Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are a class of endogenous regulatory RNA molecules 21-24 nucleotides in length that modulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level via base pairing to target sites within messenger RNAs (mRNA). Typically, the miRNA “seed sequence” (nucleotides 2-8 at the 5′ end) binds complementary seed match sites within the 3′ untranslated region of mRNAs, resulting in either translational inhibition or mRNA degradation. MicroRNAs were first discovered in Caenorhabditis elegans and were shown to be involved in the timed regulation of developmental events. Since their discovery in the 1990s, thousands of potential miRNAs have since been identified in various organisms through small RNA cloning methods and/or computational prediction, and have been shown to play functionally important roles of gene regulation in invertebrates, vertebrates, plants, fungi and viruses. Numerous functions of miRNAs identified in Drosophila melanogaster have demonstrated a great significance of these regulatory molecules. However, elucidation of miRNA roles in non-drosophilid insects presents a challenging and important task.

1. Introduction

The idea that regulatory RNA molecules may guide the expression of genes has not been limited to the past 20 years. In 1969, Britton and Davidson introduced a hypothesis that “activator” RNA molecules could work to turn on and off genes by Watson-Crick base pairing to sites located within genes; however, with the discovery of transcription factors this idea was easily abandoned. It is now known that RNAs, in particular small RNAs (sRNA), do in fact work to regulate gene expression in various organisms. The three main classes of regulatory sRNAs in animals include: microRNAs (miRNA), small interfering RNAs (siRNA), and piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNA). What define these sRNA classes are their size and their interaction with a particular Argonaute (Ago) protein. Typically in insects, 22-23 nucleotide (nt) miRNAs interact with Ago-1, 21nt siRNAs are loaded into Ago-2 and 24-31nt piRNAs are associated with the Piwi-subfamily of Ago proteins. However, the discovery of many non-canonical sRNAs and a deeper understanding of sRNA processing have blurred the boundaries between these classes.

MicroRNAs were first identified in Drosophila in an attempt to develop a cloning procedure to isolate siRNAs. This procedure lead to the identification of 16 novel “stRNAs” in Drosophila and 21 novel “stRNAs” in HeLa cells (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2001). This finding coincided with the discovery of similar sRNAs in C. elegans, and together these groups agreed to term the newly identified sRNAs, microRNAs (Lau et al., 2001; Lee & Ambros, 2001). Since the finding of lin-4 and let-7 in C. elegans, and massive miRNA cloning in Drosophila, humans and C. elegans, thousands of potential miRNAs have been detected in various organisms.

In this review, we revisit the history of miRNAs and RNA silencing, and discuss miRNA biogenesis and mode of action in insects. In addition, we summarize both the current experimental and computational tools available for the study of insect miRNAs. We conclude by highlighting recent findings concerning insect miRNAs and their targets, as well as the continuing genome-wide efforts for insect miRNA discovery and expression profiling.

2. A History of miRNAs and RNA Silencing

In 1990, plant scientists came across the first implication of RNA silencing in an attempt to overexpress a pigment synthesis enzyme, chalcone synthase, to produce a deep purple petunia; however, instead the large majority of the plants harboring the transgene unexpectedly produced completely white flowers (Napoli et al., 1990; van der Krol et al., 1990). This phenomenon was coined “co-suppression” and pioneered the way to study RNA silencing. Studies in C. elegans indicated that the expression of both sense and anti-sense RNA strands could lead to specific and effective inhibition of target genes (Fire et al., 1991; Guo and Kemphues, 1995). However, the key finding that defined the RNA interference pathway was the discovery that double stranded RNA (dsRNA) created to target exonic regions of the genome produced efficient interference. This method was substantially more effective for silencing than single-stranded sense or antisense RNA (Fire et al., 1998). The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Andrew Fire and Craig Mello in 2006 for their discovery of gene silencing by dsRNA. This action was termed RNA interference (RNAi), and is mediated by 20-25nt siRNAs derived from either naturally occurring or foreign dsRNAs. These siRNA molecules were discovered by Hamilton and Baulcombe (1999), in which they found 25nt anti-sense RNA molecules derived from an RNA template and suggested that these small RNA molecules could be the basis of post-transcriptional gene silencing. Soon after the discovery of RNAi in C. elegans, dsRNA mediated gene silencing was shown to work successfully in Drosophila, where it was used to investigate the functions of frizzled and frizzled 2 and determine their action in the wingless signaling pathway (Kennerdell & Carthew, 1998). The development of RNAi technology in insect species provided a key resource for investigating gene functions in non-drosophilid insects where genetic mutants are unavailable, and has become a fundamental tool in the functional characterization of many important genes in various insects (Bellés, 2010; Brown et al., 1999; Hughes & Kaufman, 2000).

In 1993, the first miRNA was discovered in C. elegans by the identification of two transcripts arising from the lin-4 locus: the 22nt lin-4s and the 61nt lin-4L (Lee et al., 1993; Wightman et al., 1993). These groups showed that lin-14 translation is regulated by lin-4 through its 3′ untranslated region (UTR) by some anti-sense mechanism. It was not until 7 years later that the next miRNA was discovered, in which the 21nt let-7 in C. elegans was shown to temporally regulate lin-41 by binding target sites within its 3′UTR (Reinhart et al., 2000). The discovery of lin-4 and let-7 added a new dimension to our understanding of complex gene regulatory networks, and since their discovery thousands of putative miRNAs have been identified in various organisms.

3. MicroRNA Biogenesis

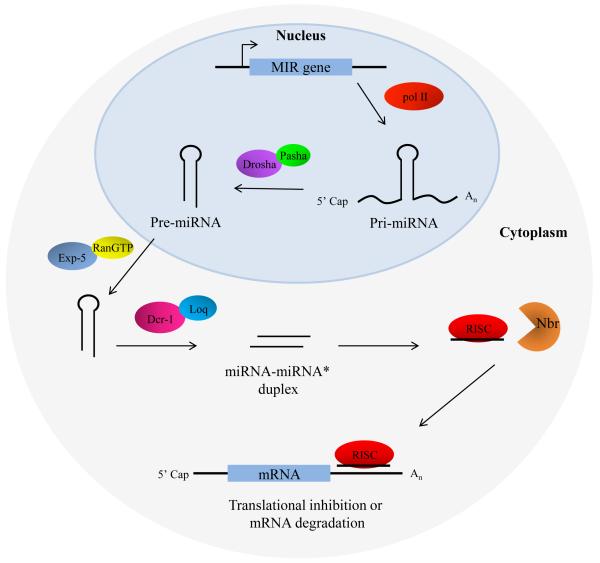

In insects, miRNA biogenesis consists of several processing steps from transcription of the miRNA loci to loading and sorting into the RNA induced silencing complex, or RISC (Figure 1). Mature miRNAs can arise from monocistronic, bicistronic or polycistronic miRNA transcripts. These transcripts fold into hair-loop structures known as the primary miRNA (pri-miRNA), which is processed in the nucleus by an RNase III enzyme liberating the precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA). This pre-miRNA is exported to the cytoplasm where it is processed by another RNaseIII enzyme to form the miRNA-miRNA* duplex. MicroRNA biogenesis has been heavily studied in model organisms, including Drosophila; however, novel findings concerning non-canonical miRNA biogenesis and processing in different organisms continue to be uncovered (Borchert et al., 2006; Cheloufi et al., 2010).

Fig. 1.

A model for microRNA biogenesis. MicroRNA loci are typically transcribed by RNA polymerase II (pol II). The transcripts fold into a hair-loop structure known as the pri-miRNA, which is processed in the nucleus by the Drosha/Pasha microprocessor complex to form a ~70nt pre-miRNA. The pre-miRNA is exported to the cytoplasm in a RanGTP/Exp-5 dependent manner for further processing. Within the cytoplasm the pre-miRNA is processed by Dicer-1 (Dcr-1) and Loquacious (Loq) to form the miRNA-miRNA* duplex. The duplex strands are then sorted and miRNA strand is loaded into the RISC complex that typically includes Argonaut 1 (Ago-1). In some instances, the miRNA within RISC undergoes further trimming by Nibbler (Nbr). The miRNA “seed sequence” (nucleotides 2-8 at the 5′ end) binds complementary seed match sites within the 3′ untranslated region of mRNAs, resulting in either translational inhibition or mRNA degradation.

3.1. Transcription of miRNA Loci

It was initially believed that RNA polymerase III (pol III) mediated the transcription of most miRNA loci because it is known to transcribe most of the shorter non-coding RNAs such as tRNAs and U6 snRNAs. However, miRNA gene structure and direct experimental evidence suggests that miRNA loci function as class-II genes, in which pol II is the primary RNA polymerase mediating miRNA loci transcription in animals. While the majority of miRNAs are derived from intergenic regions and are found as independent transcription units, some miRNA genes are located in intronic regions and have been shown to be transcribed in parallel with their host transcript by pol II (Rodriguez et al., 2004). Furthermore, several miRNA genes exist as clusters of 2-7 genes and are transcribed as one bicistronic or polycistronic pri-miRNA transcript (Lee et al., 2002). Many pri-miRNA transcripts contain traditional 5′ 7-methyl guanosine caps and 3′ polyadenylation, and are sensitive to α-amanitin, a pol II inhibitor, indicating that many miRNA loci indeed act as class-II genes (Lee et al., 2004a). It is also suggested that pol III may mediate the expression of miRNAs located within repetitive sequences. In humans, the chromosome 19 miRNA cluster was shown to be transcribed by pol III and that Alu repeat sequences upstream of this cluster participate in this transcriptional process (Borchert et al., 2006). However, an understanding of the transcription of miRNA loci located in repetitive sequences of the genome by pol III is not well understood.

