Abstract

Objectives

To be useable in clinical practise, treatments studied in trials must provide sufficient information to enable clinicians and researchers to replicate. We sought to assess the completeness of treatment descriptions in published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) using a checklist and to determine the extent to which peer reviewers and editors comment on the quality of reporting of treatments.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

Trials published in the BMJ, a general medical journal.

Participants

Fifty-one trials published in the BMJ were independently evaluated by two raters using a checklist. Reviewers’ and editors’ comments were also assessed for statements on treatment descriptions.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Proportion of trials rated as replicable (primary outcome).

Results

For 57% (29/51) of the papers, published treatment descriptions were not considered sufficient to allow replication. Most poorly described aspects were the actual procedures involved including the sequencing of the technique (what happened and when) and the physical or informational materials used (eg, training materials): 53% and 43% not clear, respectively. For a third of treatments, the dose/duration of individual sessions was not clear and for a quarter the schedule (interval, frequency, duration or timing) was not clear. Although the majority of problems were not picked up by reviewers and editors, when they were detected only about two-thirds were fixed before publication.

Conclusions

Journals wanting to publish the research of use to practising healthcare professionals need to pay more attention to descriptions of treatments. Our checklist, may be useful for reviewers, and editors and could help ensure that important details of treatments are provided before papers are in the public domain.

Keywords: General Medicine (see Internal Medicine), Journalism (see Medical Journalism)

Article summary.

Article focus

For clinicians applying treatments, or researchers wishing to replicate or extend research findings, adequate treatment descriptions in publications are vital.

We document the adequacy of reporting of different elements of descriptions of treatments in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in the BMJ; we determine the extent to which peer reviewers and editors comment on the adequacy of reporting of treatments, and correct these during the review process and develop a simple checklist for use by editors and reviewers to enhance the reporting quality of published interventions.

Key messages

The majority of published trials in our study lacked important details describing the treatment. These details would be required for healthcare professionals to undertake these treatments in practise, and for other researchers to replicate, or build on, the findings in future studies.

Although the majority of problems were not picked up by peer reviewers and editors, when they were detected only about two-thirds were fixed before publication.

The incomplete treatment descriptions we found represent a substantial waste of the research budget, trial participants’ time and an opportunity cost for clinicians and patients.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study systematically assessed the quality of descriptions of interventions in a general medical journal and reports on whether reviewers and editors detect and fix problems with the descriptions of treatments in trials.

We included only RCTs in one general medical journal and the results may not be generalisable to other journals. However, the BMJ has a lengthy review process and is generally considered to publish high-quality research, so it is likely that the situation is worse for less-influential lower-impact factor journals with fewer resources.

We used two raters who were both academic general practitioners to assess the manuscripts. However, none of the papers in this study described treatments that our raters found too specialised to evaluate, so none were excluded.

Introduction

Before dissemination, innovations in treatment require two things: (1) valid research that demonstrates the treatment's effectiveness and (2) a description of the treatment procedure sufficient to allow clinicians and others to apply the treatment in practise. Both elements require adequate reporting. The Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement on reporting randomised controlled trials (RCTs)1 was developed to help authors and editors improve the reporting of RCTs and has been widely accepted. It has been influential in improving the quality of reporting trials’ methods and results.2 However, less attention has been given to the second element: the description of the treatment being tested. For clinicians applying treatments, or researchers who wish to replicate or extend the findings, adequate treatment descriptions are vital. Treatments vary considerably in their complexity. At one end of the extreme are simple drug trials with fixed-dose drugs requiring only specification of the chemical entity, dose, frequency and duration of treatment. However, even drug treatments can require more detail if treatment requires titration, monitoring, complex delivery systems or co-treatments. Non-drug treatments require these same elements, but a physical, educational or psychological procedure—equivalent, of the chemical entity—is often far more complex. At the other extreme are multistage surgical procedures that may not be codifiable and require training in the institution that developed the procedure. Between these extremes are educational treatments, physical treatments such as physiotherapy and psychological treatments.

