Abstract

NAD(P)H:quinone reductase 1 (QR1) belongs to a class of enzymes called cytoprotective enzymes. It exhibits its cancer protective activity mainly by inhibiting the formation of intracellular semiquinone radicals, and by generating α-tocopherolhydroquinone, which acts as a free radical scavenger. It is therefore believed that QR1 inducers can act as cancer chemopreventive agents. Resveratrol (1) is a naturally occurring stilbene derivative that requires a concentration of 21 μM to double QR1 activity (CD = 21 μM). The stilbene double bond of resveratrol was replaced with a thiadiazole ring and the phenols were eliminated to provide a more potent and selective derivative 2 (CD = 2.1 μM). Optimizing the substitution pattern of the two phenyl rings and the central heterocyclic linker led to a highly potent and selective QR1 inducer 9o with a CD value of 0.087 μM.

Keywords: NAD(P)H:quinone reductase 1, QR1 inducer, chemoprevention, resveratrol

1. Introduction

The total economic burden of cancer extends from the direct medical costs to the indirect costs, which include losses of time and economic productivity resulting from cancer-related illness and death. The direct medical costs of cancer care have steadily increased over the past five decades, and were close to $103 billion in the United States in 2010, while the indirect costs were estimated to be $161 billion.1

Cancer chemoprevention is a strategy to chemically inhibit carcinogenesis. Similar to the familiar example of using aspirin to prevent coronary heart diseases,2 tamoxifen3–8 and finasteride9–27 are examples of drugs that have been employed as breast and prostate cancer chemopreventive agents, respectively. In addition, the success of several other clinical trials in preventing cancer in high-risk populations suggests that cancer chemoprevention is an effective strategy to decrease cancer mortality.28

Cancer chemoprevention can theoretically be achieved by terminating the effects of carcinogens by inhibiting or down-regulating enzymes such as aromatase and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) that are capable of generating carcinogenic species.29, 30 On the other hand, cancer chemoprevention could also be achieved by activating or up-regulating anticarcinogenic enzymes, which include electrophile-processing cytoprotective enzymes31 such as glutathione S-transferases, as well as superoxide dismutase and NAD(P)H:quinone reductase (QR1).32 This report focuses on QR1, which catalyzes the reduction of the vast majority of quinones (e.g., menadione) to their hydroquinone forms.33

Quinones are a class of compounds that have high cytotoxic activities associated with their abilities to readily undergo redox cycling, and from their capacity to react with and deplete cytoprotective nucleophiles containing sulfhydryl groups. Under oxidative stress conditions, quinones undergo a one-electron reduction process by NAD(P)H-cytochrome P450 reductase, cytochrome b5 reductase, or ubiquinone oxidoreductase resulting in toxic free radical semiquinones, which give rise to other oxygen free radical species such as superoxide radicals and peroxide radicals.34–37 QR1 protects cells from the cytotoxic effects of free radicals by several different mechanisms. First, this enzyme catalyzes the NAD(P)H-dependent two-electron reduction pathway of quinones to hydroquinones, which are stable structures that bypass the radical pathway to semiquinones. The hydroquinones may then be conjugated with other water-soluble endogenous ligands to be excreted safely.38 The second mechanism involves reduction of α-tocopherolquinone (TQ), which comes from oxidation of α-tocopherol,39 into its hydroquinone form (TQH2).40 TQH2 acts as a free radical scavenger. After radical attack, TQH2 oxidizes into the epoxyquinone form (TQE), which is reduced to the antioxidant form (TQH2) by QR1 (Scheme 1).41 Similarly, QR1 is also capable of regenerating the antioxidant form of coenzyme Q after it undergoes free radical attack.42 One of the most important and famous QR1 inducers is resveratrol (Figure 1), the natural stilbene derivative that occurs in various edible plants.43 One parameter that is used to

Scheme 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of reservatrol (1) and compounds 2 and 3. The two peripheral rings are arbitrarily denoted “A” and “B” in structure 3.

One of the most important and famous QR1 inducers is resveratrol (Figure 1), the natural stilbene derivative that occurs in various edible plants.43 One parameter that is used to compare the QR1 induction activities of different compounds is the CD value, which is the concentration that doubles QR1 activity. In terms of CD value, resveratrol is a weak QR1 inducer (CD = 21 μM, Figure 1). In addition, resveratrol is metabolized rapidly into inactive metabolites, and it modulates many other biological pathways.44 For these reasons, there is a need to investigate resveratrol derivatives that might show greater QR1-induction efficacy and selectivity.

This report describes recent efforts to develop resveratrol analogues as more potent and selective inducers of QR1. The resveratrol trans-stilbene double bond was previously replaced with a thiadiazole ring.45 This strategy afforded the lead compound 2 (Figure 1), which had good QR1 induction activity with a CD value 10 times lower than resveratrol.45 In addition to the QR1 induction activity, compound 2 also had weak activities as an aromatase inhibitor and as an inhibitor of NF-κB.45 Further chemical optimization of the lead compound 2 furnished 3,5-bis(2-fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-thiadiazole (3), which exhibits a higher QR1 induction ratio and lower CD value (IR 10.5; CD = 1.8 μM, Figure 1), and high target selectivity.45 This report details recent efforts to maximize the QR1 induction activity.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

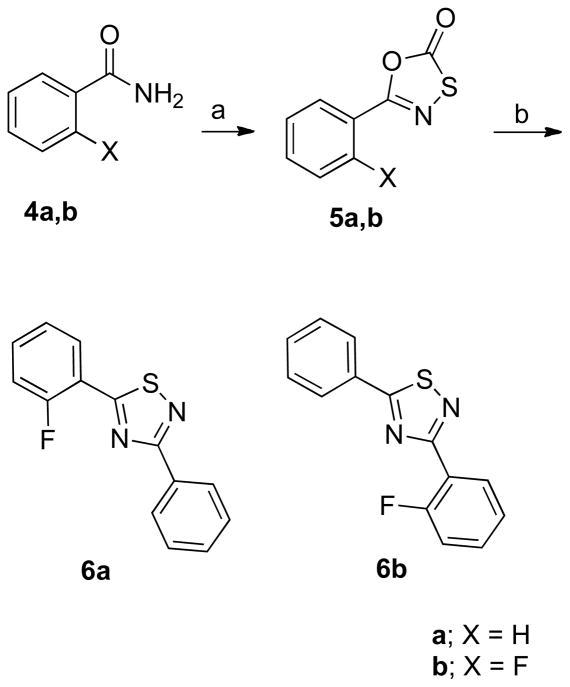

Although there are numerous methods reported for synthesis of 3,5-disubstituted-1,2,4-thiadiazoles with identical substituents,46–51 there are a limited number for preparation of those with non-identical substituents.52 In the present case, Howe’s method52 was followed, and oxathiazolones 5a,b, prepared from benzamides 4a,b and (chlorocarbonyl)sulfenyl chloride, were allowed to react with benzonitrile and its o-fluoro derivative in heated decaline to afford compounds 6a and 6b in low yields, respectively (Scheme 2). This reaction afforded many other by-products with close Rf values, so purifications of the desired compounds, especially 6a, were tedious and difficult.

