Abstract

Male obesity in reproductive-age men has nearly tripled in the past 30 y and coincides with an increase in male infertility worldwide. There is now emerging evidence that male obesity impacts negatively on male reproductive potential not only reducing sperm quality, but in particular altering the physical and molecular structure of germ cells in the testes and ultimately mature sperm. Recent data has shown that male obesity also impairs offspring metabolic and reproductive health suggesting that paternal health cues are transmitted to the next generation with the mediator mostly likely occurring via the sperm. Interestingly the molecular profile of germ cells in the testes and sperm from obese males is altered with changes to epigenetic modifiers. The increasing prevalence of male obesity calls for better public health awareness at the time of conception, with a better understanding of the molecular mechanism involved during spermatogenesis required along with the potential of interventions in reversing these deleterious effects. This review will focus on how male obesity affects fertility and sperm quality with a focus on proposed mechanisms and the potential reversibility of these adverse effects.

Keywords: male obesity, sperm, intergenerational, offspring, fertility

Introduction

Obesity is a global health problem that is reaching epidemic proportions with 1.6 billion adults classified as overweight and an extra 400 million adults classified as obese.1 It accounts for 7.5% of the total burden of disease2 costing approximately $21 billion dollars each year3 in Australia. Using Australia as an example of a westernised society, since the 1970s the rates of obesity in reproductive-age men has nearly tripled.4 This obesity is coincident with an increase in male infertilty as evidenced by the increase in couples seeking artificial reproductive technologies (ART) especially intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).5,6 There is increasing awareness that male obesity reduces sperm quality, in particular altering the physical and molecular structure of germ cells in the testes and mature sperm for a review see refs.7-9 Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that paternal health cues can be passed to the next generation with male age associated with an increase in autistic spectrum disorders10 and environmental exposures associated with increases in incidences of childhood disease.11,12 Alarmingly, there is now evidence in animal models that paternal obesity increases the suspectibility to obesity and diabetes in offspring, suggesting a possible mechanism in the amplification of these chronic diseases.13,14 Therefore, this review will focus on how male obesity affects fertility and sperm quality with a focus on proposed mechanisms for this altered spermatogenesis and the potential reversibility of these adverse effects.

Male Obesity Negatively Impacts Ferilization and Pregnancy

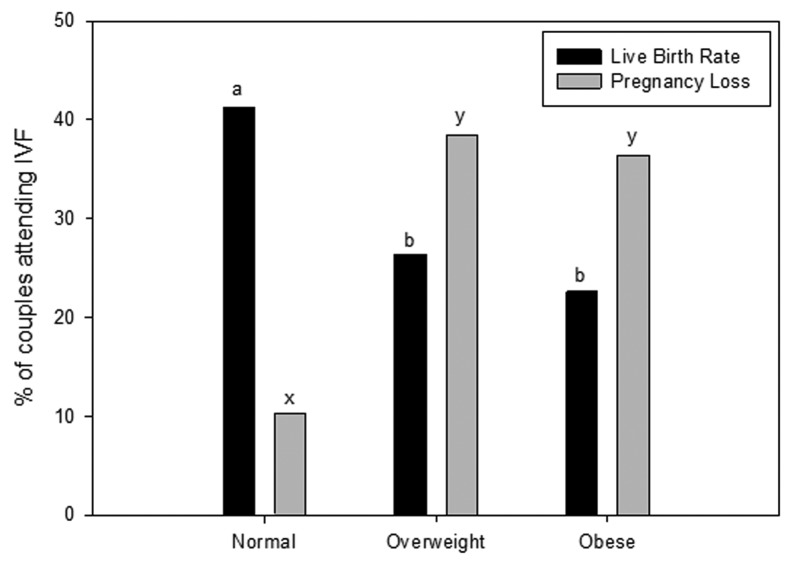

In the last 5–10 y it has been demonstrated that maternal obesity is associated with changes to the oocyte that negatively impact embryo development, which reduces subsequent pregnancy establishment after in vitro fertilization.15-17 Only recently in the last 2–3 y has the impact of an obese male partner on embryo development and pregnancy been assessed. Currently, there is mounting evidence that male obesity may be equally implicated in reducing fertility and embryo health. Couples with an overweight or obese male partner, with a female of normal body mass index (BMI), have increased odds ratio for increased time to conceive compared with couples with normal weight male partners.18,19 A limited number of clinical studies suggest similar outcomes. With obesity in males associated with decreased pregnancy rates and an increase of pregnancy loss in couples undergoing ART (Fig. 1).20-22 In part, this effect appears to be due to reduced blastocyst development, sperm binding and fertilization rates during in vitro fertilization (IVF), when the male partner is overweight or obese.20,23 However, more studies would be welcomed on this topic as limitations regarding sample size, cycle numbers, known factor infertility and the use of either IVF or ICSI are potential cofounders. This is suggested in the Keltz et al.22 study where they did not see the same changes to fertilization and embryo development when sperm were injected directly into the oocyte suggesting that the process of ICSI was by passing some impairment of the sperm to bind and fertilize. Although, this is not surprising as animal models of obesity have shown that the capacitation status and sperm binding ability of high fat diet mice were impaired compared with controls24,25 suggesting that post ejaculation maturation was altered and can be bypassed by ICSI. These embryology based findings which have established that male obesity at the time of conception impairs embryo health, therefore reducing implantation and live birth rates are paralleled by animal models of male obesity.26,27 This highly suggests a functional change to the molecular makeup of sperm that impacts directly on both sperm function but also on subsequent embryo development.

Figure 1. The effect of male obesity on pregnancy success in couples undergoing assisted reproductive technologies. Data taken from ref. 20 from 305 couples undergoing assisted reproductive technologies. BMI classification ranges, Normal (18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2), Overweight (25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2) and Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2). Data was analyzed through a multivariate analysis including both paternal and maternal BMI. Different letters denote significance at p < 0.05.

