Abstract

How do drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, cause stable changes in neural plasticity that in turn drive long-term changes in behavior? What kind of mechanism can underlie such stable changes in neural plasticity? One prime candidate mechanism is epigenetic mechanisms of chromatin regulation. Chromatin regulation has been shown to generate short-term and long-term molecular memory within an individual cell. They have also been shown to underlie cell fate decisions (or cellular memory). Now, there is accumulating evidence that in the CNS, these same mechanisms may be pivotal for drug-induced changes in gene expression and ultimately long-term behavioral changes. As these mechanisms are also being found to be fundamental for learning and memory, an exciting new possibility is the extinction of drug-seeking behavior by manipulation of epigenetic mechanisms. In this review, we critically discuss the evidence demonstrating a key role for chromatin regulation via histone acetylation in cocaine action.

Keywords: epigenetics, acetylation, HDAC, HAT, CBP, cocaine

INTRODUCTION

Substance abuse disorders are characterized by compulsive drug seeking and drug use despite the associated negative consequences that can be quite severe. Addiction is a chronic condition such that even after extended periods of abstinence, addicted individuals have a high rate of relapse (Koob and Le Moal, 2005). Drugs of abuse are known to affect neuronal structure and function in specific brain regions, resulting in stable and persistent changes from the cellular level to the behavioral level (Nestler, 2001). A key question is what mechanisms are involved in initiating and establishing these stable changes at the cellular level that manifest in long-term behavioral changes?

A prime candidate for such a mechanism involves epigenetic mechanisms of chromatin regulation. Chromatin regulation may provide transient and potentially stable epigenetic marks in the service of activating and/or maintaining transcriptional processes. These in turn may ultimately participate in the molecular mechanisms required for neuronal changes subserving long-lasting changes in behavior. As an epigenetic mechanism of transcriptional control, chromatin modification has been shown to participate in maintaining cellular memory (eg, cell fate) and may underlie the strengthening and maintenance of synaptic connections required for long-term changes in behavior (Maze and Nestler, 2011).

Chromatin modification refers to the post-translational modification of histones including, but not limited to, acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation (see other reviews, in this special issue of NPP reviews). In neuroscience, the best-studied enzymes involved in chromatin modification thus far are the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), which in general facilitate gene expression and repress gene expression (Kouzarides, 2007). A prevailing idea is that gene expression is necessary for stable cellular changes manifesting in stable changes in behavior. Thus, one hypothesis is that epigenetic mechanisms, known to be involved in establishing long-lasting cellular changes, regulate gene expression required for stable changes in cell function, and ultimately stable changes in behavior.

This review focuses on mechanisms of cocaine action, and in particular the role of histone acetylation in regulating cocaine-induced changes in neural plasticity and behavior. That is not to suggest that other drugs of abuse or other mechanisms of chromatin modification are not as important, but with regard to drugs of abuse and epigenetic mechanisms, there is simply more known about cocaine and histone acetylation allowing us to hopefully draw better overall conclusions and perhaps determine fundamental aspects of how substance abuse disorders arise and persist.

The review has four main sections. The first section discusses the evidence demonstrating that cocaine affects histone acetylation (Section I). This is followed by a discussion of the individual HDACs (Section II) and HATs (Section III) that are involved in regulating histone acetylation changes induced by cocaine. Finally, we draw from the learning and memory field to discuss the extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior (Section IV). But first, how does cocaine affect neuronal function?

Cocaine mechanism of action

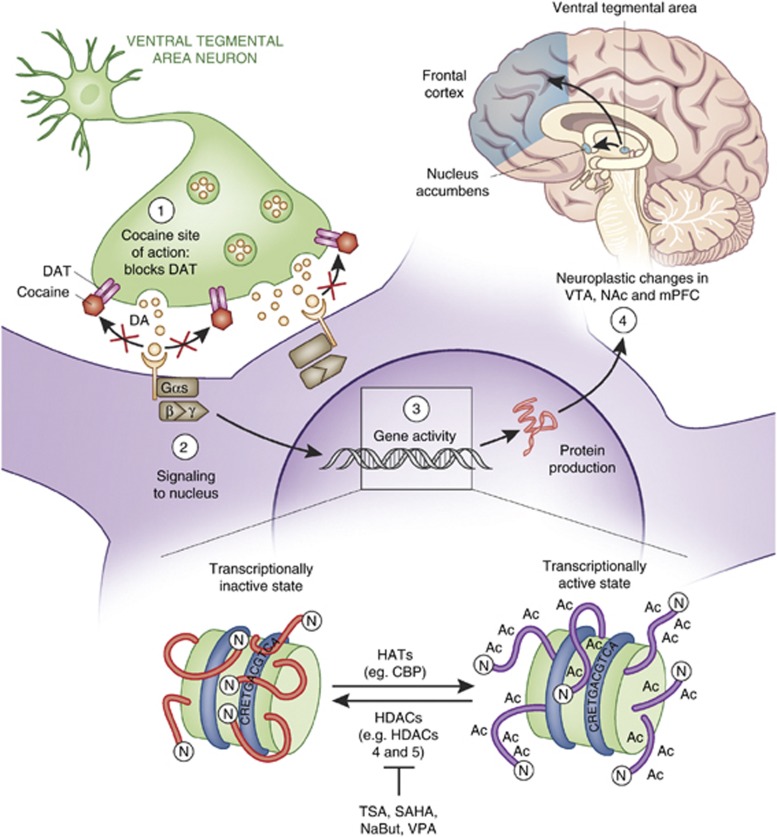

One of the cocaine′s primary molecular actions is to block presynaptic dopamine (DA) reuptake transporters (DAT) (Ritz et al, 1987, 1988; Kuhar et al, 1988) (see Figure 1). Although cocaine has an affinity for presynaptic norepinephrine- and serotonin-reuptake transporters as well, it is believed that the reinforcing and rewarding properties of cocaine are caused partly by indirect elevation of DA along the VTA-originating mesocorticolimbic DA pathway (brain reward pathway). That is not to say that SERT and NET are not involved in cocaine action. In fact, many groups have examined the effects of knocking out SERT and NET on behavioral responses to cocaine, such as self-administration (Hall et al, 2004). An important frontier for addiction neurobiology is to determine the precise, differential and/or overlapping roles DAT, SERT and NET play in the development of cocaine addiction. Since a large body of literature has examined the molecular/behavioral consequences of cocaine binding to DAT, though, this review focuses on the effects of cocaine on dopaminergic neurotransmission in the reward pathway.

Figure 1.

Cocaine causes transcription-dependent neuroplasticity in the reward pathway. (Brain top right): Cocaine alters the dynamics of numerou neurotransmitter systems in the mesocorticolimbic ‘reward pathway' of the brain, which includes the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens (NAc), and prefrontal cortex (PFC). These brain regions are critical for reward, reinforcement, and higher cognitive functions. (Main panel): Cocaine indirectly enhances the levels of the neurotransmitter DA at the interface between VTA cells and NAc cells by binding to and blocking DAT (top left). The subsequent activation of D1- and D2-like DA receptors stimulates intracellular signaling cascades that direct TF binding to DNA, facilitating neuroplasticity in response to cocaine intake. (DNA inset): Nucleosomes are in equilibrium between transcriptionally inactive and active states. HATs and HDACs have opposing actions to push the equilibrium one way or the other. Histone acetylation (by HATs) generally allows for TF binding and gene expression while histone deacetylation (by HDACs) represses transcription. Adapted from Nestler (2005) and McQuown and Wood (2010).

DA-producing neurons of the reward pathway originate in the VTA and release DA in the NAc, medial prefrontal cortex and limbic areas like the thalamus and amygdala. DAT in the NAc region bridging NAc and VTA neurons appears to be the primary target mediating cocaine′s rewarding and reinforcing effects (see Nestler, 2004 for review). For a review of reward pathway anatomy and physiology please see Koob and Volkow (2010). Blockade of DAT, though, like general increases in VTA to NAc DA neurotransmission, cannot fully explain the complex behavior of drug addiction. It is hypothesized that in response to chronic cocaine intake, transcription-dependent neuroplasticity in many brain regions composing the reward pathway results in cocaine-induced behavioral responses and the development of addiction (for review see Robison and Nestler, 2011). These brain regions are interconnected by DA neurotransmission. The entire reward pathway is thus reactive to increases in midbrain DA levels caused by cocaine. As a result, the intracellular signaling cascades that regulate transcription in these other reward pathway brain regions are engaged, leading to a chain of events including changes in chromatin structure, altered gene expression, neural plasticity changes, and ultimately short- and long-term effects on behavior.

A main idea in the field of epigenetics is that the epigenome serves as a signal integration platform in which activity- and experience-dependent signaling modifies epigenetic marks and the pattern of those marks changes chromatin structure, perhaps resulting in a ‘histone code' (Strahl and Allis, 2000), and leads to transcription-dependent long-term changes in neural plasticity. Thus, the signaling cascades engaged by cocaine are key to understanding the downstream effects on the chromatin regulation machinery. One key signaling cascade that is engaged by Ca2+ and D1-like DA receptors is the cAMP signaling pathway, resulting in the activation of MAP kinases in the ERK-MSK1 pathway and PKA, which can activate the phosphatases DARPP-32/PP1 as well as directly activate the transcription factor (TF) CREB via serine 133 phosphorylation. Phospho-S133 on CREB recruits CREB-binding protein (CBP), which is discussed later in this review. Cocaine also increases intracellular calcium levels activating CaM kinases and the phosphatase Calcineurin. Ultimately, all of these kinases, acetylases, etc. impact the epigenomic landscape, resulting in carefully orchestrated transcriptional regulation via chromatin regulation. For a recent review of intracellular signaling pathways affected by cocaine that are related to the regulation of chromatin modifying enzymes, see Renthal and Nestler (2009a). The key problem to understand is how the short-term effects of cocaine on signaling cascades ultimately results in long-lasting changes in neural plasticity and behavior.

