To the Editor: The illicit production of methamphetamine from the precursor pseudoephedrine in clandestine laboratories fuels up to 35% of the domestic supply.1 Public health, law enforcement, and medical associations support restricted access to methamphetamine precursors; manufacturers oppose restrictions.

Kentucky law limits pseudoephedrine sales in all counties to 7.2 g/person/month (as of July 2012, formerly 9 g/person/month), sufficient to allow a patient to take the maximum daily dose (240 mg/d) each day. Electronic tracking of sales is also required. Despite these restrictions, increases in the number of reported methamphetamine laboratory seizures (called laboratories) continue.2–4 We analyzed the relationship between pseudoephedrine sales and the number of laboratories reported in Kentucky.

Methods

Using county level data from 2010, we examined the association between the natural log of the number of laboratories and county pseudoephedrine sales (grams/100 residents) adjusting for the number of law enforcement officers and the percentage of high school graduates. Law enforcement regulations define laboratories as “requiring two or more chemicals or two or more pieces of equipment used in manufacturing methamphetamine.”5

Pseudoephedrine sales data were obtained from the National Precursor Log Exchange, the real-time electronic system mandated for use by pharmacies to track all sales of non–prescription pseudoephedrine medications in Kentucky. The number of full-time law enforcement officers in a county was used as a proxy for the influence of law enforcement on laboratory seizures. Data on laboratories and law enforcement officers were obtained from the Kentucky State Police. The percentage of high school graduates was used as a socioeconomic control and was obtained from the US Census.

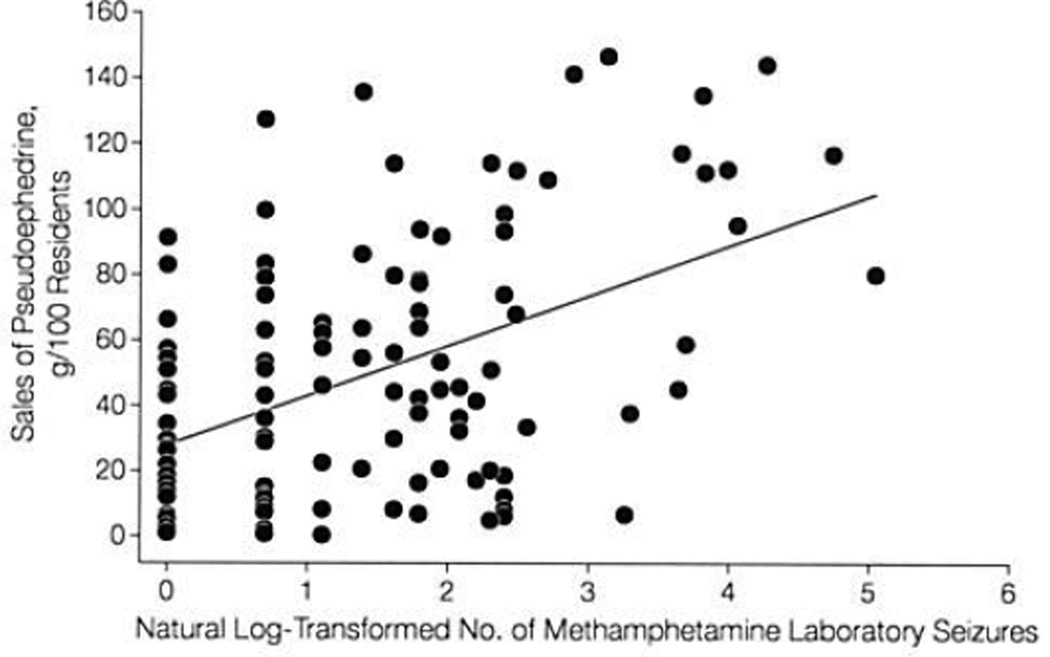

We first visualized the relationship using a scatterplot, and then calculated a log-linear regression model using Stata version 11 (StataCorp). All reported P values are 2-sided, with P < .05 considered statistically significant. The University of Kentucky institutional review board approved the study.

Results

Four Kentucky counties reported no pseudoephedrine sales, leaving 116 counties for analysis. In 2010, Kentuckians purchased a mean 24 664 g (SD, 60 313 g) of pseudoephedrine per county (per county mean, 49 [SD, 39] g/100 residents) and there were 1072 laboratories reported (per county mean, 9.28 [SD, 20.91] laboratories). There was considerable variability in pseudoephedrine sales per county from 0.26 g/100 residents (population: 13 752) to 147 g/100 residents (population: 25 581).

