Abstract

Activated intrarenal renin–angiotensin system plays a cardinal role in the pathogenesis of hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Angiotensinogen is the only known substrate for renin, which is the rate-limiting enzyme of the renin–angiotensin system. Because the levels of angiotensinogen are close to the Michaelis–Menten constant values for renin, angiotensinogen levels as well as renin levels can control the renin–angiotensin system activity, and thus, upregulation of angiotensinogen leads to an increase in the angiotensin II levels and ultimately increases blood pressure. Recent studies using experimental animal models have documented the involvement of angiotensinogen in the intrarenal renin–angiotensin system activation and development of hypertension. Enhanced intrarenal angiotensinogen mRNA and/or protein levels were observed in experimental models of hypertension and chronic kidney disease, supporting the important roles of angiotensinogen in the development and the progression of hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Urinary excretion rates of angiotensinogen provide a specific index of the intrarenal renin–angiotensin system status in angiotensin II-infused rats. Also, a direct quantitative method has been developed recently to measure urinary angiotensinogen using human angiotensinogen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. These data prompted us to measure urinary angiotensinogen in patients with hypertension and chronic kidney disease, and investigate correlations with clinical parameters. This short article will focus on the role of the augmented intrarenal angiotensinogen in the pathophysiology of hypertension and chronic kidney disease. In addition, the potential of urinary angiotensinogen as a novel biomarker of the intrarenal renin–angiotensin system status in hypertension and chronic kidney disease will be also discussed.

Keywords: Angiotensinogen, Renin–angiotensin system, Kidney, Hypertension, Chronic kidney disease

Introduction

Activation of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS) plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of hypertension and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [54]. In recent years, there has been increased emphasis on the role of the local/tissue RAS in specific tissues [15]. Emerging evidence has demonstrated the importance of the tissue RAS in the brain [4], heart [13], adrenal glands [78], vasculature [10, 20], and kidneys [54, 88]. Angiotensinogen (AGT) is the only known substrate for renin, which is the rate-limiting enzyme of the RAS. Although most of the circulating AGT is produced and secreted by the liver, the kidneys also produce AGT [28]. Intrarenal AGT mRNA and protein have been found to be localized to proximal tubular cells [29, 49, 100, 119]. The major fraction of angiotensin II present in renal tissues is generated locally from the AGT delivered to the kidney as well as from the AGT locally produced by proximal tubular cells [12, 28]. The AGT produced in proximal tubular cells appears to be secreted directly into the tubular lumen in addition to producing its metabolites intracellularly and secreting them into the tubular lumen [71, 101]. Because of its molecular size and protein binding, it seems unlikely that much of the plasma AGT filters across the glomerular membrane, further supporting the concept that proximal tubular cells secrete AGT directly into the tubular lumen [54]. Renin secreted by the juxtaglomerular apparatus cells into the renal interstitium and vascular compartment also provides a pathway for the local generation of angiotensin I [83]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is abundant in the kidneys and is present in proximal tubules, distal tubules, and collecting ducts [8]. Angiotensin I delivered to the kidney can also be converted to angiotensin II [66]. Therefore, all components enabling the generation of intrarenal angiotensin II are present along the nephron [54, 88].

Because the levels of AGT are close to the Michaelis–Menten constant values for renin, AGT levels can also control the activity of the RAS, and upregulation of AGT levels may lead to elevated angiotensin peptide levels and increases in blood pressure [6, 19]. Recent studies using experimental animal models and transgenic mice have documented the involvement of AGT in the activation of the intrarenal RAS and development of hypertension [5, 14, 16, 44, 59, 72, 80, 102, 114]. Genetic manipulations that lead to overexpression of AGT have consistently been shown to cause hypertension [42, 115]. In human genetic studies, a linkage has been established between the AGT gene and hypertension [3, 30, 31, 35, 127]. Enhanced intrarenal AGT mRNA and/or protein levels have also been observed in multiple experimental models of hypertension including angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive rats [48–50, 57, 62, 110], Dahl salt-sensitive (DS) hypertensive rats [55, 56], and spontaneously hypertensive rats [60] as well as in kidney diseases including diabetic nephropathy [1, 74, 82, 85, 113, 116], IgA nephropathy [53, 117], and radiation nephropathy [61]. Thus, AGT upregulation plays an important role in the development and progression of hypertension and kidney diseases [54, 88].

Previous reports have demonstrated that urinary excretion rates of AGT provide a specific index of intrarenal RAS status in angiotensin II-infused rats [48–50, 57, 62]. Also, a direct quantitative method has been developed recently to measure urinary AGT using human AGT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [40]. The ELISA has facilitated the measurements of urinary AGT in patients with hypertension and CKD, and has encouraged us to investigate the correlations with clinical parameters. This brief review will address the role of the augmented intrarenal AGT in the pathophysiology of hypertension and CKD. In addition, the potential of urinary AGT as a novel biomarker of the intrarenal RAS status in hypertension and CKD will be also discussed.

Intratubular localization of AGT

Using in situ hybridization, Ingelfinger et al. [29] demonstrated that the AGT gene was specifically present in the proximal tubules. Terada et al. [119] reported that AGT mRNA was expressed largely in the proximal convoluted tubules and proximal straight tubules, and in small amounts in glomeruli and vasa recta as revealed by reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction. Richoux et al. [100] and Darby et al. [11, 12] showed that renal AGT protein was specifically located in the proximal convoluted tubules by immunohistochemistry. Kobori et al. [49] also showed that there was strong positive immunostaining for AGT protein in proximal convoluted tubules and proximal straight tubules, and weak positive staining in glomeruli and vasa recta; however, there was no staining in distal tubules or collecting ducts. The origin of AGT mRNA as well as AGT protein in the kidney is still controversial [57, 77, 86, 90, 99]. The localization and regulation of intrarenal AGT mRNA/protein are more complicated than they seem [95, 105–108]. Recently, Kamiyama et al. [37] have established a novel method to isolate the three segments of the proximal tubular cells and to culture them separately (S1 segment: the pars convoluta, S2 segment: the end of the pars convoluta, and S3 segment: the pars recta). In the near future, these methods may be useful to investigate the segmental regulation of AGT mRNA and protein expression in physiological and pathological conditions.

