Abstract

A moderate increase in seawater temperature causes coral bleaching, at least partially through photobleaching of the symbiotic algae Symbiodinium spp. Photobleaching of Symbiodinium spp. is primarily associated with the loss of light-harvesting proteins of photosystem II (PSII) and follows the inactivation of PSII under heat stress. Here, we examined the effect of increased growth temperature on the change in sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. PSII inactivation and photobleaching under heat stress. When Symbiodinium spp. cells were grown at 25°C and 30°C, the thermal tolerance of PSII, measured by the thermal stability of the maximum quantum yield of PSII in darkness, was commonly enhanced in all six Symbiodinium spp. tested. In Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827, it took 6 h to acquire the maximum PSII thermal tolerance after transfer from 25°C to 30°C. The effect of increased growth temperature on the thermal tolerance of PSII was completely abolished by chloramphenicol, indicating that the acclimation mechanism of PSII is associated with the de novo synthesis of proteins. When CCMP827 cells were exposed to light at temperature ranging from 25°C to 35°C, the sensitivity of cells to both high temperature-induced photoinhibition and photobleaching was ameliorated by increased growth temperatures. These results demonstrate that thermal acclimation of Symbiodinium spp. helps to improve the thermal tolerance of PSII, resulting in reduced inactivation of PSII and algal photobleaching. These results suggest that whole-organism coral bleaching associated with algal photobleaching can be at least partially suppressed by the thermal acclimation of Symbiodinium spp. at higher growth temperatures.

Reef-building corals harbor symbiotic dinoflagellate algae of the genus Symbiodinium. Corals generally show a brownish coloration due to algal photosynthetic pigments, such as peridinin and chlorophylls a and c2 present in in situ Symbiodinium spp. However, under increased seawater temperatures, corals become pale through the loss of Symbiodinium spp. cells and/or the loss of photosynthetic pigments of in situ Symbiodinium spp. (Glynn, 1993, 1996; Hoeghguldberg, 1999; Fitt et al., 2001; Coles and Brown, 2003). This phenomenon is so-called coral bleaching. Since a healthy algae-coral symbiotic relationship is important for coral survival (Yellowlees et al., 2008), severe coral bleaching leads to the mortality of corals and even the destruction of entire coral reef ecosystems. The frequency and intensity of coral bleaching have been increasing since the early 1980s, and it is predicted to become more severe in the future due to ongoing global climate change and warming (Hughes et al., 2003). Coral reef ecosystems are in serious decline, with an estimated 30% already severely damaged, and it is predicted that globally as much as 60% of the world’s coral reef ecosystems may be lost by 2030 (Hughes et al., 2003).

Coral bleaching caused by heat stress is at least partially attributed to the photobleaching of photosynthetic pigments in Symbiodinium spp. within corals (Kleppel et al., 1989; Porter et al., 1989; Fitt et al., 2001; Takahashi et al., 2004; Venn et al., 2006). The photobleaching commonly occurs in photosynthetic organisms under conditions where the absorbed light energy for photosynthesis is in excess of the capacity to use it, particularly under environmental stress conditions in high light (Niyogi, 1999). In cultured Symbiodinium spp. cells, heat stress-associated algal photobleaching is attributed to the loss of major light-harvesting proteins, such as the peridinin-chlorophyll a-binding proteins and the chlorophyll a-chlorophyll c2-peridin protein complexes (Takahashi et al., 2008). A recent study has also demonstrated that the heat stress-associated loss of light-harvesting proteins in Symbiodinium spp. is attributed to suppression of the de novo synthesis of light-harvesting proteins but not acceleration of the photodamage and subsequent degradation of light-harvesting proteins (Takahashi et al., 2008). High-temperature sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. cells to photobleaching differs among Symbiodinium spp., and this is at least partially attributed to the thermal sensitivity of the de novo synthesis of light-harvesting proteins (Takahashi et al., 2008).

Heat stress-associated photobleaching in Symbiodinium spp. follows severe photoinhibition of PSII (Takahashi et al., 2008). The extent of photoinhibition is a result of the dynamic balance between the rate of photodamage to PSII and the rate of its repair. In plants and green algae, the PSII repair process is primarily composed of the degradation and the de novo synthesis of the D1 proteins in photodamaged PSII protein complexes (Aro et al., 1993; Takahashi and Murata, 2008; Takahashi and Badger, 2011). However, this differs in Symbiodinium spp., in that the photodamaged PSII can be repaired without the de novo synthesis of D1 proteins (Takahashi et al., 2009b). Furthermore, a part of photodamaged PSII is repaired without protein synthesis (Takahashi et al., 2009b), indicating that Symbiodinium spp. have a unique PSII repair mechanism. In Symbiodinium spp. found within corals and also in culture, heat stress accelerates photoinhibition at least partially through the suppression of PSII repair (Warner et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 2004, 2009b). However, the sensitivity of PSII repair to heat stress differs among Symbiodinium spp. and is strongly related to the sensitivity of PSII to photoinhibition under heat stress (Takahashi et al., 2009b).

The high-temperature sensitivity of corals to bleaching is changed by their growth temperature, and this is suggested to be due to changing in situ Symbiodinium spp. populations from heat-sensitive to heat-resistant ecotypes (Baker, 2001, 2003; Baker et al., 2004; Berkelmans and van Oppen, 2006; Jones et al., 2008; Jones and Berkelmans, 2010). However, thermal tolerance of the population might also be enhanced by thermal acclimation mechanism(s) associated with both the corals and Symbiodinium spp., although experimental data that directly support this hypothesis are lacking. In this study, we examine the effect of increased growth temperature (thermal acclimation treatment) on the extent of heat stress-associated algal photobleaching using cultured Symbiodinium spp. Our results demonstrate that Symbiodinium spp. commonly have thermal acclimation mechanisms that enhance the high-temperature tolerance of PSII and alleviate heat stress-associated photobleaching. Our results strongly suggest that thermal acclimation of Symbiodinium spp. plays a role in alleviating algal photobleaching-associated coral bleaching under heat stress.

