Abstract

Hemangioma stem cells (HemSCs) are multipotent cells isolated from infantile hemangioma (IH), which form hemangioma-like lesions when injected subcutaneously into immune-deficient mice. In this murine model, HemSCs are the primary target of corticosteroid, a mainstay therapy for problematic IH. The relationship between HemSCs and endothelial cells that reside in IH is not clearly understood. Adhesive interactions might be critical for the preferential accumulation of HemSCs and/or endothelial cells in the tumor. Therefore, we studied the interactions between HemSCs and endothelial cells (HemECs) isolated from IH surgical specimens. We found that HemECs isolated from proliferating phase IH, but not involuting phase, constitutively express E-selectin, a cell adhesion molecule not present in quiescent endothelial cells. E-selectin was further increased when HemECs were exposed to vascular endothelial growth factor–A or tumor necrosis factor–α. In vitro, HemSC migration and adhesion was enhanced by recombinant E-selectin but not P-selectin; both processes were neutralized by E-selectin–blocking antibodies. E-selectin–positive HemECs also stimulated migration and adhesion of HemSCs. In vivo, neutralizing antibodies to E-selectin strongly inhibited formation of blood vessels when HemSCs and HemECs were co-implanted in Matrigel. These data suggest that endothelial E-selectin could be a major ligand for HemSCs and thereby promote cellular interactions and vasculogenesis in IH. We propose that constitutively expressed E-selectin on endothelial cells in the proliferating phase is one mediator of the stem cell tropism in IH.

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common tumor of infancy. A hallmark is its unique life cycle of rapid development in childhood, followed by a slow regression and cessation of growth.1 Hemangioma endothelial cells (HemECs) in proliferating lesions show X chromosome inactivation patterns, indicative of a clonal origin,2–4 that is maintained in cultured HemECs.2 In comparison to human dermal microvascular endothelial cell (HDMEC), HemECs have constitutively active vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor 2 (VEGFR2) signaling in association with low expression of vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor 1 (VEGFR1/FLT1).5 HemECs have a placental microvascular phenotype and may originate from placental endothelial cells.6,7 Little is known about endothelial cells in the involuting phase of IH.8

Proliferating hemangiomas express high levels of hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) protein and release factors9 that can induce recruitment of bone marrow–derived cells from the circulation into the tumors. These cells could be heterogeneous, composed of endothelial progenitor cells,9,10 myeloid cells,11 and possibly CD133-positive cells that include hemangioma stem cells (HemSCs). HemSCs isolated from specimens of human proliferating IH are multipotent, and exhibit a mesenchymal morphology and robust proliferation in vitro.12 In contrast to HemECs, HemSCs can form human blood vessels with the immunophenotype and dynamics of IH when injected subcutaneously into nude mice.12 A central function of HemSCs in IH is supported by our recent study in which we showed that corticosteroid act specifically on the HemSCs to down-regulate vascular endothelial growth factor–A (VEGF-A) expression.13 However, it is undetermined whether HemSCs arise in the tumors or whether they are recruited to tumor site in response to pathological endothelial cells in a specific microenvironment.

E-selectin has been detected in proliferating phase specimens of IH and has been shown to decrease in involuting phase specimens.14,15 Here, we analyzed E-selectin expression in endothelial cells expanded from proliferating and involuting IH tumors, and its potential role in functional interactions between HemSCs and ECs. Our findings implicate E-selectin in hemangioma blood vessel development, and suggest that E-selectin on HemECs may engage stem cells in vasculogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Isolation, Culture, and Reagents

Specimens of IH were obtained under a human subject protocol approved by the Committee on Clinical Investigation, Boston Children's Hospital. The clinical diagnosis was confirmed in the Department of Pathology at Boston Children's Hospital. Informed consent was obtained for the specimens, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Single cell suspensions were prepared from the proliferating and involuting phase specimens to isolate HemECs and during proliferating phase to isolate HemSCs. Clinical data on the IH patients are provided in Table 1. HemECs and HemSCs were purified and expanded as described.12,13,16–18 Three different proliferating hemangioma tumors and three different involuting hemangioma tumors were used to isolate the HemECs. HemECs were used between passage 2 and 8. Experiments using HemSCs were confirmed with three different HemSCs from different hemangioma patients (Hem129, 133 and 150). The HemSCs were used between passages 4 and 12. Human endothelial colony forming cells (ECFC) from umbilical cord blood were isolated as previously described.19–22 To test the effect of VEGF and TNF-α on E-selectin levels in HemEC-P, cells were cultured for 16 hours in serum and growth factor free EBM-2 medium, followed by a 4-hour treatment with either 50 ng/mL of human recombinant VEGF-A165 or 10 ng/mL recombinant human tumor necrosis factor–α (rhTNF-α; both from R&D Systems).

Table 1.

Clinical Data for Patient Infantile Hemangioma Samples Used to Isolate HemEC-P and HemEC-I

| Hemangioma no. | Sex | Age | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferating | 131 | Female | 2 months | Eyelid |

| 133 | Female | 10 months | Forehead | |

| 150 | Male | 3 months | Occipital | |

| Involuting | 69 | Female | 1 year | Chest |

| 70 | Female | 2 years | Scalp | |

| 74 | Male | 3 years | Eyelid |

Hemangioma numbers are case identifiers.

Assays for in Vitro Cellular Proliferation and Viability

Proliferation was assessed after seeding 104 cells on fibronectin-coated 24-well plates and culturing in growth medium [Endothelial Basal Cell Medium (EBM), SingleQuot Kit (Lonza, Allendale, NJ) without hydrocortisone, supplemented to 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS)]. Cell numbers at days 2, 3, 4, and 6 were determined by counting with a phase-contrast microscope and disposable hemocytometer (Digital Bio, Seoul, Korea). HemECs proliferation was also determined by measuring cellular phosphatase activity, based on the release of para-nitrophenol (pNPP; Sigma) measured at OD 405 nm after 2, 3, or 4 days of growth.

