Abstract

Background

Standard treatment of osteosarcoma includes cisplatin and high-dose methotrexate (HDMTX); both agents exert significant toxicity, and HDMTX requires complex pharmacokinetic monitoring and leucovorin rescue. In our previous OS91 trial, treatment of localized disease with carboplatin, ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and HDMTX yielded outcomes comparable to those of cisplatin-based regimens and caused less toxicity. To build on our experience, we conducted a multi-institutional trial (OS99) that evaluated the efficacy of carboplatin, ifosfamide, and doxorubicin without HDMTX in newly diagnosed, localized, resectable osteosarcoma.

Methods

Treatment comprised 12 cycles of chemotherapy over 35 weeks: 3 cycles of carboplatin (dose targeted to AUC 8 mg/ml×min on day 1) and ifosfamide (2.65 g/m2 daily X3 days) and one cycle of doxorubicin (25 mg/m2 daily X3 days) before resection, followed by 2 additional cycles of carboplatin/ifosfamide and 3 cycles each of doxorubicin (25 mg/m2 daily X2 days) combined with ifosfamide or carboplatin.

Results

72 eligible patients (median age, 13.4 years) were enrolled between May 1999 and May 2006. Forty of the 66 (60.6%) evaluable patients had good histologic responses (> 90% tumor necrosis) to preoperative chemotherapy. The estimated 5-year EFS was 66.7% ± 7.0% for OS99, compared to 66.0% ± 6.8% for OS91 (P=0.98). Estimated 5-year survival was 78.9% ± 6.3% for OS99 and 74.5% ± 6.3% for OS91 (P=0.40).

Conclusion

The OS99 regimen produces outcomes comparable to those of cisplatin- or HDMTX-containing regimens. This therapy offers a good alternative for patients—particularly those with intolerance of HDMTX—and for institutions that cannot provide MTX pharmacokinetic monitoring.

Keywords: osteosarcoma, treatment, methotrexate, renal failure, encephalopathy, ifosfamide, carboplatin, cisplatin, outcome

INTRODUCTION

Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone malignancy in children and young adolescents. The majority of patients present with localized disease,1,2 and 60% to 70% of these patients survive with contemporary treatment regimens.3–6 Therapy consists of aggressive surgery and multi-agent chemotherapy, which usually includes doxorubicin, cisplatin, and high-dose methotrexate (HDMTX). Although cisplatin and HDMTX are very effective, they can cause significant toxicities, including nephrotoxicity, otoxicity, mucositis, hepatotoxicity, pulmonary toxicity, and neurotoxicity. Some MTX toxicities, such as mucositis and nephrotoxicity, are associated with delayed MTX clearance, which can be affected by renal function and other nephrotoxic drugs such as cisplatin.7

Our previous osteosarcoma trial (OS91) evaluated the combination of carboplatin and ifosfamide given as up-front window therapy, plus doxorubicin and HDMTX.8 Although single-agent carboplatin has shown very limited activity against previously untreated metastatic osteosarcoma,9 carboplatin combined with ifosfamide showed substantial antitumor activity in OS91.8 This activity was not attributable to ifosfamide alone, because the rate of early disease progression was significantly lower than that seen with ifosfamide alone.8,10 For localized osteosarcoma, OS91 yielded outcomes comparable to those of cisplatin-based regimens and caused less toxicity.8

The necessity for HDMTX in the context of multi-agent chemotherapy for osteosarcoma has been questioned, and some postulate that HDMTX toxicity interferes with the dose-intensive delivery of other active agents.7,11–13 In addition, HDMTX administration requires rigorous pharmacokinetic monitoring and rescue with leucovorin dose-adjusted to MTX levels.7,14 The expertise and technology required for this monitoring is not available at some institutions. Therefore, an effective chemotherapy regimen that does not contain HDMTX would be of benefit, especially for patients with renal dysfunction.

We wished to investigate whether the complexity and potential toxicity of HDMTX administration can be avoided. Thus, the OS99 trial assessed the use of carboplatin, ifosfamide, and doxorubicin without HDMTX for the treatment of localized, resectable osteosarcoma. In addition, since minimal resection of tumor-free bone may improve prosthesis fixation and help preserve growth potential in children, OS99 also explored whether resection of the primary tumor with a 3-cm rather than a 5-cm (used in OS91) bone margin can be performed without increasing the rate of local recurrence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients were enrolled at 3 centers: St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN; Luis Calvo McKenna Hospital, Santiago, Chile; and Washington University Medical School, St. Louis, MO. Eligibility requirements comprised: age <25 years; previously untreated, non-metastatic, histologically proven, high-grade osteosarcoma or malignant fibrous histiocytoma of bone (patients with parosteal or periosteal osteosarcoma were not eligible) resectable by either limb-sparing surgery or amputation; total serum bilirubin < 1.5 × normal; serum creatinine < 2 × normal; no evidence of cardiac rhythm disturbance or cardiomyopathy; and signed informed consent of the patient, parent, or guardian, as appropriate. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions.

