Background: Resveratrol has been suggested to have protective effects against many diseases, but its biological actions on brain in healthy subjects are unclear.

Results: Resveratrol impaired hippocampal neurogenesis and memory acquisition by AMPK activation and suppression of pCREB and BDNF.

Conclusion: Resveratrol impairs hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function.

Significance: Unlike DR and exercise, resveratrol can adversely affect neurogenesis and cognition.

Keywords: AMP-activated Kinase (AMPK), Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), CREB, Neural Stem Cell, Neurogenesis, Resveratrol

Abstract

Resveratrol is a phytoalexin and natural phenol that is present at relatively high concentrations in peanuts and red grapes and wine. Based upon studies of yeast and invertebrate models, it has been proposed that ingestion of resveratrol may also have anti-aging actions in mammals including humans. It has been suggested that resveratrol exerts its beneficial effects on health by activating the same cellular signaling pathways that are activated by dietary energy restriction (DR). Some studies have reported therapeutic actions of resveratrol in animal models of metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders. However, the effects of resveratrol on cell, tissue and organ function in healthy subjects are largely unknown. In the present study, we evaluated the potential effects of resveratrol on the proliferation and survival of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in culture, and in the hippocampus of healthy young adult mice. Resveratrol reduced the proliferation of cultured mouse multi-potent NPCs, and activated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), in a concentration-dependent manner. Administration of resveratrol to mice (1–10 mg/kg) resulted in activation of AMPK, and reduced the proliferation and survival of NPCs in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Resveratrol down-regulated the levels of the phosphorylated form of cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (pCREB) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus. Finally, resveratrol-treated mice exhibited deficits in hippocampus-dependent spatial learning and memory. Our findings suggest that resveratrol, unlike DR, adversely affects hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function by a mechanism involving activation of AMPK and suppression of CREB and BDNF signaling.

Introduction

Resveratrol (trans-3,5,4′-trihydroxystilbene) is a phenolic phytoalexin that is a constituent of grapes, raspberries, mulberries, pistachios, and peanuts. Resveratrol is generally present in its trans- and cis- forms, but only the trans-form has known biologic activities. Previous findings have suggested that resveratrol has anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties (1–3), related to an ability to modulate intracellular signaling pathways including those involving cellular stress-responsive transcription factors such as NF-κB and kinases such as ERK, JNK, and p38 (4–6). In addition, it has been reported that resveratrol can protect neurons against dysfunction and degeneration in experimental models of ischemic stroke, Alzheimer disease (AD), and Parkinson disease (PD) (7–9). However, adverse effects of resveratrol on neurons have been reported in other models of neurodegeneration (10), and the actions of resveratrol on cells in the healthy brain are unknown.

The generation of newborn cells is maintained throughout life in the hippocampus of the mammalian brain by the proliferation, differentiation and migration of adult neural progenitor cells (NPCs),2 and their eventual integration into neural networks (11). This process of neurogenesis is regulated by various signals in the local environment (niche) of the NPCs including fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), Notch ligands, Wnt, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (12–17). Increasing evidence suggests that newborn neurons contribute to new memories and stabilize old memories by making connections with existing neurons in the hippocampus and adjacent entorhinal cortex (18).

Interestingly, resveratrol can extend the lifespan of yeast, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila, and it has been proposed that such anti-aging effects of resveratrol are mediated by a mechanism similar to that by which dietary energy restriction (DR) extends lifespan (19–21). We previously reported that DR enhances hippocampal neurogenesis in mice by increasing NPCs survival; the underlying mechanism involves up-regulation of the expression of BDNF (22–24). We therefore undertook this study to determine if and how resveratrol might influence hippocampal neurogenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Resveratrol and 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were obtained from Sigma. 5′-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was purchased from ACROS organics (Fair Lawn, NJ). 2′-7′-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA), Hoechst 33342, and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from Invitrogen Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Compound C was obtained from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany).

Cell Culture Methods

To investigate the potential effects of resveratrol on NPCs, we used two different NPCs types: 1) C17.2 NPCs, which are multipotent and can differentiate into several cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes (25); these cells are able to integrate into the adult brain and differentiate into neurons and glia after grafting (26, 27). C17.2 NPCs (a generous gift from C. Cepko at Harvard University) were maintained in plastic culture flasks in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 5% horse serum, and 2 mm glutamine in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere at 37 °C. Resveratrol (trans-3,4′,-5-trihydroxystilebene; purity > 99%) was dissolved with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); an equivalent amount of DMSO (0.1% final concentration) was added to control cultures. 2) Primary embryonic mouse cerebral cortical NPCs were maintained as self-renewing stem cells within neurospheres. To establish cultures of primary embryonic cortical NPCs, pregnant C57BL/6 mice were sacrificed on gestational day 13 by cervical dislocation. Embryos were collected and excised brains were placed in ice-cold Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hank's Balanced Saline Solution (HBSS; WelGENE Inc., Korea) containing 0.1 mg/ml gentamycin. Meninges were removed and cortical neuroepithelium was dissected and placed in cold HBSS. After centrifugation (75 g, 10 min), brain tissues were resuspended in 2 mg/ml trypsin/EDTA solution. Trypsinization was performed under gentle agitation for 12–15 min at room temperature, and the reaction was stopped by adding 1.5 mg/ml of trypsin inhibitor in HBSS. Cells were then dissociated by gentle trituration using a fire-polished Pasteur pipette to yield suspensions of single cells or small cell clusters. These dissociated cells were diluted in culture medium (DMEM/F12 containing B27 supplements and 40 ng/ml of basic fibroblast growth factor) and plated into 24-well plates or plastic culture dishes at desired cell densities. For primary cortical neuron cultures, embryonic mouse cortex was established from the 18-day embryos of C57BL/6 mice (Daehan Biolink Co. Ltd, Chungbuk, Korea). Briefly, cortex was removed and incubated for 15 min in HBSS containing 2 mg/ml trypsin. Cells were then dissociated by trituration and plated (1 × 106 cells/ml) into poly-l-lysine-coated plastic culture dishes containing Neurobasal Medium supplemented with 2% B27, 0.5 mm l-glutamine, and 25 μm glutamate. Following cell attachment (24 h post-plating), the culture medium was replaced with Neurobasal Medium without glutamate. Experiments were performed using 7–9-day-old cultures.

MTT Assay

Cell proliferation was measured using an MTT assay. Briefly, cells (1 × 104 cells/ml) were seeded in 96-well plates, and after 24 h, treated with different concentrations of resveratrol (0.1∼50 μm). After treatment, media was removed, cells were washed twice with PBS, and 200 μl of a 0.5 mg/ml MTT solution in PBS was added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h, MTT solution was removed, and cells were lysed using a solubilization solution (1:1 DMSO:ethanol). The formazan dye product was quantified using an ELISA microplate reader at an absorbance of 560 nm. To examine the protective effect of the AMPK inhibitor (Compound C), cells were pretreated with Compound C 1 h before being treated with resveratrol.

BrdU Immunocytochemistry

Cells were labeled by adding BrdU to culture medium to a final concentration of 20 μm at 37 °C for 2 h, washed with BrdU-free culture medium, and treated with either vehicle or resveratrol. Twenty-four hours later, cells were fixed in PBS (pH 7.3) containing 4% paraformaldehyde, and washed with PBS. For immunostaining, fixed cells were postfixed in 70% ethanol (in 50 mm glycine buffer, pH 2.0) at −20 °C for 20 min, and then 0.6% H2O2 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.5) was added to block endogenous peroxidase activity. DNA was denatured by sequentially exposing cells to heat (65 °C), acid (2 m HCl), and base (0.1 m borate buffer). Primary BrdU antibody was then added, and plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Cells were then washed with TBS, incubated for 2 h with biotinylated secondary antibody, and treated with ABC solution (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. Color development was performed using a DAB kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were visualized and images were acquired using a Nikon ECLIPSE TE 2000-U microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc. Tokyo, Japan).

Nuclear Staining with Hoechst 33342 and PI

The plasma membrane of all cells is permeable to the DNA-binding dye Hoechst 33342; this dye it emits blue fluorescence thus allowing the visualization of nuclear DNA. However, the polar nuclear stain propidium iodide (PI) can only penetrate cells with damaged membranes. NPCs were seeded in a 60-mm culture dish and allowed to attach for 24 h. The cells were incubated in the presence or absence of resveratrol for 24 h, and Hoechst 33342 and PI were added for 10 min at final concentrations of 10 μm and 50 μm, respectively. Images were acquired using a Nikon ECLIPSE TE 2000-U microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc. Tokyo, Japan).