In Vivo Model of Infantile Hemangioma and Microvessel Density

Experiments were performed with 3 × 106 total cells per implant as previously described.13,18 HemECs (1.5 × 106) were combined with HemSCs (1.5 × 106). Cells were suspended in 200 μl of Matrigel (reference 356237; BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA) and injected subcutaneously on the back of 6- to 7-week-old male athymic nu/nu mice (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA). For the assessment of microvessel density, four fields from mid-Matrigel H&E-stained sections of each of the animals in the group were quantified by counting luminal structures containing red blood cells. MVD was expressed as vessels/mm2.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were labeled with PE-conjugated murine anti–human E-selectin (BD Bioscience) or PE-conjugated isotype-matched control murine IgG (BD Bioscience). Flow cytometry was performed on a BD FACScan. Data were analyzed using FlowJo software version 8.7.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA synthesis was performed with iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). All reactions were performed for 35 cycles with the following temperature profiles: 95°C for 2 minutes (initiation; 30 seconds per cycle thereafter), an annealing step for 25 seconds, and an extension step at 72°C for 30 seconds. Primer sequences are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers Used for Quantitative Real-Time PCR

| Primer | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| VE-cadherin | 5′-CCTTGGGTCCTGAAGTGACCT-3′ | 5′-CAGGGCCTTCCTTCTGCAA-3′ |

| VWF | 5′-GCCTGCCATCTGCCTGTGA-3′ | 5′-CCACTGGGAGCCGACACTCT-3′ |

| E-selectin | 5′-CACATCTCAGGGACAATGGACAGA-3′ | 5′-GCTTGAACATTTTACCACTTGGCA-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG-3′ | 5′-GATGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′ |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; VWF, von Willebrand factor; VE-cadherin, vascular endothelial-cadherin.

Assay for Tube Formation in Vitro

Forty-eight-well-plates were coated with growth factor–reduced Matrigel (reference 356231;BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA) and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. HemECs were seeded at a density of 3 × 104 cells in 500 μl of EBM2/0.1% FBS. After 18 hours, pictures were taken with an inverted microscope Nikon Eclipse TE300 (Nikon, Melville, NY) using SPOT Advanced 3.5.9 software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Adhesion Assay

Adhesion assays were performed in 96-well polystyrene plates coated with BSA 0.1% with or without recombinant human E-selectin. Cells (1 × 104) were plated on the coated dishes. After a 20-minute incubation, nonadherent cells were washed off, and the number of adherent cells determined in an alkaline phosphatase assay using the substrate pNPP. Each data point was determined by the average of three wells, and each experiment was performed at least three times. For inhibition experiments, anti–human E-selectin or anti–human P-selectin was added at 10 μg/mL 2 hours before HemSCs were added to the wells.

For adhesion assays using endothelial cells, 2 × 105 HemECs or ECFCs were plated 48 hours before in a six-well plate. HemSCs (2 × 104) labeled with 10 μmol/L of carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) were used for adhesion to the plated endothelial cells. After a 20-minute incubation, nonadherent cells were washed off, and the remaining cells were trypsinized and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cellular Migration Assay

Migration was measured using modified Boyden chambers with 8-μm-pore–sized filters. Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 per well in 200 μL of migration medium, and were allowed to migrate for 5 hours at 37°C. Recombinant human E-selectin or P-selectin (R&D systems) was placed in the lower chamber of the modified Boyden chamber, in a volume of 600 μL.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Hemangioma Endothelial Cells Isolated from Proliferating Phase Compared to Involuting Phase Overexpress E-Selectin and Have a Higher Vasculogenic Potential When Combined with HemSCs

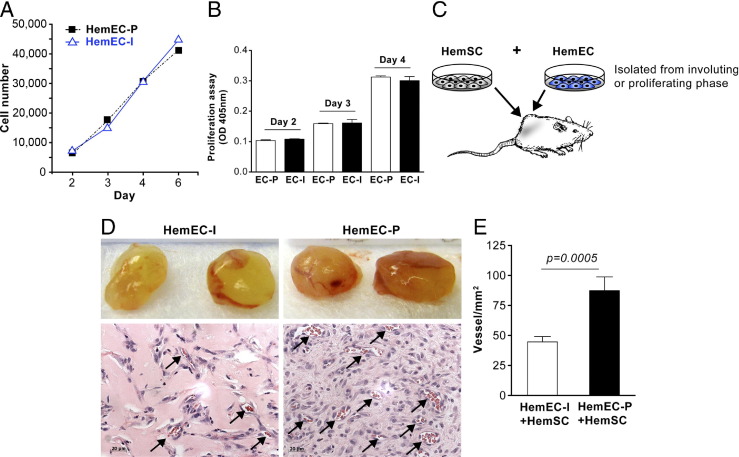

HemECs were isolated, as previously described, from proliferating phase IH tumors5,19 and from involuting phase IH tumors. We designated these cells as HemEC-P (proliferating) and HemEC-I (involuting). HemECs from proliferating and involuting IH were analyzed for proliferative potential in vitro and tested for the ability to form vessels in vivo when co-implanted with HemSCs. Proliferation analyses performed by cell counting or colorimetric assay showed HemEC-P and HemEC-I exhibit nearly identical proliferative potential over 6 days (Figure 1, A and B). In contrast, HemEC-P combined with HemSCs formed more vessels in vivo compared to HemEC-I combined with HemSCs (P < 0.005; Figure 1, D and E). We showed previously that HemECs and/or ECFCs do not form vessels when implanted alone in Matrigel, but require a mesenchymal cell to fulfill the perivascular component.18,20,21 Direct contact with endothelial JAGGED1 promotes HemSCs-to-pericyte differentiation18; however, we did not detect any difference in JAGGED1 protein levels between HemEC-P and HemEC-I (see Supplemental Figure S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 1.