3.2. Pri-miRNA processing by the microprocessor complex

Pri-miRNA transcripts can be several kilobases long and contain one or more hair-loop structures, which are processed in the nucleus into a 70nt pre-miRNA by the microprocessor complex. The ~500kDa microprocessor complex contains an RNase III enzyme, Drosha, and its double stranded RNA (dsRNA) binding partner, Pasha (DGCR8 in mammals and C.elegans) (Denli et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2004; Han et al., 2004; Landthaler et al., 2004; Lee et al. 2003). Drosha and its dsRNA binding partner protein Pasha/DGCR8 recognize and cleave the pri-miRNA, which typically consists of a ~30 bp stem structure, with a terminal loop and flanking segments. Pasha/DGCR8 recognizes the substrate pri-miRNA, anchors to the flanking single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and dsRNA stem junction, and locates the position 11bp into the stem where the processing center of Drosha is placed to cleave the pri-miRNA (Han et al., 2006).

A non-canonical class of miRNAs termed miRtrons can bypass Drosha-Pasha/DGCR8 processing (Ruby et al., 2007a). This class of miRNAs has been heavily studied in Drosophila. MiRtons are located within the introns of protein coding genes and are transcribed in parallel with their host transcript by pol II. The ends of the miRtron hairpins coincide with the 5′ and 3′ splice sites of introns located within protein coding genes. The miRtron is released by the splicing machinery and the intron lariat debranching enzyme to yield pre-miRNA-like hairpin structures, and merges with the canonical miRNA pathway during pre-miRNA export to the cytoplasm (Okamura et al., 2007). In some instances miRtrons, such as the Drosophila miRtron-like miR-1017, contain a 3′ terminal tail that is trimmed by an RNA exosome before export, revealing an unexpected role for the exosome in the biogenesis of another class of non-canonical miRNAs (Flynt et al., 2010).

After Drosha-Pasha processing of the pri-miRNA into a 70 nt pre-miRNA, the pre-miRNA is exported into the cytoplasm for further processing. Drosha cleavage of the pri-miRNA yields a pre-miRNA product containing a 2 nt 3′ overhang, which is crucial for pre-miRNA nuclear export. A Ran guanosine triphosphate (RanGTP)-dependent dsRNA-binding receptor, Exportin-5 (Exp-5), mediates the nuclear export of pre-miRNAs by recognizing the 2nt 3′ overhang of the pre-miRNA in the nucleus (Bohnsack et al., 2004; Lund et al., 2004; Yi et al., 2003). The Exp-5/pre-miRNA complex migrates through the nuclear pore complexes into the cytoplasm, where the release of the pre-miRNA occurs in response to the hydrolysis of RanGTP to RanGDP. Exportin-5 not only serves as the nuclear export factor for pre-miRNAs, but also protects pre-miRNAs from digestion by nucleases (Lund et al., 2004; Yi et al., 2003).

3.3. Pre-miRNA processing by Dicer

In the cytoplasm, the terminal loop structure of the pre-miRNA is cleaved by another RNase III enzyme, Dicer-1 (Dcr-1), relieving a ~22 nt miRNA-miRNA* duplex (Hutvánger et al., 2001; Ketting et al., 2001: Knight and Bass, 2001). The miRNA and miRNA* are the two strands of the dsRNA product of dicer processing of the stem loop precursor miRNA. Dicer was first identified in Drosophila as a key enzyme in the RNAi pathway (Bernstein et al., 2001). The Drosophila genome encodes two Dicer enzymes, Dcr-1 and Dcr-2, each with a specialized function in the miRNA and siRNA pathways respectively. Mutant dcr-1 flies are unable to processes pre-miRNAs, while dcr-2 mutant flies are defective for processing siRNA precursors, thus Dcr-1 is critical for mature miRNA production whereas Dcr-2 is required for siRNA generation from long dsRNAs. (Lee et al., 2004b). Like Drosha, Dcr-1 also requires a dsRNA binding domain protein partner in order to exert its action on pre-miRNAs. The Drosophila Dcr-1 interacts with Loquacious (Loqs) (also known as R3D1-L) to form a pre-miRNA processing complex (Jiang et al., 2005; Saito et al., 2005). Depletion of Loqs by RNAi results in pre-miRNA accumulation and a reduction of mature miRNA, similar effects as caused by Dcr-1 depletion.

Drosophila Dcr-2 is highly specific to long dsRNAs via an inorganic phosphate and its dsRNA binding partner, R2D2 (Cenik et al., 2011). However, Drosophila Dcr-1 determines the authenticity of a pre-miRNA by recognizing the pre-miRNA loop structure through its N-terminal helicase domain and proceeds to measure the loop size. In addition, the Dcr-1 PAZ domain recognizes the two nt 3′ overhang produced by Drosha/Pasha and measures the distance from the overhang to the single stranded terminal loop (Tsutsumi et al., 2011). In this way Dcr-1 can distinguish true pre-miRNAs from similar structures.

3.4. MicroRNA strand selection and Argonaute loading

Upon Dcr-1 cleavage of the pre-miRNA to form the mature miRNA-miRNA* duplex, one strand is loaded into the RISC. The core component of the RISC is the Argonaute family of sRNA guided RNA-binding proteins. The Drosophila genome encodes five distinct Ago proteins, which are categorized into two sub-clades: Ago and Piwi. The Ago sub-clade comprises Ago-1 and Ago-2, which were originally believed to bind miRNAs and siRNAs, respectively (Hammond et al., 2001; Okamura et al., 2004). It was thought that the mature miRNA guide strand was loaded into Ago-1 while the miRNA* passenger strand was degraded; however, studies suggest that certain characteristics of the miRNA-miRNA* duplex influence strand selection and partitioning between Ago-1 and Ago-2 (Förstemann et al., 2007; Okamura et al., 2009; Tomari et al., 2007). Sorting of miRNAs into Ago1-RISC is influenced by a 5′ uracil and thermodynamic instability caused by central bulges at nucleotide 7-11, while sorting into Ago2-RISC is sensitive to thermodynamic stability, including base pairing at nucleotides 9-10.

For the majority of insect miRNAs, the miRNA-Ago complex is ready to perform its action on target sequences; however, some miRNAs require additional processing after Ago loading. More than one quarter of miRNAs present in Drosophila S2 cells are trimmed after Ago loading (Han et al., 2011). This trimming is performed by a Mg2+-dependent 3′-to-5′ exoribonuclease termed Nibbler, a member of the DEDD superfamily of exonucleases which share a common catalytic mechanism characterized by the involvement of two metal ions. Nibbler accounts for the 3′ end variation of the three miR-34 isofoms, which contain the same 5′ terminus but differ at their 3′ end (Han et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011). RNAi depletion of Nibbler results in developmental defects and accumulation of the large miR-34 isoforms. After Nibbler processing, the miRNA isoforms within the Ago protein are now prepared to perform its action on target mRNAs.

4. MicroRNA Mode of Action

Typically, the miRNA-Ago complexes silence gene expression post-transcriptionally through translational inhibition or mRNA degradation. This typically occurs through imperfect base-pairing to target “seed match” sites within the 3′ UTR of mRNAs (Lee et al., 1993; Wightman et al., 1993). Some functional binding sites of miRNAs have also been identified in the 5′ UTR (Lytle et al., 2007; Orum et al., 2008) and ORF (Duursma et al., 2008; Forman et al., 2008; Shen et al., 2008; Tay et al., 2008) of mRNAs as well.

4.1. Translational Inhibition

MicroRNAs have been shown to impede translation in a 7-methyl guanosine (m7G) cap dependent manner and work to inhibit cap recognition by displacing eIF4E, which binds the m7G cap directly and is essential for the initiation of translation (Kiriakidou et al., 2007). Human Ago-2 was revealed to contain a cap binding-like motif within its Mid domain. This motif is present in all four human and mammalian Agos, in Agos from chordates, in Drosophila AGO1, and in C. elegans ALG-1 and ALG-2. Kiriakidou et al (2007) proposed that human Ago-2 may repress translation initiation by binding to the m7G cap of mRNA targets and likely prevents the recruitment of eIF4E.

In Drosophila, the RNA helicase Armitage was shown to be important for translational silencing of oskar mRNA, a gene essential for posterior patterning and germ cell formation (Cook et al., 2004). In addition, human RISC presented association with MOV10 (the ortholog of Drosophila Armitage), the translation inhibitory protein eIF6 and proteins of the 60S ribosome subunit (Chendrimada et al., 2007). The role of Armitage/MOV10 and eIF6 in translational repression is not clear; however, it is speculated that Armitage/MOV10 may play a role in functional RISC assembly. The mature RISC may then recruit eIF6 to the 60S ribosomal subunit, inhibiting ribosome formation and thereby influencing translational repression.

In some cases, the poly(A) tail of mRNAs may play important roles in miRNA mediated repression. Using the D. melanogaster embryo in vitro system, it was revealed that the Poly(A) Binding Protein (PABP) and the poly(A) tail recruits RISC to its target, in which RISC displaces PABP and recruits deadenylation machinery (Moretti et al., 2012). The displacement of PABP and the recruitment of deadenylation machinery may inhibit the circularization of the closed-loop structure necessary for translation.

