Abstract

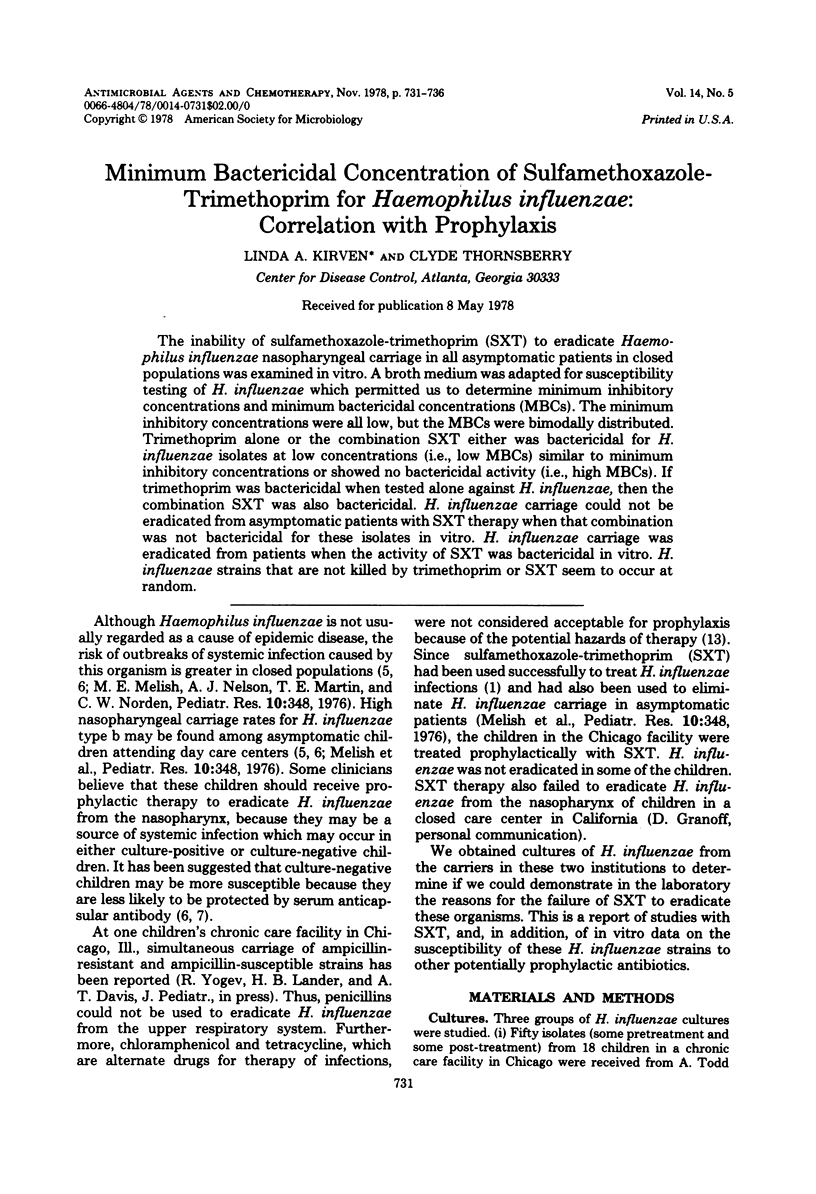

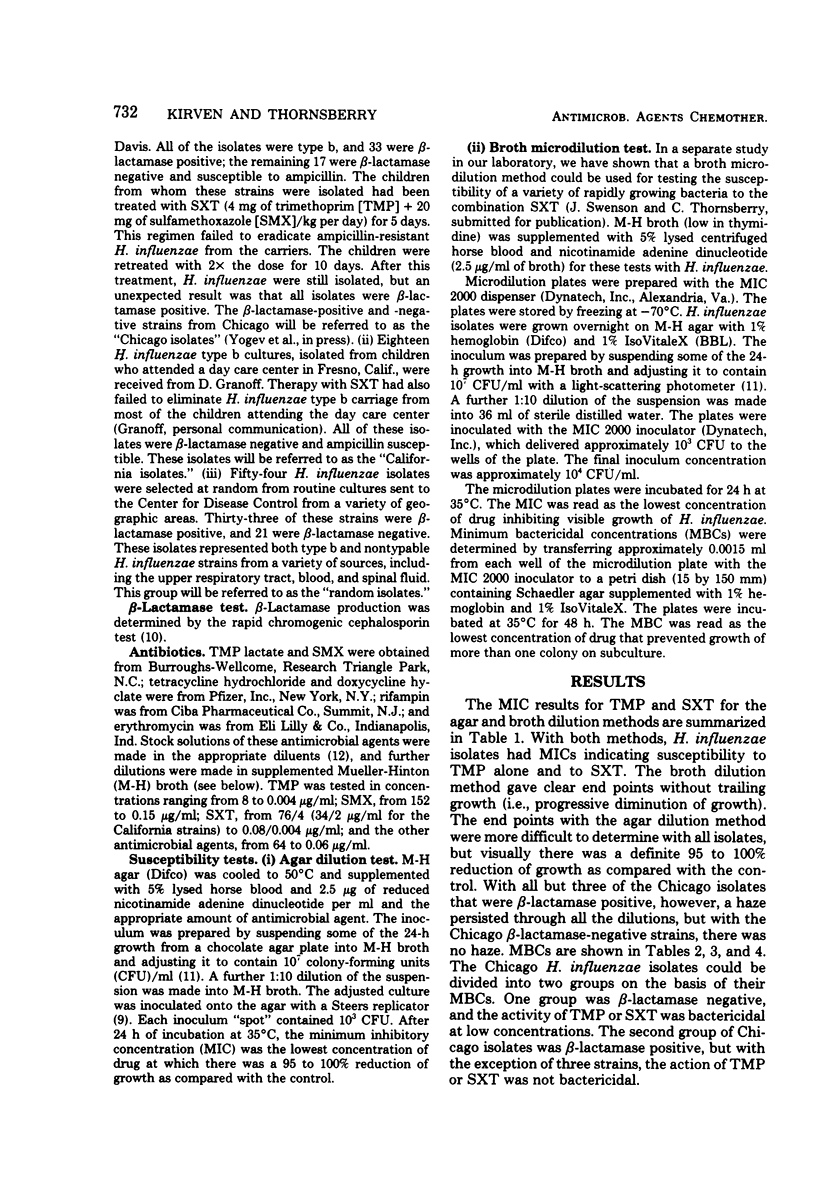

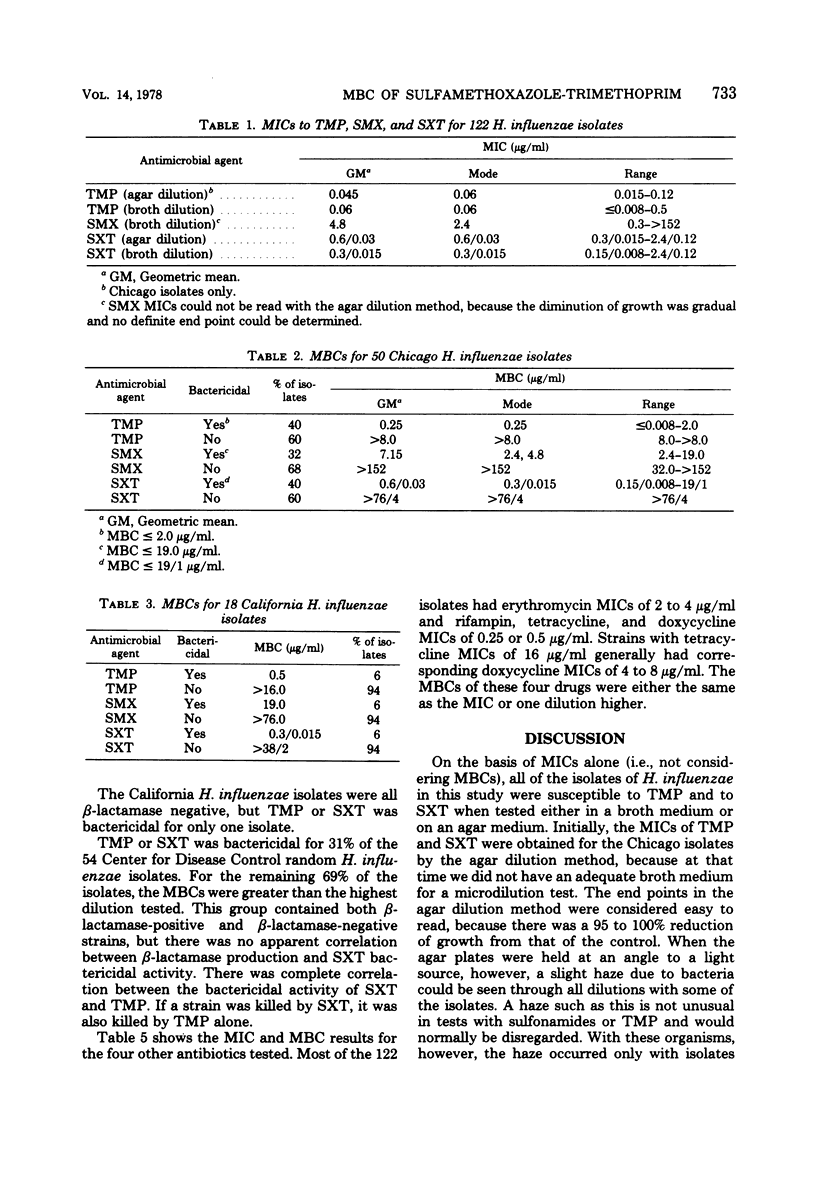

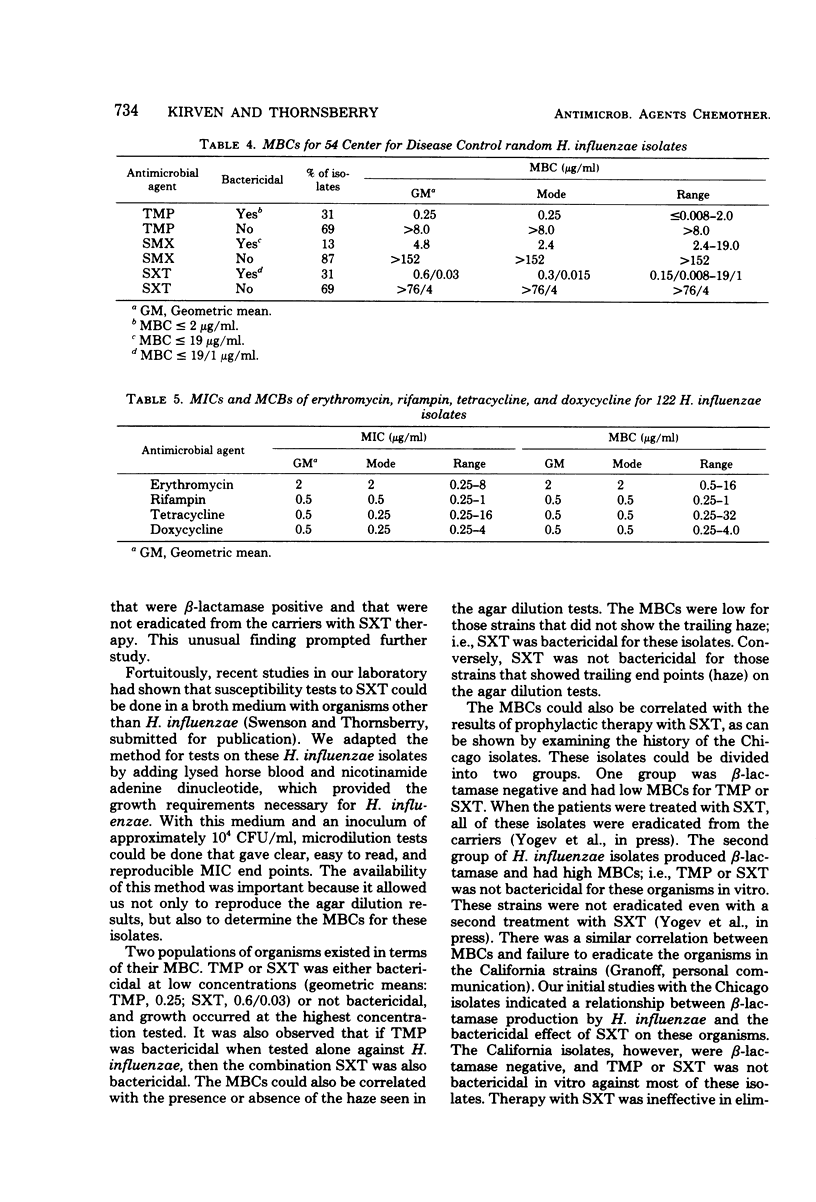

The inability of sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SXT) to eradicate Haemophilus influenzae nasopharyngeal carriage in all asymptomatic patients in closed populations was examined in vitro. A broth medium was adapted for susceptibility testing of H. influenzae which permitted us to determine minimum inhibitory concentrations and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs). The minimum inhibitory concentrations were all low, but the MBCs were bimodally distributed. Trimethoprim alone or the combination SXT either was bactericidal for H. influenzae isolates at low concentrations (i.e., low MBCs) similar to minimum inhibitory concentrations or showed no bactericidal activity (i.e., high MBCs). If trimethoprim was bactericidal when tested alone against H. influenzae, then the combination