Abstract

Research on cancer epigenetics has flourished in the last decade. Nevertheless growing evidence point on the importance to understand the mechanisms by which epigenetic changes regulate the genesis and progression of cancer growth. Several epigenetic targets have been discovered and are currently under validation for new anticancer therapies. Drug discovery approaches aiming to target these epigenetic enzymes with small-molecules inhibitors have produced the first pre-clinical and clinical outcomes and many other compounds are now entering the pipeline as new candidate epidrugs. The most studied targets can be ascribed to histone deacetylases and DNA methyltransferases, although several other classes of enzymes are able to operate post-translational modifications to histone tails are also likely to represent new frontiers for therapeutic interventions. By acknowledging that the field of cancer epigenetics is evolving with an impressive rate of new findings, with this review we aim to provide a current overview of pre-clinical applications of small-molecules for cancer pathologies, combining them with the current knowledge of epigenetic targets in terms of available structural data and drug design perspectives.

Keywords: Epigenetics, anticancer therapy, DNA methyltransferases, protein methyltransferases, demethylases, deacetylases, acetyltransferases, histone post-translational modifications, drug design, crystallography, small-molecule inhibitors.

1. INTRODUCTION

The term epigenetics currently refers to the mechanisms of temporal and spatial control of gene activity that do not depend on the DNA sequence, influencing the physiological and pathological development of an organism. The molecular mechanisms by which epigenetic changes occur are complex and cover a wide range of processes including paramutation, bookmarking, imprinting, gene silencing, carcinogenesis progression, and, most importantly, regulation of heterochromatin and histone modifications [1]. At a biochemical level, epigenetic alterations in chromatin involve methylation of DNA patterns, several forms of histone modifications and microRNA (miRNA) expression. All these processes modulate the structure of chromatin leading to the activation or silencing of gene expression [2-6]. More specifically, the chromatin remodeling is accomplished by two main mechanisms that concern the methylation of cytosine residues in DNA and a variety of post-translational modifications (PTMs) occurring at the N-terminal tails of histone proteins. These PTMs include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, sumoylation, glycosylation, ADP-ribosylation, carbonylation, citrullination and biotinylation [7,8]. Among all PTMs for example, histone tails can have its lysine residues acetylated, methylated or ubiquitilated; arginine can be methylated; serine and threonine residues can be phosphorylated [9-17]. These covalent modifications are able to cause other PTMs and the ensemble of this cross-talk is known as the histone code, which can be positively or negatively correlated with specific transcriptional states or organization of chromatin [11,18-20]. The fine regulation of histone PTMs and DNA methylation is controlled and catalyzed by many different classes of enzymes whose existence and functions have been elucidated with an extraordinary progression in the last decade [12,20-25]. Epigenetic modifications are reversible nuclear chemical reactions that are due to enzymes able to exercise opposing catalytic effects [5,20]. Along with metabolism [26-28] and regulation of the immune system [29,30], epigenetic changes are at the limelight of cancer research. Many studies have found that alterations in the epigenetic code may contribute to the onset of growth and progression of a variety of cancers [20,21,23,31-41]. For this reason, these enzymes are attractive therapeutic targets for the development of new cancer therapies [3,42-45].

In this review we aim to present and discuss the relationship of the available information on epigenetic targets related to cancer pathologies and their structural data describing also the perspective for considering these enzymes as new targets for anticancer drug discovery initiatives.

2. EPIGENETIC IN CANCER DISEASES

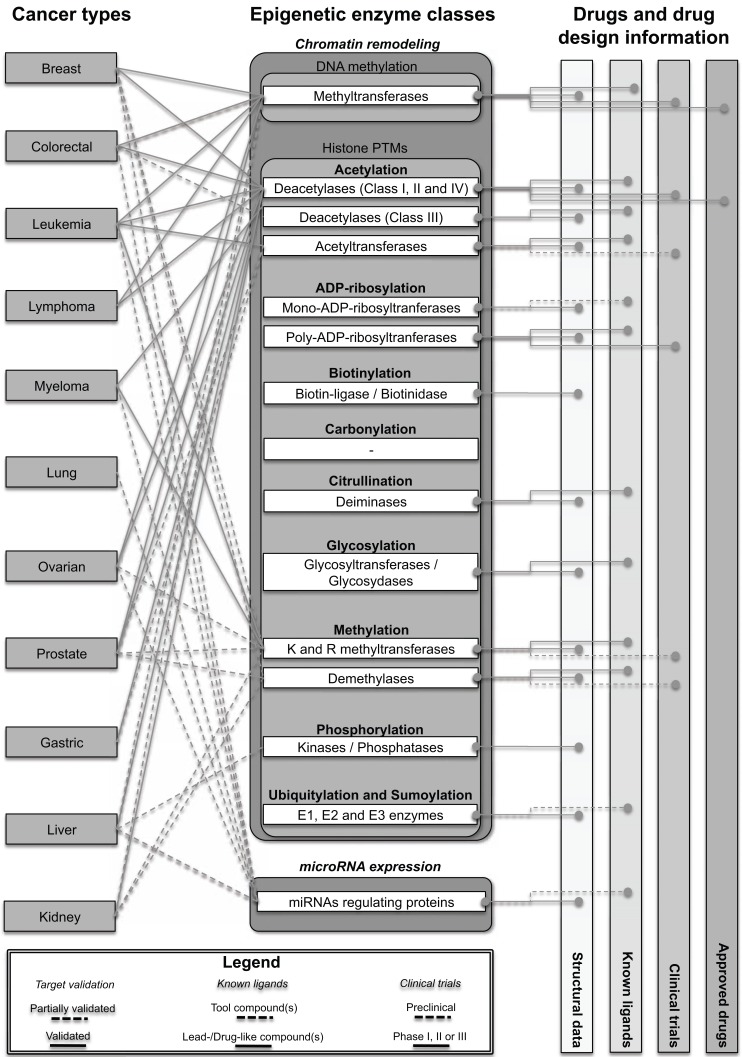

Although in the last decade several cancer pathologies have been associated to specific epigenetic changes, the way in which epigenetic modifications are regulated is still largely unknown. In this section we describe the current knowledge linking various cancer types with epigenetic targets, considering that demonstrated cause-consequence might not necessarily indicate that these targets are validated for anticancer drug design purposes. In (Fig. 1) we summarized the connections between the most important cancer diseases and the various classes of epigenetic targets, associating them to relevant drug discovery information.

Fig. (1).

Connections between classes of epigenetic targets with cancer diseases and drug discovery information. Known ligands, clinical trials and approved drugs refer to cancer therapies with mechanisms of action directly related to epigenetic targets. Clinical trials and approved drugs have been recently reviewed in [46].

Breast Cancer

Epigenetic alterations such as DNA methylation and chromatin remodeling play a significant role in breast cancer development and, although extensive research has been done, the causes, mechanisms and therapies of breast cancer are still to be fully elucidated [47-50]. Epigenetic changes in different classes of this type of cancer have been studied, including: estrogen receptor positive (ER+), that are estrogen-level dependent; estrogen receptor negative (ER-), whose tumor cells are not responsive to estrogen thus resistant to antiestrogenic drugs such as tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors; progesterone receptor (PR); and human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2)-related cancers [49,51-58]. A number of genes has been identified to be aberrantly methylated in breast cancer and their number is rapidly growing [48,56,59]. Likewise, altered expression of micro RNAs has been found to regulate key genes in the development of breast cancer [59-62]. Biological rationales for breast cancer therapies have been deeply studied by inhibiting DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) and histone deacetylases (HDAC) proteins. Furthermore, several epigenetic-based synthetic drugs, which can reduce DNA hypermethylation and histone deacetylation, are undergoing preclinical and clinical trials [49,57,63-65]. These epidrugs [55,66] are a promising strategy for breast cancer therapies as they could restore the estrogen receptor α (ERα) activity in ER- cancer patients, reactivating cancer cell growth in an estrogen-dependent manner resulting sensible to antiestrogenic drugs [51,52,55,58,67-69]. Additional studies include epigenetic targets such as methyltransferases [70,71] which are currently in the spotlight of drug discovery programs, not only for breast cancer but also for a number of other conditions [24,41,72-74]. Besides, dietary components like complementary and/or alternative medicines from green tea, genistein from soybean, isothiocyanates from plant foods, curcumin from turmeric, resveratrol from grapes, and sulforaphane from cruciferous vegetables, have been studied for their ability to target the epigenome in relation to breast cancer; nevertheless their mechanisms of action are still poorly characterized [49,66,75-77].

Colorectal Cancer

Extensive loss of DNA methylation has been observed in colon cancer cells almost 30 years ago [78]. Epigenetic abnormalities associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) have been, since then, intensively studied to identify the methylation patterns appearing at the various stages of colorectal cancer progression [79-83]. Frequent targets of aberrant methylation processes and CRC markers have been recently reviewed [84-86]. Epigenetic changes in colorectal cancer have been studied in relation to chromosomal instability [81-83,87], inflammation and microenvironmental role of gut microbiota [88], genetic polymorphism [89] and nutraceuticals [90-92]. In addition, epigenetically modified miRNAs have also been found to play a role in CRC [93,94]. The silencing of some miRNAs is associated with CpG island hypermethylation. The aberrant hypermethylation of two miRNAs (miR-34b/c and miR-148a) has been reported as a possible early screening and disease progression markers.[95] Further investigations identified 35 miRNAs related to colon cancer that were epigenetically silenced and revealed 162 molecular pathways potentially altered by eight methylated/downregulated miRNAs in CRC [61,96]. As major pathways of colorectal carcinogenesis are tightly connected to epigenetic changes, growing evidence shows that the risk of CRC can be influenced by lifestyle and environmental factors [91]. For instance, flavonoids and folates in a human diet have been shown to alter DNA methylation and modify the risk of human colon cancer and cardiovascular diseases, even though these mechanisms are yet to be ascertained.[90,97] Additional researches on the effects of nutraceuticals on epigenetic changes in the intestinal mucosa promise to be relevant for preventive and therapeutic interventions [91]. Pharmacological inhibition of Class I and Class II HDACs and the emerging role of Class III (in particular Sirt1) have been studied for their capacity to induce growth arrest, differentiation and apoptosis of colon cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [98-101]. Consequently, several clinical trials were initiated to repurpose compounds for CRC that were already approved or were in late-stage trials for the treatment of hematopoietic and solid tumors.