Paternal Obesity and Programming the Health of the Next Generation

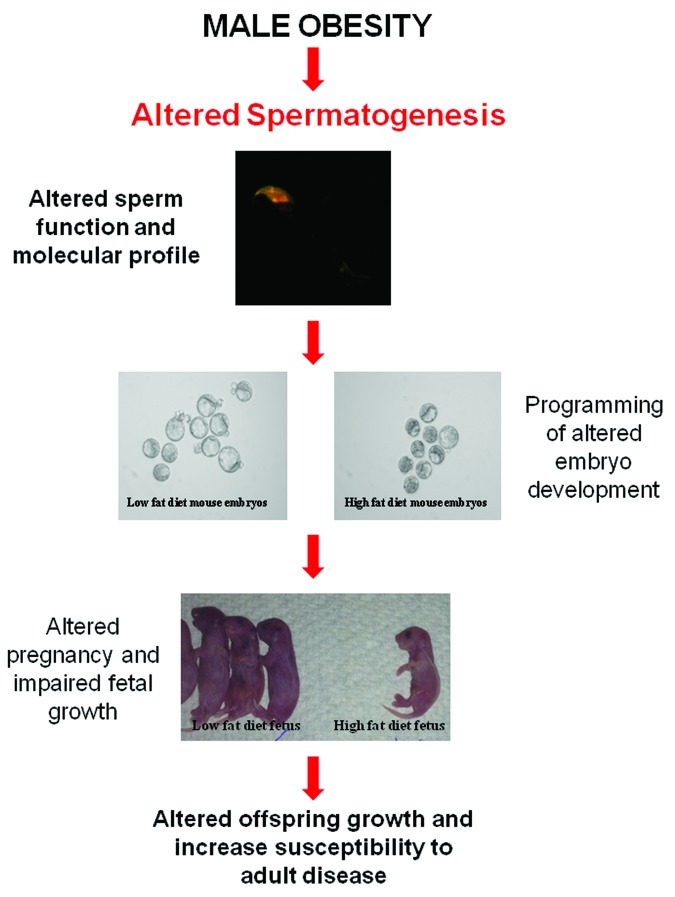

It is widely accepted that nutritional challenges during gestation (including maternal obesity) program molecular changes in the developing fetus that result in increased susceptibility to adult chronic diseases for a review see refs.28,29 However less is known about the influence of paternal obesity on childhood and adult health. Epidemiology studies have concluded that obese fathers are more likely to father an obese child.30,31 Although, it must be noted that the extent of the individual contributions of genetic, epigenetic and environmental cannot be separated in these association studies due to the common raising environment of both father and child. In light of this limitation, animal models of paternal obesity have been developed, which have more directly demonstrated marked changes to both the metabolic and reproductive health of subsequent offspring.13,14,32 Data from a rat model of diet induced obesity and reduced glucose tolerance demonstrated that paternal obesity compromised pancreatic function through altered gene transcription and islet cell dysfunction in female offspring.13 Subsequently, a mouse model of diet induced obesity without reduced glucose tolerance showed that paternal obesity compromised both first and second generation metabolic and reproductive health, with the female offspring additionally having increased fat mass demonstrating the first direct evidence of transmission of obesity.14,32 Significantly, F1 offspring had compromised gamete health with increased oxidative stress noted in sperm of male offspring and changes to oocyte mitochondrial function in female offspring.14 Taken together these data suggest that paternal obesity at the time of conception has a marked effect on offspring health therefore, directly implicating the sperm as the mediator for these changes, likely through a molecular mechanism that is transmitted to the resultant embryo and offspring (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Hypothesis for the effect of male obesity on spermatogenesis and how it impacts offspring health. Paternal obesity in rodents has been shown to negatively impact the metabolic13 and reproductive health14 of offspring. Sperm are the likely mediator for altering the developmental profile of the embryo,20,26 fetes20,26 and then resultant offspring.13,14,30,31 This change is likely to be molecular in nature99 and resulting from impaired spermatogenesis as a result of the obesity phenotype most likely occurring through changes to acetylation,35 methylation or non-coding RNA status of sperm .

Male Obesity on Traditional Sperm Parameters

There are several studies that have investigated the impact of male obesity on the traditional sperm parameters mandated by the world health organization (WHO), namely sperm concentration, sperm motility and sperm morphology (summarized in Table 1). There is some evidence that male obesity reduces sperm concentration with 15 out of 23 recent studies showing this (Table 1). In contrast, there are many contradicting reports with regard to sperm motility (with 7/19 showing decreased motility) and morphology (7/16 showing decreased normal forms) and it is currently unclear if male obesity has an impact on these parameters (Table 1). The discrepancies observed in the literature likely result from several limitations that are inherent in human studies. First, these studies can be confounded by lifestyle factors (ie smoking, alcohol consumption and recreational drug use) and co-pathologies, which can themselves impair sperm function. Second, the majority of studies originate from fertility clinics, where patient cohorts are frequently biased toward, sub-fertile men, which may also confound findings. Third, some studies rely on self-reporting of parameters such as lifestyle factors and BMI, which can lead to under reporting.

Table 1. Summary of the studies investigating paternal obesity and their effect on basic sperm parameters.

| Concentration | Motility | Morphology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain et al.146 |

Decreased |

No change |

n/a |

| Jensen et al.58 |

Decreased |

No change |

Decreased |

| Magnusdottir et al.147 |

Decreased |

Decreased |

n/a |

| Fejes et al.148 |

Decreased |

No change |

No change |

| Koloszar et al.149 |

Decreased |

n/a |

n/a |

| Kort et al.45 |

Decreased * |

Decreased * |

Decreased * |

| Qin et al.150 |

No change |

No change |

No change |

| Hammoud et al.151 |

Decreased |

Decreased |

Decreased |

| Pauli et al.56 |

No change |

No change |

No change |

| Aggerholm et al. 52 |

No change |

No change |

No change |

| Nicopoulou et al.152 |

Decreased |

n/a |

n/a |

| Hofny et al.153 |

Decreased |

Decreased |

Decreased |

| Stewart et al.154 |

Decreased |

n/a |

n/a |

| Chavarro et al.155 |

No change |

No change |

No change |

| Shayeb et al. 156 |

No change |

No change |

Decreased |

| Koloszar et al. 149 |

Decreased |

n/a |

n/a |

| Sekhavat et al. 157 |

Decreased |

Decreased |

n/a |

| Paasch et al. 54 |

Decreased |

No change |

Decreased |

| Tunc et al. 49 |

Decreased |

No change |

No change |

| Rybar et al.158 |

No change |

No change |

No change |

| Bakos et al. 20 |

Decreased |

Decreased |

No change |

| Kriegel et al.46 |

No change |

No change |

Decreased |

| Fariello et al. 48 | No change | Decreased | No change |

Significant for Normal Motile Sperm (NMS) = volume*concentration*%motility*%morphology.

Due to these difficulties in interpreting data from human studies, rodent models of male obesity have now been established to assess the impact of male obesity on sperm function, however it is necessary to be aware of the differences between species. These studies have demonstrated that males fed a high fat diet to induce obesity had reduced sperm motility and a decrease in percentage of sperm with normal morphology,24,27,33-35 however it should be noted that a number of these studies had significant reductions in testosterone24,25 and altered glucose homeostasis24 in their high fat diet groups which could be contributing to the results. Although there is some contention in the literature with regard to the effect male obesity has on traditional WHO sperm parameters, the changes reported indicate that the sperm are indeed compromised on more subtle levels.

Male Obesity on Sperm DNA Integrity and Oxidative Stress

While traditional WHO sperm parameters (sperm concentration and motility) are important measures of male fertility it is becoming increasingly apparent that the molecular structure and content of the sperm is equally important to the ability of a sperm to generate a healthy term pregnancy. Sperm DNA integrity is important for successful fertilization and normal embryonic development, as evidenced by sperm with poor DNA integrity being negatively correlated with successful pregnancies.36-40 Furthermore, sperm oxidative stress correlated with decreased sperm motility, increased sperm DNA damage, decreased acrosome reaction and lower embryo implantation rates following IVF.41-43 Numerous human studies as well as an animal study have determined that a relationship between obesity and reduced sperm DNA integrity exists, despite the use of a variety of different methodologies to measure sperm DNA integrity (TUNEL, COMET, SCSA, etc).33,44-48 Only two studies, one human49 and one rodent25,33 have directly linked levels of sperm oxidative stress with male BMI. Both studies concluded that a positive association between increasing BMI and increased sperm oxidative stress exists. In summary, there are conflicting reports about the interaction of male obesity with traditional WHO sperm parameters, but it is becoming clearer that male obesity is associated with significant changes to the molecular composition of sperm which has implications for its function but also for the resultant embryo.

Male Obesity and Altered Hormone Profiles

Spermatogenesis is a highly complex and selective processes whereby sperm are continually produced from the onset of puberty until death for a review see refs.50,51 This highly specialized process is under strict control from sex steroids, which in turn are regulated by the hypothalamus, pituitary and Leydig and Sertoli cells located in the testes for a review see refs.50,51 Examining the effect of obesity on this process is underpinned by the hypothesis that the hypothalamic pituitary gonadal (HPG) axis is deregulated by obesity.

