Background: Disruption of the DLK1-DIO3 region has been linked to tumorigenicity, but the mechanism has remained undetermined.

Results: Seven DLK1-DIO3 microRNAs were identified that target EMT-linked transcription factors, including TWIST1.

Conclusion: Silencing of the miRNA cluster activates the TWIST1 signaling network and confers morphological, molecular, and function changes consistent with an EMT.

Significance: Down-regulation of the DLK1-DIO3 microRNAs plays a crucial role in early EMT events.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, EMT, Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition, MicroRNA, Tumor Metastases, Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated, DLKI-DIO3, TWIST

Abstract

Development of metastatic disease accounts for the vast majority of cancer-related deaths. Nevertheless, few treatments exist that are designed to specifically inhibit processes that drive tumor metastasis. The imprinted DLK1-DIO3 region contains tumor-suppressing miRNAs, but their identity and function remain indeterminate. In this study we identify seven miRNAs in the imprinted DLK1-DIO3 region that function cooperatively to repress the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a critical step that drives tumor metastasis, as well as proliferation of carcinoma cells. These seven miRNAs (miRs 300, 382, 494, 495, 539, 543, and 544) repress a signaling network comprising TWIST1, BMI1, ZEB1/2, and miR-200 family miRNAs and silencing of the cluster, which occurs via hypermethylation of upstream CpG islands in human ductal carcinomas, confers morphological, molecular, and function changes consistent with an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Moreover, ectopic expression of miR-544 independently inhibited proliferation of numerous tumor cell lines by inducing the ATM cell cycle checkpoint pathway. These results establish the DLKI-DIO3 miRNA cluster as a critical checkpoint regulating tumor growth and metastasis and implicate epigenetic modification of the cluster in driving tumor progression. These results also suggest that promoter methylation status and miRNA expression levels represent new diagnostic tools and therapeutic targets to predict and inhibit, respectively, tumor metastasis in carcinoma patients.

Introduction

The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)2 plays an indispensible role in cellular diversification and has also recently been implicated in tumor metastasis and generation of therapy-resistant cancer stem cells (1–3). Although a number of gene regulatory networks modulate EMT, recent studies indicate that the process is also regulated by microRNAs (miRNAs) (4–7), which are small non-coding RNA molecules that act as posttranscriptional regulators of gene expression (8). For instance, miR-200 family members have been shown to repress expression of the transcription factors ZEB1/δEF1 and ZEB2/SIP1 as well as TGF-β2, which in turn repress expression of E-cadherin (CDH1), a membrane glycoprotein located in adherens junctions that promotes adhesion of neighboring epithelial cells (5, 9). Loss of CDH1 expression is a widely used maker of EMT and is associated with a poor prognosis in a variety of tumors.

Overexpression in epithelial cells of the transcription factor TWIST1, a potent EMT inducer, also suppresses CDH1 expression and endows cells with the enhanced migratory and invasive capabilities necessary for metastasis (10–13). TWIST1 induction in carcinoma cells initiates the activation of a complex gene regulatory network that also suppresses miR-200 family members and promotes formation of “invadopodia” via up-regulation of PDGFRα (14, 15). Indeed, TWIST1 has also emerged as a prognostic indicator of poor survival in a variety of invasive cancers and has been linked to the generation of cancer stem cells via its ability to regulate the polycomb protein BMI1, which promotes self-renewal of stem cell populations (10). Despite the wealth of evidence suggesting its importance in regulating cancer progression, invasion, and metastasis, drug inhibitors of TWIST1 have remained elusive.

The DLK1-DIO3 imprinted region located on human chromosome 14 contains several imprinted large and small non-coding RNA genes, including a large cluster of 52 miRNAs expressed from the maternally inherited homolog (16, 17). Recently, the DLK1-DIO3 imprinted region was shown to be aberrantly silenced in human and mouse induced pluripotent stem cells but not in fully pluripotent embryonic stem cells, suggesting that it plays an essential role in cell specification during EMT (18, 19). Moreover, disruption of the DLK1-DIO3 region has been linked to increased tumorigenicity (20). Nevertheless, the function of miRNAs within this imprinted region remains largely unexplored. Similarly, although TWIST1 is known to function as a potent EMT inducer and to regulate expression of EMT-associated miRNAs, few known miRNA regulators of TWIST1 expression have been identified to date. In this study, we identify seven miRNAs clustered within the DLK1-DIO3 region that function coordinately to repress the EMT program by targeting known EMT-inducing oncogenic transcription factors, including TWIST1. Moreover, we show that hypermethylation of upstream promoter elements silences expression of the miRNA cluster in human ductal carcinomas, thereby establishing a link between epigenetic modification, EMT, and tumor metastasis. Finally, we show that miR-544 also inhibits proliferation of a multitude of tumor cells lines via up-regulation of the ATM cell cycle checkpoint pathway, resulting in G1/S phase arrest. Collectively, these results identify the DLKI-DIO3 miRNA cluster as an early checkpoint control that must be bypassed to induce EMT and promote growth of carcinoma cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bioinformatics Analysis

A list of genes up- and down-regulated during the EMT program was obtained from previously conducted serial analysis of gene expression database experiments to examine differences between phenotypically epithelial and mesenchymal cell types. Gene 3′ UTR seed sequences were cross-referenced with miRNA sequences using the miRanda, TargetScan, and PicTar software packages to identify miRNA/target complementarity. MiRNA/target associations were visualized using the Cytoscape software package and examined for redundancy. Genes known to play an important role in EMT from literature and database searches and genes with high levels of redundancy were cloned and used for downstream molecular experimentation.

Cell Culture

Cell lines were obtained from the Cell-based Screening Facility at the Scripps Research Institute and maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 5% penicillin/streptomycin, except for MCF-10A cells, which were maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 ng/ml EGF, 0.5 mg/ml hydrocortisone, 100 ng/ml cholera toxin, 10 μg/ml insulin, and 5% penicillin/streptomycin. MCF-10A cells were treated with 5 ng/ml recombinant human TGF-β1 to induce EMT (R&D Systems).

Human Tumor Biopsy Samples

Fresh tissue biopsy samples were obtained from the Department of Pathology, Jupiter Medical Center, at the time of initial breast cancer diagnosis. Authorization and informed consent was given by each patient to examine the tissue specimens for expression of DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs according to approved institution guidelines and protocols. RNA from tissue samples was extracted immediately from the samples as described below.

Luciferase Reporter Assays

Human genomic DNA-derived 3′ UTRs of the indicated mRNAs were cloned into the pmirGlo dual luciferase expression vector (Promega) to generate firefly luciferase/3′ UTR constructs. Constructs were cotransfected with the appropriate miRNA or miRNA plus antagomir using polyethyleneamine (25kda, Polysciences, Inc.) into HEK-293 cells plated in triplicate in 96-well plates. 48 h post-transfection, cells were collected and analyzed using the DualGlo luciferase assay kit (Promega). Primers used for cloning are listed in supplemental Table S3. Unpaired Student's t test of the replicate relative luminescence values of mimic and inhibitor treatments was used to derive p values.