Flow Cytometric Analysis

FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences) was used to detect the cell death. In brief, after treatment with vehicle or resveratrol, cells were trypsinized and resuspended in binding buffer (0.1 m HEPES/NaOH pH 7.4, 1.4 m NaCl, and 25 mm CaCl2). 5 μl of Annexin V-FITC and 5 μl of PI were added and incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells were analyzed using flow cytometry (BD AccuriTM C6, BD Biosciences).

Western Blot Analysis

After experimental treatments, cells and tissue homogenates were solubilized in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer and protein concentrations in samples were determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Samples (50 μg protein per lane) were then separated in SDS- polyacrylamide gels and transferred electrophoretically to Immobilon-PSQ transfer membranes (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). Membranes were then placed immediately into a blocking solution (5% nonfat milk) at room temperature for 30 min, and incubated with the following diluted primary antibodies; p-ERK, p-JNK, and p-p38 (mouse, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), β-actin (mouse, Sigma), ERK, JNK, p38, p-AMPKα, AMPKα, and SIRT1 (rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology) in TBS-T buffer (Tris-HCl-based buffer containing 0.2% Tween 20, pH 7.5) overnight at 4 °C. After washing membranes (4 × 10 min), they were incubated with secondary antibody (monoclonal anti-mouse antibody or polyclonal anti-rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology)) in TBS-T buffer at room temperature for 1 h. Horseradish-conjugated secondary antibody labeling was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence and blots were exposed to radiographic film. Pre-stained blue markers were used to determine molecular weights.

In Vivo Drug Administration

Male C57BL/6 mice (4 weeks old) were obtained from Daehan Biolink Co. Ltd. (Chungbuk, Korea) and maintained under temperature- and light-controlled conditions (20–23 °C, 12 h light/12 h dark cycle) with food and water provided ad libitum. Mice were divided randomly into four groups (proliferation group, survival group, biochemical analysis group, behavior group) containing five animals per group. The mice were acclimatized for 1 week prior to intraperitoneal (intraperitoneal) injection of resveratrol at 1 or 10 mg/kg daily for 14 days. Mice in the vehicle group were administered same volume of PBS containing 2% ethanol and 0.1% Tween 20. To evaluate new cell generation, mice in each group were administered six intraperitoneal injections of BrdU (100 mg/kg twice daily for 3 days) on the last 3 days of resveratrol administration, and to evaluate new cell survival, mice were administered BrdU for three consecutive days prior to resveratrol administration. Mice were euthanatized 1 day after the final BrdU injection (day 15). The institutional animal care committee of Pusan National University approved the experimental protocol (#PNU-2008-06).

Tissue Preparation

For biochemical analyses, hippocampi were removed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C until required for analysis. The tissues were homogenized in a buffer (50 mm Tris buffer, pH 8.0) containing 6 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 10% sucrose, 1% SDS, and protease inhibitor mixture (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). For histological analyses, mice were anesthetized and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 m PBS (pH 7.4). After fixative perfusion, brains were removed, placed in the same fixative at 4 °C overnight, and transferred to a 30% sucrose solution. Cryoprotected brains were sectioned serially at 40-μm in the coronal plane using a freezing microtome (MICROM, Germany). All sections that included the hippocampus were collected in Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS) solution containing 0.1% sodium azide and stored at 4 °C. Sections containing the hippocampal formation were saved.

Immunohistochemistry

Staining for newly generated cells in the dentate gyrus, was performed by treating them with 0.6% H2O2 in TBS (pH 7.5) to block endogenous peroxidases, and denaturing DNA by exposing them sequentially to heat (65 °C), acid (2 N HCl), and base (0.1 m borate buffer). Sections were then blocked in TBS/0.1% Triton X-100/3% goat serum (TBS-TS) for 30 min and incubated with primary anti-BrdU antibody (rat, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or anti-pCREB antibody (rabbit, Cell Signaling) in TBS-TS overnight at 4 °C. The sections were incubated with a biotinylated secondary goat anti-rat or rabbit IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories) for 3 h at room temperature, and then with ABC solution (Vectastain ABC reagent Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories) for 1 h at room temperature. They were then treated with diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution for 5 min, and imaged under a Nikon ECLIPSE TE 2000-U microscope. Cells in every sixth section throughout the entire rostro-caudal region of the hippocampus were counted. The reference region consisted of the granular cell layer of the dentate gyrus. All cell counts were performed by an investigator (HRP) blinded as to the treatment history of the mice.

Double-label Immunohistochemistry

For double-label immunohistochemistry, brain sections were blocked with TBS/0.1% Triton X-100/3% goat serum (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and incubated with primary antibodies against BrdU or the neuronal marker NeuN (mouse monoclonal; 1:500, Millipore) overnight at 4 °C. They were then washed with TBS and incubated for 3 h in presence of anti-mouse IgG labeled with Alexa Fluor-568 or anti-rat IgG labeled with Alexa Fluor-488. Images were acquired using a FV10i FLUOVIEW Confocal Microscope (Olympus, Tokyo).

BDNF ELISA

BDNF protein levels were quantified using a commercially available kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, hippocampus homogenates or cell lysates were processed by acidification and subsequent neutralization. Flat-bottom 96-well plates (Nunc-ImmunoTM Maxisorp Plates, Roskilde, Denmark) were pre-coated with monoclonal BDNF antibody, blocked with block & sample buffer, and washed in TBS/0.05% Tween 20 (TBST). Recombinant BDNF standard (0–500 pg/ml) and test samples were added to duplicate wells in each plate. Plates were incubated for 2 h, washed five times with TBST, and incubated in a solution containing with anti-Human BDNF polyclonal antibody for 2 h. Wells were washed five times with TBST and incubated with anti-IgY HRP conjugate for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were then emptied, washed five times with TBST, TMB One Solution was added and incubated at room temperature with shaking for 10 min, and the reaction was stopped with 1 N HCl. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a plate reader. Duplicate determinations per sample were averaged, and levels of BDNF protein were determined using the standard curve.

Morris Water Maze (MWM) Behavior Test

The MWM procedure was performed as described (28). The spatial reference memory test is commonly used to examine impairments of spatial learning and memory, and requires mice to find a hidden platform (10 cm in diameter) just below the surface (1 cm) of a circular pool of opaque water (120 cm in diameter × 35 cm high, maintained at 23∼25 °C). Accurate navigation to the platform is rewarded by escape from the water. The maze was placed in a room with dimmed lights, and visible cues were placed on walls adjacent to the pool to aid the mice in determining the location of the platform. Mice were given 4 consecutive days of training (6 trials/day) after vehicle or resveratrol treatment for 14 days. At the beginning of each trial, mice were immersed in the water, facing the wall, at one of three randomly assigned start positions (located in the center of each quadrant not containing the platform). Mice were allowed 60 s to find the platform; if mice failed to find the platform even after 60 s, they were guided to the platform by the investigator. Once a mouse reached the platform, it was allowed to remain there for 10 s. At the end of each trial, mice were towel-dried and returned to their home cages for ∼15–20 min before being returned to the maze for the next trial. During each trial the mouse was videotaped and its swim path was recorded with image tracking software, which allowed determination of the time taken (latency) to find the platform (s), the path length (cm), and the swimming speed (cm/s), and to obtain information during spatial reference memory test (trials conducted after the above-mentioned trials with the platform removed), namely, the number of platform location crossings and the time spent in the quadrant which previously contained the platform (Noldus EthoVision® XT, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significances of differences between the vehicle and resveratrol-treated groups were determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD) procedure. The analysis was performed using Statview software®. Results are expressed as means ± S.E., and p values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Resveratrol Decreases NPCs Proliferation