Several studies document that increased male BMI is associated with reduced plasma concentrations of SHBG and therefore testosterone and a concomitant increased plasma concentration of estrogen.21,44,49,52-58 Decreased testosterone and increased estrogen have long been associated with sub fertility and reduced sperm counts by disrupting the negative feedback loop of the HPG axis and are therefore common markers of fertility for a review see ref.59 The Sertoli cell is the only somatic cell in direct contact with the developing germ cells by providing both physical and nutritional support and are therefore are of interest in male infertility. Adhesion of Sertoli cells to the developing germ cells is dependent on testosterone, with decreased testosterone leading to retention and phagocytosis of mature spermatids and therefore reducing sperm counts.60,61 Other hormones involved in the regulation of Sertoli cell function and spermatogenesis, such as FSH/LH ratios, inhibin B and Sex Hormone Binding Globulin levels have all been observed to be decreased in males with increased BMI for a review see refs.7-9 With mouse knockout models including both loss of FSH or FSH receptor associated with decreased testis weight, and sperm output due to a reduction in Sertoli cell numbers.62,63 Therefore it remains plausible that the decreased sperm counts observed in male obesity are at least in part a result of changes to the HPG axis through testosterone and estrogen and likely reduced Sertoli cell function.

Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome and Fertility

Hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia is a common occurrence in obese individuals and are constant confounding factors in many rodent studies of male obesity.13,24,27 Hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia have been shown to have an inhibitory effect on sperm quantity and quality and therefore could be attributing to the reduced fertility seen in obese men for a review see refs.64,65 With commonly altered makers of sperm function such as decreased count, increased reactive oxygen species and sperm DNA damage also seen in diabetic patients for a review see refs.65,66 High circulating levels of insulin is suggested as one possible mechanism for the above effects with increased insulin reducing the production of SHBG in the liver thereby indirectly increasing the amount of active unbound estrogens and testosterone (not bound by SHBG) in the blood stream.67 The decreased levels of SHBG to sustain homeostatic levels of testosterone could contribute to the decreased levels of testosterone and decreased sperm counts seen in these patients. Increasing levels of circulating glucose have also been shown to reduce the amount of LH released by the anterior pituitary in sheep68,69 and therefore could contribute to the impaired HPG axis and altered sperm parameters seen in diabetic and overweight and obese men. Additionally, there is emerging evidence that low testosterone levels can also induce aspects of metabolic syndrome and therefore obesity may not be the direct cause of reduced sperm counts seen in these men but a symptom of the same low testosterone.70-72

Interaction of Adipose Tissue with Hormonal Regulation

A working hypothesis proposed that elevated estrogens in obese men may in part result from the increased mass of white adipose tissue. White adipose tissue is responsible for aromatase activity and adipose derived hormones and adipokines, which are elevated in obese men.73 Aromatase cytochrome P450 enzyme, is produced by many tissues including adipose tissue and testicular Leydig cells, and in men activity converts testosterone to estrogens.74,75 Due to obesity increased influx of white adipose tissue it is suggested that elevated estrogen concentrations may result from an increased conversion of androgens to estrogens by white adipose tissue therefore contributing to the increased plasma estrogen levels seen.76-78 Another key hormone produced by white adipose tissue is leptin, which plays a pivotal role in the regulation of energy intake and expenditure for a review see refs.79,80 Leptin mainly targets receptors in the hypothalamus by counteracting the effects of neuropeptide Y. However leptin receptors have recently been discovered in ovaries and testes, functioning to regulate the HPG axis.81-85 Specifically, increased levels of leptin significantly decreased the production of testosterone from Leydig cells.86 Taken together this suggests that elevated leptin levels commonly found in obese males87 could alter the HPG axis, thus contributing to the decreased testosterone production observed.

Interaction of Adipose Tissue on Testicular Temperature

One side effect of obesity that may potentially contribute to altered sperm production/parameters is raised gonadal heat resulting from increased scrotal adiposity. The process of spermatogenesis is highly sensitive to heat, with optimal temperature ranging between 34–35°C in humans.88 Increased testicular heat is associated with reduced sperm motility, increased sperm DNA damage and increased sperm oxidative stress.89-91 Changes to testicular temperature can occur via a number of mechanisms such as physical disorders (ie varicoceles), increased scrotal adiposity or environmental disturbances (ie prolonged bike riding) and are associated with reduced sperm function and sub fertility.92-98 It is therefore not surprising that increased testicular heat caused by increased adiposity in obesity has been proposed as a possible mechanism. It is noteworthy that increased sperm DNA damage and oxidative stress are commonly impaired in obese patients and that a single study which investigated the surgical removal of scrotal fat reported an improvement in sperm parameters.95

Impact of Male Obesity on Molecular Aspects of Spermatogenesis

Recent data, which has shown that paternal health cues are transmitted to the next generation most likely via the sperm, has resulted in a renewed interest into the molecular function of sperm99 and has helped lead to our current hypothesis (Fig. 2). The mechanisms inducing changes to sperm molecular composition are yet to be determined in obese individuals. However, several studies examining transgenerational effects13,14 have proposed epigenetic modifications to the sperm through changes to non-coding RNA content, methylation and acetylation status which are changed in obese individuals for a review see refs.99,100 Additional reports suggest that the proteomic profiles of sperm also differ between obese and non obese men.46 It is now becoming increasingly accepted that the environment that the founder generation is exposed to impacts the phenotype of subsequent generations with the term ‘transgenerational epigenetic inheritance’ coined to reflect this phenomena.101,102 Rodent models of male diet induced obesity document impaired metabolic and reproductive phenotypes in F1 offspring13,14,32 and therefore suggest that transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is involved.

Methylation

Methylation of DNA and histones is dynamic during spermatogenesis and is vital for the normal processes of spermatogenesis and fundamental for a successful pregnancy. Changes to sperm methylation is required and essential for X chromosome inactivation during meiosis and for the establishment of paternally imprinted genes in sperm.103,104 Generally, hypermethylated DNA at promoter regions inhibits gene expression by excluding transcription factor binding. In contrast, hypomethylation generally allows increased access of transcription factors to the DNA and increases gene expression. It is estimated that 96% of the genomic CpGs in sperm DNA are usually methylated, although there are site specific variations of methylation in mature sperm.105

Analysis throughout human spermatogenesis has determined that DNA methyltransferase proteins (DNMT 1, 3A, 3B) are present during the spermatogenic cycle as knockout studies result in changes to sperm methylation and in some cases sperm function.106 The stage specific changes in nuclear localization of these three proteins during spermatogenesis coincides with the establishment of the methylation imprints in the spermatogonia. Subsequent maintenance of these imprints occurs throughout the remainder of spermatogenesis suggesting methylation imprints are key molecular events during spermatogenesis.107

There is some evidence that the methylation status of sperm DNA is associated with sub-fertility. Hypomethylation of imprinted genes and repeat elements in sperm have been linked with reduced pregnancy success and correlate with increased sperm DNA damage in males undergoing fertility treatment.108-111 Additionally, altered levels of methylation in the promoter regions of genes such as MTHFR are associated with decreased sperm function. Further, imprinted regions such as H19 and ALU repeat elements are more likely to be hypomethylated in subfertile men.110,111

Environmental exposures have also been linked with changes to methylation status of sperm. Toxins such as exposure to 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine, tamoxifen and chemotherapy agents disturb the de novo methylation activity in sperm as shown in animal models.112-114 This aberrant methylation was observed at imprinted regions such as Igf2 and H19. Subsequently this lead to a disruption of the DNA methylation reprogramming of the male pronucleus, which in turn increases post implantation pregnancy loss.112-114 Moreover, excessive alcohol consumption in men been associated with site-specific hypomethylation in sperm,115 a finding confirmed in animal models.116 Excessive alcohol consumption impacts negatively on offspring prenatal growth and also alters the methylation status of offspring DNA.117,118

To date there is little information as to the impact of obesity on the methylation status of DNA originating from male germ cells, however obesity has been shown to alter the methylation status of DNA originating from other tissues for a review see ref.119 Whether the metabolic and reproductive changes observed in offspring as well as reduced fertilization and increased pregnancy loss induced from paternal obesity results from alterations to de novo methylation patterns of developmental genes in the male germ line is yet to be determined.