Chemotherapy protocol

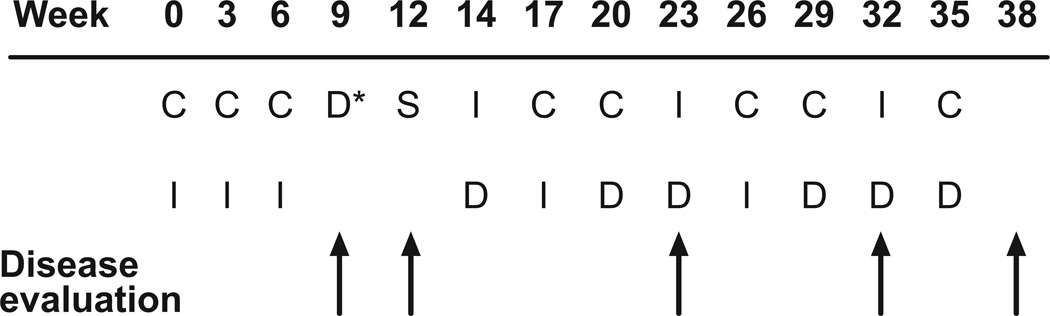

The protocol consisted of 12 cycles of chemotherapy (1 cycle every 3 weeks over 35 weeks; Fig 1). Preoperative chemotherapy comprised 3 cycles of carboplatin (dose targeted to achieve an area under the concentration-time curve [AUC] of 8 mg/ml × min on day 1) and ifosfamide (2.65 g/m2 daily on days 1–3) and one cycle of doxorubicin (25 mg/m2 daily for 3 days). Tumor resection at week 12 was followed by 2 additional cycles of carboplatin/ifosfamide given as described above and 3 cycles each of ifosfamide (2.65 g/m2 daily on days 1–3) and doxorubicin (25 mg/m2 daily on days 1 and 2) and of carboplatin (dose targeted to an AUC of 8 mg/ml×min on day 1) and doxorubicin (25 mg/m2 daily on days 1 and 2). Carboplatin dosage was based on glomerular filtration rate (GFR) as measured by technetium 99m-DTPA clearance or 24-hour urine creatinine clearance to ensure consistent systemic exposure among patients.15 The carboplatin dose (infused over 1 h) was calculated as follows: dose (mg/m2) =8×[(0.93×GFR in ml/min/m2)+15].16,17 Ifosfamide was infused over 15–30 minutes and doxorubicin over 1 hour. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor or granulocyte monocyte-colony stimulating factor was administered after each cycle. The total cumulative dose of doxorubicin was 375 mg/m2 and that of ifosfamide 63.6 g/m2.

Fig 1.

Treatment schema for OS99. C = carboplatin (dose targeted to an area under the concentration-time curve [AUC] of 8 mg/ml × min on day 1); I = ifosfamide (2.65 g/m2 daily on days 1–3); D* = doxorubicin (25 mg/m2 daily for 3 days); S = definitive surgery; D = doxorubicin (25 mg/m2 daily on days 1 and 2).

Patient Evaluation

Standard laboratory tests to assess toxicity, including complete blood counts, serum chemistries, and urinalysis, were obtained at baseline and at regular intervals until at least 4 years after completion of therapy. The initial staging work-up consisted of plain radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging18,19 of the primary tumor; technetium 99 methyldiphosphonate (99Tc-MDP) nuclear bone scanning; and computed tomography (CT) of the chest. These studies were repeated after 3 cycles of carboplatin/ifosfamide (week 9), before definitive surgery (week 12), and (without MRI) at the end of therapy. Chest CT was performed during therapy at weeks 23 and 32. After completion of treatment, patients were monitored by plain radiography or CT of the chest and by radiography of the primary tumor site every 2 months and by bone scans every 6 months for the first year. Subsequently, patients underwent radiography or CT of the chest every 3–6 months and radiography of the primary tumor site every 6–12 months for at least 4 years after completion of therapy.

Evaluation of Response

Clinical and radiologic responses were assessed at weeks 9 and 12 (Fig 1). Patients were considered to have had a response if they became pain-free without the use of analgesics and MRI showed either decreased (≥50% reduction in the product of the 3 perpendicular tumor diameters) or stable (<50% reduction or <25% increase in the product of the 3 perpendicular tumor diameters) tumor volume. Patients with persistent pain and stable tumor volume on MRI were considered to have stable disease. Patients with significantly increased tumor size (≥25% increase in the product of the perpendicular diameters) by MRI or with new lesions were considered to have progressive disease. The four-grade system of Huvos20,21 was used for histologic assessment of the tumor response at the time of resection. Central review of tumor histology and tumor histologic response was performed at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Evaluation of Toxicity

Toxicity was assessed by using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 2.0). Patients underwent echocardiography, electrocardiography, pure-tone audiometry, and GFR assessment before the start of treatment and serially thereafter.