SECTION I. THE ROLE OF HISTONE ACETYLATION IN MEDIATING COCAINE-INDUCED GENE EXPRESSION

The overall premise of this review is that cocaine induces stable changes in neural plasticity and behavior in a transcription-dependent manner. It is well established that stable cellular changes require transcription that is regulated by histone acetylation and other epigenetic mechanisms (eg, cellular memory, Turner (2002)). Thus, we begin this review by discussing the evidence demonstrating that cocaine regulates gene expression via histone acetylation. Numerous important questions arise from this line of investigation including: (1) What are the genes being regulated by cocaine-induced histone acetylation? (2) What are the specific sites and patterns of histone acetylation induced by cocaine at the promoters of these genes? (3) How does acute vs chronic cocaine administration differentially affect histone acetylation? (4) Are there brain region specific differences? (5) How does transient histone acetylation contribute to stable changes in neuronal plasticity? These are all important basic questions that the field has begun to address, revealing fundamental aspects of cocaine action.

One important issue is that histone acetylation by itself is not known to be a persistent histone modification. Thus, the overly simplistic idea that stable histone acetylation patterns regulate maintained changes in gene expression that underlie persistent changes in neural plasticity is very unlikely. However, as we will discuss in later sections of this review, transient changes in histone acetylation temporal dynamics can have significant effects on gene expression, which correlate with dramatic effects on long-term memory, and even cocaine-induced memory formation and extinction.

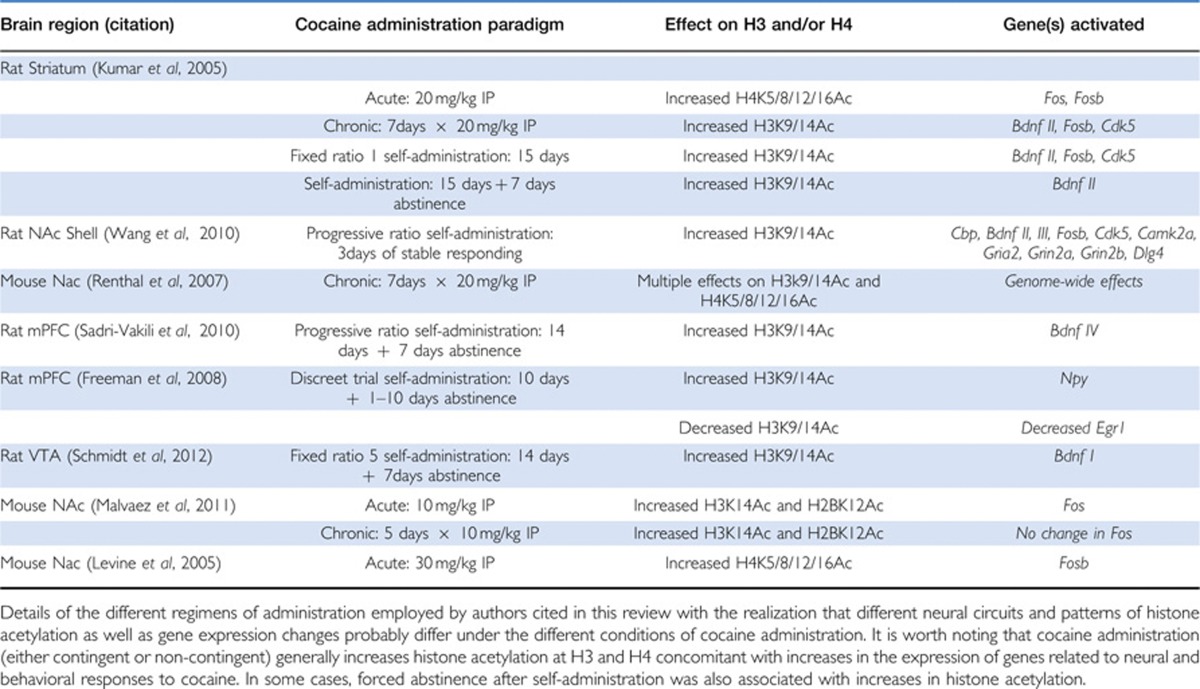

Cocaine-induced acetylation occurs at the promoters of genes regulated by cocaine

Two of the best-studied sites of acetylation are acetylated H3K9/14 and H4K5/8/12/16, which are markers of transcriptional activation (Kouzarides, 2007). Throughout this review, we will discuss the effects of different cocaine administration paradigms on histone acetylation and gene expression in three main reward pathway brain regions; the VTA, NAc, and mPFC. It is important to realize that animals exhibit distinct physiological and neural responses to different administration regimens (eg, acute vs repeated intraperitoneal injections; chronic self-administration vs chronic self-administration followed by withdrawal). In order to simplify the text, not every experimental detail has been included. However, Table 1 lists the cocaine administration details, chromatin modifications, and gene expression changes reported by the authors cited in this work.

Table 1. Cocaine Administration Paradigms Associated with Changes in Histone Acetylation and Gene Expression in the Brain Reward Pathway.

An important, early finding in the field was that cocaine exposure does not cause a global, genome-wide increase in histone acetylation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays reveal that in the rat striatum, the levels of H3K9/14Ac or H4K5/8/12/16Ac in the promoters of β-tubulin, tyrosine hydroxylase, and core histone 4 are unaffected by acute or chronic cocaine administration (Kumar et al, 2005). These three genes are not transcriptionally activated by cocaine, thus the lack of cocaine-induced promoter acetylation correlates with a lack of expression after cocaine (Mcclung and Nestler, 2003; Yuferov et al, 2003; Kumar et al, 2005).

In contrast, histone modifications occur at the promoters of genes that are transcriptionally regulated by cocaine. These genes are directly implicated in cocaine-induced neuroplasticity predicted to underlie addiction-like behaviors (Kumar et al, 2005). For example, cocaine enhances striatal levels of H3K9/14Ac or H4K5/8/12/16Ac in the promoters of Fos, Fosb, Bdnf II, and Cdk5, genes known to be transcriptionally regulated by cocaine (Kumar et al, 2005). H3K9/14Ac and H4K5/8/12/16Ac are markers of transcriptional activation (Kouzarides, 2007), thus implicating histone acetylation in cocaine-mediated regulation of these genes. Transcription of these genes is considered a key component of cocaine-induced neuroplasticity potentially underlying long-term changes in behavior (McClung and Nestler, 2003; Kumar et al, 2005). Thus, at least for this set of genes, cocaine appears to regulate their transcription via histone acetylation. Moreover, these genes are proposed to be pivotal for behavioral responses to cocaine, suggesting that histone modification is one mechanism by which cocaine causes neural and behavioral plasticity changes in the striatum.

Recently, ChIP coupled with promoter microarray analysis (ChIP-chip) has provided further insight into which genes cocaine regulates in the striatum via H3 and H4 acetylation (Renthal et al, 2009). Protein–DNA complexes from the NAc of mice that were administered cocaine for 7 days and sacrificed 24 h after the last injection were subjected to ChIP assays using antibodies specific for H3K9/14Ac and H4K5/8/12/16Ac. The isolated DNA was hybridized to promoter microarrays that recognize the promoters of ∼20,000 genes (Renthal et al, 2009). In agreement with previous microarray studies examining the effects of cocaine on gene expression in the NAc (McClung and Nestler, 2003; Renthal et al, 2007; LaPlant and Nestler, 2011), cocaine's predominant effect is to activate gene transcription (Renthal et al, 2009). That is, many more genes exhibit increased levels of H3K9/14Ac and H4K5/8/12/16Ac after cocaine treatment (1696 genes) than reduced levels of acetylation (206 genes) at those sites considered markers of transcriptional activation (Renthal et al, 2009). Although increases in promoter acetylation do not always correlate with enhanced transcription, the Supplementary Table provided by Renthal et al (2009) shows a clear correlation between levels of promoter acetylation and mRNA expression in the NAc. Thus, similar to the focused ChIP results reported by Kumar et al (2005), these genome-wide approaches also suggest that cocaine affects gene expression via histone acetylation, suggesting that the enzymes carrying out histone acetylation (HATs and HDACs) are pivotal for cocaine-dependent effects.

An important future direction is to determine the temporal dynamics of histone acetylation pattern changes. For example, it is clear that cocaine results in increased histone acetylation of specific sites, but is acetylation at those sites (and others) maintained beyond the normal time they might be acetylated after natural rewards? This is an important question because maintained histone acetylation by cocaine could have dramatic effects on gene expression, even if they are considered temporary by experimental standards. In the learning and memory field, maintained gene expression by hyper-histone acetylation induced by HDAC inhibition causes two key immediate early genes, Nr4a1 and Nr4a2, to have maintained gene expression beyond the time they would normally be expressed after a learning event (Vecsey et al, 2007). The maintained gene expression correlated with maintained acetylation at H3K9/14 and H4K5/8/12/16. Nr4a2 is absolutely necessary for HDAC3-dependent inhibition to enhance long-term memory (McQuown et al, 2011). Thus, a better understanding of the temporal dynamics of histone acetylation changes and subsequent gene expression profile dynamics could begin to elucidate how long-term changes in neural plasticity are established by rather transient changes in histone acetylation and gene expression.

Cocaine-mediated acetylation is selective for H3 or H4, but rarely both

This section examines the phenomenon of selectivity for H3 or H4 in cocaine-induced histone acetylation. In the Renthal et al (2009) microarray study, chronic cocaine-treated mice exhibited greater levels of both H3K9/14Ac (at the promoters of 1004 genes) and H4K5/8/12/16Ac (at the promoters of 692 genes), compared with saline-treated controls. Only about 15% of the genes analyzed, though, exhibit increased acetylation at both H3 and H4 in the same region of the promoter. Conversely, only 1% of the genes have reduced acetylation at both H3 and H4 (Renthal et al, 2009). These data suggest that cocaine-regulated gene promoters are either acetylated at H3 or H4, but rarely both. That result supports the idea that cocaine-mediated regulation of histone acetylation occurs via distinct intracellular signaling pathways that result in either H3K9/14Ac or H4K5/8/12/16Ac. A major goal of the field is to now identify the signaling pathways and specific enzymes (such as HATs and HDACs) involved in the specific acetylation of either H3 or H4. These signaling pathways may recruit specific histone modifying enzymes to the promoters of genes transcriptionally regulated by cocaine that mediate selective, cocaine-induced H3K9/14 or H4K5/8/12/16 acetylation.

