Abstract

Auxin is transported across the plasma membrane of plant cells by diffusion and by two carriers operating in opposite directions, the influx and efflux carriers. Both carriers most likely play an important role in controlling auxin concentration and distribution in plants but little is known regarding their regulation. We describe the influence of modifications of the transmembrane pH gradient and the effect of agents interfering with protein synthesis, protein traffic, and protein phosphorylation on the activity of the auxin carriers in suspension-cultured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) cells. Carrier-mediated influx and efflux were monitored independently by measuring the accumulation of [14C]2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and [3H]naphthylacetic acid, respectively. The activity of the influx carrier decreased on increasing external pH and on decreasing internal pH, whereas that of the efflux carrier was only impaired on internal acidification. The efflux carrier activity was inhibited by cycloheximide, brefeldin A, and the protein kinase inhibitors staurosporine and K252a, as shown by the increased capability of treated cells to accumulate [3H]naphthylacetic acid. Kinetics and reversibility of the effect of brefeldin A were consistent with one or several components of the efflux system being turned over at the plasma membrane with a half-time of less than 10 min. Inhibition of efflux by protein kinase inhibitors suggested that protein phosphorylation was essential to sustain the activity of the efflux carrier. On the contrary, the pharmacological agents used in this study failed to inhibit [14C]2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid accumulation, suggesting that rapidly turned-over proteins or proteins activated by phosphorylation are not essential to carrier-mediated auxin influx. Our data support the idea that the efflux carrier in plants constitutes a complex system regulated at multiple levels, in marked contrast with the influx carrier. Physiological implications of the kinetic features of this regulation are discussed.

Auxin transport is essential at any stage of plant development to ensure coordinated growth at the organ and cellular levels and to provide the capacity to respond to environmental stimuli (Lomax et al., 1995, and refs. therein). Active auxin transport in plant cells is mediated by two carriers of the PM acting in opposite directions (Rubery, 1987; Lomax et al., 1995). The influx carrier, the physiological function of which at the integrated levels of organs or the whole plant is unknown, imports hormones from the surrounding medium. The efflux carrier excretes hormones out of cells and is believed to be responsible for polar auxin transport in plants. A number of auxin-binding polypeptides have been identified in PM preparations using photoaffinity-labeling techniques, and are assumed to be involved in carrier-mediated auxin influx (Lomax and Hicks, 1992; Hicks et al., 1993) and efflux (Feldwisch et al., 1992; Zettl et al., 1992) on the basis of their binding specificity and physicochemical properties. Furthermore, the AUX1 gene product, involved in the auxin control of root gravitropism in Arabidopsis thaliana exhibits sequence similarity to amino acid permeases and might mediate auxin influx (Bennet et al., 1996).

What is known about the biochemical aspects of the regulation of auxin transport mainly concerns efflux and the effect of synthetic inhibitors, phytotropins such as NPA (Rubery, 1990; Lomax et al., 1995). Several lines of evidence indicate that the auxin efflux carrier is probably a multicomponent system (Rubery, 1987; Morris et al., 1991; Lomax et al., 1995). Phytotropins bind to a PM protein, the nature of which, integral (Bernasconi et al., 1996) or peripheral (Cox and Muday, 1994), is yet to be determined. On the basis of experiments using cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, it has been proposed (Morris et al., 1991) that the NPA-binding and auxin efflux sites are harbored on distinct proteins, with a third short-lived polypeptide transducing the phytotropin signal to the catalytic unit of auxin transport.

A recent study (Wilkinson and Morris, 1994) has shown that monensin, an inhibitor that disrupts protein traffic from the Golgi apparatus to the cell surface, increased the accumulation and reduced the efflux rate of [3H]IAA in zucchini (Cucurbita pepo L.) hypocotyl fragments. Results were interpreted as indicating that one or several components of the efflux carrier, not obviously connected to the NPA-binding transduction pathway, are rapidly turned over at the PM. Two reports (Bernasconi, 1996; Garbers et al., 1996) suggest that phytotropins might increase the phosphorylation status of the transport system. A possible role of protein Tyr kinase has been proposed for the phytotropin-binding protein because inhibitors of Tyr kinase activity antagonized NPA-induced inhibition of auxin efflux in zucchini hypocotyl segments (Bernasconi, 1996). However, the rcn1 mutation, which increases the sensitivity of auxin efflux to NPA in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings, was shown to interrupt a gene that encodes a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (Garbers et al., 1996).

Our concern has been to investigate auxin transport regulation with the purpose of describing the characteristics of each carrier. We showed previously (Delbarre et al., 1996) that the activities of the influx and efflux carriers in suspension-cultured cells can be distinguished by monitoring the 30-s accumulation of the labeled synthetic auxins 2,4-D and 1-NAA. The uptake of 2,4-D is mostly ensured by the influx carrier, as it is not secreted by the efflux carrier. However, 1-NAA enters cells mainly by diffusion and has its accumulation level controlled by the efflux carrier. The method affords the possibility of probing separately the effect of any drug or treatment on the activity of the influx or the efflux carrier and overcomes several of the difficulties encountered when using labeled IAA, which is a substrate for both.

Here we describe the influence of a change in the ΔpH and the effect of a treatment with BFA, a reversible inhibitor of protein traffic, CHI, and different inhibitors of protein kinases and PP1 and PP2A on the capability of suspension-cultured tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) cells to accumulate [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA. Carrier-mediated auxin influx and efflux differed in their sensitivity to a reduction in ΔpH, depending on whether ΔpH was manipulated by increasing pHe or decreasing pHc, and differed in their response to a treatment with BFA, CHI, and the protein kinase inhibitors staurosporine and K252a. Kinetics measured for the inhibition of [3H]NAA efflux by inhibitors of protein traffic and secretion provided insight regarding turnover of the efflux components. It has been reported that NPA inhibits auxin efflux through increased protein phosphorylation (Bernasconi, 1996). We now present evidence that increased protein phosphorylation is also essential to sustain auxin efflux. This study supports the idea that auxin efflux in plants, in contrast with influx, is mediated by a highly regulated complex involving rapidly turned-over components and several layers of control by protein phosphorylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Chemicals were purchased from Aldrich or Sigma and were of an analytical grade. Tritiated Leu (l[4, 5-3H]Leu; 2.4 to 3.1 × 103 TBq mol−1) was purchased from Amersham and ICN. Labeled 2,4-D ([14C]2,4-D; 2.07 TBq mol−1) and labeled BA ([14C]BA; 2.1 TBq mol−1) were obtained from Amersham and CEA (Gif-sur-Yvette, France), respectively. Tritiated 1-NAA ([3H]NAA; 314 TBq mol−1) was synthesized as described by Delbarre et al. (1994).

Plant Material

Cells of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv Xanthi XHFD8; Muller et al., 1985) were grown under continuous light and 21°C in B5 Gamborg medium (Gamborg et al., 1968) containing 1 μm 2,4-D and 60 nm kinetin. Stock suspensions were subcultured every 7 d at a density of 15 and 30 mg mL−1.

Cell Preparation

In most experiments cells were equilibrated in a buffer (uptake buffer) containing 10 mm Suc, 0.5 mm CaSO4, and 20 mm Mes and adjusted to pH 5.7 by KOH. In the experiments designed for exploring the effects of increasing pHe, Mes concentration in the buffer was lowered to 1 mm (low-Mes uptake buffer). Exponential phase cells from a 100-mL stock suspension were filtered, resuspended in the same volume of uptake buffer (or low-Mes uptake buffer), and shaken for 45 min. The washing procedure was repeated once. Afterward, the medium was decanted off, the culture was topped up with fresh uptake buffer (or low-Mes uptake buffer) to obtain a density of 75 to 100 mg cells mL−1, and cells were allowed to equilibrate for not less than 90 min before being used.

