Abstract

Background

Obesity development is a complex process which can be influenced by genetic predisposition modified by environmental factors. Nowadays, the problem of overweight and obesity, including related complications, occurs in increasingly younger children. Thus, there is a need for new genetic markers of increased risk of excessive body mass.

Objective

The aim of the present study was to examine the relation between polymorphisms located in promoter regions of IL-1beta, IL-6, and TNF-alpha genes and obesity development in children. Fifty obese and 55 normal weighing children were enrolled into the study. Genetic examination was performed using PCR-RFLP technique.

Results

We found a relation between G174C polymorphism in IL-6 gene and G308A in TNF-alpha gene with the occurrence of obesity. Allele A in G308A was more frequent in the obese group than in the control one (P = 0.04). The presence of allele C in promoter region of IL-6 gene was more frequent in obese children and connected with a statistically significant increase in the sum of 10 skin fold thickness measurements (P = 0.03).

Conclusions

The polymorphism C3954T in IL-1beta gene showed no such relation. The examined polymorphisms of proinflammatory cytokines play a role in the regulation of body mass through their influence on metabolism and energetic homeostasis.

Keywords: IL-6, IL-1, gene polymorphism, diabetes, inflammatory cytokines, obesity, TNF-alpha

Introduction

Obesity and related conditions constitute one of the most important social problems in developed societies leading to increased incidence of civilization diseases. Obesity is a disorder determined multifactorially, including a significant pathophysiological role of genetic factors. Genetic constitution may influence up to 40% of obesity causes, as numerous genes influence food uptake and energy expending mechanisms [1-3].

Obesity may be described as an energetic homeostasis disorder caused by excessive energy supply in relation to the organism's demand. In consequence, it leads to excessive energy storage in the form of fat tissue. Overweight and obesity are described as increase of body mass over accepted standards. The increase of body fat amount is due to the hypertrophy of adipocytes filled with triglycerides. Obesity may have various etiology. Usually, both genetic predisposition and environmental factors are involved.

A significant relation between genetic factors and obesity development was confirmed in a representative group of mono- and dizygotic twins as well as in children and their biological parents. The correlation between the mean BMI in monozygotic twins was 0.74, while in dizygotic twins it achieved 0.32. This evidence has led to the hypothesis that hereditariness of this feature ranges between 50 and 90% [4,5].

The genetic factors are largely modified by environmental factors, which seem to have a decisive effect on individual phenotype [2]. No single gene responsible individually and directly for obesity development has been identified. Hence, the problem should be examined as a complex relation of many genetic factors which acting simultaneously can exert specific phenotypic outcomes. Apart from rare mutations, the commonest genetic changes are gene polymorphisms. Single nucleotide change in both exons and promoter regions can lead to gene transcription abnormalities and, in consequence, to defects in protein function [6].

Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF) may substantially influence obesity development and are associated with metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes [7]. These cytokines significantly regulate energetic homeostasis and lipid-carbohydrate metabolism [8,9]. A diverse expression of these mediators was found in subcutaneous and intraperitoneal adipocytes [10,11]. It is probable that the increase of proinflammatory cytokines concentration associated with obesity can be connected with polymorphic changes in genes able to modify expression of these cytokines. It has been shown that IL-6 plays a significant role in regulation of lipid metabolism and influences energy expenditure processes. G174C polymorphism site is localized in promoter region and influences IL-6 expression level [10,12]. TNF plays a similar role in adipose tissue metabolism. TNF concentration among others depends on polymorphic changes in TNF genes. Allele A in G308A is related with twofold higher gene expression level, what results in increase of TNF production [11]. IL-1, another proinflammatory cytokine, may play a role in body mass regulation. Similarly to IL-6 and TNF, the influence of IL-1 on lipid metabolism and energetic homeostasis seems to be connected with cytokine level in the organism. Allele T (homozygotic) in +C3954T causes four-fold higher IL-1beta production in comparison to other alleles [8].