Augmented intrarenal AGT in hypertension and CKD

Angiotensin II-dependent hypertension

The feedback loop of AGT by angiotensin II is demonstrated in various tissues including the liver [6, 46], heart [25, 118], adipose tissue [21, 75], and kidney [27, 110]. In more recent studies, Kobori et al. [48–50, 57, 62] have evaluated the effects of angiotensin II infusions on AGT and angiotensin II levels in the kidney and the relationship between urinary excretion of AGT and kidney angiotensin II or AGT levels in several models of hypertension. They reported that angiotensin II-infused rats have increases in renal AGT mRNA [49] and protein [48], and an enhancement of urinary excretion rate of AGT [50]. Chronic angiotensin II infusion to normal rats significantly increased urinary excretion rate of AGT in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Urinary excretion rate of AGT was closely correlated with systolic blood pressure and kidney angiotensin II content, but not with plasma angiotensin II concentration. Urinary protein excretion in volume-dependent hypertensive rats was significantly increased more than in angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive rats; however, urinary AGT excretion was significantly lower in volume-dependent hypertensive rats than in angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive rats [57]. Rat AGT was detected in plasma and urine before and after an acute injection of exogenous human AGT. Human AGT, however, was detected only in the plasma collected after the acute administration of human AGT but was not detected in the urine in angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive or sham-operated normotensive rats. The failure to detect human AGT in the urine suggests limited glomerular permeability and/or tubular degradation. This suggests that urinary AGT originates from the kidneys and not from plasma in rats [57, 86]. Chronic angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker (ARB) treatment offsets the augmented intrarenal/urinary AGT by angiotensin II infusions in rats [62].

Salt-sensitive hypertension

DS rats have been used as a model of human salt-sensitive hypertension because salt loading exaggerates the development of hypertension in strains that are genetically predis-posed to hypertension [32]. It is well-known that mature DS rats have low plasma renin activity levels [32], and few studies have addressed intrarenal angiotensin II and AGT regulation in DS rats because it has been assumed that the RAS is suppressed in DS rats fed high-salt (HS) diet. However, recent studies suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs reduces cardiac and/or renal dysfunction in DS rats made hypertensive by HS diet [23, 24, 64, 91, 96, 104]. Furthermore, Nakaya et al. [87] reported that prepubertal treatment with an ARB causes partial attenuation of hypertension and ameliorates the renal damage in adult DS rats fed HS. These data suggest that the local RAS may contribute to the development of hypertension and renal dysfunction in this model.

Kobori et al. [56] reported that DS rats on HS diet have inappropriate augmentation of intrarenal AGT that is not reflected in the plasma levels of RAS components. This enhancement of AGT may contribute to the impaired sodium excretion during HS and the development of hypertension in this strain. However, the mechanisms responsible for the inappropriate augmentation of intrarenal AGT by HS have been incompletely elucidated in that study. Recent studies reported that augmented oxidative stress or superoxide anion formation plays an important role in this animal model of hypertension [79, 120, 126]. Recently, Kobori et al. [55] demonstrated that inappropriate augmentation of intrarenal AGT by HS is associated with augmented reactive oxygen species in DS rats. In that study, systolic blood pressure was significantly increased by HS in DS rats, and was equally suppressed by a superoxide dismutase mimetic, tempol, and a nonspecific vasodilator, hydralazine. HS has been shown to suppress plasma and intrarenal expression of AGT in Sprague-Dawley [111] and Wistar-Kyoto [28] rats. Similarly, in that study, plasma AGT levels are also suppressed by HS. However, kidney AGT levels are enhanced by HS, and tempol treatment prevents this augmentation but hydralazine does not in DS rats. This paradoxical enhancement of intrarenal AGT by HS is observed in DS rats but not in Dahl salt-resistant rats [56]. Thus, these studies provide evidence that inappropriate augmentation of intrarenal AGT by HS is associated with the augmented reactive oxygen species in DS rats. The oxidative stress-induced RAS activation via AGT is also supported by a recent structural biology study [128]. The protein AGT must undergo conformational changes to be cleaved into a precursor of the hormone angiotensin, which increases blood pressure. Oxidative stress seems to mediate this structural alteration [112, 128].

Chronic glomerulonephritis

Chronic glomerulonephritis that results in substantial renal damage is frequently characterized by relentless progression to end-stage renal disease. Renal angiotensin II, the production of which is enhanced in chronic glomerulonephritis, can elevate the intraglomerular pressure, increase glomerular cell hypertrophy, and augmented extracellular matrix accumulation [7, 65]. RAS blockades markedly decelerate, and can even prevent, renal deterioration in glomerular disease [18, 70]. This may be an indication that factors other than angiotensin II play an important role in the progression of renal disease. There are several studies for renal expression of AGT in IgA nephropathy [17, 53, 117]. Most studies have shown an increased expression of AGT in the kidney of IgA nephropathy.

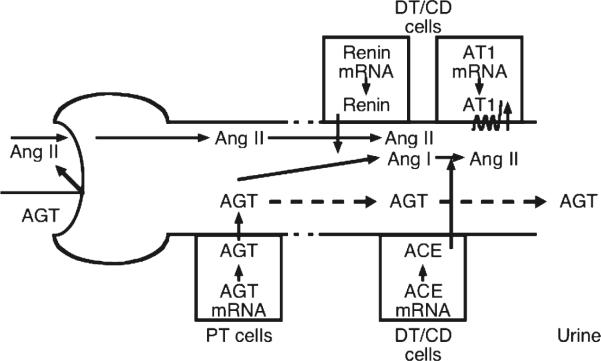

Glomerular crescents are defined as the presence of two or more layers of cells in the Bowman's space. Monocyte/macrophages and parietal epithelial cells are the principal mediators of crescents formation. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1/CC chemokine receptor 2 signaling pathway is involved in the pathogenesis of crescentic glomerulonephritis. The presence of crescents in glomeruli is a marker of severe injury [26]. After a single injection of antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies, marked crescent formations were observed in almost all glomeruli as a result of severe glomerular damage. CC chemokine receptor 2 antagonist or ARB alone moderately normalized the crescent formation [123]. Their combination significantly blocked the development of crescent formation, preventing the infiltration of macrophages. Consistently, the combination therapy markedly reduced proteinuria. In this glomerulonephritis model, the glomerular expression levels of AGT, angiotensin II and angiotensin II type 1 receptors were increased compared with control rats. While CC chemokine receptor 2 antagonist or ARB treatment moderately reduced the increase of these components in glomeruli, CC chemokine receptor 2 antagonist plus ARB treated further prevented these increases. Urinary AGT levels were paralleled with the expression levels of RAS components in glomeruli. These indicate that blocking the RAS is a key target and that AGT expression reflects intrarenal RAS activation in treatment of crescentic glomerulonephritis (Fig. 1) [121].

Fig. 1.