Two of CONSORT's 22 items are directly relevant to clinicians wishing to apply treatments: the eligibility criteria for participants and the settings and locations where the data were collected (item 3), and precise details of the treatments intended for each group and how and when they were actually administered (item 4). Yet previous work has suggested this may be insufficient to guide an adequate treatment description.3–5 Table 1 shows previous studies’ findings on inadequate reporting of specific aspects of trial interventions within a range of treatment areas; for example, an evaluation of trials complying with item 4 of the CONSORT statement.3–10 Some attempts have been made to develop detailed specifications in some treatment areas. For example, Davidson et al11 have outlined the minimal treatment detail to be described in research reports in behavioural medicine. In a similar vein, specific reporting checklists are being developed for some types of treatments such as herbal treatments12 and homoeopathy,13 which often require additional treatment details. None of these studies have systematically assessed the quality of descriptions of a series of interventions in a general medical journal using a checklist.

Table 1.

Previous studies of adequacy of descriptions of treatments in trials

| Clinical issue | Number of trials | Number (%) replicable | Methods of deciding replicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss interventions3 | 63 | 62 (98) | Compliance with item 4 of CONSORT statement* |

| Treatments of brain tumours4 | 74 | 68 (92) | Compliance with item 4 of CONSORT statement* |

| Treatments of Hodgkin's lymphoma5 | 241 | 231 (96) | Compliance with item 4 of CONSORT statement* |

| Back pain6 | 24 | 3 (13) | Sufficient information on what happens before, during and after treatment |

| Implementation of guidelines7 | 29 | <7 (16) | Assessed 6 elements: flexibility, timing, content, medium, deliverer and receiver. There is not an overall adequacy rating, but none was 100% and only 7/29 provided timing |

| Insulin initiation in type 2 diabetes8 | 14 | 3 (21) | Provision of both starting dose and titration regime |

| Surgical procedures intended9 | 158 | 138 (87) | Only required that “some” detail was provided, not sufficient for replication; 41% also provided some detail on actual surgery administered |

| Range of topics published in Evidence-Based Medicine Journal10 | 55 | 36 (65) | Two general practitioners were independently asked whether they could use the treatment with a patient if they saw them the next day |

*Item 4 is: ‘Precise details of the treatments intended for each group and how and when they were actually administered’.

Note: Each element is fully described in table 2.

The purpose of our study was (1) to document the adequacy of reporting of the different elements of descriptions of treatments in RCTs published over 1 year in a large general medical journal (the BMJ); (2) to determine the extent to which peer reviewers and editors comment on the adequacy of reporting of treatments, and correct these during the review process and (3) to develop a simple checklist for use by editors and reviewers to enhance the reporting quality of published interventions.

Methods

Setting

We conducted the research in 2007 at the BMJ, a general medical journal, where we had access to all the backmatter associated with journal submissions. The BMJ publishes research on a wide range of clinical topics.

Development, refining and piloting of the checklist

Based on the work of Davidson et al,11 the CONSORT statement1 and our own analysis of poorly reported trials abstracted in the journal Evidence-Based Medicine,10 we designed an initial checklist of the minimal details that should be included in a description of a treatment in an RCT. We piloted this on the first 10 papers and then, based on problems identified, revised the checklist. The first 10 papers were then re-evaluated with the revised checklist. The revised checklist (table 2) included the following seven aspects: a description of where the treatment was delivered (setting); who delivered the treatment (provider); who received the treatment (recipient); details of the procedure including the sequencing of the technique (procedure); a description of the physical or informational materials used (materials); the dose/duration of individual sessions of the treatment (intensity) and the scheduling, that is, the interval, frequency, duration or timing of the treatment (schedule). Raters also completed an additional subjective global item to indicate whether the treatment was sufficiently described for them to replicate it if there were no resource or training constraints (no constraints).

Table 2.

Interventions checklist

| Setting | Is it clear where the intervention was delivered? | □ Yes □ No |

| Recipient | Is it clear who is receiving the intervention? | □ Yes □ No |

| Provider | Is it clear who delivered the intervention? | □ Yes □ No |

| Procedure | Is the procedure (including the sequencing of the technique) of the intervention sufficiently clear to allow replication? | □ Yes □ No |

| Materials | Are the physical or informational materials used adequately described? | □ Yes □ No |

| Intensity | Is the dose/duration of individual sessions of the intervention clear? | □ Yes □ No |

| Schedule | Is the schedule (interval, frequency, duration or timing) of the intervention clear? | □ Yes □ No |

| Missing | Is there anything else missing from the description of the intervention? If yes, what? | □ Yes □ No |

Evaluation of published descriptions

We reviewed the given study design of all research papers published in the BMJ in a single year, 2006, and selected all RCTs for possible inclusion. Papers presenting only follow-up data or longer-term outcomes of a previously published trial were subsequently excluded as details of the intervention may previously have been reported. The full-length version of the published papers was then independently evaluated by two raters (PG and CH) for the clarity of reporting of key features of the intervention using our checklist. Our use of the term intervention refers to ‘the process of intervening on people, groups, entities or objects in an experimental study’.14 We did not evaluate the clarity of reporting of the treatment received by the control group. Both raters were blind to comments from editors and reviewers. Raters then discussed the results in person and disagreements were resolved through consensus discussion supervised by SS.