Measurement of Diffusive and Carrier-Mediated Auxin Transport in Cells

The method for measuring the activity of the auxin influx and efflux carriers by monitoring the accumulation of tracer concentrations of [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA in suspension-cultured cells was described by Delbarre et al. (1996). One-hundred-fifty to 200 mg of cells was incubated for a short period (usually 30 s) in the presence of [14C]2,4-D (40–120 nm) or [3H]NAA (10–40 nm) plus or minus 50 μm the same unlabeled auxin. Afterward, cells were separated from the medium by draining the suspension onto GFC glass fiber filters (Whatman) without rinsing. The cell pellet was weighed and ethanol extracted for 30 min at room temperature. Auxin accumulation was given as the ratio (accumulation ratio) of the radioactivity retained per unit weight of cells (becquerels per milligram) to the radioactivity per unit volume of incubation medium (becquerels per microliter). The measured radioactivity corresponded to free auxin, since [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA are not metabolized in tobacco cells during short incubations (Delbarre et al., 1996).

Activities of the influx and efflux carriers were deduced from the saturable accumulation components computed for [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA, respectively, by subtracting the nonsaturable accumulation, measured in the presence of 50 μm unlabeled 2,4-D or 1-NAA, from that measured in its absence. For simplification, nonsaturable accumulation is referred to in the text as diffusive accumulation, although it actually corresponds to tracer molecules accumulated by diffusion and contained in the small volume of incubation medium entrapped inside the cell pellet (approximately 0.23 μL mg−1 tobacco cells; Delbarre et al., 1996). In some instances (see below) the diffusive part of nonsaturable accumulation had to be accurately estimated. The radioactivity associated with the contaminating medium was determined by measuring accumulation between 10 and 30 s of incubation and extrapolating to time zero of incubation. Actual diffusion was calculated by subtracting the zero values from the measured values.

Effects of External and Internal pH Changes on Auxin Transport

Different values of pHe were obtained by mixing 2 mL of cell suspension in low-Mes uptake buffer with 4 mL of uptake buffer adjusted to the desired pH between 4.3 and 7.2 and containing labeled plus or minus unlabeled auxin. pHi was decreased by preincubating cells (150–200 mg in 3.8 mL of uptake buffer at pH 5.7) for 5 min (including auxin treatment) in the presence of various concentrations of potassium propionate before adding 200 μL of labeled plus or minus unlabeled auxin and monitoring accumulation. Well-buffered uptake medium prevented pHe from increasing despite the diffusive entry of PAH into cells. In both series of experiments, auxin accumulation was monitored as described above and corrected for the radioactivity contained in the medium contaminating the cell pellet.

Effects of Pharmacological Agents on the Activity of the Auxin Carriers

Tobacco cells were preincubated in the presence of the pharmacological agent to be tested or the organic solvents ethanol or DMSO (maximum 0.1% by volume), which were used to solubilize the agent (control experiments). At intervals, 2-mL samples were pipetted and added to 2 mL of uptake buffer containing labeled plus or minus unlabeled auxin, and then auxin accumulation was measured as described above. Accumulations were uncorrected for contamination by external auxin, except when drug and pH effects had to be compared.

Inhibition-Recovery Experiments with BFA

The cell suspension (150 mL) was incubated in the presence of 25 μm BFA (43 mm stock solution in ethanol). At intervals from the beginning of exposure, cells were probed for their capability to accumulate [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA. After a 40-min treatment, the suspension was filtered, washed twice in 200 mL of fresh uptake buffer (for 3 min), and resuspended in 80 mL of buffer. Auxin accumulation was monitored for an additional 30 min. Control cells, processed in the same conditions, were treated with ethanol (0.6 μL mL−1) instead of BFA.

Kinetics of [3H]Leu Incorporation into Cell Proteins

Cells were equilibrated in Suc-free uptake buffer at a density of 50 mg mL−1. The labeling reaction was initiated by adding 25 nm of isotopically diluted [3H]Leu (2.2 KBq mL−1) into the cell suspension. At intervals during a 70-min period, 1 mL of the suspension was pipetted, mixed with 0.5 mL of 40% TCA, and left overnight at 4°C. After elimination of the supernatant, cells were washed three times with 1 mL of cold 80% acetone. The radioactivity in the pellet was counted by liquid scintillation with quenching correction.

Effects of Pharmacological Agents on Protein Biosynthesis and Secretion

Two protein-labeling procedures were used in parallel to explore the effects of BFA, CHI, and staurosporine on protein synthesis and secretion. In procedure 1, the drug was injected into the cell suspension (500 mg of cells in 5 mL of Suc-free uptake buffer) 20 min before [3H]Leu (9.3–24.2 KBq mL−1; 3–8 nm) was added. Incubation was allowed to proceed for an additional 10 min, and then labeling was arrested with 1 mm unlabeled Leu. Cells were harvested by filtration and resuspended in 5 mL of ice-cold 1 m NaCl for 1 h to remove proteins entrapped in or loosely bound to the cell walls. After grinding in liquid nitrogen, the NaCl-washed cells were extracted overnight in 1.5 mL of acetic acid-saturated aqueous phenol (Appligene Oncor, Illkirch, France) mixture (1:3, v/v) at room temperature. The insoluble pellet was twice washed with 1.5 mL of acetic acid-phenol mixture and three times with 2 mL of water. Intracellular proteins were precipitated from the aqueous and organic phases by using cold 10% TCA in the presence of 3 mg of BSA. Nonincorporated [3H]Leu was eliminated by successively dissolving the TCA pellet in 1 n NaOH (250 μL) and reprecipitating proteins twice with 10% TCA (10 mL). The final pellet was resolubilized in 250 μL of 1 n NaOH and radioactivity was counted by liquid scintillation. Secreted proteins were recovered from the incubation and washing filtrates using TCA precipitation. In procedure 2, cells were supplemented with [3H]Leu plus, 10 min later, 1 mm unlabeled Leu and the drug to be tested. After 30 min of treatment, cells were collected by filtration, secreted, and then cellular proteins were processed as in procedure 1. For the experiments that were conducted in Suc-free uptake buffer, it was checked that the inhibitory effects of BFA and staurosporine on [3H]NAA accumulation were unmodified by the absence of Suc from the buffer.

RESULTS

Influence of ΔpH Changes on Membrane Auxin Transport

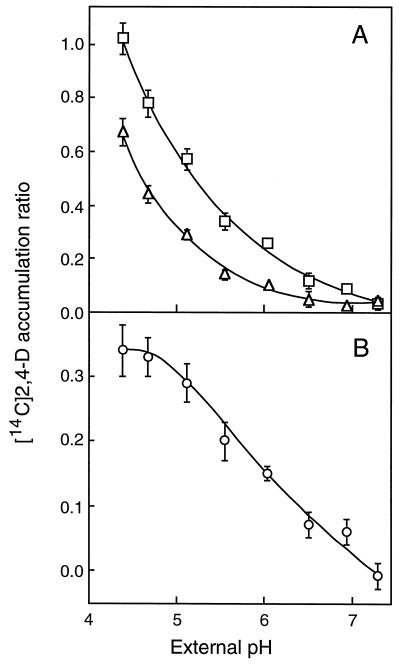

Accumulation of [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA was monitored in conditions reducing ΔpH, namely a pH jump in the uptake medium and intracellular acidification by acid-load effect. In one series of experiments, suspension-cultured tobacco cells, pre-equilibrated at pH 5.7, were transferred into uptake solutions buffered at different pH values between 4.3 and 7.2 and immediately probed for their ability to accumulate [14C]2,4-D (Fig. 1) and [3H]NAA (Fig. 2). This treatment allows ΔpH changes without modifying intracellular pH (approximately 7.5), at least in the short term (Mathieu et al., 1996a). At all of the pHe values, [14C]2,4-D accumulated less in the presence than in the absence of 50 μm 2,4-D (Fig. 1A) because the influx carrier was saturated by external, unlabeled auxin molecules (Delbarre et al., 1996). In the presence and absence of 2,4-D, however, [14C]2,4-D accumulation decreased between pHe 4.3 and 7.2 (Fig. 1A), down to the limit of detectability when ΔpH was collapsed, indicating that diffusive (Fig. 1A) and carrier-mediated (Fig. 1B) entries were both impeded on increasing pHe. However, the influx carrier activity was less sensitive than diffusion to medium alkalization, since 35% of the tracer molecules entered the cells via the saturable influx component at pH 4.3 and more than 60% at pH 6.5.