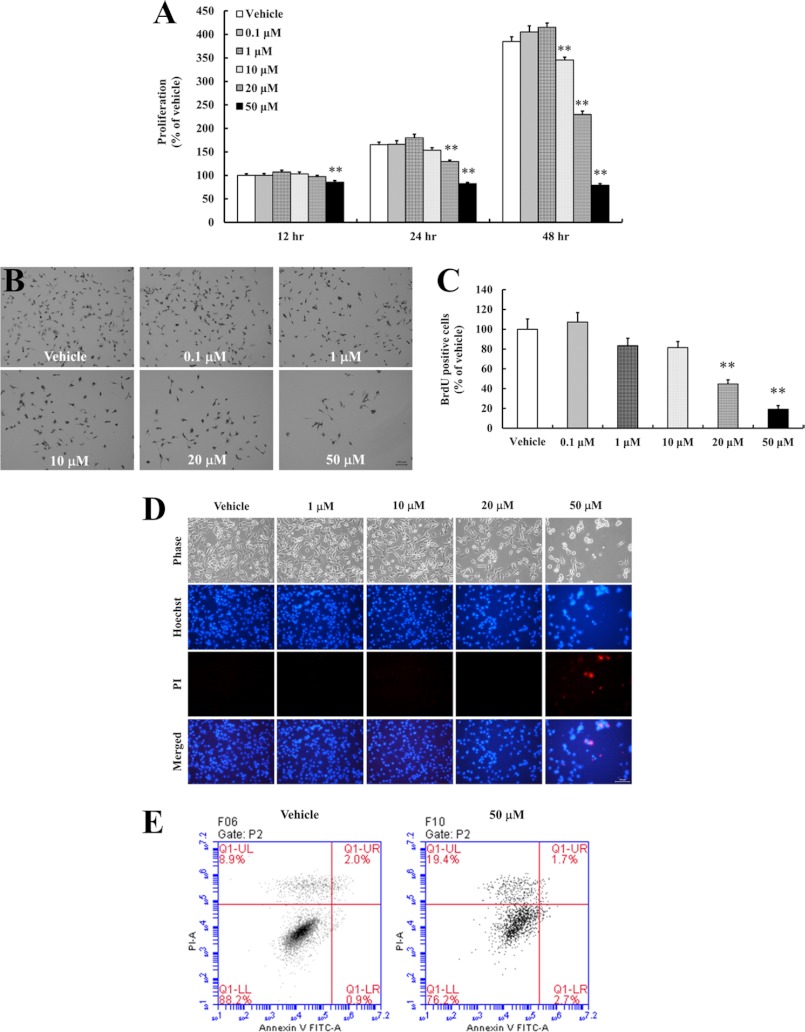

We first performed a concentration-response experiment to determine whether resveratrol modifies the proliferation of C17.2 NPCs. Resveratrol concentrations of up to 10 μm had no significant effect on NPCs proliferation. However, higher concentrations (20 and 50 μm) significantly reduced cell proliferation (Fig. 1A). BrdU immunocytochemistry was performed to confirm the inhibitory effects of these concentrations on NPCs proliferation (Fig. 1B). Quantification of BrdU-positive cells showed a significant decrease in NPCs proliferation in response to 20 and 50 μm (Fig. 1C). To evaluate whether resveratrol induced the cell death in NPCs, we performed PI/Hoechst 33342 staining and flow cytometric analysis. Treatment of NPCs with 20 and 50 μm resveratrol clearly decreased the cell number. However, some of the cells in cultures treated with 50 μm resveratrol were stained with PI, indicating that resveratrol can induce necrotic cell death in NPCs (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, we confirmed resveratrol-induced necrotic cell death by flow cytometry analysis with PI and Annexin V (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 1.

Resveratrol decreases the cell proliferation and induces necrotic cell death of C17.2 NPCs. NPCs were seeded into 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/ml) and cultured for 24 h. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of resveratrol for 12, 24, or 48 h. A, NPCs proliferation was determined using an MTT assay. The higher concentrations of resveratrol inhibited NPCs proliferation. Values are the mean ± S.E. (n = 8). B and C, BrdU immunoreactive cells were counted and values are the mean ± SEs (n = 4). **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure). D, NPCs were exposed to resveratrol (1, 10, 20, and 50 μm) for 24 h and 10 or 50 μm of Hoechst 33342 and PI were added for 10 min. The Hoechst 33342- and PI-stained cells are bright blue and red, respectively. Scale bar = 100 μm. E, flow cytometry analysis with PI and Annexin V staining showed that 50 μm resveratrol increased PI-positive intensity indicating necrotic cell death in the NPCs.

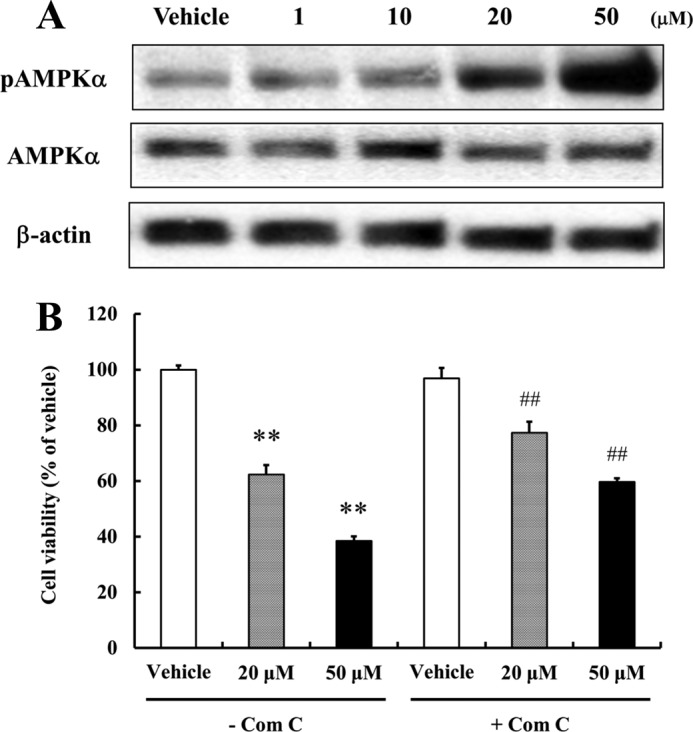

Resveratrol Impairs NPCs Proliferation by Activating AMPK

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway is known to be involved in the regulation of NPCs proliferation and stress responses (29, 30). Recently, it was reported that curcumin modulates extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) and p38 MAP kinase to stimulate NPCs proliferation (30), and we therefore examined how resveratrol modulates the proliferation-related MAPK signaling pathway, as well as the energy metabolism-responsive SIRT1 deacetylase and AMP-activated protein kinase α (AMPKα). We found that resveratrol did not activate MAPK signaling or SIRT1 in NPCs (data not shown). However, resveratrol did increase phosphorylated AMPKα levels significantly at high concentrations (20 and 50 μm) (Fig. 2A), which concurs with a previous report that resveratrol at 50 μm activates AMPKα in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and in C2C12 myotubes (31, 32). Furthermore, compound C (an AMPK inhibitor) effectively, albeit incompletely, restored NPCs proliferation (Fig. 2B). There was no significant difference in cell viability between the absence and presence of compound C in vehicle-treated group. These observations indicate that AMPK activation is partially mediated by the suppression of NPCs proliferation induced by resveratrol.

FIGURE 2.

AMPK activation suppresses NPCs proliferation. A, NPCs treated with resveratrol for 1 h were subjected to Western blotting for AMPK. Resveratrol did activate AMPK (Thr-172). β-Actin was used as loading controls. A representative blot from three independent experiments that yielded similar results is shown. B, to investigate reduced cell proliferation by resveratrol-mediated AMPK activation, NPCs were pretreated with Compound C (5 μm; an AMPK inhibitor) for 1 h. Cells were then incubated for 24 h with or without the indicated concentrations of resveratrol, and MTT assays were performed. Compound C effectively blocked the reduction of cell proliferation by resveratrol. Values are mean ± S.E. (n = 8). **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle in the absence of inhibitor, ##, p < 0.01 versus each treatment in the absence of inhibitor (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure).

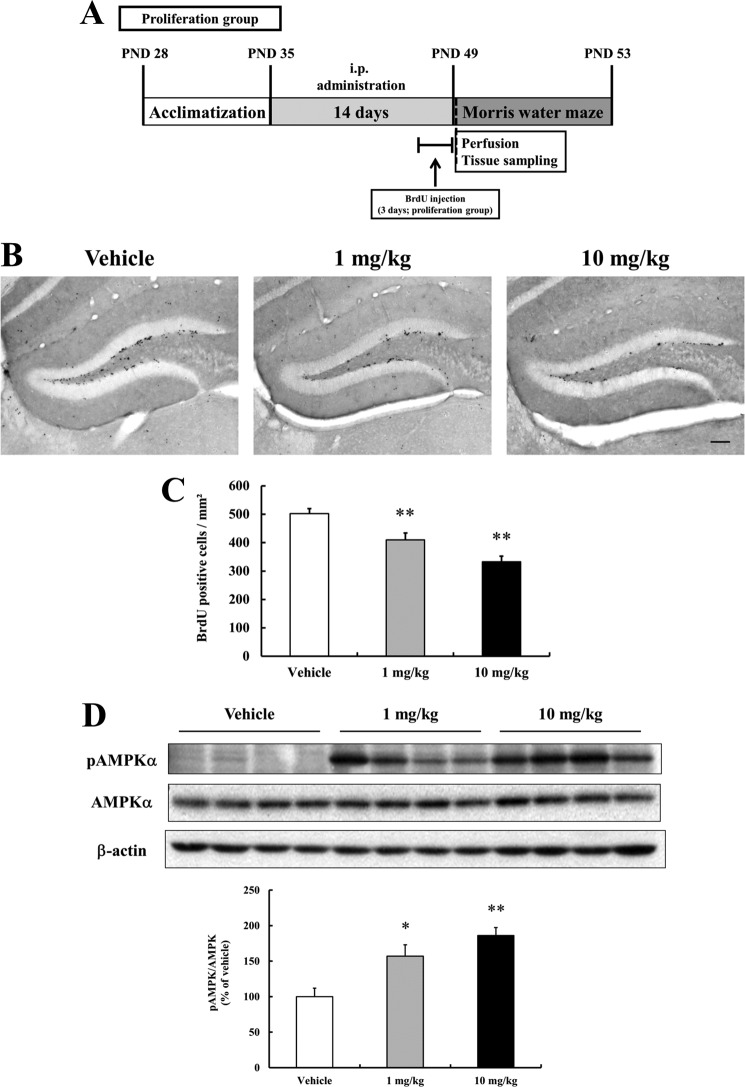

Resveratrol Decreases the Proliferation of Newly Generated Cells in the Hippocampal Dentate Gyrus