Evaluation of the review process

All back history (reviewers’ comments and editors’ notes) for the papers were obtained by SS from the BMJ's electronic manuscript tracking system. SS collated all statements given on the clarity of the reporting of the treatment for each manuscript and anonymised the comments. SS then categorised the deficiencies using our checklist. PG then assessed whether the specified deficiencies had been addressed in the final published version.

Results

We included 51 RCTs published in the BMJ in 2006. These papers described studies with a wide range of settings and treatments. Twenty-one (41%) involved the administration of a drug either alone or in addition to another therapy.

Replicability

Overall, assuming no resource or training constraints, both raters reported that 57% (29/51) of the treatments could not be replicated based on the description of the treatment as published. Studies of drug treatments were better described than non-drug treatments: 7/21 (33%) of drug treatments were considered non-replicable in comparison with 22/30 (73%) non-drug treatments.

Type of problems identified in published versions

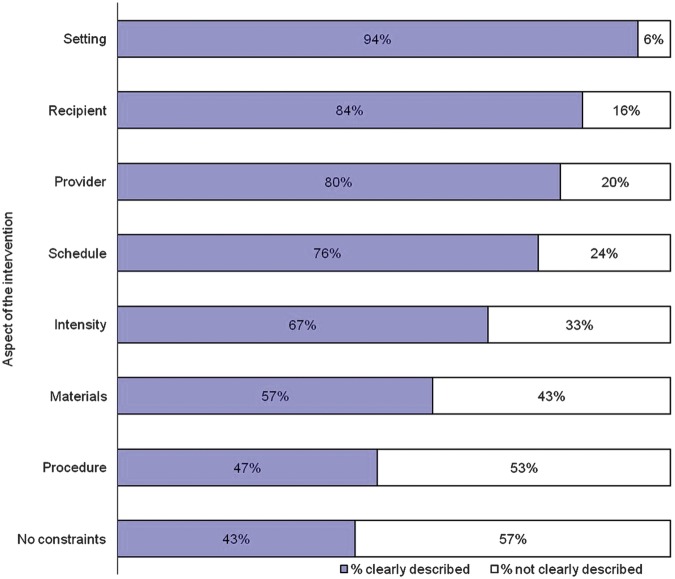

We identified 99 problems, ranging in seriousness, with the descriptions of the interventions in the published versions. For each checklist item the proportion of trials with adequately described features ranged from 47% to 94% (figure 1). The most poorly described aspects of the treatment were the actual procedures involved including the sequencing of the technique—what happened and when (53% not clear), and the physical or informational materials used, for example, training materials (43% not clear). Aspects of the treatment better described included a description of where the treatment was delivered (94% clear). For a third of the treatments described, the dose, duration or both individual sessions of the treatment were not clear and for around a quarter the schedule (interval, frequency, duration or timing) of the treatment was not clear.

Figure 1.

Elements of interventions—percentage clearly described.

Note: Each element is fully described in table 2.