RESULTS

Effect of Growth Temperature on Thermal Tolerance of PSII

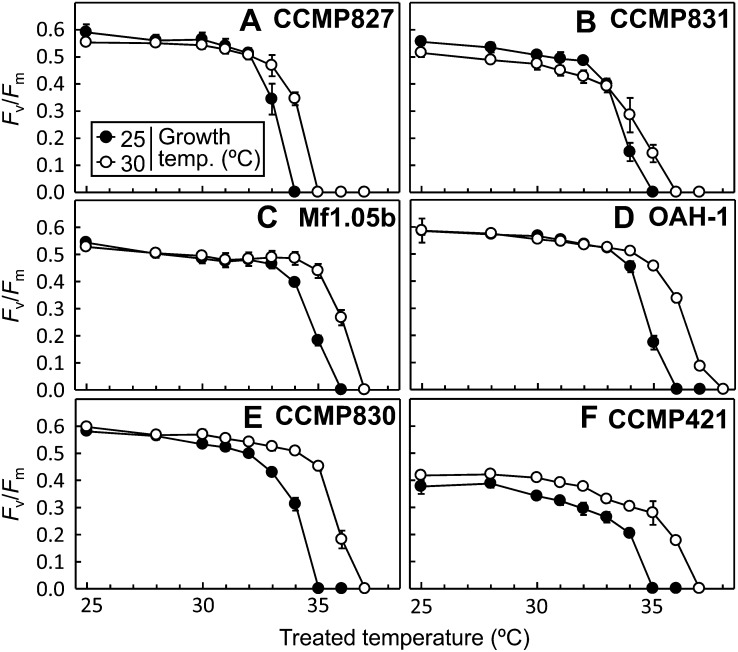

To determine if the growth of Symbiodinium spp. at moderately elevated temperatures results in an acclimatory shift in the thermal tolerance of PSII, the maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) was measured in six different Symbiodinium spp. grown at 25°C or 30°C after exposure treatments at temperatures ranging from 25°C to 38°C for 1 h in darkness (Fig. 1). In Symbiodinium spp. cells grown at 25°C, the measured Fv/Fm remained unchanged up to 33°C in all species but declined to zero at 34°C in CCMP827, at 35°C in CCMP831, CCMP830, and CCMP421, and at 36°C in Mf1.05b and OAH-1. When Symbiodinium spp. cells were grown at 30°C for 8 d, the thermal tolerance of PSII (the minimum temperature that leads to a reduction of Fv/Fm to zero) increased 1°C in CCMP827, CCMP831, and Mf1.05b and 2°C in OAH-1, CCMP830, and CCMP421. These results demonstrate that all Symbiodinium spp. tested in our study commonly had a thermal acclimation mechanism that was able to improve the high-temperature tolerance of PSII. Furthermore, our results indicate that the thermal acclimation ability shows slight differences among Symbiodinium spp.

Figure 1.

Effect of growth temperature on the thermal tolerance of PSII in six different Symbiodinium spp. Cells were grown at 25°C or 30°C for 8 d. Fv/Fm was measured after incubation of cells for 1 h in darkness at temperatures ranging from 25°C to 38°C. Values are means ± sd from three independent experiments.

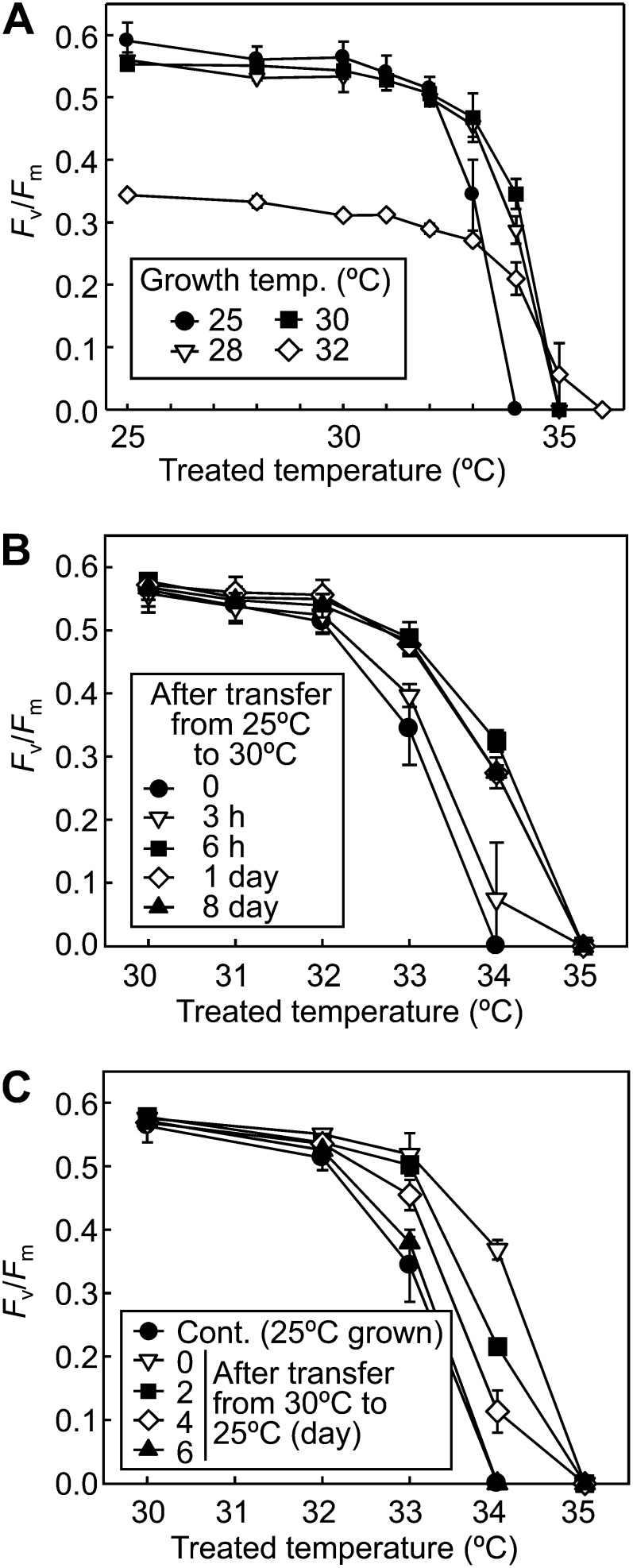

To further understand the thermal acclimation mechanism in Symbiodinium spp., we examined the effect of different growth temperatures ranging from 25°C to 32°C on the thermal tolerance of PSII using Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 (Fig. 2A). When growth temperature increased from 25°C to 28°C, the thermal tolerance of PSII apparently increased 1°C. There was no difference in the thermal tolerance of PSII between cells grown at 28°C and 30°C. In cells grown at 32°C, the thermal tolerance of PSII was improved as much as in cells grown at 28°C and 30°C, but the Fv/Fm value after incubation at each growth temperature was much lower in cells grown at 32°C, indicating that PSII was severely impaired in cells grown at 32°C. These results demonstrated that a small increase (less than 3°C) in growth temperature is enough to fully activate the thermal acclimation mechanism in CCMP827. To test whether the minimum temperature that fully activates the thermal acclimation mechanism is common in Symbiodinium spp., we performed the same experiments in OAH-1 and CCMP830. In OAH-1, the thermal tolerance showed improvement in cells grown at 30°C compared with those at 28°C (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Furthermore, in CCMP830, the thermal tolerance was increased further in cells grown at 32°C (Supplemental Fig. S1B). These results demonstrate that the minimum temperature that fully activates the thermal acclimation mechanism shows differences among Symbiodinium spp.

