Abstract

The generation of CD4+ T cell memory cells is poorly understood. Recently, two different murine CD4+ TCR transgenic T cell lines, LLO118 and LLO56, both specific for the same epitope but differing in their expression level of the cell surface protein CD5, were generated. Interestingly, these cell lines showed different behavior upon primary and secondary exposure to Listeria monocytogenes. While LLO118 showed a stronger primary response and generated more robust CD8+ T cell help upon secondary exposure, LLO56 CD4+ T cells had a dramatically better recall response. Using different mathematical models, we analyzed the dynamics of the two CD4+ T cell lines in mice during infection with L. monocytogenes. Our models allowed the quantitative comparison of the two T cell lines and provided predictions for the conversion of naïve T cells into memory cells. LLO118 CD4+ T cells are estimated to have a higher proliferation rate than LLO56 upon primary exposure. This difference can be explained by the lower expression level of CD5 on LLO118 CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, LLO56 memory cells are predicted to have a three-fold longer half-life than LLO118 memory cells ( and ). Although both cell lines differ in their memory capabilities, our analysis indicates no difference in the rate at which memory cells are generated. Our results show that different CD5 expression levels influence the proliferation dynamics of activated naïve CD4+T cells while leaving the conversion rate of those cells into memory cells unaffected.

Introduction

One of the most important features of the adaptive immune system is its ability to remember previous infections. A population of memory T cells characterized by a long half-life is maintained after the clearance of an infection giving lifelong immunity to certain infectious agents. The pathways by which memory cells are generated are only incompletely understood (1, 2). Understanding the mechanisms underlying the generation of antigen specific memory T cells would allow us to improve the development of effective vaccines (3, 4).

CD4+ T helper cells play an important role in immunity providing immune responses against extracellular pathogens and influencing the generation and survival of memory CD8+ T cells (5–10). Once activated upon infection, CD4+ T cells fully differentiate into effector cells from which they can further differentiate into a memory phenotype (11, 12). In contrast to CD8+ T cells, where specific memory precursor cells could be determined based on cellular markers (T-bet, CD27, IL-7R) (13), there are as yet no defined precursor cells for memory CD4+ T cells. The markers used for CD8+ T cells seem not to work for CD4+ T cells. Recent experimental studies showed that there might be several pathways by which CD4+ T cells develop a memory phenotype (reviewed in 14, 15).

In this study we analyzed the dynamics of two different CD4+ TCR transgenic (Tg) T cell lines in mice, LLO118 and LLO56, during primary and secondary responses to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Both LLO118 and LLO56 are specific for the same epitope listeriolysin (190-205) but may have different affinities for the epitope when presented on MHC. The two types of Tg mice have significantly different in vivo responses. LLO56 CD4+ T cells have a superior CD4+ T cell recall response upon secondary infection, while LLO118 CD4+ T cells proliferate more strongly during primary infection and provide better help to CD8+ T cells in secondary infections (16). Experimental analysis revealed that both cell populations differed in their CD5 expression, with LLO118 expressing much lower levels of CD5 than LLO56 (16).

CD5 is a transmembrane protein expressed on the surface of T cells and a subset of B cells. This protein is associated with a negative regulation of TCR-signaling, inhibiting the activation and proliferation of T cells (17–19). As such it plays a role during thymocyte selection; cells with high affinity for self-antigen upregulate CD5 expression (20). CD5 expression on T cells is observed to be regulated by TCR avidity (20). High expression levels of CD5 on naïve T cells inhibit cell proliferation while T cells from CD5 deficient mice are hyperresponsive to stimulation through the TCR (17). In contrast, a recent study found that naïve CD8+CD5hi T cells were more responsive to IL-7 driven homeostatic proliferation in vitro (21).

Using previously published mathematical models and extensions thereof to study the proliferation dynamics of T lymphocytes (22–24), we examine the dynamics of LLO118 and LLO56 CD4+ T cells during L. monocytogenes infection of mice. Our analysis reveals that LLO118 CD4+ T cells have a higher proliferation rate than LLO56. This difference in the proliferation rates can be explained by the difference in CD5 expression levels between these cell lines. Although we did not find evidence for a difference in the memory generation rates between the two cell lines, our models predict that memory LLO56 CD4+ T cells have an approximately three times longer average half-life than LLO118 memory cells, with and . This leads to a better maintenance of the LLO56 cell population at later time points explaining the better response of this cell type upon secondary infection (16). These results quantitatively corroborate the hypothesis that TCR-signaling regulation by CD5 is responsible for the different proliferation dynamics that were observed for different subsets of CD4+ T cells upon primary infection (16). In addition, a cell line expressing higher levels of CD5 during primary infection is predicted to lead to a longer sustained memory response than one showing stronger proliferation dynamics during primary infection due to lower CD5 expression levels.