Scheme 2a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (chlorocarbonyl)sulfenyl chloride, toluene, heat to reflux, 24 h, 76–100%; (b) benzonitrile or 2-fluorobenzonitrile, decaline, 200 °C, 20 min., 16–22%.

Following the reported procedure,53 appropriate thioamides 7a–w were allowed to react with bromoacetophenone 8a or 8b in dry DMF to afford the desired thiazoles 9a–w (Scheme 3 and 4).

Scheme 3a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) DMF, Cs2CO3, 100 °C, 8 h, 14 – 100 %.

Scheme 4a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) DMF, Cs2CO3, 100 °C, 8 h, 21 – 64 %.

The amide derivatives 11a and 11b were efficiently prepared from their corresponding aldehydes 10a and 10b using a method described by Chill and Mebane.54 Briefly, the aldehydes 10a and 10b were allowed to react with hydroxylamine hydrochloride in DMSO to form the corresponding oxime analogues. Aqueous sodium hydroxide solution (3 M) was added dropwise to the in situ-formed oximes, followed by careful and slow addition of hydrogen peroxide to afford the amides 11a and 11b in high yields. The obtained amides 11a and 11b were allowed to react with Lawesson’s reagent in dry THF to afford the corresponding thioamides 12a and 12b, which were treated with 3-methoxy-α-bromoacetophenone (8b) to afford thiazole derivatives 13a and 13b (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5a.

aReagents and conditions:a) i. H2NOH.HCl, DMSO, 100 °C, 20 min; ii. NaOH, H2O2, 1 min; b) Lawesson’s reagent, THF, 23 °C, 12 h; c) 3-methoxy-α-bromoacetophenone (8b), K2CO3, EtOH, 70 °C, 6 h, 33–35% overall yield.

2.2. Biological Results

First, the importance of the two fluorine atoms in compound 3 was tested to determine if they both have the same biological contribution or if only one of them is necessary for QR1 induction activity. Therefore, the monofluoro analogues 6a and 6b were prepared. Interestingly, it was found that the substitutions on both rings have different biological impacts. The “A” ring fluorine atom is more important and the monofuoro derivative 6a (IR = 11.6, and CD = 0.32 μM, Table 1) had a better QR1 induction ratio than the lead compounds 2 and 3 (Figure 1), and it was the first compound in this series that showed a sub-micromolar CD value. On the other hand, the fluorine atom at the ortho position of the “B” ring of 3 was not only unnecessary for QR1 induction activity, but was also found to have negative impact on QR1 induction. The “B” ring ortho-monofluorinated derivative 6b (IR = 8.04, and CD = 3.59 μM, Table 1) had a higher CD value than the unsubstituted lead compound 2 (IR = 8.63, and CD = 2.1 μM).

Table 1.

Induction of QR1 in wild type and mutant murine hepatoma cells.

| Compound | Hepa 1c1c7 | Hepa 1c1c7 | Taoc1 | BPrc1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| IRa | CDb,c (μM) | CDb,c (μM) | CDb,c (μM) | |

| Resveratrol (1) | 2.4 ± 0.53 | 21 ± 0.76 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 2 | 8.6 ± 0.72 | 2.1 ± 0.32 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 3 | 10.5 ± 0.38 | 1.8 ± 0.25 | 29.4 ± 1.3 | 27.2 ± 0.87 |

| 6a | 11.6 ± 0.64 | 0.32 ± 0.07 | 0.1 ± 0.04 | 1.6 ± 0.33 |

| 6b | 8.0 ± 0.49 | 3.59 ± 0.41 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9a | 0.7 ± 0.16 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9b | 5.1 ± 0.60 | 0.192 ± 0.05 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9c | 8.8 ± 0.52 | 0.36 ± 0.08 | 33.9 ± 0.94 | 35.7 ± 0.75 |

| 9d | 0.8 ± 0.47 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9e | 3.6 ± 0.53 | 0.143 ± 0.04 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9f | 7.3 ± 0.22 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9g | 2.8 ± 0.64 | 2.47 ± 0.17 | 5.9 ± 0.28 | 6.8 ± 0.46 |

| 9h | 7.3 ± 0.81 | 0.35 ± 0.08 | 5.6 ± 0.35 | 6.1 ± 0.30 |

| 9i | 2.1 ± 0.31 | 27.33 ± 0.89 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9j | 5.7 ± 0.14 | 0.39 ± 0.06 | 7.8 ± 0.73 | 9.2 ± 0.68 |

| 9k | 4.8 ± 0.55 | 0.39 ± 0.04 | 0.63 ± 0.09 | 2.4 ± 0.14 |

| 9l | 3.4 ± 0.41 | 9.61 ± 0.53 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9m | 0.57 ± 0.39 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9n | 5.0 ± 0.63 | 0.117 ± 0.05 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9o | 2.6 ± 0.71 | 0.087 ± 0.02 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9p | 0.73 ± 0.28 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9q | 0.70 ± 0.24 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9r | 6.1 ± 0.37 | 1.1 ± 0.44 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9s | 3.0 ± 0.46 | 1.98 ± 0.28 | 2.7 ± 0.11 | 12.6 ± 0.27 |

| 9t | 1.9 ± 0.40 | 20.3 ± 0.65 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9u | 3.1± 0.29 | 5.52 ± 0.46 | 13.4 ± 0.23 | 16.3 ± 0.51 |

| 9v | 1.1 ± 0.25 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 9w | 0.87 ± 0.17 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 13a | 0.65 ± 0.21 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 13b | 1.1 ± 0.19 | > 50 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 15 | 4.3 ± 0.48 | 0.98 ± 0.08 | > 50 | > 50 |

| 16 | 6.3 ± 0.36 | 4.03 ± 0.17 | > 50 | > 50 |

Induction Ratio.

CD is the concentration that doubles the activity.

CD values were determined for compounds with induction ratios > 2.