Figure 1.

Effects of external pH changes on the accumulation of [14C]2,4-D in suspension-cultured tobacco cells. A, Total (□) and diffusive (▵) [14C]2,4-D accumulations were measured in the absence and in the presence of unlabeled 2,4-D, respectively. B, The saturable influx component (○) was calculated by subtracting the diffusive from the total accumulation measured at the same pHe. Two milliliters of a cell suspension (150–200 mg), pre-equilibrated in low-Mes uptake buffer (1 mm Mes) at pH 5.7, was injected into 4 mL of uptake buffer (20 mm Mes) adjusted at the indicated pHe and containing [14C]2,4-D (50 nm final concentration) plus or minus unlabeled 2,4-D (50 μm final concentration). The suspension was filtered after 30 s of incubation and the radioactivity was counted in the cell cake. Values, expressed as accumulation ratios, were corrected for contamination by the incubation medium as described in Methods. Results are means ± se of values obtained in three independent experiments, each in triplicate.

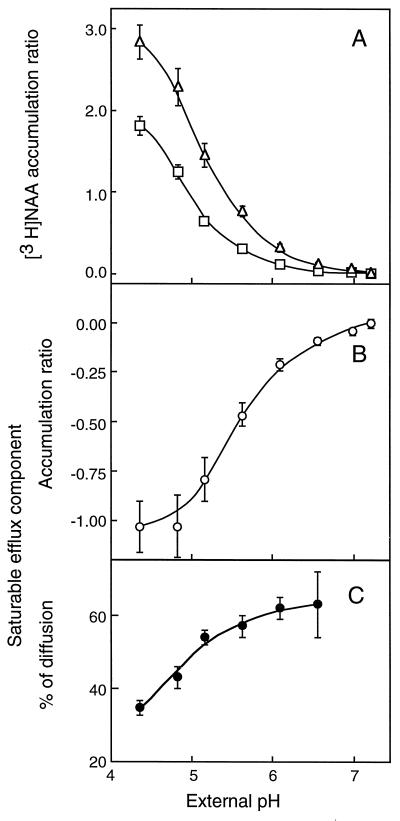

Figure 2.

Effects of changes in pHe on the accumulation of [3H]NAA (11 nm) in tobacco cells. The experimental procedure was the same as given in Figure 1. A, Total (□) and diffusive (▵) [3H]NAA accumulations were measured in the absence and in the presence of 50 μm unlabeled 1-NAA, respectively. B, Saturable accumulation (○) was calculated by subtracting the diffusive from the total accumulation measured at the same pHe. Negative values result from total [3H]NAA accumulation being lower than diffusion due to the activity of the efflux carrier. C, The saturable efflux component (•) was divided by the diffusive accumulation measured at the same pHe and expressed in percent (absolute value) of diffusion. Results are means ± se of values obtained in three independent experiments, each in triplicate.

In contrast to [14C]2,4-D, net [3H]NAA uptake was increased on addition of 50 μm 1-NAA in the incubation medium (Fig. 2A) because the efflux carrier, owing to isotopic dilution of the tracer, was mostly engaged with unlabeled auxin molecules (Delbarre et al., 1996). Total and diffusive [3H]NAA accumulations (Fig. 2A) and the saturable efflux component (Fig. 2B) were progressively abolished on medium alkalization. The possibility existed that the efflux component might decline on increasing pHe because less auxin was supplied inside of the cells. The quantity of [3H]NAA transported per unit time through the efflux carrier is proportional to the intracellular concentration of the tracer (the carrier was far from being saturated in the conditions of low auxin concentration used in the experiments), which in turn depends on the quantity that has entered cells by diffusion. For that reason, the saturable efflux component was divided by the value of diffusion, measured at the same pHe, to take into account the availability of intracellular auxin. Corrected by diffusion (Fig. 2C), the efflux component displayed a slightly positive trend with pHe, indicating that the catalytic function of the efflux carrier was not inhibited by an increase of at least 6.5 in external pH.

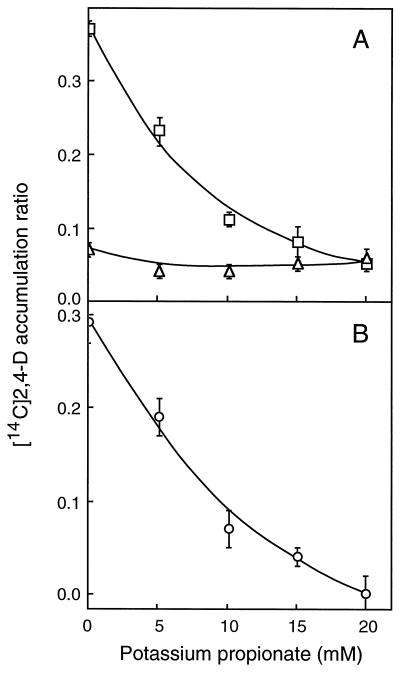

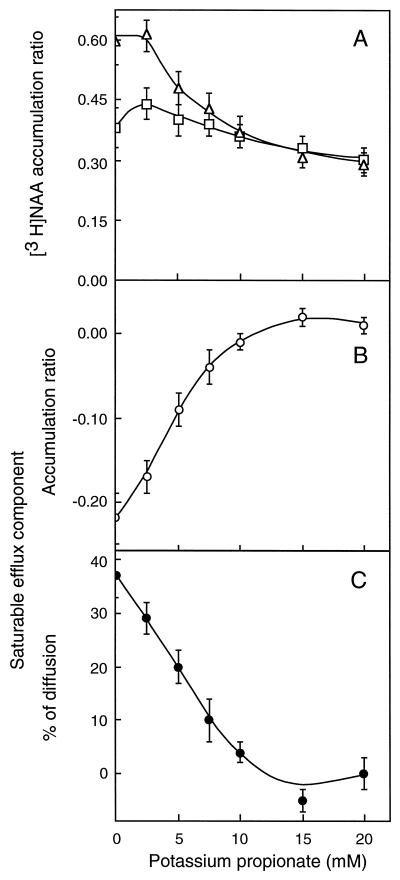

Loading cells with lipophilic weak acids is a convenient and efficient way of reducing intracellular pH (Guern et al., 1991). Tobacco cells were preincubated for 5 min with increasing concentrations of potassium propionate (pK 4.8) before being probed for their capability to accumulate [14C]2,4-D (Fig. 3) and [3H]NAA (Fig. 4) in 30 s. Up to 20 mm, propionate had no significant effect on the net diffusive uptake of [14C]2,4-D (Fig. 3A). Yet, the treatment provoked a strong decrease in pHi, as observed by Mathieu et al. (1996a) in the same cell line, since the diffusive accumulation of [3H]NAA (Fig. 4A) and [14C]BA (not shown) was reduced 2- to 3-fold in the same concentration range. Propionate reduced the carrier-mediated influx of [14C]2,4-D (Fig. 3B) by 50% at 7.5 mm (approximately 0.8 mm PAH) and in totality at 20 mm (approximately 2.2 mm PAH), as well as the carrier-mediated efflux of [3H]NAA, whether this latter component was uncorrected (Fig. 4B) or corrected (Fig. 4C) by diffusion to account for decreasing tracer accumulation. At 10 mm external propionate (approximately 1.1 mm PAH), whereas diffusion had reached a constant level (Fig. 4B), the efflux carrier activity was completely abolished (Fig. 4C).

Figure 3.

Effects of propionic acid loading on the accumulation of [14C]2,4-D in suspension-cultured tobacco cells. A, Total (□) and diffusive (▵) [14C]2,4-D accumulations were measured in the absence and in the presence of unlabeled 2,4-D, respectively. B, The saturable influx component (○) was calculated by subtracting the diffusive from the total accumulation measured for the same acid load. Cells (150–200 mg in 3.8 mL of uptake buffer) were treated for 4.5 min with increasing concentrations of potassium propionate at pH 5.7 and then supplemented with 200 μL of [14C]2,4-D (71 nm final concentration) plus or minus unlabeled 2,4-D (50 μm final concentration). Auxin accumulation was monitored in 30 s and values were corrected for contamination by the incubation medium. Results are means ± se of values obtained in two independent experiments, each in triplicate.

