Abstract

Aim

The effect of orexin on wakefulness has been suggested to be largely mediated by activation of histaminergic neurones in the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) via orexin receptor-2 (OX2R). However, orexin receptors in other regions of the brain might also play important roles in maintenance of wakefulness. To dissect the role of the histaminergic system as a downstream mediator of the orexin system in the regulation of sleep/wake states without compensation by the orexin receptor-1 (OX1R) mediated pathways, we analysed the phenotype of Histamine-1 receptor (H1R) and OX1R double-deficient (H1R−/−;OX1R−/−) mice. These mice lack OX1R-mediated pathways in addition to deficiency of H1R, which is thought to be the most important system in downstream of OX2R.

Methods

We used H1R deficient (H1R−/−) mice, H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice, OX1R and OX2R double-deficient (OX1R−/−;OX2R−/−) mice, and wild type controls. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, non-REM (NREM) sleep and awake states were determined by polygraphic electroencephalographic/electromyographic recording.

Results

No abnormality in sleep/wake states was observed in H1R−/− mice, consistent with previous studies. H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice also showed a sleep/wake phenotype comparable to that of wild type mice, while OX1R−/−; OX2R−/− mice showed severe fragmentation of sleep/wake states.

Conclusion

Our observations showed that regulation of the sleep/wake states is completely achieved by OX2R-expressing neurones without involving H1R-mediated pathways. The maintenance of basal physiological sleep/wake states is fully achieved without both H1 and OX1 receptors. Downstream pathways of OX2R other than the histaminergic system might play an important role in the maintenance of sleep/wake states.

Keywords: electroencephalography, histamine H1 receptor, orexin receptor-1, orexin receptor-2, sleep/wake states, tuberomammillary nucleus

Recent studies on the efferent and afferent systems of orexin/hypocretin neurones, and phenotypic characterization of mice with genetic modification of the orexin system have suggested roles of the orexin system in regulation of sleep and wakefulness through interactions with systems that regulate emotion, the reward system and energy homeostasis (Yamanaka et al. 2003, Akiyama et al. 2004, Mieda et al. 2004, Boutrel et al. 2005, Harris et al. 2005, Sakurai et al. 2005, Narita et al. 2006, Yoshida et al. 2006). There are two orexin receptor subtypes, named orexin receptor-1 (OX1R) and orexin receptor-2 (OX2R) (Sakurai et al. 1998). Orexin-producing neurones, localized in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), send projections to all over the central nervous system except the cerebellum. Especially dense orexin-immunoreactive fibres are found in monoaminergic and cholinergic nuclei in the brain stem regions (Marcus et al. 2001). Moreover, these nuclei abundantly express orexin receptors.

Mice with targeted deletion of the prepro-orexin gene (Orexin−/− mice) display a phenotype strikingly similar to human narcolepsy (Chemelli et al. 1999). Besides, functionally null mutations in the OX2R gene were found in familial narcoleptic dogs (Lin et al. 1999). Consistently, OX2R−/− mice show fragmented sleep/wake behaviour and direct transitions from wakefulness to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, although the phenotype is significantly milder than that of Orexin−/− mice, whereas OX1R−/− mice do not have any overt behavioural abnormalities (Willie et al. 2001). These observations suggest that the OX2R-mediated pathway has pivotal roles, while OX1R has an additional role in the regulation of sleep/wake states. Narcoleptic human brains have been shown to contain markedly reduced numbers of orexin neurones (Peyron et al. 2000, Thannickal et al. 2000).

Orexin receptors are distributed in a pattern consistent with orexin projections. mRNAs for OX1R and OX2R are differentially expressed throughout the brain (Marcus et al. 2001). OX1R mRNA is most abundantly expressed in the locus coeruleus (LC), whereas OX2R mRNA is most abundantly expressed in the histaminergic tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN). The raphe nuclei and laterodorsal/pedunculopontine tegmental nuclei (LDT/PPT) contain mRNA for both receptors. In vitro electrophysiological studies have also shown that all these monoaminergic/cholinergic neurones are activated by orexins (Sakurai 2007). These monoaminergic/cholinergic neurones are implicated in regulation of sleep/wake states (Vanni-Mercier et al. 1984).