Figure 2.

Thermal acclimation of PSII stability in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827. A, Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells were grown at different temperatures ranging from 25°C to 32°C for 8 d. B, Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells grown at 25°C were transferred to 30°C and incubated for different periods (3 h, 6 h, 1 d, or 8 d). C, Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells grown at 30°C for 3 d were transferred to 25°C and incubated for different periods (2, 4, or 6 d). Control (Cont.) results are from experiments with cells continuously grown at 25°C. Fv/Fm was measured after incubation for 1 h in darkness at temperatures ranging from 25°C to 35°C. Values are means ± sd from three independent experiments.

We examined how long it takes to acquire the maximum thermal tolerance of PSII in CCMP827 (Fig. 2B). Cells grown at 25°C were transferred to 30°C and incubated for 3 h, 6 h, 1 d, or 8 d. The thermal tolerance of PSII was slightly enhanced after 3 h of incubation at 30°C and was significantly enhanced after 6 h. Further incubation had no effect on the thermal tolerance of PSII up to 8 d. These results demonstrate that the process of thermal acclimation was completed after 6 h in CCMP827.

We examined how long it takes to lose the acquired thermal tolerance of PSII in CCMP827 (Fig. 2C). Cells grown at 30°C for 3 d were transferred to 25°C and incubated for 2, 4, or 6 d. The thermal tolerance of PSII was slightly reduced after 2 d and was significantly reduced after 4 d. After 6 d of incubation at 25°C, there was no significant difference in the thermal tolerance of PSII with cells continuously grown at 25°C. These results demonstrate that the acquired thermal tolerance of PSII is completely lost in 6 d in CCMP827.

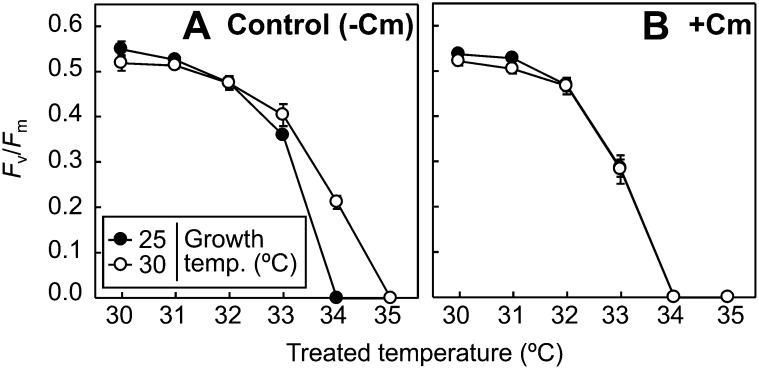

Thermal acclimation may be associated with the de novo synthesis of proteins. To examine this, CCMP827 cells were transferred from 25°C to 30°C and incubated in the presence or absence of chloramphenicol in darkness for 12 h. In general, chloramphenicol inhibits the de novo synthesis of chloroplast-encoded proteins. However, in Symbiodinium spp., chloramphenicol has been demonstrated to inhibit the de novo synthesis of both chloroplast- and nucleus-encoded proteins (Takahashi et al., 2009b). Since chloramphenicol inhibits protein synthesis-dependent repair of photodamaged PSII and also causes photoinhibition in the light, experiments were carried out under darkness. In the absence of chloramphenicol, the thermal tolerance of PSII was enhanced by moderately increased temperature in darkness (Fig. 3A) to an extent similar to that in the light (Figs. 1A and 2B), indicating that the thermal acclimation of PSII in Symbiodinium spp. is not light dependent. The effect of moderately increased growth temperature on the thermal tolerance of PSII was completely abolished by chloramphenicol (Fig. 3B). These results demonstrate that the thermal acclimation mechanism in CCMP827 is associated with the de novo synthesis of proteins.

Figure 3.

Effect of moderately increased growth temperature on the thermal tolerance of PSII in the presence and absence of chloramphenicol (Cm) in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827. Fv/Fm was measured in CCMP827 cells incubated at 25°C or 30°C for 12 h in darkness in the absence (A) or presence of 1 mm chloramphenicol (B). Values are means ± sd from three independent experiments.

Thermal Acclimation Helps Maintain Higher Photosynthetic Performance under Heat Stress in Light

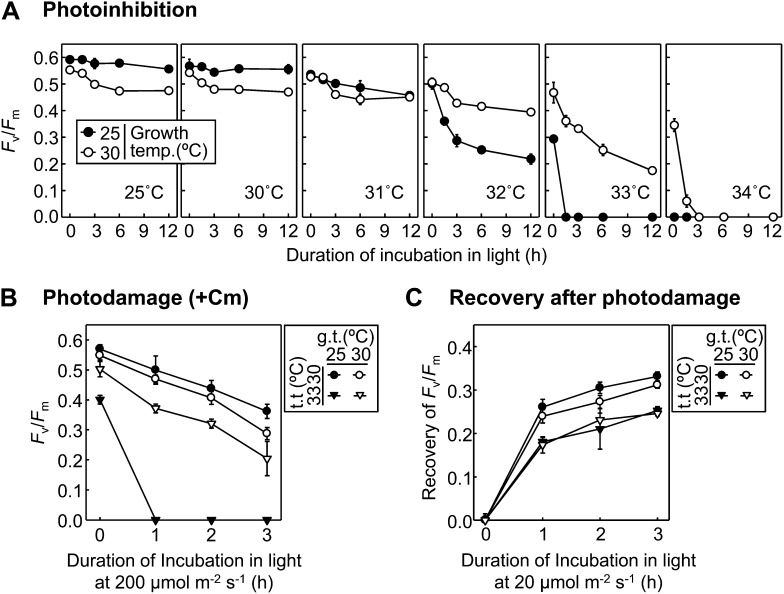

An increase in seawater temperature causes acceleration of the photoinhibition of PSII in the light in Symbiodinium spp. (Warner et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 2004, 2009b). To examine the effects of thermal acclimation on the sensitivity of PSII to photoinhibition under heat stress, the extent of photoinhibition was monitored in CCMP827 cells grown at 25°C or 30°C at temperatures ranging from 25°C to 34°C under exposure to light (Fig. 4A). In cells grown at 25°C, the extent of photoinhibition (decrease in the value of Fv/Fm during light exposure) was drastically enhanced at temperatures above 31°C. However, in cells grown at 30°C, the temperature that caused a rapid onset of photoinhibition was 1°C higher than that in cells grown at 25°C. These results demonstrate that thermal acclimation not only improves the stability of PSII in the dark but also alleviates photoinhibition of PSII in the light under heat stress in CCMP827. Thus, thermal acclimation improves photosynthetic performance under heat stress conditions through enhancing the thermal tolerance of PSII (Figs. 1A and 2A) and suppressing the thermal sensitivity of PSII to photoinhibition in the light in CCMP827 (Fig. 4A). However, this was different in other Symbiodinium spp. (Supplemental Fig. S2). In OAH-1 and CCMP830 cells, an increase in growth temperature did not help alleviate photoinhibition under heat stress (Supplemental Fig. S2), although it enhanced the thermal tolerance of PSII (Fig. 1, D and E). These results demonstrate that thermal acclimation improves photosynthetic performance in OAH-1 and CCMP830 primarily through enhancing the thermal tolerance of PSII but not through suppressing the thermal sensitivity of PSII to photoinhibition in the light.