SXT was also bactericidal. H. influenzae carriage could not be eradicated from asymptomatic patients with SXT therapy when that combination was not bactericidal for these isolates in vitro. H. influenzae carriage was eradicated from patients when the activity of SXT was bactericidal in vitro. H. influenzae strains that are not killed by trimethoprim or SXT seem to occur at random.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Devine L. F., Johnson D. P., Hagerman C. R., Pierce W. E., Rhode S. L., 3rd, Peckinpaugh R. O. Rifampin. Levels in serum and saliva and effect on the meningococcal carrier state. JAMA. 1970 Nov 9;214(6):1055–1059. doi: 10.1001/jama.214.6.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg C. M., McCracken G. H., Jr, Culbertson M. C., Jr Concentrations of erythromycin in serum and tonsil: comparison of the estolate and ethyl succinate suspensions. J Pediatr. 1976 Dec;89(6):1011–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg C. M., McCracken G. H., Jr, Rae S., Parke J. C., Jr Haemophilus influenzae type b disease. Incidence in a day-care center. JAMA. 1977 Aug 15;238(7):604–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glode M. P., Schiffer M. S., Robbins J. B., Khan W., Battle C. U., Armenta E. An outbreak of Hemophilus influenzae type b meningitis in an enclosed hospital population. J Pediatr. 1976 Jan;88(1):36–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)80723-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEIDY G., HAHN E., ZAMENHOF S., ALEXANDER H. E. Biochemical aspects of virulence of Hemophilus influenzae. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1960 Nov 21;88:1195–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1960.tb20109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May J. R., Davies J. Resistance of Haemophilus influenzae to trimethoprim. Br Med J. 1972 Aug 12;3(5823):376–377. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5823.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]