Materials and Methods

Data

The LLO118 and LLO56 TCR-transgenic lines, specific for listeriolysin (190-205) (LLO190-205/I-Ab), were made from T cell hybridomas generated from L. monocytogenes infected mice (16). LLO118 and LLO56 have identical α and β V region usage, which differed by only 15 amino acids. Single cell suspensions were made from spleens of LLO118 and LLO56 mice and CD4+ T cells were purified by negative selection. 3 × 103 LLO118-Ly5.1 and LLO56-Thy1.1 cells each were co-transferred into naïve C57BL/6 mice which were subsequently infected with 1 × 104 CFU L. monocytogenes strain 1043S. At day 0, 5, 8, 12, 15, 19, 26 and 35 after infection, mice were sacrificed and the number of T cells in the spleen and lymph nodes monitored by flow cytometry and analyzed for T cell surface markers.

Mathematical model

Our basic mathematical model to describe the dynamics of the different CD4+ T cell populations was developed by De Boer et al. (23). Activated CD4+ T cells, A, proliferate at a net-proliferation rate ρ, die with a basic turnover rate δA and develop into memory cells at a rate r. Memory cells, M, have an average lifetime of 1/δM, and usually δM ≪ δA. As the proliferation of T cells is described as being “programmed” after an antigenic stimulation (25–27), we assume that activated CD4+ T cells proliferate during an expansion phase that lasts until the peak of the response at time T. During this time, t < T, no memory cells are assumed to be present. Memory cells are assumed to be developed during the contraction phase of the T cell response after the peak. The basic model is formulated by

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

where I[t<T ] denotes the indicator function defined as

| (2) |

In this model T cells proliferate until time T, which determines the length of the expansion phase, and then stop proliferating and either die or develop into memory cells during the contraction phase. Cell death is ignored during the expansion phase or can be implicitly incorporated by viewing ρ as the net-expansion rate rather than the true proliferation rate.

Model extensions

Biphasic contraction phase

As an extension of the basic model, we assume a biphasic contraction phase as formulated in De Boer et al. (23). This extension was included as it was observed that the contraction phase of the CD4+ T cell response to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection could be divided into several phases with a progressive increase in the half-life of the cells (23, 28). Therefore, we assume that after the peak of the proliferation phase at time T, activated cells die by apoptosis with an additional fast contraction rate α for a time period of length Δ. In this case, Eq. (1a) changes to

| (3) |

Continuous development of memory

Recent studies have shown that memory CD4+ T cells develop out of multiple different precursor cells (reviewed in 14, 15). Memory CD4+ T cells can develop out of differentiated CD4+ effector T cells (11, 12). However, it is also suggested that asymmetric distribution of receptors and effector molecules during cell division can result in one daughter cell following the effector pathway while the other one develops into a memory cell (29). To include the latter observations into our model, we additionally allow the development of memory during the proliferation phase for t < T. In this scenario, the model defined by Eqs. (1a) and (1b) changes to

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

Alternative differentiation pathway

While the basic model given by Eqs. (1a) and (1b) mainly assumes that CD4+ T cells progress along the differentiation pathway naïve/activated → effector → memory, an alternative model proposed by Lanzavecchia and Sallusto (30) suggests that memory cells directly develop out of naïve lymphocytes and effector cell represent the final differentiation step. Based on this alternative differentiation pathway, Kohler (24) proposed a model that considered two types of cells, memory (M) and effector (E) cells. Analogously to the model given in Eqs. (1a) and (1b), the cell dynamics is divided into two phases. During the proliferation phase, memory and effector cells proliferate at a net-proliferation rate ρ, and memory cells differentiate into effector cells at a rate r. After the proliferation phase is terminated at time T, memory and effector cells die at rate δM and δE, respectively. The corresponding differential equations are given by Eqs. (5a) and (5b).

| (5a) |

| (5b) |

Equation (5b) can be extended by an additional faster contraction phase where effector cells experience an additional apoptotic death rate α analogous to Eq. (3).

Data fitting

All models were fitted to the experimental data using a maximum likelihood approach on the log-transformed cell count data. Parameters were constrained by requiring δM ≤ δA, and all parameters were required to be larger than 0. Fitting was performed in the R-language of statistical computing (31) using the optim-routine. To compare the fit of the different models to the data we report the residual mean square (MNSQ), which is the residual sum of squares divided by the residual degrees of freedom, i.e. the difference between the number of data points and the number of free parameters (32).

Results

CD4+ T cell dynamics

In the basic model, we assume that CD4+ T cells differentiate according to the pathway naïve/activated → effector → memory. Activated naïve CD4+ T cells proliferate for a certain time T until the peak of the immune response. The peak is followed by a contraction phase in which activated T cell experience apoptosis or develop into memory cells. For a detailed description of the model see Materials and Methods, Eqs. (1a) and (1b).