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the influence of polymorphism located in the promoter region of proinflammatory cytokine genes (IL-6 G174C; IL-1 C3954T; TNF-alpha G308A) on the development of obesity and related anthropomorphic characteristics in children.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study protocol was approved by a local Ethics Committee. All enrolled children and their parents gave informant consent for the participation in the study.

Fifty obese children with BMI (weight/height2) > 95th percentile for age and sex reference values who were sequentially recruited from an outpatient endocrinology clinic at the Warsaw Medical University Children's Hospital were enrolled into the study. The group consisted of 27 boys aged 10-17 years (mean age 13.8 ± 0.4SE) and 23 girls aged 10-17 years (mean 13.7 ± 0.5). A control group consisted of 55 children with normal weight (BMI < 85th percentile for age and sex reference values). The control group consisted of age-matched 27 boys and 28 girls, who underwent routine control check-ups.

Genetic Tests

Genomic DNA isolation was performed using Genomic Midi AX (A&A Biotechnology, Gdynia, Poland). DNA fragments amplification was performed using PCR method with appropriate starters. Polymorphisms were identified using PCR-RFLP technique (see details in Table 1). PCR products were digested with appropriate restriction enzymes: for IL-6 G174C - LweI and for TNF-alfa G308A - NcoI (Table 2).

Table 1.

PCR conditions for each gene.

| PCR stage | IL-6 | TNF | IL-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial denaturation | 94°C 10 min |

94°C 3 min |

94°C 4 min |

| Denaturation | 94°C 1 min |

94°C 1 min |

94°C 30 s |

| Annealing | 55°C 35 s |

60°C 1 min |

63°C 30 s |

| Elongation | 72°C 1 min |

72°C 1 min |

72°C 30 s |

| Cycles number | 35 | 36 | 35 |

| Final elongation | 72°C 10 min |

72°C 5 min |

72°C 10 min |

Table 2.

Restriction enzymes digestion conditions.

| Enzyme | # of units (U) |

Time (hours) |

Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LweI | 1 | 24 | 37 |

| NcoI | 2 | 24 | 37 |

| TaqI | 2 | 3 | 65 |

Statistical Elaboration

Frequency of distribution analysis was performed with Chi2 test. Significance of differences was tested with Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05. The results were processed statistically using Statgraphics 4.0 plus and Statistica 6.0 software. The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test was applied to evaluate genotype frequencies.

Results

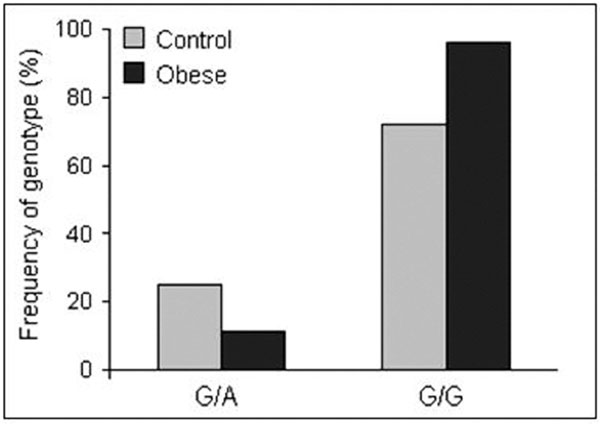

Statistical analysis of genetic data shows that two of the three examined polymorphisms correlated with the presence of obesity in children. We found differences in the frequency of G308A polymorphism in the TNF promoter region in obese children in comparison with children with a normal body mass. Allele A in G/A heterozygotes was more frequent in the obese group. A significant correlation was found in all analyzed groups (P = 0.04) (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Frequency of genotypes in G308A site of the TNF gene in the obese and non-obese children.