When Kumar et al (2005) examined H3K9/14Ac and H4K5/8/12/16Ac in the promoters of the Fos, Fosb, Bdnf II, and Cdk5 genes in the rat striatum, they observed that cocaine affected acetylation at H3 or H4, but not both. Specifically, acute cocaine administration increases H4K5/8/12/16Ac, but not H3K9/14Ac, at the Fos and Fosb promoters with no effect on acetylation of Bdnf II or Cdk5 promoters (Kumar et al, 2005). These changes in acetylation correlate with acute cocaine-induced transcription of Fos and Fosb, but not Bdnf II or Cdk5 (Kumar et al, 2005).

After a chronic regimen, however, cocaine no longer increases acetylation of the Fos promoter (Kumar et al, 2005), consistent with a desensitization of that gene's transcriptional potential after repeated cocaine administration (Hope et al, 1992; Daunais et al, 1993). Chronic cocaine does, however, stimulate transcription of Fosb, Bdnf, and Cdk5 (Bibb et al, 2001; Grimm et al, 2003; McClung and Nestler, 2003) and those gene promoters exhibit chronic cocaine-induced elevations of H3K9/14Ac, but not H4K5/8/12/16Ac (Kumar et al, 2005). Some inconsistencies in the literature, however, should be noted. Maze et al, (2010) observed upregulation of Fos in the striatum after repeated IP injections of cocaine. Although no increases in striatal Fos expression were observed after repeated cocaine injections by Malvaez et al (2011), they did report enhanced levels of H3K14Ac at the Fos promoter. Furthermore, Liu et al (2006) reported desensitization of Bdnf IV in the striatum after chronic cocaine administration. These inconsistencies may reflect differences in drug administration paradigms and times of sacrifice.

In any case, these data do show a difference in the effects of acute vs chronic cocaine administration on promoter acetylation. That is an important finding because gene expression patterns of neurons in the NAc change during the course of chronic administration (McClung and Nestler, 2003). The genes expressed above the levels observed in saline controls after 1 dose (eg, Fos) are no longer expressed after repeated dosing, while other genes (eg, Bdnf II) are only over expressed above control injected subjects by chronic treatment. It is hypothesized that those changes in gene expression patterns are critical for the transition from recreational cocaine use to compulsive drug use (White and Kalivas, 1998; Nestler, 2001). Thus, at least for a subset of cocaine-regulated genes in the striatum, promoter acetylation patterns depend on the paradigm of cocaine administration. And the administration paradigm (acute vs chronic) affects the patterns of genes expressed via chromatin modifying mechanisms, which may be a mechanism of neuroplasticity underlying distinct behavioral responses to acute vs chronic injections.

The effect of chronic cocaine enhancement of H3K9/14Ac at the promoters of Fosb, Bdnf II, and Cdk5 also occurs with cocaine self-administration (Kumar et al, 2005). In that study, cocaine self-administration enhances H3K9/14Ac levels at the Fosb, Bdnf II, and Cdk5 promoters in the striatum to an even greater degree than repeated injections, with no effect on H4K5/8/12/16Ac levels (Kumar et al, 2005). Surprisingly, H3K9/14Ac levels at the Bdnf II promoter continue to elevate 1 week after abstinence from cocaine self-administration (14-fold above controls compared with threefold greater H3K9/14Ac 24 h after the last self-administration session). That increase in H3K9/14Ac levels during the withdrawal period correlates with increases in striatal BDNF protein levels as a function of withdrawal time (Grimm et al, 2003). The latter result suggests that cocaine-induced enhancement of H3K9/14Ac at the Bdnf II promoter is a relatively long-lasting modification that is initiated by chronic cocaine intake. Furthermore, the sustained increase in H3K9/14Ac levels during forced abstinence, concomitant with increases in BDNF protein, implicates HATs and/or HDACs in mechanisms of Bdnf II regulation during withdrawal (Kumar et al, 2005).

In a separate study, rats self-administering cocaine exhibit selective enhancement of H3K9/14Ac at a subset of promoters, including the Bdnf II and III promoters, analyzed in the NAc (Wang et al, 2010). In the NAc shell of rats that had acquired a stable break point, ChIP assays reveal increased levels of H3K9/14Ac at the promoters of Cbp, Bdnf II and III, Fosb, Cdk5, Camk2a, Gria2, Grin2a, Grin2b, and Dlg4. All of these genes are implicated in the neurobiology of cocaine action (Wang et al, 2010). Chronic cocaine-induced increases in H4K5/8/12/16Ac were only observed at two promoters, Egr1 and Psd95 (Wang et al, 2010).

The profile of chronic cocaine-induced increases in acetylation was similar for those same genes in the NAc core, though to a lesser degree, even though global levels were unchanged (Wang et al, 2010). This finding highlights the need to perform promoter-specific ChIP assays with antibodies specific for acetylated lysines because global levels of acetylation are obviously not representative of chromatin modifications occurring at individual gene promoters. No increases in chronic cocaine-induced histone acetylation are observed for the above genes in the mPFC. These results suggest that in the NAc shell and core, chronic cocaine-induced changes in gene expression are regulated, in part, by H3K9/14Ac acetylation. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that cocaine-induced acetylation of H3K9/14 in the NAc shell may be a transcriptional regulatory mechanism that regulates gene expression changes that underlie motivation to self-administer cocaine (Wang et al, 2010). What about other brain regions?

Cocaine-induced acetylation of H3 and H4 in the mPFC and VTA

Chromatin modifications that facilitate cocaine-induced gene transcription via increases in histone acetylation at the promoters of specific genes involved in neuroplastic and behavioral responses to cocaine are not confined to the striatum. Although Wang et al (2010) did not observe changes in the global levels of HK9/14Ac or H4K5/8/12/16Ac during self-administration, ChIP assays revealed that cocaine-induced histone acetylation does regulate genes in the mPFC critically involved in cocaine-induced neuroplasticity and drug-seeking behaviors. In the mPFC, 14 days of cocaine self-administration followed by 7 days of forced abstinence increases BDNF protein levels and the amount of H3K9/14Ac at the Bdnf IV promoter (Sadri-Vakili et al, 2010). That increase in H3K9/14Ac is associated with increased P-CREB and decreased MeCP2 binding to the Bdnf IV promoter, as determined by ChIP (Sadri-Vakili et al, 2010). These data indicate that increases in mPFC BDNF IV induced by cocaine self-administration and forced abstinence, is associated with cocaine-induced elevations of H3K9/14Ac at the Bdnf IV promoter. These data also lend insight into how brain region-specific histone acetylation may have a role in behavioral responses to cocaine because intra-mPFC infusions of BDNF attenuate reinstatement of cue-induced cocaine self-administration (Berglind et al, 2007, 2009; McGinty et al, 2010).

Other genes in the mPFC implicated in behavioral responses to cocaine are also regulated by cocaine-induced histone acetylation during abstinence. Self-administration and forced abstinence for 1 day increases the transcription of neuropeptide Y (Npy) mRNA in the mPFC that is correlated with increased H3K9/14Ac levels at the Npy promoter (Freeman et al, 2008). Inversely, the mRNA of Egr1, an immediate early gene examined by Freeman et al (2008), was significantly downregulated after 1 and 10 days of abstinence and that downregulation was associated with decreased H3K9/14Ac at the Egr1 promoter (Freeman et al, 2008). These results again illustrate how histone acetylation can be a relatively long-lasting post-translational modification that correlates with relatively long-lasting gene expression. However, further investigation is needed to more accurately understand the mechanistic relationship between long-lasting histone modifications and maintained gene expression.

A separate study found that in the VTA, cocaine self-administration for 14 days followed by 7 days of forced abstinence increases BDNF exon I-containing transcripts accompanied by increased levels of H3K9/14Ac at the Bdnf promoter and CBP binding to the Bdnf promoter (Schmidt et al, 2012). Together, these studies of histone acetylation of cocaine-inducible genes in the mPFC and VTA suggest that histone acetylation plays an important role in regulating transcription during forced abstinence after cocaine self-administration in regions of the reward pathway besides the NAc that are involved in neural and behavioral responses to chronic cocaine intake (Sadri-Vakili et al, 2010; Maze and Nestler, 2011).

Mechanistic insight: cocaine increases the magnitude, not distribution, of promoter acetylation

Cocaine-mediated increases in promoter acetylation may have mechanistically different effects on transcription depending on the distribution of those acetyl groups (Renthal et al, 2009). If acetylation is increased at a region acetylated under basal conditions, containing DNA cis-regulatory elements that bind TFs, then the result could be enhanced TF binding and subsequent enhanced transcription, or in some cases repression. If, however, the increased acetylation occurs by distributing additional acetyl groups across the breadth of the promoter, in regions not normally acetylated, that could mean cocaine activates transcription by opening the chromatin for binding of proteins that don't usually have access to those regions. In that case, novel DNA–protein interactions directed by novel distribution of acetyl groups would drive cocaine-induced transcriptional responses. Renthal et al (2009) address this important concept by showing that repeated cocaine injections cause magnitude differences in acetylation at critical regulatory regions of cocaine-activated genes. There was no change in overall distribution of acetylation after cocaine treatment compared with saline treatment (Renthal et al, 2009). Furthermore, the magnitude increase in acetylation mediated by cocaine is associated with greater cocaine-induced DeltaFOSB and P-CREB binding to the acetylated regions of those promoters (Renthal et al, 2009). Thus, one mechanism by which cocaine-induced acetylation increases transcription may be by facilitating a more permissive state of chromatin to allow for greater TF binding (as stated in Renthal et al, 2009), not by opening previously inaccessible regions of DNA to novel protein–DNA interactions.

The studies discussed thus far begin to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in in vivo regulation of specific, cocaine-regulated genes in the mesocorticolimbic pathway and directly implicates the families of enzymes that affect histone acetylation in cocaine-induced neural and behavioral plasticity (Kumar et al, 2005). The next sections discuss the specific HDACs (Section II) and HATs (Section III) currently known to be involved.