To determine the effect of resveratrol on NPCs residing in the dentate gyrus, 5-week-old C57BL/6 mice were administered either resveratrol (1 or 10 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) or vehicle for 14 days. Body weights were measured every 3 days. Both groups gained body weight normally and no significant intergroup difference was observed (data not shown). For labeling newly generated cells in the hippocampus, six doses of BrdU were administered intraperitoneal for 3 days starting on the 12th day of resveratrol administration (Fig. 3A). Dividing cells labeled with BrdU were visualized by BrdU immunohistochemistry (see “Experimental Procedures”). In the vehicle-treated mice, newly generated cells were observed in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus. However, numbers of newly generated cells were significantly lower in the resveratrol-treated mice compared with the vehicle treated mice, with the 10 mg/kg dose causing a greater reduction in BrdU-labeled cells than the 1 mg/kg dose (Fig. 3, B and C). In addition, resveratrol significantly increased the protein level of phosphorylated AMPKα in the hippocampus (Fig. 3D). As was indicated by our cell culture experiments, this result suggests that the resveratrol-induced inhibition of NPCs proliferation in the hippocampus is mediated by AMPK activation. Since hippocampal neurogenesis can be affected by neuronal damage-mediated neuroinflammation (33), we evaluated glial activation in resveratrol-treated mice. Double-label fluorescence immunohistochemistry was performed on hippocampal sections using antibodies against the astrocyte marker (GFAP) or endogenous microglia marker (Iba-1). However, glial activation was not observed in the hippocampus of resveratrol-treated mice, and Nissl staining showed that resveratrol did not affect neuronal density, nor cause any discernible damage to neurons (data not shown). Therefore, these findings show that resveratrol inhibits cell proliferation in the hippocampus without activating glial cells or causing neuronal damage.

FIGURE 3.

Resveratrol decreases the proliferation of newly generated cells in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Mice treated with vehicle or resveratrol for 14 days were administered BrdU on days 12–14 of resveratrol administration. The mice were euthanized on day 15 and brain tissue sections were processed for BrdU immunostaining. A, schematic overview of the in vivo experimental procedure. C57BL/6 mice (5-week-old) were intraperitoneal administered vehicle or resveratrol was administered for 14 days. BrdU pulses were given the last 3 days of vehicle or resveratrol treatment. B, representative images showing BrdU-positive cells in the dentate gyrus. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, analysis of numbers of BrdU-positive cells in the dentate gyrus. Representative hippocampal sections (8–10) were chosen and immunostained with BrdU-specific antibodies. The analysis showed fewer newly generated cells in the dentate gyrus of animals treated with resveratrol. Values are as the mean ± S.E. (n = 5 mice/group). **, p < 0.01 versus the vehicle (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure). D, mice were administered either vehicle or resveratrol for 14 days. Mice were then euthanized and hippocampal tissue lysates were prepared. Tissue extracts were subjected to Western blotting for phosphorylated AMPKα (Thr-172), AMPKα, and β-actin. Resveratrol was found to activate AMPKα in the hippocampus. β-Actin was used as a protein loading control. A representative blot from three independent experiments that yielded similar results is shown.

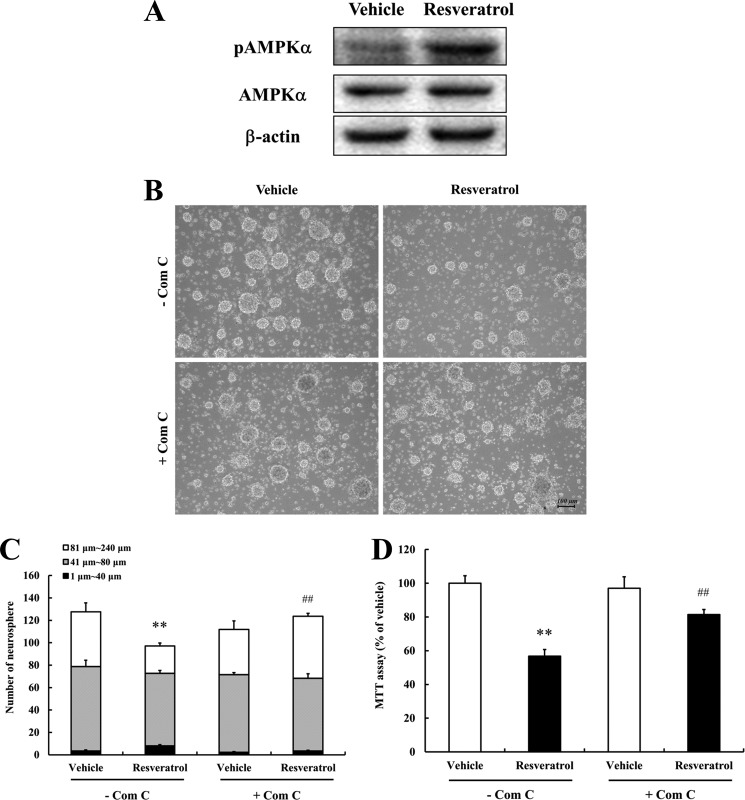

Resveratrol Decreases Proliferation of Primary Embryonic Cerebral Cortical NPCs

To confirm that resveratrol can act directly on NPCs to inhibit their proliferation, we established primary NPCs from the cerebral neuroepithelium of embryonic day 13 mice. AMPK activation by resveratrol was also observed in these primary cultured NPCs (Fig. 4A). To verify the anti-proliferative effect of resveratrol, primary NPC neurospheres were treated with 50 μm resveratrol for 24 h, and numbers and sizes of neurospheres were measured. Resveratrol treatment resulted in a reduction in the numbers of large neurospheres (especially those larger than 81 μm) and cell proliferation (Fig. 4, B–D). Furthermore, the AMPK inhibitor (compound C) significantly attenuated the negative effect of resveratrol on NPCs proliferation and neurosphere size (Fig. 4, C and D). These results indicate that AMPK signaling participates in the anti-proliferative effect of resveratrol on primary NPCs.

FIGURE 4.

Resveratrol decreases the proliferation of embryonic cerebral cortical NPCs. Dissociated embryonic NPCs were seeded into 24-well plates and cultured for 2 days. Neurospheres were pretreated with Compound C (5 μm) for 1 h and grown in either vehicle- or resveratrol-containing medium for 24 h. A, whole cell extracts from cells treated with 50 μm of resveratrol for 1 h were subjected to Western blotting for phosphorylated AMPKα (Thr-172), AMPKα, and β-actin. Resveratrol was found to activate AMPKα in NPCs. β-Actin was used as the protein loading control. A representative blot from three independent experiments that yielded similar results is shown. B, images of neurospheres were taken after treatment with vehicle or resveratrol for 24 h. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, neurospheres were counted and their sizes (diameters) measured. Values are the mean ± S.E. (n = 4). **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle in the absence of inhibitor, ##, p < 0.01 versus each treatment in the absence of inhibitor (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure). D, proliferation of primary NPCs was quantified using an MTT assay. Values are mean ± S.E. (n = 8). **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle in the absence of inhibitor, ##, p < 0.01 versus each treatment in the absence of inhibitor (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure).