Evidence in human cell lines has revealed that miRNAs may also work to inhibit translation during elongation but before the completion of a full length polypeptide chain due to “ribosome drop-off” (Petersen et al., 2006). Using partially complementary siRNAs to investigate the mechanism by which miRNAs mediate translational repression, Petersen et al (2006) showed that translational repression was still able to occur in CrPV and HCV IRES-driven translation, a translational model that bypasses all steps required during normal translational initiation. Repressed mRNAs were also shown to be associated with polyribosomes that are engaged in translation elongation and ribosomes on repressed mRNAs dissociate more rapidly than those on control mRNAs.

4.2. Degradation of mRNA

As found with the majority of plant miRNAs, full complementarity of an animal miRNA to its target may lead to cleavage by Ago. However, in most circumstances mRNA degradation in animals may not occur by Ago cleavage, but instead through mRNA decay mechanisms. Components of the P-body, cytoplasmic domains where proteins required for mRNA degradation accumulate, including GW182 and the DCP1:DCP2 decapping complex, have been shown to be important in the miRNA pathway in Drosophila (Rehwinkel et al., 2005). GW182 from the P-body may interact with Ago-1 to recruit deadenylases and decapping enzymes (Behm-Ansmant et al., 2006).

Steady state ribosome profiling experiments, in which RNA actively being translated by ribosomes is isolated and sequenced, have suggested that miRNAs in mammalian cells predominantly act through mRNA decay, with a moderate contribution from translational repression (Guo et al., 2010). Ribosome profiling experiments with temporal resolution and poly(A) tail analysis in Zebrafish indicate that miR-430 works to induce translational repression by reducing the rate of translation initiation, followed by mRNA decay through deadenylation (Bazzini et al., 2012). Likewise, studies of miRNA-mediated gene silencing in Drosophila S2 cells using a luciferase-based reporter system have also recently indicated that miRNA action is first mediated through translational repression and then mRNA deadenylation and decay (Djuranovic et al., 2012).

How a particular miRNA-Ago complex elicits its action may be strongly influenced by specific features of the miRNA and the miRNA-binding site. It is possible that miRNAs may actually silence gene expression by a common unknown mechanism and the multiple modes of action described above might represent secondary effects of miRNA mediated gene silencing. Further insights into miRNA modes of action and target site location are essential for a complete understanding of miRNA function and target prediction.

5. MicroRNA Functional Analysis Tools

In Drosophila classic genetic mutants can be produced to study the function of miRNAs. The first Drosophila miRNA mutant reported was mir-14 (Xu et al., 2003), and since that time many miRNA loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutants have been used to investigate the roles of miRNAs in flies. However, in the majority of insect species, technology for the efficient production of mutants and mutant libraries are not widely available.

5.1. MicroRNA loss-of-function approaches

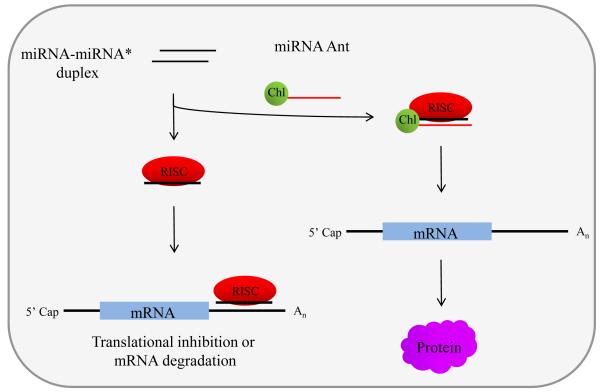

A knockdown effect of a miRNA can be achieved using a cholesterol conjugated antisense RNA oligonucleotide, known as an antagomir (Horwich and Zamore, 2008; Krützfeldt et al., 2005). These antisense oligonucleotides work as competitive inhibitors of miRNAs by annealing to the mature miRNA after incorporation into the RISC and may result in miRNA degradation (Figure 2). A potent miRNA sequence specific antagomir is designed to harbor the following modifications: (1) complete 2′ O-methylation and (2) partial phosphorothioate backbone for stability, and (3) a cholesterol group at the 3′ end for the enhancement of antagomir delivery throughout the organism. Antagomirs are simple powerful tools to silence specific miRNAs; however, they provide narrow applicability in assessing miRNA function due to the lack of spatial and temporal specificity. In addition, a major challenge to the use of antagormir technology is their stability and delivery both in vitro and in vivo, in which cells maybe resistant to the uptake of oligonucleotides and may require extensive optimization of appropriate chemical modifications on the antagomir (Horwich and Zamore, 2008; Stenvang et al., 2012).

Fig. 2.

MicroRNA inactivation via a cholesterol (chl) conjugated oligoribonucleotide (Antagomir, Ant). Typically, the miRNA-miRNA* duplex is incorporated into RISC leading to translational inhibition or mRNA degradation. However, the sequence-specific Ants competitively bind mature miRNAs in RISC thereby preventing miRNAs from binding their target mRNAs. As a result, a given mRNA, destined for translational inhibition or degradation, generates a protein in an incorrect spatiotemporal manner creating undesirable effect in an organism.

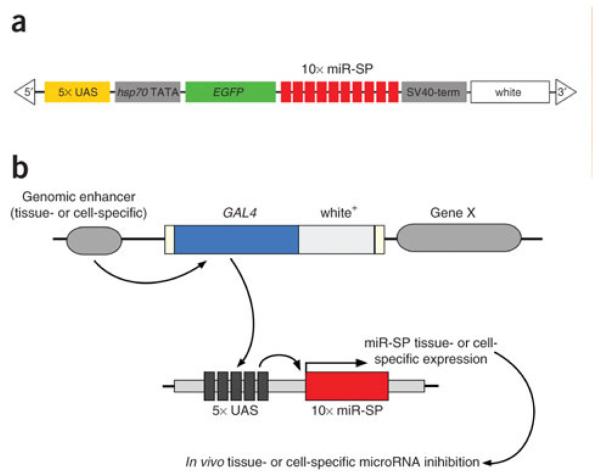

In order to achieve a spaciotemporal inhibition of a miRNA or an entire miRNA “seed” family, a miRNA sponge (miR-SP) can be employed. The miR-SP contains tandemly arrayed sequences complementary to a miRNA with a mismatched bulge at positions 9-12 (Ebert et al., 2007; Loya et al., 2009). By designing miRNA binding sites with a bulge at the position normally cleaved by Argonaute these sites are able interact with or “soak up” their target miRNAs. The first Drosophila miR-SP was produced by developing a cassette containing 10 bulged miRNA binding sites downstream of EGFP in a UAS-containing P-element vector (Figure 3) (Loya et al., 2009). Using an enhancer trap method the Gal4-UAS system was used to drive the expression of the miR-SP transgene. The miR-SP transgenic method provides a powerful tool to assess the temporal and spatial functions of miRNAs in vivo; however, the miR-SP method maybe limited in selectivity for a single member of a miRNA family and the development and testing of miR-SP transgenic lines can be time consuming (Elbert et al., 2007; Horwich and Zamore, 2008).

Fig. 3.

The microRNA sponge (miR-SP) transgenic loss-of-function approach utilizing the GAL4-UAS system in Drosophila. (a) miR-SP design. Ten miRNA binding sites (red) containing mismatches at positions 9-12 were inserted downstream of EGFP (green) in a UAS-containing P-element vector. (b) The resulting transgenic Drosophila line can be crossed to specific Gal4 lines to achieve hybrid transgenic lines with spatiotemporal inhibition of a miRNA. (From Loya et al., 2009, with permission).

Another type of transgenic miRNA inhibitor, shown to be effective in mammalian cells, is the Tough Decoy (TuD) RNA (Gagan et al., 2011; Haraguchi et al., 2009; Hikichi et al., 2011; Lu et al, 2011). TuD RNAs contain miRNA binding sites in single-stranded regions of short stem loops, presenting the sites for binding of miRNA associated RISC. Recently, a novel synthetic miRNA inhibitor, termed synthetic-TuD (s-TuD), which contains a similar structure to transgenic TuD RNAs, has been developed. Through a simple transfection of s-TuDs in mammalian cells, sufficient miRNA inhibitory effects were shown to persist for 7 days in vivo (Haraguchi et al., 2012). These s-TuD RNAs may also provide a simple, more efficient tool for miRNA inhibition in insect cells; however, TuD and sTuD RNAs have yet to be explored in insect cells and in vivo studies.

5.2. MicroRNA gain-of-function approaches

It appears that in many cases the consequence of loss of individual miRNAs is likely to have subtle or no phenotypic effects. In these cases, gain-of-function experiments can be utilized in order to unravel the roles of miRNAs. In insects, a miRNA gain-of-function effect can be achieved using treatments with miRNA mimic RNAs (Hussain et al., 2011), or expression vectors or a Gal4-UAS system for the overexpression of pri-miRNA transcripts (Hartl et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2012; Vallejo et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2012). MicroRNA expression can be mimicked by transfecting cells or in theory by injecting insects with mimic RNAs that are identical in sequence to miRNAs. These so called “miRNA mimics” are chemically synthesized dsRNAs which mimic mature endogenous miRNAs. To regulate temporal and spatial over-expression of a gene, such as a miRNA gene, in vivo the Gal4-UAS system can be used (Figure 3). Using a Gal4 driver line driven by a native promoter or an enhancer trap system to induce the expression of a UAS-miRNA responder line, the over-expression or a gain-of-function effect of a particular miRNA can be assessed in a spaciotemporal specific manner.