SECTION II. THE ROLE OF HDACS IN MEDIATING COCAINE-INDUCED GENE EXPRESSION

In this section we address the question: What is the role of specific HDAC enzymes in regulating histone acetylation associated with cocaine-induced gene expression? It is important to identify the exact HDAC family member(s) involved in cocaine regulation of histone acetylation in order to understand the complicated mechanisms by which cocaine causes long-lasting neuroplastic changes associated with drug-seeking behavior. First, the evidence of cocaine-induced patterns of histone acetylation (Section I) suggests that specific HATs and/or HDACs may be involved in changes in gene transcription underlying cocaine-induced neuroplasticity. This section focuses on the HDAC family of enzymes, comprised of class I (HDAC1, 2, 3, and 8), class IIa (HDAC4, 5, 7, and 9), class IIb (HDAC6 and 10), class III (the Sirtuins), and class IV (HDAC 11) proteins (Verdin et al, 2003). Section III describes recent findings about HAT activity associated with cocaine-induced neural and behavioral plasticity.

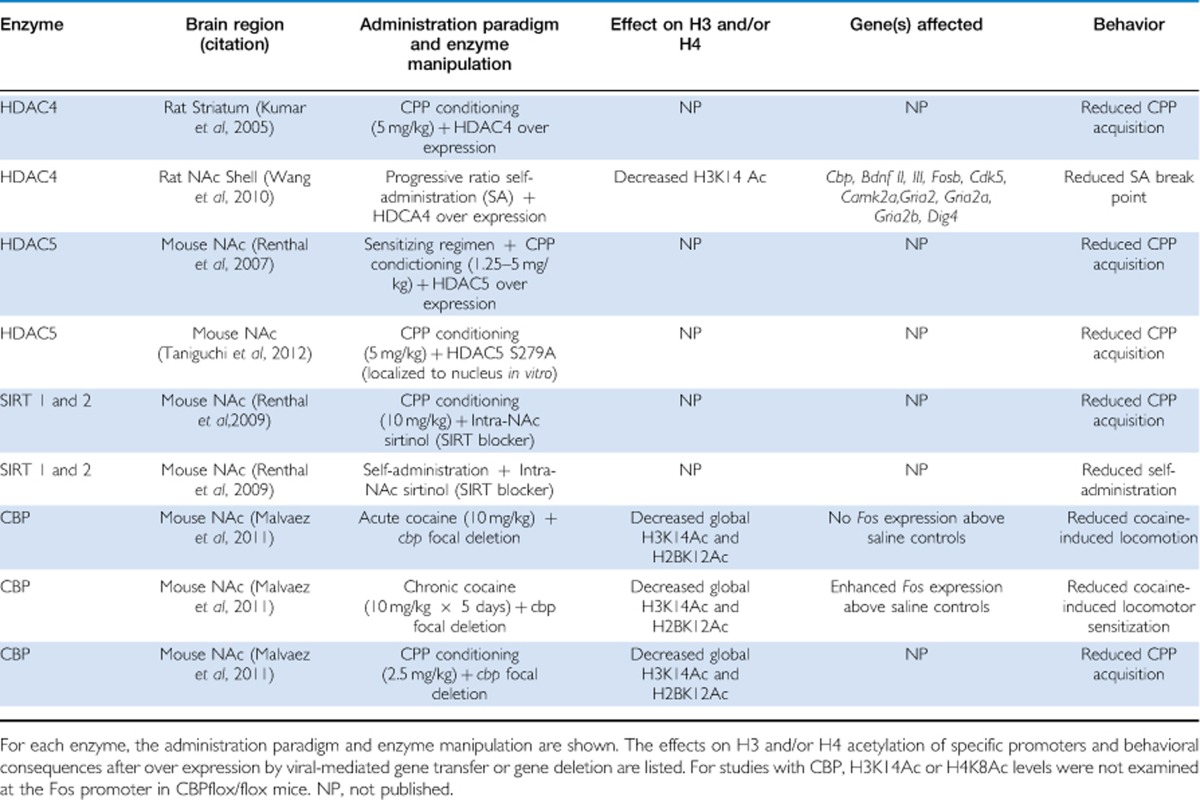

Studies utilizing genetic, viral, and pharmacological approaches to modulate HDAC activity have identified specific HDACs in the NAc that are potentially key to neuronal and behavioral adaptations to cocaine. Namely: HDAC4 (Kumar et al, 2005; Wang et al, 2010); HDAC5 (Renthal et al, 2007; Dietrich et al, 2012; Taniguchi et al, 2012); HDAC1 (Renthal et al, 2008, 2009); HDAC2 (Chandrasekar and Dreyer, 2010; Host et al, 2012); and sirtuins 1 & 2 (Renthal et al, 2009; see Table 2). We will first focus on the evidence from studies using HDAC inhibitors that show HDACs regulate neural and behavioral responses to cocaine. Then, we discuss the role of specific HDACs manipulated by either viral over expression or genetic modification in mice.

Table 2. HDACs and the HAT CBP Mediate Neural and Behavioral Responses to Cocaine.

Most HDAC inhibitors selectively inhibit class I HDACs

It has been known for years that HDAC inhibitors modulate transcriptional and behavioral responses to cocaine (for reviews of this literature, see McQuown and Wood, 2010 and LaPlant and Nestler, 2011). For example, systemic administration of sodium butyrate (NaBut) enhances cocaine-induced histone acetylation in the striatum, c-Fos mRNA expression, locomotor sensitization and cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (CPP) above and beyond the effects of cocaine alone (Kumar et al, 2005; Hui et al, 2010). No effects are observed when sodium butyrate is administered alone or in combination with caffeine, indicating that the effects of HDAC inhibition may not generalize to all stimulants (Kumar et al, 2005). The key, open question is what family members are targeted by HDAC inhibitors?

The inhibitors sodium butyrate (NaBut), valproate, and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) were previously thought to non-specifically block class I, IIa, and IIb, but not class III, HDACs. However, a recent biochemical analysis of the in vitro activities of recombinantly expressed and individually purified HDACs 1–9 demonstrated that those drugs are potent inhibitors of class I, but not class IIa and IIb, HDACs (Kilgore et al, 2010). These findings suggest that it is the class I HDACs that are critical for regulating neural and behavioral responses to cocaine.

The story is more complex than that, though, because there is mounting evidence that class I HDACs interact with class IIa HDACs in vivo as components of multi-protein, transcriptional repressor complexes (for review, see Karagianni and Wong, 2007). In fact, HDAC3, which has potent deacetylase activity (Lahm et al, 2007), is the critical class I HDAC that associates with HDAC4 in vitro via interactions with the co-repressor NCoR to form a functional, multi-protein repressor complex (Guenther et al, 2001; Fischle et al, 2002; Alenghat et al, 2008). HDAC5–HDAC3 interactions in vitro are also necessary to repress gene expression (Grozinger and Schreiber, 2000). These multi-protein interactions may be required because in vitro, HDACs 4, and potentially other class IIa HDACs including HDAC5, have little to no catalytic activity on canonical acetyl lysine substrates (Lahm et al, 2007). Thus, class IIa HDACs may not have potent enzymatic activity, or the substrates used in Lahm et al (2007) are not sufficient to test the activity of class IIa HDACs. In any case, the notion that only class I HDACs are targeted by most HDAC inhibitors must also consider the effects of class I HDAC inhibition on functional associations with different HDACs, like class IIa HDACs 4 and 5.

Class IIa HDACs are involved in cocaine action and histone acetylation

Although HDAC inhibitors like NaBut do not inhibit the class IIa HDACs, HDACs 4 and 5 (Kilgore et al, 2010), and those enzymes may have little to no catalytic activity on canonical acetyl lysine substrates in vitro (Lahm et al, 2007), experimental evidence strongly suggests that these enzymes still play a critical role in mediating cocaine action and histone acetylation, possibly by stabilizing transcriptional repressor complexes or directing their appropriate subcellular localization. This subsection discusses the abundant data regarding the role of HDAC4 and HDAC5 in cocaine-induced neural plasticity and behavior.

HDAC 4

Striatal HDAC 4 is directly implicated in repressing gene transcription required for cocaine-mediated neuroadaptations (Kumar et al, 2005; Korutla et al, 2005; Wang et al, 2010). Mice infused intra-NAc with viral vectors over expressing HDAC4, but not virus over expressing GFP, show attenuated H3K9/14Ac levels and cocaine-induced CPP (Kumar et al, 2005). When infused into the rat NAc shell, over expression of HDAC4, but not β-galactosidase, partially blocks cocaine self-administration-induced increases in H3K9/14Ac at the promoters of numerous genes implicated in behavioral responses to cocaine, including Cbp, Bdnf II and III, Fosb, Cdk5, Camk2a, Gria2, Grin2a, and Grin2b (Wang et al, 2010).

Like mice, the behavior of rats infused intra-NAc with HDAC4 over expressing vectors correlates with decreases in promoter H3 acetylation. Rats exhibit reductions in the breakpoint for cocaine self-administration as well as the gross quantity of cocaine self-administered (Wang et al, 2010). In contrast, HDAC4 over expression had no effect on responding for food pellets in the fixed ratio paradigm (Wang et al, 2010). Thus, manipulations of HDAC4 by viral mediated gene transfer show that HDAC4 mediates the acetylation of genes in the NAc critical for cocaine-related behaviors, and that it does indeed repress CPP acquisition and self-administration.