Figure 4.

Effect of moderately increased growth temperature on the thermal sensitivity of PSII to photoinhibition and subsequent repair in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827. CCMP827 cells grown at 25°C or 30°C for more than 3 d were used for experiments. A, Cells were incubated at temperatures ranging from 25°C to 34°C in darkness for 1 h and then exposed to light at 200 µmol m−2 s−1 for 12 h. B, Cells were incubated at 30°C or 33°C in darkness for 1 h and then exposed to light at 200 µmol m−2 s−1 for 3 h in the presence of 1 mm chloramphenicol. C, Cells were preexposed to light at 2,000 µmol m−2 s−1 at their respective growth temperatures for 1 h. Cells were then incubated at 30°C or 33°C in darkness for 1 h before monitoring the recovery of Fv/Fm for 3 h at 20 µmol m−2 s−1. In all experiments, Fv/Fm was measured after 10 min of incubation in darkness. Values are means ± sd from three independent experiments. g.t., Growth temperature; t.t., treated temperature.

To further understand how thermal acclimation alleviates photoinhibition under heat stress, the thermal sensitivity of photoinhibition in the presence of chloramphenicol was examined in CCMP827 cells grown at 25°C or 30°C (Fig. 4B). When cells grown at 25°C and 30°C were exposed to light at 30°C, there was no difference in the extent of photoinhibition in the presence of chloramphenicol between them. However, when cells were exposed to light at 33°C, the extent of photoinhibition was much higher in cells grown at 25°C than 30°C. These results show that thermal acclimation reduces photoinhibition in the presence of chloramphenicol under heat stress in CCMP827. As chloramphenicol inhibits the protein synthesis-dependent repair of photodamaged PSII, it is possible that thermal acclimation may suppress either or both acceleration of photodamage and/or inhibition of the protein synthesis-independent repair under heat stress.

To examine the effect of growth temperatures (25°C and 30°C) on the sensitivity of the PSII repair process to heat stress, we monitored the recovery of Fv/Fm after photoinhibition treatment by strong light in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 (Fig. 4C). Cells grown at 25°C and 30°C were exposed to strong light (2,000 µmol m−2 s−1) at each growth temperature for 1 h. Cells were then preincubated in darkness at 30°C or 33°C for 1 h and subsequently exposed to low light (20 µmol m−2 s−1) to allow repair. The value of Fv/Fm before the low-light exposure (after photoinhibition and preincubation treatments) was 40% of the initial level in all conditions except at 33°C in cells grown at 25°C (in this case, Fv/Fm declined to 20% of initial values). This is presumably because PSII is thermally inactivated under 33°C in cells grown at 25°C, as shown in Figure 1A. In cells grown at both 25°C and 30°C, the recovery of Fv/Fm was significantly lower at 33°C than 30°C, indicating that heat stress reduces the repair of photodamaged PSII in CCMP827 cells (Fig. 4C). Importantly, there was no effect of growth temperature on the recovery of Fv/Fm at either 30°C or 33°C (Fig. 4C). This demonstrates that thermal acclimation had no influence on the sensitivity of PSII repair to heat stress. Thus, in the presence of chloramphenicol, suppression of heat stress-associated photoinhibition by increased growth temperature (Fig. 4B) could be attributed to reducing photodamage to PSII caused by heat stress. This demonstrates that heat stress accelerates the photoinhibition process through both increasing photodamage to PSII and reducing the PSII repair process and that, as a consequence, thermal acclimation alleviates photoinhibition through avoiding acceleration of photodamage to PSII under heat stress.

Thermal Acclimation Alleviates Photobleaching under Heat Stress

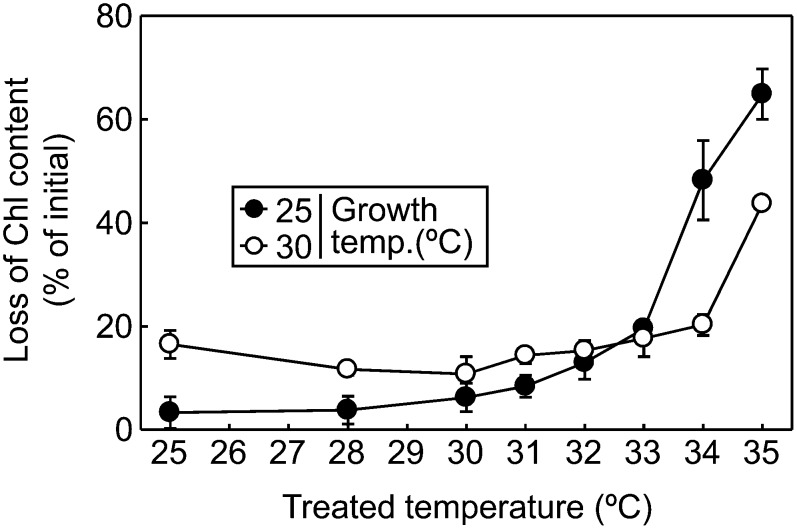

A moderate increase in seawater temperature causes acceleration of photobleaching in Symbiodinium spp. (Takahashi et al., 2004, 2008). To examine the effect of thermal acclimation processes on the extent of photobleaching under heat stress, total chlorophyll (chlorophylls a and c2) content was measured before and after light exposure for 12 h at temperatures ranging from 25°C to 35°C in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells grown at 25°C or 30°C (Fig. 5). In cells grown at 25°C, loss of chlorophyll content was drastically enhanced at temperatures above 33°C, and 50% of initial chlorophyll content was lost at 34°C. However, in cells grown at 30°C, the temperature that initiated the drastic loss of chlorophyll was 1°C higher than that in cells grown at 25°C, and only 20% of initial chlorophyll content was lost at 34°C. These results demonstrated that thermal acclimation increased the thermal threshold for initiating photobleaching in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827. Similar results were obtained in Symbiodinium spp. OAH-1 and CCMP830 (Supplemental Fig. S3), where the thermal threshold for initiating drastic photobleaching increased 1°C after growing cells at moderately increased temperatures.

Figure 5.