Working scheme for the augmented intrarenal and urinary angiotensinogen in hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Intrarenal renin-angiotensin (Ang) system in proximal and distal nephron segments was summarized. Because of its molecular size, it seems unlikely that much of the plasma angiotensinogen (AGT) filters across the glomerular membrane. In Ang II-dependent hypertension, increased proximal tubular (PT) secretion of AGTspills over into the distal nephron and increases Ang II effects on distal tubular (DT) reabsorption. CD, collecting ducts. ACE, Ang-converting enzyme. AT1, Ang II type 1 receptors adapted from Kobori, 2007 [54]

Diabetic nephropathy

Diabetes affects 220 million people worldwide, including 24 million Americans, and is the sixth leading cause of death in the USA. It is associated with increased incidence of functional and structural alterations in the kidneys, eventually leading to end-stage renal failure in many patients. Diabetic nephropathy is the most common cause of end-stage renal failure in the USA, accounting for 45 % of patients starting dialysis [36, 84]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is the most common type of diabetes accounting for 90–95 % of all diagnosed cases of diabetes and affecting 8 % of the US population. Obesity has been identified as the principal risk factor associated with the rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes. The epidemic proportions of obesity and diabetes justify the enormous effort to identify novel pathways and mechanisms involved in their prevention and treatment. Diabetes is a chronic and debilitating disease that is characterized by progressive albuminuria, declining glomerular filtration rate, functional and structural deterioration of the kidney, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Data concerning intrarenal RAS states in diabetes are inconsistent. Although various studies support an association between RAS and diabetic nephropathy, direct measurements have been unsuccessful in establishing that intrarenal angiotensin II is consistently elevated in diabetes [129]. However, intrarenal AGT levels are elevated in patients with diabetic nephropathy [38]. In rodent diabetic models, renin content varies and ACE expression has been shown to be increased or unchanged in glomeruli and vessels [22, 124]. In the type 2 diabetic mouse kidney, proximal tubule ACE immunostaining is decreased, while ACE2 immunostaining is increased compared to control mice [97]. However, angiotensin II type 1 receptor protein levels were significantly elevated in renal cortex from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats compared with control rats, associated with the downregulation of angiotensin II type 2 receptors [22, 124]. The cortical collecting ducts of streptozotocin-induced diabetic kidneys displayed a striking increase in angiotensin II type 1 receptor immunostaining intensity compared with control kidneys [22]. Moreover, it was recently shown that prorenin expression is elevated in the cortical collecting ducts of type 1 diabetic rats [39]. Furthermore, studies in models of type 2 diabetes show increased intrarenal angiotensin II levels and AGT mRNA levels, which are prevented by treatment with an ARB [85, 93]. Finally, increases in renal cortical AGT and angiotensin II levels associated with increased reactive oxygen species and renal injury have been observed in Zucker diabetic fatty obese rats compared to control lean rats [82, 116].

Urinary AGT as a novel biomarker of intrarenal RAS in hypertension and CKD

Development of human AGT ELISA

As discussed above, there is a quantitative relationship between urinary AGT and intrarenal production of AGT and angiotensin II. Urinary AGT excretion rates may provide a useful tool to identify angiotensin II-dependent hypertension in human hypertensive subjects. Recently, AGT ELISA systems have been established in humans [40] as well as in mice and rats [52]. Using these methods, evidence has been accumulated from clinical studies indicating that urinary AGT can be a novel biomarker of the activated intrarenal RAS in hypertension [47, 63, 67], in diabetic nephropathy [94, 103, 109], and in CKD [33, 34, 41, 43, 58, 68, 69, 73, 76, 81, 92, 122].

Urinary AGT in hypertension

The important role of the activated intrarenal RAS in the pathogenesis of hypertension is extensively discussed in a recent review article [89]. In a cross-sectional study, Kobori et al. reported that urinary AGT levels were significantly greater in hypertensive patients not treated with RAS blockers compared with normotensive subjects [47]. Moreover, patients treated with RAS blockers exhibited a marked attenuation of this augmentation. These data suggest that the efficacy of RAS blockade to reduce the intrarenal RAS activity can be assessed by measurements of urinary AGT [47].

In a population study, Kobori et al. demonstrated that activated intrarenal RAS is correlated with high blood pressure in humans [63]. They recruited 251 subjects and collected a single random spot urine sample from each subject. Because urinary AGT levels are significantly increased in patients with diabetes [58] and the use of antihypertensive drugs affects urinary AGT levels [47], they excluded patients who had diabetes and/or were receiving antihypertensive treatment. Consequently, 190 samples were included in this analysis. Urinary AGT levels did not differ between the races or the genders, but were significantly correlated with systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Moreover, this correlation was high in men, especially in Black men [63]. These data suggest that urinary AGT provides a novel reflection of the intrarenal RAS status in hypertension.

Urinary AGT in CKD

The important role of an activated intrarenal RAS in the pathogenesis of CKD is extensively discussed in a recent review article [45]. In order to test the hypothesis that urinary AGT levels are enhanced in CKD patients and correlated with some clinical parameters, 80 patients with CKD (37 women and 43 men, from 18 to 94 years old) and seven healthy volunteers (two women and five men, from 27 to 43 years old) were recruited [58]. Plasma AGT levels showed a normal distribution; however, urinary AGT-creatinine ratios deviated from the normal distribution. When a logarithmic transformation was executed, Log[urinary AGT-creatinine ratio] showed a normal distribution. Therefore, Log[urinary AGT-creatinine ratio] was used for further analyses. Log[urinary AGT-creatinine ratio] was not correlated with age, gender, height, body weight, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, serum sodium levels, serum potassium levels, urinary sodium-creatinine ratios, plasma renin activity, or plasma AGT levels. However, Log[urinary AGT-creatinine ratio] was significantly correlated positively with urinary albumin-creatinine ratios, fractional excretion of sodium, urinary protein-creatinine ratios, and serum creatinine, and correlated negatively with estimated glomerular filtration rate. Log[urinary AGT-creatinine ratio] was significantly increased in CKD patients compared with control subjects. These data suggest that urinary AGT levels can be a potential biomarker of severity of CKD [58].

In order to test the hypothesis that urinary AGT levels are increased in chronic glomerulonephritis patients, 100 urine samples from 70 chronic glomerulonephritis patients (26 from IgA nephropathy, 24 from purpura nephritis, 8 from lupus nephritis, 7 from focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and 5 from non-IgA mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis) and 30 normal control subjects were analyzed [122]. Urinary AGT-creatinine ratio was correlated positively with diastolic blood pressure, urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, urinary protein–creatinine ratio and urinary occult blood. Urinary AGT-creatinine ratio was significantly increased in chronic glomerulonephritis patients not treated with RAS blockers compared with control subjects. Importantly, patients with glomerulonephritis treated with RAS blockers had a marked attenuation of this augmentation. These data indicate that urinary AGT are increased in patients with chronic glomerulonephritis and treatment with RAS blockers suppresses urinary AGT. Thus, the efficacy of RAS blockade to reduce the intrarenal RAS activity can be confirmed by measurements of urinary AGT in chronic glomerulonephritis patients [122].