RNA Extraction and Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the total RNA purification kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (NorgenBiotek) and converted to cDNA using the miScript reverse transcription kit (Qiagen). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR for the indicated miRNAs was performed with miScript primer assays (Qiagen), and miRNA targets were analyzed using primers designed using PrimerQuest (Integrated DNA Technologies). All primer sequences are listed in supplemental Table S4. All reactions were performed using FastStart Universal SYBR Green MasterMix with Rox (Roche) on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT fast real-time RT-PCR system. All mRNA RT-PCR data are expressed relative to GAPDH, and all miRNA data are expressed relative to RNU6b (Qiagen). Fold change analysis was performed using RT2 Profiler RT-PCR array data analysis version 3.4 (SABiosciences). Paired Student's t test of the replicate 2̂(-ΔCt) values for each gene in the control group and treatment groups was used to determine p values. The R Project Statistical Computing software package was used in heat map analysis.

MiRNA Mimics, Inhibitors, and Transfection

Mimics and antagomir inhibitors of miR-300, miR-382, miR-494, miR-495, miR-539, miR-543, and miR-544 and appropriate controls (Qiagen) were transfected into cells using the RNAi Max Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) and the reverse transfection technique as described by the manufacturer. Transfections were repeated every 4 days for a period of 20 days for morphological change and CDH1 surface expression studies. Transfections were performed once, and cells were harvested after 5 days for quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis.

Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis

Analysis of 148 patients with corresponding annotated clinical outcomes data were conducted using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter software package (21). Patient samples were selected using the parameters of overall survival, upper quartile split with a patient cohort similar to Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results prevalence. All grades, estrogen receptor status, lymph node status, and progesterone receptor status were included in the analysis.

Immunoblotting

MDA-MB-231 cells were lysed in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors Na3VO4 (0.2 mm), Na2MoO4 (1 mm), and β-glycero-phosphate (5 mm). Anti-TWIST1 antibody was purchased from Sigma Aldrich; anti-BMI1, anti-CDH1, anti-VIM, and anti-EIF4e were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology; and anti-GAPDH was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Secondary IRDye-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse immunoglobulins were purchased from LI-COR Biosciences. Western blotting was performed according to standard protocols. Proteins were visualized by infrared imagining on an Odyssey Imager (LI-COR Biosciences).

Flow Cytometric Analysis

Cells were detached from cell culture plates using the non-enzymatic cell disassociation solution Cell Stripper (MediaTech, Inc.), incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CDH1 (BioLegend) for 10 min at 4 °C, and then washed three times with PBS before analysis. Alternatively, cells were incubated for 20 min at 4 °C in CytoFix/CytoPerm buffer (BD Biosciences) and then washed three times with Perm Wash buffer. After permeabilization and fixation, cells were incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-phospho-p53 (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4 °C and then washed three times with PBS. Cells were analyzed on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed using the FlowJo cytometric analysis software package (TreeStar).

Microscopy and Immunofluorescent Staining

MCF-10A, TGF-β1-treated MCF-10A, or MDA-MB-231 cells were repeatedly transfected with either miRNA mimics or inhibitors for 20 days. Prior to staining and imaging, cells were transferred to fibronectin-coated coverslips. Cells were stained with anti-CDH1 (BD Biosciences) according to the directions of the manufacturer. Coverslips were inverted on to slides with Vectashield with DAPI mounting media (Vector Labs). Phase contrast and fluorescent imaging was carried using the Leica DM3000 (Leica Microsystems) microscope with subsequent image analysis using the LAS Core software package.

Microarray Analysis

MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with either miR-544 or control-miR. Four days post-transfection, total RNA (five replicates per miR) was isolated using the total RNA purification kit (NorgenBioTek), converted to cDNA using the Affymetrix cDNA synthesis kit, and transcribed in vitro using the IVT labeling kit (Affymetrix). The GeneChip sample cleanup module (Affymetrix) was used for cDNA product cleanup. Biotin-labeled cDNA (20 μg) was fragmented and hybridized to the Affymetrix Human U133 Plus 2.0 microarray overnight in the Affy 640 hybridization oven with a speed of 60 rpm for 16 h. The Affymetrix Fluidics Station FS400 was used to wash and stain the microarrays prior to data collection scanning with the GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix). GeneChip operating software was used to quantify probe set intensity. The probe sets were analyzed with GCRMA normalization using Array Assist software (Stratagene).

Promoter Methylation Analysis

Real-time PCR primers for CpG-rich promoter regions were designed using Methyl Primer Express (Applied BioSystems) (supplemental Table 5). DNA methylation status was determined using the EpiTect Methyl qPCR assay (SABiosciences) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, DNA was isolated from breast cancer and normal primary tissue samples using the Qiagen genomic DNA isolation kit. Genomic DNA was digested with a mixture of methylation-sensitive, methylation-dependent, or both methylation-sensitive and methylation-dependent enzymes at 37 °C overnight. After enzyme deactivation at 65 °C for 20 min, real-time PCR was carried out according to the EpiTect protocol. The EpiTect Methyl DNA Methylation PCR Data Analysis software was used to determine the degree of DNA methylation from Ct values.

Invasion Assays

Cell invasion through a basement membrane extract was quantified using the QCM ECMatrix cell invasion assay kit (Millipore). MDA-MB-231 cells (3 × 105) transfected with the appropriate miRNA mimic were serum-starved for 72 h and plated without FBS in the upper chamber of a 24-well Boyden chamber precoated with basement membrane extract. The lower chamber contained media with 10% FBS, creating an FBS gradient. Cells were incubated for 48 h, after which non-invading cells were removed from the upper filter. Filter bottoms were fixed with methanol, stained with crystal violet, and counted under light microscopy.

CFSE and Cell Cycle Analysis

MDA-MB-231, MCF-10A, or TGF-β1-treated MCF-10A cells transfected with either miR-544 of control miR were incubated with 5 μm carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen) for 15 min at 37 °C, washed three times with PBS, and then cultured for 5 days. Cells were then harvested using Cell Stripper (MediaTech, Inc.) and analyzed by flow cytometry as described above. Alternatively, transfected MDA-MB-231 cells were incubated with 70% ethanol at 4 °C for 15 min, washed, and incubated with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (BD Biosciences) prior to flow cytometric analysis.

Hypoxia Analysis

MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in 5% or 1% oxygen in a hypoxia chamber for 48 h and compared with MDA-MB-231 cells grown under normoxic conditions (21% oxygen). Cells cultured in hypoxia were lysed under hypoxic conditions (5% or 1% oxygen), and cells cultured under normoxia were lysed under normoxic conditions followed by total RNA isolation as described previously. Total RNA was converted to cDNA with subsequent real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis. ATM and miR-544 were measured relative to the GAPDH and RNU6 housekeeping genes, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

A Student's t test analysis was performed to obtain p values for fold change analysis, methylation analysis, and gene expression profiles.