5.3. Insights to microRNA functional analysis tools

In Drosophila, the use of miRNA mutants has been influential in understanding miRNA function; however, this approach is currently not applicable for non-drosophilid insects. For these insects, the miRNA antagomir technology represents a powerful choice for miRNA inhibition and has been used in non-drosophild insect species including: Aedes agypti (Bryant et al., 2010; Hussian et al., 2011) and Helicoverpa zea fat body cells (Hussain and Asgari, 2009). In addition, the use of miRNA mimics can serve as a gain-of-function method in vitro and in vivo. Insect species that have an established Gal4-UAS system or similar, spaciotemporal transgenic methods can be employed using the miR-SP technology for a loss-of-function effect or miRNA overexpression gain of function effect. The Gal4-UAS system has been successfully established in D. melanogaster (Brand & Perrimon, 1993), silkworm (Imamura et al., 2003), mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae (Kokoza & Raikhel, 2011; Lynd & Lycett, 2012) and Tribolium (Schinko et al., 2010). With the development and continuous improvement of transgenic technology in many important non-drosophilid insect species, the production of miR-SP transgenic or overexpression lines can be a valuable tool to assess the temporal and spatial functions of miRNAs.

6. MicroRNA Target Predictions

An important step in understanding miRNA function is determining authentic miRNA targets. The traditional canonical miRNA binding site consists of 7-8nt seed match sites with contiguous base pairing throughout the miRNA-mRNA; however, many non-canonical binding sites have been shown to effectively repress gene expression. This has proved difficult in producing an effective algorithm to computationally predict all authentic miRNA binding sites without the tedious task of sorting through false positive results. Algorithms that are too stringent can result in false negatives; however, low stringency in computational prediction tools can produce an overwhelming number of false positives. In such cases, experimental target identification may be more efficient and/or act as a powerful complement to computational prediction programs, along with target validation. In addition, readily available bioinformatic prediction tools are not adapted for use for the majority of non-drosophild insects genomes, in part, because some non-drosophilid insect genomes remain incomplete and/or are not well annotated. With the continuously increasing availability of well-annotated genome sequences and 3′ UTR databases, and adaptation of bioinformatics tools to non-drosophilid genomes, miRNA target identification in non-drosophilid insects will improve.

6.1. Computational target prediction tools

Various computational target prediction tools are available for the identification of miRNA targets. Table 1 summarizes presently available miRNA computational prediction tools an containing information regarding miRNA target prediction program, algorithm used and the species the program has been adapted for. The PicTar algorithm is available for computational miRNA target prediction in vertebrates, worms and Drosophila species (Grün et al., 2005; Krek et al., 2005; Lall et al., 2006). PicTar assess 3′ UTR alignments to the miRNA seed region: defined as a stretch of seven bases starting at the first or second position from the 5′ end of the miRNA. Each 3′ UTR containing a candidate miRNA binding site must pass a thermodynamic stability filter and is then subjected to a hidden Markov model to compute a score reflecting the predicted sites likelihood of that site to be a true miRNA binding site.

Table 1. Presently available computational miRNA target prediction tools.

Contains information regarding presently available miRNA target prediction programs, including program name, algorithm used and the species the program has been adapted for.

| Program | Algorithm | Species | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| PicTar | PicTar | Vertebrates, fly, worms | Grün et al., 2005; Krek et al., 2005; Lall et al., 2006 |

| EBI:MicroCosmTargets | miRanda | Vertebrates, worms, D. melanogaster, D.pseudoobsura, Aedes aegypti, Anopheles gambiae |

Enright et al., 2003; Griffith-Jones et al.,2006;2008 |

| MicroRNA.org | miRanda | Human, mouse, rat, fly, C.elegans |

Betel et al., 2007; Enright et al., 2003 |

| TargetScan | TargetScanS | Mammals, worms, fly, zebrafish |

Kheradpour et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2005; Ruby et al., 2007a; 2007b |

| PITA | PITA | Human, mouse, fly, worms | Kertesz et al, 2007 |

| MicroInspector | MicroInspector | Vertebrates, worms, arthropods, plants, viruses |

Rusinov et al., 2005 |

| RNAhybrid | RNAhybrid | Any |

Krüger et al., 2006; Rehmsmeier et al., 2004 |

| RNA22 | Vienna RNA Package | Any | Hofacker et al., 1996 |

| DIANA-microT Analyzer | DIANA - microT v3.0 | Mammals |

Maragkakis et al, 2009a; 2009b |

| miRDB | MirTarget2 | Human, mouse, rat, dog and chicken |

Wang & El Naqa, 2008; Wang, 2008 |

The miRanda algorithm is a three phase miRNA target prediction method (Enright et al., 2003). This algorithm is used at the microRNA.org (Betel et al., 2008) web tool for human, mouse, rat, D. melanogaster and C. elegans, and the EBI: MicroCosmTargets (Griffiths-Jones et al., 2006; 2008) web tool for various organisms, including the insect species: D. melanogaster, D. pseudoobscura, Ae. aegypti and An. gambiae. The miRanda algorithm first assess complementarity of the miRNA and a 3′ UTR (Phase 1), performs a free energy calculation to estimate the energetics their interaction (Phase 2) and uses an evolutionary conservation filter (Phase 3).

The TargetScanS algorithm is another miRNA target prediction program available for various mammalian species, zebrafish, C. elegans and D. melanogaster (Kheradpour et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2005; Ruby et al., 2007a; 2007b). A TargetScanS perl script is also available for download to search for miRNA binding sites in a custom set of data, which may be beneficial for studies of miRNA target identification in non-drosophilid insects. For Drosophila, TargetScanFly searches for both conserved and non-conserved sites through seed sequence complementarity between the miRNA and its 3′ UTR.

MicroInspector is a web tool available to analyze a user defined RNA sequence for miRNA binding sites with a high degree of complementarity (Rusinov et al., 2005). While most programs begin with a particular miRNA of interest to identify hundreds of possible targets, MicroInspector instead begings with a single mRNA sequence and finds miRNAs that putatively target the given sequence. This program is available for use in many organisms, including insect species such as Drosophila, Apis mellifera, An. gambiae, Bombyx mori, Locusta migratoria, and T. castaneum. Two free energy of folding algorithms, RNAhybrid (Krüger et al., 2006; Rehmsmeier et al., 2004) and RNA22 (Hofacker et al., 1996), are also available for the analysis for any single user specified mRNA and miRNA. These tools find the minimum free energy of hybridization between the two RNAs. Another program known as miRecords, available for D. melanogaster and other animal species, integrates various target prediction tools for both experimentally identified or predicted miRNA targets (Xiao et al., 2009).

Assessing overlapping putative miRNA targets between various computational prediction methods enables more rapid progress in narrowing down putative targets for further experimental assays and has been a successful method in identifying functional miRNA binding sites (Hyun et al., 2009). However, the majority of readily available computational miRNA target prediction tools are not adapted to non-drosophilid insect genomes and “in-house” target prediction programs may be beneficial for identifying miRNA targets in these organisms. In addition, a BLAST search for transcripts containing miRNA “seed” match sites combined with individual 3′ UTR assessment using RNAhyrid and 22RNA algorithms have also proven useful to overcome this obstacle (Hussain et al., 2011).

6.2. Experimental target identification tools

In addition to miRNA target prediction in silico, experimental miRNA target identification tools have also been developed and may serve as a complement to computational prediction programs. CLIP-seq technology is a prevalent method to define Ago interactions and experimentally identify Ago bound miRNAs and targeted mRNA sites. In Ago HITS-CLIP (High Throughput Sequencing of RNAs isolated by Crosslinking Immunoprecipitation) RNA binding proteins (RBP) are UV cross-linked to bound RNA, and Ago bound mRNA and miRNA are co-precipitated with an Ago antibody followed by RNA-seq (Chi et al., 2009). Ago HITS-CLIP experiments can be performed in vivo or in vitro, allowing target identification of a particular temporal or spatial specific miRNA. Ago PAR-CLIP (Photoactivatable-Ribonucleoside-Enhanced Crosslinking and Immunoprecipitation) is another in vivo CLIP-seq method used to identify Ago interaction sites (Hafner et al., 2010). Photoactivatable nucleoside analogs are incorporated into cellular RNA of cultured cells, enhancing cross-linking of RBPs to bound RNA under exposure UV light of 365nm, and like HITS-CLIP cross-linked Ago-RNA complexes are immunoprecipitated and bound RNA is subjected to RNA-seq.

Transcript analysis on samples overexpressing or knocking down a miRNA can be used to identify miRNA targets; however, these methods do not account for the detection of miRNAs that cause translational inhibition. Proteomic analysis can also be used to find miRNA targets. Stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture or SILAC is a high-throughput method for quantitative proteomics, and can be used to assess the effect of a miRNA on the proteome by overexpressing or knocking down a miRNA of interest (Baek et al., 2008; Selbach et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2010). However, direct or indirect effects on a transcript or protein cannot be distinguished in these experiments.