To systematically investigate the structure-activity-relationships of this new class of QR1 inducers, it was decided to modify the substitution(s) of one phenyl ring while the other one was kept unsubstituted. Inspired by the higher activity of “A” ring monofluorinated derivative 6a vs. the lower activity of its corresponding “B” ring monofluorinated analogue 6b, the “B” ring was chosen to be unsubstituted and the “A” ring was systemically optimized first. The “A” ring substituents were chosen mainly from the previously reported potent or moderately active thiadiazoles having identically substituted phenyl substituents.45

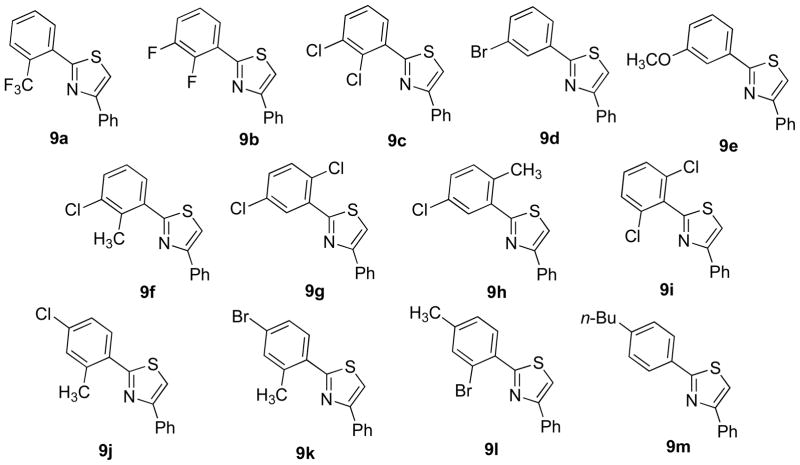

Originally, it was decided to perform the aforementioned chemical modifications using a thiadiazole central ring, but after the experience in preparation of compounds 6a and 6b, it was clear that preparation of thiadiazoles with two non-identical substituents in the required purity and quantities is difficult. In addition, it was previously established that using thiazole as a central ring preserved the chemopreventive activity.53 Therefore, the thiadiazole central ring was replaced with a thiazole ring and all subsequent modifications were performed using a 2,4-diaryl-1,3-thiazole scaffold. Use of this new scaffold provided higher accessibility and a more feasible chemical pathway to build a library of novel QR1 inducers. It was also decided to test the effect of the central ring later after optimizing the peripheral phenyl rings. Therefore, the thiazole derivatives 9a–m were prepared (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of thiazole derivatives 9a–m.

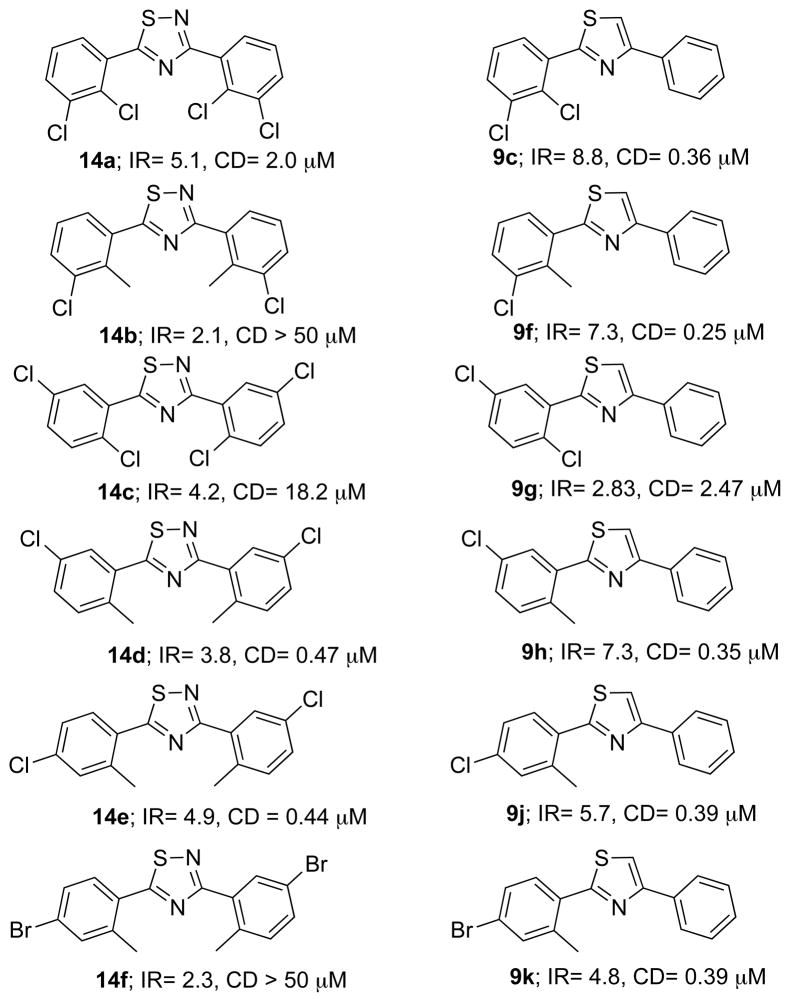

A variety of modifications of the most potent QR1 inducer 6a were tried in an attempt to further increase the activity. Replacement of the fluorine with a trifluoromethyl resulted in the inactive compound 9a (Table 1). Adding a second fluorine atom in the meta position of the “A” ring of 6a afforded the 2,3-difluoro derivative 9b (CD = 192 nM, Table 1), which has a CD value about half that of the monofluorinated analogue 6a and around one-hundred times less than the natural product resveratrol (1). Replacement of the fluorine atoms of 9b with two chlorines provided compound 9c, which has a higher CD value (CD = 360 nM; Table 1). Other derivatives 9d–m were chosen from the previously reported potent or moderately active thiadiazoles with identically substituted phenyl rings. Many of the “A” ring substituted 1,3-diarylthiazoles had better QR1 induction activities and lower CD values than their corresponding identically substituted 1,3-diarylthiadiazoles 14a–f as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the activities of thiadiazoles having identical substituents with thiazoles having different substituents.

The “B” ring was taken into consideration and it was intended to keep the “A” ring unsubsitituted and test the SAR of the “B” ring. The meta-methoxy derivative 9n was originally prepared to target NF-κB. Interestingly, compound 9n did not exhibit any inhibition of NF-κB induction. Instead, its QR1 induction activity was very promising with a lower CD value than all previously tested compounds (CD = 117 nM; Table 1).

The “A” ring of compound 9n was optimized based on the previously obtained results in an attempt to maximize synergy between different “A” and “B” ring substitutions. Therefore, compounds 9o–9w were prepared (Figure 4). An improvement in the QR1 induction activity was observed when both “A” and “B” rings were identically meta-methoxy substituted; the CD value of compound 9o is 87 nM (Table 1), which is 241 times better than that of resveratrol (1). All other derivatives are either weakly active or inactive as QR1 inducers (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of thiazole derivatives 9n–w.

The thiazole central ring of 9o was replaced with oxadiazole and thiadiazole to test the biological impact of altering the central ring. The oxadiazole analogue 15 (CD = 0.98 μM, Table 1) was found to be twelve times less active, in terms of CD value, as a QR1 inducer than its thiazole derivative 9o (CD = 87 nM), but it is still more active than resveratrol (1) and the lead compound 2 (CD = 2.1 μM). On the other hand, the thiadiazole derivative 16 exhibited a much higher CD value (CD = 4.03 μM, Table 1) than 9o.

Compounds 13a and 13b were designed to contain the active moieties in compounds 6a, 9e and 9n (Figure 5). The 1,2 and 1,4 correlations between the meta-methoxy and ortho-fluoro groups in the “A” ring were also considered. Surprisingly, both 13a and 13b were found to be inactive as QR1 inducers (Table 1). In this case, the sum is definitely less than the parts.

Figure 5.

