Summary

Heart development requires organized integration of actin filaments into the sarcomere, the contractile unit of myofibrils, although it remains largely unknown how actin filaments are assembled during myofibrillogenesis. Here we show that Fhod3, a member of the formin family of proteins that play pivotal roles in actin filament assembly, is essential for myofibrillogenesis at an early stage of heart development. Fhod3−/− mice appear normal up to embryonic day (E) 8.5, when the developing heart, composed of premyofibrils, initiates spontaneous contraction. However, these premyofibrils fail to mature and myocardial development does not continue, leading to embryonic lethality by E11.5. Transgenic expression of wild-type Fhod3 in the heart restores myofibril maturation and cardiomyogenesis, which allow Fhod3−/− embryos to develop further. Moreover, cardiomyopathic changes with immature myofibrils are caused in mice overexpressing a mutant Fhod3, defective in binding to actin. These findings indicate that actin dynamics, regulated by Fhod3, participate in sarcomere organization during myofibrillogenesis and thus play a crucial role in heart development.

Key words: Actin, Fhod3, Formin, Myofibrillogenesis, Sarcomere

Introduction

The heart is the first organ to form and function during embryogenesis, and assures biological activities throughout the life by its contractile activity. Sufficient contraction of the developing heart requires maturation of myofibrils, composed of repeating units known as sarcomeres, where arrays of actin (thin) and myosin (thick) filaments comprise the contractile apparatus (Clark et al., 2002). In the sarcomere, barbed ends of actin filaments are anchored in the Z-line, and their pointed ends extend into the middle of the sarcomere. The initiation of the heartbeat occurs before sarcomere maturation (and thus before myofibril maturation), and is followed by myocardial development with trabeculation (formation of finger-like projections of the myocardium into the ventricular lumen) and by chamber formation, which begins with looping of the heart tube (Moorman and Christoffels, 2003; Taber, 1998). The molecular mechanisms by which the sarcomere is organized during cardiogenesis remain poorly understood.

During sarcomere organization in the striated muscle (i.e., the skeletal and cardiac muscles), actin cytoskeleton undergoes dynamic rearrangement to form mature actin filaments with uniform length and polarity (Gregorio and Antin, 2000; Littlefield and Fowler, 2008; Ono, 2010; Sanger et al., 2005). At the beginning of sarcomere organization, the I-Z-I complex (a.k.a. the Z-body) emerges in premyofibrils as a precursor of the Z-line: the complex contains filamentous actin and a cluster of Z-line proteins such as α-actinin. Subsequent alignment of the precursors leads to formation of a striated pattern of the Z-line; and unanchored (pointed) ends of actin filaments become aligned with uniform length at the final step in sarcomere organization for maturation of myofibrils (Gregorio and Antin, 2000). Several actin-associating proteins have recently been proposed as key regulator of actin dynamics during myofibrillogenesis. Nebulin, a giant actin-binding protein in the sarcomere, participates in actin filament formation in the skeletal muscle (Takano et al., 2010), whereas leiomodin, a protein related to the pointed-end capping protein tropomodulin (Tmod), serves as an actin filament nucleator in cardiomyocytes (Chereau et al., 2008). Another likely candidate for a key regulator in the cardiac muscle is Fhod3 (a.k.a. Fhos2), a member of formin family proteins (Kanaya et al., 2005). Formins are characterized by the presence of the FH1 (formin homology 1) and FH2 domains: the latter one possesses actin nucleation and polymerization activities, which are accelerated by FH1-mediated recruitment of the profilin-actin dimer (Paul and Pollard, 2009). Through cooperation by the two domains, formins direct formation of straight actin filaments (Goode and Eck, 2007; Pollard, 2007), thereby regulating diverse cytoskeletal reorganization during development (Chesarone et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010). Fhod3, as well as Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (Daam1), is a major formin in the heart (Kanaya et al., 2005; Li et al., 2011), although its truncated form is expressed in the brain and kidney (Kanaya et al., 2005). RNA interference-mediated depletion of Fhod3 in cultured cardiomyocytes disrupts sarcomere organization (Iskratsch et al., 2010; Taniguchi et al., 2009), suggesting a role of Fhod3-regulated actin dynamics. However, the role of Fhod3 in development has remained to be elucidated.

Here we show that knock out of the Fhod3 gene in mice confers lethality by embryonic day (E) 11.5 with a massive pericardial effusion. Embryonic development of Fhod3−/− mice appears normal up to E8.5. Although the developing heart tube consisting of a thin layer of the myocardium initiates spontaneous contraction and rightward looping, subsequent chamber formation and myocardial development with trabeculation are aborted in Fhod3−/− embryos. The embryonic lethality is probably due to cardiac defects, since transgenic expression of Fhod3 in the heart allows embryos to develop until before birth. In the absence of Fhod3, myofibrils in the developing heart remain premature, i.e., they are thin and sparsely distributed with irregularly spaced dots of α-actinin. Thus Fhod3 appears to play a crucial role in sarcomere (and myofibril) maturation during myocardial development.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Fhod3 knockout mice and transgenic mice overexpressing Fhod3

The Fhod3 knockout mouse (Acc. No. CDB0598K: http://www.cdb.riken.jp/arg/mutant%20mice%20list.html) was generated according to the protocols as described (http://www.cdb.riken.jp/arg/Methods.html). In brief, the 5′ homologous arms (7.5 kb) was isolated by the Red/ET recombination cloning system (Gene Bridges GmbH) and the 3′ arms (3.5 kb) was amplified by PCR using a BAC clone RPCI23-304D8 and subcloned into the DT-ApA/LacZ/Neo cassette (RIKEN CDB: http://www.cdb.riken.jp/arg/cassette.html) to generate the targeting vector. The linearized targeting vector was electroporated into TT2 embryonic stem cells (Yagi et al., 1993), and G418-resistant clones were screened by PCR and confirmed by Southern blot analysis to identify ones with correct homologous recombination. The PCR products from the wild-type and recombinant alleles were 655 bp and 862 bp in length, respectively. Chimeric mice were generated with the recombinant embryonic stem cell clones and mated with C57BL/6 females to generate heterozygous animals (Fhod3+/−), which were maintained on the C57BL/6 genetic background. Two mutant strains generated from two independent recombinant embryonic stem cell clones were analyzed. No phenotypic differences between the two strains were observed.