Statistical Methods

OS99 was designed as a historical control phase II study to compare the histologic response rate induced by two preoperative regimens: 3 cycles of carboplatin and ifosfamide plus 1 cycle of doxorubicin in patients treated on OS99 and 3 cycles of carboplatin and ifosfamide in patients treated on OS91.22,23 Patients with localized resectable osteosarcoma treated on OS91 served as the historical control group. The study included an interim analysis for futility after half of the patients were evaluated. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare histologic response rate between OS91 and OS99 and confidence intervals of response rate were calculated using Blyth-Still-Casella’s method. The study also compared the event-free survival (EFS) and survival of patients treated without HDMTX (OS99) to that of patients treated with HDMTX (OS91). EFS and survival were not the primary endpoints of OS99; thus, the study was not designed to detect a pre-specified difference in EFS or survival between OS99 and OS91. Survival was defined as the time between study enrollment and last follow-up or death from any cause. EFS was defined as the time between study enrollment and disease progression or relapse, diagnosis of a second malignancy, death from any cause, or last follow-up. Survival and EFS distributions were estimated by using the method of Kaplan and Meier.24 The log rank test was used to compare survival and EFS distributions.

The effect of reduced surgical bone margin was assessed by comparing the cumulative incidence of local treatment failure (local disease progression or recurrence)25 in OS99 and OS91 by using Gray’s test.26 Competing events were distant failure, second malignancy, or death prior to local failure. Patients with simultaneous local and distant treatment failure were considered to have local failure for this analysis.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Between May 1999 and May 2006, 72 eligible patients were enrolled on OS99 (Table 1). The median age was 13.4 years (range, 3.2 – 23.0 years). Forty-one patients (57%) were males and 33 (46%) were white. The most common primary tumor site was the femur (n=46; 64%). Our previous OS91 protocol enrolled 47 patients with localized, resectable osteosarcoma;8 median age was 13.6 years (range, 5.9 – 19.4 years). Patients treated on OS99 and OS91 were similar with respect to age (p=0.53), gender (p=0.35), and primary tumor site (extremity vs. other; p=0.38). Data on tumor size for the OS91 patients were not available for comparison.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 72 Patients with Localized Resectable Osteosarcoma

| Characteristic | N |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median: 13.4 years | |

| Range: 3.2 – 23.0 years | |

| Sex | 41 |

| Male | |

| Female | 31 |

| Race | 33 |

| White | |

| Hispanic | 27 |

| Black | 12 |

| Primary Tumor Site | 46 |

| Femur | |

| Tibia | 18 |

| Humerus | 3 |

| Fibula | 2 |

| Ulna | 1 |

| Rib | 1 |

| Maxilla | 1 |

| Pathologic Fracture | 6 |

| Anatomic Tumor Extent | |

| Extracompartmental | 68 |

| Intracompartmental | 4 |

Histologic Response

Comparison of the histologic response rate on OS99 at week 12 (after 3 cycles of carboplatin and ifosfamide and one cycle of doxorubicin) with that on OS91 at week 9 (after 3 cycles of carboplatin and ifosfamide), included patients on OS99 who received 4 cycles of chemotherapy before tumor resection (n=63) plus three patients who had local disease progression before week 12 and were considered non-responders (total n=66). Six patients were considered inevaluable for histologic response: one died of bacterial sepsis after 3 cycles of preoperative chemotherapy and 5 had delayed tumor resection (after week 12). Four of these 5 patients had 5 cycles of chemotherapy before surgery due to delayed readiness of the endoprostheses (n=3) or surgery scheduling problems (n=1). Tumor resection in the fifth patient was delayed until after completion of chemotherapy because of underlying insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, which may increase the risk of delayed wound healing and infection. The histologic grade of these 5 patients’ resected tumors was IV in 2 patients, III in 2 patients, and II in 1 patient.

Forty patients who underwent tumor resection at week 12 had a histologic response (> 90% tumor necrosis): grade III (n=29) or IV (n=11). Therefore, the histologic response rate to preoperative chemotherapy (3 cycles of carboplatin and ifosfamide and 1 cycle of doxorubicin) was 61% (40/66; 95% CI, 48% – 72%). In comparison, on OS91 the histologic response rate to preoperative chemotherapy (3 cycles of carboplatin and ifosfamide) in patients with localized, resectable disease was 51% (95% CI, 36% – 66%) (p=0.34).