Design of compounds 13a and 13b by compiling the active moieties in the “A” and “B” rings of compounds 6a, 9e and 9n.

QR1 and other enzymes that detoxify xenobiotics (such as glutathione S-transferase) are collectively known as phase II enzymes. Phase 1 enzymes (e.g., cytochrome P450s) include drug-metabolizing enzymes that may also metabolize procarcinogens to carcinogens, and enzyme induction may therefore be cancer-promoting. Inducers of drug-metabolizing enzymes may be classified as bifunctional, inducing both phase I and phase II enzymes, or monofunctional, affecting only the expression of beneficial phase II enzymes. In order to determine whether the compounds in this study were monofunctional, further QR1 assays were carried out in two mutant cell lines, Taoc1BPrc1 and BPrc1, which are defective in a functional aryl hydrocarbon (Ah) receptor or are unable to translocate the receptor–ligand complex to the nucleus, respectively. Compounds that induce QR1 in the Taoc1BPrc1 or BPrc1 mutants induce phase II enzymes and are monofunctional inducers, whereas the others are bifunctional inducers.

Of the compounds in this series, nine were found to be monofunctional. In comparing compounds 9a – 9m and 9n – 9w, there are several substituents that appear to result in monofunctionality. The dichlorinated compounds 9c and 9g were both active in the mutant cell lines, indicating that they induce only phase II enzymes. However, 9c was not a very potent inducer in mutant cells, with a CD of 33.9 μM in Taoc1BPrc1 cells, and the analogous methoxylated compound 9q did not display activity in the mutant cell lines. Compounds with a methoxy-substitution on the “B” ring are generally less active than their counterparts with unsubstituted “B” rings, mirroring the trend seen in wild type cells. For example, the 4-bromo-2-methyl-substituted compound 9k induces QR1 in Taoc1BPrc1 cells with a CD of 0.63 μM, while the similarly substituted 9s has a CD of 2.7 μM. The addition of a chlorine and a methyl group to ring “A” often results in a monofunctional compound (e.g., 9h, 9j, 9u), although this is not true of the 2,3-disubstituted compounds 9f and 9p. The three most active compounds in wild type cells (9e, 9n, and 9o) were not active in the mutant cell lines. Although monofunctional inducers are generally considered preferable because they do not activate potentially dangerous phase I enzymes, a number of bifunctional compounds, including 4′-bromoflavone and resveratrol, have displayed potent in vivo cancer chemopreventive activity.

To test the chemopreventive target selectivities of this set of thiazole derivatives, the top QR1 inducers (9e, 9n and 9o) and the reference compounds were also evaluated against other enzymes that are involved in chemopreventive pathways, such as aromatase, NF-κB, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). The results are summarized in Table 2. Compounds 9n and 9o showed weak NF-κB inhibitory activities (IC50’s = 31.6 and 20.3 μM, respectively), while 9e has low micromolar NF-κB inhibitory activity (Table 2). In addition, both 9e and 9n revealed weak inhibitory activity vs. iNOS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation of human aromatase inhibitory, NF-κB inhibitory, and antiinflammatory factivities.

| Compound | Aromatase | NF-κB-luciferase | Nitrite assay | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| % Inhibitiona | IC50b (μM) | % inhibitiona | IC50b (μM) | % inhibitiona | IC50b (μM) | |

| Resveratrol | 63.2 | 25.4 ± 2.1 | 79.0 ± 3.4 | 0.98 ± 0.16 | 86.1 ± 0.8 | 25.2 ± 2.0 |

| 2 | 60.2 | 32.7 ± 3.8 | 75.2 ± 2.6 | 47.7 ± 2.9 | 34.4 ± 2.3 | > 50 |

| 3 | 53.2 | > 50 | 40.7 ± 9.1 | > 50 | 12.9 ± 1.1 | > 50 |

| 9e | 35.5 | > 50 | 86.9 ± 12.0 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 49.5 ± 4.4 | > 50 |

| 9n | 27.1 | > 50 | 64.0 ± 0.98 | 31.6 ± 3.9 | 62.0 ± 2.5 | 45.3 ± 2.8 |

| 9o | 34.1 | > 50 | 62.3 ± 3.2 | 20.3 ± 2.6 | 33.9 ± 1.1 | > 50 |

Testing concentration, 50 μM of each compound.

IC50, median inhibitory concentration.

3. Conclusion

QR1 inducers protect cells from oxidative stress mainly by diverting quinone metabolism away from the free radical-generating one-electron reduction pathway to the twoelectron reduction pathway, which produces neutral hydroquinones. QR1 inducers can also generate α-tocopherolhydroquinone, which acts as a free radical scavenger. 3,5-Diphenyl-1,2,4-thiadiazole (2) provided a new scaffold for potent QR1 inducers. This new scaffold was derived from the natural product resveratrol by replacement of the ethylene linker with a fivemembered heterocycle. Starting from the lead compound 2, its difuoro derivative 3 has been obtained with a notable improvement in the QR1 induction activity (CD = 1.8 μM) in comparison with resveratrol (CD = 21 μM). Using thiazole as a central ring and optimizing substitutions on both “A” and “B” rings provided very potent QR1 inducers such as compounds 9o (CD = 0.087 μM), 9n (CD = 0.117 μM), and 9e (CD = 0.143 μM). 19

4. Experimental Section

4.1. General

All biologically tested compounds produced HPLC traces in which the major peak accounted for ≥ 95% of the combined total peak area when monitored by a UV detector at 254 nm. 1H NMR spectra were determined at 300 MHz and 13C NMR spectra were acquired at 75.46 MHz in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6). Chemical shifts are given in parts per million (ppm) on the delta (δ) scale and are related to that of the solvent. Mass spectra were recorded at 70 eV. High resolution mass spectra for all ionization techniques were obtained from a FinniganMAT XL95. Melting points were determined using capillary tubes with a Mel-Temp apparatus and are uncorrected. HPLC analyses were performed on a Waters binary HPLC system (Model 1525, 20 μL injection loop) equipped with a Waters dual wavelength absorbance UV detector (Model 2487) set for 254 nm, and using a 5 μm C-18 reverse phase column. Compounds 15,55 1646 and 14a–f45 were prepared as reported.

4.2. Preparation of Oxathiazolones 5a,b

Benzamide 4a,b (4 mmol) was added to (chlorocarbonyl)sulfenyl chloride (500 mg, 6 mmol) in toluene (30 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at reflux for 24 h. The solution was allowed to cool and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The brown solid was collected and crystallized from ethyl acetate to provide the required products as solids. Compound 5a was prepared as reported.56

4.3. 5-(2-Fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxathiazol-2-one (5b)

White solid (710 mg, 100%): mp 53 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.84 (dt, J = 1.5, 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.53 (m, 1 H), 7.18 (m, 1 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 167.08, 162.20, 154.00, 134.45, 130.08, 124.59, 117.32, 114.14; CIMS m/z (rel intensity) 198 (MH+, 100); HRMS (CI), m/z 196.9946 M+, calcd for C8H4FNO2S 196.9947; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 97.36% (methanol-H2O, 9:1).