Transgenic mice expressing wild-type Fhod3 (GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession NO. AB078608) (Kanaya et al., 2005) under the control of the α-myosin heavy chain promoter, a generous gift from Dr. Jeffery Robbins (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center) (Gulick et al., 1991), were generated on a C57BL/6 background, as previously described (Kan-o et al., 2012); expression level of exogenous Fhod3 in the transgenic mice was ten-fold more than that of endogenous Fhod3. Transgenic mice expressing a mutant Fhod3 carrying the I1127A substitution (Taniguchi et al., 2009) under the control of the α-myosin heavy chain promoter were also generated on a C57BL/6 background. Expression level of the mutant Fhod3 in the transgenic mice was ten-fold more than that of endogenous (wild-type) Fhod3 (supplementary material Fig. S4).

All mice were kept in a specific pathogen-free animal facility at Kyushu University. All procedures using mice were performed in strict accordance with the guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments (Science Council of Japan). The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyushu University (Permit Number: A22-005-1). All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

LacZ staining

LacZ staining of heterozygous Fhod3+/− embryos was performed as described by Shima et al. (Shima et al., 2005). Briefly, timed pregnant mice were sacrificed via cervical dislocation and embryos were dissected from the uterus. Embryos were fixed at 4°C by immersion in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS: 137 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.47 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 1% formaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde, 0.02% Nonidet P-40, and 1 mM MgCl2. The whole body of embryos was incubated overnight at 37°C in PBS containing 1 mg/ml X-gal, 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, and 2 mM MgCl2. For detailed observation of cardiac looping, the head and tail were excised.

Histological analysis

Timed pregnant mice were sacrificed via cervical dislocation and embryos were dissected from the uterus. Dissected embryos were fixed by immersion in a solution containing 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS at 4°C. In the case of embryos at E17.5, the heart was removed from mice under hypothermal anesthesia (Kulandavelu et al., 2006) and then fixed. Fixed embryos or hearts were dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunofluorescence staining

Timed pregnant mice were sacrificed via cervical dislocation and the uterus was removed. Embryos at E8.5–13.5 were dissected in cold PBS, and the whole body was fixed by immersion in 3.7% formaldehyde for 6 h (E8.5) or for 12 h (E9.5–13.5) at 4°C. E17.5 embryos were anesthetized by hypothermia, whereas 8-day-old neonates were anesthetized by sevoflurane inhalation. They were subjected to perfusion fixation as follows: after clamping of the ascending aorta and clipping of the right atrium, 1 ml of PEM buffer (1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM PIPES, pH 6.9) containing 20 mM KCl was administrated from the left ventricle using a pulled capillary tube, followed by perfusion of 3 ml of 3.7% formaldehyde. The fixed hearts were removed from the deceased mice, cut into small pieces, and immersed for 90 min at 4°C in the same fixative for post-fixation. The fixed whole embryo or heart was washed in PBS, subjected to osmotic dehydration overnight at 4°C in 30% sucrose, and embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek). The blocks were frozen and cut into 5 µm sections using a cryostat (HM550; Thermo Scientific). Then sections were washed with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with a blocking buffer (PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin and 2% goat serum) for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were labeled overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in the blocking buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100, washed in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, and then labeled for 1 h at 37°C with a fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody mixture in the same buffer containing Alexa-594-phalloidine (Invitrogen) for F-actin staining. Images were taken with an LSM510 confocal scanning laser microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging).

Antibodies

In immunoblot analysis for Fhod3, affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for Fhod3 were raised to the peptide of amino acid residues 873–974 and prepared as previously described (Kanaya et al., 2005; Taniguchi et al., 2009). In immunostaining for Fhod3 of sections of embryonic hearts (supplementary material Fig. S2), another anti-Fhod3 antibodies (anti-Fhod3-(C-20) antibodies), which were raised to the peptide of amino acid residues 1,567–1,586, were used (Kanaya et al., 2005; Kan-o et al., 2012). The mouse monoclonal antibody against α-actinin (clone EA-53) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; the mouse monoclonal antibody against glyceraldehyhyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) from Chemicon; and the fluorescent secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 against mouse IgG from Invitrogen.

Analysis of embryonic heartbeat

Time-lapse recording of the embryonic heartbeat was performed according to the method of Nishii and Shibata (Nishii and Shibata, 2006) with minor modifications. Briefly, timed pregnant mice were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg body weight) and dissected on a thermal plate at 37°C. For maintenance of the placental circulation, each decidual swelling was removed just before the observation. The embryos were dissected and their heartbeat was observed at 37°C in M2 medium (Fulton and Whittingham, 1978). Here the extraembryonic membrane of E9.5–10.5 embryos was removed, while that of E8.5 embryos was intact. Images were recorded by a digital camera (DP21; Olympus) connected to a dissecting microscope (SZX16; Olympus). Kymographs were generated from time-lapse images in ImageJ software (National Institute of Health) by cropping a 2-pixel-wide rectangular region, making a montage of time-lapse sequences of cropped regions, and adjusting contrast.

Transmission electron microscopic analysis

Transmission electron microscopy of thin sections was performed as described by Koga et al. with minor modifications (Koga et al., 1990). Briefly, embryos were dissected and fixed with a fix buffer (2.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1 M sucrose, 3 mM CaCl2, and 0.1 M sodium cacodylate, pH 7.4) for 2 h, followed by rinse overnight at 4°C in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate. Then embryos were postfixed for 1 hr with 1% OsO4, dehydrated in ethanol and propylene oxide, and embedded in the Epon 812 resin. Thin sections containing the heart were stained for 10 min with uranyl acetate, and for 15 min with lead acetate, and then examined with a JEM-2000EX (JOEL).

TAC surgery and measurement of cardiac function

TAC surgery was performed on 8 to 10-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice as previously described (Nishida et al., 2008). Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using a Toshiba ultrasonic image analyzing system (Nemio-XG) equipped with 7.5 MHz imaging transducer. LV pressure and heart rate were measured with a micronanometer catheter (Millar 1.4F, SPR 671, Millar Instruments). Statistical comparisons were performed by two-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni procedure for comparison of means.

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (Kanaya et al., 2005; Taniguchi et al., 2009). Briefly, the whole body of E9.5 embryos was homogenized and sonicated at 4°C in a lysis buffer (10% glycerol, 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysates were applied to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore), which was probed with the anti-Fhod3 antibodies, followed by development using ECL-plus (GE Healthcare) for visualization of the antibodies. For estimation of the amount of Fhod3, densitometric analysis was performed using a LAS-1000 image analyzer (Fujifilm).