HemEC-P isolated from proliferating IH exhibited increased vasculogenic potential compared to HemEC-I isolated from involuting IH. A: Proliferation of HemEC-P and HemEC-I cultured in EBM-2/20% FBS over 6 days evaluated by counting cells. B: Proliferation of HemEC-P and HemEC-I cultured in EBM-2/20% FBS over 4 days evaluated by measuring cellular phosphatase activity. C: Schematic of in vivo model (note: HemECs implanted alone do not form vessels but require co-implantation with HemSCs).18D: HemSC co-injected with HemEC-I or HemEC-P. Representative photographs of Matrigel explants at day 10 after injection with corresponding histological sections stained with H&E. Arrows point to lumens filled with red blood cells (ie, perfused vessels). E: Quantification of microvessel density (MVD) as vessels/mm2. Scale bar = 20 μm. Data are mean ± SEM.

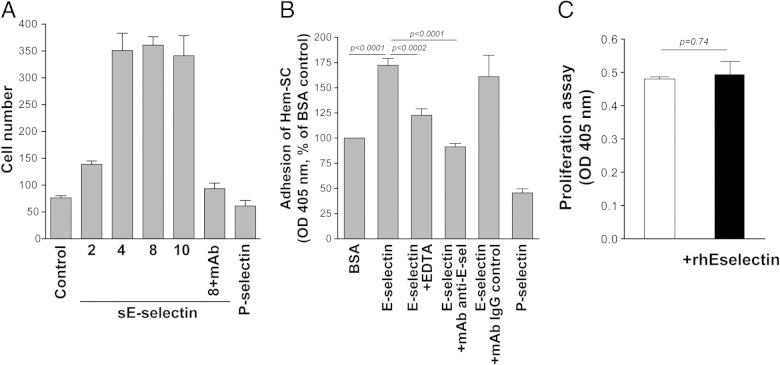

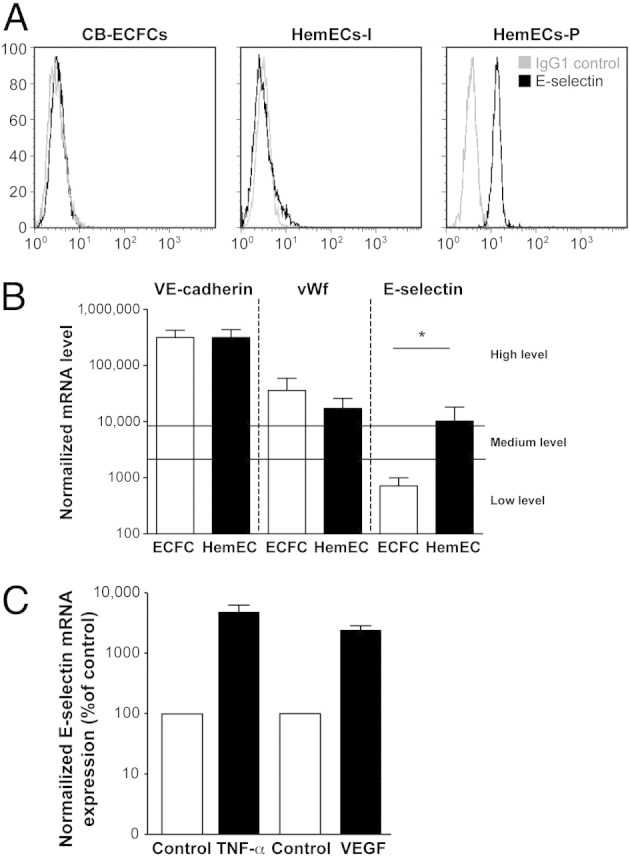

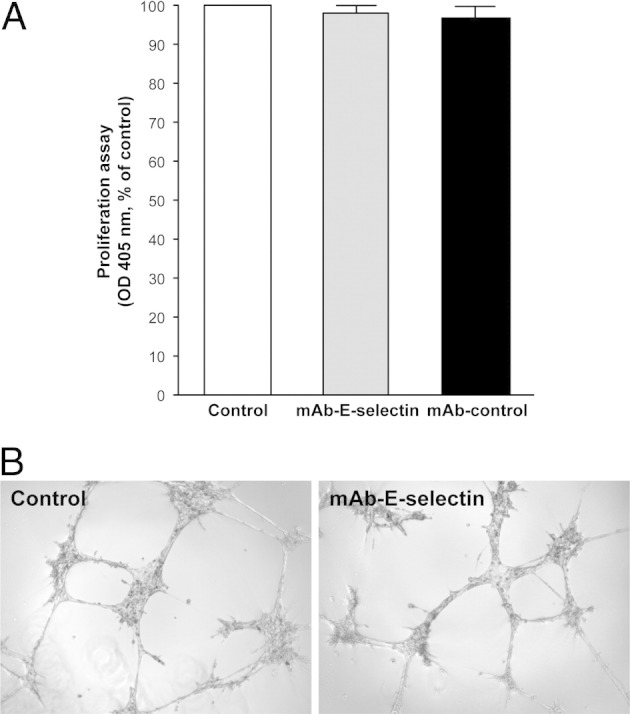

We previously reported high E-selectin expression in proliferating phase IH, which declined in the involuting phase, suggesting a role for E-selectin in IH angiogenesis.14 Consequently, we explored E-selectin levels on HemEC-P and HemEC-I, and found significantly higher expression in HemEC-P at the protein (Figure 2A) and mRNA levels (Figure 2B), in the absence of any inflammatory stimulus. Levels of vascular endothelial-cadherin (VE-cadherin) and von Willebrand factor (vWF) mRNA did not differ (Figure 2B). No significant expression of P- or L-selectin was found (see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). E-selectin levels were up-regulated by inflammatory factors such as TNF-α or angiogenic cytokines such as VEGF at the mRNA (Figure 2C). KLF2 was suppressed by cytokine treatment as previously described in HUVECs23 (see Supplemental Figure S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). As E-selectin has been previously shown to be associated with cellular proliferation, we tested an E-selectin–blocking mAb on HemEC-P proliferation, but found no effect (Figure 3A); nor did E-selectin blocking mAb modify the ability of HemEC-Ps to form pseudo tubes in Matrigel (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