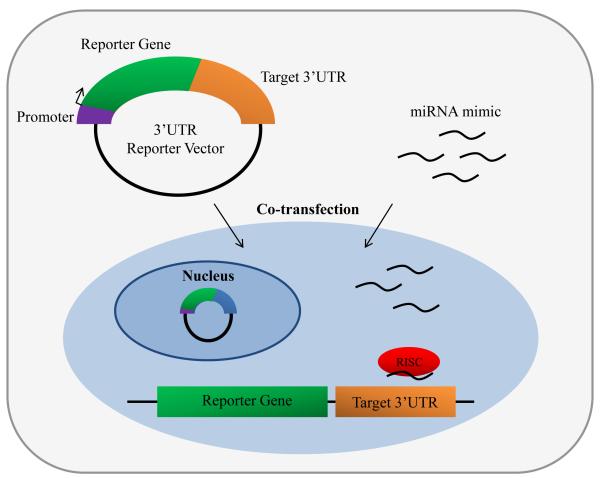

6.3. Target validation

Once potential miRNA targets have been identified in silico or experimentally, 3′ UTRs of mRNAs of interest that are putatively targeted by a miRNA should be validated before continuing downstream experiments. One of the most reliable quantitative assays for the validation of a miRNA binding site is the application of a reporter gene, such as luciferase or GFP. A target site or 3′ UTR of a putative miRNA target is sub-cloned downstream of a reporter gene and co-transfected along with the miRNA mimic of interest into insect cells (Figure 4). Inhibition of the reporter gene by the miRNA mimic indicates regulation of the 3′ UTR by the specific miRNA. This 3′ UTR reporter assay has been used as a validation method for many insect miRNAs and their confirmed targets, including miR-8 and USH (Hyun et al, 2009), miR-2940 and metalloprotease (Hussain et al., 2011), and let-7 and Imp (Toledano et al, 2012) among many others.

Fig. 4.

An in vitro cell transfection assay for testing putative miRNA target genes. A 3′ UTR reporter vector harboring a reporter gene and the 3′ UTR of the putative miRNA target gene is co-transfected into an insect cell line with a miRNA mimic of interest. Successful binding of the miRNA mimic to the putative miRNA target will result in the suppression of reporter gene expression.

7. Functional analysis of insect microRNAs and their targets in Drosophila

MicroRNAs were first identified in an insect species through studies in Drosophila (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2001). Since the discovery of miRNAs in this model organism, Drosophila has become one of the most heavily studied organism in providing a foundation for an understanding of miRNA biogenesis and function in animals. Drosophila miRNAs have revealed distinct roles in many important developmental events in not only insect processes, but also various conserved mechanisms in animals. Table 2 summarizes currently known functions and validated targets of insect miRNAs.

Table 2. Currently known functions and validated targets of insect miRNAs.

Contains information on currently known insect miRNA functions and validated targets, including miRNA and species, function and validated targets.

| miRNA | Function | Target | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|

| dme-bantam | Optic lobe development | Omb | Li & Padgett, 2012 |

| dme-let-7 | Neuromusculature remodeling | Sokol et al., 2008 | |

| Stem cell behavior | Imp | Toledano et al., 2012 | |

| dme-miR-iab4 | Wing development | Ubx | Ronshaugen et al., 2005 |

| dme-miR-1 | Muscle cell differentiation | Delta | Kwon et al., 2005 |

| dme-miR-6 | Apoptosis | rpr, hid, grim, skl | Ge et al., 2012 |

| dme-miR-7 | Germline differentiation | Bam | Pek et al., 2009 |

| EGF receptor signaling | Yan | Li & Carthew, 2005 | |

| Germline stem cell division | Yu et al., 2009 | ||

| dme-miR-8 | Neurodegeneration | Atrophin | Karres et al., 2007 |

| Wnt/Wg Signaling | TCF, CG32767 | Kennell et al., 2008 | |

| Insulin signaling | Ush | Hyun et al., 2009 | |

| Overgrowth and tumor metastasis | Serrate | Vallejo et al., 2011 | |

| Pigmentation; eclosion | Kennell et al., 2012 | ||

| Innate immunity | Choi & Hyun, 2012 | ||

| dme-miR-9 | Wing development | dLMO | Biryukova et al., 2009 |

| Embryo segmentation | Leaman et al., 2005 | ||

| dme-miR-11 | Apoptosis | rpr, hid, grim, skl | Truscott et al., 2012; Ge et al.,2012 |

| dme-miR-14 | Suppression of cell death; fat metabolism | Xu et al., 2003 | |

| Ecdysone signaling | EcR | Varghese & Cohen, 2007 | |

| Insulin production | Sug | Varghesse et al., 2010 | |

| Apoptosis | Kumarswamy & Chandna, 2010 | ||

| dme-miR-31 | Embryo segmentation | Leaman et al., 2005 | |

| dme-miR-34 | Neurodegeneration | Liu et al., 2012 | |

| dme-miR-124 | Neuronal development | Ana | Weng & Cohen, 2012 |

| dme-miR-184 | Germline stem cell differentiation | Sax | Iovino et al., 2009 |

| dme-miR-263 | Apoptosis | Hid | Hilgers et al., 2010 |

| aae-miR-275 | Blood digestion; egg maturation | Bryant et al., 2010 | |

| dme-miR-277 | Neurodegeneration | Drep-2, Vimar | Tan et al., 2012 |

| dme-miR-278 | Energy homeostasis | Teleman et al., 2006 | |

| Germline stem cell division | Yu et al., 2009 | ||

| dme-miR-279 | CO2 receptor formation | Nerfin-1 | Cayirlioglu et al., 2008 |

| dme-miR-309 | Germline stem cell division | Yu et al., 2009 | |

| dme-miR-310-313 cluster | Synaptic transmission | Khc-73 | Tsurudome et al., 2010 |

| dme-miR-315 | Wnt/Wg signa1ing | Axn, Notum | Silver et al., 2007 |

| aae-miR-2940 | Wolbachia maintenance | m41 ftsh | Hussain et al., 2011 |

dm = Drosophila melanogaster, ae = Aedes aegypti.

7.1. MicroRNA involvement in aging

The conserved miRNA, miR-14, was shown to play a role in the 20-hydroxyecdysone (20E) signaling pathway in Drosophila. Mir-14s role in the 20E signaling pathway accounts for the mir-14 mutants decreased lifespan (Varghese & Cohen, 2007). Computational predictions of miR-14 targets identified the ecdysone receptor (EcR) as a miR-14 target, and the removal of EcR in the mir-14 mutant fly resulted in a rescue effect of fly lifespan. It was demonstrated that 20E reduces the level of miR-14 in the Drosophila fat body through an autoregulatory loop, which responds accordingly to ecdysone levels.

In the Drosophila testis stem cell niche, aging results in a decrease in the self-renewal factor Unpaired (Udp), leading to a loss of germline stem cells (Boyle et al., 2007). IGF-II messenger RNA binding protein (Imp) was shown to stabilize Udp mRNA by counteracting endogenous siRNAs; however, an aging-related decline of Imp was heavily dependent on an aging-related increase of the heterochromatic miRNA, let-7 (Toledano et al., 2012). This study suggests a role for let-7 during stem cell maintenance, in which Imp preserves niche function in young flies until let-7 and endogenous siRNAs trigger an aging switch leading to Udp instability and, consequentially, germline stem cell loss.

7.2. MicroRNA control of apoptosis

The process of programmed cell death, or apoptosis, is a vital component of many processes including development, immunity and normal cell turnover. In Drosophila, apoptosis has been shown to be highly regulated by miRNAs; including miR-263, miR-14, bantam and the miR-2 family (Ge et al., 2012; Hilgers et al., 2010; Li & Padgett, 2012; Truscott et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2003). The miR-2 seed family miRNA, miR-11, arises intronically from the Drosophila E2F1 homolog gene dE2f1, a transcription factor that regulates the expression of genes associated with cell proliferation and cell death regulators. The mir-11 mutants are highly sensitive to dE2f1-dependent apoptosis (Truscott et al., 2012) and present defects in the CNS development (Ge et al., 2012). The pro-apoptotic genes reaper (rpr) and head involution defective (hid), which are regulated by dE2F1 upon DNA damage, were repressed by miR-11 expression (Truscott et al., 2012). In addition, miR-6 and miR-11 were shown to play overlapping roles in limiting the level of apoptosis during Drosophila embryonic development through the regulation of rpr, hid, grim and sickle (Ge et al., 2012).

The miRNA miR-263a/b also plays important roles in regulating apoptosis. The mir-263a mutant depicts a loss of interommatidial bristle (IOB) sensory organs due to increased apoptosis, indicating a function in apoptosis inhibition (Hilgers et al., 2010). Computational predictions, overexpression “phenocopy” analysis and luciferase reporter assays indicated hid to be a target of miR-263a, suggesting that miR-263a/b is involved in protecting the Drosophila IOB bristles from apoptosis by down-regulating the hid pro-apoptotic gene. Drosophila miR-263 belongs to a conserved family of miRNAs, that includes miR-183, miR-96 and miR-182 in mammals. Interestingly, miR-96 has been identified as the cause of hair cell degeneration and hearing loss in mice (Lewis et al., 2009) and humans (Mencia et al., 2009). Hence, Drosophila miR-263a/b could serve as an excellent model in understanding the regulatory role of this family of conserved miRNAs from a medical perspective.

7.3. MicroRNA mediated cell growth and proliferation

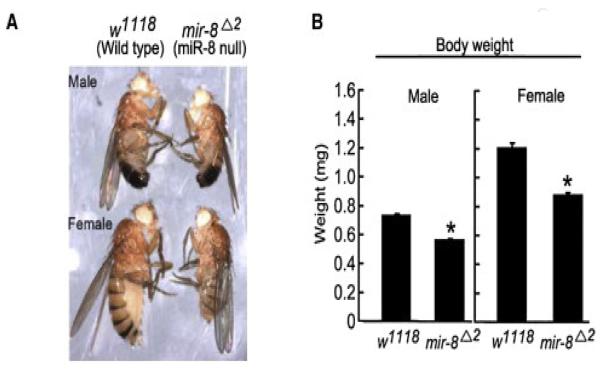

The highly conserved miRNA, miR-8 has implicated roles in the insulin signaling pathway in the Drosophila larval fat body (Hyun et al., 2009). Fly miR-8 mutants have a smaller body size and are defective in insulin signaling of the fat body (Fig. 5). Bioinformatics target predictions for Drosophila miR-8 and its human homologs from the miR-200 family identified U-shaped (Ush) and its human ortholog Friend of GATA 2 (FOG2) to be targets of miR-8/miR-200. It was proposed that Drosophila miR-8 expression in the larval fat body represses Ush, allowing the formation of the PI3K complex, thereby stimulating insulin signaling and promoting cell growth.