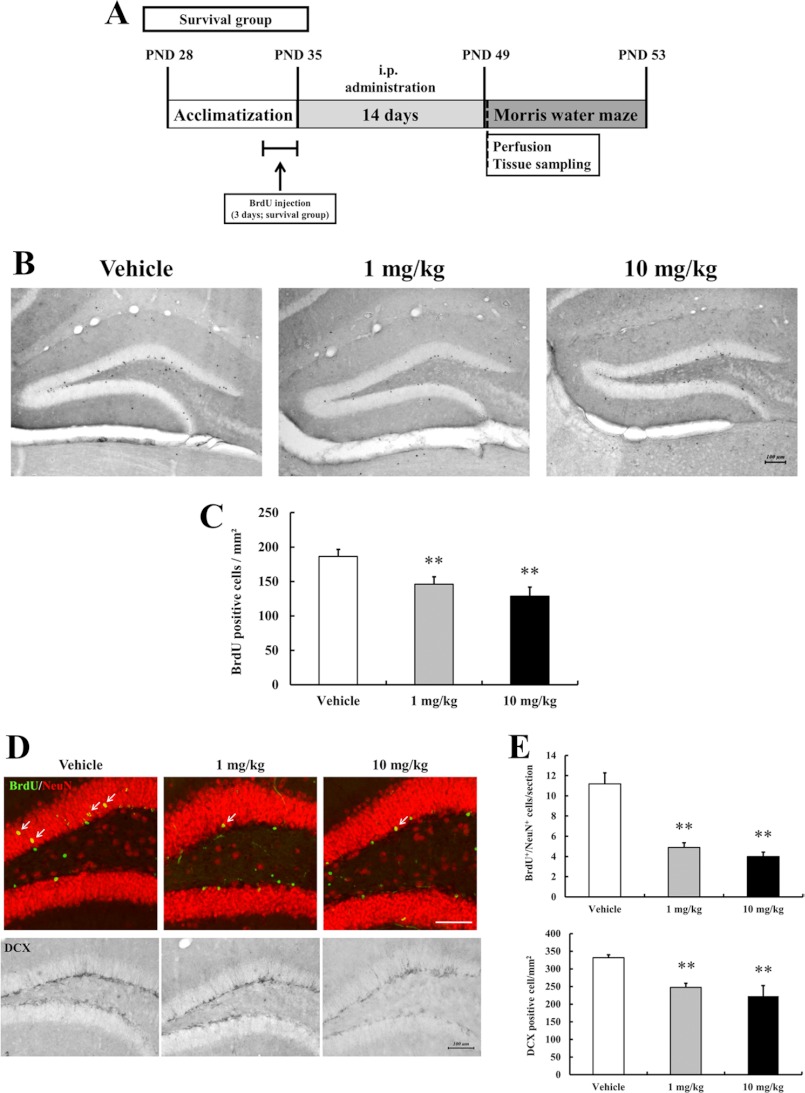

Resveratrol Reduces the Survival of Newly Generated Hippocampal Cells and Impairs Neurogenesis

It was previously reported that DR (alternate day fasting) enhances the survival of newly generated cells in the adult dentate gyrus of mice, without affecting proliferation of NPCs (22). Because resveratrol inhibited the proliferation of cultured NPCs, we next asked whether resveratrol might, nevertheless, mimic the effects of DR on neurogenesis in vivo. In the present study, BrdU was administered intraperitoneal for 3 days before resveratrol administration (Fig. 5A), and cells that were dividing during this 3 day period were visualized in brain sections immunostained with a BrdU antibody (see “Experimental Procedures”). Most surviving cells had migrated into the granule cell layer (GCL) of the dentate gyrus. Compared with vehicle-treated mice, the numbers of surviving cells in the dentate gyrus were significantly lower mice treated with either 1 or 10 mg/kg of resveratrol (Fig. 5, B and C). Next, we examined the effects of resveratrol on the differentiation of NPCs into neurons by immunostaining brain sections with antibodies against NeuN, a marker of mature neurons, or doublecortin (DCX) which is expressed in immature neurons. Compared with vehicle-treated mice, resveratrol-treated mice showed significantly fewer NeuN/BrdU double-positive cells and DCX-positive cells in the dentate gyrus (Fig. 5, D and E). These results suggest that resveratrol adversely affects the differentiation and survival of newly generated cells in the hippocampi of young mice, which contrasts with the neurogenic effects of DR.

FIGURE 5.

Resveratrol impairs hippocampal neurogenesis. A, schematic overview of the in vivo experimental procedure. C57BL/6 mice (5-week-old) were intraperitoneal administered vehicle or resveratrol was administered for 14 days. BrdU pulses were given the 3 days before vehicle or resveratrol treatment. B, representative images showing BrdU-positive cells in the dentate gyrus. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, numbers of BrdU-positive cells in the dentate gyrus. Representative hippocampal sections (8–10) were chosen and immunostained with BrdU-specific antibodies. The analysis showed fewer newly generated cells in the dentate gyrus in animals treated with resveratrol. Values are mean ± S.E. (n = 5 mice/group). **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure). D, to determine the effect of resveratrol on hippocampal neurogenesis, double-labeling immunohistochemistry was performed with primary antibodies against BrdU (green) and mature neuron marker (NeuN; red). Hippocampal sections were immunostained with doublecortin (DCX, immature neuron marker) antibody. Resveratrol impaired neuronal differentiation and hippocampal neurogenesis. Scale bar = 100 μm. E, quantitative analysis of BrdU+/NeuN+-positive cell numbers and DCX-positive cell numbers in the dentate gyrus. **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure).

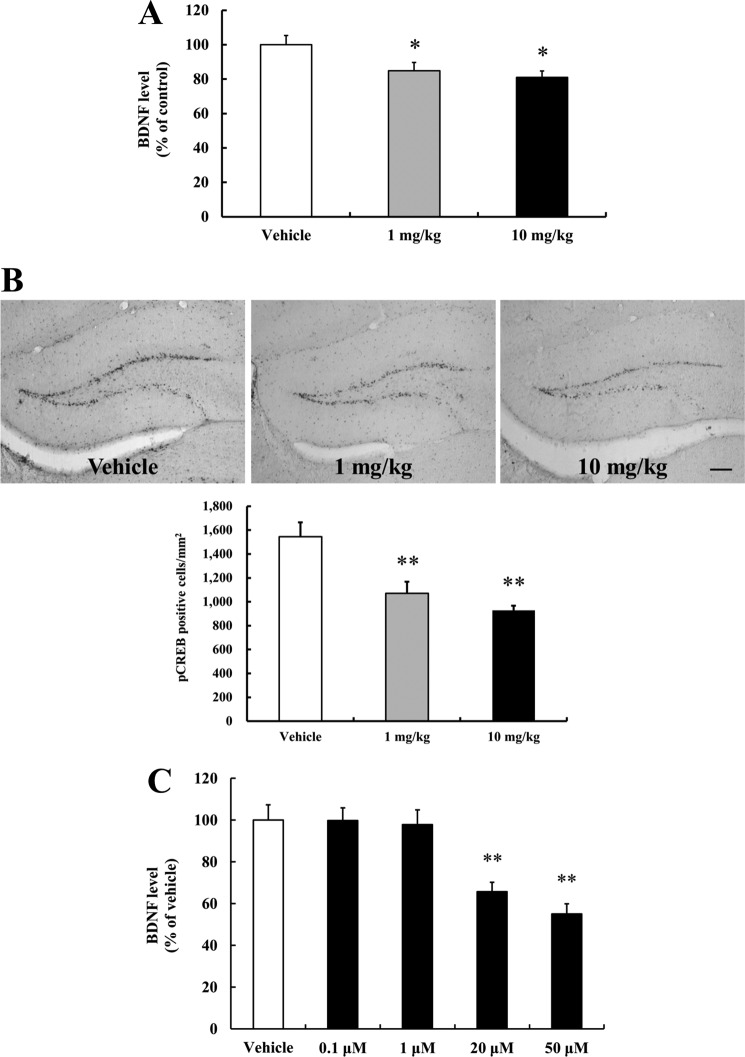

Hippocampal BDNF and pCREB Levels Are Reduced in Resveratrol-treated mice

BDNF is known to play an important role in the regulation of hippocampal neurogenesis, and may mediate the neurogenic effects of DR, exercise and enriched environments (22, 23, 34). BDNF expression is up-regulated by the transcription factor cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) (35). Therefore, we examined hippocampal BDNF and phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) levels to elucidate the mechanism by which resveratrol suppresses hippocampal neurogenesis. Administration of resveratrol for 14 days significantly decreased levels of BDNF and of pCREB in the hippocampus (Fig. 6, A and B). Interestingly, pCREB immunostaining was relatively intense in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus where neurogenesis occurs, consistent with the possibility that this transcription factor is highly activated in differentiated NPCs in that region (Fig. 6B). Because BDNF is produced primarily by neurons, our findings suggest that resveratrol inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis, in part, by reducing BDNF levels. Consistent with the latter possibility, we found that resveratrol significantly decreased the production of BDNF in primary cultured neurons (Fig. 6C). These findings suggest that resveratrol inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis by reducing BDNF production in neurons and by reducing pCREB signaling in differentiated NPCs.

FIGURE 6.