Results

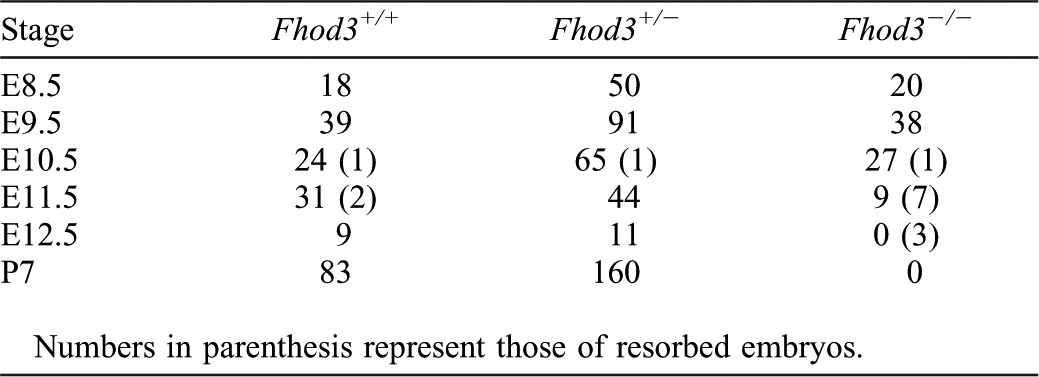

Disruption of both Fhod3 alleles leads to embryonic lethality by E11.5

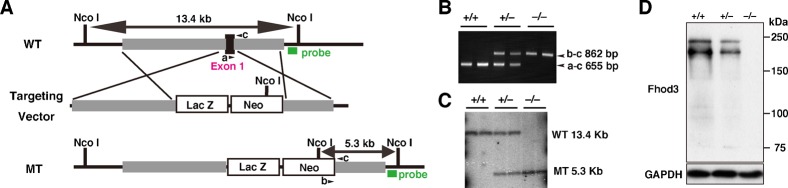

To clarify the role of Fhod3 in vivo, we generated a targeted deletion of Fhod3 exon 1 in embryonic stem cells by replacing it with β-galactosidase (lacZ) reporter gene (Fig. 1A). Adult heterozygous Fhod3+/− mice appeared phenotypically normal and fertile. However, intercrosses of Fhod3+/− mice did not produce any Fhod3−/− mice in their litters. PCR genotyping of yolk sac DNAs (Fig. 1B) revealed that Fhod3−/− embryos were present until E11.5, but not beyond that point (Table 1). Although the genotypes of embryos at E8.5–10.5 fit reasonably well to a Mendelian distribution, Fhod3−/− embryos were resorbed by E12.5. Southern blot analysis of genomic DNAs isolated from the whole body of embryos confirmed the genotype determined by PCR using yolk sac DNAs (Fig. 1C). As demonstrated by immunoblot analysis of the whole body extracts at E9.5, Fhod3−/− embryos had no detectable Fhod3 protein, whereas Fhod3+/− embryos had about 45.1±5.0% (n = 4) of the amount of Fhod3 in wild-type embryos (Fig. 1D). Fhod3 was detected as doublet, where the upper and lower bands denote the cardiac and brain isoforms, respectively (supplementary material Fig. S1).

Fig. 1. Targeted disruption of the Fhod3 gene.

(A) Schematic representation of the Fhod3 gene-targeting strategy. Exon 1 of the Fhod3 gene is represented as a box in black; flanking isogenic genomic DNAs in light gray; and the targeting cassette in white. Green bars indicate probes used for Southern blot analysis, and expected sizes of fragments obtained after NcoI digestion are indicated in base pair. Small black arrowheads indicate primers for PCR genotyping. (B) PCR analysis of the embryonic yolk sac DNAs from wild-type (+/+), Fhod3+/− (+/−), and Fhod3−/− (−/−) embryos. The 655-bp and 862-bp fragments were produced with the wild-type and recombinant alleles, respectively. (C) Southern blot analysis of NcoI-digested tail DNAs. The wild-type and recombinant alleles were detected as 13.4-kbp and 5.3-kbp fragments, respectively. (D) Detection of Fhod3 protein by immunoblot analysis. Proteins prepared from the whole embryo of wild-type (+/+), Fhod3+/− (+/−), and Fhod3−/− (−/−) mice at E9.5 were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Fhod3 and anti-GAPDH antibodies.

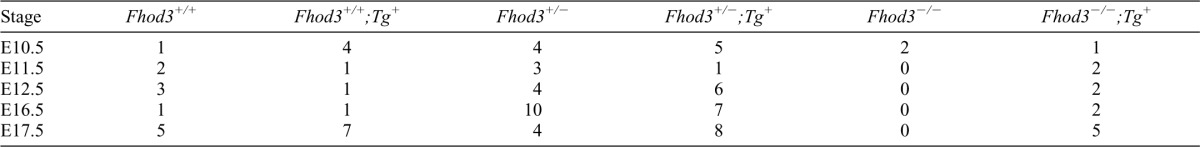

Table 1. Genotypes of offspring from heterozygous matings of Fhod3+/− mice.

Fhod3−/− embryos are grossly stunted and malformed with aborted development of the myocardium at mid-gestation

We examined expression of the targeted Fhod3lacZ allele during embryogenesis by X-gal staining of heterozygous Fhod3+/− embryos, which were morphologically indistinguishable from wild-type embryos (Fig. 2A, upper and middle panels). X-gal staining was detected in the cardiac crescent of E7.5 embryos, and became prominent by E8.5. Weak X-gal staining was also detected in the neural tube at E8.5, becoming stronger at E9.5. Expression of Fhod3 in the heart and brain appears to be kept to adulthood, since Fhod3 is abundantly expressed in these tissues of adult mice (Kanaya et al., 2005). In addition, anti-Fhod3 (C-20) antibodies were able to detect endogenous Fhod3 protein at E11.5 and E13.5 (supplementary material Fig. S2). It should be noted that Fhod3 localizes as two closely spaced bands in middle of the sarcomere, as observed in embryonic hearts at later stages and adult ones (Kan-o et al., 2012) as well as in cultured cardiomyocytes (Iskratsch et al., 2010; Taniguchi et al., 2009).