RESULTS

DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs Target EMT-inducing Molecules

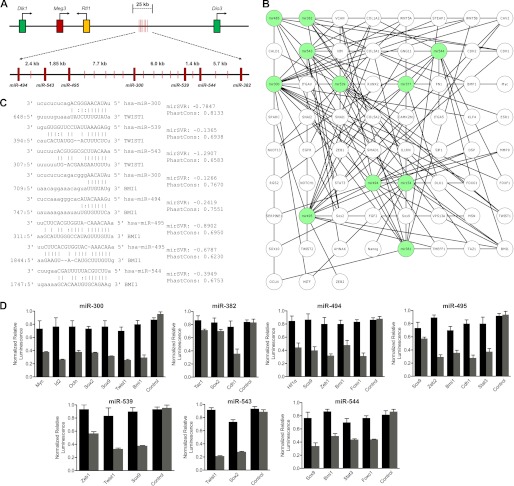

Although the imprinted DLKI-DIO3 genomic region has been implicated in tumorigenesis, the specific role of miRNAs clustered throughout this region has gone largely unexplored. Recently, TWIST1 was shown to regulate BMI1 expression, and both proteins function cooperatively to down-regulate CDH1 expression during EMT. Activation of TWIST1 occurs under hypoxic conditions by HIF1α up-regulation, an interaction that is dependent on STAT3-induced up-regulation of AKT (15, 20). HIF1α is also responsible for the regulation of the ZEB1/ZEB2 signaling pathway in later stages of EMT prior to metastasis (22–24). Additionally, recent studies have shown that SOX2 and SOX9 are up-regulated in early-stage breast cancer samples and promote breast cancer tumor initiation (7, 10). We located seven miRNAs clustered within a 21-kilobase span in the DLK1-DIO3 region (Fig. 1A) that were predicted to target these and other key molecules known to be up-regulated in EMT. Additionally, analysis of genes differentially expressed in epithelial versus mesenchymal lineages revealed a redundant miRNA signaling network with the potential to regulate the entire EMT program (Fig. 1B). Using computational analysis to predict the complementarity of miRNAs and their 3′ UTR sequences revealed TWIST1 as a high probability target of miR-300, miR-539, and miR-543. Moreover, miR-300, miR-494, miR-495, and miR-544 were identified as suppressors of BMI1 (Fig. 1C). Other miRNAs in the cluster were also predicted to target critical regulators of the EMT program, including ZEB1, ZEB2, SOX2, SOX9, STAT3, HIF1α, and CDH1 (supplemental Fig. S1).

FIGURE 1.

A miRNA cluster in the imprinted DLK1-DIO3 region targets inducers of the EMT program. A, schematic illustrating the genomic organization of the DLK1-DIO3 locus and the location of seven miRNAs identified in this study. B, schematic of the DLKI-DIO3 cluster miRNAs (green) paired with predicted EMT-associated mRNAs (white) demonstrating the breadth of the regulatory network and redundancy in miRNA function. C, complementarity between DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs and the 3′ UTR of TWIST1 and BMI1 with mirSVR and PhastCons scoring. D, HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with pmirGlo constructs containing the 3′ UTR of each indicated gene and miRNA mimic (gray bars) or mimic+antagomir (black bars). 48 h post-transfection, firefly luciferase expression was quantified, normalized to Renilla luciferase, and expressed relative to empty vector control. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. of three separate reactions. Significant (p < 0.05) differences were found for each miRNA mimic and target 3′ UTR versus mimic and control vector.

To confirm the inhibitory effect of these miRNAs on their identified targets, the 3′ UTRs of the target molecules were fused to a firefly luciferase (luc) reporter and transfected along with the appropriate miRNA mimics into HEK-293 cells (Fig. 1D). Mimics of miR-300, 539, and 543 each significantly (p < 0.05) repressed expression of the luc/3′ UTR TWIST1 construct, confirming the bioinformatics results. Additionally, mimics of miR-544, miR-494, miR-495, and miR-300 repressed expression of the luc/3′ UTR BMI1 construct, and miR-494 and miR-539 mimics inhibited luc/3′ UTR ZEB1 expression. In these studies, changes in reporter expression affected by each miRNA mimic were statistically significant (p < 0.05) as compared with the control miRNA mimic. Moreover, antagomir inhibition of the selected miRNAs restored luciferase activity in all cases, indicating specificity of the miRNA and the target sequence. Neither miRNAs nor their antagomirs significantly inhibited the control vector with a nonspecific sequence inserted in the 3′ UTR binding site. The close proximity of these miRNAs within the DLK1-DIO3 region and the known roles played by their targets suggest the cluster functions specifically to repress the EMT program in epithelial cells.

DLK1-DIO3 Cluster miRNAs Are Suppressed in Mammary Epithelial Cells Lines following EMT and in Human Breast Ductal Carcinomas

To establish biological relevance, we evaluated the expression of miR-300, miR-382, miR-494, miR-495, miR-539, miR-543, and miR-544 in the non-tumorigenic mammary epithelial cell line (MCF-10A), a tumorigenic mesenchymal cell line (MDA-MB-231), or in MCF-10A cells induced to undergo EMT by treatment with TGF-β1. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that all seven DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs were expressed in MCF-10A cells, markedly down-regulated in these cells following EMT induction by TGF-β1, and expressed at low levels in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 2A). Conversely, expression of transcripts targeted by these miRNAs, including TWIST1, BMI1, ZEB1, ZEB2, SOX2, SOX9, STAT3, HIF1α, and VIM, were not expressed in MCF-10A cells but were significantly up-regulated following treatment with TGF-β1 and were highly expressed in MDA-MB-231cells (Fig. 2B). CDH1 was also expressed in the MCF-10A cell line, down-regulated in TGF-β1-treated MCF-10A cells, and not expressed in MDA-MB-231 cells. These analyses demonstrate an inverse relationship between expression of the DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs and their validated targets whereby the targets are expressed in the absence of the miRNAs in cells with a mesenchymal phenotype and vice versa in cells that are phenotypically epithelial. These results further implicate the cluster in repressing the EMT program.

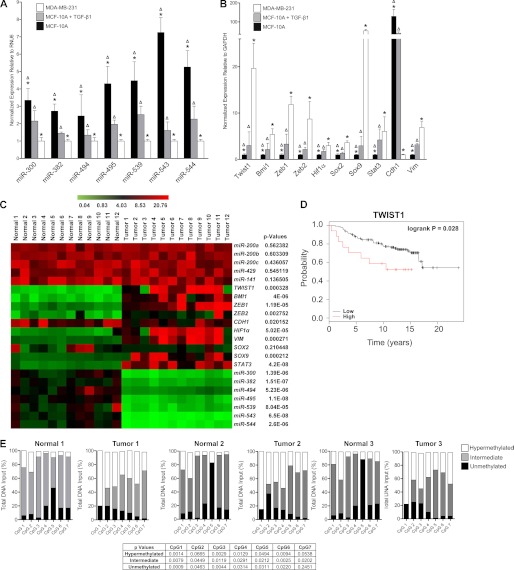

FIGURE 2.

Expression of DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs is inversely related with their validated targets in mammary epithelial cell lines during EMT and human ductal carcinomas. A and B, real-time PCR quantification of DLK1-DIO3 miRNA expression levels (A) and EMT-associated target mRNAs (B) in MCF-10A, TGF-β1-stimulated MCF-10A, and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Δ, significant differences (p < 0.05) between MCF-10A and TGF-β1-stimulated MCF-10A cells; *, significant differences (p < 0.05) between MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. C, heat map of expression levels of DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs and EMT-associated targeted mRNAs relative to RNU6 and GAPDH, respectively, in matched biopsies of normal human breast epithelial tissue and invasive ductal adenocarcinomas. High expression is represented in red, and low expression is represented in green. A paired Student's t test was used to determine the significance between groups of matched tissue pairs as indicated by p value. D, Kaplan-Meier plots representing the probability of overall survival in breast cancer patients stratified according to either TWIST1 expression. The logrank test p values reflect the significance of the association of TWIST1 on overall breast cancer survival. E, methylation status of seven CpG-rich islands upstream of the DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs in matched biopsies of normal breast epithelial tissue and ductal adenocarcinomas in three patients was evaluated using methylation-sensitive and methylation-dependent digestion followed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. p values for differences between tumor and normal samples for unmethylated, intermediate methylation, and hypermethylated are reported.