HemEC-P, HemEC-I, and ECFC analyzed for E-selectin. A: Flow-cytometric analysis of HemECs from proliferating and involuting IHs compared with human umbilical cord blood ECFCs. Each cell type was grown under identical conditions in the EBM-2/20% FBS. Black lines: cells labeled with PE-conjugated anti-E-selectin. Gray lines represent cells labeled with PE-conjugated isotype-matched control antibodies. B: RT-PCR analysis of VE-cadherin, von Willebrand factor, and E-selectin in HemEC-P and ECFC. mRNA levels normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels and to sample with lowest quantifiable level (ie, 1 on the left ordinate, corresponding to a Ct value of 35). Values above 100 represent strong gene expression. Mean and SEM values of three different samples are shown at each point. *P < 0.05. C: Effect of TNF-α and VEGF on E-selectin mRNA in HemEC-P.

Figure 3.

Blocking mAb against E-selectin did not affect proliferation or tubulogenesis of HemEC-P. A: mAb against E-selectin (25 ng/mL) did not reduce proliferation of HemEC-P. B: mAb against E-selectin (25 ng/mL) did not inhibit formation of tubular structures on Matrigel.

E-Selectin Induces Migration and Adhesion of HemSCs in Vitro

E-selectin has been described as a chemo-attractant for tumor cells,24–26 mesenchymal stem cells27 or endothelial progenitor cells.28 Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that E-selectin would act as a chemo-attractant for HemSCs and thereby promote recruitment of these stem cells into proliferating-phase IH tumors. HemSCs showed robust spontaneous migration, in a modified Boyden chamber assay,29 toward EBM2 alone or toward EBM2 with FBS and growth factors, compared to HemECs (see Supplemental Figure S4 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We tested migration toward recombinant soluble human E-selectin or P-selectin. HemSCs exhibited increased migration toward E-selectin but not P-selectin (Figure 4A). We also tested adhesion of HemSCs to E-selectin– or P-selectin–coated wells. HemSCs were adherent on E-selectin– but not P-selectin–coated wells. Either ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) or anti–E-selectin inhibited the E-selectin–mediated adhesion (Figure 4B). Recombinant E-selectin had no effect on HemSCs proliferation (Figure 4C). To confirm these findings, we tested the adhesion of fluorescently labeled HemSCs to either proliferating HemEC-P or ECFC, the latter cell type expressing a lower level of E-selectin (Figure 2A). HemSCs labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) adhered more to immobilized HemEC-P as compared to ECFC (Figure 5, A and B). The increased adhesion was reversed in the presence of blocking E-selectin mAb (Figure 5C).

Figure 4.

Recombinant E-selectin induced an increase in migration and adhesion of HemSCs. A: SE-selectin increased HemSC migration in a dose-dependent manner (2 to 10 ng/mL). Recombinant P-selectin at 10 ng/mL had no effect. B: E-selectin increased HemSC adhesion, which was quenched by ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) or E-selectin–blocking mAb. C: Recombinant E-selectin did not affect HemSC proliferation.

Figure 5.

HemSC adhesion on HemEC was partially blocked by mAb against E-selectin. A: HemSCs labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and adhesion to HemEC or ECFC monolayers. B: HemSCs exhibited increased adhesion to HemECs but not to ECFCs. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 4 per group. C: E-selectin blockade decreased HemSC adhesion to HemEC monolayers. The anti–E-selectin mAb was used at 25 ng/mL. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 4 per group.

Blocking E-Selectin Decreases Vasculogenic Potential of HemECs in Vivo

We tested the effect of blocking E-selectin expressed by HemECs in vivo by adding E-selectin blocking mAb to HemEC-P combined with HemSC in Matrigel, which were injected into immune-deficient mice. The E-selectin–blocking mAb significantly reduced microvessel density in the HemSC/HemEC-P Matrigel implants (Figure 6A), decreasing microvessel density by 60% (P < 0.0001; Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Blocking mAb against E-selectin decreased in vivo vasculogenic potential of HemECs co-implanted with HemSCs. A: Representative photographs of Matrigel explants at day 10 after injection of HemSCs and HemECs with control mAb or blocking E-selectin mAb (25 ng/mL), with corresponding sections stained for H&E. Arrows point to lumens filled with red blood cells. B: Quantification of total microvessel density (MVD) as microvessels/mm2. Scale bar = 20 μm. Data are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

In this study, we show the following: i) E-selectin is constitutively expressed on endothelial cells isolated from proliferating phase but not in the involuting phase IH; ii) HemSCs interact with E-selectin expressed on proliferating-phase HemECs; and iii) blocking E-selectin decreases vessel formation in a preclinical model of IH.