Fig. 5.

The highly conserved miRNA, miR-8 has implicated roles in the insulin signaling pathway in the Drosophila larval fat body. (a) Both male and female miR-8 null flies have a smaller body size compared their wild-type counterparts. (b) Average weight of wild-type (male, n = 65; female, n = 70) and miR-8 null (male, n = 60; female, n = 40) flies. (Hyun et al., 2009, with permission).

More recently, the miR-8/miR-200 family has also been shown to function as a potent inhibitor of Notch-induced overgrowth and tumor metastasis in both Drosophila and human cells (Vallejo et al., 2011). Overexpression of miR-8 in flies caused inhibition of growth and tumorigenesis. The Drosophila Notch receptor ligand Serrate (Ser) and its human ortholog JAGGED1 were found to be targets of miR8 and miR200c/miR-141, respectively. Functional findings of Drosophila miR-8 lead to the discovery that human miR-200c and miR-141 directly inhibit JAGGED1, impeding the proliferation of human metastatic prostate cancer cells. Conserved miRNAs in the Drosophila insect system can uncover many miRNA functions with clinical interests, and in the case of miR-8 provides novel insights to the human miR-200 family functioning in cell growth, tumorigenesis and cancer biology.

7.4.Carbon dioxide receptor formation is mediated by miR-279

Locations of carbon dioxide (CO2) receptors differ between insect species, and they provoke different olfactory behaviors. While in some blood feeding insects CO2 sensory receptors are localized to the maxillary palps and promote host identification (Bogner, 1992; Grant & O’Connell, 1996; Kellogg, 1970), the Drosophila CO2 receptor complex is located in the antennae and elicits a repellent response (Jones et al., 2007; Kwon et al., 2007). The loss of miR-279 in Drosophila leads to the formation of a CO2 sensory system in maxillary palps, which is similar to those found in mosquitoes (Cayirlioglu et al., 2008). Genetic mosaic screening designed to identify mutations in the gene encoding the pleiotropic transcription factor Prospero (Pros), depicted a miR-279-like phenotype (Hartl et al., 2011). Moreover, Pros was shown to participate in the transcriptional regulation of miR-279 expression. A comparison of Pros targets and bioinformatics target predictions for miR-279 identified the transcription factors Nerfin-1 and Escargot (Esg) as a target of both molecules. Overexpression of Nerfin-1 and Esg together indicated that Nerfin-1 and Esg are essential for the development of CO2 receptor formation in maxillary palps. Hence, microRNA mediated regulation provides some diversity to CO2 receptor localization and olfactory behavior in insects.

7.5. MicroRNA regulation of metabolism

The Drosophila miR-14 regulates insulin production and metabolism, which accounts for the metabolic defect in mir-14 mutant flies (Varghese et al., 2010). MiR-14 functions in the insulin producing cells of the fly brain. Overexpression of putative targets and GFP-reporter assay indicated Sugarbabe to be a target of miR-14. The exact role of Sugarbabe is unknown; however, it is speculated that Sugarbabe may regulate gene expression in insulin producing cells.

7.6. Involvement of miRNAs in neurodegeneration

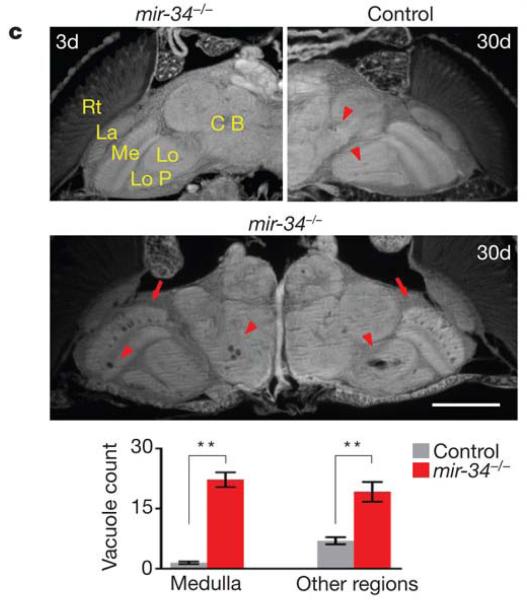

Microarray analysis of various miRNAs expressed in the Drosophila brain indicated that miR-34 increases in expression as flies age (Liu et al., 2012a). Loss of miR-34 results in accelerated brain aging, late-onset brain degeneration and a decline in survival, while miR-34 up-regulation extends median lifespan and mitigates neurodegeneration (Fig. 6). Computational target predictions and experimental validation has indicated that Eip74EF, in particular the E74A transcript, is a miR-34 target. Interestingly, miR-34c levels are elevated in the hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease patients and mouse models, and may serve as a possible therapeutic target for dementia treatment (Zovoilis et al., 2011). Function and target identification of this highly conserved miRNA in Drosophila may lead to a greater understanding of miR-34 involvement in neurodegeneration in humans.

Fig. 6.

In Drosophila, miR-34 modulates age-associated processes. Loss of miR-34 results in accelerated brain aging, late-onset brain degeneration and a decline in survival. Top left panel, miR-34 mutant flies have normal brain morphology at 3d. Major anatomical structures: CB (central brain), Lo (lobula), LoP (lobula plate), Me (medulla), La (lamina) and Rt (retina). At 3d, control flies have normal brain morphology (not shown), but develop a small number of sporadic vacuoles at 30d (top right panel, arrowheads). Middle panel, aged miR-34 mutants (30d) show striking vacuoles in the medulla (arrows) and other regions of the brain (arrowheads). Bottom, the number of vacuoles in miR-34 mutants is significantly higher than in controls (22.2± 1.8 vs 1.5±0.3 in medulla; 19.2±2.5 vs 7.0±0.9 in other regions of the brain; **=p < 0.001, one-way analysis of variance, with post test: Tukey’s multiple comparison test). Mean ± s.e.m., n=10 independent male fly brains. Scale bar: 0.1mm. (Liu et al., 2012a, with permission).

The miRNA, miR-8, has also been implicated to play a role in preventing neurodegeneration in Drosophila (Karres et al., 2007). Fly mir-8 mutants exhibited reduced survival, and mosaic analysis of this mutation showed defects in legs and wings, and impaired neuromuscular coordination. Atrophin has been determined to be a target of miR-8 and the misregulation of Atrophin results in developmental defects similar to those seen in mir-8 mutant flies.

7.7. MicroRNAs as canalization factors

Insect miRNAs have been implicated to buffer developmental processes from environmental fluctuations and other perturbation factors. In Drosophila, miR-7 acts within gene networks involved in photoreceptor and proprioceptor determination to buffer these networks against environmental changes and other stresses (Li et al., 2009a). Mutant mir-7 larval flies subjected to oscillating temperature changes exhibit drastic disturbances in gene expression, and proprioceptor and olfactory SOP determination, indicating that miR-7 is essential for stable gene expression and cell fate determination during perturbation.

In addition, miR-8 was shown to act as a positive regulator of pigmentation in Drosophila and is required for proper spatial patterning of pigment on adult female abdomens (Kennell et al., 2012). Mutant mir-8 adult female flies exhibit decreased pigmentation of the dorsal abdomen, with a pattern of pigmentation similar to control flies reared at a higher temperature. These mir-8 mutant flies were more sensitive to higher temperatures and depicted decreased rates of eclosion. Together, these results suggest that miR-8 acts as a powerful buffer to stabilize gene expression patterns during environmental fluctuations.

7.8. MicroRNA regulation of the Wnt/Wingless signaling pathway

The Wnt/Wingless (Wg) signaling pathway is highly conserved and plays many important roles in animal development and disease. The exact levels of the Wg/Wnt pathway output are essential for various biological functions; therefore, Wg/Wnt signaling is carefully regulated by the interplay of many positive and negative factors. Using a transcriptional reporter screen to identify miRNAs that regulate Wnt/Wg signaling, ectopic miR-315 was shown to be a potent and specific activator of Wg signaling in Drosophila clone-8 cell and in vivo (Silver et al., 2007). The action of miR-315 is mediated by the direct inhibition of Axin and Notum, which are essential negatively acting components of the Wg pathway.

In a genetic screen for Wg antagonists in Drosophila, miR-8 was found to inhibit Wg signaling (Kennell et al., 2008). Many players in the Wg signaling pathway were found to be targets of miR-8, including the inhibition of TCF protein expression and direct targeting of two positive regulators, wntless (wls), a transmembrane protein required for Wg secretion, and a zinc finger protein, CG32767. Additionally, mammalian miR-8 orthologs, the miR-200 family, were shown to regulate adipogenesis in ST2 marrow stromal cells, possibly by inhibiting Wnt signaling.