Huang et al. (2001) suggested that the arousal effect of orexin A largely depends on activation of histaminergic neurotransmission mediated by histamine receptor-1 (H1R). This observation suggests the importance of H1R as the downstream player of orexin system. Consistently, the histamine concentration in the brain is decreased in OX2R-mutated narcoleptic dogs (Lin et al. 1999).

Histaminergic neurones are exclusively localized in the TMN (Watanabe et al. 1984), and project to practically all brain regions, with especially dense innervations in the hypothalamus, basal forebrain and amygdala (Panula & Costa 1984, Takeda et al. 1984). It has been reported that the firing rates of histamine neurones vary across the sleep/wake cycle (Sakai et al. 1990), and intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of histamine or a H1R agonist induces wakefulness and diminution of non-REM (NREM) sleep (Monti et al. 1986, Tasaka et al. 1989, Monti 1993). These results suggest that the brain histaminergic system plays a critical role in regulation of sleep/wake states through activation of H1R.

Orexin neurones densely innervate TMN neurones, in which OX2R is abundantly expressed (Marcus et al. 2001), further suggesting the possibility that orexin neurones regulate vigilance and arousal through modulating the activity of histaminergic neurones in the TMN.

In the present study, we analysed the role of the H1R as downstream signalling of the OX2R-mediated pathway, using H1R and OX1R double-deficient mice (H1R−/−;OX1R−/−). In these mice, the OX1R-mediated pathway was totally abolished, while the OX2R-mediated pathway remained intact, but the H1R-mediated pathway was deficient. Therefore, these mice enable us to analyse the roles of the H1R-mediated pathway as the downstream mediator of orexins without compensation by OX1R-mediated pathways.

Materials and methods

Animals

All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted with the approval of the University of Tsukuba and Kanazawa University Animal Care Committees. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to limit the number of animals used. Procedures related to handling of H1R−/− mice and OX1−/− and OX2R−/− mice have been described in detail previously (Inoue et al. 1996).OX1R/− and OX2R/− mice were also described previously (Willie et al. 2001, 2003). H1R+/−;OX1R+/− mice were obtained by mating H1R−/− mice and OX1R−/− mice; then we crossed them to obtain H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice. As a wild type control mice, we used littermates of H1R−/− mice. Mice were housed under controlled lighting (12 h light–dark cycle; light on at 08:00 hours, off at 20:00 hours) and temperature conditions. Food and water were available ad libitum. All mice were backcrossed with C57BL/6J mice at least six times. We analysed H1R−/− (n = 4), H1R−/−;OX1R−/− (n = 4), OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− (n = 5) and wild type mice (n = 5).

Surgery

Male mice (10–12 weeks old, 20–25 g at the time of surgery) were prepared for chronic monitoring of electroencephalographic/electromyographic (EEG/EMG) signals using a lightweight implant and cabling procedure. Full details of this technique have been published previously (Chemelli et al. 1999). Briefly, the EEG/EMG implant was based on a six-pin double inline microcomputer connector, modified to form four EEG electrodes, each 1.3 mm × 0.3 mm (h × w), positioned 4.6 mm × 2.9 mm (l × w) apart, with two EMG electrodes soldered to the entry pins. Mice were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, 50–60 mg kg−1 i.p.), and standard sterile surgical and stereotaxic procedures were employed for implant placement. Four burr holes were drilled in the cranium, anterior and posterior to the bregma, bilaterally (AP 1.1, ML 1.4 and AP-3.6, ML1.4) according to the atlas of Franklin & Paxinos (1997). The implant was then inserted into these holes and fixed to the skull with adhesive dental cement, the EMG electrodes were placed into the nuchal musculature and the wounds were closed with sutures.

