Abstract

Molecular chaperones are large proteins or protein complexes from which many proteins require assistance in order to fold. One unique property of molecular chaperones is the cavity they provide in which proteins fold. The interior surface residues which make up the cavities of molecular chaperone complexes from different organisms has recently been identified, including the well-studied GroEL-GroES chaperonin complex found in Escherichia coli. It was found that the interior of these protein complexes is significantly different than other protein surfaces and that the residues found on the protein surface are able to resist protein adsorption when immobilized on a surface. Yet it remains unknown if these residues passively resist protein binding inside GroEL-GroEs (as demonstrated by experiments that created synthetic mimics of the interior cavity) or if the interior also actively stabilizes protein folding. To answer this question, we have extended entropic models of substrate protein folding inside GroEL-GroES to include interaction energies between substrate proteins and the GroEL-GroES chaperone complex. This model was tested on a set of 528 proteins and the results qualitatively match experimental observations. The interior residues were found to strongly discourage the exposure of any hydrophobic residues, providing an enhanced hydrophobic effect inside the cavity that actively influences protein folding. This work provides both a mechanism for active protein stabilization in GroEL-GroES and a model that matches contemporary understanding of the chaperone protein.

Introduction

Some of the most remarkable processes in nature are those that do not involve specific molecules, but instead have variability in the component molecules: many types of proteins may be synthesized with the same transcription-translation mechanism, DNA may be replicated irrespective of its sequence, and most proteins have a folded state. These processes are nonspecific in the sense that they do not depend on the exact structure or sequence of the component molecules. One of these nonspecific effects is that nearly all proteins have a funnel-like free-energy surface that gives them a well-defined structure (1). The nonspecificity of protein folding is not an abstract concept either; there are compounds—for example, osmolytes—that can both destabilize and enhance folding, independent of the protein identity (2).

The stabilizing effect of molecular chaperones on proteins is another important example of such a nonspecific process. These molecular complexes are able to nonspecifically help proteins fold or correct their misfolding. They contact many protein types and reversibly bind with them while stabilizing their folding (3). This property of nonspecifically resisting irreversible binding with the proteins to be folded is sometimes called “non-stick” (4). The most well-characterized chaperone protein is the GroEL-GroES complex found in Escherichia coli from the chaperonin family. This large complex has a sevenfold symmetry, and may be described as a macromolecular machine (3). Briefly, misfolded substrate proteins bind to the interior cavity of GroEL followed by the binding of GroES, a protein cap that encases the substrate protein inside a chamber. Seven ATP molecules bind to the complex and it undergoes a conformational change that affects the interior cavity conformation. The substrate protein then attempts to refold in the cavity until ATP hydrolysis, after which GroES unbinds, the substrate protein unbinds, and the cycle begins anew—either with the same protein because it failed to refold correctly, or with another protein (5).

This description is a simplification of a relatively complicated process, and there are open questions about this process. For example, it is unknown how deterministic the process is (6). In addition, it is unknown if the protein refolding is actively encouraged by changing the folding free energy, or if GroEL-GroES simply gives proteins another chance to fold free of other macromolecules interfering. A few recent reviews have been written on the topic (3,7).

Recent research has quantified the interior cavity surface of GroEL-GroES along with four other molecular chaperones (8). It was found that these interior surfaces have a high amount of lysine and glutamic acid. Furthermore, when these two particular amino acids are used to create a surface, proteins are unable to irreversibly adsorb onto the surface, providing direct experimental evidence for the nonstick property of molecular chaperones. However, some outstanding questions remain:

Is the resistance of protein adsorption a passive effect that allows proteins to fold free of the interference of other macromolecules, or are proteins actively stabilized?

Can a molecular chaperone actively interact nonspecifically to stabilize protein folding?

In this work, we show that a simple model of interactions between proteins and the GroEL-GroES interior captures the trends observed in experiment. The model demonstrates that it is possible for GroEL-GroES to nonspecifically assist the folding of a large number of proteins through changes to the free energy of protein folding in its interior cavity. The mechanism of this stabilization is the enhancement of the hydrophobic effect inside the cavity; GroEL-GroES strengths the energetic difference between having hydrophobic groups exposed on the surface and having polar groups exposed.