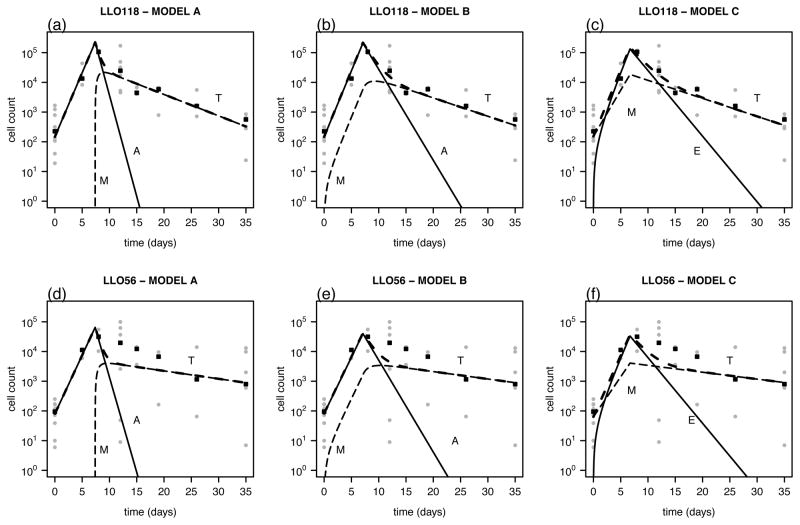

To limit the number of parameters that have to be estimated and because data on LLO118 and LLO56 cell numbers are obtained by co-transfer of these cell types into mice, we fitted both cell counts simultaneously. There is experimental evidence that competition between the two cell lines for the same MHC-antigen does not play a role in this experimental setting (16). Therefore, this factor is neglected in the formulation of the models. While both cell types are assumed to experience the same period of antigenic stimulation, T, we allow for differences in the proliferation rate, ρ, the memory formation rate, r, and the death rate of memory cells, δM between LLO118 and LLO56 CD4+ T cells. The best estimates for the parameters and the corresponding predicted CD4+ T cell dynamics and original data are shown in Table I and Figure 1, respectively. We estimate that the expansion phase lasts until T = 7.4 days after infection, corresponding to the observed peak in the data around day 8 after infection. LLO118 T cells have a slightly higher net-proliferation rate than LLO56 T cells (ρLLO118 = 0.99 day−1, ρLLO56 = 0.91 day−1) that is statistically significant (p < 0.05). Furthermore, the model estimates a higher conversion rate of effector cells into memory cells, r, for LLO118, as well as a significantly shorter half-life for the memory cells of this cell population ( , p < 0.05). The significant differences between the two CD4+ T cell lineages with regard to the proliferation rate and the death rate of memory cells stay valid if we either extend the model by assuming a constant development of memory cells even during the proliferation phase (Eqs. (4a) and (4b)) or a model that assumes that CD4+ T cells follow the alternative differentiation pathway naïve/activated → memory → effector (Eqs. (5a) and (5b)) (see Table I). However, the significant difference in the memory conversion rates, r, between the two cell lines is not found when using either of the two alternative models. All three models perform equally well in explaining the data based on the residual mean square (MNSQ≈ 3.4 for all three models, see Table I and Materials &Methods).

Table I.

Parameter estimates for CD4+ T cell dynamics.a

| parameter | symbol | unit | Model A | Model B | Model C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation rate | ρLLO118 | day−1 | 0.99 | [0.97,1.01] | 1.05 | [1.03,1.07] | 1.03 | [1.01,1.05] | |

| ρLLO56 | 0.91 | [0.88,0.93] | 0.91 | [0.88,0.93] | 0.95 | [0.93,0.97] | |||

| Memory cell formation | rLLO118 | day−1 | 0.20 | [0.15,0.24] | 0.03 | [0.02,0.03] | 0.31 | [0.28,0.34] | |

| rLLO56 | 0.11 | [0.08,0.12] | 0.04 | [0.03,0.04] | 0.33 | [0.31,0.35] | |||

| Activated cells at t = 0 | A(0)LLO118 | cells | 148 | [140,155] | 147 | [140,155] | 152 | [144,159] | |

| A(0)LLO56 | 80 | [74,86] | 82 | [76,88] | 63 | [59,67] | |||

| Death rate of memory cells |

|

day−1 | 0.16 | [0.16,0.17] | 0.14 | [0.13,0.15] | 0.14 | [0.13,0.15] | |

|

|

0.06 | [0.05,0.07] | 0.06 | [0.05,0.06] | 0.05 | [0.04,0.06] | |||

| Death rate of activated cells | δA | day−1 | 1.37 | [1.07,1.66] | 0.68 | [0.61,0.74] | 0.51 | [0.47,0.54] | |

| End of proliferation phase | T | day | 7.4 | [7.2,7.5] | 7.1 | [7,7.2] | 6.7 | [6.6,6.8] | |

| residual mean square | MNSQ | 3.381 | 3.393 | 3.393 | |||||

Parameter estimates for the basic model ((A), Eqs. (1a) and (1b)), for a model assuming constant memory cell production during the proliferation phase ((B), Eqs. (4a) and (4b)), and for a model assuming the alternative differentiation pathway ((C), Eqs. (5a) and (5b)). 95% confidence intervals for the estimates are calculated based on the standard error approximated by the Hessian-matrix. MNSQ indicates the residual mean square for each model (see Materials and Methods for the calculation).