Sleep recording

Immediately after surgery, mice were housed singly for a recovery period of 1 week. The head-mounted connector was coupled via a lightweight cable to a slip ring commutator, which was suspended from a counterbalanced arm mounted on a standard shoebox cage (19 cm × 30 cm; Allentown Caging, Allentown, NJ, USA). This allowed mice full freedom of movement. The cage was modified to provide side delivery of food and water, which were available ad libitum. All mice were habituated to these conditions for at least 7 days before the start of recording. Then, EEG/EMG recording for two consecutive 24 h periods, beginning at lights on at 20:00 hours was performed. Infrared video recording was simultaneously performed. EEG/EMG signals were amplified using a multichannel amplifier (Nihon Koden, Tokyo, Japan) and filtered (EEG: 0.5–100 Hz; EMG: 0.5–100 Hz) before being digitized at a sampling rate of 250 Hz, displayed on a paperless polygraph system and archived for off-line sleep staging and analysis.

Sleep scoring and data analysis

EEG/EMG records were visually scored into 16-s epochs of awake, REM sleep and NREM sleep. Data were analysed by two-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc analysis of significance with Bonferroni’s or Student’s t-test using the Stat View 5.0 software package (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA, USA). In all cases, P < 0.001 was taken as the level of significance.

Results

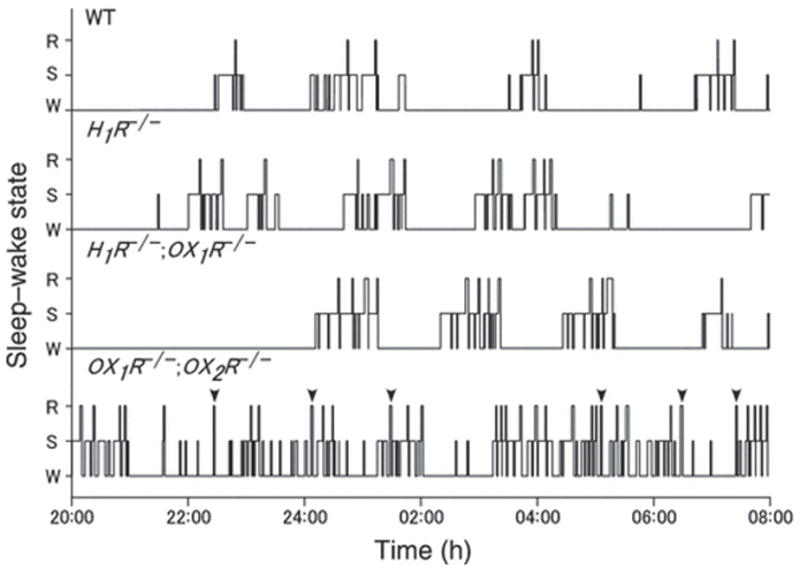

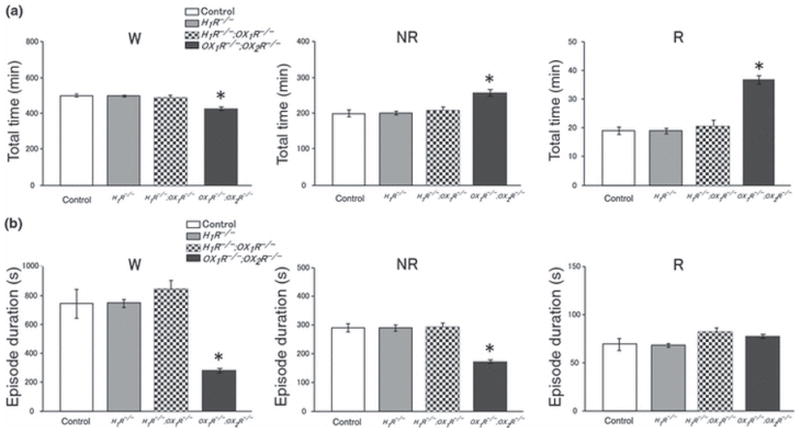

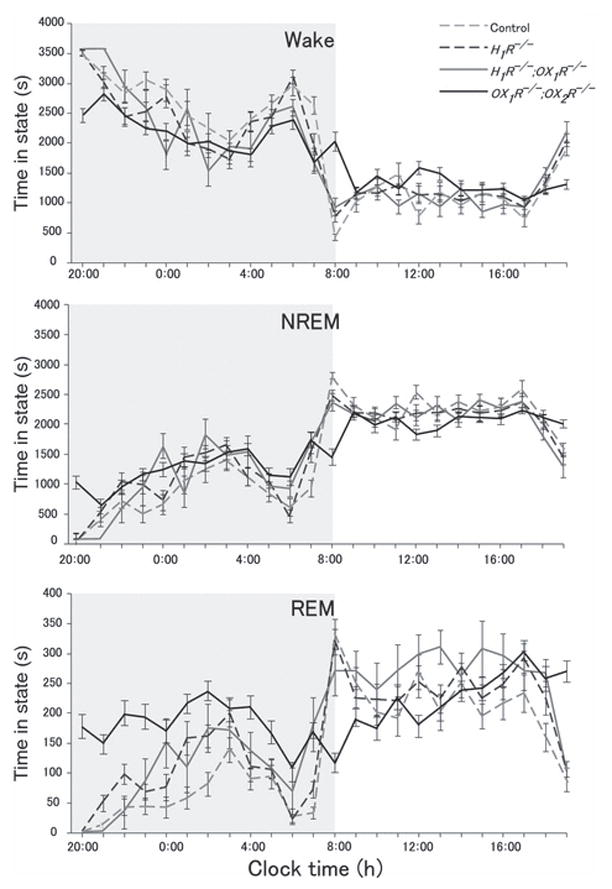

Sleep state patterns of wild type mice, H1R−/− mice, H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice and OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice were revealed by simultaneous EEG/EMG recording as reported previously (Chemelli et al. 1999). Typical representative 12 h dark period (20:00 hours to 08:00 hours) hypnograms for wild type mice, H1R−/− mice, H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice and OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice are shown in Figure 1. Under baseline conditions, the patterns of sleep/wake states were not statistically different among wild type mice, H1R−/− mice and H1R−/−; OX1R−/− mice (Fig. 2, Table 1). There were no significant differences between wild type mice, H1R−/− mice and H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice, in both the amount and duration of NREM sleep, REM sleep and wakefulness during the dark period (Fig. 2). These