In addition to enlightening the role of nonspecific interactions in biological systems, there is an interesting connection between surfaces that resist nonspecific protein adsorption and molecular chaperones. Nonspecific protein adsorption affects biosensors, biomedical implant coatings, and even marine coatings of commercial ships (9), where the prevention of nonspecific protein adsorption is essential. As mentioned above, molecular chaperones provide a naturally occurring example of resisting protein adsorption. They contact many misfolded protein types, yet the molecular chaperones are able to unbind them. Thus, a better understanding of GroEL-GroES can directly apply to the creation of new materials that resist nonspecific protein adsorption.

There has been previous research into molecular simulations of specific proteins in GroEL-GroES models (10,11). Such research can be used to test scaling arguments or validate other models that generalize too many proteins. In this work, we exploit the lack of specificity in GroEL-GroES to make a model simple enough to be independent of the folding details of substrate proteins enclosed by GroEL-GroES yet accurate enough to match contemporary experimental understanding. This avoids the nearly impossible molecular simulations necessary to consider fully atomistic protein folding inside the GroEL-GroES complex. The model developed in this work treats proteins at a simple level, which enables analysis of the folding of hundreds of proteins in GroEL-GroES. Confinement effects are included to determine which effects are most important, and because confinement has been proposed as the mechanism of action for the folding assistance of proteins (12).

This work can be divided as follows. In Methods and Model, we develop our model of protein folding inside the GroEL-GroES system. In Results, we describe our model results on proteins found in E. coli and optimize the model to predict a hypothetical best GroEL-GroES interior surface and compare this to the molecular chaperones found in other organisms. In Discussion and Experimental Comparisons, we compare the model results with experiments and discuss its implications for designing protein resistant materials. We then present our Conclusions.

Methods and Model

The Protein DataBank (PDB) codes and data used are available at http://sqlshare.escience.washington.edu (13). The E. coli data are split into three tables: “ecoli_nogaps_1.csv”, which contains the per protein data; “ecoli_nogaps_2.csv”, which contains the per residue data; and “ecoli_backbone_contacts.csv”, which contains the data used to calculate the interactions energies. The E. coli proteins were selected from the Protein DataBank (PDB) with the following stipulations:

-

---

homolog cutoff of 40%;

-

---

x-ray resolution <2.5 Å;

-

---

“mutant” must not appear in the title;

-

---

no large ligands (e.g., DNA, RNA);

-

---

the only macromolecule in the structure is a protein;

-

---

the number of residues is >100; and

-

---

no gaps within a chain can appear in the structure.

The statistical analysis was done using the R Statistics Language and Program (14). A residue was classified as on the surface when its surface area is 30% of its maximum surface area. The choice of 30% is commonly used and, in general, residues that are buried have no surface area so the results are relatively insensitive to cutoffs between 10 and 50% (see the Supporting Material) (8,15). Surface area was calculated using accessible surface area (16). The maximum surface area for a given residue was defined as the surface area occupied by the side-chain atoms of a free Gly-X-Gly peptide, with X being the residue of interest. The backbones were taken to be α-helical and the lowest energy χ-rotamers were used (17) for these tripeptides. Once the surface residues are identified, the surface residue fractions, pif, can be calculated for each protein, which are used in the model.

The algorithm describing the identification of interior surface residues of the GroEL-GroES complex can be found in the Supporting Material. The radii of gyration for the GroEL trans and GroEL-GroES cis conformations were calculated from the C-α carbons from residues that were identified as interior. The characteristic lengths for these two conformations are 29.96 and 46.4 Å for cis and trans conformations, respectively. The number of residues used in the model calculations was taken from the ATOM lines in the PDB files. This number was used for the calculation of the random-coil radius of gyration.

Model description

A model is developed here which describes the influence of GroEL-GroES on protein folding. There have been previous efforts to quantify the influence of molecular chaperones on protein folding (18,19). Here, we extend these entropy-based arguments to include an enthalpy term derived from the distribution of residues from White et al. (8). In that work, the fractions of each amino acid found on the interior cavities of molecular chaperones was calculated. This quantitative model can provide folding free-energy perturbations (ΔΔA) which describe the effect of encapsulation in GroEL-GroES on protein folding using the knowledge of this residue distribution and the radii of the protein and GroEL-GroES. The folding free-energy perturbation may also be interpreted as a type of free-energy excess function, which quantifies the difference between folding free energy in the ideal case (no chaperone) and with chaperone. This term includes both the entropic confinement effects and energetic interactions between amino acids. There are some features that are lacking from this model, among which the most important are considering clusters of residues (e.g., a hydrophobic patch), the flexibility of GroEL, and the kinetics of this process. This model is only parameterized for E. coli GroEL-GroES, which will be referred to in this article as “GroEL-GroES”. We begin with the expression of free energy of protein folding,