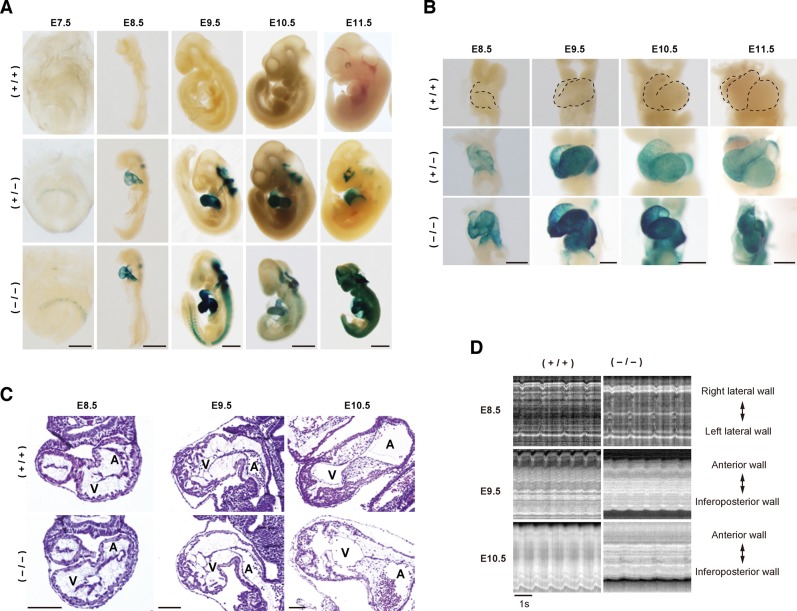

Fig. 2. Cardiac development in Fhod3−/− embryos at E9.5–11.5.

(A) Whole-mount lacZ staining of Fhod3+/+ (+/+), Fhod3+/− (+/−), and Fhod3−/− (−/−) embryos at E7.5–11.5. Bars: (E7.5) 250 µm; (E8.5/E9.5) 500 µm; (E10.5/E11.5) 1 mm. (B) Looping of the heart tube between E8.5 and E11.5 (front view). Bars: (E8.5/E9.5) 250 µm; (E10.5/E11.5) 500 µm. The contour of the wild-type heart is indicated by dotted lines. (C) Histological analysis of embryonic hearts between E8.5 and E10.5. Transverse sections (E8.5) and longitudinal sections (E9.5/E10.5) of hearts were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Bars, 100 µm. (D) Kymographic analysis of beating of embryonic hearts between E8.5 and E10.5. The kymographs were generated from supplementary material Movies 1–6, and oriented so that the right lateral and left lateral walls are upward and downward, respectively (E8.5), or the anterior and inferoposterior walls are upward and downward, respectively (E9.5 and E10.5).

Fhod3−/− embryos at E7.5–8.5 were comparable to wild-type and Fhod3+/− ones in size and gross morphology, appearing remarkably normal (Fig. 2A, lower panels). However, Fhod3−/− embryos died with a massive pericardial effusion and were resorbed by E12.5. At E9.5 they were smaller than their wild-type and Fhod3+/− littermates with obvious retardation in looping of the heart tube (Fig. 2A,B); and growth retardation was more evident at E10.5. As demonstrated by histological analysis of the ventricular wall of wild-type embryos (Fig. 2C, upper panels) and Fhod3+/− embryos (data not shown), myocardial mass increased by trabeculation at E9.5 and the increment became prominent at E10.5 (Sedmera et al., 2000). On the other hand, retardation or arrest of trabecula formation was observed at E10.5 in Fhod3−/− embryos: their myocardium appeared to lack well-defined trabeculae in comparison to that of the wild-type embryos (Fig. 2C, lower panels) as well as that of Fhod3+/− embryos (data not shown). Thus myocardial development is aborted by E10.5 in Fhod3−/− embryos; in contrast, the heart of Fhod3+/− embryos is developed in the same manner as that of the wild-type ones, which is consistent with the finding that Fhod3+/− mice are grown up normally after birth and fertile. In addition, as expected, yolk sac vascular vessels were not well formed in Fhod3−/− mice (data not shown), a phenotype that is observed in other mutant mice that are defective in cardiomyogenesis (Huang et al., 2003; Krüger et al., 2000; Lucitti et al., 2007).

The heart of Fhod3−/− embryos beats spontaneously for a short period

To determine the effect of Fhod3 deficiency on embryonic heart function, we analyzed a contractive activity of Fhod3−/− and wild-type embryos. At E8.0–8.5, the heart of Fhod3−/− embryos did beat spontaneously, as that of wild-type ones (Fig. 2D, upper panels; supplementary material Movies 1, 2). At E9.5, the ventricular wall of the Fhod3−/− embryo heart was hypokinetic when compared with that of the wild-type heart (Fig. 2D, middle panels; supplementary material Movies 3, 4). At E10.5, a stage when a defect of trabeculation was evident in mutant embryos by histological analysis (Fig. 2C), the ventricle of Fhod3−/− embryos twitched only for the first 15–20 min after removal of the yolk sac, whereas the heart of wild-type embryos continued to beat vigorously during the observation period (15–20 min) (Fig. 2D, lower panels; supplementary material Movies 5, 6). Some of Fhod3−/− embryos at E10.5 had a massive pericardial effusion and their hearts did not beat at all (supplementary material Movie 7). Thus the heart of Fhod3−/− embryos initiates spontaneous contraction that continues only at initial stages of cardiac development. On the other hand, hearts of Fhod3+/− embryos functioned as those of the wild-type ones did (data not shown).

Premyofibrils fail to mature in the heart of Fhod3−/− embryos

To investigate the mechanism for impaired cardiac contraction in Fhod3−/− embryos, we examined myofibril assembly in the heart of Fhod3−/− embryos and wild-type ones by immunofluorescence staining for sarcomeric α-actinin, a protein that is a major component of both the I-Z-I complex and the Z-line and thus a suitable marker for myofibril assembly (Fritz-Six et al., 2003; Holtzer et al., 1997). At E8.5, Fhod3−/− embryos were normal in morphology and histology (Fig. 2) and their hearts initiated spontaneous beating (supplementary material Movies 1, 2). At this stage, premyofibrils with Z-bodies, indicated by periodic dots of sarcomeric α-actinin, and with continuous or periodic F-actin staining were observed in Fhod3−/− embryos as well as wild-type ones (Fig. 3A). In wild-type embryos at E9.5, myofibrils contained regularly spaced bands of sarcomeric α-actinin with a striated F-actin staining pattern (Fig. 3B). Fully matured myofibrils, showing regular sarcomeric α-actinin striations (characteristic of mature Z-lines), were observed in wild-type embryos at E10.5 (Fig. 3C), when an increment of myocardial mass was obvious by histological analysis and the heart beat more vigorously (Fig. 2). Concomitantly, phalloidin staining became prominent by E10.5, indicating a marked increase in actin filaments. In contrast, no striated myofibrils was observed in the heart of Fhod3−/− embryos; instead a few numbers of premyofibril-like structures with irregularly spaced dots or aggregates of sarcomeric α-actinin were sparsely distributed (Fig. 3B,C). In addition, unlike wild-type embryos, intense staining with phalloidin was not observed in Fhod3−/− embryos. It is thus possible that, although premyofibrils with Z-bodies were formed in the E8.5 mutant embryos, they have been disassembled and/or aggregated by E9.5.