parameters were not distinguishable among any of the genotypes during the light period. Hourly analysis of quantities of NREM sleep, REM sleep and wakefulness also revealed no differences between wild type mice, H1R−/− mice and H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice (Fig. 3). In contrast, OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice showed severe fragmentation of sleep/wakefulness states, reflected in significantly shorter duration of wakefulness, and frequent direct transitions from wakefulness to REM sleep, as described previously (Willie et al. 2003) (Figs 1 and 2). OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice showed abnormal circadian distribution of REM sleep (Fig. 3). These phenotypes are similar to those of Orexin−/− mice (Chemelli et al. 1999).

Figure 1.

Representative 12 h dark period (20:00 hours to 08:00 hours) hypnograms for wild type mice (WT), H1R−/− mice, H1R−/−; OX1R−/− mice and OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice. The height of the horizontal line above baseline indicates the vigilance state of the mouse at the time. W, wakefulness; NR, non-rapid eye movement (REM) sleep; R, REM sleep. There were no significant differences in sleep/wake phenotypes between wild type mice, H1R−/− mice, and H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice. In contrast, OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice showed severe fragmentation of sleep/wake states, along with frequent direct transitions from wakefulness to REM sleep (mark with arrowhead). Hypnograms were obtained by simultaneous EEG/EMG recording as described previously (Chemelli et al. 1999).

Figure 2.

(a) Total time (min, mean ± SEM) spent in each state in control mice (wild type) (n = 5), H1R−/− mice (n = 4), H1R−/−; OX1R−/− mice (n = 4) and OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice (n = 5). W, awake; NR, non-rapid eye movement (REM) sleep; R, REM sleep. The graphs summarize the data recorded during the 12 h dark period. (B) Episode duration (s ± SEM) spent in each state in control mice, H1R−/− mice, H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice and OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice. W, awake; NR, non-REM sleep; R, REM sleep. OX1R−/−; OX2R−/− mice show significantly shorter wakefulness and NREM sleep episodes during dark period. Mice with other genotypes did not show any abnormality in sleep/wake states. *P < 0.001. The graphs summarize the data recorded during the 12 h dark period.

Table 1.