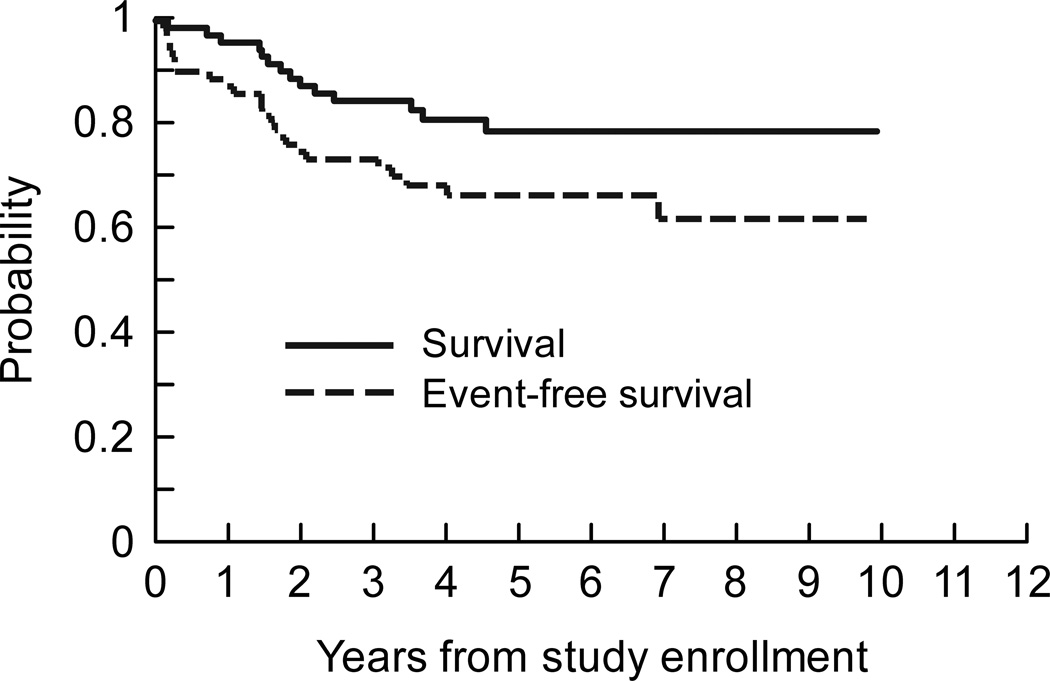

Survival

The median duration of follow-up after study enrollment was 5.1 years (range, 2.2 – 9.9 years) for the 58 surviving patients treated on OS99. All survivors were seen or contacted within one year of the analysis. First events included disease relapse or progression (n=22), second malignancy (acute myelogenous leukemia; n=1), and death from sepsis (n=1). Twelve of the 22 patients with relapsed or progressive disease had died at the time of analysis. Five-year estimates of EFS and survival were 66.7% ± 7.0% and 78.9% ± 6.3%, respectively (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Survival and EFS distributions for 72 patients with localized resectable osteosarcoma treated on OS99.

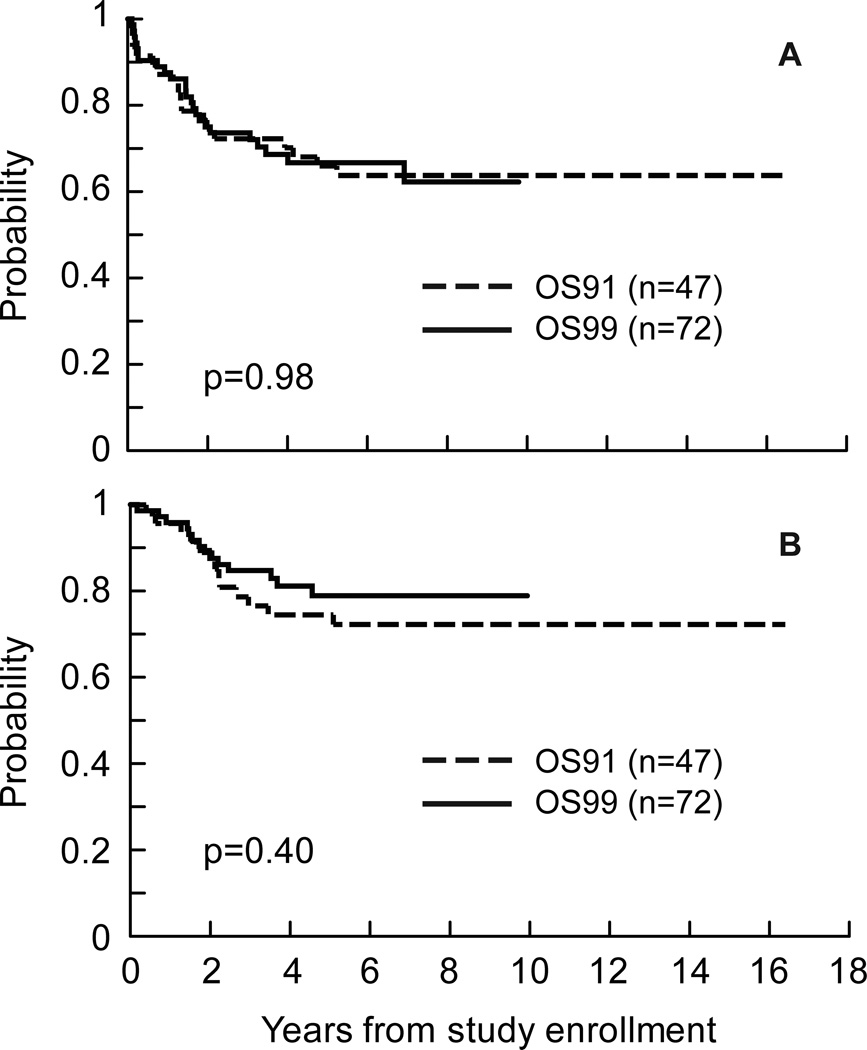

Thirty-four of the 47 patients with localized, resectable osteosarcoma treated on OS91 survived. The 34 survivors had a median follow-up of 13.1 years (range, 8.2 – 16.4 years), and 77% had been seen or contacted within 2 years of the analysis.