Hematological Malignancies

DNA and histone post-translational modifications have been demonstrated to be associated with several mutations in epigenetic targets for different hematologic malignancies [102].

In leukemias the role of different epigenetic enzymes has been investigated mainly for acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) [103,104] and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [103]. Biological players that have been studied for clinical applications include deacetylases [32,105-108], DNA and histone methyltransferases [32,35,103,104,109-125] and miRNA [104,119,126,127]. Besides APL and AML, further data have been collected for leukaemogenesis, including transforming factors and epigenetic alterations [106,111,128-131]. Several small organic molecules have been proposed for clinical use in different leukemia pathologies. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) such as Panobinostat (LBH589), Belinostat (PXD-101), 4SC-202 and AR-42 are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), AML and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [35,104-107,132]. A considerable interest in using HDACis is the study of combined regimens with other agents that can enhance cancer cell lethality. Among those agents there are cyclin-dependent kinase and tyrosine kinase inhibitors as well as Hsp90 and proteasome inhibitors [133,134]. Histone methyltransferases have also been the object of drug design approaches for leukemias. For instance, disruptor of telomeric silencing 1-like (DOT1L) has been discussed as a potential target of for the mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) fusions. The potent SAM-competitive DOT1L inhibitor EPZ004777 was reported together with clinical implications for the personalized treatment of such an aggressive form of leukemia [109,110,113]. In addition, the structure of the newly developed inhibitor GSK2816126 targeting EZH2 for the treatment of AML was unveiled at the 2012 American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting [135]. This compound was found to abrogate histone overmethylation, and the treatment of cell cultures and laboratory animals with this compound demonstrated a reduced proliferation of tumor cells.

The interest in modulating epigenetic enzymes is also rising in the treatment of lymphomas and myelomas, particularly as combination therapies. For instance, HDACi and DNMT inhibitors have been tested for the treatment of aggressive non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas (NHLs) [136-145].

Overall, pre-clinical and clinical studies in hematological malignancies are presently focused on histone deacetylases and DNA methyltransferases, but growing evidence points to the development of therapies that are directed to other classes of epigenetic enzymes, especially histone methyltransferases [146].

Lung

Epigenetic changes in lung cancers contribute to cell transformation by modulating chromatin structure and specific expression of genes; these include DNA methylation patterns, covalent modifications of histone and chromatin by epigenetic enzymes, and micro-RNA. All these changes are involved in the silencing of tumor suppressor genes and enhance the expression of oncogenes [147-152]. Genome-wide technologies and bioinformatics studies demonstrated that global alterations of histone patterns are linked to DNA methylation and are causal in lung cancer [153,154]. These techniques were also used for the prediction of specific miRNAs targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in lung cancer [155]. Many genes were found to be silenced by methylation promoters in lung cancers in response to radiation stimuli [156]. DNA methylation patterns may also predict early recurrence of stage I non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) [149].

As lung cancer is the major cause of cancer death worldwide and the five-year survival is extremely poor, the need of more effective therapeutic agents is of utmost importance [154]. In particular, NSCLCs are relatively insensitive to chemotherapy when compared to small cell carcinomas, so efforts are now directed to the study of the epigenetic changes occurring in these type of cancers and in pulmonary hypertension [154,157]. Restoration of the expression of epigenetically silenced genes with new targeted approaches and combined therapy with azacitidine and entinostat, as well as DNMTi and HDACi, were investigated in phase I/II trials for the treatment of NSCLCs [158-160].

Ovarian

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic cancer. In advanced ovarian and endometrial carcinomas, current therapies that are initially responsive, evolve to a fully drug-resistant phenotype [161,162]. Among the factors that contribute negatively to the progression and therapeutic resistance against ovarian and endometrial cancer, there are several genetic mutations and epigenetic anomalies which are frequent in both malignancies [163-168]. Epigenetic changes include aberrant DNA methylation, atypical histone modifications and unregulated expression of distinct microRNAs, resulting in altered gene- expression patterns favoring cell survival [162, 169,170].

As for other cancer diseases, the therapeutic intervention aimed at reversing oncogenic chromatin aberrations have been primarily studied with DNMTs and HDACs inhibitors [162,168,171,172]. In addition, epigenetic phenomena, in which post-transcriptional gene regulation by small non-coding microRNAs is relevant, have also been investigated. Targeting of specific miRNAs has been performed using antagomir oligonucleotides for both mechanistic studies and investigation of possible in vivo therapeutic applications [170].

Prostate

Prostate cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in men. A rapid increase of the incidence for this cancer is expected as the male population over the age of fifty is growing worldwide. In this cancer, epigenetic alterations appear earlier and more frequently than genetic mutations. Multiple genes silenced by epigenetic alterations have been identified [173]. Several reviews describing epigenetic changes in prostate cancer have been published recently [173-179]. Anti-cancer drug research has been stimulated by the fact that, for patients who are not cured by local treatment and have metastasis, neither androgen ablation nor chemotherapy can abrogate progression. For this reason, finding pharmacological strategies aimed to control prostate cancer initiation and disease progression is still a medical challenge. Several studies connecting prostate cancer and epigenetics include insights into: hypermethylation and hypomethylation patterns [180-184], involvement of histone modifiers such as HDACs, histone acetyltransferases (HATs), protein lysine methyltransferase (PKMTs) [185-187], multicomponent epigenetic regulatory complexes [188-191], new molecular biomarkers and therapeutic implications [192,193] and prevention with dietary components [183,194,195]. Preclinical evidence involving the epigenome as a key mediator in prostate carcinogenesis has entailed initial clinical trials with epidrugs such as HDACs inhibitors [174]. It is expected that future drugs could become useful for new combination regimens aimed at treating prostate cancer.

Gastric

Gastrointestinal (GI) carcinogenesis causes some of the most common types of tumors worldwide, including esophagus, stomach, bowel, and anus. Even thought it has been recognized that the major reason for GI carcinogenesis resides in at least one genetic mutation that either activates an oncogene or inhibits the function of a tumor suppressor gene, recent data indicate that epigenetic abnormalities are critical in regulating benign tumorigenesis and eventual malignant transformation in gastorointestinal (GI) carcinogenesis [196-202]. In particular, aberrant histone acetylation regulated by HATs and HDACs have been linked to gastric cancer [196]. Epigenetic alterations have also been identified in presence of Epstein-Barr virus [203-205], while Helicobacter pylori, which constitutes a main cause of gastric cancer, was shown to reduce HDACs activity. These data suggest that pharmacological actions of HDACi in GI might be detrimental or beneficial depending on the clinicopathological context [206,207]. Despite the fact that various links between GI cancer and HATs and HDACs have been identified, comparing to other cancers, fewer progresses have been reported to treat GI carcinogenesis with epidrugs. A Phase I study has combined Vorinostat with radiotherapy in GI carcinoma [208]. This, as well as other studies, created foundations for additional initiatives to improve the therapeutic potential of HDACi and other epigenetic enzymes for GI tumors [196].

Liver

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) originates from hepatocytes and is the most common liver cancer. Cancer rates and etiology of HCC vary considerably by age, gender, ethnic origin, lifestyle (in particular alcohol abuse [209]) and environmental pollution [210]. Other factors include the infection by hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV) [211,212], exposure to aflatoxins, hypertension and diabetes [210,213]. Both genetic and epigenetic factors form the molecular basis of HCC. Epigenetic alterations may predispose to genetic changes and, vice versa, genetic changes may also initiate aberrant epigenetic modifications [210,213-216]. DNA methylation and various histone modifications, as well as RNA interference, have been reported as epigenetic events contributing to HCC development [210,215,217]. It should be remarked that the use of epigenetic biomarkers for detecting hepatocellular carcinoma has expanded the potential for non-invasive screening of high-risk populations [218]. However, the road to develop small-molecule compounds targeting epigenetic enzymes for HCC cancer treatment is at its beginning. Presently only HDACis have been studied for the treatment of HCC [217,219-221].

Kidney

Kidney cancer accounts for 2% of all adult cancer malignancies and the majority of them (80-85%) are renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) originated from the renal parenchyma. While the direct causes of this type of cancer are still vaguely defined, smoking and chemical carcinogens (e.g. asbestos and organic solvents) have been related to renal tumorigenesis [222]. Furthermore pathologies like obesity, hypertension and the use of antihypertensive medications, have been reported as risk-factors for RCCs [222,223]. Stepwise accumulation of DNA methylation has been observed by comparing normal renal tissues, renal tumor tissues and non-tumor renal tissues of patients with renal tumors [222]. These results highlighted that regional CpG patterns may participate in the early and precancerous stage of renal tumorigenesis. On the contrary, DNA hypomethylation does not seem to be a major event during renal carcinogenesis. DNA methylation alterations at a precancerous stage may further predispose renal tissue to epigenetic and genetic alterations, generating more malignant cancers and even determining the patient outcome [223]. At present there are few clinical trials of Phase I/II for testing inhibitors of HDACs (i.e. LBH-589 and Vorinostat) in advanced RCC [224,225].

3. STRUCTURAL DATA OF EPIGENETIC TARGETS

The research aiming at developing new therapeutic anticancer strategies against epigenetic targets has flourished in the last years. Several review articles recently described rationales, targets, new drugs, approaches, novel compounds and methodologies [12,17,18, 20,22-25,35-41,65,226-229]. A large amount of these insightful articles have been dedicated to well established drug targets such as the histone deacetylases (HDACs) and DNA methyltransferases, and to the status of the development of small-molecule compounds [25,31,45,55,230,231]. However, despite the intensive research effort, molecular processes linking specific epigenetic targets to DNA-dependent biological functions, and their cause-consequence relationships, have been hard to elucidate. Beyond the fairly well characterized epigenetic processes of histone acetylation and methylation, many other PMTs require further biological elucidations, currently collected by many scientists conducting research on cancer epigenetics. In the next paragraphs, we describe classes and families of proteins that have been directly and/or indirectly associated to the modulation of the epigenetic code, taking into account their importance in cancer pathologies. We emphasize that structural information does not imply that these proteins can be considered validated drug targets for anticancer treatments, as other factors need to be considered. Figure 1 provides a graphical view of the information related to these targets. In the next sections we describe in tabular form the ensemble of structural data related to these targets, as suggested by the current state-of-the-art in the field. For additional information, the reader will be referred to other important reviews and articles in each relevant section.