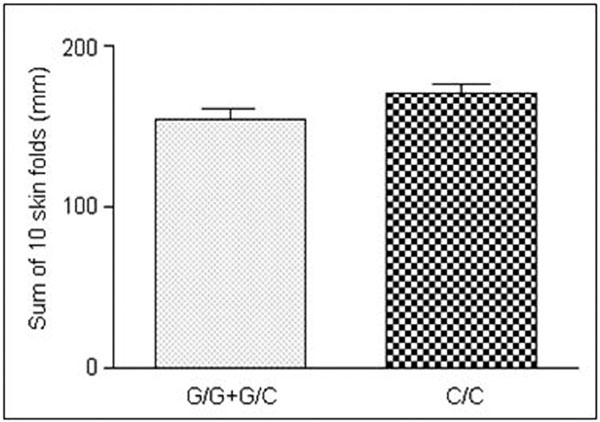

As far as G174C polymorphism in the IL-6 gene promoter is concerned, C allele was more frequent in obese children. The differences ranging from 10 to 20%, however, were statistically insignificant. In the studied population, C3954C site in the IL-1 gene promoter analysis showed no correlation with obesity development. The analyzed polymorphisms did not significantly influence the anthropomorphic parameters, such as BMI, waist or hips circumference. However, we found that changes in G174C polymorphic site in the IL-6 gene in obese girls were related to the sum of 10 skin fold thickness measurements. The presence of allele C in the promoter region of IL-6 gene in both C/C homozygotes and G/C heterozygotes was connected to a significant increase in the sum of 10 skin fold thickness measurements in obese girls (P = 0.03) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Differences between the sums of 10 skin fold thickness measurements in obese girls in relation to the genotype in G174C polymorphic site.

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the relation between three genetic polymorphisms in the promoter regions of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF, on one hand and the obesity in children, on the other. The results seem to confirm a hypothetical relation between the IL-6 genotype and obesity development [12]. The connection between G174C polymorphism and body mass regulation is influenced by certain alleles affecting the cytokine expression levels [13]. The analyzed polymorphism is localized in the promoter region, where transcription factors frequently exert their functions. G174C polymorphism influences the energy expenditure processes in different ways. The process can be regulated centrally via the IL-6 expression in the hypothalamus. In vitro studies show that knock-out mice for IL-6 gene increased their energy expenditure rate several times after administration of exogenous IL-6 to the central nervous system. Interestingly, the phenomenon was not observed when IL-6 was administered peripherally [14]. In humans, high level of proinflammatory cytokines (including IL-6) and their high expression in the brain lead to an increase in basal energy expenditure and may cause cachexia [15]. Peripheral administration of IL-6 causes an increase in basal metabolic rate and in the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. The increase of this activity is closely related to the administered dose of IL-6. This observation may indicate that the hypothalamic hormones, through corticotropin release, can mediate both processes [16]. The influence of IL-6 on energy expenditure can also be explained by enhanced adrenergic stimulation. It has been shown that IL-6 accelerates heart rate, increases norepinephrine level, and stimulates sympathetic nervous system, being the main efferent pathway able to regulate energy expenditure [17-19]. Moreover, sympathetic neurons are able to produce IL-6. The IL-6 receptor is expressed on their surface and hence they are susceptible to its function [20]. In patients with renal cancer, IL-6 administration causes an increase in norepinephrine level and basal energy expenditure [21]. The parallel hypothesis assumes that IL-6 function may also be enhanced by leptin [22].

Subsequently, the polymorphisms G308A in the TNF gene promoter region may influence overweight or obesity development. In obese children, A allele was significantly more frequent in comparison with the control group. A correlation between this polymorphism and obesity is probably caused by the influence of the polymorphism on cytokine expression. Some authors claim that TNF is able to impair lipid metabolism leading to hypertriglyceridemia, decreasing lipoprotein lipase activity, and inducing de novo synthesis of fatty acids in the liver [23]. Moreover, TNF is able to impair carbohydrates metabolism via decreased insulin-stimulated autophosphorylation and decreased activation of insulin-receptor tyrosine kinase in muscles and in adipose tissue [24,25]. This effect can be interpreted as additional evidence confirming the correlation between TNF and obesity.

