Abstract

The identification and differentiation of a large number of distinct molecular species with high temporal and spatial resolution is a major challenge in biomedical science. Fluorescence microscopy is a powerful tool, but its multiplexing ability is limited by the number of spectrally distinguishable fluorophores. Here we use DNA-origami technology to construct sub-micrometer nanorods that act as fluorescent barcodes. We demonstrate that spatial control over the positioning of fluorophores on the surface of a stiff DNA nanorod can produce 216 distinct barcodes that can be unambiguously decoded using epifluorescence or total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Barcodes with higher spatial information density were demonstrated via the construction of super-resolution barcodes with features spaced by ~40 nm. One species of the barcodes was used to tag yeast surface receptors, suggesting their potential applications as in situ imaging probes for diverse biomolecular and cellular entities in their native environments.

Introduction

Fluorescence microscopy is a versatile tool to visualize nanometer- to micrometer-sized entities. To study multiple species of interest, it is essential to develop multiplexed fluorescent tags (barcodes). Most existing fluorescent barcodes are constructed using either intensity encoding _ENREF_1 (e.g., microbeads with anisotropically embedded fluorophores1–5, cells with combinatorially expressed fluorescent proteins6, nanoarrays consisting of different fluorescent DNA tiles7, mRNA hybridized to fluorescent probes8) or geometrical encoding (e.g., inorganic particles with optical features9–14, nucleic acid double helices with tandem fluorescent labels15,16) _ENREF_8. Intensity encoding relies on the combination of multiple spectrally differentiable fluorophores in a controlled molar ratio. Geometrical encoding, on the other hand, is obtained by separating optical features beyond the microscope’s resolution limit (typically ~250 nm for diffraction-limited imaging and ~25–40 nm for current super-resolution imaging17) and arranging them in a specific geometric pattern. The multiplexing capability of geometrically encoded barcodes increases exponentially as additional spatially distinguishable fluorophores are incorporated. Thus, with a structurally stiff scaffold capable of defining the spatial arrangement of the fluorescent molecules, combinatorially large barcode libraries may be constructed.

Despite the remarkable success in synthesizing fluorescent barcodes for in vitro multiplexed detection1–5,7,9–16, little effort has been made to create robust single-molecule barcodes suitable as in situ imaging probes. Additionally, most existing fluorescent barcodes range between 2–100 μm in size, and construction of barcodes with smaller dimensions remains challenging (with only a few reports3,7,8,12 of sub-micrometer barcodes and no more than 11 distinct barcodes experimentally demonstrated8). Here we report a group of geometrically encoded fluorescent barcodes self-assembled from DNA. These barcodes are 400–800 nm in length, structurally stiff, reprogrammable in a modular fashion and easy to decode using epi-fluorescence or TIRF microscopy. As evidence of their multiplexing power, 216 distinct barcode species were constructed and resolved using diffraction-limited TIRF microscopy. Furthermore, barcodes with fluorescent features spaced below the diffraction limit were resolved using super-resolution microscopy. Finally, one species of the barcodes was used to tag yeast surface receptors, suggesting their potential application as in situ imaging probes.

Structural DNA nanotechnology exploits the well-defined double-helical structure of DNA and the predictable Watson-Crick base-paring rules to self-assemble designer nano-objects and devices.18–23 A particularly effective method is DNA origami.24–30 By folding a long, single-stranded “scaffold strand” using many short synthetic “staple strands”, this approach generates complex, shape-controlled, fully addressable nanostructures with sizes of up to hundreds of nanometers. By functionalizing selected staple strands, such nanostructures can be used to spatially organize fluorescent guest molecules, including small organic molecules31–33, metallic34 and semi-conductive nano-particles35. These properties make DNA origami a promising platform to build robust fluorescent barcodes, as control over the exact ratio of different fluorophores allows intensity encoding while spatial positioning of fluorophores facilitates geometrical encoding and can help minimize undesired inter-fluorophore quenching.

Single-labeled-zone fluorescent barcodes

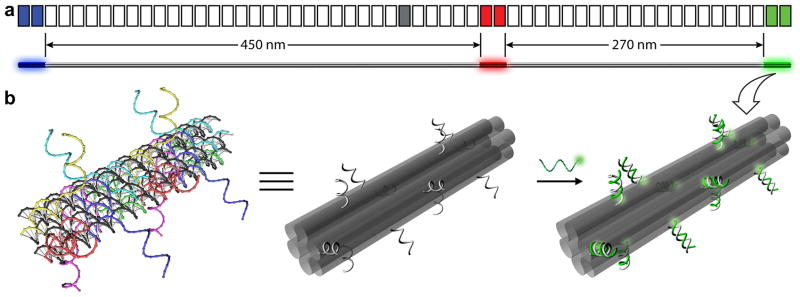

We first designed a family of 27 barcodes based on six-helix bundle DNA nanorods36 that are ~800 nm long (Figure 1a). Three 84-base-pair (~28 nm) zones on the nanorod were selected for fluorescent labeling, with inter-zone distances of 450 nm and 270 nm between the first and the last two zones, respectively. The fluorescently labeled zones were spatially arranged to generate an asymmetric fluorescent pattern that is decodable by diffraction-limited microscopy. For example, labeling the three zones (from left to right in Figure 1a) with “Blue” (B, Alexa Fluor 488), “Red” (R, Alexa Fluor 647) and “Green” (G, Cy3) fluorophores (the pseudo-colors reflect the excitation wavelength of the fluorophores) resulted in a BRG barcode that should be distinguishable from a GRB barcode. Therefore, 33 = 27 different barcodes can be made from three spectrally distinguishable fluorophores. Within each zone (Figure 1b), fluorescently modified oligonucleotides were hybridized to the twelve 21-base staple extensions (~6 nm between adjacent fluorophores) protruding out from the main body of the nanorod. To facilitate imaging, ten additional staple strands were designed with 5′ biotinylated extensions to enable surface attachment (Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Table S1–S4).