| (1) |

where the degree mark (°) indicates without the influence of GroEL-GroES. We will use a simple two-state model for protein folding, where the first state is all unfolded conformations, represented by a random coil state, and the second state is the folded conformation. The entropic effect of confinement on the folded state is considered to be negligible due to that state’s collapsed conformation. The entropic effect of confinement on the unfolded state inside GroEL-GroES is described by a scaling exponent from Takagi et al. (18), who used a Gō-like model to evaluate scaling arguments for spherical confinement. The entropic effect on folding is given by

| (2) |

where Sfold is the folded state entropy with GroEL-GroES; S°fold is the folded state entropy without GroEL-GroES, and likewise for the unfolded state (coil); L is the characteristic size of the confinement, which is the radius of the GroEL-GroES cavity; k is the Boltzmann’s constant; Rg is the random coil radius of gyration; and 3.25 comes from Takagi et al. (18). The confinement effect is positive because the unfolded protein state cannot occupy conformations that are larger than the cavity. For GroEL, the confinement of the substrate protein is modeled as a random coil in cylindrical confinement, which changes the exponent to 5/3 from 3.25 (20). The value Rg for random-coil state proteins is given by

| (3) |

where ν was shown to be 0.6 by Kohn et al. (21), N is the number of amino acids, and l is the Kuhn length, which was estimated to 1.93 Å for a large collection of proteins (21).

The internal energy perturbation comes from interactions between the proteins and the interior surface of the GroEL-GroES complex. It is given by

| (4) |

where E is the interaction energy between the protein and chaperone, given by

| (5) |

where Ns is the number of residues on the surface, pi is the fraction of residue type i on the surface of the protein, χij is the energy of the interaction between residues of type i and type j, and pgj is the fraction of residues of type j on the interior surface of the GroEL-GroES complex. The pgj values were calculated as described in White et al. (8). In that work, surface residues were identified by measuring their accessible surface area (16) and the interior surface residues of GroEL-GroES were identified using a geometric algorithm. The value Ns is used because we assume the number of interactions to be equal to the number of surface residues. This assumes there are not multiple interactions and that the number of chaperone residues is large enough that they do not limit the interactions.

The interaction energies, χij, are the only energy terms in the model. Thus, all of our energy values depend on the accuracy of these interaction energy terms. These values were derived using the knowledge-based or quasichemical approach, which is employed in protein structure prediction, among other fields (22). The process uses experimental crystallography data and is described in the Supporting Material. The last term is pi, the fraction of each amino acid. This was calculated for the folded state by tabulating the residues present on the surface of a protein according to White et al. (8). The unfolded state’s residue distribution is assumed to be the same as the whole-protein residue fractions. A more sophisticated model would consider the influence of the chaperone on the unfolded residue distribution, which would likely lower the magnitude of the change in interaction energy between folded and unfolded proteins. However, such a model would inevitably involve simulating protein geometry and greatly complicate the model. The collection of pi values will be called the residue distribution.

Equations 2–5 can be combined into Eq. 1 and rearranged to give

| (6) |

where the f indicates the folded state, u indicates the coil state, and the Rfg/Rug term is due to the change in the number of surface residues in the unfolded state and is described in the Supporting Material.

Results

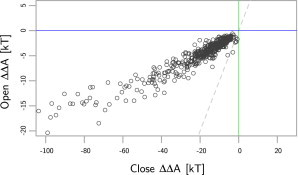

The model results from a sample of E. coli proteins are shown in Fig. 1. The x axis shows the free energy of folding perturbation (ΔΔA) due to confinement in the closed, or cis, GroEL-GroES complex and the y axis shows ΔΔA for the open, or trans, GroEL protein. The two deltas indicate free-energy perturbations to free-energy differences, specifically perturbations to the free-energy difference upon protein folding. As expected, all the points are on the left of the green line, meaning all proteins examined are stabilized by the closed form of the GroEL-GroES complex. This is essential for a model of GroEL-GroES. The median ΔΔA for the closed GroEL-GroES complex is −14.8 kT, or −36.9 kJ/mol at 300 K (0.10 kJ/mol·residue). The dashed gray line separates those proteins that are stabilized more by the open form from those that are stabilized more by the closed form.