Figure 4.

Effects of propionic acid loading on the accumulation of [3H]NAA (18 nm) in tobacco cells. The experimental procedure was the same as given in Figure 3. A, Total (□) and diffusive (▵) [3H]NAA accumulations were measured in the absence and in the presence of 50 μm unlabeled 1-NAA, respectively. B, Saturable accumulation (○) was calculated by subtracting the diffusive from the total accumulation measured for the same acid load. Negative values result from total [3H]NAA accumulation being lower than diffusion due to the activity of the efflux carrier. C, The saturable efflux component (•) was divided by the diffusive accumulation measured for the same acid load and expressed in percent (absolute value) of diffusion. Results are means ± se of values obtained in five independent experiments, each in triplicate.

Effect of BFA on the Activity of the Influx and Efflux Carriers

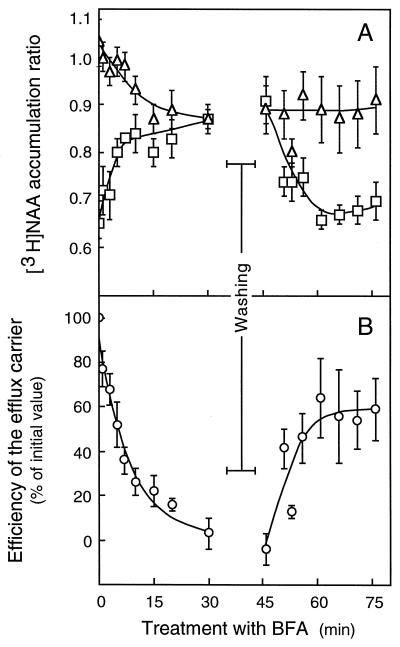

BFA is increasingly used to inhibit protein secretion and to investigate vesicular traffic in plant and animal cells (Satiat-Jeunemaitre et al., 1996). A 60-min pretreatment with 25 μm BFA affected neither component of [14C]2,4-D accumulation in suspension-cultured tobacco cells (Table I). By contrast, BFA-treated cells displayed the same capability to accumulate [3H]NAA, whether accumulation was measured in the absence or in the presence of unlabeled 1-NAA, indicating a complete loss of the efflux carrier activity (Table I). As shown in Figure 5A, 25 μm BFA abolished the saturable efflux component within 30 min, with total [3H]NAA accumulation increasing and diffusive accumulation decreasing to a common level. The efflux carrier activity diminished exponentially (Fig. 5B), with a time constant of 0.12 min−1, corresponding to a t½ value of approximately 6 min for the inhibition. The antibiotic acted in a dose-dependent manner with a 50% inhibition of initial activity value of 3 μm measured after 30 min of contact (not shown). Efflux inhibition was reversible, since [3H]NAA accumulation immediately began to decrease as soon as BFA was eliminated from the medium by extensive washings, proving that the carrier recommenced operation (Fig. 5A). The activity of the efflux carrier rapidly resumed (t½ approximately 5 min), leveling to 60% of its initial value within 30 min after withdrawal of the inhibitor (Fig. 5B).

Table I.

Influence of BFA on the accumulation of [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA

| Component | Accumulation Ratio after 30 s

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Control cells | BFA-treated cells | |

| [14C]2,4-D | ||

| Total accumulation | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.01 |

| Nonsaturable component | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 |

| Saturable component | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.03 |

| [3H]NAA | ||

| Total accumulation | 0.67 ± 0.02 | 0.81 ± 0.02 |

| Nonsaturable component | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.82 ± 0.01 |

| Saturable component | −0.28 ± 0.04a | −0.01 ± 0.02a |

Accumulation of [14C]2,4-D (96–104 nm external concentration) and [3H]NAA (17–27 nm external concentration) was monitored over 30 s in suspension-cultured tobacco cells that had been exposed to 25 μm BFA or ethanol (control cells) for 60 min. Accumulation values were derived from the radioactivity accumulated in cells as described in Methods. Nonsaturable uptake components, corresponding to diffusion, were measured in the presence of 50 μm unlabeled auxin and are uncorrected for contamination by the incubation medium. Saturable components, representing the activity of the influx carrier ([14C]2,4-D accumulation) and that of the efflux carrier ([3H]NAA accumulation), were calculated by subtracting the radioactivity measured in the presence of unlabeled auxin from that measured in its absence (total accumulation). Data, expressed as accumulation ratios, are means ± se of values obtained in two independent experiments, each with three replicates.

Negative values correspond to auxin efflux.

Figure 5.

Time course of and recovery from BFA effect on [3H]NAA accumulation in tobacco cells. A, Cells (75–100 mg mL−1) were treated with 25 μm BFA for 40 min, thoroughly washed, and resuspended at the same density in BFA-free buffer. At the indicated times from the beginning of the treatment, 2-mL aliquot fractions were pipetted and mixed with the same volume of uptake buffer containing [3H]NAA (23–32 nm final concentration) plus or minus unlabeled 1-NAA (50 μm final concentration). Total (□) and diffusive (▵) accumulation ratios were measured after 30 s of incubation, as described in “Materials and Methods,” without correction for contamination by the incubation medium. Results are means ± se of values obtained in four independent experiments. B, The efficiency of the efflux carrier (○) at a given period of treatment was defined as the ratio of the saturable uptake component, calculated by subtracting the total from the diffusive accumulation measured at the same time, to the saturable component calculated prior to BFA addition. Carrier efficiencies are means ± se of values computed from the experiments depicted in A. Experimental values, determined between 0 and 30 min of treatment, were adjusted to a single-exponential function. The solid line represents the best fit obtained by using a time constant of 0.117 ± 0.011 min−1 (t½= 5.9 min).

The data strongly suggested that BFA interfered with [3H]NAA accumulation by specifically impairing the activity of one or several short-lived components that are essential to auxin efflux. Although BFA triggered ΔpH reduction in tobacco cells, as indicated by the decreased capability of the treated cells to passively accumulate [3H]NAA as compared with control cells (Table I; Fig. 5A), efflux carrier inhibition probably did not arise from this nonspecific effect. BFA blocked efflux without altering influx, whereas both carriers were inhibited to the same extent on ΔpH reduction. The activity of the efflux carrier rapidly resumed after BFA was withdrawn, whereas ΔpH did not immediately recover its initial value, as shown by the constant trend of [3H]NAA diffusion with time (Fig. 5A).

Effect of CHI on the Activity of the Influx and Efflux Carriers

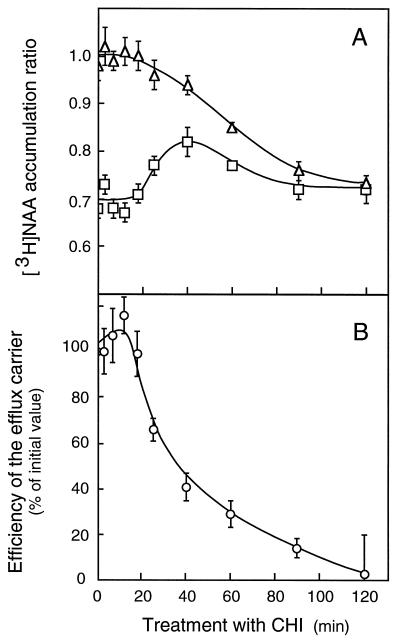

Injection of 10 μm cycloheximide into the culture medium of tobacco cells blocked the protein incorporation of [3H]Leu within less than 1 min (not shown), showing that the inhibitor reached its target rapidly. If treated by 10 μm CHI for less than 20 min, cells displayed a constant capability to accumulate [3H]NAA in the presence and absence of 1-NAA (Fig. 6A), and thus a constant capability to actively excrete auxin (Fig. 6B). A further treatment with CHI reduced the diffusive accumulation component (Fig. 6A), as though the inhibitor triggered internal acidification, moderately for up to 40 min and then increasingly on longer incubations. The level of [3H]NAA accumulation, increasing between 20 and 40 min of exposure and decreasing afterward, came closer to diffusion (Fig. 6A), evidence of a progressive diminution of the saturable efflux component, which was completely inhibited after 2 h of treatment (Fig. 6B). In contrast to what was observed with [3H]NAA, CHI had a limited effect on [14C]2,4-D accumulation, with diffusive and saturable influx components being 93 and 89% of the values measured in control cells after a 30-min treatment and 89 and 60% of these control values after a 90-min treatment.