Figure 1. Design of the DNA-nanorod-based barcode.

(a) Two schematics of the Blue--Red-Green (BRG) barcode with a segment diagram on the top and a three-dimensional (3D) view at the bottom. The main-body of the barcode is a DNA nanorod formed by dimerizing two origami monomers, each consisting of 28 segments of 42 base pairs (~14 nm in length). The grey segment in the middle represents the junction where the two monomers are joined together. Three 84-bp zones of the nanorod are fluorescently labeled (shown as blue, red and green segments) to produce the BRG barcode. (b) 3D cartoons showing the details of one fluorescently labeled zone. Left: a strand model of an 84-bp zone before labeling. Each of the twelve 63-base staples (rainbow colors) contains two parts: the 42-base region at the 5′-end to fold the scaffold (black) into a six-helix bundle nanorod, and the 21-base extension at the 3′-end protrudes out for fluorescent labeling. Middle: a simplified model to emphasize the six-helix bundle structure (each helix shown as a semi-transparent grey cylinder) and the positioning of the twelve staple extensions (light-grey curls). Right: the zone with “green” fluorescent labeling. The labeling is achieved by hybridizing the Cy3 (glowing green spheres) modified strands to the staple extensions.

We assembled DNA-origami nanorods following the published protocol36 with slight modifications (Supplementary Materials and Methods). To validate our system, we randomly chose five distinct barcodes for quality control experiments. Two distinct features of these barcodes were clearly visible from the TIR and epi-fluorescence images (Figure 2a, top and Supplementary Figures S2, S3): first, each fluorescent zone was resolved as a single-color spot and each complete barcode consisted of three such spots; second, two of the neighboring spots were separated by a small gap while the other two neighbors sat closely together. Therefore, one can visually recognize geometrically encoded barcodes based on the color identity of the spots and their relative spatial positions, even without the aid of any specialized decoding software. Computer aided analysis of the BRG barcodes (Supplementary Figure S4, Supplementary Table S5) measured the average center-to-center distance between the neighboring spots to be 433±53 nm (mean±s.d., N=70; larger distance) and 264±52 nm (mean±s.d., N=70; smaller distance), confirming the correct formation of the barcodes. The small discrepancy between these experimentally measured distances and designed values (478 nm and 295 nm) may be attributed to random thermal bending of the nanorods (persistence length of ~1–2 μm29, cf. Figure S5). It is important to note that, unlike NanoString nCounter15, no stretching step was involved in the sample preparation. The separation between the fluorescent spots was exclusively created by the stiffness of the DNA nanorod. It is also notable that the spot intensities were not perfectly uniform across the whole image, which may be due to factors such as the uneven illumination of the sample and differences in labeling efficiency. Nevertheless, the TIRF images showed that the barcodes assembled as designed and were resolved unambiguously.

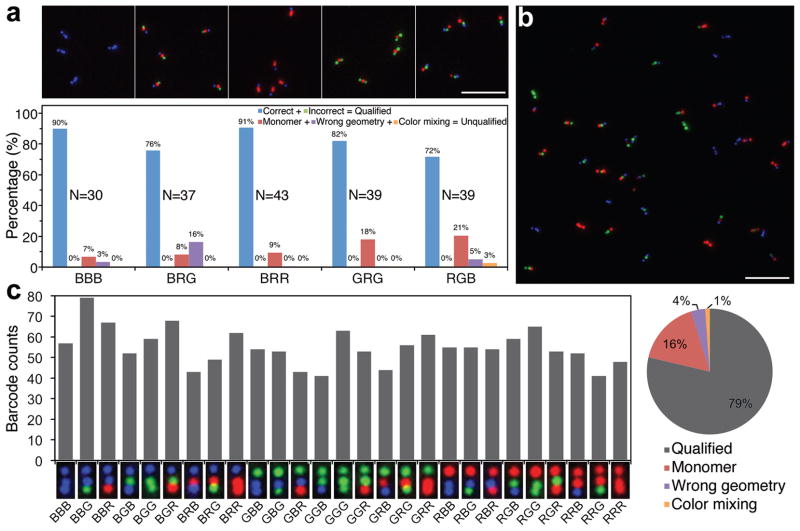

Figure 2. Single-labeled-zone fluorescent barcodes.

(a) Superimposed TIRF microscopy images of five barcode species (top) and the statistics from manual counting (bottom). The barcode types are noted under the horizontal axis of the diagram. Each bar-graph is generated by manually counting the objects in a 50 × 50 μm2 image (~40 barcodes, the exact sample size N is noted beside the corresponding bar-graph). (b) A representative image of the equimolar mixture of 27 barcode species. (c) Statistics obtained by analyzing twenty-seven 50 × 50 μm2 images of the 27-barcode mixture (1,485 barcode molecules). Left: counts of the 27 species (55 ± 9; mean ± s.d.). A representative TIRF image (1.4 × 0.7 μm2) of each barcode type is placed underneath the corresponding bar. Right: object sorting result shown as a pie-chart. Color scheme used for the bar-graphs in (a) and the pie-chart in (c): blue, correct barcodes (qualified barcode with expected identity); green, incorrect barcodes (qualified barcode with unexpected identity); red, monomer nanorods (one spot or two touching spots); purple, barcodes with wrong geometry (bending angle <120°, see Methods in SI); orange, barcodes containing at least one spot with two colors. Note that in the 27-barcode pool, correct vs. incorrect barcodes were not distinguishable because all barcode types were expected. As a result, the bars and pie representing the qualified barcodes in (c) are shown in gray. Scale bars: 5 μm.