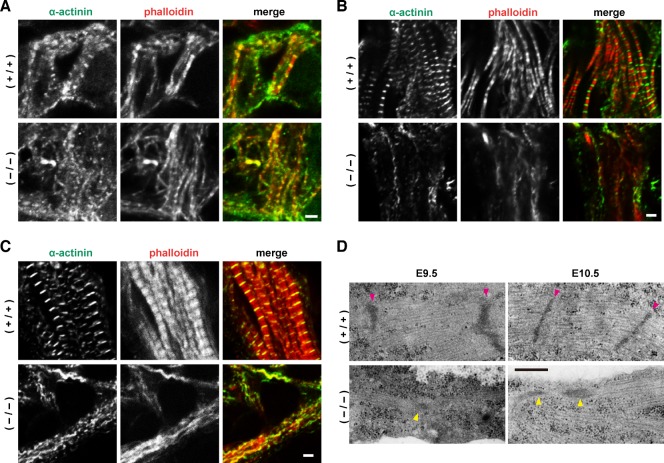

Fig. 3. Myofibrils in the embryonic heart.

(A–C) Confocal fluorescence micrographs of hearts of wild-type (+/+) and Fhod3−/− (−/−) embryos. Sections of embryonic hearts at E 8.5 (A), E9.5 (B), and E10.5 (C) were subjected to immunofluorescent staining for α-actinin (green) and phalloidin staining for F-actin (red). Bars, 2 µm. (D) Electron micrographs of thin sections of wild-type (+/+) and Fhod3−/− (−/−) hearts at E9.5 and E10.5. Magenta and yellow arrowheads indicate Z-lines and Z-body-like electron-dense spots, respectively. Bar, 500 nm.

We further examined the ultrastructure of myofibrils using transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 3D; supplementary material Fig. S3). In the wild-type embryos, the sarcomere was well organized by E10.5 with mature Z-lines; and a part of the Z-lines associated with fascia adherens, which appears to be a forming intercalated disc. In contrast, in Fhod3−/− embryos, only irregular Z-body-like electron-dense spots were observed beneath the sarcolemma, i.e., the plasma membrane of cardiomyocytes. Thus myofibrillogenesis in Fhod3−/− embryos appears to be aborted at the stage when premyofibrils mature into striated myofibrils.

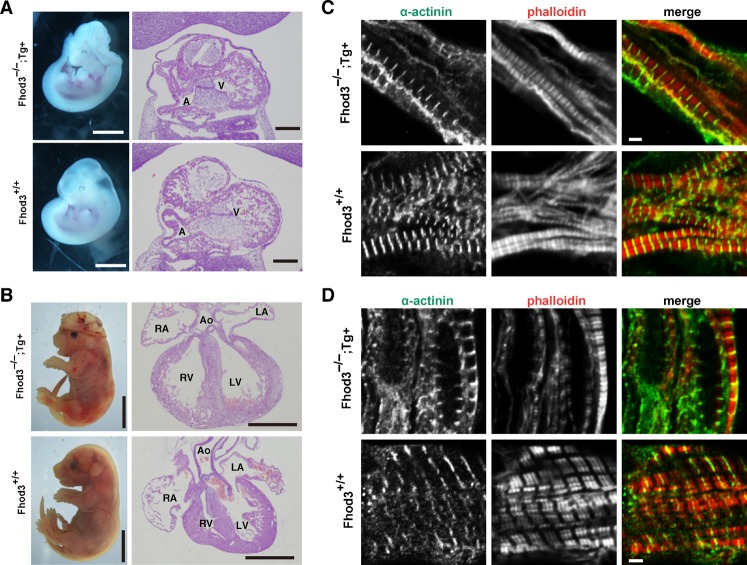

Transgenic expression of wild-type Fhod3 in the heart rescues cardiac defects of Fhod3−/−embryos

In addition to high expression in the heart, Fhod3 was considerably expressed in the neural tube (Fig. 2A). All the Fhod3−/− embryos showed defects in neural tube closure, which is normally completed by E9.5 (Fig. 2A). This indicates that Fhod3 is involved in development of organs other than the heart. To investigate whether embryonic lethality of Fhod3 nulls at mid-gestation is caused by defects in the heart, we performed a transgenic rescue experiment by expressing Fhod3 specifically in the myocardium under the control of the α-myosin heavy chain (MHC) promoter. The well-characterized α-MHC promoter is specifically and highly expressed in the developing myocardium (Gulick et al., 1991; Kan-o et al., 2012). Hemizygous Fhod3Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) mice survived to adulthood and were fertile without obvious abnormality. Although intercrosses of Fhod3+/− and Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) did not produce any Fhod3−/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) mice, analysis of embryos revealed that Fhod3−/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) embryos developed well beyond the Fhod3−/− lethal stage (Table 2). As shown in Fig. 4A, the myocardium of the ventricle of Fhod3−/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) embryos at E11.5 well developed with fine trabeculation, similarly to that of wild-type embryos. At E17.5, Fhod3−/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) embryos, having a well-developed heart, were indistinguishable from wild-type embryos at the morphological level except for exencephaly (Fig. 4B). In the heart of Fhod3−/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) embryos, myofibrils exhibited regularly spaced bands of sarcomeric α-actinin along with a striated F-actin pattern at E10.0 (Fig. 4C), and fully matured myofibrils were found at E17.5 (Fig. 4D); full maturation was indicated by clear gaps in F-actin staining at the center of the sarcomere (Fig. 4D). Thus transgenic expression of Fhod3 in the heart sufficiently rescues defects in sarcomere organization and myocardial development, indicating that the lethality of Fhod3−/− mice by E11.5 occurs as the direct result from aborted cardiac development.

Table 2. Genotypes of offspring from matings of Fhod3+/− × Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3).