Figure 6.

Time course of the effect of CHI on [3H]NAA accumulation in tobacco cells. A, Cells (75–100 mg mL−1) were incubated with 10 μm CHI in uptake buffer. At the indicated times, [3H]NAA accumulation (15–19 nm) was monitored as described in Figure 5. Total (□) and diffusive (▵) accumulation ratios, measured after 30 s of incubation, were not corrected for contamination by the incubation medium. Results are means ± se of values obtained in three independent experiments, each in triplicate. B, The carrier efficiency (○) was defined as in Figure 5B. Results are means ± se of values computed from the experiments depicted in A.

Effect of Protein Kinase Inhibitors on the Activity of the Influx and Efflux Carriers

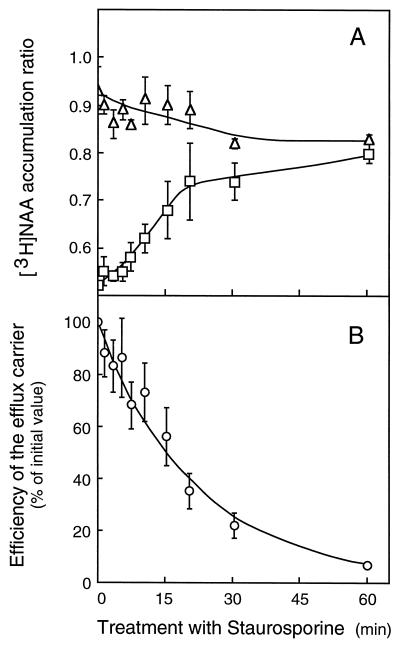

Staurosporine, a natural antibiotic exhibiting broad specificity for inhibiting protein kinases (Hidaka and Kobayashi, 1993), strongly decreases protein phosphorylation in suspension-cultured tobacco cv XHFD8 cells (Mathieu et al., 1996b). Treated by 1 μm staurosporine, tobacco cells displayed the capability to accumulate [3H]NAA, increasing with the duration of the drug contact (Table II; Fig. 7A) and overtaking the diffusion level in 60 min. The efflux carrier activity, declining progressively with increasing exposure to staurosporine (Fig. 7B), was half-inhibited in approximately 16 min. It was unlikely that efflux inhibition resulted from unspecific effects such as ΔpH reduction, since staurosporine did not interfere with the carrier-mediated influx of [14C]2,4-D (Table II). The inhibition more likely indicated that one or several components of the efflux carrier system required activation through increased protein phosphorylation. Other protein kinase inhibitors, K252a, H7 (Hidaka and Kobayashi, 1993), W7 (Hidaka and Kobayashi, 1993), and 6-dimethylaminopurine (Neant and Guerrier, 1988), were assayed on [3H]NAA accumulation to gain insight into kinase(s) involved in the activation of the efflux carrier. After 30 min of pretreatment, the activity of the efflux carrier was almost completely inhibited by 0.5 μm K252a, a molecule chemically related to staurosporine, but was not affected by 15 μm of the protein kinase C inhibitor H7, 15 μm of the calmodulin antagonist W7, or 250 μm DMAP (Table III).

Table II.

Influence of staurosporine on the accumulation of [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA

| Component | Accumulation Ratio after 30 s

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Control cells | Staurosporine-treated cells | |

| [14C]2,4-D | ||

| Total accumulation | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 0.76 ± 0.02 |

| Nonsaturable component | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.01 |

| Saturable component | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.03 |

| [3H]NAA | ||

| Total accumulation | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.86 ± 0.04 |

| Nonsaturable component | 0.94 ± 0.10 | 0.96 ± 0.05 |

| Saturable component | −0.31 ± 0.08a | −0.10 ± 0.02a |

Accumulation of [14C]2,4-D (93–117 nm external concentration) and [3H]NAA (25–29 nm external concentration) was monitored over 30 s in suspension-cultured tobacco cells that had been exposed to 1 μm staurosporine or DMSO (control cells) for 30 min. Experimental procedure and presentation of results are the same as given in Table I. Data, expressed as accumulation ratios, are means ± se of values obtained in two ([14C]2,4-D accumulation) or five ([3H]NAA accumulation) independent experiments, each with three replicates.

Negative values correspond to auxin efflux.

Figure 7.

Time course of the staurosporine effect on [3H]NAA accumulation in tobacco cells. A, Cells (75–100 mg mL−1) were incubated with 1 μm staurosporine in uptake buffer. At the indicated times from the beginning of the treatment, the 30-s accumulation of [3H]NAA (25–27 nm) was monitored as described in Figure 5. Total (□) and diffusive (▵) accumulation ratios, measured after 30 s of incubation, were not corrected for contamination by the incubation medium. Results are means ± se of values obtained in three independent experiments. B, Carrier efficiencies (○), defined as in Figure 5B, are means (± se) of values obtained in the experiments depicted in A. Experimental values were adjusted to a single-exponential function (solid line) using a time constant of 0.044 ± 0.004 min−1 (t½= 15.8 min).

Table III.

Influence of protein kinase and phosphatase inhibitors on [3H]NAA accumulation

| Treatment

|

[3H]NAA Accumulation

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | Concentration | Duration | Diffusive component | Efflux component |

| μm | h | % control | ||

| Protein kinase | ||||

| Staurosporine (6) | 1 | 0.5 | 102 ± 1 | 32 ± 4 |

| K252a (3) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 98 ± 2 | 38 ± 8 |

| H7 (3) | 15 | 0.5 | 102 ± 5 | 104 ± 5 |

| W7 (3) | 15 | 0.5 | 109 ± 2 | 110 ± 14 |

| DMAPa(4) | 250 | 0.5 | 109 ± 4 | 84 ± 9 |

| Protein phosphatase | ||||

| Calyculin A (2) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 95 ± 1 | 43 ± 5 |

| Cantharidin (7) | 50 | 1 | 76 ± 2 | 23 ± 5 |

| Microcystin-LR (3) | 1 | 1 | 104 ± 3 | 105 ± 4 |

| Okadaic acid (2) | 0.75 | 1 | 95 ± 1 | 89 ± 10 |

Tobacco cells were incubated for the indicated times with inhibitors or the organic solvent (DMSO or ethanol) used to solubilize inhibitors (control cells). The 30-s accumulation of [3H]NAA (19–37 nm external concentration) was monitored as described in “Materials and Methods,” the diffusive component being measured in the presence of 50 μm unlabeled 1-NAA and uncorrected for contamination by the incubation medium. The carrier-mediated component was calculated by subtracting the radioactivity measured in the absence of unlabeled auxin from the diffusive component. Data are means ± se of values obtained in the number of independent experiments given in parentheses, each with three replicates.

DMAP, 6-Dimethylaminopurine.

Effect of Staurosporine on Protein Synthesis and Secretion

Staurosporine (1 μm) was assayed on the 10-min incorporation of [3H]Leu into newly synthesized and secreted proteins in comparison with CHI (10 μm) and BFA (25 μm). In procedure 1, [3H]Leu incorporation into newly synthesized proteins was quantified in cells that had been exposed to drugs for 30 min (see Methods). Protein synthesis was almost completely inhibited by CHI, unaffected by BFA, and slightly increased by staurosporine (Table IV). In procedure 2, designed for monitoring protein secretion, cells received a 10-min pulse of [3H]Leu and then were supplemented with an excess of unlabeled Leu and treated with drugs for an additional 30 min (see Methods). About 1.5 to 2.5% of the total labeled proteins were secreted to the medium (Table IV). BFA inhibited protein secretion by approximately one-third, in contrast to CHI and staurosporine, which were both inactive (Table IV).