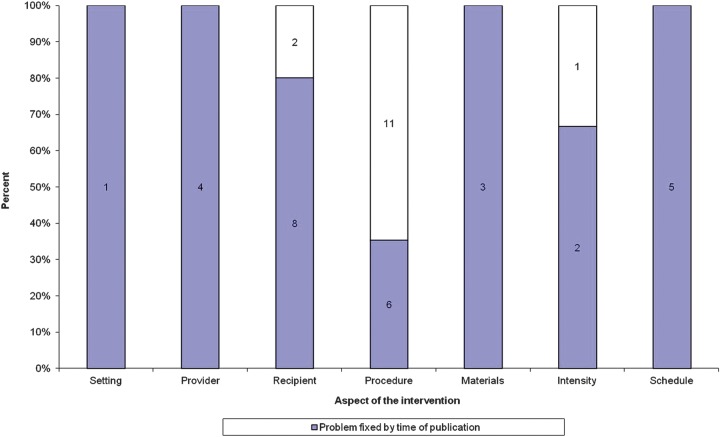

Problems identified prior to publication

During the prepublication phase of the manuscripts, the reviewers, editors and editorial advisors reported 43 problems with the descriptions of the interventions. Most comments focused on the need for clarification of the sequencing of the technique described (procedure) and the patient group under study (recipient). Thirty-three per cent (14/43) of these problems were not fully fixed by the time the paper was published (as assessed by our raters; figure 2). Where reviewers and editors identified problems with descriptions of the setting, the provider, the materials and the schedule, these were improved by the time of publication. Problems that were not corrected largely concerned the descriptions of the procedures of the treatments, that is, it was not clear what happened and when. Table 3 shows the 14 problems identified at prepublication which were not sufficiently remedied in the published version.

Figure 2.

Papers where editors’ or reviewers’ identified a problem (prepublication), and whether it remained at postpublication.

Table 3.

Examples of problems identified at prepublication and not fixed by time of publication

| Paper title | Type of problem identified at prepublication and postpublication | Nature of the problem |

|---|---|---|

| Partner notification of chlamydia infection in primary care: RCT and analysis of resource use | Procedure | Not clear exactly what was done and when |

| Didgeridoo playing as alternative treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: RCT | Intensity | Description of didgeridoo practise times not clear |

| Treatment of low back pain by acupressure and physical therapy: RCT | Procedure | Can't tell how personalised the treatment was—who had what done and when |

| Effect of enhanced psychosocial care on antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe dementia: cluster randomised trial | Procedure | Complex intervention and what was received and when for both groups is unclear |

| Effect of patient-completed agenda forms and doctors’ education about the agenda on the outcome of consultations: RCT | Recipient | Recipient of intervention unclear |

| Effect of telephone contact on further suicide attempts in patients discharged from an emergency department: randomised controlled study | Procedure | More details needed on the content and duration of the phone calls, that is, effort involved to enhance compliance |

| Effective control of dengue vectors with curtains and water container covers treated with insecticides in Mexico and Venezuela: cluster randomised trials | Procedure | Not clear why all the houses did not get nets and what they actually received |

| RCT of four commercial weight loss programmes in the UK: initial findings from the BBC “diet trials” | Procedure | Not enough details of the content of the programmes or time involved |

| An RCT of management strategies for acute infective conjunctivitis in general practise | Recipient | Recipients poorly described re conjunctivitis inclusion/exclusion criteria |

| Effectiveness of telephone counselling by a pharmacist in reducing mortality in patients receiving polypharmacy: RCT | Procedure | Not clear exactly what the pharmacists said or did. It must have been more than just a reminder phonecall |

| Telephone-administered cognitive behavioural therapy for treatment of obsessive−compulsive disorder: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial | Procedure | The actual therapy provided is only very briefly described |

| Mobilisation with movement and exercise, corticosteroid injection, or wait and see for tennis elbow: randomised trial | Procedure | Not clear what the physiotherapy actually involved |

| Effectiveness of community physiotherapy and enhanced pharmacy review for knee pain in people aged over 55 presenting to primary care: pragmatic randomised trial | Procedure | Not clear what happened and when. Content of pharmacist sessions unclear. NB: Not fully described due to space limitations. More complete description of the pharmacy intervention subsequently published22 |

| Prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in high-risk social networks of young Roma (Gypsy) men in Bulgaria: RCT | Procedure | Intervention components versus what controls received not clear—need to know the details of the intervention |

BBC, the British Broadcasting Corporation; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Discussion

The majority of published trials in our study lacked important details describing the treatment. These details would be required for healthcare professionals to undertake these treatments in practise, or for other researchers to replicate, or build on, the findings in future studies. Many problems were easily rectifiable, such as clearer reporting on the sequencing of techniques, actual doses/durations of treatments and their scheduling. Although the majority of problems were not picked up by peer reviewers and editors, when they were detected only about two-thirds were fixed before publication.