8. Expression profiling and functions of miRNAs in non-drosophilid insects

The functions of many miRNAs and their targets have been deciphered in Drosophila; however, an understanding of miRNA roles non-drosophilid insects is very limited. Despite the recent progress in identification of putative insect miRNAs; the validation, and detailing the functions and targets of these presumed miRNAs remains a challenging task due to the limited experimental toolbox that is available for non-drosophilid insects. However, on-going high throughput genome-wide efforts and recent functional analysis of miRNAs in non-drosophilid insects have begun to unravel the roles of miRNAs in these organisms. Recent studies have suggested that miRNAs may play key regulatory roles in various insect mechanisms; including social behavior, reproduction, metamorphosis and species specific events.

8.1. MicroRNAs and social behavior

Small RNA libraries were produced from the honey bee, Ap. mellifera, in an attempt to further understand the gene regulatory networks involved in the social behavior of this insect (Chen et al., 2010; Greenberg et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012b). A miRNA analysis from honey bee forager and nurse heads of the same age (7 days old) identified 97 miRNAs, 17 of which were novel and 25 Hymenoptera specific (Greenberg et al., 2012). The miRNAs miR-184 and miR-2796 were shown to be upregulated in forager heads. Interestingly, miR-2796 was found to arise intronically from the Phospholipase C (PLC)-epsilon gene, a gene shown to be involved in neuronal development and a predicted target of miR-2796. Validation and experimental evidence of PLC-epsilon as an authentic target of ame-miR-2796 has yet to be performed.

Simultaneously another miRNA analysis in females nursing larvae and returning pollen forager honey bee heads identified 67 novel miRNAs in Ap. mellifera, and found that nine miRNAs were significantly differentially expressed between nurses and foragers (Liu et al., 2012b). The miRNAs, miR-31a, let-7, miR-279 and miR-275 were more up-regulated in nurses compared to foragers, while miR-13b, miR-133, miR-210, miR-278 and miR-92a were down-regulated in nurses compared to foragers. Although functional characterization of these miRNAs has yet to be determined, their differential expression may indicate possible roles in the behavioral transition from nursing to foraging. Interestingly, these two studies produced differing results, possibly due to experimental technique and a difference of nurse and forager age at collection.

8.2. Putative functions of miRNAs in insect reproduction

With the availability of the pea aphid genome sequence, putative miRNAs have been experimentally identified and mapped to the pea aphid genome (Legeai et al., 2010). This study discovered the presence of 149 miRNAs, including 55 conserved and 94 novel miRNAs. Five miRNAs - miR-34, miR-X47 and miR-X103, miR-307* and miR-X52* - showed differential expression between two parthenogenetic morphs, sexuparae and virginoparae. Differences in expression between morphs indicate a possible role of miRNAs in switching the reproductive mode from parthenogenesis to sexual reproduction in A.pisum; however, the exact function of these miRNAs has not been established.

Analysis of small RNA libraries produced from whole body and adult ovaries of the cockroach Blattella germanica revealved 38 known miRNAs, 11 known miRNA*s, 70 insect miRNA candidates and 170 candidates specific to B. germanica (Cristino et al., 2011). The majority of the novel miRNA candidates have been found to be primarily expressed in the cockroach ovary, suggesting roles in ovarian development. RNAi experiments targeting Dcr-1 were used to validate miRNA candidates identified in this study. The putative miRNAs tested in the Dcr-1 RNAi assay were determined to be true miRNAs.

8.3. miRNA involvement in metamorphosis

MicroRNAs have also been identified through sRNA cloning and expression profiling in the silkworm, B. mori (Jagadeeswaran et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2009). Fourteen independent sRNA libraries were produced from different life stages of the silkworm ranging from fertilized eggs to pre-diapaused embryos to moth. These libraries yielded the identification of 55 miRNAs (Yu et al., 2008). In another study, 354 miRNAs were identified in the silkworm, the majority of which were egg and pupa specific, suggesting a role in embryogenesis and metamorphosis (Zhang et al., 2009). An additional sRNA expression study in silkworm identified 101 conserved and 15 novel silkworm-specific miRNAs (Jagadeeswaran et al., 2010). In this work, miRNAs were grouped into three major categories based on their expression pattern. Together, these differential expression patterns of miRNAs during silkworm development suggest key roles in diverse aspects of physiology and development.

Small RNA libraries were created from mixed larval and pupal wings of the two color pattern races of Heliconius melpomene: H. m. rosina, which has a yellow hindwing bar encoded by the HmYb locus and H. m. melpomene, which does not (Surridge et al., 2011). This study revealed 142 Heliconius miRNAs and several were differentially expressed between color pattern races. Interestingly, two miRNAs, miR-193 and miR-2788, were found to arise from an intergenic region near the HmYb locus. Both miRNAs were up regulated in the butterfly wing post-pupation, indicating a possible role of miRNAs in butterfly wing development and color patterning of Heliconius butterflies.

Three developmental stages of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens - adult male, adult female and last instar female nymph - were analyzed through production and sequencing of three small RNA libraries (Chen et al., 2012). This study revealed 452, 430 and 381 conserved miRNAs in adult males, adult females and last instar female nymphs, respectively. These included 70 novel miRNAs with many being differentially expressed between these stages. Additionally, four small RNA libraries were constructed from embryos, 4th instar feeding larvae, pupae, and adult Manduca sexta, and yielded 163 conserved miRNAs and 13 novel miRNA candidates (Zhang et al., 2012). Expression profiling indicated that M. sexta miRNAs are dynamically regulated throughout their life cycle indicating roles in metamorphosis and development.

8.4. MicroRNA regulation of silk production

Small RNA libraries produced from the anterior-middle and posterior silk glands of B. mori identified 202 novel and 55 previously reported miRNAs, many of which were either insect or silkworm specific (Liu et al., 2010). Computational prediction of targets of a select group of miRNAs in silkworm indicated that many of these miRNAs target the 3′ UTR of fibroin L chain transcripts (Cao et al., 2008). GUS-reporter assay indicated that miR-33, miR-190, miR-276 and miR-7 may indeed work to regulate fibroin L chain transcripts; however, experimental evidence has yet to be reported. In addition, bioinformatics predictions indicated miR-2b binding sites in the silk protein P25 (Huang et al., 2011). Expression patterns of miR-2b verses P25 indicated possible post-transcriptional regulation of P25 by miR-2b; however, P25 was not confirmed as an authentic target of miR-2b.

8.5. Unraveling miRNA functions in arthropod disease vectors

MicroRNAs were first experimentally identified in mosquitoes using a direct cloning procedure in the malaria vector, mosquito Anopheles gambiae (Winter et al., 2007). This approach lead to the identification of 18 miRNAs, three of which were believed to be mosquito-specific and six indicated digestive system specificity. The effect of a blood-meal on miRNA expression in midguts exhibited induction of miR-34, miR-317, miR-1174, and miR-1175; while Plasmodium berghei infection resulted in an induction of miR-989 in the midgut. The exact role of these miRNAs in the female mosquito during immune system and/or blood meal associated events has yet to be determined.

Twenty-seven miRNAs were uncovered in Anopheles stephensi female mosquitoes, with four of these mosquito-specific miRNAs (Mead & Tu, 2008). The mosquito-specific miRNA, termed miR-x2, was shown to be an adult female specific miRNA that is highly expressed in the ovaries post blood meal, suggesting a possible role in mosquito reproductive events. However, the function of miR-x2 in the female mosquito has not been characterized.

Expression profiling of miRNAs in Aedes aegypti greatly expanded the experimental identification of miRNAs in mosquitoes (Li et al., 2009b). This study indentified 98 pre-miRNAs corresponding to 86 distinct miRNA species, thirteen of which are mosquito-specific. Many miRNAs in these libraries were induced in the midgut upon the uptake of a blood meal, indicating a possible role of these miRNAs during blood feeding processes.

Discovery of miRNAs expressed in Ae. albopictus C7/10 cell lines and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes lead to the identification of 65 and 77 miRNAs respectively, 60 of which were conserved and seven novel (Skalsky et al., 2010). In addition, the effect of West Nile Virus (WNV) infection of miRNA expression resulted in downregulation of miR-989 and upregulation of miR-92, indicating a possible role in mediating immune system responses to WNV infection in the mosquito. However, the specific role of miR-989 and miR-92 in the mosquito remains unknown.

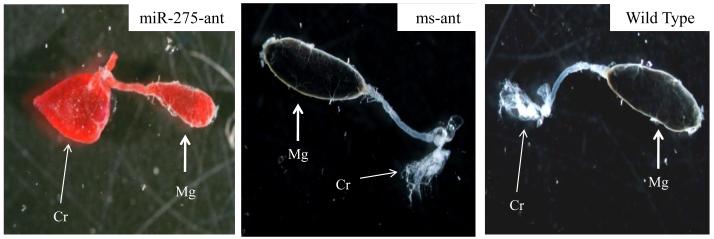

An expression analysis of 27 conserved miRNAs in female mosquitoes depicted that many miRNAs, including miR-275, miR-14 and miR-8, were induced after the uptake of a blood meal (Bryant et al., 2010). Specific antagomir inactivation of miR-275 resulted in a dramatic defect in blood digestion; in mosquitoes examined 24 h post-blood meal, blood was not digested in the posterior midgut and instead filled a specialized anterior portion of the digestive system, called the crop, which is normally used for storing nectar (Fig. 7). Targets of miR-275 and the pathway in which they function have yet to be determined in the female mosquito; however, interestingly, experiments with in vitro incubated fat bodies from non-blood fed female mosquitoes have shown that miR-275 was elevated in the presence of 20E, suggesting that the regulatory circuit regulating the expression of genes encoding yolk protein precursors is also involved in the control of this miRNA.

Fig. 7.