There was no evidence of a difference between OS91 and OS99 in EFS or survival distributions (Fig 3). Five-year estimates of EFS were 66.7% ± 7.0% for OS99 and 66.0% ± 6.8% for OS91(p=0.98). Five-year estimates of survival were 78.9% ± 6.3% for OS99 and 74.5% ± 6.3% for OS91(p=0.40).

Fig 3.

Event-free survival (A) and survival (B) distributions for patients with localized resectable osteosarcoma by protocol.

Local Failure

Of the 67 patients with extremity tumors who underwent surgery, 59 (88%) had limb-salvage procedures and 8 (12%) had amputation. The other 3 patients with extremity tumors had local disease progression (n=2) or died (n=1) before surgery. In the 57 patients who underwent limb-salvage surgery and on whom data was available, the median bone resection margin was 4 cm (range, 1 – 15 cm) and at least 3 cm in 43 (75%) patients. The closest soft tissue margin in the majority of patients was 1 – 2 mm.

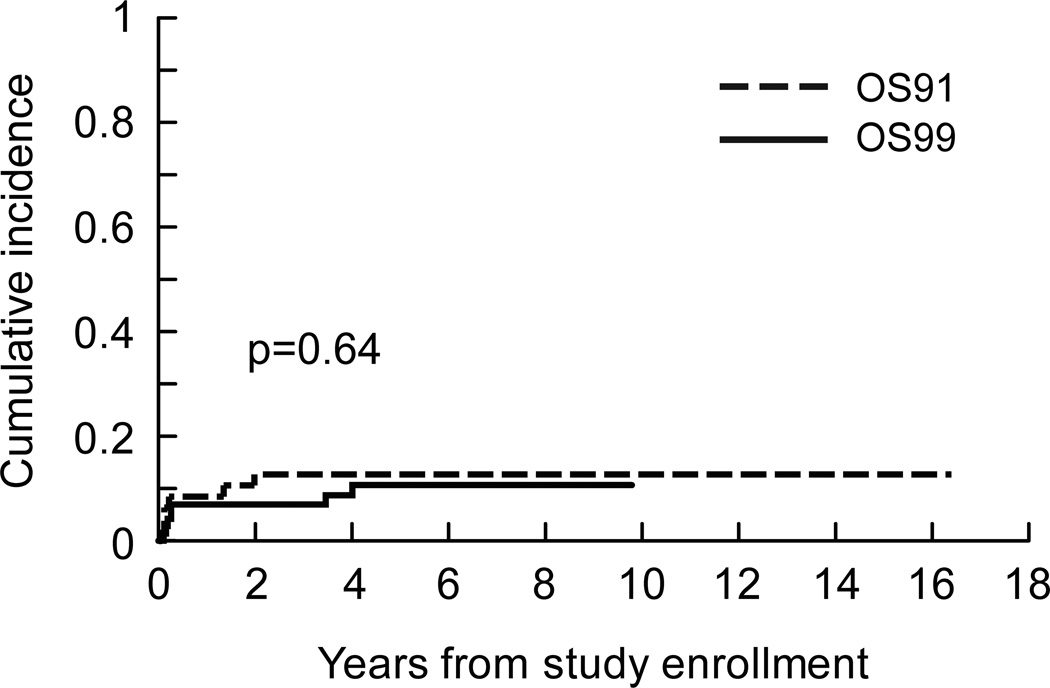

There were 7 local failures as first events among the 72 OS99 patients. Five of these were disease progression; 3 patients had local progression shown by imaging before surgery and two had local progression suggested by imaging and confirmed by histologic analysis after resection. There were only 2 (3%) local recurrences: one was associated with a distant recurrence 3.5 years after diagnosis, and another occurred 4 years after diagnosis. The bone resection margin in these 2 cases was 3 cm and 5 cm. The cumulative incidence of local failure in OS99 and OS91 was estimated from the data on first events. There was no evidence that local control differed by protocol (Fig 4). Five-year estimates of the cumulative incidence of local failure were 10.6% ± 3.9% for OS99 and 12.8 ± 4.9% for OS91 (p=0.64).

Fig 4.

Cumulative incidence of local failure for patients with localized resectable osteosarcoma by protocol.

Toxicity

Protocol chemotherapy was well tolerated and delivered primarily (65% of cycles) in the outpatient setting. Table 2 summarizes the grade 3 or 4 toxicities observed during the 782 cycles of chemotherapy. The most common toxicity was myelosuppression. One patient died of bacterial sepsis after the third cycle of chemotherapy. Another, who had complete remission of osteosarcoma, had a diagnosis of acute myelogenous leukemia M5 with the t(9;11) 7 months after completion of treatment and died 2 days after the diagnosis. There was no grade 3 or 4 serum creatinine toxicity; grade 1 or 2 serum creatinine elevation was observed in 6 patients. There was no grade 3 or 4 ototoxicity; grade 1 or 2 hearing loss was observed in 3 patients. Grade 3 or 4 stomatitis/pharyngitis occurred in 3 patients. No patients had grade 4 hepatic toxicity; 2 patients had grade 3 hyperbilirubinemia and 6 had a grade 3 increase in hepatic transaminase activity.