Acetylation

Class I, II and IV Deacetylases

Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) contribute to the regulation of transcriptional activity by catalyzing the hydrolysis of acetyl-L-Lys side chains of histone and non-histone proteins in L-Lys and acetate. By restoring the positive charge of Lys residues, HDAC enzymes reverse the catalytic activity of histone acetyltransferases that will be described below. Deacetylation of histones alters the chromatin structure and represses transcription. Abnormal activity of these enzymes is implicated in several diseases, especially in cancer [20,23,31,98,107,136,159,232-238].

To date, 18 HDACs have been isolated in humans. They are organized into: class I (HDACs 1, 2, 3 and 8), class IIa (HDACs 4, 5, 7 and 9), class IIb (HDACs 9 and 10), class III (designated sirtuins SIRT1 to 7) and class IV (HDAC11). Class III enzymes are NAD+-dependent deacetylases that are catalytically distinct from other HDAC classes, thus they will be discussed in the next paragraph. X-ray crystal structures (Table 1) are available for human HDACs (2, 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8) and for three HDAC-related deacetylases from bacteria, namely, histone deacetylase-like proteins (HDLP), histone deacetylase-like amidohydrolases (HDAH) and acetylpolyamine amidohydrolases (APAH). The first three-dimensional structure of an HDAC-related protein was the histone deacetylase-like protein (HDLP) from Aquifex aeolicus in complex with the inhibitors Tricostatin A and SAHA (Vorinostat) [239]. This data provided the structural basis for the catalytic mechanism and the inhibition of this family of enzymes, paving the way for the design of new bioactive molecules able to interfere with the deacetylation reaction. Several compounds targeting HDACs entered clinical trials in the last year and have been reviewed elsewhere [98,105,139,141,234,237,240-243]. These proteins belong to the open α/β folding class, with an eight-stranded parallel β-sheet sandwiched between α-helices. The active site consists of an extended and tight primarily hydrophobic tunnel with the catalytic machinery located at its end. During the deacetylation reaction the tunnel is occupied by methylene groups belonging to the substrate acetylated Lys, while the acetyl moiety binds a metal ion in the center of the active site. The deacetylase reaction requires a transition metal ion and, although the HDACs are typically considered Zn2+-containing enzymes, the metal ion in the active site, as demonstrated by the X-ray structure of HDAC8, can be substituted by Fe2+, Co2+ and Mn2+ [244]. This is consistent with the hypothesis that HDAC8 could function as a Fe2+-catalyzing enzyme in vivo (Table 1) [245]. The overall fold of other recently crystallized HDACs is similar to the previously reported structures, even if several key features distinguish the various classes. A comprehensive review on these structural aspects has been published by Lombardi et al [246]. Besides the large number of non-mutated X-ray structures of the catalytic domain, often in complex with known inhibitors, three-dimensional structures of other HDAC domains have also been published. In particular, three structures of the zinc-binding domain of HDAC6 and two structures of the glutamine-rich domain of HDAC4, both responsible of protein-protein interactions and formation of large protein complexes, have been solved (Table 1). In addition, the large number of complexes with point mutations in the catalytic domain, especially for HDAC8, HDAC4 and bacterial APAH, highlight the importance of some key residues in the binding of substrate and small-molecule inhibitors.

Table 1.

Available 3D Structure of Human and Bacterial HDACs

| Class | Name | Organism | PDB ID | Ligand | Domain | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | HDAC2 | Homo sapiens | 3MAX | N-(4-aminobiphenyl-3-yl)benzamide | Catalytic Domain | [247] |

| HDAC3 | Homo sapiens | 4A69 | Nuclear receptor corepressor 2 and inositol tetraphosphate | Catalytic Domain | [248] | |

| HDAC8 | Homo sapiens | 1T64 | Trichostatin A | Catalytic Domain | [249] | |

| 1T67 | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 1T69 | SAHA | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 1VKG | Cra-19156 | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 1W22 | Hydroxamic acid inhibitor | Catalytic Domain | [250] | |||

| 2V5W | Acetylated substrate | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | [251] | |||

| 2V5X | Hydroxamic acid inhibitor | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 3EW8 | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | [252] | |||

| 3EWF | Substrate Peptide | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 3EZP | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 3EZT | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 3F06 | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 3F07 | APHA | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 3F0R | Trichostatin A | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 3MZ3 | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain (Co2+) | [244] | |||

| 3MZ4 | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain (Mn2+) | ||||

| 3MZ6 | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain (Fe2+) | ||||

| 3MZ7 | M344 (B3Na) | Catalytic Domain (Co2+) | ||||

| 3RQD | Largazole | Catalytic Domain | [253] | |||

| 3SFF | Aminoacid derived inhibitor | Catalytic Domain | [254] | |||

| 3SFH | Aminoacid derived inhibitor | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| IIa | HDAC4 | Homo sapiens | 2H8N | Glutamine Rich Domain | [255] | |

| 2O94 | Glutamine Rich Domain | |||||

| 2VQJ | Trifluoromethylketone inhibitor | Catalytic Domain | [256] | |||

| 2VQM | Hydroxamic acid inhibitor | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 2VQO | Trifluoromethylketone inhibitor | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 2VQQ | Trifluoromethylketone inhibitor | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 2VQV | Hydroxamic acid inhibitor | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 2VQW | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | |||||

| HDAC7 | Homo sapiens | 3C0Y | Catalytic Domain | [257] | ||

| 3C0Z | SAHA | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 3C10 | Trichostatin A | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| IIb | HDAC6 | Homo sapiens | 3C5K | Zinc Finger Domain | ||

| 3GV4 | Ubiquitin C-terminal peptide | Zinc Finger Domain | ||||

| 3PHD | Ubiquitin | Zinc Finger Domain | [258] | |||

| Bacterial | HDAH | Alcaligenes sp. | 1ZZ0 | Acetate | Catalytic Domain | [259] |

| 1ZZ1 | SAHA | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 1ZZ3 | CypX | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 2GH6 | Trifluoromethylketone inhibitor | Catalytic Domain | [260] | |||

| 2VCG | ST-17 | Catalytic Domain | [261] | |||

| HDLP | Aquifex Aeolicus | 1C3P | Catalytic Domain | [239] | ||

| 1C3R | Trichostatin A | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| 1C3S | SAHA | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| APAH | Mycoplana ramosa | 3Q9B | M344 | Catalytic Domain | [262] | |

| 3Q9C | N8-acetylspermidine | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 3Q9E | Acetylspermine | Catalytic Domain (mutate) | ||||

| 3Q9F | CAPS | Catalytic Domain | ||||

| Burkholderia pseudomallei | 3MEN | Catalytic Domain | [263] |

PDB ligand ID

Class III Deacetylases (Sirtuins)

Sirtuins represent the class III family of histone deacetylases (HDACs). Structure and function of these proteins differ from other HDACs since sirtuins require NAD+ to catalyze the removal of an acetyl moiety from a Lys residue within specific protein targets, including histone tails. As seen in the previous section, this family of enzymes is largely conserved from bacteria to humans [264] and is involved in important physiological processes and disease conditions including longevity, metabolism and DNA regulation, cancer and inflammation [265,266]. In the last years, the three-dimensional structures of many sirtuin homologs have been solved by X-ray crystallography allowing a better understanding of the catalytic mechanism and specific structural features of this enzyme family (Table 2). The first three-dimensional structure obtained was a Sir2 homolog from A. Fulgidus complexed with NAD+ [267]. This structure provided the first insights into the structural features and catalytic mechanism of sirtuins. Afterward, further details were provided about the active site characteristics, deacetylation reaction and inhibitors/substrate binding as a result of several X-ray structures complexed with different substrates. Examples include: p53 peptides or histone H3/H4 peptides, and different reaction intermediates, like 2-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (see Table 2 for details). The inhibition mechanism of the endogenous regulator nicotinamide, a key step in the development of new sirtuins effectors, was also studied [268,269]. Although a large number of synthetic sirtuins inhibitors and activators are described in literature, only one co-crystal structure reports an inhibitor, Suramin, showing the structural basis for inhibitor binding and allowing the rational design of new and more potent compounds [270]. Several bacterial Sir2 structures and human Sirt2, Sirt3, Sirt5 and Sirt6 are available whereas no structures exist at present for Sirt1, Sirt4 and Sirt7 (Table 2). All these PDB entries contain the catalytic domain, formed approximately by 270 residues, and variable N-terminal and C-terminal regions. The catalytic core of sirtuins is conserved among the various isoforms; it is formed by a large Rossman-fold domain, present in many NAD+-binding proteins, and a small zinc-binding domain. A number of flexible loops bring together the two domains to form a large groove that accommodates both cofactor and substrate. A review on sirtuins is also part of the current journal issue [271].

Table 2.

