Abstract

Purpose

To test whether supplementation with alternate-day vitamin E or daily vitamin C affects the incidence of the diagnosis of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in a large-scale randomized trial of male physicians.

Design

Randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial.

Participants

We included 14 236 apparently healthy United States male physicians aged ≥50 years who did not report a diagnosis of AMD at baseline.

Methods

Participants were randomly assigned to receive 400 international units (IU) of vitamin E or placebo on alternate days, and 500 mg of vitamin C or placebo daily. Participants reported new diagnoses of AMD on annual questionnaires and medical record data were collected to confirm the reports.

Main Outcome Measures

Incident diagnosis of AMD responsible for a reduction in best-corrected visual acuity to ≤20/30.

Results

After 8 years of treatment and follow-up, a total of 193 incident cases of visually significant AMD were documented. There were 96 cases in the vitamin E group and 97 in the placebo group (hazard ratio [HR], 1.03; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–1.37). For vitamin C, there were 97 cases in the active group and 96 in the placebo group (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.75–1.31).

Conclusions

In a large-scale, randomized trial of United States male physicians, alternate-day use of 400 IU of vitamin E and/or daily use of 500 mg of vitamin C for 8 years had no appreciable beneficial or harmful effect on risk of incident diagnosis of AMD.

The effectiveness of nutritional supplements in the prevention of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the leading cause of irreversible vision loss in United States adults,1,2 was demonstrated in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS).3 The AREDS showed that daily supplementation with zinc and a high-dose antioxidant combination of vitamin E, vitamin C, and beta carotene could reduce the risk of advanced AMD by 25% in persons with intermediate AMD or advanced AMD in 1 eye. However, AREDS had insufficient power to determine whether the zinc and antioxidant combination could delay the onset or progression of early AMD. Because persons with early AMD are at increased risk of developing advanced AMD,4,5 the demonstration of a nutritional means to prevent the early stages of AMD would have important public health implications.

Evidence from laboratory studies, studies in animals, and several observational studies in humans provide some support for a possible benefit for antioxidant supplements in the prevention of early AMD.6-8 However, the results of completed randomized trials in persons with early or no AMD have been disappointing. In these trials, supplementation with vitamin E for 4 to 6 years in men,9,10 and 6 to 10 years in women,10,11 has had little effect on AMD occurrence. Similarly, supplementation with beta carotene for up to 10 years was found to have no appreciable effect on AMD incidence in men.9,12 Nonetheless, important gaps in knowledge remain, particularly with respect to the antioxidant nutrients tested in AREDS. For example, there are no randomized trial data for treatment with vitamin C alone among persons with early or no AMD, and no data in men for vitamin E treatment durations of >6 years.

In this report, we present the final results for AMD from the vitamin E and vitamin C components of the Physicians’ Health Study II (PHS II). The PHS II is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial designed to examine the effects of vitamin E, vitamin C, and a multivitamin in the prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease in a population of 14 641 male physicians. A total of 14 236 of these men did not report a diagnosis of AMD at baseline and are included in this report. The findings reported here represent the longest treatment duration for supplemental vitamin E in men, and the first trial data for treatment with vitamin C alone, in the prevention of incident AMD.

Methods

Study Design

The PHS II is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2×2×2×2 factorial trial evaluating alternate day vitamin E (400 international units [IU] of synthetic α-tocopherol; BASF Corporation, Florham Park, NJ) or its placebo, daily vitamin C (500 mg synthetic ascorbic acid; BASF Corporation) or its placebo, and a daily multivitamin (Centrum Silver; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Madison, NJ) or its placebo in the prevention of cancer and cardiovascular disease among 14 641 male physicians aged ≥50 years.13 A fourth randomized component, alternate day beta-carotene (50 mg Lurotin; BASF Corporation) or placebo, was terminated in March 2003. Diagnosed AMD was a prespecified secondary endpoint of PHS II. The final results of the vitamin E and vitamin C components of the trial with respect to cancer,14 cardiovascular disease,15 and cataract16 have recently been published. The multivitamin component is continuing at the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee.