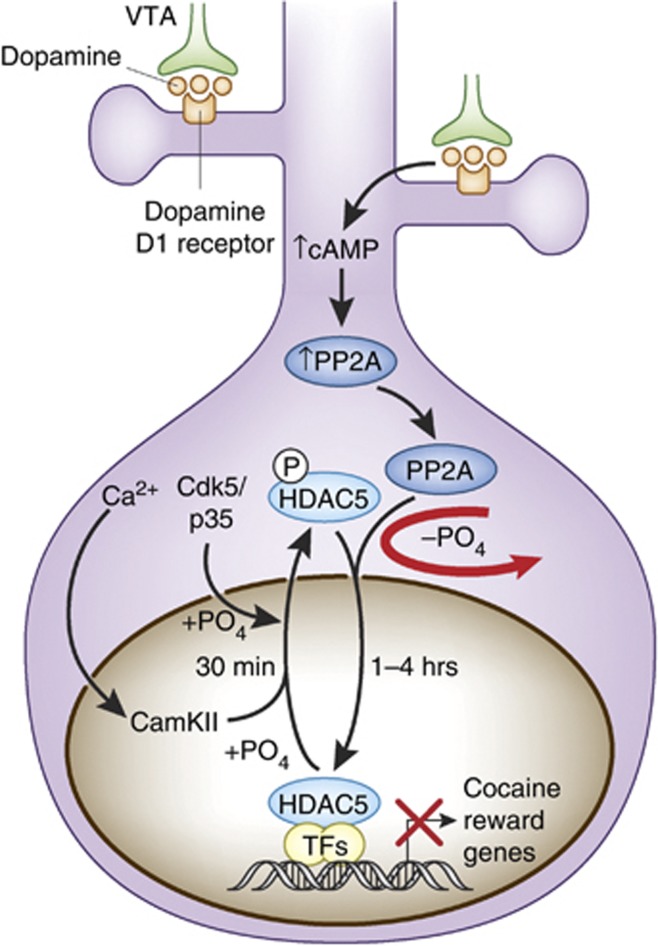

HDAC 5

This section highlights HDAC5 function because it is currently one of the best-studied HDACs involved in neural and behavioral responses to cocaine. Although HDAC5 mRNA levels in the NAc are unaffected by acute or chronic cocaine administration (Renthal et al, 2007; Deitrich et al, 2012; Host et al, 2012), cocaine post-translationally regulates phosphorylation of HDAC5, which facilitates nuclear export via phosphorylation (Renthal et al, 2007; Deitrich et al, 2012; Host et al, 2012) or import via dephosphorylation (Taniguchi et al, 2012). Figure 2 illustrates post-translational mechanisms of HDAC5 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling.

Figure 2.

Model of HDAC5 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling in response to cocaine-mediated phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Repeated cocaine administration causes CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of HDAC5 at serine 256. That phosphorylation facilitates nuclear export and sequestration in the cytoplasm, possibly via interactions with protein 14-3-3. Within 1 h after cocaine intake, though, cAMP-mediated activation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) results in dephosphorylation of HDAC5 at serine 279, which resides within a NLS. In consequence, HDAC5 is imported back into the nucleus where it can repress the expression of genes critical for cocaine reward. Adapted from Renthal et al (2007) and Taniguchi et al (2012).

Cocaine affects HDAC5 subcellular localization

After repeated cocaine injections (20 mg/kg IP), HDAC5 is phosphorylated in the mouse NAc at serine 259 (S259) by CaMKIIalpha within 30 min after the last injection, but not 24 h later (Renthal et al, 2007). Furthermore, cocaine self-administration induces rapid phosphorylation of HDAC5 S259 in the NAc by CaMKIIalpha and possibly CDK5, which facilitates nuclear export of phospho-HDAC5, sequestration in the cytoplasm and loss of function as a transcriptional repressor (Renthal et al, 2007; Kumar et al, 2005; Dietrich et al, 2012). Thus, cocaine dynamically regulates the subcellular localization and function of HDAC5. It should be noted, though, that antibodies specific for phospho-S259 HDAC5 also recognize phosphorylated HDAC4, HDAC7, and HDAC9 (Taniguchi et al, 2012). As a result, it remains unclear if cocaine-induced increases in phospho-S259 immunoreactivity reflect post-translational modification of HDAC5 specifically, or phosphorylation of other class IIa HDACs.

An acute IP injection of 20 mg/kg cocaine, or chronic dosing, increases phospho-HDAC5 levels in the rat striatum for up to 15 h post-injection (Deitrich et al, 2012), a phenomenon that does not occur in the mouse striatum (Renthal et al, 2007). Once phosphorylated, HDAC5 is transiently sequestered in the cytoplasm (possibly by interactions with 14-3-3 protein) where it is unable to repress transcription (Chawla et al, 2003; Renthal et al, 2007; Deitrich et al, 2012). Nuclear HDAC5 levels in the mouse NAc return to baseline levels by 24 h post-injection (Renthal et al, 2007), but in the rat NAc remain low even 20 h after an acute injection or the last injection of a chronic regimen (Deitrich et al, 2012). This direct contrast in the timecourse of cocaine-mediated, nucleocytoplasmic HDAC5 shuttling may indicate a species difference between rats and mice. The contrasting results may also be due to antibody specificity difference between rats and mice. Additionally, most antibodies that recognize HDAC5 also recognize other class IIa HDACs like HDAC4 due to a high degree of sequence homology between closely related HDACs (Taniguchi et al, 2012). In mice, HDAC5 knockouts can be used to determine specificity of the anti-HDAC5 antibody, but this is not the case in rats. Thus, other approaches such as RNA interference to knockdown HDAC5 levels in rats would be useful to verify antibody specificity and resolve this issue.

Not surprisingly, cocaine-mediated dephosphorylation was recently shown to dynamically regulate the rate of HDAC5 nuclear import in the rodent striatum (Taniguchi et al, 2012). In those studies, HDAC5-specific analysis was carried out by immunoprecipitating total HDAC5 and then immunoblotting with phosphorylation site-specific antibodies (Taniguchi et al, 2012). In this way, the authors avoided the confounds of immunoreactivity with other class IIa HDACs besides HDAC5. In the mouse NAc, 1 and 4 h after the last injection of chronically administered cocaine (20 mg/kg × 7 days), HDAC5 is dephosphorylated at serines 279 (S279), 259 and 498, indicating that cocaine stimulates the coordinated dephosphorylation of all three sites at those time points (Taniguchi et al, 2012). In those same mice, HDAC5 was concentrated in the nucleus 4 h after the last cocaine injection, but not after 1 or 24 h, compared with saline controls. In agreement with those chronic study observations, an acute IP injection of 5 mg/kg cocaine also reduces HDAC5 phospho-S279 levels 2 h after the injection (Taniguchi et al, 2012). In sum, these data suggest that cocaine causes temporally specific nuclear localization of HDAC5 by facilitating dephosphorylation.

The dephosphorylation of S279 may be mediated by D1-like receptor signaling in the striatum. The D1-like receptor agonist SKF81297 stimulates phospho-S279 dephosphorylation at 30 min and 3 h after administration (Taniguchi et al, 2012). In contrast, the D2-like receptor agonist quinpirole showed a trend for enhancing HDAC5 phospho-S279 (Taniguchi et al, 2012). These data indicate a complex counterbalancing act between D1- and D2-like receptor signaling that regulates HDAC5 phosphorylation.

DNA sequence alignment revealed that S279 in the Hdac5, Hdac4, and Hdac11 genes is surrounded by basic residues within a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and that it is evolutionarily conserved in many drug addiction model species, including zebrafish, rodents, monkeys, and humans (Taniguchi et al, 2012). In in vitro studies with primary cultured rat striatal neurons, S279 is a substrate for CDK5 phosphorylation and cAMP-dependent PP2A dephosphorylation (Taniguchi et al, 2012). CDK5 positively regulates dendritic arborization in NAc MSNs after chronic cocaine administration (Pulipparacharuvil et al, 2008) and PP2A activity is enhanced by elevated cAMP levels (Ahn et al, 2007). Thus, regulation of HDAC5 phosphorylation and subsequent nucleocytoplasmic shuttling by these two enzymes offers insight into the potential upstream second messenger signaling mechanisms regulating HDAC5 function after acute and chronic cocaine administration.

HDAC5 affects cocaine-mediated behaviors

In support of the idea that cocaine-mediated nuclear export and functional inactivation of HDAC5 allows for the transient expression of genes in the NAc responsible for chronic cocaine's reinforcing effects, Hdac5 knockout mice exhibit enhanced CPP acquisition after being pretreated for 1 week with a sensitizing regimen of cocaine (Renthal et al, 2007). In contrast, HDAC5 over expressing mice show reduced CPP that returns to wild-type levels after intra-NAc infusions of TSA (Renthal et al, 2007). Such a phenotypic reversal strongly suggests that HDAC5 over expression causes reduced CPP acquisition, an effect that can be prevented with HDAC inhibitor pretreatment. Importantly, gene microarray experiments conducted with NAc tissue from Hdac5 knockout mice and wild-type littermates reveals a plethora of cocaine-regulated genes dysregulated by the genetic deletion of Hdac5 (Renthal et al, 2007). Together, these data indicate that chronic cocaine-induced phosphorylation of class IIa HDAC(s) (likely HDAC5 [S259]) in the NAc via CaMKIIalpha facilitates HDAC nuclear export and cocaine-induced gene expression that, in part, underlies CPP acquisition (Renthal et al, 2007).

The effects of S279 phosphorylation on cocaine-induced CPP (5 mg/kg conditioning) were examined using viral gene transfer (Taniguchi et al, 2012). In those studies similar expression levels of endogenous, S279A (a non-phosphorylatable point mutation) and S279E (a phosphomimetic point mutation) HDAC5 was observed in the mouse NAc. Mice expressing HDAC5 S279A during CPP conditioning exhibit enhanced CPP acquisition compared with GFP-infected controls, while HDAC5 S279E-expressing mice do not show altered preference compared with controls. That enhancement of CPP is only observed when HDAC5 S279A is infused 3 days before conditioning, but not when infused after the conditioning, 3 days before the preference test (Taniguchi et al, 2012). That suggests that HDAC5 dephosphorylation is important for the acquisition of CPP, but perhaps not its expression (Taniguchi et al, 2012). Furthermore, during 1% sucrose preference tests, HDAC5 S279A expression has no effect on acquisition. These results suggest that HDAC5 S279A counteracts the rewarding and reinforcing properties of cocaine, but not natural reward behavior.

In sum, these data indicate that HDAC5, when dephosphorylated at S279, and possibly S259 and S498, by a D1-like receptor stimulated pathway translocates to the nucleus via NLS-dependent mechanisms and represses CPP acquisition. That effect on behavior is only apparent when HDAC5 S279A (non-phosphorylatable, thus presumed to be localized to the nucleus) is expressed during conditioning, but not when HDAC5 S279A is expressed after conditioning, 3 days before the acquisition test. This latter result strongly suggests that HDAC5 mediates transcriptional responses associated with cocaine's ability to induce CPP acquisition.