Figure 1.

Data and fitted curves for the CD4+ T cell count of LLO118 (upper row) and LLO56 cells (lower row). The actual measurements for each mouse (grey dots) and the median over all mice per time point are plotted (black squares) for the basic model (A, Eqs. (1a) and (1b), (a),(d)), a model assuming constant memory cell production during the proliferation phase (B, Eqs. (4a) and (4b), (b),(e)), and for a model assuming the alternative differentiation pathway (C, Eqs. (5a) and (5b), (c),(f)). The total number of CD4+ T cells (T, long-dashed line), the number of activated and effector CD4+ T cells, respectively (A, E solid line) and the number of memory cells (M, dashed line) are shown.

In none of the different models applied to the data could we find statistically significant support for a biphasic contraction phase according to an F-test. If we additionally assume a phase of rapid apoptosis for the activated CD4+ T cells in Eqs. (1a) and (4a), and the effector cells in Eq. (5b), which is characterized by the additional parameters α and Δ (see Eq. (3)), the MNSQ increased compared to a model without these parameters. The model extension with a rapid apoptosis phase did not change the overall range of the parameter values (see Supplemental Material, Table S1 and Figure S1). This is also the case if we fit each cell lineage separately with different values for T, Δ and δA for LLO118 and LLO56 (results not shown). The fits for LLO56 are generally poorer than those for LLO118 as the variation in the cell count at later time points (t ≥ 10 days) is larger (see Figure 1).

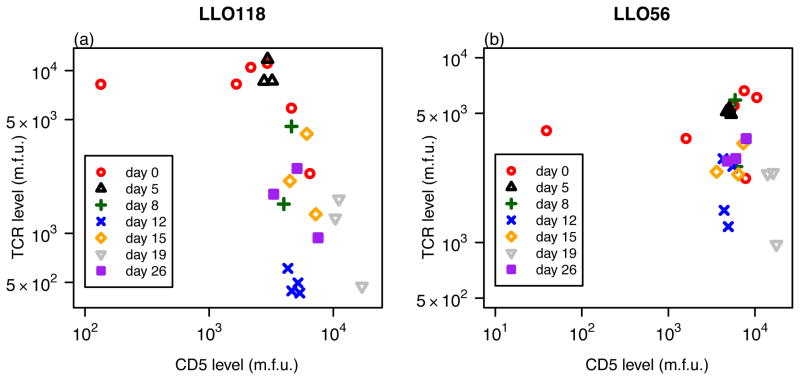

The CD5 and TCR-level

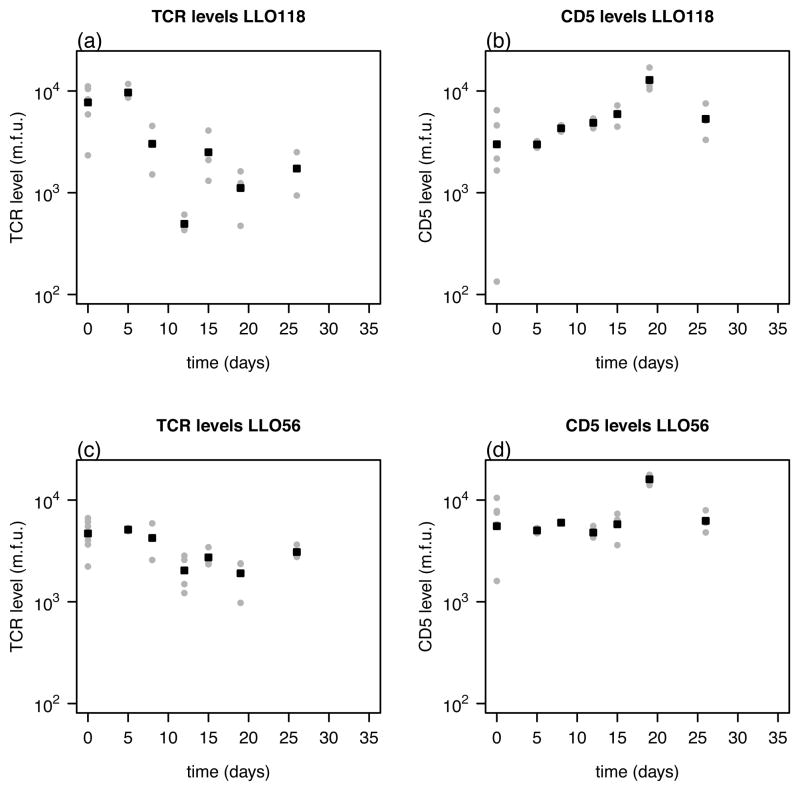

The cell surface protein CD5 is a negative regulator of T cell activation and is assumed to interfere with cell proliferation and apoptosis (17). Therefore, we examined if the different proliferation rates during primary infection could be explained by the level of CD5 expression on the surface of those cells. The CD5 expression level as well as the TCR-level was measured for the different cell lines and given in mean fluorescent units. The corresponding data are shown in Figure 2. There is a significant negative correlation between CD5 expression and the TCR-level on LLO118 CD4+ T cells (ρ = −0.697, p = 2.3 × 10−4, Spearman). We found no significant correlation between these two values for the LLO56 CD4+ T cells over all time points or if data were analyzed separately for each day where enough data points were available (p > 0.05, Spearman-Correlation) (Figure 3). There was also no significant correlation found between the total cell count and either of the CD5 or TCR levels.