Total time spent in each state (min, mean ± SEM), episode duration (s, mean ± SEM), and rapid eye movement (REM) latency (min, mean ± SEM) over 24 h, itemized separately for light and dark periods

| REM sleep | Non-REM sleep | Awake | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| WT | H1R−/− | H1R−/−/OX1R−/− | OX1R−/−/OX2R−/− | WT | H1R−/− | H1R−/−/OX1R−/− | OX1R−/−/OX2R−/− | WT | H1R−/− | H1R−/−/OX1R−/− | OX1R−/−/OX2R−/− | |

| 24 h | ||||||||||||

| Total time (min) | 65.8 ± 1.6 | 66.9 ± 2.4 | 70.0 ± 4.2 | 81.3 ± 0.9 | 636.1 ± 13.4 | 635.2 ± 6.6 | 639.5 ± 13.7 | 651.7 ± 12.0 | 735.1 ± 11.5 | 737.9 ± 7.0 | 726.2 ± 16.8 | 707.0 ± 12.7 |

| Episode duration (s) | 71.5 ± 3.2 | 70.0 ± 1.5 | 82.8 ± 2.4 | 71.48 ± 2.0 | 288.9 ± 16.2 | 287.3 ± 7.0 | 289.9 ± 9.5 | 216.4 ± 9.2 | 456.1 ± 107.9 | 452.7 ± 49.4 | 531.7 ± 69.7 | 247.2 ± 16.3* |

| REM latency (min) | 368.3 ± 19.1 | 353.0 ± 9.9 | 364.1 ± 15.8 | 232.5 ± 49.6* | ||||||||

| REM counts | 25.4 ± 2.1 | 25.8 ± 2.0 | 28.2 ± 3.3 | 32.8 ± 3.8 | ||||||||

| Light period | ||||||||||||

| Total time (min) | 46.8 ± 1.3 | 47.9 ± 1.6 | 49.4 ± 3.0 | 44.6 ± 1.3 | 435.7 ± 5.7 | 433.4 ± 4.9 | 430.5 ± 6.7 | 405.6 ± 3.2 | 233.4 ± 5.0 | 238.6 ± 5.5 | 235.8 ± 7.4 | 269.83 ± 3.2 |

| Episode duration (s) | 73.6 ± 3.0 | 71.8 ± 2.2 | 83.5 ± 2.7 | 66.9 ± 3.4 | 286.4 ± 31.0 | 284.0 ± 9.0 | 287.8 ± 9.6 | 239.4 ± 15.3 | 165.6 ± 18.3 | 155.8 ± 4.5 | 214.6 ± 13.0 | 163.4 ± 9.1 |

| REM latency (s) | 328.3 ± 18.7 | 323.1 ± 10.1 | 328.5 ± 12.9 | 282.2 ± 9.5 | ||||||||

| REM counts | 35.13 ± 2.3 | 37.1 ± 2.1 | 36.8 ± 4.7 | 37 ± 0.9 | ||||||||

| Dark period | ||||||||||||

| Total time (min) | 19.0 ± 1.2 | 19.0 ± 1.0 | 20.6 ± 2.1 | 36.7 ± 1.0* | 200.4 ± 9.7 | 201.8 ± 5.4 | 209.0 ± 10.4 | 246 ± 7.3* | 501.7 ± 8.1 | 499.2 ± 5.6 | 490.4 ± 12.0 | 437 ± 7.8* |

| Episode duration (s) | 69.4 ± 6.0 | 68.2 ± 2.0 | 82.1 ± 4.2 | 76 ± 1.7 | 291.4 ± 14.6 | 290.4 ±10.8 | 292.1 ± 16.8 | 193 ± 8.2* | 746.6 ± 99.5 | 749.5 ± 27.1 | 848.8 ± 57.5 | 331 ± 21.0* |

| REM latency (s) | 403.2 ± 29.6 | 382.2 ± 13.7 | 399.7 ± 25.6 | 182 ± 7.3* | ||||||||

| REM counts | 15.7 ± 1.2 | 16.7 ± 0.9 | 19.6 ± 3.2 | 29 ± 1.0* | ||||||||

There were no significant differences between control mice, H1R−/− mice and H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice. OX1R −/−;OX2R−/− mice showed significantly shorter duration of wakefulness. REM latency is the average time of non-REM sleep duration before each REM sleep epoch. REM counts are numbers of REM sleep during each period.