HemSCs are the main target of corticosteroid, and they can differentiate into endothelial, perivascular, and adipogenic lineages, the predominant cell types found in the early and late stages of the hemangioma life cycle.12,18 HemSCs are isolated from proliferating IH specimens using anti-CD133–coated magnetic beads. We do not know whether HemSCs initiate hemangioma growth in situ or they are recruited to a site in which pathological endothelial cells initiate hemangioma genesis. In the latter scenario, HemSC may represent a normal postnatal vascular immature cell type that is enlisted into the nascent hemangioma wherein it “boosts” vasculogenesis by its ability to differentiate into both endothelial and perivascular cells. Support for this hypothesis is based on the finding that HemECs are clonal expansions of endothelial cells2 that have a low level of VEGFR1 expression and constitutively activated VEGFR2,5 and thus could be considered as pathological endothelial cells. Moreover, we previously showed that E-selectin is expressed in proliferating phase IH specimens and is co-localized with dividing endothelial cells.14

Endothelial adhesion molecules such as E-selectin could serve as keys to facilitate entry of circulating cells to specific tissue sites.30 Bone marrow– and umbilical cord blood–derived CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells adhere to E-selectin on bone marrow microvasculature.31–34 Endothelial progenitor cells can be recruited to an ischemic site by an E-selectin–dependent mechanism.28 Therefore, we focused on investigating the possible contribution of E-selectin to HemSC angiogenic properties. Indeed, E-selectin on HemEC might be a pivotal first step in the tropism of HemSC in IH growth.

E-Selectin Is Constitutively Expressed in HemECs Isolated from Proliferating Phase

We isolated HemECs directly from surgical specimens. We found HemEC-Ps from proliferating phase IH constitutively express E-selectin whereas HemEC-Is isolated from involuting phase lesions do not. Furthermore, E-selectin expression on HemEC-P distinguishes these cells from cord blood ECFCs, which are circulating neonatal endothelial cells that behave similarly to HemECs in terms of proliferation or endostatin response.19 In most cases, E-selectin is transcriptionally regulated such that it is expressed only after exposure to specific inflammatory stimuli.35 We found E-selectin expressed on the cell surface of nonstimulated HemEC-Ps, and increased expression after the cells were treated with TNF-α or with VEGF-A. We previously described a potential role for nuclear factor–κB (NF-κB) in IH.16 NF-κB is a key transcriptional regulator of E-selectin,36 and several NF-κB targets are overexpressed in proliferating versus involuting IH. Thus the NF-κB pathway could be a pivotal mechanism in HemECs. Indeed, inhibition of NF-κB activity strongly reduced E-selectin promoter activity.37 Direct silencing of NF-κB in vivo could establish a causative role for this signaling pathway in IH.

E-Selectin Is One Mediator of the HemSC-HemEC Cooperation in Vitro and in Vivo

Adhesion of HemSCs was significantly increased in the presence of E-selectin, whereas P-selectin had no such effect. In vivo, administration of an E-selectin–blocking antibody prevented formation of IH blood vessels in our preclinical model, indicating that E-selectin is required for HemSC-HemEC interaction. Other investigators have demonstrated that E-selectin plays a crucial role in the interaction between circulating endothelial progenitor cells and vessel endothelium in an ischemic setting.28,38 In a rat cornea model, Koch and colleagues used cultured human ECs and showed that sE-selectin is a potent angiogenic mediator.39,40 E-selectin has been found to increase expression of ICAM-1 and/or VCAM-1.28 Thus, after stimulating adhesion and migration of HemSCs to pathological ECs, E-selectin could secondarily induce expression of other adhesion molecules in SCs or ECs, which could further increase contact between ECs and SCs. In support of this hypothesis, we show that E-selectin increased migration of HemSCs in vitro in a dose-dependent manner. This suggests that HemSCs can easily migrate into tissue if E-selectin is highly expressed.

Having observed E-selectin expression in an apparently constitutive manner on HemEC-P in vitro, and because E-selectin enhanced migration and adhesion of HemSCs, we analyzed E-selectin function in the cell/Matrigel implant model. We found that vessel formation was significantly decreased when a blocking anti–E-selectin mAb was included. Because we found no difference in proliferative rates between HemEC-P and HemEC-I, in the presence or absence of anti–E-selectin, the decreased vessel formation is not likely due to impaired endothelial proliferation. Instead, we propose that involution of IH could be a consequence of either silencing of E-selectin in HemEC-P or loss of HemEC-Ps and replacement with HemEC-Is. In either case, HemSCs recruitment and adhesion would be diminished. This concept is supported by three earlier findings: i) HemSC synthesize and secrete VEGF-A and thus, decreased recruitment of HemSCs would likely lessen vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in the IH tumor; ii) reduced HemSC recruitment in the involuting phase is consistent with the paucity of CD133-positive cells in the involuting phase IH compared to the proliferating phase IH41; and iii) E-selectin is constitutively expressed in the proliferating phase but not the involuting phase IH. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental evidence that E-selectin has an important role in the formation of blood vessels in IH. A more thorough understanding of the mechanism is needed before E-selectin can be considered a therapeutic target. Inflammatory mediators were not found overexpressed in proliferating IH.42 Our work confirms that a constitutive E-selectin without an inflammatory signal can exist, as has also been described in human brain–derived endothelial cells,43 bone marrow– derived endothelial cells44 or murine lung–derived microvascular endothelial cells.45

Our data are consistent with HemECs as initiating cells in IH pathophysiology, which in turn recruit HemSCs via an E-selectin–dependent mechanism. HemSCs would amplify vasculogenesis in the tumor by contributing to endothelial and perivascular differentiation.12,17,18 This mechanism supports the hypothesis of Rafii and colleagues that specialized endothelial cells are not just passive performers that help to build vessels and to deliver oxygen, but they play central roles in promoting engraftment, self-renewal, and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells,46–48 stem and tumor cell growth,49,50 and tissue repair.51,52

In conclusion, our findings indicate that HemECs in the proliferating phase assume a pro-adhesive E-selectin–positive phenotype that attracts HemSCs. The adhesive interface between the endothelial cell surfaces and HemSCs may present a therapeutic target for blocking stem cell recruitment to tumor sites, especially in hemangioma genesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center for Specialized Histopathology Core, Lan Huang and Elisa Boscolo for helpful discussions, and Kristin Johnson for preparation of the figures.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grant HL096384 (J.B.) and Université Paris Descartes and Fondation de France (D.M.S.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://ajp.amjapathol.org or at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.030.