Our findings are consistent with our earlier analysis of 80 RCTs and systematic reviews published in the journal Evidence-Based Medicine where approximately a half (51%) had an ‘inadequate’ description of the treatment.10 Evidence-Based Medicine abstracts journals in a range of specialties and the similarity in results suggest that the results of this study are valid. Unlike, this study, our previous study did not quantitatively document the types of problems with the treatments described but focused on a global assessment of the replicability of the treatment and whether authors could provide the missing details when asked to do so. The current study went further than our earlier study in that it reports the frequency of poor reporting of specific aspects of trial interventions.10

Our study has several limitations. First, we included only RCTs from a single year in one general medical journal and the results may not be generalisable to other journals. However, the BMJ has a lengthy review process and is generally considered to publish high-quality research, so it is likely that the situation is worse for less-influential journals with fewer resources. The BMJ strives to publish papers to ‘help doctors make better decisions’ and is very aware of the importance of good scientific reporting of research. As such it may pay more attention to reporting issues than other journals. We found that the BMJ reported these aspects of interventions poorly and this suggests that the situation may well be worse for other journals. Second, we evaluated RCTs published in 2006 and it is possible that there have been improvements in reporting, given the wider use of the internet and web appendices in recent years. Further research would be needed to test this. Third, we used only two raters who were both academic general practitioners to assess the manuscripts some of which could have described treatments they were not familiar with. However, all RCTs published in the BMJ describe treatments that should be familiar to general practitioners, as it targets a general medical readership. None of the papers in this study described treatments that our raters found too specialised to evaluate, so none were excluded. Our raters were also experienced academics interested in improving the reporting quality of trials and as such the results may represent the best-case scenario. Finally, we did not try to separately assess planned versus actual treatments, which may sometimes differ substantially and require specific description.

We identified a few other previous studies which have examined the adequacy of treatment descriptions (table 1). Most of the studies listed in table 1 are likely to have reported overestimates of replicability as only one asked whether there was sufficient information to allow replication.10 In developing summaries for systematic reviews of back pain, Glenton and colleagues6 found sufficient details ‘about what the treatment involved’ for patients in only 3 of 24 (13%) treatments, and used 32 other sources to obtain details for the other 21 treatments. Similarly a review7 of 29 guideline implementation studies found that the majority lacked details of how the intervention was carried out, for example, only 7 (24%) supplied details of timing. Three other studies simply checked the fourth CONSORT item.3–5 Similar problems have been identified in other areas. In a recent survey15 of 93 publications with novel questionnaires in JAMA, NEJM and BMJ, four printed the questionnaire in the article, three provided online access, but authors failed to provide questionnaires for 37 of 81 (46%) studies. For some clinical domains, improving the descriptions of treatments may require additional work to standardise and document the procedures prior to clinical trials.16

Similar to many journals, BMJ authors are requested to complete the CONSORT statement when submitting a paper describing an RCT, but are not specifically asked to describe their interventions in detail. BMJ reviewers are not routinely instructed to comment on the replicability of treatments described in papers, but are instructed to check the CONSORT statement provided by the author. However, item 4 in the CONSORT statement appears insufficient to guide authors and reviewers in all the elements needed, and CONSORT have, so far, added three intervention extensions (non-pharmacological, herbal and acupuncture—http://www.consort-statement.org/extensions/), but these overlap, and a generic checklist with supplementary lists is needed.

Medical journals often send papers to reviewers who are practising clinicians in the area of interest and some may choose to comment on the reporting details of the treatment. However, limitations of peer review are well documented.17–20 In our study, peer reviewers infrequently commented on inadequate reporting of trial details. Insufficient instructions and guidance to reviewers and lack of training may compound the problem. However, even when some limitations were identified by reviewers at the prepublication stage they were not always remedied in the published version.

The incomplete treatment descriptions we found represent a substantial waste of the research budget, trial participants’ time and an opportunity cost for clinicians and patients. Though not surprising, the lower rates of adequate description of non-drug alternatives is unfortunate given the rapid growth of the pharmaceuticals budget, and the potential for non-drug therapies for alternative treatments. Funders, authors, journals and research users should all be concerned with this problem and work together to improve the situation.21 Journals that wish to publish high-quality research of use to practising healthcare professionals need to pay attention to adequate descriptions of treatments. One element of any solution should be a simple checklist, such as the generic one we have developed, or specific checklists such as the CONSORT interventions extensions (http://www.consort-statement.org/extensions/). Such checklists may be useful for authors, peer reviewers and editors to help ensure that important details of treatments are provided before the paper is published and in the public domain. However, the effectiveness of such checklists needs to be further evaluated. Ideally the full intervention description should be published with the primary article, but this often is not feasible, for example, with manual procedures or extensive training materials. Since describing such study materials could add significantly to the length of papers, we suggest that editors encourage the use of web extras and/or links to study materials on authors’ or funders’ institutional websites; these should be checked for availability at the time of publication, since researchers may retire, move or for other reasons not respond after publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the BMJ Group for SS's time on this project.