In order to test the hypothesis that urinary AGT provides a specific index of intrarenal RAS status in patients with IgA nephropathy, an observational study was performed [92]. This paper is a survey of urine specimens from three groups: healthy volunteers, patients with IgA nephropathy, and patients with minor glomerular abnormality. Patients with hypertension, diabetes, reduced glomerular filtration rate, and/or who were under any medication were excluded from this study. Urinary AGT levels were not different between healthy volunteers and patients with minor glomerular abnormality. However, urinary AGT levels, renal tissue AGT expression, and angiotensin II immunoreactivity were significantly higher in patients with IgA nephropathy than in patients with minor glomerular abnormality. Baseline urinary AGT levels were positively correlated with renal AGT gene expression and angiotensin II immunoreactivity but not with plasma renin activity or the urinary protein excretion rate. In patients with IgA nephropathy, treatment with an ARB significantly increased renal plasma flow and decreased filtration fraction, which were associated with reductions in urinary AGT levels. These data indicate that urinary AGT is a powerful tool for determining intrarenal RAS status and associated renal derangement in patients with IgA nephropathy [92]. These data suggest that urinary AGT levels can be used as a novel biomarker of the intrarenal RAS status in patients with CKD.

Urinary AGT as a new biomarker of intrarenal RAS status in diabetes

The important role of the activated intrarenal RAS in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy is extensively discussed in a recent review article [51]. Clinically, microalbuminuria is the most commonly used early marker of diabetic nephropathy [9]. Diabetic nephropathy is thought to be a unidirectional process from microalbuminuria to end-stage renal failure [2]. However, recent studies demonstrate that a large proportion of diabetic nephropathy patients revert to normoalbuminuria and that one third of them exhibit reduced renal function even in the microalbuminuria stage [98]. It is claimed that urinary inflammatory markers are high in microalbuminuric type 1 diabetes having diminished renal function, but not in microalbuminuric type 1 diabetes patients with stable renal function. However, no single marker has been sufficient to represent the whole panel [125]. Therefore, a more sensitive and more specific marker for activation of the RAS in diabetic nephropathy would be highly advantageous.

To demonstrate that administration of an ARB interferes with the vicious cycle of high glucose-reactive oxygen species–AGT–angiotensin II-angiotensin II type 1 receptor–reactive oxygen species by suppressing reactive oxygen species and inflammation, 13 patients with hypertensive diabetic nephropathy were recruited and evaluated before and at 16 weeks after treatment by ARBs [94]. Urinary AGT, albumin, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, 8-epi-prostaglandin F2 alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10 were assessed. ARB treatment reduced the blood pressure and urinary levels of AGT, albumin, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, 8-epi-prostaglandin F2 alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and interleukin-6, while increasing urinary interleukin-10 levels. The reduction of urinary AGT correlated with the reduction of blood pressure and urinary levels of albumin, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, 8-epi-prostaglandin F2 alpha, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and interleukin-6 and the increase of urinary interleukin-10 levels. These results suggest that the mechanisms by which ARBs exert their renoprotective effect in patients with type 2 diabetes may involve the suppression of intrarenal AGT levels in association with reduced anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [94].

To determine if urinary AGT levels can be dissociated from urinary albumin or protein excretion rates in type 1 diabetes juveniles, early phase studies were performed in control and diabetic juveniles [103]. Of the 55 juveniles recruited, 34 were patients with type 1 diabetes and 21 were gender- and age-matched control subjects. Since the primary focus of the study was comparison between the normoalbuminuric patients with type 1 diabetes and their control subjects, six microalbuminuric patients with type 1 diabetes (urinary albumin–creatinine ratio>30 mg/g) were excluded. Consequently, 49 urine and plasma samples were analyzed. None of them received treatment with RAS blockade. Neither urinary albumin–creatinine ratios nor urinary protein–creatinine ratios were significantly increased in these patients with type 1 diabetes compared to control subjects, suggesting that these patients were in their pre-microalbuminuric phase of diabetic nephropathy. However, urinary AGT–creatinine ratios were significantly increased in these patients compared to control subjects. Importantly, the AGT increase was not observed in plasma. These data indicate that urinary AGT levels are increased in type 1 diabetes subjects before any increase in urinary albumin levels, suggesting a possibility that urinary AGT levels serve as a very sensitive early marker of intrarenal RAS activation and may be one of the earliest predictors of diabetic nephropathy in patients with diabetes [103].

Conclusions

This brief review discussed the important role of the activated intrarenal RAS in the pathogenesis of hypertension and CKD. In addition, the potential of urinary AGT as a novel biomarker of the intrarenal RAS status in hypertension and CKD was also addressed. The complicated and pleiotropic roles of activated RAS in pathogenesis of hypertension and CKD continue to receive recognition from emerging and ongoing studies. Accordingly, the assessment of urinary AGT as an early biomarker of the status of the intrarenal RAS may be of substantial importance. It may be particularly helpful in serving as a means to determine efficacy of the treatment to reduce intrarenal angiotensin II levels.

Acknowledgments

Researches performed in authors' laboratories were supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK072408) and by Center of Biomedical Research Excellence Grant of National Center for Research Resources (P20RR017659). The authors appreciate Ms. Natsuko Ishii (Kagawa University, Kagawa, Japan) for her help to prepare the manuscript.