4.4. Preparation of 1,2,4-Thiadiazoles 6a,b

Oxathiazolones 5a (1 mmol) or 5b (1 mmol) were added portionwise, over a 10 min time period, to a stirred solution of benzonitrile (515 mg, 5 mmol) or 2-fluorobenzonitrile (605 mg, 5 mmol) in decaline (5 mL) at 200 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for an additional 10–15 min, and then cooled to room temperature. The products were separated and purified by silica gel flash chromatography, using gradient hexane-ethyl acetate concentrations (95:5, 9:1, and then 4:1).

4.4.1. 5-(2-Fluorophenyl)-3-phenyl-1,2,4-thiadiazole (6a)

White solid (56 mg, 22%): mp 110 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.57 (dt J = 1.5, 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 8.42 (m, 2 H), 7.51 (m, 4 H), 7.36 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 180.28, 172.14, 162.91, 159.55, 133.12, 132.71, 130.30, 128.67, 128.26, 124.95, 116.11, 115.82; CIMS m/z (rel intensity) 257 (MH+, 100); HRMS (EI), m/z 256.0473 M+, calcd for C14H9FN2S 256.0471; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 95.34% (methanol-H2O, 9:1).

4.4.2. 3-(2-Fluorophenyl)-5-phenyl-1,2,4-thiadiazole (6b)

Yellowish-white solid (41 mg, 16%): mp 95 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.33 (dt, J = 1.5, 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 8.04 (m, 2 H), 7.52 (m, 4 H), 7.28 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 187.70, 170.00, 162.54, 159.14, 132.01, 131.79, 130.43, 129.28, 127.51, 124.18, 121.05, 116.97; CIMS m/z (rel intensity) 257 (MH+, 100); HRMS (EI), m/z 256.0469 M+, calcd for C14H9FN2S 256.0471; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 100.00% (methanol-H2O, 9:1).

4.5. General Procedure for 9a–w

Thioamide 7a–w (0.5 mmol), 2-bromoacetophenone 8a,b (0.5 mmol), and cesium carbonate (175 mg, 0.5 mmol) were added to dry DMF (2 mL). Each reaction mixture was heated to reflux for 8 h and then allowed to cool and quenched with distilled water (30 mL). The organic materials were extracted in a separatory funnel using ethyl acetate (30 mL). The organic layer was isolated and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The solid residue was purified by silica gel flash chromatography, using hexane-ethyl acetate (9:1), to yield the desired compounds. Compound 9o57 is reported.

4.5.1. 4-Phenyl-2-[2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]thiazole (9a)

Colorless oil (146 mg, 94%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.04 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 8.02 (s, 1 H), 7.85 (dd, J = 1.2, 8.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.73 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (m, 3 H), 7.49 (m, 2 H), 7.38 (m, 1 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 164.13, 155.90, 134.24, 132.77, 132.22, 131.73, 129.68, 128.81, 128.61, 128.31, 126.94, 126.88, 126.51, 114.59; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 306 (MH+, 100); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 306.0569, calcd for C16H11F3NS 306.0564; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 98.24% (methanol-H2O, 9:1).

4.5.2. 2-(2,3-Difluorophenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9b)

Yellowish-white solid (96 mg, 70%): mp 111–112 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.20 (m, 1 H), 8.02 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.00 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.62 (s, 1 H), 7.47 (m, 2 H), 7.40 (m, 1 H), 7.24 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 158.99, 155.27, 152.67, 150.27, 149.35, 146.84, 134.11, 128.78, 126.45, 124.33, 123.57, 117.96, 114.70; EIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 273 (M+, 100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 273.0428, calcd for C15H9F2NS 273.0424; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 97.94% (methanol-H2O, 9:1).

4.5.3. 2-(2,3-Dichlorophenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9c)

White solid (117 mg, 76%): mp 127 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.29 (dd, J = 1.5, 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 8.01(dd, J = 1.5, 8.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.65 (s, 1 H), 7.53 (dd, J = 1.5, 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.46 (m, 2 H), 7.36 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 162.64, 155.04, 134.14, 131.03, 129.37, 128.77, 128.32, 127.36, 126.43, 114.98; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 306/308 (MH+, 100/45); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 305.9908, calcd for C15H10Cl2NS 305.9911; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 98.07% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.4. 2-(3-Bromophenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9d)

White solid (22 mg, 14%): mp 80–81 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.23 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.00 (dd, J = 1.5, 6.0 Hz, 2 H), 7.80 (s, 1 H), 7.51-7.33 (m, 6 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 136.09, 134.73, 132.81, 130.67, 130.57, 130.38, 129.34, 128.75, 128.32, 126.41, 125.13, 113.13; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 318/316 (MH+, 100/99); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 315.9801, calcd for C15H11BrNS 315.9796; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 95.11% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.5. 2-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9e)

Colorless oil (112 mg, 84%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.07 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 8.04 (s, 1 H), 7.70 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.64 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.52-7.36 (m, 5 H), 7.02 (dd, J = 2.4, 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.91 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 167.68, 160.01, 156.17, 135.02, 134.50, 130.00, 128.78, 128.21, 126.49, 119.22, 116.11, 112.82, 111.48, 55.42; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 268 (MH+, 100); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 268.0798, calcd for C16H14NOS 268.0796; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 100% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.6. 2-(3-Chloro-2-methylphenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9f)

Colorless oil (143 mg, 100%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.04 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.01 (d, J = 0.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.55 (s, 1 H), 7.50 (m, 3 H), 7.40 (m, 1 H), 7.24 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 2.73 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 166.77, 155.79, 136.18, 135.09, 134.36, 130.42, 128.83, 128.29, 126.68, 126.45, 113.78, 17.86; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 286/288 (MH+, 100/25); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 286.0455, calcd for C16H13ClNS 286.0457; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 98.34% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.7. 2-(2,5-Dichlorophenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9g)

White solid (51 mg, 31%): mp 86 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.45 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 8.02 (dd, J = 1.5, 8.7 Hz, 2 H), 7.66 (s, 1 H), 7.64 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.49-7.26 (m, 4 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 161.54, 155.05, 134.07, 133.44, 133.11, 131.73, 131.12, 130.41, 130.05, 128.79, 128.37, 126.45, 115.10; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 306/308 (MH+, 100/57); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 305.9906, calcd for C15H10Cl2NS 305.9911; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 95.19% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.8. 2-(5-Chloro-2-methylphenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9h)

Colorless oil (40 mg, 28%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.00 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.85 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.56 (s, 1 H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.29 (m, 2 H), 2.65 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 165.81, 155.79, 135.01, 134.31, 132.86, 131.67, 129.42, 129.20, 128.78, 128.26, 126.39, 113.53, 21.27; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 286/288 (MH+, 100/41); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 286.0464, calcd for C16H13ClNS 286.0457; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 96.93% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.9. 2-(2,6-Dichlorophenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9i)