To demonstrate whether these miRNAs are down-regulated in human tumors, we compared their expression levels in invasive ductal carcinomas to matched normal ductal tissue biopsied from 12 untreated breast cancer patients at the time of initial diagnosis. Ductal carcinomas are invasive cancer cells semiconfined to the lactiferous ducts and surrounding tissue, making them a good model of early breast cancer malignancies. In all patient samples tested, DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs were found to be significantly (p < 0.01) down-regulated and their corresponding targets up-regulated to varied degrees as compared with normal breast tissue (Fig. 2C). CDH1 levels were also significantly down-regulated in ductal carcinoma samples compared with normal tissue samples (p < 0.05), but no change in expressed levels of miR-200 family miRNAs was evident between samples. These data indicate that down-regulation of CDH1 and up-regulation of ZEB1 can precede down-regulation of the miR-200 cluster despite evidence that the cluster functions as a negative regulator of the CDH1 repressor ZEB1. Collectively, these findings further suggest that down-regulation of the DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs represents a critical early step in EMT activation.

Noting a link between expression of TWIST1 and breast cancer, we extended our analysis to include measurements of endogenous TWIST1 in a collection of 26 breast cancer samples with annotated clinical outcomes history (21). Patients with higher endogenous levels of TWIST1 had a significantly lower (p < 0.05) survival rate than patients with lower levels of TWIST1 (Fig. 2D).

CpG island hypermethylation has been widely associated with silencing of tumor suppressor genes in oncogenesis (25). Upstream of the DLK1-DIO3 miRNA cluster are seven CpG islands that have been shown previously to be variably methylated, and this methylation is directly correlated to the down-regulation of cluster miRNAs (18, 26). We analyzed the methylation status of these seven CpG islands in matched normal breast tissue and ductal carcinomas to determine whether changes in their methylation patterns are associated with tumorigenesis. In normal breast tissue, the CpG islands were largely intermediately methylated, allowing for expression of the DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs. In contrast, increased hypermethylation (p < 0.05) in five of the seven CpG-rich islands was observed in three separate ductal carcinoma samples (Fig. 2E). These findings establish epigenetic modification as one mechanism that suppresses expression of the DLK1-DIO3 miRNA cluster in human breast epithelial carcinoma cells. Accordingly, expressed levels of the DLKI-DIO3 miRNAs and/or the epigenetic state of upstream promoter elements may have diagnostic value in predicting the likelihood of tumor progression and metastasis in patients diagnosed with breast cancer and possibly other carcinomas.

DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs Regulate a Signaling Network Involving TWIST1, BMI1, and miR-200 Family Members

During EMT polarized epithelial cells are converted to motile and invasive mesenchymal cells. Therefore, to examine how DLK1-DIO3 miRNA expression levels are altered during EMT in more detail, we quantified their expression in MCF-10A cells during a 7-day course of treatment with TGF-β1. As expected, expressed levels of all seven DLKI-DIO3 miRNAs were progressively decreased, whereas expression of validated targets, including TWIST1, BMI1, ZEB1, ZEB2, SOX2, SOX9, STAT3, HIF1α, and VIM, were progressively up-regulated (Fig. 3A). CDH1 expression was also down-regulated in response to TGF-β1 exposure. However, in contrast to results obtained with primary ductal carcinoma tissue, we observed down-regulation of the miR-200 cluster family in MCF-10A cells exposed to TGF-β1, which was likely attributed to TGF-β1-induced methylation of the miR-200 loci (27).

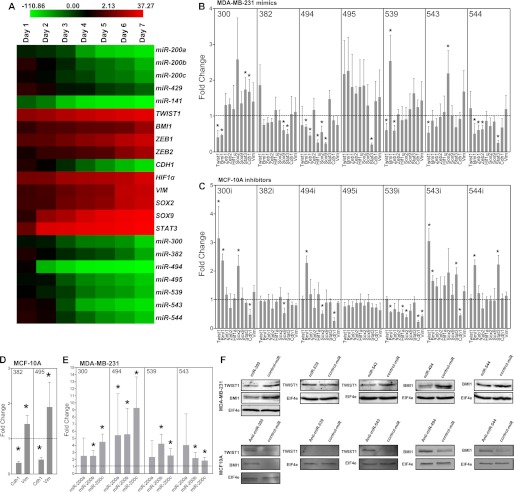

FIGURE 3.

DLKI-DIO3 miRNAs regulate a signaling network involving TWIST1, BMI1, and the miR-200 family. A, heat map of average fold change values relative to day 0 in DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs and EMT-associated target mRNAs in MCF-10A cells during a time course of TGF-β1 stimulation. High expression is represented by red, and low expression is represented by green. B and C, MDA-MB-231 (B) and MCF-10A (C) cells were transfected with the indicated miRNA mimics or antagomirs, respectively, and 5 days later real-time PCR was used to quantify expressed levels of the indicated miRNA targets. D, real-time PCR quantification of VIM and CDH1 expression in MCF-10A cells transfected with miR-382 and miR-495 mimics. E, real-time PCR quantification of miR-200 family members in MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing miR-300, miR-494, miR-539, and miR-543. F, Western blot analysis of TWIST1 and BMI1 expression levels in MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with miR-300, miR-539, miR-543, miR-494, and miR-544 mimics (upper panel) and MCF-10A cells transfected with the corresponding miRNA antagomirs (lower panel). All PCR data are represented as mean fold change ± S.E. of experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05.

We then investigated the effect of gain or loss of function of DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs in the MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. As expected, overexpression of miR-300, miR-539, and miR-543 in MDA-MB-231 cells significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited TWIST1 expression to varying degrees, and overexpression of miR-300, miR-494, and miR-544 significantly (p < 0.05) repressed expression of BMI1 (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, gain of function of miRNA activity produced compensatory changes in the expression of non-targeted mRNAs in cells. For example, overexpression of miR-300 in MDA-MB-231 cells up-regulated expression of the HIF1α regulator STAT3, and overexpression of miR-544 induced SOX2 expression. These compensatory changes likely function to maintain the mesenchymal phenotype of cells. For example, TWIST1 inhibition may lead to STAT3 activation to increase HIF1α, which is part of the HIF1α-TWIST1-BMI1 signaling axis and regulates ZEB1, ZEB2, SOX2, and SOX9 expression. Similar results were seen in MCF-10A cells induced to undergo EMT by exposure to TGF-β1 (supplemental Fig. S2). Compensatory changes in gene expression in MCF-10A cells is likely attributable to disruption of the TGF-β1-induced EMT response by DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNA overexpression.