Figure 1.

The model results of 528 E. coli proteins. The y axis is the predicted folding free-energy perturbation from the open or trans GroEL complex. A negative number indicates stabilization. The x axis indicates the perturbation from the closed or cis GroEL-GroES complex. Most hypotheses of the GroEL-GroES complex action predict that the closed form should be the most stabilizing, which is indeed observed for the majority (98%) of the proteins (seen above the dashed line).

As seen in the plot, most proteins are stabilized more by the closed form because they lie above that line. A few small proteins near the origin lie below this line. This matches the mechanism for GroEL-GroES (23), which shows that the model performs well. The median change in ΔΔA between the closed and open forms of GroEL is −10.5 kT or −26.2 kJ/mol at 300 K. The blue line indicates which proteins have a stabilized fold when encapsulated by the open form. The proteins are weakly stabilized by the open form; all the points lie below the blue line. This does not follow the expected mechanism for GroEL, which should show positive ΔΔA values. GroEL should destabilize proteins; it interacts preferentially with misfolded proteins. This discrepancy is described in detail below. Overall, the model can assign a quantitative free energy to the conformational changes observed between the open and closed forms of the GroEL-GroES complex; it matches what is understood from experiments; and it shows that the closed form of GroEL-GroES stabilizes protein folding.

Arguably, the most well-established hypothesis on the mechanism of action for GroEL-GroES includes a preferential binding of misfolded proteins to GroEL (7,24–26). Our model does not predict that the open form generally stabilizes the unfolded state. The cause of this can be determined by breaking down the model into entropy and internal energy terms as shown in Fig. 2. The open form is indeed energetically destabilizing, as indicated by the positive values for the internal energy. However, the entropy is stabilizing in the open form. This is due to the small size of the open form, especially relative to the closed form of GroEL-GroES. The characteristic open length is 29.96 Å, compared with 46.4 Å for the closed form. The preferential binding of a misfolded protein may still occur because the hydrophobic regions exposed while unfolding may be the only part of a substrate protein sequestered in the open form, whereas the remaining residues are outside. Or, more likely, the two-state model is an oversimplification. Many of the misfolded protein conformations may be smaller than the random coil state yet still have hydrophobic residues exposed. Such conformations would indeed bind more favorably to GroEL than the native conformations. Their smaller size would decrease the magnitude of confinement, yet the misfolded conformations would still interact favorably with the GroEL residues, which favorably interact with unfolded residue distributions.

Figure 2.

The folding free-energy perturbation from the GroEL trans or open form. The contribution to the folding free-energy perturbation from the change in internal energy is plotted on the y axis. The internal energy is nearly always positive, indicating all proteins are energetically destabilized in the closed form. The entropy or confinement contribution to the folding free-energy perturbation is shown in the x axis. It is negative for most of the proteins. (Points below the dashed lines) These are stabilized more by confinement than they are destabilized by internal energy.

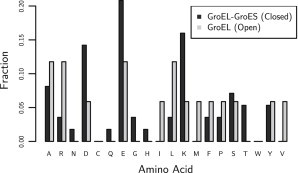

It is important that the model does predict that proteins will be energetically perturbed toward unfolding in the open form from the interaction energy. The cause for the difference in interaction energies between the open and closed forms is from the residue distribution, which is shown in Fig. 3. There is a large change in the number of hydrophobic residues and charged residues. The leucine and isoleucine perturb proteins toward unfolding, whereas aspartic acid, glutamic acid, and lysine strongly perturb proteins toward folding (see Table S2 in the Supporting Material). Another interesting feature to note is the exchange of arginine with lysine between the two distributions. Lysine is more stabilizing than arginine (see Table S2).

Figure 3.

The residue fractions for the open or trans GroEL conformation (N = 394) and the closed or cis GroEL-GroES complex (N = 119). The key feature here is which residues change. There is a higher fraction of charged residues in the closed form; the open form does have more hydrophobic residues, specifically leucine, isoleucine, valine, and methionine.

The effects of confinement and the cavity surface in the closed form can be compared by again breaking the model equations into entropy and internal energy terms, as shown in Fig. 4. The effect of confinement, or entropy, on the folding free-energy perturbation is plotted on the x axis; the effect of the cavity surface, or internal energy, is plotted on the y axis. This plot shows that the internal energy is more important at the smaller protein sizes, where confinement has a negligible effect. The exponent on the entropy term, however, causes the term to grow quickly as the radius of gyration of the random-coil state increases. This causes the trend to curve at the bottom of the plot. The dashed line indicates the separation between proteins that are stabilized more by entropy and those that are stabilized by internal energy. In general, the proteins are more stabilized by the internal energy due to interactions between the proteins and the surface of the cavity.