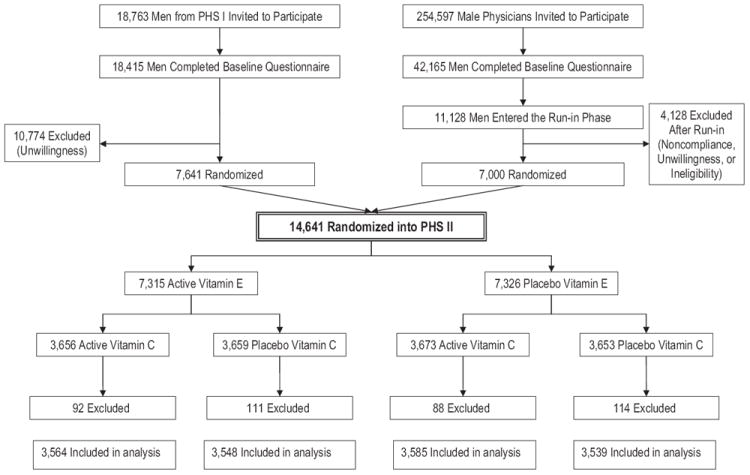

The study design for PHS II has been described elsewhere.13 Briefly, recruitment, enrollment, and randomization of men into PHS II occurred in 2 phases (Figure 1). Phase I began in 1997 and was comprised of 7641 willing and eligible participants from PHS I12, 17-19 who retained their original beta-carotene treatment assignment and were newly randomized to vitamin C, vitamin E, and a multivitamin. Phase II began in 1999 and consisted of 7000 new physician-participants identified from a list provided by the American Medical Association who were independently randomized to each of beta-carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, and a multivitamin, or their matching placebos. All participants provided written informed consent, and the trial was approved by the institutional review board of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the vitamin E and vitamin C components of the Physicians’ Health Study (PHS) II. A total of 405 participants who had a diagnosis of age-related macular degeneration at baseline were excluded.

Participants were sent annual questionnaires on which they provided information about their compliance with study pill taking and the occurrence of any new endpoints including AMD. Treatment and follow-up continued in blinded fashion through August 31, 2007, the scheduled end of the vitamin E and C components of PHS II. Morbidity and mortality follow-up were extremely high, at 95.3% and 97.9%, respectively.

Compliance with pill taking was based on self-report and was defined as taking at least two-thirds of the study agents. For vitamin E, compliance at 4 years was 78% in the active group and 77% in the placebo group (P = 0.12), and at the end of follow-up (mean of 8 years), compliance was 72% and 70%, respectively (P = 0.004). For vitamin C, compliance at 4 years was 78% in both the active and placebo groups (P = 0.99), and at the end of follow-up, compliance was 71% in both groups (P = 0.54).

Ascertainment and Confirmation of Age-Related Macular Degeneration

We excluded participants who reported a prior diagnosis of AMD at baseline (n = 405). Participants who reported a new diagnosis of AMD during follow-up were asked to provide a written consent to contact the treating ophthalmologist or optometrist. Ophthalmologists and optometrists were contacted by mail and asked to complete an AMD questionnaire that requested information about the date of initial diagnosis, the best-corrected visual acuity at the time of diagnosis, and the date when best-corrected visual acuity reached ≤20/30 (if different from the date of initial diagnosis). Information was also requested about signs of AMD observed (drusen, retinal pigment epithelium [RPE] hypo/hyperpigmentation, geographic atrophy, RPE detachment, subretinal neovascular membrane, or disciform scar) when the visual acuity was first noted to be 20/30 or worse, and the date when exudative neovascular disease (defined by presence of RPE detachment, subretinal neovascular membrane, or disciform scar), if present, was first noted. The questionnaire also asked whether there were other ocular abnormalities that could explain or contribute to visual loss and, if so, whether the AMD, by itself, was significant enough to cause the best-corrected visual acuity to be reduced to ≤20/30. Medical records were obtained for >90% of participants reporting AMD.

The primary prespecified endpoint was a diagnosis of visually significant AMD defined as a self-report confirmed by medical record evidence of an initial diagnosis after randomization but before August 31, 2007, with best-corrected visual acuity loss to ≤20/30 attributable to AMD. We also defined 2 secondary endpoints: AMD with or without vision loss, composed of all incident cases confirmed by record review, and advanced AMD, composed of cases of exudative neovascular AMD plus cases of geographic atrophy.

The present report includes the 14 236 participants who did not report a prior diagnosis of AMD at baseline. Of these, 7112 were in the vitamin E group and 7124 were in the vitamin E placebo group; 7149 were in the vitamin C group and 7087 were in the vitamin C placebo group (Figure 1).