Inhibition of each DLKI-DIO3 miRNA in MDA-MB-231 cells with miRNA antagomirs failed to produce any significant effects on mRNA expression levels of EMT regulators, as expected, because these miRNAs are not expressed in this cell line (supplemental Fig. S3). In contrast, inhibition of miR-300 and miR-543 with miRNA antagomirs in MCF-10A cells resulted in significant (p < 0.05) increases in TWIST1 and BMI1 expression levels and significantly (p < 0.05) repressed expression of CDH1, which was indicative of EMT (Fig. 3C). Moreover, inhibition of miR-494 also significantly (p < 0.05) induced expression of BMI1. Overexpression of miR-382 and miR-495 in the MCF-10A cell line significantly (p < 0.05) reduced expression of CDH1 transcripts and significantly (p < 0.05) induced expression of VIM (Fig. 3D and supplemental Fig. S4). Interestingly, overexpression of miR-300, miR-494, miR-539, and miR-543 significantly (p < 0.05) induced expression of specific miR-200 family members (Fig. 3E). This increase may be attributable to repression of TWIST1, which is known to bind to the miR-200 family promoter region and repress expression of this miRNA cluster (15).

To validate miRNA-mediated down-regulation of TWIST1 and BMI1, we performed Western blot analysis on MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with specific miRNA mimics. TWIST1 protein levels were diminished in cells transfected with miR-300 and miR-543 and BMI1 expression was also inhibited in cells transfected with miR-300, miR-494, and miR-544 (Fig. 3F Upper). Although miR-539 inhibited TWIST1 mRNA levels, cells transfected with a miR-539 mimic showed no detectable decrease in TWIST1 protein levels. Conversely, antagomir inhibition of miRNAs 300 and 543 in the MCF-10A cell line was sufficient to induce TWIST1 expression (Fig. 3F, lower panel). Similarly, antagomir inhibition of miRNAs 300, 494, and 544 in the MCF-10A cell line was sufficient to induce BMI1 up-regulation.

DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs Affect Changes in Cell Morphology, CDH1 Expression, and Tumor Cell Invasiveness

During EMT, epithelial cells adopt an elongated, mesenchymal-like phenotype that is attributed, in part, to down-regulation of CDH1. Overexpression of miR-382 and miR-495 following repeated transfection with respective miRNA mimic induced MCF-10A cells to adopt a mesenchymal-like morphology, as evidenced by phase contrast microscopy (Fig. 4A), and also caused down-regulation of the epithelial cell marker CDH1 on the basis of immunofluorescent staining (supplemental Fig. S5). Inhibition of miRNAs 300, 494, and 543 with miRNA antagomirs in the MCF-10A cell line yielded similar results. In contrast, ectopic expression of miR-300 caused MDA-MB-231 cells to lose their mesenchymal, spindle-like morphology and adopt a rounded, epithelial phenotype (Fig. 4B). Moreover, these cells exhibited a hyperelongated spindle-like morphology following overexpression of miR-544. However, no appreciable differences in CDH1 levels were observed following either overexpression or inhibition of the DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs in the MDA-MB-231 cell lines (supplemental Fig. S6). Overexpression of miR-300, miR-494, and miR-543 in MCF-10A cells was sufficient to block morphological changes induced following TGF-β1 treatment, demonstrating that these miRNAs blocked EMT (Fig. 4C and supplemental Fig. S7). Inhibition of the DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs in TGF-β1-treated MCF-10A cell lines had no effect on induction of the mesenchymal-like phenotype or down-regulation of CDH1.

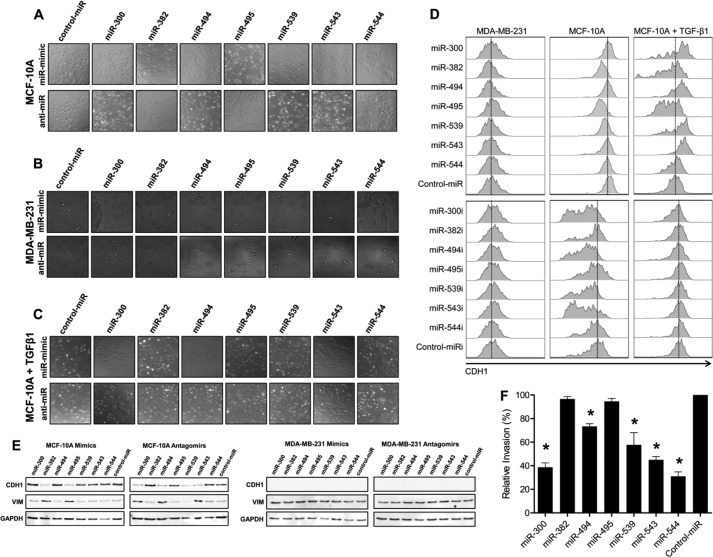

FIGURE 4.

DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs affect changes in cell morphology and tumor cell invasiveness. A–C, phase contrast microscopy of MCF-10A (A), MDA-MB-231 (B), and TGF-β1-treated MCF-10A (C) cell lines following 20 days of repeated transfection with the indicated miRNA mimics or antagomirs. D, MDA-MB-231, MCF-10A, and TGF-β1-treated MCF-10A cells were transfected with the indicated miRNA mimic or antagomir, and surface CDH1 expression was evaluated 5 days post-transfection by flow cytometry. E, Western blot analysis of CDH1 and VIM expression in MCF-10A (left panel) and MDA-MB-231 (right panel) cells following treatment with the indicated miRNA mimic or antagomir. Cells were evaluated 5 days post-transfection. F, MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with the indicated miRNA mimic, and invasion through a basement membrane toward an FBS gradient was quantified 48 h post-transfection. Data are presented as percent invasion relative to control miR-transfected cells. *, p < 0.05.

We also quantified the ability of DLKI-DIO3 miRNAs to modulate CDH1 protein expression in cells by flow cytometry. CDH1 was down-regulated by miR-382 and miR-495 miRNA mimics and by miR-300, miR-494, miR-539, and miR-543 antagomirs in the MCF-10A cell line, and these changes paralleled the morphological changes induced by these miRNAs in cells (Fig. 4D). Treatment of MCF-10A cells with TGF-β1 also down-regulated CDH1 expression, which paralleled changes in mRNA expression levels seen in the time course data (Fig. 3A). However, overexpression of miR-300, miR-494, miR-539, and miR-543 in MCF-10A cells blocked TGF-β1-induced decreases in CDH1 expression. Although ectopic expression of DLKI-DIO3 miRNAs induced morphological changes in MDA-MB-231 cells, expression of individual miRNAs in this cell line did not induce surface expression of CDH1 protein. These results indicate that modulation of the DKL1-DIO3 miRNAs contributes to CDH1 down-regulation in EMT. Indeed, these data indicate that down-regulation of the DLK1-DIO3 miRNA cluster is needed for complete repression of CDH1 expression during EMT because TWIST1 and its downstream target BMI1 act to suppress CDH1 transcription (10).