Supplementary data

JAGGED1 expression quantified by flow-cytometric analysis of HemECs from proliferating (A) and involuting (B) hemangiomas. Each cell type was grown under identical conditions in the EBM-2/20% FBS. Black lines indicate cells labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-JAGGED1 (clone 188331, R&D Systems). Gray lines indicate cells labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated isotype-matched control antibodies. JAGGED1 protein is expressed in both HemEC-P and HemEC-I at similar levels.

HemEC-P and ECFC analyzed for P- and L-selectin. P- and L-selectin expression was analyzed in HemEC-Ps and human umbilical cord blood ECFC as a negative control. Each cell type was grown under identical conditions in the EBM-2/20% FBS. Black lines indicate cells labeled with PE-conjugated anti–P-selectin (A and C) or anti–L-selectin (B and D). Gray lines indicate cells labeled with PE-conjugated isotype-matched control antibodies. In contrast to E-selectin (Figure 2A), no significant expression was found on Hem-EC-P for P- and L-selectin.

Inflammatory stimuli induced a decrease in KLF-2 expression. The effect of recombinant TNF-α (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), or PAR-1–activated peptide SFLLRN (75 μmol/L) activation on KLF-2 levels in HemEC-P was examined. KLF-2 expression was quantified by a Taqman PCR analysis with predesigned probes from Applied Biosystems. The analysis was performed after culturing the cells for 16 hours in unsupplemented EBM-2 medium, followed by a 4-hour treatment with cytokines. These well-known inflammatory activators decreased KLF-2 expression as previously described in HUVEC (Reference 23 in main text), showing that the HemEC-Ps respond appropriately to inflammatory stimuli.

Hem-SCs show increased migration in vitro in a Boyden chamber assay. Migration was measured using modified Boyden chambers with 8-μm-pore–sized filters. HemSC or HemEC-Ps were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 per well in 200 μL of migration medium and were allowed to migrate for 5 hours at 37°C. EBM without serum or growth factors or complete medium EGM2 was placed in the lower chamber of the modified Boyden chamber, in a volume of 600 μL. In both conditions, HemSC showed greater migratory potential compared to HemEC-Ps.