Effect of moderately increased growth temperature on the thermal sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. to photobleaching. Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells grown at 25°C or 30°C were incubated at different temperatures ranging from 25°C to 35°C for 1 h in darkness. Subsequently, cells (5 µg chlorophyll mL−1) were exposed to light at 200 µmol m−2 s−1 for 12 h at the same temperature. Total chlorophyll content (chlorophylls a and c2) was measured before and after light exposure, and the loss of chlorophyll content (percentage of initial) was calculated. Values are means ± sd from three independent experiments.

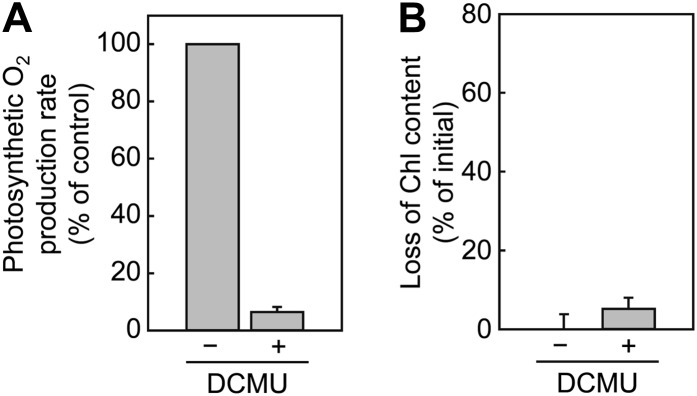

Photobleaching of Symbiodinium spp. Is Not Associated with Inactivation of PSII

Photobleaching of Symbiodinium spp. commonly follows severe inactivation of PSII under heat stress. To determine whether the heat stress-associated photobleaching is due to inactivation of PSII, the effect of 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) on the extent of photobleaching was examined. When Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells were incubated with 5 µm DCMU, the photosynthetic oxygen production rate decreased to 6% of that in the absence of DCMU (Fig. 6A). After incubation of light at 200 µmol m−2 s−1 for 12 h, DCMU slightly enhanced the extent of photobleaching (Fig. 6B). However, the effect of DCMU on photobleaching was much lower than the effect of heat stress on photobleaching in Figure 5. These results demonstrate that heat stress-associated photobleaching in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 is not due to inactivation of PSII.

Figure 6.

Effect of DCMU on the sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. to photobleaching. Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells grown at 25°C were incubated for 1 h in darkness with (+) or without (−) 5 µm DCMU and used for experiments. All experiments were carried out at 25°C. A, Effect of DCMU on photosynthesis. Photosynthetic oxygen production rate was measured under the light at 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1. The photosynthetic oxygen production rate was 115 ± 7.6 µmol oxygen mg−1 chlorophyll h−1 in the absence of DCMU (control). B, Effect of DCMU on photobleaching. Cells (5 µg chlorophyll mL−1) were exposed to light at 200 µmol m−2 s−1 for 12 h. Total chlorophyll content (chlorophylls a and c2) was measured before and after light exposure, and the loss of chlorophyll content (percentage of initial) was calculated. Values are means ± sd from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Thermal Acclimation Alleviates Photobleaching in Symbiodinium spp. under Heat Stress

Heat stress causes coral bleaching at least partially through the acceleration of photobleaching in Symbiodinium spp. living within corals (Kleppel et al., 1989; Porter et al., 1989; Fitt et al., 2001; Takahashi et al., 2004; Venn et al., 2006). In this study, we demonstrate that the thermal tolerance threshold of Symbiodinium spp. for initiating photobleaching increases after growing at moderately increased temperature (Fig. 5). Extrapolation of our results strongly suggests that photobleaching-associated coral bleaching can be alleviated by thermal acclimation of Symbiodinium spp. growing within corals.

Consistent with previous studies (Takahashi et al., 2008), the sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. to bleaching under heat stress differs among species: CCMP827 (Fig. 5) showed more severe photobleaching under heat stress conditions than OAH-1 (Supplemental Fig. S3A) and CCMP830 (Supplemental Fig. S3B) in cells grown at 25°C. In all three Symbiodinium spp. tested in this study, thermal acclimation commonly showed a 1°C increase in the thermal threshold for initiating photobleaching (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S3). However, the results demonstrate that different thermal sensitivity among Symbiodinium spp. is not due to different thermal acclimation ability.

The thermal sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. to photobleaching corresponds with the sensitivity of PSII to inactivation under heat stress (Chen et al., 2004; Takahashi et al., 2008). Since the process of photobleaching occurs after severe inactivation of PSII under heat stress, inactivation of PSII is expected to cause photobleaching in Symbiodinium spp. However, in this study, inhibition of photosynthetic oxygen production at PSII by DCMU had little effect on the extent of photobleaching under our experimental conditions (Fig. 6B). In a previous study using Symbiodinium spp., heat stress-associated photobleaching was demonstrated to be primarily due to suppression of the de novo synthesis of light-harvesting proteins in thylakoid membranes (Takahashi et al., 2008). However, there was no effect of DCMU on the de novo synthesis of any membrane proteins (Supplemental Fig. S4). Therefore, it is likely that heat stress-associated photobleaching of Symbiodinium spp. is not due to a lack of PSII activity. Thus, the alleviation of photobleaching in thermally acclimated Symbiodinium spp. cells (Fig. 5) is not due to remaining PSII activity. Our results suggest that heat stress causes both inactivation of PSII and photobleaching with a time delay. This might be because photobleaching is a slow process through proteolytic degradation of light-harvesting proteins, while inactivation of PSII is a quick process though nonenzymatic photochemical reactions.

In OAH-1 and CCMP830, the thermal threshold for initiating apparent photobleaching increased by 1°C after thermal acclimation (Supplemental Fig. S3), although the thermal tolerance of PSII in the dark increased 2°C to 3°C (Supplemental Fig. S1). These results demonstrate that the thermal tolerance of PSII that was examined in the dark does not always correspond with photobleaching sensitivity under heat stress. This lack of correlation might be because the thermal sensitivity of PSII to inactivation is determined not only by the thermal tolerance of PSII but also the thermal sensitivity of PSII to photoinhibition. In OAH-1 and CCMP830, PSII performance was much higher in cells grown at 30°C or 32°C than in cells grown at 25°C under heat stress (more than 34°C) before light exposure (Supplemental Fig. S2). However, the difference was gradually minimized during light exposure due to the acceleration of photoinhibition in cells grown at higher temperature (Supplemental Fig, S2). Thus, the thermal sensitivity of PSII in Symbiodinium spp. differs before and after light exposure treatments. The thermal sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. to photobleaching seems to correspond more closely with the thermal tolerance of PSII in the light rather than its stability in the dark.

How Does Thermal Acclimation Enhance the Thermal Tolerance of PSII in Symbiodinium spp.?