Footnotes

Contributors: SS had complete access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysed. No other staff at the BMJ were involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. SS, PG and CH designed the study; PG and CH rated the manuscripts for replicability; SS analysed the manuscripts’ backmatter; SS analysed the data; SS, PG and CH wrote the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.The University Department of Primary Health Care is part of the NIHR (National Institute for Health Research) School of Primary Care Research which provides financial support for senior staff who contributed to this paper. The opinions are those of the authors and not of the Department of Health.

Competing interests: SS is employed full-time by BMJ Group.

Ethics approval: We did not seek ethics committee approval for this study as it mainly involved the evaluation of published manuscripts in the public domain. Only SS had access to named reviewers’ and editors’ comments, who is a full-time employee of the BMJ Publishing Group and regularly reads such material as part of her job. On submitting to the BMJ, prospective authors are informed that their paper may be enrolled in a research study as part of improving the peer-review process and are given the opportunity to opt out of this.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.h85k0.

References

- 1.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, et al. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:657–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plint AC, Moher D, Morrison A, et al. Does the CONSORT checklist improve the quality of reports of randomised controlled trials? A systematic review. Med J Aust 2006;185:263–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thabane L, Chu R, Cuddy K, et al. What is the quality of reporting in weight loss intervention studies? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1554–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kober T, Trelle S, Engert A. Reporting of randomized controlled trials in Hodgkin lymphoma in biomedical journals. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:620–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai R, Chu R, Fraumeni M, et al. Quality of randomized controlled trials reporting in the primary treatment of brain tumors. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1136–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glenton C, Underland V, Kho M, et al. Summaries of findings, descriptions of treatments, and information about adverse effects would make reviews more informative. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:770–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thorsen T, Makela M. (eds) Changing professional practice. Theory and practice of clinical guidelines implementation. Danish Institute for Health Services Research and Development, 1999. http://almenpraksis.ku.dk/medarbejdere/thorkil/TT-Changing.pdf/. Accessed: 16 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lasserson DS, Glasziou PP, Perera R, Holman RR, Farmer AJ, et al. Optimal insulin regimens in type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analyses. Diabetologia; (2009). 52:1990–2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacquier I, Boutron I, Moher D, et al. The reporting of randomized clinical trials using a surgical intervention is in need of immediate improvement. A systematic review. Ann Surg 2006;244:677–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glasziou P, Meats E, Heneghan C, et al. What is missing from descriptions of treatment in trials and reviews? BMJ 2008;336:1472–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson KW, Goldstein M, Kaplan RM, et al. Evidence-based behavioral medicine: what is it and how do we achieve it? Ann Behav Med 2003;26:161–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagnier JJ, Boon H, Rochon P, et al. Reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal interventions: an elaborated CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:364–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean ME, Morag K, Coulter MK, et al. Reporting data on homeopathic treatments (RedHot): a supplement to CONSORT. Forsch Komplementarmed 2006;13:368–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. http://www.cochrane.org/sites/default/files/uploads/glossary.pdf. (Accessed 30 Jul 2012)

- 15.Schilling LM, Kozak K, Lundahl K, et al. Inaccessible novel questionnaires in published medical research: hidden methods, hidden costs. Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:1141–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pomeroy VM, Cooke E, Hamilton S, et al. Development of a schedule of current physiotherapy treatment used to improve movement control and functional use of the lower limb after stroke: a precursor to a clinical trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2005;19:350–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godlee F, Jefferson T, eds. Peer review in health sciences. London: BMJ Books, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altman DG. The scandal of poor medical research. BMJ 1994;308:283–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jefferson T, Alderson P, Wager E, et al. Effects of peer review: a systematic review. JAMA 2002;287:2784–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroter S, Black N, Evans S, et al. What errors do peer reviewers detect, and does training improve their ability to detect them? J R Soc Med 2008;101:507–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Altman DG, et al. Taking healthcare interventions from trial to practice. BMJ 2010;341:c3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phelan M, Blenkinsopp A, Foster NE, et al. Pharmacists-led medication review for knee pain in older adults: content, process and outcomes. Int J Pharmacy Pract 2008;16:347–55 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.