Statistical Analysis

The estimated power of the trial for incident diagnosis of visually significant AMD, the primary endpoint, was based on event rates observed during the first 3.7 years of follow-up. We expected the study to have adequate power (81.3%) to detect a 25% reduction in the hazard of visually significant AMD. With 193 confirmed events, the study had adequate power (84.0%) to detect a 35% reduction in the hazard of visually significant AMD.

We compared baseline characteristics in the vitamin E and vitamin C groups using 2-sample t tests, χ2 tests for proportions, and tests for trend for ordinal categories. Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate cumulative incidence over time by randomized group, and we compared the curves using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) of AMD among those in the treated group (vitamin E or vitamin C) compared to placebo after adjustment for age (years) at baseline and randomized beta-carotene, vitamin E or vitamin C, and multivitamin assignments. Models were also fit separately within 3 age groups: 50 to 59, 60 to 69, and ≥70 years. Tests of trend of the effect of age on any association between vitamin E or vitamin C and AMD were calculated by including a term for the interaction of the antioxidant and age (expressed as a continuous variable with values of 1–3 corresponding with the 3 age groups) in a proportional hazards model. Interaction terms were used to test for additivity of the 2 antioxidant agents using multiplicative terms in the Cox model. For each HR, the 95% confidence intervals (CI) and 2-sided P values were calculated.

We also analyzed subgroup data by categories of baseline variables that are possible risk factors for AMD. We explored possible effect modification by using interaction terms between subgroup indicators and antioxidant assignment, and we tested for trend when subgroup categories were ordinal.

We considered individuals, rather than eyes, as the unit of analysis and we classified individuals according to the status of the worse eye as defined by disease severity. When the worse eye was excluded because of visual acuity loss attributed to other ocular abnormalities, the fellow eye was considered for classification.

Results

As shown in Table 1, baseline characteristics were evenly distributed in the active and placebo groups for vitamin E and vitamin C.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Randomized Groups in Physicians’ Health Study II*

| Total no. of Participants | Vitamin E

|

Vitamin C

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active (n = 7112) | Placebo (n = 7124) | Active (n = 7149) | Placebo (n = 7087) | ||

| Age, y | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 63.9 (8.9) | 64.0 (9.0) | 64.0 (9.0) | 63.9 (8.9) | |

| 50–59 | 5865 | 41.2 | 41.2 | 41.1 | 41.3 |

| 60–69 | 4648 | 32.7 | 32.6 | 32.5 | 32.8 |

| ≥70 | 3723 | 26.1 | 26.2 | 26.3 | 26.0 |

| Cigarette smoking | |||||

| Never | 8073 | 56.5 | 57.0 | 56.8 | 56.7 |

| Former | 5644 | 40.2 | 39.1 | 39.4 | 40.0 |

| Current | 507 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.3 |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Rarely/never | 2650 | 18.9 | 18.5 | 18.8 | 18.7 |

| ≥1 drink/month | 11 495 | 81.1 | 81.5 | 81.2 | 81.3 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||||

| <25 | 5930 | 42.1 | 41.3 | 41.6 | 41.9 |

| 25 to <30 | 6788 | 47.2 | 48.3 | 47.8 | 47.6 |

| ≥30 | 1500 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 10.5 |

| History of hypertension† | |||||

| Yes | 5897 | 41.3 | 42.0 | 41.2 | 42.2 |

| No | 8260 | 58.7 | 58.0 | 58.8 | 57.8 |

| History of high cholesterol‡ | |||||

| Yes | 5049 | 36.6 | 36.8 | 37.0 | 36.4 |

| No | 8708 | 63.4 | 63.2 | 63.0 | 63.6 |

| History of diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 853 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| No | 13 368 | 93.9 | 94.1 | 94.0 | 94.0 |

| Exercise ≥1 time/wk | |||||

| Yes | 8568 | 62.0 | 61.4 | 61.8 | 61.6 |

| No | 5319 | 38.0 | 38.6 | 38.2 | 38.4 |

| Self-reported history of CVD§ | |||||

| Yes | 717 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.9 |

| No | 13 519 | 95.0 | 94.9 | 94.8 | 95.1 |

CVD = cardiovascular disease.