Table 2.

Grade 3 and 4 Toxicities* Observed in More than 1% of the 782 Chemotherapy Cycles According to Grade

| Toxicity | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cycles (% of total cycles) |

No. of patients |

No. of cycles (% of total cycles) |

No. of patients |

|

| Hematologic | ||||

| Neutropenia/granulocytopenia | 127 (16) | 2 | 568 (73) | 70 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 452 (58) | 9 | 183 (23) | 63 |

| Low hemoglobin concentration | 454 (58) | 37 | 67 (9) | 34 |

| Lymphopenia | 22 (3) | 2 | - | - |

| Febrile neutropenia | 130 (17) | 48 | 8 (1) | 6 |

| Renal | ||||

| Hypophosphatemia | 94 (12) | 36 | 9 (1) | 5 |

| Hypokalemia | 73 (9) | 24 | 23 (3) | 13 |

| Urinary electrolyte wasting | 20 (3) | 9 | - | - |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Vomiting | 70 (9) | 35 | 1 (<1) | 1 |

| Nausea | 54 (7) | 32 | - | - |

| Anorexia | 12 (2) | 6 | 2 (<1) | 2 |

| Infection (documented) | ||||

| Non–wound infection# | 43 (5) | 24 | 6 (1) | 5 |

| Wound infection | 15 (2) | 13 | 2 (<1) | 2 |

| Metabolic | ||||

| Hyponatremia | 10 (1) | 10 | 1 (<1) | 1 |

| Hypocalcemia | 8 (1) | 7 | 2 (<1) | 2 |

| Hypotension | 16 (2) | 12 | 3 (<1) | 2 |

NCI Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0

One additional patient had grade 5 infection with neutropenia and died of bacterial sepsis.

Ten patients did not receive all planned therapy due to progressive or relapsed disease (n=7), death from toxicity (n=1), refusal of treatment (n=1), or a decision to receive alternative therapy (n=1). Of the remaining 62 patients, 57 (92%) received all 12 chemotherapy cycles, 4 received 11 cycles, and 1 received 10 cycles.

DISCUSSION

This trial demonstrated that administration of carboplatin, ifosfamide, and doxorubicin produces EFS and survival outcomes comparable to those of HDMTX- or cisplatin-containing regimens in patients with localized, resectable osteosarcoma.3–5,8,27–29 Protocol chemotherapy was well tolerated and administered mainly in the outpatient setting. This regimen eliminates the need for MTX pharmacokinetic monitoring and avoids the toxicities associated with HDMTX and cisplatin. OS99 offers a good alternative for patients with localized, resectable disease—particularly those with intolerance of HDMTX—and for institutions that cannot provide MTX monitoring.

The histologic response rate to preoperative chemotherapy in our study (3 cycles of carboplatin and ifosfamide and 1 cycle of doxorubicin; 12 weeks) was 61%. In comparison, the histologic response rate was 43% to preoperative cisplatin, doxorubicin and HDMTX (10 weeks) and 48% to preoperative ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and HDMTX (10 weeks) in the Intergroup osteosarcoma trial INT0133.3 That trial defined histologic response as residual viable tumor less than 5% at the time of definitive surgery,30,31 whereas the threshold in OS99 was 10%. Although single-agent carboplatin did not show significant activity against newly diagnosed metastatic osteosarcoma, it showed substantial activity against osteosarcoma when combined with ifosfamide in 2 consecutive trials at St. Jude (OS91 and OS99).

The role of HDMTX has been investigated in patients with non-metastatic osteosarcoma. The first European Osteosarcoma Intergroup (EOI) study, which randomly assigned patients to 18 weeks of cisplatin and doxorubicin vs. cisplatin, doxorubicin, and HDMTX (8 g/m2), found no greater likelihood of disease-free survival or survival in the HDMTX arm.11 The subsequent EOI study also found no difference in progression-free survival or survival between patients randomly assigned to cisplatin and doxorubicin for 18 weeks or to a multiagent regimen including HDMTX (8–12 g/m2) for 44 weeks.12 However, the cisplatin-doxorubicin regimen appears to produce survival estimates (55% at 5 years) inferior to those of cisplatin, doxorubicin, and HDMTX (12 g/m2) (71% at 6 years).3,12,28 A third study that used ifosfamide, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and etoposide without MTX showed a 3-year progression-free survival of 70%.13 These data suggest that osteosarcoma can be treated without HDMTX but that a two-drug chemotherapy regimen is not sufficient.