P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Hourly analysis of sleep/wake amounts in control mice (n = 5), H1R−/− mice (n = 4), H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice (n = 4) and OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice (n = 5). The shaded areas represent the 12 h dark period. There are no significant differences between control mice, H1R−/− mice, H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice, while OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice show abnormal circadian distribution of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Discussion

The actions of orexins are mediated via two G protein-coupled receptors, OX1R and OX2R. Although these orexin receptors are expressed in a pattern consistent with orexin projections, mRNAs for OX1R and OX2R are differentially distributed in the brain, suggesting their distinct roles. Several studies have indicated that the effect of orexin is largely or partially mediated by activation of the histaminergic H1R in the downstream of OX2R in the TMN (Eriksson et al. 2001, Huang et al. 2001, Yamanaka et al. 2002, Shigemoto et al. 2004). Consistently, OX2R−/− mice are affected by cataplexy-like attacks of REM sleep and sleep/wake fragmentation (Willie et al. 2001, Sakurai 2007), although the phenotype of OX2R−/− mice was significantly less severe than that of OX1R−/−;OX2R−/− mice (Willie et al. 2003, Sakurai 2007). From these observations, the histaminergic pathway is currently thought to be the important link in the OX2R pathway in arousal regulation.

Three distinct subtypes of histamine receptors, H1 receptor (H1R), H2 receptor (H2R) and H3 receptor (H3R), are distributed in the brain and exhibit well-defined distribution patterns (Bouthenet et al. 1988, Martinez-Mir et al. 1990). H1R and H2R are post-synaptic receptors coupled to Gq/11 and Gs protein, and H3R is a pre-synaptic autoreceptor coupled to Gi/o protein. Huang et al. 2001 showed that the arousal effect of orexin A almost totally depends on activation of histaminergic neurotransmission mediated by H1R. However, Huang et al. 2006 also reported that H1R−/− mice showed sleep/wake states essentially identical to those of wild type mice but with fewer incidents of brief awakening (<16 s epochs), and prolonged durations of NREM sleep episodes, although the physiological significance of brief awakening is not yet well understood (Huang et al. 2006). This suggests that the physiological function of H1R does not contribute to regulation of the basal amount of sleep/wake states. Besides, histidine decarboxylase (HDC)-deficient mice showed clear sleep/wake phenotypes, suggesting the possible involvement of H2R and H3R in physiological regulation of sleep/wake states (Parmentier et al. 2002). However, previous pharmacological studies demonstrated that the clinical use of H1R antagonists induces sleepiness (Nicholson et al. 1985). Also, slow-wave sleep is induced in cats by microinjection of the selective H1R antagonist pyrilamine into the pre-optic area (Lin & Jouvet 1994) or the dorsal pontine tegmentum (Lin et al. 1996). These results suggest that H1R mediates the waking effect of histamine. These observations suggest a possibility that the normal sleep/wake phenotype of H1R−/− mice is compensated by other systems such as OX1R-mediated activation of the noradrenergic neurones in the LC.

In this study, we analysed H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice to define the importance of the role of H1R as a downstream effector of the orexinergic system in sleep/wake regulation. These mice lack both OX1R-mediated regulation of noradrenergic neurones in the LC, and the H1R system belonging to downstream of OX2R in the TMN. Signalling pathways in downstream of OX2R, such as serotonergic neurones in the raphe nuclei (Brown et al. 2002), cholinergic neurones in the LDT/PPT (Burlet et al. 2002), and dopaminergic neurones in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) remain intact (Korotkova et al. 2003). The raphe nuclei, LDT/PPT and VTA also abundantly express OX1R in wild type mice, but in H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice, only OX2R is expressed in these regions. By using these mice, we analysed the role of the H1R system belonging to downstream of OX2R. We found that H1R−/−;OX1R−/− mice showed a normal sleep/wake phenotype compared with wild type mice. These results are not consistent with the hypothesis that ‘activation of H1R in the downstream of OX2R is the most important pathway in sleep/wake regulation by orexin’. Consistent with our present results, Blanco-Centurion et al. (2007) reported that saporin-induced lesions in histaminergic neurones in the TMN, along with cholinergic neurones in the basal forebrain (BF), and noradrenergic neurones in the LC did not change the waking amount, although the lesions affected the transition time of the light-dark phase (Blanco-Centurion 2007). Our observations suggest that regulation of basal physiological sleep/wake states is fully achieved without H1R even when OX1R is absent. Loss of the H1R-mediated pathway might be fully compensated by OX2R-mediated pathways without a contribution of OX1R. Considering the fact that OX2R−/− show a mild but definite narcoleptic phenotype, OX2R-mediated pathways other than histaminergic pathways might be highly important for basal regulation of sleep/wake states.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Wendy Gray for critical reading the manuscript. This study was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (S, A, B) and the 21st Century COE Program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan, Mitsui Life Social Welfare Foundation, Takeda Science Foundation.