We then manually investigated TIRF images with an area of 50 × 50 μm2 for five selected barcode species (Figure 2a, bottom). The objects in the images were first sorted into qualified (i.e., three single-color spots arranged in a nearly linear (with bending angle ≥120°, cf. Figure S4), and asymmetric fashion as designed) and unqualified (i.e., all other objects) barcodes. A qualified barcode was further categorized as correct or incorrect (false-positive) based on whether the geometric pattern of its constituent fluorescent spots corresponds to the designed type. The unqualified barcodes were further sorted into (1) monomer nanorods (single spot or two touching spots), (2) barcodes with “wrong” geometry (i.e., extreme bending), and (3) barcodes containing at least one spot with multiple colors. On average >80% of the visible objects were determined as qualified barcodes (i.e., ≤ 20% false-negative out of 188 observed objects), and these qualified barcodes were all correct (i.e., zero false-positive out of 154 qualified barcodes. See Supplementary Technical Notes).

For many applications it is important that several different barcode species coexist in one pool. Thus, it is important to examine the performance of our system when different barcode species are mixed. In an initial test, BRG and RGB barcodes were synthesized separately, mixed together at an equal molar ratio, and co-purified via gel electrophoresis. The TIRF analysis (Supplementary Figure S6) confirmed the 1:1 stoichiometry of the two barcodes and an overall assembly success rate (qualified barcode/all objects) of ~80%, suggesting that both barcodes maintained their integrity during the mixing and co-purification processes. In addition, over 98% of the qualified barcodes were either BRG or RGB barcode. The 2% false-positive rate was due to an unexpected barcode type, BGB (Supplementary Figure S6), which could be attributed to a rare occasion in which the front monomer of the BRG barcode lay in close proximity to the rear monomer of the RGB barcode.

Next we imaged a pool of all 27 members of the barcode family in which all species were mixed at equimolar ratio. TIRF images (Figure 2b and Supplementary Figure S7) showed that all types of barcodes were resolved. Statistical analyses of ~1,500 barcodes across twenty-seven 50 × 50 μm2 images revealed an average count of 55 barcodes per type with a standard deviation of 9 (Figure 2c), in rough agreement with the expected stoichiometry considering pipetting and sampling errors. The distribution of observed objects over the four categories was consistent with the values measured from single-type barcode samples (note that here correct vs. incorrect barcodes were not distinguishable, as all 27 types were included). The above observations suggest that the sub-micrometer-long DNA nanorod represents a reliable platform to construct geometrically encoded barcodes with built-in structural stiffness.

Dual-labeled-zone fluorescent barcodes

The multiplexing capability of the barcodes was enhanced by increasing the number of fluorophore species allowed per zone. We changed the sequence of six staple extensions per zone so that instead of using twelve identical fluorescent oligonucleotides for labeling, we used a combination of up to two fluorophore species, which allows more distinct fluorescence signatures (pseudo-colors) for each zone. This “dual-labeling” strategy generates six pseudo-colors (B, R, G, BG, BR, and GR) from three spectrally differentiable fluorophores. Consequently, the total number of distinct barcodes was raised from 33 = 27 to 63 = 216. Five members from the dual-labeled-zone barcode family were chosen for quality control testing (Figure 3a). The barcodes can be visually decoded either solely from the superimposed TIRF image or by examining the three separate channels simultaneously. For example, as shown in the first column of Figure 3a, the barcode “BG--GR-BR” (“--” and “-” denotes larger and smaller inter-zone distance in the barcode, respectively) exhibited two spots each in the blue, green, and red channels, but with descending gaps between them. In the superimposed image, the barcodes have the expected color mixing signature Cyan--Yellow-Pink. The correct formation of the other four barcode species was verified similarly (Figure 3a and Supplementary Figure S8). Although the pseudo-colors of the dual-labeled zones were not always uniform (e.g., some yellow spots were green-tinted while others were red-tinted) due to inconsistent labeling efficiency, the fluorescence signature of any given spot could be identified by checking the raw images acquired from the three imaging channels. Similar to single-labeled-zone barcodes, manual analysis of two 50 × 50 μm2 images of each of the 5 dual-labeled-zone barcode species revealed that 75–95% of the objects were qualified barcodes, of which 80–90% were the correct type (Figure 3b). Compared to single-labeled-zone barcodes, the percentage of qualified barcodes remained the same, while the false positive rate increased from zero (Figure 2a) to 10–20%, reflecting the expected decrease in the robustness of the dual-labeling strategy (cf. Supplementary Technical Notes). Note that all five barcodes examined here have each of their zones labeled with two distinct fluorophore species, likely making them among the most error-prone members of the dual-labeled-zone barcode family. Therefore, we would expect a smaller average false-positive rate from the whole family.

Figure 3. Dual-labeled-zone fluorescent barcodes.