Acetylation

Histone acetylation is vital for spermatogenesis to proceed and is necessary and essential for the removal of histones so they can be replaced by protamines during spermiogenesis. Furthermore, histone acetylation is essential to relax chromatin structure that allows for the repair of the DNA double and single strand breaks that result.120 Protamination is required to enable the tight packing of the DNA that occurs within the sperm head, which aids in the protection against DNA damage in the absence of normal cellular defenses that are greatly diminished by the shedding of the cytoplasm during epididymial transport. The histone to protamine transition is incomplete with roughly 1% of histones remaining in mature murine sperm.121 Curiously, up to 15% of histones are retained in human mature sperm.122

There is evidence that the retention of these histones during protamination is not random with key pluripotency regulating genes remaining histone bound (ie Nanog, Oct4 and Sprouty).123 Therefore these loci are capable of normal somatic cell histone modifications.123 Thus, alterations to histone acetylation at such loci due to environmental cues could result in epigenetic modifications to sperm that might form the basis of paternal programming of offspring.

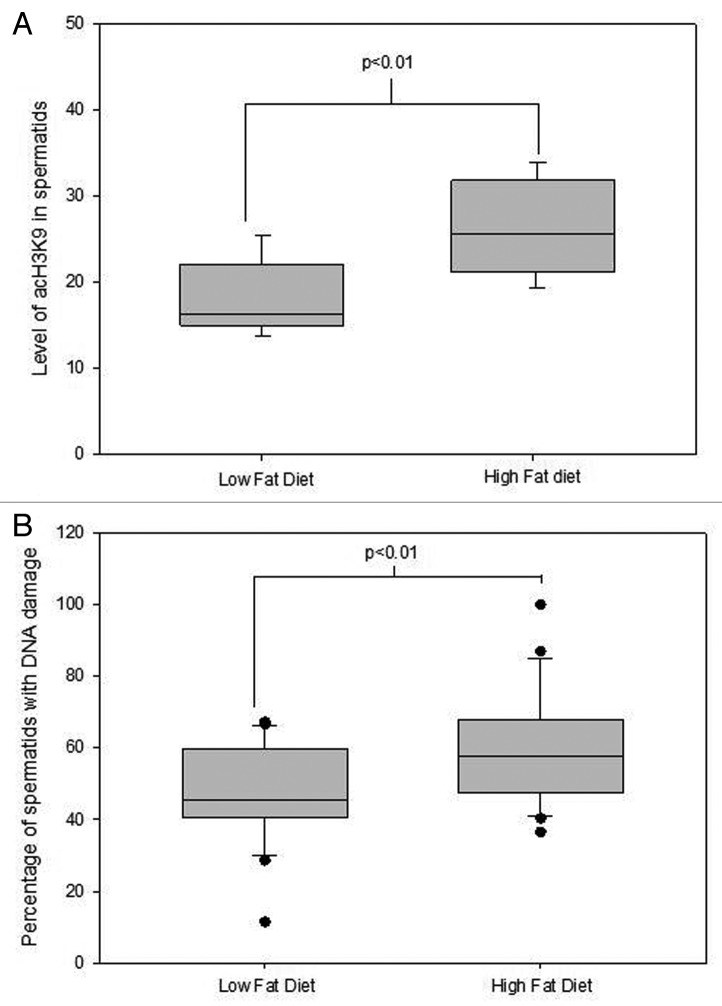

The N-terminus of histones is a key region attracting post translational modifications such as acetylation. Acetylated histones in mature sperm are thought to represent epigenetic marks capable of transmission to the oocyte during fertilization and regulate gene expression in early embryogenesis. Given that key pluripotency genes retain histones it is proposed that this is in readiness for immediate activation of expression of these genes post fertilization.123 Hyperacetylation of H4 and H3 is required for normal spermiogenesis and for appropriate replacement of histones by protamines during spermiogenesis. Studies exploring the roles of histone deacetylases (HDAC) found that germ cells treated with HDAC inhibitors, result in premature hyperacetylation of late round spermatids.124-126 The functional consequence of this early hyperacetylation is still to be fully understood, however studies indicate that an increased rate of DNA damage occurs as the result.125,127 Interestingly, male mice fed a high fat diet similarly displayed altered acetylation status in late round spermatids which also correlated with increased DNA damage in the germ cells35 (Fig. 3). Alterations to sperm histone acetylation correlates with poor protamination, which in turn positively correlates with increased DNA damage in mature sperm and therefore potentially contributes to poor sperm parameters observed in obese males.128-130 Taken together, alterations to histone acetylation represent a potential epigenetic basis for the programming observed in resultant embryos and sired by obese males.106

Figure 3. The effect of diet induced obesity in C57BL6 mice on Acetylation and DNA damage levels in spermatids during protanimation. Data taken from.35 Data was analyzed through a univariate general linear model with replicate fitted as a covariate and mouse ID as a random factor. Correlation data was determined by a Pearson’s Rho. (A) The effect of diet induced obesity in mice on acetylation levels of H3K9 in elongating spermatids representative of > 120 spermatids from at least 5 mice per treatment group. (B) The effect of diet induced obesity in mice on DNA damage levels in elongating spermatids representative of > 4000 spermatids from at least 5 mice per treatment group. There was a negative correlation found between acetylation levels of H3K9 and DNA damage levels in round spermatids R2 = 0.60, p = 0.023 n = 8 animals.

RNA and small non-coding RNAs

The long held dogma was that sperm were transcriptionally and translationally silent and that the small amounts of RNA contained were thought to be remnants left over from spermatogenesis.131 However, it is now evident that mature sperm contain a regulated suite of both mRNA and other non-coding RNA that are suggested to be important for normal fertilization and subsequent embryonic development, with active transcription and translation occurring in the sperm’s mitochondria.132-135 Although it is not yet clear what the precise role these RNAs play, it has been empirically proven that these RNA can cause phenotypic change in resultant offspring after injection into oocytes, albeit at amounts that far exceed biological concentrations.136 While to date there is little known about mRNA abundance in sperm from obese males, one rodent model of obesity and diabetes has shown significant differences in several mRNA within testes compared with lean controls.27

Mature sperm also contain significant levels of small non-coding RNAs including silencing RNAs (siRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs) and in a recent study piwi-interacting RNA (piRNAs).137 Small non coding RNAs are 20–22 nucleotides (nt) in length and contain an abundance of stop codons and generally lack open reading frames.138 They regulate at the level of both transcription and translation via control of chromatin organization, mRNA stability and protein synthesis. Interestingly, microRNAs also regulate methylation in several tissues.139 Indeed, hypomethylation of repeat elements in the male germline has been associated with an increase in miR-29, which is predicted to downregulate DNMT3a, a protein necessary for establishing genomic methylation.140

It is apparent that these RNAs have a role in the oocyte during fertilization and in embryo development, fetal survival and offspring phenotype. Alteration of microRNA abundance in the male pronucleus of recently fertilised zygotes produce offspring of phenotypes of variable severity depending on the ratios of microRNAs injected.141 One preliminary study reported that the microRNA profile is altered in sperm as a result of male obesity in rodents.142 However, the impact of these changes on fertilization and embryo health remains to be determined.