Available Three-dimensional Structures of Human and Bacterial Sirtuins

| Name | Organism | PDB ID | Ligand | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIRT2 | Homo sapiens | 1J8F | - | [272] |

| SIRT3 | Homo sapiens | 3GLR | Acetyl-lysine AceCS2 peptide | [273] |

| 3GLS | - | |||

| 3GLT | Thioacetyl-lysine AceCS2 peptide | |||

| 3GLU | AceCS2 peptide | |||

| SIRT5 | Homo sapiens | 2B4Y | ADPR | [270] |

| 2NYR | Suramin | |||

| 3RIG | - | [274] | ||

| 3RIY | NAD+ | |||

| SIRT6 | Homo sapiens | 3K35 | ADPR | [275] |

| 3PKI | ADPR | |||

| 3PKJ | 2'-N-Acetyl-ADPR | |||

| CobB (Sir2) | Thermotoga maritima | 1YC5 | Nicotinamide | [268] |

| 2H2D | p53 peptide | [276] | ||

| 2H2F | p53 peptide | |||

| 2H2G | Histone H3 peptide | |||

| 2H2H | Histone H4 peptide | |||

| 2H2I | - | |||

| 2H4F | p53 peptide/NAD+ | [277] | ||

| 2H4H | p53 peptide/NAD+ | |||

| 2H4J | p53 peptide/Nicotinamide/2-O-acetyl-ADPR | |||

| 2H59 | p53 peptide/ADPR | |||

| 3D4B | p53 peptide/DADMe-NAD+ | [278] | ||

| 3D81 | S-alkylamidate intermediate | |||

| 3JR3 | Acetylated Peptide | [279] | ||

| 3PDH | Propionylated p53 peptide | [280] | ||

| CobB2 (Sir2Af2) | Archaeoglobus fulgidus | 1YC2 | NAD/ADPR/Nicotinamide | [268] |

| 1S7G | ADPR/NAD | [281] | ||

| 1MA3 | Acetylated p53 peptide | [282] | ||

| HST2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1Q14 | - | [283] |

| 1Q17 | ADPR | [284] | ||

| 1Q1A | Histone H4 peptide/2-O-acetyl-ADPR | |||

| 1SZC | Histone H4 peptide/CarbaNAD | [285] | ||

| 1SZD | Histone H4 peptide/ADPR | |||

| 2OD2 | Acetylated Histone H4 peptide/CarbaNAD | [269] | ||

| 2OD7 | Acetylated Histone H4 peptide/ADP-HPD | |||

| 2OD9 | Histone H4 peptide/ ADP-HPD/Nicotinamide | |||

| 2QQF | Acetylated Histone H4 peptide/ADP-HPD | |||

| 2QQG | Histone H4 peptide/ ADP-HPD/Nicotinamide | |||

| CobB1 | Archaeoglobus fulgidus | 1ICI | NAD+ | [267] |

| 1M2G | ADPR | [286] | ||

| 1M2H | ADPR | |||

| 1M2J | ADPR | |||

| 1M2K | ADPR | |||

| 1M2N | 2-O-acetyl-ADPR | |||

| CobB | Escherichia coli | 1S5P | Acetylated Histone H4 peptide | [286] |

| Sir2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 2HJH | Acetyl-ribosyl-ADP/Nicotinamide | |

| Sir2 | Plasmodium falciparum | 3JWP | AMP | |

| 3U31 | histone 3 myristoyl lysine 9 peptide/ NAD+ | [287] | ||

| 3U3D | histone 3 myristoyl lysine 9 peptide |

Acetyltransferases

Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) utilize acetyl-CoA (AcCoA) as cofactor and catalyze the transfer of an acetyl group to the ε-amino group of Lys side chains of histone proteins to promote gene activation. Two major classes of HATs have been identified, Type-A and Type-B. Type A HATs can be classified into three families, based on sequence homology and conformational structure: GNAT, p300/CBP, and MYST [288]. These proteins are able to acetylate multiple sites within the histone tails, and also additional sites on the globular histone core. Type-B HATs are mostly cytoplasmic and acetylate newly synthesized histones, H3 and H4, at specific sites prior to their deposition into chromatin. Proteins in this class are highly conserved and share some sequence identity with HAT1 from yeast, the most studied member of this family [289]. Three-dimensional structures of different HATs reveal a structurally conserved catalytic core domain that mediates the binding of the cofactor AcCoA and non-conserved N-terminal and C-terminal domains specific for each protein to mediate histone binding [290]. HAT proteins are often associated with other subunits in large multiprotein complexes playing important roles in modulating enzyme recruitment, specificity and activity. The combination of these subunits contributes to the unique features of each HAT complex. For example, some subunits have domains such as bromodomains, chromodomains, Tudor domains and PHD fingers that cooperate to the enrollment of HAT complexes to the appropriate location in the genome by means of modified histone tail recognition [291]. To date, several three-dimensional structures obtained both from X-ray crystallography or NMR are available for human and bacterial HATs; among these, only few structures report the full-length protein, while others describe only specific domains and their interactions with other subunits and/or substrate (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Available Three-dimensional Structures of Human and Bacterial Human and Bacterial HATs

| Class | Family | Name | Organism | PDB ID | Ligand | Domain | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type A | GNAT | KAT2A (GCN5) | Homo sapiens | 1F68 | Bromodomain | [292] | |

| 1Z4R | HAT Domain | [293] | |||||

| 3D7C | Bromodomain | [294] | |||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1E6I | Bromodomain | [295] | ||||

| 1YGH | HAT Domain | [296] | |||||

| KAT2B (PCAF) | Homo sapiens | 1CM0 | HAT Domain | [297] | |||

| 1JM4 | Bromodomain | [298] | |||||

| 1N72 | Bromodomain | [299] | |||||

| 1WUG | NP1 | Bromodomain | [300] | ||||

| 1WUM | NP2 | Bromodomain | |||||

| 1ZS5 | MIB | Bromodomain | |||||

| 2RNW | Bromodomain | [301] | |||||

| 2RNX | Bromodomain | ||||||

| 3GG3 | Bromodomain | [294] | |||||

| HPA2 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1QSM | AcCoA | HAT Domain | [302] | ||

| 1QSO | HAT Domain | ||||||

| p300/ CBP | p300 | Homo sapiens | 1L3E | CH1 domain | [303] | ||

| 1P4Q | CH1 domain | [304] | |||||

| 2K8F | Taz2 Domain | [305] | |||||

| 3BIY | Lys-CoA | HAT Domain | [306] | ||||

| 3I3J | Bromodomain | [294] | |||||

| 3IO2 | Taz2 Domain | [307] | |||||

| 3P57 | Taz2 Domain | [308] | |||||

| CBP | Homo sapiens | 1JSP | Bromodomain | [309] | |||

| 1LIQ | CH1 domain | [310] | |||||

| 1WO3 | CHANCE Domain (mutate) | [311] | |||||

| 1WO4 | CHANCE Domain (mutate) | ||||||

| 1WO5 | CHANCE Domain (mutate) | ||||||

| 1WO6 | CHANCE Domain (mutate) | ||||||

| 1WO7 | CHANCE Domain (mutate) | ||||||

| 1ZOQ | IRF-3 Binding Domain | [312] | |||||

| 2D82 | TTR | Bromodomain | [313] | ||||

| 2KJE | Taz2 Domain | [314] | |||||

| 2KWF | KIX Domain | ||||||

| 2L84 | J28 | Bromodomain | [315] | ||||

| 2L85 | L85 | Bromodomain | |||||

| 2RNY | Bromodomain | [301] | |||||

| 3DWY | Bromodomain | [294] | |||||

| 3P1C | Bromodomain | ||||||

| 3P1D | Bromodomain | ||||||

| 3P1E | DMSO | Bromodomain | |||||

| 3P1F | 3PF | Bromodomain | |||||

| 3SVH | KRG | Bromodomain | |||||

| 4A9K | Tylenol | Bromodomain | [316] | ||||

| Mus musculus | 1F81 | Taz2 Domain | [317] | ||||

| 1JJS | IRF-3 Binding Domain | [318] | |||||

| 1KBH | IRF-3 Binding Domain | [319] | |||||

| 1KDX | KIX Domain | [320] | |||||

| 1L8C | Taz1 Domain | [321] | |||||

| 1R8U | Taz1 Domain | [322] | |||||

| 1SB0 | KIX Domain | [323] | |||||

| 1TOT | ZZ Domain | [324] | |||||

| 1U2N | Taz1 Domain | [325] | |||||

| 2AGH | KIX Domain | [326] | |||||

| 2C52 | SRC1 Interaction Domain | [327] | |||||

| 2KA4 | Taz1 Domain | [328] | |||||

| 2KA6 | Taz2 Domain | ||||||

| 2KKJ | Nuclear Coactivator Binding Domain | [329] | |||||

| 2L14 | Nuclear Coactivator Binding Domain | [330] | |||||

| MYST | KAT5 (TIP60) | Homo sapiens | 2EKO | Histone tail binding domain | |||

| 2OU2 | AcCoA | HAT Domain | |||||

| KAT6A (MOZ) | Homo sapiens | 1M36 | Zinc Finger Domain | ||||

| 2OZU | AcCoA | HAT Domain | |||||

| 2RC4 | AcCoA | HAT Domain | [331] | ||||

| KAT8 (MOF) | Homo sapiens | 2GIV | AcCoA | HAT Domain | |||

| 2PQ8 | AcCoA | HAT Domain | |||||

| 2Y0M | AcCoA | HAT Domain | [332] | ||||

| 3QAH | HAT Domain | [333] | |||||

| 3TOA | HAT Domain | [334] | |||||

| 3TOB | HAT Domain (mutate) | ||||||

| Mus musculus | 1WGS | Tudor Domain | |||||

| ESA1 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1FY7 | AcCoA | HAT Domain | [335] | ||

| 1MJ9 | AcCoA | HAT Domain (mutate) | [336] | ||||

| 1MJA | AcCoA | HAT Domain | |||||

| 1MJB | AcCoA | HAT Domain (mutate) | |||||

| 2RNZ | Chromodomain | [337] | |||||

| 2RO0 | Tudor Domain | ||||||

| 3TO6 | H4K16CoA | HAT Domain | [334] | ||||

| 3TO7 | HAT Domain | ||||||

| 3TO9 | HAT Domain (mutate) | ||||||

| Type B | HAT1 | Homo sapiens | 2P0W | AcCoA | HAT | ||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1BOB | AcCoA | HAT | [338] | |||

| Rtt109 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 2RIM | AcCoA | HAT | [339] | ||

| 2ZFN | AcCoA | HAT | |||||

| 3CZ7 | AcCoA | HAT | [340] | ||||

| 3Q33 | AcCoA | HAT | [341] | ||||

| 3Q35 | AcCoA | HAT | |||||

| 3Q66 | AcCoA | Full length | [342] | ||||

| 3Q68 | AcCoA | Full length | |||||

| 3QM0 | AcCoA | HAT | [343] | ||||

A growing interest on novel drug design initiatives is currently focused on the primary readers of the histone code, the histone binding domains (HBDs). Notable HBDs are the Bromodomain (BD) proteins, which are structurally small and evolutionary conserved modules that bind acetyl-Lys and are part of larger BCPs (bromodomain containing proteins) [344]. These modules are frequently found in HATs as well as members of the histone methyl-transferase (HMT) family and ATP-dependent remodeling enzymes [19,345]. At least 56 BDs are encoded in the human genome and translated in 42 different known proteins whose structures, for half of them, have been determined by X-ray crystallography [344,346]. The research focused on inhibition of BDs has been stimulated by the discovery of two potent compounds (I-BET762 and JQ1) with in vivo efficacy in murine models of NUT (nuclear protein in testis) midline carcinoma, as well as AML and severe immune inflammation [347-350]. Other recent works show the application of fragment-based drug discovery techniques for the identification of new BD inhibitors [316,347,348,351,352] in addition to evidence that the pharmacological inhibition of BET (bromodomains and extra terminal domain) family proteins leads to rapid and potent abrogation of MYC gene transcription [353].