(a) Typical TIRF microscopy images of five selected barcode species, shown both in separate channels and as superimposed images. Scale bar: 5 μm. (b) Statistics obtained by analyzing two 50 × 50 μm2 images of each barcode species (~85 barcodes, the exact sample size N is noted beside the corresponding bar-graph). The barcode types are noted under the horizontal axis of the diagram. Color scheme (unrelated to the pseudo-colors of the fluorophores): blue, correct barcodes (correct geometry and color identity); green, incorrect barcodes (correct geometry but incorrect color identity); red, monomer nanorods (one spot or two touching spots); purple, barcodes with wrong geometry (bending angle <120°, see Methods in SI). (c) Computer-aided barcode counting results of the 72-barcode pool (N=2,617) and the 216-barcode pool (N=7,243), where the number of qualified barcodes are plotted as bar-graphs (see Supplementary Tables S6 and S7 for numbers). A computer-generated reference barcode image is placed underneath the corresponding bar. Note that the same horizontal axis is used for both bar-graph diagrams. (d) A table containing one representative TIRF image (1.4 × 0.7 μm2) for each of the 216 dual-labeled-zone barcode species.

We next imaged a mixture containing 72 dual-labeled-zone barcode species, which were individually assembled and co-purified (Supplementary Figure S9). Custom MATLAB scripts were used to assist the decoding process (Supplementary Figure S10) in either a fully automated unsupervised or in a supervised mode in which the software’s best estimate of the barcode’s identity was presented to the user for approval. Comparison between supervised and unsupervised decoding results showed >80% agreement between the computer software and the user (cf. Methods and Supplementary Figure S11). The supervised analysis of thirty-six 64 × 64 μm2 TIRF images registered 2,617 qualified barcodes that belonged to 116 different species (Supplementary Table S6 and Figure 3c, top panel). The expected 72 species constituted ~98% of the total barcode population with an average barcode count of 36 per species and a standard deviation of 8. In contrast, the unexpected species averaged only ~1.4 barcodes per species (maximum 4 counts). Finally, we analyzed a mixture containing all the 216 members of the dual-labeled-zone barcode family (Supplementary Figure S12). Unsupervised software analysis of sixty 64 × 64 μm2 images registered an average count of 34±17 (mean±s.d., N= 7,243; cf. Supplementary Table S7 and Figure 3c, bottom panel) for each barcode species. This relatively large standard deviation may be attributed to the increase in the number of distinct barcode species and the decoding error in the fully automated data analysis. While this system could be further improved to achieve better assembly and decoding accuracy, our study demonstrated that 216 barcode species were successfully constructed and resolved (Figure 3d).

Sub-diffraction fluorescent barcodes

The multiplexing capability of the barcodes can also be enhanced by increasing the number of fluorescent zones and resolving them using super-resolution techniques37–40. We here use DNA-PAINT31 to obtain super-resolved images of barcodes with fluorescent zones spaced below the diffraction limit. In stochastic reconstruction microscopy41,42, most molecules are switched to a fluorescent dark (OFF) state, and only a few emit fluorescence (ON state). Each molecule is localized with nanometer precision43 by fitting its emission to a 2D Gaussian. DNA-PAINT exploits repetitive, transient binding of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides (“imager” strands) to complementary “docking” strands to obtain stochastic switching between fluorescence ON and OFF states (Figure 4a). In the unbound state, only background fluorescence is observed. Upon binding of an imager strand, its fluorescence emission is detected using TIRF microscopy.