Moderately increased growth temperature has been demonstrated to enhance the thermal tolerance of PSII in photosynthetic organisms (Armond et al., 1978; Nishiyama et al., 1999; Tanaka et al., 2000; Kimura et al., 2002; Nanjo et al., 2010), including Symbiodinium spp. (Díaz-Almeyda et al., 2011). In this study, small increases in temperature (less than 3°C) were found to be sufficient to activate the thermal acclimation mechanism of PSII in Symbiodinium spp. (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we found that it takes only 6 h to acquire the maximum thermal tolerance of PSII in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 (Fig. 2B). The thermal acclimation mechanism of Symbiodinium spp. was associated with the de novo synthesis of proteins (Fig. 3), as has been shown in other photosynthetic organisms (Tanaka et al., 2000; Nanjo et al., 2010). Furthermore, the thermal tolerance of PSII was enhanced in darkness (Fig. 3A) to a similar extent as in the light (Figs. 1A and 2). Thus, the synthesis of proteins that are responsible for the thermal acclimation of PSII in Symbiodinium spp. is regulated solely by temperature, as has been shown in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Tanaka et al., 2000). Our results suggest that Symbiodinium spp. cells acquire the thermal tolerance of PSII at any time of the day under increased seawater temperature.

A variety of factors have been shown to enhance the thermal tolerance of PSII in studies using plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, such as psbU protein in PSII (Nishiyama et al., 1997; Kimura et al., 2002), lipid compounds (Sato et al., 2003; Sakurai et al., 2007a, 2007b; Mizusawa et al., 2009), xanthophyll zeaxanthin (Havaux et al., 1996; Havaux, 1998), heat shock proteins (Stapel et al., 1993; Eriksson and Clarke, 1996; Heckathorn et al., 1998; Tsvetkova et al., 2002), σ factors (Singh et al., 2006; Tuominen et al., 2006), and isoprene (Sharkey and Singsaas, 1995). In Symbiodinium spp., membrane lipid composition has been suggested to determine the thermal tolerance of PSII (Tchernov et al., 2004). However, it is still controversial whether changes in lipid composition are responsible for the thermal acclimation of PSII in Symbiodinium spp. (Díaz-Almeyda et al., 2011). In cyanobacteria, the synthesis of fatty acids is involved, but stability increases of PSII are not associated with either the total amount of fatty acids or the levels of unsaturated fatty acids in thylakoid membrane (Nanjo et al., 2010). Models suggest that the synthesis of fatty acids is expected to be associated with binding the PSII-stabilizing proteins, such as lipoprotein. The inhibition of thermal acclimation of PSII by an inhibitor of protein synthesis, therefore, might be due to inhibition of the synthesis of proteins associated with the synthesis of fatty acids or stabilizing PSII under heat stress (Nishiyama et al., 1999; Kimura et al., 2002; Nanjo et al., 2010).

Thermal Acclimation Decreases the Sensitivity of PSII to Photoinhibition under Heat Stress

Heat stress causes the acceleration of photoinhibition of PSII in cultured Symbiodinium spp. and in situ Symbiodinium spp. within corals (Warner et al., 1999; Takahashi et al., 2004, 2009b). Heat stress-associated photoinhibition in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells grown at 25°C was due to the acceleration of photodamage to PSII (Fig. 4B) and also through the inhibition of PSII repair (Fig. 4C). We found that increased growth temperature alleviates heat stress-associated photoinhibition (Fig. 4A) through suppressing photodamage to PSII (Fig. 4B) but not suppressing the inhibition of PSII repair (Fig. 4C). In Symbiodinium spp., heat stress has been demonstrated to damage thylakoid membranes (Tchernov et al., 2004), which impairs the generation of the proton gradient across the thylakoid membrane. Since impairment of the proton gradation causes the acceleration of photodamage to PSII (Takahashi et al., 2009a, 2009b), alleviation of thermal stress-associated photodamage to PSII in Symbiodinium spp. after growing at moderately increased temperature might be due to suppressing damage to thylakoid membranes under heat stress.

Thermal Acclimation of Symbiodinium spp. May Alleviate Coral Bleaching under Heat Stress

When corals are grown under moderately increased temperature, heat stress-associated coral bleaching is suppressed (Coles and Jokiel, 1978; Coles and Brown, 2003). Since the sensitivity of corals to bleaching under heat stress is changed by the thermal sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. living within corals and this differs among Symbiodinium spp., the sensitivity of corals to bleaching under heat stress can be decreased by changing the dominant in situ Symbiodinium spp. population from heat sensitive to heat tolerant (Baker, 2001, 2003; Baker et al., 2004; Berkelmans and van Oppen, 2006; Jones et al., 2008; Jones and Berkelmans, 2010). In this study, we found that the sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. to photobleaching under heat stress is suppressed by acclimation to moderately increased growth temperatures. In three cultured Symbiodinium spp. tested in this study, the thermal threshold for initiating apparent photobleaching commonly increased by 1°C after thermal acclimation (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S3). By extrapolation, these findings suggest that the threshold for initiating photobleaching-associated coral bleaching might increase by at least 1°C through a thermal acclimation process of Symbiodinium spp. within corals without involving a change in the overall Symbiodinium spp. population. It is still uncertain whether there are Symbiodinium spp. that show a greater acclimation ability and that increase their thermal threshold for initiating photobleaching by more than 1°C after thermal acclimation.

In this study, thermal acclimation was demonstrated to alleviate the inactivation of PSII through both enhancing the thermal tolerance of PSII (Fig. 1) and suppressing the photoinhibition of PSII (Fig. 4A) under heat stress. Since inactivation of PSII has been hypothesized to be a trigger of expulsion of Symbiodinium spp. from host cells (Brown, 1997; Hoeghguldberg, 1999; Warner et al., 1999), thermal acclimation of Symbiodinium spp. might also reduce coral bleaching that is associated with the loss of Symbiodinium spp. under heat stress. However, further study is needed to elucidate this hypothesis.

The thermal acclimation of Symbiodinium spp. occurs in a period of hours (Fig. 2B), while dominant Symbiodinium spp. within corals are changed in the order of days (Baker, 2003). Therefore, it is conceivable that thermal acclimation of Symbiodinium spp. and changes of dominant Symbiodinium spp. are associated with short- and long-term thermal acclimation, respectively, and that both help to alleviate coral bleaching under heat stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultures and Growth Conditions

Cultures of Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 (clade A), CCMP831 (clade A), CCMP830 (clade B), and CCMP421 (clade E) were obtained from the National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota (Tchernov et al., 2004). OAH-1 (clade B; Ishikura et al., 2004) and Mf1.05b (clade B; Voolstra et al., 2009) were gifts from Dr. Tadashi Maruyama and Dr. Mary Alice Coffroth, respectively. Clades of these Symbiodinium spp. cultures are according to previous studies (Ishikura et al., 2004; Tchernov et al., 2004; Voolstra et al., 2009). Symbiodinium spp. cells (200–400 mL) were grown in artificial seawater (sea salts; Sigma) containing Daigo’s IMK medium for marine microalgae (Wako) in 2-L shaker flasks with a filter cap under fluorescent light at 80 µmol photons m−2 s−1 with a light/dark cycle of 12 h/12 h. The flask was mixed once per day for aeration. Growth temperatures were controlled with an electronic aquarium heater (A-761; Hagen) in a 40-L aquarium tank. The cells were collected by filtration (0.22-µm Stericup; Millipore) during their midlogarithmic growth phase (less than 0.5 µg chlorophyll mL−1) and suspended in fresh growth medium for experiments.