However, two key controls are missing in the study by Taniguchi et al (2012). First, due technical limitations, the authors did not investigate the subcellular localization of HDAC5 S279A before and after cocaine in vivo. Although the authors show that when over expressed in primary, cultured rat striatal neurons, HDAC5 S279A is concentrated in the nucleus, that has not been replicated after in vivo viral gene transfer in the mouse NAc. It is possible that mice and rats regulate HDAC5 subcellular localization differently (eg, data from Host et al, 2012 show that after an acute injection of cocaine, HDAC5 is phosphorylated and remains in the cytoplasm for up to 20 h in the rat NAc, while Renthal et al, 2007 show no effects of acute cocaine treatment). Furthermore, the phosphorylation state of S259 and/or S498 may affect nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (as shown by Renthal et al, 2007 for phospho-S259). Second, there is no evidence that HDAC5 S279A counteracts cocaine-induced histone acetylation or transcription. Thus, as the findings about HDAC5 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and HDAC5-mediated behavioral responses to cocaine are groundbreaking, it will be important to replicate the in vitro findings regarding HDAC5-mediated, cocaine-induced histone acetylation in vivo.

HDACs may function in multi-protein complexes in vivo

Although it is assumed that the deacetylase activity of HDAC4 or 5 is key to mediating cocaine-induced acetylation and subsequent effects on drug-seeking behavior, clear evidence demonstrating the importance of the catalytic activity of these enzymes is missing. This is also true in the learning and memory field, in which there is no clear evidence demonstrating that the enzymatic activity of an HDAC is absolutely necessary. One can imagine numerous scenarios in which an HDAC catalytic domain simply serves bromo-domain type functions, or performs critical non-histone acetylation functions, or recruits nucleosome remodeling machinery. Interestingly, although loss of HDAC function is associated with increased histone acetylation, that is not because of the loss of HDAC function directly. That is due to HAT activity. Thus, although it is nearly given that HDAC enzymatic activity is necessary for cocaine's actions, there is no definitive data demonstrating this yet.

For example, even though over expression of mutants harboring deletions of the HDAC and C-terminus domains have no effect on H3K/14 acetylation or self-administration (HDAC4; Wang et al, 2010) or CPP acquisition (HDAC5; Renthal et al, 2007), little can be concluded about the role of HDAC4 or 5 enzymatic activities because the deletions encompass regions required for protein–protein interactions. For example, HDAC3 interacts with HDAC5 via HDAC5's catalytic domain (Maze and Nestler, 2011). Thus, the mutated HDACs 4 and 5 generated by Wang et al (2010) and Renthal et al (2007) may simply be unable to participate in the assembly of co-factors required for transcriptional repression. To address that issue, HDAC4 and HDAC5 mutants harboring point mutations in the catalytic domains (as in Lahm et al, 2007) that do not disrupt the formation of co-repressor complexes need to be examined not only in the addiction field, but also with regard to HDAC function in neurodegeneration and learning and memory fields.

Class I HDACs implicated in molecular and behavioral responses to cocaine

HDAC 1

HDAC1 is a class I enzyme that associates with HDAC2 in co-repressor complexes, but not with HDAC3, HDAC4 or HDAC5 (Laherty et al, 1997). Although the role of HDAC1 in mediating cocaine-induced histone acetylation has never been reported, it is critical for desensitization of Fos transcription after repeated injections of amphetamine (Renthal et al, 2008). In that study, DeltaFOSB interacts with HDAC1 at the Fos promoter after chronic amphetamine administration in the rat striatum, which results in H3K9/14Ac deacetylation and transcriptional repression. Region-specific knockout of HDAC1 in the striatum results in de-repression of the Fos gene and chronic amphetamine-induced transcription (Renthal et al, 2008). Thus, HDAC1 mediates desensitization of the Fos gene after repeated injections of amphetamine, a psychostimulant closely related to cocaine, yet distinct in its acute mechanisms of drug action. These data imply that cocaine-induced histone acetylation of H3K9/14 (which is also implicated in regulating Fos desensitization after repeated cocaine injections (Kumar et al, 2005; Malvaez et al, 2011)) may also involve HDAC1.

HDAC 2

HDAC2, also a class I HDAC, is best known as a negative regulator of long-term memory formation in the forebrain (Guan et al, 2009). Recently, it has also been implicated in cocaine-mediated neuroplasticity, although there is no direct evidence that it is involved in cocaine-mediated histone acetylation. RT–qPCR reveals that in rats, after 4 days of cocaine self-administration, HDAC2 mRNA levels are increased in the cingulate cortex (CgCx), caudate putamen, (CPu) and NAc compared with saline controls (Host et al, 2012). HDAC2 immunoreactivity is elevated in the CgCx and CPu, but not the NAc. These data suggest that HDAC2 may be involved in cocaine-induced neuroplasticity mediated by histone acetylation in those three brain regions.

In support of that idea, HDAC2 is present in a multi-protein, transcriptional repressor complex in the rat NAc with the TF NZF2b/7ZFMyt1 (Romm et al, 2005; Chandrasekar and Dreyer, 2010). NZF2b/7ZFMyt1 is upregulated in the NAc after chronic cocaine administration and represses as well as facilitates the expression of genes necessary for cocaine's locomotor effects (Chandrasekar and Dreyer, 2010b), and self-administration (Chandrasekar and Dreyer, 2010). A precise role for HDAC2 in cocaine-induced, NZF2b/7ZFMyt1-mediated transcriptional responses, however, remains unstudied.

Involvement of Class III HDACs, SIRT 1 and 2

The class III HDACs, SIRT (silent information regulator of transcription) 1 and SIRT 2 are also regulated by repeated cocaine administration (Renthal et al, 2009). In the mouse NAc, repeated administration of cocaine increases the levels of H3K9/14Ac and DeltaFOSB binding at the promoters of both genes concomitant with augmented mRNA levels of both SIRT 1 and SIRT 2. Ex vivo enzyme catalysis assays using fluorescent substrates of SIRT 1 or SIRT 2 reveal that the catalytic activities of those HDACs isolated from chronic cocaine-treated NAc lysates are likewise augmented. On the other hand, SIRT 1 and 2 isolated from the NAc of mice treated with acute cocaine do not show enhanced enzymatic activities (Renthal et al, 2009). These data suggest that SIRTs may be involved in cocaine-mediated histone acetylation.

To investigate a functional consequence of chronic cocaine-mediated upregulation of SIRT 1 and 2 in the NAc, a pharmacological activator (resveratrol) or inhibitor (sirtinol) of sirtuin activity was applied to NAc slices during whole-cell current-clamp recordings from medium spiny neurons (MSNs; Renthal et al, 2009). Somewhat surprisingly, SIRT activation by resveratrol potently increased NAc MSN excitability and reduced the rheobase (the minimum current necessary to elicit an action potential). SIRT inhibition with sirtinol had the opposite effect (Renthal et al, 2009). These results suggest that SIRT activity positively regulates NAc activation and possibly addiction-like behaviors.

Behavioral studies were carried out to address that possibility. Systemic administration of resveratrol enhanced cocaine-induced CPP and intra-NAc infusions of sirtinol by osmotic minipump reduced preference (Renthal et al, 2009). Finally, the same study found that in rats self-administering cocaine, intra-NAc infusions of sirtinol reduced the number of cocaine infusions self-administered.

These data are counter to previously reported results examining the role of HDACs in cocaine-induced histone acetylation and behaviors. An overarching hypothesis regarding the role of HDACs in drug-seeking behavior is that HDAC inhibition facilitates transcription of genes required for neuroplastic adaptations to cocaine. That in turn alters the function and morphology of neuronal ensembles throughout the mesocorticolimbic pathway, which most likely underlies behavioral abnormalities characteristic of addiction, such as self-administration and CPP (Renthal et al, 2009; Maze and Nestler, 2011). SIRTs appear to act in the opposite way by increasing in abundance and catalytic activity after chronic, but not acute cocaine intake, facilitating NAc MSN excitability, and facilitating self-administration and CPP. Thus, SIRT 1 and/or 2 appear to mediate a ‘drug-induced, positive feed-back loop' that facilitates cocaine-seeking behaviors (Harting and Knoll, 2009).

There is, as yet, no direct evidence that sirtuins negatively regulate cocaine-induced gene expression. In contrast to other HDAC family members, these mechanistically distinct, NAD+-dependent HDACs are well known to deacetylate non-histone proteins that regulate fundamental cell biological processes including, but not limited to, gene expression, genome stability, mitosis, nutrient metabolism, aging, mitochondrial function, and cell motility (for reviews, see Harting and Knoll, 2009; Finkel et al, 2009). As such, studies of how SIRT1 and 2 facilitate drug-seeking behavior represent a novel frontier in understanding the complicated role of chromatin modifying enzymes in the development of addiction.

SECTION III. ROLE OF THE HAT CBP IN COCAINE-INDUCED HISTONE ACETYLATION

In this portion of the review, cocaine regulation of HAT activity is discussed, with a special emphasis on CBP. HATs counteract HDACs at gene promoters by adding acetyl groups to specific histone lysines, which relieves histone–DNA electrostatic interactions, relaxes chromatin and allows for transcriptional initiation (see Kouzarides, 2007 for review). One of the best-studied HATs is CBP, which binds specifically to serine 133 phospho-CREB at the promoters of P-CREB-regulated genes and facilitates transcription as a scaffolding platform for other proteins involved in transcriptional initiation and by acetylating histones (Chrivia et al, 1993). Although cocaine-induced, P-CREB-mediated transcription of immediate early genes and other effector genes in numerous regions of the brain reward pathway has been identified as one mechanism of neuroplasticity associated with drug-seeking behaviors (Carlezon et al, 1998; McClung and Nestler, 2003; Carlezon et al, 2005), little is known about the role of brain region-specific CBP in neuroadaptive and behavioral responses to cocaine.

CBP in the NAc

The evidence that CBP in the NAc is involved in cocaine-mediated neural and behavioral plasticity comes from self-administration and experimenter administered cocaine studies in mice. In the mouse NAc, chronic self-administration is associated with increases in H3K9/14Ac in the Cbp gene promoter and increases in Cbp mRNA abundance (Wang et al, 2010). To investigate the role of CBP in the mouse NAc in cocaine-induced transcription and behavior, Malvaez et al (2011) examined transcriptional and behavioral responses to cocaine in CBPFLOX/FLOX mice harboring LoxP sites that surround an essential exon of the Cbp gene required for expression (fully described in Kang-Decker et al, 2004; see Figure 3). By infusing AAV-Cre into the NAc, focal homozygous deletions of Cbp were generated in the NAc of fully developed, adult mice (Malvaez et al, 2011), avoiding the developmental confounds associated with experimenting on traditional CBP knockout mice (Tanaka et al, 1997; Levine et al, 2005). Specifically, traditional knockout mice homozygous for Cbp deletion are embryonic lethal and heterozygotes suffer from physical and mental defects due to CBP's essential function during epigenetic regulation of the developing fetus (Tanaka et al, 1997).