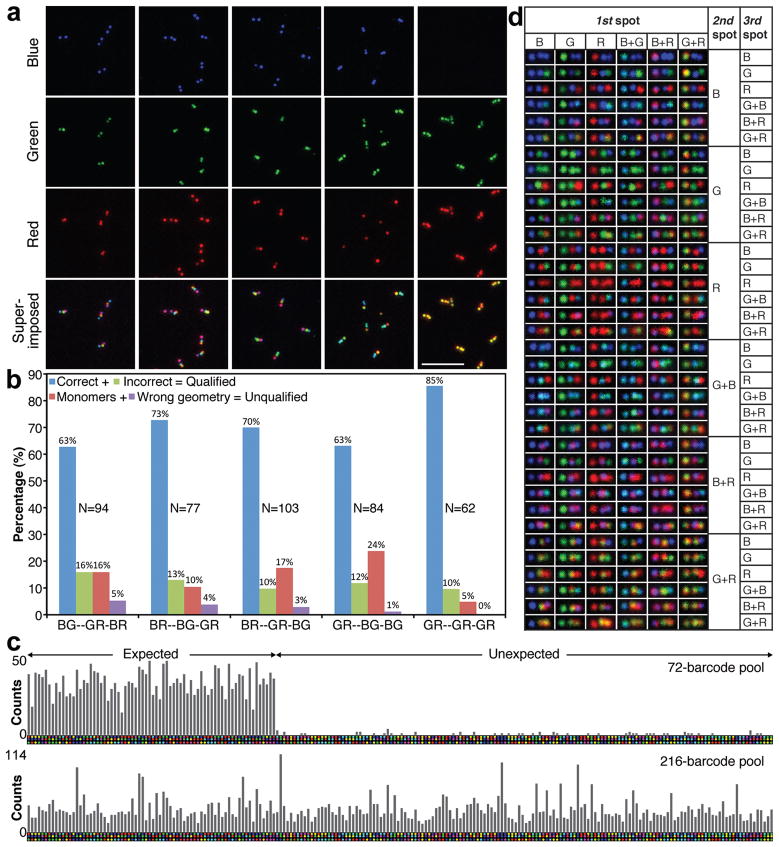

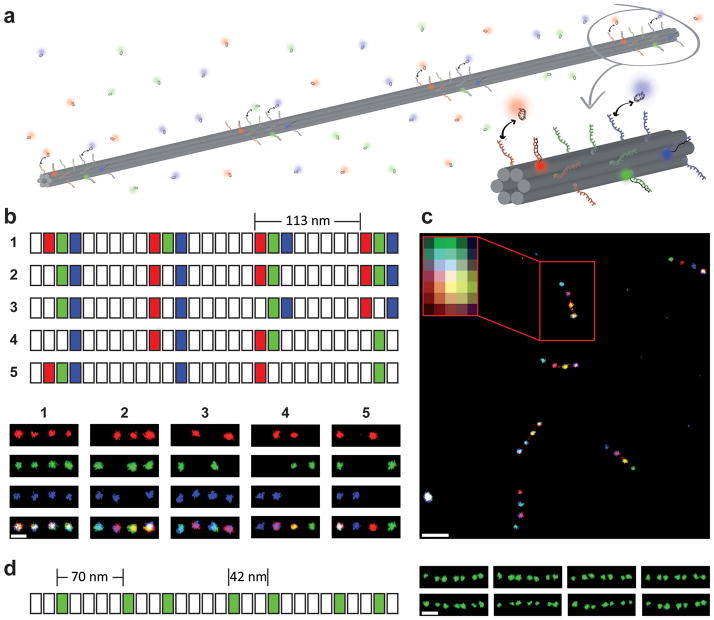

Figure 4. Super-resolution fluorescent barcodes.

(a) Schematic of barcodes for DNA-PAINT super-resolution imaging. The 400 nm DNA nanorod consists of 4 binding zones evenly spaced by ~113 nm. Each zone can be decorated with the desired combination of “docking” sequences for red, green or blue imager strands. The orthogonal imager strands bind transiently to their respective “docking” sites on the nanorod, creating the necessary “blinking” for super-resolution reconstruction. (b) Top: segment diagram (similar to Figure 1a) of the nanorod monomers used for creating five barcodes. Bottom: super-resolution images of the five barcodes shown in separate channels and as superimposed images. Scale bar: 100 nm. (c) Super-resolution image showing all five barcodes from (b) in one mixture. The inset shows the diffraction-limited image of a barcode. Scale bar: 250 nm. (d) An asymmetric barcode consisting of 7 binding zones for green imager strands spaced at ~70 nm and ~42 nm for larger and smaller distances, respectively. Scale bar: 100 nm.

Previously published work demonstrated single-color imaging with DNA-PAINT31. Here we have extended the technique to three-color imaging by using orthogonal imager strand sequences coupled to three spectrally distinct dyes (Atto488, Cy3b and Atto655). To demonstrate the feasibility of the three-color super-resolution barcode system, we designed a DNA nanorod monomer with 4 binding zones in a symmetric arrangement. The neighboring zones were separated by ~113 nm — well below the diffraction limit. Each binding zone consisted of 18 staple strands, which can display three groups of orthogonal docking sequences (six per group) for the blue, green or red imager strands to bind. As a proof-of-principle experiment, we designed five different barcodes (Figure 4a and top panel of b). The bottom panel of Figure 4b shows the super-resolution reconstruction for each channel separately as well as an overlay of all channels. Figure 4c shows a larger area containing all five barcodes. The unique pattern of the barcodes in all three channels can be resolved. The transient, repetitive binding of imager strands to docking sequences on the nanorod not only creates the necessary “blinking” behavior for localization but also makes the imaging more robust, as DNA-PAINT is not prone to photo-bleaching (Supplementary Figure S13). We also constructed an asymmetric barcode version consisting of seven binding zones for green imager strands with larger and smaller spacing of ~70 nm and ~42 nm, respectively (Figure 4d, Supplementary Figure S14 for overview). If three colors in this arrangement are used, (28 − 1)7 = 823,543 different barcodes can be constructed. In principle, one can also construct smaller barcodes while maintaining the multiplexing capability of the diffraction-limited barcode system. For example, ~100 nm long barcodes with three asymmetric binding zones would allow for 343 different signatures. The inherent modularity of our design allows the inter-zone distances to be tailored to a wide range of microscopes and applications.

Non-linear fluorescent barcodes

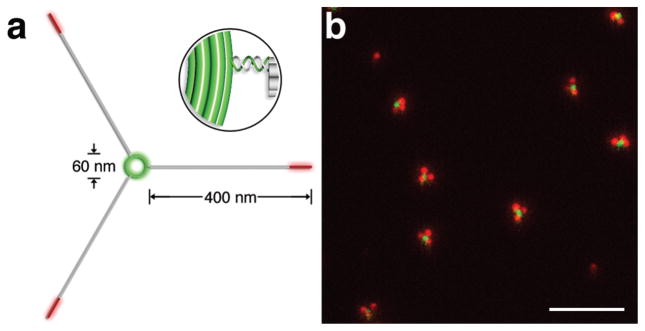

More sophisticated barcodes can be generated using DNA nanostructures with non-linear geometry. Figure 5 shows an example where three ~400 nm DNA rods were linked to the outer edge of a ~60 nm DNA ring through hybridization between staple extensions (Figure 5a, inset). Fluorescently labeling the ring and the far end of the nanorods generated a three-point-star-like pattern clearly resolvable under fluorescence microscopy. TIRF microscopy and transmission electron microscopy (Figure 5b & Supplementary Figures S15,16) revealed that about 50% of successfully assembled barcodes featured three nanorods surrounding the ring with a roughly 120° angle between each other as designed, while many other barcodes had significantly biased angles between neighboring nanorods due to the semi-flexible double-stranded DNA linker between the ring and the nanorods. It is conceivable that one can increase the system’s accuracy and robustness using a similar design to connect three identical “satellite” linear barcodes to a central hub (here the three satellite barcodes may share the hub as a common fluorescently labeled zone). Such a design would triplicate encoding redundancy. In addition, stiffer linkers between the ring and the protrusions (e.g., multi-helix DNA with strand crossovers) could be used to achieve better-defined barcode geometry.