Figure 4.

The folding free-energy perturbation from the GroEL-GroES cis or closed form. The contribution to the folding free-energy perturbation from the change in internal energy is plotted on the y axis. The internal energy is nearly always negative, indicating nearly all proteins are energetically stabilized in the closed form. The entropy or confinement contribution to the folding free-energy perturbation is shown in the x axis. It is negative for all of the protein. (Points above the dashed lines) These points are stabilized more by confinement than the internal energy, which is rare except for the larger proteins. Note that proteins that cannot fit into the GroEL-GroES complex whereas folded are not included in this analysis.

The reason for this strong effect is the high number of charged residues on the interior cavity. Charged residues enhance the hydrophobic effect through their unfavorable interactions with hydrophobic groups. Aspartic acid in particular has the most unfavorable interactions with hydrophobic groups followed by asparagine and glutamic acid (see Table S2). Equally important is that the charged residues have favorable interactions with charged and polar residues, which are most common on the surface of proteins (8). In particular, lysine is the most common residue found on the surface of E. coli proteins, and thus aspartic and glutamic acid, which interact very favorably with lysine, have a very low interaction energy with the surface of proteins (see Table S2). This effect of internal energy and the role of the interior cavity of the GroEL-GroES complex is still an open question, with much of the recent discussion in literature focused on the role of water (27–30). Water is included implicitly in our model through the residue-residue interaction terms, which come from experimental crystal structures containing water. The internal energy effect on protein folding is a nonspecific effect and independent of the geometry of interactions.

Ideal cavity surface

Now that it is possible to quantify folding free-energy perturbations, we can treat the interior surface of the GroEL-GroES complex as a design variable in order to maximize the magnitude of the folding free-energy perturbation. That is, we may consider an idealized GroEL-GroES where all residues are alchemically transformed to give an ideal residue distribution. This will demonstrate which residues are most important in stabilizing proteins in GroEL-GroES. The geometry of the cavity will not change in this analysis, only the residue identities. The model equations are linear in the residue fractions of the GroEL-GroES surface (Eq. 6) and the fractions are bound between 0 and 1. The extreme values of the model thus occur when any residue fraction is 1 and the others are 0. This is plotted in Fig. 5, where the x axis labels indicate which residue fraction is 1 (with all others being 0) and the y axis is the median ΔΔA. For example, the bar labeled D shows what the median free energy of the 528 E. coli proteins would be if every residue on the interior surface GroEL-GroES were replaced with aspartic acid. Aspartic acid is the most stabilizing residue, followed by asparagine. Their median ΔΔA values are −27.6 and −23.1 kT, respectively. The actual GroEL-GroES residue fraction has a median ΔΔA value of –14.8 kT, which is shown in the horizontal dashed line.

Figure 5.

Extreme values for the model as the residue fractions are changed to single components, where the fraction is 1 for one residue type and 0 for all others. The median folding free-energy perturbation as predicted by the model from GroEL-GroES on 528 E. coli proteins is shown on the y axis. The x axis is the single residue type, which is maximal. For example, the A indicates that only alanine is present on the surface of the GroEL-GroES and the bar height is the median folding free energy for E. coli proteins if only alanines were present in GroEL-GroES. The plot shows that the isoleucine destabilizes proteins the most, along with other hydrophobic residues as expected. Aspartic acid is the most stabilizing residue, followed by asparagine, glutamic acid, and lysine. Cysteine is not expected to be stabilizing or destabilizing due to its unique disulfide bonding.

After aspartic acid and asparagine comes glutamic acid, lysine, and arginine, meaning four of the five most stabilizing residues are charged. The charged residues are the most important for stabilizing protein folding. Therefore, the high number of charged residues seen in chaperone proteins is not so unexpected. The reason for charged residues being so stabilizing is that they have the largest difference in interaction energies between a folded and unfolded protein (see Table S2). Among the uncharged residues, asparagine is the most stabilizing. Asparagine is similar in geometry to aspartic acid but contains an amide functional group. We can gain some insight into the effect of the negative charge by examining the difference between aspartic acid and asparagine. Specifically, asparagine has more favorable interactions with hydrophobic residues (0.25 vs. 0.49 kT) and much more favorable interactions with aromatic residues (0.06 vs. 0.22 kT) (see Table S2). Thus, the negative charge seems to repel aromatic groups and hydrophobic residues slightly more, which are more common on the interior of proteins as opposed to their surface. As expected, the residues that most perturb folding free energies away from folding are the hydrophobic residues: valine, leucine, and isoleucine.