Figure 2.

The measured TCR- and CD5-level for the two different CD4+ T cell lines (LLO118 - (a),(b); LLO56 - (c),(d)). Both values are given in mean fluorescent units (m.f.u.). The individual values for each mouse (grey dots) and the average over all mice per time point (black squares) are shown.

Figure 3.

The CD5 expression level measured in mean fluorescent units (m.f.u.) plotted against the TCR-level separately for LLO118 (a) and LLO56 (b). Each point represents one mouse. Symbols indicate the different time points at which mice were sampled. There is a significant correlation between CD5 and TCR-levels for LLO118 over all time points (ρ = −0.697, p = 2.3 × 10−4, Spearman). No correlation was found for LLO56 (ρ = −0.136, p = 0.53, Spearman).

CD5 and cell proliferation

As a high level of CD5 surface expression on CD4+ T cells is assumed to inhibit proliferation, we examined if the difference in the proliferation rates between LLO118 and LLO56 CD4+ T cells can be explained by the lower CD5 expression on LLO118 CD4+ T cell at the beginning of the experiment. To this end, all parameters in our models were fixed to the values estimated previously (see Table I) except for the proliferation rates ρLLO118 and ρLLO56. To include the CD5-level into our models, we first assumed that the proliferation of T cells is inversely correlated with the CD5 expression level on these cells. Therefore, ρ is replaced by ρ̂/(γ log(cd5)+1) in Eq. (1a), where cd5 is the individual CD5 expression level and ρ̂ is the proliferation rate in the absence of CD5 expression. This approach accounts for a negative effect of the CD5 expression level on the cell proliferation rate, where γ denotes a scaling constant. We log-transformed the individual CD5 expression levels as the CD5 mean fluorescent intensity can vary by more than 2 orders of magnitude (Figure 2). Fitting these revised models to the data, we find no significant difference between the proliferation rates, ρ̂, of LLO118 and LLO56 CD4+ T cells in the absence of CD5 modulation in any of the models analyzed (see Table II). This suggests that the differences in the proliferation rate ρ reported in Table I were due to differences in the CD5 expression level.

Table II.

CD5 level and proliferation rates.a

| parameter | symbol | unit | Model A | Model B | Model C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation rate | ρ̂LLO118 | day−1 | 1.38 | 1.10 | 1.21 |

| [1.21,1.54] | [1.00,1.20] | [1.06,1.35] | |||

| ρ̂LLO56 | 1.39 | 1.05 | 1.22 | ||

| [1.22,1.56] | [0.95,1.14] | [1.07,1.37] | |||

| Scaling constant | γ | log(m.f.u.)−1 | 0.045 | 0.005 | 0.020 |

Estimated proliferation rates with the assumption of a negative effect of the CD5 level on proliferation. To investigate the influence of the CD5 expression level on the proliferation rate, ρ was replaced by ρ̂/(γ log(cd5)+1), with γ a scaling constant and cd5 the individual CD5 expression level. All other parameters in the model were kept fixed to the values estimated in Table I. 95% confidence intervals for the estimates are calculated based on the standard error approximated by the Hessian-matrix.

TCR-level and memory survival

Especially at later time points after the peak of the T cell response around day 8 after the infection, the mean TCR-level on LLO118 CD4+ T cells is significantly lower than the TCR-level expressed by LLO56 CD4+ T cells (p = 0.003, paired Wilcoxon-test). As CD4+ memory T cells seem to require constant encounter of survival signals to be maintained (28), we examined if the enhanced survival of memory CD4+ T cells is related to the TCR expression level. To determine if the observed difference in the TCR expression level between LLO118 and LLO56 CD4+ T cells is able to explain the difference in the estimated death rates of memory cells (see Table I), we replaced δM by δ̂M/(μ(tcr)κ+1), where μ denotes a scaling constant and κ is a Hill-coefficient. Thus, we assume that an increased TCR-level has a beneficial effect on memory survival. We fitted the revised models to the data by keeping all parameter values fixed to the values estimated previously (see Table I) except for the death rates of memory cells and . Using this approach, the TCR expression level is not sufficient to explain the significant difference in the memory death rates between LLO118 and LLO56 CD4+ T cells in any of the models analyzed (see Table III). Using log-transformed values for the individual TCR expression levels did not change the results (data not shown).

Table III.