Fig. 4. Effect of transgenic expression of Fhod3 in the heart of Fhod3−/− mice.

(A,B) Whole-mount (left panels) and histological (right panels) analyses of wild-type (Fhod3+/+) and Fhod3−/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) (Fhod3−/−;Tg+) embryos at E11.5 (A) and E17.5 (B). V, ventricle; A, atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; Ao, aorta. Bars in A: (left) 1 mm; (right) 200 µm. Bars in B: (left) 5 mm; (right) 1 mm. (C,D) Confocal fluorescence micrographs of hearts of wild-type (+/+) and Fhod3−/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3) (Fhod3−/−;Tg+) embryos at E10.0 (C) and E17.5 (D). Sections of embryonic hearts were subjected to immunofluorescent staining for α-actinin (green) and phalloidin staining for F-actin (red). Bars, 2 µm.

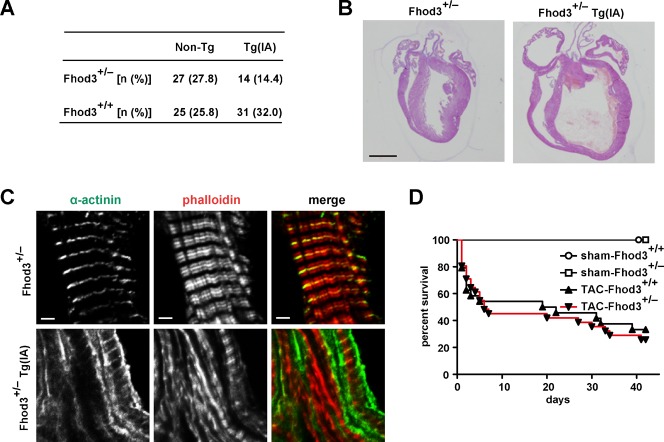

Overexpression of an actin binding-defective Fhod3 in the heart inhibits myofibril maturation

To investigate how Fhod3 functions in heart development, we generated transgenic mice expressing a mutant Fhod3 carrying the I1127A substitution under the control of the α-MHC promoter (Fhod3Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA)) (supplementary material Fig. S4). The mutant protein, defective in binding to actin, fails to induce actin assembly in HeLa cells and to promote sarcomere organization in cultured cardiomyocytes (Taniguchi et al., 2009). Hemizygous Fhod3Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA) mice survived to adulthood and were fertile. On the other hand, their intercrosses with Fhod3+/− mice failed to generate the expected Mendelian ratio (25%) of inheritance in offspring: Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA) made up only 14.4% of all pups (14 of 97 pups) at postnatal day 8 (P8) (Fig. 5A). These Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA) pups all died within 3 weeks after birth. Since the activity of the α-MHC promoter is enhanced after birth (Gulick et al., 1991), Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA) neonates, with an increased amount of Fhod3 (I1127A), may be affected more severely than the corresponding embryos. The heart of Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA) at P7 was markedly dilated and its ventricular wall was thinner with the lack of the non-compacted layer of the myocardium, compared with the heart of Fhod3+/− mice at P7 (Fig. 5B). In the mutant heart there existed myofibrils with various degrees of maturation defect, such as ones containing continuous F-actin and α-actinin aggregates concentrated along the sarcolemma (Fig. 5C). In contrast to Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA) mice, Fhod3+/− mice without the transgene were functionally equivalent to wild-type ones even after pressure overload by surgical transverse aortic constriction (TAC) (Fig. 5D; supplementary material Fig. S5). These findings suggest that cardiac overexpression of a mutant Fhod3 protein, defective in an in vivo actin-assembling activity, inhibits myofibril maturation, leading to compromised heart function. Thus the actin-assembling activity appears to be crucial for Fhod3 function during cardiac development.

Fig. 5. Transgenic expression of Fhod3 (I1127A) in the heart.

(A) Genotypes of offspring from the mating of Fhod3+/− × Fhod3+/+Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA). The number in parentheses indicates the percentage of the total number of offspring. (B) Histological analysis of hearts from Fhod3+/− and Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA) (Fhod3+/−Tg(IA)) mice at age of 8 day. Bars, 100 µm. (C) Confocal fluorescence micrographs of hearts from Fhod3+/− and Fhod3+/−Tg(α-MHC-Fhod3IA) (Fhod3+/−Tg(IA)) mice at P8. Sections of hearts were subjected to immunofluorescent staining for α-actinin (green) and phalloidin staining for F-actin (red). Bars, 2 µm. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves versus days after TAC. TAC-Fhod3+/+ (n = 24); TAC-Fhod3+/− (n = 31); sham-Fhod3+/+ (n = 4); and sham-Fhod3+/− (n = 4) mice.

Discussion

In the present study we show that the mammalian formin Fhod3 plays a crucial role in sarcomere (and myofibril) maturation during heart development. Fhod3−/− mice are embryonic lethal with a massive pericardial effusion. Although the developing heart tube of Fhod3−/− embryos initiates rightward looping, subsequent chamber formation and myocardial development with trabeculation are aborted. The present histochemical analysis demonstrates that premyofibrils with periodic dots of α-actinin are formed by E8.5 in the heart, but fail to mature into striated mature myofibrils. These phenotypes are similar to those of conventional knock-out mice of Tmod1 (Fritz-Six et al., 2003). In Tmod1-null embryos, although myofibril maturation does not occur, F-actin content apparently increases beyond E8.5 (Fritz-Six et al., 2003). In contrast, the increase is not observed in Fhod3-null embryos, supporting the idea that Fhod3 is involved in actin assembly per se during myofibril maturation.

Transgenic expression of Tmod1 in the heart using α-MHC promoter completely rescues the viability of Tmod1-null mice (McKeown et al., 2008). On the other hand, heart-specific expression of Fhod3 under the control of the same promoter allows Fhod3−/− embryos to develop until before birth, but fails to restore exencephaly. The cardiac defects thus do not appear to be responsible for failure in neural tube closure, which may be attributed to the absence of Fhod3 in the brain. On the other hand, the in vivo cardiac defects agree well with the observation that sarcomere organization is disrupted by depletion of Fhod3 in cultured cardiomyocytes (Iskratsch et al., 2010; Taniguchi et al., 2009).