References

- 1.Mulliken J.B., Fishman S.J., Burrows P.E. Vascular anomalies. Curr Probl Surg. 2000;37:517–584. doi: 10.1016/s0011-3840(00)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boye E., Yu Y., Paranya G., Mulliken J.B., Olsen B.R., Bischoff J. Clonality and altered behavior of endothelial cells from hemangiomas. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:745–752. doi: 10.1172/JCI11432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walter J.W., North P.E., Waner M., Mizeracki A., Blei F., Walker J.W., Reinisch J.F., Marchuk D.A. Somatic mutation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in juvenile hemangioma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;33:295–303. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Q., Yu Y., Bischoff J., Mulliken J.B., Olsen B.R. Differential expression of CD146 in tissues and endothelial cells derived from infantile haemangioma and normal human skin. J Pathol. 2003;201:296–302. doi: 10.1002/path.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jinnin M., Medici D., Park L., Limaye N., Liu Y., Boscolo E., Bischoff J., Vikkula M., Boye E., Olsen B.R. Suppressed NFAT-dependent VEGFR1 expression and constitutive VEGFR2 signaling in infantile hemangioma. Nat Med. 2008;14:1236–1246. doi: 10.1038/nm.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes C.M., Huang S., Kaipainen A., Sanoudou D., Chen E.J., Eichler G.S., Guo Y., Yu Y., Ingber D.E., Mulliken J.B., Beggs A.H., Folkman J., Fishman S.J. Evidence by molecular profiling for a placental origin of infantile hemangioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:19097–19102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509579102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.North P.E., Waner M., Mizeracki A., Mrak R.E., Nicholas R., Kincannon J., Suen J.Y., Mihm M.C., Jr. A unique microvascular phenotype shared by juvenile hemangiomas and human placenta. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:559–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calicchio M.L., Collins T., Kozakewich H.P. Identification of signaling systems in proliferating and involuting phase infantile hemangiomas by genome-wide transcriptional profiling. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1638–1649. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinman M.E., Greives M.R., Churgin S.S., Blechman K.M., Chang E.I., Ceradini D.J., Tepper O.M., Gurtner G.C. Hypoxia-induced mediators of stem/progenitor cell trafficking are increased in children with hemangioma. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2664–2670. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.150284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinman M.E., Tepper O.M., Capla J.M., Bhatt K.A., Ceradini D.J., Galiano R.D., Blei F., Levine J.P., Gurtner G.C. Increased circulating AC133+ CD34+ endothelial progenitor cells in children with hemangioma. Lymphat Res Biol. 2003;1:301–307. doi: 10.1089/153968503322758102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritter M.R., Reinisch J., Friedlander S.F., Friedlander M. Myeloid cells in infantile hemangioma. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:621–628. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan Z.A., Boscolo E., Picard A., Psutka S., Melero-Martin J.M., Bartch T.C., Mulliken J.B., Bischoff J. Multipotential stem cells recapitulate human infantile hemangioma in immunodeficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2592–2599. doi: 10.1172/JCI33493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberger S., Boscolo E., Adini I., Mulliken J.B., Bischoff J. Corticosteroid suppression of VEGF-A in infantile hemangioma-derived stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1005–1013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kraling B.M., Razon M.J., Boon L.M., Zurakowski D., Seachord C., Darveau R.P., Mulliken J.B., Corless C.L., Bischoff J. E-selectin is present in proliferating endothelial cells in human hemangiomas. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1181–1191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verkarre V., Patey-Mariaud de Serre N., Vazeux R., Teillac-Hamel D., Chretien-Marquet B., Le Bihan C., Leborgne M., Fraitag S., Brousse N. ICAM-3 and E-selectin endothelial cell expression differentiate two phases of angiogenesis in infantile hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:17–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberger S., Adini I., Boscolo E., Mulliken J.B., Bischoff J. Targeting NF-kappaB in infantile hemangioma-derived stem cells reduces VEGF-A expression. Angiogenesis. 2010;13:327–335. doi: 10.1007/s10456-010-9189-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boscolo E., Mulliken J.B., Bischoff J. VEGFR-1 mediates endothelial differentiation and formation of blood vessels in a murine model of infantile hemangioma. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2266–2277. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boscolo E., Stewart C.L., Greenberger S., Wu J.K., Durham J.T., Herman I.M., Mulliken J.B., Kitajewski J., Bischoff J. JAGGED1 signaling regulates hemangioma stem cell-to-pericyte/vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2181–2192. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan Z.A., Melero-Martin J.M., Wu X., Paruchuri S., Boscolo E., Mulliken J.B., Bischoff J. Endothelial progenitor cells from infantile hemangioma and umbilical cord blood display unique cellular responses to endostatin. Blood. 2006;108:915–921. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-006478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melero-Martin J.M., De Obaldia M.E., Kang S.Y., Khan Z.A., Yuan L., Oettgen P., Bischoff J. Engineering robust and functional vascular networks in vivo with human adult and cord blood-derived progenitor cells. Circ Res. 2008;103:194–202. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melero-Martin J.M., Khan Z.A., Picard A., Wu X., Paruchuri S., Bischoff J. In vivo vasculogenic potential of human blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;109:4761–4768. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang K.T., Allen P., Bischoff J. Bioengineered human vascular networks transplanted into secondary mice reconnect with the host vasculature and re-establish perfusion. Blood. 2011;118:6718–6721. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-375188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SenBanerjee S., Lin Z., Atkins G.B., Greif D.M., Rao R.M., Kumar A., Feinberg M.W., Chen Z., Simon D.I., Luscinskas F.W., Michel T.M., Gimbrone M.A., Jr., Garcia-Cardena G., Jain M.K. KLF2 is a novel transcriptional regulator of endothelial proinflammatory activation. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1305–1315. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Z.J., Tian R., Li Y., An W., Zhuge Y., Livingstone A.S., Velazquez O.C. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and melanoma growth by targeting vascular E-selectin. Ann Surg. 2011;254:450–456. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822a72dc. discussion 456–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barthel S.R., Wiese G.K., Cho J., Opperman M.J., Hays D.L., Siddiqui J., Pienta K.J., Furie B., Dimitroff C.J. Alpha 1,3 fucosyltransferases are master regulators of prostate cancer cell trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19491–19496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiratsuka S., Goel S., Kamoun W.S., Maru Y., Fukumura D., Duda D.G., Jain R.K. Endothelial focal adhesion kinase mediates cancer cell homing to discrete regions of the lungs via E-selectin up-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:3725–3730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100446108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thankamony S.P., Sackstein R. Enforced hematopoietic cell E- and L-selectin ligand (HCELL) expression primes transendothelial migration of human mesenchymal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2258–2263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018064108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh I.Y., Yoon C.H., Hur J., Kim J.H., Kim T.Y., Lee C.S., Park K.W., Chae I.H., Oh B.H., Park Y.B., Kim H.S. Involvement of E-selectin in recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells and angiogenesis in ischemic muscle. Blood. 2007;110:3891–3899. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-048991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smadja D.M., Bieche I., Uzan G., Bompais H., Muller L., Boisson-Vidal C., Vidaud M., Aiach M., Gaussem P. PAR-1 activation on human late endothelial progenitor cells enhances angiogenesis in vitro with upregulation of the SDF-1/CXCR4 system. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2321–2327. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000184762.63888.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frenette P.S., Mayadas T.N., Rayburn H., Hynes R.O., Wagner D.D. Susceptibility to infection and altered hematopoiesis in mice deficient in both P- and E-selectins. Cell. 1996;84:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naiyer A.J., Jo D.Y., Ahn J., Mohle R., Peichev M., Lam G., Silverstein R.L., Moore M.A., Rafii S. Stromal derived factor-1-induced chemokinesis of cord blood CD34(+) cells (long-term culture-initiating cells) through endothelial cells is mediated by E-selectin. Blood. 1999;94:4011–4019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dimitroff C.J., Lee J.Y., Rafii S., Fuhlbrigge R.C., Sackstein R. CD44 is a major E-selectin ligand on human hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1277–1286. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hidalgo A., Weiss L.A., Frenette P.S. Functional selectin ligands mediating human CD34(+) cell interactions with bone marrow endothelium are enhanced postnatally. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:559–569. doi: 10.1172/JCI14047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenberg A.W., Kerr W.G., Hammer D.A. Relationship between selectin-mediated rolling of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and progression in hematopoietic development. Blood. 2000;95:478–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bevilacqua M.P., Stengelin S., Gimbrone M.A., Jr., Seed B. Endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1: an inducible receptor for neutrophils related to complement regulatory proteins and lectins. Science. 1989;243:1160–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.2466335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schindler U., Baichwal V.R. Three NF-kappa B binding sites in the human E-selectin gene required for maximal tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5820–5831. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tabatabai G., Herrmann C., von Kurthy G., Mittelbronn M., Grau S., Frank B., Mohle R., Weller M., Wick W. VEGF-dependent induction of CD62E on endothelial cells mediates glioma tropism of adult haematopoietic progenitor cells. Brain. 2008;131:2579–2595. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishiwaki Y., Yoshida M., Iwaguro H., Masuda H., Nitta N., Asahara T., Isobe M. Endothelial E-selectin potentiates neovascularization via endothelial progenitor cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:512–518. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000254812.23238.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koch A.E., Halloran M.M., Haskell C.J., Shah M.R., Polverini P.J. Angiogenesis mediated by soluble forms of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Nature. 1995;376:517–519. doi: 10.1038/376517a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar P., Amin M.A., Harlow L.A., Polverini P.J., Koch A.E. Src and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediate soluble E-selectin-induced angiogenesis. Blood. 2003;101:3960–3968. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Y., Flint A.F., Mulliken J.B., Wu J.K., Bischoff J. Endothelial progenitor cells in infantile hemangioma. Blood. 2004;103:1373–1375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ritter M.R., Dorrell M.I., Edmonds J., Friedlander S.F., Friedlander M. Insulin-like growth factor 2 and potential regulators of hemangioma growth and involution identified by large-scale expression analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7455–7460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102185799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong D., Dorovini-Zis K. Regualtion by cytokines and lipopolysaccharide of E-selectin expression by human brain microvessel endothelial cells in primary culture. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:225–235. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199602000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schweitzer K.M., Drager A.M., van der Valk P., Thijsen S.F., Zevenbergen A., Theijsmeijer A.P., van der Schoot C.E., Langenhuijsen M.M. Constitutive expression of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 on endothelial cells of hematopoietic tissues. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:165–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerritsen M.E., Shen C.P., McHugh M.C., Atkinson W.J., Kiely J.M., Milstone D.S., Luscinskas F.W., Gimbrone M.A., Jr. Activation-dependent isolation and culture of murine pulmonary microvascular endothelium. Microcirculation. 1995;2:151–163. doi: 10.3109/10739689509146763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hooper A.T., Butler J.M., Nolan D.J., Kranz A., Iida K., Kobayashi M., Kopp H.G., Shido K., Petit I., Yanger K., James D., Witte L., Zhu Z., Wu Y., Pytowski B., Rosenwaks Z., Mittal V., Sato T.N., Rafii S. Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butler J.M., Nolan D.J., Vertes E.L., Varnum-Finney B., Kobayashi H., Hooper A.T., Seandel M., Shido K., White I.A., Kobayashi M., Witte L., May C., Shawber C., Kimura Y., Kitajewski J., Rosenwaks Z., Bernstein I.D., Rafii S. Endothelial cells are essential for the self-renewal and repopulation of Notch-dependent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobayashi H., Butler J.M., O'Donnell R., Kobayashi M., Ding B.S., Bonner B., Chiu V.K., Nolan D.J., Shido K., Benjamin L., Rafii S. Angiocrine factors from Akt-activated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1046–1056. doi: 10.1038/ncb2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seandel M., Butler J.M., Kobayashi H., Hooper A.T., White I.A., Zhang F., Vertes E.L., Kobayashi M., Zhang Y., Shmelkov S.V., Hackett N.R., Rabbany S., Boyer J.L., Rafii S. Generation of a functional and durable vascular niche by the adenoviral E4ORF1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19288–19293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805980105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Curradi G., Walters M.S., Ding B.S., Rafii S., Hackett N.R., Crystal R.G. Airway basal cell vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated cross-talk regulates endothelial cell-dependent growth support of human airway basal cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2217–2231. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0922-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding B.S., Nolan D.J., Butler J.M., James D., Babazadeh A.O., Rosenwaks Z., Mittal V., Kobayashi H., Shido K., Lyden D., Sato T.N., Rabbany S.Y., Rafii S. Inductive angiocrine signals from sinusoidal endothelium are required for liver regeneration. Nature. 2010;468:310–315. doi: 10.1038/nature09493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ding B.S., Nolan D.J., Guo P., Babazadeh A.O., Cao Z., Rosenwaks Z., Crystal R.G., Simons M., Sato T.N., Worgall S., Shido K., Rabbany S.Y., Rafii S. Endothelial-derived angiocrine signals induce and sustain regenerative lung alveolarization. Cell. 2011;147:539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