Carboplatin, ifosfamide, and doxorubicin given without HDMTX on OS99 resulted in 5-year EFS and survival estimates of 66.7% ± 7.0% and 78.9% ± 6.3%, respectively, for patients with localized resectable osteosarcoma. These results are comparable to those of regimens containing cisplatin and HDMTX,3,28 including the most widely accepted chemotherapy regimen for localized osteosarcoma (cisplatin, doxorubicin, and HDMTX) (6-year EFS and survival estimates, 64% and 71%, respectively).28 Outcomes in our OS91 trial, which used ifosfamide and carboplatin rather than cisplatin, were comparable to those of cisplatin-based regimens and reduced the risk of ototoxicity.8 Elimination of HDMTX in OS99 did not negatively affect outcome. It is important to note that all but two of our patients had extremity tumors, and such patients have a more favorable prognosis than patients with axial tumors who were included in very limited numbers in some of the other studies.3,28 OS99 avoids the toxicity of HDMTX and uses carboplatin which causes less nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity than cisplatin; however, it includes ifosfamide, which may cause urinary electrolyte wasting, hemorrhagic cystitis, and infertility.8,32

In Intergroup osteosarcoma trial INT0133,3 677 patients with localized osteosarcoma were randomly assigned to receive cisplatin, doxorubicin, and HDMTX with or without ifosfamide, and with or without muramyl tripeptide (MTP, a synthetic lipophilic glycopeptide that activates monocyte and macrophage antitumor activity). Although an initial analysis did not show improvement of EFS with the addition of MTP,3 an updated analysis concluded that 6-year survival had improved from 70% to 78%.28 MTP has been approved in Europe in combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed nonmetastatic osteosarcoma. Notably, the addition of ifosfamide to cisplatin, doxorubicin, and HDMTX in INT0133 did not enhance EFS or overall survival.3,28 The most recent Children’s Oncology Group (COG) pilot studies showed a 2-year EFS of 69% for patients with non-metastatic osteosarcoma without significant benefit from intensification of the doxorubicin dose (cumulative dose, 600 mg/m2) or addition of high-dose ifosfamide (14 g/m2/cycle) and etoposide for patients with less than 98% tumor necrosis at surgery.27 These trials suggest that intensification of chemotherapy and addition of new cytotoxic agents does not improve patient outcome, underscoring the need for novel treatment strategies. A better understanding of the biology of osteosarcoma is critical to identify potential targets for therapy.

Most of our patients underwent limb-salvage surgery for local control. The baseline MRI was used to determine the extent of tumor resection unless there was evidence of disease progression, in which case the most recent MRI was used. The use of a 3-cm bone resection margin in OS99 did not appear to adversely affect the rate of local control. This finding may be attributable to improved surgical and imaging techniques, especially as modern MRI allows better delineation of the extent of the tumor and its relation to the neurovascular bundle. Our rate of local recurrence (3%) was similar to the 2% to 10% rates cited by others.2,29,33–35 A smaller bone resection margin improves the likelihood of preserving the growth plate in growing children and provides a greater area for fixation of the endoprosthesis.

Although our study is a Phase II study with a limited number of patients, it provides evidence that localized osteosarcoma can be treated with carboplatin, ifosfamide, and doxorubicin as used in OS99 without compromising EFS or survival. These results have important implications not only for avoiding the toxicity of HDMTX but also for reducing the cost and treatment complexity associated with HDMTX. While minimizing toxicity and cost is important, improvement in outcome requires further understanding of tumor biology and development of rational targeted therapies.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Berlex Laboratories (Seattle, Washington) for providing GM-CSF for Chilean patients and to Wright Medical Company (Arlington, Tennessee) for providing prostheses at a reduced price for Chilean patients. We acknowledge the valuable contributions of Charles B. Pratt, MD (deceased), Fredric A. Hoffer, MD, Carlos Rodriguez-Galindo, MD, Gaston K. Rivera, MD, Karen Wodowski, PNP, Vickie Given, RN, Dana Hawkins, RN, BSN, CCRC, Valerie McPherson, CCRP, and Debbie Poe, CCRP (St. Jude), and of Myriam Campbell, MD, Juan Jose Latorre, MD, Jesus Ortega, MD, and Emma Concha, MD (Chile). We thank Sharon Naron for editorial assistance.

Supported by Cancer Center Support Grant CA21765 and grant CA23099 from the National Institutes of Health and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 29-June 2, 2009.