Data are given as percentage of participants unless otherwise noted.

History of hypertension was defined as self-reported systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mmHg, or past or current treatment for hypertension.

History of high cholesterol was defined as self-reported total cholesterol level of ≥240 mg/dL or past or current treatment for high cholesterol.

History of CVD included nonfatal myocardial infarction or nonfatal stroke.

Over an average of 8 years of treatment and follow-up, a total of 363 cases of AMD were confirmed. These included 193 cases of visually significant AMD, approximately two-thirds of which were characterized by some combination of drusen and RPE changes at the time vision was first noted to be ≤20/30. Eighty men developed signs of advanced AMD during follow-up.

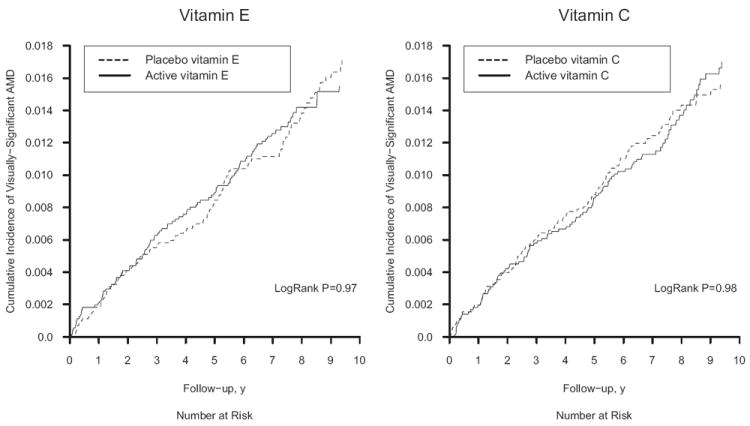

Vitamin E

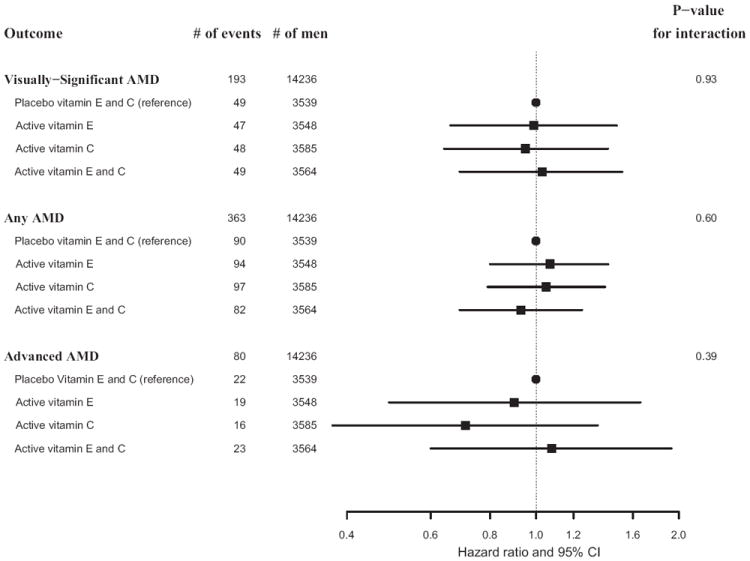

For the primary endpoint of visually significant AMD, there were 96 cases in the vitamin E group and 97 cases in the placebo group (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.78–1.37; Table 2). Cumulative incidence curves indicated little variation of the effect of vitamin E over time (Figure 2), and the test of proportionality of the HR over time was not significant (P = 0.33). Similar nonsignificant findings were observed when we examined all cases of AMD with or without vision loss (176 cases in the vitamin E group versus 187 in the placebo group; HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.79–1.19) and advanced AMD (42 cases in the vitamin E group versus 38 in the placebo group; HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.73–1.74; Table 2). For each endpoint, HRs did not vary significantly over the 3 age groups (P interaction, each >0.40). There were no effects of vitamin E supplementation on the primary endpoint of visually significant AMD in any subgroup of possible AMD risk factors studied (Table 3). Nor was there any evidence for modification of the lack of effect of vitamin E on AMD by vitamin C or beta-carotene treatment assignment (Table 3; Figure 3).

Table 2.