Methylation

Histone Methyltranferases

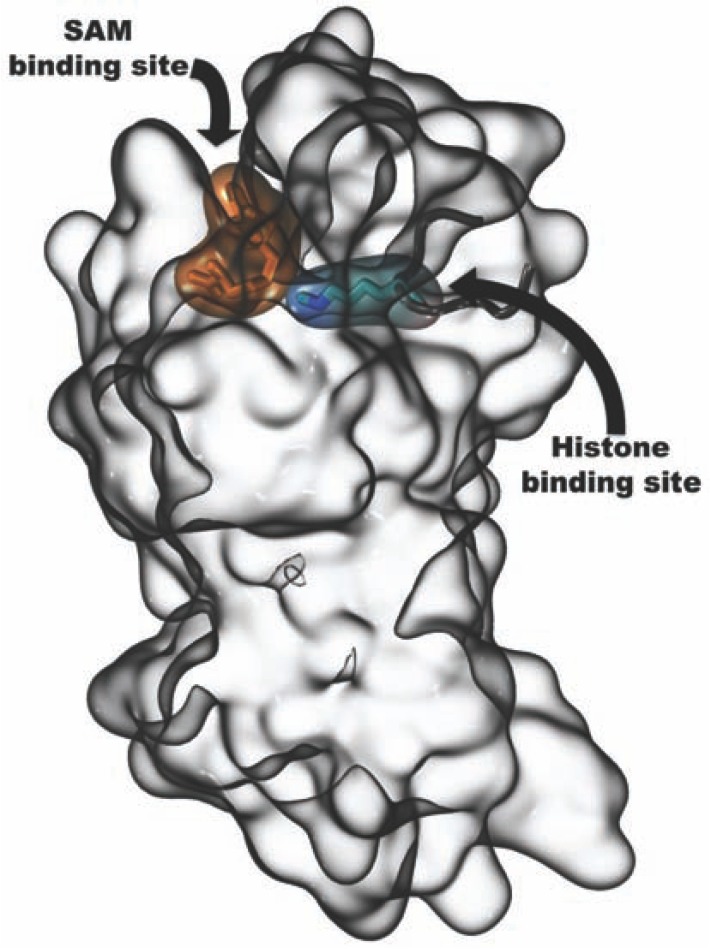

Protein methyltransferases (PMTs) are a group of histone-modifying enzymes belonging to the large number of coded PTMs [73,354,355]. Currently two different classes of PMTs are recognized: protein lysine methyltransferases (PKMT) and protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMT), which are encoded in 51 and 45 genes [356], respectively. PMTs emerged recently as new important targets for cancer therapy since they were found to be overexpressed or repressed in several types of cancer [73]. PKMTs can mono-, di- or tri-methylate target Lys residues, whereas PRMTs are able to mono- or di-methylate the histone Arg residues [41,72,73, 191,355,357-363]. PKMTs share a conserved active site in the so-called SET (Su(Var)3-9, Enhancer of zeste, Trithirax) domain. The only known exception is the DOT1L, which has PKMT activity without having the SET domain in its structure. DOT1L also shares a higher homology towards PRMTs and is often reported in the PRMTs family tree diagrams as having a PKMT function [72,73,355,356]. In order to methylate a certain Lys or Arg residues in a histone, PMTs use a reactive S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) which leaves a methyl group to the respective Lys or Arg residue, becoming S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH). SAM is used as substrate by proteins other than PMTs and this raises the question whether pharmacological modulation of the SAM binding site may guarantee an adequate selectivity against other SAM-binding proteins. The structural characteristic that differentiates PMTs to other SAM-binding proteins is their elongated active site geometry. In PMTs the SAM binding pocket entrance is in the opposite position of the hydrophobic and narrow histone (Lys or Arg) binding pocket of the methyltransferase; these two tunnels have a contact area where methylation of histones occurs [73,364]. Several reviews published recently, including one of the current journal issue, describe the mechanism of action of PMTs [41,72,73,191,355,357-363]. Because of the importance of PMTs as new biological targets for anticancer therapy, elucidation of their structure is fundamental to undertake drug design campaigns. In the following sections we describe the current structural knowledge available on PMTs.

PKMTs

To date there are 26 crystallized Lys methyltransferases available in the Protein Data Bank (Table 4). With the exception of DOT1L, all of them share the canonical SET domain [72,73,355, 356] and have S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH, the product of the methylation reaction), or early inhibitors co-crystallized. Structures with reported inhibitors are DOT1L, EHMT1, EHMT2, SETD7, SMYD1, SMYD2, SMYD3 (Table 4). Emerging crystallographic structures are likely to allow the implementation of structure-based drug design approaches as these targets become more and more validated for specific anticancer therapies. Moreover, due to the presence of additional proteins interacting with PKMTs during histone methylation, some structures, i.e. MLL1, EHMT1, SETD7, SETD8, SETMAR and SMYD2, were resolved with bound peptide partners. This information is also relevant to the design of potential protein-protein interaction inhibitors. However, to our knowledge, no work has been so far reported in this context. The most direct approach for developing PKMTs ligands seems to be focused on the SET domain. However, whether the most effective approach is to target the SAM or histone binding sites is still subject of investigations, although some co-crystal structures demonstrate that both might be pursued (Table 4) [73,364]. The complete list of crystallographic structures available PKMTs is reported in Table 3. PKMTs with resolved SET domain include: MLL1, EHMT1, EHMT2, SUV39H2, NSD1, SETD3, SETD6, SETD7, SETD8, SETD2, SETMAR, ASH1L, SUV420H1, SUV420H2, SMYD1, SMYD2, SMYD3, PRDM1, PRDM4, PRDM10, PRDM11, PRDM12. This structural information may help to predict selectivity of PKMTs ligands to one or more proteins of this family.

Table 4.

Available Three-dimensional Structures of Mammals PKMTs

| Name | Organism | PDB ID | Ligand | Domain | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOT1L | Homo sapiens | 1NW3, 3QOW | SAM | [365,366] | |

| 3QOX | SAH | [366] | |||

| 3SX0 | brominated SAH analog | ||||

| 3SR4 | TT8a | [367] | |||

| 3UWP | 5-iodotubercidin | ||||

| MLL1 | Homo sapiens | 2W5Y | SAH | Methyltransferase | [368] |

| 2W5Z | Histone peptide, SAH | Methyltransferase | [368] | ||

| 2KU7 | PHD3-Cyp33 RRM chimeric protein (NMR) | [369] | |||

| 3LPY | PHD3-bromo cassette | ||||

| 3LQH | Third PHD finger and bromo | ||||

| 3LQI | H3(1-9)K4me2 peptide | PHD3-bromo | |||

| 2KYU | PHD3 finger | PHD3 finger | [370] | ||

| EHMT1 | Homo sapiens | 2IGQ | SAH | C-terminal | [371] |

| 2RFI | SAH | Catalytic | |||

| 3B7B | Ankyrin repeat domains | [372] | |||

| 3B95 | Histone H3 N-terminal Peptide | Ankyrin repeat | |||

| 3FPD | BIX-01294a, SAH | SET | [373] | ||

| 3HNA | Mono-Methylated H3K9 Peptide SAH | Catalytic | [371] | ||

| 3MO0 | E11a, SAH | SET | [364] | ||

| 3MO2 | E67a, SAH | SET | |||

| 3MO5 | E72a, SAH | SET | |||

| 3SW9 | Dnmt3a peptide, Sinefungin | C-terminal | [374] | ||

| 3SWC | Dnmt3a peptide, SAH | C-terminal | [374] | ||

| EHMT2 | Homo sapiens | 2O8J | SAH | SET | [371] |

| 3K5K | DXQa, SAH, | SET | [375] | ||

| 3RJW | CIQa, SAH | SET | [376] | ||

| 3DM1 | |||||

| SUV39H1 | Homo sapiens | 3MTS | Chromo | ||

| SUV39H2 | Homo sapiens | 2R3A | SAM | Methyltransferase | [371] |

| NSD1 | Homo sapiens | 3OOI | SAM | SET | [377] |

| WHSC1L1 | Homo sapiens | 2DAQ | PWWP (NMR) | ||

| SETD1A | Homo sapiens | 3S8S | RRM | ||

| SETD3 | Homo sapiens | 3SMT | SAM | ||

| SETD6 | Homo sapiens | 3QXY | SAM | N-lysine methyltransferase | [378] |

| 3RC0 | SAM | N-lysine methyltransferase | |||

| SETD7 | Homo sapiens | 1H3I | N-terminal, SET | [379] | |

| 1MT6 | SAH | N-terminal, SET | [380] | ||

| 1MUF | |||||

| 1N6A | SAM | SET | [381] | ||

| 1N6C | |||||

| 1O9S | SAH, N-methyl-lysine | N-terminal, SET | [382] | ||

| 1XQH | p53 peptide, SAH, N-methyl-lysine | N-terminal, SET | [383] | ||

| 2F69 | TAF10 peptide, SAH, N-methyl-lysine | N-terminal, SET | [384] | ||

| 3CBM | Estrogen receptor peptide, SAH | SET | [385] | ||

| 3CBO | Estrogen receptor peptide, SAH | ||||

| 3CBP | Estrogen receptor peptide, SAH, Sinefungin | ||||

| 3M53, 3M54, 3M55, 3M56, 3M57, 3M58, 3M59, 3M5A | TAF peptide, SAH | SET with various mutations | |||