White solid (118 mg, 72%): mp 85–86 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.97 (dd, J = 1.5, 8.7 Hz, 1 H), 7.69 (s, 1 H), 7.45-7.28 (m, 6 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 161.20, 155.80, 136.01, 134.15, 132.32, 131.21, 128.75, 128.25, 128.21, 126.53, 115.14; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 306/308 (MH+, 100/58); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 305.9901, calcd for C15H10Cl2NS 305.9911; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 97.40% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.10. 2-(4-Chloro-2-methylphenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9j)

White solid (25 mg, 17%): mp 57 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.00 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.97 (s, 1 H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.54 (s, 1 H), 7.45 (dt, J = 1.2, 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 7.33 (m, 3 H), 2.68 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 166.24, 155.78, 138.49, 135.07, 134.36, 131.39, 130.49, 128.75, 128.19, 126.73, 126.35, 126.21, 113.17, 21.65; CIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 286/288 (MH+, 100/30); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 285.0383, calcd for C16H12ClNS 285.0379; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 99.30% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.11. 2-(4-Bromo-2-methylphenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9k)

White solid (160 mg, 97%): mp 58 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.02 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.99 (s, 1 H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.52 (s, 1 H), 7.50-7.39 (m, 5 H), 2.69 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 166.33, 155.79, 138.73, 134.39, 131.85, 131.18, 129.22, 128.81, 128.24, 126.40, 123.53, 113.26, 21.74; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 330/332 (MH+, 100/97); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 329.9956, calcd for C16H13BrNS 329.9952; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 100.00% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.12. 2-(2-Bromo-4-methylphenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9l)

White solid (136 mg, 82%): mp 92 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.13 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 8.50 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.02 (s, 1 H), 7.58 (s, 1 H), 7.55 (s, 1 H), 7.48 (dt, J = 1.5, 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 7.39 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.22 (dd, J = 1.0, 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 2.37 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 164.77, 154.92, 141.11, 134.48, 131.41, 128.77, 128.50, 128.16, 126.48, 121.33, 114.21, 20.91; CIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 330/332 (MH+, 100/98); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 328.9876, calcd for C16H12BrNS 328.9874; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 100.00% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.13. 2-(4-n-Butylphenyl)-4-phenylthiazole (9m)

White solid (101 mg, 68%): mp 47 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.09 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.06 (s, 1 H), 8.03 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 7.51 (dt, J = 1.5, 8.7 Hz, 2 H), 7.44 (s, 1 H), 7.42 (m, 1 H), 7.32 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.71 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.69 (m, 2 H), 1.44 (m, 2 H), 1.02 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 168.07, 156.11, 145.28, 134.65, 131.38, 129.00, 128.76, 128.12, 126.59, 126.50, 112.26, 35.59, 33.48, 22.40, 14.05; CIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 294 (MH+, 100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 293.1241, calcd for C19H19NS 293.1238; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 95.04% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.14. 4-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-2-phenylthiazole (9n)

White solid (134 mg, 100%): mp 79–80 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 8.07 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.66 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.49-7.39 (m, 5 H), 7.01 (dd, J = 2.4, 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.91 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 167.75, 160.00, 156.05, 135.88, 133.72, 130.08, 129.77, 128.93, 126.62, 118.88, 113.90, 113.02, 112.02, 55.33; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 268 (MH+, 100); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 268.0799, calcd for C16H14NOS 268.0796; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 99.99% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.15. 2-(3-Chloro-2-methylphenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (9p)

White solid (35 mg, 21%): mp 70 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.56 (m, 4 H), 7.48 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.23 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 6.92 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.89 (s, 3 H), 2.68 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 166.66, 159.98, 155.59, 136.12, 135.68, 135.05, 130.40, 129.79, 128.75, 126.62, 118.79, 114.02, 113.94, 111.93, 55.31, 17.76; CIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 318/316 (MH+, 33/100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 315.0485, calcd for C17H14ClNOS 315.0480; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 95.62% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.16. 2-(2,3-Dichlorophenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (9q)

White solid (82 mg, 48%): mp 93 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.29 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.64 (s, 1 H), 7.59 (dd, J = 3.9, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.54 (s, 1 H), 7.52 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.92 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.89 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 162.52, 159.97, 154.81, 135.49, 134.13, 134.02, 131.02, 130.37, 129.79, 129.36, 127.34, 118.84, 115.30, 113.91, 112.03, 55.33; CIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 338/336 (MH+, 67/100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 334.9938, calcd for C16H11Cl2NOS 334.9946; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 95.00% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.17. 2-(2,3-Difluorophenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (9r)

White solid (88 mg, 58%): mp 98 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.20 (m, 1 H), 7.62 (s, 1 H), 7.60 (m, 1 H), 7.56 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.22 (m, 2 H), 6.93 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.90 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 159.98, 158.90, 155.06, 152.45, 149.15, 135.45, 129.78, 124.30, 118.84, 117.96, 114.99, 113.91, 112.06, 55.30; CIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 304 (MH+, 100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 303.0533, calcd for C16H11F2NOS 303.0529; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 96.02% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.18. 2-(4-Bromo-2-methylphenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (9s)

Colorless oil (89 mg, 49%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.67 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.58 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.50 (m, 3 H), 7.42 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.92 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.89 (s, 3 H), 2.67 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 166.24, 159.95, 155.59, 138.72, 135.72, 134.35, 131.82, 131.18, 129.79, 129.19, 123.51, 118.77, 113.77, 113.56, 112.03, 55.31, 21.66; EIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 362/360 (MH+, 98/100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 358.9979, calcd for C17H14BrNOS 358.9982; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 97.48% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.19. 2-(2-Bromo-4-methylphenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (9t)

White solid (53 mg, 31%): mp 53 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.10 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.61-7.54 (m, 4 H), 7.36 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 6.92 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.89 (s, 3 H), 2.38 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 164.69, 159.95, 154.74, 141.11, 135.77, 134.45, 131.39, 131.27, 129.74, 128.45, 121.29, 118.85, 114.46, 113.83, 111.96, 55.33, 20.87; EIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 362/360 (MH+, 96/100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 358.9980, calcd for C17H14BrNOS 358.9982; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 98.18% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.20. 2-(5-Chloro-2-methylphenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (9u)

Pale yellow oil (89 mg, 57%). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.85 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (m, 2 H), 7.55 (s, 1 H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.29 (m, 2 H), 6.93 (dd, J = 7.8, 2.1 Hz, 1 H), 3.89 (s, 3 H), 2.65 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 165.70, 159.98, 155.57, 135.66, 135.00, 134.27, 132.89, 131.67, 129.80, 129.39, 129.21, 118.80, 113.87, 113.83, 112.04, 55.31, 21.30; CIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 318/316 (MH+, 27/100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 315.0485, calcd for C17H14ClNOS 315.0480; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 99.94% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.21. 2-(4-n-Butylphenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (9v)