TCR level and cell death rates.a

| parameter | symbol | unit | Model A | Model B | Model C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death rate of memory cells |

|

day−1 | 0.158 | 0.135 | 0.140 | |

| [0.152,0.163] | [0.129,0.141] | [0.133,0.146] | ||||

|

|

0.038 | 0.044 | 0.043 | |||

| [0.032,0.043] | [0.038,0.050] | [0.037,0.049] | ||||

| Scaling constant | μ | log(m.f.u.)−1 | 0.597 | 0.034 | 0.052 | |

| Hill-coefficient | κ | 1.234 | 0.009 | 0.034 |

Estimated death rates of memory cells with the assumption of a positive effect of the TCR level on the half-life of memory cells. To incorporate the influence of the TCR-level, δM was replaced by δ̂M/(μ(tcr)κ+1), with μ a scaling constant, κ a Hill coefficient, and tcr the individual TCR expression level. All other parameters in the model were kept fixed to the values estimated in Table I. 95% confidence intervals for the estimates are calculated based on the standard error approximated by the Hessian-matrix.

Discussion

The mechanism of the generation of memory T cells, especially memory CD4+ T helper cells, is incompletely understood (14, 15, 33). In contrast to CD8+ T cells, no specific cell surface markers for CD4+ T cells have been identified that are associated with memory or effector CD4+ T cell precursor lines (14, 15). Recently, two different CD4+ T cell lines, LLO118 and LLO56, were described which differed in their primary and secondary responses to infection by L. monocytogenes (16). While LLO118 generated a much stronger primary response than LLO56 and provided more robust help to CD8+ T cells upon re-challenge, LLO56 expanded more during a secondary exposure to the pathogen. Both cell populations differed in their expression level of CD5 before L. monocytogenes infection, with LLO118 showing a much lower expression level of this cell surface protein (16).

In this study, we determined the dynamics of these two different CD4+ T cell lines in response to L. monocytogenes infection. Using different mathematical models, we quantified the rates at which T cells proliferate and die. Our models predict the size of the memory population generated and provide an estimate for the average half-life of those cells.

LLO118 CD4+ T cells have a slightly higher proliferation rate than LLO56 CD4+ T cells, with both proliferation rates on the order of ρ = 0.9 – 1.05 day−1. These proliferation rates are in the range of those estimated previously for CD4+ T cells responding to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection (23). The small but statistically significant difference in the proliferation rates of LLO118 and LLO56 can be explained by the difference in their CD5 expression levels. This is consistent with the hypothesis that higher levels of CD5 found on LLO56 CD4+ T cells inhibit TCR activity and thereby proliferation of these cells. Furthermore, by sorting LLO118 and LLO56 T cells by their CD5 expression level, we could show that LL0118 and LLO56 T cells with identical levels of CD5 proliferated to a similar extent (16). In addition, transferring the same number of LLO118 and LLO56 T cells separately into distinct mice showed no difference in the individual proliferation dynamics of the two cell types in comparison to the original co-transfer experiment (16). This indicates that competition between these two cell lines for the same MHC-antigen does not influence the proliferation dynamics in the experimental setting analyzed. Therefore, this factor was neglected in the mathematical analysis.

In our model with a continuous conversion of naïve activated T cells into memory cells, we do not see any significant difference in the memory conversion rates between LLO118 and LLO56 CD4+ T cells. For naïve CD8+ T cells, it has been observed that the strength of the antigenic signal and the duration of the antigen exposure can influence the conversion rate of naïve CD8+ T cells into memory cells (34–36). Weaker TCR signals resulted in more efficient memory formation (37–39). However, it has not been clearly shown how other factors, such as CD4+ T cell help, might additionally influence this conversion (40). If weaker TCR signaling also affects the conversion of naïve CD4+ T cells into memory cells, we would expect LLO56 CD4+ T cells to have a higher memory conversion rate than LLO118 CD4+ T cells, since these cells express higher levels of CD5 during the first 8 days after infection and CD5 is observed to act as a negative regulator of TCR signaling (17). However, this assumption could not be confirmed by our analyses. For model A, we found the opposite result with LLO118 having a faster estimated memory formation rate than LLO56, whereas models B and C yielded approximately the same memory formation rate for both types of T cells (Table I). Therefore, despite influencing the proliferation rate during the expansion phase, differences in the CD5 expression level seem not to influence the rate at which new memory cells are generated.