| 3OS5 | Dnmt1 peptide, SAH, N-methyl-lysine | SET | [386] | ||

| 4E47 | SAM, 0N6a | SET | |||

| SETD8 | Homo sapiens | 1ZKK | Histone 4 peptide, SAH | SET | [387] |

| 2BQZ | Histone 4 peptide, SAH, N-methyl-lysine | SET | [388] | ||

| 3F9W | Histone 4 peptide, SAH | SET (Y334F) | [389] | ||

| 3F9X | Histone 4 peptide, SAH, N-dimethyl-lysine | SET (Y334F) | |||

| 3F9Y | Histone 4 peptide, SAH, N-methyl-lysine | SET (Y334F) | |||

| 3F9Z | Histone 4 peptide, SAH | SET (Y334F) | |||

| SETD2 | Homo sapiens | 2A7O | HSET2/HYBP SRI (NMR) | [390] | |

| 3H6L | SAM | SET | |||

| SETDB1 | Homo sapiens | 3DLM | Tudor | ||

| SETMAR | Homo sapiens | 3BO5 | SAH | N-methyltransferase | |

| 3F2K | LTFA peptide, selenomethionine | Transposase | |||

| 3K9J | Transposase | [391] | |||

| 3K9K | Transposase | ||||

| ASH1L | Homo sapiens | 3MQM | Bromo | [294] | |

| 3OPE | SAM | SET | |||

| SUV420H1 | Homo sapiens | 3S8P | SAM, selenomethionine | SET | |

| SUV420H2 | Homo sapiens | 3RQ4 | SAM | SET | |

| SMYD1 | Mus musculus | 3N71 | Sinefungin | SET and MYND | [392] |

| SMYD2 | Mus musculus | 3QWV | SAH, Sinefungin | SET and MYND | [393] |

| 3QWW | |||||

| Homo sapiens | 3RIB | SAH | SET and MYND | [394] | |

| 3S7B | NH5a, SAM | SET and MYND | [395] | ||

| 3S7D | Monomethylated p53 peptide, SAH | ||||

| 3S7F | p53 peptide, SAM | ||||

| 3S7J | SAM | ||||

| 3TG4 | SAM | SET and MYND | [396] | ||

| 3TG5 | p53 peptide, SAH | ||||

| SMYD3 | Homo sapiens | 3MEK | Selenomethionine, SAM | SET and MYND | |

| 3OXF | SAH | SET and MYND | [397] | ||

| 3OXG | |||||

| 3OXL | |||||

| 3PDN | Sinefungin | SET and MYND | [398] | ||

| 3QWP | SAM | SET and MYND | |||

| 3RU0 | Sinefungin | SET and MYND | [399] | ||

| PRDM1 | Homo sapiens | 3DAL | SET | ||

| PRDM2 | Homo sapiens | 2JV0 | SET (NMR) | [400] | |

| 2QPW | SET | [371] | |||

| PRDM4 | Homo sapiens | 2L9Z | Residues 366-402 | [401] | |

| 3DB5 | Selenomethionine | SET | |||

| PRDM10 | Homo sapiens | 3IHX | SET | ||

| PRDM11 | Homo sapiens | 3RAY | SET | ||

| PRDM12 | Homo sapiens | 3EP0 | SET |

ligand PDB ID

PRMTs

As for PKMTs, Arg histone residues can likewise be methylated by protein methyltransferases. Specific PRMTs can mono-methylate or di-methylate, symmetrically or asymmetrically, specific Arg residues in histones through a mechanism similar to the one of PKMTs: a SAM molecule donates a methyl group to an Arg residue becoming SAH [72,73,355]. Interestingly, Arg methylation can be correlated with active transcription or its inhibition. An example is the methylation of Arg 2 of histone 3: when mono-methylated, transcription of DNA is active. Conversely, after di-methylation operated by PRMT6, the transcription is inhibited [402]. PRMTs, like the coactivator-associated arginine methyl-transferase (CARM1) and PRMT5, have been described to play an important role in cancer as their expression increases in breast and prostate cancers, for CARM1, and lymphoma, for PRMT5. Research conducted on new modulating agents of these PRMTs has been documented [72,73]. In particular, CARM1 has been described as a potential oncological target as its interactions with nuclear transcription factors and p53 may represent a new approach for treating cancer [403]. Its crystal structure (Table 5) has been resolved with a bound indole-based inhibitor, providing new insightful information for the inhibition of this Arg methyltransferase. Other PRMTs that have been crystallized are: PRMT1, PRMT2, PRMT3, ECE2, METTL11A.

Table 5.

Available Three-dimensional Structures of Mammals PRMTs

| Name | Organism | PDB ID | Ligand | Domain | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARM1 | Rattus norvegicus | 2OQB | N-terminal | [402] | |

| 3B3F | SAH | Catalytic | |||

| 3B3G | Catalytic | ||||

| 3B3J | N-terminal, Catalytic and C-terminal | ||||

| Mus musculus | 2V74 | SAH | Catalytic | [404] | |

| 2V7E | |||||

| Homo sapiens | 2Y1W | Sinefungin, 849a | Catalytic | [403] | |

| 2Y1X | SAH, 845a | ||||

| PRMT1 | Rattus norvegicus | 1OR8 | Substrate peptide, SAH | Full length | [405] |

| 1ORH | Substrate peptide, SAH | Full length (E153Q) | |||

| 1ORI | SAH | Full length | |||

| 3Q7E | SAH | Full length | |||

| PRMT2 | Homo sapiens | 1X2P | SH3 | ||

| PRMT3 | Mus musculus | 1WIR | C2H2 zinc finger | ||

| Rattus norvegicus | 1F3L | SAH | C2H2 zinc finger, SAM binding and catalytic | [406] | |

| Homo sapiens | 2FYT | SAH | SAM binding and catalytic | ||

| 3SMQ | TDUa | SAM binding and catalytic | |||

| ECE2 | Homo sapiens | 2PXX | SAH | Methyltransferase-like region (R100C) | [407] |

| METTL11A | Homo sapiens | 2EX4 | SAH | Full length |

ligand PDB ID

DNA Methyltransferases

DNA methyltransferases are enzymes that methylate DNA patterns involved in several biological functions like gene silencing, X-chromosome inactivation, DNA repair, and reprogramming elements responsible for carcinogenesis [408]. In the last decade, the variety of functions intrinsic to this family of enzymes has propelled research on their biology and pharmacology. In mammals, DNA methylation occurs at the C5 position of cytosine (5mC), predominantly within CpG dinucleotides belonging to the CpG islands. These enzymes use the same substrate of PMTs, a SAM molecule, that is responsible for donating a methyl group to the cytosine nucleotide [359,408-411]. The mechanism of reaction requires the binding of the DNA methyltransferase to the DNA strand. This interaction projects the double helix outwards, thereby causing a cytosine base-flipping. A subsequent attack from the conserved nucleophile cysteine on the cytosine C6 is followed by the transfer of the methyl group from SAM to the activated cytosine C5 [408,410].

DNMTs can be divided into three groups according to their function: DNMT1, the most abundant DNA methyltransferase, regarded as a maintenance enzyme; DNMT3s A and B considered de novo methyltransferases because they have the ability to newly methylate cytosines; DNMT3L itself (part of the second group of DNMTs) does not have any catalytic activity but it is required for the function of DNMT3A and B; finally, DNMT2, the least studied DNA methyltransferase, has been solved by X-ray crystallography and biochemical data demonstrate that it functions as an aspartic acid transfer RNA (tRNAAsp). Recent data suggest that there are additional functions for this DNA methyltransferase [227,412]. The structure of DNMTs is mainly composed of a large N-terminal region, with several domains and variable size, and a C-terminal domain. While the N-terminal domain has several distinct regulatory functions, the catalytic site is located in the C-terminal domain [408,411]. Among the regulatory functions of the N-terminal region, there are the guidance of these proteins towards the nucleus and their interaction with DNA and chromatin. The C-terminal domain is more conserved between bacterial and eukaryotic DNMTs and, in its active site, a set of ten residues constitutes the motif for all DNMTs that methylate C5 cytosines. The core of the catalytic domain of all DNMTs is common along this enzyme family and is termed AdoMet-dependent MTase fold. In this domain, conserved regions are involved in catalysis and co-factor binding, whereas the non-conserved region is involved in DNA recognition and specificity to methylate certain cytosines [408,411]. The ensemble of structural data of DNMTs is show in Table 6.

Table 6.

Available Three-dimensional Structures of Mammals DNMTs

| Name | Organism | PDB ID | Ligand | Domain | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT1 | Mus musculus | 3AV4 | DNMT1 | ||

| 3AV5 | SAH | DNMT1 | |||

| 3AV6 | SAM | DNMT1 | |||

| 3PT6 | DNA, SAH | DNMT1 | [414] | ||

| 3PT9 | SAH | DNMT1 and DNA complex | |||

| Homo sapiens | 3EPZ | RFTS domain, Beta-d-glucose | DNMT1 | [415] | |

| 3PTA | DNA, SAH | RFTS | [414] | ||

| 3SWR | Sinefungin, MESa, | DNMT1 and DNA complex | |||

| 3OS5 | SETD7, SAH | DNMT1 | [386] | ||

| DNMT2 | Homo sapiens | 1G55 | SAH | Complex with SETD7 | [412] |

| DNMT3A | Homo sapiens | 2QRV | DMNT2 (deleted in 191-237) | [416] | |

| 3A1A | DNMT3a-DNMT3L C-terminal complex | [417] | |||

| 3A1B | ADD and histone H3 complex | ||||

| 3LLR | ADD and histone H3 complex | [418] | |||

| DNMT3B | Mus musculus | 1KHC | PWWP | [419] | |

| Homo sapiens | 3FLG | PWWP | |||

| 3QKJ | PWWP | [418] | |||

| DNMT3L | Homo sapiens | 2PV0 | PWWP | [420] | |

| 2PVC | Histone H3 peptide | DNMT3L | |||

| 2QRV | SAH | DNMT3L - DNMT3a C-terminal complex | [416] |

ligand PDB ID

It is important to note that the close relationship between DNMTs functions on the cell and cancerogenesis led this family of proteins to be intensively studied for a number of cancer pathologies (see previous chapters). Comprehensive reviews providing more detail on inhibitor development and major milestones in targeting DNMTs have been published recently [65,227,357,360, 361,413].