Spontaneous contraction of the developing heart initiates at the stage when it consists of a thin layer of the myocardium composed of immature cardiomyocytes containing premyofibrils. Fhod3 does not seem to play a major role at this stage, because the heart tube with premyofibrils formed does beat spontaneously in Fhod3−/− embryos. On the other hand, cardiac premyofibrils fail to mature into striated myofibrils in the absence of Fhod3. The maturation is known to require a drastic increase in well-aligned actin filaments, which is induced by facilitated actin polymerization (Ono, 2010). Consistent with this, myofibril maturation is disturbed by depletion of actin nucleators such as leiomodin and nebulin (in conjunction with N-WASP) from striated muscle cells (Chereau et al., 2008; McElhinny et al., 2005; Takano et al., 2010). The marked increment in actin filaments is not observed in Fhod3−/− embryos, suggesting that Fhod3 contributes to regulation of actin dynamics during myofibril maturation. This is supported by the previous in vitro finding that expression of wild-type Fhod3, but not a mutant Fhod3 defective in an actin-assembling activity, rescues sarcomere organization in cardiomyocytes depleted of endogenous Fhod3 (Taniguchi et al., 2009).

We have recently demonstrated that, in both embryonic (at around E16) and adult hearts, Fhod3 localizes in the middle of the sarcomere (Kan-o et al., 2012); the same localization of Fhod3 is observed in the embryonic heart at earlier stages (E11.5 and E13.5) (supplementary material Fig. S2). In more detail, Fhod3 localizes not at the pointed ends of thin actin filaments but to a more peripheral zone, where thin filaments overlap with thick myosin filaments (Kan-o et al., 2012). At the overlapping region, localized mechanical breakage of actin filaments may occur during muscle contraction, presumably due to myosin-driven force (Murphy et al., 1988). The breakage may subsequently induce reorganization of actin filaments at the overlapping region; it has been suggested that acto-myosin contraction causes actin filament disassembly and reorganization in muscle cells as well as non-muscle cells (Skwarek-Maruszewska et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2010). The contraction-dependent reorganization of actin filaments may be possibly involved in Fhod3-mediated myofibril maturation during heart development. Further studies are needed to elucidate the precise molecular mechanism of Fhod3 action in cardiogenesis.

It has recently been reported that Daam1, another member of the formin family proteins, is required for heart morphogenesis (Li et al., 2011). The onset of cardiac expression of Daam1 is later than that of Fhod3; Fhod3 expression can be detected in the cardiac crescent of E7.5 embryos (Fig. 2A). In addition, cardiac defects induced by Daam1 depletion in mice become evident only after myofibril maturation, leading to embryonic lethality after E14.5. In contrast, Fhod3-deficient mice exhibit lethality by E11.5, as shown in the present study. Thus Daam1 seems to participate in a later stage of cardiac development, which may regulate cardiomyocyte adhesion or migration (Li et al., 2011). Cardiac development likely requires multiple members of formin family proteins to regulate actin cytoskeleton at different stages.