Temperature Treatments

Freshly harvested cells were diluted to 5 µg chlorophyll mL−1, and equal volumes were incubated at different temperatures in darkness for 1 h before either being illuminated at 200 µmol photons m−2 s−1 with halogen lamps or maintained in darkness. All temperature treatments represented in each experiment were performed simultaneously using an aluminum gradient heat bar with glass vials containing cells at appropriate temperatures along the bar in wells and illuminated with halogen lamps from the top where necessary. Light intensity (400–700 nm) was measured with a LI-250 light meter (LI-COR).

Photoinhibition, Chlorophyll, and Photosynthetic Oxygen Production Rate Measurements

Fv/Fm was measured with a PAM-2000 chlorophyll fluorometer (Heinz Walz) after the cells had been incubated for 10 min in darkness. The concentrations of chlorophylls a and c2 were measured by treating cells collected by centrifugation (16,000g, 1 min) with 80% (v/v) methanol at 70°C for 10 min (Takahashi et al., 2008). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (16,000g, 1 min), the absorption spectrum of the supernatant was measured using a diode-array spectrophotometer (Cary 50 Bio; Varian), and the total chlorophyll a and c2 concentrations were calculated according to Jeffrey and Humphrey (1975). To measure the photosynthetic oxygen production rate, light-dependent oxygen production was measured in Symbiodinium spp. cells (10 µg of total chlorophyll a and c2 in 1 mL) with a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Hansatech Instruments) in a closed cuvette in the light at 1,000 µmol photons m−2 s−1 at 25°C.

Pulse Labeling of Proteins and Separation of Membrane Proteins

Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827 cells (5 µg chlorophyll mL−1) were incubated with or without 5 µm DCMU in the dark at 25°C for 1 h. Then, cells were exposed to light at 200 µmol photons m−2 s−1 in the presence of [35S]Met/Cys (10 mCi mL−1) at 25°C for 15 min. Cells were collected by centrifugation, and membrane proteins (corresponding to 1.5 µg of chlorophyll) were separated by NuPAGE Novex 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gel electrophoresis (Invitrogen; Takahashi et al., 2008). The gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 (GelCode Blue Stain Reagent; Thermo Scientific) and dried on paper with the gel dryer (model 583; Bio-Rad) at 80°C for 1 h. The dried gel was exposed to an imaging Screen-K (Kodak) and visualized with the Molecular Imager PharosFX Plus System (Bio-Rad).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Thermal acclimation of PSII stability in Symbiodinium sp. OAH-1 and CCMP830.

Supplemental Figure S2. Effect of moderately increased growth temperature on the thermal sensitivity of PSII to photoinhibition in Symbiodinium sp. OAH-1 and CCMP830.

Supplemental Figure S3. Effect of moderately increased growth temperature on the thermal sensitivity of Symbiodinium spp. to photobleaching.

Supplemental Figure S4. Effect of DCMU on the de novo synthesis of membrane proteins in Symbiodinium sp. CCMP827.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tadashi Maruyama (Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology) and Dr. Mary Alice Coffroth (University of Buffalo) for providing Symbiodinium spp. cell cultures.

Glossary

- Fv/Fm

maximum quantum yield of PSII

- DCMU

3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea

References

- Armond PA, Schreiber U, Björkman O. (1978) Photosynthetic acclimation to temperature in the desert shrub, Larrea divaricata. II. Light-harvesting efficiency and electron transport. Plant Physiol 61: 411–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aro EM, Virgin I, Andersson B. (1993) Photoinhibition of photosystem II: inactivation, protein damage and turnover. Biochim Biophys Acta 1143: 113–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AC. (2001) Reef corals bleach to survive change. Nature 411: 765–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AC. (2003) Flexibility and specificity in coral-algal symbiosis: diversity, ecology, and biogeography of Symbiodinium. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 34: 661–689 [Google Scholar]

- Baker AC, Starger CJ, McClanahan TR, Glynn PW. (2004) Coral reefs: corals’ adaptive response to climate change. Nature 430: 741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkelmans R, van Oppen MJH. (2006) The role of zooxanthellae in the thermal tolerance of corals: a ‘nugget of hope’ for coral reefs in an era of climate change. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 273: 2305–2312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BE. (1997) Coral bleaching: causes and consequences. Coral Reefs 16: 129–138 [Google Scholar]

- Chen YB, Durnford DG, Koblizek M, Falkowski PG. (2004) Plastid regulation of Lhcb1 transcription in the chlorophyte alga Dunaliella tertiolecta. Plant Physiol 136: 3737–3750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles SL, Brown BE. (2003) Coral bleaching: capacity for acclimatization and adaptation. Adv Mar Biol 46: 183–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles SL, Jokiel PL. (1978) Synergistic effects of temperature, salinity and light on hermatypic coral Montipora verrucosa. Mar Biol 49: 187–195 [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Almeyda E, Thomé PE, El Hafidi M, Iglesias-Prieto R. (2011) Differential stability of photosynthetic membranes and fatty acid composition at elevated temperature in Symbiodinium. Coral Reefs 30: 217–225 [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson MJ, Clarke AK. (1996) The heat shock protein ClpB mediates the development of thermotolerance in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J Bacteriol 178: 4839–4846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitt WK, Brown BE, Warner ME, Dunne RP. (2001) Coral bleaching: interpretation of thermal tolerance limits and thermal thresholds in tropical corals. Coral Reefs 20: 51–65 [Google Scholar]

- Glynn PW. (1993) Coral reef bleaching: ecological perspectives. Coral Reefs 12: 1–17 [Google Scholar]

- Glynn PW. (1996) Coral reef bleaching: facts, hypotheses and implications. Glob Change Biol 2: 495–509 [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M. (1998) Carotenoids as membrane stabilizers in chloroplasts. Trends Plant Sci 3: 147–151 [Google Scholar]