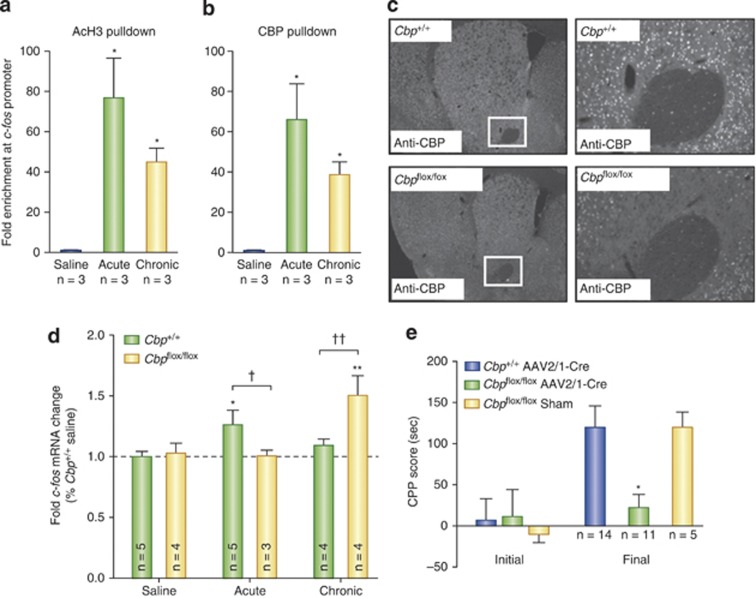

Figure 3.

Cocaine-induced Fos expression is regulated by CBP. (a) H3K14 acetylation of the Fos promoter and (b) CBP recruitment to the promoter are increased 1 h after acute and chronic cocaine injections. (c) AAV-Cre infusions generate focal, homozygous deletions of Cbp specifically in the NAc of CBPflox/flox mice, but not CBP+/+ littermates. (d) In the NAc of CBP+/+ mice, acute cocaine induces Fos expression, while chronic cocaine does not. CBPflox/flox mice, on the other hand, exhibit no increases in Fos after acute cocaine. Chronic cocaine treatment was associated with enhanced c-Fos mRNA in CBPflox/flox mice. (e) NAc-specific deletion of Cbp impairs cocaine-induced CPP acquisition. CBPflox/flox sham animals underwent surgery and AAV infusion but did not harbor Cbp deletions. Adapted from Malvaez et al (2011). For a, b and d, significantly different from saline, *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Significantly different from Cbp+/+, †P<0.05, ††P<0.01, For e, significantly different from Cbp+/+, *P<0.05.

After saline administration, intra-NAc, AAV-Cre-infused wild-type littermates (CBP+/+) and CBPFLOX/FLOX mice exhibit no differences in the global levels of NAc H3K14Ac or H2BK12Ac (Malvaez et al, 2011). CBP does, however, positively regulate global levels of H3K14Ac and H2BK12Ac in the NAc after both acute and chronic cocaine administration (Malvaez et al, 2011). After a single injection of cocaine or repeated injections, the levels of cocaine-induced H3K14Ac or H2BK12Ac are enhanced above saline controls only in AAV-Cre-infused CBP+/+, but not CBPFLOX/FLOX, mice (Malvaez et al, 2011). These data strongly suggest that CBP in the NAc mediates cocaine-induced acetylation at those two sites. No differences in the levels of H4K12Ac (which was reduced after acute and chronic cocaine treatment) or H3K9Me2 were observed between the two genotypes after saline, acute, or chronic cocaine administration (Malvaez et al, 2011).

An important question is: does cocaine-induced H3K14Ac mediated by CBP affect transcription of genes implicated in neural and behavioral responses to cocaine? In the case of Fos, the answer is yes. When wild-type C57BL/6 mice were treated with acute cocaine, ChIP assays revealed increased association of CBP with the Fos promoter concomitant with enhanced levels of promoter H3K14Ac (Figure 3a; Malvaez et al, 2011). An intriguing set of observations from that study is that, in C57 mice repeatedly injected with cocaine, the levels of H3K14Ac and CBP at the Fos promoter are also enhanced in the NAc above levels observed after saline treatment (Malvaez et al, 2011). This ChIP result using anti-H3K14Ac IgG is in contrast to what was reported by Kumar et al (2005) and may reflect differences in administration paradigms (see Table 1) and/or antibody specificity. Kumar et al (2005) used antibodies that recognize both H3K9Ac and H3K14Ac, while Malvaez et al (2011) used antibodies selective for only H3K14Ac. The fact that the H3K9/14Ac antibody primarily recognizes H3K9Ac vs H3K14Ac (Edmondson et al, 2002) highlights one of the many technical limitations inherent to interpreting ChIP data with acetylated histone antibodies that are not fully selective for individual lysines on individual histones. Future studies may want to use multiple antibodies to verify any results.

Although c-Fos mRNA levels were not examined in those acute and chronic cocaine-treated C57 mice, c-Fos mRNA levels were enhanced after acute, but not repeated, cocaine injections in AAV-Cre-infused CBP+/+ mice (Figure 3d; Malvaez et al, 2011). This result for CBP+/+ mice is in agreement with many reports that have observed desensitization of Fos transcriptional responses after repeated cocaine injections (Hope et al, 1992; Daunais et al, 1993). These data indicate that CBP regulates cocaine-induced expression of Fos via acetylation at H3K14 in the Fos promoter.

Interestingly, chronic cocaine treatment enhances c-Fos mRNA levels above and beyond the effects of repeated saline injections in AAV-Cre-infused CBPFLOX/FLOX, but not CBP+/+, mice (Figure 3d; Malvaez et al, 2011). The chronic cocaine-induced enhancement of c-Fos mRNA in CBPFLOX/FLOX mice harboring NAc-specific deletions is surprising because CBP has thus far been implicated in positively regulating Fos. Thus, deletion of Cbp was predicted to prevent Fos over expression (as was observed after acute administration; Malvaez et al, 2011). Though difficult to interpret now, these data further emphasize the infancy of the field in regards to studying cocaine-mediated, brain-region-specific activities of CBP and the need to use genetic manipulations like the LoxP-Cre system in future studies. It is clear, however, that in response to cocaine administration, CBP in the NAc acetylates H3K14 in the Fos promoter and that increased acetylation is associated with increases in c-Fos mRNA.

Furthermore, Fos may not be the only gene associated with cocaine-induced neuroplasticity regulated by CBP in the mouse NAc. In a different mouse model, using heterozygotes from traditional Cbp knockout animals (Cbp-haploinsufficient mice; fully described in Tanaka et al, 1997), CBP in the NAc also acetylates H4 in the Fosb promoter that correlates with an increase in FosB mRNA after acute cocaine administration (Levine et al, 2005).

In Levine et al's study (2005), 10 days of cocaine administration results in accumulation of the TF DeltaFOSB, which is encoded by the Fosb gene and regulates genes important for the development and maintenance of addiction (Nestler, 2004b). Although less DeltaFOSB is observed in the striatum of mice harboring only a single, functional Cbp allele (Levine et al, 2005), that does not necessarily mean that CBP regulates DeltaFOSB expression. To-date, no group has examined CBP promoter occupancy of the Fosb gene after 10 days of cocaine treatment to determine if increased CBP-mediated Fosb transcription is responsible for cocaine-induced accumulation of DeltaFOSB.

Behaviorally, focal homozygous deletion of Cbp in the NAc reduces sensitivity to the locomotor activating and rewarding effects of cocaine (Malvaez et al, 2011). Intra-NAc AAV-Cre-infused CBPFLOX/FLOX mice show less cocaine-induced locomotion and sensitization compared with AAV-Cre-infused CBP+/+ littermates. Mice harboring NAc-specific deletions also fail to acquire cocaine-induced CPP after conditioning with 2.5 mg/kg cocaine (Figure 3e; Malvaez et al, 2011). In a separate study, curcumin (a non-specific HAT inhibitor) had a similar effect of suppressing cocaine-induced CPP acquisition (Hui et al, 2010). Levine et al (2005) observed the same reductions in cocaine-induced locomotor and sensitization responses, though they did not perform CPP. Together, these data suggest that CBP in the NAc regulates transcription of Fos and Fosb via cocaine-induced histone acetylation, in an administration paradigm-specific manner, and that CBP-mediated regulation of those genes is one mechanism of neuroplasticity underlying behavioral responses to cocaine, including locomotor sensitization (Levine et al, 2005; Malvaez et al, 2011) and CPP acquisition (Malvaez et al, 2011).

CBP in the VTA

The evidence that CBP in the VTA is involved in cocaine-mediated neural and behavioral plasticity comes from examining transcriptional regulation of Bdnf, a P-CREB regulated gene (West et al, 2001; Sadri-Vakili et al, 2010), in the VTA. It was found that cocaine self-administration followed by 7 days of forced abstinence increases CBP binding and H3 acetylation at Bdnf exon I-containing promoters in the VTA (Schmidt et al, 2012). It was previously shown that forced abstinence after self-administration increases BDNF protein levels in the VTA, NAc, and amygdala (Grimm et al, 2003). Thus, the levels of CBP bound to the Bdnf I promoter are increased after self-administration and forced abstinence, which correlates with increases in Bdnf I promoter acetylation and BDNF expression. These data suggest that CBP may regulate BDNF expression in the VTA during cocaine withdrawal.

In sum, CBP in the NAc and VTA may facilitate promoter acetylation and gene expression changes that most likely underlie behaviors widely accepted as indexes of addiction-like behaviors, such as CPP acquisition and cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization. However, similar to the lack of evidence clearly demonstrating that deacetylase activity of HDACs is truly involved in HDAC-mediated mechanisms, the same issue arises for CBP and other HATs. There is no clear direct evidence demonstrating that the HAT activity of CBP is truly involved. In the learning and memory field, this was best addressed by a study examining a point mutation in the HAT domain of CBP, which correlated with decreased histone acetylation, decreased gene expression, and impaired long-term memory (Korzus et al, 2004). Thus, although it is very likely that CBP-dependent mechanisms involve its HAT domain, more direct evidence is needed.