Demethylases

The focus in the last decade in understanding protein methylation led to the discovery of histone demethylases. The existence of this protein family was first described by Shi et al., who identified the first protein with histone demethylase activity, the lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) [421]. Since then, histone demethylation was identified as an important regulator for gene transcription and the interest in this protein family increased rapidly in subsequent years. Tsukada et al. [422] described a member of the JMJC (Jumonji C) domain family of proteins as having demethylase activity. Soon thereafter, 30 members of the JMJC domain family were found employing bioinformatics approaches, but only 18 of them have been reported to exhibit demethylase activity [423]. Histone demethylases are currently divided into two families: LSD demethylases and JMJC demethylases. These two protein families differ in their mechanism of Lys demethylation, in their structure and in substrate specificity.

The LSD family has two members, LSD1 and LSD2, and uses FAD to demethylate the histone Lys residues H3K4 and H3K9 through a FAD-dependent oxidative reaction [424]. Through this mechanism, both demethylases are only able to operate on mono- or-di-methylated Lys residues. Currently, structural data is only available for LSD1 (Table 7). The complete structure of the LSD1 comprises an amine oxidase domain with two lobes: a FAD binding region and the substrate binding region. The latter is responsible for the enzymatic activity of the LSD1, as the active site is located at the interface of the two lobes and is similar to conventional FAD-dependent amine oxidases [424]. Furthermore, this protein has an N-terminal SWIRM (derived from Swi3p, Rsc8p, and Moira) domain which is responsible for protein-chromatin interactions. The SWIRM and amino oxidase domains are packed together, forming a globular structure. Interestingly, LSD1 was demonstrated to demethylate in vitro methylated peptides but is itself unable to demethylate methyl-Lys of the nucleosome [424-426]. Only in complex with the co-repressor protein (CoREST) this protein is able to demethylate nucleosomes, indicating that LSD1 protein partners are likely to be involved in enzymatic activity in vivo [424].

Table 7.

Available Three-dimensional Structures of Demethylases

| Name | Organism | PDB ID | Ligand | Domain | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSD1 | Homo sapiens | 2COM | - | SWIRM | [432] |

| 2DW4 | FAD | [433] | |||

| 2EJR | F2Na | ||||

| 2Z3Y | F2Na | Full length | |||

| 2Z5U | FA9a | ||||

| 2H94 | FAD | [434] | |||

| 2HKO | FAD | [435] | |||

| 2IW5 | CoREST 1 peptide, FAD | SWIRM, amine oxidase and linker | [436] | ||

| 2L3D | SWIRM domain | ||||

| 2UXN | CoREST 1 peptide, Histone H3 peptide, FDAa | SWIRM domain, amine oxidase domain and linker | [437] | ||

| 2UXX | CoREST 1 peptide, Histone H3 peptide, FA9a | ||||

| 2V1D | CoREST 1 peptide, Histone H3 peptide, FAD | SWIRM domain, amine oxidase domain and linker | [438] | ||

| 2X0L | CoREST 1 peptide, Histone H3 peptide, FAD | Full length | [439] | ||

| 2XAF | CoREST 1 peptide, FAD, TCFa | Full length | [440] | ||

| 2XAG | |||||

| 2XAH | CoREST 1 peptide, FAD, 3PLa | ||||

| 2XAJ | CoREST 1 peptide, FAD, TCAa | ||||

| 2XAQ | CoREST 1 peptide, FAD, M84a | ||||

| 2XAS | CoREST 1 peptide, FAD, M80a | ||||

| 2Y48 | CoREST 1 peptide, Zinc finger protein SNAI1, FAD | Full length | [441] | ||

| 3ABT | amine oxidase domain 2, 2PFa | Full length | [442] | ||

| 3ABU | amine oxidase domain 2, 12Fa | ||||

| JMJD5 | Homo sapiens | 3UYJ | AKGc | JmjC | |

| 4AAP | OGAb | JmjC | |||

| JMJD6 | Homo sapiens | 3K2O | - | Full length | [443] |

| 3LD8 | antibody Fab fragment | Full length | |||

| 3LDb | antibody Fab fragment, AKGc | Full length | |||

| FBXL11 | Homo sapiens | 2YU1 | AKGc | JmjC | |

| 2YU2 | - | ||||

| JHDM1D | Homo sapiens | 3KV5 | OGAb | JmjC | [444] |

| 3KV6 | AKGc | ||||

| 3KV9 | - | ||||

| 3KVa | AKGc | ||||

| 3KVb | OGAb | ||||

| 3U78 | AKG, E67a | JmjC | [445] | ||

| PHF8 | Caenorhabditis elegans | 3N9L | Histone H3 peptide, OGAb | PHD and JmjC | [446] |

| 3N9M | - | PHD | |||

| 3N9N | Histone H3 peptide, OGAb | PHD and JmjC | |||

| 3N9O | Histone H3 peptides, OGAb | PHD and JmjC | |||

| 3N9P | Histone H3 peptide, OGAb | PHD and JmjC | |||

| 3N9Q | Histone H3 peptides, OGAb | PHD and JmjC | |||

| 3PUQ | AKGc | PHD | [447] | ||

| 3PUR | 2HGa | PHD | |||

| Mus musculus | 1WEP | - | PHD | ||

| Homo sapiens | 2WWU | BGCa | PHD and JmjC | [448] | |

| 3K3N | - | PHD | [449] | ||

| 3K3O | AKGc | PHD | |||

| 3KV4 | OGAb | PHD | [444] | ||

| PHF2 | Homo sapiens | 3KQI | Histone H3 peptide | PHD finger | [450] |

| 3PTR | - | JmjC | [451] | ||

| 3PU3 3PU8 3PUA 3PUS |

OGAb | JmjC | |||

| JMJD3 | Homo sapiens | 2XUE | AKGc | JmjC | |

| 2XXZ | 8XQa | JmjC | |||

| UTX | Homo sapiens | 3AVS | OGAb | JmjC | [452] |

| 3AVR | OGAb | ||||

| JMJD2A | Homo sapiens | 2GF7 | - | tudor | [453] |

| 2GFa | - | ||||

| 2GP3 | - | JmjC | [454] | ||

| 2GP5 | AKGc | ||||

| 2OQ6 | OGAb | JmjC | [455] | ||

| 2OQ7 | OGAb | ||||

| 2OS2 | Histone H3 peptide, OGAb | ||||

| 2OT7 | Histone H3 peptide monomethyl, OGAb | ||||

| 2OX0 | synthetic peptide, OGAb | ||||

| 2P5b | Histone H3 peptide, OGAb | JmjC | [456] | ||

| 2PXJ | monomethylated Histone H3 peptide, OGAb | ||||

| 2Q8c | Histone H3 peptide, AKGc | JmjC | [457] | ||

| 2Q8D | Histone H3 peptide, SINa | ||||

| 2Q8E | Histone H3 peptide, AKGc | ||||

| 2QQR | - | tudor | [458] | ||

| 2QQS | Histone H4 peptide | ||||

| 2VD7 | PD2a | JmjC | |||

| 2WWJ | Y28a | JmjC | [459] | ||

| 2YBK | 2HGa | JmjC | [460] | ||

| 2YBP | Histone H3 peptide,2HGa | ||||

| 2YBS | Histone H3 peptide, S2Ga | ||||

| 3NJY | 8XQa | JmjC | [461] | ||

| 3PDQ | KC6a | JmjC | [462] | ||

| 3U4S | T11C Peptide, 08Pa | JmjC | [463] | ||

| JMJD2C | Homo sapiens | 2XDP | - | tudor | |

| 2XML | OGAb | JmjC | |||

| JMJD2D | Homo sapiens | 3DXT | - | JmjC | |

| 3DXU | OGAb | JmjC | |||

| JARID1B | Mus musculus | 2EQY | - | ARID | |

| JARID1C | Homo sapiens | 2JRZ | - | ARID | [464] |

| JARID1D | Homo sapiens | 2E6R | - | PDH | |

| 2YQE | - | ARID | |||

| JARID1A | Homo sapiens | 2JXJ | - | ARID | [465] |

| 2KGG | C-terminal PHD finger | [466] | |||

| 2KGI | Histone H3 peptide | ||||

| 3GL6 | Histone H3 peptide | C-terminal PHD finger | |||

| JARID2 | Mus musculus | 2RQ5 | - | ARID | [467] |

| MINA | Homo sapiens | 2XDV | OGAb | JmjC | |

| NO66 | Homo sapiens | 4DIQ | PD2a | JmjC |

PDB ligand ID

N-Oxalylglycine

α-Ketoglutaric acid

All demethylases of the JMJC family have a JMJC domain in common which has been demonstrated to fold into eight β-sheets, in a jellyroll-like β-fold [423,424,427,428]. In the inner part of this jellyroll structural motif, the active site is buried and has a Fe2+ metal which is coordinated by α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and three conserved residues, a Glu and two His. The enzyme uses molecular oxygen in order to convert the methyl group of the methylated Lys in hydroxymethyl, which is successively released as formaldehyde. This type of active site permits JMJC demethylases to demethylate mono- and di-methylated lysines, and to also act on tri-methylated lysines [423,424,427-429]. The jellyroll motif is surrounded by other structural elements which help to maintain the structural integrity of the catalytic core and contribute to substrate recognition [424].

LSD and JMJC demethylases have been reported as regulators of various cellular processes. A considerable effort is currently directed to the discovery of small-molecule inhibitors able to modulate their catalytic activity. The number of structures of demethylases available from the PDB is growing rapidly (Table 7) [430,431].