Resveratrol decreases levels of BDNF and pCREB. A, levels of BDNF protein in tissue homogenates of hippocampi from vehicle or resveratrol-treated mice were measured using a quantitative ELISA assay. Resveratrol decreased BDNF protein levels in the hippocampus. Values are mean ± S.E. (n = 5 mice/group). *, p < 0.05 versus vehicle (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure). B, reductions in the levels of pCREB (Ser-133) in the dentate gyrus of vehicle and resveratrol-treated mice were evaluated by immunohistochemistry using pCREB antibody. Scale bar, 100 μm. Quantitative analysis of pCREB-positive cell numbers in the dentate gyrus. **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure). C, resveratrol decreased BDNF levels in primary cortical neurons. To measure BDNF levels in primary cortical neurons, BDNF ELISA was carried out in primary cortical neuron lysates. Values are means ± S.E. (n = 8).

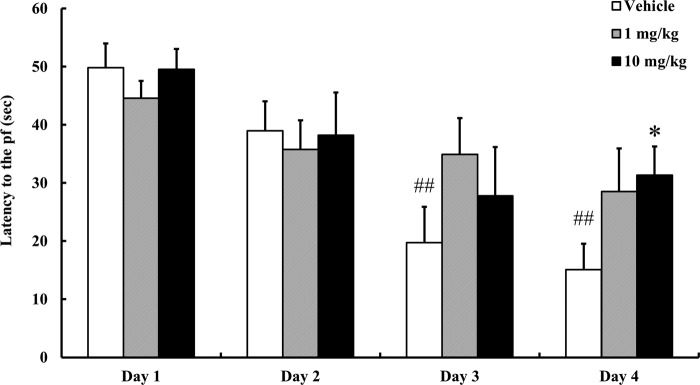

Resveratrol Impairs Hippocampus-dependent Learning and Memory

Because neurogenesis is associated with, and may mediate aspects of, hippocampus-dependent learning and memory, we determined whether resveratrol treatment affected spatial learning. We first trained vehicle-treated mice and resveratrol-treated mice to find the hidden platform in the MWM, a hippocampus-dependent visuo-spatial learning and memory test. The mice in the vehicle group learned the location of the platform more quickly during the 4 day testing period, compared with mice treated with either 1 or 10 mg/kg resveratrol (Fig. 7). There was no significant difference in the magnitude of the learning and memory impairment between the two doses of resveratrol. During the spatial reference memory test, swim speed, and total distance were no different in the resveratrol and vehicle groups (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Resveratrol impairs spatial learning and memory. Morris water maze hidden platform tests were performed to evaluate spatial learning and memory. Goal latency time was analyzed in mice treated with each group (6 trials/day). Values are mean ± S.E. (n = 5 mice/group). *, p < 0.05 versus vehicle on day 4. ##, p < 0.01 versus vehicle on day 1 (ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD procedure).

DISCUSSION

The discovery of an elixir of life has long been an interest/dream of both the general public and the scientific community. Resveratrol has been touted as a dietary supplement that can protect against a range of diseases including cancers, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative disorders (36, 37). There are more than 4800 publications in the scientific literature that describe effects of resveratrol on biological systems which, when considered en toto, reveal that this chemical exhibits a wide range of activities that depend upon many factors including the dose of resveratrol, the cell type, the organism being studied, and the physiological or pathological state of the organism (10). Here we extend this literature by showing that resveratrol can have a negative impact on the proliferation, survival, and differentiation of NPCs. Our in vivo studies show that suppression of hippocampal neurogenesis by resveratrol is associated with impaired spatial memory acquisition in a water maze test that is known to be hippocampus-dependent. The doses of resveratrol that inhibit hippocampal neurogenesis (1–10 mg/kg body weight) are within the range of concentrations that have been previously reported to improve energy metabolism (e.g. insulin sensitivity) (32), and counteract disease processes in animal models of cancers (38), cardiovascular disease (39), and some neurodegenerative conditions (40). It was also recently reported that resveratrol can promote the survival of hippocampal NPCs in an animal model of neuroinflammation (41). While resveratrol may protect neurons against oxidative and inflammatory stress, our findings suggest that in healthy mice NPCs are adversely affected by resveratrol. Our findings are consistent with evidence that resveratrol can inhibit the proliferation of embryonic cardiac stem cells (42).

Resveratrol has been shown to activate two molecular targets implicated in the health benefits of dietary energy restriction, namely, SIRT1 and AMPK (43). However, if and how resveratrol may activate SIRT1 is still the subject of debate because recent findings suggest that resveratrol does not directly interact with SIRT1 (44–47). Nevertheless, it has been proposed that resveratrol mimics the effects of caloric restriction on energy metabolism and disease resistance. We found that resveratrol treatment does not mimic the effects of DR on hippocampal neurogenesis. Indeed, whereas DR enhances neurogenesis (22–24), resveratrol inhibits neurogenesis. Our data further show that resveratrol activates AMPK, but does not activate SIRT1, in NPCs. We therefore subsequently focused on the role of AMPK activation by resveratrol in NPCs.

AMPK is activated by upstream kinases, such as LKB1 and CaMKKβ, and can be modulated by intracellular redox balance (48). AMPK activation might have protective effects in the brain under the metabolic stress or neurodegenerative disease, and exerts an anti-proliferative effect in cancers (49–51). In experimental models, resveratrol can prevent inflammation, cancer, and neurodegenerative disease, and can extend lifespan (1, 3, 9, 31). AMPK activation is important for the enhancement of insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial biogenesis by resveratrol in high fat diet-fed mice and high calorie diet-induced obesity (31, 52). However, we found that in three different populations of NPCs (C17.2 NPCs, primary mouse cerebral cortical NPCs and adult hippocampal progenitors in vivo) resveratrol increases the levels of phosphorylated (active) AMPKα and inhibits NPCs proliferation. Moreover, we found that treatment of NPCs with an inhibitor of AMPK (Compound C) significantly attenuated the suppressive effects of resveratrol on NPCs proliferation. These results indicate that the activation of AMPK negatively regulates NPCs proliferation. Previous studies have shown that the activation of AMPK does not always have beneficial effects in tissues or cells. For example, AMPK activation mediates the inhibition of cell growth in mouse embryonic fibroblasts under conditions of reduced energy availability (49). Furthermore, the AMPK activator AICAR reduces the proliferation of NPCs and cancer cells (50, 53–56). We therefore suggest that, with regards to NPCs, resveratrol-induced AMPK activation can have beneficial effects in a background of a metabolic disorder or disease state, but may adversely affect these cells under normal conditions. Previously, it has been reported that resveratrol effectively protect neurons against oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, and resveratrol at 25 μm and 60 μm concentration has no significant effect on the cell viability of rat hippocampal/cortical neurons (57, 58). Therefore, we believe that resveratrol-induced AMPK activation could affect mainly the proliferating cells including cancer cells and NPCs, but post-mitotic neurons which are not proliferating might be more resistant to resveratrol-induced AMPK activation. Taken together, the effects of resveratrol in the present study are likely to be NPC-specific. Our findings in NPCs further suggest that it will be important to evaluate the effects of resveratrol on stem cell populations in other tissues.

Adult NPCs are continuously generated in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus and in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricle in the adult brain. Neurogenesis is reduced during aging (59), and increased in response to physical exercise (60), an enriched environment (61), and DR (22–24). Neurogenesis is positively correlated with cognitive function, and some findings suggest that neurogenesis is required for some types of hippocampus-dependent learning and memory (62). We found that mice treated with resveratrol performed more poorly in a water maze test of hippocampus-dependent learning and memory compared with vehicle-treated mice. We administrated resveratrol for 14 days at doses (1 or 10 mg/kg) that should, based on previous studies (48), result in the presence of resveratrol within the brain. Our cell culture data demonstrate that resveratrol can act directly on NPCs to inhibit their proliferation, consistent with the possibility that resveratrol crosses the blood-brain barrier and acts directly on the hippocampal NPCs in vivo. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of an indirect effect of resveratrol on NPCs in vivo. Indeed, we found that resveratrol can suppress the production of BDNF by neurons, which may contribute to the inhibition of neurogenesis in vivo because BDNF is known to promote the differentiation and survival of hippocampal NPCs (63). The results of our immunostaining with a pCREB antibody suggest that resveratrol causes a reduction in CREB activity which could contribute to reduced neurogenesis because CREB induces the expression of BDNF (64, 65). Again, this contrasts with DR which up-regulates CREB (66).