Besides the differing proliferation rates between the two cell lines, our models also predicted significant differences in the half-lives of the memory cells, with LLO56 CD4+ T cells having an approximately three times longer average half-life than LLO118 cells ( and ). LLO118 CD4+ T cells dramatically downregulate the TCR expression level after the peak of the immune response. The downregulated TCR expression level on LLO118 CD4+ T cells might be an effect of the faster proliferation rate which leads to a dilution of the TCR expression level. However, the differences in the half-lives of the two CD4+ T cell lines cannot be explained by the TCR expression levels on those cells in our model. Besides the TCR expression level, the TCR avidity of these two cell lines could also impact the dynamics of the two responses. The effect of TCR signaling on the generation and functionality of memory CD4+ T cell responses is poorly defined and still debated. Several experiments show that CD4+ T cells require high levels of TCR signaling, i.e., higher levels than CD8+ T cells, and long antigen exposure to generate efficient memory responses (41, 42). In contrast, in chronic infections long antigen exposure can lead to memory exhaustion, and reduced functional avidity promotes the generation of better functional CD4+ T cell responses (43). As we obtain more information on the avidity of these TCR we will be able to determine if there is a correlation between the survival of memory cells and the properties of the TCR on those cells. For example, a lower TCR avidity of LLO118 CD4+ T cells compared to LLO56 CD4+ T cells in combination with the lower TCR expression level on these cells could account for these cells getting fewer survival signals and hence explain the significantly shorter half-life that we found for LLO118 memory T cells. Further, the differing half-lives of the two types of memory cells might explain the stronger proliferative response of LLO56 CD4+ T cells upon secondary exposure seen in the experimental data (16). This might simply be a result of the fact that more LLO56 than LLO118 cells survive until the re-challenge with the pathogen.

In contrast to previous analysis done for CD4+ T cell dynamics in mice infected with LCMV, we do not see evidence of a biphasic contraction phase for CD4+ T cells after the peak of the response (23, 28). This might be due to the fact that our data were collected in a shorter timeframe (35 days compared to 921 days after infection for the LCMV-study). More detailed and longitudinal experimental analysis is needed to clearly demonstrate the existence of multi-phasic contraction phases for the two CD4+ T cell lines examined.