Ubiquitylation and Sumoylation

The formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal Gly76 of ubiquitin (Ub) and an ε-amino group on one of the internal Lys residues of a substrate protein is known as ubiquitylation. This PTM of proteins occurs through a series of enzymatic steps involving E1, E2 and E3 proteins. Firstly, Ub is activated to form a thioester with a specific cysteine residue located in the E1 enzyme, also known as ubiquitin-activating (UBA) enzymes. The activated Ub is subsequently transferred to one of the Ub-conjugating enzymes (E2) and, eventually, an Ub ligase (E3) interacts with the ubiquitylation target and transfers the activated Ub from E2 to one of the Lys on the protein substrate, including histones [12]. In contrast to other histone PTMs, ubiquitylation involves a significant change at molecular level since the Ub is a 76 amino acids protein that marks proteins for ATP-dependent proteolytic degradation by 26S proteasomes in the so called Ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS). Some E1, E2 and E3 enzymes have been found to be responsible for the addition and removal (via DUB enzymes) of ubiquitin from histones H2A and H2B [15,24]. These studies highlighted that H2A and H2B ubiquitylation, especially the mono-ubiquitylation, plays a key role in regulating several epigenetic processes within the nucleus, including transcription initiation, elongation, silencing and also DNA repair [15,468-470]. A correlated PTM is the sumoylation, which consists in the attachment of ubiquitin-like fragments on histone Lys residues through ubiquitylating enzymes [471]. This PTM is still scarcely characterized but appears to exert a transcriptional repression role by competing with ubiquitylation at the substrate level [472]. Some three-dimensional structures of UBAs have been resolved [473,474], though the current knowledge on the ubiquitylating enzyme cascade is still fragmentary in relation to the involvement of these proteins as epigenetic controllers of histones. Consequently, the road to the full comprehension of structural data and their involvement in the mechanistic processes is still a major area of research. Moreover, the identification of small-molecule modulators of ubiquiting ligases is currently an active field of research for novel anti-cancer drugs [475-479]. Small molecules have been described for Mdm2 and R7112, but their action seems to primarily affect the ubiquitination mechanism of p53 and not those mechanisms leading to the modification of histone tails [479]. Further insights on the structural and functional roles of ubiquitylating enzymes are needed as they are expected to let emerge new biological targets for anticancer therapies [478].

ADP-ribosylation

Histone proteins have been described to be mono- and poly-ADP-ribosylated, thus these PTMs have been directly linked to the epigenetic code [480]. The transfer of one ADP-ribose from NAD+ to specific residues is known as mono-ADP-ribosylation and is catalyzed by ADP-ribosyltransferases referred to as ARTC (Clostridia-toxin-like) or ARTD (diphtheria toxin-like; formerly known as PARPs), as well as by mitochondrial SIRT4 and nuclear SIRT6 sirtuin family members [480,481]. The subcellular location of ARTC does not allow mono-ADP-ribosylation of histone tails as these proteins are ecto-enzymes [480]; vice versa some ARTD members and SIRT6 can be involved in nuclear mono-ADP-ribosylation of histones. Furthermore, ADP-ribosylation of protein-linked ADP-ribose results in poly-ADP-ribosylated proteins, a reaction that is catalyzed by certain members of the ARTD family. ARTD1 (also known as PARP1) activity causes chromatin decondensation by poly-ADP-ribosylating core histones and the linker histone H1 [482]. The full understanding of histone ADP-ribosylation is currently a major topic of research, especially for the identification of ADP-ribosylation sites in vivo and the development of specific tools to locate these histone modifications [483,484]. Several studies indicate that histones are covalently modified by mono-ADP-ribose in response to genotoxic stress, and others that the extent of mono-ADP-ribosylation of histones depends on the cell cycle stage, proliferation activity and degree of terminal differentiation [485-490].

While the role of ADP-ribosylation as histone PTM is being elucidated [491-495], it should be acknowledged that ARTDs and sirtuins emerged in the last decades as important biological targets for many other cellular processes [484]; moreover several medicinal chemistry approaches aimed at the discovery of novel inhibitors recently appeared [483,490,496-500]. The most studied ADP-ribosylating enzyme has been ARTD1, however growing evidences indicate important roles of other mono- and poly-ADP-ribosylating enzymes, including tankyrases [490,501-503]. Crystallographic and NMR data exist for some ARTD members and have been recently described [502]. ARTCs are less characterized from a structural point of view. A review on this topic is available in the current journal issue [482]. For available structural data on ADP-ribosylating sirtuins see the previous sections.

Even though the role that ADP-ribosylation plays in histone modifications has not yet been completely characterized, it should be acknowledged that this PTM was shown to largely contributes to the epigenetic control of several important process, such as regulation of genomic methylation patterns in gene expression [504,505], effects on chromatin structure [506-508] and transcriptional activator and co-activator functions [492]. It is expected that further definition of specific functions of ADP-ribose modifications will incite efforts towards the identification of new therapeutic routes based on small-molecule inhibitors of these enzymes.

Phosphorylation

Histone phosphorylation plays a key role in cell cycle control, DNA repair, apoptosis, gene silencing, chromatin structure and cellular differentiation [8,11,12,509-515]. It occurs on Ser, Thr, Tyr and His residues and is not limited to histone tails [12,516-518]. The regulation of histone phosphorylation is operated by the enzymatic activity of kinases that transfer a phosphate group to a target residue and phosphatases that counter this activity by hydrolyzing phosphates. Identified kinases that contribute to dynamic phosphorylation marks on histones include Aurora B [511], MSK1 [513], HHK [517], among others [514,519]. Structural data about some of these kinases are documented in the available literature while other kinases are still not well described. The mechanism and pharmacological interventions on histone phosphorylation are still poorly understood. However, it is worth noting that the pattern of expression of histone H4 His kinase (HHK) has been suggested as a useful diagnostic marker for hepatocellular carcinoma [517]. To our knowledge, no compounds addressing the pharmacological modulation of histone phosphorylation have been approved to date, though several Aurora kinase inhibitors have been identified and some have entered phase II clinical trials [24].

Glycosylation

The addition of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to Ser and Thr residues (O-GlcNAc) of nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins is an unconventional type of glycosylation that represents an important PTM. This kind of glycosylation is atypical for at least three reasons. First, it involves the addition of a single monosaccharide; second, it takes place in the cytoplasm and modified glycoproteins are usually nuclear and cytoplasmic, including RNA polymerase II, ER, c-Myc proto-oncogene and histones; third, it is reversible in the way that the monosaccharide can repeatedly be attached and detached. In general, the addition of O-GlcNAc is reciprocal with Ser and Thr phosphorylation, either by modification of the same residue or nearby residues [520]. This PTM modification is regulated by only two enzymes: a glycosyltransferase that catalyzes the transfer of GlcNAc to substrate proteins, also known as O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT), and a glycoside hydrolase, also known as O-GlcNAcase (OGA) or O-N-acetylglucosaminidase, that catalyzes the hydrolysis of the glycosidic linkage [521]. While it is interesting to note that in mammalians only these two highly conserved enzymes are responsible of O-GlcNAc cycling, it is worth emphasizing that the targeting of these enzymes is highly specific and is controlled by many interacting subunits.

Only recently O-GlcNAc was linked to the epigenetic code, demonstrating that the four core histones are substrates for O-GlcNAc modifications and cycle genetically and physically in order to interact with other PTMs of histones [520,522-526]. In addition, OGT has been described to target key members of the Polycomb and Trithorax groups [527]. The role of O-GlcNAc as a PTM able to alter key cellular signaling pathways has been discussed by linking epigenetic changes and metabolism [523]. Even though the role of ‘conventional’ glycosylation in cancer [528-532] and in ageing [533] is well recognized, little is known on the role of O-GlcNAc histone modification in cancer [531].

Details about how OGT recognizes and glycosylates its protein substrates, including histone proteins, were almost unknown until recent years, when novel protein structural data became available (PDB codes: 1W3B and 3TAX) [521,534,535]. In 2011, the first two crystal structures of human OGT were solved: a binary complex with uridine 5'-diphosphate (UDP) and a ternary complex with UDP and a peptide substrate, including the catalytic region (PDB codes: 3PE3 and 3PE4) [536]. Additional reports discussing the mechanism underlining OGT and OGA activities as well as small-molecule inhibitors and drug discovery methodologies have recently appeared [537-543]. Glycosyltransferases have been recently used to derive glycosylated analogues of novobiocin with improved activity against several cancer cell lines [544]. While glycosylation represents an emerging PTM of histones that is expected to provide new biological clues in cancer epigenetics, both OGT and OGA have not yet been validated for drug design purposes. Nevertheless, small inhibitors for both enzymes, e.g. by PUGNAc and related derivatives, have been described in literature [521,545-548]. It is expected that the discovery of other inhibitors of these enzymes, for use as cellular probes, will help the full understanding of O-GlcNAc as a covalent histone modification and will contribute to foster research toward new epigenetic therapeutic agents.

Carbonylation

Covalent modification of cysteines by reactive carbonyl species (RCS) is known as carbonylation. Production of RCS is a feature of redox signaling by enzymes like peroxiredoxins, tyrosine phosphatases/kinases and transcription factors (e.g. p53, NFkB and Nrf2) [549,550]. Intracellular levels of RCS are originated from non-enzymatic and enzymatic peroxidation of lipids, especially arachidonic acid; this process generates unsaturated aldehydes (enals), like 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4HNE), crotonaldehyde and acrolein, as well as unsaturated ketones (enone), like cyclopentenone prostaglandins. RCSs are able to act on membrane and cytosolic proteins, while little is known about the actions of RCS on nuclear proteins and the overall extent of changes in cell signaling and gene expression. Histones have been found to undergo carbonylation [549-551]. However, differently to other PTMs, carbonylation occurs without the specific action of enzymes as RCSs are directly responsible for the chemical attack of histone modification sites. In addition, the absence of enzymes that oppose histones carbonylation seems to predispose carbonylated histones to accumulate. This fact was observed in rat pheochromocytoma cells following alkylating stress [550].

Because carbonylation is in general a hallmark of protein oxidation it has been mostly connected to aging, inflammaging, caloric restriction and age-related pathologies [552]. There is scarse knowledge about how carbonylation enzymes might govern other cellular redox processes, including those leading to cancer via histone covalent modifications.

Citrullination/Deimination