We also examined both CDH1 and VIM expression by Western blot analysis in both the MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cell lines after either overexpression or inhibition of the respective DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs (Fig. 4E). Paralleling our flow cytometric analysis findings, overexpression of miRNAs 382 and 495 in MCF-10As decreased CDH1 levels while inducing VIM expression. Inhibition of miRNAs 300, 494, and 543 decreased CDH1 expression while inducing VIM expression. Although CDH1 levels were decreased when miR-539 was inhibited, it was not accompanied by increases in VIM in line with our real-time quantitative PCR data. However, no changes were seen in the MDA-MB-231 cell line, indicating that although these miRNAs may play a role in inducing EMT, they are individually unable to elicit the reverse mesenchymal-epithelial transition.

EMT is accompanied by changes in cell motility, particularly the ability of cells to migrate to and invade surrounding tissues. Therefore, we measured how gain of function of DLKI-DIO3 miRNAs altered the invasive properties of MDA-MB-231 cells using a basement membrane extract trans-well assay. As shown in Fig. 4F, invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells was significantly (p < 0.01) inhibited following transfection of cells with miR-300, miR-494, miR-539, miR-543, or miR-544 mimics as compared with a control mimic. As expected, antagomir inhibition of DLK1-DIO3 miRNAs in these cells did not result in significant changes in cell motility (data not shown).

MiR-544 Inhibits Cancer Cell Proliferation by Inducing ATM Expression

Cancer cells typically exhibit uncontrolled proliferation because of aberrant regulation of the cell cycle. In the context of tumor progression, in early events leading to the entrance to the EMT program, cancer cells undergo increased proliferation to create a hypoxic environment (28). Hypoxia then triggers the activation of HIF1α, which in turn activates the TWIST1/BMI1 signaling axis, allowing EMT to progress. Importantly, we observed that transfection of MDA-MB-231 cells with a miR-544 mimic blocked cell proliferation as evidenced by changes in cell density (Fig. 5A). Flow cytometric analysis of carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester-labeled MDA-MB-231 transfected with a miR-544 mimic or control mimic confirmed that miR-544 blocked cell proliferation (Fig. 5B). The miR-544 mimic also significantly decreased the rate of cell division of MCF-10A cells treated with TGF-β1 but had essentially no effect on the growth of untreated MCF-10A cells. Transfection of a miR-544 mimic into a panel of breast, prostate, ovary, and lung cancer cell lines also consistently resulted in a significant (p < 0.01) inhibition of cell growth (Fig. 5C).

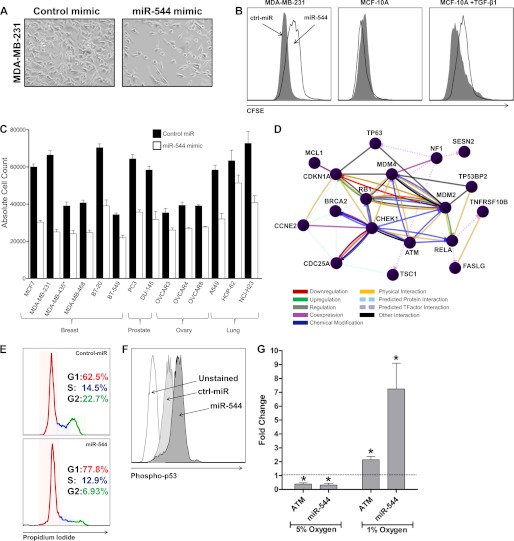

FIGURE 5.

MiR-544 suppresses cell proliferation by activating the ATM pathway. A, phase contrast microscopy of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with either a control miR or a miR-544 mimic 5 days post-transfection. B, MDA-MB-231, MCF-10A, and TGF-β1-stimulated MCF-10A cells were transfected with a control or miR-544 mimic, labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester, and analyzed by flow cytometry 5 days post-transfection. C, a panel of tumor cell lines were transfected with a miR-544 mimic or control miRNA, and the culture was expanded for 5 days. Then, the total number of cells in each culture was determined by counting. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. of triplicate experiments. Differences in absolute count between treatment groups for all cell lines examined were significant, with p < 0.05. Note: MDA-MB-435 has been referred to as a breast and melanoma derived cancer cell line in the literature. D, comparative analysis of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with a miR-544 or control miRNA by microarray revealed that miR-544 induced expression of ATM pathway components. E, propidium iodide cell cycle analysis demonstrating G1/S phase cell cycle arrest in MDA-MB-231 cells that overexpress miR-544. G1 is indicated in red, S phase in blue, and G2 in green. F, phospho-flow cytometric analysis revealed increased phosphorylated p53 levels in MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing miR-544. G, fold change analysis as measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR of ATM and miR-544 expression relative to normoxia control following 48-h exposure to 5% or 1% oxygen. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. of triplicate experiments. *, p < 0.05.

MiRNAs are known to down-regulate large numbers of target mRNAs (29). To delineate the mechanism by which miR-544 arrests growth of tumor cell lines, we used microarray analysis to interrogate genes that were up- or down-regulated following transfection of the miR-544 mimic into MDA-MB-231 cells (supplemental Tables S1 and S2). As determined previously by real-time RT-PCR, BMI1 was found to be down-regulated by miR-544 overexpression together with 617 other miR-544 targets determined by bioinformatics analysis. Interestingly, the ATM cell division checkpoint pathway was found to be significantly up-regulated in MDA-MB-2321 cells by miR-544 (30, 31). Although other miRNAs have been shown to suppress ATM, miR-544 is the first miRNA shown to up-regulate ATM expression (32). Moreover, miR-544 also up-regulated expression of CHEK1, MDM2, and CDC25A, which indicated that miR-544 inhibition of cell proliferation occurs by arresting cells in G1/S phase (Fig. 5D). Flow cytometric analysis of cells stained with propidium iodide confirmed that miR-544 expression significantly decreased the percentage of cells in S phase and G2 when compared with cells transfected with the control miRNA mimic (Fig. 5E). ATM acts by phosphorylating multiple substrates, including p53 kinase (33, 34). Although we did not observe significant up-regulation of p53 in our microarray analysis, we did observe increased phosphorylation of p53 as demonstrated by phospho-flow cytometry (Fig. 5F). Cells rapidly proliferate until they enter the hypoxic environment, at which point they cease growing and active survival mechanisms, which include the activation of ATM (12, 13, 28). We measured the expression levels of both miR-544 and ATM under mild hypoxia (5% oxygen) and severe hypoxia (1% oxygen) (Fig. 5G). Under mild hypoxia conditions, both miR-544 and ATM were found to be down-regulated compared with normoxia. However, severe hypoxic conditions resulted in the up-regulation of both miR-544 and ATM in comparison to normoxia conditions.

DISCUSSION

EMT is a highly complex process wherein epithelial cells transition to a mesenchymal fate and acquire migratory and invasive properties. EMT plays an essential role in embryonic development and, in the past decade, has also been implicated in tumor metastasis. In the latter case, EMT enables incipient carcinoma cells within a primary tumor to migrate and invade into surrounding tissues. Invasion then facilitates the subsequent steps of metastasis, including intravasation into the blood or lymph system, extravasation to distant tissues, colonization, and secondary tumor formation (1, 2). EMT has also been implicated in the genesis of cancer stem cells, which exhibit reduced sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents and are thought to contribute to tumor relapse following conventional therapy (35). Therefore, EMT drives two critical aspects of tumorigenesis, metastasis and relapse, which together account for the vast majority of cancer-related deaths. TWIST1 is a potent EMT inducer and functions in part to represses CDH1 expression, thereby allowing epithelial cells to delaminate and spread beyond the boundaries of the primary tumor (10, 14, 28). TWIST1 also functions as a pro-survival factor for incipient epithelial cancer cells and impinges upon numerous signaling pathways regulating tumor progression and metastasis (12). Therefore, a better understanding of how TWIST1 expression is induced in epithelial tumors is essential to understanding critical control points that regulate EMT, metastasis, and relapse and may also reveal new therapeutic targets to block these processes.