The mutations between the Thermus thermophilus and E. coli GroEL-GroES complex (8) can be better understood from the results described above and those shown in Fig. 5. The large increase in lysine and glutamic acid relative to E. coli GroEL-GroES stabilizes protein folding more inside the T. thermophilus GroEL-GroES complex. There is a corresponding decrease in alanine, glycine, proline, serine, threonine, leucine, and isoleucine on the surface. All those residues stabilize protein folding less than glutamic acid and lysine, or else they destabilize protein folding. There is a decrease in aspartic acid as well, though it is small in comparison to the increase of the other charged residues.

Discussion and Experimental Comparisons

There is debate in the study of molecular chaperone proteins about whether they directly perturb the free energy of folding for a protein (7). Some researchers have argued that the mechanism of GroEL-GroES may be explained without GroEL-GroES stabilizing the protein folding (31). It is clear that it is possible to stabilize a protein fold through nonspecific interactions. For example, osmolytes can accomplish this. Further, there exists a general residue distribution on the surface of proteins and on the interior of proteins (8). It is possible for a surface to create favorable interactions with those residues and thus nonspecifically make a folded state more favored than an unfolded state. Alternatively, a surface may have strongly unfavorable interactions with those residues that are not seen on the surface of proteins (hydrophobic residues). Therefore, it is possible for the cavity of GroEL-GroES to stabilize protein folding via its surface chemistry. It would be surprising if nature did not make use of this. The model presented here shows that the effect is significant: the folding free-energy perturbation is 10 kJ/mol per 100 residues. Additional evidence for this can be seen from the fact that the interior cavity of GroEL-GroES is unlike what is typically seen on the surface of E. coli proteins. There is a folding free-energy perturbation from GroEL-GroES.

There is a remaining question of why aspartic acid is less common than glutamic acid inside the chaperone cavities. However, this is not always the case; for example, a group II chaperonin protein isolated from Methanococcus maripaludis (32) has slightly more interior aspartic-acid than glutamic acid (8). However, generally glutamic acid is present in more than double the amount of aspartic acid. The two acids have similar hydration free energies (33), similar interaction energies, and size. A difference that may explain the preference of GroEL-GroES for glutamic acid is that glutamic acid interacts less than aspartic acid (8). Essentially, aspartic acid has more protein-stabilizing interactions, given that it is interacting, but glutamic acid interacts less while still having stabilizing interactions.

The effects of confinement have been studied experimentally through tail-multiplication studies (31,34). A Gly-Gly-Met tail found at the C-terminal of WT-GroEL-GroES may be extended to decrease the volume of the closed conformation by ∼4% per tail multiplication. At four tails, a drastic decrease in activity is observed for large and small substrate proteins, though the effects at shorter tail-lengths are imperceptible (31). The change in entropy predicted from the model for these tail multiplication studies is approximately the same as the change in volume

Thus, even at four tails, the effect on entropy is modest, with a 13% decrease. This is supported from the results of Farr et al. (31), which showed most of the change in GroEL-GroES activity for the four-tail GroEL-GroES mutants is due to changes in ATPase activity. Thus, the magnitude of confinement in our model is consistent with experiments.

There have been experiments exploring the hydrophilic character of the interior cavity of GroEL-GroES through mutations (31,35). Most mutations that affect only the closed GroEL-GroES conformation have shown negligible effects on the activity of GroEL-GroES (4), with the exception of two mutations that created a net neutral charge for the interior cavity (35). Our model is unable to account for the loss of activity when the interior cavity becomes neutral; those particular results may be due to a change in the structure of GroEL-GroES or some other large-scale effect. Neglecting these two mutation results, the other 11 mutation sets referenced were all without effect in experiments. According to the model, two of the most mutated variants have median folding free-energy perturbations of −13.3 and −14.7 kT for the E252A/D253A/E255A mutant and D359N/D361N/E363Q, respectively. These mutations are too slight to overcome the effect of the other charged residues and confinement. According to the model, only drastic mutations may produce an effect without removing the negative charge inside the cavity. Eight lysine-to-leucine mutations and eight aspartic acid-to-leucine mutations would keep the negative charge but strongly increase the folding free-energy perturbations (destabilizing proteins) enough to cause positive folding free energies in 25% of the proteins. Interestingly, mutation counts below that number are still not significant enough to overcome both the other hydrophilic residues’ stabilization and the confinement entropy. Alanine-to-aspartic acid mutations may increase the folding free perturbations (stabilizing proteins), although it is generally difficult to increase wild-type activity.