Figure 5. Fluorescent barcode with non-linear geometry.

(a) Schematic. Three identical ~400-nm long DNA nanorods are linked to the outer edge of a DNA ring with diameter of ~60 nm through the hybridization between staple extensions (inset). The ring and the end of the rod are labeled with Cy3 (green) and Cy5 (red), respectively. (b) A representative TIRF microscopy image. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Fluorescent barcodes as in situ imaging probes

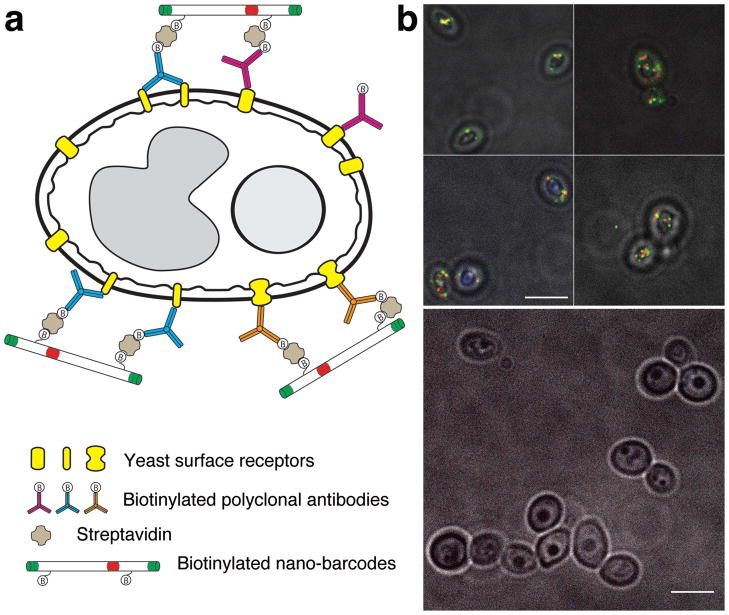

Modifying the barcodes with functional ligands such as antibodies and aptamers would allow the barcodes to tag specific biological samples and serve as multiplexed in situ imaging probes. In a proof-of-principle experiment, the GRG barcode was used to tag wild-type Candida albicans yeast. The yeast cells were first mixed with a biotinylated polyclonal antibody specific to C. albicans, then coated with streptavidin, and finally incubated with biotinylated GRG barcodes (Figure 6a). TIRF microscopy revealed the barcodes attached to the bottom surface of the yeast cells (Figure 6b, top panel and Supplementary Figure S17). While some of the nanorods landed awkwardly on the uneven cell walls of the yeast cells, a number of GRG barcodes were clearly resolved. In contrast, no barcode tagging was observed when non-biotinylated antibodies or barcodes were used (Figure 6b, bottom panel and Supplementary Figure S17), suggesting that no non-specific interaction existed between the barcode and the cell surface. Here only the bottom layer (~100-nm) of the 3D specimen was imaged to assure adequate lateral resolution and minimal background noise. With the development of 3D microscopy44, protein conjugation chemistry45–47 and DNA self-assembly techniques21–23, we believe a quantitative and multiplexed in situ imaging system is within reach.

Figure 6. Tagging yeast cells with the GRG barcodes as in situ imaging probes.

(a) Cartoon illustrating the tagging mechanism. The biotinylated barcodes are anchored on the yeast cell through streptavidin molecules bound to biotinylated polyclonal antibodies coated on the yeast surface. Only two of the ten biotinylated staples on the barcode are shown for clarity. (b) Superimposed microscope images (acquired in bright field and TIRF) of the yeast cells treated with the barcodes. Top: yeast cells treated as illustrated in (a). Bottom: negative control: yeast cells treated with non-biotinylated barcodes. Scale bars: 5 μm.

Discussion

In summary, we have constructed a new kind of geometrically encoded fluorescent barcodes using DNA-origami-based self-assembly. Our approach differs from previous optically decodable barcoding systems1–16 in the following three aspects: First, our barcodes are 400–800 nm in length, substantially smaller than existing geometrically encoded fluorescent barcodes. The sub-micrometer dimensions make them potentially useful as in situ single-molecule imaging probes. For example, we demonstrated the tagging of cell-surface proteins in yeast. The system also fulfills a technological challenge to build robust finite-size optical barcodes with smallest feature approaching or even smaller than the diffraction limit of visible light.

Second, our barcodes are self-assembled from DNA. Unlike previous constructions, their synthesis and purification requires no enzymatic reaction15, genomic engineering6, photolithography14, electrochemical etching48 or microfluidic devices1,14, and is easy to perform in a typical biochemistry lab. See Supplementary Technical Note for barcode cost. The barcodes can be easily modified to display sequence-specific attachment sites simply through DNA-origami staple extensions.