Recent study reported that resveratrol inhibits the leucine-induced mTOR signaling pathway in the myoblasts and primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (67). We examined how resveratrol affects the mTOR signaling pathway, which is important for the cell growth, proliferation and protein synthesis. We found that resveratrol decreased the phosphorylation of mTOR (Ser-2448) and its downstream target, 4EBP1 (Thr-37/46) in the NPCs, which was associated with decreased proliferation of the NPCs (data not shown). Our findings are consistent with the results of a recent study showing that cannabinoid receptor agonists that activate mTOR enhance NPCs proliferation, whereas the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin suppresses NPCs proliferation (68). It is possible that resveratrol may regulate the mTOR signaling pathway in the NPCs and hippocampus, results that resveratrol-induced impairment of NPCs proliferation and hippocampal neurogenesis.

It was recently reported that stimulation of sensory neurons by resveratrol enhances angiogenesis and neurogenesis by increasing IGF-1 production (69). However, our study and this previous study differ in several aspects including the doses of resveratrol used, animal ages, and study duration. Harada et al. (69) administered 10–12-week-old male C57BL/6 mice 4 μg/day/mouse of resveratrol orally for 3 weeks, whereas we used 5-week-old male C57BL/6 mice, which exhibit active hippocampal neurogenesis (70). In the present study, the daily dosage of resveratrol was about 25 or 250 μg/day/mouse for 2 weeks, which are higher doses than the earlier study. This suggests that resveratrol has bi-phasic effects on the regulation of hippocampal neurogenesis depending on the doses. However, in the hope of delaying aging and neurodegeneration, people have shown increasing interest in beneficial effects of resveratrol and are taking resveratrol routinely without regulation. In fact, commercially available tablets contain up to 500 mg of resveratrol, which could result in the exposure of NPCs to concentrations similar to those used in the present study. Further research on the effects of resveratrol on NPCs and associated cognitive function is therefore warranted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. C. Cepko at Harvard University, Boston, MA for kindly donating the C17.2 cell line.

This work was supported, in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIA, National Institutes of Health. This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MEST) (Grant no. 2009-0083538). This research was also supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (No. A084225).

- NPC

- neural progenitor cell

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- BDNF

- brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- DR

- dietary energy restriction

- DCFDA

- dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- PI

- propidium iodide

- MWM

- Morris Water Maze

- GCL

- granule cell layer

- DCX

- doublecortin.