White solid (104 mg, 64%): mp 74 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.00 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.66 (dd, J = 4.9, 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.61 (dd, J = 7.8, 0.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.44 (s, 1 H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2 H), 6.95 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 2.69 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2 H), 1.66 (m, 2 H), 1.42 (m, 2 H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 167.96, 159.98, 155.90, 145.28, 135.98, 131.32, 129.74, 128.97, 126.56, 118.87, 113.82, 112.55, 112.00, 55.31, 35.56, 33.45, 22.37, 14.01; EIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 323 (M+, 100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 323.1347, calcd for C20H21NOS 323.1344; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 99.40% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.5.22. 2-(3-Bromophenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (9w)

Solid (110 mg, 64%): mp 87 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.23 (s, 1 H), 7.90 (dd, J = 7.2, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 7.59 (m, 1 H), 7.54 (m, 2 H), 7.44 (s, 1 H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.28 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 6.93 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1 H), 3.89 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 165.76, 159.98, 156.22, 135.54, 135.46, 132.81, 130.39, 129.80, 129.28, 125.15, 123.07, 118.85, 113.94, 113.53, 112.06, 55.36; ESIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 348/346 (MH+, 100/97); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 345.9902, calcd for C16H13BrNOS 345.9902; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 97.53% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.6. Preparation of 13a and 13b

The aldehydes 10a or 10b (800 mg, 5.2 mmol) were added to a solution of hydroxylamine hydrochloride (725 mg, 10.5 mmol) in DMSO (10 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 20 min. The heater was turned off and an aqueous solution of NaOH (600 mg) in H2O (5 mL) was slowly added to the reaction mixture over a 2 min period with stirring, and then 50% hydrogen peroxide (5 mL) was slowly and carefully added over a 10 min period. The reaction mixture was further stirred for 5 min and extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL), dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and evaporated under reduced pressure to afford the corresponding amides 11a and 11b58 as white solids. The crude amides 11a or 11b (1 mmol) and Lawesson’s reagent (490 mg, 1.2 mmol) were added to dry THF (15 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue was partitioned between aq NaHCO3 (25 mL) and ethyl acetate (25 mL). The organic solvent was separated and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The crude product was further purified by silica gel flash chromatography, using hexane-ethyl acetate (4:1), to yield the corresponding thioamides 12a and 12b as yellow solids. The obtained thioamides 12a or 12b (90 mg, 0.5 mmol), 3-methoxy-α-bromoacetophenone 8b (115 mg, 0.5 mmol), and potassium carbonate (175 mg, 0.5 mmol) were added to absolute ethanol (5 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at 70 °C for 6 h and then allowed to cool and quenched with distilled water (30 mL). The organic materials were extracted by ethyl acetate (30 mL). The organic layer was isolated and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. Solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The solid residue was purified by silica gel flash chromatography, using hexane-ethyl acetate (9:1, then 4:1), to yield the desired compounds as solids.

4.6.1. 2-(2-Fluoro-3-methoxyphenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (13a)

Yellowish solid (48 mg, 32%): mp 94 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 8.01 (dt, J = 1.5, 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.62 (s, 1 H), 7.60 (s, 1 H), 7.56 (dd, J = 0.6, 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.36 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1 H), 7.19 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 7.01 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1 H), 6.92 (dd, J = 2.4, 8.7 Hz, 1 H), 3.93 (s, 3 H), 3.85 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 159.95, 154.78, 151.99, 148.19, 135.70, 129.74, 124.12, 122.19, 119.95, 118.85, 114.69, 113.97, 111.98; 56.42, 55.31; CIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 316 (MH+, 100); HRMS (ESI), m/z MH+ 316.0807, calcd for C17H15FNO2S 316.0808; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 99.07% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.6.2. 2-(2-Fluoro-5-methoxyphenyl)-4-(3-methoxyphenyl)thiazole (13b)

White solid (53 mg, 35%): mp 76 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.95 (dd, J = 3.3, 6.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.62 (t, J = 1.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.61 (s, 1 H), 7.57 (s, 1 H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.09 (dd, J = 0.9, 9.0 Hz, 1 H), 6.93-6.89 (m, 2 H), 3.88 (s, 3 H), 3.87 (s, 3 H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 159.95, 156.31, 155.82, 154.68, 153.08, 135.66, 129.74, 121.70, 118.88, 117.12, 114.76, 114.63, 113.63, 112.17, 111.99; EIMS (m/z, rel intensity) 315 (M+, 100); HRMS (EI), m/z M+ 315.0731, calcd for C17H14FNO2S 315.0729; HPLC purity (C-18 reverse phase column): 95.02% (methanol-H2O, 95:5).

4.7. Quinone Reductase 1 (QR1) Assay

QR1 activity was assayed using Hepa 1c1c7 murine hepatoma cells as previously described.59 Briefly, cells were incubated in a 96-well plate with test compounds at a maximum concentration of 50 μM for 48 hours prior to permeabilization with digitonin. Enzyme activity was then determined as a function of the NADPH-dependent menadiol-mediated reduction of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazo-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) to a blue formazan. Production was measured by absorption at 595 nm. A total protein assay using crystal violet staining was run in parallel. Data presented are the result of three independent experiments run in duplicate. 4′-Bromoflavone (CD = 0.01 μM) was used as a positive control.

4.8. Aromatase Assay

Aromatase activity was assayed as previously reported, with the necessary modifications to assay in a 384-well plate.60 Briefly, the test compound (3.5 μL) was preincubated with 30 μL of NADPH-regenerating system (2.6 mM NADP+, 7.6 mM glucose 6-phosphate, 0.8 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 13.9 mM MgCl2, and 1 mg/mL albumin in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for 10 min at 37 °C. The enzyme and substrate mixture (33 μL of 1 μM CYP19 enzyme, BD Biosciences, 0.4 μM dibenzylfluorescein, 4 mg/mL albumin in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4) was added, and the plate was incubated for 30 min at 37 °C before quenching with 25 μL of 2 N NaOH. After termination of the reaction and shaking for 5 min, the plate was further incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. This enhances the ratio of signal to background. Fluorescence was measured at 485 nm (excitation) and 530 nm (emission). IC50 values were based on three independent experiments performed in duplicate using five concentrations of test substance. Naringenin (IC50 = 0.23 μM) was used as a positive control.

4.9. NF-κB Luciferase Assay

Studies were performed with NF-κB reporter stablytransfected human embryonic kidney cells 293 from Panomics (Fremont, CA). This cell line contains chromosomal integration of a luciferase reporter construct regulated by NF-κB response element. The gene product, luciferase enzyme, reacts with luciferase substrate, emitting light, which is detected with a luminometer. Data were expressed as % inhibition at 50 μM or IC50 values (i.e., concentration of test sample required to inhibit TNF-α activated NF-κB activity by 50%). After incubating treated cells, they were lysed in Reporter Lysis buffer. The luciferase assay was performed using the Luc assay system from Promega, following the manufacturer’s instructions. In this assay, Nα-tosyl-L-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) was used as a positive control; IC50 = 5.09 μM.