Table IV.

Effect of CHI, BFA, and staurosporine on protein biosynthesis and secretion in tobacco cells

| Procedure | Controls | Treated Cells

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 μm CHI | 25 μm BFA | 1 μm Staurosporine | ||

| % of controls | ||||

| 1 | 100 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 99 ± 7 | 127 ± 10 |

| (15.9 ± 2.6 KBq) | ||||

| 2 | 100 | 93 ± 6 | 64 ± 4 | 94 ± 6 |

| (0.27 ± 0.08 KBq)a | ||||

Protein labeling was carried out by incubating cells (100 mg mL−1) with 3 to 8 nm [3H]Leu for 10 min and stopped by addition of 1 mm unlabeled Leu. Inhibitors were added 20 min prior to (procedure 1) or immediately after (procedure 2) the pulse-chase sequence and were maintained in contact with cells for 30 min in both procedures. Four series of experiments were run independently, with cells treated by inhibitors and processed in parallel according to both procedures. Data, means ± se of values obtained in the four experiments, represent the radioactivity incorporated into total (procedure 1) and secreted (procedure 2) proteins prepared from treated cells.

Total incorporated [3H]Leu: 11.0 ± 2.3 KBq.

Effect of Inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A on the Activity of the Influx and Efflux Carriers

Tobacco cells were treated with inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A (Smith and Walker, 1996), calyculin A, cantharidin, microcystin-LR, and okadaic acid, before being probed for their capability to accumulate [14C]2,4-D and [3H]NAA. The inhibitors were expected to permeate the PM according to their chemical structure and their ability to elicit rapid defense responses in plant cells (MacKintosh et al., 1994; Mathieu et al., 1996a; Smith and Walker, 1996). Microcystin-LR (1 μm, 60 min) and okadaic acid (0.75 μm, 60 min) did not modify the accumulation of [14C]2,4-D (not shown) or that of [3H]NAA (Table III), whereas calyculin A (0.2 μm, 30 min) and cantharidin (50 μm, 60 min) inhibited the activity of the influx carrier by 16 and 55% (not shown) and that of the efflux carrier by 57 and 77% (Table III). None of these drugs could prevent the effect of staurosporine on the efflux carrier activity even when given 30 min prior to the addition of the protein kinase inhibitor (not shown).

DISCUSSION

Influx and Efflux Carriers React Differently to pHe and pHc Changes

Auxins exist in solution in a pH-dependent equilibrium between undissociated acid, easily diffusing across biological membranes, and dissociated anion. Changes in pHe have been shown to perturb diffusive auxin uptake in the same manner as depicted in Figures 1 and 2, because they modified the extracellular concentration of undissociated molecules able to permeate the PM (Rubery, 1987, and refs. therein). Furthermore, there is evidence that increasing pHe reduced the saturable entry of [14C]2,4-D in suspension-cultured crown gall (Rubery, 1978) and soybean root (Loper and Spanswick, 1991) cells. We report similar inhibitions of the influx carrier activity by pHe in tobacco cells, and we show that the extracellular proton concentration has a limited influence on the efflux carrier activity between pHe 4.3 and 6.5. The effect of a change in pHc on auxin transport has been less documented.

Potassium propionate has been shown to provoke a dose-dependent acidification of the cytosol in suspension-cultured tobacco cells, as shown by 31P-NMR spectroscopy experiments and determination of distribution of [14C]BA (Mathieu et al., 1996a). Cytosolic acidification was maximal after 5 to 10 min of treatment and increased more than 1 pH unit at the highest concentrations used in our work. These data supported the idea that carrier-mediated [14C]2,4-D influx and [3H]NAA efflux decreased in propionate-treated cells in response to a decline in pHc. The effect of propionate on the passive 30-s accumulation of [3H]NAA and [14C]BA indicated a rapid diffusion of accumulated tracers back to the bulk solution. The proportion of undissociated molecules capable of diffusing outward through PM increased with decreasing pHc, amplifying the passive egress and, consequently, diminishing the net uptake of [3H]NAA and [14C]BA. Because of its stronger acidity (pK 2.8) causing higher dissociation, protonated 2,4-D was more than 2 orders of magnitude less accumulated than 1-NAA and BA (pK 4.2). For that reason, there was no significant egress of [14C]2,4-D during the first minutes of incubation. The net passive uptake of [14C]2,4-D, governed in totality by influx, was therefore unmodified by a change in pHc.

Auxin carriers reacted differently to a reduction in ΔpH, depending on the origin of this change. The activity of the influx carrier decreased on increasing pHe and decreasing pHc, whereas that of the efflux carrier was only hampered upon internal acidification. Besides, carriers were inactivated by a 5-min treatment with 10 μm of the uncoupler carbonylcyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (not shown). These results are consistent with a previous hypothesis (for reviews, see Rubery, 1987; Lomax et al., 1995) proposing that auxin is co-transported with one or two protons by the influx carrier and excreted as an anion by the efflux carrier. Owing to their difference in pH sensitivity, carriers might provide plant cells with the capacity of modulating the effect of a stimulus eliciting ΔpH modifications (light, phytohormone, or elicitor; Felle 1989; Mathieu et al., 1994) on auxin exchanges. A change in pHe has additive effects on diffusive and carrier-mediated influx but no direct influence on the efflux carrier activity, whereas a change in pHc interferes with the influx and efflux pathways. Thus, in comparison with a situation in which diffusion only would be operating, variations of auxin transport should be amplified or buffered, depending on whether the stimulus is perturbing extracellular or cytosolic pH.

For the above-mentioned reasons, [3H]NAA was used as a probe for showing that several drugs decreased cytosolic pH in tobacco cells and for determining whether these drugs interfered specifically with carriers or indirectly in perturbing pHc. Inhibition was considered as specific when the activity of one carrier only was abolished by the drug, since the activity of both carriers is impaired upon cytosolic acidification. According to this criterion, BFA, staurosporine, and CHI in the short term were specific inhibitors for the efflux carrier system. Specificity of the inhibition was ascertained when comparing the effects induced by the drug on the auxin transport components with those measured in pH experiments. For instance, 8 to 10 mm potassium propionate was needed to mimic the effect of 25 μm BFA on the efflux carrier activity, whereas one-half of this concentration was sufficient to provoke the same cytosolic acidification triggered by the antibiotic. On the contrary, calyculin A and cantharidin more likely inhibited the activity of the auxin carriers unspecifically in decreasing pHc because both agents strongly reduced diffusion in the same concentration ranges (>0.1 μm calyculin A; >30 μm cantharidin), impairing carrier-mediated influx and efflux. The same decline in carrier activity or in diffusive [3H]NAA uptake was observed when cells were treated with either 50 μm cantharidin or 8 mm potassium propionate.

Rapidly Turned-Over Components Are Involved in Auxin Efflux but Not in Influx

BFA abolished the activity of the auxin efflux carrier in tobacco cells in a specific manner. Because this drug reversibly blocks the secretory pathway from the Golgi to the plant cell surface (Driouich et al., 1993; Satiat-Jeunemaitre and Hawes, 1993; Schindler et al., 1994; Satiat-Jeunemaitre et al., 1996), our data were consistent with one or more proteins of the efflux system being rapidly turned over at the PM, as proposed by Wilkinson and Morris (1994), on the basis of monensin action. By contrast, carrier-mediated auxin influx did not involve rapid protein recycling because BFA had no effect on [14C]2,4-D accumulation. The half-residence time of the BFA-sensitive component(s) of auxin efflux was estimated to be less than 10 min at the tobacco cell surface, in the same order of magnitude as the values found in measuring exocytosis of IAA-inducible H+-ATPases (t½ approximately 12 min) in maize coleoptile tissue (Hager et al., 1991) or calculated for the exchange (20–40 min) of an area equivalent to the whole of PM in secreting plant cells (Robinson and Hillmer, 1990). A 20-min lag phase was observed before the efflux carrier activity begins to decline, when cells were treated by CHI, suggesting that the rapidly turned-over efflux components were targeted to the PM from a preexisting pool rather than being newly synthesized. Between 20 and 40 min of treatment, efflux inhibition probably resulted from a specific effect of CHI on the activity or renewal of component(s) essential to carrier-mediated efflux, since pHc decreased moderately, as evidenced by the small diminution of both [3H]NAA diffusion and [14C]2,4-D influx. On longer treatments, cytosolic acidification was responsible for at least a part of this inhibition.