As shown in the present study, overexpression of a mutant Fhod3 protein with the I1127A substitution, defective in an in vivo actin-assembling activity (Taniguchi et al., 2009), can induce cardiomyopathic changes with immature myofibrils even in the presence of a wild-type allele. Since formin family proteins are known to function as a dimer (Goode and Eck, 2007; Pollard, 2007), such a mutant Fhod3 protein may form a non-functional heterodimer with the wild-type protein, raising the possibility that a loss-of-function mutation in the FHOD3 gene may cause familial cardiomyopathy with autosomal dominant inheritance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Masaya Oki (Kyushu University), Yuichi Shima (Kyushu University), and Kanako Miyabayashi (Kyushu University) for advice on analysis of embryonic mice; Dr. Kiyomasa Nishii (National Defense Medical College) for advice on observation of heartbeat using videomicroscopy; Dr. Jeffery Robbins (Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center) for providing α-MHC promoter; Masato Tanaka (Kyushu University) for generation of transgenic mice; Masafumi Sasaki (Kyushu University) and Ryo Ugawa (Kyushu University) for electron microscopic analysis; Norihiko Kinoshita (Kyushu University) for histochemical analysis; Yohko Kage (Kyushu University), Natsuko Morinaga (Kyushu University), and Namiko Kubo (Kyushu University) for technical assistance; and Minako Nishino (Kyushu University) for secretarial assistance. We also appreciate, for technical support, the Research Support Center, Kyushu University Graduate School of Medical Sciences and the Laboratory for Technical Support, Medical Institute of Bioregulation, Kyushu University. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research and Targeted Proteins Research Program (TPRP) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan, and by the Japan Foundation for Applied Enzymology and the Nakatomi Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Chereau D., Boczkowska M., Skwarek–Maruszewska A., Fujiwara I., Hayes D. B., Rebowski G., Lappalainen P., Pollard T. D., Dominguez R. (2008). Leiomodin is an actin filament nucleator in muscle cells. Science 320, 239–243 10.1126/science.1155313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesarone M. A., DuPage A. G., Goode B. L. (2010). Unleashing formins to remodel the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 62–74 10.1038/nrm2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K. A., McElhinny A. S., Beckerle M. C., Gregorio C. C. (2002). Striated muscle cytoarchitecture: an intricate web of form and function. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 18, 637–706 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.012502.105840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz–Six K. L., Cox P. R., Fischer R. S., Xu B., Gregorio C. C., Zoghbi H. Y., Fowler V. M. (2003). Aberrant myofibril assembly in tropomodulin1 null mice leads to aborted heart development and embryonic lethality. J. Cell Biol. 163, 1033–1044 10.1083/jcb.200308164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton B. P., Whittingham D. G. (1978). Activation of mammalian oocytes by intracellular injection of calcium. Nature 273, 149–151 10.1038/273149a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode B. L., Eck M. J. (2007). Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 593–627 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio C. C., Antin P. B. (2000). To the heart of myofibril assembly. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 355–362 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01793-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulick J., Subramaniam A., Neumann J., Robbins J. (1991). Isolation and characterization of the mouse cardiac myosin heavy chain genes. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 9180–9185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzer H., Hijikata T., Lin Z. X., Zhang Z. Q., Holtzer S., Protasi F., Franzini–Armstrong C., Sweeney H. L. (1997). Independent assembly of 1.6 µm long bipolar MHC filaments and I-Z-I bodies. Cell Struct. Funct. 22, 83–93 10.1247/csf.22.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Sheikh F., Hollander M., Cai C., Becker D., Chu P. H., Evans S., Chen J. (2003). Embryonic atrial function is essential for mouse embryogenesis, cardiac morphogenesis and angiogenesis. Development 130, 6111–6119 10.1242/dev.00831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskratsch T., Lange S., Dwyer J., Kho A. L., dos Remedios C., Ehler E. (2010). Formin follows function: a muscle-specific isoform of FHOD3 is regulated by CK2 phosphorylation and promotes myofibril maintenance. J. Cell Biol. 191, 1159–1172 10.1083/jcb.201005060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya H., Takeya R., Takeuchi K., Watanabe N., Jing N., Sumimoto H. (2005). Fhos2, a novel formin-related actin-organizing protein, probably associates with the nestin intermediate filament. Genes Cells 10, 665–678 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan–o M., Takeya R., Taniguchi K., Tanoue Y., Tominaga R., Sumimoto H. (2012). Expression and subcellular localization of mammalian formin Fhod3 in the embryonic and adult heart. PLoS ONE 7, e34765 10.1371/journal.pone.0034765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y., Sasaki M., Nakamura K., Kimura G., Nomoto K. (1990). Intracellular distribution of the envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus and its role in the production of cytopathic effect in CD4+ and CD4- human cell lines. J. Virol. 64, 4661–4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger O., Plum A., Kim J. S., Winterhager E., Maxeiner S., Hallas G., Kirchhoff S., Traub O., Lamers W. H., Willecke K. (2000). Defective vascular development in connexin 45-deficient mice. Development 127, 4179–4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulandavelu S., Qu D., Sunn N., Mu J., Rennie M. Y., Whiteley K. J., Walls J. R., Bock N. A., Sun J. C., Covelli A.et al. (2006). Embryonic and neonatal phenotyping of genetically engineered mice. ILAR J. 47, 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Hallett M. A., Zhu W., Rubart M., Liu Y., Yang Z., Chen H., Haneline L. S., Chan R. J., Schwartz R. J.et al. (2011). Dishevelled-associated activator of morphogenesis 1 (Daam1) is required for heart morphogenesis. Development 138, 303–315 10.1242/dev.055566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield R. S., Fowler V. M. (2008). Thin filament length regulation in striated muscle sarcomeres: pointed-end dynamics go beyond a nebulin ruler. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 19, 511–519 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R., Linardopoulou E. V., Osborn G. E., Parkhurst S. M. (2010). Formins in development: orchestrating body plan origami. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803, 207–225 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucitti J. L., Jones E. A., Huang C., Chen J., Fraser S. E., Dickinson M. E. (2007). Vascular remodeling of the mouse yolk sac requires hemodynamic force. Development 134, 3317–3326 10.1242/dev.02883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElhinny A. S., Schwach C., Valichnac M., Mount–Patrick S., Gregorio C. C. (2005). Nebulin regulates the assembly and lengths of the thin filaments in striated muscle. J. Cell Biol. 170, 947–957 10.1083/jcb.200502158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown C. R., Nowak R. B., Moyer J., Sussman M. A., Fowler V. M. (2008). Tropomodulin1 is required in the heart but not the yolk sac for mouse embryonic development. Circ. Res. 103, 1241–1248 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman A. F., Christoffels V. M. (2003). Cardiac chamber formation: development, genes, and evolution. Physiol. Rev. 83, 1223–1267 10.1152/physrev.00006.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D. B., Gray R. O., Grasser W. A., Pollard T. D. (1988). Direct demonstration of actin filament annealing in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 106, 1947–1954 10.1083/jcb.106.6.1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M., Sato Y., Uemura A., Narita Y., Tozaki–Saitoh H., Nakaya M., Ide T., Suzuki K., Inoue K., Nagao T.et al. (2008). P2Y6 receptor-Gα12/13 signalling in cardiomyocytes triggers pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. EMBO J. 27, 3104–3115 10.1038/emboj.2008.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishii K., Shibata Y. (2006). Mode and determination of the initial contraction stage in the mouse embryo heart. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.) 211, 95–100 10.1007/s00429-005-0065-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S. (2010). Dynamic regulation of sarcomeric actin filaments in striated muscle. Cytoskeleton 67, 677–692 10.1002/cm.20476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul A. S., Pollard T. D. (2009). Review of the mechanism of processive actin filament elongation by formins. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 66, 606–617 10.1002/cm.20379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard T. D. (2007). Regulation of actin filament assembly by Arp2/3 complex and formins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 36, 451–477 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger J. W., Kang S., Siebrands C. C., Freeman N., Du A., Wang J., Stout A. L., Sanger J. M. (2005). How to build a myofibril. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 26, 343–354 10.1007/s10974-005-9016-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmera D., Pexieder T., Vuillemin M., Thompson R. P., Anderson R. H. (2000). Developmental patterning of the myocardium. Anat. Rec. 258, 319–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima Y., Zubair M., Ishihara S., Shinohara Y., Oka S., Kimura S., Okamoto S., Minokoshi Y., Suita S., Morohashi K. (2005). Ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus-specific enhancer of Ad4BP/SF-1 gene. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 2812–2823 10.1210/me.2004-0431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skwarek–Maruszewska A., Hotulainen P., Mattila P. K., Lappalainen P. (2009). Contractility-dependent actin dynamics in cardiomyocyte sarcomeres. J. Cell Sci. 122, 2119–2126 10.1242/jcs.046805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taber L. A. (1998). Mechanical aspects of cardiac development. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 69, 237–255 10.1016/S0079-6107(98)00010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano K., Watanabe–Takano H., Suetsugu S., Kurita S., Tsujita K., Kimura S., Karatsu T., Takenawa T., Endo T. (2010). Nebulin and N-WASP cooperate to cause IGF-1-induced sarcomeric actin filament formation. Science 330, 1536–1540 10.1126/science.1197767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K., Takeya R., Suetsugu S., Kan–o M., Narusawa M., Shiose A., Tominaga R., Sumimoto H. (2009). Mammalian formin fhod3 regulates actin assembly and sarcomere organization in striated muscles. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29873–29881 10.1074/jbc.M109.059303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. A., Tsuchida M. A., Allen G. M., Barnhart E. L., Applegate K. T., Yam P. T., Ji L., Keren K., Danuser G., Theriot J. A. (2010). Myosin II contributes to cell-scale actin network treadmilling through network disassembly. Nature 465, 373–377 10.1038/nature08994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi T., Tokunaga T., Furuta Y., Nada S., Yoshida M., Tsukada T., Saga Y., Takeda N., Ikawa Y., Aizawa S. (1993). A novel ES cell line, TT2, with high germline-differentiating potency. Anal. Biochem. 214, 70–76 10.1006/abio.1993.1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.