SECTION IV. EXTINCTION OF REWARD-RELATED LEARNING

The review thus far has focused on data examining acquisition and consolidation of CPP and self-administration. HATs and HDACs, though, are not only involved in CPP acquisition, they also regulate long-term memory formation. In the learning and memory field, CBP in the hippocampus is critical for long-term memory formation and some forms of LTP (Barret et al, 2011). HDAC inhibitors non-specific for class I family members are known to enhance transcription-dependent long-term memory formation in rodents by increasing histone acetylation in the hippocampus (and possibly other brain regions; for review, see Barrett and Wood, 2008).

Specifically, HDAC inhibitors enhance long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices and intrahippocampal infusions of inhibitors enhance long-term memory for object location memory (Roozendaal et al, 2010; McQuown et al, 2011); contextual fear conditioning (Vecsey et al, 2007); extinction of contextual fear responses (Lattal et al, 2007; Stafford et al, 2012); and Morris water maze performance (Fischer et al, 2007). There is great interest in identifying the specific HDAC family members in specific brain regions targeted by HDAC inhibitors that mediate long-term memory formation. As discussed in this review, HDAC2 (Guan et al, 2009) and HDAC3 (McQuown et al, 2011) are two such enzymes.

Alterations in self-administration break points and cocaine-induced CPP acquisition observed in experiments manipulating the expression or activity of CBP (CPP; Malvaez et al, 2011), HDAC4 (CPP; Kumar et al, 2005; self-administration, Wang et al, 2010) or HDAC5 (CPP, Renthal et al 2007; Taniguchi et al, 2012) highlights the fact that histone acetylation is a common, underlying molecular mechanism of both cocaine-induced neuroplasticity associated with addiction-like behaviors and long-term memory formation (Alberini, 2009; Barrett and Wood, 2008 [review] McQuown and Wood, 2010 [review]).

One hypothesis about the neurobiological mechanisms underlying drug craving and vulnerability to relapse is that neuroplasticity in the brain reward pathway strengthens the associative memories of environmental stimuli with cocaine's effects via transcriptional regulation (McClung and Nestler, 2008). In animal models of addiction, cocaine strengthens associations between cocaine context-associated cues and the drug's reinforcing effects (Everitt and Robbins, 2005; Hyman et al, 2006). In humans, craving and relapse are triggered by exposure to contextual cues such as paraphernalia, places or people previously associated with cocaine use (O′Brien et al, 1998; Kilts et al, 2001; Hyman et al, 2006). Those cocaine-associated contexts that elicit cocaine cravings activate brain regions responsible for stimulus–reward associations, including the prelimbic cortex, hippocampus, and NAc (Ehrman et al, 1992; Kilts et al, 2001; Hyman, 2005). Since drug-related stimuli trigger drug-seeking behaviors through associative learning, it is hypothesized that similar molecular mechanisms responsible for long-term memory formation also participate in the formation of long-term, cocaine-context-associated memories and cocaine-seeking behaviors (Hyman and Malenka, 2001; Nestler, 2002; Everitt and Robbins, 2005; Everitt et al, 2008; McClung and Nestler, 2008; Malvaez et al, 2009).

This suggests that the same enzymes responsible for histone acetylation/deacetylation during memory formation may be involved in associative learning during both CPP acquisition and extinction. An important theoretical question is: can these enzymes be manipulated to overcome cocaine action and behavioral responses to the drug?

To begin to address that question, the ability of NaBut to facilitate extinction learning after cocaine-induced CPP acquisition was examined (Malvaez et al, 2010). When NaBut is administered immediately after the acquisition test (extinction day 1), during the transcription-dependent consolidation phase of memory formation, it facilitates CPP extinction in the very next trial (extinction day 2; Malvaez et al, 2010). In control experiments, NaBut administered 10 h after the extinction test on day 1 has no effect on extinction. Furthermore, NaBut-facilitated CPP extinction was resistant to drug-induced reinstatement. Thus, NaBut can facilitate extinction of cocaine-induced CPP when NaBut is administered during the consolidation phase of memory formation during extinction learning, and not later (ie, 10 h post-acquisition test).

Altogether, the studies of facilitated CPP extinction using NaBut (Malvaez et al, 2010) are intriguing in that they implicate learning and memory mechanisms involved in CPP extinction. This is because Hdac3, Fos, and Nr4a2 in the mouse hippocampus are critical, negative regulators of long-term memory formation (McQuown et al, 2011). These data provide rationale to further investigate whether histone acetylation occurs in overlapping reward and learning and memory neurocircuits at the promoters of genes involved in both memory processes and addiction-like behaviors. If so, then cocaine-induced histone acetylation may be one mechanism by which strong cocaine-context associative memories are formed. Those memories could underlie the transformation of cocaine-seeking behaviors into stable, long-lasting behavioral abnormalities characteristic of addiction by facilitating cocaine craving, which can occur sometimes years after drug abstinence.

Conclusion

The growing body of evidence demonstrating that epigenetic mechanisms underlie cocaine-induced changes in neural plasticity and persistent changes in behavior has dramatically changed the conceptual framework for understanding substance abuse disorders. Similar to the findings in the learning and memory field, in which HDACs are key molecular brake pads (McQuown and Wood, 2011b) that negatively regulate gene expression required for long-term memory processes, cocaine may induce long-term changes via disruption of normal HDAC function. In the learning and memory field, HDAC inhibition can transform a subthreshold learning event into a robust long-term memory and also generate a form of long-term memory that persists beyond the point at which normal memory fails. HDAC disruption by repeated cocaine use may be a key step in the transition from recreational cocaine use to compulsive drug-taking behavior. Conversely, facilitating extinction of drug-seeking behavior via HDAC inhibition, resulting in robust and persistent extinction, may yield an exciting and novel approach to therapy. Thus, continuing to examine the epigenetic mechanisms underlying the actions of drugs of abuse is paramount to understanding fundamental mechanisms as well as guiding new therapeutic approaches.

Future directions

A major goal of drug addiction research is to develop pharmacotherapies for the treatment of cocaine addiction. The epigenetic mechanisms discussed in this review represent a novel frontier for medication development. For example, there is an emerging understanding of how cocaine-context-associated memories are formed and extinguished via chromatin modifying mechanisms. That knowledge may lead to the development of novel therapies to treat cocaine addiction that have no effect on the reward pathway, and would thus presumably have fewer mood altering affects that could prevent abstinence. Much about the specific mechanisms of cocaine-mediated chromatin modifications remains to be discovered, though. For instance, although neuroplastic alterations occur in many regions of the reward pathway, it is important to remember those brain nuclei are heterogenous, complex structures with many different neuronal subtypes and non-neuronal cells such as astrocytes that all play individual roles in mediating neuroplastic responses to cocaine. Future studies must begin to separate these heterogeneous cell populations to examine the role of individual cell types in addiction.

With regard to histone acetylation enzymes, HATs and HDACs, most studies focus on the effect of these enzymes on histones themselves. However, all of these enzymes have non-histone substrates. These may be equally, if not more, important as histone substrates. Additionally, one of the most amazing aspects of histone post-translational modification mechanisms is that these modifications serve as a signal integration platform that is the physical location of where genetics interacts with environment via signaling events. Lastly, there are many mechanisms by which chromatin structure is regulated in the service of directing gene expression and histone modification is only one of those. Many of those other mechanisms are discussed in this special issue of NPP. However, the conspicuously missing mechanism that has not been examined in any studies with regard to CNS function is nucleosome remodeling. This is an untapped frontier, which is at the forefront of cancer research.

Lastly, a major question remains as to how reversible modifications such as histone acetylation can have such lasting effects on the potential of a gene to be transcribed, either increasing the probability that gene will be expressed after repeated cocaine intake (eg, Cdk5) or decreasing the probability (eg, Fos). In addition, studies looking at how chromatin modifications affect transcriptional potential during the different phases of the addiction cycle (intoxication, withdrawal, and relapse) will provide much needed insight into how neuroplastic alterations are associated with the drastically different behaviors characteristic of each phase of addiction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH (MH081004) and NIDA (DA025922; DA031989) grants to MAW, as well as a T32 (NS045540) fellowship to GAR (PI, TZB).

The authors declare that over the past 3 years MAW and GAR have received compensation from Repligen Corp in the form of a Sponsored Research Agreement.

References

- Ahn JH, McAvoy T, Rakhilin SV, Nishi A, Greengard P, Nairn AC. Protein kinase A activates protein phosphatase 2A by phosphorylation of the B56delta subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611532104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberini CM. Transcription factors in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:121–145. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alenghat T, Meyers K, Mullican SE, Leitner K, Adeniji-Adele A, Avila J, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 govern circadian metabolic physiology. Nature. 2008;456:997–1000. doi: 10.1038/nature07541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett RM, Wood MA. Beyond transcription factors: the role of chromatin modifying enzymes in regulating transcription required for memory. Learn Mem. 2008;15:460–467. doi: 10.1101/lm.917508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett RM, Malvaez M, Kramar E, Matheos DP, Arrizon A, Cabrera SM, et al. Hippocampal focal knockout of CBP affects specific histone modifications, long-term potentiation, and long-term memory. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1545–1556. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind WJ, Whitfield TW, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW, McGinty JF. A single intra-PFC infusion of BDNF prevents cocaine-induced alterations in extracellular glutamate within the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3715–3719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5457-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind WJ, See RE, Fuchs RA, Ghee SM, Whitfield TW, Miller SW, et al. A BDNF infusion into the medial prefrontal cortex suppresses cocaine seeking in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:757–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibb JA, Chen J, Taylor JR, Svenningsson P, Nishi A, Snyder GL, et al. Effects of chronic exposure to cocaine are regulated by the neuronal protein Cdk5. Nature. 2001;410:376–380. doi: 10.1038/35066591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Thome J, Olson VG, Lane-Ladd SB, Brodkin ES, Hiroi N, et al. Regulation of cocaine reward by CREB. Science. 1998;282:2272–2275. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]