The assessment of the frequency of C3954T polymorphic changes in the promoter region of IL-1 gene showed no direct connection between the polymorphism and obesity. Here, we found no significant differences between the obese and control groups.

The mechanism of a relationship between IL-1beta gene polymorphisms and obesity development has not been unambiguously determined to-date. Some authors suggest that T allele heterozygotes, in +3954 site, are connected with a four-fold higher secretion of IL-1 in comparison with C/C homozygotes [26,27]. Nevertheless, the described correlation of IL-1 and body mass seems to be caused by an indirect effect of this cytokine. The IL-1 can influence lipid metabolism indirectly [28]. IL-1 secretion is regulated by TNF synthesized by adipose tissue. An increase in TNF secretion in overgrown adipose tissue can stimulate adipocytes to produce IL-1beta. In turn, IL-1beta may influence the TNF expression and it shows a synergistic effect with TNF [29]. The effect of IL-1 on lipid metabolism depends on inhibition of lipoprotein lipase activity [30]. In vitro studies show that this cytokine is able to modify adipocytes function via inhibition of their maturation and inhibition of proteins involved in fatty acids transport within adipose tissue [31]. Another potential role of IL-1beta in obesity is related to its effect on leptin synthesis. Bruun et al. [32] found that both TNF and IL-1 are able to regulate leptin expression and secretion.

In conclusion, the examined polymorphisms of proinflammatory cytokines play a role in the regulation of body mass through their influence on metabolism and energy homeostasis. None of the analyzed factors can be used as an explicit marker of the risk for obesity. Nonetheless, mutual relations between studied cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, and TNF) concerning their expression and regulation are of great importance.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Supported by an intramural grant of Warsaw Medical University, Warsaw, Poland.