Reversibility

While it is becoming clearer that male obesity has negative impacts on fertility, sperm function and long-term impacts on the health burden of the offspring It is equally clear that simple interventions such as changes to diet and/or exercise can reverse both the disease state and the offspring outcomes. There is emerging evidence that intake of selenium enriched probiotics by obese rodents improves both their metabolic health and fertility measures (sperm count and motility).143 Furthermore, our recent studies of diet and exercise interventions in an obese mouse model have determined that sperm function is correlated with the metabolic health of the individual.24 Improvements in metabolic health such as a return of plasma concentrations of glucose, insulin and cholesterol to normal levels result in improvements in sperm motility and morphology, concomitant with improvements to molecular composition such as reductions in oxidative stress and reduced DNA damage.24 To date there is little information about the impact of diet/exercise intervention in obese men with regard to semen parameters in the human. The largest study to date examined 43 obese men during a 14 week residential weight loss program and demonstrated significant improvements to both total sperm count and sperm morphology in men who lost the greatest amounts of weight.144 However, a recent case report of three patients who underwent bariatric surgery to achieve drastic weight loss demonstrated that sperm parameters worsened.145 These parameters remained poorer two months post surgery in all patients and only one patient had minimal improvements after two years.145 However, the impact of nutritional deficiencies that might persist even after surgical intervention, and metabolic health of these men were not studied. The full potential of diet and exercise interventions to restore the fertility of obese men and improve embryo and offspring outcomes are yet to be fully characterized.

Conclusion

There is emerging evidence that male obesity negatively impacts fertility through changes to hormone levels, as well as direct changes to sperm function and sperm molecular composition. Data from animal models implicate the nutritional status of the father as setting the developmental trajectory of resultant offspring. Both male and female offspring born to fathers with sub-optimal nutrition have a constellation of metabolic and reproductive health pathologies. Nutritionally induced alterations to both the physical and molecular composition of sperm evidently implicates it as the mediator of these impacts on both the father’s fertility and the health of the next generation, sparking renewed research interest in spermatogenesis and the detrimental effects of obesity. Additionally with the recent animal studies showing that simple diet and exercise interventions can be used to reverse the damaging effects of obesity on sperm function, understanding the impacts will be important for the development of public health messages for men considering fatherhood.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/spermatogenesis/article/21362

References

- 1.Nguyen DM, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begg SVT, Barker B, Stevenson C, Stanley L, Lopez AD. The burden of disease and injury in Australia 2003. Canberra: AIHW, 2007:337. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aitken RJ, Allman-Farinelli MA, King LA, Bauman AE. Current and future costs of cancer, heart disease and stroke attributable to obesity in Australia - a comparison of two birth cohorts. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon T, Waters AM. A growing problem. Trends and patterns in overweight and obesity among adults in Australia 1980 to 2001. 2003:AIHW bulletin no. 8, AUS 36; 19pp. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunderam S, Chang J, Flowers L, Kulkarni A, Sentelle G, Jeng G, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Assisted reproductive technology surveillance--United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YA, Dean, J., Badgery-Parker, T. and Sullivan, E. A. Assisted reproduction technology in Australia and New Zealand 2006. Assisted Reproduction Technology series 2008; 12.