Confirmed Cases of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) According to Randomized Treatment Assignment in Three Age Groups

| Vitamin E

|

Vitamin C

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | Active (n = 7112) | Placebo (n = 7124) | HR* | 95% CI | P Value | P Interaction | Active (n = 7149) | Placebo (n = 7087) | HR† | 95% CI | P Value | P Interaction |

| Visually significant AMD | ||||||||||||

| 50–59 | 6 | 2 | 3.07 | 0.62–15.24 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 5 | 3 | 1.63 | 0.39–6.81 | 0.51 | 0.64 |

| 60–69 | 24 | 25 | 0.99 | 0.56–1.73 | 0.96 | 26 | 23 | 1.13 | 0.65–1.99 | 0.66 | ||

| ≥70 | 66 | 70 | 0.97 | 0.69–1.36 | 0.87 | 66 | 70 | 0.92 | 0.66–1.29 | 0.64 | ||

| Total | 96 | 97 | 1.03 | 0.78–1.37 | 0.81 | 97 | 96 | 0.99 | 0.75–1.31 | 0.95 | ||

| AMD | ||||||||||||

| 50–59 | 16 | 14 | 1.15 | 0.56–2.36 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 21 | 9 | 2.31 | 1.06–5.05 | 0.036 | 0.049 |

| 60–69 | 55 | 63 | 0.89 | 0.62–1.27 | 0.52 | 59 | 59 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.44 | 0.98 | ||

| ≥70 | 105 | 110 | 0.98 | 0.75–1.28 | 0.89 | 99 | 116 | 0.83 | 0.64–1.09 | 0.19 | ||

| Total | 176 | 187 | 0.97 | 0.79–1.19 | 0.79 | 179 | 184 | 0.96 | 0.78–1.18 | 0.68 | ||

| Advanced AMD | ||||||||||||

| 50–59 | 2 | 2 | 1.02 | 0.14–7.25 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 3 | 1 | 2.91 | 0.30–27.97 | 0.36 | 0.32 |

| 60–69 | 12 | 9 | 1.36 | 0.57–3.23 | 0.49 | 12 | 9 | 1.34 | 0.57–3.17 | 0.51 | ||

| ≥70 | 28 | 27 | 1.07 | 0.63–1.82 | 0.79 | 24 | 31 | 0.76 | 0.44–1.29 | 0.31 | ||

| Total | 42 | 38 | 1.13 | 0.73–1.74 | 0.51 | 39 | 41 | 0.94 | 0.60–1.45 | 0.77 | ||

CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

Adjusted for vitamin C, beta-carotene, and multivitamin treatment assignment.

Adjusted for vitamin E, beta-carotene, and multivitamin treatment assignment.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence rates of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in the vitamin E and vitamin C groups in the Physicians’ Health Study II.

Table 3.

Relative Rates of Visually-Significant Age-related Macular Degeneration by Randomized Treatment Assignment Within Subgroups in Physicians’ Health Study II*

| Vitamin E

|

Vitamin C

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No. of AMD/Total

|

No. of AMD/Total

|

|||||||

| Active | Placebo | HR (95% CI)† | P Interaction | Active | Placebo | HR (95% CI)‡ | P Interaction | |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||||

| Never | 35/4015 | 46/4058 | 0.82 (0.53–1.27) | 0.36 | 44/4059 | 37/4014 | 1.18 (0.76–1.83) | 0.52 |

| Former | 58/2859 | 47/2785 | 1.24 (0.84–1.82) | 50/2812 | 55/2832 | 0.89 (0.61–1.31) | ||

| Current | 3/234 | 4/273 | 0.83 (0.18–3.73) | 3/273 | 4/234 | 0.67 (0.15–2.99) | ||

| Alcohol use | ||||||||

| Rarely/never | 17/1338 | 21/1312 | 0.83 (0.44–1.57) | 0.42 | 18/1335 | 20/1315 | 0.86 (0.45–1.62) | 0.5 |

| ≥1 drink/month | 79/5726 | 76/5769 | 1.11 (0.81–1.52) | 79/5770 | 76/5725 | 1.05 (0.76–1.43) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||||

| <25 | 45/2992 | 43/2938 | 1.07 (0.70–1.63) | 0.79 | 41/2968 | 47/2962 | 0.87 (0.57–1.32) | 0.46 |

| 25 to <30 | 45/3352 | 46/3436 | 1.07 (0.71–1.61) | 47/3417 | 44/3371 | 1.01 (0.67–1.53) | ||