Recently, the miR-200 family was found to regulate EMT by directly suppressing expression of ZEB1 and ZEB2, which are associated with a number of human malignancies. However, ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression is typically not evident in early-stage epithelial cancers but, rather, is detected in metastatic cancers, making them poor diagnostic markers for early cancer detection. Likewise, evidence suggests that the miR-200 family is down-regulated in cancer cells that have already transitioned to a mesenchymal-like fate (5, 9). Therefore, there exists a gap between early events that initiate the EMT program and those that subsequently lead to down-regulation of the miR-200 family, derepression of ZEB1 and ZEB2, and loss of CDH1 expression in tumor cells. Our data demonstrate that the DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs function to repress the EMT program in epithelial cells by targeting expression of a large cadre of EMT-inducing oncogenic transcription factors. Indeed, our clinical analyses revealed higher levels of DLK1-DIO3 cluster miRNAs in normal breast tissue than in invasive ductal carcinoma samples, and miRNA expression levels in these samples were inversely correlated with a number of transcription factors that induce and/or regulate EMT, including TWIST1, BMI1, SOX2, SOX9, HIF1α, ZEB1, ZEB2, and STAT3. Moreover, our data show that at some stage in tumor progression the upstream promoter of the DLK1-DIO3 cluster becomes hypermethylated, which represses expression of the tumor-suppressing miRNAs and induces expression of a signaling network that activates EMT. Furthermore, silencing of the DLKI-DIO3 cluster represses CDH1 expression prior to changes in expression of the miR-200 family of miRNAs. Importantly, ZEB1 and ZEB2 are expressed at much lower levels in ductal carcinoma samples as compared with metastatic tumors. This result is consistent with other studies demonstrating that invasive ductal carcinomas express EMT-inducing transcription factors prior to undergoing complete EMT (11, 36). However, a mechanism to explain this phenomenon has remained elusive until now. Our data indicate that epigenetic modification and silencing of the DLKI-DIO3 miRNA cluster is a key early step that induces loss of CDH1 expression, initiates the EMT program, and promotes tumor cell invasion and metastasis. In the latter case, loss of miRNA function derepresses expression of TWIST1 and BMI1, which “prime” cells to undergo EMT by activating gene regulatory networks that promote EMT. A mesenchymal cell fate is then induced via down-regulation of miR-200 family members and further up-regulation of ZEB1 and ZEB2.

Our work also demonstrates that miR-544 plays a direct role in regulating proliferation of tumor cells. Specifically, ectopic expression of miR-544 was shown to induce expression of the ATM pathway, resulting in arrest in S or G2 phase of the cell cycle. Previous studies implicated the DLK1-DIO3 region in regulation of p53, but a mechanism for its inhibition of cell proliferation remained undefined (21). Here, we have revealed that miR-544 is capable of up-regulating the ATM pathway, leading to the phosphorylation of p53 and suppression of cancer cell proliferation. This finding yields strong indications for the use of miR-544 miRNA replacement therapy as a potential cancer treatment. Furthermore, the development of small molecule drug stabilizers of miR-544 may have implications in the treatment of precancerous lesions.

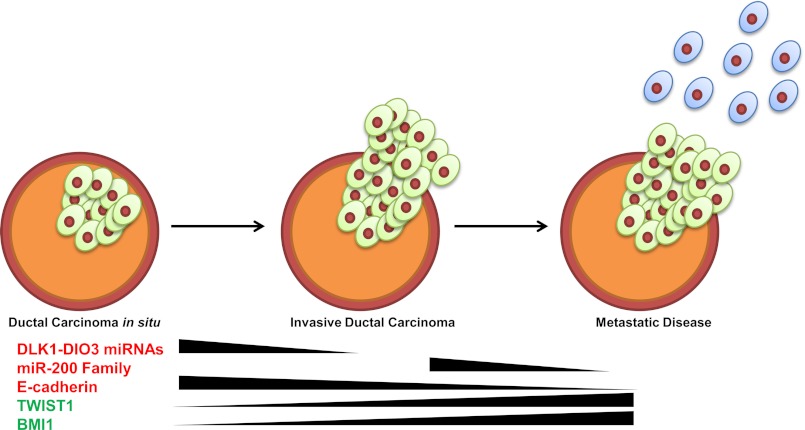

In summary, data described in this study reveal new insight into the complex molecular mechanisms that regulate tumor progression, EMT, and metastasis and implicate an understudied miRNA cluster within the imprinted DLK1-DIO3 region in these processes. Specifically, our results demonstrate that the seven miRNAs clustered within the DLK1-DIO3 region comprise a regulatory network that restrains the EMT program in epithelial cells by targeting a multitude of proteins, including TWIST1, which has no known miRNA regulators to date. Epigenetic silencing of the cluster bypasses the checkpoint and initiates a signaling network that activates the EMT program and also deregulates cell growth (Fig. 6). Therefore, modulation of these miRNAs may prove beneficial in inhibiting EMT in incipient carcinoma cells and, as such, provide novel therapeutic targets for development of drugs that specifically treat and/or prevent metastatic disease.

FIGURE 6.

The DLKI-DIO3 miRNA cluster functions as an early control checkpoint regulating tumor growth and metastasis. Shown is a schematic illustrating how down-regulation of the DLKI-DIO3 miRNA cluster initiates the EMT program by inducing expression of TWIST1, BMI1, and ZEB1/2 and inhibiting expression of CDH1. Activation of this molecular program results in down-regulation of miR-200 family miRNAs, enhanced expression of ZEB1/2, and further down-regulation of CDH1, resulting in EMT progression and tumor metastasis. Additionally, inhibition of miR-544 down-regulates expression of the ATM tumor suppressor protein and other cell cycle regulators, resulting in dysregulated tumor cell growth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Scripps Florida Genomics Core for performing microarray analysis and Melissa Baucus and David Carmel for help in culturing cells. We also thank Paul Garen, MD, and the Jupiter Medical Center Department of Pathology for help in tissue collection.

This research was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 NS052301-01A2 (to D. G. P.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7 and Tables S1–S5.