References

- Akiyama M, Yuasa T, Hayasaka N, Horikawa K, Sakurai T, Shibata S. Reduced food anticipatory activity in genetically orexin (hypocretin) neuron-ablated mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:3054–3062. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Centurion C, Gerashchenko D, Shiromani PJ. Effects of saporin-induced lesions of three arousal populations on daily levels of sleep and wake. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14041–14048. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3217-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouthenet ML, Ruat M, Sales N, Garbarg M, Schwartz JC. A detailed mapping of histamine H1-receptors in guinea-pig central nervous system established by autoradiography with [125I]iodobolpyramine. Neuroscience. 1988;26:553–600. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B, Kenny PJ, Specio SE, Martin-Fardon R, Markou A, Koob GF, De Lecea L. Role for hypocretin in mediating stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:19168–19173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507480102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Sergeeva OA, Eriksson KS, Haas HL. Convergent excitation of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons by multiple arousal systems (orexin/hypocretin, histamine and noradrenaline) J Neurosci. 2002;22:8850–8859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08850.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlet S, Tyler CJ, Leonard CS. Direct and indirect excitation of laterodorsal tegmental neurons by hypocretin/orexin peptides: implications for wakefulness and narcolepsy. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2862–2872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02862.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell TE, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson KS, Sergeeva O, Brown RE, Haas HL. Orexin/hypocretin excites the histaminergic neurons of the tuberomammillary nucleus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9273–9279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09273.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G. A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature. 2005;437:556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature04071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZL, Mochizuki T, Qu WM, Hong ZY, Watanabe T, Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Altered sleep-wake characteristics and lack of arousal response to H3 receptor antagonist in histamine H1 receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4687–4692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600451103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZL, Qu WM, Li WD, Mochizuki T, Eguchi N, Watanabe T, Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Arousal effect of orexin A depends on activation of the histaminergic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9965–9970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181330998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue I, Yanai K, Kitamura D, Taniuchi I, Kobayashi T, Niimura K, Watanabe T, Watanabe T. Impaired locomotor activity and exploratory behavior in mice lacking histamine H1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13316–13320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkova TM, Sergeeva OA, Eriksson KS, Haas HL, Brown RE. Excitation of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic and nondopaminergic neurons by orexins/hypocretins. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00007.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JS, Sakai K, Jouvet M. Hypothalamo-preoptic histaminergic projections in sleep-wake control in the cat. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:618–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JS, Hou Y, Sakai K, Jouvet M. Histaminergic descending inputs to the mesopontine tegmentum and their role in the control of cortical activation and wakefulness in the cat. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1523–1537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-04-01523.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qiu X, De Jong PJ, Nishino S, Mignot E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:6–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Mir MI, Pollard H, Moreau J, Arrang JM, Ruat M, Traiffort E, Schwartz JC, Palacios JM. Three histamine receptors (H1, H2 and H3) visualized in the brain of human and non-human primates. Brain Res. 1990;526:322–327. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91240-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mieda M, Williams SC, Sinton CM, Richardson JA, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M. Orexin neurons function in an efferent pathway of a food-entrainable circadian oscillator in eliciting food-anticipatory activity and wakefulness. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10493–10501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3171-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti J. Involvement of histamine in the control of the waking state. Life Sci. 1993;53:1331–1338. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90592-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti JM, Pellejero T, Jantos H. Effects of H1- and H2-histamine receptor agonists and antagonists on sleep and wakefulness in the rat. J Neural Transm. 1986;66:1–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01262953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Nagumo Y, Hashimoto S, Narita M, Khotib J, Miyatake M, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Nakamachi T, Shioda S, Suzuki T. Direct involvement of orexinergic systems in the activation of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway and related behaviors induced by morphine. J Neurosci. 2006;26:398–405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2761-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AN, Pascoe PA, Stone BM. Histaminergic systems and sleep. Studies in man with H1 and H2 antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 1985;24:245–250. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panula PYH, Costa E. Histamine-containing neurons in the rat hypothalamus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2572–2576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier R, Ohtsu H, Djebbara-Hannas Z, Valatx JL, Watanabe T, Lin JS. Anatomical, physiological, and pharmacological characteristics of histidine decarboxylase knock-out mice: evidence for the role of brain histamine in behavioral and sleep-wake control. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7695–7711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07695.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, Ripley B, Overeem S, Charnay Y, Nevsimalova S, Aldrich M, Reynolds D, Albin R, et al. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat Med. 2000;9:991–997. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, El Mansari M, Lin JS, Zhang JG, Vanni Mercier G. The posterior hypothalamus in the regulation of wakefulness and paradoxical sleep. In: Mancia M, Marini G, editors. The Diencephalon and Sleep. Raven Press; New York: 1990. pp. 171–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T. The neural circuit of orexin (hypocretin): maintaining sleep and wakefulness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:171–181. doi: 10.1038/nrn2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Nagata R, Yamanaka A, Kawamura H, Tsujino N, Muraki Y, Kageyama H, Kunita S, Takahashi S, Goto K, Koyama Y, Shioda S, Yanagisawa M. Input of orexin/hypocretin neurons revealed by a genetically encoded tracer in mice. Neuron. 2005;46:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto Y, Fujii Y, Shinomiya K, Kamei C. Participation of histaminergic H1 and noradrenergic alpha 1 receptors in orexin A-induced wakefulness in rats. Brain Res. 2004;1023:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Inagaki S, Taguchi Y, Tohyama M, Watanabe T, Wada H. Origins of histamine-containing fibers in the cerebral cortex of rats studied by immunohistochemistry with histidine decarboxylase as a marker and transection. Brain Res. 1984;323:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasaka K, Chung YH, Sawada K. Excitatory effect of histamine on EEGs of the cortex and thalamus in rats. Agents Actions. 1989;27:127–130. doi: 10.1007/BF02222218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000;27:469–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanni-Mercier G, Sakai K, Jouvet M. Specific neurons for wakefulness in the posterior hypothalamus in the cat. C R Acad Sci III. 1984;298:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Taguchi Y, Shiosaka S, Tanaka J, Kubota H, Terano Y, Tohyama M, Wada H. Distribution of the histaminergic neuron system in the central nervous system of rats; a fluorescent immunohistochemical analysis with histidine decarboxylase as a marker. Brain Res. 1984;295:13–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90811-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Yanagisawa M. To eat or to sleep? Orexin in the regulation of feeding and wakefulness. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:429–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Tokita S, Williams SC, Kisanuki YY, Marcus JN, Lee C, Elmquist JK, Kohlmeier KA, Leonard CS, Richardson JA, Hammer RE, Yanagisawa M. Distinct narcolepsy syndromes in Orexin receptor-2 and Orexin null mice: molecular genetic dissection of Non-REM and REM sleep regulatory processes. Neuron. 2003;38:715–730. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A, Tsujino N, Funahashi H, Honda K, Guan JL, Wang QP, Tominaga M, Goto K, Shioda S, Sakurai T. Orexins activate histaminergic neurons via the orexin 2 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:1237–1245. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka A, Beuckmann CT, Willie JT, Hara J, Tsujino N, Mieda M, Tominaga M, Yagami K, Sugiyama F, Goto K, Yanagisawa M, Sakurai T. Hypothalamic orexin neurons regulate arousal according to energy balance in mice. Neuron. 2003;38:701–713. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Mccormack S, Espana RA, Crocker A, Scammell TE. Afferents to the orexin neurons of the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:845–861. doi: 10.1002/cne.20859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]