| ≥30 | 6/758 | 8/742 | 0.68 (0.24–1.98) | 9/756 | 5/744 | 1.85 (0.62–5.58) | ||

| History of hypertension | ||||||||

| Yes | 42/2922 | 51/2975 | 0.89 (0.59–1.33) | 0.32 | 46/2927 | 47/2970 | 0.99 (0.66–1.48) | 0.99 |

| No | 54/4152 | 46/4108 | 1.18 (0.80–1.76) | 51/4184 | 49/4076 | 0.98 (0.66–1.45) | ||

| History of high cholesterol | ||||||||

| Yes | 34/2517 | 33/2532 | 1.13 (0.70–1.83) | 0.58 | 34/2567 | 33/2482 | 0.98 (0.61–1.58) | 0.98 |

| No | 60/4361 | 63/4347 | 0.96 (0.68–1.37) | 61/4374 | 62/4334 | 0.98 (0.69–1.40) | ||

| History of diabetes | ||||||||

| Yes | 5/434 | 4/419 | 1.27 (0.34–4.73) | 0.79 | 5/427 | 4/426 | 1.26 (0.34–4.69) | 0.64 |

| No | 91/6674 | 93/6694 | 1.03 (0.77–1.38) | 92/6715 | 92/6653 | 0.97 (0.73–1.30) | ||

| Exercise ≥1 time/week | ||||||||

| Yes | 60/4295 | 54/4273 | 1.15 (0.79–1.66) | 0.38 | 59/4319 | 55/4249 | 1.05 (0.73–1.51) | 0.62 |

| No | 36/2635 | 43/2684 | 0.88 (0.57–1.38) | 38/2673 | 41/2646 | 0.90 (0.58–1.40) | ||

| Self-reported history of CVD | ||||||||

| Yes | 8/352 | 6/365 | 1.30 (0.45–3.74) | 0.61 | 7/373 | 7/344 | 0.97 (0.34–2.77) | 0.93 |

| No | 88/6760 | 91/6759 | 1.02 (0.76–1.36) | 90/6776 | 89/6743 | 0.99 (0.74–1.33) | ||

| Randomized to vitamin C or E | ||||||||

| Yes | 49/3564 | 48/3585 | 1.08 (0.72–1.60) | 0.77 | 49/3564 | 47/3548 | 1.03 (0.69–1.54) | 0.77 |

| No | 47/3548 | 49/3539 | 0.99 (0.66–1.48) | 48/3585 | 49/3539 | 0.95 (0.64–1.41) | ||

| Randomized to beta-carotene | ||||||||

| Yes | 48/3600 | 39/3573 | 1.27 (0.83–1.94) | 0.21 | 44/3589 | 43/3584 | 1.01 (0.66–1.54) | 0.91 |

| No | 48/3512 | 58/3551 | 0.87 (0.59–1.28) | 53/3560 | 53/3503 | 0.98 (0.67–1.43) | ||

AMD = age-related macular degeneration; CI = confidence interval; CVD = cardiovascular disease; HR = hazard ratio.

Baseline factors are defined as in Table 1.

Adjusted for vitamin C, beta-carotene, and multivitamin treatment assignment.

Adjusted for vitamin E, beta-carotene, and multivitamin treatment assignment.

Figure 3.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) comparing vitamin E alone, vitamin C alone, and vitamin E plus C groups with placebo (combined vitamin E and C placebo groups) in the Physicians’ Health Study II. Adjusted for age, Physicians’ Health Study cohort, and beta-carotene and multivitamin treatment assignment. The P value for interaction is based on a test of the null hypothesis of no difference in treatment effect across treatment combinations.