JAGGED1 expression quantified by flow-cytometric analysis of HemECs from proliferating (A) and involuting (B) hemangiomas. Each cell type was grown under identical conditions in the EBM-2/20% FBS. Black lines indicate cells labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-JAGGED1 (clone 188331, R&D Systems). Gray lines indicate cells labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated isotype-matched control antibodies. JAGGED1 protein is expressed in both HemEC-P and HemEC-I at similar levels.

HemEC-P and ECFC analyzed for P- and L-selectin. P- and L-selectin expression was analyzed in HemEC-Ps and human umbilical cord blood ECFC as a negative control. Each cell type was grown under identical conditions in the EBM-2/20% FBS. Black lines indicate cells labeled with PE-conjugated anti–P-selectin (A and C) or anti–L-selectin (B and D). Gray lines indicate cells labeled with PE-conjugated isotype-matched control antibodies. In contrast to E-selectin (Figure 2A), no significant expression was found on Hem-EC-P for P- and L-selectin.

Inflammatory stimuli induced a decrease in KLF-2 expression. The effect of recombinant TNF-α (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), or PAR-1–activated peptide SFLLRN (75 μmol/L) activation on KLF-2 levels in HemEC-P was examined. KLF-2 expression was quantified by a Taqman PCR analysis with predesigned probes from Applied Biosystems. The analysis was performed after culturing the cells for 16 hours in unsupplemented EBM-2 medium, followed by a 4-hour treatment with cytokines. These well-known inflammatory activators decreased KLF-2 expression as previously described in HUVEC (Reference 23 in main text), showing that the HemEC-Ps respond appropriately to inflammatory stimuli.

Hem-SCs show increased migration in vitro in a Boyden chamber assay. Migration was measured using modified Boyden chambers with 8-μm-pore–sized filters. HemSC or HemEC-Ps were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 per well in 200 μL of migration medium and were allowed to migrate for 5 hours at 37°C. EBM without serum or growth factors or complete medium EGM2 was placed in the lower chamber of the modified Boyden chamber, in a volume of 600 μL. In both conditions, HemSC showed greater migratory potential compared to HemEC-Ps.