Third, the robustness and programmability of the DNA-origami-based platform enables high multiplexing capability. Here we successfully constructed 216 barcode species that were decoded in one pool, while previous sub-micrometer-sized fluorescent barcodes contained no more than 11 distinct barcodes3,7,8,12. Even compared to previous production of multi-color fluorescent barcodes up to 10 μm in size, our system is among the few examples1,15 that demonstrated more than 100 distinct barcode species in practice. The NanoString nCounter demonstrated larger numbers of barcodes coexisting in a homogenous solution.15 However, the reporter probes of the NanoString (~7-kb or ~2 μm double-stranded RNA-DNA-hybrid molecules) require stretching to make the barcodes resolvable, making them difficult to be used as in situ probes. In contrast, the stiff DNA-origami-based barcodes maintain their structural integrity when applied to cell surfaces, suggesting their potential use as in situ probes. Furthermore, the combination of the DNA-PAINT imaging technique and the DNA-origami-based nanorods allowed us to create nanoscopic “super-resolution” barcodes, suggesting the potential to achieve >100,000 distinct barcodes. Such a large number of barcodes opens opportunities like human gene expression measurement through ex situ imaging. In practice, it is likely that a small number of distinct codes could be sufficient to label the targets of interest in various application scenarios. For those applications, one could selectively use the best-performing subset of the barcode library and/or use barcodes with smaller sizes (e.g., ~100 nm barcode with three fluorescent spots).

In the future, we expect our barcodes to interface with the rapidly growing protein/antibody library and tagging techniques44–47 to yield a versatile imaging toolbox for single-molecule studies of biological events and biomedical diagnostics. For example, one can envision the utility of a library of barcodes modified with mono-clonal antibodies against the clusters of differentiation molecules49 (>300 known) for immunophenotyping applications50. We note that moving from in vitro imaging on a glass surface to in situ imaging on cell membrane may present substantial technical challenges. For example, crowding of multiple barcodes may render individual barcode unresolvable. While our current barcodes are potentially suitable for in situ labeling of multiple cell types (each carrying distinct surface markers), they are too bulky for multiplexed detection of many sub-cellular identities in a single-cell. This challenge could be addressed by using barcodes with more compact size and stiffer structures (e.g., DNA tetrahedrons with ~50 nm edges). While such smaller barcodes may be readily used to tag the surface markers of fixed cells, imaging them in living cells likely poses additional significant challenges: for example, to resolve barcodes on dynamic living cell membranes may require higher temporal resolution than provided by current super-resolution microscopy techniques. The barcodes constructed here represent the first experimental demonstration of a large number of sub-micrometer geometrically encoded fluorescent barcodes that are structurally stiff and optically resolvable. The fast progress of nanotechnology’s ability to engineer shape and microscopy’s ability to resolve shape should enable future constructions of more versatile and powerful geometrically encoded barcodes for diverse biomedical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Steinhauer and Sebastian Piet Laurien for help with super-resolution software development. We thank the Harvard Center for Biological Imaging as well as the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School for the use of their microscopes. We thank Shawn M. Douglas for providing TEM images used in Supplementary Figure S5. This work is supported by an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award 1DP2OD007292, an NSF Faculty Early Career Development Award CCF1054898, an Office of Naval Research Young Investigator Program Award N000141110914, an Office of Naval Research grant N000141010827, and a Wyss Institute for Biologically Engineering Faculty Startup Fund to P.Y.; and an NIH Director’s New Innovator Award 1DP2OD004641 and a Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering Faculty Award to W.M.S. C. Li, D.L. and G.M.C. acknowledge support from NHGRI CEGS. R.J. acknowledges support from the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation through a Feodor Lynen fellowship.

Footnotes

Author contributions:

C. Lin conceived the project, designed and conducted the majority of the experiments, analyzed the data, and prepared the majority of the draft. R.J. conceived the super-resolution barcode study, designed and conducted experiments for this study, analyzed the data, and prepared the draft. A.M.L. wrote the MATLAB script for the automated barcode deciphering, and prepared the draft. C. Li wrote the C script for the barcode geometry characterization. D.L. (with C. Lin) performed the yeast tagging experiment. G.M.C. championed multiplexed in situ, supervised C. Li and D.L., and critiqued the data and draft. W.M.S. conceived the project, discussed the results, and prepared the draft. P.Y. conceived, designed, and supervised the study, interpreted the data, and prepared the draft. All authors reviewed and approved the draft.

Competing financial interests statement:

The authors declare competing financial interests: a provisional U.S. patent application has been filed.