Our analysis determines and quantifies the CD4+ T cell dynamics for two different CD4+ T cell lines against the same epitope of L. monocytogenes. We show that differences in the CD5 expression level can explain the different proliferation rates of the two CD4+ T cell lines while the rate at which memory CD4+ T cells are generated seems to be unaffected. If and how the CD5 expression level during the proliferation phase might also influence the functionality of CD4+ T cell memory cells, i.e. providing enhanced CD8+ T cell help upon secondary infection, has still to be determined. The generation of CD5 deficient LLO118 and LLO56 mice would help to address this issue in more detail (16).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Portions of this work were done under the auspices of the U. S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC52-06NA25396 and supported by NIH grants P01-AI071195, R37-AI028433 and R01-OD011095.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ahmed R, Bevan MJ, Reiner SL, Fearon DT. The precursors of memory: models and controversies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:662–668. doi: 10.1038/nri2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jameson SC, Masopust D. Diversity in T cell memory: an embarrassment of riches. Immunity. 2009;31:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevan MJ. Understand memory, design better vaccines. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:463–465. doi: 10.1038/ni.2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pulendran B, Ahmed R. Immunological mechanisms of vaccination. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:509–517. doi: 10.1038/ni.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith CM, Wilson NS, Waithman J, Villadangos JA, Carbone FR, Heath WR, Belz GT. Cognate CD4(+) T cell licensing of dendritic cells in CD8(+) T cell immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1143–1148. doi: 10.1038/ni1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun JC, Bevan MJ. Defective CD8 T cell memory following acute infection without CD4 T cell help. Science. 2003;300(5617):339–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1083317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shedlock DJ, Shen H. Requirement for CD4 T cell help in generating functional CD8 T cell memory. Science. 2003;300(5617):337–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1082305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen EM, Lemmens EE, Wolfe T, Christen U, von Herrath MG, Schoenberger SP. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature. 2003;421(6925):852–856. doi: 10.1038/nature01441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pamer EG. Immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(10):812–823. doi: 10.1038/nri1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun JC, Williams MA, Bevan MJ. CD4+ T cells are required for the maintenance, not programming, of memory CD8+ T cells after acute infection. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(9):927–933. doi: 10.1038/ni1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrington LE, Janowski KM, Oliver JR, Zajac AJ, Weaver CT. Memory CD4 T cells emerge from effector T-cell progenitors. Nature. 2008;452:356–360. doi: 10.1038/nature06672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Löhning M, Hegazy AN, Pinschewer DD, Busse D, Lang KS, Hofer T, Radbruch A, Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Long-lived virus-reactive memory T cells generated from purified cytokine-secreting T helper type 1 and type 2 effectors. J Exp Med. 2008;205:53–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaech SM, Wherry EJ. Heterogeneity and cell-fate decisions in effector and memory CD8+ T cell differentiation during viral infection. Immunity. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacLeod MK, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Memory CD4 T cells: generation, reactivation and re-assignment. Immunology. 2010;130:10–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lees JR, Farber DL. Generation, persistence and plasticity of CD4 T-cell memories. Immunology. 2010;130:463–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber KS, Li QJ, Persaud SP, Campbell JD, Davis MM, Allen PM. Distinct CD4+ helper T cells involved in primary and secondary responses to infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:9511–9516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202408109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarakhovsky A, Kanner SB, Hombach J, Ledbetter JA, Muller W, Killeen N, Rajewsky K. A role for CD5 in TCR-mediated signal transduction and thymocyte selection. Science. 1995;269:535–537. doi: 10.1126/science.7542801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spertini F, Stohl W, Ramesh N, Moody C, Geha RS. Induction of human T cell proliferation by a monoclonal antibody to CD5. J Immunol. 1991;146:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azzam HS, DeJarnette JB, Huang K, Emmons R, Park CS, Sommers CL, El-Khoury D, Shores EW, Love PE. Fine tuning of TCR signaling by CD5. J Immunol. 2001;166:5464–5472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azzam HS, Grinberg A, Lui K, Shen H, Shores EW, Love PE. CD5 expression is developmentally regulated by T cell receptor (TCR) signals and TCR avidity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2301–2311. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer MJ, V, Mahajan S, Chen J, Irvine DJ, Lauffenburger DA. Signaling thresholds govern heterogeneity in IL-7-receptor-mediated responses of naïve CD8(+) T cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89:581–594. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Boer RJ, Oprea M, Antia R, Murali-Krishna K, Ahmed R, Perelson AS. Recruitment times, proliferation, and apoptosis rates during the CD8(+) T-cell response to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J Virol. 2001;75:10663–10669. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10663-10669.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Boer RJ, Homann D, Perelson AS. Different dynamics of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses during and after acute lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J Immunol. 2003;171:3928–3935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohler B. Mathematically modeling dynamics of T cell responses: predictions concerning the generation of memory cells. J Theor Biol. 2007;245:669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee WT, Pasos G, Cecchini L, Mittler JN. Continued antigen stimulation is not required during CD4(+) T cell clonal expansion. J Immunol. 2002;168:1682–1689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foulds KE, Zenewicz LA, Shedlock DJ, Jiang J, Troy AE, Shen H. Cutting edge: CD4 and CD8 T cells are intrinsically different in their proliferative responses. J Immunol. 2002;168:1528–1532. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bajénoff M, Wurtz O, Guerder S. Repeated antigen exposure is necessary for the differentiation, but not the initial proliferation, of naive CD4(+) T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:1723–1729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Homann D, Teyton L, Oldstone MB. Differential regulation of antiviral T-cell immunity results in stable CD8+ but declining CD4+ T-cell memory. Nat Med. 2001;7:913–919. doi: 10.1038/90950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang JT, V, Palanivel R, Kinjyo I, Schambach F, Intlekofer AM, Banerjee A, Longworth SA, Vinup KE, Mrass P, Oliaro J, Killeen N, Orange JS, Russell SM, Weninger W, Reiner SL. Asymmetric T lymphocyte division in the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Science. 2007;315:1687–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1139393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. From synapses to immunological memory: the role of sustained T cell stimulation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armitage P, Berry G. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2. Blackwell; Oxford: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moulton VR, Bushar ND, Leeser DB, Patke DS, Farber DL. Divergent generation of heterogeneous memory CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:869–876. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarkar S, Teichgraber V, Kalia V, Polley A, Masopust D, Harrington LE, Ahmed R, Wherry EJ. Strength of stimulus and clonal competition impact the rate of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2007;179:6704–6714. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith-Garvin JE, Burns JC, Gohil M, Zou T, Kim JS, Maltzman JS, Wherry EJ, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS. T-cell receptor signals direct the composition and function of the memory CD8+ T-cell pool. Blood. 2010;116:5548–5559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-292748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiehagen KR, Corbo E, Schmidt M, Shin H, Wherry EJ, Maltzman JS. Loss of tonic T-cell receptor signals alters the generation but not the persistence of CD8+ memory T cells. Blood. 2010;116:5560–5570. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-292458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fousteri G, Dave A, Juedes A, Juntti T, Morin B, Togher L, Farber DL, von Herrath M. Increased memory conversion of nave CD8 T cells activated during late phases of acute virus infection due to decreased cumulative antigen exposure. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e14502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D’Souza WN, Hedrick SM. Cutting edge: latecomer CD8 T cells are imprinted with a unique differentiation program. J Immunol. 2006;177:777–781. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Faassen H, Saldanha M, Gilbertson D, Dudani R, Krishnan L, Sad S. Reducing the stimulation of CD8+ T cells during infection with intracellular bacteria promotes differentiation primarily into a central (CD62LhighCD44high) subset. J Immunol. 2005;174:5341–5350. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Umeshappa CS, Xiang J. Regulators of T-cell memory generation: TCR signals versus CD4(+) help? Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89:578–580. doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams MA, Ravkov EV, Bevan MJ. Rapid culling of the CD4+ T cell repertoire in the transition from effector to memory. Immunity. 2008;28(4):533–545. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obst R, van Santen HM, Mathis D, Benoist C. Antigen persistence is required throughout the expansion phase of a CD4(+) T cell response. J Exp Med. 2005;201(10):1555–1565. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caserta S, Kleczkowska J, Mondino A, Zamoyska R. Reduced functional avidity promotes central and effector memory CD4 T cell responses to tumor-associated antigens. J Immunol. 2010;185(11):6545–6554. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.