References

- Comuzzie AG, Blangero J, Mahaney MC, Haffner SM, Mitchell BD, Stern MP, MacCluer JW. Genetic and environmental correlations among hormone levels and measures of body fat accumulation and topography. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:597–600. doi: 10.1210/jc.81.2.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes HH, Neale MC, EaVes L. Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav Genet. 1997;27:325–351. doi: 10.1023/A:1025635913927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ. An adoption study of human obesity. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:193–198. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601233140401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pociot F, Molvig J, Wogensen L, Worsaae H, Nerup A. TaqI polymorphism in the human interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta) gene correlates with IL-1 beta secretion in vitro. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992;22:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison DB. The hetitability of body mass index among an international sample of monozygotic twins reared apart. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:501–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popko K, Gorska E, Wasik M, Stoklosa T, Plywaczewski R, Winiarska M, Gorecka D, Sliwinski P, Demkow U. Frequency of distribution of lepton receptor gene polymorphism in obstructive sleep apnea patients. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;58(Suppl 5):551–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruhbeck G, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Muruzabal FJ, Burrel MA. The adipocyte: a model for integration of endocrine and metabolic signaling in energy metabolism regulation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol. 2001;280:827–847. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.6.E827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld C, Feingold KR. The metabolic effects of tumor necrosis factor and other cytokines. Biotherapy. 1991;3:143–158. doi: 10.1007/BF02172087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed-Ali V, Pinkney JH, Coppack SW. Adipose tissue as an endocrine and paracrine organ. Int J Obes. 1998;22:1145–1158. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greengerg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 1998;83:847–850. doi: 10.1210/jc.83.3.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hube F, Birgel M, Lee YM, Hauner H. Expression pattern of tumor necrosis factor in subcutaneous and omental human adipose tissue: role of obesity and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29:672–678. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popko K, Gorska E, Potapinska O, Wasik M, Stoklosa T, Plywaczewski R, Winiarska M, Gorecka D, Sliwinski P, Popko M, Szwed T, Demkow U. Frequency of distribution of cytokines IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-alfa gene polymorphism in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(Suppl 6):607–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman D, Faulds G, Jeffery R, Mohamed Ali V, Yudkin YS, Humphries S, Woo P. The effect of novel polymorphism in the interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene on IL-6 transcription and an association with systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1369–1376. doi: 10.1172/JCI2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallenius V, Wallenius K, Ahren B, Rudling M, Carlsten H, Dickson SL, Ohlsson C, Jansson J-O. Interleukin-6 deficient mice develop mature-onset obesity. Nature Med. 2002;8:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plata-Salaman CR. Central nervous system mechanisms contributing to the cachexia-anorexia syndrome. Nutrition. 2000;16:1009–1012. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigos C, Papanicolaou DA, Defensor R, Mitsidis CS, Kyrou I, Chrousos GP. Dose effects of recombinant human interleukin-6 on pituitary hormone secretion and energy expenditure. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;66:54–62. doi: 10.1159/000127219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Real JM, Vayreda M, Richart C, Gutierrez C, Broch M, Vendrell J, Ricart W. Circulating interleukin-6 levels, blood pressure, and insulin sensitivity in apparently healthy men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2001;86:1154–1159. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.3.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolaou DA, Petrides JS, Tsigos C, Bina S, Kalogeras KT, Wilder R, Gold PW, Deuster PA, Chrousos GP. Exercise stimulates interleukin-6 secretion: inhibition by glucocorticoids and correlation with catecholamines. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E601–E605. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.3.E601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torpy DJ, Papanicolaou DA, Lotsikas AJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Pillemer SR. Responses of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to interleukin-6: a pilot study in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:872–880. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<872::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marz P, Cheng JG, Gadient RA, Patterson PH, Stovan T, Otten U, Rose-John S. Sympathetic neurons can produce and respond to interleukin 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:3251–3256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stouthard JM, Romijn JA, Van der Poll T, Endert E, Klein S, Bakker PJ, Veenhof CH, Sauerwein HP. Endocrinologic and metabolic effects of interleukin-6 in humans. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:E813–E819. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.5.E813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum M, Murphy EM, Heymsfield SB, Matthews DE, Leiber RL. Low dose leptin administration reverses effects of sustained weight-reduction on energy expenditure and circulating concentrations of thyroid hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2002;87:2391–2394. doi: 10.1210/jc.87.5.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Role of cytokines in inducing hyperlipidemia. Diabetes. 1992;41(Suppl 2):97–101. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.2.s97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS, Peraldi P, Budavari A, Ellis R, White MF, Spiegelman BM. IRS-1-mediated inhibition of insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity in TNF-alfa and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Science. 1996;271:665–668. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotomisligil GS, Murray DL, Choy LN, Spiegelman BM. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits signaling from the insulin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:4854–4858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pociot F, Molvig J, Wogensen L, Worsaae H, Nerup A. TaqI polymorphism in the human interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta) gene correlates with IL-1 beta secretion in vitro. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992;22:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pociot F, Ronningen KS, Bergholdt R, Lorencen T, Johannesen J, Ye K. Genetic susceptibility markers in Danish patients with type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes-evidence for polygenicity in men. Danish Study Group of Diabetes in Childhood. Autoimmunity. 1994;19:169–178. doi: 10.3109/08916939408995692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain JN, Cheema PS, Bahouth SW, Lloyd Hiler M. Resting release by human adipose tissue explants in primary culture. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:674–678. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HH, Kumar S, Barnett AH, Eggo MC. Dexamethasone inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced apoptosis and interleukin-1 beta release in human subcutaneous adipocytes and preadipocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2001;86:2817–2825. doi: 10.1210/jc.86.6.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler BA, Cerami A. Recombinant interleukin-1 suppresses lipoprotein lipase activity in 3T3-L1 cells. J Immunol. 1985;135:3969–3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memon RA, Feingold KR, Moser AH, Fuller J, Grunfeld C. Regulation of fatty acid transport protein and fatty acid translocase mRNA levels by endotoxin and cytokines. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E210–E217. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.2.E210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruun JM, Pedersen SB, Kristensen K, Richelsen B. Effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines on leptin production in human adipose tissue in vitro. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;190:91–99. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(02)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]