References

- 1.Anderson S, Jung FF, Ingelfinger JR. Renal renin–angiotensin system in diabetes: functional, immunohistochemical, and molecular biological correlations. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:F477–F486. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.4.F477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anonymous The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balam-Ortiz E, Esquivel-Villarreal A, Huerta-Hernandez D, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Alfaro-Ruiz L, Munoz-Monroy O, Gutierrez R, Figueroa-Genis E, Carrillo K, Elizalde A, Hidalgo A, Rodriguez M, Urushihara M, Kobori H, Jimenez-Sanchez G. Hypercontrols in genotype–phenotype analysis reveal ancestral haplotypes associated with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;59:847–853. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.176453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baltatu O, Silva JA, Jr, Ganten D, Bader M. The brain renin–angiotensin system modulates angiotensin II-induced hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2000;35:409–412. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohlender J, Menard J, Ganten D, Luft FC. Angiotensinogen concentrations and renin clearance: implications for blood pressure regulation. Hypertension. 2000;35:780–786. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasier AR, Li J. Mechanisms for inducible control of angiotensinogen gene transcription. Hypertension. 1996;27:465–475. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunner HR. ACE inhibitors in renal disease. Kidney Int. 1992;42:463–479. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casarini DE, Boim MA, Stella RC, Krieger-Azzolini MH, Krieger JE, Schor N. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme activity in tubular fluid along the rat nephron. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:F405–F409. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.3.F405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danser AH, Admiraal PJ, Derkx FH, Schalekamp MA. Angiotensin I-to-II conversion in the human renal vascular bed. J Hypertens. 1998;16:2051–2056. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816121-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darby IA, Congiu M, Fernley RT, Sernia C, Coghlan JP. Cellular and ultrastructural location of angiotensinogen in rat and sheep kidney. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1557–1560. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darby IA, Sernia C. In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry of renal angiotensinogen in neonatal and adult rat kidneys. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;281:197–206. doi: 10.1007/BF00583388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dell'Italia LJ, Meng QC, Balcells E, Wei CC, Palmer R, Hageman GR, Durand J, Hankes GH, Oparil S. Compartmentalization of angiotensin II generation in the dog heart. Evidence for independent mechanisms in intravascular and interstitial spaces. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:253–258. doi: 10.1172/JCI119529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ding Y, Davisson RL, Hardy DO, Zhu LJ, Merrill DC, Catterall JF, Sigmund CD. The kidney androgen-regulated protein promoter confers renal proximal tubule cell-specific and highly androgen-responsive expression on the human angiotensinogen gene in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28142–28148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dzau VJ, Re R. Tissue angiotensin system in cardiovascular medicine. A paradigm shift? Circulation. 1994;89:493–498. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.1.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukamizu A, Sugimura K, Takimoto E, Sugiyama F, Seo MS, Takahashi S, Hatae T, Kajiwara N, Yagami K, Murakami K. Chimeric renin–angiotensin system demonstrates sustained increase in blood pressure of transgenic mice carrying both human renin and human angiotensinogen genes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11617–11621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuda M, Urushihara M, Wakamatsu T, Oikawa T, Kobori H. Proximal tubular angiotensinogen in renal biopsy suggests nondipper BP rhythm accompanied by enhanced tubular sodium reabsorption. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1453–1459. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328353e807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giatras I, Lau J, Levey AS. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on the progression of nondiabetic renal disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibition and Progressive Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:337–345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gould AB, Green D. Kinetics of the human renin and human substrate reaction. Cardiovasc Res. 1971;5:86–89. doi: 10.1093/cvr/5.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1994;74:1141–1148. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hainault I, Nebout G, Turban S, Ardouin B, Ferre P, Quignard-Boulange A. Adipose tissue-specific increase in angiotensinogen expression and secretion in the obese (fa/fa) Zucker rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282:E59–E66. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2002.282.1.E59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison-Bernard LM, Zhuo J, Kobori H, Ohishi M, Navar LG. Intrarenal AT1 receptor and ACE binding in ANG II-induced hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F19–F25. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00335.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayakawa H, Coffee K, Raij L. Endothelial dysfunction and cardiorenal injury in experimental salt-sensitive hypertension: effects of antihypertensive therapy. Circulation. 1997;96:2407–2413. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashida W, Kihara Y, Yasaka A, Inagaki K, Iwanaga Y, Sasayama S. Stage-specific differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in hypertrophied and failing rat hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:733–744. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herrmann HC, Dzau VJ. The feedback regulation of angiotensinogen production by components of the renin–angiotensin system. Circ Res. 1983;52:328–334. doi: 10.1161/01.res.52.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson BG, Tryggvason K, Sundaramoorthy M, Neilson EG. Alport's syndrome, Goodpasture's syndrome, and type IV collagen. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2543–2556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingelfinger JR, Jung F, Diamant D, Haveran L, Lee E, Brem A, Tang SS. Rat proximal tubule cell line transformed with origin-defective SV40 DNA: autocrine ANG II feedback. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F218–F227. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.2.F218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingelfinger JR, Pratt RE, Ellison K, Dzau VJ. Sodium regulation of angiotensinogen mRNA expression in rat kidney cortex and medulla. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1311–1315. doi: 10.1172/JCI112716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ingelfinger JR, Zuo WM, Fon EA, Ellison KE, Dzau VJ. In situ hybridization evidence for angiotensinogen messenger RNA in the rat proximal tubule. An hypothesis for the intrarenal renin angiotensin system. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:417–423. doi: 10.1172/JCI114454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue I, Nakajima T, Williams CS, Quackenbush J, Puryear R, Powers M, Cheng T, Ludwig EH, Sharma AM, Hata A, Jeunemaitre X, Lalouel JM. A nucleotide substitution in the promoter of human angiotensinogen is associated with essential hypertension and affects basal transcription in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1786–1797. doi: 10.1172/JCI119343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishigami T, Umemura S, Tamura K, Hibi K, Nyui N, Kihara M, Yabana M, Watanabe Y, Sumida Y, Nagahara T, Ochiai H, Ishii M. Essential hypertension and 5′ upstream core promoter region of human angiotensinogen gene. Hypertension. 1997;30:1325–1330. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwai J, Dahl LK, Knudsen KD. Genetic influence on the renin–angiotensin system: low renin activities in hypertension-prone rats. Circ Res. 1973;32:678–684. doi: 10.1161/01.res.32.6.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jang HR, Kim SM, Lee YJ, Lee JE, Huh W, Kim DJ, Oh HY, Kim YG. The origin and the clinical significance of urinary angiotensinogen in proteinuric IgA nephropathy patients. Ann Med. 2012;44:448–457. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.558518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang HR, Lee YJ, Kim SR, Kim SG, Jang EH, Lee JE, Huh W, Kim YG. Potential role of urinary angiotensinogen in predicting antiproteinuric effects of angiotensin receptor blocker in non-diabetic chronic kidney disease patients: a preliminary report. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88:210–216. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeunemaitre X, Soubrier F, Kotelevtsev YV, Lifton RP, Williams CS, Charru A, Hunt SC, Hopkins PN, Williams RR, Lalouel JM. Molecular basis of human hypertension: role of angiotensinogen. Cell. 1992;71:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90275-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joss N, Paterson KR, Deighan CJ, Simpson K, Boulton-Jones JM. Diabetic nephropathy: how effective is treatment in clinical practice? QJM. 2002;95:41–49. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/95.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamiyama M, Garner MK, Farragut KM, Kobori H. The establishment of a primary culture system of proximal tubule segments using specific markers from normal mouse kidneys. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:5098–5111. doi: 10.3390/ijms13045098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamiyama M, Urushihara M, Morikawa T, Konishi Y, Imanishi M, Nishiyama A, Kobori H. Augmented intrarenal angiotensinogen mRNA expression parallels renal dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Hypertension. 2010;56:e135. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang JJ, Toma I, Sipos A, Meer EJ, Vargas SL, Peti-Peterdi J. The collecting duct is the major source of prorenin in diabetes. Hypertension. 2008;51:1597–1604. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.107268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katsurada A, Hagiwara Y, Miyashita K, Satou R, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Navar LG, Kobori H. Novel sandwich ELISA for human angiotensinogen. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F956–F960. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00090.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim SM, Jang HR, Lee YJ, Lee JE, Huh WS, Kim DJ, Oh HY, Kim YG. Urinary angiotensinogen levels reflect the severity of renal histopathology in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2011;76:117–123. doi: 10.5414/cn107045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim HS, Krege JH, Kluckman KD, Hagaman JR, Hodgin JB, Best CF, Jennette JC, Coffman TM, Maeda N, Smithies O. Genetic control of blood pressure and the angiotensinogen locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:2735–2739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim YG, Song SB, Lee SH, Moon JY, Jeong KH, Lee TW, Ihm CG. Urinary angiotensinogen as a predictive marker in patients with immunoglobulin A nephropathy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2011;15:720–726. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0475-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kimura S, Mullins JJ, Bunnemann B, Metzger R, Hilgenfeldt U, Zimmermann F, Jacob H, Fuxe K, Ganten D, Kaling M. High blood pressure in transgenic mice carrying the rat angiotensinogen gene. EMBO J. 1992;11:821–827. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiyomoto H, Kobori H, Nishiyama A. Chapter 4: renin–angiotensin system in the kidney and oxidative stress: local renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system and NADPH oxidase-dependent oxidative stress in the kidney. In: Miyata T, Eckardt KU, Nangaku M, editors. Studies on renal disorders. Oxidative stress in applied basic research and clinical practice. Springer Science + Business Media, LLC; Boston: 2011. pp. 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klett C, Bader M, Ganten D, Hackenthal E. Mechanism by which angiotensin II stabilizes messenger RNA for angiotensinogen. Hypertension. 1994;23:I120–I125. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.1_suppl.i120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobori H, Alper AB, Shenava R, Katsurada A, Saito T, Ohashi N, Urushihara M, Miyata K, Satou R, Hamm LL, Navar LG. Urinary angiotensinogen as a novel biomarker of the intrarenal renin–angiotensin system status in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;53:344–350. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.123802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Enhancement of angiotensinogen expression in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;37:1329–1335. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Expression of angiotensinogen mRNA and protein in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:431–439. doi: 10.1681/asn.v123431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Urinary excretion of angiotensinogen reflects intrarenal angiotensinogen production. Kidney Int. 2002;61:579–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobori H, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Chapter 8: role of activated renin–angiotensin system in pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. In: Prabhakar SS, editor. Advances in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. NovaScience Publishers; New York: 2011. pp. 161–198. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kobori H, Katsurada A, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Satou R, Saito T, Hagiwara Y, Miyashita K, Navar LG. Determination of plasma and urinary angiotensinogen levels in rodents by newly developed ELISA. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294:F1257–F1263. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00588.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kobori H, Katsurada A, Ozawa Y, Satou R, Miyata K, Hase N, Suzaki Y, Shoji T. Enhanced intrarenal oxidative stress and angiotensinogen in IgA nephropathy patients. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin–angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:251–287. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobori H, Nishiyama A. Effects of tempol on renal angiotensinogen production in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kobori H, Nishiyama A, Abe Y, Navar LG. Enhancement of intrarenal angiotensinogen in Dahl salt-sensitive rats on high salt diet. Hypertension. 2003;41:592–597. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000056768.03657.B4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kobori H, Nishiyama A, Harrison-Bernard LM, Navar LG. Urinary angiotensinogen as an indicator of intrarenal angiotensin status in hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:42–49. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000050102.90932.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kobori H, Ohashi N, Katsurada A, Miyata K, Satou R, Saito T, Yamamoto T. Urinary angiotensinogen as a potential bio-marker of severity of chronic kidney diseases. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2008;2:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Satou R, Katsurada A, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Hase N, Suzaki Y, Sigmund CD, Navar LG. Kidney-specific enhancement of ANG II stimulates endogenous intrarenal angiotensinogen in gene-targeted mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F938–F945. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00146.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Suzaki Y, Nishiyama A. Enhanced intrarenal angiotensinogen contributes to early renal injury in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2073–2080. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Suzaki Y, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Nishiyama A, Shoji T, Cohen EP, Navar LG. Young Scholars Award Lecture: intratubular angiotensinogen in hypertension and kidney diseases. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kobori H, Prieto-Carrasquero MC, Ozawa Y, Navar LG. AT1 receptor mediated augmentation of intrarenal angiotensinogen in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;43:1126–1132. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000122875.91100.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kobori H, Urushihara M, Xu JH, Berenson GS, Navar LG. Urinary angiotensinogen is correlated with blood pressure in men (Bogalusa Heart Study) J Hypertens. 2010;28:1422–1428. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283392673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kodama K, Adachi H, Sonoda J. Beneficial effects of long-term enalapril treatment and low-salt intake on survival rate of Dahl salt-sensitive rats with established hypertension. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kohan DE. Angiotensin II and endothelin in chronic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1998;54:646–647. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Komlosi P, Fuson AL, Fintha A, Peti-Peterdi J, Rosivall L, Warnock DG, Bell PD. Angiotensin I conversion to angiotensin II stimulates cortical collecting duct sodium transport. Hypertension. 2003;42:195–199. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000081221.36703.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Konishi Y, Nishiyama A, Morikawa T, Kitabayashi C, Shibata M, Hamada M, Kishida M, Hitomi H, Kiyomoto H, Miyashita T, Mori N, Urushihara M, Kobori H, Imanishi M. Relationship between urinary angiotensinogen and salt sensitivity of blood pressure in patients with IgA nephropathy. Hypertension. 2011;58:205–211. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.166843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kutlugun AA, Altun B, Aktan U, Turkmen E, Altindal M, Yildirim T, Yilmaz R, Arici M, Erdem Y, Turgan C. The relation between urinary angiotensinogen and proteinuria in renal AA amyloidosis patients. Amyloid. 2012;19:28–32. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.654530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kutlugun AA, Altun B, Buyukasik Y, Aki T, Turkmen E, Altindal M, Yildirim T, Yilmaz R, Turgan C. Elevated urinary angiotensinogen a marker of intrarenal renin angiotensin system in hypertensive renal transplant recipients: does it play a role in development of proteinuria in hypertensive renal transplant patients? Transpl Int. 2012;25:13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lafayette RA, Mayer G, Park SK, Meyer TW. Angiotensin II receptor blockade limits glomerular injury in rats with reduced renal mass. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:766–771. doi: 10.1172/JCI115949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lantelme P, Rohrwasser A, Gociman B, Hillas E, Cheng T, Petty G, Thomas J, Xiao S, Ishigami T, Herrmann T, Terreros DA, Ward K, Lalouel JM. Effects of dietary sodium and genetic background on angiotensinogen and renin in mouse. Hypertension. 2002;39:1007–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000016177.20565.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lavoie JL, Lake-Bruse KD, Sigmund CD. Increased blood pressure in transgenic mice expressing both human renin and angiotensinogen in the renal proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F965–F971. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00402.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee YJ, Cho S, Kim SR, Jang HR, Lee JE, Huh W, Kim DJ, Oh HY, Kim YG. Effect of losartan on proteinuria and urinary angiotensinogen excretion in non-diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87:664–669. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2011.118059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leehey DJ, Singh AK, Bast JP, Sethupathi P, Singh R. Glomerular renin angiotensin system in streptozotocin diabetic and Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Transl Res. 2008;151:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu H, Boustany-Kari CM, Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Angiotensin II increases adipose angiotensinogen expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1280–E1287. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00277.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mao YN, Liu W, Li YG, Jia GC, Zhang Z, Guan YJ, Zhou XF, Liu YF. Urinary angiotensinogen levels in relation to renal involvement of Henoch-Schonlein purpura in children. Nephrology (Carlton) 2012;17:53–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2011.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Matsusaka T, Niimura F, Shimizu A, Pastan I, Saito A, Kobori H, Nishiyama A, Ichikawa I. Liver angiotensinogen is the primary source of renal angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1181–1189. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011121159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mazzocchi G, Malendowicz LK, Markowska A, Albertin G, Nussdorfer GG. Role of adrenal renin-angiotensin system in the control of aldosterone secretion in sodium-restricted rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278:E1027–E1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.6.E1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meng S, Cason GW, Gannon AW, Racusen LC, Manning RD., Jr Oxidative stress in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:1346–1352. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000070028.99408.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Merrill DC, Thompson MW, Carney CL, Granwehr BP, Schlager G, Robillard JE, Sigmund CD. Chronic hypertension and altered baroreflex responses in transgenic mice containing the human renin and human angiotensinogen genes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1047–1055. doi: 10.1172/JCI118497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mills KT, Kobori H, Hamm LL, Alper AB, Khan IE, Rahman M, Navar LG, Liu Y, Browne GM, Batuman V, He J, Chen J. Increased urinary excretion of angiotensinogen is associated with risk of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3176–3181. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miyata K, Ohashi N, Suzaki Y, Katsurada A, Kobori H. Sequential activation of the reactive oxygen species/angiotensinogen/renin–angiotensin system axis in renal injury of type 2 diabetic rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:922–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.04938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Moe OW, Ujiie K, Star RA, Miller RT, Widell J, Alpern RJ, Henrich WL. Renin expression in renal proximal tubule. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:774–779. doi: 10.1172/JCI116296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nagai Y, Yao L, Kobori H, Miyata K, Ozawa Y, Miyatake A, Yukimura T, Shokoji T, Kimura S, Kiyomoto H, Kohno M, Abe Y, Nishiyama A. Temporary angiotensin II blockade at the prediabetic stage attenuates the development of renal injury in type 2 diabetic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:703–711. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nakano D, Kobori H, Burford JL, Gevorgyan H, Seidel S, Hitomi H, Nishiyama A, Peti-Peterdi J. Multiphoton Imaging of the Glomerular Permeability of Angiotensinogen. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012010078. doi:10.1681/ASN.2012010078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakaya H, Sasamura H, Mifune M, Shimizu-Hirota R, Kuroda M, Hayashi M, Saruta T. Prepubertal treatment with angiotensin receptor blocker causes partial attenuation of hypertension and renal damage in adult Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Nephron. 2002;91:710–718. doi: 10.1159/000065035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Navar LG, Harrison-Bernard LM, Nishiyama A, Kobori H. Regulation of intrarenal angiotensin II in hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;39:316–322. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Navar LG, Kobori H, Prieto MC, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA. Intratubular renin-angiotensin system in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:355–362. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Navar LG, Satou R, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA. The increasing complexity of the intratubular renin angiotensin system. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1130–1132. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nishikimi T, Mori Y, Kobayashi N, Tadokoro K, Wang X, Akimoto K, Yoshihara F, Kangawa K, Matsuoka H. Renoprotective effect of chronic adrenomedullin infusion in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2002;39:1077–1082. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000018910.74377.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nishiyama A, Konishi Y, Ohashi N, Morikawa T, Urushihara M, Maeda I, Hamada M, Kishida M, Hitomi H, Shirahashi N, Kobori H, Imanishi M. Urinary angiotensinogen reflects the activity of intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:170–177. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nishiyama A, Nakagawa T, Kobori H, Nagai Y, Okada N, Konishi Y, Morikawa T, Okumura M, Meda I, Kiyomoto H, Hosomi N, Mori T, Ito S, Imanishi M. Strict angiotensin blockade prevents the augmentation of intrarenal angiotensin II and podocyte abnormalities in type 2 diabetic rats with micro-albuminuria. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1849–1859. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283060efa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ogawa S, Kobori H, Ohashi N, Urushihara M, Nishiyama A, Mori T, Ishizuka T, Nako K, Ito S. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers reduce urinary angiotensinogen excretion and the levels of urinary markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Biomark Insights. 2009;4:97–102. doi: 10.4137/bmi.s2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ohashi N, Urushihara M, Satou R, Kobori H. Glomerular angiotensinogen is induced in mesangial cells in diabetic rats via reactive oxygen species—ERK/JNK pathways. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:1174–1181. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Otsuka F, Yamauchi T, Kataoka H, Mimura Y, Ogura T, Makino H. Effects of chronic inhibition of ACE and AT1 receptors on glomerular injury in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R1797–R1806. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.6.R1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Park S, Bivona BJ, Kobori H, Seth DM, Chappell MC, Lazartigues E, Harrison-Bernard LM. Major role for ACE-independent intrarenal ANGII formation in type II diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F37–F48. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00519.