Antagomir depletion of miR-275 drastically affects the ability of the Aedes aegypti female mosquito to digest blood. Mosquitoes were injected with either miR-275 antagomir (miR-275-ant) or missense oligonucleotide antagomir probe (ms-ant) at 1 day post-eclosion. Digestive systems, containing the crop (Cr), and anterior and posterior midguts (mg), were dissected 24 h after blood feeding and compared with untreated control (Wild Type). Digestive systems from miR-275-ant treated mosquitoes were full of red-colored (undigested) blood that was mostly located in a largely extended crop. Midguts from ms-ant mosquitoes were similar to those from wild type controls with a black bolus of digested blood. (From Bryant et al. 2010, with permission).

Additionally, Wolbachia infected mosquitoes lead to differential expression of 35 mosquito miRNAs, including miR-2940 which was shown to be induced after Wolbachia infection and essential for Wolbachia replication (Hussain et al, 2011). Wolbachia is particularly interesting in that it is a maternally transmitted endosymbiotic bacterium which has been shown to induce resistance to a variety of pathogens, including Dengue virus (Bian et al., 2010; Moreira et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2011). The Metalloprotease m41 ftsh gene was determined to be a target of miR-2940 through computational predictions and, similar to miR-2940, found to be important for Wolbachia replication. Interestingly, miR-2940 was shown to induce the expression of this transcript, suggesting that miR-2940 may work by enhancing the mRNA transcript level or by increasing mRNA stability.

9. Conclusions

Although the first miRNA was identified almost 20 years ago, it is only recently that we have begun to understand the biogenesis and diversity of these regulatory molecules. With the constant discovery of critical miRNA machinery, such as Nibbler, miRNA biogenesis has proved more complex than originally thought. In addition, how a particular miRNA is targeted to and elicits its action on a target mRNA is not well understood. Further studies are needed to unravel the details of how a miRNA causes translational inhibition or mRNA decay, and why certain miRNA may have different mode of actions. Understanding these mechanisms would likely improve miRNA target identification and validation strategies.

The identification and characterization of miRNAs is a rapidly growing area of research. Continuing genome wide efforts in insect miRNA discovery and expression profiling have revealed that conserved and species specific miRNAs may play important roles in insect biology. There are wide discrepancies in data concerning the number of miRNAs detected in different studies of various insect species; however, as genomic and bioinformatic technologies progress, a better grasp of the miRNA repertories in insects is expected. Insect or species specific miRNAs may have exclusive roles in particular organisms and are possibly involved in the regulation of lineage specific pathways. Thus, the identification and discovery of highly specific miRNAs could serve as the basis for novel genetic strategies to target unwanted agricultural pests and disease vectors.

In humans, miRNAs have been shown to play key roles in many medically important events and are the target for various novel therapeutic approaches. Understanding the function of conserved miRNAs in insects has been an important step in the functional characterization of miRNAs in mammalian cells and has pioneered the study of many medically important human miRNAs. Furthermore, hormones are major regulators of important physiological processes such as growth, development and reproduction in various insect species. Experiments have identified several miRNAs that have been implicated in the modulation of hormonal regulatory cascades in Drosophila. The roles that these miRNAs and their targets play in hormonal regulation may provide key insights to developmental and reproductive cycles in non-drosophild insects.

To date, Drosophila melanogaster, Aedes aegypti and Bombyx mori have 430, 125 and 562 putative miRNAs respectively. Such drastic differences in the number of miRNAs identified between insect species maybe due to a variety of factors, including: features used to define a miRNA, temporal and spatial resolution miRNA profiling experiments, and evolutionary expansion of miRNA families and emergence of species specific miRNAs. Despite the discovery of numerous miRNAs in different insect species, the function of a large majority of these presumed miRNAs have yet to be determined. In the case of non-drosophilid insects lack of mutant libraries and transgenic tools has hampered our understanding of miRNA functions. Antagomir and spatiotemporal miRNA sponge transgenic tools represent powerful loss-of-function techniques that permit an alternative approach to classic genetic knockouts and maybe particularly useful in non-drosophilid insects. However, for many insect species, progress must be made in developing a genetic toolbox for the establishment of transgenic lines. In addition, deficiencies in genome annotations, and lack of 3′ UTR databases and target prediction programs have made the determination of miRNA targets difficult. Steps must be taken to adapt already established miRNA target prediction programs to other insect genomes, as well as produce new computational target prediction tools through our understanding of miRNA function and mode of action in insects. In addition, for insects with an incomplete and/or poorly annotated genome, progress must be made in providing an accurate, updated source of genome annotation and resource sharing databases. With the availability of miRNA target prediction tools and 3′ UTR databases for analysis of insect miRNA binding sites would further increase the likelihood of predicting functional miRNA binding sites in insect species.

Highlights (for review).

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are a class of endogenous regulatory RNA molecules 21-24 nucleotides in length that modulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level via imperfect base pairing to target sites within messenger RNAs (mRNA).

Typically, the miRNA “seed sequence” (nucleotides 2-8 at the 5′ end) binds complementary seed match sites within the 3′ untranslated region of mRNAs, resulting in either translational inhibition or mRNA degradation.

Numerous functions of miRNAs identified in Drosophila melanogaster have demonstrated a great significance of these regulatory molecules. However, elucidation of miRNA roles in no-drosophilid insects presents a challenging and important task.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grant 2R01 AI036959 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baek D, Villén J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzini AA, Lee MT, Giraldez AJ. Ribosome profiling shows that miR-430 reduces translation before causing mRNA decay in Zebrafish. Science. 2012;336:233–237. doi: 10.1126/science.1215704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behm-Ansmant I, Rehwinkel J, Izaurralde E. MicroRNAs silence gene expression by repressing protein expression and/or promoting mRNA decay. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:523–530. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellés X. Beyond Drosophila: RNAi in vivo and functional genomics in insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010;55:111–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNA.org resource: targets and expression. Nucl. Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–D153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. microRNA.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian G, Xu Y, Lu P, Xie Y, Xi Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000833. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biryukova I, Asmar J, Abdesselem H, Heitzler P. Drosophila mir-9a regulates wing development via fine-tuning expression of the LIM only factor, dLMO. Dev. Biol. 2009;327:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner F. Response properties of CO2-sensitive receptors in tsetse flies (Diptera: Glossina palpalis) Physiological Entomology. 1992;17:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack MT, Czaplinski K, Gorlich D. Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. RNA. 2004;10:185–191. doi: 10.1261/rna.5167604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchert GM, Lanier W, Davidson BL. RNA polymerase III transcribes human miRNAs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:1097–1101. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M, Wong C, Rocha M, Jones DL. Decline in self-renewal factors contributes to aging of the stem cell niche in the Drosophila testis. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:470–478. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton RJ, Davidson EH. Gene Regulation for Higher Cells: A Theory. Science. 1969;165:349–357. doi: 10.1126/science.165.3891.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Holtzman S, Kaufman T, Denell R. Characterization of the Tribolium Deformed ortholog and its ability to directly regulate Deformed target genes in the rescue of a Drosophila Deformed null mutant. Dev. Genes Evol. 1999;209:389–98. doi: 10.1007/s004270050269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant B, Macdonald W, Raikhel AS. MicroRNA miR-275 is indispensable for blood digestion and egg development in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:22391–22398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016230107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Tong C, Wu X, Lv J, Yang Z, Jin Y. Identification of conserved microRNAs in Bombyx mori (silkworm) and regulation of fibroin L chain production by microRNAs in heterologous system. Insect Biochem. & Mol. Bio. 2008;38:1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayirlioglu P, Kadow IG, Zhan X, Okamura K, Suh GS, Gunning D, Lai EC, Zipursky SL. Hybrid neurons in a microRNA mutant are putative evolutionary intermediates in insect CO2 sensory systems. Science. 2008;319:1256–1260. doi: 10.1126/science.1149483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenik ES, Fukunaga R, Lu G, Dutcher R, Wang Y, Tanaka-Hall TM, Zamore PD. Phosphate and R2D2 restrict the substrate specificity of Dicer-2, an ATP-driver ribonuclease. Mol Cell. 2011;42:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheloufi S, Dos Santos CO, Chong MM, Hannon GJ. A Dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis pathway that requires Ago catalysis. Nature. 2010;465:584–589. doi: 10.1038/nature09092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yu X, Cai Y, Zheng H, Yu D, Liu G, Zhou Q, Hu S, Hu F. Next-generation small RNA sequencing for microRNAs profiling in honey bee Apis mellifera. Insect Mol. Biol. 2010;19:799–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Lu L, Hua H, Zhou F, Lu L, Lin Y. Characterisation and comparative analysis of small RNAs in three small RNA libraries of the Brown Planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) PLoS one. 2012;7:e32860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada TP, Finn KJ, Ji X, Baillat D, Gregory RI, Liebhaber SA, Pasquinelli AE, Shiekhatter R. MicroRNA silencing through RISC recruitment of eIF6. Nature. 2007;447:823–828. doi: 10.1038/nature05841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decode microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IK, Hyun S. Conserved microRNA miR-8 in fat body regulates innate immune homeostasis in Drosophila. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012;37:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook HA, Koppetsch BS, Wu J, Theurkauf WE. The Drosophila SDE3 homolog armitage is required for oskar mRNA silencing and embryonic axis specification. Cell. 2004;116:817–829. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino AS, Tanaka ED, Rubio M, Piulachs MD, Belles X. Deep sequencing of organ- and stage-specific microRNAs in the evolutionarily basal insect Blattella germanica (L.) (Dictyoptera, Blattellidae) PLoS one. 2011;6:e19350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]