Michael D. Neel, MD is a consultant for Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, TN. The remaining authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meyers PA, Heller G, Healey JH, et al. Osteogenic sarcoma with clinically detectable metastasis at initial presentation. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:449–453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bielack SS, Kempf-Bielack B, Delling G, et al. Prognostic factors in high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities or trunk: an analysis of 1,702 patients treated on neoadjuvant cooperative osteosarcoma study group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:776–790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo M, et al. Osteosarcoma: a randomized, prospective trial of the addition of ifosfamide and/or muramyl tripeptide to cisplatin, doxorubicin, and high-dose methotrexate. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2004–2011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs N, Bielack SS, Epler D, et al. Long-term results of the co-operative German-Austrian-Swiss osteosarcoma study group's protocol COSS-86 of intensive multidrug chemotherapy and surgery for osteosarcoma of the limbs. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:893–899. doi: 10.1023/a:1008391103132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goorin AM, Schwartzentruber DJ, Devidas M, et al. Presurgical chemotherapy compared with immediate surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy for nonmetastatic osteosarcoma: Pediatric Oncology Group Study POG-8651. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1574–1580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacci G, Briccoli A, Ferrari S, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma of the extremity: long-term results of the Rizzoli's 4th protocol. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2030–2039. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crews KR, Liu T, Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al. High-dose methotrexate pharmacokinetics and outcome of children and young adults with osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2004;100:1724–1733. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer WH, Pratt CB, Poquette CA, et al. Carboplatin/ifosfamide window therapy for osteosarcoma: results of the St Jude Children's Research Hospital OS-91 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:171–182. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson WS, Harris MB, Goorin AM, et al. Presurgical window of carboplatin and surgery and multidrug chemotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed metastatic or unresectable osteosarcoma: Pediatric Oncology Group Trial. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daw NC, Billups CA, Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al. Metastatic osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2006;106:403–412. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bramwell VH, Burgers M, Sneath R, et al. A comparison of two short intensive adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in operable osteosarcoma of limbs in children and young adults: the first study of the European Osteosarcoma Intergroup. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1579–1591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.10.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souhami RL, Craft AW, Van der Eijken JW, et al. Randomised trial of two regimens of chemotherapy in operable osteosarcoma: a study of the European Osteosarcoma Intergroup. Lancet. 1997;350:911–917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epelman S, Seibel N, Melaragno R, et al. Treatment of newly diagnosed high grade osteosarcoma (OS) with ifosfamide (IFOS), adriamycin (ADR) and cisplatin (CDP) without high dose methotrexate. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27:226. [abstract O-61] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoller RG, Hande KR, Jacobs SA, Rosenberg SA, Chabner BA. Use of plasma pharmacokinetics to predict and prevent methotrexate toxicity. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:630–634. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197709222971203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodman JH, Maneval DC, Magill HL, Sunderland M. Measurement of Tc-99m DTPA serum clearance for estimating glomerular filtration rate in children with cancer. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13:10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marina NM, Rodman J, Shema SJ, et al. Phase I study of escalating targeted doses of carboplatin combined with ifosfamide and etoposide in children with relapsed solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:554–560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marina NM, Rodman JH, Murry DJ, et al. Phase I study of escalating targeted doses of carboplatin combined with ifosfamide and etoposide in treatment of newly diagnosed pediatric solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:544–548. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.7.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddick WE, Wang S, Xiong X, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of regional contrast access as an additional prognostic factor in pediatric osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2001;91:2230–2237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddick WE, Bhargava R, Taylor JS, Meyer WH, Fletcher BD. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging evaluation of osteosarcoma response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;5:689–694. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huvos AG, Rosen G, Marcove RC. Primary osteogenic sarcoma: pathologic aspects in 20 patients after treatment with chemotherapy en bloc resection, and prosthetic bone replacement. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1977;101:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen G, Caparros B, Huvos AG, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy for osteogenic sarcoma: selection of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy based on the response of the primary tumor to preoperative chemotherapy. Cancer. 1982;49:1221–1230. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820315)49:6<1221::aid-cncr2820490625>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makuch RW, Simon RM. Sample size considerations for non-randomized comparative studies. J Chronic Dis. 1980;33:175–181. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(80)90017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gehan EA. Design of controlled clinical trials: use of historical controls. Cancer Treat Rep. 1982;66:1089–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray RJ. A class of k-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz CL, Wexler LH, Devidas M, et al. P9754 therapeutic intensification in non-metastatic osteosarcoma: A COG trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004 Jul 15;:802s. [abstract 8514] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Krailo MD, et al. Osteosarcoma: the addition of muramyl tripeptide to chemotherapy improves overall survival--a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:633–638. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.14.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrari S, Smeland S, Mercuri M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with high-dose Ifosfamide, high-dose methotrexate, cisplatin, and doxorubicin for patients with localized osteosarcoma of the extremity: a joint study by the Italian and Scandinavian Sarcoma Groups. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8845–8852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyers PA, Heller G, Healey J, et al. Chemotherapy for nonmetastatic osteogenic sarcoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:5–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Provisor AJ, Ettinger LJ, Nachman JB, et al. Treatment of nonmetastatic osteosarcoma of the extremity with preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy: a report from the Children's Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:76–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janeway KA, Grier HE. Sequelae of osteosarcoma medical therapy: a review of rare acute toxicities and late effects. Lancet Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bacci G, Ferrari S, Bertoni F, et al. Long-term outcome for patients with nonmetastatic osteosarcoma of the extremity treated at the istituto ortopedico rizzoli according to the istituto ortopedico rizzoli/osteosarcoma-2 protocol: an updated report. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:4016–4027. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.24.4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Picci P, Sangiorgi L, Rougraff BT, Neff JR, Casadei R, Campanacci M. Relationship of chemotherapy-induced necrosis and surgical margins to local recurrence in osteosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2699–2705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.12.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Shah N, McCarville MB, et al. Outcome after local recurrence of osteosarcoma: the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital experience (1970–2000) Cancer. 2004;100:1928–1935. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]