REFERENCES

- 1. de la Lastra C. A., Villegas I. (2005) Resveratrol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-aging agent: mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 49, 405–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim Y. A., Rhee S. H., Park K. Y., Choi Y. H. (2003) Antiproliferative effect of resveratrol in human prostate carcinoma cells. J. Med. Food 6, 273–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le Corre L., Chalabi N., Delort L., Bignon Y. J., Bernard-Gallon D. J. (2005) Resveratrol and breast cancer chemoprevention: molecular mechanisms. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 49, 462–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang H. M., Liang Y. C., Cheng T. H., Chen C. H., Juan S. H. (2005) Potential mechanism of blood vessel protection by resveratrol, a component of red wine. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1042, 349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kang O. H., Jang H. J., Chae H. S., Oh Y. C., Choi J. G., Lee Y. S., Kim J. H., Kim Y. C., Sohn D. H., Park H., Kwon D. Y. (2009) Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of resveratrol in activated HMC-1 cells: pivotal roles of NF-κB and MAPK. Pharmacol. Res. 59, 330–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oh Y. C., Kang O. H., Choi J. G., Chae H. S., Lee Y. S., Brice O. O., Jung H. J., Hong S. H., Lee Y. M., Kwon D. Y. (2009) Anti-inflammatory effect of resveratrol by inhibition of IL-8 production in LPS-induced THP-1 cells. Am. J. Chin. Med. 37, 1203–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Della-Morte D., Dave K. R., DeFazio R. A., Bao Y. C., Raval A. P., Perez-Pinzon M. A. (2009) Resveratrol pretreatment protects rat brain from cerebral ischemic damage via a sirtuin 1-uncoupling protein 2 pathway. Neuroscience 159, 993–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lu K. T., Ko M. C., Chen B. Y., Huang J. C., Hsieh C. W., Lee M. C., Chiou R. Y., Wung B. S., Peng C. H., Yang Y. L. (2008) Neuroprotective effects of resveratrol on MPTP-induced neuron loss mediated by free radical scavenging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 6910–6913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marambaud P., Zhao H., Davies P. (2005) Resveratrol promotes clearance of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-β peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37377–37382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Calabrese E. J., Mattson M. P., Calabrese V. (2010) Resveratrol commonly displays hormesis: occurrence and biomedical significance. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 29, 980–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao C., Deng W., Gage F. H. (2008) Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell 132, 645–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hirsch C., Campano L. M., Wöhrle S., Hecht A. (2007) Canonical Wnt signaling transiently stimulates proliferation and enhances neurogenesis in neonatal neural progenitor cultures. Exp. Cell Res. 313, 572–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park M., Song K. S., Kim H. K., Park Y. J., Kim H. S., Bae M. I., Lee J. (2009) 2-Deoxy-d-glucose protects neural progenitor cells against oxidative stress through the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Neurosci. Lett. 449, 201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shimojo H., Ohtsuka T., Kageyama R. (2008) Oscillations in notch signaling regulate maintenance of neural progenitors. Neuron 58, 52–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Takahashi T., Nowakowski R. S., Caviness V. S., Jr. (1995) The cell cycle of the pseudostratified ventricular epithelium of the embryonic murine cerebral wall. J. Neurosci. 15, 6046–6057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anderson M. F., Aberg M. A., Nilsson M., Eriksson P. S. (2002) Insulin-like growth factor-I and neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 134, 115–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cao L., Jiao X., Zuzga D. S., Liu Y., Fong D. M., Young D., During M. J. (2004) VEGF links hippocampal activity with neurogenesis, learning and memory. Nat. Genet. 36, 827–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deng W., Aimone J. B., Gage F. H. (2010) New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 339–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barger J. L., Kayo T., Vann J. M., Arias E. B., Wang J., Hacker T. A., Wang Y., Raederstorff D., Morrow J. D., Leeuwenburgh C., Allison D. B., Saupe K. W., Cartee G. D., Weindruch R., Prolla T. A. (2008) A low dose of dietary resveratrol partially mimics caloric restriction and retards aging parameters in mice. PLoS One 3, e2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Howitz K. T., Bitterman K. J., Cohen H. Y., Lamming D. W., Lavu S., Wood J. G., Zipkin R. E., Chung P., Kisielewski A., Zhang L. L., Scherer B., Sinclair D. A. (2003) Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature 425, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Valenzano D. R., Terzibasi E., Genade T., Cattaneo A., Domenici L., Cellerino A. (2006) Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and retards the onset of age-related markers in a short-lived vertebrate. Curr. Biol. 16, 296–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee J., Duan W., Long J. M., Ingram D. K., Mattson M. P. (2000) Dietary restriction increases the number of newly generated neural cells, and induces BDNF expression, in the dentate gyrus of rats. J. Mol. Neurosci. 15, 99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee J., Duan W., Mattson M. P. (2002) Evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for basal neurogenesis and mediates, in part, the enhancement of neurogenesis by dietary restriction in the hippocampus of adult mice. J. Neurochem. 82, 1367–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee J., Seroogy K. B., Mattson M. P. (2002) Dietary restriction enhances neurotrophin expression and neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adult mice. J. Neurochem. 80, 539–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Snyder E. Y., Deitcher D. L., Walsh C., Arnold-Aldea S., Hartwieg E. A., Cepko C. L. (1992) Multipotent neural cell lines can engraft and participate in development of mouse cerebellum. Cell 68, 33–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Niles L. P., Armstrong K. J., Rincón Castro L. M., Dao C. V., Sharma R., McMillan C. R., Doering L. C., Kirkham D. L. (2004) Neural stem cells express melatonin receptors and neurotrophic factors: colocalization of the MT1 receptor with neuronal and glial markers. BMC Neurosci. 5, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang Y., Ren W., Chen F. (2006) Knockdown of Stat3 in C17.2 neural stem cells facilitates the generation of neurons: a possibility of transplantation with a low level of oncogene. Neuroreport 17, 235–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shukitt-Hale B., Carey A. N., Jenkins D., Rabin B. M., Joseph J. A. (2007) Beneficial effects of fruit extracts on neuronal function and behavior in a rodent model of accelerated aging. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 1187–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Learish R. D., Bruss M. D., Haak-Frendscho M. (2000) Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase blocks proliferation of neural progenitor cells. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 122, 97–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim S. J., Son T. G., Park H. R., Park M., Kim M. S., Kim H. S., Chung H. Y., Mattson M. P., Lee J. (2008) Curcumin stimulates proliferation of embryonic neural progenitor cells and neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14497–14505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baur J. A., Pearson K. J., Price N. L., Jamieson H. A., Lerin C., Kalra A., Prabhu V. V., Allard J. S., Lopez-Lluch G., Lewis K., Pistell P. J., Poosala S., Becker K. G., Boss O., Gwinn D., Wang M., Ramaswamy S., Fishbein K. W., Spencer R. G., Lakatta E. G., Le Couteur D., Shaw R. J., Navas P., Puigserver P., Ingram D. K., de Cabo R., Sinclair D. A. (2006) Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature 444, 337–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park S. J., Ahmad F., Philp A., Baar K., Williams T., Luo H., Ke H., Rehmann H., Taussig R., Brown A. L., Kim M. K., Beaven M. A., Burgin A. B., Manganiello V., Chung J. H. (2012) Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. Cell 148, 421–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Whitney N. P., Eidem T. M., Peng H., Huang Y., Zheng J. C. (2009) Inflammation mediates varying effects in neurogenesis: relevance to the pathogenesis of brain injury and neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neurochem. 108, 1343–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Choi S. H., Li Y., Parada L. F., Sisodia S. S. (2009) Regulation of hippocampal progenitor cell survival, proliferation and dendritic development by BDNF. Mol. Neurodegener. 4, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blum R., Konnerth A. (2005) Neurotrophin-mediated rapid signaling in the central nervous system: mechanisms and functions. Physiology 20, 70–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Markus M. A., Morris B. J. (2008) Resveratrol in prevention and treatment of common clinical conditions of aging. Clin. Interv. Aging 3, 331–339 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Orallo F. (2008) Trans-resveratrol: a magical elixir of eternal youth? Curr. Med. Chem. 15, 1887–1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Athar M., Back J. H., Tang X., Kim K. H., Kopelovich L., Bickers D. R., Kim A. L. (2007) Resveratrol: a review of preclinical studies for human cancer prevention. Toxicol. Appl Pharmacol. 224, 274–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ramprasath V. R., Jones P. J. (2010) Anti-atherogenic effects of resveratrol. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 660–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Albani D., Polito L., Signorini A., Forloni G. (2010) Neuroprotective properties of resveratrol in different neurodegenerative disorders. Biofactors 36, 370–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moriya J., Chen R., Yamakawa J., Sasaki K., Ishigaki Y., Takahashi T. (2011) Resveratrol improves hippocampal atrophy in chronic fatigue mice by enhancing neurogenesis and inhibiting apoptosis of granular cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 34, 354–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leong C. W., Wong C. H., Lao S. C., Leong E. C., Lao I. F., Law P. T., Fung K. P., Tsang K. S., Waye M. M., Tsui S. K., Wang Y. T., Lee S. M. (2007) Effect of resveratrol on proliferation and differentiation of embryonic cardiomyoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 360, 173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Price N. L., Gomes A. P., Ling A. J., Duarte F. V., Martin-Montalvo A., North B. J., Agarwal B., Ye L., Ramadori G., Teodoro J. S., Hubbard B. P., Varela A. T., Davis J. G., Varamini B., Hafner A., Moaddel R., Rolo A. P., Coppari R., Palmeira C. M., de Cabo R., Baur J. A., Sinclair D. A. (2012) SIRT1 is required for AMPK activation and the beneficial effects of resveratrol on mitochondrial function. Cell Metab. 15, 675–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Blander G., Olejnik J., Krzymanska-Olejnik E., McDonagh T., Haigis M., Yaffe M. B., Guarente L. (2005) SIRT1 shows no substrate specificity in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9780–9785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Borra M. T., Smith B. C., Denu J. M. (2005) Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17187–17195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pacholec M., Bleasdale J. E., Chrunyk B., Cunningham D., Flynn D., Garofalo R. S., Griffith D., Griffor M., Loulakis P., Pabst B., Qiu X., Stockman B., Thanabal V., Varghese A., Ward J., Withka J., Ahn K. (2010) SRT1720, SRT2183, SRT1460, and resveratrol are not direct activators of SIRT1. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 8340–8351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kaeberlein M., McDonagh T., Heltweg B., Hixon J., Westman E. A., Caldwell S. D., Napper A., Curtis R., DiStefano P. S., Fields S., Bedalov A., Kennedy B. K. (2005) Substrate-specific activation of sirtuins by resveratrol. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17038–17045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang Q., Liang B., Shirwany N. A., Zou M. H. (2011) 2-Deoxy-d-glucose treatment of endothelial cells induces autophagy by reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase. PLoS One 6, e17234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jones R. G., Plas D. R., Kubek S., Buzzai M., Mu J., Xu Y., Birnbaum M. J., Thompson C. B. (2005) AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 18, 283–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rattan R., Giri S., Singh A. K., Singh I. (2005) 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-D-ribofuranoside inhibits cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo via AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39582–39593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vingtdeux V., Giliberto L., Zhao H., Chandakkar P., Wu Q., Simon J. E., Janle E. M., Lobo J., Ferruzzi M. G., Davies P., Marambaud P. (2010) AMP-activated protein kinase signaling activation by resveratrol modulates amyloid-β peptide metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9100–9113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Um J. H., Park S. J., Kang H., Yang S., Foretz M., McBurney M. W., Kim M. K., Viollet B., Chung J. H. (2010) AMP-activated protein kinase-deficient mice are resistant to the metabolic effects of resveratrol. Diabetes 59, 554–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Joe A. K., Liu H., Suzui M., Vural M. E., Xiao D., Weinstein I. B. (2002) Resveratrol induces growth inhibition, S-phase arrest, apoptosis, and changes in biomarker expression in several human cancer cell lines. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 893–903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhou R., Fukui M., Choi H. J., Zhu B. T. (2009) Induction of a reversible, non-cytotoxic S-phase delay by resveratrol: implications for a mechanism of lifespan prolongation and cancer protection. Br J. Pharmacol. 158, 462–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zang Y., Yu L. F., Nan F. J., Feng L. Y., Li J. (2009) AMP-activated protein kinase is involved in neural stem cell growth suppression and cell cycle arrest by 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside and glucose deprivation by down-regulating phospho-retinoblastoma protein and cyclin D. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6175–6184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zang Y., Yu L. F., Pang T., Fang L. P., Feng X., Wen T. Q., Nan F. J., Feng L. Y., Li J. (2008) AICAR induces astroglial differentiation of neural stem cells via activating the JAK/STAT3 pathway independently of AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6201–6208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang F., Wang H., Wu Q., Lu Y., Nie J., Xie X., Shi J. (2012) Resveratrol protects cortical neurons against microglia-mediated neuroinflammation. Phytother Res. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bastianetto S., Zheng W. H., Quirion R. (2000) Neuroprotective abilities of resveratrol and other red wine constituents against nitric oxide-related toxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Br J. Pharmacol. 131, 711–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kuhn H. G., Dickinson-Anson H., Gage F. H. (1996) Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J. Neurosci. 16, 2027–2033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van Praag H., Kempermann G., Gage F. H. (1999) Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 266–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kempermann G., Kuhn H. G., Gage F. H. (1997) More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment. Nature 386, 493–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim W. R., Christian K., Ming G. L., Song H. (2012) Time-dependent involvement of adult-born dentate granule cells in behavior. Behav. Brain Res. 227, 470–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cheng A., Wang S., Cai J., Rao M. S., Mattson M. P. (2003) Nitric oxide acts in a positive feedback loop with BDNF to regulate neural progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in the mammalian brain. Dev. Biol. 258, 319–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Briand L. A., Blendy J. A. (2010) Molecular and genetic substrates linking stress and addiction. Brain Res. 1314, 219–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Thoenen H. (1995) Neurotrophins and neuronal plasticity. Science 270, 593–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fusco S., Ripoli C., Podda M. V., Ranieri S. C., Leone L., Toietta G., McBurney M. W., Schütz G., Riccio A., Grassi C., Galeotti T., Pani G. (2012) A role for neuronal cAMP responsive-element binding (CREB)-1 in brain responses to calorie restriction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 621–626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Liu M., Wilk S. A., Wang A., Zhou L., Wang R. H., Ogawa W., Deng C., Dong L. Q., Liu F. (2010) Resveratrol inhibits mTOR signaling by promoting the interaction between mTOR and DEPTOR. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36387–36394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Palazuelos J., Ortega Z., Díaz-Alonso J., Guzmán M., Galve-Roperh I. (2012) CB2 cannabinoid receptors promote neural progenitor cell proliferation via mTORC1 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 1198–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Harada N., Zhao J., Kurihara H., Nakagata N., Okajima K. (2011) Resveratrol improves cognitive function in mice by increasing production of insulin-like growth factor-I in the hippocampus. J. Nutr. Biochem. 22, 1150–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ben Abdallah N. M., Slomianka L., Vyssotski A. L., Lipp H. P. (2010) Early age-related changes in adult hippocampal neurogenesis in C57 mice. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]