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Silva KH, Finkelstein DM, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Regression of microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2285–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pohl M, Kaminski H, Castrop H, Bader M, Himmerkus N, Bleich M, Bachmann S, Theilig F. Intrarenal renin angiotensin system revisited: role of megalin-dependent endocytosis along the proximal nephron. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:41935–41946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.150284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Richoux JP, Cordonnier JL, Bouhnik J, Clauser E, Corvol P, Menard J, Grignon G. Immunocytochemical localization of angiotensinogen in rat liver and kidney. Cell Tissue Res. 1983;233:439–451. doi: 10.1007/BF00238309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rohrwasser A, Morgan T, Dillon HF, Zhao L, Callaway CW, Hillas E, Zhang S, Cheng T, Inagami T, Ward K, Terreros DA, Lalouel JM. Elements of a paracrine tubular renin-angiotensin system along the entire nephron. Hypertension. 1999;34:1265–1274. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sachetelli S, Liu Q, Zhang SL, Liu F, Hsieh TJ, Brezniceanu ML, Guo DF, Filep JG, Ingelfinger JR, Sigmund CD, Hamet P, Chan JS. RAS blockade decreases blood pressure and proteinuria in transgenic mice overexpressing rat angiotensinogen gene in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Saito T, Urushihara M, Kotani Y, Kagami S, Kobori H. Increased urinary angiotensinogen is precedent to increased urinary albumin in patients with type 1 diabetes. Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:478–480. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181b90c25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sakata Y, Masuyama T, Yamamoto K, Doi R, Mano T, Kuzuya T, Miwa T, Takeda H, Hori M. Renin angiotensin system-dependent hypertrophy as a contributor to heart failure in hypertensive rats: different characteristics from renin angiotensin system-independent hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Satou R, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Katsurada A, Navar LG, Kobori H. Costimulation with angiotensin II and interleukin 6 augments angiotensinogen expression in cultured human renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F283–F289. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00047.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Satou R, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Miyata K, Ohashi N, Urushihara M, Acres OW, Navar LG, Kobori H. IL-6 augments angiotensinogen in primary cultured renal proximal tubular cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;311:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Satou R, Miyata K, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Ingelfinger JR, Navar LG, Kobori H. Interferon-gamma biphasically regulates angiotensinogen expression via a JAK-STAT pathway and suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) in renal proximal tubular cells. FASEB J. 2012;26:1821–1830. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-195198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Satou R, Miyata K, Katsurada A, Navar LG, Kobori H. Tumor necrosis factor-{alpha} suppresses angiotensinogen expression through formation of a p50/p50 homodimer in human renal proximal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C750–C759. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00078.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sawaguchi M, Araki SI, Kobori H, Urushihara M, Haneda M, Koya D, Kashiwagi A, Uzu T, Maegawa H. Association between urinary angiotensinogen levels and renal and cardiovascular prognoses in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2012;3:318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2011.00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schunkert H, Ingelfinger JR, Jacob H, Jackson B, Bouyounes B, Dzau VJ. Reciprocal feedback regulation of kidney angiotensinogen and renin mRNA expressions by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:E863–E869. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.5.E863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sechi LA, Griffin CA, Giacchetti G, Valentin JP, Llorens-Cortes C, Corvol P, Schambelan M. Tissue-specific regulation of type 1 angiotensin II receptor mRNA levels in the rat. Hypertension. 1996;28:403–408. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sigmund CD. Structural biology: on stress and pressure. Nature. 2010;468:46–47. doi: 10.1038/468046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Singh R, Singh AK, Leehey DJ. A novel mechanism for angiotensin II formation in streptozotocin-diabetic rat glomeruli. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F1183–F1190. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00159.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Smithies O. Theodore Cooper Memorial Lecture. A mouse view of hypertension. Hypertension. 1997;30:1318–1324. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Smithies O, Kim HS. Targeted gene duplication and disruption for analyzing quantitative genetic traits in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3612–3615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Suzaki Y, Ozawa Y, Kobori H. Intrarenal oxidative stress and augmented angiotensinogen are precedent to renal injury in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Int J Biol Sci. 2007;3:40–46. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.3.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Takamatsu M, Urushihara M, Kondo S, Shimizu M, Morioka T, Oite T, Kobori H, Kagami S. Glomerular angiotensinogen protein is enhanced in pediatric IgA nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1257–1267. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-0801-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tamura K, Umemura S, Nyui N, Hibi K, Ishigami T, Kihara M, Toya Y, Ishii M. Activation of angiotensinogen gene in cardiac myocytes by angiotensin II and mechanical stretch. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1–R9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Terada Y, Tomita K, Nonoguchi H, Marumo F. PCR localization of angiotensin II receptor and angiotensinogen mRNAs in rat kidney. Kidney Int. 1993;43:1251–1259. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tojo A, Onozato ML, Kobayashi N, Goto A, Matsuoka H, Fujita T. Angiotensin II and oxidative stress in Dahl Salt-sensitive rat with heart failure. Hypertension. 2002;40:834–839. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000039506.43589.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Urushihara M, Kobori H. Angiotensinogen expression is enhanced in the progression of glomerular disease. Int J Clin Med. 2011;2:378–387. doi: 10.4236/ijcm.2011.24064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Urushihara M, Kondo S, Kagami S, Kobori H. Urinary angiotensinogen accurately reflects intrarenal renin-angiotensin system activity. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31:318–325. doi: 10.1159/000286037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Urushihara M, Ohashi N, Miyata K, Satou R, Acres OW, Kobori H. Addition of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker to CCR2 antagonist markedly attenuates crescentic glomerulonephritis. Hypertension. 2011;57:586–593. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.165704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wehbi GJ, Zimpelmann J, Carey RM, Levine DZ, Burns KD. Early streptozotocin-diabetes mellitus downregulates rat kidney AT2 receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F254–F265. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.2.F254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wolkow PP, Niewczas MA, Perkins B, Ficociello LH, Lipinski B, Warram JH, Krolewski AS. Association of urinary inflammatory markers and renal decline in microalbuminuric type 1 diabetics. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:789–797. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ying WZ, Xia H, Sanders PW. Nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) mutation in Dahl/Rapp rats decreases enzyme stability. Circ Res. 2001;89:317–322. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.094625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhao YY, Zhou J, Narayanan CS, Cui Y, Kumar A. Role of C/A polymorphism at −20 on the expression of human angiotensinogen gene. Hypertension. 1999;33:108–115. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhou A, Carrell RW, Murphy MP, Wei Z, Yan Y, Stanley PL, Stein PE, Broughton Pipkin F, Read RJ. A redox switch in angiotensinogen modulates angiotensin release. Nature. 2010;468:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature09505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zimpelmann J, Kumar D, Levine DZ, Wehbi G, Imig JD, Navar LG, Burns KD. Early diabetes mellitus stimulates proximal tubule renin mRNA expression in the rat. Kidney Int. 2000;58:2320–2330. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]