Variability in the number of laboratories was also evident from 0 in many counties to 154 laboratories. The natural log of the number of laboratories reported in each county and the grams of pseudoephedrine sold per 100 residents (Figure) indicates a relationship between sales and laboratories. Regression results in the Table were consistent with the visual representation in the Figure.

Figure.

Association Between Pseudoephedrine Sales and Reported Clandestine Methamphetamine Laboratory Seizures in Counties in Kentucky in 2010

The regression line representing a linear model was fit using Stata Graph 11.2.

Table.

Statistical Modeling of Methamphetamine Laboratory Seizures in 116 Kentucky Counties in 2010a

| Bivariate Model | Multivariate Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Coefficient (SE) | P Value | Coefficient (SE) | P value | |

| Pseudoephedrine sales, g/100 county residents | 49 (39) | 0.015 (0.003) | <.001 | 0.017 (0.003) | <.001 |

| No. of full-time law enforcement officers/100 county residents | 0.12 (0.11) | NA | NA | −1.300 (0.948) | .17 |

| Adult population with a high school diploma, % | 0.76 (0.08) | NA | NA | −2.519 (1.375) | .07 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Although other models were used to fit the data, including Poisson, zero-inflated Poisson, and negative binomial, the residual distribution indicated an ordinary least-squares linear regression model on the natural log of the number of laboratories in a county as the most appropriate. No pseudoephedrine sales were reported for 4 counties (Bracken, Hancock, Owsley, and Robertson) and they were excluded from the analysis.

Counties with greater pseudoephedrine sales were significantly associated with greater numbers of laboratories. In this model, a 1-g increase in pseudoephedrine sales per 100 people was associated with a 1.7% increase in laboratories. For a typical county, a 13-g per 100 resident increase in pseudoephedrine sales was associated with approximately 1 additional laboratory.

Comment

The strength of this study is that it is the first, to our knowledge, to provide empirical evidence that pseudoephedrine sales are correlated with the clandestine manufacture of methamphetamine. While the incidence of conditions for which pseudoephedrine is indicated is not known, and may vary by county, our results indicated a 565-fold variation in pseudoephedrine sales between Kentucky counties.

Our study is limited by the ecological design, possible underdetection and underreporting of laboratories, purchase of pseudoephedrine across county lines, and importation of pseudoephedrine into Kentucky. In addition, law enforcement’s use of pseudoephedrine sales data to identify questionable pseudoephedrine purchases could have affected the association between pseudoephedrine sales and laboratories. Nevertheless, this study highlights the need for research on various approaches to containing clandestine methamphetamine production, including restriction of pseudoephedrine sales to only those patients who have a true medical need for its decongestant properties.

Acknowledgments

Drs Talbert, Blumenschein, and Stromberg reported being supported by grant UL1RR033173 from the National Center for Research Resources and grant UL1TR000117 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Dr Freeman reported receiving past grant support from the National Association of State Controlled Substance Authorities for preparation of a white paper on taws regulating methamphetamine precursors.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Talbert had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Talbert, Blumenschein, Stromberg. Freeman.

Acquisition of data: Talbert, Freeman.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Talbert, Blumenschein, Burke, Stromberg, Freeman.

Drafting of the manuscript: Talbert, Blumenschein, Stromberg, Freeman.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Talbert, Blumenschein, Burke, Stromberg, Freeman.

Statistical analysis: Talbert, Burke, Stromberg.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Talbert.

Study supervision: Talbert, Stromberg.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Burke did not report any disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Additional Contributions: We thank Yevgeniya Gokun, MS (University of Kentucky Applied Statistical laboratory), for statistical consultation during the preparation of this research letter. Her analytical services as a statistician are available to all investigators free of charge.

References

- 1.Prah PM. Methamphetamine. CQ Researcher. 2005 Jul 15;:589–612. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Justice National Drug Intelligence Center. National Drug Threat Assessment. [Accessibility verified September 14, 2012];2011 http://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44849/44849p.pdf.

- 3.Nonnemaker J, Engelen M, Shive D. Are methamphetamine precursor control laws effective tools to fight the methamphetamine epidemic? Health Econ. 2011;20(5):519–531. doi: 10.1002/hec.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKetin R, Sutherland R, Bright DA, Norberg MM. A systematic review of methamphetamine precursor regulations. Addiction. 2011;106(11):1911–1924. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kentucky State Police. Methamphetamine manufacturing in Kentucky. [Accessibility verified September 14, 2012];2010 http://odcp.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/BCB964F4-8365-4E3D-BC3D-E30A50C19930/0/MethamphetamineManufacturinginKY2010Final.pdf.