- Havaux M, Tardy F, Ravenel J, Chanu D, Parot P. (1996) Thylakoid membrane stability to heat stress studied by flash spectroscopic measurements of the electrochromic shift in intact potato leaves: influence of the xanthophyll content. Plant Cell Environ 19: 1359–1368 [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn SA, Downs CA, Sharkey TD, Coleman JS. (1998) The small, methionine-rich chloroplast heat-shock protein protects photosystem II electron transport during heat stress. Plant Physiol 116: 439–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeghguldberg O. (1999) Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar Freshw Res 50: 839–866 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TP, Baird AH, Bellwood DR, Card M, Connolly SR, Folke C, Grosberg R, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Jackson JBC, Kleypas J, et al. (2003) Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 301: 929–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikura M, Hagiwara K, Takishita K, Haga M, Iwai K, Maruyama T. (2004) Isolation of new Symbiodinium strains from tridacnid giant clam (Tridacna crocea) and sea slug (Pteraeolidia ianthina) using culture medium containing giant clam tissue homogenate. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 6: 378–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey SW, Humphrey GF. (1975) New spectrophotometric equations for determining chlorophylls a, b, c1 and c2 in higher plants, algae and natural phytoplankton. Biochem Physiol Pflanz 167: 191–194 [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Berkelmans R. (2010) Potential costs of acclimatization to a warmer climate: growth of a reef coral with heat tolerant vs. sensitive symbiont types. PLoS ONE 5: e10437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AM, Berkelmans R, van Oppen MJH, Mieog JC, Sinclair W. (2008) A community change in the algal endosymbionts of a scleractinian coral following a natural bleaching event: field evidence of acclimatization. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 275: 1359–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A, Eaton-Rye JJ, Morita EH, Nishiyama Y, Hayashi H. (2002) Protection of the oxygen-evolving machinery by the extrinsic proteins of photosystem II is essential for development of cellular thermotolerance in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 932–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleppel GS, Dodge RE, Reese CJ. (1989) Changes in pigmentation associated with the bleaching of stony corals. Limnol Oceanogr 34: 1331–1335 [Google Scholar]

- Mizusawa N, Sakata S, Sakurai I, Sato N, Wada H. (2009) Involvement of digalactosyldiacylglycerol in cellular thermotolerance in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Arch Microbiol 191: 595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjo Y, Mizusawa N, Wada H, Slabas AR, Hayashi H, Nishiyama Y. (2010) Synthesis of fatty acids de novo is required for photosynthetic acclimation of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 to high temperature. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797: 1483–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y, Los DA, Hayashi H, Murata N. (1997) Thermal protection of the oxygen-evolving machinery by PsbU, an extrinsic protein of photosystem II, in Synechococcus species PCC 7002. Plant Physiol 115: 1473–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y, Los DA, Murata N. (1999) PsbU, a protein associated with photosystem II, is required for the acquisition of cellular thermotolerance in Synechococcus species PCC 7002. Plant Physiol 120: 301–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi KK. (1999) Photoprotection revisited: genetic and molecular approaches. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 333–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JW, Fitt WK, Spero HJ, Rogers CS, White MW. (1989) Bleaching in reef corals: physiological and stable isotopic responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 9342–9346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai I, Mizusawa N, Ohashi S, Kobayashi M, Wada H. (2007a) Effects of the lack of phosphatidylglycerol on the donor side of photosystem II. Plant Physiol 144: 1336–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai I, Mizusawa N, Wada H, Sato N. (2007b) Digalactosyldiacylglycerol is required for stabilization of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II. Plant Physiol 145: 1361–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Aoki M, Maru Y, Sonoike K, Minoda A, Tsuzuki M. (2003) Involvement of sulfoquinovosyl diacylglycerol in the structural integrity and heat-tolerance of photosystem II. Planta 217: 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Singsaas EL. (1995) Why plants emit isoprene. Nature 374: 769 [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Summerfield TC, Li H, Sherman LA. (2006) The heat shock response in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 and regulation of gene expression by HrcA and SigB. Arch Microbiol 186: 273–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapel D, Kruse E, Kloppstech K. (1993) The protective effect of heat-shock proteins against photoinhibition under heat-shock in barley (Hordeum vulgare). J Photochem Photobiol B 21: 211–218 [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Badger MR. (2011) Photoprotection in plants: a new light on photosystem II damage. Trends Plant Sci 16: 53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Milward SE, Fan DY, Chow WS, Badger MR. (2009a) How does cyclic electron flow alleviate photoinhibition in Arabidopsis? Plant Physiol 149: 1560–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Murata N. (2008) How do environmental stresses accelerate photoinhibition? Trends Plant Sci 13: 178–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Nakamura T, Sakamizu M, van Woesik R, Yamasaki H. (2004) Repair machinery of symbiotic photosynthesis as the primary target of heat stress for reef-building corals. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 251–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Whitney S, Itoh S, Maruyama T, Badger M. (2008) Heat stress causes inhibition of the de novo synthesis of antenna proteins and photobleaching in cultured Symbiodinium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4203–4208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Whitney SM, Badger MR. (2009b) Different thermal sensitivity of the repair of photodamaged photosynthetic machinery in cultured Symbiodinium species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 3237–3242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Nishiyama Y, Murata N. (2000) Acclimation of the photosynthetic machinery to high temperature in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii requires synthesis de novo of proteins encoded by the nuclear and chloroplast genomes. Plant Physiol 124: 441–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchernov D, Gorbunov MY, de Vargas C, Narayan Yadav S, Milligan AJ, Häggblom M, Falkowski PG. (2004) Membrane lipids of symbiotic algae are diagnostic of sensitivity to thermal bleaching in corals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 13531–13535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetkova NM, Horváth I, Török Z, Wolkers WF, Balogi Z, Shigapova N, Crowe LM, Tablin F, Víerling E, Crowe JH, et al. (2002) Small heat-shock proteins regulate membrane lipid polymorphism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 13504–13509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen I, Pollari M, Tyystjärvi E, Tyystjärvi T. (2006) The SigB sigma factor mediates high-temperature responses in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. FEBS Lett 580: 319–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venn AA, Wilson MA, Trapido-Rosenthal HG, Keely BJ, Douglas AE. (2006) The impact of coral bleaching on the pigment profile of the symbiotic alga, Symbiodinium. Plant Cell Environ 29: 2133–2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voolstra CR, Schwarz JA, Schnetzer J, Sunagawa S, Desalvo MK, Szmant AM, Coffroth MA, Medina M. (2009) The host transcriptome remains unaltered during the establishment of coral-algal symbioses. Mol Ecol 18: 1823–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner ME, Fitt WK, Schmidt GW. (1999) Damage to photosystem II in symbiotic dinoflagellates: a determinant of coral bleaching. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 8007–8012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellowlees D, Rees TAV, Leggat W. (2008) Metabolic interactions between algal symbionts and invertebrate hosts. Plant Cell Environ 31: 679–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]