Vitamin C

For vitamin C, there were 97 cases of the primary endpoint in the active group and 96 cases in the placebo group (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.75–1.31; Table 2). The HR varied little over time (Figure 2), and the test of proportionality of the HR over time was not significant (P = 0.41). Similar nonsignificant findings were observed for the secondary endpoints of AMD with or without vision loss (179 cases in the vitamin C group versus 184 in the placebo group [HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.78–1.18]) and advanced AMD (39 cases in the vitamin C group versus 41 in the placebo group [HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.60–1.45]; Table 2). For all 3 endpoints, HRs decreased with increasing age group, but the P value for the test of interaction with age was significant only for AMD with or without vision loss (P = 0.049). There was no evidence that the lack of effect of vitamin C on the primary endpoint varied significantly in any subgroup of possible AMD risk factors (Table 3) or according to vitamin E or beta-carotene treatment assignment (Table 3; Figure 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, these data from a large population of apparently healthy men represent the longest treatment duration for vitamin E in the prevention of early AMD, and the first trial data to examine the individual effects of supplemental vitamin C. Results indicate that alternate day use of 400 IU of vitamin E for an average of 8 years had no appreciable effect on incident diagnosis of visually significant AMD. Similarly, daily supplementation with 500 mg of vitamin C for 8 years had no effect on risks of visually significant AMD. The 95% CIs excluded with reasonable certainty reductions greater than 22% for vitamin E, and reductions of >25% for vitamin C.

There have been 4 previous trials of supplemental vitamin E in AMD prevention. Three of these trials were comprised primarily of persons at usual risk for AMD. The Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene Study was a 2 × 2 factorial trial of vitamin E (50 mg daily) and beta-carotene (20 mg daily) conducted among >29 000 Finnish male smokers aged 50 to 69 years.9 Eye examinations conducted at the end of treatment (median, 6.1 years) among a small subsample of 941 participants aged ≥65 years identified 269 (29%) participants who showed signs of AMD based on review of fundus photographs. Most cases (239/269 [89%]) were classified as dry maculopathy with hard drusen and/or pigmentary changes. There was no beneficial effect of either vitamin E (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.81–1.59) or beta-carotene (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.74–1.47) on the prevalence of AMD in that trial. Similar null findings for vitamin E were reported in the Vitamin E, Cataract and Age-Related Maculopathy Trial conducted among 1193 men and women aged 55 to 80 years. In that trial, there was no benefit of 4 years of treatment with daily vitamin E (500 IU) on incidence of early (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.69–1.61) or late AMD (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 0.67–2.77), although the number of cases was small (early AMD, n = 69; late AMD, n = 7).10 Recent findings from the Women’s Health Study, which were based on 245 incident cases of visually significant AMD documented during 10 years of treatment and follow-up, indicated a nonsignificant 7% lower risk of AMD in the vitamin E group (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.72–1.19).11 Our findings are consistent with the lack of effect in these previous trials and extend these earlier findings by showing that, among persons with no prior diagnosis of AMD, long-term supplementation for up to 8 years with vitamin E and vitamin C, either alone or in combination, is unlikely to appreciably alter the risks of early AMD.

Comparison of our findings with the benefit observed in AREDS for combined treatment with zinc and antioxidants is limited by several factors. AREDS tested a higher risk population than that in PHS II, and the primary study endpoint in AREDS was progression to advanced AMD (choroidal neovascularization or central geographic atrophy). In PHS II, the primary endpoint was visually significant AMD, which represents, on average, a less severe stage of disease development than the advanced AMD endpoint in AREDS. However, when we examined the more severe cases of AMD in our population, we found no evidence that either vitamin E (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.73–1.74) or vitamin C (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.60–1.45) reduced the risk of advanced AMD (defined as the occurrence of exudative neovascular disease or geographic atrophy). Nor was there evidence of benefit for combined treatment with active vitamin E and active vitamin C (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.60–1.93). Nonetheless, the number of advanced cases in our study was small (n = 80), and the 95% CIs for vitamin E and vitamin C treatment, alone and in combination, were compatible with the risk reduction observed in AREDS for combined treatment with antioxidants and zinc.

