins in health and disease. Mol Immunol. 2009;46(14):2753–2766. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayadas TN, Tsokos GC, Tsuboi N. Mechanisms of immune complex-mediated neutrophil recruitment and tissue injury. Circulation. 2009;120(20):2012–2024. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.771170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shushakova N, et al. C5a anaphylatoxin is a major regulator of activating versus inhibitory FcgammaRs in immune complex-induced lung disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(12):1823–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI200216577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar V, et al. Cell-derived anaphylatoxins as key mediators of antibody-dependent type II autoimmunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):512–520. doi: 10.1172/JCI25536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravetch JV. A full complement of receptors in immune complex diseases. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(12):1759–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI200217349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(1):34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feyerabend TB, et al. Cre-mediated cell ablation contests mast cell contribution in models of antibody- and T cell-mediated autoimmunity. Immunity. 2011;35(5):832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruhns P, Samuelsson A, Pollard JW, Ravetch JV. Colony-stimulating factor-1-dependent macrophages are responsible for IVIG protection in antibody-induced autoimmune disease. Immunity. 2003;18(4):573–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon S, Rajasekaran N, Jeisy-Walder E, Snapper SB, Illges H. A crucial role for macrophages in the pathology of K/B x N serum-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(10):3064–3073. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu HJ, et al. Inflammatory arthritis can be reined in by CpG-induced DC-NK cell cross talk. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1911–1922. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jose PJ, Moss IK, Maini RN, Williams TJ. Measurement of the chemotactic complement fragment C5a in rheumatoid synovial fluids by radioimmunoassay: Role of C5a in the acute inflammatory phase. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49(10):747–752. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.10.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song JJ, et al. Consortium for the Longitudinal Evaluation of African Americans with Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CLEAR) Registry Plasma carboxypeptidase B downregulates inflammatory responses in autoimmune arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(9):3517–3527. doi: 10.1172/JCI46387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee DM, et al. Mast cells: A cellular link between autoantibodies and inflammatory arthritis. Science. 2002;297(5587):1689–1692. doi: 10.1126/science.1073176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buttgereit F, et al. Transgenic disruption of glucocorticoid signaling in mature osteoblasts and osteocytes attenuates K/BxN mouse serum-induced arthritis in vivo. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(7):1998–2007. doi: 10.1002/art.24619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ignatius A, et al. Complement C3a and C5a modulate osteoclast formation and inflammatory response of osteoblasts in synergism with IL-1β. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112(9):2594–2605. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maccioni M, et al. Arthritogenic monoclonal antibodies from K/BxN mice. J Exp Med. 2002;195(8):1071–1077. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frasca D, et al. Hematopoietic reconstitution after lethal irradiation and bone marrow transplantation: Effects of different hematopoietic cytokines on the recovery of thymus, spleen and blood cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25(4):427–433. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitamura Y, Go S, Hatanaka K. Decrease of mast cells in W/Wv mice and their increase by bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1978;52(2):447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura Y, Shimada M, Hatanaka K, Miyano Y. Development of mast cells from grafted bone marrow cells in irradiated mice. Nature. 1977;268(5619):442–443. doi: 10.1038/268442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maus UA, et al. Resident alveolar macrophages are replaced by recruited monocytes in response to endotoxin-induced lung inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35(2):227–235. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0241OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nigrovic PA, et al. Mast cells contribute to initiation of autoantibody-mediated arthritis via IL-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(7):2325–2330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610852103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nigrovic PA, et al. C5a receptor enables participation of mast cells in immune complex arthritis independently of Fcγ receptor modulation. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(11):3322–3333. doi: 10.1002/art.27659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guma M, et al. JNK1 controls mast cell degranulation and IL-1beta production in inflammatory arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(51):22122–22127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016401107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hock H, et al. Intrinsic requirement for zinc finger transcription factor Gfi-1 in neutrophil differentiation. Immunity. 2003;18(1):109–120. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hock H, et al. Gfi-1 restricts proliferation and preserves functional integrity of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431(7011):1002–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature02994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu J, et al. Down-regulation of Gfi-1 expression by TGF-beta is important for differentiation of Th17 and CD103+ inducible regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206(2):329–341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karsunky H, et al. Inflammatory reactions and severe neutropenia in mice lacking the transcriptional repressor Gfi1. Nat Genet. 2002;30(3):295–300. doi: 10.1038/ng831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riedemann NC, et al. Increased C5a receptor expression in sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(1):101–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI15409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neumann E, et al. Local production of complement proteins in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(4):934–945. doi: 10.1002/art.10183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiener HP, et al. Expression of the C5a receptor (CD88) on synovial mast cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(2):233–245. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199802)41:2<233::AID-ART7>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ignatius A, et al. The anaphylatoxin receptor C5aR is present during fracture healing in rats and mediates osteoblast migration in vitro. J Trauma. 2011;71(4):952–960. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f8aa2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allendorf DJ, et al. C5a-mediated leukotriene B4-amplified neutrophil chemotaxis is essential in tumor immunotherapy facilitated by anti-tumor monoclonal antibody and beta-glucan. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):7050–7056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marleau S, Fruteau de Laclos B, Sanchez AB, Poubelle PE, Borgeat P. Role of 5-lipoxygenase products in the local accumulation of neutrophils in dermal inflammation in the rabbit. J Immunol. 1999;163(6):3449–3458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binstadt BA, et al. Particularities of the vasculature can promote the organ specificity of autoimmune attack. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(3):284–292. doi: 10.1038/ni1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corr M, Crain B. The role of FcgammaR signaling in the K/B x N serum transfer model of arthritis. J Immunol. 2002;169(11):6604–6609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Firestein GS, Alvaro-Gracia JM, Maki R. Quantitative analysis of cytokine gene expression in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 1990;144(9):3347–3353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davidson EM, Rae SA, Smith MJ. Leukotriene B4, a mediator of inflammation present in synovial fluid in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1983;42(6):677–679. doi: 10.1136/ard.42.6.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Høgåsen K, et al. Terminal complement pathway activation and low lysis inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fluid. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(1):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hashimoto A, et al. Differential expression of leukotriene B4 receptor subtypes (BLT1 and BLT2) in human synovial tissues and synovial fluid leukocytes of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(8):1712–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grant EP, et al. Essential role for the C5a receptor in regulating the effector phase of synovial infiltration and joint destruction in experimental arthritis. J Exp Med. 2002;196(11):1461–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edwards SW, Hallett MB. Seeing the wood for the trees: The forgotten role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Today. 1997;18(7):320–324. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ahmadzadeh N, Shingu M, Nobunaga M, Tawara T. Relationship between leukotriene B4 and immunological parameters in rheumatoid synovial fluids. Inflammation. 1991;15(6):497–503. doi: 10.1007/BF00923346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Quayle JA, Adams S, Bucknall RC, Edwards SW. Cytokine expression by inflammatory neutrophils. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1994;8(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quayle JA, Adams S, Bucknall RC, Edwards SW. Interleukin-1 expression by neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(11):930–933. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.11.930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.White FS, Quayle JA, Edwards SW. Gene expression by inflammatory neutrophils: Stimulation of interleukin-1 beta production by rheumatoid synovial fluid. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24(3):493S. doi: 10.1042/bst024493s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dinarello CA. A clinical perspective of IL-1β as the gatekeeper of inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(5):1203–1217. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Horai R, et al. Production of mice deficient in genes for interleukin (IL)-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-1alpha/beta, and IL-1 receptor antagonist shows that IL-1beta is crucial in turpentine-induced fever development and glucocorticoid secretion. J Exp Med. 1998;187(9):1463–1475. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Höpken UE, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C. The C5a chemoattractant receptor mediates mucosal defence to infection. Nature. 1996;383(6595):86–89. doi: 10.1038/383086a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pettit AR, et al. TRANCE/RANKL knockout mice are protected from bone erosion in a serum transfer model of arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(5):1689–1699. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]