References

- 1.Fournier Bidoz S, et al. Facile and rapid one-step mass preparation of quantum-dot barcodes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5577–5581. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han M, Gao X, Su JZ, Nie S. Quantum-dot-tagged microbeads for multiplexed optical coding of biomolecules. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:631–635. doi: 10.1038/90228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Cu YTH, Luo D. Multiplexed detection of pathogen DNA with DNA-based fluorescence nanobarcodes. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nbt1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcon L, et al. ‘On-the-fly’ optical encoding of combinatorial peptide libraries for profiling of protease specificity. Molecular bioSystems. 2010;6:225–233. doi: 10.1039/b909087h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu H, et al. Multiplexed SNP genotyping using the Qbead system: a quantum dot-encoded microsphere-based assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livet J, et al. Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature. 2007;450:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin C, Liu Y, Yan H. Self-assembled combinatorial encoding nanoarrays for multiplexed biosensing. Nano letters. 2007;7:507–512. doi: 10.1021/nl062998n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levsky JM, Shenoy SM, Pezo RC, Singer RH. Single-cell gene expression profiling. Science. 2002;297:836–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1072241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braeckmans K, et al. Encoding microcarriers by spatial selective photobleaching. Nature materials. 2003;2:169–173. doi: 10.1038/nmat828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dejneka MJ, et al. Rare earth-doped glass microbarcodes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:389–393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0236044100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gudiksen MS, Lauhon LJ, Wang J, Smith DC, Lieber CM. Growth of nanowire superlattice structures for nanoscale photonics and electronics. Nature. 2002;415:617–620. doi: 10.1038/415617a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, et al. Controlled fabrication of fluorescent barcode nanorods. ACS nano. 2010;4:4350–4360. doi: 10.1021/nn9017137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicewarner-Pena SR. Submicrometer metallic barcodes. Science. 2001;294:137–141. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5540.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pregibon DC, Toner M, Doyle PS. Multifunctional encoded particles for high-throughput biomolecule analysis. Science. 2007;315:1393–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.1134929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiss GK, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao M, et al. Direct determination of haplotypes from single DNA molecules. Nature methods. 2009;6:199–201. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toomre D, Bewersdorf J. A new wave of cellular imaging. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:285–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seeman NC. Nucleic acid junctions and lattices. J Theor Biol. 1982;99:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aldaye FA, Palmer AL, Sleiman HF. Assembling materials with DNA as the guide. Science. 2008;321:1795–1799. doi: 10.1126/science.1154533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin C, Liu Y, Yan H. Designer DNA nanoarchitectures. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2009;48:1663–1674. doi: 10.1021/bi802324w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nangreave J, Han D, Liu Y, Yan H. DNA origami: a history and current perspective. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2010;14:608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.06.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shih WM, Lin C. Knitting complex weaves with DNA origami. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tørring T, Voigt NV, Nangreave J, Yan H, Gothelf KV. DNA origami: a quantum leap for self-assembly of complex structures. Chemical Society Reviews. 2011 doi: 10.1039/c1cs15057j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothemund PWK. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature. 2006;440:297–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Douglas SM, et al. Self-assembly of DNA into nanoscale three-dimensional shapes. Nature. 2009;459:414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature08016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dietz H, Douglas SM, Shih WM. Folding DNA into twisted and curved nanoscale shapes. Science. 2009;325:725–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1174251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen ES, et al. Self-assembly of a nanoscale DNA box with a controllable lid. Nature. 2009;459:73–76. doi: 10.1038/nature07971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han D, Pal S, Liu Y, Yan H. Folding and cutting DNA into reconfigurable topological nanostructures. Nature nanotechnology. 2010;5:712–717. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liedl T, Högberg B, Tytell J, Ingber DE, Shih WM. Self-assembly of three-dimensional prestressed tensegrity structures from DNA. Nature nanotechnology. 2010;5:520–524. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han D, et al. DNA origami with complex curvatures in three-dimensional space. Science. 2011;332:342–346. doi: 10.1126/science.1202998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jungmann R, et al. Single-molecule kinetics and super-resolution microscopy by fluorescence imaging of transient binding on DNA origami. Nano letters. 2010 doi: 10.1021/nl103427w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinhauer C, Jungmann R, Sobey TL, Simmel FC, Tinnefeld P. DNA origami as a nanoscopic ruler for super-resolution microscopy. Angewandte Chemie (International ed in English) 2009;48:8870–8873. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lund K, et al. Molecular robots guided by prescriptive landscapes. Nature. 2010;465:206–210. doi: 10.1038/nature09012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pal S, Deng Z, Ding B, Yan H, Liu Y. DNA-origami-directed self-assembly of discrete silver-nanoparticle architectures. Angewandte Chemie (International ed in English) 2010;49:2700–2704. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bui H, et al. Programmable Periodicity of Quantum Dot Arrays with DNA Origami Nanotubes. Nano letters. 2010;10:3367–3372. doi: 10.1021/nl101079u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Douglas SM, Chou JJ, Shih WM. DNA-nanotube-induced alignment of membrane proteins for NMR structure determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6644–6648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700930104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hell SW. Far-field optical nanoscopy. Science. 2007;316:1153–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.1137395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang B, Babcock H, Zhuang X. Breaking the diffraction barrier: super-resolution imaging of cells. Cell. 2010;143:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogelsang J, et al. Make them blink: probes for super-resolution microscopy. Chemphyschem: a European journal of chemical physics and physical chemistry. 2010;11:2475–2490. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter NG, Huang CY, Manzo AJ, Sobhy MA. Do-it-yourself guide: how to use the modern single-molecule toolkit. Nature Methods. 2008;5:475–489. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Betzig E, et al. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science. 2006;313:1642–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1127344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rust MJ, Bates M, Zhuang X. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) Nat Methods. 2006;3:793–795. doi: 10.1038/nmeth929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yildiz A, et al. Myosin V walks hand-over-hand: single fluorophore imaging with 1.5-nm localization. Science. 2003;300:2061–2065. doi: 10.1126/science.1084398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones SA, Shim SH, He J, Zhuang X. Fast, three-dimensional super-resolution imaging of live cells. Nature methods. 2011;8:499–508. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gautier A, et al. An engineered protein tag for multiprotein labeling in living cells. Chem Biol. 2008;15:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keppler A, et al. A general method for the covalent labeling of fusion proteins with small molecules in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nbt765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klein T, et al. Live-cell dSTORM with SNAP-tag fusion proteins. Nature methods. 2011;8:7–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0111-7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cunin F, et al. Biomolecular screening with encoded porous-silicon photonic crystals. Nature materials. 2002;1:39–41. doi: 10.1038/nmat702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matesanz-Isabel J, et al. New B-cell CD molecules. Immunol Lett. 2011;134:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maecker HT, McCoy JP, Nussenblatt R. Standardizing immunophenotyping for the Human Immunology Project. Nature reviews Immunology. 2012;12:191–200. doi: 10.1038/nri3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.