There are experimental results showing which proteins strictly require GroEL-GroES, so-called Class III proteins (36). Model calculations on Class III proteins which have crystallography structures (see Table S3) produced a higher median free-energy perturbation value of –22.0 kT compared with –14.8 kT for the E. coli dataset. The perturbation is stronger, as expected. Compared to proteins of similar size, though, it is not significantly different. Thus, it appears that their GroEL-GroES dependence is a combination of their higher free energies of folding and stronger effect from GroEL-GroES.

More direct evidence for the role of charged residues and asparagine may be found from experiments studying nonspecific protein adsorption on self-assembled monolayers of oligo-peptides. Glutamic acid and lysine combinations and poly-asparagine have been shown previously to resist irreversible protein adsorption, demonstrating that these residues strongly prefer interacting with protein surfaces (reversible binding) and not all protein residues (irreversible binding) (8,37,38). In fact, these self-assembled monolayers function quite similarly to GroEL-GroES in their ability to bind proteins reversibly. Other research has shown that asparagine and aspartic acid have the lowest nonspecific protein adsorption, following the trend seen in the model (39).

Conclusions

Molecular chaperones have a unique distribution of residues in their interior cavities that have large fractions of charged residues (7,8). In the GroEL-GroES chaperonin found in T. thermophilus, the interior cavity has 70% charged residues (8). The role of these charged residues is to stabilize protein folding inside the chamber by increasing the hydrophobic effect, as demonstrated through the simple model of protein folding inside GroEL-GroES presented here. Thus GroEL-GroES stabilizes a large number of proteins through interactions between protein surfaces and the interior cavity of GroEL-GroES. The median free-energy perturbation on folding free energy in GroEL-GroEL isolated from E. coli is −10 kJ/mol per 100 residues for a diverse sample of 528 E. coli proteins. This model provides predictions that are qualitatively consistent with the hypothesized mechanism of GroEL-GroES and experiments, and captures the behavior of both confinement entropy and energetic effects from the surface chemistry of GroEL-GroES. The residues providing the most protein stabilization are aspartic acid, glutamic acid, asparagine, and lysine, of which lysine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid are present in high amounts on the interior surface of many chaperone proteins (8). This research brings a better understanding of how nature is able to interact nonspecifically with proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bill Howe and Prof. Jim Pfaendtner for providing valuable assistance.

This work was supported by the Office of Naval Research (grant No. N00014-10-1-0600).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Onuchic J.N., Luthey-Schulten Z., Wolynes P.G. Theory of protein folding: the energy landscape perspective. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1997;48:545–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancey P.H., Clark M.E., Somero G.N. Living with water stress: evolution of osmolyte systems. Science. 1982;217:1214–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.7112124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horwich A.L., Fenton W.A., Farr G.W. Two families of chaperonin: physiology and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;23:115–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horwich A.L., Apetri A.C., Fenton W.A. The GroEL/GroES cis cavity as a passive anti-aggregation device. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:2654–2662. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shtilerman M., Lorimer G.H., Englander S.W. Chaperonin function: folding by forced unfolding. Science. 1999;284:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofmann H., Hillger F., Schuler B. Single-molecule spectroscopy of protein folding in a chaperonin cage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:11793–11798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002356107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigler P.B., Xu Z., Horwich A.L. Structure and function in GroEL-mediated protein folding. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:581–608. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White A.D., Nowinski A.K., Jiang S. Decoding nonspecific interactions from nature. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:3488–3494. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang S., Cao Z. Ultralow-fouling, functionalizable, and hydrolyzable zwitterionic materials and their derivatives for biological applications. Adv. Mater. (Deerfield Beach, Fla.) 2010;22:920–932. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan H., Mark A.E. Mimicking the action of GroEL in molecular dynamics simulations: application to the refinement of protein structures. Protein Sci. 2006;15:441–448. doi: 10.1110/ps.051721006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian J., Garcia A.E. Simulation studies of protein folding/unfolding equilibrium under polar and nonpolar confinement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15157–15164. doi: 10.1021/ja2054572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan H.S., Dill K.A. A simple model of chaperonin-mediated protein folding. Proteins. 1996;24:345–351. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199603)24:3<345::AID-PROT7>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howe, B., G. Cole, …, L. Battle. 2011. Database-as-a-Service for Long Tail Science. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Scientific and Statistical Database Management (SSDBM 11). 480–489. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- 14.R Development Core Team. 2011. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. http://www.r-project.org/.