It is important to consider several possible limitations of our study, especially in light of the findings of no significant effect. The dose of vitamin C in PHS II was the same as that tested in AREDS. The dose of vitamin E (400 IU taken every other day) was lower than the dose tested in AREDS (400 IU daily), but was considerably greater than doses associated with a possible benefit in AMD in observational studies.20 Thus, it seems unlikely that the observed lack of benefit was due to inadequate dose of vitamin E or vitamin C. Poor compliance also seems an unlikely explanation. Compliance with study medication remained high (70%–72%) in PHS II at the end of follow-up (mean of 8 years), and was similar to that reported in AREDS at 5 years of follow-up (71% reported taking at least three-fourths of the study capsules at 5 years). The findings are also unlikely due to an inadequate duration of treatment. At 8 years of treatment and follow-up, PHS II was 1 to 2 years longer than AREDS, which observed a benefit during an average of 6.3 years of treatment and follow-up. However, it is possible that our findings reflect the nutritional status of our study population. The PHS II population is generally well-nourished and thus these findings may not apply to less well-nourished populations. Several aspects of our methodology also deserve consideration. Identification of AMD cases was based on participant reports, and thus some degree of underascertainment of AMD is plausible. Such underascertainment would likely reduce study power, but is not associated with bias in randomized comparisons. Random misclassification of reported AMD, which would shift the relative risk estimate toward the null, was reduced by the use of medical records to confirm the participant reports. Nonrandom or differential misclassification was unlikely since medical records were reviewed by an investigator (W.G.C.) masked to treatment assignment, and study participants and treating ophthalmologists and optometrists were similarly unaware of treatment assignment. Finally, the equal distribution of baseline characteristics between the treated and placebo groups in this large, randomized trial indicates that confounding by measured factors is unlikely, and provides reassurance that other potential confounders, which were either unmeasured or unknown, were also likely to be evenly distributed between the 2 treatment groups.

In summary, these randomized trial data from a large population of generally well-nourished men indicate that supplementation for 8 years with high-dose vitamin E and vitamin C, alone and in combination, is unlikely to have an important effect on the incidence of early AMD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants CA 97193 (which included funding from the National Eye Institute and the National Institute on Aging), CA 34944, CA 40360, HL 26490, and HL 34595 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD), and an investigator-initiated grant from BASF Corporation (Florham Park, NJ). Study agents and packaging were provided by Wyeth Pharmaceuticals (Madison, NJ), BASF Corporation, and DSM Nutritional Products Inc (formerly Roche Vitamins; Parsippany, NJ). Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, BASF Corporation, and DSM Nutritional Products, Inc, had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure(s):

The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any of the materials discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Congdon NG, Friedman DS, Lietman T. Important causes of visual impairment in the world today. JAMA. 2003;290:2057–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:564–72. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–36. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein R, Klein BE, Tomany SC, et al. Ten-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1767–79. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A simplified severity scale for age-related macular degeneration: AREDS report no. 18. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1570–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.11.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snodderly DM. Evidence for protection against age-related macular degeneration by carotenoids and antioxidant vitamins. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62(Suppl):1448S–61S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1448S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman H, Chew E. Nutritional supplementation in age-related macular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:220–3. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32814a586b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seddon JM. Multivitamin-multimineral supplements and eye disease: age-related macular degeneration and cataract. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:304S–7S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.304S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teikari JM, Laatikainen L, Virtamo J, et al. Six-year supplementation with alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene and age-related maculopathy. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1998;76:224–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor HR, Tikellis G, Robman LD, et al. Vitamin E supplementation and macular degeneration: randomised controlled trial. [January 7, 2012];BMJ. 2002 325:11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7354.11. [report online]. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/highwire/filestream/366423/field_highwire_article_pdf/0.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christen WG, Glynn RJ, Chew EY, Buring JE. Vitamin E and age-related macular degeneration in a randomized trial of women. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1163–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christen WG, Manson JE, Glynn RJ, et al. Beta carotene supplementation and age-related maculopathy in a randomized trial of US physicians. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:333–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christen WG, Gaziano JM, Hennekens CH. Design of Physicians’ Health Study II—a randomized trial of beta-carotene, vitamins E and C, and multivitamins, in prevention of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and eye disease, and review of results of completed trials. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:125–34. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaziano JM, Glynn RJ, Christen WG, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of prostate and total cancer in men: the Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:52–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2123–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christen WG, Glynn RJ, Sesso HD, et al. Age-related cataract in a randomized trial of vitamins E and C in men. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1397–405. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Health Study Research Group. Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:129–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907203210301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Manson JE, et al. Lack of effect of long-term supplementation with beta carotene on the incidence of malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1145–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christen WG, Glynn RJ, Ajani UA, et al. Age-related maculopathy in a randomized trial of low-dose aspirin among US physicians. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1143–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.8.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong EW, Wong TY, Kreis AJ, et al. Dietary antioxidants and primary prevention of age related macular degeneration: systematic review and meta-analysis. [January 7, 2012];BMJ. 2007 335:755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39350.500428.47. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/highwire/filestream/391017/field_highwire_article_pdf/0.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]