- 7.MacDonald AA, Herbison GP, Showell M, Farquhar CM. The impact of body mass index on semen parameters and reproductive hormones in human males: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:293–311. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teerds KJ, de Rooij DG, Keijer J. Functional relationship between obesity and male reproduction: from humans to animal models. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:667–83. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du Plessis SS, Cabler S, McAlister DA, Sabanegh E, Agarwal A. The effect of obesity on sperm disorders and male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:153–61. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hultman CM, Sandin S, Levine SZ, Lichtenstein P, Reichenberg A. Advancing paternal age and risk of autism: new evidence from a population-based study and a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:1203–12. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang JS. Parental smoking and childhood leukemia. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:103–37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper R, Hyppönen E, Berry D, Power C. Associations between parental and offspring adiposity up to midlife: the contribution of adult lifestyle factors in the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:946–53. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng SF, Lin RC, Laybutt DR, Barres R, Owens JA, Morris MJ. Chronic high-fat diet in fathers programs β-cell dysfunction in female rat offspring. Nature. 2010;467:963–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fullston T, Palmer NO, Owens JA, Mitchell M, Bakos HW, Lane M. Diet-induced paternal obesity in the absence of diabetes diminishes the reproductive health of two subsequent generations of mice. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1391–400. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinborg A, Gaarslev C, Hougaard CO, Nyboe Andersen A, Andersen PK, Boivin J, et al. Influence of female bodyweight on IVF outcome: a longitudinal multicentre cohort study of 487 infertile couples. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23:490–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marquard KL, Stephens SM, Jungheim ES, Ratts VS, Odem RR, Lanzendorf S, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome and maternal obesity affect oocyte size in in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles. Fertil Steril 2011; 95:2146-9, 9 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Veleva Z, Tiitinen A, Vilska S, Hydén-Granskog C, Tomás C, Martikainen H, et al. High and low BMI increase the risk of miscarriage after IVF/ICSI and FET. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:878–84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen RH, Wilcox AJ, Skjaerven R, Baird DD. Men’s body mass index and infertility. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2488–93. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramlau-Hansen CH, Thulstrup AM, Nohr EA, Bonde JP, Sørensen TI, Olsen J. Subfecundity in overweight and obese couples. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1634–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakos HW, Henshaw RC, Mitchell M, Lane M. Paternal body mass index is associated with decreased blastocyst development and reduced live birth rates following assisted reproductive technology. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1700–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinz S, Rais-Bahrami S, Kempkensteffen C, Weiske WH, Miller K, Magheli A. Effect of obesity on sex hormone levels, antisperm antibodies, and fertility after vasectomy reversal. Urology. 2010;76:851–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keltz J, Zapantis A, Jindal SK, Lieman HJ, Santoro N, Polotsky AJ. Overweight men: clinical pregnancy after ART is decreased in IVF but not in ICSI cycles. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:539–44. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9439-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang K, Walters RC, Lipshultz LI. Contemporary concepts in the evaluation and management of male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8:86–94. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer NO, Bakos HW, Owens JA, Setchell BP, Lane M. Diet and exercise in an obese mouse fed a high-fat diet improve metabolic health and reverse perturbed sperm function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E768–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00401.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakos HW, Mitchell M, Setchell BP, Lane M. The effect of paternal diet-induced obesity on sperm function and fertilization in a mouse model. Int J Androl. 2011;34:402–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2010.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell M, Bakos HW, Lane M. Paternal diet-induced obesity impairs embryo development and implantation in the mouse. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1349–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghanayem BI, Bai R, Kissling GE, Travlos G, Hoffler U. Diet-induced obesity in male mice is associated with reduced fertility and potentiation of acrylamide-induced reproductive toxicity. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:96–104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.078915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li M, Sloboda DM, Vickers MH. Maternal obesity and developmental programming of metabolic disorders in offspring: evidence from animal models. Exp Diabetes Res 2011; 2011:592408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Li CC, Maloney CA, Cropley JE, Suter CM. Epigenetic programming by maternal nutrition: shaping future generations. Epigenomics. 2010;2:539–49. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danielzik S, Langnäse K, Mast M, Spethmann C, Müller MJ. Impact of parental BMI on the manifestation of overweight 5-7 year old children. Eur J Nutr. 2002;41:132–8. doi: 10.1007/s00394-002-0367-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li L, Law C, Lo Conte R, Power C. Intergenerational influences on childhood body mass index: the effect of parental body mass index trajectories. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:551–7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell M, Fullston T, Palmer NO, Bakos HW, Owens JA, Lane M. The effect of paternal obesity in mice on reproductive and metabolic fitness of F1 male offspring. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2010;22:21–21. doi: 10.1071/SRB10Abs103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakos HW, Mitchell M, Setchell BP, Lane M. The effect of paternal diet-induced obesity on sperm function and fertilization in a mouse model. Int J Androl 2010; (Epub date 2010/07/24) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Fernandez CD, Bellentani FF, Fernandes GS, Perobelli JE, Favareto AP, Nascimento AF, et al. Diet-induced obesity in rats leads to a decrease in sperm motility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmer NO, Fullston T, Mitchell M, Setchell BP, Lane M. SIRT6 in mouse spermatogenesis is modulated by diet-induced obesity. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2011;23:929–39. doi: 10.1071/RD10326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar K, Deka D, Singh A, Mitra DK, Vanitha BR, Dada R. Predictive value of DNA integrity analysis in idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss following spontaneous conception. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10815-012-9801-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakos HW, Thompson JG, Feil D, Lane M. Sperm DNA damage is associated with assisted reproductive technology pregnancy. Int J Androl. 2008;31:518–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallagher JE, Vine MF, Schramm MM, Lewtas J, George MH, Hulka BS, et al. 32P-postlabeling analysis of DNA adducts in human sperm cells from smokers and nonsmokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2:581–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brahem S, Mehdi M, Landolsi H, Mougou S, Elghezal H, Saad A. Semen parameters and sperm DNA fragmentation as causes of recurrent pregnancy loss. Urology. 2011;78:792–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomson LK, Zieschang JA, Clark AM. Oxidative deoxyribonucleic acid damage in sperm has a negative impact on clinical pregnancy rate in intrauterine insemination but not intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:843–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aitken RJ, Baker MA. Oxidative stress, sperm survival and fertility control. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;250:66–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aziz N, Saleh RA, Sharma RK, Lewis-Jones I, Esfandiari N, Thomas AJ, Jr., et al. Novel association between sperm reactive oxygen species production, sperm morphological defects, and the sperm deformity index. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:349–54. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zorn B, Vidmar G, Meden-Vrtovec H. Seminal reactive oxygen species as predictors of fertilization, embryo quality and pregnancy rates after conventional in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Int J Androl. 2003;26:279–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.2003.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chavarro JE, Toth TL, Wright DL, Meeker JD, Hauser R. Body mass index in relation to semen quality, sperm DNA integrity, and serum reproductive hormone levels among men attending an infertility clinic. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kort HI, Massey JB, Elsner CW, Mitchell-Leef D, Shapiro DB, Witt MA, et al. Impact of body mass index values on sperm quantity and quality. J Androl. 2006;27:450–2. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kriegel TM, Heidenreich F, Kettner K, Pursche T, Hoflack B, Grunewald S, et al. Identification of diabetes- and obesity-associated proteomic changes in human spermatozoa by difference gel electrophoresis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;19:660–70. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.La Vignera S, Condorelli RA, Vicari E, Calogero AE. Negative effect of increased body weight on sperm conventional and nonconventional flow cytometric sperm parameters. J Androl. 2012;33:53–8. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.110.012120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fariello RM, Pariz JR, Spaine DM, Cedenho AP, Bertolla RP, Fraietta R. Association between obesity and alteration of sperm DNA integrity and mitochondrial activity. BJU Int. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tunc O, Bakos HW, Tremellen K. Impact of body mass index on seminal oxidative stress. Andrologia. 2011;43:121–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sofikitis N, Giotitsas N, Tsounapi P, Baltogiannis D, Giannakis D, Pardalidis N. Hormonal regulation of spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;109:323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruwanpura SM, McLachlan RI, Meachem SJ. Hormonal regulation of male germ cell development. J Endocrinol. 2010;205:117–31. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aggerholm AS, Thulstrup AM, Toft G, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Bonde JP. Is overweight a risk factor for reduced semen quality and altered serum sex hormone profile? Fertil Steril. 2008;90:619–26. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramlau-Hansen CH, Hansen M, Jensen CR, Olsen J, Bonde JP, Thulstrup AM. Semen quality and reproductive hormones according to birthweight and body mass index in childhood and adult life: two decades of follow-up. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:610–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paasch U, Grunewald S, Kratzsch J, Glander HJ. Obesity and age affect male fertility potential. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:2898–901. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fejes I, Koloszár S, Závaczki Z, Daru J, Szöllösi J, Pál A. Effect of body weight on testosterone/estradiol ratio in oligozoospermic patients. Arch Androl. 2006;52:97–102. doi: 10.1080/01485010500315479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pauli EM, Legro RS, Demers LM, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Lee PA. Diminished paternity and gonadal function with increasing obesity in men. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:346–51. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hofny ER, Ali ME, Abdel-Hafez HZ, Kamal Eel-D, Mohamed EE, Abd El-Azeem HG, et al. Semen parameters and hormonal profile in obese fertile and infertile males. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:581–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jensen TK, Andersson AM, Jørgensen N, Andersen AG, Carlsen E, Petersen JH, et al. Body mass index in relation to semen quality and reproductive hormones among 1,558 Danish men. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:863–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Handelsman DJ, Swerdloff RS. Male gonadal dysfunction. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;14:89–124. doi: 10.1016/S0300-595X(85)80066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kerr JB, Millar M, Maddocks S, Sharpe RM. Stage-dependent changes in spermatogenesis and Sertoli cells in relation to the onset of spermatogenic failure following withdrawal of testosterone. Anat Rec. 1993;235:547–59. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092350407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kerr JB, Savage GN, Millar M, Sharpe RM. Response of the seminiferous epithelium of the rat testis to withdrawal of androgen: evidence for direct effect upon intercellular spaces associated with Sertoli cell junctional complexes. Cell Tissue Res. 1993;274:153–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00327996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dierich A, Sairam MR, Monaco L, Fimia GM, Gansmuller A, LeMeur M, et al. Impairing follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) signaling in vivo: targeted disruption of the FSH receptor leads to aberrant gametogenesis and hormonal imbalance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13612–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kumar TR, Wang Y, Lu N, Matzuk MM. Follicle stimulating hormone is required for ovarian follicle maturation but not male fertility. Nat Genet. 1997;15:201–4. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kasturi SS, Tannir J, Brannigan RE. The metabolic syndrome and male infertility. J Androl. 2008;29:251–9. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.003731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.La Vignera S, Condorelli R, Vicari E, D’Agata R, Calogero AE. Diabetes mellitus and sperm parameters. J Androl. 2012;33:145–53. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.111.013193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amaral S, Oliveira PJ, Ramalho-Santos J. Diabetes and the impairment of reproductive function: possible role of mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2008;4:46–54. doi: 10.2174/157339908783502398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laing I, Olukoga AO, Gordon C, Boulton AJ. Serum sex-hormone-binding globulin is related to hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivity but not to beta-cell function in men and women with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 1998;15:473–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199806)15:6<473::AID-DIA607>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Clarke IJ, Horton RJ, Doughton BW. Investigation of the mechanism by which insulin-induced hypoglycemia decreases luteinizing hormone secretion in ovariectomized ewes. Endocrinology. 1990;127:1470–6. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-3-1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Medina CL, Nagatani S, Darling TA, Bucholtz DC, Tsukamura H, Maeda K, et al. Glucose availability modulates the timing of the luteinizing hormone surge in the ewe. J Neuroendocrinol. 1998;10:785–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1998.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haring R, Völzke H, Felix SB, Schipf S, Dörr M, Rosskopf D, et al. Prediction of metabolic syndrome by low serum testosterone levels in men: results from the study of health in Pomerania. Diabetes. 2009;58:2027–31. doi: 10.2337/db09-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akishita M, Fukai S, Hashimoto M, Kameyama Y, Nomura K, Nakamura T, et al. Association of low testosterone with metabolic syndrome and its components in middle-aged Japanese men. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:587–91. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kupelian V, Page ST, Araujo AB, Travison TG, Bremner WJ, McKinlay JB. Low sex hormone-binding globulin, total testosterone, and symptomatic androgen deficiency are associated with development of the metabolic syndrome in nonobese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:843–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wake DJ, Strand M, Rask E, Westerbacka J, Livingstone DE, Soderberg S, et al. Intra-adipose sex steroid metabolism and body fat distribution in idiopathic human obesity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:440–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meinhardt U, Mullis PE. The essential role of the aromatase/p450arom. Semin Reprod Med. 2002;20:277–84. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cohen PG. The hypogonadal-obesity cycle: role of aromatase in modulating the testosterone-estradiol shunt--a major factor in the genesis of morbid obesity. Med Hypotheses. 1999;52:49–51. doi: 10.1054/mehy.1997.0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ruige JB. Does low testosterone affect adaptive properties of adipose tissue in obese men? Arch Physiol Biochem. 2011;117:18–22. doi: 10.3109/13813455.2010.525239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kley HK, Deselaers T, Peerenboom H, Krüskemper HL. Enhanced conversion of androstenedione to estrogens in obese males. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;51:1128–32. doi: 10.1210/jcem-51-5-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cohen PG. Obesity in men: the hypogonadal-estrogen receptor relationship and its effect on glucose homeostasis. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70:358–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Machleidt F, Lehnert H. [Central nervous system control of energy homeostasis] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2011;136:541–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1274539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.González Jiménez E, Aguilar Cordero MJ, García García CdeJ, García López PA, Alvarez Ferre J, Padilla López CA. [Leptin: a peptide with therapeutic potential in the obese] Endocrinol Nutr. 2010;57:322–7. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mounzih K, Lu R, Chehab FF. Leptin treatment rescues the sterility of genetically obese ob/ob males. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1190–3. doi: 10.1210/en.138.3.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chehab FF, Mounzih K, Lu R, Lim ME. Early onset of reproductive function in normal female mice treated with leptin. Science. 1997;275:88–90. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D, Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E, et al. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 1996;382:250–2. doi: 10.1038/382250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Finn PD, Cunningham MJ, Pau KY, Spies HG, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. The stimulatory effect of leptin on the neuroendocrine reproductive axis of the monkey. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4652–62. doi: 10.1210/en.139.11.4652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pinilla L, Seoane LM, Gonzalez L, Carro E, Aguilar E, Casanueva FF, et al. Regulation of serum leptin levels by gonadal function in rats. Eur J Endocrinol. 1999;140:468–73. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1400468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Caprio M, Isidori AM, Carta AR, Moretti C, Dufau ML, Fabbri A. Expression of functional leptin receptors in rodent Leydig cells. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4939–47. doi: 10.1210/en.140.11.4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Caro JF, Kolaczynski JW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Opentanova I, Goldman WH, et al. Decreased cerebrospinal-fluid/serum leptin ratio in obesity: a possible mechanism for leptin resistance. Lancet. 1996;348:159–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03173-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robinson D, Rock J, Menkin MF. Control of human spermatogenesis by induced changes of intrascrotal temperature. JAMA. 1968;204:290–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1968.03140170006002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shiraishi K, Takihara H, Matsuyama H. Elevated scrotal temperature, but not varicocele grade, reflects testicular oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis. World J Urol. 2010;28:359–64. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0462-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Paul C, Murray AA, Spears N, Saunders PTK. A single, mild, transient scrotal heat stress causes DNA damage, subfertility and impairs formation of blastocysts in mice. Reproduction. 2008;136:73–84. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Paul C, Melton DW, Saunders PTK. Do heat stress and deficits in DNA repair pathways have a negative impact on male fertility? Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14:1–8. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wise LA, Cramer DW, Hornstein MD, Ashby RK, Missmer SA. Physical activity and semen quality among men attending an infertility clinic. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1025–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Southorn T. Great balls of fire and the vicious cycle: a study of the effects of cycling on male fertility. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2002;28:211–3. doi: 10.1783/147118902101196621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mariotti A, Di Carlo L, Orlando G, Corradini ML, Di Donato L, Pompa P, et al. Scrotal thermoregulatory model and assessment of the impairment of scrotal temperature control in varicocele. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:664–73. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shafik A, Olfat S. Lipectomy in the treatment of scrotal lipomatosis. Br J Urol. 1981;53:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1981.tb03129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ivell R. Lifestyle impact and the biology of the human scrotum. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2007;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Setchell BP. The Parkes Lecture. Heat and the testis. J Reprod Fertil. 1998;114:179–94. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1140179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yaeram J, Setchell BP, Maddocks S. Effect of heat stress on the fertility of male mice in vivo and in vitro. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2006;18:647–53. doi: 10.1071/RD05022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Youngson NA, Whitelaw E. The effects of acquired paternal obesity on the next generation. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:195–6. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Daxinger L, Whitelaw E. Understanding transgenerational epigenetic inheritance via the gametes in mammals. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:153–62. doi: 10.1038/nrg3188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Barker DJ. The developmental origins of chronic adult disease. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2004;93:26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Daxinger L, Whitelaw E. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance: more questions than answers. Genome Res. 2010;20:1623–8. doi: 10.1101/gr.106138.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Goto T, Monk M. Regulation of X-chromosome inactivation in development in mice and humans. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:362–78. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.362-378.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ooi SL, Henikoff S. Germline histone dynamics and epigenetics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:257–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Molaro A, Hodges E, Fang F, Song Q, McCombie WR, Hannon GJ, et al. Sperm methylation profiles reveal features of epigenetic inheritance and evolution in primates. Cell. 2011;146:1029–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jenkins T, Carrell DT. Sperm specific chromatin modifications and their impact on the paternal contribution to the embryo. Reproduction. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 107.Marques CJ, João Pinho M, Carvalho F, Bièche I, Barros A, Sousa M. DNA methylation imprinting marks and DNA methyltransferase expression in human spermatogenic cell stages. Epigenetics. 2011;6:1354–61. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.11.17993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tunc O, Tremellen K. Oxidative DNA damage impairs global sperm DNA methylation in infertile men. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26:537–44. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nanassy L, Carrell DT. Analysis of the methylation pattern of six gene promoters in sperm of men with abnormal protamination. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:342–6. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.El Hajj N, Zechner U, Schneider E, Tresch A, Gromoll J, Hahn T, et al. Methylation status of imprinted genes and repetitive elements in sperm DNA from infertile males. Sex Dev. 2011;5:60–9. doi: 10.1159/000323806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Minor A, Chow V, Ma S. Aberrant DNA methylation at imprinted genes in testicular sperm retrieved from men with obstructive azoospermia and undergoing vasectomy reversal. Reproduction. 2011;141:749–57. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oakes CC, Kelly TL, Robaire B, Trasler JM. Adverse effects of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine on spermatogenesis include reduced sperm function and selective inhibition of de novo DNA methylation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:1171–80. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pathak S, Kedia-Mokashi N, Saxena M, D’Souza R, Maitra A, Parte P, et al. Effect of tamoxifen treatment on global and insulin-like growth factor 2-H19 locus-specific DNA methylation in rat spermatozoa and its association with embryo loss. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(Suppl):2253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Barton TS, Robaire B, Hales BF. Epigenetic programming in the preimplantation rat embryo is disrupted by chronic paternal cyclophosphamide exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7865–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501200102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ouko LA, Shantikumar K, Knezovich J, Haycock P, Schnugh DJ, Ramsay M. Effect of alcohol consumption on CpG methylation in the differentially methylated regions of H19 and IG-DMR in male gametes: implications for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1615–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bielawski DM, Zaher FM, Svinarich DM, Abel EL. Paternal alcohol exposure affects sperm cytosine methyltransferase messenger RNA levels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:347–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stouder C, Somm E, Paoloni-Giacobino A. Prenatal exposure to ethanol: a specific effect on the H19 gene in sperm. Reprod Toxicol. 2011;31:507–12. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Knezovich JG, Ramsay M. The effect of preconception paternal alcohol exposure on epigenetic remodeling of the h19 and rasgrf1 imprinting control regions in mouse offspring. Front Genet. 2012;3:10. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Barres R, Zierath JR. DNA methylation in metabolic disorders. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:897S–900. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gaucher J, Reynoird N, Montellier E, Boussouar F, Rousseaux S, Khochbin S. From meiosis to postmeiotic events: the secrets of histone disappearance. FEBS J. 2010;277:599–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Balhorn R, Gledhill BL, Wyrobek AJ. Mouse sperm chromatin proteins: quantitative isolation and partial characterization. Biochemistry. 1977;16:4074–80. doi: 10.1021/bi00637a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gatewood JM, Cook GR, Balhorn R, Bradbury EM, Schmid CW. Sequence-specific packaging of DNA in human sperm chromatin. Science. 1987;236:962–4. doi: 10.1126/science.3576213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Farthing CR, Ficz G, Ng RK, Chan CF, Andrews S, Dean W, et al. Global mapping of DNA methylation in mouse promoters reveals epigenetic reprogramming of pluripotency genes. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Awe S, Renkawitz-Pohl R. Histone H4 acetylation is essential to proceed from a histone- to a protamine-based chromatin structure in spermatid nuclei of Drosophila melanogaster. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2010;56:44–61. doi: 10.3109/19396360903490790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fenic I, Sonnack V, Failing K, Bergmann M, Steger K. In vivo effects of histone-deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin-A on murine spermatogenesis. J Androl. 2004;25:811–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hazzouri M, Pivot-Pajot C, Faure AK, Usson Y, Pelletier R, Sèle B, et al. Regulated hyperacetylation of core histones during mouse spermatogenesis: involvement of histone deacetylases. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:950–60. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Marcon L, Boissonneault G. Transient DNA strand breaks during mouse and human spermiogenesis new insights in stage specificity and link to chromatin remodeling. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:910–8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.022541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Aoki VW, Carrell DT. Human protamines and the developing spermatid: their structure, function, expression and relationship with male infertility. Asian J Androl. 2003;5:315–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Aoki VW, Emery BR, Liu L, Carrell DT. Protamine levels vary between individual sperm cells of infertile human males and correlate with viability and DNA integrity. J Androl. 2006;27:890–8. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Aoki VW, Moskovtsev SI, Willis J, Liu L, Mullen JB, Carrell DT. DNA integrity is compromised in protamine-deficient human sperm. J Androl. 2005;26:741–8. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Grunewald S, Paasch U, Glander HJ, Anderegg U. Mature human spermatozoa do not transcribe novel RNA. Andrologia. 2005;37:69–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2005.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lalancette C, Miller D, Li Y, Krawetz SA. Paternal contributions: new functional insights for spermatozoal RNA. J Cell Biochem. 2008;104:1570–9. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dadoune JP. Spermatozoal RNAs: what about their functions? Microsc Res Tech. 2009;72:536–51. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ostermeier GC, Miller D, Huntriss JD, Diamond MP, Krawetz SA. Reproductive biology: delivering spermatozoan RNA to the oocyte. Nature. 2004;429:154. doi: 10.1038/429154a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lalancette C, Platts AE, Johnson GD, Emery BR, Carrell DT, Krawetz SA. Identification of human sperm transcripts as candidate markers of male fertility. J Mol Med (Berl) 2009;87:735–48. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Sone Y, Ito M, Shirakawa H, Shikano T, Takeuchi H, Kinoshita K, et al. Nuclear translocation of phospholipase C-zeta, an egg-activating factor, during early embryonic development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:690–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Krawetz SA, Kruger A, Lalancette C, Tagett R, Anton E, Draghici S, et al. A survey of small RNAs in human sperm. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:3401–12. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Costa FF. Non-coding RNAs: new players in eukaryotic biology. Gene. 2005;357:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sinkkonen L, Hugenschmidt T, Berninger P, Gaidatzis D, Mohn F, Artus-Revel CG, et al. MicroRNAs control de novo DNA methylation through regulation of transcriptional repressors in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:259–67. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Filkowski JN, Ilnytskyy Y, Tamminga J, Koturbash I, Golubov A, Bagnyukova T, et al. Hypomethylation and genome instability in the germline of exposed parents and their progeny is associated with altered miRNA expression. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1110–5. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Rassoulzadegan M, Grandjean V, Gounon P, Vincent S, Gillot I, Cuzin F. RNA-mediated non-mendelian inheritance of an epigenetic change in the mouse. Nature. 2006;441:469–74. doi: 10.1038/nature04674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Lane M, Owens JA, Ohlsson Teague EMC, Palmer NO, Bakos HW, Fullston T. You are what your father ate – paternal programming of reproductive and metabolic health in offspring. Biol Reprod. 2012 In press. [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ibrahim HA, Zhu Y, Wu C, Lu C, Ezekwe MO, Liao SF, et al. Selenium-Enriched Probiotics Improves Murine Male Fertility Compromised by High Fat Diet. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2012;147:251–60. doi: 10.1007/s12011-011-9308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Håkonsen LB, Thulstrup AM, Aggerholm AS, Olsen J, Bonde JP, Andersen CY, et al. Does weight loss improve semen quality and reproductive hormones? Results from a cohort of severely obese men. Reprod Health. 2011;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Sermondade N, Massin N, Boitrelle F, Pfeffer J, Eustache F, Sifer C, et al. Sperm parameters and male fertility after bariatric surgery: three case series. Reprod Biomed Online. 2012;24:206–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Strain GW, Zumoff B, Kream J, Strain JJ, Deucher R, Rosenfeld RS, et al. Mild Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in obese men. Metabolism. 1982;31:871–5. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Magnusdottir EV, Thorsteinsson T, Thorsteinsdottir S, Heimisdottir M, Olafsdottir K. Persistent organochlorines, sedentary occupation, obesity and human male subfertility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:208–15. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Fejes I, Koloszár S, Szöllosi J, Závaczki Z, Pál A. Is semen quality affected by male body fat distribution? Andrologia. 2005;37:155–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2005.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Koloszár S, Fejes I, Závaczki Z, Daru J, Szöllosi J, Pál A. Effect of body weight on sperm concentration in normozoospermic males. Arch Androl. 2005;51:299–304. doi: 10.1080/01485010590919701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Qin DD, Yuan W, Zhou WJ, Cui YQ, Wu JQ, Gao ES. Do reproductive hormones explain the association between body mass index and semen quality? Asian J Androl. 2007;9:827–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2007.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Hammoud AO, Wilde N, Gibson M, Parks A, Carrell DT, Meikle AW. Male obesity and alteration in sperm parameters. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:2222–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Nicopoulou SC, Alexiou M, Michalakis K, Ilias I, Venaki E, Koukkou E, et al. Body mass index vis-à-vis total sperm count in attendees of a single andrology clinic. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1016–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Hofny ER, Ali ME, Abdel-Hafez HZ, El-Dien Kamal E, Mohamed EE, Abd El-Azeem HG, et al. Semen parameters and hormonal profile in obese fertile and infertile males. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:581–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Stewart TM, Liu DY, Garrett C, Jørgensen N, Brown EH, Baker HW. Associations between andrological measures, hormones and semen quality in fertile Australian men: inverse relationship between obesity and sperm output. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1561–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Chavarro JE, Toth TL, Wright DL, Meeker JD, Hauser R. Body mass index in relation to semen quality, sperm DNA integrity, and serum reproductive hormone levels among men attending an infertility clinic. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Shayeb AG, Harrild K, Mathers E, Bhattacharya S. An exploration of the association between male body mass index and semen quality. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23:717–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Sekhavat L, Moein MR. The effect of male body mass index on sperm parameters. Aging Male. 2010;13:155–8. doi: 10.3109/13685530903536643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Rybar R, Kopecka V, Prinosilova P, Markova P, Rubes J. Male obesity and age in relationship to semen parameters and sperm chromatin integrity. Andrologia. 2011;43:286–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2010.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]