- 15.Andrade M.A., O’Donoghue S.I., Rost B. Adaptation of protein surfaces to subcellular location. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:517–525. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voss N.R., Gerstein M. Calculation of standard atomic volumes for RNA and comparison with proteins: RNA is packed more tightly. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:477–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunbrack R.L., Jr., Cohen F.E. Bayesian statistical analysis of protein side-chain rotamer preferences. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1661–1681. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takagi F., Koga N., Takada S. How protein thermodynamics and folding mechanisms are altered by the chaperonin cage: molecular simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11367–11372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831920100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittal J., Best R.B. Thermodynamics and kinetics of protein folding under confinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20233–20238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807742105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Gennes P.-G. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1979. Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohn J.E., Millett I.S., Plaxco K.W. Random-coil behavior and the dimensions of chemically unfolded proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12491–12496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403643101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyazawa S., Jernigan R.L. Estimation of effective interresidue contact energies from protein crystal structures: quasi-chemical approximation. Macromolecules. 1985;18:534–552. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frydman J. Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:603–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin Z., Rye H.S. Expansion and compression of a protein folding intermediate by GroEL. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zahn R., Plückthun A. Thermodynamic partitioning model for hydrophobic binding of polypeptides by GroEL. II. GroEL recognizes thermally unfolded mature β-lactamase. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;242:165–174. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walter S., Lorimer G.H., Schmid F.X. A thermodynamic coupling mechanism for GroEL-mediated unfolding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9425–9430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stumpe M.C., Blinov N., Pande V.S. Calculation of local water densities in biological systems: a comparison of molecular dynamics simulations and the 3D-RISM-KH molecular theory of solvation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:319–328. doi: 10.1021/jp102587q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernández A., Scheraga H.A. Insufficiently dehydrated hydrogen bonds as determinants of protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:113–118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136888100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada T., Fujiyoshi Y., Shichida Y. Functional role of internal water molecules in rhodopsin revealed by x-ray crystallography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:5982–5987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082666399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhee Y.M., Sorin E.J., Pande V.S. Simulations of the role of water in the protein-folding mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:6456–6461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307898101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farr G.W., Fenton W.A., Horwich A.L. Perturbed ATPase activity and not “close confinement” of substrate in the cis cavity affects rates of folding by tail-multiplied GroEL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5342–5347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700820104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira J.H., Ralston C.Y., Adams P.D. Crystal structures of a group II chaperonin reveal the open and closed states associated with the protein folding cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:27958–27966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.125344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolfenden R., Andersson L., Southgate C.C. Affinities of amino acid side chains for solvent water. Biochemistry. 1981;20:849–855. doi: 10.1021/bi00507a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Y.-C., Chang H.-C., Hayer-Hartl M. Structural features of the GroEL-GroES nano-cage required for rapid folding of encapsulated protein. Cell. 2006;125:903–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y.-C., Chang H.-C., Hayer-Hartl M. Essential role of the chaperonin folding compartment in vivo. EMBO J. 2008;27:1458–1468. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerner M.J., Naylor D.J., Hartl F.U. Proteome-wide analysis of chaperonin-dependent protein folding in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2005;122:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nowinski A.K., Sun F., Jiang S. Sequence, structure, and function of peptide self-assembled monolayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:6000–6005. doi: 10.1021/ja3006868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S., Cao Z., Jiang S. Ultra-low fouling peptide surfaces derived from natural amino acids. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5892–5896. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolduc O.R., Masson J.-F. Monolayers of 3-mercaptopropyl-amino acid to reduce the nonspecific adsorption of serum proteins on the surface of biosensors. Langmuir. 2008;24:12085–12091. doi: 10.1021/la801861q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guttorp P. Chapman and Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1995. Stochastic Modeling of Scientific Data. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.