4.10. Nitrite Assay

RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage cells were incubated in a 96-well culture plate for 24 h. The cells were pretreated with various concentrations of compounds dissolved in phenol red-free DMEM for 30 min followed by 1 μg/mL of LPS treatment for 24 h. The level of nitrite, a stable end product of NO, in the cultured media was measured using a colorimetric reaction with Griess reagent. The optical density (OD) was measured at 540 nm and the level of nitrite was estimated using a standard curve with known concentrations of sodium nitrite. The positive control in this assay was NG-L-monomethyl arginine (L-NMMA); IC50 = 19.7 μM.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Program Project Grant P01 CA48112 awarded by the National Cancer Institute.

Abbreviations

- CD

concentration that doubles QR1 activity

- IC50

sample concentration that causes 50% inhibition

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IR

induction ratio

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- QR1

NAD(P)H:quinone reductase 1

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2010. Atlanta, Ga: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catellalawson F, Fitzgerald GA. Drug Saf. 1995;13:69–75. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199513020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1504–1504. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.19.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher B, Costantino JP. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1891A–1892. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.21.1891a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Love RR. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1891–1892. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.21.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powles TJ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:730–730. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.8.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narod S. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:188–188. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin WM, Vogel V, Robidoux A, Dimitrov N, Atkins J, Daly M, Wieand S, Tan-Chiu E, Ford L, Wolmark N. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parnes HL, Thompson IM, Ford LG. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:368–377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellon JK. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2016–2022. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitts WR., Jr Eur Urol. 2003;44:650–655. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Eur Urol. 2004;46:133–134. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddy GK. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;2:206–208. doi: 10.1016/s1540-0352(11)70045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barzell WE. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1569–1572. author reply 1569–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke HB. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1569–72. author reply 1569–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Amico AV, Barry MJ. J Urol. 2006;176:2010–2012. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.045. discussion 2012–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etzioni RD, Howlader N, Shaw PA, Ankerst DP, Penson DF, Goodman PJ, Thompson IM. J Urol. 2005;174:877–881. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000169255.64518.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton RJ, Kahwati LC, Kinsinger LS. Cancer Epidemiol, Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2164–2171. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee SC, Ellis RJ. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1569–1572. author reply 1569–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucia MS, Epstein JI, Goodman PJ, Darke AK, Reuter VE, Civantos F, Tangen CM, Parnes HL, Lippman SM, La Rosa FG, Kattan MW, Crawford ED, Ford LG, Coltman CA, Jr, Thompson IM. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1375–1383. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roehrborn CG. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1569–1572. author reply 1569–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross RK, Skinner E, Cote RJ. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1569–1572. author reply 1569–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin MA, Kantoff PW. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1569–1572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200310163491615. author reply 1569–1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz DT. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1569–1572. author reply 1569–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson IM, Klein EA, Lippman SM, Coltman CA, Djavan B. Eur Urol. 2003;44:650–655. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson IM, Pauler Ankerst D, Chi C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lippman SM, Lucia MS, Parnes HL, Coltman CA., Jr J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3076–3081. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.6836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Parnes HL, Lippman SM, Coltman CA., Jr Urology. 2008;71:854–857. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh PC. J Urol. 2006;176:409–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00585-4. author reply 410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsao AS, Kim ES, Hong WK. Ca-Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:150–180. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.3.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conda-Sheridan M, Marler L, Park EJ, Kondratyuk TP, Jermihov K, Mesecar AD, Pezzuto JM, Asolkar RN, Fenical W, Cushman M. J Med Chem. 2010;53:8688–8699. doi: 10.1021/jm1011066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:1397–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prochaska HJ, Talalay P. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4776–4782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross D, Kepa JK, Winski SL, Beall HD, Anwar A, Siegel D. Chem-Biol Interact. 2000;129:77–97. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Talalay P, Prochaska HJ. Chem Scripta. 1987;27A:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ernster L. Oxid Damage & Repair. 1991:633–635. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lind C, Cadenas E, Hochstein P, Ernster L. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:287–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86122-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lind C, Hochstein P, Ernster L. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982;216:178–185. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lind C, Vadi H, Ernster L. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;190:97–108. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li R, Bianchet MA, Talalay P, Amzel LM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:8846–8850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Csallany AS, Draper HH, Shah SN. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1962;98:142–145. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(62)90159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siegel D, Bolton EM, Burr JA, Liebler DC, Ross D. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:300–305. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liebler DC, Burr JA. Lipids. 2000;35:1045–1047. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beyer RE, SeguraAguilar J, DiBernardo S, Cavazzoni M, Fato R, Fiorentini D, Galli MC, Setti M, Landi L, Lenaz G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2528–2532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang MS, Cai EN, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CWW, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR, Kinghorn AD, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Science. 1997;275:218–220. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoshino J, Park EJ, Kondratyuk TP, Marler L, Pezzuto JM, van Breemen RB, Mo SY, Li YC, Cushman M. J Med Chem. 2010;53:5033–5043. doi: 10.1021/jm100274c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayhoub AS, Marler L, Kondratyuk TP, Park E-J, Pezzuto JM, Cushman M. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:510–520. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayhoub AS, Kiselev E, Cushman M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:4941–4943. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.07.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shah AU, Khan ZA, Choudhary N, Loholter C, Schafer S, Marie GP, Farooq U, Witulski B, Wirth T. Org Lett. 2009;11:3578–3581. doi: 10.1021/ol9014688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng DP, Chen ZC. Synth Commun. 2002;32:2155–2159. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan M, Chen ZC, Zheng QG. J Chem Res Synop. 2003:618–619. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akamanchi KG, Patil PC, Bhalerao DS, Dangate PS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:5820–5822. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Isobe T, Ishikawa T. J Org Chem. 1999;64:6989–6992. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howe RK, Shelton BR. J Org Chem. 1981;46:771–775. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayhoub AS, Marler L, Kondratyuk T, Park E, Pezzuto J, Cushman M. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:2427–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mebane RC, Chill ST. Synth Commun. 2010;40:2014–2017. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lagrenee M, Outirite M, Lebrini M, Bentiss F. J Heterocycl Chem. 2007;44:1529–1531. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friedrich B, Josef G. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem. 1969;726:110–113. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bey E, Marchais-Oberwinkler S, Werth R, Al-Soud YA, Kruchten P, Oster A, Frotscher M, Birk B, Hartmann RW. J Med Chem. 2008;51:6725–6739. doi: 10.1021/jm8006917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Czaplewski LG, Collins I, Boyd EA, Brown D, East SP, Gardiner M, Fletcher R, Haydon DJ, Henstock V, Ingram P, Jones C, Noula C, Kennison L, Rockley C, Rose V, Thomaides-Brears HB, Ure R, Whittaker M, Stokes NR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:524–527. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gerhauser C, You M, Liu J, Moriarty RM, Hawthorne M, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Cancer Res. 1997;57:272–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maiti A, Cuendet M, Croy VL, Endringer DC, Pezzuto JM, Cushman M. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2799–2806. doi: 10.1021/jm070109i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]