- EMT

- epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- miRNA

- microRNA

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- luc

- luciferase

- VIM

- vimentin

- CDH1

- E-cadherin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Thiery J. P. (2002) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 442–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thiery J. P., Acloque H., Huang R. Y., Nieto M. A. (2009) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 139, 871–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cui J., Mao X., Olman V., Hastings P. J., Xu Y. (2012) Hypoxia and miscoupling between reduced energy efficiency and signaling to cell proliferation drive cancer to grow increasingly faster. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 174–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang H., Li Y., Lai M. (2010) The microRNA network and tumor metastasis. Oncogene 29, 937–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gregory P. A., Bert A. G., Paterson E. L., Barry S. C., Tsykin A., Farshid G., Vadas M. A., Khew-Goodall Y., Goodall G. J. (2008) The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 593–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gregory P. A., Bracken C. P., Bert A. G., Goodall G. J. (2008) MicroRNAs as regulators of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Cycle 7, 3112–3118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leis O., Eguiara A., Lopez-Arribillaga E., Alberdi M. J., Hernandez-Garcia S., Elorriaga K., Pandiella A., Rezola R., Martin A. G. (2012) Sox2 expression in breast tumours and activation in breast cancer stem cells. Oncogene 31, 1354–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ambros V. (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park S. M., Gaur A. B., Lengyel E., Peter M. E. (2008) The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes Dev. 22, 894–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo W., Keckesova Z., Donaher J. L., Shibue T., Tischler V., Reinhardt F., Itzkovitz S., Noske A., Zürrer-Härdi U., Bell G., Tam W. L., Mani S. A., van Oudenaarden A., Weinberg R. A. (2012) Slug and Sox9 cooperatively determine the mammary stem cell state. Cell 148, 1015–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang J., Mani S. A., Donaher J. L., Ramaswamy S., Itzykson R. A., Come C., Savagner P., Gitelman I., Richardson A., Weinberg R. A. (2004) Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell 117, 927–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le Q.-T., Denko N. C., Giaccia A. J. (2004) Hypoxic gene expression and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 23, 293–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bencokova Z., Kaufmann M. R., Pires I. M., Lecane P. S., Giaccia A. J., Hammond E. M. (2009) ATM activation and signaling under hypoxic conditions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 526–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eckert M. A., Lwin T. M., Chang A. T., Kim J., Danis E., Ohno-Machado L., Yang J. (2011) Twist1-induced invadopodia formation promotes tumor metastasis. Cancer Cell 19, 372–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang M.-H., Wu M.-Z., Chiou S.-H., Chen P.-M., Chang S.-Y., Liu C.-J., Teng S.-C., Wu K.-J. (2008) Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF-1α promotes metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edwards C. A., Mungall A. J., Matthews L., Ryder E., Gray D. J., Pask A. J., Shaw G., Graves J. A., Rogers J., Dunham I., Renfree M. B., Ferguson-Smith A. C. (2008) The evolution of the DLKI-DIO3 imprinted domain in mammals. PLoS Biol. 6, e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hagan J. P., O'Neill B. L., Stewart C. L., Kozlov S. V., Croce C. M. (2009) At least ten genes define the imprinted Dlk1-Dio3 cluster on mouse chromosome 12qF1. PLoS ONE 4, e4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stadtfeld M., Apostolou E., Akutsu H., Fukuda A., Follett P., Natesan S., Kono T., Shioda T., Hochedlinger K. (2010) Aberrant silencing of imprinted genes on chromosome 12qF1 in mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 465, 175–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu L., Luo G. Z., Yang W., Zhao X., Zheng Q., Lv Z., Li W., Wu H. J., Wang L., Wang X. J., Zhou Q. (2010) Activation of the imprinted Dlk1-Dio3 region correlates with pluripotency levels of mouse stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19483–19490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xu Q., Briggs J., Park S., Niu G., Kortylewski M., Zhang S., Gritsko T., Turkson J., Kay H., Semenza G. L., Cheng J. Q., Jove R., Yu H. (2005) Targeting Stat3 blocks both HIF-1 and VEGF expression induced by multiple oncogenic growth signaling pathways. Oncogene 24, 5552–5560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Györffy B., Lanczky A., Eklund A. C., Denkert C., Budczies J., Li Q., Szallasi Z. (2010) An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 123, 725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang M. H., Hsu D. S., Wang H. W., Wang H. J., Lan H. Y., Yang W. H., Huang C. H., Kao S. Y., Tzeng C. H., Tai S. K., Chang S. Y., Lee O. K., Wu K. J. (2010) Bmi1 is essential in Twist1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 982–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aigner K., Dampier B., Descovich L., Mikula M., Sultan A., Schreiber M., Mikulits W., Brabletz T., Strand D., Obrist P., Sommergruber W., Schweifer N., Wernitznig A., Beug H., Foisner R., Eger A. (2007) The transcription factor ZEB1 (ΔEF1) promotes tumour cell dedifferentiation by repressing master regulators of epithelial polarity. Oncogene 26, 6979–6988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wellner U., Schubert J., Burk U. C., Schmalhofer O., Zhu F., Sonntag A., Waldvogel B., Vannier C., Darling D., zur Hausen A., Brunton V. G., Morton J., Sansom O., Schüler J., Stemmler M. P., Herzberger C., Hopt U., Keck T., Brabletz S., Brabletz T. (2009) The EMT-activator ZEB1 promotes tumorigenicity by repressing stemness-inhibiting microRNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 11, 1487–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Das P. M., Singal R. (2004) DNA methylation and cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 4632–4642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li W., Zhao X. Y., Wan H. F., Zhang Y., Liu L., Lv Z., Wang X. J., Wang L., Zhou Q. (2012) iPS cells generated without c-Myc have active Dlki-Dio3 region and are capable of producing full-term mice through tetraploid complementation. Cell Res. 21, 550–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gregory P. A., Bracken C. P., Smith E., Bert A. G., Wright J. A., Roslan S., Morris M., Wyatt L., Farshid G., Lim Y.-Y., Lindeman G. J., Shannon M. F., Drew P. A., Khew-Goodall Y., Goodall G. J. (2011) An autocrine TGF-beta/ZEB/miR-200 signaling network regulates establishment and maintenance of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 1686–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pouysségur J., Dayan F., Mazure N. M. (2006) Hypoxia signalling in cancer and approaches to enforce tumour regression. Nature 441, 437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim L. P., Lau N. C., Garrett-Engele P., Grimson A., Schelter J. M., Castle J., Bartel D. P., Linsley P. S., Johnson J. M. (2005) Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature 433, 769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Falck J., Mailand N., Syljuåsen R. G., Bartek J., Lukas J. (2001) The ATM-Chk2-Cdc25A checkpoint pathway guards against radioresistant DNA synthesis. Nature 410, 842–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cannito S., Novo E., Compagnone A., Valfrè di Bonzo L., Busletta C., Zamara E., Paternostro C., Povero D., Bandino A., Bozzo F., Cravanzola C., Bravoco V., Colombatto S., Parola M. (2008) Redox mechanisms switch on hypoxia-dependent epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 29, 2267–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu H., Du L., Nagabayashi G., Seeger R. C., Gatti R. A. (2010) ATM is down-regulated by N-Myc-regulated microRNA-421. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1506–1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Banin S., Moyal L., Shieh S., Taya Y., Anderson C. W., Chessa L., Smorodinsky N. I., Prives C., Reiss Y., Shiloh Y., Ziv Y. (1998) Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science 281, 1674–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Khosravi R., Maya R., Gottlieb T., Oren M., Shiloh Y., Shkedy D. (1999) Rapid ATM-dependent phosphorylation of MDM2 precedes p53 accumulation in response to DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14973–14977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tomaskovic-Crook E., Thompson E. W., Thiery J. P. (2009) Epithelial to mesenchymal transition and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 11, 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garzon R., Marcucci G., Croce C. M. (2010) Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 775–789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.