Cycloheximide interfered with auxin transport much more rapidly in tobacco cells (this work) than in zucchini (Cucurbita pepo L.) hypocotyl segments (Morris et al., 1991), where IAA uptake reduction and intracellular acidification occurred after 2 to 3 h of contact. There is, however, no reason to suppose that tissue and cell systems reacted differently to the translation inhibitor, because the difference in timing might simply originate from an easier penetration of CHI in cell clumps than in compact tissue fragments. Morris et al. (1991) demonstrated that CHI suppressed the stimulation of IAA uptake by NPA without affecting the binding of the phytotropin to microsomal fractions or the efflux carrier activity, at least in the short term. They proposed that the catalytic transport unit on the efflux carrier and the NPA receptor are separate proteins connected by a third labile, transducing protein. This interesting feature was not investigated in the present study.

Auxin Efflux, but Not Influx, Requires Protein Phosphorylation

In this study no evidence has been found that auxin influx in tobacco cells is influenced by any phosphorylation process. On the contrary, carrier-mediated efflux was rapidly abolished by well-known inhibitors of protein phosphorylation, staurosporine and K252a. This effect was imputed to inhibitors interfering with the activity of kinases controlling phosphorylation of one or more proteins essential to efflux. Efflux inhibition did not result from a perturbation of the traffic of the BFA-sensitive carrier components, unless specific kinase(s) or phosphorylated protein(s) were required to ensure a proper targeting of these components to the PM, because staurosporine had no significant effect on protein secretion, which follows the same general vesicular pathway as intracellular protein trafficking in eukaryotic cells (Rothman, 1994). The protein kinases not inactivated by specific inhibitors of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (W7) and protein kinase C (H7) were not further characterized.

Calyculin A and other inhibitors of PP1 and PP2A failed to prevent inhibition of auxin efflux by staurosporine. Phosphorylated proteins were possibly in fast exchange with inactive dephosphorylated proteins within the transport system. If so, the phosphorylation status of the carrier, and consequently its activity, was controlled through opposite actions of protein kinase(s) and phosphatase(s). This simple hypothesis, which implies that the phosphatases controlling efflux display a specificity different from those reported for PP1 and PP2A, could hardly be verified, because the sensitivity of plant protein phosphatases (apart from PP1 and PP2A) to inhibitors is still poorly known (Smith and Walker, 1996). A more attractive hypothesis is based on the possibility of overlapping layers of control of the efflux carrier activity by protein trafficking and phosphorylation. Within this model, short-lived phosphorylated proteins are eliminated from the transport system prior to dephosphorylation. Carrier-mediated efflux is inhibited by BFA and staurosporine, because continuous replacement of phosphorylated proteins is required at the PM surface, but not by inhibitors of protein phosphatases, and because the carrier is inactivated through protein endocytosis and/or degradation before the efflux proteins are dephosphorylated.

The Efflux Carrier Activity Obeys a Complex Regulation Scheme

Little is known about the implication of phosphorylation reactions in the regulation of carrier activity in higher plants (for review, see Tanner and Caspari, 1996). The Tyr kinase inhibitors tyrphostins have been reported to antagonize the effect of NPA on auxin efflux in zucchini hypocotyl segments and to displace phytotropin from its binding protein at the PM, uncovering a possible Tyr kinase function for this protein (Bernasconi, 1996). Garbers et al. (1996) isolated a mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana, designated rcn1, the seedlings of which exhibit altered responses to NPA in root curling and hypocotyl elongation, consistent with an increase in sensitivity to the phytotropin. Because the rcn1 mutation interrupts a gene encoding a regulatory subunit of PP2A (Garbers et al., 1996), this result suggests that protein phosphatase activity is involved in NPA-dependent control of auxin efflux. It is worth noting that basal auxin efflux in tyrphostin-treated tissue fragments and rcn1 mutant seedlings was unmodified as compared with control material. Bernasconi (1996) and Garbers et al. (1996) published evidence that Tyr kinase activity might be at the origin of the inhibitory effect of phytotropin on auxin efflux, whereas we have shown that kinase activity is essential to maintain the activity of the efflux carrier. Thus, auxin efflux in plants is apparently controlled at different levels of protein phosphorylation. Increased phosphorylation promotes the activity of the carrier in the absence of NPA. By contrast, increased phosphorylation, dependent on the interaction between NPA and its binding protein, results in inhibition of the efflux.

An involvement of rapidly turned-over proteins constitutes a second layer of complexity in the regulation of auxin efflux but should be essential to give plants the capability to rapidly respond to environmental stimuli. Auxin normally moves basipetally in plants. Asymmetric migration of the hormone transversally in tissues in response to unilateral light or gravity stimuli is believed to be responsible for photo- and geotropic reactions causing growth reorientation (Pickard 1985a, 1985b; Kaufman et al., 1995). Whereas longitudinal transport is controlled by a preferential localization of the efflux carriers at the basal ends of cells in the transport pathway (Goldsmith, 1977; Rubery, 1987), a novel distribution of the efflux carriers at the surface of the transporting cells might account for the apparition of the lateral auxin transport in stimulated plants. A rapid turnover of the efflux proteins at the PM associated with this novel distribution could be a physiologically significant component of tropic responses that occur within minutes, with auxin asymmetry preceding the change in growth direction.

In conclusion, we have described the effect of different pharmacological agents and conditions modifying ΔpH on the activities, monitored in parallel, of the auxin influx and efflux carriers in suspension-cultured tobacco cells. Both carriers are most likely different entities controlled by different mechanisms. Rapidly turned-over and phosphorylated proteins are essential to the activity of the efflux carrier but not to that of the influx carrier. Kinetic analysis using BFA provided an accurate estimation of the turnover of the efflux carriers at the PM, consistent with the fast establishment of tropic responses in plants. Auxin efflux was rapidly abolished by staurosporine and the related protein kinase inhibitor K252a, suggesting that permanent kinase activity is essential to maintain the efflux carrier activity. Since inhibition of auxin efflux by kinase activity dependent on the binding of NPA to its receptor has been reported elsewhere (Bernasconi, 1996), it appears clear that the regulation of auxin efflux in plants obeys a complicated scheme in which protein phosphorylation reactions are involved in both the positive and negative controls of the carrier activity. There are several lines of evidence (this study; Morris et al., 1991; Wilkinson and Morris, 1994; Bernasconi, 1996; Garbers et al., 1996) suggesting that the auxin efflux carrier constitutes a complex system regulated at multiple levels, in apparent contrast with the influx carrier. Both carriers probably appeared at an early stage in the evolution of green plants (Dibb-Fuller and Morris, 1992). This raises the question of why, during evolution, plants developed a sophisticated efflux system, and presents the task of identifying the carriers' physiological function, in particular for the influx carrier.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Pr. Dieter Klämbt (Botanisches Institut, University of Bonn, Germany) for helpful discussion and Dr. Spencer Brown (Institut des Sciences Végétales, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Gif sur Yvette, France) for critical reading.

Abbreviations:

- BA

benzoic acid

- BFA

brefeldin A

- CHI

cycloheximide

- ΔpH

transplasma membrane pH gradient

- NPA

naphthylphthalamic acid

- PAH

protonated propionic acid

- pHc

cytosolic pH

- pHe

extracellular pH

- pHi

intracellular pH

- PM

plasma membrane

- PP1

type-1 protein Ser/Thr phosphatase

- PP2A

type-2A protein Ser/Thr phosphatase

- t½

half-life time

Footnotes

This work was supported by funds from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (UPR0040).

LITERATURE CITED

- Bennet MJ, Marchant A, Haydn GG, May ST, Ward SP, Millner PA, Walke AR, Schulz B, Feldmann KA. Arabidopsis AUX1 gene: a permease-like regulator of root gravitropism. Science. 1996;273:948–950. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi P. Effect of synthetic and natural protein kinase inhibitors on auxin efflux in zucchini (Cucurbita pepo) hypocotyls. Physiol Plant. 1996;96:205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi P, Patel BC, Reagan JD, Subramanian MV. The N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid-binding protein is an integral membrane protein. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:427–432. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D, Muday GK. Naphthylphthalamic acid binding activity from zucchini hypocotyls is peripheral to the plasma membrane and is associated with the actin cytoskeleton. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1941–1953. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbarre A, Muller P, Imhoff V, Guern J. Comparison of mechanisms controlling uptake and accumulation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid, naphthalene-1-acetic acid, and indole-3-acetic acid in suspension-cultured tobacco cells. Planta. 1996;198:532–541. doi: 10.1007/BF00262639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbarre A, Muller P, Imhoff V, Morgat JL, Barbier-Brygoo H. Uptake, accumulation and metabolism of auxins in tobacco leaf protoplasts. Planta. 1994;195:159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dibb-Fuller JE, Morris DA. Studies on the evolution of auxin carriers and phytotropin receptors: transmembrane auxin transport in unicellular and multicellular Chlorophyta. Planta. 1992;186:219–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00196251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driouich A, Zhang GF, Staehelin LA. Effect of brefeldin A on the structure of the Golgi apparatus and on the synthesis and secretion of proteins and polysaccharides in sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus) suspension-cultured cells. Plant Physiol. 1993;101:1363–1373. doi: 10.1104/pp.101.4.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldwisch J, Zettl R, Hesse F, Schell J, Palme K. An auxin-binding protein is localized to the plasma membrane of maize coleoptile cells: identification by photoaffinity labeling and purification of a 23-kDa polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:475–479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felle H (1989) pH as a second messenger in plants. In WF Boss, DJ Morré, eds, Second Messengers in Plant Growth and Development. AR Liss, New York, pp 145–166

- Gamborg OL, Miller RA, Ojima K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp Cell Res. 1968;15:148–151. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(68)90403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbers C, DeLong A, Deruére J, Bernasconi P, Söll D. A mutation in protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit A affects auxin transport in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 1996;15:2115–2124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith MHM. The polar transport of auxin. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1977;28:439–478. [Google Scholar]

- Guern J, Felle H, Mathieu Y, Kurkdjian A. Regulation of intracellular pH in plant cells. Int Rev Cytol. 1991;127:111–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hager A, Debus G, Edel HG, Stransky H, Serrano R. Auxin induces exocytosis and the rapid synthesis of a high-turnover pool of plasma-membrane H+-ATPase. Planta. 1991;185:527–537. doi: 10.1007/BF00202963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks GR, Rice MS, Lomax TL. Characterization of auxin-binding proteins from zucchini plasma membrane. Planta. 1993;189:83–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00201348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidaka H, Kobayashi R (1993) Use of protein (serine/threonine) kinase activators and inhibitors to study protein phosphorylation in intact cells. In D Grahame Hardie, ed, Protein Phosphorylation, A Practical Approach, The Practical Approach Series. IRL Press, New York, pp 87–107

- Kaufman PB, Wu LL, Brock TG, Kim D. Hormones and the orientation of growth. In: Davies PJ, editor. Plant Hormones: Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Ed 2. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 547–571. [Google Scholar]

- Lomax TL, Hicks GR. Specific auxin-binding proteins in the plasma membrane: receptors or transporters. Biochem Soc Trans. 1992;20:64–69. doi: 10.1042/bst0200064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax TL, Muday GK, Rubery PH. Auxin transport. In: Davies PJ, editor. Plant Hormones: Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Ed 2. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 509–530. [Google Scholar]

- Loper MT, Spanswick RM. Auxin transport in suspension-cultured soybean root cells. I. Characterization. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:184–191. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.1.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKintosh C, Lyon GD, MacKintosh RW. Protein phosphatase inhibitors activate anti-fungal defense responses of soybean cotyledons and cells. Plant J. 1994;5:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu Y, Jouanneau JP, Thomine S, Lapous D, Guern J. Cytosolic protons as secondary messengers in elicitor-induced defense response. Biochem Soc Symp. 1994;60:113–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu Y, Lapous D, Thomine S, Laurière C, Guern J. Cytoplasmic acidification as an early phosphorylation-dependent response of tobacco cells to elicitors. Planta. 1996a;199:416–424. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu Y, Sanchez SJ, Droillard MJ, Lapous D, Laurière C, Guern J. Involvement of protein phosphorylation in the early steps of transduction of the oligogalacturonide signal in tobacco cells. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1996b;34:399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Morris DA, Rubery PH, Jarman J, Sabater M. Effects of inhibitors of protein synthesis on transmembrane auxin transport in Cucurbita pepo L. hypocotyl segments. J Exp Bot. 1991;42:773–783. [Google Scholar]

- Muller JF, Goujaud J, Caboche M. Isolation in vitro of naphthalene-acetic-tolerant mutants of Nicotiana tabacum, which are impaired in root morphogenesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;199:194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Neant I, Guerrier P. 6-Dimethylaminopurine blocks starfish oocyte maturation by inhibiting a relevant protein kinase activity. Exp Cell Res. 1988;176:68–79. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(88)90121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard BG. Roles of hormones, protons and calcium in geotropism. In: Pharis RP, Reid DM, editors. Encyclopedia of Plant physiology, New Series, Vol 11: Hormonal Regulation of Development. III. Role of Environmental Factors. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985a. pp. 193–281. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard BG. Roles of hormones in phototropism. In: Pharis RP, Reid DM, editors. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, New Series, Vol 11: Hormonal Regulation of Development. III. Role of Environmental Factors. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1985b. pp. 365–417. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DG, Hillmer S. Coated pits. In: Larsson PJ, Moller IM, editors. The Plant Plasma Membrane. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman JE. Mechanisms of intracellular protein transport. Nature. 1994;372:55–62. doi: 10.1038/372055a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubery PH. Hydrogen ion dependence of carrier-mediated auxin uptake by suspension-cultured crown gall cells. Planta. 1978;142:203–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00388213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubery PH. Auxin transport. In: Davies PJ, editor. Plant Hormones and Their Role in Plant Growth and Development. Boston, MA: Martinus Nijhoff; 1987. pp. 341–362. [Google Scholar]

- Rubery PH (1990) Phytotropins: receptors and endogenous ligands. In J Roberts, C Kirk, M Venis, eds, Hormone Perception and Signal Transduction in Animals and Plants. The Company of Biologists, Cambridge, UK, pp 119–146

- Satiat-Jeunemaitre B, Cole L, Bourett T, Howard R, Hawes C. Brefeldin A effects in plant and fungal cells: something new about vesicle trafficking? J Microsc. 1996;181:162–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1996.112393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satiat-Jeunemaitre B, Hawes C. The distribution of secretory products in plant cells is affected by brefeldin A. Cell Biol Int. 1993;17:183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler T, Bergfeld R, Hohl M, Schopfer P. Inhibition of Golgi-apparatus function by brefeldin A in maize coleoptiles and its consequences on auxin-mediated growth, cell-wall extensibility and secretion of cell-wall proteins. Planta. 1994;192:404–413. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Walker JC. Plant protein phosphatases. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:101–125. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner W, Caspari T. Membrane transport carriers. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:595–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S, Morris DA. Targeting of auxin carriers to the plasma membrane: effects of monensin on transmembrane auxin transport in Cucurbita pepo L. tissue. Planta. 1994;193:194–202. [Google Scholar]

- Zettl R, Feldwisch J, Boland W, Schell J, Palme K. 5′-Azido-[3,6-3H2]-1-naphthylphthalamic acid, a photoactivatable probe for naphthylphthalamic acid receptor proteins from higher plants: identification of a 23-kDa protein from maize coleoptile plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:480–484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]